F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and iron foundry

| F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and iron foundry | |

|---|---|

| legal form | Corporation |

| founding | 1842 |

| resolution | 1883 |

| Reason for dissolution | Bankruptcy / Liquidation |

| Seat | Berlin , Germany |

| management | Friedrich Wöhlert |

| Number of employees | 2000 |

| sales | 10 million RM (estimated; as of 1874/1875) |

| Branch | Locomotive, machine, furnace and vehicle construction |

The F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt und Eisengiesserei Actien-Gesellschaft was an important manufacturer of locomotives , machine tools , cast iron goods , agricultural equipment , steam cars and iron constructions in the 19th century. The company emerged from the F. Wöhlert'schen Maschinenbau-Anstalt .

Friedrich Wöhlert

Johann Friedrich Ludwig Wöhlert (1797–1877) came from Kiel . He trained as a carpenter , went in 1818 to Berlin and worked until 1836 for the New Berlin iron foundry from Franz Anton Egells (1788-1854). Wöhlert was friends with August Borsig (1804–1854), whom he had met here. After Borsig had made in 1836 on their own, he took Wöhlert soon as foreman in the A. Borsig'sche Eisengießerei- and engineering institution . Wöhlert worked here from 1837 to 1841 and was also involved in the construction of Borsig's first locomotive. He then took over the position of head of the Berlin branch of the Royal Prussian Iron Foundry , which in turn was a subsidiary of the Prussian Sea Handling Society .

Company history

F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt

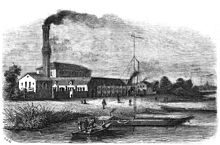

The company was founded in 1842 or 1843 as F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt . The domicile was on Chausseestrasse , Oranienburger Vorstadt (today Berlin-Mitte ). The area was popularly called Tierra del Fuego because of its numerous steam-powered industrial plants. Wöhlert's mechanical engineering institute was located both near the Borsig factory (Chausseestrasse 1) and the Egells iron foundry (Chausseestrasse 3–4). In 1852 the newly founded iron foundry and machine factory L. Schwartzkopff moved into its administration building at Chausseestrasse 19-20.

Wöhlert was helped with the financing by the Prussische Seehandlungs-Societät , which, as mentioned, was backed by the Prussian state. So the company benefited from government perks. This promotion of the machine industry was mainly driven by the head of the royal Prussian trade institute , Christian Peter Wilhelm Friedrich Beuth (1781–1853), who had previously supported Egells and others. Prussia hoped that it would connect with the then leading British steam technology; Egells showed that they did not shy away from industrial espionage either.

Initially, machine tools , steam engines , steam-driven pumps , steam hammers , cranes , mill equipment and stills were manufactured at Wöhlert . With the opening of its own iron foundry in 1844, iron structures were also added. In 1846 the first own steam hammer went into operation and a further one was inaugurated the following year. Now it was also possible to manufacture castings to order, shipping company requirements, entire bridge parts and fire-proof roof structures. Even cast-iron cannons , sawmills and railway supplies such as switches or turntables left the Wöhlert factory for a while.

In 1850, an agricultural machinery production facility was incorporated, housed at Chausseestrasse 50 and managed by G. Beermann . Wöhlert also had a wide range to offer in this area.

An impressive example of Wöhlert's iron constructions must have been the fireproof roof structure of the new Berlin waterworks at Stralauer Tor , which was inaugurated in 1856 and whose pumps were operated by steam power. At Wöhlert, iron art castings were also made for town houses or sacred buildings , such as the cross of the church in Hangelsberg ( Brandenburg ), where Friedrich Wöhlert had his summer residence.

Locomotives

Of course, Friedrich Wöhlert also wanted to build locomotives as soon as he had the opportunity. In 1844 the production of tenders began and from 1846 Wöhlert took on orders for the modernization and maintenance of locomotives .

In 1848 the "Marschall Vorwärts" (named after Prince Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher ) was the first to leave the plant. The buyer of this Crampton type steam locomotive with a 1A1 wheel arrangement was the Mecklenburg Railway Company .

The second locomotive was not built until 1851. In that year Hermann Gruson (1821–1895) came to the locomotive department as chief engineer. By 1853 he designed locomotives with the wheel arrangement 1A1, 2A (Crampton), 1B and above all C. Under Gruson, the later mechanical engineering entrepreneur Rudolf Ernst Wolf (1831-1910) was also employed as a volunteer and worked, among other things, in locomotive construction.

Wöhlert specialized in standard-gauge and powerful locomotives. The sale of these high-quality locomotives that were expensive compared to competing products such as those from Borsig was slow. It seems that this is why Wöhlert separated from Gruson and his close colleagues (like Wolf). In 1857 not a single locomotive could be sold.

Wöhlert developed a process for welding wrought iron wheels and found a market for it. The company also produced wheels for wagon manufacturers without their own foundry.

The crisis in the 1850s could be overcome and from 1860 the locomotives sold in increasing numbers. Wöhlert employed around 800 workers in 1864, and over 1000 by 1870. 90 locomotives were produced that year. On average, a new locomotive was built every other day between 1870 and 1873. The largest number, depending on the source 130 or 151 copies, left the factory in 1874. Around 2000 people were now employed. Wöhlert locomotives were also sold to Russia and Austria in the years to come.

Sales difficulties

After these peak times there was another sharp drop in sales in locomotive construction. As early as 1876, production was cut back and short-time work was introduced.

Up to the cessation of locomotive production in 1882, 94 locomotives were built; Only one was built in 1880, and probably none at all in 1881. In 1882, ten locomotives seem to have been delivered to the Hungarian State Railways.

Details of the serial numbers 712–727 have not survived. In addition to locomotives, these numbers can also have been used for other products, for example from the Elbinger wagon factory in Elbing (East Prussia) , which was acquired in 1880 . Wöhlert also experimented with steam wagons without rails , mostly based on a French patent .

Stock company and "formation fraud"

In 1870, at the beginning of high industrialization in Germany , a relaxed stock corporation law came into force in the Kingdom of Prussia. In connection with a flood of money from reparations payments made by France after its defeat in the war of 1870/1871 and a general economic euphoria, this triggered a real boom of "startups". The formal legal reorganization of an existing company as a stock corporation (AG) was thus designated. In Prussia alone, around 780 stock corporations were "founded" between 1871 and 1872, far more than twice as many as between 1790 and 1870. These practices are often associated with the "railway king" Bethel Henry Strousberg (1823-1884); in the "case" Wöhlert no direct reference is proven, but the methods used were similar.

The revised Stock Corporation Act of 1870 had some serious shortcomings to the detriment of investors. Scandals were not long in coming. In sum, the dubious "ups" were also economically harmful because trading in these securities swelled the value of the companies artificially and a bubble was created. Ultimately, they were one of the causes of the founder crash of 1873, with a long economic crisis that followed, called the Great Depression .

The F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and Eisengiesserei was also affected by this type of bag tailoring in 1872 . Friedrich Wöhlert, now 75 years old, in poor health and without a successor, had agreed to sell his company. The well-known Hermann Geber and consorts appeared as “forerunners”, i.e. investors who acquired the company for the purpose of converting it into a stock corporation . They paid an apparently highly inflated price for the company and Friedrich Wöhlert was generous afterwards:

“Certain salespeople, like Wöhlert and others, were delighted at the enormous purchase price that they had received; Distribute amounts of up to 50,000 thalers and more among their former officials and workers. "

In February 1872, Geber and Consorten brought the company, which was still doing well at the time , to the stock exchange with the help of Richard Schweder , the chairman of the board of the Preussische Boden-Credit-Actien-Bank . The new owners issued shares with a nominal value of almost ten million marks. That was again significantly more than they had paid for the company themselves. Usually the banker commissioned with the IPO also received a high “compensation” for his efforts, which was also raised through the share purchases. Unsurprisingly, the tampering with this security issue resulted in the nominal value of all shares in issue significantly exceeding the value of the "incorporated" company. The speculative business was accompanied by a detailed prospectus and marketing measures such as controlled, benevolent reporting in the newspapers.

It is not known whether Wöhlert also tried, as in many other cases before, to place the shares above par . In any case, this "foundation" did not go smoothly at all. Issued at a time when share trading was still flourishing and oversubscriptions were regularly taking place , Geber had already struggled to sell the Wöhlert shares. From the end of 1874 to the end of 1875, the journalist Otto Glagau (1834-1892) reported in a critically snappy series of articles for the journal Die Gartenlaube on the fraudulent start-up , its actors and the economic effects. He also mentioned the Wöhlert emission several times; Not least because of this, this also became a case for the judiciary . The public prosecutor's office started investigations against the author of the prospectus. The prominent lawyer and member of the Reichstag, Karl Joseph Wilhelm Braun (1822-1893), whose name had also been brought into play by Glagau , was also targeted . and who, according to this source, was involved in several other "foundations". None of the signatories of the prospectus or otherwise involved in the issue of the Wöhlert shares was ultimately held responsible; In the case of the prospectus, it was “agreed” that someone who had already died would have been responsible. In retrospect, the "Wöhlert case" turned out to be one of the more important "founder" scandals.

More difficulties

Friedrich Wöhlert remained chairman of the supervisory board for a short time after his company was sold . After the IPO, the company's upswing lasted only a short time. By the time he passed away in 1877, it was already on a downward trend that was to intensify dramatically. There was short-time working in parts of production, which affected 450 workers.

A slight upswing from 1879 following the founder crash came too late for the company, which was faced with insolvency proceedings in 1879 . At the beginning of 1880 a bond was issued to reschedule the company and serve new business areas. The success was moderate, but at least allowed production to continue for the time being. Business reached its low point in the same year, when only a single locomotive could be sold and sales fell to just 115,000 marks. As early as 1876, the demand for Wöhlert locomotives was so low that their production was scaled back. 94 locomotives had been delivered up to 1882. Ten of them went to the Hungarian State Railways in 1882.

Steam car license Amédée Bollée père

The mentioned attempts to diversify the company included the production of agricultural equipment, which began in 1879, and, as early as 1878, attempts with rail- less steam wagons that were to be reproduced under license. From 1879 at the latest, Wöhlert began experimenting with cars made by the French steam pioneer Amédée-Ernest Bollée (1844–1917). This was a respected bell founder , manufacturer and inventor in his homeland , who is also known as Amédée Bollée (father) , in contrast to the no less successful son Amédée-Ernest-Marie Bollée (1867–1926) , who worked in the same field . The second son Léon (1870–1913) was later a successful automobile manufacturer .

Le Cordier

In October 1875, Bollée's father caused quite a stir when he drove the L'Obéissante ("the obedient"), the first steam car he built, from Le Mans to Paris . He only needed 18 hours for this distance of around 210 km. Bollée met the engineer Léon Le Cordier in Paris. A business relationship developed; Le Cordier acquired the rights to use the L'Obéissante drive for most of the continental European countries for his Société Fondatrice . To this end, he made contacts with the Austro-Hungarian monarchy . Amédée Bollée even demonstrated his steam trolley to Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916) and his court. Despite the triumphant success of the advertising event in Vienna , there was no marketing. However, new opportunities arose in the Kingdom of Prussia through the Berlin businessman Berthold Arons from the well-known Arons banking family . In August 1880, Le Cordier traveled to Berlin with two steam cars. On the one hand it was the six-seater, open La Mancelle ("the one from Le Mans") and a heavy tractor with both civil and military uses, called L'Élisabeth .

This was followed by a series of successful performances in front of a large audience including members of the imperial family. In September an agreement was signed between Wöhlert, Le Cordiers Société Fondatrice and the private banking house Gebrüder Arons , which had the purpose of developing steam cars using the Bollée patents. The main goal was to develop buses for long-distance connections from Berlin to metropolises in the east. It can be assumed that the L'Élisabeth tractor should be further developed accordingly.

Berthold Arons and Le Cordier also founded the Centrale Dampfwagengesellschaft , which was supposed to evaluate further Bollée patents in Germany, Russia and other European countries. The operation of steam-powered rental cabs was also considered. The "Bollée-Wöhlert steam powerhouse" was a replica of Bollées La Mancelle , which Bollées La Mancelle wanted to continue to offer independently in France and the United Kingdom and therefore had retained the rights of use for these countries. A sales catalog from 1881 with the title The New Steam Locomotive System, Invented By Amadeus Bollee in Le Mans mentions the introduction of the vehicle by the Arons brothers, Banquiers Zu Berlin and the Wohlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt . The existence of this catalog suggests that not only a production on behalf of the Central Steam Car Company was envisaged, but that the steam cab should also go on the free market.

Wöhlert-Bollée steam trolley

The Wöhlert steamer was a license replica of the La Mancelle . The vehicle had a coal-fired standing boiler with a stand for the heater ("chauffeur") in the rear. The machine was housed under a hood at the front, probably for the first time in the history of the automobile. A very modern solution was the power transmission by means of a cardan shaft from the machine to the centrally mounted differential . From there it was passed on to the rear wheels via two chains . The use of a cardan shaft is probably the first in motor vehicle construction, the arrangement anticipates the “Système Panhard” developed by Émile Levassor by over ten years. The cab was protected by German imperial patents. The wheel arrangement was 1'A n2t.

Bollée himself built around 50 copies of his Mancelle , which can therefore be regarded as the first production car. The vehicle was designed as a six-seater and could be ordered with an open body as a carriage or half-open as a post chaise ; the latter resembled a landaulet .

According to one theory, 16 serial numbers (712 to 727) that have not yet been assigned to vehicles can be assigned to such Wöhlert-Bollée steam hitchhikers with the above-mentioned wheel arrangement; but this is not considered proven.

Wöhlert-Bollée tractors, tractors and buses

L'Élisabeth , completed in 1879, was a sister model of the La Marie-Anne road locomotive that Bollée had offered the French army as an artillery tractor. With 100 hp, the tractor had a three-speed gearshift and was able to pull a trailer load of 35 tons over a six percent incline. The construction followed that of the Mancelle , but was designed much more massive. A tender carried a supply of coal and water. The possibility to drive the tender with an additional power transmission with the steam engine was innovative.

The French government showed no interest, although the huge, 20-ton vehicle type was able to prove its efficiency with an impressive demonstration in 1879. After this rejection, Bollée and Le Cordier saw themselves in a position to offer the vehicle in Germany for both military and civil purposes. The fact that so shortly after the end of the war of 1870–1871 , which was unfavorable for France, tests were also carried out with a version of the tractor as an artillery tractor for the Prussian army was noted very negatively by parts of the French press and polemical articles appeared against Amédée Bollée even brought him close to a traitor to the fatherland. The campaign hurt him and he withdrew completely from the automobile business, which he passed on to his son Amédée, also for financial reasons and under pressure from the partners within his family.

La Marie-Anne was built to order, L'Élisabeth seems to have been a demonstration model.

Occasionally there are reports of a steam omnibus which could have been a converted Elisabeth- type tug . The participation of Le Cordiers Société Fondatrice in the project speaks for the fact that it actually existed ; Here it was about the establishment of road-dependent long-distance connections.

The end of the steam car development

For the company, these new developments were always about developing marketable products as quickly as possible in order to stabilize the financial situation. When the Berlin road police finally forbade further testing of the almost series-ready designs because the almost 5-ton tractor damaged the pavement and resulted in "disadvantageous interventions in the order of general traffic", this meant the end of the entire project. including the steam cabs, which are about half as heavy.

Le Cordier and the Centrale Dampfwagengesellschaft were then forced to file for bankruptcy. In the absence of active players , both Wöhlert and Bollée suffered great losses.

Elbinger Waggonfabrik

Despite - or rather: because of the financial problems, Wöhlert also invested in 1880 in the purchase of production facilities from the former wagon factory Elbinger Actien-Gesellschaft for the manufacture of railway material in Elbing (East Prussia) . Like the steam car experiments, this acquisition should also be seen against the background of diversification, as wagons were in demand and Wöhlert was already a well-known component manufacturer with its wheels and chassis.

The Elbinger Waggonfabrik was founded in the 1860s as Hambruch, Vollbaum & Companie and has been managed by Paul Liebert (1846–1909) since 1871 . It was taken over shortly afterwards by the aforementioned Bethel Henry Strousberg. As a result of the founder crisis in 1873 and Strousberg's fall and imprisonment in Russia , his empire was dissolved. Wöhlert did not acquire the company in liquidation, only the factory in Elbing. After Wöhlert's demise, these systems came to the ABB Group after a checkered history .

resolution

After the government-ordered failure with the steam automobiles, Wöhlert's owners tried again at the end of 1882 by issuing " priority shares " to interest investors and gain capital. This failed and on June 25, 1883, F. Wöhlert'schen Maschinenbau-Anstalt und Eisengiesserei AG was dissolved by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting. The wagon construction facilities in Elbing were taken over by the Schichau works in Elbing in the same year . In this way, at least one bankruptcy procedure could be avoided.

Locomotive production figures

The mentioned production numbers go from approx. 770, 772 resp. 773, whereby the last number results from the serial numbers assigned. According to the same source, two numbers for “steam drive racks” were assigned in 1870; however, these together form a locomotive.

Remarks

- ↑ Official spelling acc. own securities; see. z. B. gutowski.de

- ↑ Most sources name the house number 29; according to albert-gieseler.de Chausseestrasse 35/36 and luise-berlin.de No. 36/37

- ↑ Schweder is repeatedly associated with start-ups in Glagau; see. also Die Gartenlaube: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin / 4. The "Prospecte". P. 170.

- ^ Quotation taken from Edition Luisenstadt, Berlinische Monatsschrift, issue 3/1996, without citing the source; Hans-Heinrich Müller: Wöhlert - a pioneer in mechanical engineering

literature

- Michael Dörflinger: German Railways: Locomotives, trains and stations from two centuries. Bassermann Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-8094-2849-7 .

- Michael Dörflinger: The big book of locomotives: Illustrated history of technology with the best models in the world. 1st edition. Verlag Naumann & Goebel, 2012, ISBN 978-3-625-13350-6 .

- Wolfgang Messerschmidt: Paperback German locomotive factories. Their history, their locomotives, their designers. 1st edition. Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-440-04462-9 .

- DVD: The German Railway History - More than 175 Years of the Railway. Best Entertainment Studio; Dolby. (2011) FSK free, playing time: 60 minutes.

- Hans Christoph Graf von Seherr-Thoss: The German automobile industry. Documentation from 1886 until today. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1974, ISBN 3-421-02284-4 .

- Hans Christoph Graf von Seherr-Thoss: The German automobile industry. A documentation from 1886 to 1979. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1990, ISBN 3-421-02284-4 . (extended new edition from 1974)

- The new steam locomotion system. Brochure from F. Wöhlert'schen Maschinenbau-Anstalt und Eisengiesserei AG for the Wöhlert-Bollée steam car. 1880.

- Peter M. Fritsch, Günther Wermusch: The calculated error. Stories about speculators and gamblers from yesterday and today . Verlag Die Wirtschaft, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-349-00586-1 , pp. 48-70.

- Otto Glagau: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin / 2. The dance around the golden calf . In: The Gazebo . Volume 4, 1875, pp. 62–63 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Otto Glagau: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin / 3. Founders and Founder Practices . In: The Gazebo . Issue 7, 1875, pp. 115 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Otto Glagau: The stock market and start-up fraud in Berlin / 4. The "Prospecte" . In: The Gazebo . Issue 10, 1875, pp. 170 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Otto Glagau: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin. Collected and greatly increased articles of the Gazebo (1876) forgottenbooks.com; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Max Ring: The Berlin waterworks . In: The Gazebo . Volume 2, 1858, pp. 27–29 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Hans-Heinrich Müller: Wöhlert - a pioneer in mechanical engineering . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 3, 1996, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 16-19 ( luise-berlin.de ).

Web links

- Royal iron foundry Berlin . werkbahn.de; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Machine factory and iron foundry F. Wöhlert, Berlin . werkbahn.de; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Friedrich Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbauanstalt and Eisengießerei Aktiengesellschaft . albert-gieseler.de; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Catalog-30 / F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and Eisengiesserei AG . gutowski.de; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Catalogs-sales / F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and Eisengiesserei AG . encheres.lefigaro.fr; Retrieved January 3, 2015

- F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt and Eisengiesserei AG . spink.com; accessed on January 28, 2015

- August Borsig . albert-gieseler.de; accessed on March 5, 2015

- Winter'sche Papierfabriken A.-G., Altkloster . albert-gieseler.de; accessed on January 27, 2015

- Wroclaw municipal waterworks . albert-gieseler.de; accessed on January 27, 2015

- Elbinger Actien-Gesellschaft für Fabrication von Eisenbahn-Material . hwph.de; Retrieved February 3, 2015

- Liebert, Paul; Company manager, * 1846 Danzig; † March 5, 1909 Berlin in the German biography

- Bollée [Amédée], à Toute Vapeur! gazoline.net (French) accessed April 30, 2015

- Lost Marques: Bollée . uniquecarsandparts.com (English) accessed February 10, 2015

- New steam locomotion system invented (prospectus, Berlin 1880) . iberLibro.com (English) accessed April 30, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Messerschmidt: Taschenbuch Deutsche Lokomotivfabriken (1977), p. 218.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Katalog-30 / F. Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbau-Anstalt und Eisengiesserei AG . gutowski.de

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Hans-Heinrich Müller: Wöhlert - a pioneer in mechanical engineering . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 3, 1996, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 16-19 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- ↑ August Borsig . albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ a b Royal Iron Foundry Berlin . werkbahn.de

- ↑ a b c d e Friedrich Wöhlert'sche Maschinenbauanstalt and Eisengießerei Aktiengesellschaft . albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ Winter'sche Papierfabriken A.-G., Altkloster . albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ albert-gieseler.de: Municipal Waterworks Wroclaw . albert-gieseler.de

- ↑ Max Ring: The Berlin waterworks . In: The Gazebo . Volume 2, 1858, pp. 27–29 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ a b c Messerschmidt: Taschenbuch Deutsche Lokomotivfabriken (1977), p. 220.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h machine factory and iron foundry F. Wöhlert, Berlin . werkbahn.de

- ↑ a b c d Messerschmidt: Taschenbuch Deutsche Lokomotivfabriken (1977), p. 221.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bollée [Amédée], À Toute Vapeur! gazoline.net

- ↑ a b c d Otto Glagau: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin / 3. Founders and Founder Practices . In: The Gazebo . Issue 7, 1875, pp. 115 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ^ A b c d Otto Glagau: The stock market and start-up fraud in Berlin / 4. The "Prospecte" . In: The Gazebo . Issue 10, 1875, pp. 170 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ^ Otto Glagau: The stock exchange and start-up fraud in Berlin / 2. The dance around the golden calf . In: The Gazebo . Volume 4, 1875, pp. 62–63 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- ↑ a b c d e Lost Marques: Bollée . uniquecarsandparts.com

- ↑ a b New steam locomotion system invented (prospectus, Berlin 1881) . iberLibro.com

- ^ German biography: Paul Liebert

- ^ A b Elbinger Actien-Gesellschaft für Fabrication von Eisenbahn-Material . hwph.de