Shoshone National Forest

|

Shoshone National Forest

|

|

|

Bergkessel Cirque of the Towers in the high altitude of the national forest |

|

| location | Park , Fremont , Hot Springs , Sublette , and Teton Counties, Wyoming , USA |

| surface | 9,981.92 km² |

| Geographical location | 44 ° 28 ' N , 109 ° 37' W |

| Setup date | July 1, 1908 |

| administration | US Forest Service |

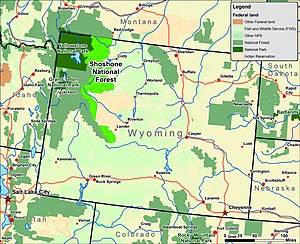

The Shoshone National Forest is one of the oldest national forests in the United States and covers an area of approximately 10,000 km² in the state of Wyoming . As the administrative unit of the federal government's forest holdings , the national forest serves primarily for economic use, which includes forestry , pasture use and the development of raw materials . The wooded area was originally part of the Yellowstone Timberland Reservation , which was established by law signed by President Benjamin Harrison in 1891 . Today there are also four wilderness areas in the national forest , which protect more than half of the area as wilderness from any human intervention. The unique diversity of ecosystems of the Shoshone National Forest ranges from sagebrush planes over dense fir - and spruce forests to rugged mountain peaks.

The forest area includes parts of the three major mountain ranges Absaroka Range , Beartooth Mountains and Wind River Range . The western border is formed by Yellowstone National Park . South of Yellowstone, the Continental Divide divides the forest from the neighboring Bridger-Teton National Forest to the west . Are private properties on the eastern border, the Bureau of Land Management managed land and the Wind River Indian Reservation of the Shoshone and Arapaho -Indianer. The border to the north is formed by the Custer National Forest along the border with Montana . South of the Shoshone National Forest runs the Oregon Trail with the South Pass , which immigrants used in the 19th century to pass through the rugged landscape. The national forest is part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem , which is a contiguous natural space of an estimated 81,000 km² .

geography

geology

The height of the national forest ranges from 1400 m at Cody to 4207 m at the top of Gannett Peak , an altitude difference of over 2800 m . The three main mountain ranges occurring in the national forest differ geologically from one another. All mountain ranges are part of the Rocky Mountains and are located in the transition between the central and northern part of the Rockies. The Absaroka Mountains were named after the Absarokee Indians, although they only inhabited the northernmost part of the mountain range. The main part of the Absaroka Mountains is located within the national forest, with Francs Peak as the highest peak at an altitude of 4009 m . The mountain range stretches north-south through the northern and eastern parts of the national forest and spans a length of 100 km from the Montana border to Dubois .

Major mountain passes through the Absarokas include the Sylvan Pass , which leads to the eastern entrance of Yellowstone National Park , and the Togwotee Pass , which provides access to Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park . The Union Pass is one of the traditional Indian traffic routes in the region on the western border of the national forest to the adjacent Bridger-Teton National Forest . The peaks of the Absaroka are of basaltic origin and were formed as a result of volcanic activity that occurred some fifty million years ago during the Eocene . The rock is relatively dark and consists of rhyolite , andesite and breccias . In terms of raw materials, there are some deposits of porphyry copper deposits , which also contain silver and some gold, but are of little economic importance. Due to the effects of erosion from glaciers and water and the relative softness of the rocks, the Absarokas have a fairly rugged appearance.

The Beartooth Mountains in the northernmost part of the forest were formed from instructive igneous rocks and metamorphic rocks . At 3.96 billion years old, some of the Precambrian rocks are among the oldest on Earth. Although the mountain range is often viewed as part of the Absarokas, it is different in appearance and geological history. The Beartooth Mountains rose about 70 million years ago during the Laramian orogeny and consist of extensive, wind-prone plateaus and rugged peaks with sometimes thin rocky cliffs. The rocks made of granite , gneiss and mica schist are rich in minerals such as chrome and platinum . In the entire mountain range iron and magnesium occur in biotites , amphiboles and pyroxenes . Quartz and feldspar are also common . Geologists suspect that the highest peaks of the Beartooth Mountains were once 6,100 m high, but were eroded to an average of 3,700 m in the following ten to a hundred million years .

The Wind River Range is located in the southern section of the national forest and is primarily composed of granite rocks, gneiss and mica schist. The mountain range has eight mountains that are higher than 4,100 m , including Gannett Peak, which is considered the highest peak in Wyoming. For a long time, the 4,189 m high Fremont Peak was thought to be the highest mountain in the Rocky Mountains, which, when viewed from the Oregon Trail, achieved a certain fame. It was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that the US geologist Thomas Bannon discovered that Gannett Peak, a little to the northwest, was significantly higher. In total, more than 230 mountains reach over the 3700 meter mark. The mountain range is also known to mountaineers from all over the world for its massive rocks and the variety of routes. The Cirque of the Towers in the Popo Agie Wilderness is one of the more popular climbing and hiking destinations, and there are an estimated 200 different climbing routes within the peaks around the mountain basin .

Hydrography

In the national forest there are a total of 500 mountain lakes and 4,000 km of flowing water. More than half of the lakes are in the Beartooth region. Some of these were left behind by the melting glaciers of the last ice age maximum , known as the Pinedale glacial period , which ended approximately 10,000 years ago. There are only a few lakes in the Absarokas, but here you can find the headwaters of the Yellowstone or Bighorn Rivers . In particular, the headwaters of the Shoshone and Greybull Rivers run across the eastern forest area. The water of some mountain lakes in the Wind River Range, however, feed the Wind River , which flows southeast through Dubois and flows into the Bighorn River at Riverton .

The Clarks Fork Yellowstone River is marked 35 km within the forest as a National Wild and Scenic River and has cliffs up to 610 m high. As the forest is on the eastern slopes of the continental divide, the waters flow towards the Atlantic basin .

glaciology

According to the US Forest Service, the Shoshone National Forest in the Rocky Mountains has the most individual glaciers among the national forests. The forest guide lists 16 named and 140 unnamed glaciers within the national forest, all of which are in the Wind River Range. 44 of these glaciers are located in the Fitzpatrick Wilderness and are spread around the highest mountain peaks. The Wyoming Water Board, on the other hand, lists only 63 glaciers for the entire Wind River Range, including areas outside the forest boundaries.

If one takes into account the growth of glaciers during the Little Ice Age from 1350 to 1850, the glaciers have shrunk by half worldwide since then. Much of the decline has been well documented through photographs and other data. There has also been an increase in the melting rate since the 1970s, which is likely closely related to global warming .

The behavior of the glaciers in the Shoshone National Forest fits this pattern well. After the first photographs were taken in the late 1890s, the area covered by the glaciers shrank noticeably in the following century. Scientific research between 1950 and 1999 has shown that glaciers have receded by a third during this time. Largest single glacier in the Rocky Mountains within the United States is the Gannett Glacier on the northeast slope of Gannett Peak, which is reported to have lost half of its volume since 1920. A quarter of that loss has occurred since 1980. One of the most widely studied glaciers in the Wind River Range is the Fremont Glacier . Scientists have researched ice cores from this glacier and detected changes in the atmosphere over the past 500 years.

Compared to the large ice sheets in Greenland and the Antarctic , the small glaciers in the forest are much less protected against the melting processes. As soon as a glacier begins to melt, it can run into an imbalance. Regardless of its size, it no longer manages to achieve a balanced mass balance , which leads to complete melting without an opposite climate change. Glaciologists predict that the rest of the forest's glaciers will disappear by 2020 if the current trend continues. The decline is already reducing the summer runoff, which supplies rivers and lakes with additional water, and which is a vital source of cold water for certain animal and plant species. The disappearance of the glaciers will therefore have a significant long-term impact on the national forest ecosystem.

climate

Wyoming is a relatively dry state with an average of 25 cm of precipitation per year . But the Shoshone National Forest is located in one of the most mountainous areas of the state, where even in the dry summer months glaciers and snowmelt provide the running waters with sufficient water. The average temperature in the lowlands is 22 ° C in summer and −7 ° C in winter. At higher peaks it is an average of −7 ° C all year round. Most of the precipitation falls in winter and early spring, while summer is interrupted by extremely windy afternoons and evening thunderstorms. The autumn is cool for ordinary and dry. Due to the altitude and dryness of the atmosphere, strong radiation cooling occurs throughout the year , with temperature differences of 28 ° C during the day are not unusual. As a result, nights can get quite cool in summer and extremely cold in winter .

Ecosystem

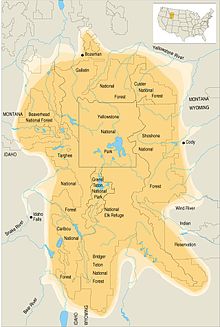

The Shoshone National Forest forms the eastern part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which is believed to be the last large, nearly intact ecosystem in the northern temperate zone of the earth. There are five other national forests in the ecosystem, which, together with the National Elk Refuge, are spread around Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Park . The ecosystem is primarily considered a retreat for the endangered grizzly. In the late 1990s, a successful wolf reintroduction program began that led to the immigration of the endangered gray wolf .

flora

The national forest has around 1,300 registered plant species. Sagittarius and grass-dominated types of vegetation grow in the low-lying areas, whereas different combinations of species are found on wooded areas. These include coastal pines , which can be found together with Rocky Mountain junipers , Douglas firs and trembling poplars at heights of up to 2,700 m. At higher altitudes are up to the tree line subalpine fir , Engelmann spruce , white pine ethnic and Flexible pines spread. Riparian forests , balsam poplar and willow trees usually dominate in the lower areas . Numerous plant species are endemic to the region. There are rock florets , bladder pods , shoshonea, and North Fork Easter daisies , among others , which have bright white and yellow petals during spring and summer.

Exotic species accidentally introduced by tourists can usually be found near roads and campsites. The United States Forest Service tries to identify and contain the proliferation of non-native plants through species control. A major problem is the mountain pine beetle , which is known to infest dense pine and fir forests. In the event of severe infestation, the beetle can destroy huge areas of forest, increasing the risk of forest fires and soil erosion. Although mountain pine beetle epidemics have been passed down since the beginning of the 20th century, the frequency and intensity of the outbreaks has increased. A connection with global warming is assumed.

fauna

Virtually all fifty known mammal species that existed before white colonization are still present in the Shoshone National Forest .

The native bear species include the grizzly and the American black bear . There are approximately 125 grizzly bears in the national forest and in the surrounding nature reserves. The grizzly is an endangered species for which the forest is one of the last refuge areas. In order to catch so-called "problem bears" and lead them back to more remote areas, traps have been set in many places. The captured bears are anesthetized and identified with a registered ear tag . In the event of repeated attacks, a bear can thus be better identified and, in extreme cases, killed. Federal grizzly recovery and conservation efforts have often resulted in disputes with local landowners and surrounding communities. The American black bear, which is smaller and less aggressive, causes fewer problems. Its population in the forest is estimated at 500 copies.

A management program across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem seeks to both increase human safety and protect the bear habitat. Visitors are asked to keep their food in vehicles or in steel containers provided for this purpose . In the developed areas of the forest there are also bear-proof garbage containers, in other places the waste has to be stored away from the campsites.

The main carnivorous inhabitants of the national forest include puma and gray wolf. The exact number of pumas, which are nocturnal and rarely seen, is unknown, but numerous tracks indicate a widespread distribution. The wolf immigrated from Yellowstone National Park , but is rarely found in the forest. Since it is an endangered species, one hopes for an increase in the wolf population over time. There are also bear marten , coyotes , bobcats , weasels , real martens and ferrets . In addition, beavers , marmots , whistles , raccoons and badgers can be found throughout the National Forest .

The American elk is one of the typical native herbivores, and is found in small herds near the water, especially at lower altitudes. Other frequently observed mammals are elk , mule deer and pronghorn , but there are also smaller bison populations. Cliffs and mountain slopes are of bighorn sheep and mountain goats inhabited. During the winter, the largest herd of bighorn sheep in the US American part of the Rocky Mountains can be seen on Whiskey Mountain a few kilometers south of Dubois , even if the population has declined sharply since the 1990s due to disease and hunting by coyotes.

The national forest is populated by up to 300 different bird species. Bald eagles and golden eagles can be found near watercourses . More commonly, Peregrine Falcon , Merlin and owl . Black-billed macaws and pine jays can be seen on campsites and by lakes . Occasionally you can see the trumpeter swan near the lake or river , but this is very rare. Other special bird species are great blue herons , rhinoceros pelican and Canada goose . Pheasant , mugwort and turkey live in the mugwort plains .

There are a total of eight species of trout in the waters of the National Forest , of which the Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout is the only one native to Wyoming . This trout is only found in the forest and neighboring parks and is one of four subspecies of the cutthroat trout. Other fish caught are arctic grayling , mountain whitefish and paddle sturgeon .

The poisonous prairie rattlesnake can be found in the lower elevation , but also other reptiles such as the western ornamental tortoise and the ornamental box turtle . Some amphibians such as the spotted Columbia frog , the tiger salamander and the polar toad are relatively common . In spring and summer visitors mosquitoes and black flies right plaghaft that are extremely aggressive, especially in the high mountains.

wilderness

The forest comprises four untouched wilderness areas that are free from mining, deforestation, road and building construction and, as strictly protected nature reserves, are not allowed to be used with motorized vehicles or bicycles. The four areas have a total area of 6000 km² and consist of the North Absaroka , Washakie , Fitzpatrick and Popo Agie Wilderness . A small part of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness extends into the extreme northwestern part of the national forest along the border with Montana .

history

The Shoshone National Forest was named after the Shoshone . As recent research shows, they lived in this area for much longer than the other Indians who only came in from the 18th century, such as the Absarokee (before 1804) and the Northern Cheyenne (since the 1830s). According to archaeological traces, the first Indians settled in this area more than 8,000 years ago. They lived in small, extremely mobile kin groups. One group, the Tukudika or Sheep Eaters , may have been the oldest tangible indigenous population. The Tukudika lived mainly on the animals that gave them their food, hunted in the company of large dogs with highly developed bows, and built easily transportable sheds. In contrast to the Great Plains in the east, the forest offered sufficient wood, food and shelter during the winter months. One of the main sources for historical research is the stones that held the walls of the tipis to the ground and that were left behind when residents moved on. Of these circular remains, around 3000 are known, but only about 35 are dated. The oldest go back to around 1600. Since 2005, starting from Bighorn Canyon, research has been going on.

Parts of the mountainous regions were visited by Shoshone and Sioux for spiritual healing and vision journeys . In 1840 Chief Washakie became leader of the Eastern Shoshone and in 1868 negotiated with the US government to protect an area of 8,900 km² on the area of what is now the Wind River Indian Reservation as tribal land. Before the reserve was established, the US cavalry built Fort Brown on the reserve land , which was later renamed Fort Washakie and which is now east of the tree line. The fort was run by Buffalo Soldiers , African American cavalry members, in the late 19th century . Chief Washakie was buried in the fort as part of an official funeral ceremony. It is rumored that the Shoshone woman Sacajawea , who provided valuable assistance to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on the Lewis and Clark expedition , would also be buried here. However, it turns out that her present burial site is much further east.

In the early 19th century, mountain men like John Colter and Jim Bridger explored the wooded area. Colter was the first white man to travel to the Yellowstone region and the forest to the east between 1806 and 1808. As an original member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, he asked Meriwether Lewis' permission to leave the expedition after crossing the Rocky Mountains on their way back from the Pacific Ocean . Colter was accompanied by the two independent fur hunters Joseph Dixon and Forrest Hancock , whom the expedition had encountered earlier, but then decided to leave his new partner and continue the explorations further south on their own. Colter first traveled to the northeast region of what is now Yellowstone National Park. He then explored the Absaroka Mountains , crossed the Togwotee Pass and entered the Jackson Hole Valley . He survived a grizzly bear attack and was pursued by a group of Blackfoot Indians who stole his horse. Colter later provided his expedition commander William Clark with previously unknown information about the regions he had explored, which Clark published in 1814.

Journeys by fur traders and adventurers such as Manuel Lisa and Jim Bridger from 1807 to 1840 completed the exploration of the region. With the decline of the fur and beaver trade in the late 1840s, sometimes because the beaver population was now exhausted, there were few white explorers who invaded the forest area in the decades that followed. Expeditions led by Ferdinand V. Hayden in 1871 were the first to be funded and supported by the government. Hayden was primarily interested in documenting the Yellowstone lands west of the forest, but his expedition found that the forest was an important resource that needed to be protected from sprawl and conversion into farmland. Trips to the forest area of General Philip Sheridan as well as of the later US President Theodore Roosevelt in the 1880s, who was a strong advocate for the US conservation movement , gave the impetus for the subsequently established Yellowstone Timberland Reserve in 1891, which was used to create the first National Forest in the USA.

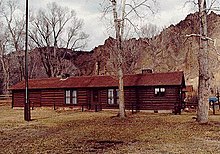

In 1902, President Roosevelt had the reservation expanded considerably, dividing it into four separate areas, the Shoshone being the largest. With the establishment of the United States Forest Service in 1905, the reserve was classified as a National Forest , but the current name was only introduced forty years later in 1945. A holdover from the early years of forest management is the Wapiti Ranger Station , built in 1903 and located to the west of Cody . It is considered the oldest surviving ranger station in a national forest and is now classified as a National Historic Landmark .

In the last decade of the 19th century, mineral resources such as gold were mined, but only with moderate success. The last mine was abandoned in 1907, the washing of gold but today still allowed in many areas of the forest, in most cases even without permission. After the end of the mining era , the Civilian Conservation Corps set up numerous camps to combat unemployment during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The camps were used to house unemployed men paid by the federal government to build roads, trails, and campsites for future visitors to the Yellowstone region. After the end of the Second World War , the number of visitors increased as the infrastructure and access to the region continued to improve.

use

Forest management

The Shoshone National Forest is administered by the Forest Service , an agency within the Department of Agriculture . The forest is divided into five districts and in 2010 employed 145 people. The annual administrative budget is approximately $ 15,000,000 , much of which consists of public grants.

The main office is located in Cody , along with a visitor center , and a smaller information center is located in Lander . There are also local ranger offices in Cody, Dubois and Lander.

As in other national forests in the USA, the management of the Shoshone National Forest is subject to sustainability criteria in order to ensure the supply of raw materials such as lumber or wood pulp for paper production. In addition, is degradation of natural resources and the exploration and production of oil and natural gas powered, although this has become less common in the Shoshone National Forest because of a conservation agreement. Common than logging and mining is the leasing of pastures for cattle and sheep to ranchers . The forest creates guidelines and environmental requirements to ensure that there is no excessive exploitation of raw materials and that necessary consumer goods are also available for future generations, although some nature conservation organizations have expressed concerns about the lease program. In particular, cattle overgrazing appears to be a major problem.

Due to the commitment of environmentalists and increasing public interest, wilderness areas were established from 1964 onwards , which are under significantly higher protection and forbid any interference with nature. In the Shoshone National Forest, less than ten percent of the total area is currently used for land leasing, logging or mineral extraction. The rest of the forest is either designated as wilderness, temporarily reserved as a protected habitat for plants and animals in the interests of sustainable management, or is used for recreation and recreational use by visitors.

In recent years, the forest administration has faced a variety of problems. One point of contention is overgrazing by cattle on floodplains and on areas for which there is no lease agreement. Lobby associations are looking for new oil and gas deposits and try to penetrate into regions whose flora and fauna could be endangered. Plans to build new roads to facilitate the transport of raw timber have been sharply criticized and are inconsistent with current legislation prohibiting such constructions. Another problem remains the illegal off-road driving of ATVs and snowmobiles , especially in wilderness areas. Occasionally, protecting endangered and endangered species such as the grizzly bear and wolf is contrary to the interests of some ranchers.

Fire ecology

The Shoshone National Forest has an ongoing fire management program that understands forest fires as a natural part of the ecosystem. In the past, forest fire fighting measures have always consisted of putting out all fires, even small ones, as quickly as possible, which over the years has resulted in an accumulation of dead wood and dry leaves. After the devastating fires in the Yellowstone region in 1988 , the forest fire hazard of individual areas was examined more closely. To minimize the chances of another wildfire disaster, a system for fire control, fuel management and a controlled fire plan was developed in collaboration with the National Interagency Fire Center , an interagency facility, and local landowners .

Seventy percent of all forest fires are caused by lightning strikes, caused by high-energy, low-moisture thunderstorms that usually occur in midsummer. The remaining portion comes from neglected campfires and other human carelessness. In the case of artificially caused fires, immediate extinguishing is mandatory, unless these were deliberately placed in accordance with the fire management plan. Every year there is an average of 25 fires, larger fires with over 4 km² usually every three years. 2003 was a record year with fifty fires, five of which covered an area of over 4 km².

In summer the national forest maintains its own fire brigade team. Five fire engines and an on-call helicopter are available for use. Furthermore, you have access to a regional base that offers fire jumpers and fire-fighting aircraft. In the event of major fires, it is possible to request further assistance from the National Interagency Fire Command .

freetime and recreation

The Shoshone National Forest has an average of half a million visitors a year. Two visitor centers offer instructions, books, maps and display boards and are staffed either by nature and landscape guides or by volunteers from the Forest Service. On the Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway west of Cody is the Wapiti Wayside , not far from the historic Wapiti Ranger Station . The other visitor center is in southern Lander . In the forest there are thirty campsites accessible to cars with up to 27 individual parking spaces. About half of the tent sites have drinking water, sanitary facilities and disabled access. On the developed, so-called "Front Country" campsites, access for mobile homes is mostly provided. Most campsites, with the exception of the Rex Hale campsite, cannot be reserved. Some only allow hard-sided camping in sheltered mobile homes because of the grizzly bears.

More remote areas that are not developed can only be reached by visitors via hiking trails on foot or on horseback. The hiking trails in the protected area cover a total length of more than 2,400 km. As one of the larger, the Continental Divide Trail leads through the area, which follows smaller hiking trails on some sections. In the northern region of the national forest runs the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and the Beartooth Loop National Recreation Trail . Most of the starting points offer enough space for horse and pack animal hikers. Quads are permitted along the access roads to the forest, but their use should be restricted in large parts of the forest.

Leisure activities in the national forest include hunting and fishing, for which permits are required and special regulations apply. In order to protect certain animal species from overhunting and to improve personal safety, new hunting rules are drawn up every year. Many of the streams and rivers are marked as Blue Ribbon Trout Streams , making them ideal for fishing enthusiasts. In total, fishing is allowed in 500 lakes and 2,700 km of rivers. Hunting and fishing licenses are issued by the state of Wyoming and can be obtained from the Fish and Game Department.

The southern portion of the forest in the Wind River Range is a popular mountaineering destination as it is home to 29 of Wyoming's thirty highest peaks. The mountains consist mainly of granite rocks with countless cliffs and sheer rock walls. This is especially true for the Cirque of the Towers, which has numerous peaks next to each other.

In winter, cross-country skiing and snowmobiling are widespread and are the only motorized means of transport at this time, as many roads are closed until well into May. The Continental Divide Snowmobile Trail , accessible from the Togwotee Pass , runs through the area . With up to twelve meters of snow a year in the higher elevations, the snowmobile season usually lasts from the beginning of December to mid-April. Important focal points Lander (Wyoming) , Cody and Togwotee Pass. Snowmobile equipment can be borrowed from outfitters who also offer guided tours for beginners. There are also motels that provide accommodation and food. In recent years, the use of snowmobiles has continued to increase and has been somewhat restricted within Yellowstone National Park.

National Scenic Byways

As the eastern entrance to Yellowstone National Park, the national forest has several National Scenic Byways . The as All-American Road excellent Beartooth Highway ( US Route 212 ) leads through the forest area and serves as the northeast entrance to Yellowstone. Immediately south of the Beartooth Highway, the Chief Joseph Scenic Byway ( Wyoming Highway 296 ) follows the trail on which Chief Joseph and the Nez Percé tribe attempted to flee from the U.S. cavalry in 1877 . To the south of this, the Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway (US 14/16/20) runs from Cody in a westerly direction to the Sylvan Pass , where it leads into Yellowstone Park. The Wyoming Centennial Scenic Byway (US 26/287) leads from Dubois over the Togwotee Pass to Jackson Hole and the Grand Teton National Park .

literature

- Elbert L. Little: National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Western Edition . Knopf Publishing Group, New York, NY, 1980, ISBN 0-394-50761-4 .

- William J. Fritz: Roadside Geology of the Yellowstone Country . Mountain Press Publishing Company, Missoula, 1985, ISBN 0-87842-170-X .

- Rebecca Woods: Walking the Winds: A Hiking and Fishing Guide to Wyoming's Wind River Range . White Willow Publishing, Jackson WY, 1994, ISBN 0-9642423-0-3 .

- John O. Whitaker, National Audubon Society Staff: National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals . Knopf Publishing Group, New York, NY, 1996, ISBN 0-679-44631-1 .

- Robert Marshall M. Utley: After Lewis and Clark: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific . Bison Books, Univ. of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE, 2004, ISBN 0-8032-9564-2 .

- Jim Menlove: Forest Resources of the Shoshone National Forest. Ogden, Utah, 2008 ( online , PDF, 1.5 MiB).

Web links

- Official website (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Shoshone National Forest. Retrieved March 3, 2011 .

- ^ US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior: Absaroka Mountains. (No longer available online.) In: America's Volcanic Past. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013 ; accessed on March 29, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Wyoming State Geological Survey: Wyoming Geology - Absaroka Mountains. Retrieved July 27, 2011 .

- ^ Yellowstone-Bighorn Research Association: Introduction to the Precambrian. (No longer available online.) In: Local Geology. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011 ; accessed on March 29, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Selected Peaks of Greater Yellowstone. (PDF; 123 kB) (No longer available online.) P. 298 , archived from the original on November 18, 2008 ; accessed on September 5, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Shoshone National Forest, Lakes and Reservoirs. In: Shoshone National Forest Fishing. Archived from the original on May 20, 2009 ; accessed on March 30, 2011 (English).

- ^ US Forest Service, USDA: Shoshone National Forest Recreation Guide . United States Government Printing Office , 2003, OCLC 51128703 .

- ^ A b Harold J Hutson: Wyoming State Water Plan. Retrieved March 30, 2011 .

- ^ Wyoming Outdoor Council: Vanishing Glaciers in the Wind River Range. Archived from the original on March 2, 2004 ; accessed on March 30, 2011 (English).

- ↑ Larry Pochop, Richard Marston, Greg Kerr, David Veryzer, Marjorie Varuska and Robert Jacobel: Glacial Icemelt in the Wind River Range, Wyoming. In: Water Resources Data System Library. Retrieved March 30, 2011 .

- ↑ Cat Urbigkit: Glaciers shrinking. Sublette Examiner, September 1, 2005, accessed March 30, 2011 .

- ↑ Michael Reddy: Upper Fremont Glacier. In: Aqueous Crystal Growth and Dissolution Kinetics of Earth Surface Materials. US Geological Survey, archived from the original on February 12, 2007 ; accessed on March 30, 2011 (English).

- ↑ MM Reddy, DL Naftz, PF Schuster: Ice-Core Evidence of Rapid Climate Shift during the Termination of the Little Ice Age. US Geological Survey, archived from the original on December 20, 2005 ; accessed on March 30, 2011 (English).

- ↑ Mauri S. Pelto (Nichols College): The Disequilbrium of North Cascade, Washington Glaciers 1984-2004. Retrieved March 30, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Wyoming Climate Atlas. University of Wyoming, archived from the original December 30, 2006 ; accessed on March 31, 2011 (English).

- ↑ Wyoming Official State Travel Website: Wyoming's Weather and Climate. Archived from the original on September 12, 2006 ; accessed on March 31, 2011 (English).

- ↑ US Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center: Rare Plants of Shoshone National Forest (USFS R-2). (No longer available online.) In: Wyoming Rare Plant Field Guide, US Forest Service Rare Plant List. Archived from the original on December 8, 2005 ; accessed on March 12, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Shoshone National Forest Planning Staff: Draft, Forest Plan Comprehensive Evaluation Report. (PDF) Archived from the original on March 26, 2009 ; accessed on March 12, 2011 .

- ^ US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Forest Works to Counter Carter Mountain Threats. Archived from the original on May 20, 2009 ; accessed on March 12, 2011 .

- ↑ Carolyn B. Meyer, Dennis H. Knight, and Gregory K. Dillon: Historic Variability for the Upland Vegetation of the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming. Online manuscript dated December 12, 2006 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 597 kB), p. 75.

- ↑ a b Bears Outlawed in Wyoming Counties Over Food Fight. Environmental News Service, accessed March 11, 2011 .

- ^ US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Shoshone National Forest Bear Information. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009 ; accessed on March 25, 2011 (English).

- ↑ National Bighorn Sheep Interpretive Center: Estimated Whiskey Mountain Bighorn Sheep Population. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009 ; accessed on March 14, 2011 (English).

- ^ Judson B. Finley, Chris C. Finley: The Boulder Ridge Archaeological Inventory: A Late Prehistoric / Early Historic Shoshone Landscape in Northwestern Wyoming , Northwest College Department of Anthropology Technical Report Series Number 1a. A Report prepared for the USDA Shoshone National Forest, Cody, Wyoming 2004.

- ^ Native Peoples. In: Yellowstone, America's Sacred Wilderness. PBS, accessed March 5, 2011 .

- ↑ Lawrence L. Loendorf, Nancy Medaris Stone: Mountain spirit. The Sheep Eater Indians of Yellowstone , University of Utah Press, 2006.

- ↑ Archaeological Field School - Wyoming Northwest College, Summer 2010 ( Memento of the original from May 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Wind River Country, Wyoming: The History of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe. In: Eastern Shoshone Tribe, Wind River Indian Reservation. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008 ; accessed on March 5, 2011 .

- ^ Burial Sites. In: The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery. Retrieved March 5, 2011 .

- ^ Robert Marshall M. Utley: After Lewis and Clark: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific . Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press , Lincoln, NE 2004, ISBN 0-8032-9564-2 .

- ↑ Ken Burns: Private John Colter. In: Lewis and Clark, The Journey of the Corps of Discovery. PBS, accessed March 5, 2011 .

- ^ Aubrey L. Haines: The Yellowstone Story . Revised. tape 2 . University Press of Colorado, 1977, ISBN 0-87081-391-9 , chap. 14 , p. 94 .

- ↑ Wapiti Ranger Station. (No longer available online.) In: National Historic Landmarks Program. National Park Service, archived from the original on May 20, 2009 ; accessed on March 6, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ USFS Ranger Districts by State (PDF; 207 kB)

- ^ Beartooth Front, Wyoming. (No longer available online.) Wilderness Society, archived from the original on February 2, 2014 ; accessed on March 7, 2011 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Wyoming Outdoor Council: Setbacks on the Shoshone National Forest. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006 ; accessed on March 11, 2011 (English).

- ↑ Wyoming Outdoor Council: Shoshone National Forest Pulls Timber Sale. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006 ; accessed on March 11, 2011 (English).

- ↑ a b c U.S. Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Wildland Fire Management. Archived from the original on June 23, 2006 ; accessed on March 28, 2011 (English).

- ^ US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture: Planning Revision. (PDF) Archived from the original on May 24, 2006 ; accessed on March 31, 2011 .

- ^ Continental Divide trail Alliance: Continental Divide National Scenic trail. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 10, 2011 ; accessed on April 1, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Shoshone National Forest plan revision team: Shoshone National Forest - Need for Change Evaluation. (PDF; 543 kB) September 2005, p. 22 , accessed on August 25, 2011 (English).

- ↑ Wyoming Game and Fish: Wyoming Game and Fish Home. Retrieved April 1, 2011 .

- ^ Federal Highway Administration, US Department of Transportation: Explore Wyoming. In: America's Byways. Retrieved June 1, 2011 .