Hubert Wilkins

Sir George Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar (born October 31, 1888 in Netfield , Mount Bryan East near Hallett , South Australia ; † November 30, 1958 in Framingham , Massachusetts ) was an Australian polar explorer , photographer , cameraman , pilot , geographer and reporter . He completed the first powered flight in Antarctica in 1928 .

Wilkins' interest in polar research was widespread. His focus was on researching the influence of the polar regions on the global climate and on exploring unknown areas from the air. But he was also the first to dive under the Arctic pack ice in a submarine .

Life

Early years

Hubert Wilkins was the youngest of 13 children in the family of the sheep farmer Henry Wilkins (called Harry, 1837–1914) and his wife Louisa b. Smith (1863–1928) born. His grandfather, William Wilkins (1810-1845), was one of the first 200 settlers of the British colony of South Australia when it was solemnly proclaimed on December 28, 1836. With his pregnant wife Mary he had made the crossing from England on the brig Emma and went ashore on October 5, 1836 on Kangaroo Island . Harry Wilkins was the first child of European descent to be born in the new colony.

Hubert Wilkins grew up on his parents' farm in Mount Bryan East and experienced the severe drought from 1896 to 1902, which aroused his interest in weather phenomena. On his 17th birthday, his father sold the farm and moved to a cottage near Adelaide . Hubert Wilkins studied at the Australian School of Mines and Industries there , now part of the University of Adelaide as the South Australian Institute of Technology (SAIT) . But soon his interests changed. After seeing his first film in 1905, he gave up studies in 1906 and took up work in a tent cinema . As a stowaway, he went on a ship to Sydney , the center of the Australian film industry at the time, where he began to work as a cameraman .

Photographer and cameraman on behalf of Gaumont Studios

In 1911 Wilkins traveled to England . As a cameraman for the Gaumont Studios and reporter for the Daily Chronicle , he traveled to several countries, including Germany. He learned from the British aviation pioneer Claude Grahame-White (1879–1959) to fly an airplane and experimented with aerial photography . During the First Balkan War he filmed fighting on the Turkish-Bulgarian front. In 1913 he was in Trinidad for Gaumont to make a film about the cocoa industry there for the British chocolate manufacturer Cadbury . From 1913 to 1916 Wilkins took part as a photographer on Vilhjálmur Stefánsson's expedition to the Canadian Arctic . When the Karluk , the ship of the Northern Group, was enclosed by the ice and drifted west, he was one of the five men who left the ship with Stefánsson to hunt caribou on the mainland and return to the Karluk after ten days at the latest . When a hurricane tore the ice between the ship and the mainland two days later, a return was impossible. Wilkins thus avoided the fate of the 25 people remaining on the ship, eleven of whom were killed after the Karluk sank before the last survivors could be rescued on September 7, 1914 on Wrangel Island . He played an important role in the further course of the expedition, with the ships Mary Sachs and North Star maintaining the connection between the southern group on the Coronation Gulf , led by the Canadian zoologist Rudolph Anderson (1876–1961), and Stefánsson's northern group, whose base camp was Wilkins on the Cape Kellett had built on Banks Island . This is remembered today by the names Wilkins Bay ( 73 ° 37 ′ N , 124 ° 10 ′ W ) for a bay on Banks Island and Wilkins Strait ( 78 ° 10 ′ N , 111 ° 0 ′ W ) for the strait between Borden Island in the north as well as Brock Island and Mackenzie King Island to the south.

First World War

Returning from the expedition, Wilkins enlisted in 1917 for military service and was accepted as a second lieutenant in the Australian Flying Corps . His job was to assist Captain Frank Hurley , photographer of Douglas Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition and Ernest Shackleton's Endurance Expedition , filming World War I combat for use in newsreels . Despite his refusal to carry arms, he was awarded the Military Cross twice, first for his attempts to save the wounded in the Third Battle of Flanders and later for leading American soldiers who were their superiors in the Battle of the Saint-Quentin Canal had lost. Wilkins was wounded nine times during his daring missions. The commander in chief of the Australian troops, General John Monash (1865–1931), called him the bravest man in his army.

Race from England to Australia

On March 19, 1919, the Australian government of Prime Minister Billy Hughes offered a prize of 10,000 Australian pounds for the first flight of an Australian crew from England to Australia . The conditions stipulated that the aircraft had to be in Australia on a route via Alexandria and Singapore within 720 hours of take-off and no later than December 31, 1920. Of the six crews that competed for the award, only two made it to their destination, and two were fatally injured. Wilkins took part in the race as the navigator of the pilot Lieutenant Valdemar Rendle in a Blackburn Kangaroo , a British twin-engine biplane that had served as a bomber during the war . The crew also included Lieutenant David Reg Williams and Lieutenant Garnsey Potts. The men carefully prepared for the daring venture. In particular, they practiced instrument flight in order to be able to navigate safely even in poor visibility. Wilkins had equipped the aircraft with additional instruments for this purpose.

On November 21, 1919, the plane took off from Hounslow Heath under a clear sky , but already came across the English Channel in heavy rain and strong winds that changed direction again and again. The machine had to land on a military airfield near Paris. The next day, snowfall prevented the onward flight. The weather also caused problems over the next few days and during an emergency landing near Fréjus on the French Mediterranean coast there were also problems with the engines. The flight ended when the machine had to make an emergency landing in Crete on December 8th . Loss of oil had destroyed an engine. The four-man crew was unharmed. The prize went to the brothers Ross and Keith Smith , who were the only ones who met the conditions with their Vickers Vimy .

British Imperial Antarctic Expedition

John Lachlan Cope (1893-1947) - former member of the Ross Sea Party , the support group for Ernest Shackleton's Endurance Expedition - planned for 1920 to begin a large-scale Antarctic expedition with over fifty participants and a duration of five years. With the Terra Nova , Robert Falcon Scott's ship on his last expedition, he wanted to circumnavigate the entire Antarctic continent and clarify a number of geographical issues. In addition, he planned to use up to twelve Royal Air Force aircraft to explore Antarctica and also to reach the geographic South Pole . Cope filled the post of scientific expedition leader in 1919 with Hubert Wilkins. The heavily underfunded expedition finally started in 1920 with just four people and - disappointingly for Wilkins - without an airplane. In addition to Cope and Wilkins, Thomas Wyatt Bagshawe (1901-1976) as a geologist and Maxime Charles Lester (1891-1957) as a surveyor took part in it. The expedition plan had been changed again. With dogsled Cope wanted from Otto Nordenskjölds old hut on Snow Hill Iceland on the East Coast of the Antarctic Peninsula Drive along to the south and the unknown west and south coasts of the Weddell Sea explore. Without their own ship and with only eight dogs that Wilkins had acquired in the Falkland Islands , the men let themselves be dropped off on Deception Island on December 24, 1920 , in the hope of finding a whaler who would take them to Snow Hill Island. When the footage was withheld because of unpaid bills, Wilkins made the decision to leave the expedition as soon as possible. The difficult ice conditions made it impossible to head for the east side of the Antarctic Peninsula, so Wilkins Cope suggested to be dropped off in Hope Bay at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where three men of the Swedish Antarctic Expedition had wintered in 1903 . From there, the expedition could reach Snow Hill Island by lifeboat. When no whaler was able to approach Hope Bay, the expedition landed on January 12, 1921 at Waterboat Point on an only 213 m long island on the west coast of Grahamland at the entrance to Paradise Harbor . The group failed to cross the peninsula to get to the east side and still carry out the expedition plan. Cope gave up disappointed and left on March 3rd with Wilkins, while Bagshawe and Lester stayed on site to hibernate and, despite poorly equipped scientific instruments , carry out meteorological , geological, glaciological and zoological work.

Quest expedition

Back in New York , Wilkins received from the head of the American branch of Junkers Flugzeugwerke AG the promise to provide him with two seaplanes for an expedition in the Antarctic summer 1921–1922. However, he was persuaded by the British polar explorer Ernest Shackleton to postpone his plans and initially to take part in his quest expedition . Wilkins' hopes of being able to participate as reserve pilot in the first powered flight in Antarctica were disappointed again. Although the expedition was equipped with a seaplane from the Avro Company , this was initially in the depot in Cape Town . When the quest called Rio de Janeiro on November 22, 1921 , where its drive had to be overhauled, Wilkins had a whaler take him to Grytviken , South Georgia , to begin his work as the expedition's biologist and for six weeks hundreds of samples of animals and animals Collecting plants from this little-explored island. After Shackleton's sudden death on January 5, 1922, the expedition under Frank Wild was only continued with a shortened program, so that the aircraft was no longer used. During a stopover in Tristan da Cunha , Wilkins discovered the Wilkins bunting ( Nesospiza wilkinsi ) named after him .

For the Quakers in Russia

Wilkins spent the first months after the Quest expedition in London arranging his collected samples. At the same time he developed plans for a network of around 50 meteorological stations in the polar regions to improve weather forecasts , which he submitted to the Royal Meteorological Society for review. A working group was then formed under the leadership of the British meteorologist Napier Shaw (1854-1945) to examine Wilkins' proposals. His vision finally became reality 28 years later with the establishment of the World Meteorological Organization . While Wilkins was still waiting for an answer, he accepted an assignment from the Quakers in 1922 to report and film the humanitarian aid of the Society of Friends 'Emergency and War Victims' Relief Committee in Russia. The country has suffered a severe famine since 1921 . He visited Moscow and Buzuluk and was received by the Soviet revolutionary leader Lenin .

Wilkins Australia and Islands Expedition 1923–1925

While he was still in Russia, Wilkins received an offer from the Natural History Museum in London to lead a natural history and ethnological expedition to northern Australia. Rare Australian mammals were threatened with extinction before a scientist described them. Wilkins' task was to collect specimens of rare animals and plants and to document the life of the Aborigines photographically and on film. The expedition from Wilkins, the mammalogen Vladimir Kotoff, the botanist J. Edgar Young and the ornithologist OG Cornwell traveled two and a half years through the north of Queensland and the Northern Territory and also visited the islands of Groote Eylandt and Thursday Island . Wilkins' work received high praise from the museum. He was offered to lead another expedition either to Patagonia , Madagascar or Western Australia or to continue the paleontological excavations at the famous Tendaguru dinosaur site after the sudden death of William Edmund Cutler (1875-1925). Wilkins only wanted to promise this for seven to eight months, which is why the museum chose Frederick Migeod (1872–1952). In Australia, Wilkins' travelogue Undiscovered Australia , published in 1928, was received less friendly because of his positive attitude towards the Aborigines and his relentless criticism of the environmental destruction and wanton extermination of native species by the white settlers.

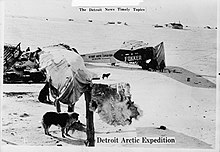

Detroit Arctic Expedition 1926

Wilkins was drawn back to the polar regions. There had been no research trips to Antarctica since the Quest expedition. The golden age of Antarctic exploration had come to an end, and what was to come was a technical era of Antarctic expeditions. The most important technical innovation awaiting its entry into Antarctic research was the airplane, and no polar explorer had more flying experience than Wilkins, who on the other hand was the aviator with the best knowledge in the field of polar research. For his plans for an Australasian Polar Pacific Expedition with a flight from the Ross Sea via King Edward VII Land to Grahamland , he found no sponsor in Great Britain and Australia, so he had to give it up.

Through the mediation of Stefánsson and the director of the American Geographical Society , Isaiah Bowman (1878-1950), Wilkins came in contact with the Detroit Aviation Society , in which financially strong representatives of the Detroit auto industry set the tone. Wilkins managed to get Society's support for an Arctic expedition. Additional funds were raised through an appeal for donations to the Detroit population. A total of over 80,000 people donated, including many school children.

Wilkins formulated the expedition's goals as follows: “ The purpose of the Detroit Arctic Expedition is to explore the area of polar pack ice that has never been seen by humans before. “In 1925 it was not yet finally clear whether there were still unknown land masses in the Arctic polar regions. Wilkins had been a participant in Stefánsson's expedition himself when it discovered other islands in the Canadian Arctic archipelago in 1916. At the same time, the American polar explorer Donald McMillan (1874–1970) had searched in vain for Crocker Land , which Robert Peary claimed to have seen in 1906 from the northwest coast of Ellesmere Island . Another candidate was Keenan Land , which was supposed to be some 500 km north of Alaska . Wilkins was convinced that the plane could answer the question.

In the Netherlands , Wilkins bought two aircraft, a single-engine Fokker F.VIIa and a three-engine Fokker F.VIIb-3m . As a starting point for his flights he chose Point Barrow , the northernmost point of the United States, and as a pilot Carl Ben Eielson , who already had experience with flights in Alaska, and the military aviator Major Thomas George Lanphier (1890-1972). The expedition was not a lucky star. In Fairbanks , a Detroit News correspondent got into one of the propellers when the three-engined Fokker, previously named Detroit , was first launched and was killed. A week later, both machines were severely damaged in crash landings within 24 hours. Wilkins refused to follow his sponsors' request and replace the pilots with others. His team immediately started the repair work. After three weeks the single-engine Alaskian was makeshift repaired and able to fly gasoline to Point Barrow. After three flights the material fatigue was so great that the plane literally fell apart when it took off from Fairbanks. It was still possible to fly the Detroiters to Point Barrow, but the weather did not allow reconnaissance flights over the pack ice that year. The expedition had to cover a total flight distance of 10,000 km north of the Arctic Circle and mostly over unexplored area, but did not reach its goals.

In the meantime Richard E. Byrd had made a flight from Spitzbergen to the North Pole, but according to current knowledge, he did not reach it. Amundsen had flown over the pole with Lincoln Ellsworth and Umberto Nobile in the airship Norge and floated over Point Barrow on May 13, 1926.

Detroit News Wilkins Arctic Expedition 1927/1928

Although some of the sponsors turned away from him, Wilkins was not ready to give up his plans. With financial support from the Detroit News , he procured two Stinson biplanes . On March 29, 1927, Wilkins and Eielson took off on a reconnaissance flight. They wanted to search for land in the sector of the Arctic Ocean, which was bounded to the east by the flight route of the Norge and to the west by the drift of the Jeanette in 1878. Even before they had reached their destination at 80 ° N, 180 ° E / W, they had to land on the pack ice at 77 ° 45 ′ N , 175 ° 0 ′ W due to engine problems . Wilkins used the stay to do a depth sounding and was surprised to find that the sea under the ice was almost 5000 m deep. This made the existence of nearby islands unlikely. After two hours of repairs, the Stinson was able to take off again, but had to land again ten minutes later. After an hour it went on. When the plane finally gave up, Eielson and Wilkins were about 120 km from the mainland. What was left for them was a walk back to the coast. While they waited for a five-day blizzard to end, they continued to drift with the pack ice, leaving them more than 150 km from Point Barrow when they set out. On the 13-day march that ended at the trading post at Beechey Point, Wilkins benefited from his survival techniques learned from Stefánsson. Because Eielson had frostbite on his fingers, he could no longer fly that year. After a failed attempt to fly to Greenland, Wilkins left Point Barrow in early June.

In 1928 Wilkins had lost its sponsors. After all, the Detroit News had been fair enough to pay all the bills and let him have the remaining plane, which is why the name of the expedition remained unchanged. Looking around for a more reliable aircraft, Wilkins came across the Lockheed Vega , for which he sold his other machines. After proving Keenan Land does not exist the previous year, he wanted to continue his search for land further east this time, where Peary Crocker Land and Frederick Cook claimed to have seen Bradley Land . On April 15, he took off with Eielson in Point Barrow and flew first to the northeast to position 84 ° N, 75 ° W, between Ellesmere Island and the North Pole, from there initially to the south. The view was good and no islands to be discovered. From the clouds in the east he could tell that the weather in Svalbard would be bad. Of the two options of continuing the flight or landing on Ellesmere Island to wait for better conditions, he chose the first, in agreement with Eielson. After a total of 20 hours of flight, the Lockheed Vega came to Svalbard in a storm and had to land on the Daudmannsodden peninsula on the Icefjord . Only after five days was she able to cross over to the other side of the fjord to the mining settlement of Green Harbor . Just a year after Charles Lindbergh's flight across the Atlantic, Wilkins and Eielson had made the first transarctic flight from America to Europe and found that there was no more unknown land to be discovered between North America and the North Pole.

Wilkins was honored worldwide for his achievement. Amundsen declared: "Nowhere and at no time has a flight been undertaken that is comparable to this one." A special reception was given to Wilkins and Eielson in Berlin . Walther Bruns (1889–1955) and Arthur Berson , two members of the board of directors of the International Study Society for Exploring the Arctic with Aircraft (Aeroarctic) , came to Copenhagen with the D 1000 , a Junkers G 24 owned by the Reich , to pick up the polar pilots. From Warnemünde , the D 1000 received an honorary escort of six aircraft, which were joined by another squadron of seven aircraft off Berlin. The two formations flew over Tempelhof Airport several times , where a large crowd had gathered and cheered the two planes after landing. Wilkins and Eielson became the first honorary members of the Aeroarctic and received the Carl-Ritter-Medal of the Gesellschaft für Gekunde zu Berlin .

In London, Wilkins was received and ennobled by King George V. The Royal Geographical Society honored him with the Patron's Gold medal .

In July 1928 Wilkins met the Australian actress Suzanne Bennett (1901-1975) in New York at a celebration given in his honor, whom he married on August 31, 1929.

Wilkins-Hearst Antarctic Expedition 1928–1930

With the new fame through the Transarctic flight, it was not difficult for Wilkins to find sponsors for the long-planned Antarctic expedition. American media tycoon William Randolph Hearst paid him $ 25,000 for exclusive rights to the coverage. The Australian Vacuum Oil Company made a further $ 10,000 available, while Heintz & Kaufman in San Francisco equipped the two aircraft of the expedition with radio technology. The Norwegian whaling company Hektor , which operates from the Falkland Islands, took over the transport to the Antarctic free of charge.

Wilkins put together a five-man expedition team from the pilots Ben Eielson and Joe Crosson (1903-1949), the mechanic Orval Porter (1896-1976) and the radio operator Viggo Holt (1906-1973). On September 22nd, the men left Hoboken aboard the Southern Cross . They were picked up on October 24th in Montevideo by the factory ship Hektoria . Wilkins had bought two Lockheed Vega, the Los Angeles and the San Francisco , which he had shipped to Deception Island , from where he would explore the Antarctic Peninsula as fuel and weather permit. His vision was still a flight across the continent to the Ross Sea . The ice conditions were unfavorable for this company, the ice cover was unusually thin for the time of year, so that the aircraft had to take off from a short runway on the beach and could not be fully loaded and refueled. That limited its range. On November 16, Eielson started as a pilot and Wilkins as navigator of the Los Angeles for the world's first powered flight in Antarctica, mainly to find better terrain for a runway. The most important flight took place on December 20th. Wilkins and Eielson flew the San Francisco along the Gerlache Strait, crossed the high mountains of the Antarctic Peninsula, and photographed and mapped 1,600 miles of unknown land. At 71 ° 20 ′ S and 64 ° 15 ′ W they turned around with the tank half empty. Wilkins named the land before them Hearst Land, now called Hearst Island . After eleven hours, the plane landed again on Deception Island. In January, the aircraft were dismantled and stored in a shed on Deception Island.

In September 1929, Wilkins returned to his aircraft with two new pilots, Parker Dresser Cramer (1896-1931) and Silas Alward Cheesman (1900-1958). This year it came a little further south, to 73 °. Important discoveries were not made. After all, he determined the island character of Charcot Island .

Hearst was satisfied and gave Wilkins and his young wife a free flight on board the airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin from Lakehurst to Friedrichshafen , the last leg of the so-called triangular trip Friedrichshafen - Seville - Recife - Rio de Janeiro - Recife - Lakehurst - Seville - Friedrichshafen. Wilkins met Hugo Eckener , the director of the Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft and President of the Aeroarctic , with whom he discussed plans for the Zeppelin to travel to the Arctic. In Friedrichshafen Hubert and Suzanne Wilkins were expected by Lincoln Ellsworth, whom they accompanied to his Lenzburg Castle in the Swiss canton of Aargau , where a successful collaboration began.

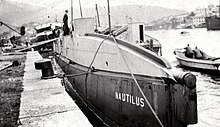

Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Submarine Expedition 1931

During the six-week stay at Lenzburg Castle, the idea of reaching the North Pole by submarine took shape. In contrast to the plane, the submarine promised to be independent of the current weather conditions and to be able to stop at any point of its journey at will. Ellsworth agreed to provide the majority of the financing for $ 70,000. Hearst Enterprises later paid $ 61,000 for exclusive rights to the coverage. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution contributed an additional $ 35,000 , while Wilkins' personal financial contribution was $ 22,000. The pre-published book Under the North Pole raised an additional $ 3,200.

It was possible to charter a military submarine designed by Simon Lake (1866-1945) and built in the USA in 1918 for a symbolic price of one dollar per year through Lake & Danenhower, Inc. The Nautilus , as Wilkins called the boat, based on Jules Verne's novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea , was 53 m long and was able to cover a distance of 200 km under water at a maximum depth of 60 m before it had to surface to his Recharge electric batteries with the diesel engines . The air capacity was sufficient for 20 men for five days. The boat was converted by Lake for a trip in the Arctic Ocean. Among other things, it was equipped with a special ice derrick that was supposed to allow the crew to emerge under a pack ice cover. The captain of the Nautilus was Lakes partner Sloan Danenhower (1885-1967), a son of John Wilson Danenhower (1849-1887), who had accompanied George W. DeLong on the Jeanette expedition.

The program was primarily scientifically motivated. It was planned to let the submarine surface every 80 km in order to make magnetic, meteorological and oceanographic observations. Regular depth plumbing , chemical analyzes of the sea water and investigations of the plankton were planned during the diving trips . Wilkins was able to win the Norwegian oceanographer Harald Ulrik Sverdrup as chief scientist. He was supported by the American oceanographer Floyd Soule (1901–1968) and the German doctor Bernhard Villinger . In order to gain more public attention, Wilkins had agreed with Hugo Eckener that the Nautilus should meet at the North Pole with the airship LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin .

The expedition was accompanied by numerous accidents and accidents. One day before the christening of the ship , at which a grandson Jules Verne was also present, Willard Irving Grimmer (1904–1931) went overboard and drowned when entering New York Harbor. After a series of test drives, the Nautilus left the USA on June 4, 1931. A week later, the starboard engine failed , and a few days later the port one too . The Nautilus radioed SOS on June 14th and was towed to Cobh , Ireland by the battleship USS Wyoming . After a month of repair work in England, which caused the expedition to get out of schedule - Eckener could not wait and the Graf Zeppelin's Arctic flight without heading for the North Pole was successfully completed at the end of July - the scientists came on board in Bergen on August 5th. On August 19, the Nautilus reached the ice edge north of Svalbard. When the first attempt at diving was to be made on August 22nd, it turned out that the down elevator was missing. The scientific program was started anyway. After Danenhower found a way to dive shorter distances, some diving trips were made under the pack ice. On September 7th, Wilkins broke off the expedition. The submarine reached Bergen on September 20, 1931 so badly damaged that it had to be abandoned and was sunk on November 30.

The expedition had not achieved its goals. However, it was shown that a comprehensive scientific program can be carried out on board a submarine even under the restrictive conditions and that submarines are able to operate under the Arctic ice cap .

The Ellsworth Expeditions

Wilkins was hoping to make a second expedition on a better submarine, but his reputation had suffered and he could not find the necessary funds.

Lincoln Ellsworth was planning an Antarctic expedition with the goal of the first trans-Antarctic flight, i.e. the one with which Wilkins had failed from 1928 to 1930. It was still unclear whether there is a connection between the Weddell and Ross Seas that separates West Antarctica from East Antarctica . It was also open whether the mountain range from Victorialand via the Queen Maud Mountains to the Antarctic Peninsula would continue. Ellsworth, who had lost his former partner Amundsen, saw in Wilkins the ideal man to assist him in his plans. Wilkins was the organizer and deputy of Ellsworth on a total of four expeditions between 1933 and 1939.

Wilkins sailed to Norway in 1933 and bought the motor ship Fanefjord , which Ellsworth renamed Wyatt Earp , and hired the crew of experienced whalers. The two pilots of the expedition, Bernt Balchen , Byrd's pilot on his flight to the South Pole , and Magnus Olsen (* 1913) were Norwegians. The expedition's aircraft, the Polar Star , was a Northrop Gamma class prototype with a range of over 11,000 kilometers. In the winter of 1933 Balchen tested the aircraft in the United States and found it suitable on March 6th. On December 5, 1933, the Wyatt Earp set sail in Dunedin , New Zealand and reached the Bay of Whales in the Ross Sea after 33 days . On January 11, Ellsworth and Balchen undertook a first successful test flight along the route that Amundsen had followed in 1911 on the way to the South Pole. The night before the start to cross the continent, however, there was a huge break in the ice edge, which damaged the aircraft so badly that the plan for this season had to be abandoned.

Ellsworth returned to Antarctica in 1934 but had modified his plans. In order to avoid a circular route, he now wanted to fly the route from the Antarctic Peninsula to the Bay of Whales and be picked up from his ship there. The Wyatt Earp reached Deception Island on October 14, where Wilkins had flown in 1928. However, damage to the aircraft and bad weather meant that the take-off was repeatedly postponed. After a short test flight from Snow Hill Island , Balchen refused to take the risky flight at all.

In the fall of 1935, the Wyatt Earp returned with Ellsworth, Wilkins and the new pilot Herbert Hollick-Kenyon (1897-1975). The ship called at Dundee Island , where the Polar Star started after two unsuccessful attempts on November 23, 1935 for the first crossing of the Antarctic mainland. Ellsworth discovered two as yet unknown mountain ranges, which he named Eternity Range and Sentinel Range . Navigation was difficult, the radio soon failed, and after several stopovers they were close to their destination when the fuel ran out on December 5th. On December 15, Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon reached Byrd's abandoned camp in Little America on the Bay of Whales. Since there had been no radio contact since November 24, rescue programs had started. The Wyatt Earp took over a plane hastily brought in from the United States in Chile. The British Discovery II left Melbourne on December 24th with two aircraft on board . On January 16, 1936, she reached the Bay of Whales. From the plane, Hollick-Kenyon was spotted on the ice. Three days later, Wilkins was there with the Wyatt Earp . On January 29, the Polar Star was refueled and flown to the ship. Ellsworth donated it to the Smithsonian Institution in April .

1938–1939 Wilkins organized a fourth expedition to Antarctica for Ellsworth. Due to secret instructions from the US government, Ellsworth changed the destination of the expedition from Enderbyland to Princess Elizabeth Land at short notice . Immediately before the first flight, Ellsworth Wilkins announced that he had a mandate to take possession of all land up to 150 miles from his flight route for the United States. This threw Wilkins into a dilemma, as this territory was already considered to be owned by his native Australia. Using the pretext of taking rock samples, Wilkins visited some islands off the coast and hoisted the Australian flag. He then landed on the mainland near the Vestfold Mountains and repeated the ceremony. Ellsworth flew with his pilot James Harold Lymburner (1904-1990) on the 79th east longitude in the hinterland to 72 ° south latitude and threw prepared copper cylinders from to secure the US claim. He named the newly discovered area American Highland .

Rescue expedition for Levanewski

In 1937, the Soviet Union explored the possibility of a fixed route to the United States via the Pole. In early summer, two Tupolev ANT-25s with pilots Valeri Tschkalow and Michail Gromow had already reached the American continent from Moscow when Sigismund Levanewski took off from Moscow on August 12th. Under difficult meteorological conditions, the four-engine DB-A , the prototype of a long-range bomber , flew over the geographic North Pole with its six-person crew on August 13th. After one of the motors failed, the radio link to the North Pole 1 ice drift station was soon lost.

On August 16, the Soviet embassy in Washington, DC turned to Wilkins with a request to lead a rescue expedition. Just two days later he was on his way to Alaska with a Catalina flying boat . By March 1938, he flew 65,000 km over largely unexplored areas of the Arctic. The scope of the rescue operation was therefore quite comparable to Wilkins' earlier ventures. The fate of the Soviet aviators was never revealed.

During his stay in the Arctic, Wilkins conducted telepathic experiments with the New York parapsychologist Harold Sherman (1898–1987). At precisely defined times, Wilkins tried to transmit "thought impulses" to Sherman, several thousand kilometers away, who - like Wilkins - wrote them down and sent them to Gardner Murphy , the leading parapsychologist at Columbia University . The relative agreement of the records led both of them to believe that they had provided evidence of the possibility of direct thought transmission between two people. She published the results in her book Thoughts Through Space in 1942 . A Remarkable Adventure in the Realm of Mind .

Late years

Wilkins' hopes to conduct a second Arctic expedition with an improved submarine were finally dashed with the outbreak of World War II . Wilkins, who had now settled on a farm in Pennsylvania , offered to help the United States. On an intelligence mission, he traveled through Southeast Asia and the Middle East . From 1942 he advised the US Army on equipment and provisions in areas with extreme climates. He also worked for the American Weather Bureau and the Arctic Institute of North America . After the war he worked for the Quartermaster Research and Development Center of the US Army until his sudden death .

On November 30, 1958, Hubert Wilkins died of a heart attack in a hotel in Framingham, Massachusetts . The United States Navy honored him by moving his ashes to the North Pole aboard the USS Skate . On March 17, 1959, the nuclear submarine broke through the ice, just as Wilkins had planned the Nautilus , and scattered the ashes during a solemn ceremony.

Honors

Hubert Wilkins has received many awards for his achievements. King George V of Great Britain and Northern Ireland raised him to the personal nobility as a Knight Bachelor after his Transarctic flight in 1928 .

Wilkins received the following orders and medals, among others, which are now archived with the majority of his letters and research results in the "Byrd Polar Research Center" at Ohio State University :

- Military Cross , 1918 and 1919

- Patron's Gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, 1928

- Samuel Finley Breese Morse medal from the American Geographical Society, 1928

- Carl Ritter Medal of the Society for Geography in Berlin, 1928

- Elisha Kent Kane medal from the Geographical Society of Philadelphia, 1931

- Mecidiye Order

The University of Alaska awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1955 .

Hubert Wilkins is represented with a bronze plaque on the Jubilee 150 Walkway in Adelaide, which commemorates personalities who have made outstanding contributions to South Australia.

In addition, a number of geographical objects were named after him. They include:

- The Wilkins Bay ( 73 ° 37 ' N , 124 ° 10' W ) of the island-Banks,

- the Wilkins Strait ( 78 ° 10 ′ N , 111 ° 0 ′ W ) in the Canadian Arctic,

- Wilkinsbukta Bay ( 78 ° 13 ′ N , 13 ° 8 ′ E ) on the island of Spitsbergen,

- the chapter Wilkins ( 67 ° 15 ' S , 59 ° 20' O ) of the island Foldøya in Antarctica,

- the Wilkins coast ( 69 ° 30 ′ S , 63 ° 0 ′ W ) of the Antarctic Peninsula,

- the Wilkins Ice Shelf ( 70 ° 25 ′ S , 72 ° 30 ′ E ) in Antarctica,

- the Wilkins ice front ( 70 ° 25 ′ S , 74 ° 30 ′ E ) in Antarctica,

- the Wilkins Sound ( 70 ° 30 ' S , 73 ° 30' O ) in Antarctica,

- the Wilkins Mountains ( 75 ° 32 ′ S , 66 ° 30 ′ W ) in Antarctica,

- the Wilkins Nunatak ( 75 ° 39 ′ S , 139 ° 55 ′ W ) in Antarctica.

An airplane runway named after Wilkins ( 66 ° 41 ′ S , 111 ° 32 ′ E ) has existed with the Wilkins Runway in the Australian part of Antarctica since 2007 . It is the only runway in the ice that can also be approached by civil and scheduled aircraft.

Works

Fonts

- Flying the Arctic , 1928

- Undiscovered Australia , 1928

- Under The North Pole , 1931 (with Vilhjálmur Stefánsson, Simon Lake, Sloan Danenhower, Harald Ulrik Sverdrup and John Wilkins )

- Thoughts Through Space , 1942 (with Harold M. Sherman)

Illustrated book

- Australian was photographs. A pictorial record from November, 1917 to the end of the war , 1919

Movies

- New Worlds for Old , 35mm silent film, 1923

literature

- Lowell Thomas: Sir Hubert Wilkins. His World of Adventure , McGraw-Hill, 1961 (English)

- Simon Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins Australia's Unknown Hero , Arcade Publishing, New York 2006. ISBN 1-55970-825-5 (English, limited preview in Google Book Search , English)

- Stuart E. Jenness: The Making of an Explorer. George Hubert Wilkins and the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913–1916 , McGill-Queen's University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-7735-2798-2 ( limited preview in Google Book Search , English)

- Jeff Maynard: Wings of Ice. The Air Race to the Poles . Random House Australia, 2010. ISBN 978-1-74166-934-3 (English)

Movie

- With the submarine in the Arctic? Sir Hubert's journey to the North Pole. Documentary film, Germany, 2011, 52 min., Directors: Hans Fricke, Sebastian Fricke, production: FrickeFilmproduktion, NDR , arte , first broadcast: October 8, 2011, film information from ARD .

Web links

- Literature by and about Hubert Wilkins in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Hubert Wilkins in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Robert Arthur Swan: Wilkins, Sir George Hubert (1888-1958) . In: Douglas Pike (Ed.): Australian Dictionary of Biography . Melbourne University Press, Carlton (Victoria) 1966–2012 (English).

- Biography , sirhubert.com (engl.)

- Description of his expeditions (Engl.)

- Aboriginal photos taken by Hubert Wilkins on the homepage of the Natural History Museum, London

Individual evidence

- ^ Under the North Pole , Ohio State University Library Digital Exhibition (English)

- ^ SA Pioneers 1836: Family of Wilkins, Henry ( Memento from April 12, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 8

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 2

- ↑ a b c Jenness: Making of an Explorer , 2006, p. 4.

- ^ RA Swan: Wilkins, Sir George Hubert (1888–1958) , Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Center of Biography, Australian National University (accessed February 4, 2013).

- ^ John Stewart: Antarctica - An Encyclopedia . Vol. 2, McFarland & Co., Jefferson and London 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6 , p. 1705 (English)

- ↑ Philip Gibbs, Bernard Grant: The Balkan War. Adventures of war with cross and crescent , Small, Maynard & Co., Boston 1913

- ^ William Laird McKinlay: Karluk. The story of an arctic expedition . Lamuv, Bornheim 1987, ISBN 3-88977-117-3 , p. 63

- ^ William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia , ABC-CLIO, Vol. 2, 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , pp. 631-633 (English)

- ^ David Gray, Sally Gray: Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913-1918 . In: Mark Nuttall (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Arctic , Volume 1 (A – F), Routledge, New York and London 2005. ISBN 1-57958-437-3 , pp. 308–310 (English)

- ^ Wilkins Bay , entry on canmaps.com (accessed February 3, 2013).

- ^ Wilkins Strait , entry on geographic.org (accessed February 2, 2013).

- ↑ Jenness: The Making of an Explorer. George Hubert Wilkins and the Canadian Arctic Expedition, 1913-1916 , 2006, p. 385 f.

- ^ A b c Ian N. Higginson: Wilkins, Hubert . In: Beau Riffenburgh (ed.): Encyclopedia of the Antarctic , Routledge, New York and London 2007, pp. 1078-1080, ISBN 0-415-97024-5 (English)

- ^ A b c Roderick Eime: In Search of Sir Hubert Wilkins . In: Australian Heritage , June 1, 2010, p. 25

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 58

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 57

- ^ The Flight To Australia . In: Flight , May 22, 1919, p. 671.

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 83 f.

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 89.

- ^ Peter Burness: The 1919 Air Race , Australian War Memorial, accessed January 24, 2013

- ^ Louise Crossley: British Imperial Expedition (1920-1922) . In: Beau Riffenburgh (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Antarctic , Routledge, New York and London 2007, p. 197 f, ISBN 0-415-97024-5 (English)

- ^ William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia . tape 1 . ABC-CLIO, 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , pp. 161 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Accessed February 4, 2013

- ↑ a b c Hubert Wilkins: Bleak geographic features were named from plane speeding above . In: Milwaukee Sentinel , November 23, 1929 ( limited preview on Google News ). Accessed February 4, 2013

- ^ A b c d David L. Harrowfield: The British Imperial Antarctic Expedition 1920-1922: Paradise Harbor, Antarctic Peninsula . In: Polar Record , February 29, 2012, pp. 1–22. doi : 10.1017 / S0032247412000101

- ^ Frank Wild: Shackleton's Last Voyage , Cassell & Co., London 1923, p. 8 . Accessed February 4, 2013

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 105.

- ↑ Bernadette Hince: The Antarctic Dictionary: A Complete Guide to Antarctic English , 2000, p. 383.

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 113 ff.

- ^ Gerhard Maier: African Dinosaurs Unearthed. The Tendaguru Expeditions , Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2003, ISBN 0-253-34214-7 , p. 165 (English)

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 140

- ^ Wilkins: Flying the Arctic , Kessinger Publishing, 1928, p. 17

- ↑ Wilkins: Flying the Arctic , Kessinger Publishing, 1928, p. 17 : “ It is the purpose of the Detroit Arctic Expedition to explore that area of the polar ice pack never before seen by man. "

- ^ Donald B. McMillan: Four years in the White North , Harper & Bros. Publishers, New York and London 1918, pp. Xiii

- ^ William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia . tape 1 . ABC-CLIO, 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , pp. 426 ( limited preview in Google Book search). Retrieved February 25, 2013

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, pp. 142-145

- ^ Wilkins: Flying the Arctic , Kessinger Publishing, 1928, p. 46

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 150

- ↑ a b William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia , ABC-CLIO, Vol. 2, 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , p. 710 (English)

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 156

- ^ Ellsworth Bennett: Flyers Again Beat the Arctic. Continents Brought Hundreds of Miles Nearer Together by Wilkins and Eielson in Polar Flight . In: Popular Science Monthly , July 1928, p. 24

- ↑ Berlin welcomes the polar fliers. 13 planes escort Wilkins and Eielson to Berlin . In: Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung , June 1, 1928 (accessed September 11, 2019)

- ↑ Wilkins reports. The first two honorary members of the Aero-Arctic } . In: Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung , June 2, 1928 (accessed September 11, 2019)

- ↑ List of Gold Medal Winners from the Royal Geographic Society , accessed June 17, 2018.

- ^ Sir G. Wilkins married to Miss Suzanne Bennett , The Register News-Pictorial , Adelaide, September 2, 1929, p. 4 , National Library of Australia (accessed February 19, 2013).

- ^ The Idea , Digital Exhibition Under the North Pole of the Ohio State University Libraries

- ↑ Submarine. The Autobiography of Simon Lake as told to Herbert Corey (PDF; 12.4 MB), Appleton-Century, New York and London 1938, p. 289

- ^ Submarine , Digital Exhibition Under the North Pole at the Ohio State University Libraries

- ^ A b c H. U. Sverdrup, FM Soule: Scientific Program of the “Nautilus” Expedition, 1931 (PDF; 4.0 MB). In: Papers in Physical Oceanography and Meteorology 2 (1), 1933, pp. 3–75 (English)

- ↑ Erich Rackwitz: Travel and Adventure in the Zeppelin . New Life Publishing House, Berlin 1955, p. 202

- ↑ http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/s/c/u/John-C-Scullin/GENE2-0004.html , accessed on March 21, 2013

- ^ JJ Ahern: Low Road to the Pole: History of the Expedition on the American Philosophical Society website , accessed March 21, 2013

- ^ Arctic Dive , Digital Exhibition Under the North Pole of the Ohio State University Libraries (English)

- ^ Afterwards , Digital Exhibition Under the North Pole of the Ohio State University Libraries (English)

- ^ A b John Stewart: Antarctica - An Encyclopedia. Volume 1. McFarland & Co., Jefferson and London 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6 , p. 492

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration. 2006, p. 259

- ^ Raimund E. Goerler: Ellsworth, Lincoln. In: Beau Riffenburgh (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Antarctic. Routledge, New York and London 2007, pp. 375–377, ISBN 0-415-97024-5 (English)

- ^ William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia. Volume 2: ABC-CLIO. 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , p. 213 (English)

- ^ William James Mills: Exploring Polar Frontiers - A Historical Encyclopedia. Volume 2: ABC-CLIO. 2003, ISBN 1-57607-422-6 , p. 215 (English)

- ^ A b John Stewart: Antarctica - An Encyclopedia. Volume 1. McFarland & Co., Jefferson and London 2011, ISBN 978-0-7864-3590-6 , p. 493

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration. 2006, p. 271 f

- ^ Iwan Papanin: Drift on the ice floe , Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1970, p. 82 ff.

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 265

- ↑ Allan Kardec: You, me and the others. 13 lessons on parapsychology , Otto Reichl, Remagen 1970, p. 53 f

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, p. 267 ff

- ↑ a b Sudden Death of Explorer , Advertiser, Adelaide, December 3, 1958, accessed April 3, 2013

- ↑ Nasht: The Last Explorer. Hubert Wilkins, Hero of the Great Age of Polar Exploration , 2006, pp. 306-308

- ↑ Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers , Byrd Polar Research Center, accessed May 15, 2017

- ^ Photo of the doctoral certificate , Byrd Polar Research Center, accessed April 5, 2013

- ^ Wilkins Bay , entry on canmaps.com (accessed February 3, 2013).

- ^ Wilkins Strait , entry on geographic.org (accessed February 2, 2013).

- ^ Wilkinsbukta . In: The Place Names of Svalbard (first edition 1942). Norsk Polarinstitutt , Oslo 2001, ISBN 82-90307-82-9 (English, Norwegian).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Geographical objects named after Wilkins on geonames.com

- ↑ Antje Blinda: Aviation premiere: first passenger jet lands in Antarctica. In: Spiegel Online , December 12, 2007

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wilkins, Hubert |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Wilkins, George Hubert (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Australian polar explorer, photographer, cameraman, pilot, geographer and reporter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 31, 1888 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Netfield , Mount Bryan East near Hallett , South Australia |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 30, 1958 |

| Place of death | Framingham , Massachusetts |