Urban development and planning in Heilbronn

The urban development and urban planning in Heilbronn describes the urban development and urban planning of Heilbronn as a former imperial city (in 1371) to the center of the eponymous district (1938), the city (1970) and later to the regional center of the Regional Association Heilbronn-Franken (1973/2003) in Baden -Wuerttemberg . Future forecasts range from that of Mayor Hoffmann of a "Neckar town from Lauffen to Bad Friedrichshall" to the incorporation of the "places between Flein and Friedrichshall ... in Groß-Heilbronn ...."

The place with the Franconian royal court, called villa Helibrunna in 822 , received city rights in 1281. In the course of its history, the city of Heilbronn acquired various villages such as Altböckingen (1333), Neckargartach (1341), Böckingen (1342/1431), Flein (1385) and Frankenbach (1430/38). As the upper administrative city of Württemberg in 1802, Heilbronn lost the villages it had acquired, and new suburbs emerged from 1839 on the basis of Louis de Millas' urban plan . In 1873 Reinhard Baumeister drew up a general building plan that was to connect the suburbs with a ring road. As part of an administrative reform, Heilbronn became an independent city in 1938 . At the same time it became the seat of the new district of Heilbronn . In 1938 Neckargartach and Sontheim were forcibly incorporated. After the city was destroyed in World War II, Karl Gonser received the order for a general development plan in 1947. Volkart's urban plan for the reconstruction of the old town was recognized as "one of the best in the country", with "this work being the ... 1st prize ...". In 1964, the regional planning community Württembergisches Unterland , consisting of the city and district of Heilbronn and individual communities, created the regional plan 72 . The regional development axes named in the regional plan wanted to be integrated into the Heilbronn tram network as part of the urban development of Heilbronn. In the 1970s, with the incorporation of Klingenberg (1970), Kirchhausen (1972), Biberach (January 1, 1974), Horkheim and Frankenbach (April 1, 1974), Heilbronn became a major city. With the preparation of the regional plan in '72, the regional planning community ended its work. It was replaced by the Franconian regional association with Heilbronn as the regional seat (regional center). As part of the BUGA (2019) , the city is currently planning a new suburb known as the “Neckarbogen” (formerly: “Neckarstadt”) north of Bahnhofsstraße at the former old and new “Floßhafen”.

The reconstructed city eagle made of sandstone, which was installed in the Great Council Chamber, is a symbol that urban planning should also be carried out for future generations: “The old eagle that I ... reassembled and which is up here ... as a symbol in the gable , should remind and admonish us that we do not plan for today and tomorrow, but for generations, and that we create the home for tomorrow today. " This " maintains ... the constant connection between the old and the new Heilbronn " .

City and imperial city (1281/1371)

Heilbronn developed from a Franconian royal court that existed in the 7th century. Various theories arose on the development of Heilbronn's settlement around the royal court in the early Middle Ages.

Willi Zimmermann suspects the place of the former Franconian royal court on the site of today's Deutschhof, with the first town center of Heilbronn in the form of the villa Hanbach being built in front of the Deutschhof . That is why it is not today's market square, but the Deutschhof that forms the "heart of the settlement". This is the earliest settlement core with the oldest church in the city; the Michael's Basilica . According to Hans Koepf, remains of the Palatine Chapel are to be found in the walls of the extensions in the south of today's cathedral of the Deutschhof, west of the Romanesque tower choir . According to Max Georg Mayer and Christhard Schrenk, foundation walls made of limestone were found on the south wall of the tower that are older than the Deutschhaus from 1225. In the south of Kirchbrunnenstraße, the court community developed with streets concentric to the Deutschhof. The argument is that the ancient street of today's Frankfurter Strasse leads in a straight line to the gate of the Deutschhof, where the gate of a Boppon count castle and the Franconian royal court was suspected. Frankfurter Strasse was part of an old Franconian royal road , which was called " Alte Hällische Strasse " and led to Schwäbisch Hall . At the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, a new city was created north of Kirchbrunnenstrasse “through a conscious act of founding”. In the north of the "separation line" (Kirchbrunnenstrasse), a new town has therefore formed, which differs from the settlement core in the south due to its planned layout and vertical street. Werner Heim confirms this thesis and also suspects the Deutschhof located south of Kirchbrunnenstrasse as the location of the presumed royal court: "The focus of the oldest settlement Helibrunna was therefore without a doubt south of today's Kirchbrunnenstrasse".

Julius Fekete assumes that the Deutschhof is not the place of the former Franconian royal court and suspects the royal court and chapel in the area of the former Katharinenspital at Gerberstrasse, Kaiserstrasse and Untere Neckarstrasse. While the Deutschhof was not settled archaeologically until 11/12. In the 19th century, a Franconian settlement with a cistern from around 635 (± 45 years) was found in the area of the hospital and the western Kaiserstraße. The cistern was used from the Merovingian period until at least the late Carolingian or early Ottonian period. A copper engraving from Civitates Orbis terrarum shows that the St. John's Church , which could be regarded as the St. Michael's Basilica in Heilbronn, also stood at the Katharinenspital . The presumed western part of the royal court was located lower than the hospital grounds and would therefore have been flooded from 1333 by the damming of the river. The first “main street” is Gerberstraße, which was originally called “the street”. This would continue in a street on Deutschhof - the "Landstrasse". Noteworthy is the “well-known peculiarity of the medieval street layout” in Heilbronn. Deutschhofstrasse has been relocated so that the outbound and inbound traffic should not obstruct each other. The first town center is said to have been surrounded by ramparts, moats and palisades. These are said to have been fortified later with a city wall that ran along the Lohtor-, Sülmer-, Fleiner- and Kirchbrunnenstraße. Evidence for this are the remains of a city fortification found on Sülmerstrasse in the 1930s.

Heilbronn was awarded in 1281 by King Rudolf I of Habsburg in Gmund the city charter and enlarged the territory of the imperial city of Heilbronn with the villages Altböckingen (1333), Neckargartach (1341) and Böckingen (1342/1431). In 1371 Heilbronn received an imperial city constitution from Emperor Charles IV and further expansion followed with the acquisition of Flein in 1385 and Frankenbach in 1430/38.

Württemberg Oberamtsstadt (from 1802)

After the Revolutionary Wars, Duke Friedrich II of Württemberg was compensated by Napoleon with areas on the right bank of the Rhine, including Heilbronn, after the Duke ceded his areas on the left of the Rhine to France. Heilbronn fell to Württemberg and became the seat of the new Heilbronn Oberamt , whereby the four villages of the former imperial city of Heilbronn became independent communities within the Heilbronn Oberamt, in which serfdom was abolished.

Suburbs

In 1802 Heilbronn was still surrounded by a medieval city wall reinforced with towers . The city fortifications with up to ten towers had three gates at that time: the bridge gate, the Sülmertor and the Fleinertor. A first general plan of the city only provided for a small area for the future new building sites. An exact division was not made. In 1808/1809 new plans should open up further building areas; a suburb in front of the Fleinertor was to be created as the first new part of the city outside the old city of Heilbronn, from which a road should lead to Flein. New building squares were planned to the right and left of the road planned as the main axis.

The city council commissioned building officer Bruckmann to lead the urban construction work. Bruckmann's plans were recorded and drawn by the geometer Wuerich . This is how development plans for the Sülmer and Fleiner suburbs were created. In 1831, however, the municipal council only approved the plans for the Sülmer suburb. As a result, in 1838 Bruckmann's second development plan for the Fleiner suburb was again not approved.

In 1838 the city commissioned the city architect Louis de Millas to draw up a city plan. In the minutes of the municipal council of September 20, 1938 it said:

"After H. Stadtbaumeister de Millas has now arrived, it is decided in relation to the production of a general building plan for the local city and a plan to connect the Fleiner and Sülmer suburbs to commission the construction of such a building to the city building authorities ..."

In September 1840, de Millas' new urban development plan with the planning bases for additional development in the old town and new building areas outside the former city wall was approved by the Oberamt and the district government. The 1840 plan was based on the plans from 1806. Furthermore, the urban planning ideas of the city architect Wepfer , de Millas' predecessor, were included. The minutes of the municipal council stated that the city architect Wepfer should be asked to communicate his ideas about a connection between the Fleiner and the Sülmer suburbs to the city council before he left.

The town plan from 1840 was based on the urban planning principles customary at the time, namely to build “suburban squares” in front of the gates of the old town. These suburbs were planned as rectangular building quarters of the same size and were unrelated to the topographical conditions. They were also not included in an overall urban planning concept. The urban planning principle was quite simple. In this way, the network of suburban squares could be expanded where it was found to be necessary. Regardless of the topography, this "linear and spatially perceived rigid system" was extended over the new building areas.

In addition to the town plan, building statutes formed the legal basis for planning from 1840 onwards. They regulated the development in the old town and in the urban expansion areas. The town planning was controlled by a strict handling of the regulations created by development plans and building statutes, but "without a safe direction and without overarching urban planning".

- Planning regarding the suburbs of Heilbronn

Traffic planning

In 1873, Reinhold Baumeister from Karlsruhe drew up a general development plan whose basic urban planning concept consisted in particular of traffic planning. The main traffic structure was formed by the “Zentralstraße” - today's Kaiserstraße - and the “Ringstraße”, of which only the north and east roads were realized.

Kramstrasse (today Kaiserstrasse) was to be converted into a central street. It was broken through to the east and connected to Heilbronner Allee . The avenue emerged from the former city moat, which was used as a rubble and rubble dump after the city wall was torn down. After the Heilbronn merchants Bläß , Koch and Kreß founded a stock corporation in 1846 , the moat was filled in and an avenue was laid out on it.

A ring road, of which only the north and east roads were built, was supposed to connect the newly created suburbs. However, due to the construction of the industrial railway and the south station in 1901, it was not possible to continue Riesenstrasse in the south via today's Silcherplatz to Rathenauplatz . From Rathenauplatz, the Ringstrasse was to lead along today's Knorrstrasse over a fourth Neckar bridge to the station suburb in the west. Oststrasse is the last part of the giant road that Baumeister planned but never completed .

- Buildings that arose on Zentralstrasse (Kaiserstrasse) when the road to the east was broken and connected to Heilbronner Allee

House Kaiserstraße 27 . Client: Heilbronner Gewerbebank. 1902 sold to Adolf Grünwald and Abraham Sigmund.

House Kaiserstraße 31 . Client: Louis Kreiser, master butcher. Architect: M. Keppeler. From 1914 owner Heinrich Grünwald . 1920 owner Konrad Morlock (Café-Restaurant Morlock). .

House at Kaiserstraße 29 ; built by the construction company Koch and Mayer around 1897 based on designs by the architects Hermann Maute and Theodor Moosbrugger .

House at Kaiserstraße 25 (1898) Client: businessman Victor Alfred Schneider. Architects: Ernst Walter and Carl Luckscheiter. From 1918 owner of the Darmstadt bank for trade and industry ( Gumbel- Kiefe banking business ). 1932 owner of pharmacist Manfred Koch. 1934 Barbarino shop. .

House Kaiserstraße 23 1/2 , built by the construction company Koch and Mayer around 1897 based on designs by architects Ernst Walter and Carl Luckscheiter .

Kaiserstraße 40 in Heilbronn. Built in 1898 for Adolf Grünwald and Ernst Pfleiderer according to designs by the architect Heinrich Stroh, main facade facing Kiliansplatz.

Kaiserstraße 40 in Heilbronn, side view of Kaiserstraße.

Semi-detached house Bauknecht & Graeßle , based on designs by the architect August Dederer

Semi-detached house A. Mössinger's heirs , designed by Heinrich Stroh

Incorporations

On March 29, 1930, a municipal ordinance was issued that made compulsory incorporation possible if there was a public need for it. The Böckingen municipal council then submitted an application to the state of Württemberg for compulsory incorporation, which President Eugen Bolz endorsed at the plenary session of the state parliament on March 16, 1932, because Böckingen could not perform the tasks of a medium-sized town due to the low tax income. However, the city of Heilbronn asked the state government not to initiate any direct incorporation. On April 23, 1933, Heinrich Valid was appointed State Commissioner for the municipalities of Böckingen and Heilbronn. The new state commissioner declared: "During the duration of this regulation, in which the powers of the Heilbronn municipal council and the Böckingen municipal council are combined in my hands, I am therefore authorized to unify the two municipalities by expressing my will" . Political representation in the local council was not granted to the new Böckingen district. In 1938 the settlements in Kreuzgrund and Haselter were founded in Böckingen .

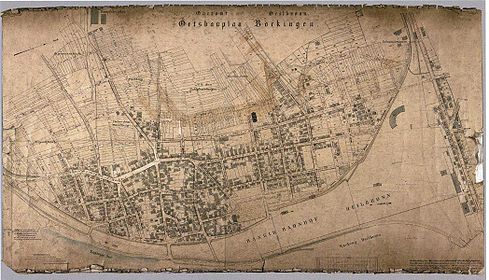

- Heilbronn-Böckingen site plan (1901)

Independent city (1938)

As part of an administrative reform, Heilbronn became an independent city in 1938 . At the same time Heilbronn became the seat of the new district of Heilbronn . Heilbronn was the second largest city in Württemberg with 72,000 inhabitants .

Incorporation in 1938

Neckargartach was incorporated on October 1, 1938, because as early as June 1933 a state commissioner commissioned by the Württemberg Ministry of the Interior had certified "that the municipality can no longer exist as an independent municipality due to its financial circumstances." Even before the Second World War, Neckargartach the new building area Steigsiedlung developed and the urban development of the district took place. On October 1, 1938, Sontheim was also incorporated into Heilbronn.

Area renovation in 1939

In Heilbronn in 1939 a structurally deficient, narrowly unhealthy district on the Neckar ( Fischergasse district ) was to be completely demolished (renovated). A new town hall and the new district administration were to be built on the vacated area. The Heilbronn town planning officer commissioned Paul Bonatz and his master class with this investigation. In the end, there were two pieces of work that were to be submitted two days later with the improvements recommended by Bonatz. The urban development problem consisted of integrating the new buildings of the town hall with district building with the existing historical buildings such as the Deutschhof and integrating them into the street space. Heinrich Röhm built a plasticine model on the specified submission date in two days and tried to correct it at Bonatz as an unknown third man . At the second appointment, the correction lesson , Röhm's submission was a minor sensation. Röhm got to know Bonatz and became his student. Bonatz made him the suggestion to carry out his sketch of ideas about the new buildings as a diploma thesis. Röhm wrote his diploma thesis (with a grade of “very good”) on the old town of Heilbronn under the title “Area renovation of the Fischergasse district and construction of a town hall with a district building.” The design was purchased by the city of Heilbronn.

Reconstruction (1945–1969)

Construction plan, general development plan and ideas competition

After the air raid on Heilbronn , the city center, i.e. the former old town, was 100% destroyed. The city of Heilbronn without its districts was 84% in ruins. Initially, it was suggested that the field of ruins in the city center should be left as a memorial. In 1946 there were 26,557 inhabitants in the core city of Heilbronn; A total of 51,568 lived in Heilbronn. Of these, 24,025 were male and 28,666 female. Most of the shops were in basements, ruins, and shelters.

On February 18, 1946, compulsory voluntary service was introduced to remove the rubble in the old town.

In March 1946, the mayor of Beutinger commissioned Hans Volkart, city planner, to draft a plan of the old town . In 1946, government architect Karl Gonser and the traffic expert Karl Leibbrand, both from Stuttgart, were commissioned to create a general development plan for the inner city. On November 22nd, 1946, Volkart, Gonser and Richard Schumacher , who worked unsolicited on the planning of the old town, presented their designs to the new mayor Paul Metz and the local council after five months of planning.

The local council decided in February 1947, at the suggestion of BDA chairman Richard Scheffler (1891–1973), to advertise an ideas competition for the reconstruction of the old town. This received 28 contributions.

On June 20, 1947, Volkart, Gonser and Kurt Leibbrand submitted their plans again to the local council, which welcomed the drafts. CDU City Councilor Hilger described Volkart's idea as "overwhelming". Volkart was annoyed that, despite his plans, an ideas competition had also been advertised. Nevertheless, he worked with Karl Gonser on the jury of the jury, which also included Theodor Heuss , the first minister of education in Württemberg-Baden . General Building Director Walther Hoß was also a member of the jury . Mayor Metz chaired the meeting.

Hoss presented his old town solution: a traffic-calmed Kaiserstraße, starting with Gerberstraße and Kramstraße all the way to Allee. Only pedestrian passages led through final buildings with arcades on both sides of Kaiserstrasse. The traffic should be connected to the avenue via Kram-, Allerheiligen- and Fleiner Straße. A pedestrian promenade was planned between the right bank of the Neckar and the residential buildings. The left bank of the Neckar was planned as a bypass road and should close the traffic ring around the old town. The eastern Kram- und Gerberstraße was used for development . A pedestrian zone in Sülmer- and Fleinerstrasse was planned. Large parking lots between Klara-, Kilian-, Allerheiligen-, Deutschhofstraße, Fleiner Straße, Kiliansplatz , Kaiserstraße and in the northern part of the old town were planned.

As part of the old town competition, Volkart declared his maps on November 9, 1947: In his opinion, the streets and alleys needed to be widened. This is the only way to ensure “healthy living and working”. A reallocation of building land is necessary for this. Fixed points for the planning are the "engineering structures" that a "benevolent fate ... saved from destruction". As the “typical features of the old town, ie the city of Heilbronn in general”, they are fixed points in the planning.

Volkart had a traffic planning approach for the old town, which he described as the “yolk in the egg”. He planned a pedestrian zone that was to be laid out around the market square and around Kaiserstrasse. The Kaiserstraße should be traffic calmed between Sülmerstraße and Gerberstraße. The pedestrian zone should be surrounded by Fleiner-, Sülmer-, Lohtor-, Gerber- and Deutschhofstraße, which should still remain passable. An arcade building above Kaiserstrasse, east of the confluence of Kramstrasse and Gerberstrasse, should mark the beginning of the traffic-free street. When the architects' prizes were awarded on November 11, 1947, Kurt Marohn received the second prize and the architects Hermann Wahl and Rudolf Gabel with Hannes Mayer each received a third prize.

The design by Hellmut Weber , former Le Corbusier employee , which largely envisaged flat roofs in the city center, did not receive an award . In the jury's justification, the modern architecture was rejected: "The architectural attitude is modern, but the work differs too much in part from the character of the grown city".

Government Building Director a. D. Schweizer described Volkart's urban planning draft as one of the best in the country, with "this work being the missing 1st prize". According to the opinion of the jury, the Volkart-Plan realizes the basic ideas of the jury.

Some of Hoss' main ideas would also have matched the ideas of the jury.

The urban planning goals of the jury consisted of traffic and architecture concepts: The traffic concept consisted of keeping long-distance traffic away from the old town in an east-west and north-south direction; Both Friedrich-Ebert-Straße (today's Kaiserstraße) and Sülmer- and Fleinerstraße were not supposed to become “fast, wide channels”; the “inner core of the old town” was to become a pedestrian area: development from Friedrich-Ebert-Brücke via Kramstraße and Gerberstraße, a traffic ring around the old town via the avenue and a bypass road on the left bank.

The architectural-artistic concept of the old town design included the preservation of the traditional architecture ( heritage protection architecture ). The jury said: “The character of the old town should remain Heilbronnish ”, this had the prerequisite “that any schematic was avoided.” On June 11, 1948, City Councilor Willy Dürr described the goals of the reconstruction in Heilbronn's voice: “We want ... no modernism of an anonymous city, but we have to rebuild the old town so that it is Heilbronn again and only Heilbronn ”.

The question of the style in which Heilbronn's old town should be rebuilt was the subject of numerous discussions. A decision was made in favor of a traditional, conservative modern and rejected the completely new modern with steel, concrete and glass.

“ What style do you build? : Of course, some connoisseur of the matter ... will ask, in which style should [Heilbronn] be rebuilt? Without a doubt, one can go two ways here. You can tear down the last remnants of what is already there and embrace a completely new, modern style. That would mean that one would have to build in steel, concrete and glass ... In Heilbronn, however, the decision was made in favor of a softer, more traditional modernism [of the Stuttgart School ] ... and within the prescribed basic idea of the architect's individuality, there is largely room for maneuver. "

Existing historical architecture should not be built in, but rather strengthened in terms of its spatial effect in terms of urban development: “... the historical buildings [should] be enhanced in their effect through individually designed squares and streets. The streets and squares are to be laid out in such a way that the Kiliansturm, but also the other historical buildings ... appear effectively ... The market square must be rebuilt in its historical spatial effect ... Friedrich-Ebert-Straße (Kaiserstraße) [ should] lead to the market square and to the 'Kilians dom ' as the heart of the old town… ”. The Kaiserstraße was widened to the south, so that "the view of the gem of Heilbronn, the Kiliansturm, was already cleared from the Neckar bridge."

An expert opinion by Paul Bonatz demanded that the height of the new buildings should be subordinate to the historical buildings: "The surrounding buildings [historical building stock] must be clearly subordinate". Lord Mayor Paul Meyle followed the urban planner's report and said, “that the city will not be built according to the wishes of the planning office alone, but also not according to the wishes of individual property owners and certainly not because of some company signs. He read ... the report by Paul Bonatz, highlighting the passage that speaks of the height of the building ”.

- Examples of the reconstruction in Heilbronn

Reconstruction (opening December 15, 1950): former furniture store Bierstorfer in Heilbronn by Julius Hoffmann (corner building Lohtorstraße 37 / Lammgasse 2)

The master plan

At the end of 1947 the general plan, a work by government builder Gonser and his railway expert Leibbrand, was completed. The aim of the general plan was to improve traffic conditions. Based on Gonser's traffic planning, a revised version of Volkart's old town planning was created. The citizens were informed about the construction plans in an exhibition Heilbronn builds on . The press wrote that care had been taken in drawing up the plans. The city can claim that it is one of the first destroyed cities to have a completed general development and construction plan for reconstruction. The Ministry of the Interior of Württemberg-Baden wrote about the plans on May 10, 1948:

“The Ministry of the Interior has carefully examined the planning documents you have submitted and expresses its full appreciation for what you have achieved so far. The Ministry of the Interior agrees that the submitted plans will be used as a basis for further processing and will be issued according to your proposal. "

Even the Württemberg State Office for Monument Protection said: “It is remarkable that the old structure of the old town will be adapted to the new needs, but it will not become just any ordinary city”.

The city planning office was commissioned to create a master plan for the reconstruction of the old town on the basis of the old town plan drawn up by Volkart and the result of the architectural competition. Government builder Rudolf Hochstetter was in charge . The winners Kurt Marohn, Rudolf Gabel, Hannes Mayer and Hermann Wahl formed a planning advisory board together with the judge and chairman of the BDA , Richard Scheffler , which was supposed to help the city planning office and its board member Hans Gerber with the development of the old town planning "by evaluating the competition results" . The old town was subdivided into 25 (later 19) blocks in order to draw up legally binding development plans. From the five-person planning advisory board, one architect was assigned to each block to support the city planners. On April 29, 1948, the construction framework plan for the new building of Heilbronn's old town was decided on the basis of Volkart's old town plan and the competition designs of the Heilbronn municipal council chaired by Mayor Paul Metz. In Württemberg-Baden, Heilbronn was the first major city to have such a reconstruction plan. That is why the resolution said: "Heilbronn is the envy of other cities because of this planning" On June 13, 1948, the framework plan was publicly displayed. Of the 889 landowners, 560 came to examine it, 120 raised objections, 22 did not agree with the new building line on Kaiserstraße.

The reallocation of building land

The plan of the old town, which had grown over the centuries, was to be preserved, but wider streets were to be created. From the construction plan decided on March 5, 1948, a building line plan was to be developed, for which the city measurement office was commissioned. Surveyor Fritz Herre, whose work was described by Rudolf Gabel as a "stroke of luck for Heilbronn", headed the newly created department from April 1, 1948.

On November 11, 1948 (according to another source on November 9, 1948), the municipal council decided, referring to the construction law of August 18, 1948 with the optional provision § 13 IV., That a share of 15% of each property in the old town should be expropriated, 5% should be compensated, the remaining 10% should be given free of charge. An old town association with 300 members resisted the 10% "free delivery". The local council gave in and decided on October 5, 1950 to reduce the property tax for individual cases: “In exceptional cases of hardship, the local council can decide to reduce the area deduction for individual properties”. In reality, "the area deduction is then not made in land, but in money". Gustav Binder, the former head of the appraisers and fire department commander, had collected property appraisals from three decades; the properties could now be assessed on the basis of these documents.

The approval of the allocation plans for the individual blocks took years. The last reallocation plan for the Kirchhöfle block was approved on February 10, 1955. Before the reallocation, the old town was divided into 1,086 parcels of 20 hectares and 70 ares, which belonged to 889 participants. The reallocation increased the traffic area by 3 hectares and 47 ares; the remaining 582 parcels of 500 participants were reduced to 17 hectares and 23 ares.

Traffic planning

One goal of the new traffic planning was to free the city center from through traffic, which in the pre-war period still led through Fleinerstrasse and Sülmerstrasse as the north-south axis and through Kaiserstrasse as the west-east axis. Karl Gonser and Kurt Leibbrand drew up a first traffic plan, which envisaged a ring road surrounding the city center. Gonser’s traffic planning wanted to develop the avenue as a ring road and relocate the Böckinger marshalling yard to the eastern edge of the industrial area along Neckarsulmer Strasse. However, no funds were available for relocating the shunting systems and redesigning the main station, so that the "Gonser'sche Ring" failed. Later, the university professors Wilhelm Tiedje , Hannes Mayer and Carl Pirath proposed a "rectangular traffic system with two parallel streets each in north-south and east-west directions". Beutinger wanted to prevent the Neckar from being filled in for a new north-south connection, whereby "one of the boldest ideas [...] once was a road on stilts over the river along its course". Only the northern branch of the Neckar was filled in to build Mannheimer Strasse, one of the two planned west-east connections as an extension of Weinsberger Strasse to the west and over Weipertstrasse to the Bleichinselbrücke. The western tangent, which was supposed to close the ring road, was never realized.

However, the Altstadtring was realized , the part of Gonser's traffic planning that planned the design of the avenue as a ring road. This was to connect Turmstrasse, Allee, Götzenturmstrasse and the upper and lower Neckarstrasse. In contrast to the medieval city, in which the market square was the center, the Alleenring was to become the “new urban center” in terms of urban planning, with shops, the old theater , cinemas and the post office. The Altstadtring was given “new urban accents”. Crystallization points at a historical location were Berliner Platz and Wollhausplatz.

The Wollhausplatz from the 1950s was “once celebrated as an urban planning throw”. On December 21, 1950, the swimming pool of the reconstructed old pool on Wollhausplatz was opened for swimming. Well-known Heilbronn artists such as Wilhelm Klagholz (gargoyle), Maria Fitzen-Wohnsiedler and Hermann Brellochs (fountain) had contributed to the reconstruction. The reconstruction of the old city bath was preceded by a “dispute of opinions”, “whether the old bath should be rebuilt or a new one should be built elsewhere”. "The majority of the local council decided to rebuild the old baths". So according to the plans of the building authority [...] "a usable functional building" was created. "Representative high-rise buildings" were later built on Wollhausplatz, such as the Heilbronner Voice skyscraper, which was inaugurated in 1957 based on plans by Gustav Ernst Kistenmacher , which the Heilbronner Kreissparkasse built in 1958 based on plans by Kurt Häge , Herbert Alber , Gustav Ernst Kistenmacher and the Hans- Rießer-Haus, a Protestant community center from 1962 based on plans by Herbert Alber and Richard Scheffler .

The theater building on Berliner Platz was also rebuilt as a further focal point at a historical location. After on June 8, 1950 "the finance committee of the Württemberg-Baden state parliament [...] for the Heilbronn city theater for the 1950 accounting year 35,000 DM had been approved", on January 29, 1951 the "city theater ruin" or the "stage of the city theater building" was received a canopy. In 1960, a high-rise building with a high level of tension and tension was built on Berliner Platz, based on plans by Willi Ulmer .

The Alleenring, which was implemented as part of Gonser's traffic planning in the 1950s, was redesigned again in the 1970s under the mayor of building Herbert Haldy and the head of the urban planning office Rasso Mutzbauer, whereby here, too, crystallization points were at the historical location of Berliner Platz and Wollhausplatz: " After Heilbronn has been a major city since January 1, 1970, the city center should also have a metropolitan appearance by 1980. Two shopping centers on Wollhausplatz [...] and Berliner Platz [...] are planned as the most important projects. The avenue will be the most important connecting line between these two centers. "

After the high-rise buildings erected in the late 1950s and early 1960s, further high-rise buildings were built on Wollhausplatz. The old district office ("Langer Otto") built according to plans by the architect Rolf Winter was inaugurated on October 1st, 1971. The construction of the “Long Otto” was only intended to be the pioneer of the structural restructuring of the square: “With the new building of the District Office, popularly after District Administrator Otto Widmaier , also known as“ Long Otto ”, the Heilbronn cityscape undoubtedly has one The old bath was blown up on February 19, 1972 in favor of the Wollhauszentrum , a building and shopping center, as the first restructuring of Wollhausplatz . The demolition of the old bath was justified with a new dominant urban development, which should represent Heilbronn as a shopping town and regional center of the Franconian region: "According to the municipal council, Wollhausplatz should experience a dominant urban development [...] Undoubtedly not only the cityscape wins, but also the attractiveness of Heilbronn as a shopping town and regional center of the Franconian region. ” Willy Schwarz was the only one in the Heilbronn local council to vote against it, criticizing the“ brutal intrusion into the cityscape ”and believing that the city would“ lose its tradition ”. In October 1975 the Wollhauszentrum opened on the site of the old town bath that was blown up in 1972. The shopping center includes the Kaufhof with a supermarket, an office tower, an underground car park and a bus station.

The old theater on Berliner Platz was blown up on July 18, 1970 in favor of a new shopping center and planned new building. At the time, people were very happy about the demolition: “It is particularly pleasing that the old theater has meanwhile given way to a planned new building”. At the same time, the avenue underpass was built and the 60-meter-high shopping center opened on November 11, 1971.

- Buildings on Altstadtring (avenue)

Cityscape maintenance

The primary goal of maintaining the cityscape during the reconstruction was to restore the historical cityscape, to reconstruct historical buildings that defined the cityscape or at least to keep them in their historical external appearance. According to Emil Beutinger, the “reconstruction of historically important and significant buildings in the cityscape” should be carried out to “remember a great city history” . The aim was to try to "turn the historical buildings that were at least left as ruins into points of crystallization of the new, so that Heilbronn remains Heilbronn".

- the town hall with archive building and market square with tower of Kilian's Church. After the city planning office had issued a development plan on the old basis , which included the reconstruction of the new chancellery , the north wing of the old town hall and the archive , the planning of the building councilor Heinrich Röhm from the municipal building department in 1949 only the main building of the old town hall was rebuilt. The interior was built according to plans by the Stuttgart architect Peter Bonfert .

- the port market building , a former monastery building with port market and port market tower . While only an arcade of the cloister remained of the port market building and was set up at the meat store, the port market tower was rebuilt in 1952 according to plans by the building councilor Heinrich Röhm from the municipal building department.

- the then historical museum (former meat and court house) with the Teutonic Order Cathedral and Teutonic Order Court . The reconstruction of the minster took place from 1951 to 1954 under the direction of Rudolf Gabel. The Renaissance buildings of the Small Teutonic Order Court were reconstructed from 1958 to 1959 according to plans by Richard Scheffler, with well-known Heilbronn artists such as Walter Maisak , Erich Geßmann and Maria Fitzen-Wohnsiedler participating in the interior . However, the facade of the former knight's hostel from 1556 had to be demolished and reconstructed. Before construction began, around 625 m³ of limestone masonry had to be chiseled out of the foundations.

- Historically important and significant buildings in the cityscape

Big City (1970)

In the 1950s, Heilbronn's population grew steadily. In 1955, around 80,000 people lived in the city. In 1960 there were 88,000 inhabitants, 58,000 of whom lived in the city center. In 1960 the urban planning comprised almost forty development plans. In 1960, the area between the Achtungsstrasse and the Rosenbergbrücke, the Äußere Lerchenberg, the Käferflug on the Wartberg and the site of the former Moltke barracks were developed in particular. In 1970, eleven development plans were processed for a total area of 195 hectares, which provided for 7,500 apartments for 24,000 people. The development plans should be completely drawn up and legally binding by 1980. In addition, seven large new development areas with 340 hectares for 34,000 people with 10,000 apartments were planned. In 1970 the municipality continued to act as the client for ten different urban building construction projects. These included the women's clinic, the new indoor swimming pool at the Bollwerksturm, three schools, gyms, conversions in schools and the expansion of the kindergarten. The costs amounted to 58.5 million DM. The local council created the prerequisites for “urban construction” by making appropriate changes to the development plans. These set new accents in city architecture. These included the Laspa house (Alexander Kemper, 1972), Kilianspassage (Kurt Mahron), model house (Otmar Schär, 1969), telecommunications office, building Paul-Göbel-Straße 1, shopping house (Schaal 1971), district office (Rolf Winter, 1971), Rosenberg high-rise (Schaal, 1973).

- Urban design

New districts

As part of the municipal reform in Baden-Württemberg , the municipalities of Flein, Horkheim, Frankenbach, Biberach, Kirchhausen, Nordheim, Nordhausen, Untergruppenbach, Talheim, Leingarten and Unterrheinriet should be compulsorily incorporated into Heilbronn as part of the target planning of the Ministry of the Interior. The communities could also integrate into the city voluntarily. On July 1, 1973, the state government announced the final target planning for the community reform and on January 1, 1975 the community reform ended. Historically, Heilbronn played a central role in the surrounding communities. Böckingen, Flein, Frankenbach and Neckargartach were imperial towns until 1802. Böckingen, Sontheim and Neckargartach were forcibly incorporated into the 1930s. In the 1970s Klingenberg, Kirchhausen, Biberach, Frankenbach and Horkheim volunteered to be incorporated into Heilbronn. As a result of the incorporation between 1970 and 1974, the Heilbronn district increased from 6134 to 9985 hectares. Klingenberg had 272, Kirchhausen 1147, Biberach 1058, Frankenbach 889 and Horkheim 485 hectares. This increased the municipal area by 63%. The population grew by 17.4% from 99,700 to 117,049 inhabitants. The urban district now had 115,924 inhabitants, while the district had 232,151 inhabitants in 46 municipalities. By 1978, almost fifty million marks had been spent on the newly incorporated communities. The places designated by the Ministry of the Interior Flein, Nordheim, Nordhausen, Untergruppenbach, Talheim, Leingarten and Unterrheinriet were not incorporated into the city of Heilbronn.

Incorporation of Klingenberg

Klingenberg had developed into a workers' community in the 20th century. There was a lack of industrial and commercial enterprises and the corresponding financial strength. Because the town was no longer able to raise the costs it had incurred, it had been working closely with Heilbronn since the late 1960s. The new development area Wolfsglocke with 271 inhabitants, the neighborhood secondary school with Böckingen, the connections to the Heilbronn sewage treatment plant and the gas supply were examples of a successful collaboration in 1967. To secure the water supply, the place sought a connection to Heilbronn. The operation by the municipal transport company had failed in the 1960s due to objections from the concession holders - the Federal Post Office and the German Federal Railroad. On June 21, 1968, Mayor Hoffmann and parts of the city administration were present at a municipal council meeting in Klingenberg. The minutes said: “In a good, friendly atmosphere, interesting questions relating to the development of zoning plans, water and gas supply, traffic relations and dirt road maintenance were discussed.” Issues of incorporation had not been discussed, but both sides agreed that the joint collaboration would result in an incorporation. In January 1969 9 residents of the Klingenberg new building area Wolfsglocke formed a citizens' initiative. As a result, the Klingenberg municipal council should decide to incorporate it into Heilbronn. The long-established residents of the place also agreed to the initiative after initial hesitation. The mayor of Klingenberg, Rolf Hagner, declared on January 13, 1969 that Klingenberg would hold talks with the district administrator Otto Widmaier and the city. Commissions were set up especially for this purpose and were supposed to draw up an integration agreement. This was approved by both the Klingenberg and Heilbronn municipal councils at the beginning of June 1969. As an advance payment for the integration, Klingenberg was connected to the Heilbronn water supply on July 15, 1969, which cost the city 130,000 DM. On September 14, 1969, the citizens' hearing took place in Klingenberg, with 737 of 984 voters casting their vote. 688 (93.3% of the population) voted for incorporation. On September 26, 1969, the local council initiated the necessary steps and on December 18, 1969 both sides signed the integration agreement. The Baden-Württemberg state parliament passed a corresponding law that same month, according to which Klingendenberg could be incorporated on January 1, 1970. On January 1, 1970, a delegation from Heilbronn, consisting of Mayor Hoffmann and his entourage, moved into Klingenberg and wore the inscription: "The youngest city greets its obstetricians!" “We are citizens of Heilbron and don't do anything. Me len koi sau'res girl standing and au koin full of tankards ”. As a result of the incorporation, Klingenberg received a secure water supply, connection to the city bus service, an expansion of the through-town and the field path network and a renovation of the old village center. Statistically, Heilbronn became a big city. Due to the 1684 Klingenberger, the population of Heilbronn grew from 99,300 to 101,383. With this, Heilbronn was in 60th place in the FRG, ahead of Rheydt and behind Kaiserslautern.

Incorporation of Kirchhausen

In November 1971 the mayor of Kirchhausen, Hubert Straub, announced that confidential talks had been held with the city of Heilbronn regarding incorporation. Alternatively, Straub proposed an administrative partnership or a merger with Leingarten. A citizens 'meeting was held on February 19, 1972 and a citizens' hearing on February 27, 1972. 1235 of 1746 eligible voters cast their vote. 706 (57% of the population) voted for voluntary integration into the city of Heilbronn. The integration agreement stated: “This integration is intended to create good conditions for the personal development of the residents in the Heilbronn-Kirchhausen district by adapting to urban conditions, including in particular a diverse range of services and the provision of the necessary facilities The Kirchhausen municipal council approved this contract in their meeting on April 7, 1972 with a 9-2 vote. This was followed by the approval of the Heilbronn municipal council on April 20, 1972. Mayor Hoffmann and Mayor Hubert Straub signed the integration contract on April 21, 1972. However, the Heilbronn district administration and the district council did not want Kirchhausen to be incorporated into Heilbronn. The place did not have a common border with Heilbronn and there were fears that other places distant from Heilbronn wanted to be incorporated. The places in between would then have to be included in the Heilbronn urban district as part of state planning. Finally, with one abstention, the district council objected in June to the incorporation of Kirchhausen into Heilbronn. The integration agreements enacted between the two municipalities, which provided for the construction of a multi-purpose hall with a small swimming pool in Kirchhausen, were approved by the regional council of North Württemberg with a decree dated June 28, 1972. On July 1, 1972, Kirchhausen was incorporated into Heilbronn. The city of Heilbronn honored its investment commitments, which were contractually regulated in the integration agreements. The “Deutschordenshalle” was completed in Kirchhausen on September 13, 1974, and a heated outdoor swimming pool was completed on May 16, 1979 in accordance with the integration agreement. Kirchhausen also received a merger bonus of 3.5 million DM and a new local constitution, according to which the new district was entitled to direct participation through the local council and the local council until 1989. During the time of incorporation into Heilbronn, two industrial areas emerged, such as the “Mühlberg” industrial area in the northeast and “Härkersäcker” in the northwest of Kirchhausen. Residential areas that arose with the incorporation are the "Steigsiedlung" and the "Breitenäcker".

Incorporation of Biberach

On November 13, 1971, it was publicly announced that the first confidential negotiations between Biberach and Heilbronn had taken place at the administrative level. In the course of the district reform, the location was assigned to the Heilbronn district by the target planning. In spring 1971 the Biberach municipal council decided to investigate the possibilities of municipal reform. The mayor of Biberach, Wolfgang Frenzel, said that the town and Kirchhausen had spoken to Heilbronn about the conditions for integration. A Horkheimer paper that came out in February 1972 presented the results of all negotiations. In January 1972 a Heilbronn draft to incorporate Kirchhausen and Biberach was approved by the Heilbronn municipal council. A public hearing in Biberach on February 27, 1972, however, showed that the majority of the Biberach were against the incorporation. Of the 1741 eligible voters, 1426 cast their vote, while 1140 voted no. The mayor of Biberach, Wolfgang Frenzl, was unable to officially give a recommendation for integration into Heilbronn. He declared, “You shouldn't give up the independence of a community without good reason.” Between 1972 and 1973, the Böllingertal Hall was built in Biberach . After the citizens' hearing had taken place, the Biberach municipal council voted 7: 4 on June 6, 1973 for voluntary incorporation into the Heilbronn district. As a result, Mayor Hoffmann and the mayor of Biberach, Wolfgang Frenzel, signed an integration agreement, which became legally effective on January 1, 1974. The incorporation agreement provided for the construction of a sports and festival hall and the construction of a small swimming pool. Part of the contract was also the promise that Biberach, as a district of Heilbronn, should receive its own local constitution and an administration close to the people. The state of Baden-Württemberg granted Biberach the sum of 3.7 million DM as a merger bonus because the town had met the formal requirements for integration with the public hearing. On May 11, 1974, the Heilbronn district of Biberach received a branch library in the old Biberach schoolhouse. In 1976, according to the integration agreement, Biberach got a small indoor pool and in 1976 the town hall. Residential areas that arose with the incorporation are the "Steinäcker" and the "Mausal". On April 12, 1981, the first performance exhibition took place in the Böllingertalhalle, another sports and event facility.

Incorporation of Horkheim

Horkheim has already worked with Heilbronn on the issue of sewage, the connection to the Heilbronn gas supply and the city bus service. However, the majority of the residents felt that there was no need to act quickly with regard to the further development of the community and only hesitantly dealt with the changes due to the community reform in the village. Nevertheless, the council member Theodor Köhn (SPD) submitted an application for integration into Heilbronn. However, in February 1972 the Horkheim municipal council rejected the application with 10: 1 votes and refused to draw up an integration contract with Heilbronn. In July 1973, when the state government planned its goals, it was clear that Horkheim and Frankenbach were to be incorporated into Heilbronn. Thereupon OB Hoffmann Horkheim offered in writing to negotiate a voluntary incorporation. At a citizens' hearing in Horkheim on January 20, 1974, only 460 of 1730 voters took part. Of these, 277 were for inclusion. On January 21, 1973, the Horkheim municipal council decided with 9: 2 votes to agree to the incorporation from April 1, 1974. Heilbronn promised to develop building land for Horkheim, to renovate the town center, to build a sports center and to build a joint indoor swimming pool for Sontheim and Horkheim. The agreement was signed by Mayor Hoffmann and Mayor Kurt Wellar on January 25, 1974. After the incorporation, the investment commitments promised by the city of Heilbronn in the incorporation contract were kept and Horkheim received the weir hall on December 12, 1975.

Incorporation of Frankenbach

In 1972 the community of Frankenbach had almost 5000 inhabitants. As early as 1968, the Frankenbach mayor and local council had spoken to Heilbronn about residential construction, business development, land use plans and the interdependence of the two communities. The mayor of Frankenbach, Kurt Britisch, spoke out in Bad Moll in May 1968 in favor of Frankenbach's independence. In October 1973, however, the Talheim town council decided to negotiate the question of integration into Heilbronn. In a closed meeting, the municipal council approved the agreements made with Heilbronn. A citizens' hearing took place on January 20, 1974. Only 1324 of 3370 eligible voters gave their vote. 929 voted no to the inclusion. In spite of this, the Frankenbach municipal council decided on January 25, 1974 with 10: 2 votes “for reasons of reason” to incorporate it into Heilbronn. On January 28, 1974, the integration agreement was signed by Mayors Kurt Britisch and Hans Hoffmann. The agreement provided for the expansion of the Frankenbacher sports facilities by five tennis courts and a football field and the construction of a sports hall and indoor swimming pool. The Leintalsporthalle was inaugurated on August 18, 1978 in Frankenbach. In accordance with the integration agreement, Frankenbach also received an indoor swimming pool with a small outdoor pool

Heilbronn efforts to Talheim / Flein

In 1973 Flein had 5080 and Talheim 3300 inhabitants and for Heilbronn it seemed appropriate to incorporate the two places. They bordered on the district of Heilbronn and more than half of their employees worked in Heilbronn, went shopping there and sent their children to secondary schools there. Flein was connected to the sewage treatment plant in Heilbronn and had a neighborhood school with Heilbronn in Sontheim-Ost. Flein was easy to reach via the municipal transport company and was able to bring his garbage to the landfill in Heilbronn. Flein's mayor, Ernst Clement, spoke out in March 1971 at a citizens' meeting in favor of waiting before incorporating it into Heilbronn. The assembled citizens, however, called on the local council and mayor to preserve Flein's independence. In 1975 the local council decided to reject an incorporation into Heilbronn with 13: 0 votes. The formation of a unified community with Talheim, which was envisaged in the state government's target planning, was also not accepted.

On May 13, 1971, the Heilbronn municipal council approved the draft integration agreement that it had developed with Talheim mayor Robert Ehrenfried. With the integration of Talheim into Heilbronn, Flein would have been automatically assigned to Heilbronn as part of the regional government's target planning. A citizens' hearing in Talheim in June 1971 showed that the majority of citizens refused to integrate. 1825 out of 2090 eligible voters cast their vote and 1136 voted no. Finally, on July 5, 1971, the Talheim town council also refused to be incorporated into Heilbronn. In November 1972 the Talheim municipal council decided with 8: 3 votes regarding the integration again to establish non-binding contacts with Heilbronn. At a citizens' hearing on June 24, 1973, 52.1% wanted integration. 47.9% rejected it. Nevertheless, on the same evening, the Talheim municipal council again rejected the integration in a closed session with a 9: 4 vote. Werner Föll justified this as follows:

“It was easy for the opponents of the alliances to create a mood. Even if there was a change in opinion among the electorate, this did not mean that the local council went along with it. In a community like Talheim there was one representative in the local council for every less than 300 inhabitants ... So the fear of losing one's own political influence is understandable and understandable "

The state government and parliament granted both places municipal independence.

Old town parts

The expansion of the Heilbronn urban district with the incorporation of new districts put a strain on the relationship with the old town districts of Böckingen, Sontheim and Neckargartach. They were incorporated into Heilbronn in 1933 and 1938 respectively. Heilbronn still had outstanding obligations towards them, which arose from the war and the subsequent burdens of reconstruction: “At that time, people in the old parts of the city of Böckingen, Neckargartach and Sontheim were amazed to see the city's commitment to the new . But there, too, striking signs have now been set for a new beginning. In Alt-Böckingen it was the community center completed in 1975 and in Sontheim and Neckargartach the magic word was urban redevelopment. "

Boeckingen

In 1960 the urban development plans already included the preparatory work for the residential areas of Schanz, Schollenhalde and Trappenhöhe in Böckingen. The construction of the residential area on the Schanz is an example of the building policy of setting up large estates on the edge of the city area: “The time when Heilbronn will become a big city is already foreseeable today ... It is the day when the one planned in Heilbronn-Böckingen Apartments are about half occupied. During the day Heilbronn is practically a big city, because 22,500 commuters come to Heilbronn every day […]. Housing construction also has to keep pace with industrial developments. However, the city cannot expand to the east and north, as the vineyards there are under landscape protection. An expansion of the urban area should therefore take place on the heights west of the Neckar. ”In 1960 there were already 17,000 people living in Böckingen, while 58,000 people lived in the Heilbronn core city. In 1966, the Heilbronn municipal council decided on a 50 hectare residential area for 6,000 residents on the Schanz in Böckingen, which was "quite controversial at the time because of its dimensions [...]". From 1965 to 1975 the new residential areas Schanz-Nord and Schanz-Süd were created . The Elly-Heuss-Knapp primary school (1971), the Protestant kindergarten Schanz-Süd (1972), the sixteen-story residential building on Güglinger Strasse (1972), the Richard Drautz Foundation's home for the elderly (1973) were also built on the Schanz . the Elly-Heuss-Knapp-Gymnasium Heilbronn (1973), the Schanz-Sporthalle (1974) and the Elly-Heuss-Knapp-Hauptschule (1975). The Heinrich v.Kleist secondary school (1971) was established in the Böckinger Kreuzgrund . In Haselter in Böckingen, the district vocational school center was inaugurated on August 19, 1975, with the commercial, domestic and agricultural district vocational school. 1975 was in Böckingen Mansion Böckingen designed by the architectural group Brown-Keppler-Stieglitz hall, restaurant, meeting rooms and public library branch opened.

Neckargartach

As early as 1960, 7,000 people lived in Neckargartach, while 58,000 people lived in the Heilbronn core. Therefore, in the 1960s, new building areas arose west of the old town center, while the new building areas Sachsenäcker and Im Fleischbeil were developed in the south . In 1960, the urban planning of the city of Heilbronn also included the hospital grounds in Neckargartach. During the time of the regional reform , Neckargartach was renovated in 1976, but is characterized by the loss of historical building fabric.

Sontheim

An industrial park was already designated in the post-war period. In 1960, the urban planning also included the future state engineering school in Heilbronn . Between 1970 and 1974 the residential area in Sontheim-Ost was built in the east and north-east of Sontheim. As a result, Sontheim has grown together with Heilbronn. The Evangelical Home Foundation's retirement and nursing home was also built in Sontheim-Ost on Max-von-Laue-Straße (1972). From 1976 the Bottwartal Railway no longer served the Sontheimer Bahnhof . Student dormitories followed (1978) and a new school center with a sports hall. In the 1970s and 1980s, the district was redeveloped.

Local communities

The development of Heilbronn into a big city was viewed with concern in the Heilbronn District Office and in the municipalities of the district "how Heilbronn wanted to increase its influence". That is why the state government presented a concept to integrate the city of Heilbronn into the district. The Heilbronn municipal council then issued an opinion on June 25, 1970 on the district reform formulated in the state government's model of thought. In December 1970 Heilbronn approved the draft of the District Reform Act (Administrative Reform Act). Flein, Horkheim, Frankenbach, Biberach, Nordheim, Nordhausen, Leingarten, Kirchhausen, Unterrheinriet, Untergruppenbach and Talheim were to be integrated into the administrative area of the city of Heilbronn. In the “Regional Plan 72” approved by the Ministry of the Interior, Flein, Leingarten, Nordheim with Nordhausen, Talheim and Untergruppenbach with Unterheinriet were among the local communities. The local area Heilbronn was redefined by the regional plan '72, whereby "the border of the local area Heilbronn would not coincide with the new city district border created by the regional reform, but would extend beyond it." It was important to exercise the sub-central functions of the city Heilbronn for the communities in the vicinity. From 1961 to 1970, the proportion of commuters to Heilbronn in the local communities of Flein, Leingarten, Nordheim, Talheim and Untergruppenbach rose from 42% to 48%. The school links between the local communities with Heilbronn were stronger in 1970 than with the new districts. In 1973 the local public transport network also extended to the local communities: in 1973, Flein was served by the city bus network with frequent bus routes. A train bus drove to Leingarten. Nordheim was served by both a train and a post bus. A private bus drove to Talheim, which drove to Neckarwestheim. A post bus drove to Untergruppenbach that drove to Löwenstein.

Traffic planning

In 1969 the electrification of the Heilbronn-Jagstfeld-Heidelberg railway line began. In 1970, the connection of the city to the intercity network via Heidelberg was planned for the winter timetable 1971/72, but was never implemented. In February 1971, Heilbronn launched an initiative to accelerate the Heilbronn – Nürnberg, Heilbronn – Würzburg motorway connection. The city was also committed to improving rail connections. The electrified Heilbronn-Jagstfeld-Heidelberg railway was inaugurated on September 21, 1972. Since May 28, 1973, Osterburken could be reached by electric locomotives from Heilbronn. In 1974 the construction of the railway line to Crailsheim was to begin. In 1974 the route Heilbronn-Würzburg of the federal highway was opened. From June 1, 1975, the railway line to Würzburg was also electrified, making the Jagst valley accessible by train and motorway. Mayor Hoffmann tried in vain to extend the Stuttgart-Bietigheim S-Bahn to Heilbronn. There were also major road construction works in Heilbronn. This included the long-term Neckartalstrasse project on the left bank of the Neckar Canal. It was built in sections and ended in December 1970 on Saarlandstrasse. The section of Neckartalstrasse between Horkheim and Neckargartach was still at the planning stage. In 1974 the other section from Saarlandstrasse to Böckingen was implemented. The through-road from Klingenberg and Karlsruher Straße, the industrial bridge as a connection to the industrial area, the section of Wilhelm-Leuschner-Straße as part of the sun well solution, the avenue underpasses and the completion of the Römerstraße were also built. In addition, development measures were carried out, such as the Neckarau, Großgartacher Straße and Mühlberg industrial estate, the Rampacher Tal Schanz-Süd, Sontheim-Ost, Breitenäcker, Landeslesstraße and Rosenberg development areas. There were also major changes in traffic in the city center. In November 1971 the section of Fleiner Strasse between Kiliansstrasse and Große Bahngasse became the first pedestrian zone. December 1971 the pedestrian zone was extended to the upper Sülmerstrasse. In 1974 it was extended in Sülmerstrasse to the Nikolaikirche.

The "structural focus formation" and the publicly operated local transport should take place according to the regional plan '72 along the development and regional development axes: Development axes existed on the north-south axis along the Neckar valley and the west-east axis from Kraichgau to Hohenlohe . There were also three “regional development axes”: “It is an axis through the Zabergäu , another from Heilbronn via Ilsfeld , Auenstein and Beilstein (Schozach-Bottwar Valley) and the construction axis through the Jagsttal , branching off at Bad Friedrichshall from the Neckar valley axis. "

In 1973 the local public transport network extended to these axes: A train bus drove to the Schozach-Bottwartal, as to Ilsfeld and Beilstein. In the Zabergäu, a post and train bus drove to Brackenheim . In the Kraichgau, like to Leingarten and Eppingen, a train bus and to Hohenlohe like to Weinsberg and Öhringen also a train bus.

Regional center of the Franconian region - "regional capital" (1973)

On the way to the Franconian regional association

From 1963 to November 1973, the predecessor of the Franconian regional association , the Württembergisches Unterland planning community, existed in accordance with the state planning law of 1962. Only the city and district of Heilbronn were members of the planning community. The districts of the Odenwald and Hohenlohe did not want to be included in a planning unit with Heilbronn at that time. Petersen emphasizes the importance of Heilbronn as a "central city", whereby he supports an expansion of the planning area with Heilbronn as the regional center:

“If the entire country is divided into regions, it is advantageous to make a delimitation in such a way that a balance of interests between high-performing and low-performing areas is possible within the region. The order problems of the agglomeration areas and the development problems of rural and structurally weak areas are certainly easier to solve in the network, since with a powerful central location as the center of the region. It makes little sense if the previous general urban-rural divide should be replaced and possibly increased by one from pure densely populated regions to pure agricultural regions. This principle is not met in particular by the planning community Württembergisches Unterland, which only includes the structurally strong urban and rural district of Heilbronn. Efforts to include structurally weak areas of the Odenwald and Hohenlohe in the planning community Württembergisches Unterland failed because the districts in question did not want to be ruled by the central city (upper center) Heilbronn "

In 1967, the regional planning community submitted a study by Hermann Haas, the head of the Institute for Southwest German Economic Research, “On the way to the Franconian region”. Haas commented on the term and the spatial extent of the "Franconian region" and also called it the "Baden-Württemberg Franconia region." Haas included the Odenwald area (with the districts of Sinsheim, Mosbach and Buchen) and the Tauberbischofsheim / Hohenlohe area (with the districts of Öhringen, Künzelsau, Mergentheim, Crailsheim and Schwäbisch Hall) and the Heilbronn area (with the city and district of Heilbronn).

With the Second Law on Administrative Reform (Regional Association Law) of June 26, 1971, regional planning was assigned to the Franconian Regional Association on January 1, 1973 . with the Oberzentrum Heilbronn as the regional seat. When the Oberzentrum was assigned on January 1, 1973, Heilbronn not only became the seat of the Franconian Regional Association, but also the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Chamber of Crafts. Both chambers have now adapted their catchment area to the newly created regional boundaries: "The headquarters of both economic chambers remained in the new regional capital [Heilbronn]. So Heilbronn emerged from the turbulent years of reform much stronger." The Franconian regional association received a smaller area without the Odenwald . The Odenwald area was assigned to the "Lower Neckar region". The Franconian planning region now only consisted of the districts of Heilbronn, Hohenlohe , Schwäbisch Hall, the Main-Tauber district and the urban district of Heilbronn. It had 750,000 inhabitants (1973) and with 4875 km² was the largest region of the nine regional associations of Baden-Württemberg. Almost 40% of the employees in the city of Heilbronn came from the Franconian region. It existed until 2003. When the state planning law was amended on May 20, 2003, the Heilbronn-Franconia regional association was created with its seat in Heilbronn for the area of the Heilbronn district and the Heilbronn, Hohenlohe , Main-Tauber and Schwäbisch Hall districts.

The Heilbronn-Franken region is East Franconian and South Franconian within the Upper German dialects. East Franconian is spoken in the Heilbronn-Franken region mainly in the Hohenlohe region around Crailsheim and Künzelsau and in the Taubergrund around Tauberbischofsheim and Wertheim . South Franconian is spoken in the Heilbronn-Franconia region around the center of Heilbronn .

Herbert Hellwig emphasizes Heilbronn as the center of a planning region in the Oberzentrum Heilbronn. The importance of the city as a central location in the course of the last 200 years. :

"... the city of Heilbronn [is] the administrative center and dominant center ... The resulting unification of several great districts into one planning region appears ... as a happy solution, as essential parts of the catchment area of the city as a regional center will become one in the future Franconian region with the center Heilbronn Administrative and planning unit summarized ... In this regard, Heilbronn will in future occupy a key position in the northeastern part of our federal state. This appears not only because of the traditional connection of large parts of this area to the city, but also because a further expansion of the catchment area of the City of Heilbronn as a regional center can only go in this direction ... in the area northeast and east of Heilbronn ... no other regional center competes with Heilbronn ... as a result, Heilbronn is usually the only better-known large city there that has the M aßstänke sets for the assessment of a central location "

City center planning (Deutschhofplatz / Landerer-Park)

On November 7, 1985, the Heilbronn municipal council made a fundamental decision on city center planning. This planned to set up a two-storey underground car park on the property of the former Landerer site. The city-owned square was to be designed into a park-like facility together with the area between Deutschhof and Horten department store. This should make the south-western front of the Deutschhof visible in full.

Joachim R. Bertsch depicted the planned park in an acrylic painting created in 1991 . In the background the long facade of the Deutschhof building is shown; crowned by the historic towers that dominate the cityscape of the old town: the tower of St. Peter u. Paulskirche and the Kiliansturm. The painting “Visions: Deutschhofplatz” represents a plea for the construction of the planned Deutschof Park; According to Bertsch, the overbuilding in favor of a shopping center would impair the Heilbronn cityscape and historical, architectural structures:

“Bad visions of the future of the Heilbronn cityscape plague Joachim R. Bertsch. The KBH chairman indicates in expressive, two-dimensional acrylic paintings what can happen if there is no global rethinking: that oversized shopping malls destroy the last old architectural structures ( 'displacement process' ) "

Cityscape master plan

The Stuttgart city planner and architect Michael Trieb created a cityscape plan ( Trieb plan ): "The building and facade types that were created in the course of reconstruction are to be viewed as a design basis for further development" in the case of redesigns and new buildings, in order to capture the "characteristics of the rebuilt Heilbronn" to be preserved… In future, the city will have to orient itself towards the cityscape master plan for design statutes and development plans. ”The drive plan also provided for several redesigned squares in the city center. For example, a Nikolaiplatz at the Nikolaikirche, a museum square at the Fleischhaus, a Gerberplatz at the intersection of Zehentgasse / Gerberstrasse and also a Deutschhofplatz consisting of two squares that are to be created at the confluence of Metzgergasse and Deutschhofstrasse and between Deutschhof and Horten.

On December 17, 1987, the Heilbronn municipal council approved the drive plan . The city planning office was commissioned to produce an annual report on the projects in the old town based on this model. The beauty of Heilbronn city center or why a cityscape frame plan? aimed "to make the original guiding principle of the reconstruction taking into account the historical Heilbronn ... easier to read and experience." Typical features of the urban architecture of Heilbronn's old town are accordingly buildings with plastered facades, pitched or hipped roofs, with facade edging with eaves profiling. Gaps in the old town are to be closed with buildings that have these typical features of the Heilbronn urban architecture of the reconstruction.

Since the regional council in Stuttgart does not place the grown cityscape of Heilbronn under monument protection, a conservation statute like in Böckingen, a design committee, a foundation or a municipal protection list should prevent “further building sins”. According to the city councilor Karl-Heinz Kimmerle, the Greens have sent the local council a corresponding application. Such a list was drawn up as early as the 1980s, but has been lost. The Local Agenda 21 showed under the motto "the second destruction of Heilbronn" on March 2nd, 2010 a slide show at an event, which was supposed to illustrate the destruction of historical buildings since the Second World War. The SPD discussed fundamental questions on how to deal with the grown cityscape of Heilbronn.

The municipal council groups of the SPD and the Greens submit applications for which they demand a conservation statute in accordance with building and planning law. In this preservation statute, the city center is also to be protected in the style of the 1950s, which according to the artistic reconstruction plan of Pof. Hans Volkart in baroque- home style was built because "the lack of high-quality architecture prewar increasing the importance of successful post-war architecture." "Urban planning and city-historical aspects should also play a role". These houses may "only be rebuilt or demolished if a municipal council resolution has been brought about."

Suburb

As part of the Federal Garden Show (from 2019), various urban development projects will be promoted. The fruit shed area or the site of the former bus depot north of Bahnhofstrasse is to be the site for the 2019 Federal Horticultural Show. The area is then to be converted into a new Neckar suburb with a Neckaruferweg.

The competition was followed by a master plan and then a master plan for the Neckarvorstadt. In 2008, an international urban design ideas competition was announced. At the beginning of June 2009, a jury consisting of the urban planner and architect Franz Pesch from Herdecke , the landscape architect Jörg Stötzer from Stuttgart and the architect and urban planner Kunibert Wachten from Dortmund selected the Munich architects' group Steidle and t17 landscape architects as the winner of the urban planning ideas competition Masterplan Neckarvorstadt . The draft intends to make the former raft harbor usable again and to create a new building area there. The former Carlshafen is to become a swimming lake. By mid-2010, the architects should develop an urban planning framework for the design of the Neckar suburb.

A landscape planning implementation competition was announced in summer 2010; detailed plans for the permanent facilities of the Heilbronn Federal Horticultural Show were submitted by spring 2011; the winners were determined in 2011. The approved urban development framework plan for Neckarvorstadt describes the main features of the new district on the central fruit shed area. In 2012, the implementation of planning law followed; The earthworks started in 2013. The construction (2017) [obsolete] of the exhibition is to follow. After the master development as part of the Federal Garden Show 2019, it will be dismantled in 2020; The Neckarvorstadt is to be built in 2021. The costs for the new district amount to 138 million euros, of which the municipality bears 113 million euros. Land already acquired cost 17 million euros; whereby the municipality raised 12 million euros. After 2019, an additional 18 million euros will have to be raised. The new district costs a total of 122 million euros.

| Framework schedule | Suburb "Neckarbogen" | Federal Garden Show |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | competition | |

| 2009 | Master plan | |

| 2010 | Framework plan | |

| 2011 | Competition (permanent systems) | |

| 2012 | Planning law Wasserschifffahrtsamt | Planning (permanent systems) |

| 2013 | Land management | Construction (permanent systems) |

| 2014 | Competition (exhibition) | |

| 2015 | marketing | |

| 2016 | Competition (construction phase) | Planning (exhibition) |

| 2017 | Construction (construction phase) | Construction (exhibition) |

| 2018 | ||

| 2019 | Master development | Federal Garden Show |

| 2020 | Demolition of the Federal Horticultural Show | |

| 2021 | Neckarvorstadt |

Traffic planning

- Neckarvorstadt

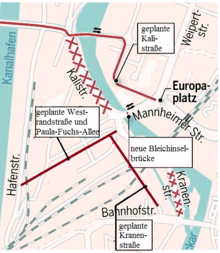

After planning, the Kalistraße will be relocated to the other side of the Alt-Neckar, so that a Neckaruferpark will be created. The future Kalistraße is to lead from Europaplatz over Karl-Nägele to Peter-Bruckmann-Brücke and then on to Saarland and Neckartalstraße. Kranenstrasse is to be relocated. In future, the new Kranenstrasse will run west of the Hagenbucher multi-storey car park under the railway line towards Westrandstrasse and Bleichinselbrücke.

The master plan originally provided for a road network concept for the Neckarvorstadt, which should also include a connecting road from the Kali- to Hafenstraße. It was supposed to run in the northernmost part of the fruit shed area between the former Fruchthof Nagel and the Peter-Bruckmann-Brücke. Since this road is now being dispensed with, the construction of the last section of Hafen- / Albertistraße was approved from March 2010.

In the area at the so-called Sun Fountain, an entrance to the area of the Federal Garden Show 2019 is to be built. According to Heilbronn's First Mayor Margarete Krug, the “green corridor ... the whole area will be upgraded”. The site is to become the new center of Böckingen. A new traffic route is planned there. This is necessary because this point is seen as the bottleneck for traffic. The traffic on Großgartacher Strasse regularly collapses at peak times. This is made possible by the light rail operator AVG , who is planning a new depot for light rail vehicles on the area of the Böckingen marshalling yard.