Kitchenette house

The Einküchenhaus was a reform model of urban residential development in which a centrally managed commercial kitchens within a block of apartments the kitchens replaced the individual apartments. The concept went back to ideas of the women's rights activist and social democrat Lily Braun . With the basic idea of freeing women from housework , it was an explicit alternative to the establishment of isolated nuclear families in mass housing at the beginning of the 20th century . Single kitchen houses , sometimes also called central kitchen houses, found isolated and differently shaped implementations in various major European cities until the 1950s . As key works an idea of modern living, some of these buildings were for the nomination for the 2009 European Heritage (European Heritage Label) suggested explicitly shared as a distributed via various States network of European architecture .

The concept of the one-kitchen house

The basic idea behind the one - kitchen houses was to set up a central kitchen within an apartment building or complex with a simultaneous lack of private kitchens in the individual apartments . Instead, they were connected to the utilities, mostly located in the basement or on the ground floor, by a food elevator and an in-house telephone. In many cases, the equipment consisted of contemporary modern equipment. The communal kitchen was managed by paid staff, from whom meals and dishes could be ordered. Many of the houses also had central dining rooms; depending on the design concept, the apartments were also equipped with sideboards and simple gas stoves for emergencies.

In almost all of the built-in kitchenettes, there were also other community and service offers, such as roof terraces and laundry rooms , and in some cases also shops, libraries and kindergartens. The new home furnishings at the beginning of the 20th century included central heating , hot water supply , rubbish chutes and central vacuum cleaner systems with domestic pipe systems; the residents had various services available.

Originally conceived as a reform idea in workers' housing construction, in which the costs of community facilities would be offset by savings in the layout of the apartment and through central management , the implemented projects were based on different forms of ownership and organization. On both a private and a cooperative basis, one-kitchens offered the better-off bourgeoisie an alternative way of life in the middle of the city. In contrast to other reform concepts at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, such as the garden city movement , the cohesion of the residents was not brought about by screening , but by social exchange with the urban environment surrounding them.

The few actually completed kitchenettes were accompanied by an intense history of discourse both in politics and in architecture, but in practice these central economic projects usually failed after a short time. The apartments were then equipped with individual kitchens, some common rooms were used for other purposes, but some facilities, such as central laundry rooms, were also retained and, in particular, taken over by the cooperative housing scheme. Externally, they do not differ from other houses in the cityscape , so that they are largely regarded as forgotten, failed reform experiments.

Historical requirements

The Housing Question in the 19th Century

During the industrialization in the second half of the 19th century and the associated massive population growth in the cities, there was a radical break with the pre-industrial way of living. The rural population moving to the industrial centers left their large families' living and supply structures. In the cities they encountered increasing spatial, social and health problems, which were summarized under the term housing misery. City expansion and mass housing construction were regulated speculatively through the market , as the social upheavals were embedded in a liberalization of the economic order. The housing shortage and shortage of housing affected almost all city dwellers, but it seemed almost insoluble for poorly paid workers and their families who did not have permanent jobs and who often changed their place of work. The problems were the subject of constant criticism from the organizations of the labor movement , but also from socio-political associations, academics and housing reformers. The housing issue became one of the central political issues in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The basic problem was to reduce the discrepancy between housing costs and workers' incomes. If one reduces the aspects of the housing issue to a socialist and a bourgeois label, the positions differ from the outset. For the labor movement, the housing shortage was a class question that could not be solved under capitalism , but only with the appropriation of the means of production through collective forms of housing. This contrasted with the position of the housing and social reformers , who saw a moral, health and moral problem in housing misery. So should affordable and self-contained small flats to be created in accordance with civil model a family division of labor took place, after which the man of gainful employment ENGAGED and the woman for the housework had jurisdiction. The apartment also had the function of an educational program for the proletariat :

“One must get to the root of the evil and try to reconcile the miner with his rough, dull and difficult fate by making a home possible for him. But how can one demand that girls who have spent the most beautiful years of their development in the pits and who, with their male clothing, have also accepted the ruthlessness and brutality of the customs of the workers, can help found a domestic hearth and beautify it in such a way that it comes out of the dark lap? husband, father or brother returning to earth prefer to walk to his hut than to the inn? "

Solutions to the problem have been seen in the subsidization of the cost of capital in housing construction, the formation of cooperatives and rental- purchase strategies for homes . The Social Democrats, on the other hand, did not develop any living concepts of their own until well after the turn of the century, and rejected the kitchen-home models brought in by the women's movement and especially by Lily Braun. After the process of transformation into a democratic-socialist reform party , it followed the guidelines that had already been developed, modified by the demand for a state housing policy . In practice, the self-contained apartment prevailed for the small family, for the rural immigrants and the proletariat it was the visibly better form of living with its private sphere and self-determined equipment and organization.

The ideals of the utopian socialists

A model for the concept of one-kitchen houses was the utopian ideal of a community, which the early socialist social theorist Charles Fourier (1772–1837) had devised with the model of the Phalanstère . Fourier took the term from the Greek word phalanx ('combat unit') and the Latin monastery ('monastic community'), and it was precisely these economic and living communities that, contrary to the capitalist economic system, were supposed to overcome the division of labor and the division between production and consumption . The family households would be dissolved in communal houses with a collective infrastructure , there should be public kitchens, dining rooms, schools, ballrooms, recreation rooms, shops, libraries, music rooms and areas for children and the elderly. Equality for women and free sexuality were also considered in the models .

The French factory owner Jean-Baptiste Godin (1817–1889), also a supporter of early socialism, took up Fourier's design and, from 1859, realized a communal residential complex with the Familistère in the French community of Guise , next to his iron foundry and stove factory. It offered space for 1,500 people and consisted of three residential complexes, school buildings, a day nursery, a bathhouse and a theater. In addition there were the buildings of the Économat , a farm yard with kitchens, halls, restaurants, tavern, shops, pigsty and chicken yard. In contrast to Fourier, Godin did not strive to dissolve the family, as he emphasized with the name. In theory, women were equal to men, but since they were not trusted to do the hard and dirty work in the factory, many of them were left without work. As a result, individual kitchens were soon built into the apartments. In 1880 Godin transferred the entire complex, including the factory, to a cooperative that existed until 1960.

As early as 1816, the British entrepreneur Robert Owen (1771–1858) founded an educational institution for the improvement of his employees, the Institution for the Formation of Character, at his cotton mill in New Lanark , Scotland . He developed a model concept for industrial villages in which apartments were built without kitchens. Instead, the preparation of food and the food itself was organized centrally and collectively. In 1825 Owen sold the factory in Scotland and went to the United States to pursue his ideas more widely. In the state of Indiana he founded the settlement New Harmony , which offered space for about 1,000 residents. But the implementation failed due to both economic difficulties and personnel problems:

"In New Harmony a very colorful bunch of life reformers had gathered who instead of the ideal society created a 'discussion club' and soon left it."

Just three years later, Owen sold the settlement again. Opponents of the early socialist utopias saw the non-feasibility confirmed. Karl Marx analyzed the failure of the early socialist systems as not radical enough and at the same time too radical, because they called for the leap into an ideal final state, but believed this to be insular rather than societal as a whole, they “see no historical self-activity on the side of the proletariat, none of them peculiar political movement. "

The collectivization of housekeeping

Despite their failure, the early socialists had a considerable effect on the concepts of utopian settlements with centralized housekeeping that emerged from the middle of the 19th century and the attempts to implement them. In the USA and in Europe a network of various reformist and revolutionary directions developed, which aimed to reorient the division of labor, housekeeping and forms of living. These included representatives of the labor movement , the socialist and bourgeois women's movement in Germany, the anarchists , the feminists and the settlement movement in the USA, supporters of the architectural reform and the garden city movement in Great Britain and Germany.

In Boston , the feminist Melusina Fay Peirce (1836–1923) planned a housewives and production cooperative from 1868 onwards. She designed both the structural and the conceptual backgrounds and coined the term cooperative housekeeping for her system . In a community of 36 houses grouped around a courtyard based on neighborhood help, paid services such as cooking, washing and sewing were to be offered in a central workplace, and a communal kitchen was to be set up. The project soon failed due to resistance from the husbands of the women involved. Peirce further developed her experience and knowledge and in 1884 published the work Co-operative Housekeeping: How not to do it and How to do it .

The concept of the household cooperative was taken up by the feminist writer Marie Stevens Howland (1836–1921) and further developed by Mary Coleman Stuckert around 1890, who tried to establish a model of urban row houses in Denver with central common rooms, central kitchen and cooperative childcare. The architect Alice Constance Austin (1868 - unknown) also took inspiration from Peirce when, starting in 1910 in Palmdale , California , with the Llano del Rio project, she designed a complete urban plan on a cooperative basis with centralized housekeeping. The commune existed from 1915 to 1918. The American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) was also credited with having an impact on the European single-storey kitchen movement. Around 1900 she was full of ideas for her radical concepts of the renewal of gender relations, family and household in both theoretical treatises and novels described.

The first German, written reflections on collective housework can be found in the work of the women's rights activist Hedwig Dohm (1831-1919). In her publication The Jesuitism in the Household of 1873, she stated that the domestic economy was losing more and more of its content due to the historical development of industrialization and the division of labor and that the tendency towards centralization was :

"The time is approaching when the hearth fire will go out in the middle and lower classes, only to blaze brighter in the splendid public kitchens"

Even August Bebel outlined in his as a classic of emancipation theory designated, 1878 published magazine The Woman and Socialism a picture of society in which dissolved the household, food preparation, procurement of clothing and education of children in collective institutions outside organized by apartments and the great Waste of time, energy, heating and lighting materials and food should be put to an end.

“For millions of women, the private kitchen is one of the most exhausting, time-consuming and wasteful establishments, in which they lose health and good humor and which is an object of daily concern, especially when, as with most families, resources are the most scarce. The elimination of the private kitchen will be a salvation for countless women. "

Another father of the idea of the central budget is the Russian anarchist Pyotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin . In the history of the discourse of the one-kitchen houses, references to Kropotkin have been made over decades in various treatises, including by Lily Braun and Henry van de Velde . However, this background is often not named in order to cover up “any connection with the unrefined past of the one-kitchens”. It is primarily Kropotkin's memorable criticism of the single household that is widely cited:

“There are certainly 20 million Americans between noon and 2 a.m. and just as many English people who all eat roast beef or mutton, pork, potatoes and vegetables. And 8 million ovens burn for 2 to 3 hours to fry all the meat and cook the vegetables, 8 million women spend time preparing the meals, which all together may only consist of 10 different dishes. [...] Liberating women doesn't just mean opening the gates to the university, the court of justice or parliament. [...] Rather, freeing the woman means freeing her from the brutal work on the stove and washing tub, means setting up institutions that allow her to raise her children if she likes and to take part in social life. "

Kropotkin's influence arose not only from his theoretical elaborations, but also from his role as a mediator in various circles. He was a frequent guest in the Chicago Hull House of Jane Addams , had contacts with English art reformers, there he met Lilly Braun, the German Garden City Society and had considerable influence on Ebenezer Howard , the founder of the Letchworth Garden City .

The influence of the Hull House Chicago

The Hull House in Chicago , which was founded in 1889 by Jane Addams (1860–1935) and Ellen Gates Starr (1859–1940) and co-founded the American settlement movement , had a particular influence on the concepts of the one-kitchen house . It is one of the first community work institutions and was located in the middle of an immigrant quarter. From here, both immediate help and cultural education were offered to the immigrants and refugees living in the neighborhood. At the same time, it was a research center for social issues, on the basis of which women in particular called for socio-political reforms. In addition to social and community work, the house was used as accommodation for both female workers and professional intellectuals, mostly immigrants . With the aim of improving the living conditions of women, a central kitchen was set up, from which the approximately 50 residents as well as people from the neighborhood were supplied. The women had the choice of ordering food in their apartments or in the communal dining room. This was both a meeting point and starting point for a wide range of cultural and political activities.

The commitment of the women included the struggle for better working conditions and regular wages as well as the demands for the introduction of compulsory schooling for children, effective child protection and the introduction of women's suffrage . The offers of help were understood as helping people to help themselves on the basis of mutual learning, which was particularly enriched by the different origins and cultures of women. The water supply through house pipes and the garbage disposal scheme initiated by Jane Addams could be seen as a significant relief in everyday life, not only in Hull House, but in the entire district . After the founder's death in 1935, the project was continued as the Jane Addams Hull House Association , and since 1962 it has been the umbrella organization for several community houses in Chicago. The original building is used as a social work college by the University of Illinois at Chicago .

Discourse history - housing reform and women's work

Lily Braun (1865–1916), who was seen as a mediator between the socialist and the bourgeois women's movement, introduced her ideas about the centralization of housekeeping and cooperatively organized kitchenettes in lectures and speeches from the end of the 19th century . In doing so, she considered both the situation of proletarian women, who were forced to work outside the home as a result of industrialization, as well as that of bourgeois women who sought access to gainful employment. Economic co-operatives are one of the foundations for the liberation of women, for, she wrote, quoting Kropotkin, “Liberating her from the stove and the washing tub means establishing institutions which allow her to raise her children and take part in social life. "

Lily Braun's model of the kitchen-house

In 1901, Lily Braun published Women's Work and Housekeeping , in which she sketched her model of the one-kitchen house. In her basic assumptions she relied on August Bebel's remarks on the industrialization of reproductive work , on Kropotkin's criticism of the individual household and on the example of the Hull House in Chicago. Specifically, Lily Braun imagined a complex of houses in the middle of a garden with 50 to 60 apartments, each of which instead of a kitchen only has a small room with a food elevator and a gas cooker for emergencies:

“Instead of the 50-60 kitchens, in which an equal number of women tend to work, there is a central kitchen on the ground floor, which is equipped with all modern, labor-saving machines. There are already washing machines that clean and dry twenty dozen plates and bowls in three minutes! "

The central kitchen should also include pantries and laundry rooms with automatic washing machines. Depending on the inclination, the meal would be eaten in one's own apartment or in a shared dining room, which could also serve as a meeting room and playroom for children. Housekeeping should be under the direction of a paid housekeeper, assisted by one or two kitchen maids.

“The apartments are heated by central heating, so that 50 stoves are replaced by one. During the working hours of the mothers, the children play, be it in the hall or in the garden, where gymnastic equipment and piles of sand provide activities for all age groups, under the supervision of the guard. In the evenings, when the mother has put her to sleep and the parents want to chat or read with friends, they go down to the common rooms, where they don't have to buy the entertainment by drinking alcohol if they don't feel like it. "

The organization and financing should be ensured through cooperatives and the workers' insurance fund . Braun calculated that the effort would also be possible for working-class families, as the savings from the elimination of the individual kitchen, both in terms of rent and meals, could flow into the financing of the central kitchen and common rooms.

Lily Braun saw the political and social impact of her concept as significant in several ways. It would solve the housing problems of the proletarians, the liberation of women from housework would generally promote women's emancipation and, as a comprehensive family and life reform, the collective economic management would enable a family life free of housework. In addition, with this model a nutritional reform would be possible, which would end the “harmful dilettantism in the kitchen” and ensure a balanced diet, and finally it would include an upbringing and educational reform , the upbringing of children would be improved by trained staff:

"Not only would they be protected from the influence of the street and the sad precociousness of the city children, they would also learn to develop the spirit of brotherhood in themselves early on."

But not only for the proletarian women, but also for the families of the bourgeois circles, the model of the kitchen house offers solutions. The problem of housewives and servants could be solved through the professionalization of housework and homework.

The criticism of social democracy

Lily Braun's essay aroused many contradictions, her model of the kitchen house was referred to in the press as "future carnickel stable, barracks mass feeding and nationalized maternal joys". Within the Social Democrats, the proposal intervened in two controversial fundamental debates, in addition to that of the housing reform, that of occupational safety , which was directly linked to the question of the employment of women. In continuation of August Bebel's theories about women's emancipation , Clara Zetkin had formulated that disadvantage should not only be understood as a biological or legal problem, but above all as an economic problem, with the consequence of the demand for the right to work for women. This view was not unreservedly shared within the SPD, especially male comrades feared competition from the expansion of the industrial reserve army and the associated wage depressions. Another counter-argument was concerns about the destructive consequences of women's work for the physical health of women and families. The solution to this controversial problem, like the housing question, had been postponed to an unknown future which could only be found after the means of production had been socialized . The SPD thus made a clear distinction from the "headbirths" of the utopian socialists. Braun's model of the Einküchehaus, however, brings out the "utopianism of the 19th century that has been overcome" in order to "spin out the recipes for the cookshop of the future".

The social democratic women's movement also rejected the idea. Clara Zetkin subjected the proposal to a comprehensive and devastating criticism in several articles in the social democratic women's magazine Die Equality : The centralized housekeeping is not feasible for both mass workers and skilled workers, because their working conditions are subject to capitalist economic fluctuations and cannot be financially committed in the long term . If at all, then the model is only materially possible for an upper class of workers, but in these family relationships the women are precisely not employed. Since the kitchen house is not affordable for the working women of the poorer households, the prerequisites of the model cancel itself out. In addition, the housekeeper and kitchen maid employed there would be exploited in the central kitchen, especially since the staffing requirements were set far too low in the calculation. From all this it becomes clear once again that a household cooperative can only be an achievement of realized socialism. Comrade Braun's proposal aroused false hopes and meant "to paralyze the working class in its energy instead of strengthening it."

From 1905, a position formulated by Edmund Fischer prevailed within the Social Democrats , according to which the workers' movement should also demand the “return of all women to the house”. State kitchens and housekeeping cooperatives remained a utopian dream: "The so-called women's emancipation opposes female nature and human nature in general, is unnatural and therefore impracticable." In retrospect, this "patriarchal solution" is often seen as a symptom of the decline of the offensive women's movement within the SPD viewed. Associated with this was the final rejection of alternative living culture that would have freed women from housework.

The criticism of the women's movement

The associations of the women's movement, united in the Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine (BDF) from 1893, mainly dealt with questions of education and employment until the end of the 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, the discussion took into account the changed social conditions, the opposing pair of work and celibacy on the one hand, lifelong housewife-only existence and marriage on the other hand, gave way to the growing problem of coordinating housework and gainful employment. The position of women in families became the central question. In this discussion, Maria Lischnewska , who was assigned to the radical wing , took up Lily Braun's idea of the Einküchehaus, she saw the work of women outside the home as the basis of a partnership marriage that should be striven for, only women freed from housework and economic dependency could be wife and mother, private housework as well as ineffective private households should be abolished.

Käthe Schirmacher took a contrary position to Lischnewska by viewing housework as socially necessary, productive professional work and demanding its economic, legal and social recognition and remuneration. Also Elly Heuss-Knapp declined to "socialist solution" to the issue of women , and turned against the Einküchenhauslösung, although they welcomed the technical progress and improved infrastructure in the household. However, this would not have an impact on the reduction of housework, since the emotional and mental strain on the housewife would increase. Such services, however, could not be provided either through the market or on a cooperative basis. In this sense, the majority of BDF women rejected the Einküchehaus. More promising in the debate about the duplication of work for women was an orientation towards the systematization of work in individual households and their rationalization through technical innovations. A part of the women's movement turned to organizing and training housewives.

First attempts at realization

Despite the vehement criticism and rejection, Lily Braun founded a household cooperative in 1903 in order to realize her idea of a single kitchen. The architect Kurt Berndt designed a corresponding house for Olivaer Platz in Berlin-Wilmersdorf , in which “bright, airy, simple apartments of any size with bathroom, gas cooking facilities, central heating, gas and electric lighting and passenger lifts in the equally equipped front and garden shed ”were provided. However, the project had to be abandoned as early as 1904 due to a lack of support and funding. At that time, none of the workers' organizations wanted to experiment with a public economy model and expose themselves to the charge of reformism. In the period that followed, it was the private sector that took up the idea and implemented the first single-kitchen houses in Europe.

Copenhagen 1903

The Service House in Copenhagen , which the former school director Otto Fick had built in 1903 as the client, is considered the first European one-kitchen facility. It was referred to as a "small-scale social event", was set up for working, married women and organized as a private company, in which both tenants and staff participated through contributions and, according to the annual balance sheet, correspondingly in the profits. The five-storey tenement house with three and four-room apartments, each without a kitchen, had central heating, hot water pipes and a central vacuum cleaner. Electrically operated dining elevators led from the central kitchen in the basement to serving rooms in the apartments, where they were hidden behind wallpaper doors. A kitchen manager, five assistants and a machinist and stoker were employed in the kitchen.

The construction was received with interest by the German trade press. The Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung published an extensive description of the furnishings and functionality in 1907 and stated emphatically: "The apartments are completely separated from one another, [...] so that the self-contained little world of family life remains untouched." The cultural magazine Die Umschau published in the same year an enthusiastic report:

“What we have in common is that all household work is centralized, so that the individual takes care of cleaning, air, light, warmth and food with all their trimmings, from shopping, lighting the fire, cooking, serving, washing up etc. completely is relieved. [...] The central housekeeping is the realized little table set you up. The happy residents get up: breakfast is here. "

The central kitchen facility in Copenhagen existed until 1942.

Stockholm 1906

Following the example of the Copenhagen Service House, the architects Georg Hagström and Fritiof Ekman built the Hemgården Centralkök complex in Stockholm- Östermalm in 1906. It consisted of sixty two to five room apartments and a central kitchen and bakery on the ground floor. The food was supplied via dining elevators, and there was also a connection to the service facilities via an in-house telephone. The service included a laundry, an apartment cleaning service, a shoe shine and a central post office. Servant rooms were set up for the employed staff. The house was considered an institution for well-off families who shared the servants under the motto "collectives the maid" . The kitchen house existed until 1918, then modern kitchens were built into the apartments and the common rooms were converted into party and hobby rooms.

Berlin 1908 and 1909

In 1907, the Zentralstelle für Einküchehäuser GmbH was founded in Berlin, from which the Einküchenhaus-Gesellschaft der Berliner Vororte mbH (EKBV) split off a year later . Their program was designed to advance the establishment of domestic central economic systems. To this end, in 1908 the society published a brochure entitled The Einküchehaus and Its Realization as a Path to a New Home Culture . In it, she demonstrated that these types of buildings should enable tenants to adopt a new way of living and solve social conflicts. The previous debate about Lily Braun's idea was explicitly taken up, but at the same time it was differentiated from attempted cooperative solutions. The technification and centralization of economically backward households can only be achieved through a formally capitalist way of organization. The company presented calculations according to which life in the kitchen is no more expensive than in a normal apartment building, “not counting the great ideal values that are gained.” Addressed were “mainly the members of the so-called independent professions, who are then longing to get out of the housing inhumanity, out of the servants' calamity, or where women want to be free for their own professional activity, mostly in the intellectual or artistic field. In addition, the aim was to have its own food and agricultural goods production for the central economic system , which should be connected to the kitchen houses like a trust .

From October 1, 1908, the first Berliner Einküchehaus, built by the architect Curt Jähler, was available on Lietzensee in Charlottenburg at Kuno-Fischer-Strasse 13. It was a five-storey residential building with a front building and a small front garden, two side wings and a transverse building. It was equipped with central heating and hot water, and the two to five-room apartments had bathrooms, dressing rooms with dining elevators and house telephones. The central kitchen was in the basement and existed until 1913. It was reported that living in this house was 15 percent more expensive for an average family than with conventional management, but the circles that could afford these costs were already out For reasons of prestige, do not do without a maid.

On April 1, 1909, the kitchen houses in Lichterfelde-West were completed, and the architect Hermann Muthesius could be won over to build them. These were two free-standing three-storey rental houses, a corner house at Potsdamer Strasse 59 (today Unter den Eichen and Reichensteiner Weg) with an L-shaped floor plan, in which exclusively three-room apartments were laid out, and a rectangular house across Ziethenstrasse (today Reichensteiner Weg ) with two- to four-room apartments. Compared to the house on Lietzensee, the concept had been modified with a “richer cultural program”. Both houses had a central kitchen in the basement, from which food elevators transported meals to the apartments. There was no common dining room. Instead, roof terraces were used jointly and a kindergarten was connected. The apartments had emergency kitchens equipped with gas stoves, hot water pipes and house phones. A spacious plot of land and front gardens surrounded the entire complex. The central kitchen had to be given up in 1915, the houses were demolished in 1969/1970 as the street Unter den Eichen was widened.

Also on April 1, 1909, were ready Einküchenhäuser Friedenau in Wilhelmshöherstraße 17-20. It is a building complex designed by the architect Albert Gessner and made up of three houses, two of which are built symmetrically around a street courtyard with a covered garden hall, and the third adjoins the street. They are plastered buildings with hipped roofs, arcades, loggias and balconies that are based on the country house style . The houses were equipped with partly open, partly covered roof terraces and connected shower rooms, a gym with equipment, a storage room for furniture, moth chambers, bicycle rooms, darkrooms for photo work, laundry rooms, drying floors, ironing rooms and a central vacuum system. The central kitchen was in the basement of house no. 18/19, the food supply was provided by a total of nine dining elevators, which in turn were connected to a track system in the basement rooms. In addition, a kindergarten was set up, which was led by a reform pedagogue . In 1917/1918 the central kitchen had to be given up.

The houses on Wilhelmshöher Strasse are under monument protection . They are also mentioned as historical buildings because four members of the Red Orchestra resistance group lived here in the 1930s and 1940s until their arrest , in No. 17 Erika Brockdorff and her husband Cay Brockdorff , in No. 19 Adam Kuckhoff and his wife Greta Kuckhoff .

Memorial plaque for

Adam KuckhoffStumbling block for

Erika Brockdorff

Although the kitchenettes were very well received and the apartments were already firmly rented before completion, the company failed. The Einküchehaus company filed for bankruptcy in May 1909 . Organizational resistance and lack of capital are given as reasons. The central kitchens were maintained by the residents during a transitional period in cooperative self-help. The houses were positively received by the architect Stefan Doernberg, who published an essay on the kitchen house problem in 1911. He found that the business was profitable and that the attempt with “highly educated tenants with few children under expert guidance” had been successful on a capitalist basis. He concluded with the request that his fellow architects recognize the social and economic importance of their profession and take similar action.

Discourse history - public housing

"The thrones may have been overturned, but the old spirit is tenaciously rooted in the whole country"

After the First World War, shortages and shortages also determined the building policy, and the elimination of the mass housing deprivation was seen as an urgent task. The efforts to socialize or lower land prices , after the housing stock was taken over by the municipal or cooperative administrations, failed due to the fragile political conditions of the young Weimar Republic . Strategies for solving the problem of housing shortages were seen primarily in the rationalization of housing construction. The avant-garde architects opposed the reform programs and aimed at building a new popular housing scheme . But this remained stuck in theory and in numerous brochures, guidelines and statements until around 1924, while the old institutions of housing construction were already laying down the future policy of construction in the schemes of small houses and apartments in the countryside . Nevertheless, the single-kitchen model found its way into the contributions of social scientists and architects, especially from the pointed point of view of frugality.

Economics as an economic model

In 1919, Claire Richter, who holds a PhD in economics , published a historically elaborated study entitled Das Ökonomiat. Housekeeping as an end in itself . She used the term Ökonomiat to describe the model of the kitchen- house to emphasize its importance as an economic form. After a comprehensive presentation of the history of the central house economy, from Fourier to the present, she dealt with the economic benefits of female labor. It documented the enormous waste that private households in all social classes caused and that had to be stopped in the face of economic crises. She saw the centralization of housekeeping as a practicable way to save means and resources ; its character as an end in itself distinguishes it from all “institutional large households such as educational establishments and hospitals, old people's homes and poor houses”. With her writing she turned to the institutions of the housing reform in order to create a "subjective insight among the objectively affected reformers and entrepreneurs".

In 1921, Claire Richter founded the Lankwitz Association for the non-profit kitchen industry together with the social democratic women's rights activist Wally Zepler and the architect Robert Adolph , which campaigned for the establishment of kitchenettes on both a political and practical level. The concern found support among others from the Social Democratic Reichstag member Marie Juchacz . In October 1921 the association organized a rally in Berlin under the motto Social Kitchen Management - a demand for time and passed a resolution calling for the construction of non-profit kitchen houses as part of state housing. It stated

"[...] that the rational housekeeping within the framework of the non-profit kitchen economy is suitable for making the situation of women much easier. [...] Through the economic organization of domestic consumption on the one hand and the disproportionately higher utilization of the buildings for residential purposes on the other hand, it is able to make the current national and private economic restrictions bearable. "

The association also worked out a project for a site at Lankwitz City Park , in which the individual kitchens for 42 single-family houses were to be replaced by a central kitchen and a horizontal hanging transport system was to establish the connections. The organization of both the administration and the management of the kitchen was intended as a cooperative. This was the first single-family kitchen house model. It was not carried out, the reasons for this are not documented.

Architecture reform concepts

The model of the kitchen house only found its way into the strategies of urban planning of the 1920s, while the establishment of extensive infrastructures such as washhouses and shops progressed in housing development. The architects Peter Behrens and Heinrich de Fries found that, in addition to the structural rationality, the “rationality of the organization of community life” can best be realized in the system of the kitchen houses, but this idea was not implemented by them. Hermann Muthesius, who built the corresponding building in Berlin-Lichterfelde for the Einküchehaus-Gesellschaft der Berliner Vororte in 1908, now rejects the idea as a stopgap measure. The Austrian architect Oskar Wlach campaigned for the realization of single-kitchen houses. He saw in this the development of a new form of living that lies between the individual economy in a tenement house and the communal care in home accommodation: "This middle type has to combine the individualization in the own home with the economy of a standardized management and the acceptability of common daydreams." Henry van as well de Velde was a proponent of the central kitchen, architecturally it was anyway in the typological context of the urban apartment building, since its appearance was not influenced by the kitchen. But the kitchen house carries the germ of a more complete community in itself, "because we will not be satisfied with the house for long, in which only the kitchen is shared".

The architect and town planner Fritz Schumacher , building director from 1908 and chief building director from 1923 to 1933 in Hamburg, had already dealt intensively with the pros and cons of the kitchen house in 1909. He saw in this the possibility of progress in urban culture and in particular for women's emancipation efforts. His advocating arguments were the potential for savings in the room design, the promotion of intellectual interests of the women who were relieved of the small work, the liberation of the cooking profession from the servant character and the improvement of the food culture by specialists. As counter-arguments, he cited the loss of individuality, the loss of material and ideal support in the household, especially when the woman is not employed, and the increasing devaluation of the home. The somewhat anecdotal remark of Schumacher has also been handed down that it is to be regretted "the loss of the privilege of some house owners to have a special talent in the house with their wife". In 1921, Schumacher tried to implement his ideas of single-kitchen houses when building the Dulsberg housing estate in Hamburg, but failed due to resistance from the Senate .

The rationalization of housekeeping

From the mid-1920s, the discussion about the kitchen house was caught up with the rationalization of individual households and, in particular, the standardization of kitchens. A great success of the women's movement was the direct involvement of women's organizations in housing construction institutions. One of the most effective projects of the time was the Reich Research Society for Economic Efficiency in Building and Housing , initiated by Marie-Elisabeth Lüders , a member of the Reichstag . Experimental settlements of the classical modern age like Stuttgart-Weißenhof , Dessau-Törten and Frankfurt-Praunheim , which were examined under aspects of housekeeping and family suitability by architects, engineers and representatives of housewives' associations, were funded. The "liberation of women from kitchen stink" shifted to the design of modern kitchens according to the principles of rational housekeeping. The floor plan and furnishings were chosen from the point of view of smooth workflows; the original type is the Frankfurt kitchen developed in 1926 by the Viennese architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky .

Schütte-Lihotzky explained the strengths of the rationalization of individual households compared to the centralization of housekeeping in an essay from 1927: The concept of the kitchen house suffers from the fact that a stable standard of living is a prerequisite for the residents, since the financing shares for the central kitchen, central heating and other communal facilities must be raised under all circumstances, but is not guaranteed by those who can become unemployed within a short period of time.

"After we realize that the kitchen house is out of the question for a very large part of the population, we have to do everything we can to reform the individual household and relieve the woman of all unnecessary work."

The reorientation to the rationalization concept happened comprehensively and quickly, the standardized kitchen not only had the advantage of optimized work processes, which enabled housekeeping according to economic principles, but could also be implemented cost-effectively in mass construction. The model of the kitchen house was inferior to this concept and was considered a failure in both cooperative and mass housing construction. “What we have come to know as social life and social space in the courtyards, galleries, residents' assemblies, dining and reading rooms of the kitchenettes has disappeared in the assembly chains of the linear structure and in the (higher-level) functionality of the form of the standard apartment. This social life now falls under waste. "

Cooperative kitchenettes

Letchworth 1909

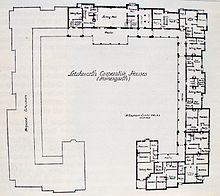

The garden city movement was both a parallel and a counter-concept to the urban one-kitchens, in which it sought the “ideal community” outside the cities. Both reform concepts have in common the view of architecture: a differently built environment will shape different social behavior. But in contrast to the goal of creating a home within the garden city, the one-kitchen model opposed the creation of individual property in small houses. Nevertheless, Ebenezer Howard planned to build a single-kitchen complex within Letchworth Garden City , the first garden city to be realized in Europe. Under the direction of the architect Clapham Lander, the Homesgarth cooperative (today Solershot House ) was built in 1909/1910 , a complex of two to three-storey houses with 24 apartments without individual kitchens, in the middle of which a communal area with a central kitchen, dining room and lounges was laid out. It was supposed to be a closed block around a courtyard, but only half of the project was implemented.

“The apartments only have facilities for preparing very small meals and cleaning the small dishes; the large dishes are washed up again in the main kitchen, which is well equipped with labor-saving equipment. A day nursery is attached to the side of the wing in a large, sunny room. A maternal nurse is in charge there and there is access to a conveniently located outdoor children's playground. Furthermore, there is also a conveniently arranged wash house with all the necessary facilities. "

The house was organized on a cooperative basis. The purchase of food and fuel was done collectively, the costs for the central facilities as well as for the kitchen and service staff were passed on to the residents. Although one wanted to distance oneself from the early socialists and sought a balance between collective and family concerns, Homesgarth was often compared to Fourier's communitarian experiments.

Zurich 1916

One project that was planned as a kitchen-house, but ultimately not carried out, is the so-called American House in Zurich on Idastrasse. The social reformer Oskar Schwank founded the living and dining house cooperative in 1915 and had the community house built in Guise based on Godin's Familistère in 1916. In addition to the central kitchen and the dining room on the ground floor, arcades were laid out in the interior, around a courtyard, across the floors . In the course of the building permit procedure, however, Schwank had to change plans, set up individual kitchens in the apartments and convert the central kitchen into a restaurant. Nevertheless, due to its construction, it was considered a collective model until the 1940s, as the wide arcades, the courtyard and the restaurant, called Ämtlerhalle , were used for the communicative activities of the residents. Community life in this house was examined and published in 1976 by the social scientist Peter Trösch through residents' surveys. This is considered noteworthy as it is one of the few testimonies of everyday life in collective institutions of the 1920s. The aspect of the effect of the architecture is only touched upon as a topic: "If the house created a sense of community and productive communication among the residents, [...] it was certainly due to the type of construction, which, unlike the Copenhagen house, is the type of the arcade courtyard house followed. ”After completion, the building itself remained in the cooperative ownership of the craftsmen involved in the construction. In 1946 it became the property of the Zürcher Löwenbräu as Ämtlerhalle AG , and it has been a protected monument since 1992.

Hamburg 1921

The Dulsberg was former arable land in the northeast of Hamburg, which was intended for development to expand the city from around 1910. From 1919 this was implemented with a reformed development plan under the direction of the city planning director Fritz Schumacher. The first residential block to be realized comprised the so-called Dulsberg settlement , the client was the city, represented by the building deputation . Schumacher initially designed these ten apartment blocks as kitchenettes, each block being provided with “a small economy” for the common supply. This should be run either as a cooperative or as an independent company. However, the Senate and Citizenship Commission for Housing Issues rejected the proposal:

"Concerns were [...] expressed from almost all sides against the introduction of the single-kitchen house. This innovation is only suitable for destroying the domestic stove and thus undermining the sense of family, it will undoubtedly fail because of the resistance of the Hamburg housewives, who would prefer to run independently. "

Schumacher was only able to achieve a rudimentary implementation of the plans for one of the ten blocks of the settlement. In the eastern section between Alsace 8-10 and Memeler road in 1921 with a three-storey brick building a single home designed with central kitchen and utility rooms. The basic idea of the Einküchehaus, the dissolution of the conventional household in favor of a collective economy, was not achieved. The house was used as a student residence for a few years , after which it was converted into a normal residential building with individual kitchens.

Vienna 1923

The Heimhof on Pilgerimgasse in Vienna is one of the most famous one-kitchen houses. It was built between 1921 and 1923 as a project for municipal housing in the Red Vienna , based on plans by the architect Otto Polak-Hellwig . The developer was the non-profit building and housing cooperative Heimhof , which went back to an initiative of the social reformer Auguste Fickerts and had operated a house for single, employed women since 1911. The core of the complex was a three-storey wing in the Pilgerimgasse, with 24 small apartments for married couples and families, in which both partners worked. The central kitchen and a common dining room formed the heart of the facility. From here, led dumbwaiters to the apartments, which instead of individual kitchens with so-called economic niches were equipped, in which the preparation of smaller meals was possible. The employees of the central housekeeping were community servants who also cleaned the apartments and took care of the laundry. A laundry was set up in the basement for this purpose. Other collective facilities were reading rooms, hot water baths, roof gardens and sun terraces. The care and care of the children during their parents' working hours was described as "excellent".

In 1924 the cooperative ran into financial difficulties, the municipality of Vienna took over the property and the management remained with the cooperative. According to plans by the architect Carl Witzmann, the Heimhof was expanded in 1925 from a free-standing building to a closed block with a total of 352 apartments. The kindergarten was integrated inside the block. During the time it was in existence, the Heimhof received very different reviews, for example at a Vienna council meeting in 1923:

“It is nonsense for a family to live in such a kitchen-house. For moral reasons it is not advisable to relieve the housewife of all household chores. The young housewife should only worry, she should learn to do business and save, that will only be of use to her in the future. "

In contrast, an architecture newspaper from 1924, after a very detailed, positive description, welcomed the project as future-oriented:

“Even the kitchen house certainly does not mean the greatest domestic happiness. But it is certainly a promising station on the way to the liberation of mankind who work with head and hand from the superfluous ballast of household chores. "

But even in Vienna, the one-kitchen house remained an isolated experiment. As early as 1934, at the beginning of Austrian fascism , the central kitchen management was discontinued. After the National Socialists came to power in 1938, the cooperative and its community institutions were finally dissolved. The apartments were now equipped with small kitchens and bathrooms, without the infrastructure they lost their attractiveness, were used as emergency shelters and were neglected. A comprehensive renovation of the home courtyard took place in the 1990s. What remains of the house is a silent film by Austrian director Leopold Niernberger from 1922 with the title Das Einküchehaus . He tells the story of a working mother who gets to know and appreciate the advantages of the Heimhof.

Amsterdam 1928

Het Nieuwe Huis in Amsterdam , which was built in 1927/28 according to a design by the architect Barend van den Nieuwen Amstel (1883–1957) in the style of the expressionist Amsterdam School , received little attention in the German-speaking discourse on public housing or modern architecture . Its origins can be traced back to the Amsterdamsche Coöperatieve Keuken (ACK) organization , which had been building a kitchen house for single people and small families at the Samenleving housing association since 1912 . In the course of a city expansion implemented from 1917 onwards, the Samenleving Cooperative, founded by municipal and state officials, took over the development of seven blocks on Roelof Hartplein, where the Het Nieuwe Huis , projected in cooperation with the ACK, was finally built . While the renting remained in the hands of Samenleving , the Coöperatieve Woonvereniging Het Nieuwe Huis, which still exists today, was founded to run the house .

In addition to the original 169 apartments and the restaurant, the building also had a library with a reading room, a post office, four shops on the ground floor, roof terraces, an in-house telephone system, dining elevators and a bicycle station in the basement. Services were available to the residents, including doing household chores and shopping. In the early years, 35 employees were employed in-house with their own management. In contrast to the previously existing, gender-separated, workers' or women's homes ( tehuizen in Dutch ), Het Nieuwe Huis was a novelty in Amsterdam due to its mixed character, which also gives the house the derisive name De Laatste Kans (German The Last Chance ) brought in.

The costs for the central facilities and the service staff were distributed among the residents, so the rent was ultimately higher than originally planned. The distribution of meals also turned out to be problematic. In 1937, with the participation of the architect van den Nieuwen Amstel, some renovations took place, including replacing the kitchen in the attic with 19 additional apartments and moving it to the ground floor. Since then, the complex, which has largely been preserved in its original state, has 188 apartments. In 2004, the building was used as Rijksmonument under monument protection provided.

Discourse History - New Building and Functionalism

With the successful spread of housing developments, the conception of large-scale housing programs such as the New Frankfurt and the construction of residential areas such as the Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin-Britz , the Jarrestadt in Hamburg-Winterhude or the Karl-Marx-Hof in the Vienna district of Döbling , history appeared of the kitchen house as an alternative to the small apartment. However, from the end of the 1920s the model found acceptance in the functionalist directions of New Building . New types of living for the sociologically described type of modern city dweller found their counterpart in residential buildings with apartments and split-level flats , the rooms of which are arranged on different levels and offset by half floors. In the forms that followed the kitchen house, these became service facilities, while the communal areas replaced central restaurants as meeting areas.

The ideological background differed widely, both from its predecessors and from one another. The Narkomfin in Moscow was designed as a communal house for a socialist way of life, the single home of the Werkbundsiedlung Breslau an architectural exhibit, the Boardinghouse des Westens in Hamburg a profit-oriented apartment building, the collective house in Stockholm a sociological project and the London Isokon Building an experiment for collective living .

Walter Gropius resumed the conceptual debate in the succession about central kitchens and communal facilities during the Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in Frankfurt in 1929 and subsequently in Brussels in 1930. At both congresses, he contrasted his concept of the high-rise apartment building with the residential and small-house buildings and justified this with the fact that sensible urban development is unthinkable if all residents live in their own home with a garden:

"The big city must be positive, it needs the incentive of the self-developed, special form of living that corresponds to its living organism, which combines a relative maximum of air, sun and vegetation with a minimum of traffic routes and management costs."

In addition to the urban planning and architectural elaborations, Gropius also presented basic socio-political assumptions. Relieving the burden of housework is a prerequisite for personal independence; accordingly, the large household is a desirable goal, especially for women after the large family has dissolved. The state takes over the former functions that have been driven out of the family by organizing children's homes, schools, old people's homes and hospitals centrally. The remaining small family functions could be accommodated in the high-rise apartment building with the help of extensive mechanization of the apartment management and centralization to the large household.

In 1931 Walter Gropius presented his design for the high-rise residential buildings on Wannsee , a plan of fifteen eleven-story steel-framed houses with a total of 660 apartments, which offer a large number of families on a relatively small strip of land an “apartment in the countryside” with a view of the Havel and Wannsee should. The apartments themselves would be furnished with small functional kitchens, while Gropius named the communal facilities as a café and social room with a roof terrace, library and reading room, sports and bathing room. A realization of the project failed both because of the global economic crisis and because of the German building laws of the time. In contrast, the high-rise residential construction carried out in Germany in the 1960s is referred to as the empty shell of the Gropius concept.

Implementations through the new building

Moscow 1928

The Narkomfin is a six-story apartment block in Moscow, built between 1928 and 1932 as a communal building for the officials of the Ministry of Finance. The architects Moissei Ginsburg and Ingnatij Milinis designed the building as part of the state-sponsored experimental construction program . It was aimed at a new way of living for Soviet citizens, which was supposed to promote equality and collectivity and only provided a small retreat for personal needs. Accordingly, apartment types with “minimum individual and maximum communal space” were created in the house, on the one hand apartments of up to 100 m² on one level, on the other hand 37 m² split-level units that are accessible over two floors. Instead of their own kitchens, shared kitchens and a central kitchen were available. This was next to other communal facilities such as a sports hall, wash house and library in an additional block, accessed through an in-house “glass street”. There was a garden and sun terraces on the roof of the complex, as well as a penthouse that was occupied by the then Soviet Finance Minister Nikolai Milyutin.

The building is considered to be trend-setting for Soviet constructivism. However, a planned associated second apartment block and a kindergarten were no longer implemented. In 1932 Stalin ordered architects to merge into one umbrella organization. The Russian avant-garde , which until then was regarded as the artistic expression of the revolution , was not allowed and was banned from building: visionary building experiments were viewed as a waste and would not bring any profit for the Kommunalka . The community facilities of the Narkomfin were subject to a conversion, the building has been falling apart since then. In 2006, the World Monuments Fund put it on the list of buildings at risk, and international conservationists are committed to preserving it.

Wroclaw 1929

The single home , house 31 of the Werkbundsiedlung Breslau, was one of 37 project houses that were built in 1929 as part of the Werkbund exhibition Apartment and Workroom . Created by the architect Hans Scharoun , it comprised 66 split-level apartments equipped with minimal kitchens, communal areas and a central restaurant. It was geared towards the “nomadic city dwellers”, single people or married couples without children, and offered hotel-like service for the temporary abode of “cosmopolitanism”. The armored cruiser Scharoun , as the house was also mockingly called, was considered the first building with apartments over two levels, which also influenced Moisei Ginzburg's remarks at the Narkomfin in Moscow. The house was later converted into the Park Hotel Scharoun .

Altona 1930

The boarding house of the West on the shoulder blade in today's Hamburg-Sternschanze was built in 1930 in the then independent city of Altona on a plot of land on the border with Hamburg. It is a six-storey building with a strictly structured façade and a tower-like oriel arch projecting over the sidewalk and was built by the architects Rudolf Klophaus , August Schoch and Erich zu Putlitz as a kitchen house. The owner C. Hinrichsen did not strive for the tenants to live together, but for individual living with the service of a hotel. The apartments were of various sizes and without kitchens; they could be rented for a longer or shorter period with or without service or cleaning. There were restaurants and shops on the first floor. The form of living was considered sophisticated and expensive, and it failed within a few years. Small apartments were set up as early as 1933, and in 1941 it was converted to an administration building.

Stockholm 1935

The Kollektivhuset in Stockholm was built as a six-storey functionalist building between 1932 and 1935 by the architect Sven Markelius . The fifty apartments were small and without kitchens, the focus was on the communal facilities of the central kitchen, dining room, kindergarten and roof terrace. Everyday work was made easier by dining elevators, dump channels for dirty laundry and a cleaning service. The collective life of working couples and families belonging to the Swedish intellectual elite received increased public attention as a pilot housing project of the Swedish welfare state . The child care was subject to the anti-authoritarian educational concept of the sociologist Alva Myrdal and was accompanied by educational investigations and studies. After ten years, the project was considered to have failed because the community had fallen out.

London 1933

The Isokon Building by architect Wells Coates in London is also considered an experiment in collective living. It was initiated by the married couple Molly and Jack Pritchard, who were both builders and residents of the house. It comprised 34 apartments, equipped with small kitchenettes. The supply was mainly carried out via a central kitchen, which was connected to the individual units by a transport device called a "silent servant". There was also an organized cleaning, laundry and shoe cleaning service. The residents were considered to be left-wing intellectuals, including Marcel Breuer , Agatha Christie , Walter Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy and James Stirling at times . Also at times Adrian Stokes , Henry Moore and the communist agents Arnold Deutsch and Melita Norwood . In 1972 the house was sold and fell into disrepair, in 2003 it was saved as an architectural monument and restored as an apartment complex . Since then it has been inhabited by key workers from the public sector.

Further development in the Unités d'Habitation

From 1922, the French architect Le Corbusier worked on concepts and plans for large residential units, which he called Immeubles-Villas as the city of buildings. He explicitly saw in it counterparts to "slavish individualism" and the "destruction of public spirit" by the English and German garden city movements and described them as "a hundred villas, stacked in five layers". The individual units should be two-story with gardens but no kitchens. The usual services would be organized like a hotel, technical facilities such as hot water pipes, central heating, cooling, vacuum cleaners and drinking water purification would replace human labor. The servants come in like a factory to do their eight-hour work.

From 1930 onwards, Le Corbusier designed the Ville Radieuse , the vertical city, with reference to the Russian Narkomfin building. The large buildings contained the concept of a functional city system, divided into usage zones with living, production, transport and supply areas, with hanging gardens and centralized services and housekeeping.

Le Corbusier's concepts were partially implemented in the Unités d'Habitation , which were implemented between 1947 and 1964 in the four French cities of Marseille , Nantes , Briey and Firminy as well as in Berlin. These are 17- to 18-story high-rise buildings in reinforced concrete - frame construction with more than three hundred homes. Comprehensive infrastructural and cultural facilities such as kindergartens, roof terraces with swimming pools, training tracks and observation towers, sports halls, classrooms, studio stages, open-air theaters, restaurants and bars were planned for all five projects. Halfway up the building, on the seventh and eighth floors, internal streets called “rue intérieure” were planned with rows of shops and service facilities. Only the Cité radieuse in Marseille in 1947 was realized to this extent . The other four buildings had to make cuts due to financing problems. In the Corbusierhaus in Berlin, for example, the communal roof facilities have given way to the technical structures of the elevators and ventilation systems, and the roof area is not available to residents.

In contrast to the planning, the units of the Unité d'Habitation were equipped with kitchens. During the realization, Le Corbusier abandoned the concept originally intended as an intervention in social development. Instead of new social content in the form of living, the large residential complexes became abstract organizational schemes of a functional city.

State of research

In the German-speaking world, the history of the one-kitchen houses is largely forgotten after the extensive debates from the beginning to the middle of the 20th century. There was a brief rediscovery in the early 1970s, when the student movement brought the idea of collective living into university discussions. During this time, a number of publications were made that made the historical material known again and were used as arguments for their own shared apartment experiments. In 1981 the architect and sociologist Günther Uhlig received his doctorate on the subject of the collective model of a single kitchen house. Housing reform and the architectural debate between the women's movement and functionalism and, with his doctoral thesis, presented a discourse analysis of the contemporary publications accompanying the development. At the same time he created a standard work on which the other publications refer. The professor of urban planning Ulla Terlinden and the sociologist Susanna von Oertzen did a further work in 2006 with the book The housing question is a woman's matter! Women's movement and housing reform from 1870 to 1933 . They expanded Uhlig's research to include the evaluation of sources from writings of the women's movement and placed the kitchenettes in the overall context of the participation of women in the development of housing history.

Most of the English-language publications on the subject come from Scandinavia. In particular, the architect Dick Urban Vestbro, professor at Stockholm University, has worked in many publications on the pan-European history of single-kitchen houses as well as their influence on alternative forms of living with a central kitchen that exist today, especially in Sweden. No corresponding research on developments in Germany, Austria or Switzerland is known. The subject of the co-housing movement in the United States and its close connection with European models has been extensively researched by the American urban historian Dolores Hayden. She has published her results in numerous publications.

On the occasion of a meeting of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in November 2009, the architect Anke Zalivako made a brief statement entitled From the Commune House to the Unité d'Habitation - a European Heritage? proposed a “network of residential buildings with central service facilities” for nomination as a European Heritage Label, thus demonstrating the Europe-wide cultural connection between some modern-day kitchenettes. The proposed network comprises buildings in six countries and consists of the Heimhof in Vienna, the single home in Breslau, the Narkomfin in Moscow, the Isokon Building in London, the Unité d'Habitation in Marseille and the Corbusierhaus in Berlin.

List of kitchenettes

The following table gives a summarizing overview of the twenty houses described above, which were designed as one-kitchen houses in European cities between 1903 and 1965. The Existing column shows the year up to which the central kitchen was fitted out, the planning stage indicates that the original designs were not implemented.

| House | Construction year | Duration | Architects | organization | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Service House Copenhagen |

1903 | 1942 | Otto Fick | Private company with participation | |

|

Hemgården Centralkök Stockholm Östermalmgatan 68 |

1906 | 1918 |

Georg Hagström , Fritiof Ekman |

Private company | |

|

Einküchehaus Charlottenburg Berlin Kuno-Fischer-Strasse 13 |

1908 | 1913 | Kurt Jähler | Private company / GmbH | |

|

Einküchehäuser Lichterfelde Berlin Unter den Eichen 53 |

1909 | 1915 | Hermann Muthesius | Private company / GmbH | |

|

Kitchenette houses Friedenau Berlin Wilhelmshöher Strasse 17-20 |

1909 | 1917/18 | Albert Gessner | Private company / GmbH | |

|

Homesgarth (Solershot House) Letchworth Garden City |

1909/10 | not known | Clapham Lander | cooperative | |

|

American House Zurich |

1916/17 | up to construction planning | Oskar Schwank | Cooperative of the craftsmen involved in the construction | |

|

Single home Dulsberg Hamburg Elsässer Strasse 8-10 / Memeler Strasse |

1921 | not known | Fritz Schumacher | Public housing | |

|

Heimhof Vienna Pilgerimgasse 22–24 |

1922/1926 | 1934 | Otto Polak-Hellwig | cooperative | |

|

Het Nieuwe Huis Amsterdam Roelof Hartplein 50 |

1927/28 | not known | Barend van den Nieuwen Amstel | cooperative | |

|

Narkomfin Moscow Novinsky Boulevard |

1928 | 1932 |

Moissei Ginsburg , Ingnatij Milinis |

Public housing | |

|

Single home Werkbundsiedlung Breslau Werkbundsiedlung, house 31 |

1929 | not known | Hans Scharoun | Private company, funded | |

|

Boardinghouse des Westens Hamburg shoulder blade 36 |

1930/31 | 1933 |

Rudolf Klophaus , August Schoch , Erich zu Putlitz |

Private company | |

|

Kollektivhuset Stockholm John Ericsonsgatan 6 |

1932/1935 | 1945 | Sven Markelius | Public housing | |

|

Isokon Building London |

1933/34 | 1970 | Wells Coates | Private company | |

|

Unité d'Habitation Marseille |

1947 | Planning stage | Le Corbusier | Public housing | |

|

Cité radieuse de Rezè Nantes |

1955 | Planning stage | Le Corbusier | Public housing | |

|

Corbusierhaus Berlin |

1958 | Planning stage | Le Corbusier | Public housing | |

|

Unité d'Habitation Briey en Forêt |

1963 | Planning stage | Le Corbusier | Public housing | |

|

Unité d'Habitation Firminy |

1965 | Planning stage | Le Corbusier | Public housing |

literature

- Architects and Engineers Association of Berlin (ed.): Berlin and its buildings. Part IV: Housing. Volume B: The residential buildings - apartment buildings. Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-433-0066-4 .

- Lily Braun : Women's work and housekeeping. Expedition of the Vorwärts bookstore, Berlin 1901.

- Florentina Freise: ascetic comfort. The Isokon service house in London. Athena-Verlag, Oberhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-89896-321-3 .

- Hartmut Häußermann, Walter Siebel: Sociology of living. Juventa Verlag, Weinheim / Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7799-0395-4 .

- Dolores Hayden: Redesigning the American Dream: Gender, Housing, and Family Life. WW Norton & Company, New York 1984. (New edition 2002, ISBN 0-393-73094-8 )

- Hermann Hipp : City of Hamburg. Apartment buildings between inflation and the global economic crisis. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-89479-483-5 .

- Staffan Lamm, Thomas Steinfeld : The collective house. Utopia and reality of a living experiment. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-10-043924-4 .

- Claire Richter: The economics. Large-scale domestic business as an end in itself. Berlin 1919.

- Ulla Terlinden, Susanna von Oertzen: The housing issue is a woman's business! Women's movement and housing reform 1870 to 1933. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-496-01350-8 .

- Günther Uhlig : collective model “Einküchehaus”. Housing reform and architectural debate between the women's movement and functionalism 1900–1933. (= Werkbund Archive. 6). Anabas Verlag, Giessen 1981, ISBN 3-87038-075-6 .

Web links

- Jens Sethmann: 100 years of kitchenettes . Failed reform experiment. In: tenant magazine of the Berlin tenants' association, January / February 2008

- Hiltraud Schmidt-Waldherr: Emancipation through kitchen reform? Kitchen house versus kitchen laboratory. In: L'Homme. Journal of Feminist History. Issue 1/1999, pp. 57-76; online at Democracy Center Vienna (PDF; 181 kB)

- Dick Urban Vestbro: History of cohousing - internationally and in Sweden. ( Memento from February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) November 2008 (PDF; 1.3 MB)

- Anke Zalivako: From the community center to the Unité d'Habitation - a European legacy? Brief statement on the occasion of the ICOMOS workshop "European Heritage Label and World Cultural Heritage" on 20./21. November 2009 in Berlin; in: kunsttexte.de January 2010 (PDF; 192 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Anke Zalivako: From the community center to the Unité d'Habitation - a European heritage? Brief statement on the occasion of the ICOMOS workshop "European Heritage Label and World Cultural Heritage" on 20./21. November 2009 in Berlin, p. 1.

- ^ A b Günther Uhlig: collective model of a kitchen house. Business cooperatives (also) as a cultural alternative to mass housing construction. In: ARCH + , magazine for architects, urban planners, social workers and local political groups, No. 45, Aachen July 1979, pp. 26–34, here p. 26.

- ↑ Hartmut Häußermann , Walter Siebel : Sociology of living. Weinheim / Munich 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Leipziger Illustrierte Zeitung , 1873; quoted from: Hartmut Häußermann, Walter Siebel: Sociology of Living. Weinheim / Munich 1996, p. 88.

- ↑ Günther Uhlig: Collective model kitchen house. Housing reform and architectural debate between the women's movement and functionalism 1900–1933. Giessen 1981, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Hartmut Häußermann, Walter Siebel: Sociology of living. Weinheim / Munich 1996, p. 132.

- ^ A b c Dick Urban Vestbro: History of cohousing - internationally and in Sweden. ( Memento of February 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ), November 2008 (PDF; 1.3 MB), accessed on March 24, 2011.

- ↑ Julius Posener ; quoted from: Hartmut Häußermann, Walter Siebel: Sociology of Living. Weinheim / Munich 1996, p. 96.

- ^ Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels: Manifesto of the Communist Party. In: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels - works. Volume 4, 6th edition. Berlin / DDR 1972, p. 490 available online under Marx-Engels-Werke , accessed on March 24, 2011.

- ↑ Ulla Terlinden, Susanna von Oertzen: The housing issue is a woman's business! Women's movement and housing reform 1870 to 1933. 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Melusina Fay Peirce: Co-operative Housekeeping: How not to do it and How to do it. JR Osgood and Co., Boston 1884; available at openlibrary.org , accessed March 31, 2011.

- ^ Dolores Hayden: Redesigning the American Dream. ( Memento from September 19, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Hedwig Dohm: Jesuitism in the household. Berlin 1873; quoted from: Ulla Terlinden, Susanna von Oertzen: The housing issue is a woman's business! Women's movement and housing reform 1870 to 1933. 2006, p. 137.

- ↑ August Bebel: The woman and socialism. 62nd edition. Berlin / GDR 1973, p. 510; available online at Marx-Engels-Werke , accessed on March 25, 2011.

- ↑ Günther Uhlig: Collective model kitchen house. Housing reform and architectural debate between the women's movement and functionalism 1900–1933. Giessen 1981, p. 51.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin: La Conquete du Pain. Available in the French original: wikisource: La Conquête du pain, Le travail agréable and in English translation wikisource: The Conquest of Bread, Chapter X , accessed on March 31, 2011.

- ↑ Ulla Terlinden, Susanna von Oertzen: The housing issue is a woman's business! Women's movement and housing reform 1870 to 1933. 2006, p. 160.