Wislawa Szymborska

Maria Wisława Anna Szymborska [ viˈswava ʂɨmˈbɔrska ] ( 2 July 1923 in Prowent – 1 February 2012 in Kraków ) was a Polish poet . She is one of the most important poets of her generation in Poland, where her poems are counted among national literature. In the German-speaking world, she became known early on through the transmissions of Karl Dedecius and received several important awards. In 1996 she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literatureawarded. Since then, her small oeuvre of around 350 poems has also been widely distributed internationally and translated into more than 40 languages.

Szymborska kept her private life largely hidden from the public. At the beginning of the 1950s, your work was still dominated by socialist realism . With the volume of poetry Wołanie do Yeti (Calls to Yeti) in 1957 she made her breakthrough to her own form of expression, which is characterized by doubt and irony. She often looks at everyday events from unusual perspectives, which lead to general philosophical questions. Szymborska's poems are written in simple, easy-to-understand language. They do not follow a uniform poetics , but each have their own individual style. One of the most popular poems is Cat in the Empty Apartment . In addition to poetry, Szymborska also wrote feuilletons in various literary magazines.

Life

Throughout her life, Wisława Szymborska made a strict distinction between her literary work and her personal life, which she kept largely private. Details of her biography were hardly known to the public. According to Szymborska, people should seek access to their personality in their literary work instead of, as she put it, in their "external biography" or "external circumstances". She rejected all attempts to decipher her poems from her biography.

Szymborska was born in Prowent, a small settlement between the then towns of Bnin and Kórnik near Poznań in Greater Poland . Officially, however, her birth certificate shows Bnin as the place of birth, meanwhile both places are incorporated into Kórnik. Her father, Wincenty Szymborski, was the steward of Count Zamoyski , and her mother, Anna Szymborska, née Rottermund, allegedly came from the Netherlands. Szymborska had a sister named Nawoja who was six years her senior. After the count's death in 1924, the family moved to Thorn , where Szymborska attended elementary school for the first two years, then to Kraków , the city that would become her home from 1931 until her death. The eloquent father in particular supported his daughter's early attempts at writing. His death in September 1936 and the start of World War II three years later marked the end of Szymborska's sheltered childhood.

From 1935 Szymborska attended the Ursuline Gymnasium in Kraków. During the German occupation of Poland , classes could only take place in secret until the student graduated from high school in 1941. However, it was impossible to study during the war and Szymborska temporarily worked for the railway. After the end of the war she studied Polish studies and sociology at the Jagiellonian University , at the same time she published her first poems in magazines. In 1948 she broke off her studies without a degree and married the Polish writer Adam Włodek (1922-1986). He was editor-in-chief of the weekend supplement of the daily newspaper Dziennik Polski , where Szymborska's first poem appeared. Even after the divorce in 1954, they remained friendly.

Szymborska worked from 1953 as an editor at the Kraków literary magazine Życie Literackie . Here she designed the poetry section until 1966 and wrote a column called Poczta Literacka ("literary post"), from which a selection volume appeared in 2000. Another column was popular under the title Lektury nadobowiązkowe (“extraordinary reading”), in which Szymborska presented books from June 1967 in order to use them as a starting point for personal essays that range between memoirs and reflections. These columns were also published in book form. In December 1981 Szymborska ended her editorial work in the Życie Literackie . With this move she protested against the declaration of martial law in Poland . From then on she published her book reviews in the Kraków magazine Pismo , in the Wrocław monthly Odra and finally from 1993 in the Warsaw Gazeta Wyborcza . She also wrote articles for the Parisian exile magazine Kultura and the Polish samizdat publication Arka under the pseudonym Stańczykówna (daughter of the court jester Stańczyk ) .

Szymborska had already left the Polish United Workers' Party in 1966 , a move taken by a number of Polish intellectuals to protest the philosopher Leszek Kołakowski 's exclusion from the party and teaching. At that time she was already considered the most important poet of her generation, the so-called Generation 56 , whose roots lay in Polish October 1956 and the following thaw period . The poems from the Martial Law period appeared in the 1986 volume Ludzie na moście (People on a Bridge) . The ambiguity of the poems, behind whose apolitical surface allusions to political events are hidden, made the volume a great success with critics and the public. The Polish trade union Solidarność awarded Szymborska its literary prize. In 1990, Kornel Filipowicz died , Szymborska's longtime partner, with whom she had been in a relationship since 1967. Szymborska described the relationship between the two writers, who had never lived together, as "two horses galloping side by side". After his death, Szymborska retired for a time and worked through her grief in a few poems, including the popular Cat in the Empty Apartment .

Adam Zagajewski described Wisława Szymborska as "elegance personified: elegant in her gestures, movements, in her words and poems". She seemed "as if she had sprung straight out of one of the intellectual salons of 18th-century Paris." Szymborska avoided any publicity. She adored the writers Thomas Mann , Jonathan Swift , Montaigne , Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens , the painter Jan Vermeer , the director Federico Fellini and the singer Ella Fitzgerald . She collected old magazines, postcards and unusual objects, invented private board games and made collages . Her poems were not created at a desk, but on the couch, where they were only written down after they had fully taken shape in her head. Many drafts did not survive the critical review the following day and ended up in the wastebasket. The poet published a total of around 350 poems in twelve volumes of poetry. On February 1, 2012, Szymborska, who was suffering from lung cancer , died. Her final resting place is on the Cmentarz Rakowicki in Kraków . She had been working on new poems to the last. Thirteen completed poems and notes on seven more poems were published posthumously in April 2012 in the volume Wystarczy (It is Enough) .

plant

literary career

According to Dörte Lütvogt, Szymborska's first literary attempts after the Second World War were still in the tradition of the avant-garde of the interwar period and followed in particular the model of Julian Przyboś . She published her first poem in March 1945, entitled Szukam słowa (I'm looking for the word) , in a supplement to the daily newspaper Dziennik Polski . The collected poems from the post-war period, which also appeared in various other magazines in the years that followed, were to be published in 1949 in an anthology entitled Wiersze (Poems) . However, with the IV Congress of the Polish Writers' Union in Szczecin, socialist realism in the sense of the Stalinist doctrine was raised to the binding program of literature. Szymborska's poems were now considered too difficult and ambiguous, and the plan for her debut volume was dropped.

As a result, Szymborska fully adapted to the Sozrealist poetics. Her first published volumes of poetry, Dlatego żyjemy ( That's why we live , 1952) and Pytania zadawane sobie ( Questions I ask myself , 1954) sang about the construction and achievements of socialism , the contrast with the reactionary , imperialist class enemy , Lenin's power and Stalin's death . They are shaped by optimistic utopias, black-and-white thought patterns, clichéd incantations, admonitions and encouragements, as well as a seriousness and pathos that almost completely lacks the irony that was so typical of Szymborska later on. Brigitta Helbig-Mischewski emphasizes that the poems "were written with the gesture of flaming enthusiasm, of an unshakable, very authentic-looking youthful faith", in whose subsequent disappointment and disillusionment she sees an essential root of Szymborska's later "poetics of all-encompassing doubt". .

Szymborska included only a few poems from this period in her 1964 poetry selection Wiersze wybrane , and the compromising volumes of poetry are now hard to come by in Polish libraries. Later poetry no longer followed any ideology or world view; she asked questions instead of imparting predetermined answers. Some poems address her former blindness and disillusionment, such as Schyłek wieku (The End of a Century) from 1986, although the poet remained attached to the dream of a better world. In an interview she said in retrospect: “I was absolutely convinced at the time that what I wrote was correct. But this statement in no way relieves me of the guilt I feel towards the readers who may have been influenced by my poetry.”

With the onset of the thaw in Eastern Europe, and in particular Polish October 1956, came Szymborska's departure from her previous ideological beliefs and style of socialist realism. In 1957 her third volume of poetry Wołanie do Yeti (Calls to Yeti) was published , which according to Dörte Lütvogt is considered "her second and real debut". Gerhard Bauer calls it the "breakthrough [...] to a new, strictly critical and self-critical production". Instead of declarations and manifestos, Szymbosrka now wrote down “observations, objections, contradictions”. The poet was looking for her own poetic voice, placing the human individual at the center of the poems without neglecting social reality. Their "accounting with dogmatism" was expressed for the first time in an attitude of "methodological doubt".

The following volumes of poetry have different emphases: Sól ( Salt , 1962) addresses interpersonal contact, Sto pociech ( One Hundred Joys , 1967) the strangeness of human beings. Wszelki wypade ( All Cases , 1972) and Wielka liczba ( The Big Number , 1976) raise general philosophical questions, while Ludzie na moście ( People on a Bridge , 1986) is deeply rooted in contemporary history. In the late works Koniec i początek ( End and Beginning , 1993), Chwila ( Moment , 2002) and Dwukropek ( Colon , 2005) a personal component and the preoccupation with death come to the fore. The limericks and nonsense poems in Rymowanki dla dużych dzieci ( Rhymes for Big Children , 2005 ), originally not intended for publication, occupy a special place . In addition to the poems, Szymborska 's feuilletons for the magazines Życie Literackie (1968-1981), Pismo and Odra (1980s) and Gazeta Wyborcza (1993-2002) were published in five anthologies under the title Lektury nadobowiązkowe (freestyle readings) . Szymborska also translated French poetry into Polish, including fragments from the work of the Baroque poet Théodore Agrippa d'Aubigné in 1982 .

style and poetry

According to Marta Kijowska , the peculiarity of Szymborska's style is that it is not a fixed style. Instead, the ability to change, in which each poem is written in its own style depending on the subject and genre, has become Szymborska's trademark. In this regard, Dörte Lütvogt described Szymborska as a "master in creating 'special poetics' for each individual poem", although the poetry retained an unmistakable signature despite its variety of forms. The Polish literary scholar Michał Głowiński described this as Szymborska's "characteristic melody", her "inimitable flow of words", which could not be repeated by her epigones .

At first glance, Szymborska's poems have no secrets. Her starting point is often an everyday situation from which simple, loosely formulated and seemingly naive questions are asked. Dörte Lütvogt describes the language as the “ colloquial language of educated people”, behind the apparently obvious content of which there are often several levels of meaning. The simplicity turns out to be a trick that deliberately wants to distract from the artistry of the poem. Humor and irony also serve this function of disguising the depth and seriousness of her poetry. Jerzy Kwiatkowski characterizes Szymborska's poetry: “She pretends that her writing is about everyday things […] She pretends that writing poetry is child's play. After all, she hides the tragic, bitter meaning of her poetry. She acts like it doesn't touch her that deeply."

Departing from the everyday, Szymborska's poems often offer unusual perspectives and insights. Joanna Grądziel elaborates: “The secret of success lies in the way of seeing and how the mundane is expressed in the non-ordinary way.” General philosophical considerations arise from these unfamiliar perspectives. According to Gerhard Bauer, the reader in Szymborska's poems often has the rug pulled from under their feet. In a “ convergence of philosophy , provocation and poetry” they led to the “most unexpected finds and questions”: “Szymborska's poems are characterized by the fact that they stir up more thoughts than they actually deliver and pin down. They hint at possibilities, suggest conclusions, propose alternatives without vouching for them.” Marcel Reich-Ranicki concludes that Szymborska's “very well thought-out, ironic poetry tends somewhat towards philosophical poetry. What is decisive, however, is the linguistic power of her poetry”.

reception

As early as the 1960s, Szymborska became known and popular in her Polish homeland. Her poetry came to public attention not least because of Andrzej Mundkowski's setting of Nic dwa razy się nie zdarza (Nothing Happens a Second Time) in 1965. The song, performed by his wife Łucja Prus , won a prize from the Ministry of Art and culture and became a popular hit . Four further settings of her works can be verified up to 1997. Szymborska's poems are an integral part of Polish national literature and are taught in Polish schools. The international dissemination of Szymborska's work was promoted in particular by the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996. Her books have been translated into 42 languages.

In Germany, Szymborska's distribution is closely linked to the name of Karl Dedecius , who was the only publisher of Polish poetry in the Federal Republic until the late 1970s. In sixteen of eighteen of his selected volumes of Polish poetry published up to 1995, individual poems by Szymborska were represented, for the first time in 1959 in the anthology Lessons of Silence . In 1973 Suhrkamp Verlag published a first selection of Szymborska's poems entitled Salt . Even before the Nobel Prize was awarded, the publishing house published three more volumes of Szymborska's poetry, and at the time the prize was announced in autumn 1996 it was the only European publisher to have several volumes of her poetry in its programme. However, the majority of the total German circulation of over 90,000 copies by the year 2000 was only reached after the Nobel Prize was awarded. Szymborska's poems have been available in East Germany since the late 1970s. The only selection volume of her poetry in the publishing house Volk und Welt under the title Vokabeln , translated by Jutta Janke , was not very successful. Gerhard Bauer praised Dedecius' "very lively translations that reveal a great deal of intuition". Compared to his "form-oriented, fairly precise and at the same time artistic" translations, Janke's artful adaptations allowed themselves "a lot of translational freedom", according to Beata Halicka .

As early as the 1950s, Szymborska received her first important awards in her home country, including the Golden Cross of Merit of the Republic of Poland , which at that time was still primarily used to honor the poet's subordination to socialist doctrine. In 1963, the award from the Polish Ministry of Culture was accompanied by general critical acclaim and growing public interest in her work. In the 1990s, Szymborska received important awards in Germany, including the Goethe Prize and the Herder Prize , which was due to the special distribution of her poetry there. She has been one of the most important contenders for the Nobel Prize in Literature since 1994. However, she was not well known internationally at that time and the 1996 award was seen by some as a surprise. Even in Poland there were voices that would have preferred to award the prize to their compatriot Zbigniew Herbert . The selection committee awarded the Nobel Prize "for a poetry that, with ironic precision, allows the historical and biological context to emerge in fragments of human reality", adding to Szymborska's popular nickname " Mozart of poetry" that her work also reveals the "fury of Beethoven ". . In 2011 Szymborska was awarded the Order of the White Eagle , the highest decoration of the Third Republic of Poland . Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski commented on her death the following year : "An irreparable loss for Polish culture".

awards

- 1954: City of Kraków Literary Prize

- 1955: Golden Cross of Merit of the Republic of Poland

- 1963: Prize of the Polish Ministry of Culture

- 1990: Siegmund Kallenbach Prize

- 1991: Goethe Prize

- 1995: Herder Prize

- 1995: Honorary doctorate from Adam Mickiewicz University

- 1996: Polish PEN Club Prize

- 1996: Samuel Bogumil Linde Prize

- 1996: Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1999: Admission to the American Academy of Arts and Letters as a non-resident honorary member

- 2005: Admission to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as a non-resident honorary member

- 2011: Order of the White Eagle

factories

poetry books

- Dlatego żyjemy ( Therefore We Live , 1952)

- Pytania zadawane sobie ( Questions I Ask myself , 1954)

- Wołanie do Yeti ( Calls to Yeti , 1957)

- Sól ( Salt , 1962)

- Sto pociech ( A Hundred Joys , 1967)

- Wszelki wypadek ( All Falls , 1972)

- Wielka liczba ( The Big Number , 1976)

- Ludzie na moście ( People on a Bridge , 1986)

- Koniec i początek ( End and Beginning , 1993)

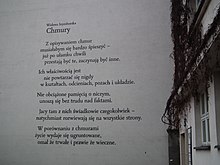

- Chwila ( Moment , 2002)

- Dwukropek ( Colon , 2005)

- Tutaj ( Here , 2009)

- Wystarczy ( It's Enough , 2012)

Others

- Lektury nadobowiązkowe. 1973, 1981, 1992, 1996, 2002 (features).

- Poczta literacka czyli jak zostać (lub nie zostać) pisarzem. 2000 (responses to letters to the editor).

- Rymowanki dla dużych dzieci. 2005 (Limericks and Nonsense Poems).

German editions

The German editions do not always correspond to the original editions with the same title, but are own compilations from different volumes of poetry.

- salt . poems. Transcribed and edited by Karl Dedecius . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1973.

- vocabulary . poems. Edited and rewritten by Jutta Janke. People and World, Berlin 1979.

- That's why we live . poems. Transcribed and edited by Karl Dedecius. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-518-01697-0 .

- A hundred joys . poems. Edited and transmitted by Karl Dedecius. With a foreword by Elisabeth Borchers and an afterword by Jerzy Kwiatkowski . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-02596-1 .

- Good-bye. see you tomorrow poems. Selected and transmitted by Karl Dedecius. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-518-40675-2 .

- The Poems . Edited and transmitted by Karl Dedecius. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1997, ISBN 3-518-40881-X .

- love poems . Selected and transmitted by Karl Dedecius. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-458-34811-5 .

- the moment . Poems, Polish and German. Transcribed and edited by Karl Dedecius. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-518-22396-8 .

- The Poems . Edited and transmitted by Karl Dedecius. The Brigitte Edition, Volume 12. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-570-19520-8 .

- Happy Love and Other Poems . Translated from the Polish by Renate Schmidgall and Karl Dedecius. With an afterword by Adam Zagajewski . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42314-1 .

literature

- Paweł Bąk: The metaphor in translation. Studies on the transfer of Stanisław Jerzy Lec's aphorisms and Wisława Szymborska's poems . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-55757-0 .

- Gerhard Bauer : question art. Szymborska's Poems . Stroemfeld/Nexus, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-86109-169-0 .

- Beata Halicka : On the Reception of Wisława Szymborska's Poems in Germany . Logos, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89722-840-8 .

- Brigitta Helbig- Mischewski : Sozrealist Poetry by Wisława Szymborska . In: Alfrun Kliems , Ute Raßloff, Peter Zajac (eds.): Poetry of the 20th century in East-Central Europe . Volume 2: Socialist Realism . Frank & Timme, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-86596-021-9 , pp. 191–203 ( PDF; 142 kB ).

- Marta Kijowska : "The road from suffering to tears is interplanetary." Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996 . In: Charlotte Kerner (ed.): Madame Curie and her sisters. Women who got the Nobel Prize. Beltz, Weinheim/Basel 1997, ISBN 3-407-80845-3 , pp. 419-447.

- Dörte Lütvogt : Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-03309-6 .

- Dörte Lütvogt: Time and Temporality in Wisława Szymborska's Poetry . Sagner, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-87690-914-1 .

- Leonard Neuger , Rikard Wennerholm (eds.): Wislawa Szymborska – a Stockholm Conference. May 23-24, 2003 . Almqvist & Wiksel, Stockholm 2006, ISBN 91-7402-356-X .

- Jutta Rosenkranz: "I regard a poem as a dialogue". Wislawa Szymborska (1923–2012) . In: Jutta Rosenkranz: Line by line, my paradise. Important Women Writers, 18 Portraits . Piper, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-492-30515-0 , pp. 241–260.

web links

- Literature by and about Wisława Szymborska in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Wisława Szymborska in the German Digital Library

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the 1996 award ceremony to Wisława Szymborska (English) and press release (German)

- Urszula Usakowska-Wolff: Wislawa Szymborska . ( September 4, 2014 memento at Internet Archive )

- Poem: The First Photo ( Memento of March 4, 2016 at Internet Archive ) from: A Hundred Joys . In: Braunau Contemporary History Days

itemizations

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. p. 2

- ↑ Beata Halicka: On the reception of Wisława Szymborska's poems in Germany. p. 51.

- ↑ Lothar Müller: On the death of Wisława Szymborska: researcher of the moment. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . February 3, 2012.

- ↑ Adam Górczewski: Folwark Prowent - to tu urodziła się Wisława Szymborska . In: RMF 24 of February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 420–422.

- ^ a b c Małgorzata Baranowska : Wisława Szymborska – The Poetry of Existence. On culture.pl , February 2004.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 422–423.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 423–426.

- ^ a b Urszula Usakowska -Wolff: Wisława Szymborska. ( July 3, 2013 memento at Internet Archive )

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. P. 431.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 436–437.

- ↑ Wislawa Szymborska at Suhrkamp Verlag .

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. P. 430, 437.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 438–440.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. p. 438.

- ↑ Adam Zagajewski : There is no other poet like her . In: Wisława Szymborska: Happy Love and Other Poems . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42314-1 , p. 97.

- ↑ Adam Zagajewski: There is no other poet like her . In: Wisława Szymborska: Happy Love and Other Poems . Suhrkamp, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-42314-1 , p. 95.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 433, 445–446.

- ↑ Wisława Szymborska, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, is dead ( Memento of November 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) at the German Poland Institute , February 2, 2012.

- ↑ knerger.de: The grave of Wisława Szymborska

- ↑ Wislawa Szymborska is dead . On Spiegel Online , February 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Wystarczy" hits bookstores ( Memento of March 4, 2016 at the Internet Archive ). On thenews.pl , April 20, 2012.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Time and Temporality in Wisława Szymborska's Poetry. pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Brigitta Helbig-Mischewski: Sozrealistic Poetry by Wisława Szymborska. pp. 191-193.

- ↑ Brigitta Helbig-Mischewski: Sozrealistic Poetry by Wisława Szymborska. p. 191.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Brigitta Helbig- Mischewski : Sozrealistic Poetry by Wisława Szymborska. pp. 201-202.

- ↑ Quoted from: Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. p. 428.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Time and Temporality in Wisława Szymborska's Poetry. p. 14

- ↑ Gerhard Bauer: Question Art. Szymborska's poems. pp. 46-47.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. p. 4

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Time and Temporality in Wisława Szymborska's Poetry. pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. p. 429.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. P. 434.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. pp. 6–7, 9.

- ↑ Jerzy Kwiatkowski: Afterword . In: Wisława Szymborska: A Hundred Joys . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-518-02596-1 , p. 216.

- ↑ Dörte Lütvogt: Studies on the poetics of Wisława Szymborska. pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Gerhard Bauer: Question Art. Szymborska's poems. pp. 14, 16, 264.

- ↑ Quoted from: Urszula Usakowska-Wolff: Wisława Szymborska. ( July 3, 2013 memento at Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Gerhard Bauer: Question Art. Szymborska's poems. p. 18

- ↑ Polish Music Newsletter. ( Memento of October 15, 2012 at the Internet Archive ) February 2012, Vol. 2, ISSN 1098-9188 .

- ↑ Polish literature Nobel prize winner dies ( Memento of April 18, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) on the Official Promotions Portal of the Republic of Poland .

- ↑ Beata Halicka: On the reception of Wisława Szymborska's poems in Germany. pp. 136-137.

- ↑ Beata Halicka: On the reception of Wisława Szymborska's poems in Germany. pp. 160-161.

- ↑ Beata Halicka: On the reception of Wisława Szymborska's poems in Germany. p. 133.

- ↑ Gerhard Bauer: Question Art. Szymborska's poems. p. 19

- ↑ Beata Halicka: On the reception of Wisława Szymborska's poems in Germany. p. 188.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: "The path from suffering to tears is interplanetary". Wisława Szymborska (b. 1923), Nobel Prize in Literature 1996. pp. 427, 429, 441–442.

- ↑ Marta Kijowska: Small eternities of a moment . ( Memento from April 1, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: St. Galler Tagblatt . February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Press release on the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature , October 3, 1996.

- ↑ Polish Nobel laureate in literature dies. In: Time Online . February 2, 2012.

- ↑ Honorary Members: Wisława Szymborska. American Academy of Arts and Letters, accessed March 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Wisława Szymborska: Clouds (Chmury) . In: Günter Grass and others: The future of memory . Steidl, Goettingen 2001, ISBN 3-88243-713-8 , p. 87.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Szymborska, Wislawa |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Szymborska, Maria Wislawa Anna |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish poet |

| BIRTH DATE | July 2, 1923 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kornik near Posen |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 1, 2012 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Kraków |