Ernst Fraenkel (political scientist)

Ernst Fraenkel (born December 26, 1898 in Cologne , † March 28, 1975 in Berlin ) was a German-American lawyer and political scientist . He is considered one of the "fathers" of modern political science in the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin .

Fraenkel wrote about four political systems in particular: about the Weimar Republic , the Nazi state , the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany. His collected writings have been published as a complete edition in seven volumes since 1999. "Ernst Fraenkel's life's work is shaped by his development from socialism to pluralism ."

In the Weimar Republic, Fraenkel worked as a lawyer for the socialist labor movement and published a large number of articles, mainly on labor law issues. Persecuted as a Jew by the National Socialists and engaged in the resistance , he emigrated to the United States, where he completed The Dual State , his interpretation of the Nazi state. The book was published in 1974 under the title Der Doppelstaat in German and is now considered a classic. Fraenkel developed the central idea of neopluralism and was one of the founders of West German democratic theory . He used his studies on the United States to compare Germany with Western democracies and to analytically and normatively underpin his own theoretical democratic ideas .

From 1963 Fraenkel was the first director of the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at the Free University of Berlin .

Life

Empire and Republic

Family, school days and World War I

Fraenkel first grew up in Cologne with his parents in a wealthy Jewish merchant family. After attending the Kreuzgasse pre-school, he switched to the Kreuzgasse grammar school in 1908 . His older brother Maximilian (* 1891) and his father Georg (* 1856) died in 1909. His mother Therese Fraenkel, née Epstein (* 1864), died in 1915. After his mother's death, Ernst moved in with his sister Marta (1896–1976) ) to Joseph Epstein, a maternal uncle, to Frankfurt , where he attended the model school , where he that in November 1916 Notabitur took off.

In November 1916, the 18-year-old volunteered as a war volunteer . In his unit he got to know the later reform pedagogue Adolf Reichwein and rescued him after a life-threatening injury on December 5, 1917 during heavy fighting on the Western Front . On April 1, 1918, Fraenkel's front-line deployment ended because he was injured by a hand grenade. During the November Revolution of 1918 he became a member of the Darmstadt Soldiers' Council , but did not see himself as a revolutionary .

Education

After his discharge from the army in January 1919, Fraenkel initially planned to study history , but after the influence of his uncle Joseph decided to study law with history as a minor. He mainly studied at the young Frankfurt University , with intermediate semesters in Heidelberg and Tübingen . During his studies in Frankfurt he met Franz L. Neumann and Leo Löwenthal ; together they founded a group of socialist students in 1919. In 1921 Fraenkel joined the SPD . His political and professional role model was the lawyer Hugo Sinzheimer . Fraenkel studied with Neumann, Hans Morgenthau , Otto Kahn-Freund and Carlo Schmid . The study of modern labor law provided Fraenkel with important insights into the relationship between law, society and the state, which among other things became fundamental for his later analysis of National Socialism . In December 1921 Fraenkel passed his first state examination, in December 1923 he did his doctorate with Sinzheimer on the subject of the void employment contract for Dr. jur. Fraenkel spent his legal clerkship (January 1922 to July 1924) in Weilburg and Frankfurt am Main; in January 1925 he passed the second state examination .

Worked as a lawyer, for the trade union and as a defender of the republic

As a fully qualified lawyer , Fraenkel initially worked in a law firm in Saarbrücken . From 1926 to 1938 he was admitted to the bar at the Kammergericht Berlin. In spring 1926 he joined the German Metalworkers' Association (DMV). In Bad Dürrenberg, he taught members of works councils at the newly founded business school of the DMV, particularly on issues of labor law and social policy . At the same time he published essays on labor law, legal sociological and constitutional issues.

At the beginning of 1927 Fraenkel ended his teaching activities and opened a law firm in Berlin . His good contacts to the DMV, his publications on questions of labor law and his lectureship at the German University of Politics in Berlin and the Academy of Labor in Frankfurt am Main helped him to establish the office. After the completion of the new DMV headquarters in Berlin, Fraenkel moved his office to this building. Together with Franz L. Neumann he ran a law firm there and acted as the union's syndic . He also represented the SPD executive committee in the final phase of the republic.

At the same time, as a publicist, the lawyer stood up for the preservation of the republic when it fell into a serious crisis in the early 1930s. He worried about the preservation of the constitution and wanted to stabilize this legal basis of the republic from parliament. The negative majority achieved by the Communists and National Socialists in the Prussian state elections in April 1932 and the Reichstag elections of July 1932 , two central parliaments, the Reichstag and the Prussian state parliament, were unable to act. Conservative journalists and politicians were looking for an authoritarian solution: Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , based on Articles 48 and 25 of the Weimar Constitution, was to rule by emergency decree and against parliament. Fraenkel had an opposite solution in mind:

“Our proposal is to give a vote of no confidence by parliament against the chancellor or minister the legal consequence of being forced to resign if the people's representatives combine the vote of no confidence with the positive proposal to the president to assign a named personality to the minister in place of the ousted state official appoint."

His suggestion of a constructive vote of no confidence was not taken up, but was incorporated into the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany as Article 67 . Fraenkel can thus be regarded as "one of the fathers of the constructive vote of no confidence", even though the basic principle was first described by Heinrich Herrfahrdt in 1927 and has been discussed since then.

On December 24, 1932, Ernst Fraenkel married Johanna Pickel (1904–1975), called Hanna, whom he had met in Bad Dürrenberg. The marriage remained childless.

In the Third Reich and in exile

Legal work and resistance

The Restoration of the Civil Service Act forbade Jewish attorneys to represent clients in court. Fraenkel was also affected. On May 11, 1933, however, he succeeded in obtaining his re-admission to court through the so-called front fighter privilege . There was no doubt that he had taken part in several World War II battles and was wounded. The certificate of good repute that Adolf Reichwein issued him was clearly positive. Fraenkel's partner Franz Neumann, however, was barred from practicing law in Germany. He fled to Great Britain on May 10, 1933 .

Fraenkel was active in the resistance against National Socialism . Here he made contacts with members of the International Socialist Combat League (ISK). He published anonymously in the organ of the ISK, the Sozialistische Warte , among other things an essay on the "meaning of illegal work". In addition, he was in close contact with Alwin Brandes , Richard Teichgräber , Heinrich Schliestedt and other leading functionaries of the German Metalworkers' Association (DMV), which was banned on May 2, 1933 and who had meanwhile organized underground work and had built up a comparatively large union resistance group. He kept in close contact with the Red Shock Troop group . Among other things, he traveled to Amsterdam and London as a courier for the resistance group in 1933/34. After he was forbidden to defend their leader Rudolf Küstermeier and Willi Schwarz , also from the leadership group of the Red Strike Troop, at the People's Court in early 1934 , Fraenkel put his colleague Heinrich Reinefeld in touch. Fraenkel visited Küstermeier several times in the penitentiary and kept in touch with his wife Elisabeth and with other actors in the Red Strike Troop.

Fraenkel's tolerated professional activities included advising and legal representation of those persecuted by the Nazi regime. As a result, he was targeted by the Gestapo . On September 20, 1938, following a corresponding hint, he evaded imminent arrest and fled to London . His wife Hanna followed him into exile on November 13 of the same year. The couple were largely destitute. The money they had made by selling their house ended up in a "blocked emigrant account" as a result of discriminatory tax measures by the Nazi state (see restrictions on taking away from the foreign exchange office ). A little later it was fully offset against the “ Reich flight tax ”. Together, the couple could only export 60 Reichsmarks in cash .

Exile in the United States

After a short stay with Otto Kahn-Freund in London, Hanna and Ernst Fraenkel embarked in Southampton in November 1938 to emigrate to the United States. Fraenkel's attempts to get employment at the New School for Social Research in New York failed. After receiving one of the coveted scholarships of the American Committee for the Guidance of Professional Personnel , Fraenkel began studying American law at the University of Chicago Law School in the fall of 1939 at the beginning of World War II . On June 10, 1941, he passed the exam and received the title Doctor of Law . During this time, the couple lived in Chicago 's Hyde Park neighborhood, near the campus.

Since his arrival in the United States, Fraenkel also worked on the comprehensive revision of his extensive manuscript on the Nazi state. It was published at the turn of 1940/41 under the title The Dual State (→ Der Doppelstaat ). In his study, the author distinguished the normative state , whose actions are based on laws , from the state of action , which are based on considerations of political expediency and act against population groups defined as enemies of the regime.

The now stateless person - the Nazi authorities expatriated Fraenkel in June 1940 - took up a position in a Washington law firm on October 1, 1941 . Fraenkel was supposed to help enforce American property claims in Europe that was shaped by World War II . The employment relationship ended in January 1942, because the entry of the United States into the war made this job seem hopeless.

The Fraenkel couple moved from Washington to Forest Hills , a neighborhood in the Queens borough of New York City . Ernst Fraenkel tried again to work at the New School for Social Research, if possible as a social or political scientist. Again he was unsuccessful. However, he did manage to teach courses from 1942 to 1944 at the Free French University ( École Libre des Hautes Études ), which was located under the umbrella of the New School, in which European lawyers were introduced to American law. David Riesman and Hans Staudinger , who works at the New School, helped arrange this teaching activity. However, Fraenkel initially earned the majority of his livelihood by working for two refugee organizations: the American Federation of Jews from Central Europe led by Rudolf Callmann and a self-help organization for emigrants led by Paul Tillich . However, the work for these refugee organizations ended after a few months.

From 1942 to 1943 Fraenkel took on a research contract funded by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace . He investigated the conclusions to be drawn from the occupation of the Rhineland after the First World War for a future legally regulated policy of occupation in Europe. In 1944 he published his treatise Military Occupation and the Rule of Law . This work enabled him to get a job with US authorities, for which he worked between 1944 and 1951. Initially, Fraenkel was a member of the Foreign Economic Administration (FEA) in Washington, DC from 1944 to 1945 . His superior was Hedwig Wachenheim . Specifically, he dealt with questions of the judiciary in the context of planning for the post-war occupation of the Axis powers and for future Germany policy. Fraenkel's office worked closely with the research department of the Office of Strategic Services . At the time of this employment, he acquired American citizenship (August 15, 1944).

When the FEA was dissolved in the autumn of 1945, Fraenkel decided not to return to Germany, although his long-time friend Otto Suhr asked him to do so and many exiles went back as employees of US occupation authorities. Because of the reprisals he suffered and the information about the Holocaust , Fraenkel considered it impossible for him to return as a Jew.

Advisor in Korea

At the end of 1945 Fraenkel took up a position as a consultant to American authorities in Korea . He was supposed to help rebuild the legal system there after Japanese rule ended in 1945 and the country was under the patronage of the United States and the Soviet Union . As a connoisseur of German law, Fraenkel seemed to be suitable, because Japan had received German legal culture intensively, so that Korea was influenced by it. In addition, he had already proven himself to be an expert in occupation law. On site, he worked at a branch of the United States Department of Justice . In March 1946 he was admitted to the Korean Supreme Court. He was part of a delegation that dealt with questions relating to the reunification of the country - a project that was becoming increasingly unrealistic. When the United Nations - despite opposition from the Soviet Union - received the order to organize elections for the whole of Korea, Fraenkel supported American liaison officers in working with US authorities and UN agencies. Fraenkel was instrumental in drafting the electoral law for the whole of Korea , and later also in the drafting of the South Korean electoral law. He also advised the Korean National Assembly on constitutional issues . After the Republic of Korea was founded on August 15, 1948, Fraenkel joined the American Embassy in Seoul and acted as legal advisor to the Marshall Plan Commission for Korea ( Economic Cooperation Administration Mission to Korea ). He also gave several lectures on constitutional and international law at Seoul State University . After the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, Fraenkel was evacuated to Japan . There he was still in the service of American authorities and dealt with Korean issues until April 1951. Fraenkel received the Meritorious Civilian Service Award , a prestigious honor for civilians serving in the American military, for its commitment to the elections in Korea .

Back in Germany

Political scientist in Berlin

After Otto Suhr, head of the reopened School of Politics, tried again to recruit Ernst Fraenkel, he finally managed to return to Germany. At the end of April 1951 he landed in Berlin with his wife. His return was funded by American agencies: On behalf of the High Commission for Occupied Germany (HICOG), he was initially supposed to stay six months and, as part of the Information and Education program , primarily give lectures and thus contribute to political education. He immediately began a lively lectureship at the Politics College. He also gave lectures at the Institute for Political Science (IfpW) of the Free University of Berlin (FU Berlin) and at the law faculty there. From 1952 he also offered events at the historical Friedrich Meinecke Institute of the Free University of Berlin. His assignment was extended twice by the HICOG until 1955/56. The Americans also paid for his position for three semesters.

During this time, Fraenkel appeared as a speaker at many trade union lecture events, although Ernst Scharnowski and Gustav Pietsch rejected the offer he made to the district of the German Trade Union Federation immediately after arriving in Berlin to become involved in the ranks of the trade unions . His relationship with the trade unions and the SPD, which he did not rejoin, remained much more distant than in the years of the Weimar Republic.

In February 1953, the Free University of Berlin appointed him to the newly established chair in the science of politics, theory and the comparative history of political systems of rule . There he shaped the development of political science in the 1950s and 1960s and became one of its “leading figures”. At his chair, the US citizen Fraenkel was primarily concerned with conveying a positive image of the United States, because he registered the continued effect of many anti-American prejudices. The American constitution always had a special place in his political science seminars . Fraenkel's image of America was not only shaped by his exile, but also by other stays in the USA. In 1954/55 he was a visiting professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill . 1958/59 he taught at the University of California, Berkeley . Before taking on a full professorship , civil service hurdles had to be overcome, because Fraenkel would have had to swear an oath on the Basic Law, which would automatically have resulted in the loss of American citizenship. After it had been agreed that instead he only had to vow to conscientiously fulfill his official duties, Fraenkel received the professorship in 1961. Fraenkel "was considered the undisputed doyen of the OSI ".

The author of the Dual State did not participate in efforts to come to terms with the Nazi past , although at the end of the 1950s he had planned a corresponding project on justice in the Nazi state with Helmut Krausnick , head of the Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ). However, this project failed. Instead, an apologetic treatise on this topic by Hermann Weinkauff appeared in one of the IfZ's series of publications in 1968 .

Pluralism and student movement

In the 1960s, Fraenkel developed the theory of pluralism and has since been considered the founder of so-called neopluralism . In his research he analyzed in particular the conditions in the United States and the Federal Republic.

Since 1963, Fraenkel was also the first director of the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies , which he was instrumental in initiating and which, thanks to its interdisciplinary approach, quickly achieved a leading position in the field of North American research.

From the mid-1960s onwards, Fraenkel took a critical look at the student movement , which was constituted relatively early in Berlin and which gained influence at the Otto Suhr Institute . When it was announced in April 1967 that the FU-Spiegel , the official journal of the General Student Committee (AStA) of the Free University, would publish an anonymous review of his last seminar before his retirement , Fraenkel protested vigorously in front of the academic senate, which thereupon the journal threatened disciplinary action. The review - written by Claudia Pinl according to her own statements - nevertheless appeared. "Fraenkel viewed this as a breach of trust and spying."

Fraenkel accused the student movement anti-democratic dogmatism before and felt by the behavior of rebellious students in the 1930s remembers when raiding the SA meetings blasted political opponents and National Socialist student Jewish and democratic professors had attacked. He feared that the universities would be instrumentalized for anti-democratic purposes. In an extensive interview that was announced on the front page, Fraenkel expressed his disapproval of the practices of the student movement in the Berliner Morgenpost on September 17, 1967: He described certain forms of action of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS) as "SA methods" and demanded resistance. Like some other Jewish scientists, for example Helmut Kuhn , Fraenkel considered emigrating again. The Fraenkel couple considered going back to the United States.

Fraenkel suggested that student groups calling for councils and a political mandate were actually guided by the idea of a “university soviet ”. He categorically rejected councils as institutions that would lead to totalitarian rule . Fraenkel was no longer aware of any hints from younger political scientists who used organizational sociological arguments against council rule and pointed out that councils were inadequate in an industrial society because they were under- complex . Although he expressed understanding for the dissatisfaction of students and assistants in university policy matters, he strictly rejected the pursuit of general political goals. In the event that the students would not accept the relevant court decisions, he held out the prospect of abandoning the Berlin model of student self-administration . He particularly turned against the Vietnam resolution of the student convention, with which the American warfare in Vietnam was criticized. Fraenkel saw in the resolution above all contempt and open hostility towards the United States as the protecting power of West Berlin.

In an interview with the Berliner Morgenpost on September 17, 1967, Fraenkel explicitly denied the question of whether he wanted to equate the SDS with the National Socialists. Nevertheless: His statements and the place of publication - a newspaper of the Axel Springer Verlag - were in the eyes of student activists a reactionary devaluation of their political aspirations. Fraenkel was seen by the Marxist- inspired spokesmen of the New Left as a scientist who was affirmative of the existing conditions , lacked criticism of capitalism and the USA and gave no practical advice on revolutionizing contemporary society. In addition, “Fraenkel, who cultivated a paternalistic-professorial style, gave him the opportunity to label him as a representative of the old, outdated Ordinary University - especially at the OSI, whose young assistants saw themselves as the nucleus of a reform university.” “The anti-fascist , socialist and pluralist saw each other pushed into the reactionary camp. "

The conflict between Fraenkel and the student movement also revealed different experiences with and expectations of law and power , representation and participation . Whether an identitary concept of the people (the people as a unit) can be assumed and whether direct popular rule should be advocated or feared - Fraenkel and Richard Löwenthal , a Jewish remigrant who also teaches at the OSI, and the spokesmen for the New Left differed in their answers , for example Johannes Agnoli , basically.

Last years

Fraenkel experienced the student movement's criticism of his academic work as marginalization . The sharp words with which he reacted to their forms of action and revolutionary hopes increased the distance to the rebellious students. Attempts at mediation, such as those made by his student Winfried Steffani , were unsuccessful. He could not gain much from the institutional changes in the universities as a result of the university reform. Rather, he feared the rise of the scientific mediocre. For this reason he joined the emergency community for a free university . According to his biographer Simone Ladwig-Winters, the conflicts did not remain without effects on his health: Fraenkel fell ill with shingles and a protracted neuritis in 1967 . He also suffered several heart attacks and a stroke . This was followed by severe depression . In 1971 Fraenkel took on German citizenship again because the long stays in the USA necessary to maintain his American citizenship were too expensive for him.

In 1974 the German translation of the Dual State appeared . Fraenkel had long resisted a translation into German, but finally agreed and took an intensive part in the retranslation. However, Fraenkel did not experience a detailed reception of this study in Germany.

After his retirement on April 1, 1967, he took on a guest professorship in 1969 at the University of Salzburg, which was untouched by student unrest . He has also received a number of honors: the University of Bern awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1969 , a commemorative publication was dedicated to his 75th birthday in 1973, and the Federal Republic of Germany honored him with the Great Federal Cross of Merit . In 1975 the state of Berlin awarded him the Ernst Reuter badge .

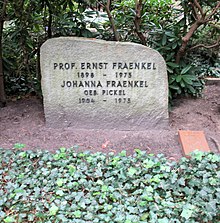

The developments since 1967 at the universities, at the FU Berlin as a whole and especially at the Otto Suhr Institute depressed him. He withdrew and avoided the institute. His death on March 28, 1975 went largely unnoticed. Fraenkel's body was buried on April 8, 1975 at the Dahlem forest cemetery. The grave is one of the honor graves of the State of Berlin .

plant

Weimar writings

Fraenkel examined in a longer text, which appeared in 1927 as a brochure in the “Young Socialist Series” of the Young Socialists under the title “On the Sociology of Class Justice ”, social conditions of judicial jurisdiction in the Weimar Republic. It is important to him to make the political and social position of the judiciary transparent in terms of the sociology of knowledge . In order to explain the basic tendencies of judicial decisions, material influences, training compulsions , socio-psychological factors, current events and ideological justifications of law should be examined. Fraenkel names inflation- related income losses, the associated experiences of social decline , conservative influences in the practical training of lawyers and an aversion to the workers resulting from these circumstances , which are supposedly better off in the republic. In this situation, Fraenkel advises to insist on a formalistic and narrow interpretation of law, instead of allowing finalistic jurisdiction that gives judges wide discretion.

Among the most important publications by Fraenkel during the time of the grand coalition under Hermann Müller are four essays on the Ruhreisenstreit . From a trade union perspective, the author worked out the political consequences of the conflict and how it was resolved through arbitration , arbitration and court decisions.

During the years of the presidential cabinet under Heinrich Brüning , Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher , Ernst Fraenkel called on the socialist workers' movement to defend the achievements of the republic. The compromise found in the Weimar Imperial Constitution provided opportunities for shaping a democracy that went beyond traditional liberal ideas of democracy: Fraenkel speaks here of “ collective ” or “ dialectical democracy”. Fraenkel emphasizes, later reflections on neopluralism already suggesting that in every society, including class society , there is a controversial and an indisputable sector . However, the undisputed sector cannot be made absolute, as representatives of authoritarian political concepts assume. Nor can controversies in the contentious sector be prohibited by law. With these considerations, Fraenkel positioned himself in particular against Carl Schmitt , the most important constitutional advocate of an authoritarian democracy with plebiscitary elements. Schmitt's basic assumption of an indivisible, homogeneous and unified people gives Fraenkel a clear rejection. It is sociologically ignorant, historically wrong, politically misleading and unworldly and utopian. Despite all the criticism, the relationship with Schmitt is nonetheless more complex: During the Weimar period, Fraenkel referred to Schmitt with a lot of respect, sometimes even admiration. But after he appeared as an advocate of National Socialist violence, Fraenkel saw in Schmitt's writings forerunners of National Socialist legal thought.

According to Fraenkel, “collective democracy” no longer worked since Hindenburg began relying on presidential governments at the end of March 1930. In this situation Fraenkel took part in reflections on constitutional reform with his essay “Constitutional Reform and Social Democracy”. In doing so, he endeavored to establish a new balance between the Reichstag , Reich government and Reich President through the smallest possible constitutional changes and made three interrelated proposals:

- Votes of no confidence against ministers or chancellors should only be permitted if a parliamentary majority for a new minister or head of government can be proven (constructive vote of no confidence).

- Article 48, paragraph 3 of the constitution should also be changed. If the Reichstag vetoed an emergency ordinance by the Reich President, the ordinance would not immediately lapse. Rather, the Reich President should be given the opportunity to bring about a plebiscite decision by the electorate. A parliament that only behaves obstructively can be bypassed in this way.

- Frequent dissolutions of parliament are made more difficult if the Reich President, by amending Article 25 of the Weimar Constitution, is only permitted to take such a measure after a plebiscite on emergency ordinances or if it is linked to the signature of a newly elected Chancellor or Minister by the Reichstag.

Fraenkel hoped that his reform proposal would regain parliamentary capacity to act. At the same time, he was aware of the low chances of realization, because communists and nationalists had to paralyze the parliaments. He formulated the paradoxical - tragic character of the situation as follows: “If a constitutional reform were possible with the existing Reichstag, this constitutional reform would be superfluous. The impossibility of having the constitutional reform carried out by parliament makes it necessary. "

The dual state

From 1936 to 1938 Fraenkel secretly worked on a political-scientific analysis of the Nazi state, which he later referred to as the “original dual state”. He used newspaper reports, magazine articles, laws, ordinances, court decisions and his own experience as material for this study. In the United States, he revised his manuscript, which had been smuggled out of Germany shortly before Fraenkel's emigration. Fraenkel defused genuinely political passages in favor of a more scientific representation. He also added a few paragraphs to help the Anglo-American reader understand his theses.

Fraenkel divided his study into three parts: Part one is dedicated to the legal system of the dual state. In the second part the author analyzes its legal doctrine and in the third part the legal reality of the dual state takes center stage.

According to Fraenkel, the system of rule under National Socialism consists of two areas: The normative state is characterized by the existence of traditional and new legal provisions that are fundamentally based on predictability and, in this function, serve to maintain the private capitalist economic order. In this sphere, laws, court decisions and administrative acts would still be valid; the private property is protected - but not that of the Jews - and contract law still essential.

In contrast to this, the state taking action is not based on rights , but solely on considerations of situational and political expediency. Decisions would be made "as the case may be". In this sector “the standards are lacking and the measures prevail”.

Fraenkel emphasized that , in case of doubt, the state of action could prevail against the normative state - the persecution of Jews in the Nazi state was a central example of this. What counts as political and therefore belongs to the state in which the action is taken is not decided by the courts , but by political authorities.

The Dual State received intense attention from the American public shortly after its publication. In Germany, however, the book was difficult to get even after 1945. For personal reasons, Fraenkel actually no longer wanted to deal with the Nazi state after 1945. Finally he was persuaded to contribute to a German-language edition of the Dual State . The German version, which appeared in 1974, was widely used and recognized; The three central terms double state , normative state and state of measures were received comprehensively and were often used in the analysis of the National Socialist German Reich. In the meantime, the terms state of measure and state of norms have also been used to analyze Stalinism .

The American system of government

Ernst Fraenkel's America Studies encompass a variety of books, essays, lecture manuscripts, and lexicon articles that he wrote in the 1950s and 1960s. A key message of these texts is that the crisis in the democratic systems in the first third of the 20th century did not necessarily lead to the failure of democracy and the implementation of totalitarian forms of government , but could be overcome within the framework of the rule of law and the competitive economy. The form and interaction of the political institutions, economic strength and the distance to the European crisis region all interacted with the central importance of political culture in the United States for Fraenkel . His American studies also served the purpose of counteracting distortions and prejudices against the United States in Germany.

His book The American Government System, published in 1960 and published four times up to 1981, is considered the main work of American studies . Fraenkel sees its subject “ holistically ” by understanding it as a product of historical processes, as a legal system and as a social reality. He successively analyzes the " traditional " (according to Fraenkel, the orientation towards unwritten English constitutional law, common law , the US constitution, the colonial heritage and the philosophy of the Enlightenment ), the "democratic", the " federal " and the "constitutional" “Component of the US system of government . This is followed by a summary of the "American government process". The political scientist emphasizes the importance of group plurality as well as the political negotiation processes between groups, between different individual states and between individual states and federal authority . In addition, he recognizes in the rule of law component, more precisely: in the rule of law , a strongly anti-totalitarian tendency, which is not aimed at political homogenization, but guarantees the coexistence, cooperation and opposition of autonomous social groups. An important feature of the American system of government is the guarantee that the individual can develop as a member of an ethnic , religious or national group. The American system of government also maintains stability through natural law . The notion of inalienable rights is established in the United States and the basis of all positive law .

Fraenkel's work was received very positively in the Federal Republic of Germany: Hans-Ulrich Wehler saw it as "a memorable, almost programmatic theoretical conception of political science" and that the book had the potential to become a standard work. Also Horst Ehmke called Fraenkel's study "the best funded and most cohesive representation of the American system of government that we possess." Ekkehart Krippendorff made the study compulsory reading for political scientists. After Charlotte Lütkens , Fraenkel found a new and necessary approach to his subject of investigation. Winfried Steffani saw the study as a pioneering achievement of comparative government theory in Germany.

Fraenkel did not share widespread fears of an Americanization of Europe. He emphasized that there was no one-sided process of cultural, political or economic penetration, but reciprocal processes of adaptation and change. This was shown by the reform of the American civil service and authorities, influenced by German and other continental European experiences, the establishment of a standing army and the establishment of the social constitutional state in the United States.

Fraenkel only occasionally dealt with the foreign policy of the United States , but without condemning it. For example, according to Fraenkel , the military intervention in Vietnam moved within the framework of the Truman Doctrine , which was aimed at containing communist expansion plans .

Germany and the western democracies

Fraenkel did not develop his theory of pluralism and democracy in a coherent script. Rather, it emerged step by step as a sequence of essays and lectures. The American political scientist published this in 1964 as an anthology under the title Germany and the Western Democracies , which is now also considered a classic. His contributions were not only descriptive, but were intended to help shape the self-image of the Federal Republic. The Federal Republic should be understood as a Western democracy: "Fraenkel is about empiricism and justification of liberal-democratic orders."

Fraenkel assumes that the consideration of the political process must start from the existence of different interests in society. These should not be suppressed, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and, more pointedly, Lenin and Carl Schmitt had demanded and as it was violently practiced in the totalitarian systems of Stalinism and National Socialism . According to Fraenkel, representatives of individual interests must be able to organize themselves in groups and participate in the political process. According to Fraenkel, the controversial sector is available to form, articulate and pursue different interests . Disputes between different interests are constitutive for the formation of political will. These disputes resulted in a political compromise that balances the various interests. According to Fraenkel , the institutions for finding compromises are parties , parliaments , governments and administrations . They adhered to constitutionally secured procedures. According to Fraenkel, controversies and compromises are strengths of democracy, not weaknesses. They served to determine the common good , which only emerges after the political process ( a posteriori ) and does not precede it a priori .

In the controversial sector , the regulated articulation and resolution of conflicts of interest can only succeed if there is a non-controversial sector . This consists of a comprehensive consensus on formal rules and on the limits and specifications of the decision-making process, in a common cultural basis for all pluralistic groups. Constitutions thus play a central role in this sector. In the non-controversial sector, there are central values that must be recognized if the political process is to succeed. These values are not arbitrary. Fraenkel counts among these values in particular those that are part of the natural law tradition. In various writings he calls exemplary " social [...] justice ", the "commandments [...] of social ethics ", the "regulative ideas of justice and fairness ," the human rights , freedom , the social state of law , the right of association , the principle of Majority decisions, the principle of general, equal, free and direct elections, equality before the law , the principle of social security , the neutrality of the state in religious matters, the prohibition of torture , the principle of public judicial proceedings , compulsory education and free attendance at school, as well as civil marriage .

His reflections on a pluralistic democracy are an intellectual counter to National Socialism and Stalinism, which reacted with violence to heterogeneous forces. With his concept he made a contribution to the westernization of the Federal Republic. With his appreciation of conflict and compromise, he contradicted the still relevant preferences for homogeneity (" Ideas of 1914 ") and the traditions of the authorities , which were accompanied by distance from parliaments, parties, interest groups and lobbying ("association fraud"). In his anthology from 1964, Fraenkel also considered expanded opportunities for plebiscitary participation and called for the representative elements of the system of government to be supplemented.

Fraenkel is considered by the pluralism theorists to be a co-founder of so-called neopluralism. Such are thinkers who consciously understood their concept of pluralism as a negation of authoritarianism and totalitarianism, who had previously rejected and eliminated pluralism. Neopluralists emphasize the need for the recognition of basic rights , a heterogeneous social structure, the autonomy of the decision-making process, the mandatory validity of the rule of law and the principles of the welfare state, and the thesis of the a posteriori nature of the common good. They do not turn against the state's claim to sovereignty , but against its claim to totality .

Critics of Fraenkel's model of pluralism counter that certain interests cannot be organized, or only with difficulty, and very often can only assert themselves that are particularly conflictual. The state is on the defensive against powerful interest groups. Proponents of Fraenkel's line of thought see such objections as empirically justified, but refer to the normative dimension of the theory and adhere to it.

The concept of pluralism did not generate a lot of echo in science alone. The Federal Constitutional Court evaluated “pluralism” as a structural element of the Basic Law. At the same time, the term “pluralism” has entered everyday language .

Selected Works and Collected Writings

Selected Works

- On the sociology of class justice , Berlin, Leipzig 1927.

- The dual state. A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship . Transl. from the German by EA Shils, in collaboration with Edith Lowenstein and Klaus Knorr, Oxford University Press , New York [u. a.] 1941 (German: Der Doppelstaat. Law and Justice in the "Third Reich" . Reverse translation from English by Manuela Schöps in collaboration with the author, European Publishing House , Frankfurt am Main 1974, ISBN 3-434-20062-2 ) .

- The American system of government. A political analysis , Westdeutscher Verlag, Cologne, Opladen 1960.

- Germany and the Western Democracies , Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1964.

Collected Writings

-

Collected writings , Nomos Verlag, Baden-Baden 1999 ff.

- Volume 1: Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , (edited by Alexander von Brünneck with the collaboration of Rainer Kühn), 1999, ISBN 3-7890-5825-4 ( table of contents ).

- Volume 2: National Socialism and Resistance , (edited by Alexander von Brünneck), 1999, ISBN 3-7890-5826-2 .

- Volume 3: Reconstruction of Democracy in Germany and Korea , (edited by Gerhard Göhler with the assistance of Dirk Rüdiger Schumann), 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6105-0 .

- Volume 4: American Studies , (edited by Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn with the collaboration of Cord Arendes and Peter Kuleßa), 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6161-1 .

- Volume 5: Democracy and Pluralism , (edited by Alexander von Brünneck), 2007, ISBN 978-3-8329-2114-9 ( table of contents ).

- Volume 6 .: International politics and international law, political science and university policy , (edited by Hubertus Buchstein and Klaus-Gert Lutterbeck with the collaboration of Katja Staack and Eva-Maria Reinwald), 2011, ISBN 978-3-8329-5631-8 ( table of contents ).

- A seventh volume is planned, but not yet published (as of April 2020). As a register volume, it should contain a complete bibliography of Fraenkel's writings as well as an index of persons and subjects.

attachment

literature

- Susanne Benzler: Enlightened constitutional law - Ernst Fraenkel . In: Michael Buckmiller , Dietrich Heimann, Joachim Perels (eds.): Judaism and political existence. Seventeen portraits of German-Jewish intellectuals . Offizin-Verlag, Hannover 2000, ISBN 3-930345-21-8 , pp. 327-358.

- Alexander von Brünneck: Ernst Fraenkel 1898–1975. Social justice and pluralistic democracy. In: Kritische Justiz (Ed.): Controversial jurists. Another tradition. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1988, ISBN 3-7890-1580-6 , pp. 415-425.

- Hubertus Buchstein , Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkel. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 .

- Gerhard Göhler : Ernst Fraenkel (1898–1975) . In: Eckhard Jesse , Sebastian Liebold (Hrsg.): German political scientists - work and effect. From Abendroth to Zellentin , Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2014, pp. 261–274, ISBN 978-3-8329-7647-7 .

- Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life. Campus, Frankfurt 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38480-1 ( review by H-Soz-u-Kult .).

- Siegfried Mielke (Ed.) With the collaboration of Marion Goers, Stefan Heinz , Matthias Oden, Sebastian Bödecker: Unique - Lecturers, students and representatives of the German University of Politics (1920-1933) in the resistance against National Socialism . Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86732-032-0 , pp. 205-213 (short biography).

- Thomas Noetzel: Ernst Fraenkel. Regulatory ideas and political order . In: Hans Karl Rupp, Thomas Noetzel: Power, Freedom, Democracy. Beginnings of West German Political Science. Biographical Approaches . Schüren, Marburg 1991, ISBN 3-924800-87-1 , pp. 33-44.

- Robert Chr. Van Ooyen, Martin HW Möllers (Ed.): (Double) State and Group Interests. Pluralism, parliamentarianism, Schmitt criticism in Ernst Fraenkel. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2009, ISBN 978-3-8329-4669-2 .

- Alfons Söllner : Ernst Fraenkel and the westernization of political culture in the Federal Republic of Germany . In: Leviathan - Berliner Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaft , Vol. 30 (2002), pp. 132–154. Reprinted in Alfons Söllner, vanishing points. Studies on the history of political ideas in the 20th century . Nomos, Baden-Baden 2006, ISBN 3-8329-2260-1 , pp. 201-223.

- Michael Wildt : The political order of the national community. Ernst Fraenkel's “dual state” re-examined. In: Mittelweg 36 , 12th year 2003, issue 2, pp. 45–61.

- Michael Wildt: Ernst Fraenkel and Carl Schmitt. An unequal relationship . In: Daniela Münkel, Jutta Schwarzkopf (ed.): History as an experiment. Studies on politics, culture and everyday life in the 19th and 20th centuries. Festschrift for Adelheid von Saldern, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 35–48. ( PDF , accessed December 28, 2011).

- Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in post-war German society. In: Monika Boll, Raphael Gross (ed.): “I am amazed that you can breathe in this air”. Jewish intellectuals in Germany after 1945. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-18909-0 , pp. 317-344.

Web links

- Literature by and about Ernst Fraenkel in the catalog of the German National Library

- Helmut Zenz: Ernst Fraenkel on the Internet

- Ernst Fraenkel. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Michael Wildt : The transformation of the state of emergency. Ernst Fraenkel's analysis of Nazi rule and its political topicality . Version: 1.0. In: Docupedia contemporary history , June 1, 2011

- Peter Steinbach : Ernst Fraenkel - the missionary . In: Der Tagesspiegel , August 20, 2000; Retrieved July 14, 2012

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Bleek : History of Political Science in Germany , Beck, Munich 2001, p. 247.

- ^ Gerhard Göhler: Ernst Fraenkel (1898–1975) . In: Eckhard Jesse, Sebastian Liebold (Eds.): German Political Scientists - Work and Effect , 2014, p. 261.

- ↑ Cf. on the relevance of Fraenkel's Hubertus Buchstein , Gerhard Göhler: Foreword , in: Dies. (Ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkels , Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, p. 7, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 . In more detail also Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 7–13. See also Wilhelm Bleek : History of Political Science in Germany , p. 280, ISBN 3-406-47173-0 .

- ↑ Information on family and school time according to Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 20–29.

- ↑ On Fraenkel's war and revolutionary experiences, see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 29–43.

- ↑ For information on Fraenkel's studies and legal clerkship, see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 44–55.

- ↑ On Fraenkel's activities after completing his studies up to the opening of Simone Ladwig-Winters' own law firm: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 57–60.

- ↑ On this Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 63–65 and pp. 73–75 and p. 77.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck, Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler: Foreword by the editors to the edition of the collected writings by Ernst Fraenkel , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-5825-4 , pp. 9-14, here p. 10.

- ^ Ernst Fraenkel: Constitutional reform and social democracy . In: Society. International Review for Socialism and Politics , Volume 9 (August 1932), No. 8, pp. 109–124. Reprinted in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic . Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 516-529, here p. 523.

- ↑ For example Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Germany and the western democracies , 9th expanded edition, edited and introduced by Alexander von Brünneck, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2001, p. 7– 29, here p. 10 f, ISBN 978-3-8252-3529-1 (UTB).

- ^ Wilhelm Bleek: History of Political Science in Germany , p. 247.

- ^ Lutz Berthold, The constructive vote of no confidence and its origins in the Weimar Constitutional Law, Der Staat, 35, 81–94.

- ↑ December 22, 1932 is given elsewhere. See Michael Heinatz: Ernst Fraenkel , in: Jessica Hoffmann, Helena Seidel, Nils Baratella (eds.): History of the Free University of Berlin. Events - Places - People , Frank & Timme, Berlin 2008, pp. 177–186, here p. 186, ISBN 978-3-86596-205-8 .

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Ernst Fraenkel: The sense of illegal work (1935), online edition of a new edition of this article (PDF; 861 kB).

- ^ Siegfried Mielke, Stefan Heinz (ed.): Functionaries of the German Metalworkers' Association in the Nazi state. Resistance and persecution (= trade unionists under National Socialism. Persecution - resistance - emigration. Volume 1). Metropol, Berlin 2012, pp. 24, 60 f., 68, 82, 112, 189.

- ↑ Dennis Egginger-Gonzalez: The Red Assault Troop. An early left-wing socialist resistance group against National Socialism . Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2018, p. 409 f.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life, Frankfurt 2009, p. 108. On Reinefeld, see the brief information on a website of the VVN-BdA Köpenick and Dennis Egginger-Gonzalez: The Red Shock Troop. An early left-wing socialist resistance group against National Socialism . Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2018, pp. 163 f, 171 f, 179, 409 and 570.

- ↑ On Fraenkel's activities from 1933 to 1938 see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 88–131.

- ↑ See the information about this facility on the New York Public Library website . For the organization cf. Ernst C. Stiefel , Frank Mecklenburg: German Jurists in Exile in America (1933–1950) , Mohr, Tübingen 1991, ISBN 3-16-145688-2 , pp. 25–34. See also Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel as a scholarship holder of the American Committee in Chicago , in: Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkel. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 43-61, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 .

- ↑ On the life of the Fraenkels in the USA until mid-1941 see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 129–163.

- ↑ See the brief introduction in the Guide to the American Federation of Jewish from Central Europe, Inc. Collection 1933–1951 on the Yeshiva University website . "The AFJCE was an umbrella association of various Jewish organizations in the USA, which looked after the newly arrived Jewish refugees from Central and Eastern Europe and referred them to the various Jewish communities and associations in the USA." (Hubertus Buchstein: Ernst Fraenkel als Klassiker?, In : Leviathan - Berliner Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaft , vol. 26 (1998), pp. 458–481, here p. 475.)

- ↑ Ladwig-Winters mentions the Selfhelp for German Emigrants (Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. Ein politisches Leben , Frankfurt 2009, p. 176 and p. 366, note 165), in other places the organization name Self connected with Tillich can be found -help of the Émigrés from Central Europe Inc.

- ↑ For the activities of Fraenkel in the months after his studies see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 164–178.

- ^ Website of the organization .

- ↑ Gerhard Göhler and Dirk Rüdiger Schumann: Foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 3, Reconstruction of Democracy in Germany and Korea , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6105-0 , p. 9–49, here p. 12.

- ↑ See the brief introductory notes on this US facility on the National Archives website .

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 191.

- ↑ Cf. Gerhard Göhler and Dirk Rüdiger Schumann: Foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 3, Reconstruction of Democracy in Germany and Korea , Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 9–49, here pp. 13– 15th

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 412.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 201–209. See above all the letter from Ernst Fraenkel to the Suhr family of March 23, 1946, printed in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 3, Reconstruction of Democracy in Germany and Korea , Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 389–395, esp. P. 391 f. This passage of letters is quoted, for example, by Gerhard Göhler: Ernst Fraenkel - historical and current , in: Siegrid Koch-Baumgarten, Peter Rütters (ed.): Pluralism and democracy. Interest groups - state parliamentarism - federalism - resistance. Siegfried Mielke on his 65th birthday , Bund-Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 2006, pp. 21–38, here p. 27, ISBN 3-7663-3651-7 .

- ↑ On Fraenkel's stay in Korea, see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 210–238.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 221.

- ↑ Gerhard Göhler and Dirk Rüdiger Schumann: Foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 3, Reconstruction of Democracy in Germany and Korea , Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 9–49, here p. 16 f.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 231.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 239 and p. 246–252; Hubertus Buchstein, Klaus-Gert Lutterbeck: Foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 6, International Politics and International Law, Political Science and University Policy , ed. by Hubertus Buchstein and Klaus-Gert Lutterbeck with the assistance of Katja Staack and Eva-Maria Reinwald, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2011, ISBN 978-3-8329-5631-8 , pp. 9–90, here pp. 10 f.

- ↑ Biographical keywords about Pietsch on the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung website .

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 256–259.

- ↑ Alfons Söllner : Ernst Fraenkel and the Westernization of Political Culture in the Federal Republic of Germany , in: Leviathan - Berliner Zeitschrift für Sozialwissenschaft , Vol. 30 (2002), pp. 132–154, here p. 134.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , edited by Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6161-1 , p. 7– 48, here p. 14.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 294.

- ↑ Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in German Post-War Society , p. 329.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 265–267.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 265–267.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 255 and p. 273–276.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 301.

- ↑ On the conflict between Fraenkel and the student movement see Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 318–325; Rudolf Wolfgang Müller : "... when the doorbell rang at 6 in the morning, it was the milkman." Ernst Fraenkel and the West Berlin student movement , in: Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From Socialism to Pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkels , Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 97–113, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 ; Hubertus Buchstein, Klaus-Gert Lutterbeck: Preface to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 6, International Politics and Völkerrecht, Political Science and University Policy , Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 9–90, here pp. 75–84 .

- ↑ AStA wants to sue in court . In: Berliner Morgenpost of April 26, 1967, page 3 (PDF; 617 kB)

- ↑ Claudia Pinl on January 8, 2015 in the eighth Wikipedian salon , video recording on YouTube , 1:24:19–1:25:27.

- ↑ Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in German Post-War Society , p. 332.

- ^ Front page of the Berliner Morgenpost from September 17, 1967 (PDF; 823 kB).

- ↑ Hartmuth Becker , Felix Dirsch, Stefan Winckler : The 68ers and their opponents. Resistance to the Cultural Revolution. Stocker-Verlag, Graz 2003, ISBN 3-7020-1005-X , p. 10.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein, Klaus-Gert Lutterbeck: Preface to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 6, International Politics and Völkerrecht, Political Science and University Policy , Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 9–90, here p. 84; Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in the German post-war society , p. 334 and p. 343, note 52.

- ↑ On this, Marcus Llanque : Ernst Fraenkel and Rätedemokratie , in: Robert Christian van Ooyen, Martin HW Möllers (ed.): (Double) state and group interests. Pluralism - parliamentarism - Schmitt criticism in Ernst Fraenkel , Baden-Baden 2009, ISBN 978-3-8329-4669-2 , pp. 185–205.

- ↑ Radicals dream of Soviet models . In: Die Welt of October 27, 1967, p. 6. (PDF; 794 kB)

- ↑ Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in German Post-War Society , p. 333.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 311.

- ↑ Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in German Post-War Society , p. 331.

- ^ Gerhard Göhler: Ernst Fraenkel (1898–1975) . In: Eckhard Jesse, Sebastian Liebold (Eds.): German Political Scientists - Work and Effect , 2014, p. 269.

- ↑ See Michael Wildt: The fear of the people. Ernst Fraenkel in German Post-War Society, pp. 334–339.

- ↑ See Winfried Steffani: Ernst Fraenkel as a personality , in: Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkels , Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 125–147, here, p. 140, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 .

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 327–333 and pp. 335 f.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, p. 333.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 325–327.

- ↑ Gerhard Göhler: Ernst Fraenkel - historical and current , in: Siegrid Koch-Baumgarten, Peter Rütters (Ed.): Pluralism and Democracy… , Frankfurt / Main 2006, pp. 21–38, here p. 31.

- ^ Simone Ladwig-Winters: Ernst Fraenkel. A political life , Frankfurt 2009, pp. 333–338.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn, foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 15–54, here pp. 35 f, ISBN 3-7890-5825-4 .

- ↑ See on this Rainer Kühn: The writings of Ernst Fraenkel on the Weimar Republic. Labor law as a knot and catalyst , in: Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkel. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 9-28, ISBN 3-7890-6869-1 .

- ↑ Ernst Fraenkel: To the constitution , in: The society. International Review for Socialism and Politics , vol. 9, (October 1932), no. 10, pp. 297-312. Reprinted in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 496-510. Compare Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn, foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 15–54, here p. 44 f.

- ↑ Michael Wildt: Ernst Fraenkel and Carl Schmitt. An unequal relationship , in: Daniela Münkel (Hrsg.): Geschichte als Experiment , 2004, p. 45 ( Pdf version , here p. 11).

- ^ Ernst Fraenkel: Constitutional reform and social democracy , in: The society. International Review for Socialism and Politics , Volume 9 (August 1932), No. 8, pp. 109–124. Reprinted in: Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 516–529.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 15–54, here p. 50– 52.

- ^ Ernst Fraenkel: Constitutional reform and social democracy , in: The society. International Review for Socialism and Politics , Volume 9 (August 1932), No. 8, pp. 109–124. Reprinted in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Baden-Baden 1999, pp. 516–529, here p. 528.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 2nd edition (2001) , in: Der Doppelstaat , 2nd, reviewed edition, ed. and a. by Alexander von Brünneck, European Publishing House, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-434-50504-0 , pp. 12-14.

- ↑ On this, Ernst Fraenkel: Der Doppelstaat , 2nd, reviewed edition, 2001, pp. 141–149.

- ↑ Formulation by Ernst Fraenkel: Der Doppelstaat , 2nd, reviewed edition, 2001, p. 113, there in quotation marks.

- ^ Fraenkel, quoted from Michael Wildt : The transformation of the state of emergency. Ernst Fraenkel's analysis of Nazi rule and its political topicality , Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte , June 1, 2011, p. 3. (Republication of: Michael Wildt: The transformation of the state of emergency. Ernst Fraenkel's analysis of Nazi rule and their political topicality , in: Jürgen Danyel, Jan-Holger Kirsch, Martin Sabrow (Eds.): 50 Classics of Contemporary History , Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, pp. 19-23, ISBN 3-525-36024-X ).

- ↑ On this core thesis see Alexander von Brünneck: Vorwort des Editor (2001) , p. 11.

- ↑ On this, Joachim Detjen: Fraenkel, Ernst (December 28, 1898 Cologne; † March 28, 1975 Berlin) The Dual State , in: Georg W. Oesterdiekhoff (Ed.): Lexicon of Sociological Works , Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2001, p. 201 f , ISBN 3-531-13255-5 .

- ↑ On this Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor (2001) , p. 16.

- ^ Jürgen Zarusky : The Stalinist and the National Socialist Justice. A sketch of the problem from a comparative dictatorship perspective ( accessed on December 26, 2011; PDF; 257 kB). Stefan Plaggenborg : Experiment Modern. The Soviet Way , Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main [u. a.] 2006, ISBN 3-593-38028-5 . See also the review by Stefan Breuer in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , September 1, 2006, p. 41 (accessed December 26, 2011). References to the use of Fraenkel's terms in Stalinism research by Michael Wildt: The transformation of the state of emergency. Ernst Fraenkel's analysis of Nazi rule and its political topicality , Version: 1.0, p. 4.

- ↑ The essentials are tangible in the collected writings. See Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , edited by Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-7890-6161-1 .

- ↑ See Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Preface , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 8-10.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, p. 29 f.

- ↑ Voices including quotations from Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, p. 30 f.

- ↑ Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Foreword , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 39–42.

- ↑ See Hubertus Buchstein and Rainer Kühn: Preface , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 4, Amerikastudien , Baden-Baden 2000, p. 44 f.

- ↑ In 2011 the anthology was published in the 9th expanded edition: Ernst Fraenkel: Germany and the western democracies , 9th expanded edition, edited and introduced by Alexander von Brünneck, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2001, ISBN 978-3-8252-3529-1 (UTB). To assess it as a classic, see Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Germany and the western democracies , 9th extended edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here p. 7. Furthermore Gerd Strohmeier : Ernst Fraenkel, Germany and the Western Democracies, Stuttgart 1964 . In: Steffen Kailitz (Ed.): Key Works of Political Science , VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden 2007, pp. 125–128, ISBN 978-3-531-14005-6 .

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Deutschland und die western democracies , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here p. 7, p. 14 and p 28.

- ^ Thomas Noetzel: Ernst Fraenkel. Regulative ideas and political order , in: Hans Karl Rupp, Thomas Noetzel: Power, Freedom, Democracy. Beginnings of West German Political Science. Biographische Approachungen , Schüren, Marburg 1991, pp. 33-44, here p. 40, ISBN 3-924800-87-1 .

- ↑ On this Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Germany and the western democracies , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here p. 15 f.

- ↑ See Alexander von Brünneck: Editor's Foreword to the 9th Edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Deutschland und die western Demokratie , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 5, Democracy and Pluralism , p. 89.

- ↑ Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 5, Democracy and Pluralism , p. 84.

- ↑ Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 5, Democracy and Pluralism , p. 279.

- ^ Ernst Fraenkel: Collected Writings , Volume 5, Democracy and Pluralism , pp. 339–341.

- ↑ References to these concretizations of values in the non-controversial sector can be found in Alexander von Brünneck: Introduction to this volume , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 5, Demokratie und Pluralismus , Nomos, Baden-Baden 2007, ISBN 978-3 -8329-2114-9 , p. 19, note 49.

- ^ Gerhard Göhler: Ernst Fraenkel (1898–1975) . In: Eckhard Jesse, Sebastian Liebold (Eds.): German Political Scientists - Work and Effect , 2014, p. 271.

- ↑ See Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Deutschland und die western Demokratie , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here pp. 20–23.

- ↑ See Winfried Steffani, Introduction , in: Franz Nuscheler , Winfried Steffani (Ed.): Pluralism. Conceptions and controversies , Piper, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-492-01953-6 , pp. 9–46, here p. 29 f. See also Rainer Kühn: Classics of Political Literature. Ernst Fraenkel: “Germany and the Western Democracies” , in: Deutschlandfunk , July 20, 2009 (accessed on July 30, 2012). Furthermore Winfried Steffani: Ernst Fraenkel as a personality , in: Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler (ed.): From socialism to pluralism. Contributions to the work and life of Ernst Fraenkel , Baden-Baden 2000, pp. 125–147, here, p. 139.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Germany and the western democracies , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here p. 26 f.

- ↑ Kurt Sontheimer , for example, formulated a compact defense of the concept of pluralism against criticism from the left : The pluralism and its critics , in: Günther Doeker, Winfried Steffani (ed.): Klassenjustiz und Pluralismus. Festschrift for Ernst Fraenkel on his 75th birthday on December 26, 1973 , Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1973, ISBN 3-455-09081-8 , pp. 425–443.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck: Foreword by the editor to the 9th edition , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Deutschland und die western Demokratie , 9th expanded edition, Baden-Baden 2011, pp. 7–29, here p. 27.

- ↑ Alexander von Brünneck, Hubertus Buchstein, Gerhard Göhler: Foreword by the editors to the edition of the collected writings by Ernst Fraenkel , in: Ernst Fraenkel: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Law and Politics in the Weimar Republic , Baden-Baden 1999, p. 13 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fraenkel, Ernst |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-American political scientist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 26, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 28, 1975 |

| Place of death | Berlin |