Inclusive pedagogy

Inclusive pedagogy is a pedagogical approach whose essential principle is the appreciation and recognition of diversity (= difference) in education and upbringing . The term is derived from the Latin verb includere (to include, to include ); the German “ special education ” is partly seen as the opposite pole to inclusive education. This view is justifiable insofar as human rights activists like Valentin Aichele refuse to use the category “special educational needs”: “All children are in need of support and have a right to it [= to“ special support ”]."

There is a radical and a moderate group among those who support inclusive schooling. Radical advocates of inclusion come to the demand: "All pupils attend general school and are taught by teachers". Ilka Benner justifies this with the words: “In inclusion, it is important to establish an education system that is inclusive for all students. Such an education system ensures that all children and adolescents receive schooling together and grants each individual the best possible support and utilization of their potential. In order to achieve this, the educational systems must be redesigned, which includes both the abolition of the special school system and a reform of the mainstream school system in terms of structure, curricula , teaching approaches and learning strategies ”.

Moderate advocates of inclusion are satisfied when 80 to 90 percent of students with special educational needs attend mainstream schools. Hans Wocken takes the position that although compulsory special education is inadmissible, the existence of special schools is not. Michael Wrase, Professor of Public Law at the Hildesheim University Foundation and at the Berlin Science Center for Social Research (WZB), also says: “Assignment to a special needs school against the will of the child or his parents basically constitutes discrimination within the meaning of Art. 5 Para. 2 in conjunction with Art. 24 CRPD . It can at most under certain circumstances be justified - as a last resort, so to speak - but then requires an extremely careful and precise examination and justification. ”On the question of whether a“ remainder of special support facilities for around 10 to 20 percent of all children with disabilities can still be legitimized ”, according to Wrase, one could discuss openly.

Opponents of inclusion argue that inclusion is not a method , but an ideology that is not aimed at the well-being and successful learning development of all school children, but rather a society-changing policy. They consider it advantageous to form homogeneous learning groups and to respect the will of the parents , who are anyway mostly skeptical of inclusion. Representatives of this traditional educational direction are sometimes defamed as followers of homodoxy . Some supporters of the idea of inclusion accuse them of excluding , stigmatizing and selecting people .

With slogans such as It is normal to be different , diversity makes one strong , every child is special or everyone is disabled, the representatives of inclusive education want to point out that the method of inclusive offered by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities education (English, official German translation according to Art. 24 (1) of the UN Convention: Integrative Education ) is part of a striving for inclusion, which must encompass all areas of society.

definition

In Handlexikon of special education (2006) Andreas Hinz defines the approach of inclusion as

“General educational approach that argues on the basis of civil rights, opposes any social marginalization and thus wants to see all people guaranteed the same full right to individual development and social participation, regardless of their personal support needs. For the educational sector, this means unrestricted access and unconditional membership in general kindergartens and schools in the social environment, which are faced with the task of meeting the individual needs of everyone - thus, according to the understanding of inclusion, everyone becomes a natural member of the community accepted."

The Federal Employment Agency makes the term understandable in another way:

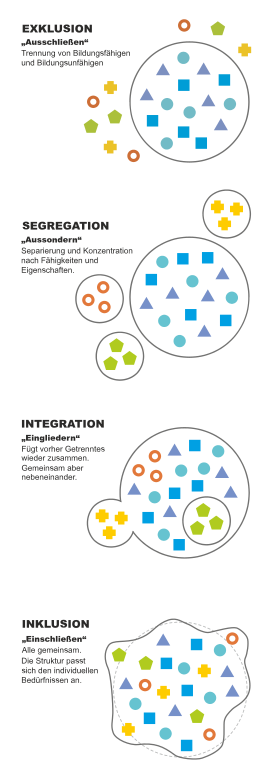

"[...] Inclusion ends the interplay of exclusion (= exclude) and integration (= bring in again)."

A textbook by the educational scientist Gottfried Biewer defines inclusive pedagogy as "theories of education, upbringing and development that reject labeling and classifications, start with the rights of vulnerable and marginalized people, advocate their participation in all areas of life and a structural change in the regular Institutions aim to meet the diversity of requirements and needs of all users ”. For the representatives of the inclusion concept, there are no groups of students to be separated and segregated , but rather a group of students whose members have different needs. Many needs are shared by the majority and form the common upbringing and educational needs . According to this view, all students also have individual needs, including those for whose satisfaction the provision of special means and methods may be necessary or useful. The representatives of inclusive education consider attending a local general school and taking into account the individual needs of all as human rights and demand that the school should be able to cope with the needs of its students as a whole. In their opinion, a school should be designed for everyone , from which no child will be excluded because it cannot meet the respective requirements.

Differentiation from integration pedagogy

Similarities

Integration pedagogy and inclusion pedagogy complain that in many countries, even in those without a structured school system , pupils with disabilities are excluded from attending general schools. This is all the more happening in countries like Germany, in which, in a structured school system from secondary level onwards, even pupils without disabilities are assigned to different schools. Only a common school for all children and adolescents can counteract these conditions. Both supporters of integration and those of inclusion stand up for the right of all pupils to be taught together regardless of their abilities or disabilities as well as their ethnic, cultural or social origin. Most supporters of inclusive education also take the view that there is an obligation for pupils and their parents not to withdraw or want to withdraw from this commonality, not even with reference to a different idea of the best interests of the child .

differences

“In contrast to integration, the model of inclusion aims at all people and thus sets the goal of making school a stimulating and pleasant, supportive and challenging place of learning for all students (and also for all teachers). The whole school wins. "

Despite the similarities and although inclusive education can be understood as a further development of integrative education , integration and inclusion education show conceptual and conceptual differences:

For the educational scientist Susanne Abram

“The concept of integration differs from the concept of inclusion in that the integration of people is still about perceiving differences and first reuniting what is separated. In relation to school, however, inclusion is understood as a concept that assumes that all students with their diversity of skills and levels actively participate in the classroom. All students experience and perceive a community in which each individual has his / her safe place and thus participation in the class is possible for all students. "

The educational scientist and psychologist Walter Krög also points out the difference between the two concepts and emphasizes that inclusion goes beyond:

“If integration means the incorporation of previously segregated people, inclusion wants to recognize the difference in the common, i. i.e. taking into account the individuality and needs of all people. In this concept, people are no longer divided into groups (e.g. gifted, handicapped, foreign-language ...). While the term integration is accompanied by a previous social exclusion, inclusion means co-determination and co-creation for all people without exception. Inclusion includes the vision of a society in which all members can of course participate in all areas and the needs of all members are also taken into account as a matter of course. Inclusion means assuming that everyone is different and that everyone is allowed to help shape and determine. It shouldn't be about adapting certain groups to society. "

A primary school teacher from Bremen explains what is meant by real inclusion: “I cannot […] state how many pupils with special educational needs I have in my mixed-year class with 23 children. We do without such a diagnosis until the middle of the third grade and only provide it for secondary schools. I have to deal with each child differently anyway. ”The teacher points out that“ decategorization ”is an essential feature of inclusive education: A schoolchild who needs help is helped“ quickly and unbureaucratically ”, regardless of what justifies his need for help is. Thinking in terms of “competitiveness” (key question: “Can the child 'keep up' with the other children in the class (with the same goals) or does it have to be taught differently 'out of competition'?") Does not take place.

Graumann points out that while it is important and correct not to label too quickly, and that it is good if visitors to a school cannot immediately see which children have special educational needs. “However, the responsible teachers have to diagnose precisely in order to know what support measures need to be taken. The difficulties a child has do not go away by not being given a label, and vice versa, determining what special needs a child has does not necessarily lead to stigmatization. "

Textor points out that the frequently made distinction between inclusion and integration, according to which the concept of inclusion starts from an inherently heterogeneous group, while the concept of integration means integrating a minority group into a majority group, neglects the theory of integration pedagogy. For example, the concept of integration in Feuser (1989) corresponds very precisely to what is understood today by “inclusion”.

The North Rhine-Westphalian Ministry of Education rates the distinction between integration and inclusion as not being practical. A goal-different teaching presupposes that the pupils who receive a corresponding “other” lesson are removed from the performance competition beforehand, which presupposes that they have been certified as having a “need for special educational support”, that is to say that they have been “labeled” . In the section “Limits to de-labeling” of the program “On the way to an inclusive school in North Rhine-Westphalia” it says in 2015 that “a formal assessment procedure in elementary school in the area of the priority areas of learning, emotional and social development and language (together: Learning and developmental disorders) is no longer necessary to determine the number of teaching positions required for special needs teachers ”, but that“ [z] at the end of primary school [...] for the vast majority of children who received special needs education, too a formal determination procedure had taken place ". Such a procedure is only dispensed with in the case of "children who were taught in primary schools with the same target in the priority areas of emotional and social development and language."

Ultimately, this means that teachers without additional skills or with only a few advanced training courses are confronted and left alone with children for whose education they themselves are not trained.

In Switzerland , even after the country joined the UN Disability Rights Convention with effect from May 15, 2014, the term “integration” has been used consistently in the context of schooling disadvantaged pupils in mainstream schools. Mireille Guggenbühler criticizes this usage: "Hardly anyone noticed that Switzerland too signed the UN Convention in May of this year and thus committed itself to creating an inclusive education system."

Concept history

Although inclusion education was only established in the early 1990s, the concept of inclusion played a role even earlier. Most of the early uses were about the inclusion of certain teaching content in the curricula and the inclusion of parents in school processes. In addition, the term is class inclusion (English, German class inclusion ; see mathematically : inclusion mapping ) that the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget had introduced and which is about whether there are psychological differences between children, which is easy for you to read and such, who find reading difficult.

From the end of the 1960s, the term inclusion got conceptual meaning in connection with the development of the so-called common school .

development

“The different special education disciplines and with them the special school types were constituted from various philosophical, socio-political and philanthropic impulses at the end of the 18th and in the course of the 19th century, this constitutional process by Möckel (1988, 25) in his ´History of Curative Education´ described as a process of 'public recognition of disabled children'. This recognition also means that pedagogical concepts have been developed and that school education for these students was considered conceivable for the first time (Schwager 1993). An exception is the auxiliary school or the later school for people with learning disabilities because it was about pupils who were already pupils in the general school. In contrast to the other special education subjects or to the other special schools, the school-based educational offer was not extended to previously untrained groups of students, but a differentiation of the school system and thus of the student body took place, which was originally founded on an educational basis. "

19th and 20th centuries

In the middle of the 19th century, the British doctor John Langdon Down founded funding institutions for people affected by trisomy 21 - later the syndrome was named after him - and pointed out their ability to learn.

In 1880, the first auxiliary school for children with learning disabilities was set up in Germany ; this system was initially only available to children of higher social classes .

“On the basis of an initiative by the 'Self-Help Association of the Physically Disabled', which was founded in 1919, the State Youth Welfare Office in Berlin carried out a survey in September 1929 using questionnaires at all primary and auxiliary schools in Berlin. It was found that out of 830 handicapped children, 768 attended elementary schools and the remainder attended special schools. ... that the educational level of the integrated children and adolescents was low due to a wide variety of problems, but even lower in the special schools: 'From the questionnaire it was found that the children who had been released from the children's sanatorium in Buch [home special school, VS] were by several Stand behind their peers in school knowledge for years. [...] '"

Lübeck was the first German state to introduce compulsory schooling for the deaf and mute and at the same time set up an independent school for the less able; when he took over the privately run “deaf and dumb school” there at Easter 1888. This was due to the pedagogue Heinrich Strakerjahn , to whom children of all social classes had been left, namely "deaf and dumb", "mentally weak" and "linguistically retarded". As a result, Strakerjahn had successfully sought the establishment of a special school for the less gifted .

After the Second World War , there was no reorganization of the school system in the Federal Republic of Germany, as in the Scandinavian countries , but the reconstruction was restorative : the general schools and special schools that still existed continued their work, although in the Third Reich attending an auxiliary school could have been a death sentence .

Until 1960, the expansion of general and vocational schools was the focus of educational policy activities and pronouncements. There was no comprehensive supply of special schools, and many a child with a disability “was taken for granted in the general school and taught with non-disabled children. In connection with the relief of the general school for disabled children, negative school selection processes began. "

1960 advocated Standing Conference of Ministers of Education in its opinion on the order of special education , the separation of children and youth with disabilities as rehabilitation - and integration support: From now on, carried the massive expansion of special schools also to relieve the mainstream schools. Between 1960 and 1973 the number of special schools doubled, the number of pupils attending them almost tripled, and the number of those teaching in special schools quadrupled.

After the special education system was deliberately excluded from the “Structure Plan for Education” of 1970, the education commission of the German Education Council (DB) appointed a special education committee in 1970 ; thereupon, in the 1970s, the "joint teaching" of disabled and non-disabled children and young people in Germany as a result of a resolution of the Conference of Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of 1972 ( Recommendations on the regulation of special schools ) and a recommendation of the German Education Council from 1973 ( Recommendations of the Education Commission: Zur pedagogischen Promotion of disabled children and adolescents at risk of disability ) tested in school trials. In the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia , such experiments were carried out in two phases: 1981 to 1989 and from 1989 to 1993 (see also: School experiment for joint teaching in lower secondary level ). Here, children of all types of disability were taught together with so-called “non-disabled” children. The trials were assessed positively by all those involved.

The integrative Montessori educational institutions of the Munich Campaign Sunshine and the Kinderhaus Friedenau e. V. are assigned a key function for the spread of common education in the elementary sector and in school. With the practice of the Munich Integrative Montessori Primary School (1970) and the Berlin Fläming Primary School , which established the first integration class at a state school in Germany in 1976, the demand in educational policy recommendations up to now “as much integration as possible and so little segregation as necessary "is replaced by the" equal right to attend general school "and the premise of integration is indivisible :

"The original contribution of the integration projects in the history of pedagogy is that they have proven that it is possible to teach all students together in the whole range of human diversity, from the severely disabled to the gifted."

"By the mid-1980s, 19 integration schools nationwide, in which children with various disabilities are taught together with children without disabilities, ... can be named."

On November 15, 1994, a new sentence in Article 3 of the German Basic Law came into force:

"Nobody may be disadvantaged because of his disability."

This manifested the change in perspective from viewing “disabled people” as “objects of care ” to their perception as independently acting and individually treated subjects. At the same time, the conclusion can be drawn from the sentence that a preference for people who have been officially certified as having a disability in the form of “ compensation for disadvantages ” should not be assessed as unconstitutional “discrimination against non-disabled persons”.

In 1997 the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the duty of the state to provide certain financial or material benefits was subject to the “reservation of the possible in the sense of what the individual can reasonably demand of society”, according to the court's established case law; d. This means that no one can force state or local authorities to adopt budget estimates that the bodies authorized to make decisions consider to be too high: "The legislature is [...] not constitutionally prevented, the actual implementation of these forms of integration is dependent on restrictive conditions [...] to make “, ruled the Federal Constitutional Court in October 1997, when it had to evaluate the forced attendance of a special school by a physically disabled girl and her exclusion from a joint schooling with non-disabled children; because: "The referral of a disabled pupil to a special school does not in itself constitute a prohibited disadvantage". According to Michael Wrase, the court will no longer be able to defend this position after Germany signed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, even if the court had not yet distanced itself from its judgment pronounced in 1997.

Salamanca Declaration

The UNESCO conference Education for Special Needs: Access and Quality took place in Salamanca ( Spain ) from June 7-10, 1994 . Its main result was the Salamanca Declaration with the mention of inclusion. The declaration became the most important goal of international education policy and subsequently a first international framework for its implementation.

“The guiding principle underlying this framework is that schools should accept all children regardless of their physical, intellectual, social, emotional, linguistic or other abilities. This should include disabled and gifted children, children from remote or nomadic peoples, from linguistic, cultural or ethnic minorities as well as children from other disadvantaged marginalized groups or areas. "

The term inclusive is used repeatedly in the original English text ; in the German version this is indicated with integrative or similar. The English word participate is translated as participation , but it can just as well mean participation , which is more of an activity .

21st century

UN Disability Rights Convention

In the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities , the signatory states undertake to establish an inclusive education system (English, official German translation in accordance with Art. 24 (1) of the UN Convention: integrative education system ), in which the disabled are not excluded from the general education system on the basis of disability (Art. 24 (2) a of the Convention) and have access to general higher education, vocational training, adult education and lifelong learning without discrimination and on an equal footing with others (Art. 24 (5) of the Convention).

Inclusion , i.e. the joint teaching of students with and without disabilities, is not explicitly required in the UN Convention. In fact, neither the term inclusion nor the word common appear in the official German translation . Although integration and inclusion are two different things, the UN convention is regularly used in public discussion in Germany to justify inclusion.

In January 2016, in a joint statement by the Federal Government and the Länder on a comment by the UN Technical Committee on the implementation of Article 24 of the UN Disability Rights Convention (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities ), a joint statement prepared by the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BMAS) and with the participation of the Standing Conference (KMK) BRK) defends the national special school system.

The “General Comment” published in Geneva at the beginning of September 2016 on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of the UN Committee of Experts on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (“General Comment”), which defines the state's obligations to implement Article 24 of the Convention on Human Rights. emphasizes inclusive education as a human right for all, which also applies to people with disabilities at all levels of the education system. Inclusive education expressly includes the right to non- segregation , non-discrimination and equal opportunities. Inclusive education is the right of the child, parents have to align themselves with the rights of the children in the exercise of their responsibility.

Conclusions of German lawyers

A legal opinion by international lawyer Eibe Riedel came to the conclusion at the beginning of 2010 that children with disabilities may only be prevented from attending a regular school in exceptional cases and grants them the right to attend a general school close to their home.

In the opinion of the German Institute for Human Rights , the signature of the Federal Republic of Germany on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has rendered the possibility of state organs to invoke a "reservation of resources" obsolete: The argument for the implementation of the The inclusion principle does not have enough money available, so it should no longer be used against applicants. Gymnasiums are also obliged to accept children and young people with disabilities.

World Report on Disability

In June 2011, published World Health Organization WHO and the World Bank the first world comprehensive report on disability, World report on disability .

One of his central demands is to embed inclusion, especially in the field of education, in sustainable concepts.

"Education is also the key to the primary labor market, according to the report, which remains largely closed to people with disabilities due to prejudice and ignorance, a lack of service provision and vocational training and further education opportunities."

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the UN in 2015 mention inclusion on several points, e.g. B. under Goal 4, Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning ("Guaranteeing inclusive and high-quality education for all and promoting lifelong learning"), Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable ("Cities including , make it safe, resilient and sustainable ”) or Goal 16: Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies (“ Promote just, peaceful and inclusive societies ”).

Inferences

A study by the Bertelsmann Foundation in September 2009 came to the result that at that time in Germany only 20% of children with special needs attended a joint class. In countries like Italy , Norway or Denmark , on the other hand, there have only been a few special schools for children with special needs for years. Almost 100 percent of children with disabilities or handicaps in these countries go to school together with other children (although not always in the same class). More recent projects in Germany also pursue cross-year as well as inclusive approaches (in the sense of interest groups from and for people with disabilities). Above all, this includes the new form of community school .

In a survey on "Social participation of people with disabilities in Germany" by the Allensbach Institute for Demoskopie on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs in May 2011, 51% of those questioned identified the realization of the common upbringing and education of disabled and non-disabled children and young people in Germany with the assessment less or not at all good .

The admission of children and young people with disabilities in general schools is only gaining acceptance in Germany with great difficulty. B. due to general or cost reservations, insufficient availability of necessary resources, the insistence on different, sometimes parallel operated discriminatory, stigmatizing, segregating and selective school types as well as fears of the loss of importance of special and curative education. From our own point of view, the implementation of inclusive ideas and practices is associated with considerable challenges not only for special needs education but also for general (school) education. Inclusion may also be seen as another model for integrating students with disabilities into joint teaching.

Ideals

The goal pursued by the opponents of inclusion of achieving homogeneity in the classes to be taught is considered by advocates of inclusion as unattainable, as preventing equal opportunities and in educationally inefficient.

Inclusion advocates believe that any student can have difficulty learning at any time (permanently or temporarily) for a variety of reasons. It is the task of the school and the teaching staff to provide the appropriate aids and resources to compensate. In many cases, the intervention of special educators or other specialists in direct work with the so-called normal students or as advice for the teachers for regular school lessons could be useful. But even this assistance for the satisfaction of special needs would have to take place without any sorting out.

Arguments for inclusive teaching

“Inclusive education benefits everyone” is a central motto of the “European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education”. Brigitte Schumann explains apodictically that "[t] the wealth of stimulation that comes from a heterogeneous group [...] cannot be compensated by reducing the size of the learning group and by using specialized teachers" and that the lack of such stimuli is contrary to human rights. Any divergent views of affected parents are irrelevant in view of this, especially since parents have been manipulated by the special school lobby for decades.

The claim that the parents were manipulated by the “special school lobby” requires empirical evidence, which Brigitte Schumann did not provide. Parents of children and adolescents with a disability are their child's advocates and their life plan with their disabled child must be accepted and taken seriously. Special educational institutions such as B. the Lebenshilfe offer children and parents a learning and living space that no regular school can currently offer (all-day care, vacation trips, room furnishing, etc.). Due to the circumstances in which they live, many parents are dependent on their child being reliably cared for outside the home all day, including during the holiday season. Your decision for a special facility must be respected. Attributing such a decision to manipulation by the special school lobby is immoral to these parents.

It is true, however, that the main characteristic of the special school for the learning disabled up until the 1960s was the reduction in educational offers, in which the curricula were "relaxed" and adapted to the allegedly reduced learning and performance of children with a learning disability . The reduction was u. a. This is based on the fact that the life framework of an auxiliary student corresponds to that of an unskilled worker and the learning objectives must therefore be based on the knowledge and skills of this group of people.

However, it is not appropriate to discredit the performance of special schools over the last few decades. Speck points out that overdrawing and emotional mix-ups can create a mass ideology, “which is primarily inspired by outrage and can express itself in demands for massive and defamatory interventions in the existing system. Special facilities for handicapped children are generally stylized as inhuman institutions, so that there is growing public agreement that these should of course be abolished ”. Speck points out that such ideological one-sidedness represents a distortion of reality and leads to devastating consequences if it turns out that, despite efforts to include inclusion, special classes are necessary, because the people cared for there would then be discredited and marginalized even more. The current special needs schools are already feeling the effects of these devastating consequences. The rector of a special needs school with a focus on learning and social and emotional development says: "What we like, I put it a bit angry, is the rest of the rest of the rest ...".

Speck is of the opinion that special schools and special needs schools should make it clear to the outside world through concrete practice and public relations work that they "do not represent an obstacle to an integrative education system and do not see themselves as an end in themselves, but that they are subsidiary , i.e. subordinate institutions for Exceptions to the rule of inclusion, taking on educational responsibility and being able to account for it ".

From the interview with the teacher from Bremen cited above, one would conclude that inclusion can succeed if all children are helped without having previously been certified as having a special need for support (excluding the question of what this procedure affects the state and thus the Taxpayers costs), and if one can largely avoid the pressure to perform in higher age groups, the main source of unhappiness in children, at least in elementary school.

Outsourcing versus (re) integration

While children have (so far) been segregated with considerable effort for their school education in order to achieve supposedly the best possible support, a great deal of effort is then made to reintegrate them into society and the general labor market, albeit with dubious success.

In the analysis of interviews with parents whose children received integrative schooling in the 1990s and who will be in their early to mid-30s in 2018, Graumann finds that it has not been possible to integrate them into the general labor market. The integration / inclusion ends at the latest after the 10th school year in a comprehensive school. It is z. B. reported from a young woman who very successfully attended an integrative elementary school and an integrative comprehensive school up to the 10th grade. Charlotte decided for herself that she would like to go to school in grades 11–13 with a focus on mental development and physical and motor development. “Charlotte could experience herself again, as - yes - I would almost say as the fittest among her classmates. She could do anything, she was immediately the class representative and appeared at school events - she wasn't afraid to speak up beforehand either. That gave her a real boost in terms of her self-confidence, ”says the father. After completing school, Charlotte worked in the workshops for disabled people (WfbM), where she looked after people with severe multiple disabilities. But she also wanted to assert herself in the general labor market. She worked in a public kindergarten for four years, but the stress and workload caused by too few staff became too great. In the meantime, she is again doing assistance in a workshop for disabled people and is happy. This is not an isolated case. The example shows that the general labor market is in no way designed in such a way that the inclusion that began in school is continued.

Education costs

The Bertelsmann Stiftung shows in a study that in Germany by 2090, inadequate educational reforms will result in follow-up costs in the billions. Inclusive support appears pedagogically more effective and efficient :

“In Germany, 400,000 pupils are taught at special needs schools. The federal states spend an additional 2.6 billion euros each year on this. ... at first glance this does not seem particularly sensational: children and young people receive lessons in special schools that are specially tailored to their needs. ... - that sounds like sensible investments. ... that international and national studies prove the opposite, at least for the special needs focus learning: The performance of special needs students therefore develop less favorably the longer they are at special needs school. In Germany only a fraction of pupils with special needs make the jump back to a general school. As a result, at the end of compulsory schooling, 77.2 percent of them did not graduate from secondary school . Children with special needs, who, in contrast, learn and live in joint lessons with children without special needs, make significantly better progress in learning and development. In addition, the children without special needs also benefit from joint lessons by developing higher social skills, while their subject-related school performance does not differ from the performance of the pupils in other classes. … One thing is clear: in an international comparison, Germany is taking a different path with its highly differentiated special school system. ... The results of national and international studies are in clear contradiction to this pedagogical practice. "

A study in Canada found that

“The exclusion of disabled people from the labor market reduces the potential gross domestic product by 7.7% (...). ... The figure shows the average loss of economic output, measured in terms of gross domestic product . The graph shows that an estimated 35.8% of the global decline in economic output due to the exclusion of disabled people affects Europe and Central Asia, followed by North America with 29.1% and East Asia and the Pacific with 15.6%. The other regions of the world each account for less than 10% of the global decline in economic output. "

In June 2018, the Lower Saxony State Audit Office reprimanded the Lower Saxony state government for its efforts to maintain parallel structures with inclusive teaching in mainstream schools and teaching in special schools. This procedure is at the expense of taxpayers as it is expensive and exacerbates the teacher shortage. In particular, it is unnecessarily expensive to change the location of special school teachers in the “mobile service” when their students are distributed across many different schools, as this not only results in relief hours but also reimbursement of travel expenses.

Vocational training

Urs Haeberlin attributes the difficulties of school leavers with a disability or with " learning difficulties " to gain a foothold in the primary labor market to the fact that most of them would have experienced school socialization outside the mainstream school system:

“... Young adults with a special class past usually only have access to professions with a very low level of demand or often remain unemployed. For comparable young adults who, however, have not attended a special class, the career prospects look much better. Even three years after leaving school, around a quarter of the former special class pupils have not found a job. For young adults without a special class past, but with comparable school weakness, this risk is around four times smaller. They even have certain chances of access to training in the middle or higher segment. This is hardly ever the case for former special school students. During the transition to vocational training, they often break off several attempts to start a career. "

The results of the investigation by Haeberlin relate in particular to school leavers with a special focus on learning and not to young people with a special focus on mental development or, depending on the degree of severity, on young people with a special focus on physical and motor development. Interviews with parents of such young people show that it is practically impossible to find a job on the general labor market, even if the young person has attended an inclusive mainstream school. Among many other reasons, this is also due to the fact that, depending on the severity of the disability, people with a handicap in performance and profit-oriented companies usually need continuous assistance, even for the simplest work processes, which the companies cannot (or do not want) to provide.

In the last few years there have been numerous legal regulations for the participation of people with a disability in working life on the primary labor market. Germany has committed itself to interpreting and further developing German law in accordance with the provisions of the UN Disability Rights Convention (UN-CRPD) of 2006 and has thus decided in favor of the concept of inclusion. This means that people with disabilities have the same right to work as non-disabled people. For people with disabilities, work must not be restricted to special labor markets and special work environments, but both the general labor market and the specific workplace must be open, inclusive and accessible. However, this goal has so far not been achieved in Germany, although there are many actions by associations and individuals, people in work processes e.g. B. to incorporate in small businesses. The unemployment rate for people with a disability is twice as high as for people without a disability. Nationwide, only 0.16% of all people employed in workshops for the handicapped manage to enter the first labor market every year. The number of employees in these workshops has even increased since the law was amended. The " Act to Strengthen Participation and Self-Determination of People with Disabilities - Federal Participation Act (BTHG) " is intended to change this. The Social Code (SGB) IX was redesigned and came into force in 2018. However, the innovations in terms of content are limited. The concept of inclusive is now insofar as equal participation no longer has to take place through the adaptation of people with a disability to the environment, but through a barrier-free design of the environment.

Attending an inclusive secondary school also obviously does not necessarily protect against difficulties in getting an apprenticeship position, especially not if the diploma shows e.g. B. the note is: "The schoolgirl was promoted with special needs language in the Realschule sector" - as a mother from North Rhine-Westphalia reported in an interview. However, the " Ordinance on special educational support, home tuition and school for the sick (training regulation for special educational support - AO-SF) " in NRW (2016) provides the following in § 23:

“The pupils with a need for special educational support determined in accordance with § 14 receive certificates with the remark that they receive special educational support. The certificates also state the funding focus and the course of study. At the request of the parents, sentences 1 and 2 do not apply to diplomas if support is aimed at the same goal. "

This means that it is the responsibility of the school management to inform the parents about this regulation and to only write the note on a special focus in the diploma if the parents expressly request this. In the case of the above-mentioned mother from North Rhine-Westphalia, the education about the legal regulation was obviously neglected and the inclusive efforts of this school were thwarted.

Brain development, intelligence

Another argument against (premature) separation and segregation of learning groups is the knowledge that the respective intelligence quotient (IQ) can change in the course of the development of young people.

On the basis of more recent findings about the "social concentration" of the human brain, Gerald Hüther regards social experiences as decisive factors for successful brain development:

"The decisive experiences that lead children and young people to use their brains in a certain way and thus also to structure it, are of a psychosocial nature, that is, relationship experiences."

requirements

Inclusive education advocates demand that no student should be seen as "different". A class is a unit of many different students, each of whom is in need of support in some area. Every student is a special case, and therefore special schools are actually superfluous. The special education should be treated as the "normal" education: both sciences formed a unit. “One school for everyone ” must replace the structured school system across the board; it must encourage everyone individually and consider their interests. The necessary infrastructure must be provided. This should lead to more equal opportunities, equal rights and, above all, to a high standard of education.

School politicians and, above all, financial politicians are urged to make more funds available for inclusion. This should include necessary training for educators. The Salamanca Declaration explicitly attributes special needs schools a role as a valuable resource for the development of inclusive schools and states that there is still a limited need for this specialization. Investments should be geared towards this new or expanded role. The realization of comprehensive inclusion leads to a profound reform of the school system: ideally, it leads to an acceptance of the otherness of impaired people and to the removal of barriers . One possible model that works successfully in many countries is the establishment of so-called resource centers for diversity . These are teams of specially trained pedagogues, psychologists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, curative pedagogues, etc., but also special didactic materials, aids, literature, etc., which are made available in some areas as additional resources for schools to support inclusion should be. The principle is that the experts go to the various (mainstream) schools that all children attend after inclusion has been introduced (a concentration of students in a few schools would be inconsistent with inclusion) with the aim of making the pedagogy master to support the heterogeneity then established .

With such an organization of the curriculum, the students, who are able to do so, have to acquire the material themselves and take more responsibility for their learning success, for which a variety of media are made available to them. The teacher no longer primarily teaches himself, he has to give up some of the responsibility and is more likely to give the student help and is available for advice and planning. This assistance should be adapted to the individual needs of the students. Since the pupils have to learn what is known as self-directed learning as early as possible, the best and most capable educators are preferably employed in pre- school and primary schools in those countries in which inclusive pedagogy has already been implemented . Lessons are becoming more action-oriented and open. Regardless of their personal background, parents who are experienced in differentiation are more satisfied with their child's class and school than parents at whose schools there is no internal differentiation.

With the help of detailed questionnaires, day-care centers and schools, as well as municipalities, can evaluate their status on the path to inclusion and gain a variety of impulses.

How inclusive and thus differentiating teaching can succeed can be read in Olga Graumann's chapter: "On the way to an inclusive everyday school life". Learning and teaching concepts are scrutinized for their importance for inclusive teaching. A film, which is included with the book as a DVD, shows a primary school on the way to inclusion. The film proves that inclusion is possible when the framework conditions are right, when the school management and the entire staff are behind the concept of “shared learning”, when the school can give the children with special educational needs what they need individually and when the parents support the concept of school.

In Germany it is feared that the abolition of the special needs school would give up previous possibilities of promotion without the mainstream school system getting enough financial and time resources to offer disabled pupils an appropriate learning environment. At the same time, this could restrict the right of the disabled or their parents to choose a suitable school for themselves. This danger is indicated in the cornerstones of the monitoring office of the German Institute for Human Rights for the implementation of an inclusive education system: They propose the "conversion of special schools into competence centers to schools without pupils" and, moreover, see the parent's right to vote not in line with the Inclusion imperative.

If politicians allow parents to choose between attending a regular school and a special school through their child “strengthens the special education system”, according to the human rights activists, the right to vote must be ignored in the interests of inclusion. On the other hand, the Association of Special Education (supported also by parents' associations) advocates the retention of special funding offers as additional offers in a school system that continues to be structured.

According to Graumann, after the integration experiences since the late 1980s and the inclusion experiences at the latest since the Salamanca Declaration in 1994, today (2018) it must not be a matter of losing sight of school inclusion as a goal. It is true, however, that the necessary conditions are not currently in place in the German school system. It has emerged that the idea or vision of school inclusion rests on three pillars:

- The pillar of the personnel, structural and material framework conditions (including team teaching of general and special education, small classes, specific rooms and room furnishings).

- The pillar of professionalization and professionalism (including didactic and diagnostic skills, reflection on subjective theories, ability to work in a team).

- The pillar of the individual requirements and the right school selection for the benefit of the child.

All three pillars must be stable and intact - to stay in the picture - if the vision of school inclusion is to bear fruit. However, a roof tilts and falls when the pillars are dilapidated. Interviews with parents, school administrators and teachers lead to the conclusion that none of the three pillars is currently firmly established. It must also be asked whether our society offers a secure basis for the inclusion of people with special requirements and needs. The base also has cracks and is brittle. This shows u. a. in the fact that the inclusion that began in school can generally not be continued in working life.

Requirements for successful inclusive teaching

"In a school that is committed to inclusion, teachers and professionals will attach great importance to seeing each student as a personality."

The implementation of inclusion requires a targeted and deliberate handling of diversity as well as the recognition of heterogeneous student personalities, attaches great importance to the diversity in education and renounces the principle of homogeneity . Therefore, inclusive schools do not require any specific individual methods or concepts for their implementation: rather, inclusion requires a largely flexible, target-differentiated application of different teaching methods and organizational proposals in order to be able to satisfy the needs of all students: “Inclusion is an attitude”.

It is a topic for all types of schools and should not be concentrated or restricted to individual types of school, which may already be burdened or are breaking up, such as “Hauptschule”.

Important questions for a successful implementation of inclusive education are:

- the formulation of precise common goals in teaching staff

- the development of a common understanding of inclusion and the awareness of a common task of the concerned and implementing educators

- creating mutually supportive structures in the sense of teaching group lessons ( " team teaching ")

- creating an atmosphere in which all students feel welcome

- to understand special, individual support as something fundamentally normal in regular lessons

- special attention to social interaction in (and also outside) of class groups.

Graumann points out that it is important and good when teachers have internalized the idea of inclusion as an “attitude”. While being inclusive and motivated to teach in inclusive classes is an important requirement, it is not enough. The prerequisites for success are the corresponding framework conditions: 1. The staffing of a school and a class. In other words, in order to guarantee support that meets the individual needs of the students, needs-specifically trained support teachers must work in the class and be ready for teamwork. 2. The spatial and material requirements must be given, such as group rooms, teaching and learning materials for individual needs, etc. a. m. and 3. very close cooperation between home and school must be guaranteed.

Even if there is no specific inclusive didactic, it is necessary that teachers familiarize themselves with teaching and learning concepts that do justice to the heterogeneity in inclusive classes. The current strong criticism from teachers and parents of the implementation of inclusion shows that it is not as easy as said above.

Training of teachers

In general, adapting teacher training appropriately is seen as critical to achieving positive results. In addition, control by politics and administration instead of a free play of forces on site is considered necessary, as is comprehensive support services; A substantial reorientation is necessary for the best possible promotion of all students. Klemm and Preuss-Lausitz recommend

"If you recommend a systematic review of all ordinances from the point of view of inclusion as part of an implementation strategy 'on the way to inclusion': The currently still different teaching specifications for pupils who learn in the same way and with different objectives should be brought together for joint teaching in such a way that, on the one hand, the general (Minimum) learning objectives and, on the other hand, the individual learning objectives that differ from them. They recommend replacing the undifferentiated, rigid performance evaluation with six digit censors with a competence-oriented evaluation in connection with information about individual learning development. Portfolios should serve as a basis for development discussions and support plans and enable self-assessments. In their view, provisions, grade repetitions and schooling are incompatible with the goal of inclusion. "

Design of classrooms

One possible form of implementation would be, for example, the establishment of a “ math room ”, a “ geography room ”, an “information room ”. In these rooms there can in turn be different areas: a “book corner”, a “computer corner”, a “reading and writing corner” etc. The students can largely plan and determine their stay in the rooms themselves. A questioning-developing frontal lesson , as it has so far been largely customary in German schools, does not apply here.

Application of modern pedagogy

Many methods and concepts of so-called modern pedagogy, such as the organization of a school in mixed-age groups instead of the formation of conventional classes, group work on interdisciplinary topics, or newly designed rooms serve to implement the basic idea of inclusion more than traditional didactic methods. Traditional institutional guidelines such as homogeneous learning groups based on performance are more or less in conflict with the goals of inclusion, the orientation towards possibilities.

No numerical notes

The internal scientific support as well as an external evaluation of inclusion-oriented development processes of a Hessian school trial at four primary schools from 2009 to 2013 ( gifted school ) came to the conclusion that the implementation of inclusive pedagogy cannot be limited to the implementation of school organizational measures and a waiver of numerical grades ( in favor of the introduction of competence grids ) is crucial for the success of inclusive teaching. Incidentally, the traditional form of grading in numbers is an expression of equal treatment of all students in the form of applying the same standards, therefore an expression of a lesson with the same goal and therefore not compatible with lesson with different goals.

Positive thinking

In May 2014 the “Henri” case attracted attention in the German media. The boy with Down syndrome , who, according to his parents' wishes, was originally supposed to go to high school, actually switched to secondary school, where he was taught in a differentiated manner.

After the media hype subsided, “Spiegel Online” sums up: “Henri has Down syndrome, which is why he learns differently, more slowly and some things not at all. But his parents want him to be part of everything, so that he doesn't grow up in a parallel world. […] [Henri's father says]: 'Henri needs a job later.' And for this he should learn to read, write and arithmetic as best he can, not just iron or how to cut fruit. 'At some point we won't be there anymore,' says [father]. 'And then he has to get on with his life. He doesn't learn that in isolation from the outside world. '"

Practice of schooling

The German education system is essentially characterized by the fact that pupils are assigned to different schools after class 4 or class 6. Students are assessed by the teaching staff in primary school . Where the parents will does not matter, they are still different schools of secondary level assigned . In the past, this allocation was made (except in East Germany) to a Hauptschule (formerly also called Volksschule), a Realschule (formerly also called Middle School) and a Gymnasium . In many German states, however, the Hauptschule no longer exists as an independent school form. Where the parents' will is decisive when choosing the type of school, there is indeed the possibility of enrolling one's own child in a school other than the one recommended by the teachers, but there is a risk of a later “downgrading” to the type of school “appropriate to the child's talent” In these cases, however, large, especially since "incorrectly assigned" students are often marked accordingly in class lists. In many places, however, the selection pressure is reduced by the fact that parents can register their children at a comprehensive school where this type of school is available , in which the heterogeneity of the student body has been the norm since it was founded .

The possibility of schooling those pupils who cannot meet the requirements of the elementary school or the secondary school in a special school or special school continues to exist in Germany, especially if this corresponds to the parents' wishes. It should not be given up, even according to the will of most state politicians in government responsibility. In October 2016, the “Inclusion Expert Commission” appointed by the state government of Lower Saxony presented an action plan to the public. a. the target contained: "All pupils attend general mainstream schools and are taught by teachers". However, this regulation was not implemented in corresponding plans by the Lower Saxony Ministry of Social Affairs. In its “Inclusion Action Plan 2017/2018” of the then red-green state government, it said on the one hand: “The inclusive school has been introduced for all types of school”, and the special needs school learning is to be “gradually abolished”. On the other hand, certain point 4.2.11 of the action plan: "According to the [sic!] Parents' will (from 2013) implementation of the inclusive schooling of the pupils or attendance of a corresponding special school." Lower Saxony parents of disabled children should therefore be given the possibility of their To have children taught at a special school. This statement does not contradict the abolition of the school with the special focus on learning, as the authors of the action plan are of the opinion that pupils with pronounced learning disabilities should not be considered "disabled".

After the state elections in Lower Saxony in 2017 , a grand coalition of the SPD and CDU parties was formed. In the coalition agreement it was agreed that the school inclusion should be continued and led to success “in the interests of the individual child's well-being”. The provision of teaching hours to inclusive schools is to be improved. The gifted are also to be given more support. Apart from the special school with a focus on learning, no special school should be abolished. The special schools learning in lower secondary level can be granted grandfathering for a transitional period up to 2028 at the latest at the request of the school authority and according to needs and demands. For the last time, 5th grade pupils can start school in the 2022/2023 school year.

In Baden-Württemberg , from the 2012/2013 school year, 41 so-called starter schools were set up as model community schools with inclusive educational offerings; in 2017 there were already 304 community schools .

Marco Tullner , Education Minister of Saxony-Anhalt , declared in December 2017 the previous practice of inclusion "failed" because it overwhelmed both students and teachers. Therefore, the existing system of special schools must continue to be continued. There are not enough teachers to provide satisfactory inclusive teaching and, given the labor market situation, this situation cannot be remedied in the short term. Apart from that, Tullner takes the view that there are children with special needs who could be better looked after in special schools than in a “normal school”.

Uwe Becker also drew a sobering balance in 2017: “The ditch: special school equals exclusion - regular school equals inclusion is [...] completely wrong and is out of the question with a view to the quality of inclusive regular schooling. At the beginning of September 2015, the Bertelsmann Stiftung published a study on the quality of the inclusive education system in Germany. According to this, about 67 percent of ten thousand children with special needs go to a day-care center on average, only 47 percent attend a regular primary school, whereas only 29.9 percent go to secondary level I. The vast majority, namely almost 90 percent, go to secondary school, a good ten percent to secondary schools or grammar schools, but very few achieve the qualification and even less the path to training (cf. Bertelmann Stiftung, 2015). What is striking is the fact that children and young people in this educational process have to experience in rows that sooner or later they will be kicked out of the system. At the latest with a view to their training, they realize that the system denies access to gainful employment. This is a half-hearted form of inclusion, namely one with delayed and humanly extremely disappointing and demoralizing exclusion effects. Exclusion tendencies, which in the tripartite school system have stigmatizing consequences especially for secondary school pupils, are intensifying again for young people with disabilities. "

“The formal determination of special educational needs (SEN), which links resource allocation to the individual labeling of a disability, is proving to be a central hurdle against an inclusive school system. It 'seduces' teachers into asking as many of their students as possible, who are somehow off track and causing problems, a need for support. "

Systemic resource allocation spares students from labeling that is inconsistent with inclusion, and the incentive to generate additional teaching hours through such (incorrect?) Labeling (many of those labeled as such outside of school would not be viewed as “disabled”) is eliminated. The North Rhine-Westphalian school ministry confirms the negative consequences of sticking to labels in connection with the retention of the special needs school as an institution: “With an increase in the total number of pupils with a formally established need for special educational support and a rather small decrease in the number of pupils at special schools - in some cases even an increase - this means that fewer positions will be available for joint learning at general schools. "

With a systemic allocation of resources, there is the possibility of capping state services “according to the budget” so that schools have to get by with the sums that are allocated to them. However, this puts them in the same situation that mainstream schools have known for a long time, in which students without impairments cannot claim a proportion of the teaching hours for themselves (e.g. when a teacher in a class with 28 students has to give each student 1/28 of their attention).

Objections to an obligation to attend a regular school

Bernd Ahrbeck, professor emeritus from the Institute for Rehabilitation Sciences at the Humboldt University in Berlin, formulates an antithesis to the demand: “All pupils attend general school”: “The limits of inclusion are that there is an unconditional commonality that no one can escape may not be good for all children. Some pupils will continue to be dependent on special educational settings, not least because of their indispensable support needs. ”“ Particularly sensitive children, children who feel easily bullied, or children who need a stable, familiar setting often come in small, manageable settings Groups with closer, more intensive ties get along better, ”says Ahrbeck.

Olga Graumann confirms this statement. The rector of a school with a focus on language, social and emotional development and learning in primary and secondary level I in North Rhine-Westphalia points out in an interview that the remaining special needs schools can hardly put together classes in which children support each other can. The children are all so open to stimulation, so vulnerable and they bring so many burdens from home with them that all the children in a class “go to the ceiling” when z. B. only a pin falls on the floor. The children have such a high need for attention and psychological help due to school phobia, school anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder and the like. a. m., which can no longer be done in the classes. Also children who z. B. were classified as not suitable for school, are assigned to the special needs school. This means that the special needs schools have to solve all the problems mentioned within the school themselves and can hardly be maintained. The Rector describes this as the greatest problem of inclusion. She also reports of children who go back to the special school after being included in the school because they have been "lost" in the mainstream school. i.e., did not feel they belonged. This is particularly due to the deteriorating supply of staff in mainstream schools. More and more special needs students and at the same time fewer and fewer special needs teachers are assigned to mainstream schools. The Rector therefore proposes a general dissolution of the above-mentioned special needs schools, since only then could all resources be put into inclusion. The extent to which there are still limits to school inclusion should be shown, in particular with regard to the priority areas of intellectual development and, depending on the degree of severity, also with regard to motor and physical development.

Renken from the GEW district board in Rotenburg also points out that the maintenance of parallel systems means that "with increasingly less supply of special school teachers, the hours in inclusion (...) will continue to decrease drastically (...) A significantly higher proportion of hours is assigned to special schools, only around 50 to 70 percent of the calculated target (...) flow into inclusion. An extension of the transition period helps to worsen the framework conditions instead of improving them. "

In the inclusive schools it is also criticized that there is too little support or that there is no individual support at all in the secondary schools with regard to the support focus or that there is obviously hardly any internal differentiation, but the support children are taught outside of the classroom. This gives rise to the concern that the sponsored children will not have a chance to improve and develop themselves through learning together. Some parents obviously have the impression that they or the child are blamed in the inclusive mainstream school if it does not “work”. It is complained that teachers in inclusive classes signal to parents that they are doing something wrong or that the child is not trying hard enough.

Olga Graumann qualifies: These statements are countered by the fact that there are numerous examples of successful inclusion. Whether the inclusion succeeds depends on numerous factors: staffing and qualification of the teachers with regard to specific support needs, degree of motivation and integration experience of the teachers, equipment of the school with regard to specific support needs, severity of the disability (e.g. students who have one need limited space), willingness of parents and teachers to work closely together.

Alleged abuse and lack of acceptance of the disability rights convention

In North Rhine-Westphalia, the idea of implementing inclusion has met with resistance: the Association of Teachers in North Rhine-Westphalia found that the right to inclusion in schools, which has been stated in many places, is simply based on a misinterpretation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Disabled. The special education teacher Otto Speck sees the current legislation on inclusion as being too much for teachers, based on misunderstandings and translation errors. Above all, the UN Convention does not require Germany to abolish its special schools. Speck argues that the educational institutions formerly known as “special schools” are a part of the general school system, namely the part that offers specific support to people with disabilities free from forbidden disadvantage. According to the contract, however, such special measures do not count as discriminatory disadvantage, but as permissible positive discrimination against people with disabilities. Above all, an exclusion exists when children with disabilities are denied school education. Preventing that is the main purpose of the convention.

"News4teachers" says: "The reference to the UN Disability Rights Convention [...] ratified by the Bundestag in 2009 is a formal one - and as such is not very suitable to arouse interest or even enthusiasm. Clear words and clear examples would have been required at an early stage in order to make the necessity of inclusion so clear to broad sections of the population that they would possibly have seen beyond initial difficulties. As it is, however, the problems that are now occurring massively in practice appear to the teachers and parents concerned as a seemingly endless strangulation. And what for? The vision is missing. ”With a top-down policy in which decisions by politicians and orders from authorities are not adequately explained, an inclusion policy is doomed to failure.

Ultimately, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is only suitable to help parents who want this to obtain inclusive schooling for their children by legal means, but not to prohibit democratically elected politicians from deciding to maintain a parallel system of special needs schools, when the majority of voters support this policy through their voting behavior. Only voting in the “area of the unvotable”, which is protected from voting, is prohibited. Interventions in children's rights would therefore only be prohibited if it were unequivocally a violation of the child's best interests. The thesis, however, that in any case the visit of a special facility would harm the child's welfare is not scientifically verifiable.

Dissuasive practice

Various press reports report negative experiences of parents in Germany with schooling their disabled children in regular schools. It was only after attending special schools that these children became happy again.

In the coalition negotiations after the state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in 2017 , the CDU and the FDP agreed to stop the closure of special needs schools in North Rhine-Westphalia that had begun by the previous red-green government. 35 special schools that had already been decided to close should therefore remain in place because this decision "caused displeasure among many parents and teachers". Because, according to Armin Laschet : “Inclusion was introduced with a crowbar. Special schools have been closed, but the special and social pedagogues that are needed have not been given to the schools. [...] As long as many mainstream schools still lack special teachers and structural requirements for inclusive teaching, no further special needs school may be closed. "

General skepticism from teachers and parents

According to a study in North Rhine-Westphalia in 2011, around 70% of special school teachers and 80% of mainstream school teachers were very skeptical of teaching together. They argue in particular with the decline in the general level of learning in learning groups that are too heterogeneous and the increasing difficulty of being able to do justice to the individual student in his or her individual learning pace and possible learning progress. This attitude has a lasting impact on the success of inclusion efforts ordered by school authorities.

According to a Forsa study, the proportion of unreserved supporters of the inclusion concept among teachers nationwide rose only slowly until 2017, to 54 percent.

According to a survey by the Kölner Stadtanzeiger in 2017, 72 percent of the 980 readers who voted said: "Everyone suffers from inclusion, the concept has failed."

Graumann puts this statement into perspective: “The fact that inclusion is currently receiving the highest priority in education not only in Germany but also in numerous countries around the world is a success that everyone who has been following this path for decades can be proud of. Never before has it been discussed so extensively and so often in science, in the media and thus in front of a large public, whether and how young people, but also adults with special needs, can be integrated into our society. On the one hand, it is important to show where inclusion is currently in danger of failing. On the other hand, it is just as important to show what we have to do in order not to abandon the path to an inclusive school, but to continue along it and to arrive at an education system in which every child and every young person has a place. "

On the other hand, interviews with parents whose children first attended a special school show their experiences in special schools more positive than in inclusive secondary schools. Particularly with regard to the severity of the handicap, priority is given to the special needs school. " The best thing for children, when they are badly affected, is a special school," says one mother. The advantage of the special school is that “ the children are taken as they are. And they are not forced to change. You look at the children. ” Teachers at special needs schools are described as attentive to the needs of the child and ready to talk.

Missing empirical research

The effects of attending a joint school on individual pupils have been examined, particularly for pupils with special educational needs. The results of the studies show that school performance in particular develops better in inclusion than in special needs schools. Some English-language studies show that although children with severe intellectual disabilities developed better socially in the joint school, the academic success of these children was better in a special school and that pupils with emotional difficulties in the joint school had a higher dropout rate.

Negative effects of attending a joint inclusive school for pupils without disabilities is often cited in the media as a reason against inclusion. So far, empirical studies have not found any performance losses for students without disabilities in inclusive classes.

Another problem is the fact that inclusion is to be introduced on a broad basis without a well-founded examination of the effects. Corresponding scientific studies in the context of accompanied experiments should, however, be a prerequisite for checking the feasibility and possibly adapting or rejecting methods.

The term “exclusion” must be de-demonized, and for a reliable assessment of how much exclusivity can be beneficial for each individual child, the debate must be brought back from the sphere of moralization to the bottom of the empirical, demands Bernd Ahrbeck.

Principle of the individual suitability of the learning location

The claim that only mainstream schools are suitable places to learn for pupils with disabilities of all kinds is not only questioned in Germany. So has z. For example, in the USA the concept was enforced that every child should be educated at the most suitable learning location and that this could also be a special school or class. According to American studies, deaf students in particular complained that they would not always have good experiences at a joint school. The inclusive education of deaf and sometimes hard-of-hearing children can be very complex, as they rely on visual communication via sign language and, due to delayed language development, may have educational deficits and need special educational help. If a deaf child receives individual schooling in a class, he or she needs at least two sign languages - an interpreter and a second teacher who is also competent in sign language and can compensate for the lack of knowledge with special needs education. It would be more economical to school several deaf children in one class at the same time.

Similarly, it is argued in connection with the group of children with speech development delay: “If you do not recognize and treat this in time, neurobiological 'windows of opportunity' close and the disorders persist. Language schools [...] have an excellent record of 're-training' successfully supported children in mainstream schools - breaking such structures is irresponsible from a professional point of view, "says Hanns Rüdiger Röttgers, a specialist in psychiatry and psychotherapy at the Münster University of Applied Sciences .

The Philologists Association Baden-Württemberg admits that a common goal-oriented teaching of disabled and non-disabled students at high schools can be successful. However, he protests against the interpretation that the UN Convention requires teaching that is different in purpose. Everyone who goes to a grammar school must in principle be able to obtain the Abitur (if necessary with massive help). People with severe intellectual disabilities are therefore out of place in a grammar school. Organized philologists position themselves similarly in other countries in Germany.

Inadmissible interference with parental rights