Tri martolod

Tri martolod ( Breton "three sailors") is a Breton folk song . The lyricist and composer of the melody are not known; the song, which is occasionally called Tri martolod yaouank (Three Young Sailors), was probably written in the 18th century. The oldest printed version, as far as is known, dates from 1809. In the song collection Sonioù Pobl (Sounds of the People) published in 1968 by Polig Monjarret , a pioneer of the return to Breton identity and culture, it was called An tri-ugent martolod (The sixty sailors) . This song was also danced to all over Brittany . Under the title Les trois marins de Nantes (The three sailors from Nantes) it was also distributed in a French-language version, although it is not known which of the two language versions is the original.

Alan Stivell has Tri Martolod 1972 with new arrangements provided sung as vinyl - Single on Fontana with the B-side of The King of the Fairies published. The song is also included on his commercially successful LP Alan Stivell à l'Olympia in a version that is also around three and a half minutes long. The concert at Olympia on February 28, 1972 was also broadcast live on Europe 1 . Stivell's following single, Pop-Plinn , one of the first “Bretonenrock” (Brezhoneg Raok) titles , sold better than this traditional in record stores , but Tri martolod developed into one alongside the unofficial national anthem Bro gozh ma zadoù in the following decades of the most important identity-creating songs in Breton music .

Since the beginning of the “ Breton Renaissance ” at the end of the 1960s, the song has been remembered by the general public at concerts and through recordings, in particular by Tri Yann and Nolwenn Leroy and a large number of other performers. Stivell has also performed it regularly throughout his career, often with different arrangements. It has since been translated into numerous other languages and recorded in different styles. So sing Santiano it in a mixture of German and Breton verses , Manau has the melody in his hip-hop - million hit La tribu de Dana incorporated and the Swiss band Eluveitie a folk metal published version.

The text

Form and action

The longest surviving version of the song consists of 20 stanzas . They consist of a two-line couplet and a two-line refrain , in which the last part of the second line of verse is repeated twice . At the end of each first line there is a long warbling with no lexical meaning (tra la la…) , after the first line of the chorus a brief exclamation (gê!) . In this respect, each of these quatrains only has a brief piece of information - for example, “Three young sailors set out on their journey” - which is already formulated in full in the second line. This form of song corresponds to the traditional Kan ha diskan , meaning “song and answer”, in which there is an alternating song between two, more rarely three singers. In contrast to the related form-building principle of call and response , the speakers are of equal importance because both dictate the pace and rhythm of the dancers.

In almost all historical variants of the song (see below ) there is an identical metric in the stanzas with 13 feet , seven of them in the chorus.

The text begins with a description of an Atlantic voyage by three young sailors to North America and from the fifth stanza develops into a dialogue between two people who both live in poor conditions . At this transition the narrative perspective also changes ; the uninvolved narrator ( authorial situation ) is replaced by a direct conversation between one of the sailors - the other two no longer appear in the sequence - and a woman whom he meets after docking . It quickly turns out that the two not only know each other from France , but also promised marriage there and had even looked at wedding rings together in Nantes . However, both were penniless so that they could not keep the promise. Because of what circumstances they were separated at the time, the song does not answer the question of what the woman ended up "across the pond".

At this point in the song, with the eighth stanza, the tense changes from past tense to future tense ( futur simple ) - so the couple are talking about what they are going to do from now on. The woman describes their two material situations in detail and vividly: “We have no house and no stalk [symbolic of a field], not even a bed, neither sheets, blankets, nor pillows. We are missing a bowl and spoon and everything we can bake bread from ” (Nous n'avons ni maison ni paille, ni lit pour dormir la nuit, […] ni drap ni couverture ni édredon sous la tête, […] ni écuelle ni cuiller. […] Ni de quoi faire du pain) . He counters that they should simply take nature as their model: “We do it like the partridge and sleep on the ground; and like the snipe we get up at sunrise ” (Nous ferons comme la perdrix: nous dormirons sur la terre. Nous ferons comme la bécasse: quand le soleil se lève elle va courir) . With the subsequent declaration that his song is now over, but "continue it if you can", he leaves it open whether skeptical reason or naive love will prevail and the couple's relationship this time will be continued. This open ending also made it possible to extend the duration of the dance by adding more stanzas.

Alan Stivell's 1972 version

Alan Stivell only used the first six stanzas in his early recordings (see the Breton text and the German translation below); other versions like that of Tri Yann are longer. That the main part of the plot with its surprising twist remained hidden from them in the early 1970s should only have become aware of the fact that the number of French people who at least passively spoke the Breton language was extremely small at the time . Their use was only "revived" by the return to the independent Breton culture initiated by Stivell and others. Regardless of this, "bands and orchestras even in [ Pyrenees places like] Tarbes and Pau were soon adding pieces like Tri martolod [...] to their repertoire".

Two thematic aspects of this song were not entirely unfamiliar to the singer personally. In 1970 he had already published a piece entitled Je suis né au milieu de la mer about the poverty of sailor families on his LP Reflets . And the migration of Bretons from their homeland had affected his own family too; Both his father's grandparents, who worked in agriculture, and later one of their sons, Alan's father, had moved from the Morbihan to Paris , where they hoped for a better livelihood.

During Stivell's concert at Olympia something happened that was absolutely unusual in the venerable music theater: parts of the audience got up and began to dance to the piece between the rows of chairs. This was to be repeated a year later at an appearance in the Bobino . Allmusic explains this with the words, "the emotional vibrations during the entire performance [are] consistently attractive, far beyond the [rational] perceptible musical qualities". The artist himself, who initially only selected the song as one of several Breton songs for his Olympic appearance in 1972, said in retrospect in 2012 that this song was “not an emblematic rock song; maybe that's what the audience liked so much. ”In fact, around 150,000 copies of the long-playing record were sold in the first year after it was released, and around 50,000 more in the years that followed. Numbers for the single are not given in the literature used.

Tri martolod yaouank tra la la la la la la la la la

Tri martolod yaouank o voned da veajiñ

O voned da veajiñ, gê!

O voned da veajiñ.

Gant 'n avel bet kaset tra la la…

Gant' n avel bet kaset betek to Douar Nevez

Betek to Douar Nevez, gê!

Betek to Douar Nevez.

E-kichen my ar veilh tra la la…

E-kichen my ar veilh o deus mouilhet o eorioù

O deus mouilhet o eorioù, gê!

O deus mouilhet o eorioù.

Hag e-barzh ar veilh-se tra la la…

Hag e-barzh ar veilh-se e oa ur servijourez

E oa ur servijourez, gê!

E oa ur servijourez.

Hag e c'houlenn ganin tra la la…

Hag e c'houlenn ganin pelec'h 'n eus graet konesañs

Pelec'h' n eus graet konesañs, gê!

Pelec'h 'n eus graet konesañs.

E Naoned er marc'had tra la la…

E Naoned er marc'had hor boa choazet ur walenn

Hor boa choazet ur walenn, gê!

Hor boa choazet ur walenn.

Three young sailors, tra la la…

Three young sailors set off on the trip

Set off on the trip, hey ho!

Set out on the journey

Supported by the winds, tra la la ...

Supported by the winds to the New World

To the New World, hey ho!

To the New World.

Near a millstone, tra la la…

Near a millstone, they dropped the anchor.

They dropped the anchor, hey ho!

They dropped the anchor.

And in the mill, tra la la…

And in the mill, there was a maid

There was a maid, hey ho!

There was a maid.

And she asks me, tra la la…

And she asks me how we know each other

How we know each other, hey ho!

How do we know each other.

At the Nantes market, tra la la…

We had chosen a wedding ring at the Nantes market.

Had we chosen a wedding ring, hey ho!

We had chosen a wedding ring.

Social background

The fictional plot of the song takes place very realistically against the socio-historical background of its protagonists . The life of the Breton deep-sea fishermen - such could have been the case with the three sailors, but the living conditions were not fundamentally better even for ordinary seamen in the merchant shipping - was anything but romantic . The French Revolution of 1789 did little to change this for the physical workers from the Third Estate . The fleets fished large parts of the North Atlantic as far as Newfoundland ( Douar Nevez , in French Terre-Neuve , literally translated "New World" - see the second verse above) off the Canadian coast. Since the 17th century these waters have been the main fishing grounds for Breton cod fishermen ; from the 19th century the sea area around Iceland was added. During the fishing season, the teams carried out their work under the toughest and often life-threatening conditions, as described by Pierre Loti in his 1886 novel Pêcheur d'Islande ("Icelandic Fisherman").

When the men returned to their hometowns after a few months on the high seas, apart from occasional repairs to the schooners (goélettes) or other handyman services , they had to live on their small wages or the share of the catches until next spring . Due to the inadequate supply of food, there were repeated uprisings, for example in 1787 in Paimpol and other Breton port cities where the fishing fleets were stationed.

These circumstances did not change until the 19th century, and then only in parts of Brittany. For example, individual families on the northeastern coastline around Saint-Malo acquired a small piece of land that their wives and children worked while the "Newfoundlanders" (terre-neuvas) were on the move ; Joël Cornette describes these families as "seafarers" (marins-paysans) . The fish processing (preservation, packaging) began to develop in 1796 - and then focus on the southwestern coast of Brittany, between Douarnenez and Nantes - to an extent that many additional job opportunities not only for men but also for women and girls as young as twelve years created.

According to Monnier and Cassard , permanent employment as a maid in agriculture and especially as a maid (domestique) in the households of the small nobility and the urban bourgeoisie was highly sought after because there they - “albeit at the price of unlimited working hours and virtually nonexistent personal Freedom “- they received board and lodging as well as a certain protection from their masters. However, there were no more than 8,000 such jobs in Brittany in the 18th century, which is why some young women were driven to other parts of France or abroad in the hope of permanent employment and an adequate life.

In addition, unlike other parts of the kingdom , Brittany in particular was affected by a permanent economic crisis from 1740 to the 1780s , caused by frequent, climate-related crop failures, rural exodus , several epidemic waves ( smallpox , typhus , dysentery ), above-average mortality , price increases for staple food, consequences of war ( Seven Years of War and American Revolutionary War ), British coastal blockades and others. Joël Cornette calls the 18th the “dark, black century” of Breton history. In addition, in the 1780s there was an increasing concentration of the cod fishing fleets and their landings in Saint-Malo and the Bay of Saint-Brieuc , which was at the expense of the ports in the predominantly Breton-speaking Lower Brittany. In this respect, Tri martolod in no way exaggerates the couple's situation, and the people who heard the song or danced to it were well aware of this. Because it was her own life situation and that of her relatives and friends.

Music, dance and instrumentation

According to Pascal Lamour, who has been an award-winning Breton musician and arranger himself for decades, musicologists often have difficulties noting the melody adequately with songs from this region . He explains this with the fact that these songs repeatedly “show micro-variations [and] occasionally with regard to rhythm and melody are anything but regular”. According to Tom Kannmacher , folk songs are generally "subject to the currents of tradition, cultural epochs, rule relationships and thus never [take] fixed forms that could be documented or materially grasped". As with the text with its numerous variations, this variety of musical interpretation was also favored by the oral form of the tradition.

The melody is in the Doric mode , which is typical of the Celtic - Anglo-Saxon folklore. Since the Doric scale corresponds to the minor scale up to the 6th level , the corresponding minor triad is used as the basic key for a suitable harmonization .

The song, held in four-four time, was and is often danced at the very widespread Breton folk festivals ( Fest-noz ), usually in a ronde à trois pas (Dañs round) , a three-step round dance , a form that is everywhere in the Brittany is widespread and had its regional starting point in the coastal region of southern Cornouaille . Tri martolod fits this dance rhythmically very well because the tempo of the chorus increases compared to the two preceding lines of verse. For example, in the Pays de Léon it was also danced as a gavotte (Dañs tro) , such as in the “Gavotte de Lannilis ”. According to Bernard Lasbleiz, the round dance was popular with fishermen and sailors on the entire French Atlantic coast between Normandy and the Basque Country .

Instead of an alternating song (Kan ha diskan) , the music at festivals in Brittany often came and comes from two instrumentalists, typically with Binioù and Bombarde , and more recently, visitors no longer dance in a circular chain, but in pairs (see this picture below, taken at the Festival de Cornouaille in Quimper in 2014).

With his song version, Alan Stivell has linked the traditional elements of this folk music with the rock age, especially because of the instrumentation he has chosen . In addition to the medieval Celtic harp , which was strung with steel strings , to which he helped rebirth and dedicated his own long-playing record (Renaissance de la Harpe celtique , also from 1972 ) , he also picked up the single for Tri martolod, such as the live LP Alan Stivell à l'Olympia with the fiddle and a lute instrument (here a banjo ) goes back to other instruments that are often used in the music of Celtic regions. The song begins with a longer harp solo, and the harp then accompanies his singing through to the end. Even if Bombarde and typical Brittany bagpipes (Binioù kozh, Binioù bihan, Cornemuse) were dispensed with, instead electric guitar , electric bass , electronic organ and drums were used, the song still creates an overall sound impression that is close to that of the time it was composed comes. This was also due to the fact that Stivell gathered musicians with different stylistic backgrounds around him in 1972 , such as Dan Ar Braz, an electronic guitarist, the drummer Michel Santangeli, who worked with the rock 'n' roll band Les Chats in the 1960s Sauvages and Les Chaussettes Noires had celebrated successes, and the singer Gabriel Yacoub, who founded the folk band Malicorne the following year . Classified in Stivell's oeuvre spanning more than 50 years, the text, music and instrumentation correspond perfectly to an image that is not primarily nostalgically backward-looking and regionally restricted, but instead takes a stand for the present and the future against the restriction of cultural diversity and freedoms and against socio-economic oppression - regardless where on earth they happen.

Origin and variants of the song

Bernard Lasbleiz has examined 32 historical versions of Tri martolod from the 19th and 20th centuries , including Stivell's earliest version , found in song books, public archives, on records and in lists of songs. The oldest of these versions comes from the Cahier de chanson du Croisic of 1809; it is not included in the Barzaz Breiz of 1839. These included not only Breton but also a number of French-language texts with titles such as Les trois marins de Nantes (“The three sailors from Nantes”) or a similar one, but not those in Gallo . What all these versions have in common is that they deal with events from Brittany or the immediately adjacent regions. A more precise indication of the function and branch in which the young men are active - fishing, merchant shipping or other - does not contain any of the versions; even in French they are simply referred to as marins (seamen) or matelots (sailors).

Musically there are also at least partial differences: versions from western Basse-Bretagne ( Breizh Izel , Niederbretagne), which Alan Stivell also used, are more uniform than those from eastern Haute-Bretagne, which is closer to France ( Breizh Uhel , Upper Bretagne ). Another differentiation is the length of the songs: some versions contain only six to ten stanzas, while others contain up to twenty. The latter are not only more suitable for more extensive dancing, but also linguistically more elaborate , with rhyming lines of verse and sometimes with a musical epilogue . One of these songs emphasizes the female main character in the title, namely La servante du meunier ("The miller's maid"). And finally there is even a version from the agrarian inland in which the sailors have become servants and fellows (valets, bons gars) .

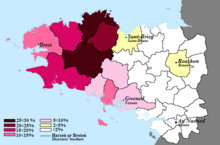

Lasbleiz uses his research to determine whether the song originally originated in Breton - that is, west of a line from Saint-Brieuc via Josselin to Saint-Nazaire , where Breton was the only language of the large majority of the population in the 18th century - or in the French-speaking area for not decidable. Based on a comparison of two texts from the mid-19th century, he is relatively certain that the Breton version from the Pays de Léon is younger than the French one from Châteaulin ; because it uses words that were not included in any contemporary Breton dictionary, such as konesañs (from the phonetically identical-sounding connaissance ). But these are just pieces of the mosaic, and folk songs often have regionally diverse roots. What he can say with some certainty, however, is the observation that the earliest Breton-language song variants originated in the Gulf of Morbihan and spread from there to Finistère in the north .

Lasbleiz counts in particular Aux marches du palais and La Flamande among the other folk songs that are thematically reflected in Tri martolod . In fact, the woman who reunited with the sailor in the mill is, in some song versions as Flämin (in French Flamande , in Breton Fumelen called), which in France both for women from Flanders as well as those from the north of France is the region bordering Belgium - two areas which together roughly encompass the early modern province of Artois . Why in Tri martolod there are three or even more seafarers in individual cases, although from the fifth stanza onwards there is only one, the author explains with an “old cliché ”, according to which in folk songs certain groups of people and professions “always come in threes ".

On the question of the regional and linguistic origin of the song, Pascal Lamour notes that in the Basse-Bretagne the ballads named Gwerzioù often had the character of lamentations in terms of text , whereas in the Haute-Bretagne they would have expressed the wisdom of the people. Tri martolod in the long versions contains elements of both: complaints about poverty, but also the optimistic view of overcoming it by taking nature as an example. In a further review the song is described as "despite the material need of the lovers [...] anything but larmoyant "; rather, it invites you to dance and thus corresponds to an attitude that has prevailed for centuries, "material hardship - if it could not be eliminated - at least 'dance away' for a few hours."

Further versions since 1972

Tri martolod , which had only been released on record before 1972 - in the 1960s by the folk group An Namnediz - developed for the author Gilles Verlant into one of the most important identity-forming songs in Breton music by the end of the 20th century; and according to Bernard Lasbleiz it has "undoubtedly become the most popular traditional Breton song since the early 1970s." This is reflected in a large number of cover versions - musicme.com, for example, lists 141 versions by 41 performers - which can only be named very selectively.

By Alan Stivell

Alan Stivell himself performed Tri martolod at concerts in the following decades and re-released it several times on other records in different versions and arrangements of different lengths - between three and four and a half minutes. Since the audience always demanded this song from him, he wanted to "counteract the routine of permanent repetition" with his variations . These include a rockier version on the album Again (1993), on which he is accompanied by Pogues singer Shane MacGowan and Laurent Voulzy , a version from 1999 together with Tri Yann, Gilles Servat , Dan Ar Braz and L'Héritage des Celtes with the Armens group at a concert in the Palais Omnisports in Bercy , a performance on the occasion of the recording of his anniversary concert on DVD (40th Anniversary Olympia 2012) , in which it leads directly to the Breton national anthem, as well as a live recording from 2016 in a duet with Joan Baez . In 2010 he had surprised the audience with an extremely fast and jazzy version of his “classic” at a performance during the “ Paris-Plages ” event . On Spotify , this is Stivell's most frequently viewed title (by the end of March 2019: over 410,000 views), followed by Brian Boru (305,000) and Bro gozh ma zadoù (200,000), which is also an indication of decades of international and cross-generational popularity ( " Evergreen ").

In May 2009, the song was the focus of an unusual occasion, namely at the official ceremony before the soccer cup final at the Stade de France , which two teams from Brittany had reached with Stade Rennes and En Avant Guingamp . Both clubs had asked the organizing national association FFF to play the Breton national anthem in addition to the French national anthem, which the latter refused. Instead, Alan Stivell, accompanied by two Bagadoù from Guingamp and Rennes , intoned Tri martolod on the stadium lawn , and a large part of the 80,000 spectators sang the song along.

From other artists

Also Tri Yann had the song in 1972 for her first LP Tri Yann at Naoned (Three jeans taken from Nantes); In the following decades they also sang it frequently and in different versions, for example on their 2012 album Chansons de marins . After the renaissance of Breton, which was not limited to music, in the 1980s, the circle of interpreters of this piece expanded considerably from the mid-1990s, especially starting with a techno version by Deep Forest (1994) and published on CD a traditional vocal version by Yann-Fañch Kemener , accompanied by the pianist Didier Squiban (1995).

In 1998 the hip-hop trio Manau took over parts of the melody, the arrangement and the instrumentation from Stivell in its million-seller La Tribu de Dana , which was also featured on the LP Panique celtique, which was awarded a “ Victor ” - the French equivalent of the Grammy Awards is included; Both records were number one in the French charts for weeks . Alan Stivell was not enthusiastic about this "blatant plagiarism ", which had used longer sections of his version without his consent or at least indicating its origin. What particularly bothered him was the use of his original intro by the sampler , because he had played it on his first own Celtic harp, built by his late father, which was very important to him personally: “It was something of a desecration ". The title of the Manau hit contains a further reference to Celtic songs, namely the Gaelic song Túatha Dé Danann (The people of the [goddess] Danu ); Stivell recorded this in 1983 for the soundtrack of the film Si j'avais mille ans by Monique Enckell .

In 2003, the French-Canadian singer Claire Pelletier released Tri martelod on her LP En concert au Saint-Denis , and in the same year Gérard Jaffrès on his album Viens dans ma maison . Bretonne , Nolwenn Leroy's 2010 number one album in France and Belgium, begins with Tri martolod ; for the singer "it had to be this traditional sea shanty and in Breton". Its single release also reached the French charts and now has almost 2.2 million views on Spotify (as of November 2019). The song was also nominated for the NRJ Music Awards on TF1 in the "French Song of the Year" category. In it, the interpreter "has [connected] the folk elements [of the song] with pop culture in a pleasing manner." At the 2012 Victoires de la Musique ceremony on France 2 , Leroy interpreted it in a more empathic version, accompanied by, among others Virginie Le Furaut (Celtic harp), Robert Le Gall (violin) and Frédéric Renaudin (piano). On a concert tour in the same year she sang this song together with Alan Stivell, also accompanied by the Irish band The Chieftains in Olympia. A native of Brittany Shanty - Chor Les Marins d'Iroise published the 2011 title as Tri Martelod Yaouank .

Back in 2008, the Swiss folk metal band Eluveitie was inspired by Tri martolod for the track Inis Mona , which is included on their LP Slania . Behind its title Ogmios from 2014 is an instrumental version of this traditional, in which the melody is played on a chromatic harmonica . The “ Middle Ages Band ” Dunkelschön performed the song in Breton language and with acoustic instruments during a live performance, while on their album Zauberwort (2011) they performed the song with an electric guitar and organ. In the following year, a German version with individual verses in Breton appeared on Bis ans Ende der Welt by Santiano together with the singer Synje Norland . Other German groups also preferred to sing the version of the song in Breton and published it on long-playing records , such as Tibetréa on Peregrinabundi (2014), Annwn on Enaid (2016) and Connemara Stone Company on Toss the Feathers (2018).

In the 2000s there were also a large number of interpretations in other languages and dialects, for example in 2005 in Polish by Ryczące Shannon with cornemuse and electric guitar, in 2008 by Nachalo Veka in Russian, titled Тебя Ждала (I've been waiting for you ), and in Hungarian by Arany Zoltán . The ex-choirs of the Red Army also sang the song at a performance in France in 2012 and released it on CD in 2016. 2013 versions in Tahitian and Hindi ( Olli and the Bollywood Orchestra on the album Olli Goes To Bollywood , titled Teen Aazaad Naavik ), 2015 a Corsican version ( Trè Marinari by Jean Marc Ceccaldi).

Representing the extremely numerous instrumental versions of Tri Martolod , the one by André Rieu with his Johann Strauss Orchestra should be mentioned, which is featured on the album Dansez maintenant! between Swan Lake and Vienna is only heard beautifully at night . The song belongs in particular to the repertoire of many traditional instrumental groups (bagadoù) , most of which come from Brittany and have held an annual national championship since 1949, in which they are divided into five quality categories. In the 2010s, 75 of them belong to the top four “ leagues ”, all others to the fifth category.

literature

- Laurent Bourdelas: Alan Stivell. Ed. Le mot et le reste, Marseille 2017, ISBN 978-2-3605-4455-4 .

- Joël Cornette: Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons. Tome 2: Des Lumières au XXI e siècle. Ed. du Seuil, Paris 2005, ISBN 978-2-7578-0996-9 .

- Pascal Lamour: Un monde de musique bretonne. Ed. Ouest-France, Rennes 2018, ISBN 978-2-7373-7898-0 .

- Bernard Lasbleiz: Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet! In: Musique bretonne. Issue 155, May / June 1999 ( PDF ).

- Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard (eds.): Toute l'histoire de Bretagne. Des origines à la fin du XX e siècle. Skol Vreizh, Morlaix 2014, 5th edition, ISBN 978-2-915-623-79-6 .

additionally used:

- Divig Kervella: Geriadur bihan divyezhek Brezhoneg / Galleg ha Galleg / Brezhoneg. Mouladurioù Hor Yezh, Kemper (Quimper) 2014, 3rd revised and expanded edition, ISBN 978-2-86863-081-0 (basic dictionary Breton ↔ French).

Web links

- Lyrics in Breton and French and sheet music

- Sheet of music

- Detailed review of the song at literaturplanetonline.com

Evidence and Notes

- ↑ Bernard LASBLEIZ, tri Martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p 15; see also the lyrics of a long version with 15 stanzas in Breton and French as well as a notation of the vocal part.

- ↑ Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, p. 36.

- ↑ a b c d Bernard Lasbleiz, Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Nantes had been the historic Breton capital since the Middle Ages , before the city and the surrounding Loire-Atlantique department ( Liger-Atlantel in Breton , order number 44) was separated from the modern administrative region of Brittany ( Breizh ) by order of the Vichy regime in 1941 . With Bretagne réunie , 44 = Breizh and Breizh 5/5, there are a number of associations and movements in the 21st century that strive for the reunification of all five Breton departments.

- ↑ a b Bernard Lasbleiz, Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 16.

- ↑ Stivell's 1972 version on YouTube

- ↑ Since the central government in Paris approved bilingual teaching (French and Breton) in all schools in 1977 with the Breton Cultural Charter in Brittany , the number of pupils participating has increased from 1,774 (1992) to more than 14,000 (2012) - Jean- Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 813.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 773.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, pp. 20 and 62.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, pp. 76 and 80.

- ↑ Review of Bruce Eder's concert recording at allmusic.com

- ↑ article "L'anthem to" from the magazine Bretons , Issue 80, October / November 2012

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 77.

- ↑ Article " Alan Stivell, influenced from many directions " from February 29, 2008 at telerama.fr

- ↑ Joël Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons, 2005, Volume 2, p. 325. Although France had lost its territorial claims to Newfoundland in the Peace of Utrecht (1713), it kept on the so-called French coast there until 1904 (French Shore) but still has fishing rights (see The French Treaty Shore on heritage.nf.ca). Only 25 kilometers south of Newfoundland is Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, the last French territory of the former colony of New France (Nouvelle-France) in the 21st century .

- ↑ Joël Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons, 2005, Volume 2, p. 111 ff.

- ↑ Joël Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons, 2005, Volume 2, p. 325 f. and 329.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 402.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 394.

- ↑ Joël Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons, 2005, Volume 2, in particular pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 384.

- ↑ "microvariations dans la mélodie [...] car le rhythme échappe parfois à toute régularité, pour les marches comme pour les mélodies" - Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, p. 34 f.

- ↑ Tom Kannmacher: The German folk song in the folksong and songwriting scene since 1970. In: Yearbook for Folk Song Research , Volume 23 (1978), p. 38.

- ↑ a b c d e The Breton folk song Tri martolod at literaturplanetonline.de

- ↑ see the sheet of music at pagesperso-orange.fr

- ↑ See partitions.bzh .

- ↑ In 1990 around 300 of these often multi-day events were held in Brittany. In 2012, their number had risen to 1,500, and they were no longer limited to Brittany itself - Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, pp. 812 and 822.

- ↑ a b c Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 74.

- ↑ Two historical versions of the song even explicitly state that the refrain should "be emphasized more strongly and sung faster" - Bernard Lasbleiz, Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 17.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 245.

- ↑ Gavotte de Lannilis , text and dance video at lannig.e-monsite.com (“Learn Breton dances”).

- ↑ a b Bernard Lasbleiz, Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 17.

- ↑ Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, p. 20.

- ^ Joël Cornette, Histoire de la Bretagne et des Bretons, 2005, Volume 2, p. 588.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 82.

- ↑ Gilles Verlant (ed.): L'encyclopédie de la Chanson française. Des années 40 à nos jours. Ed. Hors Collection, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-258-04635-1 , p. 134 f.

- ^ Catherine Franc: Le Moyen Age dans la musique populaire régionale en France contemporaine. , in: Timo Obergöker / Isabelle Enderlein (Eds.): La chanson française depuis 1945. Intertextualité et intermédialité. , Martin Meidenbauer, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-89975-135-2 , pp. 211 and 218.

- ↑ Bernard LASBLEIZ, tri Martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 19

- ↑ Gallo was the language widespread in large parts of Haute-Bretagne, but since the beginning of the early modern period it had gradually been replaced by French.

- ↑ a b c Bernard Lasbleiz, Tri martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Bernard LASBLEIZ, tri Martolod à travers les mailles du filet, 1999, p. 18

- ↑ This dividing line is also visible in the distribution of place names : the Breton ker dominates to the west, the French ville to the east - Jean-Yves Le Moing: Noms de lieux de Bretagne. Ed. Christine Bonneton, Paris 2007, ISBN 978-2-86253-404-6 , pp. 149 f.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Monnier and Jean-Christophe Cassard, Toute l'histoire de Bretagne, 2014, p. 419.

- ↑ Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, pp. 33–35.

- ^ The Breton folk song Tri martolod at literaturplanetonline.de; an excerpt from the An-Namnediz version can be found at nozbreizh.fr .

- ↑ Gilles Verlant (ed.): L'encyclopédie de la Chanson française. Des années 40 à nos jours. Ed. Hors Collection, Paris 1997, ISBN 2-258-04635-1 , p. 143.

- ^ Version list of Tri martolod at musicme.com

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 151.

- ↑ Tri Martolod at the "Bretagnes à Bercy" on YouTube

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 231.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 206; Quote on p. 170.

- ↑ Declaration of the FFF dated May 6, 2009 (archive link) - Five years later these two clubs faced each other again in the cup final , and this time the FFF officially allowed the Breton anthem to be played after the French national anthem. In the meantime, Noël Le Graët, a Breton, had been elected to head the football association.

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 198; see also the film excerpt from this appearance on YouTube.

- ↑ Chansons de marins with a track list at discogs.com; an earlier version of Tri Yann from 1981 can be found on YouTube .

- ↑ Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, p. 52 f.

- ^ Version by Kemener and Squiban on YouTube

- ↑ Video of La Tribu de Dana on YouTube

- ↑ Article “ La tribu de Dana ” from August 20, 2005 in Le Monde

- ^ Hubert Thébault: La Tribu de Dana. in: Christian-Louis Eclimont (Ed.): 1000 Chansons françaises de 1920 à nos jours. Flammarion, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-0812-5078-9 , p. 876.

- ↑ Gilles Verlant points out that the text and music of this about 200 year old folk song were in the public domain - Gilles Verlant: L'Odyssée de la Chanson française. Ed. Hors Collection, Paris 2006, ISBN 978-2-258-07087-5 , p. 312.

- ↑ Article “ Polemics about a 'sample' of Stivell's Tri martolod through Manau ” from August 15, 1998 in L'Humanité

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 134.

- ↑ Claire Pelletier in a concert by St-Denis on YouTube

- ↑ Laurent Bourdelas, Alan Stivell, 2017, p. 209.

- ↑ Video of Leroy's 2012 appearance on YouTube

- ↑ TV recording of the concert on St. Patrick's Day in Brest on YouTube

- ↑ Nolwenn Leroy and the Chieftains on YouTube

- ^ Lecture by the Marins d'Iroise at the Seaman's Song Festival 2011 in Paimpol on YouTube

- ↑ Eluveities Ogmios on YouTube

- ↑ Videos of a live ( unplugged ) and a vinyl version of Dunkelschön , both on YouTube

- ↑ Santiano video on YouTube

- ↑ Video by Тебя Ждала on YouTube and the artist's official website (nachaloveka.ru).

- ↑ Article “ The General, who lets the Red Army choir sing tri martolod ” from March 16, 2012 on Ouest-France and CD box with track list and audio sample on indigo.de.

- ↑ Article “ Tahiti. Tri Martolod in the flower wreath version ”from March 10, 2013 at letelegramme.com

- ↑ CD album and list of songs at discogs.com

- ↑ Tré Marinari. Discography by Jean Marc Ceccaldi (Scelta Celta, 2015, song no.5).

- ↑ Tracklist from Dansez maintenant! at universalmusic.fr

- ↑ Pascal Lamour, Un monde de musique bretonne, 2018, pp. 147–153.