Graz Calvary

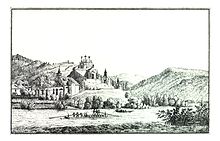

The Graz Kalvarienberg, built in the 17th century, is located on Austein near the Mur in what is now the Graz district of Lend . A crucifixion group with three crosses and several chapels stand on its rocky summit .

At the foot of the rock are the high baroque church built later, generally assigned to the Calvary , the Calvary Church of the Holy Cross with Holy Stairs and an Ecce Homo stage , the rectory and the elongated, narrow Calvary cemetery. The way of the cross to the Kalvarienberg with 14 stations is no longer preserved. The seven stations of the processional path from the city center to the later Calvary Church, which existed on the Austein before the construction of the complex, are still preserved.

When it was built, the Graz Calvary was the first replica of the Jerusalem crucifixion hill Golgota and its facilities within the Habsburg hereditary lands, reminiscent of the crucifixion of Christ . It was under the patronage of the Jesuit Order until the 18th century . From the beginning of its existence, the Graz Kalvarienberg has been the destination of pilgrimages and processions .

Geographical location

Settlement history

In Graz there are two striking geological elevations: the Grazer Schloßberg and the Austein , a green slate rock . While the city of Graz developed around the Schloßberg, the Austein remained of no urban significance until 1596, i.e. until Ferdinand Maschwanders dedication of the rock to the Jesuits. The relatively large distance to the city and the location of the Austeins in the middle of the Mur floodplains were the main reasons for little or hardly any settlement activity.

“ In the middle of this plain, narrowing like a valley in the north, about three-quarters of a mile wide and three and a half miles long, two heights emerge; the one very low close to the right, and the other much higher further downstream, first on the left bank of the Mur. The former is the Kalvarienberg, a colossal block of clay slate 15 Vienna high. Fathoms; [...] the latter of the 1434 par. (1474 Vienna.) Foot high Schloßberg. "

The Mur-Au next to the Austein was named " Maschwander-Au " after its owner at the time when the Calvary was built . From the 17th century onwards, there was a noticeable increase in settlement activity. Today the settlement density around the Kalvarienberg is very high due to the construction of numerous residential buildings. Due to the construction of the Mur floodplains in the Lend district of Graz , the Kalvarienberg can no longer (as in old views) be seen from all sides without restriction.

The Kalvarienberg in the Graz transport network

Coming from the south, the Grazer Kalvarienberg can be reached via Kalvarienbergstraße , which was part of the baroque processional path. Immediately before the entrance to the Kalvarienbergkirche it opens into Schippingerstraße , a connecting road to the west to Wiener Straße . The street is named after the farmer and innkeeper Anton Schippinger (1851–1914) who ran the “ Zum Wiesenwirt ” inn there . In addition to the Calvary road which ends at the same point Überfuhrgasse in the Schippinger road . A ferry with rafts and two head stations, which were connected to the other bank by means of a rope and thus ensured the crossing , was once located at this point as a bridge replacement .

The Austeingasse, named after Austein, is quite a distance away . It connects Grimmgasse in the south with the Kalvariengürtel in the north, which connects the two banks of the Mur with the "Kalvarienbrücke". The Kalvarienweg was formerly called Friedhofsweg . It runs along the east side of the Kalvarienberg cemetery and, together with the Kirchweg, flows into Schippingerstraße . The mash traveling lane , named after Ferdinand Masch walking, running in the vicinity of the Calvary cemetery. It is the connecting street between Augasse in the east and Eiswerkgasse in the west.

The Grazer Kalvarienberg can be reached via the bus stop 67 Schippingerstraße in the east and via the Kalvarienweg stop right next to the cemetery in the south of the facility.

History of the Grazer Kalvarienberg

Prehistory and foundation

A large part of the residents of the Styrian capital Graz, as in the rest of Styria, professed Protestantism up to around 1600 . From 1550 the re-Catholicization began through the Counter Reformation . This is reflected in the construction of a Via Dolorosa , the “painful street” or the “Path of Sorrows” (Way of the Cross), in Graz, which is an early form of the Calvary. It is reported that the Catholic Archduchess Maria of Bavaria and her husband and uncle, Archduke Karl II of Inner Austria , often went on pilgrimages to the church of Maria im Elend in Straßgang . The Way of the Cross with the 14 stations is no longer preserved today. This kind of piety exercise was unique in Austria up to then.

Bernhard Walter, later Bernhard Walter von Waltersweil, the chief stableman and chamberlain of Archduke Maximilian Ernst , had the first three crosses erected on the Austein in 1606, while the pious archduchess was still alive. Walter, who was raised to the nobility because of his services, donated the crosses with the permission of Ferdinand Maschwanders, the owner of Austein. Maschwander came from a Bavarian aristocratic family, his father was a valet of Emperor Ferdinand I. The family's coat of arms is attached to the entrance to the burial chapel. Maschwander came to Styria as a baron in 1598 and married Maximiliana von Herbersdorf in 1609. He bequeathed Austein Graz to the Jesuit order resident in the city so that “ the memory of Jesus Christ would be kept alive. “On August 31, 1619, the widow Maschwanders gave the rock with the three crosses to the Jesuit order. Bernhard Walter and Ferdinand Maschwander were the founders of the oldest calvary complex in what is now Austria, through the founding of the Grazer Kalvarienberg.

Passion cult, Jesuit theater and prohibition laws

Because of the distance between the Old City and Austein, which roughly corresponded to that of the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem , and the similarity of the rock with Golgotha , the "skull height" in Jerusalem, on which Jesus was crucified , the pilgrimage was very popular with the city's population. Founded by the Society of Jesus in 1620 in Graz citizens Brotherhood Mary cleaning took care of the Calvary. In 1640 it already had around 500 members. Until the Josephine reforms under Emperor Joseph II , it remained closely connected to the sacred complex.

The pastor of Graz and the prince-bishop of Seckau initially had reservations about this form of popular piety. That is why it stayed with the three simple crosses until the 1640s. It was not until 1653 that the Bishop of Seckau granted permission to build the first chapel , the Holy Sepulcher Chapel . It was built in 1654. 6000 pilgrims are said to have been present at the laying of the foundation stone, including Gabriel Maschwander, the son of Ferdinand Maschwander. He donated 1000 guilders for the construction. As a thank you, the Maschwander family's coat of arms was affixed to the chapel portal. Most of the complex on the Austein: chapels, grottoes, wayside shrines and statues were completed from this point on until around 1660. Today's Kalvarienbergkirche has been rebuilt from the former Ölberg chapel. Apart from this construction activity and the new construction of the Dismaskapelle on the site of the previous Rosalia Chapel, only the Johannes Nepomuk Chapel and the Petrus Grotto were added in the 19th century.

The number of pilgrims increased every year. The expansion was financed with those funds that were received through a general indulgence granted by Pope Alexander VII between 1657 and 1664 . Bishop Johann Markus von Seckau gave permission to read a Holy Mass at the Ölberg Chapel, which later became the Calvary Church . In 1667 more than 900 masses were celebrated. In 1660, Emperor Leopold I visited the Calvary with Archduke Leopold Wilhelm on a pilgrimage and donated a large sum for the expansion of the Mount of Olives Chapel.

A single book of miracles with a direct reference to the Graz Kalvarienberg has been preserved. It dates from 1673 and contains 43 reports of miracles from the time between 1655 and 1673. The healings were mostly associated with an "engagement to the mountain Calvari" , ie a vow to mount Calvary. The pledge was often accompanied by pilgrimages and donations. Votive offerings or pictures have not stood the test of time. The miracles that are described in the book of miracles affected almost every social class and profession from a large catchment area: noblemen, citizens, civil servants, craftsmen, innkeepers and workers hoped for a cure or the fulfillment of their vows. Miracle books were not uncommon at this time: in the parishes of Nestelbach near Graz and Graz-Straßgang , such documents, evidence of a time of great popular piety, have been preserved.

The establishment of the Kalvarienberg on Austein triggered a wave of new foundations of similar but smaller facilities in the Habsburg monarchy by the end of the 18th century. Incidents during flagellation and cross-carrying processions increased. Maria Theresa therefore issued prohibition laws in 1751 because of the public displays of explicit religious zeal. Her son, Emperor Joseph II, banned the carrying of figures and statues during processions, thereby ending the tradition of the baroque passion cult.

Parish establishment, decay and resurrection

The decline of the Calvary continued in the following decades. The facility began to deteriorate. At that time (since 1586) the area around the Austein belonged to the parish of St. Andrä . The idea came up to set up a parish of their own. This was approved by the bishop with the construction of a pastoral care center with a beneficiary in 1698. The first pastor was Matthias Bernhard Praunstein. He started working in the same year. Due to the lively construction activity around the Kalvarienberg in the 18th century, the call for a separate parish was again loud. Finally, on February 16, 1786, the pastoral care office was elevated to the rank of local curacy under canon law. A parish school was also set up. The first local curate was Father Lorenz Preissler, who until then had been a beneficiary. It was not until the rapid population increase during the industrial revolution that the Kalvarienberg local curatia was raised to the rank of parish in 1831. In 1946, the new Graz-Gösting parish with the Church of St. Anna replaced the Kalvarienberg parish .

In the 20th century, the complex fell into disrepair. On the one hand it was the weather that affected the chapels, stairs and figures, on the other hand the repeatedly observed and documented acts of vandalism. In the 1950s, the interior and exterior restoration of the Mariatroster Chapel and the exterior renovation of the Kalvarienbergkirche began. Small repairs were also carried out; but they could not prevent further deterioration. In 1999, it was finally decided to restore the Calvary complex, which was completed in 2003. The area with its buildings and works of art shines again in its old splendor.

Calvary Church

history

The Kalvarienbergkirche, the parish church of the Graz-Kalvarienberg parish and consecrated to the Holy Cross (precisely: Finding the Holy Cross ), developed in its current form from the Ölberg Chapel, which was expanded to a church in 1668 on an initiative of Count Johann Georg von Herberstein . Before the establishment of the Kalvarienberg there was a manor called “ Leuzenhof ” at this point . The special feature of the baroque church building is the porch as a sacred staircase and facade stage. The name of the master builder of the porch with the Holy Staircase and the Ecce Homo stage for corresponding performances, consecrated on September 14, 1723, has not been passed down. The plans probably came from Johann Georg Stengg . The church tower has a bell roof with a lantern. Two sandstone figures stand in front of the church: on the left the Savior carrying the cross and on the right the Mother of Sorrows .

Holy stairs

The Holy Stairs , the Scala Santa in the Lateran Palace in Rome, served as a model for the Holy Stairs of the Calvary Church in Graz . The Holy Staircase was created in connection with the Calvary as a replica of the Passion of Christ. The original once led to the palace of Pontius Pilate with 28 steps . The shape of the plant in Jerusalem was brought to Rome by St. Helena , mother of Emperor Constantine .

The Holy Staircase in Graz is attached to the south side of the nave of the church and is flanked on both sides by flights of stairs that lead into the church. They can also be used as an exit from the Holy Staircase, as they are connected to the main staircase. Originally, churchgoers had to kneel up the stairs, over which a barrel vault was built. At the bottom of the stairs there is a portal with a wrought iron skylight grille with the judge of the world, heraldic eagle and iron flowers. At the top of the stairs, directly in front of the church, there is a depiction of the scourged Christ in a niche with the words of the prophet Isaiah , " For the sake of our sins he was smashed "

Ecce Homo Stage

History and tradition

The stage with life-size figures, consisting of three levels, is located above the entrance to the Holy Staircase. The figures reproduce the scene from John's Gospel in which Pilate presents the captured and abused Jesus of Nazareth in a purple cloak to the Jewish people. Pilate's exclamation “ Ecce Homo ! "Comes from the Vulgate and means:" See what a man! "

The stage itself was, and this is considered to have been secured, at the instigation of the former owners of the Calvary, the Jesuits . The stage of the Viennese church “ To the nine angel choirs ” at the Viennese court served as a model for the Graz version . The Jesuit order has always used theatrics as an effective means of spreading the faith. Graz performances took place in today's seminary and in the old university in Bürgergasse. The Ordenstheater, also known as the Jesuit Theater, was dissolved in 1773, like the Graz branch of the Jesuit Order itself. This so-called “ theatrum sacrum ”, the “ sacred theater ”, experienced its heyday in the baroque era. The stage-like facade design of the Kalvarienbergkirche, on which the sufferings of Christ can be viewed in all their drama and emotion, is to be understood in this context.

Figures of the Ecce Homo stage

The focus of the figures on the facade is a sandstone statue depicting the " Christ on the Scourge Column ", which was created and signed in 1722 by the artist Johann Jacob Schoy . Next to the depiction of Christ on the middle level of the stage there are unsigned figures of accusers. Furthermore, two Pharisees can be seen with a large book in their hands. They are flanked by representatives of the common people on the two balconies that form the right and left levels of the Ecce Homo stage. The statues are made of stone and painted in color; only the hands of the Pharisees and the book were carved from wood and added afterwards. All representations are also attributed to the sculptor Schoy or his workshop.

Church interior

The interior of the Kalvarienbergkirche is a single-nave , three- bay hall with a mirror vault . The organ gallery is a yoke long. The choir gallery is located above the left side entrance. The Bandelwerk - and foliage stucco ceiling with depictions of angels comes from Domenico Bosco from the year 1704. In the cartridges are Emperor Constantine at the Milvian Bridge, the four evangelists and other scenes from the Christian iconography in fresco technique displayed. The stuccoing of the side chapels dates from 1668, the time the church was built; likewise the wrought iron lattice wing and the marble font.

A rock protrudes from the choir wall into the interior of the church. There is a plastic representation of the scene of the Mount of Olives with Jesus in the center. To the left of this is a group of figures with the sleeping apostles . On the right side, Jesus' capture is shown. All statues are part of the original church furnishings . Only the background painting was added in 1934 based on designs by Ludwig von Kurz-Thurn and Goldenstein and Franz Mikschowsky .

The late baroque stalls date from the 18th century, as does the cross altar. The pulpit was made in 1803 in the style of Jakob Peyers. On the sound cover are putti , holding the tablets of the law in their hands, and the three Christian virtues: faith, hope and love . Most of the interior furnishings are from the 19th century and are historical . The high altar of the Kalvarienbergkirche was created by the sculptors Peter Neuböck and Jakob Gschiel based on designs by August Ortwein .

Calvary complex

On the Calvary facility located next to the Crucifixion numerous chapels of the Jesuits , by rich citizens and by Emperor Leopold I. donated. The emperor paid a visit to the Graz Kalvarienberg on October 4, 1680.

All chapels are accessible and have a round arch stone portal with wrought iron lattice gates from the baroque era . Most were built in 1600, some in the 19th century. In the triangular gables of the chapels there are reliefs with depictions of the instruments of suffering ( Arma Christi = Latin "Christ's weapons against sin" ) of the Passion of Christ . The mostly baroque figures have been revised several times over the years. Between 1873 and 1895, the sculptor Jakob Gschiel worked on the Graz Kalvarienberg.

Crucifixion group

The crucifixion group ⊙ at the highest point of the Kalvarienberg was at this point from the beginning of the development of Austein up to today's Graz Kalvarienberg. The group consists of three crosses. In the middle is that of Jesus with the two criminals at his side who were crucified with him on Golgotha . Due to the exposed position, the crosses with the figures are heavily exposed to the weather. That's why they had to be renewed again and again over time. The cross that exists today has a gold-plated body, a copper drive. After a lightning strike in 1775, it was created by Karl Elssner . The cross was originally intended for the upper Mur Bridge (today Kepler Bridge ). On the back of the base is written: “ Fulmen deiecit, Congregatio reparavit ”, which translates as: “ Lightning struck it down, the Congregation raised it up ”.

Under the cross are three sandstone statues from the workshop of Jakob Schoy , on the right side Mary the Mother of God , on the left side Jesus' favorite disciple John and at his feet Mary Magdalene . The figures from the Baroque period have been revised several times. The wooden sculptures of the two criminals crucified with Jesus come from the workshop of the sculptor Jakob Gschiel. They were created in 1880. Despite all the changes, the overall composition still corresponds to that of the original from the time of creation. The order of the images in the gallery corresponds to the order of the statues and figures of the crucifixion group (from left to right):

Dismas , the good thief

Jesus Christ on the cross

Mother of God Mary

Gestas , the thief to the left of Christ

Chapels (overview)

| Surname | Time of origin | General with location | characters | Exterior view | inside view |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flagellation Chapel (1) | around 1660 | The small chapel is attached to the north-eastern rear of the church. It has a rectangular floor plan and a triangular gable. ⊙ | The artist Jakob Gschiel created the group of figures out of sandstone in 1882. The flagellation of Christ by two men is depicted. |

|

|

| Petrus Grotto (2) | End of the 19th century | The Petrusgrotte is a niche chapel and was built as an artificial grotto . The scene with Peter regretting his behavior on the morning of Good Friday when he had denied Jesus is not part of the actual Stations of the Cross. ⊙ | Johann Jacob Schoy possibly created the baroque stone figure around 1722, which is placed in the artificial rock grotto. |

|

|

| Maria Magdalena Chapel (3) | around 1660 | The chapel has a rectangular floor plan, a tent roof and a cross vault. The arched stone portal has wrought iron lattice wings and a skylight grille from the construction period. ⊙ | In the chapel there is a baroque figure of Maria Magdalena . |

|

|

| Herrgottruh Chapel (4) | around 1660 | Like most of the chapels of the Graz Kalvarienberg, this chapel has a rectangular floor plan with a triangular gable, round arch stone portal and wrought-iron lattice wings from the 17th century. At the side of the chapel there is a round arched niche with a statue of St. Veronica , who gave Jesus Christ a handkerchief. ⊙ | The Herrgottruh Chapel has a rich stucco decoration made of cartilage , a characteristic of Italian artists. Only since the 19th century does the chapel contain the depiction of Christ's rest, known as the “Herrgottruh”. A figure of Christ is shown waiting for the crucifixion. Originally there was a figure of the crowning of thorns in the chapel. |

|

|

| Kreuzfallkapelle (5) | around 1660 | The architecture of the Kreuzfall Chapel is similar to the other chapels. It is the third passion chapel and the last before the crucifixion group on the summit of the Calvary. ⊙ | The figures in the interior of the chapel date from the time it was founded. They show Jesus, who collapses under the heavy cross, and two baroque henchmen . The statue of Jesus was revised by Jakob Gschiel in 1873. |

|

|

| Lamentation Chapel (Virgin Mary's Sorrows) (7) | around 1660 | Along with the Mariatroster Chapel, the Lamentation Chapel is the largest building in the Calvary complex. The cross vault is supplemented with stucco in the auricle style . The two-bay building still has a roof with a crooked gable. ⊙ | In the interior of the chapel there is a group of figures with the Virgin Mary holding her dead son in her arms - a Pietà - and side figures with representations of St. John and Mary Magdalene. There are fields of cartouches painted on the ceiling. |

|

|

| Johannes Nepomuk Chapel (8) | 2nd half of the 19th century | Thematically, the Johannes Nepomuk Chapel does not belong to the rest of the Calvary complex. It stands on a slope on the murs side. ⊙ | The group of figures inside comes from the artist Philipp Straub . It was created in 1734 and depicts the fall of the bridge of St. John Nepomuk , which is said to have occurred in Prague in 1393 . Johannes Nepomuk has been venerated as a bridge saint since his canonization in 1729. |

|

|

| Mocking Christ Chapel (9) | around 1660 | The chapel has a portal flanked by columns. ⊙ | In the interior the scene of the Mount of Olives and the Capture of Christ are depicted, which stood at the beginning of the Passion of Christ and does not fit into the order of the Graz Way of the Cross. The figures are carved out of wood. |

|

|

| Mariatroster Chapel (10) | 1694-1701 | The Mariatroster Chapel was given this name as part of the donation of a picture of the Virgin Mary. Before that it was called the Dismaskapelle and was dedicated to the holy Dismas , who died condemned next to Jesus on the cross and repented of his crimes. ⊙ | The chapel has an oval floor plan. The interior is equipped with the high altar and various figures of saints. The group of the three Marys stands in a niche chapel in front of the chapel. |

|

|

| Sepulchral Chapel (12) | 1654 | The burial chapel is the oldest building on the Graz Calvary. A semicircular burial chamber adjoins the square anteroom . The roof lantern with twelve columns is intended to remind of the Jerusalem Church of the Holy Sepulcher . The coat of arms of the Barons von Maschwander, the founders and builders of the Kalvarienberg, can be seen above the portal. ⊙ | In the anteroom is a flat stone, a replica of the stone from the tomb of Jesus Christ. Behind a wall opening is a figure that represents Jesus in the grave. |

|

|

The Mariatroster Chapel

The original name of the Mariatroster Chapel was Dismaskapelle . Dismas was the criminal crucified next to Jesus on the right, who had shown repentance for his misdeeds in the hour of his death.

The foundation stone of the chapel was laid by the Seckau Prince-Bishop Count Rudolf Josef von Thun in 1694. The building has an oval floor plan, is structured with pilasters and is crowned by a lantern with a turret. The consecration took place in 1701. The date of construction is painted in a cartouche above the portal, which is flanked by figures of angels. Before the Dismaskapelle was built, a Rosalia chapel had stood here since 1668, which was built out of gratitude for having survived a plague epidemic . The chapel, which no longer exists today, is shown in a pilgrimage book from 1688. The oval chapel got its name from the then widespread worship of Dismas, which was discontinued in the Josephin reforms .

After the donation of a figure of Mary, which is located on the high altar and of the hll. Joachim and Anna , the parents of Our Lady, the interior was redesigned. The changed chapel was named Mariatroster Chapel . The ceiling consists of a flat dome with a fresco of the Assumption of Mary into heaven . It was designed by Matthias Schiffer and was created in 1803. The interior is decorated with figures of Saints Franz de Paula, Antonius, Clare, Dismas, Franz Xavier, Joseph, John the Baptist and Rosalia .

The group of the three Marys

In front of the Mariatroster Chapel, a small niche chapel is carved into the rock of the Austein. The chapel has the shape of a double arcade and was built around 1660, i.e. before the Mariatroster Chapel was built. Originally there were two female figures in the niche. This constellation was replaced between 1710 and 1725 by the group of figures of the three Marys that exist today. It is attributed to the workshop of the artist Johann Jacob Schoy. The mourning women at the grave ⊙ are Mary, the mother of Jesus , Mary Magdalene and Mary Salome, who is also called “the other Mary” in the Gospel. According to the Gospel of Mark, these women were present at the crucifixion and were the first to find the empty tomb after the resurrection of Jesus .

Wrought iron grille

The wrought-iron gates and fanlight screen of most chapels date from the period 1660 to 1700, the reign of Emperor Leopold I . The strict forms, "round bars and mostly tight spirals, are still used [in the early baroque], but imaginatively brought into several varieties" . The lattices signify a change from Mannerism to Baroque , the cartilage style is partially visible. A special feature of the Kalvarienberg grids is that they come from different creators.

The Flagellation Chapel, Maria Magdalena Chapel, Herrgottruh Chapel, Kreuzfall Chapel, Lamentation Chapel and the burial chapel have wrought iron gates and skylight grids of different designs:

The way to the Calvary

General

The processional path from downtown Graz to the Calvary on the Austein is almost forgotten. The path is marked by seven stations in the form of processional shrines, almost all of which are in their original locations. The starting point of the so-called “Grazer penitential processions” was the cathedral church . Via Hofgasse , Sporgasse and Murgasse the participants reached the Mariahilferkirche , the first stop. From there it went on to the nearby Lendplatz with the plague column as the second station. This was followed by Zeillergasse and the entire course of Kalvarienbergstraße to the portal of the Kalvarienbergkirche. Six of the seven wayside shrines accompany the pilgrim at regular intervals on the route, the seventh is right next to the church, the destination on the Calvary. The distance between Graz Cathedral and the Kalvarienberg is about 3.5 kilometers if you follow the old processional path.

Procession shrines and torture pillars

The seven stone pillars are a symbol of the seven sorrows of Mary . On the pillars are "tabernacle-shaped" essays with partially preserved donor inscriptions. The pillars were erected between 1660 and 1662. The unity of shape and size is unparalleled for Graz. The top of the wayside shrines rest on smooth pillars with surrounding acanthus relief friezes . They are closed at the back. The visual design of the respective wayside shrine is different. The original pictures, which showed biographical waypoints of the Messiah and stations of the Cross of Jesus Christ, were replaced between 1966 and 1997 by depictions by the painter Adolf Osterider . Detailed information on the individual wayside shrines and the torture column can be found in the overview table:

| designation | Location with coordinate | information | image | detail |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wayside shrine I | at Zeillergasse 25 ⊙ | Due to the traffic situation, offset from the original location by about one meter. The panel depicting the circumcision of Christ from the late 18th or early 19th century was replaced in 1997 by a depiction of Adolf Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine II | at Zeillergasse 55 ⊙ | The picture shows the flight to Egypt, also in 1997 by Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine III | in front of Grimmgasse 9 ⊙ | In 1966 the wayside shrine was moved to a square-like piece of meadow. Its original location was the front garden of the house at Kalvarienbergstrasse 45. The oil painting "Christ is found in the temple" (1966–1970) is by Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine IV | at Kalvarienbergstraße 63 ⊙ | The oil painting "Carrying the Cross" (1966–1970) is by Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine V | at Kalvarienbergstraße 82 ⊙ | In 1967 the wayside shrine was moved. The new building at Kalvarienbergstrasse 93 stands in its original location. The oil painting “Death of Christ on the Cross” (1966–1970) is by Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine VI | at Kalvarienbergstrasse 121 ⊙ | The original location of the processional shrine, which was moved in 1968, was two to three meters west of its current position. The oil painting "Descent from the Cross" (1966–1970) is by Osterider. |

|

|

| Wayside shrine VII (14) | west of the Kalvarienbergkirche ⊙ | The original panel from the second half of the 18th or early 19th century has been replaced by a modern illustration. The oil painting “Burial of Christ” (1997) is by Adolf Osterider. Opposite the wayside shrine is a column of torture. |

|

|

| Pillar of torture (13) | west of the Kalvarienbergkirche ⊙ | The processional shrine VII stands opposite the torture column. |

|

|

Of the seven wayside shrines, wayside shrines III, V and VI were relocated between 1966 and 1968, the numbers I, II, IV and VII remained in their original locations. Wayside shrine VII stands out due to its prominent location next to the Kalvarienbergkirche. Plans to put the staggered wayside shrines in their original position in order to reconstruct the character of the processional path were not implemented.

literature

- Walter Brunner : The Graz Calvary . rk Pfarramt Graz-Kalvarienberg, Graz 1987.

- Alois Kölbl, Wiltraud Resch: Paths to God. The churches and synagogue of Graz . 2nd, expanded and supplemented edition. Styria, Graz / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-222-13105-8 , pp. 143-147 .

- Karl A. Kubinzky, Astrid M. Wentner: Grazer street names. Origin and meaning . Leykam, Graz 1996, ISBN 3-7011-7336-2 .

- Erich Renhart (Ed.): The Grazer Kalvarienberg. History, meaning and claim. A documentation . Steirische Verlagsgesellschaft, Graz 2003, ISBN 3-85489-087-7 .

- Horst Schweigert : Graz (= The art monuments of Austria . = Dehio -Handbuch Graz. = Dehio Graz. ). Revision. Schroll, Vienna 1979, ISBN 3-7031-0475-9 , pp. 152–156.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazerstraße name. P. 46.

- ↑ Heimo Widtmann: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Path and destination p. 49.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg p. 71.

- ↑ Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazer street names. Pp. 207-208.

- ↑ Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazer street names. P. 363.

- ↑ Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazer street names. P. 410.

- ↑ a b Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazerstraße name. P. 209.

- ↑ Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazer street names. P. 208.

- ↑ Kubinzky, Wentner: Grazer street names. P. 267.

- ↑ Timetable of the route 67 Zentralfriedhof to Zanklstraße ( Memento of the original from July 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ A b Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg p. 67.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg p. 68.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg pp. 68–69.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg p. 69.

- ↑ a b Robert Pretterhofer: At the three crosses. Religious and liturgical life on the Graz Calvary p. 103.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg p. 70.

- ^ Walter Brunner: Grazer Kalvarienberg. From Austein to Kalvarienberg pp. 71–72.

- ^ Friedrich Bouvier: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Conservation distress and acts of vandalism pp. 121–125.

- ^ A b Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 77.

- ↑ a b c Schweigert: Dehio Graz. P. 152.

- ↑ a b c Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 78.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 79.

- ↑ a b c Schweigert: Dehio Graz. P. 153.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations pp. 79–80.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations pp. 80–81.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 80.

- ^ Schweigert: Dehio Graz. Pp. 153-154.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 81.

- ↑ a b c Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 84.

- ^ A b Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 87.

- ^ Schweigert: Dehio Graz. P. 154.

- ^ A b Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations pp. 84–85.

- ↑ a b Schweigert: Dehio Graz. P. 154.

- ↑ a b c Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 85.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 86.

- ^ Schweigert: Dehio Graz. P. 155.

- ^ A b Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 88.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations pp. 88–89.

- ^ A b Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 89.

- ↑ a b c Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 91.

- ^ Wiltraud Resch: Grazer Kalvarienberg. Art historical considerations p. 90f.

- ↑ Kuno head: A touch of Athos p. 152.

- ↑ a b Kuno head: A touch of Athos p. 153.

- ↑ Ulrike Aggermann-Bellenberg. Quoted from: Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of the urban structure of Graz p. 49.

- ↑ Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of the urban structure of Graz p. 51.

- ↑ Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of Graz's urban structure, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ a b c d Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of the urban structure of Graz p. 55.

- ↑ Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of Graz's urban structure, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ a b c Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Calvary and its seven processional shrines as elements of the urban structure of Graz p. 56.

- ↑ Heimo Widtmann: Path and goal. The Kalvarienberg and its seven processional shrines as elements of the urban structure of Graz pp. 56–57.