Jewish life in Vienna

Jewish life in Vienna has existed since the 12th century , which makes Vienna one of the oldest Jewish settlements and the oldest Jewish community in Austria today . Jewish life here was subject to very strong fluctuations, among which the Holocaust of the National Socialist regime (1938 to 1945) stood out negatively. The development is presented here chronologically for the time being.

From a few occasional mentions, in the 13th century a flourishing community emerged with its own Jewish quarter with a synagogue , a hospital , a cemetery and other functional buildings. Important and famous scholars worked as rabbis in the community and thus Jewish Vienna radiated its importance in a supraregional way and played a role in the cultural, intellectual and economic life of the medieval city that should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, the history of the Jews of Vienna is marked by persecution and expulsions ; they were 1420 / 21 on the orders of Albert the V. persecuted cruelly and again in 1670 / 71 by Leopold I. expelled. Up until then there were two Jewish quarters in Vienna, a medieval one in today's 1st district (on Judenplatz ) and a larger one from the 17th century on Unteren Werd in Leopoldstadt .

In the 17th and 18th centuries, there were isolated settlements by privileged Jews. Well-known court Jews such as Samuel Oppenheimer or Samson Wertheimer worked in Vienna during the age of absolutism and financed numerous undertakings and projects of the rulers. With the spirit of the Enlightenment and the Haskala began the legal and social equality of the Jews. The emancipation of the Jews into the middle of society in Austria began with the Edict of Tolerance by Joseph II and reached its climax with the December constitution of 1867 under Emperor Franz Joseph I. With this, complete equality for the Jews was achieved, and a heyday soon began of the Jewish communities throughout the monarchy.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, Vienna was one of the great centers of Jewish culture and life in Europe . The city's cultural heyday during the fin de siècle was significantly influenced by the city's Jews. Jewish intellectuals such as Victor Adler , Otto Bauer , Hugo Breitner , Robert Danneberg , Julius Deutsch and Julius Tandler were involved in social democracy for an egalitarian society in which there should also be no room for anti-Semitic prejudices.

Scientists and doctors of Jewish origin brought the medical schools and universities much recognition, among them Emil Zuckerkandl , Josef Breuer , Carl Sternberg , Adam Politzer , Viktor Frankl , Alfred Adler and Sigmund Freud . Numerous Nobel Prize winners appear from the community ( Wolfgang Pauli , Max Perutz , Otto Loewi or Robert Bárány ), but also in music ( Gustav Mahler , Arnold Schönberg , Erich Korngold and Alexander Zemlinsky ...), the press and in literary circles the Jews performed Vienna's contribution. Well-known authors are Arthur Schnitzler , Hermann Bahr , Hugo von Hofmannsthal , Richard Beer-Hofmann , Karl Kraus , Franz Werfel , Stefan Zweig , Franz Kafka and Friedrich Torberg .

At the time of National Socialism in Austria all synagogues and rooms, except one , were destroyed and the Jewish population of the city of Vienna was almost completely expelled or murdered in the Shoah . The almost complete destruction of the community meant the decline of the cultural heyday of Jewish Vienna. Almost 200,000 Jews lived in Vienna in 1938; today there are fewer than 10,000.

After 1945 there was a slight resurgence of Jewish culture and existence in Vienna, and there are still enough indications to what extent the Jewish community shaped the cityscape and to what extent it was decisive for the development of the city. The Orthodox community has built up a large community life for its relative smallness. In addition to the dozen of synagogues and rooms, there are kosher restaurants, shops, butcher shops, Jewish schools and kindergartens, as well as sports clubs, a help center and an old people's home. In Vienna there is also a reform community , Or Chadasch, which runs its own synagogue, as well as ultra-orthodox Jews who live in the 2nd district . As in the 19th and 20th centuries, most of Jewish life can be found in Leopoldstadt.

history

middle Ages

Unclear beginnings and situation in the Duchy of Austria

( See → Raffelstetten customs regulations )

Little is known about the presence of Jews in the early Middle Ages, apart from legends about fairytale kingdoms of Jews which were founded by Jews and ruled over cities such as Tulln , Vienna, Korneuburg or Stockerau , there are no meaningful sources or documents. The first documentary mention of Jews in the area of today's Austria comes from the years 903 and 906. A customs order from Raffelstetten regulated a number of provisions on duties for the movement of goods and one of the last provisions stated that Jews pay certain customs duties for slaves or other goods would have to. So Jews were already active as traders in the 10th century, probably already under Carolingian rule , and came through today's Austrian areas. Unfortunately, the customs regulations do not reveal any other information, neither whether Jews had been resident in Austria for some time, nor who exactly they were.

In the Privilegium Maius , a forgery of a document by Friedrich I. Barbarossa for the Dukes of Austria from September 17, 1156, Jews are mentioned again:

".., et potest in terris suis omnibus tenere judaeos et usurarios publicos quod vulgus vocat Gawertschin sine imperii molestia et offsa."

In German:

"... And can he, the Duke of Austria, keep Jews and public usurers, whom the people call Gawertschin, in all his countries without damaging or offending the empire."

The content of the privilege was reused and confirmed by many rulers (including emperors ). It was therefore considered a role model and example for the early legislation in medieval German-speaking countries.

First mentions in Vienna

The existence of Jews in Vienna can be proven with the first known Jew, Schlom or Schlomo , since 1194. In a dispute over the ownership rights to a vineyard between him and the Bavarian monastery Formbach (presumably today's Vornbach ), his name appeared. The disagreement between him and the monastery lasted for several years, until Leopold V's death, when the successor, Friedrich I , awarded the garden to the monastery if the latter undertook to pay compensation to Schlomo. However, Schlomo made a name for himself not only as the first documented Jew in Vienna, but also because of his exceptional legal position. He was allowed to own land and place Christians under his service - rights that ordinary Jews were denied at that time. But he was the ducal mint master and, because of his high social position, belonged to the close circle of the court of the two dukes Friedrich I and Leopold V.

Schlomo probably lived on his four properties in the area of today's Seitenstettengasse (today there is a synagogue in the street). During this period he and his family must have made up the entirety of the Jews of Vienna. Although he and his household were under ducal protection, they were in an endangered situation, as is evident not least from the year 1196 . That year one of Shlomo's servants was sent to prison. He had committed theft and would therefore serve his sentence as a thief. However, the servant joined the crusade before the events . The arrest of the alleged crusader by a Jew led to a violent response from the crusaders. He and 15 other members of his household were slain and murdered by a group of crusaders. Such an act of violence made Duke Friedrich angry; he had two crusaders executed. Such a punishment was severe for the time. In other parts of the empire there were similar massacres and violence against Jews, but the perpetrators mostly got away without criminal prosecution.

The Jew Ephraim bar Jakob reports in his memorandum about the murder of the former ducal mint master Schlomo and 15 other Jews. The translation is like this:

“A man named Schlomo lived in Austria; he was flawless, upright, and godly, always charitable and loving to the poor. The Duke [Leopold V.] hired him for the customs duties and his [financial] needs, and he had male and female servants, both non-Jewish and Jewish. And it happened in Tammuz of the year [4] 956, in the 256th lunar cycle, in which we hoped for jubilation and joy, but which turned into sadness; because also in this year countless hairy (Christians) described themselves as despicable (crusaders) in order to move to Jerusalem and fight against the savages. Then one of his servants, who had also shown himself to be disgusted, came and stole 24 marks from his money, and Shlomo had him put in prison for this. Then the wife of the incarcerated despicable man went hastily [?] To the house of her idolatry (church) on one of her bad holidays and complained about the fact that her husband was imprisoned by the hand of a Jew. Then the despicable who were in the city rose up and went out in a violent anger and came to the house of the righteous and killed him and about 15 Jews with him. The Duke [Frederick I] later learned what had happened and ordered two of the leaders of those murderers to be captured and beheaded; he did not want to kill any more of them because they were despicable. - See, Lord, our misery and take vengeance for Israel ”

The next Jew appeared in a charter in 1225 and was known as "Teka". His name appears in the peace treaty between Leopold VI. and King Andrew of Hungary as guarantor of the latter. He owned a house in Vienna and enjoyed a reputation not only at the Austrian court, but also in the Hungarian Empire. Schlomo and Teka are both prominent exceptional cases, as no other Jews are mentioned by name during these periods.

In the privilege of 1238, Frederick II regulated the legal status of the Jews of Vienna. In terms of content, the privilege was similar to that of 1236, which Emperor Friedrich had bestowed on fellow believers throughout the empire. The provisions are divided into those of a public, private, criminal and procedural nature. The Jews were protected from forced baptism and given free trade rights, and Christians had to pay 12 pounds of gold to the imperial chamber in the event that a Jew was killed, if they were involved. But the privilege never really came into effect. Instead, Jews were officially excluded from public office in the Letter of Freedom for Vienna of July 1, 1244, and a new privilege was granted on the same day. This Jewish legislation remained in force until the Vienna Gesera and was also used as an example for neighboring countries.

Two basic ideas can be drawn from this regulation. First, Jews lost their membership in the imperial chamber property and became ducal property. Second, the basis of Jewish business life was changed, because the Jews in Vienna, as everywhere, were "expelled" from the trade in goods and increasingly forced into the money trade. For example, 22 of the 30 articles of the privilege relate to questions of lien and criminal law.

First ghetto and the beginning of the community in the 13th century

It is not known whether there was a community during or immediately after the murder of Schlom around 1196, as the sources did not name a single Jew until Teka was mentioned in 1225. Nonetheless, there was probably a congregation, since Isaac ben Mose had been a rabbi in Vienna for several years in the first half of the 13th century . The community consisted of newcomers from all over the Duchy of Austria, Carinthia, Styria, Salzburg and Hungary. Many also came from Bohemia and Moravia, as Slavic women's names were very common among the Jewish women of the community. In addition, a synagogue and a Jewish school in Vienna were first mentioned in documents in 1204 .

Isaac ben Mose also originally came from Bohemia, but he was called Isac from Vienna or, after one of his works, Or Sarua (English: light seeds ) and was considered one of the greatest scholars in medieval Europe. He studied in Meissen and Paris with Rabbi Judah the Pious and conducted extensive correspondence. One of his students was the famous rabbi and Talmud scholar Meir von Rothenburg .

From around 1200, the Jews settled today's Judenplatz as the “Vienna Jewish City”. The ghetto was arranged in a space between Maria am Gestade , the Carmelite Church at that time, between the Tiefen Graben and the Tuchlauben fairly regularly around the school yard surrounded by houses. From there an alley led to Wipplingerstrasse, where there were gates at both ends that could be closed and bolted. The entire quarter was walled, either by the houses of the Jews themselves or by added walls.

The community

A Jewish community represented a community in the township itself and was provided with a certain legal autonomy, comparable to the guilds of the cities, which were also granted certain autonomies and certain tasks. The main tasks of the community consisted of representing the Jews externally, i.e. vis-à-vis the Christian world and tax collection, above all in internal organizational tasks of a religious or secular nature. This included the care for law and order according to halachic laws, the rabbinical court Beth Din mainly dealt with problems relating to marriage and inheritance law or questions of living together. The protection of the honor of the community members, but also the administration of the community property as well as social tasks (Zedaka), i.e. the provision of a social safety net that benefited the poor without sufficient tax base, the poor students, but also travelers, were among the tasks of the community . Each congregation member regularly had a certain amount, calculated based on the amount of property, to deliver to the congregation, plus fines and penalties and voluntary donations as potential income.

The existence of a certain infrastructure was to be seen as a prerequisite for the existence of a community (synagogue, rabbi, cemetery, mikveh ). The synagogue has always been the geographical and symbolic center of a community . In addition to its religious functions, the synagogue was a place of internal Jewish jurisdiction, a place of announcements, also of stately measures, but also of the settlement of Christian-Jewish disputes. From the 13th to the 15th century, the quarter was home to the synagogue (first mentioned in 1204, see → medieval synagogue of Vienna ), the only stone building among the private and community houses after the fire of 1406, the hospital (now the house of the tailors' cooperative am Judenplatz), at the bottom of the community garden (now the Collaltopalais ) and the bath house , a cemetery a little outside of their residential area (as stipulated by Jewish law, today in the Goethegasse and Opernring 10 area) and a butcher's shop .

The Vienna city law provided for a Jewish judge for disputes between Christians and Jews . He was not responsible for conflicts between Jews unless one of the parties brought an action against him.

The rabbi was responsible for religious leadership. Until the 14th century there was no information about the rabbis of the community. From 1318 to 1337 Rabbi Nissim Guetman was a rabbi. a .: Moses ben Gamliel, Meir ben Baruch Halewi (1393 to 1408), Awraham Klausner (1399 to 1407) and his sons Rabbi Jonah and Rabbi Jekl.

Because of its important and well-known donors, the community was not only noticed in documents but also among the aristocrats on a supraregional level. Important donors were the sons of a black girl (Azriel). Schwärzlein came to Vienna from Moravia and was a financier himself, he died around 1305, but his sons could easily surpass his weak business activity. The most important was Isaac, he was in the service of Queen Elizabeth, wife of Albrecht I, and from 1292 to 1314. The oldest was Mosche and first appeared in 1309. Referred to as Marquard, Mordechai appeared in a document from 1305, he moved from Vienna to Zistersdorf , probably for business reasons. The fourth son was called Pessach and, together with his brothers, had various noble families as borrowers and even had business relationships with the monastery in Kremsmünster .

In 1295 a certain Lebman (Marlevi Ha-Kohen) appeared and was possibly the community leader. He maintained economic ties with a number of noble families. The noble Kaloch von Ebersdorf took out a loan from Lebman in order to expand his property. To cover the costs, he pledged his newly acquired treasury office for 800 pounds Viennese pfenning . This office held jurisdiction over the Duke's Jews, and Lebman was given the right to hold the income from the chamber as pledge; a very remarkable pledge that made Lebman's important position clear.

Another important Jewish businessman was David Steuss ; his debtors included both the dukes Rudolf IV . and Albrecht III. as well as the bishops of Brixen , Gurk and Regensburg as well as other nobles in Austria. His possessions included twelve houses in the ghetto and others outside Vienna. He and his family received special privileges. But his importance didn't exactly make him popular. So Albrecht III. lock him up until he paid the duke about £ 50,000. Such extortions, special levies and the cancellation of debts were followed by the decline of the Jewish economy towards the end of the 14th century.

Jewish book of Scheffstrasse

Thanks to a land register , which was kept from 1389 to 1420, life in the community is described by names and sums of transactions, comments, etc. The Jewish book on Scheffstrasse in Vienna was a sentence book. Depending on whether the believer was a Christian or a Jew, he was entered in the Christian or Jewish book. The book of Jews consists of 229 pages, 337 businesses are listed. The first entry comes from a S. (Salomon? Samuel?) Jakov and was written on a Tuesday, July 27, 1389. Well-known names appear like Rabbi Meir ben Baruch HaLevi (entry April 23, 1403), Rabbi Avraham Klausner (appears in the book from 1399 to 1407) or Lesir, made famous by a depiction. He was not a rabbi because he was called master of the Jews, Lesir was probably a synagogue servant .

There also appear cantors on how Smaerlein the Sangmeister, community servant as Eisak the Kalsmeschures, or the family of the wealthy David Steuss, who had three sons, Jacob and Jonah Hendlein. Apparently Scheffstrasse was not in the interests of the richer Jews, because Jona is only mentioned twice. It was similar with the family of Patusch von Perchtoldsdorf . He himself is only mentioned as an uncle, father-in-law or father of his descendants, who also did not place any particular value on the business life of Scheffstrasse.

The legal position of the Jews

The Jewish law is understood to mean the entirety of the regulations that were issued to the Jewish population by the emperor or the sovereign. The granting of such rights was originally exclusively the responsibility of the emperor ( Judenregal ), who also took over the subordination of the Jews to his patronage, i.e. his authority. In the course of the development of territorial domains within the framework of the feudal system , this protection of Jews was often passed on to the respective sovereigns. The term chamber servants is derived from this direct subordination of the Jews to the respective authorities. A Jew thus became part of the ruler's chamber property , that is to say, more or less the private property of the emperor or the sovereign. In the Middle Ages, a variety of laws, i.e. the parallel existence of several independent legal systems, was common, so that life under one legal status was not a special situation for Jews. In addition to Jews, this also applies to the clergy , craftsmen and university members.

In the Duchy of Austria , the rapid emergence of Jewish settlements in the first half of the 13th century made it necessary to regulate the legal status of this population group. In the course of the conflict between Friedrich II and the last Duke of Babenberg, Friedrich II, both claimed protection for Jews, not least in order to use it for themselves. The first regulations arise within the framework of the privilege for the city of Vienna from 1238. In this award of various rights, which the city received from Emperor Friedrich II as thanks for their support in his conflict against Friedrich II ( Babenberger ), the Jews of Vienna, among other things, were not allowed to exercise public offices. It is a provision that went back to church requests, namely to the IV Lateran Council. This regulation was aimed at a preferential treatment of the Viennese citizens, who were themselves interested in the lucrative court offices. The regulation was directed against the prominent head of the Jewish community rather than against the entirety of the Jews of Vienna.

The first essential Jewish ordinance was also issued in 1238 by Emperor Friedrich II, who mainly granted Viennese Jews economic rights. It was based on the privilege of Emperor Frederick I of 1157 for the Jews of Worms . However, some other provisions were also made, such as the term of the position of the emperor as supreme court lord, the handling of internal disputes before the head of the Jews mentioned here for the first time, and protective measures such as the prohibition of forced baptism .

The legal situation of all Austrian Jews was placed on a permanent basis six years later by Duke Friedrich II. With the enactment of his general Jewish order in 1244 , he not only created a legal basis for the Jews of Austria that was valid for a long time, but this privilege also had a strong model effect in numerous neighboring countries. This privilege offered a very comprehensive regulation of a number of areas of Jewish life, but above all in the economic field. In the pawn shop and money-lending business, Jews received extensive special rights and even ducal protection, because damage to Jewish property was equivalent to damage to ducal property, since Jews were now ducal property. Although a large part of the statutes formed economic provisions and thus changed the basis of Jewish business life (from trading in goods to money business), there are also numerous articles relating to general life.

For example, the murder of a Jew was punished with death, and the synagogues and cemeteries were placed under protection. The Jews were expressly excluded from the jurisdiction of the cities, i.e. from the jurisdiction of the city judge, and placed directly under the duke. Only the synagogue was set as the place of jurisdiction and the so-called Jewish judge was responsible for settling disputes between Jews and Christians. Furthermore, it was stipulated in the privilege under § 14 that a Christian should be sentenced to death and that his entire property should be confiscated if he devastated the Jewish cemetery:

"... item si christianus cimeterium Judeorum quacumque temeritate dissipaverit aut invaserit, in forma iudicii moriatur, et omnia sua proveniant camere ducis, quocumque nomine nuncupentur ..."

Since the Jews already owned a synagogue in Vienna at the beginning of the 13th century, it can be assumed that there was also a common cemetery at that time. Ottokar II. Premysl followed this path of friendlier Jewish policy and first confirmed the protection of the Jews from Pope Innocent IV , in 1255, 1262 and 1268 he renewed the statutes of Frederick II and made some changes. In 1255, for example, the ban on blood accusations recently issued by the Pope was included and in 1262 the interest rate of a maximum of 8 pfennigs per pound per week, which had been fixed since 1244, was released. The transfer of the dead is also discussed in the privilege of 1255. Paragraph 13 of the 1255 privilege states:

" Item whether the Jews after irr accustomed to death from instead of instead of or from opposite to opposite or from lant to lant, but whether in ain tolls nothing should be plagued as a robber".

This approval to transfer the corpses from place to place toll-free only says that the dead were transferred to a certain place or country.

In the course of the 14th century the legal security of the Jews deteriorated. An important means of power to give preference to aristocrats was the destruction of mortgage notes in which the duke, for the benefit of the aristocratic debtors, declared the debts to the Jewish moneylender to be " killed" , that is, to no longer exist. The main reason a sovereign prince was interested in the Jews was always to be seen in the financial area. The “Jewish tax” should also be mentioned to cover financial needs. Parallel to the legal regulations of secular rulers, since the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 at the latest, a number of anti-Jewish regulations or at least regulations aimed at separating the two population groups had repeatedly been demanded and confirmed by the church.

From the Vienna Provincial Council in 1267 to the end of the ghetto through the Vienna Gesera in 1421

The Crusades drastically changed the Church's attitude towards the Jews. After the IV Lateran Council in 1215, the church demanded social and societal separation. But while councils hostile to Jews were held in the western countries, the German-speaking countries followed only hesitantly. The Church complained that Jews still held important positions and did not live under strict rules. That is why Pope Clement II entrusted Cardinal Guido, a Cistercian , with the task of organizing anti-Jewish councils in 1265 . The cardinal's task was compared to that of the prophet Jeremiah : "to root and tear, to remove and to destroy, to build up and to plant (chap . 1.10)" . From 10 to 12 May 1267, the 22nd Provincial Council met under his supervision in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna. Among the many clergy there were 16 bishops, including John III. von Prag , Peter von Passau, Bruno von Brixen , Konrad von Freising , Leo von Regensburg and Amerlich von Lavant. The anti-Jewish regulations desired by the church were proposed and the social and spatial segregation of the Jews was demanded.

Jews now had to wear a Jewish hat , were not allowed to visit Christian bathhouses or taverns, keep Christian servants or use any public services. For sexual intercourse between a Jew and a Christian, for eating and drinking together, celebrating Jewish festivals or weddings, or for buying food from Jews, Christians were severely punished up to and including excommunication . In addition, Jews were not allowed to build new synagogues or to renew or increase or expand old ones. These provisions give an insight into the relations of the Jews with their Christian neighbors; apparently there was well-kept contact and social intercourse on a daily basis. Although these resolutions were not legal provisions, but rather guidelines for Jewish policy in the German-speaking East and North, they nevertheless marked a turning point in the history of the Jewish community and its relationship with its neighbors.

Also, the St. Stephen's Cathedral is still a witness to the centuries-long history of Christian anti-Judaism disparaged, the Jews, among others, as Christ-killers. In the giant gate on the left side of the frieze zone above the columns there is a head of a person with a pointed hat. The depiction of the Jew is depicted between dragons and lions and other magical beings.

Shortly before the inauguration of the new Gothic building of the choir aisles of St. Stephan ran out of funds for the construction. In order to get some money, the pastor requested a certificate of indulgence from the Pope, which was issued on November 5, 1339 by two archbishops and ten bishops. The documents were nailed to the gate and in order to encourage the population to donate, they promised those who would contribute to the construction that they would receive an indulgence from the penalties for sin. In the decorated and painted initials of the document, Jews are depicted with pointed hats throwing stones at the church patron Stephanus. Stephen was considered a martyr and is therefore dressed in red (as the color of blood) in the picture. From such examples it becomes clear that the hostility between Christians and Jews was not originally there, but was deliberately built into society by clergy.

During the reign of Albrecht II , he also protected the Jews from persecution and even restricted church property. The parish was spared the dreaded Pulkau persecution , while several other parishes were destroyed without Albrecht II being able to intervene. But when in 1349 at the plague , which in Europe was raging , Vienna in one day in 1200 died, the Jews were poisoning wells accused of a pogrom followed, although their community mourned many plague victims. Many Jews committed suicide in the synagogue, only a few survived, although Albrecht II tried to contain the riots. Nevertheless, Jews were soon living in Vienna again. On July 20, 1361, Duke Rudolf IV confirmed the Judicial Tribunal, which had to decide on internal Jewish affairs. At the head was a Christian who was primarily charged with collecting Jewish taxes and acting as an intermediary between Jews and the authorities.

Finally, in the Viennese Gesera (1420/21) under Albrecht V, the community was partly expelled because of the usual anti-Jewish accusations such as desecration of the host and partly died by fire on the Erdberg . But some committed in the synagogue to the Jewish suicide to the forced baptism to escape, and Rabbi Jonah put the synagogue on fire before he committed suicide. Survivors were scattered in the surrounding countries.

At the house "Zum Großer Jordan" ( Judenplatz ) there is still a vicious sculpture with anti-Semitic inscription, which was probably attached after the expulsion.

List of Jewish masters and rabbis in medieval Vienna

Source:

With the arrival of Isaac ben Mose in Vienna in the 13th century , the city became a center of Jewish Ashkenazi scholarship in Central Europe . Generations of leading rabbis followed into the Viennese rabbinical community.

- Solomon; after Or Sarua he was in contact with the rabbi of Bamberg Samuel ben Baruch (active around 1220).

- Izchak ben Moshe Or Sarua ; Born in Bohemia in 1180 , later worked in France and Germany with Elieser ben Joel (1140-1225) and Simcha bar Samuel. He came to Vienna around 1220 and died there in 1260.

- Avigdor bar Elijah HaKohen Zedek ; Born in Italy , studied with Simcha bar Samuel von Speyer and rabbi in Vienna from 1250, he wrote a commentary on Shi ha-Shirim and was a well-known Talmud scholar.

- Yehuda ben David; active from the second half of the 13th century.

- Chaim ben Machir; was born in the last quarter of the 13th century and worked in Munich , where he witnessed the pogrom of October 17, 1285 and immortalized it in a lament. In 1305 he appeared in Vienna as a rabbi.

- Moische bar Gamliel; he signed in 1338 as a community leader many Notes and interest lapel.

- Saadja Chaim bar Schneur; worked in Vienna after Moische Gamliel and also signed documents and interest reversals.

- Chaim Hadgim bar Eliezer; was also a community leader.

- Tanchum bar Avigdor ; also called Tennchlein was a rabbi and famous arbitrator in legal matters.

- Gerschon; was rabbi of Vienna at the end of the 14th century.

- Meir ben Baruch HaLevi; (1325-1406) also called Mayer von Erfurt, was rabbi in Erfurt and Worms and teacher of Hillel ben Schlomo, became rabbi of Vienna in 1397 and married the daughter of the rich David Steuss, Hansüß, he was probably also an imperial rabbi.

- Avraham ben Chaim Klausner ; worked in Vienna from 1399 and wrote glosses on the Minhagim by Chaim Paltiel.

- Jekel from Eger; studied at Schlom von Neustadt and had his own yeshiva from 1379, he came to Vienna in 1413 and is the son of Avraham Klausner.

- Jonah bar shalom; worked in the second half of the 15th century, he was a scholar and moneylender.

- Jonah, son of Avraham Klausner; Victim of the Viennese Gesera and protagonist of the Kiddush Ha-Schem.

- Little Master of Perchtoldsdorf; worked as a Jew master in Vienna from 1413 and died with his two sons during the Vienna Gesera.

Early modern age

In 1536 a new Jewish regulation was issued for the temporary residence of Jews in Vienna, in 1571 seven Jewish families lived there again. These families were subordinate to the court chamber and were allowed to live anywhere in the city. Under Rudolf II the number continued to grow, in 1601 there were already two synagogues in the city, from 1603 onwards with the headmaster Veit Munk.

In the 17th century two important events occurred for the Viennese Jews: the accession to the throne of Emperor Ferdinand II in 1619 and the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War . In 1624 Israel Wolf Auerbach was appointed director of the Vienna Mint Consortium and largely regulated the state finances during the Thirty Years' War. Although there was a settlement ban until 1624, numerous exceptions were approved, so that in 1582 the new Jewish cemetery Rossau could be built in Seegasse .

The ghetto at Unteren Werd 1624–1670

Ferdinand showed himself to be more tolerant of the Jews than his predecessors, and obligations in return were met. In the early years of the war, Jews acted as suppliers and financiers for the army. The emperor recognized their services and confirmed certain privileges, community autonomy and the construction of a synagogue . Only this did not happen according to the wishes of the other Viennese. Their protest reached the end of construction, but not the complete expulsion of the community. In addition, the non-Jewish Viennese merchants in a precarious position saw the Jews as business competition.

In order to reduce the conflicts, the emperor decided to have the Jews resettled in a peripheral ghetto - and not, as in the Middle Ages, in a centrally located medieval quarter. On June 10, 1624, Ferdinand II commissioned the President of the Court War Council , Count Rambold Collalto , to find a suitable location that would also offer them sufficient security. The choice fell on Untere Werd ( Werd = river island), which is connected to the city by a bridge , and is an area threatened by flooding. There was a property belonging to the citizens' hospital and a small fishing settlement with 14 houses that the Jews had to buy and surrounded by a wall themselves. With the move there, her community got a certain autonomy and protection, not only because of the ghetto walls, but also because of the privilege. The Jews were now under imperial protection and were subject to his jurisdiction, no longer that of the city of Vienna. In addition, they were exempted from the obligation to identify themselves in the city and were allowed to elect representatives of their community to the outside world (so-called "Jewish judges") themselves.

The flowering time of the church and the inner life

Around 1620 the parish council consisted of 16 members; The top was formed by five Jewish judges, followed by two jurors (Tow Ha-Kahal), six rabbinical assessors (they had to settle disputes in the board of directors and in the community) and finally three cashiers (Gabai Zedakah, primarily responsible for donations).

As early as 1625, the residential area on the Unteren Werd, which the Jews moved into, grew without any expansion of the area. Initially 15 houses became 31 by 1627, around 1652 there were 96, in 1660 already 111, and in 1669 there were 132 houses. As of July 26, 1669, there were 1,346 people in the district. However, it should be noted that this number refers to the people who left the city on the first expulsion date (see below ). There were probably still Jewish families in the ghetto after the first appointment, so that the total number of Jews at that time is estimated to be between 2000 and 3000.

The ghetto was square in shape. The Taborstrasse , the Augarten , the Schiffgasse and the current traffic areas Malzgasse and Krummbaumgasse formed the border of the quarter, which led back to Taborstrasse via the Carmelite Church . The first synagogue was called the “Old Synagogue” and was located in today's Große Pfarrgasse 12. The second synagogue was built in the middle of the 17th century. It was called the Klaussynagoge and was established by the wealthy Zacharis Mayr, who also founded a school and a Talmud school. The Jewish students were given the opportunity to study for free. The Torah curtain of the synagogue was donated by the wife of Moses Mirls ben Jakob Ha-Levi, i.e. Elkele asked Tanchum Master. After the Jews were expelled, the curtain was brought to Prague, where it is still exhibited in the Jewish Museum today. The church was on the site of today's Leopold Church (it was rebuilt immediately after the eviction). In 1660 a third synagogue was built.

Numerous hospitals were built. One was connected with the Klaussynagoge; In 1632 a hospital was built outside the ghetto, and because of an epidemic in 1666, another hospital had to be built near the cemetery area. The ritual bath was in what was then Badgasse.

The living conditions in the Jewish city were no more unhygienic than in other parts of the city; in contrast to other parts of the city, the “Holy Community of Vienna” ghetto also had a street cleaning facility. However, a house directory from 1660 shows that most houses were made of stone or wood and were single-story or single-storey. Several families had to live in one house, which often had only one kitchen, one room and a few chambers. But houses in suburbs or inner city districts were built in a similar way back then.

Around the middle of the 17th century, the Jewish community was in its heyday, it even had its own seal, which in Hebrew read Holy Community of Vienna . The first rabbi - Jomtow Lipman Heller, student of Rabbi Löw - was called from Prague. A well-known Jewish humanist, the doctor Leo Lucerna, lived in the ghetto. Many rabbis worked in the Jewish city, but only a few are known. Among them are Menachem Mendl Auerbach (Menachem Man ben Isak, active from 1639 to 1645 after his training in Vienna), Schabtai Scheftel Horwitz (Hebrew name: Schabtai Scheftel ben Jesaia Ha-Levi Horowitz, from 1655 until his death in 1660, he maintained a Talmud school ).

In 1660 there were three synagogues with their own schools, the Talmudic Klaus Zacharias Levis, hospitals and a parish hall, as well as other functional buildings. The community probably gained in religious prestige and charisma. Not only Schabtai Horwitz was a nationally known and famous scholar, but also his successor, Gerschon Ulif Aschkenasi , a student of Joel Serkes and Menachem Mendl Krohaben . Gerschon Aschkenasi came to Vienna from Poland. In Jewish literature he is described as a great teacher, so he is said to have had his own yeshiva. The ghetto also had its own civil jurisdiction.

| year | Number of families | people |

|---|---|---|

| 1571 | 7th | about 40 |

| 1582 | 7-10 | approx. 40-60 |

| 1599 | 35 | approx. 200 |

| 1601 | 14th | 78 |

| 1614 | 45 | approx. 270 |

| 1615 | 50 | about 300 |

| 1632 | at least 120 | 780 |

| 1650/60 | 1,250 to 1,500 | |

| 1670 | approx. 2,000 to 3,000 |

Ferdinand III's Jewish policy and increase in hostility towards Jews

After quiet times, new difficulties came with the accession of Emperor Ferdinand III . Again the Jews were at the mercy of a new ruler. The mayor and the city council asked in a letter from 1637 to have the Jews deported. They complained about the Jews and saw them as the only culprits in the ruin of the Viennese. In his edition of the documents and files on the history of the Jews in Vienna , Pribram emphasizes that even if the Jews deliver taxes to the emperor,

" So they do not gain such things through their diligence and work or from ligated goods, but first suck it out of the poor Christians that alo with their offering can neither be a thought nor a blessing ... "

In the jurisdiction Ferdinand II assigned all disputes of the Jews not to the Viennese magistrate but to the Obersthofmarschallamt. Ferdinand III. however, 1638 placed legal matters under the responsibility and jurisdiction of the magistrate. Such uncertainties led to a dispute between the Jewish community and the city, as well as to excesses between the non-Jewish population and the Jews of Vienna.

Criminal cases increased, the case of Chazzim from Engelberg (Bohemia) was known. In 1636 he converted to Christianity and changed his name to Ferdinand Franz Engelberger. As a missionary to the Jews, he was less known than for his criminal act. He and two Jewish journeymen attempted a theft in the imperial treasury. They were caught like his accomplices, he should be hanged. Immediately before the execution, he revoked his Christian confession, which he had witnessed shortly before in communion, and accused himself of desecrating the host . The execution was interrupted and non-Jewish Viennese began to slay the numerous curious Jewish spectators and loot their houses. The militia had to intervene to calm the situation. On August 26, 1642 Engelberger was tortured in four different main squares, then mutilated and roasted alive shortly before he was burned.

Expulsion of the Jews in 1670

( See: Second expulsion of the Viennese Jews )

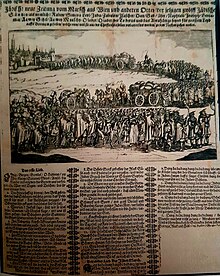

Despite all the difficulties, the community prospered. The population grew, community facilities were expanded, and another place of worship and a hospital were built. The situation of the Jews seemed when Leopold I came to power . not threatening. The emperor, more benevolent than his father, confirmed their privilege on August 26, 1659 and protected them from attacks by non-Jews and the magistrate for the next few years. However, the mood of the emperor changed for uncertain reasons, but a whole series of events, rumors and the constant anti-Jewish attitude of the Christian population and the city of Vienna contributed to a violent solution. This led to the second expulsion of the Jews by Leopold I , which was ordered in 1669 and carried out in 1670.

The displacement had serious financial consequences. Declines in prices, the loss of sources of income such as the Jewish tax or rent, and a poor monetary business led the court chamber to speak out against the expulsion. She pursued the plan to persuade the emperor to withdraw the measures due to fiscal considerations. Their plan allegedly coincided with the last offers from the Jews, which the court chamber probably accepted or was inspired by. In Wischau ( Moravia ) on September 26, 1673, Count Breuner and Gabriel Sellb as representatives of the authorities and Hirschl Mayr as well as other Jews as representatives of the expelled community discussed this option and suggested: One will become the rich Jews among the Allow displaced persons to return if they have to pay a one-off admission fee of around 300,000 guilders and 10,000 guilders per year for further residence rights. Furthermore, the court chamber argued that the admission of the Jews and the subsequent income would be a great advantage for the state and the population. Nevertheless, the emperor found that the matter was of the highest theological (i.e. religious) importance, and thus the negotiations that dragged on until 1675 were doomed to failure. The Jews stayed away, only a few who began the history of Viennese Jews for the next centuries were admitted.

The age of the court Jews

While in the 17th and 18th centuries mercantilism increasingly placed the economy under the authority of the state, court Jews with individual activities on behalf of the princely gained a lot of leeway during absolutism as pioneers of the free economy.

Decades of war on two fronts and the Second Siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1683 shattered Austrian state finances and the economy. Samuel Oppenheimer , who had been the army supplier and chamber agent of the Elector Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz since 1660 , was appointed to Vienna as financier. In the war years it served the imperial court as an indispensable Oberhofaktor , since it procured material and army supplies in abundance for all theaters of war. In this way he financed most of the Danube fleet. In addition, he also became a purveyor to the court and court banker, made loan and exchange transactions and supplied the court with all sorts of luxury goods, procured timber for the Kaiserebersdorf Palace and even supplied the archducal fodder office with straw, oats and hay.

Still, his position was weak. Much of the population blamed him for the heavy taxes, the economic hardship of the poor, and the poor condition of the poorly paid, ill-dressed army. On July 21, 1700, the crowd took action against his house at the farmers' market. The house was stormed and looted, letters and documents torn up, furniture and furnishings stolen and in part demolished. When the guard stepped in, several looters were killed, some in combat, some by death while hanging. According to official information, the damage was estimated at 100,000 guilders .

After Oppenheimer's death in 1703, his nephew Samson Wertheimer , who had been called to Vienna from Worms , was appointed court factor. His financial achievements in the War of the Spanish Succession were decisive . He was immediately given a letter of protection with a guarantee of free religious practice and free residence. In Vienna, however, he could not work as a rabbi, but went to Eisenstadt for this purpose , which belonged to the seven communities where Jewish life was welcome at the invitation of Prince Paul I, Esterházy . The position of Oppenheimer and Wertheimer remained tied to their personal talents and personality, because their sons already had difficulties in saving the legacy and in fighting the decline of the houses.

Early 18th century

Since the Peace of Passarowitz in 1718 there was a small Sephardic-Turkish community in Vienna . As subjects of the sultan, they were under his protection and educated under Charles VI. a religious community with its own synagogue, which the overwhelming Ashkenazi majority was only granted by Emperor Franz Joseph I. Around 1885 the Sephardic community built the Turkish Temple . Charles VI led a rather anti-Jewish and restrictive Jewish policy: numerous prohibitions, laws and three Jewish ordinances from 1718, 1721 and 1723 aimed to limit the number of the Jewish population.

Theresian time

This anti-Jewish stance was continued under Maria Theresa . There were new pressures through stricter Jewish regulations in 1753 and 1764. Nonetheless, the Jewish court factor Diego d'Aguilar worked in Vienna and financed large projects. In 1742 he lent the court 300,000 guilders so that Maria Theresa could expand Schönbrunn Palace . He is also considered one of the founders of the Sephardic Community in Vienna. In 1777, a few years before her death, the monarch wrote:

“In the future I should not allow any Jew as they are called to be here without my written permission. I know of no worse plague of the state than this nation, because of fraud, usury and money contracts, bringing people into begging status, engaging in all evil acts which another honest man detested; ... "

Jews were only granted audience behind a screen, a screen. When Emperor Franz I , her husband, bought Göding in Moravia in 1762 , the Jews living there had to leave the place because Maria Theresa would not tolerate them. Nonetheless, the Jewish communities of the monarchy made clear their loyalty to the patroness. In October 1752 452 Jews were living under the protection of letters of protection given to 12 heads of families.

According to a Jewish ordinance of May 5, 1764, Jews were allowed to stay in Vienna for five to ten years; The Jewish order makes the mercantilist economic policy clear: Jews should trade in domestic manufactured products and establish numerous factories. Any trade in foreign goods was strictly prohibited. Court factors and agents such as Franz Anton von Sonnenfels (brother of Joseph von Sonnenfels ), Adam Isaak von Arnstein (1721-1785) and Abraham Wetzlar (1715-1799) worked under Maria Theresa .

Many court Jews adhered to the traditional laws of Judaism. However, many descendants of the court Jewish families were baptized, such as Abraham Wetzlar, whose son Raymund Wetzlar became a friend of Amadeus Mozart and thus became the godfather of the son of Mozart named after him, Raymund. Joseph von Sonnenfels' father, Lipman Perlin (who moved to Nikolsburg from Berlin ), was baptized, like his son. As an educator, he campaigned for the abolition of torture and the death penalty and also introduced street lighting in Vienna. Conversions to Christianity increased under the influence of the Haskala , emancipation and the Enlightenment .

Age of Enlightenment , Haskala, and Josephinian Legislation

The Jewish Enlightenment

Jewish enlighteners, called maskilim , tried to spread secular education among Jews. All Jews were supposed to learn German so that integration into society could be facilitated and thus the position and equal rights could follow. In the first half of the 18th century Berlin experienced an upswing, be it in terms of population, in trade or as a magnet for intellectuals. It was in this intellectual climate that the Haskala began again. A central figure of the Haskala was Moses Mendelssohn , who, together with Israel Samosc , Aharon Gumpertz and Abraham Kisch , acquired secular knowledge and translated the Bible into German with Hebrew letters in order to get Jewish readers to learn German.

The first Maskilim in Vienna, like Mendelsohn himself, were mostly self-taught and acted as private tutors or worked for the first non-Jewish Hebrew printing works (Jews were not allowed to own a printing house or even be a printer), those of Josef Hraschansky, Josef Lorenz by Kurzböck and Anton Schmidt. When the import of Hebrew scripts was banned around 1800, Vienna rose to a monopoly position in the empire. The printers supplied the country with works of Haskalah , reaching a large audience, but especially in the eastern areas such as Galicia , where the Misnagdim the influences of Maskilim and Hasidic tried to curb flows.

Josephine Edicts of Tolerance

In a hand-held ticket, Joseph II outlined his ideas for a new Jewish policy. This billet was finally presented to the Austrian and Hungarian court chancelleries, where heated debates broke out. The court chamber and the council of state were in favor of tolerance, while the Austrian court chancellery and the church spoke out against it.

The primary aim of the tolerance patent was probably to increase the economic and economic benefit of the Jews. In a resolution of October 1, 1781, the emperor declared that he by no means intended

"To expand the Jewish nation in the hereditary lands or to re-introduce it where it is not tolerated, but only to make it useful to the state where it is and to the extent that it exists as tolerated".

The tolerance patent for the Jews of Vienna and Lower Austria followed on January 2, 1782, after those for Bohemia and Silesia . The moral position of the Jews changed suddenly. All humiliating and shameful badges and costumes were abolished, as was the ban on going out on Sunday mornings. Visiting public inns, bars and living in every area (in Vienna) and keeping Christian servants was allowed. Art academies and colleges opened up to Jews, and the body toll for Jews was abolished. The latter always brought a lot of displeasure; Foreign Jews who came to Vienna were treated on an equal footing with cattle and had to pay a fee for themselves. Above all, however, regulations that hindered Jews economically were repealed, which brought significant advantages for Jews in trade. For the first time since the introduction of such laws in the High Middle Ages, they were given the choice of trade and commerce. In addition, as under Maria Theresa, they were urged to set up manufactories and factories.

Although the situation of the Jews improved considerably in contrast to other areas, the patents made things more difficult. Jews were still not allowed to own land and were not allowed to write documents in Hebrew or Yiddish . In addition, their recently approved schools had to teach German or Hungarian , which was applauded by the Maskilim . They saw this as an opportunity to realize their educational and upbringing desires and their own ideas. As part of the tolerance patents, Jews from all hereditary countries and parts of the monarchy had to choose fixed surnames on July 23, 1787, as until then Jews only had first names to which the father's name was added (e.g. Schloime ben Awrum; Salomon, son of Abraham or in the case of a woman: Ruchl asked Itzig; Rachel, daughter of Isaac). These family names had to be submitted to the competent magistrate by November 30th, together with a confirmation / certificate from a rabbi, but since no rabbi was allowed to work in Vienna, two members of the Wertheimer and Leidersdorfer families took on this role. Nonetheless, discriminatory surnames were sometimes assigned by anti-Jewish officials (names such as Mauskopf or Schnarch).

In the course of the patents, Jews were also used for military service if necessary. In July 1788, 2,500 Jewish soldiers were serving in the imperial armies, and the first Jewish soldier was killed in the Battle of Belgrade against the Ottomans. Until 1789 they were only allowed in artillery units, later also in regular infantry units. In contrast to other German areas, there were already Jewish officers and even generals in the armies.

Emperor Joseph II issued his tolerance patent under the influence of the Enlightenment and mercantilism, which probably opened the way to the emancipation of the Jews . For the first time, certain civil rights were granted and some discriminatory provisions lifted. However, the formation of a congregation and the public holding of church services as well as the acquisition of land remained prohibited. However, full equality did not exist until the next century, but this did not seem to stop the beginning of Jewish assimilation within the framework of emancipation and the Edicts of Tolerance.

Beginning of Jewish assimilation

On the eve of the coalition wars

The special positions of prominent Jewish personalities provided an important trailblazer for the social reception of the Jews. What the Oppenheimers or Wertheimers started in the 17th century was continued by families like Arnstein or Eskeles. From a social and religious point of view, these leading strata began to separate themselves from the broad mass of their co-religionists and to climb the social ladder further. A famous example would be that of Fanny von Arnstein . As the daughter of the Berlin community leader Daniel Itzig , she made it into the highest circles of society, she introduced literary salons and the Christmas tree in the capital of the Habsburgs. Thanks to Leopold II's Jewish-friendly policy, the self-confidence of Vienna's Jews continued to grow. So in February 1792 they submitted a petition to the Lower Austrian government. On March 1, 1792, however, Leopold II died and his successor Franz II seemed to want to restrict the privileges of the Jews again. So the complaint, which, among other things, demanded the right to buy immovable goods, to settle freely and to be admitted to public office, remained unsuccessful. Most of the points, with the exception of minor requests, were strictly rejected. Nonetheless, the feeling of belonging among this upper class turned into staunch patriotism during the war years .

Jewish patriotism

The patriotism of the Jewish subjects exceeded their sympathy for the ideas of the French Revolution. The Jews took over the costs of setting up units, wealthy banking families such as Arnstein or Eskeles financed the Tyrolean uprising of Andreas Hofer against the Bavarian occupation. Jewish officers also died in combat, one of many is Lieutenant Maximilian Arnstein, who died in a battle near Kolmar in 1813. Simon von Lämel (1767-1845) were awarded war honors for his services as an army supplier. Markus Leidersdorf (Jewish name: Mordechai Naß, 1754-1838) organized the military hospital system, for which he was praised by the commander-in-chief of the Battle of Leipzig , Prince Schwarzenberg . On June 19, 1814, after the victory over France, a thanksgiving service was held in a prayer house in Vienna. Since on September 27, 1791, the Jews in France were treated as equal to the rest of the citizens, all Jews of the countries that were under Napoleon's sphere of influence could enjoy such equal rights. In Prussia, too, the law of 1812 made them residents and full citizens. The Jews in the entire German-speaking area believed they could hope for a revision of their rights at the Congress of Vienna .

19th century - On the way to equality

Congress of Vienna and Vormärz

After the fall of Napoleon , in whose fall the Jews of Vienna as well as the Jews of all other German-speaking countries had taken part, they hoped for the hour of their liberation. Their hopes were to be dashed with the suppression of the revolutionary spirit and the systematic passing over of liberal ideas during the reorganization of Europe. Although Wilhelm von Humboldt's (1767-1835) proposal for a uniform equality of the Jews as ordinary citizens was accepted by Prussia and Austria, small and medium-sized German states offered bitter resistance to such emancipation of Jews, especially Hanseatic cities such as Hamburg and Bremen , Lübeck and also Frankfurt am Main. The sixteenth article of the Federal Act of the German Confederation stated that the Jewish legislation is left to the individual seeds. However, the Jews of Vienna attempted to petition Emperor Franz I on April 11, 1815 for equal rights. This petition was signed by Nathan Adam Arnstein, Simon Lämel , Leopold Herz and Bernhard Eskeles , all of whom were respected personalities because of their involvement in the war. After years of waiting, in 1820 the expected emancipation was left to an indefinite future.

In 1824, at the intercession of Michael Lazar Biedermann (1769–1843), Rabbi Isaak Mannheimer was called from Copenhagen to Vienna. Since there was still no official recognition of the community, he was employed as the "director of the Vienna imperial-royal approved public Israelite religious school". It was similar for Lazar Horowitz , who was appointed rabbi to Vienna in 1828 and initially held the title of “ritual overseer”. Mannheimer carefully implemented reforms in Vienna without dividing the Jewish community, as was the case in most communities in Europe in the 19th century. After Mannheimer worked from 1829 to 1835 Dr. Josef Levin Saalschütz and after him Leopold Breuer as religion teacher. Mannheimer, together with Horowitz, also campaigned for the lifting of the discriminatory “ Jewish oath ” ( more judaico ). The merchant Isaak Löw Hofmann played a leading role in Viennese community life from 1806 until his death in 1849. On December 12, 1825, Mannheimer laid the foundation stone for the city temple planned by Joseph Kornhäusel at Seitenstettengasse 4, which he inaugurated on April 9, 1826. In the same year, Salomon Sulzer von Hohenems was appointed senior cantor at the new city temple, where he worked for 56 years. In the 1820s, a certain community organization took place, since the club system also flourished; so in 1816 a women's charity was founded and craft associations were formed. As part of the desired emancipation, they tried to change the trade structure of the Jews, which was focused on trade.

Despite numerous regulations for residence permits, there was an increasing influx of Jews, so that the number of Jews living in Vienna rose steadily. From a legal point of view, Jews were only allowed to stay in the city permanently if the head of the family had received a letter of protection. However, many Jews found ways of circumventing the law, even in the literal sense: Since foreign Jews were allowed to stay in the city for 48 hours, one often went out of the city at a gate to get back into the city through the next gate , and just signed up as a new addition, which was often made easier with a little money for the guards. With an ironic allusion, the Jews called such a process "kaschern" (ritually cleaning something, i.e. making it kosher ). Tolerated Jewish families could employ servants. Jewish teachers were often recruited for the families' children. If the children finally grew up, it was possible to simply register as “ Mezusot anbringer ” or “Fleischaussalzer” in order to stay in Vienna. Nonetheless, most of the Jews in Vienna lived with very limited job opportunities and, because of their living conditions, were open to revolutionary ideas and to a change in social conditions; a prelude to the revolution .

From the revolutionary year of 1848 to the cultural heyday

|

Jews in Vienna according to the census and the respective territorial status |

|||

| year | Ges.-Bev. | Jews | proportion of |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 476.220 | 2,617 | 1.3% |

| 1869 | 607.510 | 40,277 | 6.6% |

| 1880 | 726.105 | 73.222 | 10.1% |

| 1890 | 817,300 | 99,444 | 12.1% |

| 1890 * | 1,341,190 | 118,495 | 8.8% |

| 1900 | 1,674,957 | 146.926 | 8.7% |

| 1910 | 2,031,420 | 175.294 | 8.6% |

| 1923 | 1,865,780 | 201,513 | 10.8% |

| 1934 | 1,935,881 | 176.034 | 9.1% |

| 1951 | 1,616,125 | 9,000 | 0.6% |

| 1961 | 1,627,566 | 8,354 | 0.5% |

| 1971 | 1,619,855 | 7,747 | 0.5% |

| 1981 | 1,531,346 | 6,527 | 0.4% |

| 1991 | 1,539,848 | 6,554 | 0.4% |

| 2001 | 1,550,123 | 6,988 | 0.5% |

| * after the big city expansion | |||

Jews and the Revolution

Already at the beginning of 1848 conflicts arose in Lombardy-Veneto and in February 1848 the Paris Revolution broke out . From these areas the irritable mood spread throughout Europe. Many Jewish students campaigned for the 1848 revolution , but there were also opponents. The most prominent is the banker Salomon Mayer Freiherr von Rothschild; he even financed Metternich's escape to England.

Adolf Fischhof , secondary physician at the General Hospital, played a notable role in the revolution . On March 13, 1848, he gave a speech to revolutionaries and gave them a revolutionary program. When the military shot at armed revolutionaries who erected street barricades, two Jews, Karl Heinrich Spitzer and Bernhard Herschmann, were among the first victims. When all Christian and Jewish victims were buried in the Schmelzer cemetery , the cantor Salomon Sulzer and the preacher Isaak Noa Mannheimer appeared. The brotherhood in arms and the resulting relationship between Christians and Jews seemed to be growing stronger. The tape did not last long, however, and with new freedom of the press in the city open hostility towards Jews spread. Nevertheless, many Jews hoped for equality from the revolutionary government. This granted equal rights only on July 29, 1848, when the defeat of the revolutionaries was approaching.

equal rights

After Emperor Franz Joseph I spoke of a “Jewish community in Vienna” when a Jewish delegation was received in 1849, an independent religious community was formed in 1852. By 1875 numerous communities had been established throughout Austria, Vienna was one of the first.

In 1867 in Cisleithanien , the part of the previous state that remained imperial, the Basic Law on the General Rights of Citizens guaranteed Jews for the first time in their history unhindered residence, free movement, the purchase or possession of real estate and, above all, the practice of religion. The interdenominational law of May 25, 1868 finally achieved the legal equality of the Jews of Vienna.

The Jewish community grew very quickly as a result of these developments, because after the removal of the so-called Jewish barriers, the Jews, who had been a more urban people since the Middle Ages, were able to settle in Vienna unhindered: In 1860 the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien registered 6,200 Jewish residents (approx 2.2% of the total population), in 1870 there were already 40,200 and at the turn of the century 147,000. The second district since 1850, Leopoldstadt , named after Leopold I , who had the Jews expelled from there in 1669/1670, developed into the center of Viennese Jewry during this phase. In the interwar period, the Jewish population made up almost half of the entire district population, which is why non-Jews used the derisive name Mazzes island . One of the reasons for such a gathering of Jewish residents was the then North Railway Station , which was a junction of the eastern railway networks in the Habsburg Empire. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, countless immigrants from the east arrived at this train station in Vienna. Among them were numerous Jews who simply settled near their place of arrival. While wealthy bourgeois Jews lived on avenues like Praterstrasse, poorer Jews had their quarters in the back alleys of the avenues.

The neighboring districts also had a large proportion of the Jewish population: Brigittenau (separated from Leopoldstadt as the 20th district in 1900) and Alsergrund (9th district). The Jewish population living in the above-mentioned districts, who made up the majority of the Jewish Viennese, mostly belonged to the lower or middle class - they were workers, craftsmen, small business owners (e.g. cafes) and traders. The wealthy Jews lived mainly in the villa areas of Döbling (19th district) and Hietzing (13th district) as well as in the city center, the inner city .

Contribution of the Jews to the heyday of Vienna and the community

Numerous personalities lived in Vienna who were of great importance for Judaism and / or for the general contribution to culture. When higher education institutions opened to Jews in 1867 with the introduction of equal rights, their professional life was no longer limited to trade and money business for the first time since the Middle Ages. Administrative, intellectual and artistic professions were now largely open to them. This was the beginning of the heyday, the development of which was largely of Jewish origin.

Viennese heyday: fin de siècle and interwar period

The full emancipation of the Viennese Jews did nothing to change the political commitment of numerous intellectuals. On the one hand, personalities such as Victor Adler , Otto Bauer and Julius Tandler were committed to social democracy for a just society. They achieved many of their goals in " Red Vienna " during the interwar period . On the other hand, Theodor Herzl founded modern Zionism at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century , which saw the solution to the problems of anti-Semitism and the questions of Jewish identity in times of increasing assimilation in the creation of a Jewish state of its own . The religious community, which at this time was mainly run by assimilated Jews, was far from emigrating. In response to anti-Semitism, thousands of Jewish Viennese changed to Christian denominations, which in 1938 did not turn out to be a protection against anti-Semitic terror. The German National Party, a party hostile to Jews during the interwar period, was also founded by the Jew Ignaz Kuranda .

When equality came in 1867, the way to schools and universities finally opened up for Jews. The Jews of Vienna made an important contribution to science and culture and thus made Vienna a scientifically and culturally prestigious city in Europe. From the large number of personalities, only a few of the most famous from the various areas of cultural and intellectual life can be cited here. The fame of the Vienna Medical School, for example, goes back in large part to the achievements of doctors of Jewish origin: Julius Tandler , Emil Zuckerkandl , Josef Breuer , Robert Bárány and Otto Loewi are just a few of the famous names in science. Sigmund Freud , the founder of psychoanalysis , used new methods to study the human psyche and to treat mental disorders, and his student Alfred Adler developed individual psychology . The law teacher Hans Kelsen is one of the most important representatives of legal positivism and the creator of the Austrian constitution . As physicists and physicists are Lise Meitner , Wolfgang Pauli and Felix Honorable mention, as biochemists are Max Perutz , as botanists Julius von Wiesner , a chemist Fritz Feigl , Leo Grünhut, Edmund von Lippmann and Otto von Furth and as an astronomer Samuel Oppenheim as examples mention. The founders of modern classical music , such as Gustav Mahler , Arnold Schönberg and Alexander Zemlinsky , worked in Vienna. Max Reinhardt was one of the co-founders of the Salzburg Festival . The list of Jewish writers and publicists is also particularly long ; it encompasses an essential part of the Austrian literary history of the 20th century: including Arthur Schnitzler , Hermann Bahr , Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Franz Werfel , Stefan Zweig , Franz Kafka , Friedrich Torberg and Vicki Baum . Publicists such as Egon Friedell , Karl Ausch , Friedrich Austerlitz and Anton Kuh , philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein , Karl Popper , Martin Buber , Josef Popper-Lynkeus and cabaret artists such as Karl Farkas , Fritz Grünbaum , Hermann Leopoldi and Hugo Wiener were prominent contributors.

The artists found the right audience for their new ideas in the salons of the Jewish upper class, and here the designers of the Wiener Werkstätte and the Art Nouveau architects received a large number of their commissions. For example, Johann Strauss (son) , Gustav Klimt , Arthur Schnitzler, Max Reinhardt and Franz Theodor Csokor met in the Berta Zuckerkandl salon . Alma Mahler-Werfel met Gustav Mahler here in 1901 . Even the most famous cafés in Vienna, places of exchange and visiting centers for intellectual or prominent personalities, mostly had Jewish owners.

From Ephrussi to Rothschild; known urban heirs

Apart from the numerous scientists, artists and politicians, some Jewish families not only shaped the history, but also the urban landscape of Vienna. Department stores like Herzmanzky or Gerngroß are still popular or known today. Baron Nathaniel Rothschild , who died in 1905, became famous for his charitable foundations. He was the only person in the history of Austria who donated such large sums to the general public. These include the Vienna Polyclinic with over one million kroner, the Vienna Voluntary Rescue Society also with one million kroner, and he donated a further two million to 117 charitable associations regardless of denomination. The largest single donation, however, went to the Foundation for Nervous Illnesses at Rosenhügel in Vienna, at 20 million crowns. He laid down this donation and another one for the sanatorium in Maria-Theresien-Schlössel in his will.

Many palaces were also built by the Rothschilds, such as the historic city palace in Theresianumgasse on the Wieden (it was demolished after 1945), the Rothschild palace in Renngasse , the one in Metternichgasse , and the Albert Rothschild palace in Prinz-Eugen-Straße and the more famous Palais Albert Rothschild . In addition to the New Hofburg, the latter was the largest and most important palace from Viennese historicism. It and two other Rothschild Palais in the 4th district were demolished by the Chamber of Labor in the 1950s. The monument office offered strong resistance because the buildings were in good condition, contrary to the justification of the Chamber of Labor, which said that the palaces were dilapidated. The famous Rothschild hospital on the Währinger Gürtel was no different. It was sold to the Chamber of Commerce and replaced by the Economic Development Institute (Wifi). Doctors such as Otto Zuckerkandl and Viktor Frankl worked in this hospital . The already mentioned North Station , one of the most magnificent station buildings on the European mainland, founded and financed by Salomon Rothschild , took the place of a displaced inheritance and was blown up and demolished on May 21, 1965.

The Ephrussi banking family was one of the most influential families in Europe. The family, originally from Russia, found their new home in up-and-coming Vienna in the 19th century. Their ancestors came to Vienna from Odessa and built their own private empire in the heart of the imperial state. The Palais Ephrussi at Universitätsring 14 still testifies to the great success and wealth of the family. The Wilhelminian-style palace was designed and built by Theophil Hansen in the neo-renaissance style. The magnificent building was a mixture of a palace and an apartment building, as separate rental apartments were also built above the obligatory bel étage. When Austria was "annexed" to the German Empire, the family fled from Austria to France, Great Britain, Spain, the USA, Mexico and even Japan. Edmund de Waal first told in 2010 in his bestseller The Hare with the Amber Eyes - The Hidden Legacy of the Ephrussi Family of the rise of the banking family and their expulsion by the National Socialists. In 2018 Edmund de Waal donated 170 items on permanent loan to the Jewish Museum Vienna .

The parish's heyday

These cultural and legal developments led to a high point in Jewish life in Vienna. Numerous personalities, buildings and associations bear witness to this.

Isaak Löw Hofmann , raised to the nobility as "von Hofmannsthal" in 1835, was one of the most important promoters of traditional rabbinical values and spurred the construction of the Vienna City Temple . Isaak Noah Mannheimer , as rabbi of the city temple, managed to avoid the break between orthodoxy and reform in the community, and Salomon Sulzer, as cantor at his side, renewed the singing in the synagogue. In the second half of the 19th century, Adolf Jellinek , the liberal rabbi of a synagogue in Leopoldstadt, gave the Jewish community new impetus. After the First World War, Zwi Perez Chajes , who was committed to the Zionist ideal, was particularly active as chief rabbi in education, and founded the first Jewish grammar school and the Jewish pedagogy in Vienna. The Jewish grammar school, which reopened in 1984, was named after him in recognition of his achievements. In 1886 the Austrian-Israelite Union was founded by Rabbi Bloch, with the aim of defending the political rights of Jews, improving Jewish education and promoting the pride of Jews in their own identity.

The Jewish influx into the city made the Jewish community grow strongly. Nonetheless, most of the growth came from the Austrian and Hungarian eastern regions of the dual monarchy. The main contingent was made up of immigrants from Bohemia , Galicia and Hungary , the rest mostly consisted of Jews from Bukovina and Moravia . This also changed the character of the Jewish settlement, from short stays due to business reasons or the possession of a letter of protection (before the constitutional law of 1867) to permanent settlement.

This change pleased neither the long-established assimilated Jews of Vienna nor the Christian population. Most of the immigrants from Galicia and Bukovina came from precarious backgrounds and were thus religiously more orthodox and conservative. They differed in their traditional customs, so numerous "Shtibl" (prayer houses) or "heathen" houses of worship were built, as the "Templjidn" with their large and magnificent synagogues were too strange for them. As an example one could cite the Polish school of Polish Jews, the second large Orthodox group was the Hungarian, its center was the ship school . The appearance of the Orthodox immigrants was the eastern caftan , the Pajes and Zizes coined. Yiddish was usually the only language well known. Due to the refugees of the First World War, Vienna became the seat of famous Hasidic dynasties after 1918, such as the Czortków rabbi Israel Friedmann.

As the number of parishioners grew, so did the demand for places of worship. In the second half of the 19th century, the construction of synagogues, temples and prayer houses really blossomed. Churches of God were not only built in Leopoldstadt, but in all districts of Vienna, from the Währinger Tempel to the Humboldtempel to the most famous temple in Vienna from before 1938, the Leopoldstädter Tempel. This synagogue, built from 1854 to 1858 according to plans by Ludwig Förster , offered 2,000 seats and served as a model for numerous other synagogues in Europe that were built in the oriental style , including the Zagreb Synagogue , the Spanish Synagogue in Prague , the Tempel Synagogue in Krakow and the Templul Coral in Bucharest . This proves the supraregional importance of Vienna in Judaism and the influence on Judaism in Europe. Vienna was a center of Jewish life.

From the last third of the 19th century, Jewish community life was shaped by diverse and diverse religious, social and cultural associations. According to the records of the standstill commissioner for clubs, organizations and associations, there were 589 Jewish clubs all over Austria on March 13, 1938. In addition, there was the strengthening of political Zionism and socialism and with it the founding of numerous Zionist-socialist associations with a focus on a future life in Palestine. Many Jews organized themselves in socialist and / or Zionist (youth) movements. The largest of these were Hashomer Hatzair , Poale Zion (Workers of Zion) and the Jewish Socialist Youth Workers. Such an increase in Jewish existence and influence did not make anti-Semitism long in coming. The inter-war period can be seen as the harbinger of the increasingly popular racist anti-Semitism that ultimately led to genocide.

End of the monarchy, the first republic and the Nazi era

| Participation of the Jews | |||||||

| in professional and economic life (1934) | proportion of | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| doctors | 51.6% | ||||||

| Pharmacies | 31.5% | ||||||

| Credit bureaus | 82.0% | ||||||

| Driving schools | 13.0% | ||||||

| Bakers and bread factories * | 60.0% | ||||||

| Banks | 75.0% | ||||||

| Druggists | 26% | ||||||

| Butcher | 9% | ||||||

| Photographers | 34% | ||||||

| Hairdressers | 9.4% | ||||||

| Garages | 15.5% | ||||||

| Jewelers | 40% | ||||||

| Coffee houses | 40% | ||||||

| Cinemas | 63% | ||||||

| Furrier | 67.6% | ||||||

| Milliners | 34% | ||||||

| optician | 21.5% | ||||||

| Leather dealer | 25% | ||||||

| Lawyers | 85.5% | ||||||

| Advertising agencies | 96.5% | ||||||

| Pub trade | 4.7% | ||||||

| locksmith | 5.5% | ||||||

| Shoe manufacturing | 70% | ||||||

| Spengler | 20% | ||||||

| Textile industry | 73.2% | ||||||

| Watchmaker | 32% | ||||||

| Dental technician | 31% | ||||||

| Candy shops | ≤ 70% | ||||||