Pierre-Louis Guinand

Pierre-Louis Guinand (born April 20, 1748 in La Corbatière, municipality of La Sagne ; † February 13, 1824 in Les Brenets ) was an optician from today's canton of Neuchâtel (Neuchâtel). Commissioned by Joseph Utzschneider (1763–1840), he set up the world's first hut for the production of optical glass in the secularized Benediktbeuern monastery in 1805 , which later enabled Joseph Fraunhofer (1787–1826) to develop his genius as a scientist. After the decline of Bavarian optics, Guinand's relatives and successors dominated the world market for optical glass for a long time.

From the center of the watch industry

In a memorandum that the manufacturers Adolphe Thibaudeau and Georges Bontemps read in front of the Académie des sciences in Paris in 1828, the following description of the circumstances under which the process for manufacturing optical glass was invented is found:

“A simple man, unknown with the advances in science, the perfections and great undertakings in industry, but gifted with this research and perseverance, with this gift of invention, which can be called the premonition of knowledge, worked in the mountains of Switzerland solving a problem to which so many bright minds seemed to have given up. "

The Englishman Chester Moore Hall had discovered in 1729 that the combination of a converging lens made of crown glass having a diverging lens made of flint glass , the chromatic aberration (different refractive colors when passing from one medium to reverse in the other), and subsequently the first telescopes with achromatic ( color-corrected) lenses . His invention was economically evaluated in the 1750s by John Dollond . Obtaining suitable homogeneous pieces for the production of the lenses was difficult with the leaded flint glass. They were sometimes found - but only up to a diameter of about 10 cm - in the huts that made lead crystal for jewelry, drinking glasses, candlesticks, etc. in England and later also in France . As Scottish physicist David Brewster wrote in 1825, the discovery of a method of making flint glass for achromatic telescopes was almost a matter of national pride for seventy years. But prizes such as the 12,000 francs that the Académie des sciences promised the inventor in 1786 had not led to success.

Guinand came from the Prussian-Swiss Principality of Neuchâtel, where the Geneva watch industry had found a second home because there were no guild barriers to restrict the entrepreneurial spirit of the Calvinist population. Although he grew up at 1080 m above sea level and - like crowned heads back then - at war with the spelling of his mother tongue, Guinand was not a simple mountain man. His relatives included bankers in London and the largest employer in the Palatinate , the iron industrialist and later Bavarian baron Ludwig Gienanth . The grandfather had made it to the position of capitaine lieutenant in a French Swiss regiment. The illegitimate but later legitimized father made cases for Neuchâtel pendulum clocks. Guinand himself supplied the famous automaton maker Pierre Jaquet-Droz (1721–1790) and produced well-paid gongs for the striking mechanisms of repeater watches . (So he wasn't a bell-founder, as it is sometimes called.) Widowed twice and divorced once, he had six surviving children and several stepchildren.

His passion, which he said he sacrificed 1200–1400 Louisdors (13,200–15,400 guilders ), was the production of homogeneous flint glass for optical devices. He began at the age of 20 - as Madame de Charrière wrote in 1793, for lack of good glasses - he built special ovens for this in 1775 and 1787, began in 1792 with casting and then probably with the so-called lowering (re- softening ) of lens blanks , in 1798 with the Homogenize the liquid glass with a clay stirrer. His second passion was the construction of achromatic telescopes that were on a par with the English ones, from designing - graphically, not mathematically - and from grinding the lenses to casting and turning the brass parts as well as working the wood to preparing the paint.

In his home town of Les Brenets, where Guinand settled in 1781, the forests of the Jura , the 27 m high waterfall of the border river Doubs ( Saut du Doubs ) and a mill pond provided the necessary energy for melting and machining the glass. Already a citizen of Les Ponts-de-Martel and Les Brenets, in 1792 Guinand had his sovereign, King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia , grant him citizenship of the county seat of Valangin . In those years he began to produce pieces of high-quality flint glass, which were significantly larger than the 10 cm diameter mentioned, and which in 1798 was applauded by the astronomer Joseph-Jérôme Lalande in Paris . In 1802, 54-year-old Guinand took 19-year-old Rosalie Bouverot (1783–1855) from Chaillexon in France (municipality of Villers-le-Lac ) into the house, who from then on actively supported him.

Swiss revolutionaries in the Pfaffenwinkel

On Lalande's advice, Guinand processed his glass himself for the time being. In order to benefit from his invention, however, he needed capital. The fact that he turned to underdeveloped Bavaria in search of it has to do with the revolution from above that the Elector Max Joseph , who was educated in France, and his minister Maximilian von Montgelas carried out there, and with the surveying of the country initiated by France. Swiss revolutionaries who were persecuted by Napoleon Bonaparte after the dissolution of the Helvetic Republic acted as mediators . It was probably through Jean-Henri Weiss, the author of the Atlas Suisse , that the chief miner Johann Samuel von Gruner , who had emigrated to Munich, got to know Utzschneider, who was involved in mapping Bavaria. He had been the most important head of a group of revolutionaries who were working towards the formation of a South German Republic, but had been denounced by the French and removed from his office as State Secretary by the Elector. Gruner arranged for Guinand Utzschneider to deliver glass samples in early 1804 and a memorandum in June. In the latter he agreed to sell his trade secrets to the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and to move to Bavaria. Among other things he wrote:

"I trust that, in view of the difficulties to be overcome, there can be no competition, that the stubborn minds who insist on repeating attempts for so long and discarding every melt are all too rare (...)"

The now entrepreneur Utzschneider, who was supposed to present Guinand's paper to the academy, apparently kept it to himself, at least nothing is known of any treatment by the academy. In August 1804, Utzschneider founded the Mathematical-Mechanical Institute in Munich with Georg Reichenbach and Joseph Liebherr . This, too, was likely to have happened at the suggestion of Gruner, who described the institute as his child. Utzschneider's partners had associated themselves in 1802 to manufacture measuring devices ( theodolites ), but they lacked capital. Flint glass for the lenses was also not available from England, which was again waging war against France from 1803 onwards. At first Utzschneider apparently tried to produce such glass himself. The glassworks of the secularized Ettal monastery in Grafenaschau , into which his sister had married, offered itself. Guinand seems to have only been brought to Bavaria by Utzschneider when his own attempts had failed. (The glass praised by the astronomer Ulrich Schiegg in October 1805 probably came from Les Brenets.)

Utzschneider's first encounter with Guinand took place in early 1805. It was arranged by Gruner and the writer Heinrich Zschokke , former governor of the Helvetic Republic and later the author of a history of Bavaria. The meeting point was Aarau , the place of residence of the silk ribbon manufacturer and former Senator of the Helvetic Republic, Johann Rudolf Meyer . He had financed the Atlas Suisse and in 1804, with the help of Gruner and Utzschneider , acquired three secularized monasteries in the latter's home, the Upper Bavarian Pfaffenwinkel . (In Benediktbeuern, Guinand was later thought to be an Aargauer.) Utzschneider had Guinand carry out experimental melting at his own expense. In May 1805 he offered 55,000 guilders for the Benediktbeuern monastery, which a Bohemian glass manufacturer had bought but not paid for. Two weeks later he asked Guinand to come to Munich. In July he received the building in Benediktbeuern. At the end of August he visited Guinand again, this time in Les Brenets. He paid him an advance of 100 Louisdors (1100 guilders) and thus obliged him to move to Benediktbeuern. This did not prevent Utzschneider later from claiming that the Swiss had followed him without an assignment.

World's first production facility

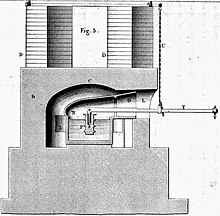

Guinand let his son Aimé (1774–1847) continue the business in Les Brenets, whom he had initially wanted to take with him to his new place of work. He arrived in Benediktbeuern in October 1805, when Napoleon was driving the invaded Austrians out of Bavaria. Together with Rosalie Bouverot, he transformed the former wash house of the monastery into "what was then the only hut in the world for optical glass", which is now known as the " Fraunhofer Glassworks ". In his memorandum he called for two different ovens for the flint glass and one for the crown glass. A big problem was the procurement of suitable raw materials, which accounted for a third of the production costs, namely the clay for the manufacture of the melting ports.

With a ten-year contract from July 1806, Guinand was not only the technical director of the works for optical glass, but also an institute for the manufacture of telescopes. Because a maximum of glass for 50 lenses per year should be delivered to the Mathematical-Mechanical Institute in Munich, but everything else should be processed in Benediktbeuern. A hut for hollow glass (white glass) with several ovens, which now no longer exists, was placed under Guinand's control , for whose construction Utzschneider had the parish church of Benediktbeuern demolished. Utzschneider only retained the overall supervision, the selection of workers, the sale of the products, the bookkeeping and the preparation of the annual accounts, which Guinand had to approve. In addition to free accommodation and firewood, the latter received 1,000 guilders a year, half of which was for the surrender of his trade secrets, which he handed to Utzschneider in the form of an extensive, illustrated memorandum, and for keeping them to everyone. For this purpose, Guinand and Rosalie Bouverot - his fourth wife since that year - had to make the flint and crown glasses themselves. Utzschneider also granted Guinand a 20 percent share in the profits and the right to appoint one of his sons as his successor. This meant Aimé, who was not prohibited from continuing operations in Les Brenets.

If optical glass, telescopes and hollow glass were profitable, a furnace for the production of cast glass was to be built, with a 50 percent share in the profits for Guinand. If the company was profitable, Rosalie Bouverot was to receive a bonus of 18 louisdors (198 guilders) annually and, after the death of her husband, a widow's pension of 250 guilders. In addition, Utzschneider Guinand made a donation of 80 Louisdors (880 guilders). There is therefore no reason to believe that the Swiss did not keep their promises. This is exactly what is assumed by Bavarian authors who represent the glassworks in Benediktbeuern as the sole work of local people (Utzschneider or Fraunhofer). Utzschneider biographer Ivo Schneider claims that his protagonist “and nobody else” created the prerequisites for the production of optical glass in Benediktbeuern.

Instead of 10 years, Guinand only remained boss for 10 months. As early as February 1807, he had to sign a new ten-year contract, which came into effect in May, which, although it provided him with additional income, restricted his area of responsibility. This probably not only because Utzschneider was called back to the civil service, but also because Guinand could not get along with the (Bohemian) workers of the hollow glass works. He became an employee of the Mathematical-Mechanical Institute in Munich, where he was supposed to deal with the optics and mainly with the setup ( tripods ) of the telescopes - a provision that, according to Adolf Seitz, was not implemented. Guinand was not allowed to hire or fire workers. It was implemented that he should continue to melt optical glass several times a year in Benediktbeuern. His wife had to help him. The two were allowed to keep their apartment in the monastery. The question of succession was reorganized, with Guinand undertaking to initiate a person to be appointed by Utzschneider in the secrets of glassmaking. He or, in the event of his death, his family received 1,600 guilders annually during the term of the contract, which meant an increase in salary of 60 percent. After the contract expired, Guinand was entitled to a pension of 800 guilders, provided that he did not instruct anyone in the manufacture of flint and crown glass, nor sold any such glass or took on another position without permission. On the other hand, he did not participate in the company's ( illusory ) profits. Ultimately, Utzschneider assured Guinand that he was “genuinely devoted to him for the sake of his legality and his knowledge”. But this was little consolation for the demoted . Utzschneider does not seem to have written until 1813. And apparently he no longer felt bound by his own promises.

Ousted by Fraunhofer

The mirror maker and trim grinder Joseph Fraunhofer, hired by the Mathematical-Mechanical Institute in 1806 and led by Schiegg, ousted Joseph Niggl as an optician in 1807. From the same year he worked in Benediktbeuern. In February 1809, Utzschneider founded an optical institute there, and made the 21-year-old Fraunhofer its director and partner. Apparently he took over the calculation of the objectives and the grinding of the lenses in the new company Utzschneider, Reichenbach and Fraunhofer . He worked with the mechanic Rudolf Sigismund Blochmann (1784–1871). "So that in the future Mr. Guinand is employed more usefully than before ”, Fraunhofer wanted to limit his area of responsibility to melting glass and rotating frames for lenses of telescopes, which Utzschneider biographer Schneider describes with undisguised malice as the beginning of the“ dismantling ”of the Swiss. In Fraunhofer's opinion, Guinand was not usable for grinding and polishing lenses, probably because he rejected the labor-sharing process introduced by him with machines operated by auxiliary staff.

In August 1809, Utzschneider named Fraunhofer to whom Guinand had to initiate the art of glass melting. On this occasion Therese Countess von Seinsheim, one of the two chambermaids of the widowed Electress Maria Leopoldine of Austria-Este , appears as Utzschneider's proxy. This suggests that Utzschneider had involved Maria Leopoldine, whom he advised on financial matters, in the purchase of Benediktbeuern. Since the Optical Institute was in deficit, the Countess seems to have supervised the sale of the instruments produced by name. When Utzschneider finally released business figures in 1813, there was a loss of 60,000 guilders.

Until then, Fraunhofer had only been allowed to watch in the glassworks, but in 1811 Guinand was also placed under the supervision of the almost 40-year-old boy there. In an effort to do justice to both the teacher and the student, Fraunhofer biographer Moritz von Rohr postulated that the two had developed an improved "Guinand-Fraunhofer process for the preparation of optical glass" within just two years. A letter published by the same author speaks against this hypothesis , in which Guinand complained to his son Aimé in 1812 that Fraunhofer treated him like a simple worker. In addition to differences of opinion, this may have contributed to the fact that, according to Rohr, the two were opposite psychological types , in the terminology of the time: sanguine (Guinand) and melancholic (Fraunhofer). Today Fraunhofer - according to Antonin von Schlichtegroll "one of the noblest and purest spirits who have ever lived" - would be described as ingenious autistic people.

Guinand manufactured flint and crown glass for 5000 achromatic lenses in Benediktbeuern according to its own information. Meanwhile in Les Brenets, the business run by Aimé, on which the care of Guinand's children depended, was threatened. In order to avert the ruin of his son, to whom he had already sent his student Wilhelm Strahl (1812) and his wife Rosalie (1813) to help, Guinand retired at the age of 66 (May 1814), with a later one Return to Benediktbeuern reserved. In February 1814, co-owner Reichenbach left the Optical Institute.

In order to oblige the Guinand couple "not to arrange the manufacture of flint and crown glass with anyone, to teach nobody about them and not to deal with optics at all", Utzschneider Guinand paid two annual pensions (a total of 1,600 guilders) in advance. According to the Swiss astronomer Rudolf Wolf , this shows how much people feared Guinand's competition "and how petty it was later on by Utzschneider to reduce his earnings". ( Again, Aimé Guinand was not included in the non- competition clause.)

Underestimated in Bavaria

In 1815 Guinand Utzschneider asked for permission to set up a company with third parties. In January 1816, Utzschneider confided in him that the continued existence of the company in Benediktbeuern was in danger. In his reply, Guinand expressed vivid regret about this. He reported that, thanks to new discoveries, he had obtained glass of unmatched quality in two small test melts. He also made a very good lens with an 8 Paris inch (21.7 cm) aperture and is confident that he can go beyond that. He was ready to take over the technical management of the optical institute and the hollow glassworks again under the conditions of the contract of 1807, if only "Fraunkaufer" (Fraunhofer) and "Blackmann" (Blochmann) had nothing to do there and the workers were subordinate to him . For his future successor he suggested his wife: “Your Excellency has a young, completely devoted, intelligent, hardworking and capable person (in service) who is not afraid to do manual labor. I will teach her completely everything I know so that she will be able to replace me after my death. "

Guinand's letter arrived at an inconvenient time: Fraunhofer had just learned that Strahl, through whom Guinand was hoping to receive urgently needed orders, would buy King Wilhelm I of Württemberg a telescope with a lens of at least 4 inches (approx. 10 cm) for 1000 guilders. Diameter had sold, which he wanted to have made himself including the glass. However, Fraunhofer believed it knew that the lens mentioned had been ground by Guinand in Benediktbeuern. When Utzschneider did not appreciate Guinand's answer, the latter waived the further payment of the pension. In Moritz von Rohr's opinion, it would have been “undoubtedly infinitely more useful for Utzschneider's company to take back the old smelting foreman who is ready to return with his well-informed wife.” The Jena optician continues:

“What the abolition of the competition by the two most capable foreign experts, old Guinand and his wife, as well as the cutting off of the opportunity to teach Guinand's more energetic son Henri in the glass compartment, would have meant for the Benediktbeurner Anstalt, especially after Fraunhofer’s premature death, cannot at all be measured. "

Utzschneider has never been so close to his goal of uniting the production of all optically useful glass in his hand. But the Guinand couple have apparently been "hugely underestimated". In order to be able to reap the fruits of his life's work, Guinand made plans to emigrate to America (1817), Russia (1818), France (1820) and England (1822). And while Fraunhofer only produced optical glass for its own use, Guinand began supplying Paris in 1818. Noël-Jean Lerebours and Robert-Aglaé Cauchoix built far more telescopes with glass from him than Fraunhofer. When Lerebours visited Les Brenets in 1820, he immediately bought all the glass there, even the glass that did not yet meet Guinand's own quality standards.

In 1818 the widowed Electress got King Max Joseph to buy back Benediktbeuern. Utzschneider received 250,000 guilders for this, some of which he probably owed Maria Leopoldine. He moved the Optical Institute to Munich in 1819. Also in 1819, a ward of Johann Rudolf Meyers who had worked at Reichenbach founded the instrument building company Kern & Co. in Aarau , which existed until 1991. When Guinand was visited in Les Brenets in the same year by the future King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, he rebuked him for having touched a valuable pane of flint glass.

While Fraunhofer died at the age of 39, to which the heat and fumes from the glass furnace are said to have contributed, Guinand was 75 years old. According to a plaque on the former church of Les Brenets (now the municipal administration), he was buried near its tower. His widow first ran the business in Les Brenets with her stepson Aimé and then built a new smelter in Chaillexon with the pharmacist Théodore Daguet (1795–1870). Finally, Henri Guinand (1771–1851), who had emigrated to France as a watchmaker, began to produce glass in Paris.

Stir and lower

The fame of Fraunhofer, which under the influence of nationalism made him the subject of a cult , is primarily based on his achievements as a scientist. ( He did not use the spectral lines discovered by William Hyde Wollaston in 1802 until Guinand returned to Les Brenets, to measure the refractive and color scattering power of glasses.) Fraunhofer also reached a higher level than Guinand in the manufacture of lenses and telescopes . However, as his son Aimé emphasized, he was not the only optician of his time who could make good lenses from good glass. And without the preliminary work of Guinand, who had made the breakthrough in the manufacture of flint glass, Fraunhofer would not have been able to develop his genius.

The Swiss invented the process called guinandage in French . It consists in homogenizing the liquid glass with an incandescent stirrer ( guinand ) made of the same clay as the melting port . After this stirrer had had a mushroom shape in the first few years, Guinand made it cylindrical in 1805 during the trial melts for Utzschneider , which proved to be advantageous.

The new inventions that Guinand Utzschneider offered in 1816 probably related to the process of lowering, which in Benediktbeuern was called Ramollieren (from French ramollir ). The glass takes on the shape of a disc by being softened in round clay bowls without losing any of its quality. According to his friend Édouard Reynier (1791–1840), Guinand freed the resulting lens blanks from defective spots with roulette , rolled them up again and repeated the process until every anomaly was gone. He even managed to fuse several pieces of glass into a single, perfectly homogeneous one.

Not only that Fraunhofer invented homogeneous glass, but also that the glass he made was “far better than that of Guinand”, as Bavarian authors claim, is a myth . As a glassmaker, the teacher did not lag behind the student. Michael Faraday , who tried to produce optical glass himself for five years, gave a Solomonic judgment in 1830 : "Both these men, according to the best evidence we can obtain, have produced and left some perfect glass in large pieces (...)"

Guinand glass refractors with lenses were awarded gold medals at the French industrial products exhibitions of 1819 and 1823. The specimen exhibited by Cauchoix last year had a Parisian foot (32.5 cm) opening, which made it the largest in existence at the time. Cauchoix had paid 7,000 francs for the flint glass. Louis XVII is said to have congratulated him and invited Guinand, who was indisposed, to Paris. In 1823 the jury , to which François Arago belonged, wrote about a Lerebours refractor of 9.5 Paris inches (25.7 cm) opening: "Rien de plus parfait n'est certainement sorti des ateliers d'aucun opticien." In 1827 Cauchoix placed a telescope with a 35.2 cm aperture, and in the following year Thibaudeau and Bontemps presented the Académie des Sciences with a 38 cm diameter flint glass plate, which they had produced with the help of Henri Guinand.

For comparison: The lens of Fraunhofer's famous telescope for the Dorpat observatory (today Tartu , Estonia ) from 1824 had an aperture of just 9 Paris inches (24.4 cm). Fraunhofer tested the streak content of the glass in 1825 using a method that Guinand had brought back from Paris in 1798. And like Guinand, he too produced more rejects than successful melts throughout his life.

Without Utzschneider, Guinand would not have been able to apply his inventions industrially. For a long time he was treated better by Utzschneider than by Fraunhofer. His former employer viewed the fact that he became a competitor after his return to Les Brenets as treason. For the sake of his patron, Zschokke does not mention Utzschneider in a report on Benediktbeuern Guinand published in 1817, although he was involved in his appointment to Bavaria. When Utzschneider ran the Optical Institute on his own after Fraunhofer’s death, he exaggerated the part that he himself had had in the creation of the glassworks, and even claimed that Guinand had only shown him the mistakes that had to be avoided and then stole the production secret. And Ivo Schneider's Utzschneider biography, published in 2014, gives the impression that a show-off who had traveled to Germany tried to exploit his Bavarian patron .

Mastery of the world market

Utzschneider's successor Georg Merz (1793–1867) still supplied refractors with lenses of 38 or 38.1 cm aperture for the Pulkowo Observatory near Saint Petersburg (1839) and the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1847). Then the Munich institute finally lost its leadership in telescope construction. A pane of glass with a diameter of 50.8 cm had to buy it from Henri Guinand's son-in-law Charles Feil (1824–1887) in Paris. The last owner of the institute was Zschokke's grandson Paul (1853–1932).

After Arago and Jean-Baptiste Dumas had attended a melt of bubble- and streak-free flint glass, the Académie des sciences Henri Guinand awarded the Lalande Prize for 1837. In 1840, Henri Guinand and his former Associé Georges Bontemps (1799-1883) won a competition Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale and received 8,000 and 6,000 francs in prize money. A platinum medal each went to Rosalie Guinand in Chaillexon and her former colleague Alexis Berthet, who ran a glassworks in neighboring Morteau .

Just as the Guinand method was claimed in Bavaria, it was now celebrated together with photography as a “purely French invention”. At the same time, it experienced a new heyday in its country of origin, when Rosalie Guinand and Théodore Daguet founded a glassworks in Solothurn in 1831 , which acquired “an important reputation for large and very clean panes for the objectives of celestial telescopes”. In the revolutionary year of 1848, Bontemps emigrated to Birmingham , where he manufactured the flint glass for the 61 cm lens of the Craig telescope in Wandsworth near London (1852). The glass for the refractors of the Lick Observatory near San José (California) (1888), the Yerkes Observatory near Chicago (1897) and the World Exhibition of Paris (1900) of 91.4 cm, 101, The 6 cm and 125 cm openings came from Feil and his successor Édouard Mantois (1848–1900).

In summary, Rudolf Wolf wrote:

“After the construction of larger achromatic refractors had faced seemingly insurmountable difficulties for several decades due to the impossibility of obtaining corresponding homogeneous flint glass masses , Guinand and his talented student Fraunhofer earned the merit of making significant progress in this area as well, and during then For some time the successors of the latter occupied the first rank, so later they were again surpassed by those of the former. "

literature

There is no comprehensive work on Guinand. The starting point of the article is:

- How Bavaria came to an optical industry. In Peter Genner: After the end of the monastery rule - Swiss revolutionaries in the Pfaffenwinkel . In: Der Welf , Yearbook of the Historisches Verein Schongau - Stadt und Land 2013, pp. 69–192 ( digitized version ), here: pp. 137–142.

Detailed texts about Guinand:

- Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), 25th volume, 9th year, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236 ( digitized version ); Excerpts from Charles-Philippe de Bosset's translation : Some Account of the late M. Guinand, and of the Important Discovery made by him in the Manufacture of Flint Glass for Large Telescopes. In: Mechanics' Magazine (…), London / Dublin, January 29, 1825, pp. 292–295 ( digitized version ); Review by David Brewster in: The Edinburgh Journal of Science, Vol. 2, No. 4, April 1825, pp. 348-354 ( digitized ).

- Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197.

- Paul Ditisheim : Le centenaire de Pierre-Louis Guinand. In: L'Astronomie: revue mensuelle d'astronomie, de météorologie et de physique du globe et bulletin de la Société astronomique de France (Paris) 39/1925, pp. 177–197 ( digitized version ).

- Moritz von Rohr : Pierre Louis Guinand, b. April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197.

- Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926.

- Moritz von Rohr: P. L. Guinand's instruction on glass melting. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 48, Berlin 1928, pp. 438-453, 501-514, 548-559, 600-613.

- Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described from sources. Academic Publishing Company , Leipzig 1929.

- Moritz von Rohr: A newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928-1935, pp. 222-241.

- Moritz von Rohr: A contribution to the history of optical glass (until the opening of the Jena glassworks). In: Nova Acta Leopoldina. New episode, volume 2, issue 1 f., Hall a. P. 1934, pp. 147-202.

Other printed sources and illustrations:

- Prix proposé par l ' Académie Royale des Sciences , pour l'année 1791. In: Le Journal des sçavans (Paris), February 1789, p. 122 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Ulrich Schiegg : Astronomical news from Bavaria. In Franz Xaver Freiherr von Zach (ed.): Monthly correspondence for the transport of the earth and sky customer (Gotha), Volume 12, October 1805, pp. 357–366, here: pp. 360 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Mémoire lu à la séance du 11 December 1809 de la Classe des sciences physiques et mathématiques de l ' Institut . In Aimé-Gabriel d'Artigues: Sur l'art de fabriquer du flint-glass bon pour l'optique, P. Gueffier, Paris 1811, p. 7 ff. ( Digitized version ).

- The workshops in Benediktbeurn. In Heinrich Zschokke : About the history of our time, born in 1817, Heinrich Remigius Sauerländer , Aarau, pp. 559-573 ( digitized version ).

- Report du jury central sur les produits de l'industrie française (…), Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1819, pp. 258–261 ( digitized version ).

- Rapport sur les produits de l'industrie française, présenté, au nom du jury central (…), Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1824, p. 325 f. ( Digitized version ); Paris 1828, p. 380 ( digitized version ).

- Joseph from Fraunhofer. In: Supplement to the Allgemeine Zeitung (Augsburg), 16. – 18. August 1826, pp. 909 f., 913 f., 917 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Joseph von Utzschneider : Brief outline of the life story of Dr. Joseph von Fraunhofer (…) Rösl, Munich 1826 ( digitized version ).

- Report of the Committee appointed by the Council of the Astronomical Society of London, for the purpose of examining the Telescope constructed by Mr. Tulley (…) In: Memoirs of the Astronomical Society of London, Volume 2, Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, London 1826, pp. 507-511 ( digitized version ).

- Decouverte d'un procédé régulier pour la fabrication du flint glass. In: Le Globe, Recueil philosophique, politique et littéraire (Paris), November 1, 1828, p. 798 ( digitized version ).

- Fabrication du flint-glass en France, d'après un procédé régulier. In: Bibliothèque universelle, des sciences, belles-lettres et arts (…), 13th year, volume 39, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1828, pp. 173–176 ( digitized version ).

- Explanation of the royal. go. Rathes J. v. Utzschneider, against some statements in the Bibliothèque universelle and the Globe, about the production of flint glass . In: Supplement to the Allgemeine Zeitung ( Augsburg ), January 25, 1829, p. 99 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Réclamation de Mr. Aimé Guinand. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettres et arts (…), 15th year, Sciences et arts, volume 43, Genève / Paris 1830, pp. 222–228 ( digitized version ).

- Michael Faraday : The Bakerian Lecture - On the manufacture of Glass for optical purposes. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, year 1830, part 1, pp. 1–57 ( digitized version ).

- Compte rendu des séances de l'Académie des sciences (Paris). Volume 6, June 25, 1838, p. 922 ( digitized version ); Volume 7, August 13, 1838, p. 354 ( digitized version ).

- Rapport sur le concours relatif à la fabrication du flint-glass et du crown-glass; par M. Payen. In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Paris) 38/1839, pp. 470-473 ( digitized version ).

- Description du procédé de fabrication du flint-glass; par M. (Henri) Guinand, rue Mouffetard, 283. In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Paris) 39/1840, pp. 468-472 ( digitized version ).

- Franz Eduard Desberger: In memory of the secret advice, Joseph von Utzschneider (...). In: Kunst- und Gewerbe-Blatt. (…), Volume 26, Munich 1840, columns 137–158 ( digital copy ).

- Memoirs of Karl Heinrich Ritters von Lang (…), Part 2, Friedrich Viehweg and Son, Braunschweig 1842, pp. 216–221 ( digitized version ).

- Georges Bontemps: Exposé historique et pratique des moyens employés pour la fabrication des verres filigranés et du flint-glass et crown-glass. In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Paris) 44/1845, pp. 183–195, 236–245, here: pp. 239–241 ( digitized version ).

- Pierre-Louis Guinand by Corbatiere 1748–1824. In: Rudolf Wolf : Biographies on the cultural history of Switzerland. 2. Cyclus, Orell, Füssli & Comp. , Zurich 1859, pp. 299-308 ( digitized version ).

- Leonhard Jörg: Fraunhofer and its services to optics ( dissertation ). J. G. Weiß, Munich 1859, pp. 19, 35 ( digitized version ).

- Paul-Louis Guinand (sic). In: Frédéric-Alexandre-Marie Jeanneret, James-Henri Bonhôte: Biography neuchâteloise. Volume 1, Eugène Courvoisier, Le Locle 1863 ( digitized version), pp. 448–459.

- Rudolf Wolf: Notes on Switzerland. Cultural history (continued). In: Quarterly publication of the Natural Research Society in Zurich , 12/1867, pp. 218–220, 401 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Georges Bontemps: Guide du verrier: traité historique et pratique de la fabrication des verres, cristaux, vitraux. Librairie du Dictionnaire des arts et manufactures, Paris 1868, pp. 650-690 ( digitized version ).

- Louis Figuier: Les merveilles de l'industrie ou Description des principales industries modern. Volume 1, Furne & Jouvet, Paris 1873, pp. 137-144 ( digitized version ).

- Report fait par MM. (Stanislas) Cloëz et (Victor) de Luynes (…) sur les verres d'optique, présentés par M. Charles Feil (…) In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Paris ), 3rd series, 4/1877, pp. 422-426 ( digital copy ).

- Rudolf Wolf: Handbook of astronomy, its history and literature. 1st half volume, F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, pp. 338-340 ( digitized version ).

- Carl Max v. Bauernfeind : Utzschneider, Josef v. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie . 39th volume, Duncker & Humblot , Leipzig 1895, pp. 420-440 ( digitized version ).

- Ernst Voit : Precision mechanics in Bavaria. In: Representations from the history of technology, industry and agriculture in Bavaria. R. Oldenbourg , Munich 1906, pp. 169-195.

- Fritz-Albin Perret: Pierre Louis Guinand, "L'opticien": contribution biographique offerte aux bibliothèques publiques des Brenets. Self-published, Les Brenets 1907.

- Paul Nicolardot: Les premiers verres d'optique. In: La Nature (Paris), December 24, 1921, pp. 407-412 ( digitized version ).

- Ernst Voit: 1815–1915. Hundred years of technical inventions and creations in Bavaria. Centenary of the Polytechnic Association in Bavaria (...) R. Oldenbourg, Munich / Berlin 1922.

- Walther Zschokke: On the history of optical glass . In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde , Volume 42, Berlin 1922, pp. 208–215.

- Henri Bühler: Un autodidacte de génie: le verrier Pierre-Louis Guinand. In: Revue internationale de l'horlogerie ( La Chaux-de-Fonds ) 25/1924, pp. 273–276, 289–293.

- Johann Valentin Keller-Zschokke: A Swiss smelter for optical glass in Solothurn 1831–1857 and Theodor Daguet, manufacturer of optical glass 1795–1870. Vogt shield, Solothurn 1926.

- Jean Risse: Théodore Daguet, fabricant de verres d'optique. In: Annales fribourgeoises ( Freiburg im Üechtland ) 14/1926, pp. 145–155 ( digitized version ).

- Otto Paul Krätz, Elisabeth Renatus: On the history of the glassworks in Benediktbeuern . In: Kultur & Technik ( Deutsches Museum München) 7/1983, pp. 248–256 ( digitized version ).

- Alto Brachner: History of Munich optics - origins, activities, observatories, locations. Spread 1750–1984. Dissertation at the Technical University of Munich 1986.

- Hans-Peter Sang: Joseph von Fraunhofer, researcher, inventor, entrepreneur. Peter Glas, Munich 1987.

- Josef Kirmeier, Manfred Trend (Hrsg.): Splendor and end of the old monasteries. Secularization in the Bavarian Oberland 1803. House of Bavarian History , Munich 1991, ISBN 3-927233-12-9 , pp. 341–354.

- Hans-Peter Sang: Glass from the monastery. The Fraunhofer glassworks in Benediktbeuern. In: Culture & Technology (Deutsches Museum München) 17/1993, p. 28 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Sylvia Krauss-Meyl : The royal family's “ enfant terrible ”. Maria Leopoldine , Bavaria's last Electress (1776–1848). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 1997, ISBN 3-7917-1558-5 .

- Myles W. Jackson: Spectrum of Belief. Joseph from Fraunhofer and the Craft of Precision Optics. MIT Press , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2000.

- Pierre-Arnold Borel: Branche de Pierre Louis Guinand 1748–1824, le célèbre opticien, communier des Brenets et des Ponts-de-Martel , bourgeois de Valangin . In: Familienforschung Schweiz, Jahrbuch 2002, pp. 162–171 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Ventzke: Fraunhofer's successor in the Optical Institute in Munich. In: Contributions to the history of astronomy. Volume 7, Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 170-188.

- James Barton, Claude Guillemet: Le verre: Science et technologie. EDP Sciences, Les Ulis 2005, ISBN 2-86883-789-1 .

- Fraunhofer Society (ed.): Fraunhofer in Benediktbeuern. Glassworks and workshop . Munich 2008 ( digitized version ).

- Ivo Schneider : Joseph von Utzschneider - vision and reality of a new Bavaria ( contributions to the history of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet , Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version), pp. 278–321 et passim .

- Hans Weil: La Sagne and his pioneers Daniel JeanRichard, Pierre-Louis Guinand and the Chronométrier and Régleur Paul Perret. Berlin 2014 ( digitized version), unpaginated.

Web links

- Karin Marti-Weissenbach: Guinand, Pierre Louis. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Pierre-Arnold Borel: La famille Guinand, des Brenets, bourgeoise de Valangin. Société Neuchâteloise de Généalogie. ( Digitized version )

References and comments

- ^ Moritz von Rohr : A newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928–1935, pp. 222–241, here: p. 235.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), 25th volume, 9th year, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: p. 142 ( digitized ), erroneously names 1823 as the year of death.

- ↑ Découverte d'un procédé régulier pour la fabrication du flint glass. In: Le Globe, Recueil philosophique, politique et littéraire (Paris), November 1, 1828, p. 798 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Mémoire lu à la séance du 11 December 1809 de la Classe des sciences physiques et mathématiques de l ' Institut . In Aimé-Gabriel d'Artigues: Sur l'art de fabriquer du flint-glass bon pour l'optique, P. Gueffier, Paris 1811, p. 7 ff. ( Digitized version ). The Journal of the Society of Arts (London), July 21, 1876, p. 851, mentions a 4.5 inch (11.4 cm) aperture telescope built by Van Deijl in Amsterdam in 1781 .

- ^ The Edinburgh Journal of Science, Vol. 2, No. 4, April 1825, p. 348 ( digitized ).

- ^ Prix proposé par l ' Académie Royale des Sciences , pour l'année 1791. In: Le Journal des sçavans (Paris), February 1789, p. 122 f. ( Digitized version ); Rudolf Wolf : Handbook of astronomy , its history and literature. 1st half volume, F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, p. 339 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Neuchâtel was until 1848 the Principality since 1707 (except for 1806-1814) belonged to the King of Prussia , but also to 1798 facing site of the Confederation and in 1815 the Swiss canton .

- ↑ Neuchâtel clocks could be found all over the world from the 18th century. The technically extraordinarily high-quality watch industry was organized in the publishing system and extremely labor-sharing . It made the cities of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle rich and the population receptive to new ideas. See Lionel Bartolini: Neuchâtel (Canton). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ See Pierre-Arnold Borel: Branche de Pierre Louis Guinand 1748-1824, le célèbre opticien, communier des Brenets et des Ponts-de-Martel , bourgeois de Valangin . In Swiss Society for Family Research (Ed.): Family Research Switzerland, Yearbook 2002, pp. 162–171 ( digital copy ); the same: La famille Guinand, des Brenets, bourgeoise de Valangin. Société Neuchâteloise de Généalogie. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Myles W. Jackson: Spectrum of Belief. Joseph from Fraunhofer and the Craft of Precision Optics. MIT Press , Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2000, p. 58.

- ↑ Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197.

- ^ Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 9.

- ↑ ( Isabelle de Charrière :) Suite de la Correspondance d'un François et d'un Suisse. (Neuchâtel 1793), letter 4, p. 6.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr : Pierre Louis Guinand, b. April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197, here p. 197.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (...), 25th volume, 9th year, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: p. 227 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Hans Weil: La Sagne and his pioneers Daniel JeanRichard, Pierre-Louis Guinand and the Chronométrier and Régleur Paul Perret. Berlin 2014 ( digitized version), unpaginated.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), Volume 25, Volume 9, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: pp. 155 f. ( Digitized version ); French text of an undated memorandum from Guinand by Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 8-13. After his unhappy third marriage separated, Guinand obtained a total of five passports in 1797, 1798, and 1801.

- ↑ Other spelling: Bouberot.

- ↑ Weiss was stationed in Bavaria as a French engineer captain from 1801 to 1803.

- ↑ See Heinrich Scheel : Süddeutsche Jakobiner (...) Akademie-Verlag , Berlin 1962, pp. 650–653, 690 f.

- ↑ Based on the French text of an undated memorandum from Guinand by Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 12.

- ^ Hans-Peter Sang: Joseph von Fraunhofer, researcher, inventor, entrepreneur. Peter Glas, Munich 1987, p. 27; Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - vision and reality of a new Bavaria ( contributions to the history of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version), pp. 288–291 incl. Note 628.

- ↑ Pierre-Louis Guinand by Corbatiere ( sic ). 1748-1824. In Rudolf Wolf: Biographies on the cultural history of Switzerland. 2. Cyclus, Orell, Füssli & Comp. , Zurich 1859, pp. 299–308, here: p. 302 / note. 5 ( digitized version ).

- ^ According to Otto Paul Krätz, Elisabeth Renatus: On the history of the glassworks in Benediktbeuern . In: Kultur & Technik ( Deutsches Museum München) 7/1983, pp. 248–256 ( digitized version ), here: p. 249, Utzschneider, possibly with the optician Joseph Niggl, undertook the first test fusions for optical glass in 1804 in Grafenaschau. Also Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - vision and reality of a new Bavaria ( contributions to the history of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version), p. 398, assumes that Utzschneider carried out his own melting tests before Guinand's appointment.

- ^ Ulrich Schiegg : Astronomical News from Bavaria. In Franz Xaver Freiherr von Zach (ed.): Monthly correspondence for the transport of the earth and sky customer (Gotha), Volume 12, October 1805, pp. 357–366, here: pp. 360 f. ( Digitized version ). Schiegg also claims in this article to have been the initiator of the Mathematical-Mechanical Institute.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr : Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft , Leipzig 1929, p. 95; see. Walther Zschokke: On the history of optical glass . In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde , Volume 42, Berlin 1922, pp. 208–215, here: p. 210 / note. 1.

- ^ Heinrich Zschokke : The Bavarian Stories 1. – 6. Book. 4 volumes, Sauerländer , Aarau 1813–1818, on Utzschneider cf. 6th book, pp. 132-137 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Polling , Rottenbuch and Steingaden . Cf. Peter Genner: After the end of monastery rule - Swiss revolutionaries in the Pfaffenwinkel . In: Der Welf , yearbook of the historical association Schongau - Stadt und Land 2013, pp. 69–192 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 36.

- ↑ Moritz von Rohr: P. L. Guinand's instruction on glass melting. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 48, Berlin 1928, pp. 438-453, 501-514, 548-559, 600-613, here: pp. 605-609.

- ↑ Joseph Kirmeier: research and production (...) In the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft (Ed.): Fraunhofer in Benediktbeuern. Glassworks and workshop . Munich 2008 ( digitized version), pp. 18–31, here: p. 19.

- ^ Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 291 f.

- ^ Leo Weber: Joseph von Utzschneider and Joseph von Fraunhofer (...) In Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft (ed.): Fraunhofer in Benediktbeuern. Glassworks and workshop . Munich 2008 ( digitized version), pp. 32–39, here: p. 32.

- ^ Hans-Peter Sang: Joseph von Fraunhofer, researcher, inventor, entrepreneur. Peter Glas, Munich 1987, p. 28 incl. Note 14 f.

- ↑ Réclamation de Mr. Aimé Guinand. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), 15th year, Sciences et arts, volume 43, Genève / Paris 1830, pp. 222–228, here: p. 224 ( digitized version ). The payment was made on September 1, 1805 in Neuchâtel . Guinand's employment contract of May 10, 1806 also states that he came to Benediktbeuern at Utzschneider's invitation (Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 14-20, here: pp. 14).

- ↑ Joseph von Utzschneider: Brief outline of the life story of Dr. Joseph von Fraunhofer (…) Rösl, Munich 1826, p. 5 f. ( Digitized version ); see. Pierre-Louis Guinand by Corbatiere ( sic ). 1748-1824. In Rudolf Wolf: Biographies on the cultural history of Switzerland. 2. Cyclus, Orell, Füssli & Comp. , Zurich 1859, pp. 299–308, here: p. 303 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ See redrawing with legend in Josef Kirmeier, Manfred Trend (Ed.): Gloss and End of the Old Monasteries. Secularization in the Bavarian Oberland 1803. House of Bavarian History , Munich 1991, ISBN 3-927233-12-9 , p. 348 f.

- ^ Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 10.

- ^ Hans-Peter Sang: Joseph von Fraunhofer, researcher, inventor, entrepreneur. Peter Glas, Munich 1987, p. 28 incl. Note 16.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 148.

- ^ Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 11-13.

- ^ Otto Paul Krätz, Elisabeth Renatus: On the history of the glassworks in Benediktbeuern . In: Kultur & Technik (Deutsches Museum München) 7/1983, pp. 248–256 ( digitized version ), here: p. 249. When the monasteries were secularized, their churches became parish churches.

- ↑ German by Moritz von Rohr: P. L. Guinand's instruction on glass melting. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 48, Berlin 1928, pp. 438-453, 501-514, 548-559, 600-613; see. the same: Pierre Louis Guinand, b. April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197.

- ↑ If Guinand's first wife was a widow almost twice as old, by the fourth marriage he was almost three times as old as the bride. Understandably, his relatives were not uplifted by the marriage, even if it remained childless. But Guinand wrote to his son-in-law Georges-Louis-Christophe Couleru in 1812: “I am very satisfied with my Rosalie and I hope I will satisfy her too.” Cf. Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197, here: p. 182 f.

- ↑ The secrecy made it easier that besides them in Benediktbeuern only Utzschneider spoke French.

- ^ French text from Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 14-20.

- ^ Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 302.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Pierre Louis Guinand, b. April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197, here: p. 191.

- ↑ According to the French text by Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 297.

- ↑ See Adolf Seitz: The Munich optician Josef Niggl. In: Central newspaper for optics and mechanics, electrical engineering and related professions, Volume 44, July 5, 1923, pp. 150–154.

- ↑ According to Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 27, on Georg Simon Klügel : Analytische Dioptrik . 2 parts, Johann Friederich Junius, Leipzig 1778 (1 + 2: digitized ).

- ^ Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 299.

- ↑ Fraunhofer to Utzschneider, January 26, 1809, quoted from Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, pp. 34–36, here: p. 35.

- ↑ See Moritz von Rohr: A newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928–1935, pp. 222–241, here: pp. 230, 232 incl. Fig. 4.

- ^ Johann Nepomuk von Reichel: Königlich-Baierisch-adelicher ladies calendar to the year 1809. Franz Seraph Hübschmann, Munich without year, p. 34 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Réclamation de Mr. Aimé Guinand. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), 15th year, Sciences et arts, volume 43, Genève / Paris 1830, pp. 222–228, here: p. 225 ( digitized version ).

- ^ According to Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 312 f., Utzschneider had appointed an (unnamed) woman “without any expertise” as managing director without the consent of his partners.

- ^ Joseph von Fraunhofer. In: Supplement to the Allgemeine Zeitung (Augsburg), 16. – 18. August 1826, pp. 909 f., 913 f., 917 f., Here: p. 913 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft , Leipzig 1929, p. 98.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: A newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928–1935, pp. 222–241, here: p. 229.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: A newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928–1935, pp. 222–241, here: p. 235.

- ↑ Quoted from Leonhard Jörg: Fraunhofer and his merits in optics (dissertation). J. G. Weiß, Munich 1859, p. 35 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Fraunhofer's relationship with his business partners Utzschneider and Reichenbach was also cool. (Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described from sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft , Leipzig 1929, p. 30.)

- ^ Guinand to Noël-Jean Lerebours, June 7, 1820, quoted by Paul Ditisheim : Le centenaire de Pierre-Louis Guinand. In: L'Astronomie: revue mensuelle d'astronomie, de météorologie et de physique du globe et bulletin de la Société astronomique de France (Paris) 39/1925, pp. 177-197, here: p. 186, cf. P. 188 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197, here: p. 193.

- ↑ See a newly found letter from P. L. Guinand. In: Research on the history of optics. 1. Volume, Springer, Berlin 1928-1935, pp. 222-241.

- ^ According to the French text of the contract of December 20, 1813 with Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. J. Springer, Berlin 1926, pp. 49-51.

- ^ Rudolf Wolf: Handbook of astronomy, its history and literature. 1st half volume, F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, p. 339 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Based on the French text of Guinand's undated answer to Utzschneider from Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer und seine optisches Institut. J. Springer, Berlin 1926, pp. 54–56, quote: p. 56.

- ↑ Guinand to his daughter Amélie Couleru, February 5, 1815, printed by Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197, here: p. 193.

- ^ Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 52 f.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 156.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 99, cf. P. 157.

- ↑ Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197, here: p. 193 f.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 100 f., Cf. P. 157; the same: A contribution to the history of optical glass. In: Nova Acta Leopoldina. New series, Volume 2, Halle an der Saale 1934 f., Pp. 147–202, here: p. 168 ff.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), Volume 25, Volume 9, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: p. 157 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Memoirs of Karl Heinrich Ritters von Lang (…) 2nd part, Friedrich Viehweg and Son, Braunschweig 1842, p. 221 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Rudolf Wolf: Notes on Switzerland. Cultural history (continued). In: Quarterly publication of the Natural Research Society in Zurich , 12/1867, pp. 218–220, 401 f. ( Digitized version ); Alto Brachner: History of Munich optics - origins, activities, observatories, locations. Spread 1750–1984. Dissertation at the Technical University of Munich 1986, pp. 338–344.

- ↑ Louis Thévenaz: Pierre Louis Guinand et sa famille. In: Musée Neuchâtelois (Neuchâtel) 11/1924 ( digitized version ), pp. 177–197, here: p. 196.

- ^ Joseph von Fraunhofer. In: Supplement to the Allgemeine Zeitung (Augsburg), 16. – 18. August 1826, pp. 909 f., 913 f., 917 f., Here: p. 917 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ See Johann Valentin Keller-Zschokke: A Swiss smelter for optical glass in Solothurn 1831–1857 and Theodor Daguet, manufacturer of optical glasses 1795–1870. Vogt-Schild, Solothurn 1826; Jean Risse: Théodore Daguet, fabricant de verres d'optique. In: Annales fribourgeoises ( Freiburg im Üechtland ) 14/1926, pp. 145–155 ( digitized version ); Michel Charrière: Daguet, Théodore. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- ↑ On July 21, 1801, the house of the Munich mirror maker and ornament grinder, Philipp Anton Weichselberger, collapsed and his apprentice Fraunhofer was buried. Elector Max Joseph took over the management of the rescue work. (Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described from sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 8 f.)

- ↑ See Myles W. Jackson: Spectrum of Belief. Joseph from Fraunhofer and the Craft of Precision Optics. MIT Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts) 2000, pp. 181-210.

- ↑ Cf. Joseph Fraunhofer: Determination of the refraction and color dispersal ability of different types of glass, in relation to the perfecting of achromatic telescope. In Ludwig Wilhelm Gilbert (ed.): Annalen der Physik (Leipzig), 56/1817, pp. 264-313 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Réclamation de Mr. Aimé Guinand. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), 15th year, Sciences et arts, volume 43, Genève / Paris 1830, pp. 222–228, pp. 227 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ See Larousse ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Moritz von Rohr: P. L. Guinand's instruction on glass melting. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 48, Berlin 1928, pp. 438-453, 501-514, 548-559, 600-613, here pp. 606-608.

- ↑ Fraunhofer mentions a "Ramouir furnace" in a letter from 1823. (Adolf Seitz: Joseph Fraunhofer and his optical institute. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg 1926, p. 41.)

- ^ Pastor and astronomer in Les Planchettes near Les Brenets.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), Volume 25, Volume 9, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: pp. 153–155 ( Digitized version ); Pierre-Louis Guinand by Corbatiere (sic). 1748-1824. In Rudolf Wolf: Biographies on the cultural history of Switzerland. 2. Cyclus, Orell, Füssli & Comp., Zurich 1859, pp. 299–308, here: pp. 305–307 ( digitized version ); Walther Zschokke: On the history of optical glass. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 42, Berlin 1922, pp. 208-215, here: p. 211; Hans Weil: La Sagne and his pioneers Daniel JeanRichard, Pierre-Louis Guinand and the Chronométrier and Régleur Paul Perret. Berlin 2014 ( digitized version), unpaginated.

- ^ Leonhard Jörg: Fraunhofer and its services to optics ( dissertation ). J. G. Weiß, Munich 1859, p. 19 ( digitized version ): “Fraunhofer invents homogeneous glass”.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Sang: Glass from the monastery. The Fraunhofer glassworks in Benediktbeuern. In: Culture & Technology (Deutsches Museum München) 17/1993, p. 28 f. ( Digitized version ); see. Ivo Schneider: Joseph von Utzschneider - vision and reality of a new Bavaria ( contributions to the history of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 429.

- ↑ Michael Faraday : The Bakerian Lecture - On the manufacture of Glass for optical purposes. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, year 1830, part 1, pp. 1–57 ( digitized version ), here: p. 2.

- ↑ Lens telescopes that competed with reflectors ( mirror telescopes ).

- ↑ As a foreigner and competitor of the glass manufacturer Aimé-Gabriel d'Artigues, who was a member of the jury in 1819 , Guinand was not mentioned.

- ↑ Edouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (…), Volume 25, Volume 9, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: pp. 152 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Rapport du jury central sur les produits de l'industrie française (…), Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1819, pp. 258–261 ( digitized version ); Rapport sur les produits de l'industrie française, présenté, au nom du jury central (…), Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1824, p. 325 f. ( Digitized version ). According to the Memoirs of the Astronomical Society of London, Volume 2, Baldwin, Cradock and Joy, London 1826, p. 509 ( digitized ), a committee of the Astronomical Society of London with John Herschel as a member had a lens performance of 6.8 English inch (17.3 cm) opening made by Charles Tulley in 1823 from Guinand flint glass, described as "in the highest degree satisfactory".

- ↑ Rapport sur les produits de l'industrie française, présenté, au nom du jury central (…), Imprimerie Royale, Paris 1828, p. 380 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Découverte d'un procédé régulier pour la fabrication du flint glass. In: Le Globe, Recueil philosophique, politique et littéraire (Paris), November 1, 1828, p. 798 ( digitized version ). According to Édouard Reynier: Notice sur feu M. Guinand, opticien. In: Bibliothèque universelle des sciences, belles-lettre et arts (...), 25th volume, 9th year, Sciences et arts, Genève / Paris 1824, pp. 142–158, 227–236, here: p. 152 ( digitized ), Pierre-Louis Guinand would have already made a flint glass pane 18 Paris inches (48.7 cm) in diameter.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: Joseph Fraunhofer's life, achievements and effectiveness, described according to sources. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig 1929, p. 98.

- ^ According to Ernst Voit: Feinmechanik in Bayern. In: Representations from the history of technology, industry and agriculture in Bavaria. R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1906, p. 169–195, here: p. 176 f., Of 95 glass melts carried out by Fraunhofer in 1811–1825, only 26 could be described as completely successful.

- ^ Werner Ort: Heinrich Zschokke (1771–1848). A biography. here + now, Baden 2013, ISBN 978-3-03919-273-1 , p. 507.

- ^ The workshops in Benediktbeurn. In Heinrich Zschokke : About the history of our time, born in 1817, Heinrich Remigius Sauerländer , Aarau, pp. 559-573 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Declaration of the royal. go. Rathes J. v. Utzschneider, against some statements in the Bibliothèque universelle and the Globe, about the production of flint glass . In: Supplement to the Allgemeine Zeitung ( Augsburg ), January 25, 1829, p. 99 f. ( Digitized version ); see. Moritz von Rohr: Pierre Louis Guinand. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197, here: p. 121.

- ↑ Cf. Ivo Schneider : Joseph von Utzschneider - Vision and Reality of a New Bavaria ( Contributions to the History of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences 3). Friedrich Pustet , Regensburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-7917-2630-4 ( digitized version ), p. 321.

- ↑ Report fait par MM. (Stanislas) Cloëz et (Victor) de Luynes (...) sur les verres d'optique, présentés par M. Charles Feil (...) In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale ( Paris), 3rd series, 4/1877, pp. 422–426, here: p. 425 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Compte rendu des séances de l'Académie des sciences (Paris). Volume 6, June 25, 1838, p. 922 ( digitized version ); Volume 7, August 13, 1838, p. 354 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Rapport sur le concours relatif à la fabrication du flint-glass et du crown-glass; par M. Payen. In: Bulletin de la Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale (Paris) 38/1839, p. 470–473, here: p. 472 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ See Johann Valentin Keller-Zschokke: A Swiss smelter for optical glass in Solothurn 1831–1857 and Theodor Daguet, manufacturer of optical glasses 1795–1870. Vogt-Schild, Solothurn 1926; Jean Risse: Théodore Daguet, fabricant de verres d'optique. In: Annales fribourgeoises ( Freiburg im Üechtland ) 14/1926, pp. 145–155 ( digitized version ). The operation was forced to close due to emissions from the Herzogenbuchsee – Biel railway line opened in 1857.

- ^ Moritz von Rohr: A contribution to the history of optical glass (up to the opening of the Jena glassworks). In: Nova Acta Leopoldina. New episode, volume 2, issue 1 f., Hall a. S. 1934, pp. 147–202, here: p. 171.

- ^ Rudolf Wolf: Handbook of astronomy, its history and literature. 1st half volume, F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, p. 339 f. ( Digitized version ); Paul Ditisheim: Le centenaire de Pierre-Louis Guinand. In: L'Astronomie: revue mensuelle d'astronomie, de météorologie et de physique du globe et bulletin de la Société astronomique de France (Paris) 39/1925, pp. 177–197, here: p. 193 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Rudolf Wolf: Handbook of astronomy, its history and literature. 1st half volume, F. Schulthess, Zurich 1890, p. 338 ( digitized version ).

- ^ "Family papers published with exemplary care" (Moritz von Rohr: Pierre Louis Guinand, born April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137 , 189-197, here: p. 189).

- ^ To the son Aimé Guinand, Benediktbeuern, October 29, 1812.

- ↑ Summarizes the statements made by the author in his earlier publications about Guinand.

- ^ "Quickly written report", which "cannot easily be used as a source for Guinand's work" (Moritz von Rohr: Pierre Louis Guinand, born April 20, 1748, died February 13, 1824. In: Zeitschrift für Instrumentenkunde. Volume 46, Berlin 1926, pp. 121-137, 189-197, here: p. 121).

- ↑ Does not treat Guinand according to its importance and hardly consults French-language literature.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Guinand, Pierre-Louis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Guinand, Pierre Louis |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss optician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 1748 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Corbatière, municipality of La Sagne |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 13, 1824 |

| Place of death | Les Brenets |