Jesus Sirach

| Textbooks or wisdom books of the Old Testament |

|---|

Names after the ÖVBE . Pseudepigraphs of |

Jesus Sirach (or Ben Sira , the Siracide , the Sirach Book , abbreviated Sir ) belongs to the so-called late writings of the Old Testament . The book is named after its author, who lived around 190/180 BC. In Jerusalem wrote the original Hebrew version.

The author lived in a world that was shaped by Hellenism and ran a Jewish "House of Education" based on the model of a Greek school of philosophy . His writing probably grew out of these lessons and therefore a kind of textbook. Ben Sira presented an overall draft of the religious traditions of Israel that was modern for the time; he tried to combine the temple cult, Torah and wisdom . Practical advice takes up a lot of space, with no other biblical author exploring marriage, family, and friendship as extensively as Ben Sira. He also imparted to his students a certain cosmopolitanism, which was desirable for their later work; probably because of this he discussed appropriate behavior at a symposium , education through travel, or the benefits of medicine.

Around 130/120 BC In Alexandria the grandson Ben Siras, who himself remains anonymous, wrote a translation into Greek . This is the beginning of a history of the updates to the Sirach Book, both in Hebrew and in Greek. These are more or less extended new editions that were created with a sidelong glance at the other language version. The Greek Book of Sirach was included in the broad tradition of the Septuagint . The Hebrew Book of Sirach, on the other hand, did not make it into the canons of Jewish holy scriptures and was not passed on in late antiquity . It was then circulated again in medieval Jewish communities, probably due to ancient text finds. Then it disappeared again and reappeared in fragments from 1896 in the Cairo Geniza , later in Qumran and Masada , albeit incompletely.

The Sirach book crosses the boundaries between religions and denominations: although it was never considered holy scripture in Judaism, the Talmud argued with Ben Sira as if he were a rabbi . Ben Sira endowed the woman wisdom with features of the Egyptian deity Isis . Identified with Mary , she is called in Catholic piety as the “mother of beautiful love”. In the same context, some plants were taken from the Sirach text as symbols of Mary . Martin Luther removed the Sirach Book from the Old Testament and classified it under the Apocrypha ; but it was widely read in Lutheranism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and inspired church music. In late antiquity and then again in the early modern period , the Sirach book was a kind of advisory literature in Christianity.

Book title

The work is referred to in rabbinical literature as the "Book of Ben Sira" ( Hebrew ספר בן סירא ṣefer ben Ṣiraʾ ), in the Septuagint as "Wisdom of Sirach" ( ancient Greek Σοφία Σιραχ Sophía Sirach ) and in the Vulgate as (Liber) Ecclesiasticus , the "ecclesiastical (book)." The first author to testify to this Latin title, was Cyprian of Carthage in the 3rd century. The unison easily leads to confusion with Ecclesiastes , the title of the book of Ecclesiastes in the Vulgate.

Author, time and place of origin

Ben Sira in Jerusalem

The author's name is mentioned in Sir 50:27, but there are different textual traditions:

- "Shimon, the son of Yeshua, the son of Eleazar, the son of Sira;" (Hebrew manuscript H B )

- "Jesus, the son of Sirach, Eleazar, the Jerusalemite." (Greek text tradition of the Septuagint)

There are also other variants. The author's proper name was either Shimon / Simon or Jeschua / Jesus. The latter is more likely, since the grandson (who should know) simply referred to him in the prologue as "my grandfather Jesus". Johannes Marböck considers that the name Shimon / Simon in the handwriting H B from the praise of the high priest Simon ( Sir 50.1.14 EU ) was accidentally taken over into the textual adjacent book signature . Since both Yeshua and Shimon were extremely common names, the author was clearly identified by the addition of Ben Sira . This can be an indication of origin (Yeschua from the place Sira) or a patronymic (Yeschua, son of Sira), whereby Sira does not necessarily have to be the father - it can also be a previous ancestor. The Hebrew Sira became a Sirach in the Greek text . The letter Aleph (א) at the end of the Hebrew name Sira was spoken audibly ( voiceless glottal plosive ), and the Greek letter Chi (χ) was used to represent that in Greek that does not know such a sound .

Ben Sira lived around the turn of the 3rd to the 2nd century BC. In Jerusalem. The religious center of Judaism was located there. For Ben Sira, the Jerusalem temple was the center of his world model; as the center of Hellenistic-Greek culture in the region, however, the city of Gadara, southeast of the Sea of Galilee, had a greater impact. In the Ptolemaic Empire, Judea belonged to the province of Syria and Phoinike ( Koilesyria ) and was a separate administrative unit (hyparchy) within this greater province. It consisted of the city of Jerusalem and the population of the surrounding area; the local government was exercised by the high priest .

After the battle of Paneion around 200 BC. Chr. The supremacy over Koilesyrien passed from the Ptolemies to the Seleuciden . When he entered Jerusalem, Antiochus III met. "To proseleucid circles, who had long worked ahead of the change of rule and which not least included the members of the high priestly family of the Oniads." He arranged his relations with the ethnos ( ancient Greek ἔθνος ethnos , dt. Roughly "people, tribe") of the Judeans , his new subjects, in the following way: Although the Judeans were generally assessed as loyal, only "their city", namely Jerusalem, was rewarded. The Judeans were allowed to live according to their traditional laws. The Seleucid government was not interested in what this meant in terms of content (whether these traditional laws meant the Torah, and if so, in what interpretation) as long as their own claim to power was not affected. The temple was more interesting from their point of view because the king was able to relate to it through cult patronage. Antiochus III. showed his generosity and piety, as befitted him as a Hellenistic ruler: he had repairs carried out on the temple and sacrifices made at his expense. In addition, there were tax breaks for the members of the council and groups with a relationship to the temple, including the temple scribes ( ancient Greek γραμματεῖς τοῦ ἱεροῦ grammateĩs toũ hieroũ ). With these measures, the Seleucid government reinforced an already existing tendency towards a centralized temple state. In the historical figure of the high priest Simon II , who was officiating at the time, royal and priestly traits were combined. Ben Sira, his contemporary, let the whole history of Israel run towards this personality in his book and thus turned out to be an outspoken partisan of the Oniads.

After his defeat by the Romans in the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BC. BC Antiochus III. to make high reparation payments. Accordingly, the subjects of the Seleucid Empire were put under financial pressure; that also affected Jerusalem. The lot of the rural population was even harder, and in Ben Sira's work they were characterized as poor, hungry and desperate. According to some exegetes, Ben Sira refers to this historical situation with his supplication for the salvation of Zion ( Sir 36: 1–22 EU ). A term post quem for the writing of the work. Terminus ante quem is the Maccabees uprising during the reign of Antiochus IV. Epiphanes , 167 BC. In the case of Ben Sira, there is still no trace of the tensions between those in favor of Jerusalem and those who oppose a Hellenization, which then erupted in the uprising. There is broad consensus on the dating of the Sirach Book, and because it can be dated, the work “plays the role of an Archimedean point in the history of Israeli-Jewish literature.” This reliable chronological classification also makes it possible to identify Ben Sira's work as a source for Jewish culture and literature To use the history of religion in the Hellenistic epoch.

The popularity of the Sirach Book in Jerusalem may have been damaged by the fact that there since 173 BC. Chr. Only high priests officiated who did not belong to the Oniad family and therefore could not claim any descent from the biblical priestly figure Zadok . "The end of the Zadokids in the high priestly office in Jerusalem led to the fact that the non-Hellenized Zadokid priests fled into the desert, which is probably connected with the origin of the Qumran community."

Ben Sira's grandson in Alexandria

According to his own statements, the grandson of Ben Siras was in the 38th year of reign of King Euergetes (ie Ptolemy VIII Physkon), i.e. around 132 BC. BC, moved to Egypt. It is customary to specify that he was in Alexandria. He translated his grandfather's work into Greek in order to make it accessible to the large Jewish diaspora , namely readers "who are abroad eager to learn that they have (their) attitudes set up to live law-abiding." he gives an account of this project in a prologue. He himself remains anonymous. Stylistically, the prologue differs from the translation of the book; The author presents himself confidently as an educated speaker and writer with a rhythmically designed sentence structure and rhetorical choice of words.

The prologue of the grandson is included in the Greek and Latin, but not in the Syrian version of the Sirach Book. It is interesting in three ways: It indicated that a Jewish canon of holy scriptures was emerging in its day, which consisted of the Torah , books of the prophets and "other scriptures ". Second, he combined a life according to the commandments of the Torah with a Hellenistic ideal of education. And he realized that translating a work from Hebrew into Greek is a demanding task because of the diversity of languages.

The grandson handled the material independently. Several times he adapted the imagery , which Ben Sira has a rural character, to his urban environment. This "cultural translation" can be seen, for example, in Sir 3.9:

- Hebrew text, quoted here from the unrevised standard translation (1980): "The blessing of the father strengthens the root, but the curse of the mother uproots the young plant."

- Greek text, quoted from the revised standard translation (2016): "For the blessing of the father strengthens the houses of the children, but the curse of the mother uproots the foundations."

The grandson did not have his grandfather's manuscript, but a copy that showed defects. He sometimes found it difficult to make sense of the text. "So we understand why he apologized for the quality of his translation, and all in all this translation is not that bad."

The translation of the Sirach book into Greek is part of a rich, only fragments of Jewish-Greek literary output during the Ptolemaic period : the exegetes Demetrios (before 200 BC) and Aristobulus (mid-2nd century BC), the tragedian Ezekiel , the historian Eupolemus , the Samaritan anonymous (pseudo-Eupolemus) - but above all the Aristeas letter , which promotes the translation of the Torah into Greek.

Text transmission

So the Sirach book was originally written in Hebrew. But it is only completely preserved in Greek. Since the work of the grandson, both text versions have developed in parallel, but not independently of one another through updates. There is therefore a Greek short text (GI version) and a Greek long text (G-II version), but also a Hebrew short text (HI version) and Hebrew long text (H-II version). The Hebrew short text is generally considered to be the basic stock of the book, provided it is confirmed by the Greek short text. To simplify matters, the HI version can be seen as the work of Ben Sira, the GI version as the work of the grandson.

A notable phenomenon is the disappearance and reappearance of the Hebrew Sirach text. Even in antiquity, the Hebrew version of the book was apparently "overlaid by the Greek translation in terms of popularity and distribution." As a result, the Sirach book was one of those new Greek books that were particularly popular with Christians in Judaism. It got to the edge of the stream of tradition and did not make it into the Jewish canon of holy scriptures.

The way in which the Hebrew Sirach fragments were preserved can be reconstructed as follows:

- The Hebrew Book of Sirach was one of the literature that was deposited in caves on the Dead Sea near Qumran before AD 70 .

- The Masada Fortress remained in the hands of the rebels until the end of the Jewish War . The Zealots and their families set up living quarters in the casemate wall. Someone, perhaps from Jerusalem or Qumran, brought a scroll containing the text of the Book of Sirach to one of these makeshift shelters.

- Around the year 800 AD, Timotheus I, the Nestorian patriarch of Seleukia-Ctesiphon , reported in a letter that “in a rock a house and many books had been discovered” near Jericho . The Jerusalem Jews “came out in abundance and found the books of the Old (Testament) and others in Hebrew script.” These Dead Sea Scrolls apparently included the Hebrew Book of Sirach, which was subsequently copied and distributed in Jewish communities. Saadja Gaon knew this text because he quoted from it ( Sefer haGalui , 10th century AD). Medieval copies of the ancient Hebrew Sirach text were deposited, along with many other texts, in the geniza of the Ben Esra Synagogue in Cairo. Such an assumption could appear very speculative, but among the texts of the Cairo Geniza there was also the Damascus script from Qumran , which could only have reached medieval Cairo through the discovery of an ancient text repository.

- The Hebrew Sirach text disappeared for the second time after the 12th century, only to reappear in 1896.

Among the old translations, those into Syriac and Latin are of particular importance:

- Syriac ( Peschitta ), 3rd / 4th centuries Century AD. It is a translation from Hebrew using the Greek long text. However, there are significant deviations from both the Hebrew text fragments and the Greek manuscript tradition. Burkard Zapff comes to the conclusion that it is an interpretive translation, similar to a Targum . Therefore, the Syrian translation should be used with great caution for the reconstruction of the Hebrew text.

- Latin ( Vetus Latina ), late 2nd century AD in Christian North Africa. Since Jerome did not translate the book Jesus Sirach in the 4th century AD, this older Latin text was included in the Vulgate - albeit not unchanged . It is based on the Greek long text (G-II version), without changing pages. The Vulgate text is the version in which the Sirach book was read in the Middle Ages.

Outline of the book

“The book ... sometimes looks like a 'supermarket' of wisdom. You don't buy anything there, but find something of everything: a colorful mixture of proverbs, sentences, hymns of praise, ethical, liturgical, historical considerations ... "

Ben Sira apparently did not write his textbook in one go, but took ready-made wisdom and hymn texts, combined them with shorter, self-written texts and edited them in several batches. Often the work is divided into three parts, whereby the small parts of the proverbs and sentences in the first and second main parts stand in clear contrast to the large compositions of chapter 24 on the one hand and the well-composed third main part on the other. Autobiographical notes and prayer texts are structuring signals.

The following structure follows a suggestion by Johannes Marböck :

| Part 1 , Chapters 1–23 | Part 2 , chapters 24.1-42.14 | Part 3 , chapters 42.15-51.30 |

| 1.1–10: Programmatic opening. | 24.1–22: new use. Praise of wisdom about oneself. | 42.15–43.33: Praise the glory of God in creation.

44: 1-50.25: Praise of the glory of God in the history of Israel (so-called "Praise of the Fathers of Israel"). |

| Structuring elements: Texts on the value of finding wisdom | Structuring elements: texts on the search for God, fear of God and Torah | Structuring elements: praise and supplication |

| Autobiographical note: Sir 16 : 24-25 EU . | Autobiographical Notes: Sir 24.30–33 EU ; Sir 33.16-19 EU ; Sir 39.12 EU ; Sir 39.32 EU . | Autobiographical Notes: Sir 50.27 EU ; Sir 51.13-22.25.27 EU . |

| Conclusion: Prayer for self-control | Conclusion: Distinguishing between wrong and right shame | First signature; Beatitude; Thank you song; Acrostic poem about the quest for wisdom; second signature. |

subjects

Ben Sira's teaching house

Ben Sira saw himself as a scribal sage ( Hebrew סוֹפֵר ṣofer , ancient Greek γραμματεύς grammateús ). That was a new job back then. A reference to that of Antiochus III. privileged temple scribes can be assumed.

Sir 51.23 EU is probably the oldest evidence of a Jewish school operation. How one should imagine the Lehrhaus Ben Siras is the subject of discussion. Marböck sees it as “a private academy of the wise in his house.” A minority interprets the “house of education” ( ancient Greek οἶκος παιδείας oĩkos paideías ) as a metaphor for the book written by Ben Sira, that this would be a special, reserved space of study imagined. According to Ben Sira's instructions, the students had their own slaves, had money, had leisure and the opportunity to travel. "Since it is also about issues such as correct behavior at dinners and in court, some also speak of 'career training' for young writers and sages."

Tradition and Inculturation

Israel

Ben Sira's work offers a synopsis of the traditions of Israel, a kind of short version of the Hebrew Bible:

- Wisdom and Torah are associated with one another;

- the wise saw himself following the prophets, as is particularly evident in his standing up for the rights of the poor (Sir 34: 21–35, 22);

- he presents the history of Israel in an original way as a series of short portraits of important men.

This happened against the background that the canon of holy scriptures began to develop in Judaism; in Ben Sira's time there was still a lot going on here. It is interesting that Ben Sira deals with these materials differently than the groups whose literature was deposited in caves near Qumran: he neither commented on sacred texts ( pescharim ), nor did he compile collections of quotations ( florilegien ). Instead, Ben Sira offered his readers "Scriptural interpretation in the mode of re-poetry."

Egypt

The Israelite wisdom literature always participated in a cultural exchange with the wisdom traditions of the ancient Orient. It was international. This can also be seen in Ben Sira. Comparative material to the Sirach book is provided by the (difficult to date) teachings of Ankhscheschonki and the teaching text Phibi or Great Demotic Wisdom Book (Papyrus Insinger, Ptolemaic period).

In Sir 38: 24-39, 11 Ben Sira contrasted the scribe and the mass of the population. The scribe has leisure to immerse himself in the Torah. The farmers and artisans (Ben Sira listed several occupational groups) are needed to make the community work, but they are not asked to act as advisors - “[s] ondern: [T] he creations of the world strengthen them, and their prayer (persists ) in the exercise of their craft. ”( Sir 38.34 EU ) The similarity of this text passage with the Egyptian teaching of Cheti is striking, but a direct literary use has not been proven. “One will not get beyond the observation that Jesus Sirach got to know the Egyptian-wisdom topos 'misery of the craftsmen - splendor of the writers' in some way - perhaps on his trips abroad […], which also led him to Ptolemaic Egypt. "

Hellenistic world

Ben Sira was reluctant but interested in the Hellenistic culture, as can be seen from the theming of the symposium, travel, and medicine. In addition, Ben Sira has a knowledge of Hellenistic literature.

The symposium was at the Hellenistic royal courts, but also on a small scale for the local Jerusalem elite, the "place of prestige formation and status determination." This form of gathering was something new for Ben Sira, to which he wanted to introduce his students (Sir 31.25-32.13). The grandson made changes to the translation that show how common symposia were for Alexandrian Jews two generations later. He added, for example, the duties of the food master ( symposiarches ) ( Sir 32.1 EU ). Ben Sira did not address the religious component of the symposium - how did a Jewish sage behave with the obligatory libation for the gods (which could be interpreted as a violation of the prohibition of foreign gods in the Ten Commandments )? It is possible that the course of symposia in the eastern Mediterranean has been adapted to the respective local milling traditions.

Ben Sira recommended travel as a source of experience ( Sir 34,9-13 EU ). Of course, Ben Sira does not disclose what kind of knowledge he acquired on his international travels. It did not change the fact that the temple in Jerusalem was the center of his theological-geographical model of the world. In this respect, Ben Sira's travels should not be understood in the modern sense as "expanding horizons". According to Frank Ueberschaer, Ben Sira prepared his students for later trips “in the diplomatic service”; the provincial administration had a need for people who z. B. could use their language skills for such missions.

Doctors and pharmacists were singled out by Ben Sira as a professional group that had greater prestige than craftsmen, because like the scribes they had dealings with the mighty. The praise of the doctor ( Sir 38.1–15 EU ) is a top text for the recognition that this profession gained in Hellenistic times. "Here is a job - the only job - that comes close to the wise man himself."

Several studies have been devoted to the influence of Pagan Greek literature and classical Greek upbringing on Ben Sira, with the result that one should consult many Greek authors in order to understand Ben Sira's anthropology , cosmology and theology: Homer , the Tragic , Theognisy of Megara , Menander , Plato , Aristotle , the Stoics and the Alexandrian school of poets ( Aratus von Soloi ). An example of Ben Sira's handling of the classics is the advice not to praise anyone happy before death ( Sir 11.27–28 EU ), which is found several times in ancient literature; the clearest parallel is formed by the closing lines of Sophocles ' King Oedipus . Verses of the Iliad echo in Sir 14.18 EU . However, it remains to be seen whether Ben Sira read these two works or whether he used a collection of quotations . Knowledge of stoic ideas is assumed in Ben Sira in the ideal of the wise and wisdom, in the idea that there is a recognizable law in creation and history that the world is rationally ordered, as well as in the formulations "God of All" and "the Most High. "

Ben Sira's image of society

Richard A. Horsley describes the social status of Ben Sira and his students as retainer of the priestly aristocracy : as scribes they would have had no personal power, but advised the powerful. Ben Sira draws a picture of the Temple State of Judea as a theocracy , the earthly head of which is the high priest, surrounded by his "brothers". This high priest, in Ben Sira's eyes, had a kind of teaching office as interpreter of the Torah; on the other hand, he saw in him the central mediator of divine blessing through the cult acts that he carried out in the Jerusalem temple . The larger political, economic and cultural framework of the Seleucid Empire, in which this temple state only had local significance, is ignored by Ben Sira.

Below the elite there were the "elders" who met in councils. According to Horsley, Ben Sira taught young men who should learn to move around in this circle, but not with their own decision-making authority, but as a consultant. Because of the differences between the Hebrew and Greek texts, there is no accurate picture of the administrative structure of Jerusalem in which Ben Sira's disciples were supposed to take their place. “What is clear, however, is that the wise men of Ben Siras did not hold any state-supporting positions in the narrower sense. In any case, she did not intend Ben Sira for that ... "

The importance that domestic and foreign trade had for Palestine in Hellenistic times does not come adequately into view in Ben Sira. His statements on the subject of trade are “undifferentiated, summary and distant, even downright negative.” Ben Sira stated that money and status belonged closely together ( Sir 13.23 EU ). He called for charity and urged his students to avoid corruption and dishonest business. No other group of people emphasizes otherness as strongly as the beggars: “Child, you shouldn't live a begging life, it is better to die than beg. A man who looks at someone else's table, whose life is not to be counted as life ... "( Sir 40.28 EU )

family

The family as such is not a topic in Ben Sira's textbook, only the relationship of the householder to individual family members: A son was seen as a possible rival, he had to be brought up strictly - ideally, the son would later act as a rejuvenated likeness of his father ( Sir 30, 4-5 EU ). For Ben Sira, a daughter was above all a burden and, in the event of her misconduct, a danger to his honor ( Sir 42.9–11 EU ); the goal was to marry them off well ( Sir 7,24-25 EU ). Ben Sira described, as Oda Wischmeyer points out, a rather small family; He was less interested in having children than in bringing up his offspring well. “Strictness, care, restraint and the assertion of paternal violence in one's own home as well as caution towards the world outside one's own home determine the advice of the Siraciden. This corresponds to the intensity of the relationships that the sage cultivates. These extend mainly to the son or to young men as students and to a few friends. ”Horsley explains Sirach's insistence on control and obedience with the relative powerlessness of the scribe, who was thus easily vulnerable in his honor. Misogyne top texts in Ben Sira are Sir 25.24–26 EU and Sir 42.13–14 EU Marböck comments: “Statements at the expense of individual personality and dignity of women are a restrictive attempt to defend traditional socio-religious values, but also those in the Mediterranean region to preserve the prevailing value system of honor and reputation of men in this area. "

theology

Ben Sira advocates consistent monotheism . He contrasted the God of Israel with the Hellenistic diversity of gods; even the designation of a single god as universal deity, as is customary in Hellenism, was not an option for him. As the creator of the world, God faces the world. On the subject of God's righteousness ( theodicy ), Ben Sira brought up the new idea that there are polar structures in creation ( Sir 33: 14–15 EU ).

For Ben Sira, man is indeed mortal, but in the image of God . An afterlife was speculated in Judaism in Ben Sira's time, but Ben Sira did not participate.

Because man is capable of knowledge and has real freedom of choice , he can deal with the Torah and act godly in the various situations in life. (Here is a motif that will become important during the Reformation era.)

The cosmic wisdom identified with the Torah or incarnating in the Torah was for Ben Sira the bridge between man and God. He was the first to identify wisdom with the Torah of Moses ( Sir 24.23 EU ). Man, takes that the self-praise of Wisdom ( Sir 24.1-29 EU is encouraged) from Hellenistic Isis - Aretalogien . It is characteristic how Isis turns to her admirer while advertising in the first person. "Areas that are assigned to the goddess in the Hellenistic Isis cult, such as creation, law, morals, science and religion, are applied to wisdom in Sir 24." This in the book composition (prelude to the second main part) as well as the central chapter in terms of content is not known in its Hebrew version so far, but only in Greek, Syrian and Latin translations. There are two comparable texts in the Tanakh in which wisdom is imagined as a feminine figure close to God: Hi 28.20–28 EU and Prov 8.22–31 EU . Sirach surpasses them both with the new idea that wisdom, after having traversed the cosmos, comes to rest on Zion : here the author links the motif of “God-given rest” ( Dtn 12.9–10 EU ) with the concept the sacred tent ( mishkan ) as the abode of God. This example shows how Ben Sira relates different religious subjects to one another. In chapter 24 he also uses metaphors from the plant world, which actually come from love poetry. The book aims at a wisdom eroticism, a love for the Torah: Sir 51 : 13-29 EU .

Research history

The research on the Sirach book can be divided into two parts. In a first phase, beginning in 1896, the research focused on textual criticism , the recovery of a Hebrew “original text”. It was not until the 1960s, also inspired by the Second Vatican Council , that scientific exegesis increasingly turned to the contents of the book.

Texts from the Sirach book

Cairo Geniza

From the prologue it was always known that the Sirach Book was originally written in Hebrew, but for around 700 years it was only known in translations, mainly into Greek, Latin and Syriac. It was a sensation when the first Hebrew texts were published: On May 13, 1896, Agnes Smith-Lewis announced to the public that she had acquired a sheet of an old manuscript in Palestine that Solomon Schechter recognized as the text of the Hebrew book Ben Sira have. Schechter published this text immediately. More text fragments emerged in quick succession, the common source being a repository for holy writings ( Geniza ) of the Ben Esra Synagogue in Cairo. The editions were tumbling, and experts were of the opinion that the whole Hebrew text would be known within a short time. The fragments obtained can be assigned to six manuscripts ( symbols : H A , H B , H C , H D , H E , H F ). They are dated to the 9th to 12th centuries AD. New Sirach text fragments from the holdings of the Cairo Geniza are still being published, most recently in 2007/08 and 2011 (H C , H D ).

In 1899, David Samuel Margoliouth hypothesized that the newly emerged fragments were not the ancient Hebrew text of Ben Sira, but a translation back from a Persian version into Hebrew. The discussion as to whether the newly edited manuscripts were dealing with an original Hebrew text (according to Schechter) or a back translation (according to Margoliouth) was very emotional. Schechter argued that Saadja Gaon knew the Hebrew Ben Sira text, that is, that it was still in circulation at the time the manuscripts were written. That Schechter was fundamentally right has been proven since the text discoveries by Qumran and Masada. The discussion as to whether some of the Sirach fragments from the Cairo Geniza might have been back-translated is still going on today; In the 1990s, a consensus emerged that it was original Hebrew. It is very unusual. Because other deutero-canonical writings also appear in Hebrew versions in Jewish manuscripts of the Middle Ages, but they are always back translations from Greek or Latin - with the exception of the Sirach Book.

Qumran

Hebrew texts from the Sirach Book have been found in two caves near Qumran. Both times the Bedouins were there sooner than the archaeologists, so the circumstances of the find are not documented.

There are two small related Sirach Hebrew text fragments from Cave 2, which were named 2Q18 when they were published in 1962. Although little text from Chapter 6 has survived, the matching text arrangement (in hemistiches ) here and in medieval Geniza texts was a strong argument that there was a connection between the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Cairo Geniza.

The Great Roll of Psalms (11QPs a ) from Cave 11, edited by James A. Sanders in 1962, is more interesting. In ancient times, the dumping in this cave was more careful, so that actual scrolls and not just fragments were preserved. 11QPs a is a Qumran composition of biblical and extra-biblical psalms, including a poetic text from the end of the Book of Sirach: Sir 51 : 13-30 EU . This section was already known in its Hebrew wording from the Geniza manuscript H B. The ancient Hebrew text version from the Qumran Psalm is very different. It is closer to the Greek text - only now did the exegetes recognize that it was a Hebrew poetry ( acrostic ) arranged according to the first letters . The medieval copyists had moved so far away from it that the acrostic was no longer recognizable. In research there is no consensus as to whether Sir 51: 13-30 EU was originally an independent work that was put into a new context by both Ben Sira and the compilers of the Psalms Scroll - or whether this section forms an integral part of the Book of Sirach .

Masada

The oldest Sirach manuscript was found on April 8, 1964 during a regular archaeological excavation of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem under the direction of Yigael Yadin in Masada .

During the Jewish War , the Masada fortress was held by the Zealots against the Roman army until AD 74. At that time, the Zealot families had set up apartments in the casemate walls. One of these quarters uncovered by the archaeologists was Casemate 1109: a room no more than 15 m long and 4 m wide. Ovens and small silos indicated their use for residential purposes. There was a wall niche in the northeast corner of the room. It was possibly the place where the Sirach scroll was kept, as it was not far from it in the rubble near the ground. Until it was found, it had been exposed to weather and animal damage for many centuries. It had disintegrated into 26 pieces of leather, two of which were relatively large. A dark coating had formed on the leather due to moisture, so that most of the writing was no longer legible with the naked eye. Infrared images made visible a Hebrew text that was written only two generations after the grandson's Greek translation. It provided evidence for the long-held suspicion that the grandson had often not understood the Hebrew text correctly and in other cases had difficulties with the translation.

Yadin published the text of Masada's Sirach Scroll within a year of the find. This edition was presented to the public on the occasion of the opening of the Shrine of the Book ( Israel Museum , Jerusalem) on April 20, 1965.

Hebrew back translation, mixed text or Greek Sirach book

In the place of the one author who wrote an original text to be determined, a large number of people have taken the place of more recent research who - in several languages, over several centuries - wrote the Sirach Book. For today's reader of the Sirach book, this means that it is quite obvious what Ben Sira thinks on various topics he has touched on. In this sense, the voice of the Jerusalem sage is clearly audible and the Book of Sirach is easy to read. But that changes as soon as you go into detail and take a closer look at a single metaphor or formulation. Translators into modern languages who address a larger audience and want to offer a catchy text in the target language run into considerable problems in view of the dense network of references between the different versions of the text: “How far should or can the text of a tradition be? Accept (with reasons yet to be found) as the normative text, to what extent can and should one mix the versions obtained in H, Γ and Syr [ie the Hebrew, Greek and Syrian text tradition] or select ... [one of them]? ”In theory there are three Basic choices: You can translate the GI version back into Hebrew, you can use the Hebrew fragments and the GI version to create a Hebrew- (Syrian) -Greek mixed text or just use the Greek text as a basis.

The first option was rarely chosen; Moshe Zvi Segal's reverse translation is interesting as the work of a connoisseur of Talmudic literature . This option has to struggle with the difficulty that the grandson translated relatively freely. The mixed text option and the option for the Greek text tradition of the book therefore compete.

The mixed text option was at times very attractive in the 20th century. This approach was recommended in the guidelines for interdenominational cooperation in the translation of the Bible agreed by the Bible Societies and the Secretariat for Christian Unity in the Vatican : It is advisable “to print the shorter text as it is in the most important Greek manuscripts, and taking into account the Hebrew and Syrian texts. The longer texts from other Greek and Latin manuscripts and possibly other Hebrew readings can, if necessary, be reproduced in footnotes. ”In the meantime, however, the conviction has gained acceptance that something artificial is created with this -“ a text version that has never existed in this way . "

Alternatively, you can also focus on the completely preserved Greek text. It is common practice to translate the Greek long text and indicate the excess compared to the GI version. This approach is favored today because it emphasizes the "weight and independence of a closed text version". However, this solution also has disadvantages: The entire Greek text tradition goes back to a single copy (hyparchetype) in which a page exchange between Sir 30.24 and Sir 37.1 took place. The consequence of this is that the content and count no longer match. This mishap is not noticed when reading it briefly, because the Sirach book as wisdom literature contains series of sentences on changing topics and the wrong order of the pages did not result in hard breaks. Since a scroll has no leaves, it must have been a codex , a book form that did not appear until the 1st century AD. "With this statement, however, the text-critical value of the entire Greek Sirach tradition is put into perspective, since it is ultimately based on only one text witness ..." This text witness is younger than the Hebrew fragments from Qumran and Masada.

Contents of the Sirach book

The prelude to content-oriented research on the Sirach book was Josef Haspecker's monograph God's fear in Jesus Sirach (1967). Fear of God, a personal, trusting relationship with God, is the educational goal of Ben Sira, even more important than the wisdom often mentioned in the book.

In the first phase, up to the mid-1970s, research mainly tried to clarify Ben Sira's relationship to Judaism on the one hand and Hellenism on the other. Martin Hengel only briefly dealt with the Sirach book, but designed a well-received model of the assignment of Judaism and Hellenism: he saw in Ben Sira's work the defense against Hellenism, which was the predominant educational power, in that the author identified wisdom and Torah, based on Isis- Aretalogies in Sir 24 connect them as a universal greatness with the particular faith of Israel, and in praise of the Fathers of Israel (Sir 44-50) try to show their superiority over Greek philosophy. Today Judaism and Hellenism are no longer seen as alternatives in the way Hengel did. Ben Sira could therefore not take a position outside of Hellenism; rather, he wrote a book for Jewish readers in a Hellenistic context. According to Johannes Marböck: Ben Sira takes elements of Hellenistic culture and integrates them, while at the same time presenting the Jewish religion in a contemporary form. Theophil Middendorp takes a similar approach in the 1973 monograph The Position of Jesus Ben Siras between Judaism and Hellenism . He defines the Sirach book more precisely as a school book that mediates between Hellenistic education and Jewish tradition.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, research has increasingly focused on Ben Sira's profession as a scribe, the assignment of wisdom and Torah, and references to ancient Egyptian wisdom literature. In Ben Sira as a scribe (1980), Helge Stadelmann analyzes the professional role of Ben Sira - on the one hand he defends priestly privileges, on the other hand he offers an education that is open to everyone, not just the priesthood. Was it possible that Ben Sira was a priest himself? Stadelmann affirms this: Since he lived on taxes as a priest, he had leisure for his studies and stood almost outside the social polarization of poor and rich, so that he more often took sides in favor of the poor, but lived in prosperity himself. Jack T. Sanders' study Ben Sira and demotic Wisdom (1983) was a corrective to the prevailing trend of understanding Ben Sira's work against the background of Hellenistic literature. The author could very well have known demotic wisdom writings from the Ptolemaic period.

Since the 1990s, the main focus has been on social issues that are discussed in the Sirach Book, such as the relationship between parents and children or Sirach's concept of friendship . With the exception of the friends David and Jonathan , the subject of friendship plays hardly a role in the Hebrew Bible. It was Ben Sira who related this important concept in Hellenism to the Jewish tradition. In 1995, a symposium in Salzburg was devoted to Ben Sira's friendship texts.

Bradley C. Gregory published a 2010 study of Ben Sira's property management, specifically his advice on loans, guarantees, and handouts. Against the background of Hellenistic and other early Jewish literature ( Book of Proverbs , Tobit Book ), Gregory makes the special profile of Ben Sira clear; for him, generosity is ethically motivated as an imitation of God ( imitatio Dei ).

Warren C. Trenchard identified Ben Sira in a monograph in 1982 as a misogynous author: he had a negative attitude towards women personally, he worked on traditions about women in a negative way and was more interested in "bad" than in "good" women. This Trenchard thesis has since been adopted many times, e. B. from Silvia Schroer . To classify Ben Sira's statements about women , the honor-shame model from cultural anthropology , which is represented by Bruce J. Malina and the Context Group , is often used . It refers to the ancient Mediterranean and assumes that there was a "moral division of labor" for men and women. Men competed for honor; they could gain or lose honor through their behavior. There was no more or less with women, only honorable and dishonorable women. The public also did not believe that women could independently protect their honor without male authority and control. The shame of a woman have abandoned their father or husband to ridicule. The honor-shame model is popular with experts and is seen as helpful, but critics point out that it levels out the differences between the various population groups in the Mediterranean region. In 2013, Teresa Ann Ellis questioned the applicability of the model to the Sirach book. In this linguistic study, Ellis focuses on the construction of gender in the Hebrew Sirach text and comes to the opposite conclusion: In contrast to the role models of classical antiquity and Hellenism, Ben Sira shows an appreciation of women and female sexuality. She justifies this, among other things, with the personified woman wisdom, to which an erotic metaphor refers.

Impact history

Ben Sira in rabbinical literature

There are parallels in rabbinic literature to sayings of Ben Sira, e.g. B. corresponds to Sir 7.17 EU the sentence attributed to Rabbi Levitas by Javne: "Be very, very humble, for the hope of man is worm." ( Mishnah Avot IV 4)

Ben Sira is mentioned by name only once in the time of the Tannaites ( Tosefta Jadajim II 13): the gospels and the books of the heretics , the "books (sic!) Of Ben Sira" and all books written later are not canonical. In contrast to the Gospels and Christian literature, the Sirach Book was apparently viewed as a Jewish book, but its canonicality was clearly denied.

In the period that followed the Amoraim can be a difference between the rabbis in Palestine and which find in Babylonia:

- The Palestinian Amorae knew the Hebrew Book of Sirach - and they mostly quoted it correctly, as a comparison with the surviving Hebrew fragments of Sirach shows. Usually Ben Sira was quoted as a person as if he were a rabbi saying something or on whose behalf something is being said. It seems that passages from the Sirach book influenced religious poetry ( piyutim ).

- The Babylonian Amorae initially knew nothing about Ben Sira and his book, nor did their Christian neighbors. That changed in the early 4th century: the Syrian translation of the Sirach Book came into circulation and was read as holy scripture by Afrahat , a Syrian church father. The discussion that has come down to us in the Babylonian Talmud (Shabbat 100b) is located in this historical context : Rabbi Joseph commented on the Christian use of the Book of Sirach as holy scripture. This made the book obsolete for Jews, but it was still acceptable to pass on Ben Sira's teaching orally. Rabbi Josef obviously knew the Hebrew Book of Sirach well, as he proved by a few quotations. This made him an exception among the Babylonian Cupids; Ben Sira was generally cited inaccurately, or some silly sayings were ascribed to him that were not even included in the book - all characteristics of oral tradition.

The alphabet of Ben Sira is an anonymous Jewish work that was created in the context of the Geonim in today's Iraq and has been handed down in several variants. The inconsistent text is organized around an alphabetical list of 22 Aramaic proverbs. As a foreword, a fantastically scandalous birth and childhood story of Ben Sira is told. That this is a satire on Christian birth and childhood stories of Jesus in the style of the Toledot Jeschu is less likely because of its origin in a Muslim country. In the last part of the book, Ben Sira appears at the court of Nebuchadnezzar, where he has to pass 22 exams. In the style of an aggadic midrash, the alphabet of Ben Sira satirizes texts from the Talmud and midrash. His "victims" are above all the serious legend of the saints of the prophet Jeremiah in Pesiqta Rabbati , on the other hand the type of ABC teacher ( Melamed ). The Alfabet of Ben Sira was read as a crude folk book in many Jewish communities in the Middle Ages, but was punished with disregard in the serious rabbinical discussion of that time - with the exception of the French Tosafist Rabbi Perez von Corbeil, who cited the work in the 13th century to declare artificial insemination to be halachic in a woman . This detail was received by Schulchan Aruch (Jore Dea 195.7).

The Sirach book in the old church

In the early church there were different opinions as to whether or not Jesus Sirach was part of the Old Testament. Regardless of this, the book was classified as a "script" that could be cited, with the individual authors showing varying degrees of interest in Sirach. What was quoted was hardly the theological statements of the work, but the kaleidoscope of practical advice and sentences. None of the early church authors wrote a commentary on the Sirach Book.

In his 39th Easter Letter (367 AD) Athanasius stated that the Old Testament comprised the 22 books of the Jewish canon. But he added that there were non-canonical writings, including Sirach, "which the fathers had read by those who, only recently members of the Church, wanted an introduction to the foundations of the doctrine of piety."

Among the church fathers, who often quoted Jesus Sirach and recognized him as the authoritative “scripture”, is John Chrysostom at the top with around 300 quotations in the east, and Ambrose of Milan in the Latin west .

Theodor von Mopsuestia, on the other hand, rejected Sirach. More consequential (in view of the Reformation) was Jerome's negative opinion , which did not prevent him from occasionally quoting the Sirach book, namely the GI version in his own translation from the Greek. He claimed to have seen the Hebrew Book of Sirach himself; but, as far as can be seen, he did not use it. Around the year 391, Jerome declared that Sirach was outside the canon and belonged to the Apocrypha . And a few years later it is said, “the Church does not accept the books of wisdom and J [esus] S [irach] any more than Judit, Tobias and the two Maccabees under the canonical scriptures, just read them for edification of the people ..., but not to reaffirm the authority of church doctrinal statements. "

Augustine, on the other hand, quoted very often from the Book of Sirach and counted it among the prophetic writings ( inter propheticos ).

From the christological to the mariological interpretation of wisdom

In early Christianity and in the early church, statements of the Old Testament about the wisdom of God were related to Jesus Christ (for example: 1 Cor 1.30 EU ). The prologue of the Gospel of John Joh 1,1–16 EU is suggested (according to Marböck) by Sir 24: It describes the path of the divine Logos from his departure from God via the cosmos to his dwelling in Israel and Jerusalem. Since the early Middle Ages , however, there has been an accommodation of Sir 24 and comparable texts on Mary, the Mother of God, or the Church ( Ecclesia ). Two feasts of Mary ( Assumption of the Virgin Mary and Immaculate Conception ) received readings from the chapter Sir 24.

In the encyclopedic work Liber Floridus ("Book of Flowers") by Lambert of St. Omer (1120), the author interpreted eight plant names that appear in Sir 24 as religious symbols that he placed in relation to the eight Beatitudes of the New Testament:

- Sir 24.13 EU Cedar ( cedrus ): humility ( humilitas ) of the poor before God ( pauperes spiritu );

- Sir 24.13 EU Cypress ( cypressus ): mild;

- Sir 24.14 EU palm ( palma ): grief;

- Sir 24,14 EU Rosenstock ( plantatio rosae ): bravery ( fortitudo ) of those who hunger and thirst for justice;

- Sir 24.14 EU olive tree ( oliva ): mercy;

- Sir 24.14 EU plane tree ( platanus ): purity of heart;

- Sir 24,16 EU Terebinth ( terebinthus ): Peacefulness;

- Sir 24.17 EU vine ( vitis ): Persecution for the sake of justice.

"Similar to the gemstones of the Apocalypse , the trees represent attitudes that lead to eternal bliss." These virtues are embodied by Mary herself and at the same time - taking up the promotional character of the wisdom speech in Sir 24 - recommended to the believers for imitation.

An example of artistic reception is the Bardi Altar by Sandro Botticelli (1485): Mary is enthroned in the center of the picture, about to offer the baby Jesus her breast. On either side of Mary are John the Baptist and the Apostle John . The painter thus depicts the encounter between Mary and two saints: a Sacra Conversazione . Foliage niches form the background against which vases with flowers and branches are placed. Six banners explain the plants through quotations from the mentioned chapter of the Sirach Book. Another banner quotes Hld 2.2 EU .

The meaning of Sir 24 for Mariology and especially for the dogma of the Immaculate Conception ( conceptio immaculata ) was implemented by Giovanni Bellini on the Frari triptych (dated 1488). The enthroned Mary is flanked on the two side panels by Saints Nicholas and Peter as well as Benedict and Mark . Nicholas expresses the basic attitude of a contemplative life with downcast eyes and closed book . Benedict, on the other hand, presents the viewer with the open Bible at Sir 24. It contrasts effectively with his black religious clothing and is highlighted “like a spotlight” by Bellini's lighting: “With a year-long turn of the head ... the founder of the order focuses on the viewer, as if to convince him of the validity of the conceptio immaculata using the Liber Ecclesiasticus ."

The invocation of Mary under this title in the Lauretanian litany is derived from the self-designation of wisdom as “mother of beautiful love” . It is an addition to the text of the G-II version:

"I am the mother of beautiful love and fear and knowledge and holy hope, but with all my children I give steady growth to those who are named by him."

This invocation was not part of the original text of the Lauretanian Litany; it is found for the first time in a rhyming litany of two Zurich manuscripts from the 15th century. "Theologically speaking, the invocation 'Mother of Beautiful Love' is a synonym for 'Bride of the Holy Spirit.'"

Since the ecclesiastical Catholic standard translation of 1980 followed the mixed text option, this verse was only included in a footnote despite its importance for the liturgy. The revised standard translation (2016), like the revised Luther Bible (2017) and the Zurich Bible (Apocrypha 2019), are based on the Septuagint text tradition; consequently the verse Sir 24:18 EU returned to the main text.

The miraculous image of Mary, Mother of Beautiful Love in Wessobrunn is a devotional image created by Innocent Metz from the early 18th century, which shows Mary with a wreath of flowers on her head as the bride of the Holy Spirit. It was adopted in several Madonna pictures in southern Bavaria.

Arguing with Sirach during the Reformation

With reference to the church teacher Hieronymus, Martin Luther established the principle that dogmatic propositions could not be based on the Apocrypha. He also included the Sirach book. The Swiss reformers also decided that the reasoning was the same. In Sirach's case, the following sentences were particularly interesting for the questions raised during the Reformation:

“He himself made man in the beginning and left him in the hand of his (own) will. If you want, you will keep the commandments ... He gave you fire and water; whatever you want, you will reach out your hand. Life and death stand before man, and that which he likes will be given to him. "

Erasmus of Rotterdam placed Sir 15:14 programmatically at the beginning of his work on human free will ( De libero arbitrio ). With the reply in De servo arbitrio , Luther attempted to wrest the Sirach quote from Erasmus and to interpret it in such a way that it did not refer to free will, but to man's mandate to rule over the earth ( Dominium terrae ). But that wasn't convincing. Erasmus and other opponents of Luther ( Johannes Cochläus , Johannes Eck and Alfonso de Castro ) had found an ally in Ben Sira against Luther's doctrine of unfree will. To consider his work to be apocryphal means to radically devalue this argument of the Old Believers: one can still deal with it, but does not have to do it:

“Then the adversaries also cite the book of Sirach, which we know to be of dubious authority ( dubiae autoritatis ). Well, we don't want to immediately reject it ( repudiare ), which we would justifiably be free to do. "

The phrase "of dubious authority" suggests that Calvin, as happened occasionally since the early Church, believed King Solomon to be the author of the Book of Sirach. Then he became increasingly concerned, and finally he rejected Solomon's authorship. In connection with Hieronymus and just like Luther, Calvin counted Jesus Sirach among the Apocrypha. Nonetheless, Calvin valued the Sirach book and considered the Sirach passage cited by the opponents not simply wrong, but rather in need of interpretation. The interpretation of an unclear passage in the Apocrypha was based on the clear biblical statements (the "undoubted word of God").

Canonization by the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (1546) unequivocally recognized the Book of Sirach as Holy Scripture, while in the churches that emerged from the Reformation it is considered apocryphal and the Orthodox churches do not take a common, clear position on this question. In contrast to the reformers, the council fathers put the definition of the canon at the top of all council resolutions and rejected any difference in rank between proto- and deutero-canonical books. But the Roman Catholic Church, according to Maurice Gilbert, did not specify in which language or in which text volume the Sirach book was canonical. On the one hand, the council referred to the Vulgate (translation of the G-II version), on the other hand, the Pope had been asked for a correct copy of the Septuagint from his library. The Codex Vaticanus was chosen for this purpose - to this day an excellent witness for the Greek short text, the GI version.

Jesus Sirach in the Luther Bible

“It is a useful book for the common man; because all his diligence is also to make a citizen or householder god-fearing, pious and wise, as he opposes God, God's word, priest, parents, wife, children, his own body, servants, estates, neighbors, friends, enemies, Authorities and everyone should behave; so that one could call it a book on domestic breeding ... "

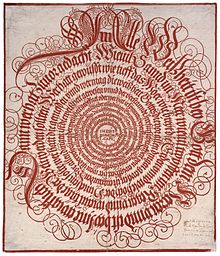

Martin Luther translated the Sirach book together with Philipp Melanchthon and Caspar Cruciger . The three Wittenberg translators used the Latin Vulgate, but also in sections the Greek Septuagint, without it being transparent which criteria were used. The Luther Bible went its own way in numbering the chapters and verses , so that it was difficult to find a text in it that was quoted from a non-Lutheran version of the Sirach Book. The Sirach book appeared as a separate print even before the entire Luther Bible was completed. This sold well. Twelve editions in Wittenberg from 1533 to 1545 indicate the popularity of the font. It served "also as a primer for elementary instruction, not only in German, but - in Greek and Latin versions - even for teaching in these two ancient languages."

Composers of the 17th century such as Michael Praetorius , Samuel Scheidt , Johann Hermann Schein , Johann Stobäus , Heinrich Schütz and Johann Pachelbel based their polyphonic settings on the text of Sir 50,22-24 LUT . They may have been inspired to do this by the description of the Jerusalem temple music in the same chapter of the Book of Sirach. Two chorales about this biblical text are contained in modern hymn books:

Everyday culture

The Swiss Idiotikon contains too Sirach the phrases i Sirach cho , in Sirach sī "quarreled". The verb sirache means “rant, curse, rage.” Jesus advises Sirach several times to avoid arguments. "Apparently the wisdom in the book of Jesus Sirach and above all the warning against quarrels were preached so often that the name Sirach became independent and since then can be used as a substitute for quarrel."

In the area of the Anglican Church , the chapter Sir 44 is traditionally presented at national donor commemorations, annual institutional celebrations and similar occasions. In the wording of the King James Bible, the opening clauses in particular have a certain meaning in everyday culture.

- Let Us Now Praise Famous Men ( Sir 44.1a EU ) is the title of a book by James Agee with photographs by Walker Evans on the life of impoverished farmers during the Great Depression .

- The fact that the quote from Sir 44.14 EU Their Name Liveth for Evermore can be read as an inscription on British war cemeteries goes back to a suggestion by Rudyard Kipling , who joined the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1917 . In front of the memorial stone with the same lettering on the British war cemetery Oosterbeek near Arnhem , a well-known photograph of the Beatles was taken in August 1960 . The detour to Oosterbeek on the way to Hamburg shows that the band members were still deeply affected by the Second World War due to their family history.

literature

Text output

- Pancratius C. Beentjes: The Book of Ben Sira in Hebrew. A Text Edition of all Extant Hebrew Manuscripts and a Synopsis of all Parallel Hebrew Ben Sira Texts (= Vetus Testamentum, Supplements. Volume 68). Brill, Leiden 1997, ISBN 978-90-04-27592-8 .

- Alfred Rahlfs , Robert Hanhart : Septuagint: Id Est Vetus Testamentum Graece Iuxta LXX Interpretes. German Bible Society, Stuttgart 2006. ISBN 978-3-438-05119-6 .

- Joseph Ziegler : Sapientia Iesu Filii Sirach. (= Septuagint: Vetus Testamentum Graecum . Volume 12/2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 3rd edition Göttingen 2016. ISBN 978-3-525-53419-9 .

- Wolfgang Kraus , Martin Karrer (Eds.): Septuagint German. The Greek Old Testament in German translation. German Bible Society, Stuttgart 2009. ISBN 978-3-438-05122-6 . (Scientific translation of the Sirach book by Eve-Marie Becker (Prolog, Sir 1–23 and 51) and Michael Reitemeyer (Sir 24–50). Obvious errors in the Greek text were not corrected according to the Hebrew fragments or the old translations, but rather they have been incorporated into the German translation; a footnote provides the relevant information.)

Tools

- Dominique Barthelémy , Otto Rickenbacher: Concordance on the Hebrew Sirach: With a Syrian-Hebrew index. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1973. ISBN 3-525-53536-8 .

- Friedrich Vinzenz Reiterer : Counting synopsis for the book Ben Sira. Created with the collaboration of Renate Egger-Wenzel , Ingrid Krammer, Petra Ritter-Müller and Lutz Schrader. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2003. ISBN 3-11-017520-7 .

Overview representations

- Maurice Gilbert: Jesus Sirach . In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 17, Anton Hiersemann Verlag, Stuttgart 1995, pp. 878-906.

- Johannes Marböck : The book Jesus Sirach. In: Christian Frevel (ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. Kohlhammer, 9th, updated edition Stuttgart 2016, ISBN 978-3-17-030351-5 , pp. 502-512.

- Johannes Marböck: Sirach / Sirachbuch. In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Volume 31, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, pp. 307-317. ISBN 3-11-016657-7 .

- Frank Ueberschaer : Sophia Sirach / Ben Sira / The Book of Jesus Sirach. In: Siegfried Kreuzer (Ed.): Handbuch zur Septuaginta / Handbook of the Septuagint LXX.H. Volume 1. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2016, ISBN 978-3-579-08100-7 , pp. 437-455.

- Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) . In: Jan Christian Gertz (Hrsg.): Basic information Old Testament. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 6th revised and expanded edition Göttingen 2019, ISBN 978-3-8252-5086-7 , pp. 555-567.

Comments

- Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23 (= Herder's Theological Commentary on the Old Testament ). Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010. ISBN 978-3-451-26832-8 .

- Georg Sauer: Jesus Sirach / Ben Sira (= The Old Testament German . Apocrypha. Volume 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000. ISBN 978-3-525-51401-6 .

- Josef Schreiner : Jesus Sirach 1–24 (= New Real Bible. Old Testament. Volume 38). Echter Verlag, Würzburg 2002. ISBN 978-3-429-00655-6 .

- Burkard M. Zapff : Jesus Sirach 25–51 (= New Real Bible. Old Testament. Volume 39). Echter Verlag, Würzburg 2010. ISBN 978-3-429-02358-4 .

Monographs, edited volumes, magazine articles

- Lindsey A. Askin: Scribal culture in Ben Sira (= Supplements to the Journal for the study of Judaism . Volume 184). Brill, Leiden / Boston 2018. ISBN 978-90-04-37285-6 . ( PDF )

- Pancratius C. Beentjes (Ed.): The Book of Ben Sira in Modern Research. Proceedings of the First International Ben Sira Conference, 28-31 July 1996 Soesterberg, Netherlands (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 255). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1997. ISBN 3-11-015673-3 .

- Maurice Gilbert: Methodological and hermeneutical trends in modern exegesis on the Book of Ben Sira . In: Angelo Passaro, Giuseppe Bellia (Ed.): The Wisdom of Ben Sira: Studies on Tradition, Redaction, and Theology (= Deuterocanonical and Cognate Literature Studies . Volume 1). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2008, pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-3-11-019499-9 .

- Matthew J. Goff: Hellenistic Instruction in Palestine and Egypt: Ben Sira and Papyrus Insinger . In: Journal for the Study of Judaism 33/2 (January 2005), pp. 147-172. ( PDF )

- Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea . Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville London 2007. ISBN 978-0-664-22991-7 .

- Jenny R. Labendz: The Book of Ben Sira in Rabbinic Literature. In: AJS Review 30/2 (November 2006), pp. 347-392. ( PDF )

- Friedrich Vinzenz Reiterer: Text and book Ben Sira in tradition and research. An introduction. In: Friedrich Vinzenz Reiterer, Nuria Calduch-Benages (ed.): Bibliography on Ben Sira (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 266). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998. pp. 1-42. ISBN 3-11-016136-2 .

- Gerhard Karner, Frank Ueberschaer, Burkard M. Zapff (eds.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book. SBL Press, Atlanta 2017. ISBN 978-1-62837-182-6 .

- Johannes Marböck: Wisdom in Transition: Investigations into the theology of wisdom with Ben Sira (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 272). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999. ISBN 3-11-016375-6 .

- Georg Sauer: Studies on Ben Sira . Edited and provided with a foreword by Siegfried Kreuzer . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013. ISBN 978-3-11-030032-1 .

- Helge Stadelmann: Ben Sira as a scribe. An investigation into the occupational profile of the pre-Maccabees Sofer taking into account his relationship to priesthood, prophet teaching and wisdom teaching. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1980, ISBN 978-3-16-143511-9 .

- Frank Ueberschaer: Wisdom from the encounter: Education according to the book Ben Sira . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004. ISBN 978-3-11-020064-5 .

- Werner Urbanz: "For everyone who is looking for education" (Sir 33:18). Aspects of early Jewish education in the book Jesus Sirach . In: Beatrice Wyss et al. (Ed.): Sophists in Hellenism and imperial times. Places, methods and persons of educational delivery . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2017, pp. 99–122. ISBN 978-3-16-154591-7 . ( PDF )

- Christian Wagner: The Septuagint Hapaxlegomena in the book Jesus Sirach. Studies on word choice and word formation with special consideration of the text-critical and translation-technical aspect (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 266). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1999 (Reprint 2012) ISBN 978-3-11-080045-6 .

- Markus Witte: Texts and contexts of the Sirach book: collected studies on Ben Sira and on early Jewish wisdom. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2015. ISBN 978-3-16-153905-3 .

Web links

- Friedrich Vinzenz Reiterer: Jesus Sirach. In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- The Book of Ben Sira, ספר בן סירא: Digital copies of the Hebrew Sirach fragments

- Sirach Synopsis project

Individual evidence

- ^ Codex Vaticanus and Septuagint edition by Rahlfs.

- ↑ Maurice Gilbert: Jesus Sirach. Stuttgart 1995, column 880.

- ↑ Hebrew שמעון בן ישוע בן אלעזר בן סירא Shimʿon ben Yeshuaʿ ben Elʿazar ben Ṣiraʾ .

- ↑ Ancient Greek Ἰησοῦς υἱὸς Σιραχ Ελεαζαρ ὁ Ἱεροσολυμίτης Iēsūs hyiòs Sirach Eleazar ho Hierosolymítēs .

- ↑ Hebrew יֵשׁוּעַ Yeshuaʿ , ancient Greek Ἰησοῦς Iēsūs .

- ↑ a b Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23. Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 50 f.

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and book Ben Sira in tradition and research. Berlin / New York 1998, p. 1 f.

- ↑ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Zählsynopse the book Ben Sira , Berlin / New York 2003, p 1 f.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: A sage at a turning point: Jesus Sirach - book, person and message. An attempt at an overall picture . In: Wisdom and Piety. Studies on the All Testament literature of the late period (= Austrian Biblical Studies. Volume 29). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2006, pp. 65–78, here p. 67.

- ↑ Angelika Berlejung : History and religious history of ancient Israel . In: Jan Christian Gertz (Hrsg.): Basic information Old Testament. 6th, revised and expanded edition. Göttingen 2019, pp. 59–192, here p. 180.

- ↑ a b Burkard M. Zapff: Jesus Sirach 25-51 , Würzburg 2010, p. 375.

- ^ Benedikt Eckhardt: Ethnos and rule. Political figurations of Judean identity by Antiochus III. to Herodes I , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2013, pp. 38–43. Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 44. The text of the Charter of Antiochus III. reports Flavius Josephus : Jewish antiquities , book 12, 138–144.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23 , Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 28 f.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 50 f.

- ^ Markus Witte: Key Aspects and Themes in Recent Scholarship on the Book of Ben Sira . In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 1–32, here p. 29.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book , Tübingen 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Markus Witte: Key Aspects and Themes in Recent Scholarship on the Book of Ben Sira . In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 1–32, here p. 16.

- ↑ Angelika Berlejung : History and religious history of ancient Israel . In: Jan Christian Gertz (Hrsg.): Basic information Old Testament. 6th, revised and expanded edition. Göttingen 2019, pp. 59–192, here p. 184.

- ^ Septuaginta Deutsch, Stuttgart 2009, p. 1091.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23 , Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 558. On the significance of the Sirach prologue for the creation of the Jewish canon Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran. The texts from the Dead Sea and ancient Judaism , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, p. 181.

- ↑ Georg Sauer: Ben Sira in Jerusalem and his grandson in Alexandria. In: Studien zu Ben Sira , Berlin / Boston 2013, pp. 25–34, here pp. 26 f., Frank Ueberschaer: Sophia Sirach / Ben Sira / Das Buch Jesus Sirach , Gütersloh 2016, p. 450.

- ↑ Maurice Gilbert: Methodological and hermeneutical trends in modern exegesis on the Book of Ben Sira , Berlin / New York 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ John Marböck: Ecclesiasticus 1-23 , Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 33

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and Book Ben Sira in Tradition and Research , Berlin / New York 1998, p. 15.

- ↑ Maurice Gilbert: Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 1995, Col. 885.

- ^ Daniel Stökl-Ben Ezra: Qumran. The texts from the Dead Sea and ancient Judaism , Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, p. 12 f. The letter of the Patriarch Timotheos is quoted by Stökl Ben Ezra from: Oskar Braun: A letter from the Catholicos Timotheos I on biblical studies of the 9th century . In: Oriens Christianus 1/1901, pp. 299-313.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Sirach / Sirachbuch , Berlin / New York 2000, p. 307. Maurice Gilbert: Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 1995, col. 886.

- ↑ Burkard M. Zapff: Some hermeneutical observations on the Syrian version of Sirach. In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 239–262, here p. 240.

- ↑ Burkard M. Zapff: Some hermeneutical observations on the Syrian version of Sirach. In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 239–262, here p. 261.

- ↑ Maurice Gilbert: Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 1995, Col. 881.

- ↑ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Zählsynopse the book Ben Sira , Berlin / New York 2003, p. 21

- ↑ Thomas Römer et al. (Ed.): Introduction to the Old Testament. The books of the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament scriptures of the Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches . TVZ Theologischer Verlag, Zurich 2013, p. 750 .

- ↑ a b Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 563.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Das Buch Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 2016, p. 505.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Das Buch Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 2016, p. 563 f.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23. Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 29.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Wisdom in Transition: Investigations into the theology of wisdom with Ben Sira. Berlin / New York 1999, p. 96.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23 , Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Werner Urbanz: "For everyone who is looking for education" , Tübingen 2017, p. 104.

- ↑ Werner Urbanz: "For everyone who is looking for education" , Tübingen 2017, p. 106.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Jesus Sirach 1–23. Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 30 f.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Texts and contexts of the Sirach book. Tübingen 2015, p. 10.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Key Aspects and Themes in Recent Scholarship on the Book of Ben Sira , pp. 20 f.

- ^ Septuaginta Deutsch , Stuttgart 2009, p. 1143.

- ↑ Lutz Schrader: Profession, work and leisure as fulfillment of meaning in Jesus Sirach . In: Renate Egger-Wenzel, Ingrid Krammer (ed.): The individual and his community at Ben Sira (= supplements to the journal for Old Testament science . Volume 270), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, p. 117– 150, here p. 125.

- ↑ John Marböck: Ecclesiasticus 1-23 , Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2010, p. 30

- ^ Siegfried Kreuzer: The socio-cultural background of the Sirach book . In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 33–52, here p. 45.

- ↑ Georg Sauer: Ben Sira in Jerusalem and his grandson in Alexandria. In: Studies on Ben Sira , Berlin / Boston 2013, pp. 25–34, here p. 29.

- ^ Frank Ueberschaer: Wisdom from the encounter , Berlin / New York 2004, p. 374 f.

- ↑ Oda Wischmeyer: The culture of the book Jesus Sirach (= supplements to the journal for the New Testament science and the news of the older church . Volume 77), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 96 f.

- ↑ Frank Ueberschaer: Wisdom from the encounter , Berlin / New York 2004, p. 176, note 53.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Oda Wischmeyer: The culture of the book Jesus Sirach (= supplements to the journal for New Testament science and the news of the older church . Volume 77), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 47.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Key Aspects and Themes in Recent Scholarship on the Book of Ben Sira , p. 21.

- ↑ Sophocles: King Oedipus , 1528-1530.

- ↑ Homer : Iliad 6.146-149.

- ↑ Otto Kaiser: Jesus Sirach: A Jewish wisdom teacher in Hellenistic times. In: Gerhard Karner et al. (Ed.): Texts and Contexts of the Book of Sirach / Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book . Atlanta 2017, pp. 53–70, here p. 57 f.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Wisdom in Transition: Investigations on wisdom theology with Ben Sira , Berlin / New York 1999, p. 170 f.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 56. Here Horsley adapts the model of agricultural societies from Gerhard Lenski .

- ↑ Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 567.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Frank Ueberschaer: Wisdom from the encounter , Berlin / New York 2004, p. 374.

- ↑ Oda Wischmeyer: The culture of the book Jesus Sirach (= supplements to the journal for the New Testament science and the news of the older church . Volume 77), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Samuel L. Adams: Poverty and Otherness in Second Temple Instructions. In: Daniel C. Harlow et al. (Ed.): The “Other” in Second Temple Judaism. Essays in Honor of John J. Collins . Eerdmans, Grand Rapids 2011, pp. 189–2003, here p. 195.

- ^ Septuaginta Deutsch , Stuttgart 2009, p. 1146.

- ↑ Bruce J. Malina: The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology , John Knox Press, 3rd, revised and expanded edition, Louisville 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Oda Wischmeyer: The culture of the book Jesus Sirach (= supplements to the journal for the New Testament science and the news of the older church . Volume 77), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ Oda Wischmeyer: The culture of the book Jesus Sirach (= supplements to the journal for the New Testament science and the news of the older church . Volume 77), Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 35.

- ^ Richard A. Horsley: Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea , Knoxville / London 2007, p. 68.

- ↑ John Marböck: Sirach / Sirachbuch , Berlin / New York 2000, p 312th

- ↑ a b c Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 566.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 566 f.

- ↑ Johannes Marböck: Das Buch Jesus Sirach , Stuttgart 2016, p. 511.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Jesus Sirach (Ben Sira) , Göttingen 2019, p. 559. Johannes Marböck: Wisdom in Transition: Studies on the Theology of Wisdom in Ben Sira , Berlin / New York 1999, p. 53 f.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Theologies in the book Jesus Sirach . In: Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book , Tübingen 2015, pp. 59–82, here p. 78.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Theologies in the book Jesus Sirach . In: Texts and Contexts of the Sirach Book , Tübingen 2015, pp. 59–82, here pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Frank Ueberschaer: Wisdom from the encounter , Berlin / New York 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ Agnes Smith-Lewis: Discovery of a Fragment of Ecclesiasticus in the Original Hebrew . In: Academy 49 (1896), p. 405.

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and Book Ben Sira in Tradition and Research , Berlin / New York 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Markus Witte: Key Aspects and Themes in Recent Scholarship on the Book of Ben Sira , p. 5.

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and Book Ben Sira in Tradition and Research , Berlin / New York 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and Book Ben Sira in Tradition and Research , Berlin / New York 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Friedrich V. Reiterer: Text and Book Ben Sira in Tradition and Research , Berlin / New York 1998, p. 25.

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran. The Dead Sea Texts and Ancient Judaism . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, p. 177.

- ↑ Maurice Baillet, Józef Tadeusz Milik, Roland de Vaux : Les 'Petits Grottes' de Qumrân. (Exploration de la falaise. Les grottes 2 Q, 3 Q, 5 Q, 6 Q, 7 Q à 10 Q. Le rouleau de cuivre) (= Discoveries in the Judaean Desert of Jordan . Volume 3), Oxford 1962, p. 75-77.

- ^ Corrado Martone: Ben Sira manuscripts from Qumran and Masada . In: Pancratius C. Beentjes: The Book of Ben Sira in Modern Research , pp. 81–94, here p. 83.

- ^ Daniel Stökl Ben Ezra: Qumran , Tübingen 2016, p. 124 f.

- ↑ James A. Sanders: The Psalms Scroll of Qumrân Cave 11 (11QPsa) (= Discoveries in the Judean Desert of Jordan . Volume 4). Clarendon Press, Oxford 1965.