Streets in Vienna

The Vienna road network currently includes (Feb 2014) 6,842 roads with a total length of 2,763 kilometers. 222 kilometers of this are main roads , the remaining 2541 kilometers and thus the majority of Vienna's roads are municipal roads . The shortest street is Tethysgasse (11 meters), the longest street is Höhenstraße (14.8 kilometers). In addition to the roads, there are more than 1,700 bridges , which add around 54 kilometers to Vienna's road network.

Street names

(Overview list, leads to the district-by-district lists)

Designations under road construction law

The generally accessible street names assigned in or by the City of Vienna are to be distinguished from designations that have been used to indicate traffic routes in road construction laws and ordinances of the Federal Government and the State of Vienna. So are z. B. more than 20 Viennese traffic areas part of Wiener Straße , the former Bundesstraße 1 connecting Vienna and Salzburg.

Klosterneuburger Straße , known as a street in the 20th district, is also the name of Landesstraße B 14 across Vienna. The Wiener Gürtel Straße (the official spelling that is not in accordance with the spelling) includes, as B 221, not only the belt with its various names, but also part of the Landstraßer Hauptstraße and the Schlachthausgasse in the 3rd district.

Including road construction law designations in city maps is useless, however, since the designations can only be seen in regulations and files, but not in the cityscape.

Use of traffic area names

The oldest verifiable names of streets, alleys and squares in Vienna are Hoher Markt (first mentioned in 1233) and Neuer Markt (1234). Most of these ancient names refer to markets.

House signs and the names of house and landowners were also used for orientation . Apart from saints, the oldest traffic areas named after a person are Josefsplatz, named after the emperor in 1780, in today's 1st district and Neumanngasse, known since 1796 in what was then the suburb of Wieden (4th district since 1850), named after the landowner and wagon entrepreneur Josef Neumann . For the longest time (as in cartography ), the names common among the residents or established by the landlord were used ; There were no official specifications at that time.

With the provisional municipal law of March 6, 1850, the suburbs were incorporated within the line wall , the area of the city multiplied. From 1861 (at that time today's 5th district was separated from the 4th district and the current division of districts 1–9, since 1874 1–10, created; in the meantime, the city walls had also been razed around the old town since 1858) an attempt was made in the To eliminate multiple occupancy of street names occurring in the urban area: Many streets and alleys in the former suburbs had to be renamed. Examples: Until then there was a main street in the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 9th district, a Piaristengasse in the 4th and one in the 8th district. For this purpose, the names of the traffic areas from the suburbs were recorded centrally by the Vienna city administration for the first time. Names were also transferred on this occasion. Example: The old Burggasse in the 8th district became Josefstädter Straße in 1862; the name passed to today's Burggasse in the 7th district in the same year.

In 1874 the process of eliminating multiple occupancies was repeated for the new 10th district, Favoriten , and in 1892 for the suburbs that were incorporated at that time, now districts 11-19 (there were a further 24 main streets after Czeike ). In the case of the incorporations in 1905 (21st district, Floridsdorf ) and 1938 ( Greater Vienna , districts 22–26, of which since 1954 only 22 and 23), the procedure was mostly similar.

The names of the traffic areas have long been suggested by the culture department in the City of Vienna and decided by the municipal council committee for culture.

Concrete naming

Names used

The names of the streets, alleys and squares in Vienna are mostly of historical origin; they are reminiscent of monarchs, old buildings, town centers, names of fields and waters. Especially since the construction of Vienna's Ringstrasse from 1858, when many new street names were needed in the new building areas around the Ring, and since the elimination of multiple names (see above) began in 1862, names after personalities from the fields of music , painting , literature and drama have become common . Until around 2000, designations after women were severely underrepresented; today more attention is paid to gender equality. According to a survey for a gender atlas presented at the end of 2015, only 356 of 4269 Vienna traffic areas named after people were named after women in 2015.

Overall remember z. B. over 300 Viennese streets to musicians. There are also the names of scientists and politicians (from Franklin D. Roosevelt and Per Albin Hansson to Ignaz Seipel , Karl Renner and Julius Raab ), often also of Viennese mayors (e.g. Kajetan Felder , Karl Lueger , Jakob Reumann , Franz Jonas , Bruno Marek ), city councilors and local councilors.

The naming of the alleys in some areas according to a specific theme has also become established. Example: the suburban settlement between Hirschstetten and Stadlau in the 22nd district, in which numerous alleys from Mohnblumenweg to Magnoliengasse are named after flowers.

The numbering of streets based on the American model, as it was introduced in the Simmeringer Haide in 1884 (before the incorporation of Simmering) , could not prevail: of the up to eleven "Haidequerstraße" only 1., 7., 8., 9th and 11th on the city map.

It is noteworthy that designations after buildings occasionally refer to structures that no longer exist. The Schottentor , the name of a square and a tram terminus on the Ringstrasse and since 1980 also the name of an underground station, has not existed since the 1860s because the city walls were demolished from 1858 onwards; the term has been used since then. The name of the Stubentor underground station , which opened in 1991, does not refer to an existing city gate. Here, however, the name was taken from the city's history; it was no longer in use before. The Rotunda Bridge over the Danube Canal is named after an exhibition building in the Prater that burned down in 1937 .

In the past, a combination of family name and street, street etc. was common (e.g. Stadiongasse , Schubertring , Reumannplatz , Billrothstraße), but today new streets are often named with full first and last names. In the past, this was only used in individual cases, such as parts of the Vienna Ringstrasse ( Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Ring , Dr.-Karl-Renner-Ring ). The use of any academic degrees as part of the street name is usually not used today.

Since the early 1990s, there has been unanimous agreement in the responsible municipal council subcommittee for naming traffic areas and it is common practice not to name traffic areas after companies, at best after company founders.

Renaming

Historically, renaming has taken place over the centuries. The names of the streets, alleys and squares in today's urban area have not been officially decided for a long time, but have developed from local customs (see above). During the expansion of Vienna from 1850 to 1938, double or multiple designations had to be eliminated again and again in order to provide orientation security.

After 1918, Red Vienna renamed some traffic areas named after the Habsburgs. So was z. B. in the 9th district from the Elisabethpromenade the Rossauer Lände , the Maximilianplatz became the Freiheitsplatz (today Rooseveltplatz).

During the dictatorship 1934–1938 , traffic areas named after left-wing people and institutions were renamed: In the 2nd district, Lassallestrasse temporarily became Reichsbrückenstrasse, and Volkswehrplatz became Erzherzog-Karl-Platz (today Mexikoplatz ).

During the Nazi era from 1938 to 1945 , numerous streets in Vienna were renamed, especially those named after Jewish , Austro-Fascist and Social Democratic personalities. An example of this is Arnsteingasse , which was named after the respected Jewish banker Nathan Adam von Arnstein (and is again today), but was renamed in 1938 in honor of the Prussian Field Marshal Blücher . Most of the renaming between 1934 and 1945 was reversed after the end of World War II .

Renaming is unpopular with neighbors and is therefore only carried out in rare cases today, for example if the person giving the name later turns out to be particularly historically burdened (see section below “Street names as political places of remembrance”).

The last renaming took place in June 2012: the Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Ring was renamed Universitätsring .

Renaming

According to the rules set by the municipal council, Viennese streets are only allowed to bear the names of people who died at least one year ago (“ intercalary period ”). Anyone can submit proposals for the naming of new streets to the relevant district council. The decision on new traffic area names is made in the municipal council committee for culture and science.

In recent years there has been a noticeable tendency for the City of Vienna to designate previously unnamed traffic areas (mostly small squares in the course of named traffic areas) in honor of well-known personalities. The specific addresses of adjacent buildings are regularly based on the street names that already existed.

The Bruno-Kreisky-Gasse next to the Federal Chancellery , for example, has no entrance to either the Federal Chancellery or the Ministry of the Interior on the other side of the alley , so there was no postal address. Further examples are Leopold-Gratz-Platz behind Parliament and the Kurt-Pint-Platz, Oskar-Werner-Platz and Bundesländerplatz traffic areas in Mariahilf as well as the Anna-Strauss-Platz in Hietzing.

The responsible cultural department of the City of Vienna justifies this practice with the fact that neighbors want to save address changes. Common, but now less used alternatives would be monuments, memorial plaques or the naming of residential buildings. Lately, many smaller parks that have not yet had a name have been named after well-known personalities.

Spelling reforms in 1901 and 1996

The general German spelling reform of 1901 did not have any effect on Viennese street names until years later: Joseph became Josef, Carl Karl, Rudolph Rudolf. Franz Josephs Quai became Franz-Josefs-Kai (for a long time only written in front of the quay with a hyphen), and Grüne-Thorgasse in the 9th district became Grünentorgasse.

The Vienna City Council decided on December 17, 1999 to adopt the 1996 spelling reform for street names:

- (PrZ 299-M07, P 49) In an amendment to the GRB of January 30, 1981, the principles of the Vienna Nomenclature Commission are supplemented for the spelling of traffic area designations and geographical names so that the New Spelling is generally used. The changed spelling on street boards, orientation number boards and the like as well as in personal documents is only to be taken into account in the case of new installation or reissue.

Since the new spelling can only be used in new documents to be issued, new texts to be written or new signs to be affixed, previous street signs could not be replaced and the decision was not actively communicated, ten years later the new official spellings are often still unfamiliar: E ss linger main road Harde ggg leaving (the new case was in 2010 opened Hardeggasse not applied on purpose, but without sufficient reason), ski III och, Nu ss dorfer street, ro ss except borders, Schoenbrunn castle sss treet etc. etc.

In particular, Wiener Linien and the publisher of a Vienna book plan, Freytag & Berndt , who communicate numerous topographical names, have not yet switched to the new spelling in their media and on their vehicles by 2016.

The street directories of all districts take the new spelling into account.

To date, it has remained open whether the spelling reform should be used as an opportunity to trace back ß-spellings in names that do not correspond to the original spelling to the original ss-spelling. For example, in 2006 the Anna-Strauss-Platz in Hietzing was named after the mother of the “Waltz King”; Initiatives to convert Johann-Strauss-Gasse to the original spelling of the family name are not known. The change is also pending at Rienößlgasse in the 4th district, named after Franz Rienössl.

Street names as political places of remembrance

The report on street names of Vienna since 1860 as political places of remembrance , compiled on behalf of the culture department of the Vienna city administration and published in July 2013, concerns 159 street names, of which 28 should be discussed intensively according to the recommendation of the scientific authors. The report is available with four electronic bundles of supplements on the Vienna city administration website. It was published in book form in 2014.

There are individual cases such as Arnezhoferstrasse in the 2nd district, where the report contradicts previous assumptions: Arnezhofer was the first pastor of the Leopoldstädter Church , an active role in the expulsion of the Viennese Jews in 1670 was assumed (in 2008 there was even a citizens' initiative that launched on this basis demanded the renaming after a Viennese woman who died in a concentration camp); however, this allegation has not been confirmed. In other cases, such as B. the Maria-Jacobi-Gasse , the report authors expect further clarifications ( Maria Jacobi , as Welfare City Councilor, was politically responsible for the events in the children's home at Schloss Wilhelminenberg , the extent to which she was informed was not clear at the time of the report).

Signage

In 1782, the government first ordered that street names be written on houses in Vienna (see section house numbers). Since the color of the lettering kept fading, this rule was unsuitable for orientation in the modern city.

Michael Winkler, who made the proposal for the house number system implemented in Vienna, produced the corresponding signs as a sign manufacturer on behalf of the city council from 1862 onwards . The individual streets were renamed, if no names existed. Streets and alleys running parallel to the ring , thus in the segment of a circle around the city center, received oval street signs. Radially, i.e. perpendicular to the ring, traffic areas leading out of the city were provided with rectangular street signs. In addition, the street signs of the individual (then nine) districts were given different border colors:

- 1st district: red

- 2nd district: purple

- 3rd district: green

- 4th district: pink

- 5th district: black

- 6th district: yellow

- 7th district: blue

- 8th district: gray

- 9th district: brown

Districts that were incorporated later received a red border. This regulation was valid until 1920.

It has been replaced by a new, uniform regulation. The frames of the traditional street signs of all districts were now painted uniformly red, the lettering, then still in Gothic script , was designed in red for squares and black for streets and alleys.

In 1923 the Fraktur no longer seemed appropriate to the “Red Vienna” . Now it wasn't just the coloring of the signs that was changed: completely new signs were installed. These were blue enamel signs with white Arabic district numbers (e.g. 13th, ) and Latin letters, as they essentially exist to this day. The spelling of the street names has been adapted to the spelling of the time (example: 3rd, Ungargasse instead of III. Landstrasse / Ungargasse ).

From 1926 to 1944, in the 2nd to 21st district, the street signs for the traffic areas across the radial streets were rounded off at the corners; such signs can still be found on buildings in isolated cases. This should make orientation easier; This was difficult to implement in the outskirts, where the course of the streets often shows no connection to the city center. All street signs in Vienna have been the same since 1944, with the exception of ensembles of historical architecture, in which copies of street signs have been attached according to the rules of 1862 (white boards, black Fraktur script) since the 1980s.

There are currently over 100,000 traffic area name boards in Vienna. Since they were attached at times of different writing rules and the exchange does not take place out of thrift, one sees numerous boards that do not correspond to the current writing rules. Examples:

- 22., Erzherzog Karl-Strasse, correct: 22., Erzherzog-Karl-Strasse (Vienna adopted the German rule of complete coupling in 1981 after decades of special regulation.)

- 2., Straße-des-May-First-May, correct: 2., Straße-des-May-First (coupling mistakenly applied)

- 9., Nussdorfer Straße, correct: 9., Nussdorfer Straße (in 1999 the application of the spelling reform to Viennese street names was decided.)

The labeling of the street naming boards is based on the principles of the Vienna Nomenclature Commission . The enamel panels are made by the Ybbsitzer company Riess . Missing street naming boards can be announced by anyone using the City of Vienna's online form on its website, whereupon the installation is usually arranged.

Additional boards

Even before the First World War, people wanted to know who this street or square was named after, and so the local council decided to provide information about this by means of additional boards. However, the money was missing, as was the case in 1926. When in 1956 part of the Ringstrasse was named after Karl Renner , a prototype of such additional boards was installed.

It was not until 1993 that this idea was implemented on a broader basis. Mayor Helmut Zilk disclosed on September 16, to the strains of the Gardemusik in the second district , the first three additional panels (Kafka, Mach and Engerthstraße). Today more than 400 signs explain the origin of the respective street names.

House numbers

The first numbering of houses was carried out in 1566 as a result of so-called Hofquartierspflicht under Ferdinand I was introduced.

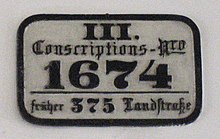

With the patent dated March 10, 1770, the houses in Vienna were numbered using conscription numbers for the first time. These should facilitate mail delivery and recruitment by the military . The numbers were consecutively painted on the house facades for the whole city, not sorted by street, and therefore soon faded. On February 4, 1782 the affixing of the street name was also ordered, which was applied with black paint.

The system of conscription numbers quickly became confusing, especially due to new buildings, so the city was renumbered in 1795 and 1821. There were also changes in individual suburbs ( five times in Gumpendorf ). Since 1842 the name of the suburb has been added to the street name.

The incorporation of the suburbs in 1850 would have required the continuous renumbering with numbers up to over 10,000 according to the rules in force at the time. The Imperial Ordinance with the provision for the censuses to be carried out on March 23, 1857 therefore stipulated in Section 11: For large cities, numbering by lane can also take place. However, according to the regulation, the consecutive numbering within an alley was not intended according to the location of a residential building (or a piece of land reserved for a house), but according to the time the house number was assigned - a rule that is useless for orientation.

The Viennese city administration chose a more orientation-friendly numbering method in 1862, probably with the approval of the government: With a resolution of the municipal council of May 2, 1862, the entrepreneur Michael Winkler (born July 17, 1822 in Místek ; † April 20, 1898 in Vienna) was co-developed A system of street-by-lane reciprocal house numbering introduced, in which the radial streets away from the city center and the cross streets are numbered in ascending order in a clockwise direction, with the odd house numbers being assigned to the left side of the street. It is therefore sometimes referred to as the Winkler system of house numbers .

On October 24, 1958, the local council decided on the current uniform house numbering in the style of street lettering (blue boards, white writing). The regulation came into force on January 1, 1959.

The highest house number used is in the 23rd district on Breitenfurter Strasse: 603; Not too far away is number 558 on the other side of the street. On the city map, on this side of the street, there is another object directly at the city limits with number 564. Very high numbers were also required on Simmeringer Hauptstrasse in the 11th district: 501 and 336 (983 and 992 are a glass house and a forest away from the street), as well as on Linzer Strasse in the 14th district with the numbers 508 and 487, respectively .

Missing house number boards can be announced by anyone using the online form of the City of Vienna on its website, whereupon the affixing is usually arranged.

| District today |

former place / municipality | Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [Inner] city | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 2 | Leopoldstadt | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 2 | Hunter line | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | 1827 | |

| 3 | Country road | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | 1830 | |

| 3 | Erdberg | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 3 | Weißgerber | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 4th | Wieden | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | 1830 | |

| 4th | Schaumburgergrund | 1816 | ||||

| 4th | Hungelbrunn | 1773 | ||||

| 5 | Laurenzergrund | 1804 (1799) | ||||

| 5 | Matzleinsdorf | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 5 | Nikolsdorf | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 5 | Margareten | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 5 | Reinprechtsdorf | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 5 | Dog storm | 1773 | 1795 | 1816 (1812/13) | 1829 (1822/23) | |

| 6th | Laimgrube | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 6th | Windmill | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 6th | Mariahilf | 1773 | 1795 | 1830 | ||

| 6th | Magdalenengrund | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 6th | Gumpendorf | 1773 | 1795 | 1808 (1807) | 1821 | 1830 |

| 7th | Spittelberg | 1773 | ||||

| 7th | Ortisei below Guts | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 7th | Ortisei obern Guts | 1773 | ||||

| 7th | New building (Neustift) | 1789 (1786) | 1795 | 1808 (1807) | 1821 | |

| 7th | (Ober-Neustift - Neu-) Schottenfeld | 1789 (1786) | 1808 | 1828 | ||

| 8th | Josefstadt | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | -1827 | |

| 8/7 | Altlerchenfeld | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 8th | Strozzigrund | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 8/9 | Alservorstadt | 1773 | 1795 | 1821 | ||

| 8th | Breitenfeld | 1812 (1802) | 1821 | |||

| 9 | Michelbeur. reason | 1795/96? (1773) | 1821 | |||

| 9 | Rossau | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 9 | Thury | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 9 | Himmelpfortgrund | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 9 | Liechtental | 1773 | 1795 | |||

| 9 | Althann | 1773 | ||||

The first numbering took place from 1771, but house directories did not appear until 1773.

Sources:

1) Rudolf Geyer : Handbuch der Wiener Matriken - An aid organization for registry guides and family researchers , 1929

2) Different numbers in brackets: Felix Czeike : Historisches Lexikon Wien , 1992-2004

Road surface

Unpaved roads were the norm up until the Middle Ages, the earlier Roman military roads had fallen into disrepair. However, completely unpaved roads are not practical in cities, not least because they are dusty in dry conditions and muddy in heavy rain.

gravel

A very simple form of paving the road was to cover it with gravel . A major disadvantage was that a lot of dust was raised when the weather was dry, which was harmful to the health of the citizens. As a remedy, important streets in Vienna were sprayed with water. For example, in Ober-St.-Veit in the 13th district in 1915, the streets were moistened twice a day using spray trucks or hose carts, and the main streets even three times.

macadam

An improvement on the gravel road was the macadam road. With this type of construction, three layers, each with broken and well-compacted aggregates of different sizes, formed the road surface . The structure consisted of three layers of gravel of different grain size, which were applied to a curved base, with lateral trenches for drainage . The lower two layers consisted of crushed stone (with a grain size of up to 8 cm) in a total thickness of 20 cm, on top of which a layer of chippings 2.5 cm grain size was applied in a thickness of 5 cm. The layers were compacted individually with a heavy roller and with the addition of water. Although this method was very labor-intensive, it produced a firm and self-draining road surface. This construction method was developed at the beginning of the 19th century by the Scottish inventor John Loudon McAdam ; the corruption of his family name led to the designation "macadam".

With the advent of automobiles, macadam roads gradually disappeared. The negative pressure under fast-moving vehicles sucked the dust and fine sand particles out of the surface, which meant that the coarser particles also lost their connection. There were also unpleasant clouds of dust.

paving

Paving a road with stones leads to a stable and dust-free surface. Paris was the first European city to be paved in 1185, followed by large Italian cities in the 13th century. The first street paving in German-speaking countries was laid in Nuremberg in the early 15th century , followed by Regensburg and Augsburg .

During the construction of an underground car park in Vienna, some medieval paving stones were excavated on the Freyung ; the stones were laid on the surface in front of the Palais Harrach after they were found. At that time, however, there was no continuous paving of the city. The first regular paving of streets in Vienna is assumed to be in the 17th century, evidence of paved squares is from 1725 and of paved roads from 1765. In 1778, systematic paving began in today's Inner City and in the later suburbs in the 1820s. Not infrequently only the sidewalks were paved, while the roadways remained unpaved. In 1900 around half of the streets in the city were still unpaved; In 1938 it was still 40%.

The first cobbled streets in Vienna were laid out either with slabs of slate or with flysch sandstone, then from around 1900 with stones made of Mauthausner granite , a medium-grain stone with a predominantly blue-gray color. The enormous demand for paving stones that soon set in contributed to a flourishing of the Mauthausen stone industry ; the stones could also be conveniently delivered to Vienna by ship. Large barges were often used, which could transport up to 200 tons of stone.

The most important producer was the Anton Poschacher Granitwerke , which at times had 2,000 employees and was the largest granite-producing company in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy . At times up to 20 quarries were operated in the lower Mühlviertel at the same time, today there are eight. Later stones from the Bohemian mass were also used.

In 1872, a competitor emerged from the Wiener Aktiengesellschaft for road and bridge construction . The company ran into difficulties due to the stock market crash of 1873 and was taken over by Anton Poschacher in 1876 . Another competitor in the first half of the 20th century was the Wiener Städtische Granitwerke owned by the City of Vienna, which owned a quarry in Mauthausen .

Originally, the Viennese paving stones had different sizes. In 1826 the “Wiener Würfel” was introduced, the edge length of which was standardized at 18.5 cm and has been preserved to this day. The stones lie in a bed of sand. The city paving was also an important prerequisite for improving street cleaning, because the streets could be sprinkled with water and therefore cleaned thoroughly.

In Vienna there was also a special type of paving: on steep streets, square stones with a scratch in the middle were laid across the direction of travel to give the horses a better grip. This Viennese horse plaster was popularly called "scratched". At the Wolfrathplatz in Hietzing and in the Auwinkel in the inner city there is still an original covering with “scratches”, which in Hietzing is also a listed building . As a further, modern special form, concrete paving stones are occasionally laid.

Paved streets had a number of disadvantages. Driving with carts was bumpy and produced a lot of noise, so it was not uncommon for straw to be piled up in front of hospitals, aristocratic palaces or official buildings in order to dampen the noise. The steel tires of the carts and the hoofbeats of the horses quickly wore off the surface. The wear and tear could be repaired quickly and cheaply: Since the paving stones are cubes with six faces, worn stones can be pulled out, turned and then put back in place. In this way, each paving stone can be used six times, which is still done today.

Cobblestone streets were - and are - built and maintained by pavers . This is an apprenticeship that takes three years to complete. In Vienna there is a school for pavers in the vocational school for the building trade (BS Bau), 22., Wagramer Straße 65.

asphalt

Alternatives to granite stone have been tried again and again, for example pavement made of cement, rubber or wood, but this has not proven itself. It was not until the 1830s that roads in Lyon and Paris were paved with asphalt , which led to satisfactory results. Asphalt is a mixture of sand and grit , combined with bitumen as a binding agent .

In Vienna, experiments with asphalt began in 1872, and asphalt pavements were used for some sidewalks from 1894. From 1922, streets were also paved, but in 1938 only 3.2% of Vienna's streets had this surface. Asphalt roads were easy to make, but were initially found to be disadvantageous because they were slippery, especially when wet, for shod horses. That changed after the automobile became more widespread. Now the smooth surface was an advantage, and in the decades that followed, most of Vienna's streets were paved. In many places, the high-quality paving was not removed at all, but simply a layer of asphalt laid over it.

tar

Tar is a viscous mixture of organic compounds that is obtained by thermal treatment of organic natural substances ( pyrolysis ). The Swiss doctor Ernest Guglielminetti worked in Monaco around 1900 and found there that the dusty streets were a health hazard. As a result, he developed a method of using tar as a road surface. With the support of the Prince of Monaco, Albert I , numerous roads in the principality were tarred from 1902.

The building contractor Hans Felsinger found out about this construction method the following year, and in August 1903 the first road in Vienna was paved. In the following decades, tar was used occasionally, but could not prevail over the more robust asphalt.

In the second half of the 20th century, it was recognized that tar is harmful to health. Its use in road construction was banned in West Germany in 1984 , in the GDR in 1990, in Switzerland in 1991 and around this time also in Austria.

New developments

In recent years, asphalt roads have been dismantled and stone surfaces have renaissance, especially in pedestrian zones and meeting areas . The asphalt pavement, which is suitable for cars and bicycles, is increasingly perceived as unattractive in these zones, while attractively designed paving can increase the quality of stay. For example, during the restoration of its pedestrian zone in 2008–2009, Kärntner Strasse was covered with Waldviertel granite in various shades of gray, as was Mariahilfer Strasse in 2014 .

While asphalt pavements seal the ground, paved roads are permeable to water and air. When it rains, the runoff speed of the surface water is lower. In addition, the production of paving stones is ecologically more favorable than the production of bitumen from petroleum.

Paved roads are more expensive to manufacture than asphalt, but not over the life of the road. Granite paving stones are almost indestructible, while asphalt roads have to be repaired over and over again.

Contrary to the trend, Höhenstraße is the longest street in Vienna at 14.8 kilometers. It was built in 1934–1938 with millions of small paving stones to provide employment . After 80 years, renovation is now required. The stones could be turned five more times, so that the road would have a theoretical service life of around 400 years. However, the city administration would like to asphalt most of the high road; the relevant discourse is currently (2016) still ongoing.

bridges

See Vienna Danube Bridges , List of Danube Canal Bridges and Vienna Vienna River Bridges .

In Vienna, like the streets, bridges were mainly named after topographical terms (e.g. Augarten Bridge over the Danube Canal, Schönbrunn Bridge over the Vienna River). There were also names of monarchs and nobility (e.g. Kronprinz-Rudolf-Brücke over the Danube, Ferdinandsbrücke and Franzensbrücke over the Danube Canal, Lobkowitzbrücke, Rudolfsbrücke, Leopoldsbrücke, Elisabethbrücke and Radetzkybrücke over the Vienna River). After the end of the monarchy in 1918, many aristocratic names were replaced. Around 1900, bridges began to be named after deserving personalities on the Wien River.

Traffic lights

In 1926 the first traffic light in Vienna was installed at the opera intersection in the 1st district and in 1951 the first traffic light for pedestrians was installed on Stock-im-Eisen-Platz in the 1st district. In 1956, the intersection of Argentinierstrasse and Gußhausstrasse (new spelling: Gusshausstrasse) in the 4th district was equipped with Vienna's first automatic traffic light system. In 1959, green flashing was introduced at the end of the green phase. 1962 ten traffic lights in the area Schottentor were merged with the Vienna traffic control center and in May 2007 in Vienna's 9th district , Alsergrund , the first digital at the intersection Währingergürtel / Nussdorferstraße red light monitoring system of Vienna put into regular operation.

literature

- Franz Pascher (Ed.): Official Vienna Street Directory , Pichler Verlag, 19th, updated edition. Vienna – Graz – Klagenfurt, 2007. ISBN 978-3-85431-437-0

- Peter Autengruber : Lexicon of Viennese street names. , Pichler Verlag, 6th edition 2007, ISBN 978-3-85431-439-4 .

- Peter Autengruber: Street names in Vienna with special consideration of names with a geographical reference. , Communications from the Austrian Geogr. Society , 155, Vienna 2013, pp. 263–290.

- Peter Simbrunner: Vienna street names from A – Z , 1988, ISBN 3-8000-3300-3 .

- Peter Csendes, Wolfgang Mayer: The Vienna Street Names , 1987.

- Anton Behsel: Directory of everyone in the Kaiser. royal Capital and residential city of Vienna with its suburbs, with precise details of the older, middle and newest numbering, the current owners and signs, the streets and squares, the principal authorities, then the police and parish districts , Carl Gerold, Vienna 1829 .

- Birgit Nemec: Renaming of streets in Vienna as media of politics of the past . Diploma thesis University of Vienna, Vienna 2008 ( online version )

- Friedrich Umlauft: Name book of the city of Vienna , A. Hartleben, Vienna-Pest-Leipzig 1895 ( online in the Google book search USA )

- Friedrich Umlauft: Name book of the streets and squares of Vienna , A. Hartleben, Vienna-Leipzig 1905 ( archive.org or online in the Google book search USA )

Historical street directories available online

(Google Books PDF files are searchable online only.)

- 1563–1587 - Association for the History of the City of Vienna: Reports and communications from the Alterthums-Verein zu Wien, Volume 10 , Prandel and Meyer, Vienna 1866

p. 97, Ernst Brik: “Materials on the Topography of the City of Vienna. Directory of all houses in the inner city of Vienna and their owners in the years 1563 to 1587 "( online version ) - 1566–1822 Albert Camesina Ritter v. San Vittore (author), Karl Weiss (editor), municipal council of the kais. Imperial capital and residence city Vienna (Ed.): Documentary contributions to the history of Vienna in the XVI. Century by Albert Camesina Ritter v. San Vittore , Alfred Hölder, Vienna 1881

p. 1 Houses, streets and squares in the inner city in 1566. According to the Hofquartierbuch ( n21 - Internet Archive or online in the Google Book Search USA ) - 1794 - Current state of the imperial and royal royal seat of Vienna , Johann Georg Edlen von Mößle, Vienna 1794 ( online version ) (More than a street directory, but contains a lot of information about it, only the inner city)

- 1809 - Johann Pezzl: Description and floor plan of the capital and residential city of Vienna: Sammt's short history , Degenschen, Vienna 1809,

p. 487 "Register of squares, streets and alleys in the city / in the suburbs [with number of houses]" ( Online version ) - 1816 - Johann Pezzl: Description of the capital and residence city of Vienna. 4th edition , C. Kaulfuss and C. Armbruster, Vienna 1816,

p. 402 "Register of squares, streets and alleys in the city / in the suburbs [with number of houses]" ( online version ) - 1825 - Joseph von Hormayr: Vienna, its fortunes and memorabilia. 2nd year, 3rd volume or 2nd year, 4th volume, 1st issue , Härter, Vienna 1825,

p. 112 “Overview of the streets, alleys and squares of Vienna, both the inner city and the suburbs [with number of Houses and house numbers] "( online version ) - 1840 - Joseph Salomon (Hrsg.): Austria: Österreichischer Universal-Kalender. 1841 , Ignaz Klang, Vienna 1840,

p. 45 “List of names of streets, alleys and squares in the city of Vienna and its suburbs”; P. 48 "House and street scheme of the residential city of Vienna & suburbs" ( online version ) - 1851 - A. Adolf Schmidl : One week in Vienna: Reliable and time-saving guide through the imperial city a. their closest surroundings. 3rd edition , C. Gerold, Vienna 1850/1851,

p. 91 "Directory of house numbers in the city and the suburbs according to the streets" ( online version ) - 1852 - The newest, most complete and time-saving tourist guide in Vienna and its surroundings , Alb. A. Wenedikt, Vienna 1852,

p. 86: "Directory of house numbers in the city and the suburbs after the alleys" ( online version ) - 1891 - The newest plan and guide of Vienna and environs , Lechner, Wien 1891,

p. 85 "Index of the Streets, Roads and Squares of Vienna with denotation of the District and their Situation" [& suburbs, the plan is almost unusable, the line wall is hinted at through the district boundaries] ( 85 - Internet Archive ) - 1900 - The newest plan and guide of Vienna and environs , Lechner, Wien 1900,

p. 139 "List of Streets" [with district, the plan is almost unusable] ( 139 - Internet Archive ) - 1859–1942: The Vienna City Hall Library makes all editions of Lehmann's Allgemeine Wiener Wohnungs-Anzeiger available electronically under the name Lehmann Online . The editions each contain a complete street directory for the entire city area.

- various house schemes and street directories in the online archive of the Vienna library

More historical street directories

- Friedrich Umlauft: Name book of the city of Vienna . Vienna, 1895. Semi-official and at the same time the first street directory of Vienna.

- Friedrich Umlauft: Name book of the streets and places in Vienna . Vienna, 1905. New edition from 1895 with an improved title.

Web links

- Streets of Vienna on wien.at

- "Public Safety" - In memory of ... (PDF; 315 kB)

- Say.at - The history of house numbers in Vienna

- Gallery of house numbers

- Special: Execute query / street names in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

Individual evidence

- ↑ Figures and facts on the Vienna road network. Vienna City Administration, accessed on February 8, 2014 .

- ↑ The provisional municipal law of March 6, 1850 with its supplementary provisions [until November 6, 1866] in: Report of the commission appointed by the Vienna Municipal Council to revise the municipal statute. First volume. = Templates for the revision of the provisional Viennese municipal regulations from March 6, 1850 , self-published by the Vienna Municipal Council, Vienna 1868, pp. 141, 173, 174 ( online version at Google Books)

- ↑ “Gender Atlas”: Few streets with women's names , report dated December 8, 2015 on the ORF website

-

^ Vienna address book. Lehmann's apartment indicator . 1st volume. August Scherl successor, Vienna 1939, street renaming, p. 1508 ( digital.wienbibliothek.at [accessed on January 25, 2016]). Vienna address book. Lehmann's apartment indicator . 2nd volume. August Scherl successor, Vienna 1940, street renaming, p.

XVI ( digital.wienbibliothek.at [accessed on January 25, 2016] no increase). - ↑ Municipal Council, 44th meeting on December 17, 1999, meeting report, p. 5, at www.wien.at

- ↑ Historians' report on Vienna's street names on the Vienna city administration website

- ↑ News from September 24, 2014 on the website of ORF Vienna

- ↑ wien.gv.at - possibility to report missing street naming boards

- ↑ Imperial ordinance of March 23, 1857, effective for all crown lands, with the exception of the military frontiers, with the provision for carrying out censuses , RGBl. No. 67/1857 (= p. 167)

- ↑ Anton Tantner: to correct birth and death of Michael Winkler 28 June, 2006

-

↑ Resolution of the Vienna City Council of October 14, 1958 on the uniform numbering of buildings (MD 4409/58; PDF; 53 kB), Official Gazette of the City of Vienna, No. 100, December 13, 1958, p. 11

Legal regulation B 20-080 (PDF; 36 kB), Version: March 18, 2008 - ↑ Anton Tantner: Breitenfurterstraße 603 - the highest number in Vienna. In: Adresscomptoir. July 25, 2012, accessed February 23, 2015 .

- ↑ wien.gv.at - possibility to report missing orientation number boards

- ↑ Pavement in the Vienna History Wiki of the City of Vienna

- ↑ Andea Hauer : Heavy stones - the neglected art of street paving. Radio OE1, broadcast on May 19, 2016

- ↑ The history of street paving at www.1133.at, accessed on June 2, 2016

- ↑ Tar coating at www.felsinger.at, accessed on June 13, 2016

- ↑ Asphalt in cycle path construction , s. 3., https://www.asphalt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/dav/asphalt_im_radwegebau_februar_2015.pdf , accessed on May 3, 2019

- ^ Wien.gv.at: History of the traffic lights in Vienna ; accessed on January 28, 2017

- ↑ ORF -Online: First digital traffic light monitoring in operation ; accessed on January 28, 2017

- ↑ ORF -Online: 1,900 ads on traffic light radar ; accessed on January 28, 2017

- ^ Official Viennese street directory , 1st edition. Vienna 1950.

- ^ A b c Reference: Foreword, Official Vienna Street Directory , Pichler Verlag, 15th, updated edition. Vienna, 1997. ISBN 3-85058-143-8