Rat catcher from Hameln

The Pied Piper of Hameln is one of the most famous German legends . It has been translated into more than 30 languages. It is estimated that more than a billion people know them. Even in distant countries it is often part of the school curriculum; it is particularly popular in Japan and the USA .

City tour in Hameln through the Pied Piper of Hamelin

|

Lithograph from 1902: "Greetings from Hameln"

|

Sage (after the Brothers Grimm)

According to legend, a strange man appeared in Hamelin in 1284 . He wore an outer garment made of multicolored, brightly colored cloth and pretended to be a pied piper by promising to rid the city of all mice and rats for a certain amount of money . At that time Hamelin was suffering from a great plague of rats, which the city itself could not master, which is why it welcomed the foreigner's offer.

The citizens promised him his wages, and the pied piper took out his pipe and whistled a melody. Then the rats and mice came crawling out of all the houses and gathered around him. When he thought there was none left, he went out of the city into the Weser ; the whole bunch followed him, fell into the water and drowned. But when the citizens saw themselves freed from their plague, they repented of the promise and they refused the wages to the man, so that he went away angry and bitter.

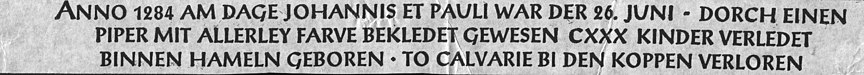

On June 26th, however, he returned in the form of a hunter, with a terrible face, a red, strange hat and, while everyone was gathered in the church, let his flute sound again in the streets. Immediately this time it was not rats and mice but children, boys and girls from the fourth year on, running in large numbers. Always playing, he led them out to the Easter gate into a mountain, where he disappeared with them. Only two children returned because they were late; but one of them was blind so that it couldn't show the place, the other mute so that it couldn't tell. A boy had turned back to fetch his upper garment and thus escaped the misfortune. Some said the children were taken to a cave and come out in Transylvania . A total of 130 children had disappeared. You never saw her again.

(Abridged and linguistically somewhat modernized from: Brothers Grimm : Deutsche Sagen , No. 245, The Children of Hameln)

Historical background

The origin and the possible historical core of the Pied Piper legend cannot be determined with absolute certainty. However, it can be considered certain that these are two originally independent sagas that were only connected to one another in a secondary manner: The original children's extract saga was probably only linked to a rat expulsion saga at the end of the 16th century . The probability that both legends (parts) have a historical core is different. In the medieval council books of the city of Hameln, for example, it is nowhere to be found that the city of Hameln promised or paid a pied piper a wage. Scientific studies on the question of whether rats react to the sound of a flute also suggest that the part of the saga “driving rats away” is legend. This could not be confirmed with the usual frequency of the flutes used at the time.

The situation is different with the legends “Children's extract”, whereby among the many interpretations, the interpretation of the eastern colonization emanating from Lower Germany can claim the greatest probability: the “children of Hameln” are likely to have been young citizens of Hamelin, those of noble territorial lords or locators were recruited to settle in the east.

The emigration region of the Hamelin children - previously one had thought of Transylvania , Moravia , Pomerania or the Teutonic Order - was specified by the onomastics professor Jürgen Udolph in 1997: emigrants had the habit of naming newly founded places in their target areas after places from their old homeland. In the course of the medieval colonization of the east, place names from the Hamelin region can be localized primarily in today's state of Brandenburg , especially in the Prignitz and Uckermark regions . For example, the name of the Hamelspringe near Hameln (“place where the Hamel springs”) can be found as Hammelspring in the Uckermark district , where no local reason can be identified for this name. Likewise, the name of the county of Spiegelberg in the Weserbergland is likely to have led to the naming of the place Groß Spiegelberg near Pasewalk .

In contrast, contrary to earlier assumptions, Transylvania and Moravia are largely ruled out as target areas for emigrants from Hamelin, because there are no place names that can be proven to come from the Weser region. The older literature refers mainly to a place name Hamlíkov in Moravia, but this, as Udolph was able to show, is not derived from the city of Hameln. Regardless of the place names, the Troppauer city archivist Wolfgang Wann and the Hamelin local history researcher Heinrich Spanuth found out that the same family names were recorded in Olomouc in northern Moravia at that time as in the Hamelin civil register (for example Hamel , Hämler , Hamlinus , Leist , Fargel , Ketteler and others), which may not be a coincidence. Another indication that speaks for this thesis is the meaning of the place name Olomouc, in Czech Olomouc , which means something like "bald mountain".

Overall, however, the names of the regions of Prignitz and Uckermark as well as the time when the children moved out - the 13th century was the heyday of German colonization in the east - make the emigration theory very likely: The pied piper may in fact have been an advertiser for German settlers in the east, and the legend (Pied Piper legend) only wants to lyrically rewrite the loss of almost an entire generation that has left their homeland because of a lack of prospects or to interpret it as an act of revenge by someone who has been cheated. Perhaps they didn't want to give themselves up to the nakedness that an entire generation emigrated because they saw no future in the guilds of that time and preferred to move east with the prospect of building their own household or business there.

Several historians assume that the legend of the Pied Piper of Hameln is said to have been inspired by the Children's Crusade . Against this view, however, speaks inter alia that the children's crusade took place in 1212; However, the year of emigration of the Hamelin children, which has been credibly handed down, is 1284. The same argument can also be made against the interpretation of the Pied Piper legend as a plague narrative, since the plague epidemics in medieval Europe did not appear until 1347.

Another theory, which is not so strongly supported, is that the children of Hamelin may have been subjected to a pagan sect leader who led them to a religious rite in the woods near Coppenbrügge , where they performed pagan dances. There was a landslide or sinkhole , which caused most of them to perish. A large hollow can still be found there today, which could have been created by such an event.

Dissemination and popularization

The oldest description of the children's extract from Hameln, written in Latin prose, can be found in an addendum to the Lüneburg manuscript of the Catena aurea of the Minden Dominican monk Heinrich von Herford († 1370) from around 1430/50 . The first literary mention of the legend can be found in 1556 by Jobus Fincelius . It is also portrayed in the 16th century by Kasper Goltwurm , Froben Christoph von Zimmer , Johann Weyer , Andreas Hondorff , Lucas Lossius , Andreas Werner , Heinrich Bünting , Hannibal Nullejus and Georg Rollenhagen . The mayor of Hameln, Friedrich Poppendieck, donated a glass window for the market church in 1572 with a depiction of the whistler, which has been preserved in a drawing from 1592.

The legend was picked up and made known in the 17th century by the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher . He drove to Hameln especially to find out about history. “Kircher played a large part in popularizing it. His description of the 'miracle' was often quoted, reissued, retold and transcribed. ”(Gesa Snell, director of the Museum Hameln)“ Kircher opened the discussion about Hameln and thus created the basis for later popularization. ”(Der Kircher researcher Christoph Daxelmüller) Kircher's musical work 'Musurgia universalis' from 1650 is also about the flute tones of the pied piper and its magical effect.

The geographer and polymath Johann Gottfried Gregorii spread the legend in his popular geography books in German-speaking countries at the beginning of the 18th century. Its legends were passed down by Achim von Arnim , whose friend Jacob Grimm and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe were still very well known a century later when they wrote down their texts on the Pied Piper legend .

Intangible cultural heritage

In November 2013, the city of Hameln applied via the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture to include the customs around the Pied Piper in the nationwide register of intangible cultural heritage . The inclusion within the meaning of the Convention for the Preservation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of UNESCO took place in December 2014. The German UNESCO Commission justified the selection with the fact that the original history is treated in constantly new variations until today. The range of cultural reflections on the subject, including in media such as comics , poetry and music, keep the history of the Pied Piper of Hameln alive.

Similar sagas

There are also pied piper or rat banner legends related to rat plagues from other German regions and European countries, for example from Drancy-les-Nouës near Paris in France, as well as frog plagues (see Flößer von Thorn ). Most of the time, however, these stories are not connected with the fact that the Pied Piper subsequently led other local residents away in revenge; The two stories mentioned below make an exception.

Pied Piper from Korneuburg

In Korneuburg in Lower Austria, a pied piper is said to have appeared in 1646. After drowning the rats in an arm of the Danube, he was accused of being in league with the devil and refused to pay him. This is where the oldest traditions end. Only later, based on the Hamelin story, was the legend added that the Pied Piper then took children away from Korneuburg as punishment and sold them on the slave market in Constantinople.

The Katzenveit from Tripstrille

The legendary figure Katzenveit is said to have been up to mischief in the region around the Saxon city of Zwickau . A traditional story shows great parallels to the Pied Piper of Hamelin, although the cats, rather than the children, were led out of the city as punishment for the citizens unwilling to pay.

Allusions in pop culture

Due to the popularity described above, there are always reminiscences of the legend of the Pied Piper of Hameln in pop culture, such as in films, TV series, pieces of music or video games:

- In 1996 the Pied Piper from Hameln was parodied in the music video "Hand In Hand" of the dance project Dune .

- In the 2010 remake of A Nightmare on Elm Street , a scene set in the library in Springwood alludes to a similarity between the Pied Piper and Freddy Krueger . In a book, two teenagers come across an illustration of the Pied Piper, who is wearing a shirt with the same red and green stripes as Freddy's sweater. This is supposed to indicate that Freddy is a modern (and also more brutal) variant of him, as he too "takes the children away" from the residents of Springwood in revenge.

- In Sailor Moon - journey to the land of dreams flutes elves in the night, the children wake up, follow them and are abducted by a flying ship.

- The Sweet Beyond is a two-time Oscar-nominated drama from Canadian director Atom Egoyan from 1997. It is based on the novel by Russell Banks . The drama varies the basic motif of the legend of the Pied Piper of Hameln: the children of a place die in the wake of a leading figure, in this case a bus driver.

- The Pied Piper also appears in the film Shrek Forever After .

- In the anime Mondaiji-tachi ga Isekai Kara Kuru Sō Desu yo? the legend about the pied piper plays an important role.

- The German television thriller Die Toten von Hameln from 2014 deals with the mysterious disappearance of four girls and a supervisor in the Rothesteinhöhle of the Ith , to which, according to the film, the Pied Piper is said to have once led the children of Hamelin.

- In the American series Once Upon a Time - Once Upon a Time ... the Pied Piper is actually the antagonist Peter Pan , who kidnaps the male children of Hameln and turns them into his "lost boys". Among them is Rumpelstiltskin's son "Baelfire", who is saved by his father.

- In the US mystery television series Sleepy Hollow , episode 4 of the second season, Go Where I Send Thee… , reference is made to the Pied Piper of Hameln. The “Pied Piper of Sleepy Hollow” was cheated of his payment and therefore kidnaps a child from the family in question when it turns ten.

- In the US television series Silicon Valley , the start-up company founded by Richard is called "Pied Piper".

- In Lie to Me , an American television series, the 19th episode of the second season is named after the Pied Piper (in the original: "Pied Piper"). As a result, a kidnapper and murderer of firstborn children is caught.

- In the 17th episode of the second season (The Trill candidate) of the series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine , the station is plagued by Cardassian mice. Chief O'Brien finds no way of containing the plague with the means at his disposal. He receives from Dr. Bashir a flute with the note "It worked in Hameln" as a gift.

- In the theme song of the album Kid A by the band Radiohead , the story of the Pied Piper is metaphorically borrowed from Hameln: " Rats and children follow me out of town; Rats and children follow me out of their homes; Come on, kids ".

- In the third chapter of the action adventure Heavy Rain , the protagonist Ethan Mars receives the so-called church letter from the Origami Killer , in which the legend of the Pied Piper of Hameln is alluded to:

“When the parents came home from going to church, all of the children were gone. They searched and called them, they cried and pleaded. But everything was in vain. The children were never seen again. "

Metaphorical use

The image of the pied piper as a fascinating seductive figure has had a diverse journalistic reception since the 19th century. Friedrich Nietzsche quoted this with reference to Dionysus. The composer Johann Strauss (son) was stylized in a satirical, literary and caricature way to a - musical - pied piper figure. The writer Richard Skowronnek (1862-1932) in turn saw Karl May as the "great pied piper". The image of the pied piper was polemically aggravated in publications of the 20th century. In Nazi jargon, the US jazz musician Benny Goodman became the "Pied Piper of New York", on the other hand, the communist writer Erich Weinert sees the originator of this term himself as a "brown pied piper". And so the term Pied Piper is now being used colloquially to refer to members of very different politically extreme groups or parties. Even prominent individuals are still given the designation. B. as a critical swipe for the left Greek politician Alexis Tsipras as the "Pied Piper of Athens" with regard to his controversial European policy.

See also

- Pied Piper Well

- Pied Piper House

- Pied Piper Literature Prize

- The Pied Piper (film) , German silent film by Paul Wegener (1918)

- The Pied Piper (Cerha) , opera by Friedrich Cerha

- The Pied Piper (Hiller) , opera by Wilfried Hiller

- Der Rattenfänger (album) , album and song by Hannes Wader (1974)

- The Pied Piper (Zuckmayer) , play by Carl Zuckmayer (1974)

- Wilhelm Raabe published his variant of the legend in 1863: " The Hämelschen children ".

- Karl Leineweber

literature

Motifs of the Pied Piper legend in: Clemens Brentano: The fairy tale of the Rhine and the Müller wheel run. Edited by Guido Görres 1846.

- Achim von Arnim : The Pied Piper of Hamelin. My very first story book. Karl Müller, Cologne 2004. ISBN 3-89893-910-3 .

- Marco Bergmann: Dark Piper. The previously unwritten life story of the "Pied Piper of Hameln". BoD, 2nd edition 2009, ISBN 978-3-8391-0104-9 .

- Hans Dobbertin: Collection of sources for the Hamelin Pied Piper legend. Schwartz, Göttingen 1970.

- Hans Dobbertin: Sources for the pied piper legend. Niemeyer, Hameln 1996 (extended new edition) ISBN 3-8271-9020-7 (Dobbertin connects the loss of the Hamelin children with Count Nicolaus von Spiegelberg's trek to Pomerania and the Baltic to Kopań near Darłowo , German Rügenwalde).

- Stanisław Dubiski: Ile prawdy w tej legendzie? ( How much truth does this legend contain? ). In: “Wiedza i Życie”, No. 6/1999.

- Radu Florescu : In Search of the Pied Piper. Athena Press 2005, ISBN 1-84401-339-1 .

- Norbert Humburg: The Pied Piper of Hamelin. The famous legendary figure in history and literature, painting and music, on stage and in film. Niemeyer, Hameln 2nd edition 1990, ISBN 3-87585-122-6 .

- Peter Stephan Jungk: The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Research and thoughts on a legendary myth. In: Neue Rundschau No. 105 (1994), H. 2, pp. 67-73.

- Ullrich Junker: Rübezahl - legend and reality. In: Our Harz. Journal for local history, customs and nature. Goslar, December 2000, pp. 225-228.

- Wolfgang Mieder : The Pied Piper of Hamelin. The legend in literature, media and caricature. Praesens, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-7069-0175-7 .

- Fanny Rostek-Lühmann: The child catcher of Hameln: Forbidden wishes and the function of the stranger . Berlin: Reimer 1995. ISBN 978-3496025672 .

- Heinrich Spanuth : The Pied Piper of Hamelin . Hameln: Niemeyer 1951.

- Izabela Taraszczuk: The Pied Piper Legend . On the interpretation and reception of history. In: Robert Buczek, Carsten Gansel , Paweł Zimniak (eds.) Germanistyka 3. Texts in contexts. Zielona Góra: Oficyna Wydawnicza Uniwersytetu Zielonogórskiego 2004 , pp. 261-273, ISBN 83-89712-29-6 .

- Jürgen Udolph : Did the Hamelin emigrants move to Moravia? The Pied Piper legend from a name-based point of view , in: Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte 69 (1997), pp. 125-183. ISSN 0078-0561 ( online )

Fiction

- Robert Browning (1812-1889): The Pied Piper of Hamelin . ( Digitized version of a German illustrated edition, around 1889)

- Julius Wolff (1834-1910): The Pied Piper of Hameln. (Adaptation of the novel from 1876)

- Viktor Dyk (1877–1931): Krysař (The Pied Piper) Novella, 1915.

- Anna Elisabeth Wiede (1928–2009): The rats of Hameln 1959 (play, first performance 1979 in Greifswald)

- Revelation 23 : Episode 23 - The Fountain of Youth , radio play, May 2008, ISBN 978-3-7857-3537-4 .

- Barbara Bartos-Höppner : The Pied Piper of Hameln (illustrations by Annegert Fuchshuber). Vienna: Annette Betz Verlag. ISBN 3-219-10282-4 . (first edition from 1984)

- Jacek Gutry: Zaczarowany flet (illustrations by Bogusław Orliński). Warszawa: Verlag MEA 2001. ISBN 83-88626-49-3 .

The motifs of the legend were also taken up in fantasy literature, including in:

- Gilbert Shelton: Fat Freddy's cat and the Pied Piper of Hameln. Red book. European Publishing House, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-88022-800-0 .

- Kai Meyer : Der Rattenzauber , Lübbe-Verlag, Bergisch Gladbach, 1995, ISBN 3-404-15265-4 .

- China Miéville : King Rat. Bastei Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2003, ISBN 3-404-24310-2 (Miéville's debut novel continues the legend from the view of the rats and relocates it to contemporary London.)

- Terry Pratchett : Maurice, the cat. A fairy tale from the Discworld . Goldmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-442-54570-6 .

- Wolfgang Hohlbein : Thirteen . Arena, 1995, ISBN 3-401-02897-9 .

- Bill Richardson : The Sound of Freedom cbt / C. Bertelsmann Jugendbuch Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-570-30141-9 .

- Britta Daniel-Tonn: Pied Piper of Hameln 2.0 , in: dies .: Grimm's New Fairy Tales 2.0 Once upon a time ... VERY DIFFERENT! 2012.

Comic adaptation of the Pied Piper material:

- André Houot: Hamelin. Editions Glénat 2012. (German translation: The Pied Piper of Hameln. From the French by Rossi Schreiber. Ehapa Comic Collection 2012).

music

- Viktor Nessler : The Pied Piper of Hameln , opera in 5 acts; Libretto: F. Hofmann after J. Wolff, premiere: March 19, 1879, Leipzig

- Peter Mennin : Cantata de Virtute “The Pied Piper of Hamelin” for speaker, tenor, baritone, children's choir, choir and orchestra; Text based on Robert Browning (1969)

- Hannes Wader : The Pied Piper , reinterpreted as a socialist parable (1974)

- Rainhard Fendrich : Pied Piper , from the album Wien bei Nacht (Polygram CD 824294-2, 1985)

- Ludwig Hirsch : Der Rattenkönig , from the album Tierisch (Amadeo CD 6125579-2008)

- ABBA : The Piper , from the album Super Trouper (Polar Music CD POLS 322-1980)

- Crispian St. Peters : The Pied Piper , USA 1966, original from Changin 'Times , USA 1965

- Megadeth : Symphony of Destruction , USA 1992, from the album Countdown to Extinction

- Günther Kretzschmar : The Pied Piper of Hameln , cantata for children

- In Extremo : Der Rattenfänger , Germany 2001, from the album Sünder ohne Zügel

- Feuerschwanz : Ra Ra Rattenschwanz from the album Met und Miezen . In this version, the pied piper lures the women of the villagers instead of the rats.

- BTS : Pied Piper , South Korea 2017, from the album Love Yourself: Her

- Saltatio Mortis : Pied Piper from the album Zirkus Zeitgeist (2015). Here the Pied Piper is shown as a heartbreaker.

Filmography

- 1907: The Pied Piper of Hamelin , directed by Percy Stow

- 1918: The Pied Piper of Hameln , directed by Paul Wegener

- 1933: The Pied Piper of Hameln , directed by Wilfred Jackson ; Cartoon

- 1957: The Pied Piper of Hamelin , director: Bretaigne Windust ; TV film with Van Johnson and Claude Rains

- 1972: The Pied Piper of Hameln , director: Jacques Demy ; Musical with Donovan and Diana Dors

- 1982: The Pied Piper of Hameln , director: Mark Hall ; Animation film

- 1984: The Pied Piper of Hamelin , director: Jiří Barta ; Animated film, Czechoslovakia

- 1997: The Sweet Beyond , Director: Atom Egoyan ; (The fictional film drama adopts the basic motif of the legend as a plot for its story)

- "Picture Book Germany" - Hameln. Script and direction v. Anne Worst. Production NDR . First broadcast June 13, 2004, 45 min. [1]

- Fairy tales & legends: The Pied Piper and the missing children. Documentation. Production ZDF . First broadcast October 16, 2005. 45 min. [2]

- The Pied Piper of Hameln - The true story from the series ›The true story‹, GB 2005, Discovery Channel

- Die Toten von Hameln , ZDF TV film in which the legend of the Pied Piper plays a role, 2014

Web links

- Legends of the Brothers Grimm

- Legendary tale by Wilhelm Herchenbach (PDF file; 307 kB)

- The Pied Piper of Hameln, series of postcards by Oskar Herrfurth

- Pied Piper Open Air Game Hamelin

Individual evidence

- ↑ Probably the world's best known version . City of Hameln. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- ↑ http://www.inschriften.net/hameln/inschrift/nr/di028-0107.html

- ↑ Source: PHOENIX Documentation 2009 "The Pied Piper and the Disappeared Children"

- ^ Richter, Rudolf: The Pied Piper of Hameln. In: Yearbook of Homeland. 1953. For the residents of the former home district of Bärn. St. Ottilien. P. 125.

- ↑ Hüsam, Gernot: The Koppen mountain of the Pied Piper legend of Hameln. Publisher: Museumsverein Coppenbrügge eV 1990.

- ^ Heinrich Spanuth : The Pied Piper of Hameln. About the creation and meaning of an old legend . (diss. phil.). CW Niemeyer, Hameln 1951.

- ↑ Jobus Fincelius: Full description and thorough listing of terrible miraculous signs and stories that passed from the Jar to MDXVII. except for a big jar MDLVI. happened after the Jarzal . Christian Rödiger, Jena 1556, unpaginated ( digitized version from the Bavarian State Library in Munich).

- ↑ Kasper Goltwurm: Wunderwerck and Wunderzeichen book . Zephelius, Frankfurt am Main 1557, unpaginated ( digitized version of the Bavarian State Library in Munich), ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Froben Christoph von Zimmer: Zimmerische Chronik (1565), ed. by Karl August Barack, Vol. III. JCB Mohr / Paul Siebeck, Tübingen 1881, pp. 198–200 ( digitized version of the Freiburg University Library).

- ^ Johann Weyer: De praestigiis Daemonum . Johannes Oporinus, Basel 1566, p. 84f ( digitized version of the Bavarian State Library in Munich), German edition Von Teufelsgespenst, magicians and Gifftbereytern, black artists, witches and monsters . Frankfurt am Main 1586, p. 43 ( Google Books ).

- ^ Andreas Hondorff: Promptuarium exemplorum . Leipzig 1568, p. 169 ( digital copy from the Bavarian State Library in Munich).

- ↑ Lucas Lossius: Hameliae in ripis jacet urbs celebrata Visurgis . In: ders. (Ed.): Fabulae Aesopi . Egenolph, Marburg 1571, No. 506, p. 309f ( Google Books ); see. Lucas Lossius: Ecclesiasticae historicae et dicta imprimis memorabilia, et item narrationes aliquot et epigrammata . Frankfurt 1571, p. 264f.

- ^ Andreas Werner: Chronica of the most highly praised Keyserfreyen Ertz and Primat Stiffts Madeburg . Paul Donat, Magdeburg 1584, p. 136 ( Google Books ).

- ^ Heinrich Bünting: Braunschweigische and Lüneburgische Chronica , Vol. II. Kirchner, Magdeburg 1585, Bl. 52 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Hannibal Nullejus: Epigrammata liber I . Konrad Grothe, Lemgo 1589.

- ^ Georg Rollehagen: Froschmeuseler . Andreas Gehn, Magdeburg 1595, unpaginated ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Poppendieck had an existing window renewed ("renouiren"); Heinrich Kornmann (1570–1627): Mons Veneris, Fraw Veneris Berg . Matthias Becker Witwe, Frankfurt am Main 1614, pp. 383–389, especially p. 384 ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Christine Wulf: Hameln, No. 76 †, St. Nicolai 1572 . In: The inscriptions of the city of Hameln . (The German inscriptions 28). Reichert, Wiesbaden 1989 ( digitized at www.inschriften.net).

- ↑ Eckart Roloff : Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680): The phantast from the Rhön makes a career in Rome. In: Eckart Roloff: Divine flashes of inspiration. Pastors and priests as inventors and discoverers. Weinheim: Wiley VCH 2012. pp. 129-130. ISBN 978-3-527-32578-8

- ↑ Sebastian Posse: The emotional character of a musical seduction by the Pied Piper of Hameln. A historical source analysis. Thesis.

- ^ MELISSANTES: Curieuse OROGRAPHIA Frankfurt, Leipzig [and Erfurt] 1715; Pp. 540–548, Bavarian State Library, Munich

- ↑ Press release of the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture: Customs around the Pied Piper legend and Low German theater are part of the intangible cultural heritage

- ↑ 27 forms of culture included in the German directory of intangible cultural heritage

- ↑ "Dt. UNESCO Commission - Dealing with the history of the Pied Piper of Hameln ” , accessed on January 16, 2015

- ↑ Humburg, Norbert: The Pied Piper of Hameln, p. 23 .

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtCTwPCyw1A

- ↑ Heavy Rain (2010), video game, Quantic Dream, Chapter 3 " Father and Son ", quotation from the protagonist Ethan Mars

- ↑ Dionysus and Ariadne in conversation: G. Schank, Subject Resolution and Polyphony in Nietzsche's Philosophy, Tijdschrift voor Filosofie, 53rd Jaarg., No. 3 (September 1991), pp. 489-519

- ↑ Josef Mauthner , VI. Rescue, in 48 sonnets

- ↑ Karl Klietsch , February 12, 1871, supplement to No. 7: “An der Wien on February 10, 1871”. [Strauss playing the violin, as a pied piper, who, the Geistinger at the top, that whole personalities of the " Indigo " follow]

- ^ Armer Henner, Stuttgart 1908, p. 36.

- ^ Illustrated observer 1944. Episode 28th image

- ↑ Call into the night. Poems from abroad 1933–1943. 1947, p. 333

- ↑ Phrase Index: a Pied Piper

- ↑ https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/alexis-tsipras-rattenfaenger-von-athen-floetet-in-berlin-1.1364083

- ^ ZDF press portal: Die Toten von Hameln