Augsburg's historical water management

| Augsburg water management system | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| Water towers at the Red Gate in Augsburg |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (ii) (iv) |

| Surface: | 112.83 ha |

| Buffer zone: | 3,204.23 ha |

| Reference No .: | 1580 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 2019 ( session 43 ) |

The historical water management of the city of Augsburg is regarded as outstanding testimony to the history of water use and water management . The historical structures for the use of rivers and the drinking water supply of Augsburg from the 15th to the early 20th century were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site on July 6, 2019 . The tentative list of Germany uses the (unofficial) designation "The Augsburger Wassermanagement-System". These systems include a network of variously usable flowing water channels , the oldest waterworks and the oldest water tower in Germany, as well as the oldest waterworks, which was supplied by deep wells fed by groundwater .

The beginnings of Augsburg hydraulic engineering in Roman times

A Roman military camp at the confluence of the Wertach and Lech rivers formed the exit for the Roman city of Augusta Vindelicum . It rose to the capital of the Roman province of Raetia and from it the city of Augsburg developed. To protect against the frequent strong floods , the military settlement was built on a raised terrace between the two rivers. The Augsburg high terrace is about 10 to 15 meters above the river valleys. Due to this elevated location, the settlement lacked naturally flowing water, so that water management for drinking water, industrial water and waste water became of elementary importance.

Deep groundwater wells were presumably primarily used to supply the Roman city with drinking water. The Romans built a long-distance water pipe to meet their needs for service water . Based on the topography and archaeological findings, it is assumed that this long-distance water pipeline, as an open canal, carried a water stream from the area of Igling , Schwabmühlhausen and / or Hurlach over around 35 km into the city. This was presumably mainly fed by water that was diverted from the Singold there . The canal used the natural gradient of the high terrace of around 3 per thousand and led from Hurlach via today's places Graben , Kleinaitingen , Königsbrunn , Haunstetten and Göggingen to Augusta Vindelicum. He initially followed the eastern edge of the raised terrace; between Haunstetten and Göggingen it changed over to the western edge and led into the Roman city at the western gate, which was located in what is now the Augsburg main station / deaconess house. Its estimated volume flow was about 1.2 m³ / s.

The Roman canal is said to have been in use for 300 or 400 years from around 20 AD. He supplied water and hydropower for craft businesses, also in the run-up to the city. The latrines could be flushed with its water . There is still no evidence as to whether the city's thermal baths were fed with this water. With the discovery of the Roman bath in Königsbrunn, there is an example of the use of the water pipe in a public bath outside Augsburg.

Contrary to earlier assumptions, the Roman long-distance water pipeline was apparently not built in stone, but sealed with a water-impermeable clay soil and fastened at the edges with rods or wooden boards. An archaeological excavation in Göggingen (Bayerstraße 43-45) from 1966 to 1970 showed that there was not a single canal at this point, but rather a complex system with several main trenches, within which at least 12 individual, consecutive ones Channels could be distinguished. These were between 1 and 2 meters wide and about 0.5 meters deep. A recent excavation in 2011 on the site of Erdgas Schwaben in Göggingen made it possible for the first time to examine the water pipe in a horizontal section.

With the end of Roman times, this water pipe fell into disrepair. The place name of Graben, mentioned in a document in 1063 as "ecclesia Grabon", presumably refers to a trench-like channel in the area that marked the course of the earlier canal here in the Middle Ages. Today this channel can only be seen with the naked eye in a piece of forest near Hurlach, and in other places using aerial archeology .

Canals from the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages at the latest , canals were dug that led the water of the Lech from the south into the lower areas of the meanwhile grown city and out of the city again in the north. Unlike the Roman long-distance water pipeline, these did not run up on the elevated terrace, but several meters deeper on the western edge of the Lech Valley. Four Lech canals are named in the Augsburg city charter of 1276. The Lech canals have been expanded and changed again and again. This hydraulic engineering resulted in the network of open, above-ground channels that are available today, which carry considerable volume flows of flowing water.

Significance and extent of the medieval canal system

The power of flowing water used to be the ultimate source of energy . For centuries, the canal system was used for the use of water power by mills and craft businesses , as process water for dyeing and tannery, and for transporting goods by rafting . It thus contributed significantly to the economic prosperity of the Free City of Augsburg. In addition, the canals played an important role in urban hygiene , as they were also used for waste and sewage disposal before there was a modern waste disposal or alluvial sewerage system .

In Augsburg, the river water is diverted at weirs , pumped in canals using the natural slope of the terrain through various districts, out of the city and back into the river bed. At the end of the canals all flow into the same river from which their water originates. By means of weirs and gates , the volume flows in the canals can be controlled and kept constant largely independently of the water fluctuations in the river. Since the channels normally have constant flow, changes and maintenance work on them require well-coordinated regulation of the flow rates in the entire network.

The Hochablass weir in the Lech, documented from 1346, ensures that the Lech canals are constantly fed all year round. There were several disputes between Augsburg and the neighboring ducal Bavaria about this weir and the associated use of the Lech water . Emperor Friedrich III. In 1462 Augsburg granted Augsburg the legal right to draw as much water from the Lech as the city wanted. The Hochablass was moved and heavily rebuilt in 1552 and 1911/12. It still fulfills its important function today to supply Augsburg with Lech water. The amount of water withdrawn at the high outlet is around 45 m³ / s. Added to this are a further 3 m³ / s, which are taken from the Lech about 14 km further up the Lech at another weir and which the Lochbach feeds into the Augsburg sewer network ("Lochbachanstich" at today's Lech dam 22 - Unterbergen ).

Separate from the Lech canals, a separate system of canals was dug west of the city in order to use the water power of the Singold and, since the late 16th century, the Wertach as well. It includes today's factory canal, Wertach Canal, Holzbach and Senkelbach (around 28.5 m³ / s in the factory canal), the Mühlbach and Hettenbach (around 2 m³ / s) and some smaller canals.

At the beginning of the 19th century there were 148 undershot water wheels in the city area.

Today the Lech canals have a total length of 77.7 km, the Wertach canals of 11.6 km.

Other uses

The Augsburger Stadtmetzg , the most modern building of the butchers' guild until then, shows an imaginative use of the canals in Augsburg . The Augsburg city architect Elias Holl built it 1606–1609 over a Lech canal, which cannot be seen from the outside of the house as the canal is covered before and after the building. The constant flow of fresh water kept the meat products cool there and the slaughterhouse waste could be transferred to the water. The building has been preserved, but is now used for other purposes.

The broad trenches of the Augsburg city fortifications on the outside of the city walls and bastions for defense could also be flooded from the Augsburg canal network . When the city fortifications were no longer useful in the 19th century, they were largely demolished and partially built over. The outer city moat, which borders the Jakobervorstadt , is still preserved today. Its water surface is valued by the Augsburgers because of its idyllic calm and tree-surrounded mirror and is used on the Augsburg boat trip with boats.

Industrialization through hydropower

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the canals in Augsburg were crucial for the industrialization of the city. They brought a new economic upswing to the city, which had lost much of its former size with the loss of its imperial freedom and the fall of Bavaria in 1806.

Large companies settled in open spaces on the outskirts. For them, new canals were dug there for the industrial use of hydropower. The largest branch was the textile industry . This is how the Augsburg textile district came into being , and suburbs such as Haunstetten , Göggingen and Pfersee , which are now incorporated, benefited from the new large employers. Other large branches of the company that used the hydropower of the Augsburg canal system were machine manufacturers such as Sander'sche Maschinenfabrik, which was renamed several times and eventually became the mechanical engineering group MAN and the printing machine manufacturer MAN Roland , as well as the largest paper manufacturer in Germany at times , Haindl Papier . German industrial history would have been different without the canals in Augsburg .

Museums that present these aspects of the city's history are the State Textile and Industry Museum (tim for short) and the Technology and Transport Museum MAN Museum . In the factory palace , the Augsburg Turbine Museum shows the turbine technology of the Mechanical Cotton Spinning and Weaving Mill (SWA) founded in 1837 . In the Glaspalast Augsburg , another large building of this textile company, there are now several art museums, which means that the privately owned building is accessible to the public.

Todays use

Unlike in many other cities, the historic canal network in Augsburg is still intact today. In the 20th century, the German textile industry fell through globalization , which also hit Augsburg hard. The textile companies had to close their factories, but their channels remained. Today they are mainly used to generate renewable energy . Because of their easily controllable volume flow, they are well suited for the use of hydropower to generate electricity . Today there are several dozen hydropower plants in the Augsburg city area. The oldest are the hydropower plant on the Wolfzahnau (1901/1902) and the Wertach power plant (1920/1921). Both are listed and are still in operation today with modern turbine technology inside the historic building.

After the canals were partially covered in the early 20th century, they are largely open again today. The flowing water and the bridges over the canals enrich the cityscape, especially in the romantic lower old town center , whose name Lechviertel comes from the Lech canals.

The bathing in the Augsburg channels because of the dangerous strong currents almost everywhere strictly prohibited. It is permitted in a few selected places: at the Gögginger Luftbad , in the “Fribbe” open-air pool on Friedberger Strasse, on a section of the capital stream and the Proviantbach stream .

Since the 1972 Summer Olympics of the acts Artificial whitewater converted Augsburger Eiskanal the Canoeing . The Augsburg Canoe Museum is dedicated to the history of canoeing in Augsburg .

Central drinking water supply from the 15th century

The imperial city of Augsburg was very wealthy in the late Middle Ages . Their councilors set up a central supply network for their citizens with drinking water early on . It began in the early 15th century in the Ulrichsviertel , from the 16th century the entire city was supplied.

Drinking water sources

River water like that of the Lech is hardly suitable as drinking water because of its pollution. On the one hand, drinking water in Augsburg, as almost everywhere, was taken from the groundwater by digging wells . The special geological situation of the Lechfeld , an Ice Age gravel plain south of Augsburg, also made it possible to channel the clear spring water from the Brunnenbach , which rises south of the city, into the city. Unlike the Lech, Wertach and Singold water, this was very good drinking water and was used to feed the wells, hence the name of the water supplying it.

Augsburg water art

The central drinking water supply used water art techniques and the principle of the water tower . Here, the drinking water is first pumped into an elevated tank. From this it feeds a pipeline network without pumps, only by gravity . A constant water pressure is thus achieved. The tap water can be withdrawn as required and has only an insignificant effect on the pressure. The oldest water tower in Augsburg was built in 1416. In the course of the expansion of the drinking water supply, additional water towers were added; the existing ones have been rebuilt and added several times. Before 1843, seven waterworks with nine water towers were in use in Augsburg.

In the waterworks at the foot of the towers, the water was mostly lifted with reciprocating piston pumps that were driven by water wheels. The canalized river water was used to supply the city with drinking water through its hydropower: Water raised water. There was a special technical water art solution in the lower fountain tower , where the drinking water was raised in a special device, the Machina Augustana , by means of an arrangement of stacked Archimedean screws since 1538 . However, the invention did not take hold in the long term and was later replaced by crank pump stations.

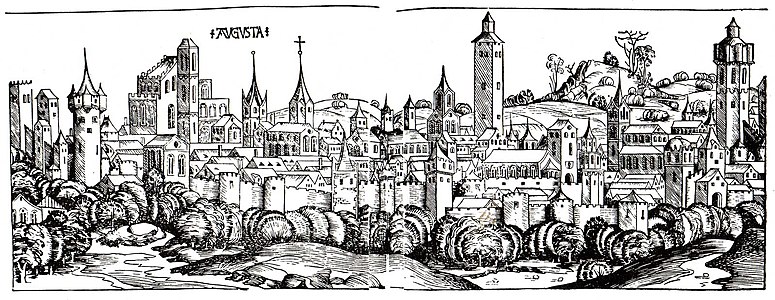

Augsburg in Schedel's world chronicle , 1493

The waterworks at the Red Gate , built in 1414, is the oldest existing waterworks in Germany and probably in Central Europe. It served Augsburg's drinking water supply for over 460 years. Through the aqueduct at the Red Gate , both drinking water from the Brunnenbach and separately channeled water from the Lochbach canal was fed across the moat to the waterworks. Today the waterworks at the Red Gate is a museum. The technical systems are no longer available, but are explained using display boards and models.

From the water towers, the drinking water was distributed through a network of pipes in the city , whereby the pipes were not made of metal, but of drilled out wooden trunks, so-called dicks . It fed public wells and private house connections. The height of the Great Water Tower was sufficient to bridge the difference in level between the Red Gate in the Lech Valley and the Upper City on the elevated terrace and the Maximilianstrasse there.

The engineering development and maintenance of the water supply was the responsibility of a particularly responsible office, that of the well master . Caspar Walter (1701–1769), who wrote the Hydraulica Augustana in 1754 , a pioneering, comprehensive handbook of all aspects of water art, is considered the most important fountain master from Augsburg . The fountain masters lived in Augsburg at the oldest of the waterworks, the one at the Red Gate , in the upper fountain master house . The ensemble that is still preserved today also includes the lower fountain master's house (which now houses the Swabian handicraft museum) and the fountain master's yard .

A revolutionary new waterworks

The central drinking water supply of Augsburg with its waterworks and towers was indeed groundbreaking for many other cities for centuries, but the water quality was not yet optimal. Pollution led to cholera epidemics. To find a solution, two engineers were commissioned in the 19th century to map the groundwater resources in the city forest. The result, published in 1876, was the world's first groundwater mapping.

On this basis, collecting wells were dug in the Siebentischwald and in 1878 a new waterworks was built on the Hochablass . It replaced all older waterworks. In this pumping station, too, the power of the flowing water was used to transport the drinking water - hence the location at the Hochablass, above a newly built canal. A new type of technology was used here, which for the first time no longer required any water towers. The pump and air tank technology from Maschinenfabrik Augsburg , the predecessor of today's MAN , was a sensation at the time and attracted attention across Europe. While water towers were being built for the first time all over Europe, Augsburg was able to do without water towers again. Today the Augsburg drinking water is considered to be one of the best in Europe.

Since the middle of the 20th century, electric centrifugal pumps have played an increasing role in pumping drinking water. Today the line pressure is generated directly by submersible pumps in the filter well. The waterworks at Hochablass was freed from its original main purpose and could be converted into a hydropower plant that generates electrical energy instead of pumping water. Opposite was a new pump-less water works, a so-called 2006 water transfer point , with filter systems , an emergency UV - sterilization plant built and a measuring point for drinking water quality control. In 2007 this took over the remaining tasks of the waterworks at Hochablass. The old waterworks was redesigned into a museum and since then has been used to educate people about this chapter of Augsburg's hydrotechnical history.

The Augsburg waters in art

The great importance of the topic of water for Augsburg was also expressed in works of art.

Magnificent Augsburg fountain

During the heyday of Augsburg in the Renaissance , three magnificent Augsburg fountains were created as prestige objects of Augsburg water art . The city commissioned the famous sculptors Hubert Gerhard and Adriaen de Vries , who worked on the fountain from 1588 to 1600. Augustusbrunnen , Merkurbrunnen and Herkulesbrunnen form a symbolic triad on Maximilianstrasse and are adorned with mannerist bronze sculptures. The theme of water is artistically addressed in a variety of ways in these fountains, beyond their water-donating function. The mythological figure of Hercules , who defeated the many-headed water serpent Hydra , is said to symbolize the victory of man over the wild power of water. The Herkulesbrunnen thus stands for the craftsmen who use the water .

To protect them, the valuable original statues have been exhibited in the inner courtyard of the Maximilian Museum since 2000 , while replicas that are true to the original can be found on the fountain .

For a selection of other fountains see the list of fountains in Augsburg .

The four river deities

Several Renaissance works of art in Augsburg depict the quartet of the most important waters for Augsburg - Lech, Wertach, Singold and Brunnenbach - allegorically personified as deities .

At each of the four corners of the square Augustus Fountain on Rathausplatz there is a bronze river deity : two women and two men. Attributes such as oars, fishing nets, cogwheels or jugs refer to the use of the respective body of water.

The monumental image Augusta and the four river gods in the Golden Hall of the City Hall (pictured at right), created in 1622 by Hans Rottenhammer , is also these four aquatic environment as river gods. They sit at the feet of an Empress, which the Augsburg coat of arms and a Zirbelnuss that Symbol of Augsburg, hold and pour a never-ending stream of water from jugs. Here Lech and Wertach are portrayed as bearded men, Singold as women and Brunnenbach as a youth. The Golden Hall was destroyed in World War II in 1944, so this picture is not an original, but a reconstruction.

The four Augsburg river gods are also depicted on one of the three gold-plated bronze relief panels of the Hercules Fountain ( Alliance of Roma and Augusta Vindelicorum ).

World Heritage candidacy

On August 1, 2012, Augsburg submitted an application for inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List at the German Conference of Ministers of Education under the title “Hydraulic engineering and hydropower, drinking water and fountain art in Augsburg” . The Augsburg non-fiction author and publisher Martin Kluger wrote an accompanying book for this application in 2012 and accompanied the further course of the World Heritage candidacy with further publications. On January 15, 2015, the "Augsburg Water Management System" was entered as a World Heritage candidate in Germany's tentative list. In February 2018, it was nominated for treatment at the 43rd session of the 2019 World Heritage Committee .

In order to justify the outstanding universal significance, the following were given, among other things:

The protection of the valuable resource water, an economically sensible and economical use of it and the great importance of water, which is articulated in architecture, art and the public, make Augsburg a global role model. ... The Augsburg water management system is an outstanding result of human creativity over many generations and stages of development. The ensemble of important architectural and technical monuments and the network of canals make it possible to understand Augsburg's development in water technology from the economically prosperous late Middle Ages to its early development into an industrial metropolis. In every step, this development was supported by the water management system.

The aim was to be entered on the World Heritage List based on criteria (ii) and (v). Criterion (v) was rejected during the nomination process. Instead, nominations were made under criteria (ii), (iv) and (vi). According to ICOMOS , criterion (vi) could not be adequately justified. Enrollment at UNESCO on July 6, 2019 in Baku took place under criteria (ii) and (iv):

Criterion (ii): Augsburg's water management system has produced significant technological innovations. The strict separation between drinking and industrial water was introduced as early as 1545, long before hygiene research identified impurities in drinking water as the cause of many diseases. The international exchange of ideas for water supply and water extraction inspired the Augsburg engineers and builders to pioneering technical innovations, many of which were tested and introduced in Augsburg for the first time. Evidence of this are the extraordinary works of engineering, architecture and art, which illustrate the continuous application and further development of technical and artistic standards, such as the canals themselves, weirs, canal crossings, drinking water works, wells, water cooling in the city butchery and power plants of the early industrial Power generation.

Criterion (iv): As a technical-architectural ensemble, the Augsburg water management system illustrates the use of water resources and the provision of pure drinking water as the basis for the continuous growth of a city and its economic prosperity since the Middle Ages. This abundance of water offered favorable conditions for households, crafts and trades as well as for industry in Augsburg, especially for mills, tanneries, dye works, textile production, goldsmiths and power generation in several development periods. Significant building types are drinking water works, wells, hydropower plants and others.

Criterion (vi), which is also aimed for, but not endorsed by ICOMOS for registration:

Criterion (vi): Augsburg's water management system is directly and tangibly linked to the fundamental idea of the strict separation of drinking and service water as a basic requirement for sustainable and social development. More than 60 hydrotechnical models from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries in permanent exhibitions or in depots, the originals of the instruction plans and paintings in the waterworks at the Red Gate, sketches, engravings, manuscripts and publications in the archives, libraries and art collections of the The city as well as the visitor lists and travel reports from scholars bear witness to the recognized pioneering role of Augsburg's water management over centuries. The book "Hydraulica Augustana", published by Caspar Walter in 1754, became one of the early reference books for hydraulic engineers. It documents the extraordinary importance of the standards set by the Augsburg fountain masters and shows their influence on the development of urban water management systems and the scientific exchange between the various European regions.

literature

- Wilhelm Ruckdeschel: Power plants. Mills. Water towers. Technical monuments in the Augsburg district . Brigitte Settele Verlag, Augsburg 1998.

- Susanne F. Kohl: History of the city drainage Augsburg . 1st edition. City of Augsburg, Augsburg 2010.

- Martin Kluger : Historical water management and water art in Augsburg. Canal landscape, water towers, fountain art and water power . 2nd Edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-939645-50-4 .

- Martin Kluger: Hydraulic engineering and hydropower, drinking water and fountain art in Augsburg . 1st edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-939645-72-6 .

- Martin Kluger: Augsburg's historical water management. The way to the UNESCO World Heritage . 1st edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-939645-81-8 .

- Gregor Nagler: craft, technology, industry. Augsburg 2015. ( Download, City of Augsburg ).

- Gregor Nagler: Augsburg and the water. In: Yvonne Schülke (Ed.), Artguide Augsburg. Augsburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-935348-23-2

- Gregor Nagler: Preserving monuments together - in Augsburg. Augsburg 2016. ( Download, City of Augsburg ).

- Franz Häußler: Hydropower in Augsburg . 1st edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-939645-85-6 .

- Christoph Emmendörffer and Christof Trepesch (eds.): Water Art Augsburg. The imperial city in its element. Accompanying volume for the exhibition in the Maximilian Museum Augsburg . Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-7954-3300-0 .

Web links

- Waterway map city area Augsburg (PDF file; 1 p., 7.96 MB)

- Water life - nature in Augsburg - description of all city streams

- Nina Arnold: Augsburg - City of Water (TV show). In: Experience Bavaria. BR Fernsehen , April 16, 2018, accessed August 16, 2018 .

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- The Augsburg water management system

Footnotes and individual references

- ↑ tentative list. In: www.unesco.de. German UNESCO Commission, accessed on May 29, 2018 .

- ↑ The oldest Roman military site existed between 8 BC. And 9 AD on the Wertach in today's Oberhausen district . After floods destroyed this camp, the military settlement was re-established between 10 and 15 AD on the top of the high terrace between Lech and Wertach. Source: Augsburger Stadtlexikon , page 30

- ↑ Due to the location on the elevated terrace, these were eleven to twelve meters deep. Source: Stefanie Schoene: How builders in Augsburg tricked gravity 2000 years ago , article in the Augsburger Allgemeine from May 19, 2016

- ^ Walter Groos: Contributions to the early history of Augsburg, page 14 , in: 28th report of the natural research society Augsburg (PDF)

- ↑ Christoph Bauer: The Roman rule in Vindelikien, in: History of Swabia until the end of the 18th century (Handbook of Bavarian History, Volume 3/2) . Munich 2001, p. 60 .

- ↑ Stefanie Schoene: How builders in Augsburg tricked gravity 2000 years ago , article in the Augsburger Allgemeine from May 19, 2016

- ↑ Article Singold in the Augsburg Wiki , accessed on June 1, 2018

- ^ The Roman service water pipeline of Augsburg. Investigations in Göggingen from 1966 to 1970. Bavarian prehistory sheets 79, 2014, 87–193, accessed on June 1, 2018

- ^ The Roman service water pipeline of Augsburg. Investigations in Göggingen from 1966 to 1970. Bavarian prehistory sheets 79, 2014, 87–193, accessed on June 1, 2018

- ^ Ines Lehmann: Roman aqueduct discovered in Göggingen , report by the Augsburger Allgemeine on the excavation in Göggingen 2011, accessed on June 1, 2018

- ↑ Martin Kluger: Historical water management and water art in Augsburg: Canal landscape, water towers, fountain art and water power . Context Verlag, Augsburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-939645-50-4 , p. 33 .

- ^ Martin Kluger: Hydraulic engineering and hydropower, drinking water and fountain art in Augsburg . 1st edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-939645-72-6 , p. 77 .

- ↑ River and floodplain development: Basics and experiences . Springer-Verlag, 2016, ISBN 978-3-662-48449-4 , p. 78 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Augsburg City | Bathing in the Proviantbach. In: augsburg-city.de. www.augsburg-city.de, accessed on August 6, 2018 .

- ^ Martin Kluger: Hydraulic engineering and hydropower, drinking water and fountain art in Augsburg. 1st edition. Context Verlag, Augsburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-939645-72-6 , p. 2 .

- ↑ MDZ reader | Band | The drinking water conditions in the city of Augsburg | The drinking water conditions in the city of Augsburg. Retrieved August 8, 2019 .

- ^ Andreas Emmerling scale: Hygiene - Hydrology - Water law. History of groundwater level monitoring from 1856 to the beginning of the state groundwater services . Ed .: Writings of the German Water History Society eV DWHG, Norderstedt, doi : 10.1515 / 9783110916430.144 .

- ^ City of Augsburg. In: augsburg.de. Retrieved May 25, 2018 .

- ↑ The water supply in the Renaissance period . P. von Zabern, 2000, ISBN 978-3-8053-2700-8 , p. 117 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ The book on the World Heritage application ( Memento from May 12, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In: Stadtzeitung online. Augsburg, July 24, 2012, accessed April 18, 2017

- ↑ see section #Literature

- ↑ Original designation in English Hydraulic Engineering and Hydropower, Drinking Water and Decorative Fountains in Augsburg , German designation according to the tentative list. In: www.unesco.de. German UNESCO Commission, accessed on May 29, 2018 .

- ^ A b c Hydraulic Engineering and Hydropower, Drinking Water and Decorative Fountains in Augsburg. In: whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Center, accessed May 22, 2018 .

- ↑ List of nominations received by February 1, 2018 and for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 43rd session (2019). In: whc.unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage Center, May 14, 2018, accessed May 29, 2018 .