Bremen city law

| Basic data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | Bremen city law |

| Type: | City law |

| Scope: | Bremen and places of the city legal family |

| Legal matter: | City law |

| Original version from: | 1303-1308 |

| Entry into force on: | 1308 |

| Last revision from: | 1428, 1433 |

| Expiry: | 19th century |

| Please note the note on the applicable legal version. | |

The Bremen city law was the city law of the Hanseatic City of Bremen developed in the course of the High Middle Ages and codified for the first time in 1303 . It remained in force until it was replaced by modern codifications in connection with developments after the French Revolution and the wars of liberation in the 19th century, despite changes and further developments. The last remnants of the town charter were only removed with the Constitution of 1920 in the wake of the November Revolution and the Bremen Soviet Republic . The Bremen city law applied in the area one, in comparison to others, z. B. in particular that of the Luebian law , small city law family. It was safely adopted in the cities of Delmenhorst , Oldenburg , Verden and Wildeshausen as well as for the Weichbild Harpstedt . Neustadt am Rübenberge could have been attributed to the Bremen municipal legal family .

Development of Bremen law in the Middle Ages

Development up to the emergence of the city law

In the development up to the codification of the city law, the development of the city of Bremen into a city that could independently legislate and the development tendencies of the law in the city are to be distinguished. The former is the prerequisite for it to have its own city law. The internal development that happened next to it largely determined the content of the codification.

Development of the township into a municipality with its own legislation

In 789 at the latest, Bremen became the seat of a bishop in connection with the missionary work of the Saxons . In 848 Bishop Ansgar took over the Bremen diocese and united the dioceses of Bremen and Hamburg after the Vikings attacked Hamburg. This is how the Archdiocese of Bremen was formed , which took on the role of feudal lord in Bremen. On June 9, 888, the then archbishop gained Rimbert the Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia the market , coin and customs law . As a result, the Bremen citizenship later only faced the diocese and not other secular rulers. In 965 Otto I granted market rights to the diocese again without recourse to Arnulf's deed; this award was 988 by Otto III. approved. These documents but can already deduce that the resident merchants not to the hearing part of the diocese, but must have been in another jurisdiction inclusive relationship.

For the 12th century , the development of a city ( civitas ) that was at least linguistically separated from the diocese can be proven. In 1139 two episcopal documents speak of civitas and cives (citizens); In 1157 there was a donation to the cathedral chapter of a secus vallum in platea superiori civitatis , that is, a house on the wall of the city's Obernstrasse ; the so-called pasture letter of the archbishop of 1159 regulates the demarcation of the cattle pasture of the citizenry to archbishop colonists. The letter was handed over to a citizens' committee, which can thus be seen as the city's lobbyist. In disputes with Henry the Lion , the city then appeared as a party, even if it felt compelled to fall back on the mediation of the archbishopric. After the fall of Heinrich in 1180, Archbishop Siegfried I of Anhalt took the bishopric. In 1181 Siegfried expressly waived port fees , protection and peace funds in favor of the universitas civitates nostre .

Siegfried's successor Hartwig II obtained a privilege from Friedrich I Barbarossa ( Gelnhauser Privilege ) in 1186 , in which the city was then granted soft image rights. With the granting of these rights, an independent development of a Bremen city charter was officially possible in the first place. Bremen then later even successfully called Barbarossa on the basis of this document for help against harassment by Archbishop Hartwig. Around 1200, the citizens of Bremen came out into the open by making a settlement with the County of Altena . In an agreement known as concordia with Archbishop Gerhard I , the city and the archbishopric then face each other for the first time as equals in 1217. In this document, the archbishop confirms, among other things, that two citizens may confirm the applicable law as their right in the event of a dispute between him as the town lord and the township. Under his successor Gebhard II , the city was able to achieve considerable progress in its legal independence. In 1225, seven consules were named as representatives of the city for the first time in a document from this archbishop . In 1233 Bremen was able to take advantage of Gebhard's dispute with the Stedinger farmers. As an advance payment for the participation of the civitas , King Heinrich VII (son and co-regent of Emperor Frederick II ) and the archbishop granted the Bremen citizens privileges and Bremen as a constitutional community its independent rights and city charter. However, in 1246 the consules Bremenses et commune totius civitates Bremensis in Lesum had to declare that they would only issue regulations ( wilcore ) at the expense of the archbishop in agreement with the diocese (so-called Gebharhard reversals ). At the same time, the court was recognized as the only court by a bishop with a bailiff , a step backwards compared to the Gelnhaus privilege, which had made the civitas subject to imperial jurisdiction. This waiver was partially repealed in 1248 and later practically negated by pledging the bailiff's right.

In fact, the city developed in the direction of an imperial city independent of the feudal lord . However, this status was only documented much later by the Linz diploma of 1648. It was not until 1666 that the Kingdom of Sweden recognized this status as legal successor to the archbishop in the Peace Treaty of habenhausen .

Internal development of the law of Bremen before the codification

During the second half of the 12th century and then increasingly in the 13th century , the recording and finally the codification of city rights in the Holy Roman Empire became increasingly common . The background to this was, on the one hand, that in the increasingly complex social life in the cities there was a need for increasingly differentiated regulations that ultimately could hardly be retained by individuals in their entirety. Another reason was that it was increasingly demanded that the existence or non-existence of rights also had to be proven. The codification of Bremen's city law is also part of this development. Here, however, the medieval worldview must be taken into account. According to this, law could not be shaped by legislative intervention, but according to this theocentric worldview, law was ultimately given by the divine order. It just had to be "found" and, if necessary, recorded. According to the understanding of the time, it was primarily a codification of the previously existing customary law , whereby this also included the inclusion of the traditions of Roman law . The regulations laid down in the city charter had basically two sources: First, the rights conferred by the feudal lord and, second, the arbitrariness as a right adopted or adopted from legal practice, e.g. from earlier judgments or from resolutions of the council . The boundaries of these sources could be fluid - privileges could be adopted as arbitrariness, but arbitrariness could also be confirmed by privilege.

The city law should fall back on older sovereign regulations. Of the privileges granted, the Gelnhauser Privilege of 1186 is the oldest granted right that was used by adopting similar regulations on civil rights. The 1206 archiepiscopal regulation to abolish the straight line in inheritance law can also be found in city law. On the other hand, tendencies towards the arbitrary setting of law - for example by the Gebharhard reversals of 1246 - were suppressed. These protested expressly against legislation by the city in the area of criminal jurisdiction, which is lucrative through fines.

Codification of Bremen Law 1303–1308

The group of people who tackled the codification in Bremen is named in the city charter of 1303. There it is mentioned that all 14 members of the council agreed to resign from town charter. According to these agreements, the council and mene Stad appointed 16 additional people from the 16 districts that had to carry out the codification. The city council and the additional sixteen then formulated the city law. The councilors and the representatives of the city quarters all belonged to the leading families of the city who were competent at the time. Many of these families either came from the ministerial families of the Bremen archdiocese or were closely connected to the ministerial families . Merchants did not yet belong to these families. Any further background can only be assumed, since the sources are silent on this point. It is certain that the codification took place against the background of considerable tension in the Bremen upper class, from which the impetus for the codification came. In 1304, the respected councilor Arnd von Gröpelingen was murdered in his house by sons from influential families. There followed significant arguments about the punishment of the perpetrators, which led to the council feud of 1304/1305 and the expulsion of several influential families. Families whose members had participated in the codification were also affected. Schwarzwälder draws the conclusion from this that the victorious families made use of the codified law; Others claim that the codification was an attempt to counteract the tensions. The first codification of the city law took place over a period from December 1, 1303 to December 21, 1308. The core of the city law was, however, already completed in the course of 1305.

Further developments

As a result, the city law codification was continuously expanded and supplemented by amendments and ordele (judgments) of the council. The amendments to the council constitution were of particular importance. The original city law was largely silent on this issue. Fundamentally, then, was the determination of the council's capacity and the rules according to which the council was to be supplemented from 1330. A man who was able to give advice had to be born free and in wedlock, be at least 24 years old and own land worth 32 silver marks . Since the suppression of the so-called banner run , an uprising of the guilds against the supremacy of the merchants, every citizen had to declare his loyalty to the Senate by taking an oath in order to gain citizenship .

New codifications of 1428 and 1433

Bremen, which was also expanding outward in terms of power politics, experienced considerable setbacks in the first third of the 15th century. While it had initially prevailed against various Frisian chiefs and also against the county of Oldenburg to secure shipping on the Weser in Rüstringen , Bremen was driven out again by a coalition of Rüstringen Frisian chiefs . As a result, there was considerable unrest within Bremen, which ultimately led to the overthrow in the city. The council was forced to resign and the citizens elected a new council from among their number. As a result, Bremen was excluded from the Hanseatic League in 1427 and the imperial ban was imposed on the city. In 1428, as a result of the overthrow, the town charter was re-codified. In terms of content, the old regulations are largely taken over, but restructured, only the Council constitution was completely redrafted. For the first time, the attempt is made to structure the individual regulations thematically. Only the original city law is recorded without later amendments, but this remains unchanged in substance. What is significant, however, is the new regulation of the composition of the council, which in all likelihood was the real reason for the new codification. The internal unrest continued, however, and ultimately led to the execution of the mayor Johann Vasmer . In the wake of the execution, supporters of Vasmer and members of the former council families allied themselves with surrounding powers. They manage to take the city and take power again. As a result, there is a new codification. This now takes the novellas into account, if not all, and rearranges the text. However, the "new" structure largely takes up the old structure from 1303, Sections III. (Statutes) and IV (ordinances / judgments) can be found in the codification. The old council constitution was reverted to in 1433 and the council order of 1398 was essentially reinstated and integrated into the city law. This version should then represent the conclusion of the Bremen city law and continue to apply. After returning to the old conditions, Bremen was accepted back into the Hanseatic League and was able to turn away from imperial ban in return for a not inconsiderable atonement against Vasmer's heirs.

Further developments in modern times

Further developments through the knowledgeable roles

With the version of 1433, the codification of Bremen's city law was finally concluded. The further development took place through the practice of jurisprudence , which largely lay with the Council, and through regulations and statutes of the Council. The new regulations were announced at a citizens' meeting (“ Bursprake ”) called annually at Laetare (3rd Sunday before Easter ) in front of the Bremen town hall . At this meeting the applicable statutes and ordinances were read out. The reading took place initially from the town hall arbor. This arbor was located above today's entrance to the Ratskeller . It was later carried out from the town hall's gold chamber. While all regulations were read out at the “Bursprake”, the practice arose in the 15th century of only reading out police regulations . It is assumed that all such regulations were collected independently as early as the 14th century. In Ratsdenkelbuch a copy obtained from 147 ordinances and statutes of the 1450th The memorial book was created by the council in 1395 in order to record important documents for the city. This section was initially named "De olde kundich breff", later this heading was supplemented by "or Rulle". In 1489 a supplemented copy of the rule of 1450 was created and expanded in the following years. Here were pieces of parchment sewn together so that the role was getting longer. In total it gradually contained 225 articles. The last addition dates from 1513. With a width of about 15 cm, the entire roll had a length of 6.93 m at the end. This collection of laws was referred to as the “Knowledgeable Role” (or “Knowledgeable Rulle”). Overall, it can be assumed that due to the German legal form of the Bremen city law, the publication of legal norms was of no importance for the effectiveness of the law. This differentiated the north German-Saxon city law of Bremen from southern German city law families, which were more strongly influenced by the corresponding ideas of Roman law through northern Italian influences .

Although the Knowledgeable Scroll , which was used to read out the applicable law, was the basic legal document, not all legal changes are noted on it. Rather copies served this as a firm specimens in the form of booklets. The oldest surviving copy of the law firm contains the changes up to 1549. A second copy of the law firm contains the changes from the second half of the 16th century . This was followed by a copy with the changes from 1606 to the middle of the 17th century and finally a copy with changes between 1656 and 1756. In practice, the council had also switched to publishing ordinances and "proclamations" in writing. This was made possible by the church schools established as a result of the Reformation and the associated increase in literacy among the population. After the uprising of 104 men in 1523 and the restoration of rule of the Senate in the following year, the New Concord was passed in 1534 , which, in addition to specifying the old order, also contained cautious innovations. The oldest surviving ordinance of the council, which was distributed in printed form, was the Bremen church ordinance , which was also drawn up by Johann Timann in the aftermath of the events of 1530/1532 and issued by the council as an ordinance. This was given to all pastors in Bremen in printed form from 1588. The council's first printed proclamation also dates back to 1588 and concerned the establishment of weekly markets in the towns of Lehe and Neuenkirchen, which were then part of Bremen . However, the regulations and proclamations were more often forgotten due to non-repetition or were no longer regarded as binding. 151 was therefore followed by the printing of an, albeit unofficial, “collection of various ordinances relating to trading, shipping and policey matters of the Kayserl. Freyen Reichs-Stadt Bremen started out in older than more recent times ”by the council printing office. The reading of the Knowledgeable Scroll in the Bursprak had become impractical and was finally abandoned by the council in 1756. Rather, he had an edition of the Kundigen Rolle printed in 1756, to which the Neue Eintracht from 1534 was also added. In 1810 the regulations that had been issued and still valid were published again. From 1813 onwards, an annual “ collection of the ordinances and proclamations of the Senate of the free Hanseatic City of Bremen ” should take place. From 1849, following the March Revolution of 1848, the legal gazettes of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen were published annually.

Reforms and attempts at reform

In 1532 there was a brief revolutionary overthrow with the uprising of 104 men , power had been taken over by a new council of 104 men. In contrast to 1429, however, no new city law has been formulated. In the end, the new regime did not last long either. Already in 1534 there was a new harmony and thus the restoration of the old conditions. Although Bremen's city law was concluded with the codification of 1433, which was also emphasized in the Neue Eintracht , at the latest after the rule of 104 men 1530–1532 and the Neue Eintracht of 1534, the city law was in need of revision in the 16th century. Since the 16th century, several contracts were signed between the council and the municipality called Eintracht , in which individual articles of city law were interpreted.

The mayor Heinrich Krefting and his nephew and Bremer Syndicus Johann Wachmann the Elder have made a special contribution to the further development of city law. In 1590 Krefting was still a professor at the University of Heidelberg and wrote a pamphlet on the reform of Bremen's municipal law ( Dispositio et Commentatio statutorum reipublicae Bremensis ). In December 1591 he was elected a council member and finally in 1605 even the mayor of Bremen. After joining the council, Krefting began to reform. The first success here was the reform of the sections on criminal law in 1592. This was adapted to the Embarrassing Neck Court Order ( Constitutio Criminalis Carolina ) of Charles V , which came into force in 1532 . The great reform he was striving for did not materialize.

Krefting and Johann Almers, who worked with him, assumed that Saxon law only ever applied insofar as it was expressly adopted. Otherwise, the practical application of the common law strongly influenced by Roman law should be assumed. The draft of a Verbeterden Stadtbook was based on this assumption, which was initiated by Krefting, theoretically influenced by his Dispositio et Commentatio and created in concrete terms by Almers. The draft provided for a complete reorganization and revision on the basis of the most modern knowledge at the time. In the debates with Wittheit as the entirety of all councilors and mayors, Krefting was initially able to prevail in large parts despite considerable conservative resistance. But when the citizens' committee called in came out in favor of separate debates according to parishes and there was considerable opposition, the council withdrew the draft of the new city law. Krefting and, to a lesser extent, Almers, then, as glossators, wrote a gloss on the city law of 1433, in which they urged a partial amendment of at least three sub-areas: The regulations on insolvency and debt bondage were to be softened in accordance with the general rules in the Hanseatic League ; the official supervision of guardians provided by the Imperial Police Order of 1577 was to be introduced; the regulations on adultery should be tightened in accordance with the Reich Police Regulations and no longer be prosecuted as a mere administrative offense. The reform attempts were interrupted by Krefting's death in 1611, but later taken up again by Krefting's nephew, Johann Wachmann the Elder, and continued in glosses. Wachmann started here in 1625. The work was originally intended as a memorial for his esteemed uncle. He initially summarized Krefting's glosses on Verbeterden Stadtbooks with Verbeterden Stadtbooks ; he completed the corresponding work in 1634. In later editions of this Codex Glossatus, he added his own glosses and, after Almer's death, also added glosses from Almers. Many copies of this work have been preserved, indicating that it has been used extensively in legal practice.

19th century: development and replacement

Napoleonic Wars

At the beginning of the 19th century, all rights of the cathedral chapter in Bremen expired in accordance with Section 27 of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss . Along with Augsburg , Lübeck , Nuremberg , Frankfurt and Hamburg, Bremen was one of the few remaining imperial cities . With the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Bremen became a sovereign state. This resulted in the city law of the Hanseatic city being changed from particular law to the law of a sovereign state. As early as 1808, however, Bremen was forced by France under Napoléon Bonaparte to introduce the Code Napoléon , which replaced the old city law in private law . On December 13, 1810, France annexed Bremen, despite the previous policy of neutrality . Bremen thus initially became a French provincial town, to which French law applied in full. The occupation was ended on October 15, 1813 by the invasion of General Tettenborn . Of the changes made by the Code Napoléon, the introduction of a registry office remained , which was responsible for the registration of personal affairs (birth, marriage, death). A commercial court , the chamber of commerce and a trading exchange were established .

Restoration of the city charter

As early as November 6, 1813, the city council was reconstituted and reintroduced the old law. The council relied on the continuity theory developed by Johann Smidt , according to which Bremen law was old German and had grown on Bremen soil; the forced changes by Napoleon were only a temporary act of robbery without meaning. However, the council promised to submit proposals for changes to Bremen law "as soon as possible". As a negotiator for the city, Smidt was able to achieve that the sovereignty of Bremen was recognized at the Congress of Vienna . With this, the Restoration had initially prevailed, but a reform party had also formed, which primarily pushed for constitutional changes. The changes proposed by the Council were rejected by the Citizens' Convention, which traditionally advises separately by parish . Rather, a counter-proposal was drawn up by a preparatory commission for the constitution negotiations. This proposal envisaged a departure from traditional communalism and the formation of a bicameral parliament , separation of powers with a clear separation of judiciary , legislative and executive , the council should only have an executive function. As early as 1814, a mixed constitutional deputation was formed to discuss possible contemporary changes. With the federal act , Bremen had also committed itself to creating so-called “state constitutions”. However, even the representatives of the Reform Party did not envisage universal suffrage , even if a third of the citizens were to be elected. Rather, the right to vote should continue to be class-oriented, but it should now also be extended to craftsmen. On the whole, however, the forces concerned with the Restoration prevailed in the deputation, while the reform forces got bogged down in individual problems. The main report of the deputation of 1814 provided for a sharper delimitation of the competences of the council and the citizenry, otherwise it essentially remained with the old constitution. As a result - for example in the aftermath of the July Revolution of 1830 in France - there were repeated debates on the constitution, but these debates were fruitless. After all, in 1837 a new draft constitution was drawn up.

Even if a constitutional amendment could not be politically implemented, the debate about the constitution led to a scholarly examination of the legal history of Bremen. The lawyer Ferdinand Donandt (1803–1872) wrote his two-part work “ Attempt at a History of Bremen City Law ” in 1830. This work was in the tradition of the Historical School of Law and was based on medieval documents. Donandt was a representative of the liberal reform forces. The purpose of the work should be to have the necessary knowledge to redesign the constitution when drafting a constitution and not to act too hastily.

Revolution of 1848 and renewed restoration

Even before the March Revolution of 1848, a middle class movement had formed in Bremen. This was initially carried by master craftsmen and teachers. In November 1847 204 people founded a “citizens' association” with the aim of changing the constitution. Within a few months, the association, as the first formally founded party in Bremen, grew to 1,320 members, mainly through the entry of lawyers and merchants. The Bremen Citizens 'Association led the revolution of 1848 in Bremen. In a March petition on March 5, 1848, universal suffrage , the establishment of a citizens' parliament and freedom of the press were called for. This was supplemented with demands for the separation of powers, independent courts and the introduction of jury courts . The petition was signed by 2,100 citizens. As a result, a constituent assembly was formed after a general election. The constitution that was then formulated was heavily influenced by Ferdinand Donandt , who was to become vice-president in 1848 and finally president of the citizenship and thus of parliament in 1852. With the "Constitution of the Bremen State" of March 21, 1849, the council constitution provided for in the old city law was replaced.

Overall, however, the constitution was a combination of new and old elements. For example, the constitution provided for a dualism in the area of the legislature , in which the Senate, whose members remained in office for life, should be empowered to legislate alongside the citizens. Donandt viewed the Senate as an "element of calm". The Senate should be composed of five lawyers and five business people.

On March 29, 1852, the Senate unilaterally decreed the repeal of the constitution. He could appeal to a possible threatened intervention by the federal government, especially Prussia , and structural changes demanded by the federal government. An eight- class suffrage was finally introduced for the citizenry in order to strengthen the class forces. The Senate essentially got the old rights back. Proponents of this change relied on the fact that the task of the seaside towns was to safeguard German foreign trade, which was only possible with due consideration of the commercial elements. This state constitution was ultimately only abolished after the defeat of the Bremen Soviet Republic by the "Constitution of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen" of May 18, 1920. The constitution of 1920, as well as the state constitution of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen of 1947, deliberately strengthened the position of the citizens of Bremen as a parliament, contrary to the traditionally strong position of the council under the old council constitution.

Replacement of criminal and civil law by imperial law

Bremen became a member of the North German Confederation founded in 1866 and joined the German Empire in 1871 . The legislation of the North German Confederation already partially supplanted the older provisions of city law. With the accession to the German Reich, the Bremen city law became particular law again and was finally largely replaced by the codifications of the Reich.

First of all, the trade regulations of the North German Confederation of 1869 should be mentioned. The trade regulations replaced the law of commercial employees of the member states of the federal government with more modern regulations based on the liberalism of the 19th century. Employment relationships were now normal contractual contracts for employees of the economy . Section 152 of the Industrial Code expressly permitted the formation of trade unions as representatives of the workers. This was later supplemented by regulations of the Reich on social security and occupational safety .

The Imperial Criminal Code was passed on May 15, 1871, thereby bringing about uniform regulation of criminal law throughout the German Empire. With the entry into force of the penal code on January 1, 1872, the criminal law provisions of the city law therefore lost their significance. This was followed by the Reich Justice Laws , which came into force on October 1, 1879. These laws created a uniform judicial structure and uniform procedural law . The previous court order in Bremen was replaced by the establishment of the Bremen Regional Court and the Bremen Local Court , which had to comply with the new procedural rules.

The other civil law provisions of particular law were replaced on January 1, 1900 by the codification of private law in the Civil Code .

With the exception of the council constitution, which was finally replaced in 1920, this replaced the city charter of Bremen.

Content design of the city law

The Bremen city law from 1303 is written in an early form of Middle Low German .

In terms of content, Eckhardt assumed that Bremen's municipal law was essentially a record of pre-existing law. However, contrary to this assumption, around a quarter of all provisions are direct adoptions from Hamburg's city law, the so-called Ordelbook (around 1270), including a block of 45 provisions. Hamburg law, for its part, had borrowed considerably from the Sachsenspiegel Eike von Repgows . 23 of the 45 mentioned regulations were already included in the Sachsenspiegel.

The Sachsenspiegel itself claimed the right to map the whole of Saxony (e.g. today the area of the federal states of Saxony , Saxony-Anhalt , Lower Saxony and the Westphalian part of North Rhine-Westphalia ), but there were considerable gaps that had to be addressed by the city charter. In the Sachsenspiegel, for example, the citizenship, which is important in the cities, was almost completely missing. This was an essential aspect that needed to be taken up in the codification of city rights.

The city law book was divided into four sections, with sections IV and a considerable part of section III being taken over from the Ordelbook of Hamburg and thus partially receptions of the Sachsenspiegel. However, a selection was clearly made in the takeovers. Section I contained regulations on property , guardianship and inheritance law , the second section, entitled “Emergency Weirs”, criminal law provisions. The first section has many references to common law and takes up some older legal clauses. The third section ("Statutes") shows a mixture of older provisions and those that could only be formed in the 13th and early 14th centuries. The fourth (and longest) section is headed “Ordelen” (judgments) and includes provisions on court rules , the law of evidence and individual provisions on private and contract law that originate from judicial practice . Section II has origins in the Corpus iuris civilis and thus Roman law , which were mixed up with ideas from the older customary law (e.g. the provision on rape ).

Council Constitution

The urban community had developed as a legal entity in the 12th century. With the Barbarossa privilege of 1186 at the latest , men and women who owned property for a year and a day could appeal to the principle of “ city air makes free ” and refer to their own civil rights. The organization of this community of citizens can be found for the first time in a customs exemption document Archbishop Gebhard II. From 1225, since seven consules of the city are named there as such. These consules do not act as councils , but can be thought of as members of such an institution.

A de facto council constitution had already been developed before the codification, even if it had not yet been put into writing. The upper social class of the bourgeoisie was made up of a few patrician families who were alone able to advise. While the council was initially formed from members of the entire bourgeoisie, it has now essentially supplemented itself. The version of the city law of 1303, however, contained hardly any regulations on the constitution of the council. The council consisted of fourteen people between 1289 and 1304, as can be seen from the introduction to the city law of 1303. A list of the families displaced in the wake of the unrest of 1304 was also added to the city charter. From 1304 the council consisted of 36 members, with only one third exercising the office annually. In 1330 there was the first written regulation of the addition of the council and the council ability. These provisions were subsequently incorporated into the city law. Here, the council with provisions on minimum wealth and the ban on exercising a craft while membership in the council was limited to the wealthy classes. In 1398 these council regulations were amended. Then 4 mayors and 20 councilors formed the Wittheit or the council. The governing council was formed from two mayors and ten councilors.

With the overthrow of 1428 the council constitution was reshaped, but restored with the restoration of 1433 and integrated into the city law. From the constitution of 1428 only one regulation remained, according to which a close relationship to a council member could prevent the admission.

Jurisdiction, especially criminal justice

The court practice in Bremen was characterized by a certain dualism in terms of jurisdiction. In addition to the jurisdiction of the council, there was for a long time, ultimately even beyond the existence of the diocese of Bremen , jurisdiction by the bailiff of the archbishop. The jurisdiction of the bishop arose with the establishment of the diocese. Since the 10th century at the latest, it had been a high-level jurisdiction and had a royal spell . Since the bishop had no secular jurisdiction as a clergyman, he was represented as liege lord for secular jurisdiction by his bailiff. By Barbarossa - privilege of 1186 then the municipal institutions were gradually developed that should compete with the jurisdiction of the bishop. With the increase in the independence of the town's consules in the 13th century, efforts were made to encourage the town organs to participate in the judiciary and, ultimately, to resolve disputes between the citizens. This encompassed not only private law in the modern sense, but also internal affairs of the constitution of the citizenry or the police law . The Gebhard reversals of 1248 mainly opposed the fact that the city institutions had also unilaterally acquired criminal judicial functions. However, the document also shows that the bailiffs had already resorted to the expertise and cooperation of council members in their jurisdiction. According to this, the bailiff ruled in private and criminal matters, but in civil law matters always with the participation of representatives of the council. In the city law of 1303 it is emphasized that the jurisdiction of the archbishop should not be reduced by the city law. At the same time, however, the competence of the Council for disputed legal matters is underlined. This jurisdiction then expanded again into criminal law areas and, with its more modern forms, replaced the more complicated jurisdiction of the bailiffs. A case of bigamy has come down to us for 1330 , in which the bailiff referred the whole procedure to the council. The parallel court channels meant that criminal trials were sometimes pending before both court channels until the 16th century. The coexistence of these legal way was a privilege only in 1541 Charles V ended. A lower court for disputes below 200 guilders and a higher court for disputes over 200 guilders were then set up. Even after the privilege, however, the episcopal jurisdiction remained responsible for members of the cathedral immunity and for blood and throat jurisdiction . At least the involvement of the bailiff was therefore necessary in cases of blood and neck jurisdiction. The Council had never insisted on jurisdiction here. Only in connection with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss was the last remnants of the bailiff's jurisdiction waived. The first proceedings that ended with a death penalty, which the council carried out alone, only took place after the main conclusion of the Reichsdeputation. It was the murder trial against Gesche Gottfried from 1828 to 1831.

The court of the bailiffs took place in the open air, the council discussed its legal cases behind closed doors in the council chairs of the Bremen town hall . The Vogtgericht initially met on the market, which initially took place south of the churchyard of the Liebfrauenkirche . The reason for this was that the market court was connected with the jurisdiction . In documents from the 14th century, the place of jurisdiction of the bailiffs is referred to as "the four benches". From mentions in sources from the 13th and 14th centuries, it can be concluded that the place of jurisdiction of the Bailiwick was located on the west side of today's town hall. The name “Schoppensteel” for the space between today's town hall and the Church of Our Lady also indicates a place of court there. Places of execution, such as the pillory or the topping-out stake, were in the immediate vicinity. With the new construction of the town hall in 1405, the place of jurisdiction had to evade the bailiffs. From then on, the court sessions of the bailiffs took place in the second arch of the town hall arcades. The Vogtsgericht met regularly three times a year (unofficial thing ) or when necessary due to pending legal cases (required thing).

The criminal procedure in Bremen followed the principles of the inquisition procedure , even in the 19th century, when this procedure had been replaced by more modern forms in other states. It was only in connection with the trial of the poisoner Gesche Gottfried that the principles of free assessment of evidence were introduced for the first time . On the other hand, Bremen was the first German territory to introduce imprisonment as early as the 17th century and introduced a breeding and workhouse modeled on Amsterdam , and in fact dispensed with torture.

Criminal law

The criminal law provisions of the Bremen city law provided for a significant increase in penalties compared to the earlier criminal law of the early and high Middle Ages in Bremen. While earlier law gave preference to paying fines , which was also a source of income for bailiffs and bishops, more modern city law provided for beheading , hanging , wheeling , boiling or burning as the death penalty . When corporal punishment were provided: cutting off his right hand, burning of a key in the cheek, piercing the hand with a knife and flogged with rods. In principle, criminal charges had to be brought against criminals ( accusation principle ), only with the renewed codification of the city law in 1433 were some provisions on the breach of civil peace inserted between sections III and IV. These were manslaughter, physical abuse, assault and injury with sharp weapons. For the first time, these provisions stipulated that criminal prosecution was to be carried out ex officio for these offenses .

An adjustment to later legal developments took place at the instigation of Heinrich Krefting in 1592. The criminal law and criminal procedure law were adapted to the Embarrassing Neck Court Code of Charles V , which came into force in 1532 . The Carolina was based on Roman legal models. Thus, through the reform of the relevant sections, bodily harm and insult , which had previously been understood as an injustice directed against the general public, became private law crimes . As a result, the city had to pay a fine and at the same time compensation to the injured party. There was no corporal punishment for merely drawing out a sharp weapon; now a fine and expulsion from the city for year and day has been provided for this. In criminal proceedings, the outdated regulation was deleted to free oneself from the evidence provided by an oath of innocence .

witchcraft

In the Sachsenspiegel there was a provision on dealing with witches . This was taken over into the Hamburg city law with a significant restriction in terms of evidence and via this into the Bremen city law: The witch must have been caught in the act. Overall, with this single provision in the Bremen city law on witchcraft, only the magic of damage was punishable. In Bremen, therefore, there were only relatively few witch trials during the time of the witch hunt . Although there was a double legal process before the council and the Vogteigericht, in fact the Vogt referred such processes to the council because of the difficulty of the legal matter. As can be seen from two legal instructions to the City of Oldenburg, the accusation principle applied there , i.e. it was necessary for the injured party or another person to bring charges. The water sample otherwise handed down from the area around Bremen as proof of God because of witchcraft was omitted and was in some cases expressly rejected. The criminal justice system was expanded after the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina was enacted in 1532, as this imperial law contained considerable provisions against witchcraft.

Family and inheritance law

Bremen law, for example, shows a noticeably less differentiation in matrimonial property law than the Sachsenspiegel, for example the right of the (also divorced) wife to use the husband's property. One difference concerns the prohibition provided for in Hamburg law against expelling the pregnant or pregnant widow from the man's estate; Bremen law deals exclusively with the wife, there is no reference to widowhood. Here, however, it is unclear whether the protection of pregnant women should be extended to the wives. An oversight is excluded, however, as this passage was adopted unchanged in 1428 and 1433.

The original law of inheritance in Bremen provided for an undivided community of fathers and sons. However, this right was already dissolved under Archbishop Adaldag (937-988) in favor of a head community, which eventually also included the wife and daughters. The city law therefore provided separate rights for the headboards of the wife and husband. However, the children did not have a departmental claim against their father. Daughters and sons were treated equally when calculating the header. The Bremen law differed from the generally accepted Saxon law in that the straight line was not intended as a special line of succession for women. This was due to a repeal that took place in 1206.

Service and servant law

If marriage law and inheritance law lag behind the Sachsenspiegel and Hamburg city law, the law on servants and servants is much more developed. This can be traced back to the fact that in urban life with the more differentiated economy what is now called individual labor law had a more significant meaning than in the general social life of the Middle Ages.

In the section on feudal rights, the Sachsenspiegel expressly dispensed with a detailed description, as there would be too many different forms. However, the remarks on land law contain provisions on continued payment of wages , repayments of wages , the liability of the master for damage caused by his servants and for the servants' gambling debts. These sections were taken over from the Ordeelbook. The Bremen city law, however, provided for additions and deviations: According to Bremen law, a servant could demand full wages if he was dismissed, provided he was not responsible for the dismissal. On the other hand, if he resigned himself, he had to pay compensation for the lost services from the end of the employment relationship, which at Sachsenspiegel was still double what the employer had promised as remuneration. In Bremen and Hamburg, the employment law provisions were also extended to women and in Bremen they were even treated equally in terms of employment and civil law. There are regulations on minimum wages (mênasle) amounting to four shillings . There are also regulations in the event of the death of the employer or the employee. The regulation in Bremen city law that journeymen were to be maintained by their masters in their health and also to be cared for during illness represented a preliminary stage in the development of today's labor law.

Shipping and maritime law

For a maritime trading town there is naturally a certain interest in regulating shipping and maritime law issues. In the medieval town charter, a different regulation from the general law in maritime law was quite common. For example, general law provided that whoever caused damage had to compensate for it. A fault played here not matter. In shipping and maritime law, a division of damage between merchants and shipowners or ship masters was common - and also provided for in Bremen law. In the codification of Bremen's municipal law, however, there are only three regulations with a corresponding reference. One was already in the original version, the other two were early novellas . This means that the law of the sea in Bremen is underdeveloped in relation to the law of the sea in other northern German maritime trading cities. The city law of Schleswig (created around 1200) contained nine provisions, the city law of Flensburg from 1284 eight, the Lübeck city law thirteen and the Hamburg city law probably thirteen regulations. The regulations in Bremen law tended to be more favorable for the skipper. The law of Bremen stipulated that the freight risk was to be shared between the skipper and the merchant. Half of the freight charge was to be paid at the start of the journey and the other half after the journey had been successfully completed. According to later Hanseatic customs, the skipper bore the full risk, as he was only rewarded after successful completion.

However, a copy of the Bremen city law that can be dated between 1335 and 1349 has survived, which includes, among other things, a large number of maritime legal clauses as an appendix. Overall, these sentences represent a fully developed law of the sea. This law of the sea is largely borrowed from the Hamburg law of the sea. These legal provisions reached Bremen via the trade with Flanders , in which Hamburg was the leader. The Bremen merchants resorted to the existing Hamburg facilities and had to adapt to Hamburg law. At first this Hamburg law was only the law and the commercial practice of the Hamburg Flanders drivers who developed it. This adaptation to foreign law was then adopted into practice in Bremen. This was also made easier by the fact that the law of the sea as a whole is less a locally bound city law, but to a large extent more international traffic law and was seen accordingly at the time. However, the originally Hamburg law only became officially Bremen city law with the adoption of pan-Danish maritime law in 1378.

However, with the increasing importance of the overall Hanseatic shipping law and the decline of Hamburg's priority position in Flanders trade, this maritime law increasingly fell out of use. With the overall Hanseatic Ship Regulations of 1482, particular city law regulations finally largely lost their significance. In 1575, however, the Bremer Schiffergesellschaft issued its own ship regulations. This was taken over as "Ordonatie". In 1614, parts of these regulations were incorporated into all of Hanseatic law.

Weights and measures

Measures and weights were originally part of the market rights granted by the emperor to the archbishops of Bremen. However, the citizens of Bremen also began to become increasingly independent in the marketplace, for example when Frederick I (Barbarossa) issued the Gelnhausen privilege in 1186. This expansion of competence by the citizens of the city also affected the measurement, weight and calibration system . As part of the Gerhardische Reversals of 1246, the city was forced to abandon its own statutes. Now frauds in measuring and weighing by the episcopal bailiff should be punished together with a councilor, the income from this should be shared. A "new bushel " was abolished, the traditional episcopal dimensions were reintroduced. In a contract between the city and Archbishop Hildebold from 1259, this condition was confirmed again.

The following regulation was included in the codification of the city law:

“En jewelik schal ok lift right mate and have right weights. (Everyone should also have the right measurements and weights) "

The measure, weight and calibration system was subsequently further developed in the Kundige roles of 1450 and 1489, among other things . An important regulation in this development was the granting of the Krameramt in a privilege of August 15, 1339. The sworn magistrates were entrusted with the later function of the verification masters. In addition, a fine of one Bremen mark of silver (equivalent to 233.856 g) to be paid in favor of the council was introduced. The first measure and weight order was laid down around 1470 with a supplement from 1487 in the Ratsdenkelbuch .

After it to doubt the neutrality of by the guilds used sworn masters had come in 1600 appointed by the Council sealers were used. The verification masters, designated as Kemper in documents from 1647 on , were not paid, but were dependent on verification fees and the sale of calibrated weights and measures.

The municipal legal family

Of the localities that could be assigned to the city legal family, only four ( Delmenhorst , Oldenburg , Verden and Wildeshausen ) already had city status in the Middle Ages. In the case of Nienburg , the city status can already be proven in the 13th century, but it is unclear to which family Nienburg can be assigned. Due to the location, membership of the Bremen municipal legal family would be possible. Also with Hoya and Rotenburg (Wümme) belonging to this family of municipal rights would be conceivable, but this cannot be proven. For Neustadt am Rübenberge there is an unspecified letter to the Bremen council , in which the Neustadt council asked for legal advice. In this way, relationships can be demonstrated that also have a certain probability of belonging. However, this is not certain, since legal advice could also be obtained regardless of whether or not you belong to a legal group. The localities for which the affiliation can be proven are located in a relatively small area around the Hanseatic city of Bremen. The size of the area is about 40 km from north to south and about 80 km from west to east. Adjacent municipal law areas in the north and east were the Lübische law, inspired by the Soest town law, and the Hamburg town law family, as well as the town law families of Lüneburg and Braunschweig . In the south were the legal districts of the Westphalian city rights families of Dortmund and Münster . Finally, in the west, the area of Friesland with its own legal tradition bordered on this area of Bremen city law.

Verden (from 1259)

Verden, as the seat of the Bishop of Verden , was granted city rights by a privilege of the bishop on March 12, 1259. The place had previously developed into a city at the end of the 12th century. From the document, however, it can be deduced that Verden must have already had a town charter. The document contains, among other things, a regulation on the legal principle “ City air makes you free ”, which deals with the contestation of the freedom of a citizen according to this principle. According to the document, the reference point for this regulation should be a requirement of the existing city law. The handling and formulation of the Verden deed show clear similarities with the formulation in the Bremen Barbarossa privilege of 1186. Haase concludes from this that the possibility of influencing the city charter of the near verdict through the legal practice of Bremen may have existed for some time. At the end of the document, the people of Verden are referred to the council in Bremen for legal advice: a typical feature of belonging to a family of municipal rights. There are no further direct references to an assignment to the municipal legal family. There is only a request for legal instruction from 1511. However, a practice of verbally obtaining instructions from nearby Bremen is likely.

On May 1, 1330, the city council, in collaboration with a committee of the city's citizens, issued a statute collection. This collection represented the city's own legislation. However, the collection shows no direct reference to Bremen law. There are only three articles that agree; However, two of the articles can also have common origins under land law, the third relates to a statute that is otherwise widespread. From a tripartite division of the council, which is typical for the cities of the Bremen legal family, but otherwise very unusual in northwest Germany, influences of Bremen law can nonetheless be identified. In the Verden city law book of 1433 there is only one article with a recognizable reference to Bremen city law. The situation is different with the Verden statutes of 1582. These show considerable correspondence with the Bremen city law of 1433. The structure of the “Statuta Verdensis” is similar to the Bremen city law of 1433. Of the total of 182 articles, 113 articles correspond to the provisions of Bremen city law or show only minor deviations. In the case of 69, an origin from Bremen law cannot be proven, but even of these five are very similar to the provisions of Bremen.

Wildeshausen (1270–1529)

The area of today's Wildeshausen was owned by descendants of Widukind in the 9th century . One of these descendants, Count Waltbert, built a church and in 851 the remains of Saint Alexander of Rome were transferred to this church. Waltbert then founded a house monastery on the basis of this church in 872 and also donated the "villa" Wildeshausen to the monastery. In 980 Otto II transferred the monastery with the settlement to the Diocese of Osnabrück . The whereabouts of Wildeshausens is unclear. Adam von Bremen reports, however, that Archbishop Adalbert von Bremen tried to unilaterally expand his sphere of power by intending to found a suffragan diocese in Wildeshausen . After clashes between the House of Guelph and the diocese of Bremen led in 1219 to an agreement between Archbishop Gerhard II. And the Count Palatine Henry the elderly , among others was in the agreement provost assigned Wildeshausen to the bishopric of Bremen. In 1228 the house of the Askanians renounced its claims to Wildeshausen. Wildeshausen, however, still belonged to the Diocese of Osnabrück under canon law, the Bailiwick was in the hands of the Counts of Wildeshausen-Oldenburg. When the count's house died out in 1270, Archbishop Hildebold finally moved the Wildeshausen provost to the Archdiocese of Bremen. However, the rulership over the city of Wildeshausen was unclear. In this context, the archbishop granted Wildeshausen town charter under Bremen law in 1270. The document from 1270 does not contain any references to a planned move to Bremen. No corresponding applications have been received either. It is assumed, however, that legal inquiries were made orally and that existing documents in connection with the events of 1529 may have been destroyed.

The only surviving city book of the city of Wildeshausen from the 14th century contains 30 statutes that have little reference to Bremen city law. As far as there are similarities (e.g. the tripartite division of the council), these can also be traced back to the related urban living conditions, similar traditional law or the zeitgeist. However, the provisions of the Wildeshauser Stadtbuch do not contradict the provisions of the Bremen city law. However, at the beginning of a regulation that concerns questions of compensation and guilt in the event of a fire , the commonality with Bremen law is expressly emphasized.

Wildeshausen was often pledged by the Diocese of Bremen , it enjoyed a very high degree of independence through these pledges and the associated uncertainties about the power relations as well as a certain peripheral location to various power factors. In 1429 it was pledged to the diocese of Münster , which Wildeshausen had in turn pledged to its own vassal, the bailiff of Harpstedt Wilhelm von dem Busche. In 1509 the Diocese of Bremen tried to pull Wildeshausen back to itself, but the Wildeshausener refused Archbishop Johann III. from Bremen, however, the homage. At the same time, against the background of the Reformation, a movement hostile to priests and the Church began in Wildeshausen . Finally, the Wildeshausener subjects of the diocese of Münster attacked, and a priest of the diocese was killed. The Reichsacht was then imposed on Wildeshausen . The bishop of Munster was authorized to carry out the imperial ban. As part of this, all sovereign rights were withdrawn from the city of Wildeshausen, the previous city was (temporarily) downgraded to a patch and all previous rights were at least temporarily transferred to the Gogericht on the Desum (near Emstek ). The main trip to Bremen to obtain legal advice was expressly prohibited. This ended Wideshausen's membership of the Bremen municipal legal family.

Oldenburg (1345)

Oldenburg was built around the castle of the Counts of Oldenburg, which probably already existed in 1108 . The place was then the seat of the counts through the Middle Ages until the early modern period and thus took on the typical character of a residential town . A market in Oldenburg can only be proven in 1243, which was then sponsored by the counts in order to benefit from trade between Bremen and Friesland or Westphalia . First of all, an influence of the Westphalian city law becomes noticeable. For example, in a document of around 1299 lay judges are mentioned who are atypical for the Lower Saxony city rights, but appear in the Westphalian city rights. In later documents, however, the term “consules” is used; Judges are no longer mentioned. A gradual takeover of Bremen law can be ascertained, for example Bremen town charter was written off for the first Oldenburg city book, Bremen was probably also the model for the Oldenburg council constitution of 1300. In 1345 the Count of Oldenburg finally granted a privilege in which he gave Oldenburg confers urban freedoms and places the city under Bremen law. However, the certificate names a large number of reservations. The count reserves the right to have a court held by a bailiff and other regalia . The city was forbidden to form independent alliances with third parties. At the same time, the count informed the councils of Osnabrück and Dortmund that he had made Oldenburg a free city, placed it under Bremen law and allowed it to hold seven masses . This makes it clear that the main aim was to promote trade by dismantling trade restrictions and creating legal certainty for merchants. In 1429 and 1463, Bremen's town charter was confirmed, albeit together with the restrictions.

In 1433, the Count of Oldenburg emphasized in disputes between the Oldenburg council that he had under no circumstances granted all the rights of Bremen's city charter, in particular he expressly reserved the embarrassing (i.e. criminal ) jurisdiction. Afterwards legal advice could be obtained in Bremen in civil law disputes; Criminal cases did not belong before a city court or the council, but only before the count's courts. How the court proceedings in civil matters and matters of voluntary jurisdiction went in detail can only be speculated. Certainly there was a legal move from the Oldenburg council to the Bremen council as Oberhof. Legal inquiries from Oldenburg lower courts directly to the council in Bremen have not yet been proven. The legal dispute between the Count of Oldenburg and Alf Langwarden, a deposed mayor of Oldenburg, is a surviving special case. At Langwardens request, the Bremen council was authorized by the emperor to make legal decisions. What is disputed is how the activities of the Bremen Council should be assessed in this process, which ultimately ends in a comparison . Haase interpreted the behavior of the council as an attempt to steal the role of a higher court against the count; Eckhardt interprets the process merely as the appointment of the Bremen Council as the emperor's deputy in individual cases. In 1575, the Counts of Oldenburg once again made it clear that they had jurisdiction and, in particular, that the privileges of the city of Bremen would not apply to Oldenburg; only material Bremen private law would apply. To justify this position, the count referred, among other things, to the fact that Bremen, with its city fortifications, had to pay for its own protection, since the archbishop did nothing, but he ensured the defense of Oldenburg.

The importance of the Bremen city charter for Oldenburg meant that the first printing of the Bremen city charter took place on behalf of the royal Danish judicial and Oldenburg government councilor Johann Christoph von Oetken. The print appeared in 1722 under the title " Corpus Constitutionum Oldenburgicarum ".

Delmenhorst (1371)

Like Oldenburg, Delmenhorst was a residential city. This is where the younger line of the Oldenburg family resided, the Counts of Oldenburg-Delmenhorst. The residence was a castle that already existed in 1259. A village near the castle was mentioned around 1300. In 1311 the counts undertook to maintain the road from Delmenhorst to Huchting . In 1371 the place had grown so far that the Counts of Delmenhorst granted city rights according to Bremen law; but with similar restrictions as the relatives in Oldenburg. Despite the city charter, Delmenhorst did not flourish. This is mainly due to the fact that it is too close to the large trading center Bremen, which left Delmenhorst little economic space for its own development until the 19th century. It was not until 1577 that Delmenhorst had jurisdiction at all, which was only transferred to the city in 1699.

Harpstedt (1396)

A document from Count Otto von Hoya and Bruchhausen dated March 5, 1396 has come down to us for Harpstedt . In the deed the intention of the count is announced to justify a soft image and to subordinate this to Bremen law. Haase assumes that this was an aborted attempt to found a city and that, contrary to the representation of older authors, there is no further indication of the expansion of Bremen's city law. As a result, this right cannot be assumed to apply in Harpstedt. Eckhardt, on the other hand, proves that there is a copy of a document handed down by the mayor and the council of Wigbolds und Bleks zu Harpstedt according to Bremerrechte from 1607, which was also certified with our wychbolde according to Bremerrechte and Harpstedeschen seal. Furthermore, the existence of this soft image can be proven. Harpstedt also referred to the document in the 19th century.

Legal inquiries from Harpstedt cannot be proven, however, an Oberhof relationship with Bremen cannot be ruled out.

Other places

For Neustadt am Rübenberge there is an unspecified letter to the Council of Bremen in which legal advice is requested in three cases. In addition, there is a letter from around the same time, which contains a request for help from the Neustädter Council with regard to a Bremen citizen to the council in Bremen. Haase believes that from this he can derive the assumption that Bremen city law could have applied in Neustadt am Rübenberge and probably also in Nienburg . However, there is no certificate of the award of Bremen city charter. Otherwise, an inquiry and request for legal information does not necessarily require the application of Bremen city law. Further evidence for a corresponding legal relationship is not known.

The documents on Bremen's city law

City law books for the city law from 1303/1308

For the city law book of 1303/1308, at least six copies and one original version can be documented directly or indirectly. However, only four of these books have survived in the Bremen archives.

First of all, the original city law book should be mentioned. This legal book contains 108 parchment sheets in the format of 33.7 by 22.7 cm. Brown ink was used for this certificate. For the register, counts, headings, and award pieces, red was used; for decorative initials , red and blue ink was used alternately. There are a few initials in gold leaf . The book is two lines. This city book is characterized by a relatively wide space that the three verifiable scribes of the original version left for additions and amendments and a large number of such additions up to 1424, which largely overgrown the original text. In the course of time, these additions and changes filled almost all the space provided. The original text was designed in a Gothic book minuscule from the 14th century. The later additions, written by around three dozen different hands, were written less in books and more generally in chancellery and certificate forms typical of the time. Overall, the book shows strong signs of use and was rebound in a pigskin renaissance binding after a restoration in the first half of the 16th century .

The oldest surviving copy of Bremen's city law from 1303/1308 was probably written for private use by one of the councilors, was then found in the cathedral library and then reached the archives of the city of Bremen under unknown circumstances. The transcription comprises 88 sheets, is designed in brown ink and for distinction texts, headings and counts in red and for decorative initials in red and blue ink. The manuscript can be dated by the last recorded judgment of the council to around the year 1332. The copy is in Middle Low German, only the date and the initial formula are in Latin. At 20.5 by 15.5 cm, this copy is very small.

The second oldest surviving copy comprises 93 sheets of parchment with a height of 34 cm and a width of 23.5 cm. For a long time, this copy was thought to be the original, only Oelrich proved by comparison of the fonts that it was a copy. The book can be dated in the main hand to a time around 1335, the additions in this copy to about 1420. This copy is mainly written in Middle Low German, only the calendar, the initial formula, the dating and sacred texts have been Latinized . This copy, too, has two lines and was originally written in the form of the Gothic book minuscule. The copy was uniformly designed by one hand. This copy is of particular importance due to the three larger supplements that represent less novellas than extensions or breaches of the original city law. First of all, the sacred texts (excerpts from Genesis , the Gospel of John and the stories of saints) precede the city law. Legally noteworthy is the Hamburg shipping and maritime law appended on four pages, which considerably supplemented the shipping and maritime law, which was only incompletely developed in the original Bremen city law. A name register and a calendar were also attached.

The third surviving copy can be dated to the last quarter of the 14th century and is based on a non-surviving copy that was made before 1330. This transcript is the least carefully drafted and contains numerous errors and omissions. The small format of 20.5 by 15 cm indicates a private client. No additions were made, but notes on free sheets of the manuscript indicate that this copy was still used in the 16th century. In modern times, this copy was combined with a copy of the town charter from 1433 from the 16th century and the first printed proclamation, the “Wedding, Kindelbier and Burial Regulations” from 1587.

Prints of the city law

Due to the large number of copies of the glosses that went back to Krefting , Wichmann and Almers, and divergent copies of the city law in circulation, it was hardly possible to get a binding legal text in the course of the 17th century. Until 1828, the councilors were sworn in not on the authentic original, but on a copy. The lack of agreement on a binding legal text and its commentary - Kreftings, Almers and Wichmanns glosses came closest to such recognition as commentary - meant that private printing came about late. From the official side, it was initially omitted entirely.

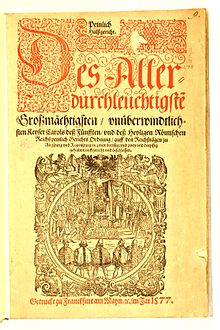

The first printing of the Bremen city charter took place on behalf of the royal Danish judiciary and Oldenburg government councilor Johann Christoph von Oetkene. The print appeared in 1722 under the title " Corpus Constitutionum Oldenburgicarum ". However, this edition was not based on the town charter of 1303 (which was formally decisive in Oldenburg ) and not the version from 1433, but rather the version of the early 17th century revised by Krefting, including Krefting's glosses. However, this connection between the legal text and comments meant that the work was initially not accepted in practice, as the distinction between law and commentary was not recognizable at the time. This was followed by an impression in the appendix of the second volume published in 1748 by Friedrich Esaias Pufendorf's Observationes juris universi . He had used several copies for this and also used the Verden statutes and the Hamburg and Stader city law as comparison material. Nevertheless, the print is still not considered to be true to the original. The impression of the Knowledgeable Scroll should also incorrectly come from 1539. The lack of accuracy was criticized by contemporaries. The print version contained in 1765 in Christian Nettelblatts Greinir ... or gleanings of old, new, foreign and own ... treatises from 1765 was considered unsuitable because it had numerous gaps and inadequacies.

The first print, which was accepted as useful by legal practice, came from the lawyer and syndic of the Bremen merchants Gerhard Oelrichs. This first published a glossary on Bremen city law in 1767 ("Glossarium ad Statuta Bremensium", published in Frankfurt am Main ). Oelrichs then turned to the Senate to inspect the original city law and other original documents on Bremen city law. In 1771 his “Complete Collection of Old and New Law Books of the Imperial and the Heil. Roman Empire free city of Bremen from original manuscripts ”. Oelrich had financed the printing himself by taking out mortgages and issuing festivals . The price for one issue was 4 Reichstalers . The book contained 934 pages: The city law versions from 1303, 1428, 1433, the Kundigen roles from 1450 and 1498, the Oldenburg city law from 1345, if there were deviations from Bremen law, and some land and dike rights in the surrounding area. The sale of the book was an economic failure, but his work was already recognized by contemporaries. The Council gave Bremen Oelrich for his work probably one in 1997 by one of his descendants at Sotheby's given up for auction silver centerpiece . Oelrich's edition replaced the old copies and remained the authoritative work in legal practice in Bremen until well into the 19th century, despite existing reading and printing errors.

History of the documents in the 20th century

The town charter is stored in the Bremen State Archives . In the course of the Second World War , the city charter to protect against bombing was outsourced. As a result, they fell into the hands of the Red Army and were brought to the Soviet Union as looted art . Most of the documents returned from Moscow in 1991 and from Armenia in 2001 . In 2014 the well-known role , which had previously been lost, appeared at a dealer in the United States and was returned to the State Archives. It was probably taken as a souvenir by a US soldier.

literature

- Konrad Elmshäuser , Adolf E. Hofmeister (ed.): 700 years of Bremen law. (Publications of the Bremen State Archives, Vol. 66). Self-published by the Bremen State Archives, 2003, ISBN 3-925729-34-8 , ISSN 0172-7877

- Carl Haase : Investigations into the history of the Bremen city law in the Middle Ages. (Publications from the State Archives of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, Issue 21). Carl-Schünemann-Verlag, 1953.

- Ferdinand Donandt: Attempting a History of the Bremen City Law. 1st part: constitutional history. Bremen 1830.

- Ferdinand Donandt: Attempting a History of the Bremen City Law. Part 2: Legal History. Bremen 1830.

See also

- State constitution of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen

- History of the city of Bremen

- Bremen Council (City Council)

- Bremen citizenship , deputations (Bremen)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Certificate No. 27 in: Paul Kehr (Ed.): Diplomata 10: The documents of Arnolf (Arnolfi Diplomata). Berlin 1940, pp. 39–40 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Certificate No. 307 in: Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 12: The documents Konrad I., Heinrich I. and Otto I. (Conradi I., Heinrici I. et Ottonis I. Diplomata). Hanover 1879, pp. 422-423 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ↑ Certificate No. 40 in: Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893, pp. 439–440 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- ^ A b Dieter Hägermann: Law and Constitution in Medieval Bremen. In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 17-26.

- ^ Ulrich Eisenhardt: German legal history. 3. Edition. CH Beck Munich 1999, ISBN 3-406-45308-2 , paragraph 73 ff.

- ↑ Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand: The written law in the medieval city. In: Bremisches Jahrbuch . Vol. 83 (2004), p. 18 (22)

- ↑ Timo Holzborn, The History of Legal Publication - in particular from the beginnings of book printing around 1450 to the introduction of legal gazettes in the 19th century ( Memento from April 19, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (Diss. 2003; PDF; 5.0 MB) Legal Series Tenea Vol. 39, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-86504-005-5 , p. 9.

- ↑ Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand: The written law in the medieval city. In: Bremisches Jahrbuch. Vol. 83 (2004), p. 18.

- ↑ Evamaria Engel: The German city in the Middle Ages. Albatros Verlag, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96135-1 , p. 82.

- ↑ a b c Walter Barkhausen: On the development of Bremen law up to the latest version of the city law from 1433. Bremisches Jahrbuch, vol. 83 (2004), p. 39 (40)

- ^ Herbert Schwarzwälder : Bremen around 1300 and its city rights from 1303. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 29 ff.

- ^ Herbert Schwarzwälder: Bremen around 1300 and its city rights from 1303. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 29 (p. 40 ff).

- ^ Herbert Schwarzwälder: Bremen around 1300 and its city rights from 1303. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 29 (p. 42, 43 ff).

- ^ Stephan Laux, review of 700 years of Bremen law

- ↑ Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand: The written law in the medieval city. In: Bremisches Jahrbuch . Volume 83, Bremen 2004, p. 18 (29).

- ↑ Konrad Elmshäuser: The manuscripts of the Bremen city rights codifications 1303, 1428, 1433. In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 46-73.

- ↑ Konrad Elmshäuser: The manuscripts of the Bremen city law codifications of 1303, 1428 and 1433. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 62 f.

- ^ Herbert Schwarzwälder: Bremer Geschichte , Döll-Verlag, Bremen 1993, ISBN 3-88808-202-1 , p. 40 ff.

- ↑ Carl Haase: Investigations into the history of Bremen city law in the Middle Ages. Pp. 65, 66.

- ↑ suehnekreuz.de

- ^ Adolf E. Hofmeister: From the knowledgeable role to the collection of Bremen law. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 267 ff.

- ↑ Timo Holzborn: The history of legal publication - especially from the beginnings of printing in 1450 to the introduction of legal gazettes in the 19th century (PDF; 5.0 MB), Diss. 2003, Juristic Series Tenea, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-86504-005- 5 , especially p. 49.

- ^ Adolf E. Hofmeister: From the knowledgeable role to the collection of Bremen law. In: Konrad Elmshäuser / Adolf E. Hofmeister (ed.): 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 267-278.

- ^ Herbert Black Forest: History of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen . Volume I, p. 153. Edition Temmen, Bremen 1995.

- ↑ a b Walter Barkhausen: The draft of a Verbeterden Stadtbook and the glosses on city law from 1433. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 200 ff.

- ↑ Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of February 25, 1803 .

- ↑ Bremen's history, A Foray through the Centuries - Nineteenth Century (1789–1914) ( Memento of the original from September 10, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Andreas Schulz, The replacement of the medieval city law in the 19th century. In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 250-259.

- ^ Andreas Schulz, The replacement of the medieval city law in the 19th century. In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 257, 258.

- ^ Andreas Schulz, The replacement of the medieval city law in the 19th century. In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 259-265.

- ^ Alfred Rinken, "Bremer Recht" - Continuities and discontinuities. In: Bremisches Jahrbuch. Vol. 83 (2004), p. 33 (34 ff.).

- ^ Ulrich Eisenhart: German legal history. 3. Edition. Munich 1999, no. 585, 588.

- ^ Ulrich Eisenhart: German legal history. 3. Edition. Munich 1999, no. 569

- ^ Richter, Walter, 100 Years of the Court of Justice in Bremen , The Senator for Justice and the Constitution of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (ed.), WMIT-Druck-u.-Verlag-GmbH, 1998, ISBN 3-929542-11-0 .

- ^ Ulrich Eisenhart: German legal history. 3. Edition. Munich 1999, no. 574-582b.

- ↑ Cf. in detail on this: Ute Siewerts: The language of Bremen city law from 1303. In: 700 years of Bremen law. P. 97 ff.

- ^ Karl August Eckhardt: The medieval legal sources of the city of Bremen , writings of the Bremen scientific society, Bremen 1931, p. 14-25. Online at the SuUB Bremen: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:46:1-163

- ↑ Konrad Elmshäuser: The manuscripts of the Bremen city law codifications of 1303, 1428 and 1433 In: 700 years of Bremen law. Pp. 48, 60.