Spring offensive in Italy in 1945

Operation Grapeshot

| date | April 9 to May 2, 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Northern Italy |

| output | Allied victory |

| consequences | Partial surrender of the German troops in Italy |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 15th Army Group British 8th Army 5th US Army about 1,333,000 men |

Army Group C 10th Army 14th Army around 585,000 men |

| losses | |

|

April 30 approx .: 16,300 casualties (3,100 dead, 12,900 wounded, 300 missing) |

April 30 approx .: 32,000 casualties (dead, wounded, missing) |

1940–1945: Air raids on Italy

1940: Attack on Taranto

1943: Operation Husky - Invasion of Italy ( Baytown , Avalanche , Slapstick ) - Armistice of Cassibile - Fall of the Axis

1944: Battle of Monte Cassino - Operation Shingle - Position of Goth

1945: Spring Offensive

The spring offensive in Italy in 1945 , alias Operation Grapeshot , was the final offensive led by the Allies from April 9 to May 2, 1945, which ended with the partial surrender of the German troops in Italy and the collapse of the Italian Social Republic .

prehistory

In 1944, after the Cassino battle in May and the capture of Rome on June 4, 1944, the Allies had advanced to the position of the Goths . This also gave up the tactic of delaying defense that had been practiced by the Wehrmacht until then, with which the advance of the Allies was to be slowed down and, as ordered by the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW), the defense at the Goths position, which was declared the main line of resistance, was set up.

Between the end of August and the beginning of September 1944, the Allies succeeded in breaking through the German line of defense running north of Florence from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea . In particular, the flat and slightly hilly left defensive section on the Adriatic coast was indented by the British 8th Army by the end of the year and had to be withdrawn several times. In the central area in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines , the 5th US Army also managed to break through the German lines. On the other hand, it remained relatively calm on the Tyrrhenian coast and the course of the front remained largely unchanged here.

At the end of 1944 the front stood still. The wintry conditions made further major offensive actions by the Allies impossible. The goal set by the Allies to liberate Bologna before Christmas 1944 was not achieved. The British 8th Army was able to occupy the southeastern edge of the Po plain between Faenza - Ravenna and the lagoon landscape Valli di Comacchio , but supply problems and the exhausted troops slowed the attack, which finally came to a standstill about 30 km from Bologna. The units of the 5th US Army that were advancing there also got stuck on the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines . By then the Allies had lost around 30,000 and the Germans and the RSI associations around 50,000 dead, wounded and missing in the attack on the Goths .

From the actual Goth position at the end of 1944 only the western area on the Tyrrhenian coast was in German hands. In anticipation of the Allies' spring offensive, the Germans expanded their defensive positions along the front line reached in December.

planning

Allies

In mid-December 1944, US General Mark W. Clark took over command of the 15th Army Group from the British Harold Alexander , after Alexander was appointed as the new head of the Allied Forces Headquarters in the Mediterranean (AFHQ). Less than two weeks later, on December 30, 1944, Clark ordered all offensive actions to be stopped and to go into defense. Until the beginning of April 1945, apart from locally limited actions, things remained quiet on the front in northern Italy. Even if since the landing in Normandy in June 1944 and the landing in southern France in August 1944 the Italian theater of war only played a secondary role in the planning of the Western Allies, the idea of an all-important final offensive in the following spring was retained. The winter break was therefore used for planning and preparation. At the beginning of January 1945 it was already clear that the offensive would begin before May.

By and large, the plan of attack was drawn up by the end of January 1945. Clark held on to a two-part attack, as had already been carried out by his predecessor Alexander in 1944 when he attacked the Goths, as the attack area did not offer enough space for the deployment of two armies and a single concentrated attack. It was unclear who would lead the main thrust of the attack. The British Richard McCreery was of the opinion that this task was due to the 8th Army as a numerically stronger unit, especially since the attack area in the Po Valley was much simpler than the mountainous area in the Apennines caused by the advance of the 5th US Army should be performed. Clark, however, doubted the offensive power of the British and initially did not commit himself to this question.

Doubts about the effectiveness of their own troops were also fed from other sources. The Allies were concerned about the reliability of the Second Polish Corps after the Curzon Line had awarded parts of eastern Poland to the Soviet Union at the Yalta Conference in early February 1945, despite protests by the Polish government- in- exile in London . At around the same time, the Canadian corps and two British divisions were withdrawn from Italy and transferred to other theaters of war. The newly formed 10th US Mountain Division was added as a replacement, which would later prove to be particularly strong in the fighting on the Apennines. Between January and February four of the five Italian combat groups formed by the Badoglio government were also operational. The supposedly strongest of these combat groups, the so-called Folgore , was the XIII. British corps attached, while the others were initially entrusted with security tasks.

On February 12th, Clark unveiled his three-stage plan of attack. For the first time, more far-reaching operational goals emerged. The plan initially envisaged the breakthrough through the German lines in a pincer movement and the construction of a bridgehead north of Bologna. The attack by the two armies should be staggered in time so that the two armies could fall back on the full air support of the Allied air forces at the start of each attack. In the second step, the Po should then be crossed and the march on Verona continued. The third stage provided for the advance across the Adige Valley to the Brenner Pass for the 5th Army , while the 8th Army was to advance towards northeast Italy and then into the Danube basin. Under pressure from the Allied High Command, Clark had to change this plan. The final plan of attack was presented on March 18. The primary goal was now the destruction of Army Group C south of the Po and the subsequent capture of Verona.

Smaller offensive companies before the actual offensive should examine the German defense, ensure a better starting position and tie up German troops. As early as February 8, 1945, US units took action on the Tyrrhenian coast in Operation Fourth Term against Massa . A landing maneuver on the Adriatic should also be simulated as a diversionary maneuver. An attack by French troops planned by Field Marshal Alexander on the 34th Infantry and the 5th Mountain Division in the Western Alps was called off because of the negative attitude of the Italian government, which refused to occupy Italian territory in the border area with France by French troops.

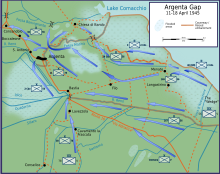

British 8th Army

There were three potential lines of intrusion for the 8th Army. In the left attack area along Via Emilia , which was already heavily defended by the Germans at the end of 1944 , to the north of it in the Budrio - Massa Lombarda area and on the far right area on Via Adriatica and between Reno and the Comacchio lagoon. In particular, the advance north of the Reno to Argenta made it possible to bypass the German defensive lines built south along the Reno tributaries, but also involved some risks. The strip of land only about two kilometers wide and eight kilometers deep, some of which had been inundated by the Germans, was easy to defend. The operation could only succeed if Argenta was captured at the northwest end of the strip. From Argenta, which lay behind the defensive lines of the Germans, the Allies could continue unhindered to the Po. Aware of its importance, the Allies referred to the strip of land as the Argenta gap (dt. Argenta gap). With the provision of 600 Fantails by the US Army to transport the troops across the Comacchio lagoon behind the enemy lines, the greatest doubts were dispelled. In order to have a free deployment area for the Fantails, the narrow headland that separates the Adriatic from the Comacchio lagoon should be occupied in a previous operation. It was considered crucial for a successful outcome that the German reserves had to be tied up by a wide-ranging attack by the army group so that they could not be moved to Argenta.

After the withdrawal of the Canadians and the two British divisions in early February 1945, the main thrust was to be carried out by the 5th Army. The 8th Army, however, had the task of opening the offensive. After the V British and II Polish Corps had crossed the Senio and Santerno rivers , the V Corps was to turn north, take the Reno Bridge at Bastia, southeast of Argenta, and support the attack against Argenta, while the Poles continued to head northwest should move towards Budrio. Depending on the outcome of the fighting over the Argenta Gap, it should then be decided whether Ferrara or Budrio should be the primary target of the 8th Army. In a second step, the Wehrmacht's escape routes were to be cut off and the crossings over the Reno and Po at Ferrara and Bondeno to be occupied and a connection to the 5th Army established. If the second phase of the attack was successfully completed, a bridgehead should finally be built over the Po and, in a third step, the remaining forces should be pushed towards Verona.

McCreery issued the 8th Army Plan of Assault on April 3rd. According to the plan, the V Corps and the II Polish Corps should attack the Senio at the same time on a front length of 10 kilometers between Fusignano and Alfonsine and then continue the attack against the German defensive line on the Santerno between Massa Lombarda and Mordano . Then the V Corps should march in a northerly direction on the Reno Bridge at Bastia south of Argenta, while the Poles should advance on Budrio and Castel Pietro. If the 2nd Corps should advance too slowly, the New Zealand 2nd Infantry Division should support the advance. In the section lying south of the II. Polish Corps in the foothills of the Apennines, the X. and the XIII. Corps deploy. The task of the two corps was to bind the opposing troops in this sector.

In total, the British 8th Army went to attack with about 633,000 men. The attacking V Corps with the Indian 8th and New Zealand 2nd Infantry Divisions had almost 680 guns and numerous Churchill Crocodile flamethrower tanks at their disposal. The II. Polish Corps, commanded by Zygmunt Bohusz-Szyszko , could fall back on almost 340 artillery pieces, so that over 1000 artillery pieces were ready on the 10 kilometers of the attack front on the Senio.

5th U.S. Army

In the case of the 5th US Army, a number of weak points were addressed in the planning that had occurred during the previous offensive on the Gothic position in the area of the 5th Army. The main thrust was not to take place along the Futapass road SS 65, where the advance was stopped by the Germans at the end of 1944, but rather the longer and more difficult route along the mountain ranges west of the Reno Valley and the SS 64 should be chosen. In order to create a better starting position, the 10th US Mountain Division occupied the heights west of the Reno between February 18 and March 5, 1945 . The beginning of the offensive in the 5th Army was scheduled two days after that of the 8th Army. With the staggered timing, the Allied air forces were to fully support the respective attack.

General Lucian K. Truscott announced the order to attack the 5th Army on April 1st. The IV. Corps, led by Willis D. Crittenberger , was supposed to initiate the offensive with an advance west of the SS 64. On the right flank, IV Corps under Geoffrey Keyes was to be secured. With this advance it was hoped to lure the Germans away from the SS 65 so that the Futapass road would be free for the advance of the II Corps. After the capture of Sasso Marconi in the Reno Valley, the focus of the attack was to be shifted westward and the two corps to pass Bologna side by side. In detail, the multi-stage plan of attack stipulated that the IV Corps should advance between the Samoggia and Reno valleys as a first step . The 1st US Panzer Division was given the task of attacking via the SS 64 and west of the Reno bank, while the 10th US Mountain Division had to advance on the ridge that separates the two valleys. The Brazilian Expeditionary Corps to the west and the Italian combat group Legnano to the east were assigned to secure the two flanks .

In a second phase, II Corps was to attack parallel to IV Corps and advance towards Monte Sole and Monte Adone on both sides of the Setta Valley. After reaching the Po plain, the plan of attack provided that the tank formations should advance further north in a hurry. The US 1st Panzer Division was ordered to move towards Modena , while the South African 6th Panzer Division was to march towards Bondeno on the Panaro River south of the Po to join the British 8th Army and encircle Bologna complete. Artillery preparations before the offensive were not carried out in order not to lose the surprise effect. However, the attack should be supported by massive air strikes, as with the 8th Army. The 5th Army had about 267,000 men available for the attack.

German countermeasures

Up until March 1945, the Foreign Army West department in the OKW assumed that the Allies would undertake a smaller offensive action in northern Italy. The assessment was based on the large number of troop departures that had been observed since the offensive ceased in December 1944. The Chief of the General Staff of Army Group C, General of the Armored Force Hans Röttiger , contradicted this on March 13, 1945 , but remained unheard. On March 22nd, the OKW ordered the withdrawal of 6,000 paratroopers, who were withdrawn from the 1st and 4th paratrooper divisions to form two new divisions. Despite the OKW's attitude, Army Group C was preparing for an Allied attack in early April.

Colonel-General Heinrich von Vietinghoff , who had taken over command of Army Group C from General Field Marshal Albert Kesselring on March 10, 1945 , concentrated his strongest units in the Po Valley around Bologna, as this was where the main thrust of the motorized Allied units was awaiting. To the south-east of Bologna, a series of rivers draining from the Apennines formed natural obstacles that the German army command developed as lines of defense. From east to west these were the Irmgard position on the Senio , the Laura position on the Santero , the Paula position on the Sillaro , the Anna position on the Gaiana and the Genghis Khan position on the Idice . Other natural obstacles were the northern foothills of the Apennines between Faenza and Modena and the Comacchio lagoon. The Todt organization had already developed the banks of the Po and Etsch for defense purposes . Behind it was the so-called pre-alpine position, also known as the blue line, which led from the Swiss border over Lake Garda in the west to the Isonzo in the east, but was only partially completed.

Additional lines of defense had been built along the Adriatic coast to intercept possible landing attempts by the Allies. The stretch of land southeast of Argenta, located between the Po and the Reno River , was flooded in large parts by blowing up the dams. In March the weather improved and it became sunnier and drier. The levels of the rivers sank and made it possible for the infantry to cross them, even if the minefields created by the Germans on the banks and the machine-gun nests built in the embankments were still a serious obstacle.

The fighting strength of the Axis powers was severely limited by the poor supply situation and deteriorated further in the course of the spring. In particular, the fuel and vehicle shortages and the lack of air support made themselves felt, but also the stocks of stocks, especially of artillery ammunition, aroused concern. The operational readiness could be maintained to some extent through strict cost-saving measures, but the almost constant presence of the Allied air forces during the day severely restricted mobility. Troop movements were only possible at night or in bad weather conditions. On March 6th, the OB Südwest informed the OKW that the supplies had slipped below an acceptable level.

The target strength of the troops had been improved somewhat after the winter break in combat, but was nowhere near that of the Allies. Especially since the troops had been “ freshened up ” by soldiers combed out, convalescent or taken from sick leave . Only the 8th Mountain Division had a target figure of more than 3000 front soldiers at the beginning of 1945. The other divisions had a combat strength of 1000 to 2500 men, about one to two thirds less than that of the Allies.

During the winter, several divisions had also withdrawn from Italy and transferred to other theaters of war. The 710th Infantry Division was not even until the beginning of April, when the offensive intentions of the Allies were already beginning to emerge. The 10th and 14th Army had eight divisions each, plus two other divisions, which were deployed in the hinterland to protect against partisans, and four Italian divisions of the RSI. The army group's reserves were limited to the 29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier Divisions and the 155th Infantry Division, which was just being formed . The 29th was initially relocated to the upper Adriatic coast near Venice on March 22nd , because the Allies feared an attempt to land north of the Po, and later on April 5th, two battalions were transferred to the Tyrrhenian coast during Operation Second Wind of the Allies . The 155th Infantry Division was entrusted with coastal protection tasks, which had only been set up at the beginning of February 1945 from the renaming of the 155th Field Training Division and whose set-up had not yet been completed. Army Group C had 349,000 men and 45,000 Italian soldiers from the RSI were subordinate to it. In the hinterland there were also 91,000 men who were recruited from the police, security forces and flak troops, as well as 100,000 Italian police officers. The Army Group was able to muster a little more than 1,400 pieces of artillery, the number of operational tanks was 260.

The noticeable deterioration in German-Italian relations also caused concern. On March 27th, Vietinghoff received instructions from Jodl to exercise caution when dealing with Italian officers, public figures and RSI units. The apparent disintegration of the Italian Social Republic also strengthened the Resistance and contributed to open resistance against the Wehrmacht.

Despite the inferiority, Hitler had forbidden any retreat in a decree of February 22, 1945. This meant that the plan drawn up by Army Group C for an organized retreat across the Po into the so-called Alpine fortress, code name company Herbstnebel, became obsolete. The OKW also rejected a proposal by the commanding general of the 10th Army, Traugott Herr, on April 6th to withdraw the front line on the Senio under the protection of its own barrage .

In contradiction to the specifications of the OKW, Herr had already set up the main line of defense along the Santerno outside the range of the Allied artillery and had only an outpost built on the Senio . In doing so, he withdrew the majority of his troops from the enemy artillery, but underestimated the strength of the Allied air forces stationed in the Mediterranean area, which were available to support the offensive due to the advance of the Red Army on the Eastern Front and their targets no longer being targeted there.

Resistance a

At the beginning of 1945, parts of the Allies began to change their opinion on the use of the Resistancea in the Italian campaign. Until the end of 1944, the Italian resistance behind the German lines was safely supplied with weapons and equipment by the two military intelligence services, the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). The Headquarters of the Allied Forces in the Mediterranean (AFHQ), headed by Field Marshal Alexander, did not succeed in coordinating the work of the two competing intelligence services and in pursuing a unified line, but it did support the partisans' military operations, especially German communications should interrupt as possible.

At the beginning of January 1945, when the first planning for the spring offensive was underway, the AFHQ asked itself to what extent an increase in resistance in the north would not be counterproductive for post-war order and security in view of the looming end of the war. At the same time, there were doubts about the military efficiency of the partisan units. The danger that the communist resistance groups would try to seize power with the Greek People's Liberation Army , as in Greece , was seen to be rather low, even if some partisan groups were barely or not at all controlled by the Allies.

On February 4, 1945, the AFHQ passed a decree with which the tasks of the Resistance and their support by the Allies were redefined. After that, the resistance should only be used for organized acts of sabotage. Weapons and equipment were only supplied to those groups that could be useful in the offensive, while the Committee for National Liberation for Northern Italy (CNLAI) was to be entrusted with maintaining law and order in the post-war period. For the partisan units already fighting in the ranks of the 5th and 8th Army, the Maiella Brigade and the 36th Garibaldi Brigade, it was agreed at the beginning of March 1945 that 500 men would be used for espionage and reconnaissance missions.

However, the attempt by the headquarters to enforce this policy against the Resistancea failed because of those organs that were supposed to implement the orders of the AFHQ, in particular the 15th Army Corps, led by US General Clark, and the US intelligence service OSS, which was responsible for the delivery of weapons the resistance even increased. On the American side, the decree saw the attempt by the British to define possible spheres of influence in the post-war period and to disguise this by combating a supposed communist danger.

On April 17th, one week before the Resistance's call for a general uprising , the February 4th decree was amended by the AFHQ and the restrictions on the resistance formations fighting on the Apennines and those groups operating on missions behind enemy lines were lifted. The restrictions on the dropping of non-military material for all other areas have also been suspended. Weapons could also be supplied as replacements for weapons that were lost or destroyed. By this time the Allies had already dropped 6000 tons of material for the Italian resistance behind the German lines since the beginning of the Italian campaign.

The military contribution of the Resistancea during the spring offensive was limited and was mostly limited to selective attacks on German units or facilities behind the front, which were often carried out under the guidance of Allied liaison officers. Due to the rapid advance of the Allies and the simultaneous rapid withdrawal of the Wehrmacht, there were no major fighting with the Italian resistance. Most of the Resistance prevented the Germans from using the scorched earth tactic . In the eyes of the Allies, the most important contribution of the resistance was the quick pacification of the cities, so that the Allies were not forced to deploy larger contingents of troops for security tasks and instead were able to continue the advance quickly. One of the particularly noteworthy achievements of the Resistancea was the peaceful liberation of the port city of Genoa, which was held by around 9,000 German soldiers, in which the local CLN negotiated the surrender of the German occupation troops on April 26, 1945 two days before the arrival of the Allies with the city commander Günther Meinhold .

Associations involved

Allies

- 15th Army Group (General Mark W. Clark )

- 8th British Army (General Richard McCreery )

- V British Corps (Lieutenant General Charles Keightley )

- 2nd New Zealand Division

- 8th Indian Infantry Division

- 56th British Infantry Division

- 78th British Infantry Division

- Italian combat group Cremona

- 2nd Commando Brigade

- 2nd Armored Brigade

- 9th Armored Brigade

- 21st tank brigade

-

II. Polish Corps ( Major Zygmunt Bohusz-Szyszko )

- 3rd Carpathian Division

- 5th Kresowa Division

- 2nd Polish Armored Brigade

- 7th British Armored Brigade

- 43rd Indian Lorried Infantry Brigade

- X British Corps (Lieutenant General John Hawkesworth )

- XIII British Corps ( Lieutenant General John Harding )

- 10th Indian Infantry Division

- Italian combat group Folgore

- Army Reserve:

- 6th British Armored Division

- 2nd British Parachute Brigade

- V British Corps (Lieutenant General Charles Keightley )

- 5th US Army (General Lucian K. Truscott )

- under direct command of the army:

- 85th Infantry Division

- 92nd Infantry Division

- II US Corps (Lieutenant General Geoffrey Keyes )

- 6th South African Armored Division

- 34th Infantry Division

- 88th Infantry Division

- 91st Infantry Division

- Italian combat group Legnano

- IV US Corps (Lieutenant General Willis D. Crittenberger )

- 1st Armored Division

- Força Expedicionária Brasileira

- 10th Mountain Division

- 365th, 371st Regimental Combat Team (from the 92nd Infantry Division)

- under direct command of the army:

- 8th British Army (General Richard McCreery )

Axis powers

Army Group C (Colonel General Heinrich von Vietinghoff)

-

10th Army (General of the Panzer Troop Traugott Herr )

- I. Parachute Corps ( General of the Parachute Troops Richard Heidrich )

- 1st Paratrooper Division

- 4th Paratrooper Division ,

- 26th Panzer Division

- 278th Volksgrenadier Division

- 305th Infantry Division

- Assault Gun Brigade 210

- LXXVI. Panzer Corps (General of the Panzer Troop Gerhard Graf von Schwerin )

- 42nd Hunter Division

- 98th People's Grenadier Division

- 162nd (Turk.) Infantry Division ,

- 362nd Infantry Division

- Heavy Panzer Division 504

- Heavy tank destroyer division 525

- Assault Gun Brigade 242

- I. Parachute Corps ( General of the Parachute Troops Richard Heidrich )

-

14th Army ( General of the Panzer Force Joachim Lemelsen )

- LI. Mountain Corps ( General of the Artillery Friedrich Wilhelm Hauck )

-

XIV. Panzer Corps (General of the armored forces Fridolin von Senger and Etterlin )

- 8th Mountain Division

- 65th Infantry Division

- 94th Infantry Division

- Assault Armored Division 216

- Assault Gun Brigade 907

-

Army Group Liguria ( Maresciallo d'Italia Rodolfo Graziani )

- LXXV. Corps ( General of the Mountain Troops Hans Schlemmer )

-

Corps Lombardia (General of the Artillery Curt Jahn )

- Fortress Brigade 135

- 3rd Italian Marine Infantry Division "San Marco"

- SS units ( SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff )

- Army Group Reserve

course

Operation Roast

On April 1, 1945, the initial operation for the spring offensive began with the deployment of Operation Roast . The aim of the spatially limited attack by the British 8th Army was to occupy the narrow coastal strip between the Adriatic Sea and the Comacchio lagoon , which the British called Split . A landing operation north of Porto Garibaldi should be simulated as a diversionary maneuver . With the help of several Fantails, partly obstructed by the low water level, the 2nd Command Brigade reached its starting positions before, after preparatory artillery fire from 150 guns, attacked the units of the 162nd (Turk.) In the morning hours of April 2nd. Infantry Division and 42nd Jäger Division defended section was blown. In the evening about half of the coastal strip was occupied by the Allies. The next day it was possible to advance south of Porto Garibaldi before the attack could be stopped by the Germans, who in the meantime had called in parts of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division for reinforcement. On the evening of April 3, the successful Operation Roast was declared over.

Operation Fry and Second Wind

In the days that followed, Special Boat Service troops in Operation Fry occupied several small islands in the Comacchio lagoon that had previously been cleared by the Germans. Another attempt to take Porto Garibaldi, southeast of Comacchio, on April 5, failed despite supportive air strikes due to German defensive fire. On the same day, the 92nd US Infantry Division attacked the cities of Massa and Carrara on the Tyrrhenian coast as a diversionary maneuver in Operation Second Wind , whereupon Vietinghoff transferred parts of his 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, serving as a reserve.

Operation Lever

On April 6, units of the British 56th Infantry Division set out in Operation Lever to attack the strip of land between Reno and Comacchio lagoon. Due to the fierce resistance of the 42nd Jäger Division, small gains in terrain were not made until the evening. An attack against Comacchio carried out at the same time was rejected by the Republican-Italian troops of the X Tr MAS . On April 7, the company was continued despite temporary German spear fire, another attack on Comacchio was repulsed again, as on the following day, by the Xª MAS and the 162nd (Turk.) Infantry Division.

Operation Buckland begins

On April 8, the British 8th Army began to deploy to attack the German Irmgard Line on the Senio River, alias Operation Buckland . Meanwhile, Operation Lever was suspended. The section on the Senio was defended by the 98th Infantry Division , which was supported by Heavy Panzer Division 504 .

In the early afternoon of April 9, 1945, Allied bomber groups with 825 heavy and 234 medium bombers as well as 740 fighter bombers began to attack the German defensive positions on the Senio. The Polish II Corps had to complain about 160 failures due to self- fire. Then a four-hour artillery fire with over 1200 guns started on the Senioufer and the area behind it. In the evening the New Zealand 2nd and Indian 8th Infantry Divisions got ready. Flamethrower tanks advanced and fired the German bunkers on the Senio. When the infantry crossed the Senio, the German defense was as good as off. Before midnight, two battalions of New Zealanders were on the other side of the river, while the Indians had set up a bridgehead about a kilometer deep at Lugo . In the 98th Infantry Division, four of a total of seven battalions were wiped out after the first day of the offensive.

The Poles were less successful in the left attack section. The self-fire and the fierce resistance of the 26th Panzer Division had stopped the advance so that the Polish troops were still on the right bank of the river after the first day of the attack.

On April 10, the British 56th Infantry Division marched on the northern wing of the 8th Army on Lake Comacchio for Operation Impact Plan, the landing on the strip of land southeast of Argenta between the Reno River and Comacchio Lagoon. Meanwhile, the break-in at Lugo and the considerable losses in the 98th Infantry Division caused the Wehrmacht to take the front back to the Laura position on the Santerno River. On April 10, on the extreme southern edge of the attack front, the Italian combat group Friuli , the Jewish Brigade and troops of the Polish II Corps advanced in vain against the section of the front held by the 1st and 4th Paratrooper Divisions. At the end of the day, the 8th Army had succeeded in building a two to four kilometer deep bridgehead on a 30 km long front. A little more than 24 hours after the start of Operation Buckland, the 42nd Jäger Divisions, 362nd and 98th Infantry Divisions on the left and central defense area had recorded around 2,200 casualties, mainly prisoners.

On April 11, troops of the British 56th Infantry Division landed southeast of Argenta, while the Italian Combat Group Cremona advanced on Strada Statale 16 Adriatica west of Alfonsine against the German positions. In the middle range attack succeeded Indians and New Zealanders at Massa Lombarda , despite the counter-attack of some Tiger I heavy tank battalion to break the Santerno in the second German line of defense 504th To the south of it, the 278th Volksgrenadier and 1st Parachute Division had to retreat behind the Santerno, while the Jewish Brigade and the Italian combat group Friuli crossed the Senio. On the 12th the momentum of the Allied attack slackened somewhat. On the Reno, the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, which had come to the rescue, and some battalions of the X MAS offered heavy resistance with heavy losses. With the British 78th Infantry Division, a fresh division was thrown to the front north of Lugo, which was defended in this section by the heavy tank destroyer division 525. With the use of reserves, the German army command tried to slow down the advance of the Allies in order to gain time for the introduction of larger reserves behind the Paula position on the Sillaro river. A counterattack by the 26th Panzer Division with which the Allies should be thrown back behind the Santerno failed, and on the evening of April 12th they were forced to retreat to the starting positions. On the same day, Massa Lombarda fell into the hands of the Allies, while the German paratroopers were able to counterattack the advance in the southern section of the attack. The attack by the 5th US Army in the Apennines planned for April 12 had to be postponed due to poor visibility and the resulting lack of air support.

On April 13, the Allies attacked Argenta, which was defended by the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. In the attack, German tanks destroyed numerous Fantails and caused high losses in the attacking British 56th Infantry Division. At the same time, the remnants of the 42nd Jäger Division defended the area south of Argenta at the strategically important bridge over the Reno near Bastia, so that the advance of the Allies in the Argenta gap slowed. The delay at Argenta caused the British to move the British 78th Infantry Division, which had replaced the Indian 8th Infantry Division, also on Argenta. While the Italian battle group Cremona managed to cross the Santerno south of the British 56th Infantry Division, the 362nd Infantry Division launched a counterattack near Massa Lombarda with assault guns , smoke cannons and supported by panthers from the 26th Panzer Division. To the south of it the Polish II Corps managed to advance to the outskirts of Imola . In the hilly terrain south of Imola, the Italians of the Friuli and Folgore combat groups advanced on the position of the Laura, which the 1st and 4th Paratrooper Divisions had defended.

Operation Craftsman begins

On the morning of April 14th, after a two-day delay due to weather conditions, the 5th US Army attacked the US Army in the Apennines southwest of Bologna with Operation Craftsman . After preparatory air strikes against the German lines in the Rocca di Roffeno, Monte Pigna area, General Truscott and IV Corps went on the attack. Almost 400 guns opened fire on Rocca di Roffeno, the cornerstone of the German defense. After half an hour of barrage, the 10th US Mountain Division attacked the height held by the 334th Infantry Division , which was taken in the afternoon after heavy losses. To the east of it went the 1st US Panzer Division in the Renotal, which was defended by the 94th Infantry Division . In the area of the 2nd US Corps, the South African 6th Panzer Division groped its way forward to take better positions for the next day. On the extreme left wing of the 5th Army, the troops of the Brazilian Expeditionary Corps attacked Montese, held by the 114th Jäger Division , and forced the defenders to retreat after heavy fighting in the afternoon. Meanwhile, Allied air forces bombed the positions of the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division at Montepastore and Vignola, southwest of Sasso Marconi . On the same day the British 8th Army managed to cross the Reno in the right attack area between Reno and the Via Emilia and advance towards Argenta, while the New Zealanders crossed the Sillaro and built a bridgehead on the western bank of the Sillaro. In the southern section of the 8th Army's attack, Polish troops entered the city of Imola, which had been evacuated by the Wehrmacht. After analyzing the situation, Vietinghoff asked for permission to withdraw, which Hitler refused.

On April 15, the first units of the 8th Army reached the hamlet of Bastia south of Argenta, while the New Zealand 2nd Infantry Division crossed the Sillaro during the day and forced the 278th Volksgrenadier Division to retreat by evening. The troops of the Polish II Corps also managed to cross the Sillaro, which then advanced towards Medicina . In the Sillaro Valley south of Castel San Pietro Terme , the German paratroopers offered fierce resistance against the attacking Italian combat group Friuli. In the area of the 5th US Army, the IV. Corps continued its attack and occupied Vergato in the Reno Valley after a fierce house-to-house fight . To the east of the Reno Valley, the II. US Corps also launched an attack after preparatory air strikes on the German defensive positions. At nightfall, the 8th Mountain Division and the 94th Infantry Division in the Reno Valley area had already used up their reserves without stopping the attack by the Americans.

On April 16, the decisive battle for the Argenta, held by the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, began. After heavy fighting, the British 56th Infantry Division succeeded in enclosing Argenta from three sides in the evening. The 26th Panzer Division was moved to Argenta for reinforcement. At the same time the Allies began to prepare for the complete enclosure of the small town. In the evening, Gurkhas of the Indian 10th Infantry Division were able to take the Medicina southwest of Argenta, which was held by the 4th Parachute Division, while the Poles advanced along the Via Emilia towards Castel San Pietro Terme. The Italians of Kampfgruppe Friuli, on the other hand, had been stopped south of it by counter attacks by the 1st Paratrooper Division. In the area of the 5th Army, the IV Corps continued its attacks in the foothills of the Apennines west of the Reno.

On April 17th, the British V Corps captured the hard-fought town of Argenta. Heavy fighting between German paratroopers and the Polish II. Corps broke out at the anna position at Torrente Gaiana west of Castel San Pietro Terme. In the Apennines the Germans threw their last reserves against the advancing IV. US Corps, but were able to slow down the attack but not stop it. After taking Argenta, the Allies managed to advance on April 18, despite the continued German resistance and German counterattacks. To the west of the SS 16, however, the Allied attacks were stopped by the 42nd Jäger Division. To strengthen the section north of Argenta, reserves of the 98th Infantry Division and the 26th Panzer Division were moved to San Nicolò Ferrarese, southeast of Ferrara . The 8th Army, for its part, reinforced its attack peaks with the British 6th Panzer Division. At Torrente Gaiana, after intensive artillery preparation in the last large-scale attack of the Italian campaign, the New Zealanders of the 2nd Division managed to break into the Paula position, which was defended by German paratroopers, and to advance 3 km. The south bordering Poles of II Corps and the Italians of Kampfgruppe Friuli also advanced despite the fierce resistance of the paratroopers. In the Apennines, the 5th US Army approached the edge of the Po Valley. The tops of the 2nd US Corps reached Pianoro in the Savena Valley in the evening and were thus only about 10 km from the outskirts of Bologna. The IV. US Corps, advancing to the west of it, also continued the advance, so despite the fierce resistance of the 334th Infantry Division, the heads of the 1st US Panzer Division reached the Samoggia Valley, northwest of the Reno Valley, near Savigno . East of the Reno, the Allies encountered less resistance, as the Germans were already beginning to withdraw here.

With the fall of Portomaggiore, defending by the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, 25 km south-east of Ferrara on the evening of April 19 by the British 78th Infantry Division, the breakthrough through the German defense lines at Argenta was successfully brought to an end. The German LXXVI. Despite the deployment of five divisions, Panzer Corps did not succeed in stopping the advance of the British 8th Army on Ferrara and the Po. On the same evening, the last bitter resistance of the German paratroopers collapsed at the Paula position on Torrente Gaiana. Even a counterattack brought forward by the 278th People's Grenadier Division, supported by a few tigers from the 504 heavy Panzer Division, could no longer stop the advance of the Indian 10th Infantry Division to Budrio . Only on the extreme left wing of the 8th Army were parts of the 1st Parachute Division in the hilly landscape of the Apennines still resisting the attacking Polish II Corps and the Italian combat groups Friuli and Folgore. In the attack area of the 5th US Army, the 10th US Mountain Division and the first US troops reached the southern edge of the Po Valley on the same day.

Collapse of the German front

In view of the increasingly hopeless situation, Colonel-General Vietinghoff gave the order for a general withdrawal from the Bologna area on April 20 from his headquarters in Recoaro . In doing so, he defied the instructions from Berlin, which forced him to endure, with the hope of avoiding the complete annihilation of Army Group C. The following withdrawal of the Wehrmacht to the north took place in a disorderly manner, for the most part without connections to the units and under pressure from the advancing Allies. To create even more confusion behind the German lines, Italian paratroopers from the Nembo paratrooper division south of the Po near Mirandola and Sant'Agostino were deployed on April 20 with Operation Herring . The latter were supposed to slow down the German withdrawal with groups of the Resistance. On the same day, troops of the British 8th Army crossed the Idice, encountering only sporadic resistance. The Germans had largely renounced the defense of the so-called Genghis Khan position.

The withdrawal order had the consequence that the previously relatively calm front on the Tyrrhenian coast also began to move and the German and national-republican troops lying there began to withdraw to the north.

On April 21, the Allies advanced along the SS 16 towards Ferrara and east of it on the Volano di Po, an arm of the Po. On the Adriatic coast, too, the front started moving again, Comacchio was liberated after the 162nd (Turkm.) Infantry Division had moved north. Due to the few crossings on the Idice, the advance slowed there, which was repeatedly held back by German rear guards who were supposed to cover the withdrawal of their own troops. At 6 o'clock in the morning troops of the Polish II Corps entered Bologna, followed by Italians from the Friuli combat group. On the same day, the New Zealanders bypassed Bologna in the north and met with units of the 5th US Army. While the Brazilian expeditionary force was advancing on the left wing of the attack in the Panaro valley, the 1st US Panzer Division also reached the SS 9 on the afternoon of April 21st. At this point, the 10th US Mountain Division was already in pursuit of those flowing back to the Po German troops picked up and the tops of the division crossed the Panaro and occupied Bastiglia northwest of Modena.

On April 22nd, the British 78th Infantry Division and the Indian 8th Infantry Division reached the outskirts of Ferrara. At Finale Emilia, backflowing German units built up at the Panaro Bridge, fighting fierce battles with the South African 6th Panzer Division and the 88th US Infantry Division, which lasted until the next day. Large parts of the 65th and 305th Infantry Divisions were wiped out and destroyed. On the evening of the 22nd, the peaks of the 10th US Mountain Division reached the southern bank of the Po at San Benedetto Po . The advance of the Allies was stopped again and again by pockets of German resistance in the numerous farms on the Po Valley. In the early morning of April 23, the Germans blew up the Po bridge at San Benedetto Po. The 10th US Mountain Division managed to cross the Po in spite of the German defensive fire and to build the first Allied bridgehead on the northern bank of the Po. Around noon troops of the Indian 8th Infantry Division, supported by the Resistance, liberated the city of Ferrara, while another part of the division circumvented the city and advanced as far as the Po. Northwest of Ferrara, the advance at the Panaro Bridge near Bondeno was stopped by German rear guards.

The all-important meeting between Heinrich von Vietinghoff, Karl Wolff, Rudolf Rahn and Franz Hofer regarding the armistice negotiations with the Allies took place in the headquarters of the Commander-in-Chief Southwest, which is also the headquarters of Army Group C in Recoaro . As early as February, Wolff had been negotiating with middlemen in Operation Sunrise, exploring the ground for an armistice with the Allies in Italy. The collapse of the German front now forced a decision, and in the early hours of April 23rd an agreement was reached to send emissaries.

On the night of April 23rd to 24th , the remains of the 1st and 4th Parachute Divisions and the 278th Volksgrenadier Division crossed the Po near Felonica and Sermide , some swimming, some with smaller boats. On the 24th, paratroopers deployed as rearguards cleared the last bridgehead on the southern bank of the Po.

April 25th heralded the final phase of the German occupation of Italy. On that day, not only did the organized German defense collapse, but the Resistancea called for a general armed uprising. On the Adriatic coast, the allied forces advanced to the mouth of the Po. By April 25, practically six German divisions had been wiped out, the rest of them had lost much of their fighting power and lost almost all heavy weapons and vehicles. Upon reaching the Po, the British 8th Army advanced to northeastern Italy, while the 5th US Army advanced with the II Corps via Verona towards Brenner. The IV. US Corps advanced in three separate attack peaks on Milan, Piacenza and Genoa. On the 26th, the US troops liberated Verona, two days later the Allies were in Genoa, Milan, Vicenza and Venice . The partial surrender of all troops under the command of the Commander-in-Chief Southwest was signed on April 29 at the Palace of Caserta and came into effect on May 2 at 12:00 PM Greenwich Mean Time . At this time, the US troops were in the Valsugana east and in the Adige Valley south of Trento .

Timetable

- 5th-8th February 1945

- Operation Fourth Term , localized operation of the 5th US Army on the Tyrrhenian coast near Massa

- 1st - 3rd April 1945

- Operation Roast , a localized operation by the British 8th Army on the far right of the attack in the Valli di Comacchio area

- April 5, 1945

- Operation Second Wind , diversionary attack by the 92nd US ID on the Tyrrhenian coast on Massa and Carrara

- April 9, 1945

- Operation Buckland , attack by the British 8th Army on the German line of defense at Irmgard am Senio, start of the spring offensive on the right-hand attack sector

- April 14, 1945

- Operation Craftsman , attack by the 5th US Army in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines, beginning of the spring offensive on the left-hand attack sector

- April 19, 1945

- 10th US Mountain Division is the first unit of the 5th US Army to reach the Via Emilia and thus the Po plain

- April 20, 1945

- Colonel-General Vietinghoff disregards Hitler's order, which obliges him to hold out, and orders Army Group C to retreat towards the Alpine fortress.

- April 21, 1945

- Liberation of Bologna

- April 23, 1945

- Liberation of Ferrara.

- April 24, 1945

- The last German rearguards cross the Po

- April 25, 1945

- The Resistance calls for a general uprising

- 25-26 April 1945

- Verona was liberated on the night of April 25th to 26th, 1945.

- April 26, 1945

- Liberation of Genoa through the Resistance

- April 28, 1945

- Benito Mussolini , who had been on the run the day before and was intercepted by the Resistance, is executed by order of the CNL .

- US units arrive in Milan

- April 29, 1945

- Emissaries of Mayor Southwest Vietinghoff and the highest SS and police leader in Italy Karl Wolff, who also negotiates on behalf of the RSI, which is not recognized by the Allies, sign the surrender of the troops under them in Caserta.

- May 1, 1945

- Units of the Yugoslav People's Liberation Army arrive in Trieste .

- May 2, 1945

- The surrender signed on April 29 comes into effect.

- May 3, 1945

- Units of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force arrive in Turin

- May 4, 1945

- US units reach the burner .

War crimes

On their retreat northwards, the dispersed troops of Army Group C committed numerous end- phase crimes , in some cases even after the surrender came into force. Between April 23 and May 6, the remnants of the 1st Paratrooper Division surrendered in Valsugana on May 5, there were attacks by German troops in over 270 cases with one or more deaths. In total, more than 1700 victims were to be mourned during the period. Most of the victims, over 840, were in Veneto . In Piedmont there were over 280, in Friuli-Venezia Giulia just under 220, in Lombardy over 190 and in Trentino-South Tyrol just under 170 deaths.

The German troops harassed by the Allies, some of which were also exposed to attacks by the Resistance, carried out the attacks under great time pressure. Often as an act of revenge against alleged partisan attacks or because the population was suspected of working with the Resistance. In a dynamic that has been pursued by the Germans since the occupation of Italy in September 1943. Most of the victims were picked indiscriminately from the population, even if the proportion of female victims with 9.8% underlines that the male population was predominantly exposed to the excesses. About a third of the cases had no connection whatsoever with the resistance and were pure excesses of violence, which were often indiscriminately and with extreme brutality.

The massacre of San Martino di Lupari north of Padua on April 29, 1945 by members of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division claimed the most victims with 125 dead . The last massacre on Italian soil was carried out three days after the surrender of Army Group C on May 5, 1945 in Somplago, a district of Cavazzo Carnico in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, in which four men were carried out by members of the 24th Waffen-Berg- (Karstjäger- ) Division of the SS were killed.

literature

- Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Mattioli 1885, Fidenza 2011 ISBN 978-88-6261-198-5 .

- Carlo Gentile : Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS in Partisan War: Italy 1943–1945. Schöningh, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 978-3-506-76520-8 . (Cologne, Univ., Diss., 2008.)

- Dominick Graham, Shelford Bidwell: La battaglia d'Italia 1943–1945. Rizzoli, Milan 1989, ISBN 88-17-33369-7 .

- William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. Naval & Military Press, Uckfield 2004, ISBN 1-84574-072-6 .

- Federico Melotti: 13 giorni di sangue. L'Italia settentrionale e il Veneto, 23 April – 6 maggio 1945. In: Gianluca Fulvetti , Paolo Pezzino (ed.): Zone di guerra, geografie di sangue: L'atlante delle stragi naziste e fasciste in Italia (1943–1945) . Il Mulino, Bologna 2016, ISBN 978-88-15-26788-7 .

- Tommaso Piffer: Gli Alleati e la Resistenza italiana. Il Mulino, Bologna 2010 ISBN 978-88-15-13335-9 .

- Mario Puddu: Guerra in Italia 1943–1945. Tipografia Artistica Nardini, Rome 1965.

- Gabriele Ronchetti: La linea gotica. I luoghi dell'ultimo fronte di guerra in Italia. Mattioli 1885, Faenza 2018, ISBN 978-88-6261-651-5 .

- Gilbert Alan Shepperd: La campagna d'Italia 1943-1945. Garzanti, Milan 1970.

- Luca Valente: Dieci giorni di guerra. April 22 – May 2, 1945: La ritirata tedesca e l'inseguimento degli Alleati in Veneto e Trentino. Cierre Edizioni, Sommacampagna 2018, ISBN 978-88-8314-344-1 .

Individual evidence

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. p. 230.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. p. 236.

- ↑ a b Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. P. 391.

- ^ Gabriele Ronchetti: La linea gotica. I luoghi dell'ultimo fronte di guerra in Italia. P. 32.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 33-35.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 197-199.

- ^ Dominick Graham, Shelford Bidwell: La battaglia d'Italia 1943–1945. Pp. 412-413.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. P. 210.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 202-203.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. P. 62.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 206-207.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. p. 200.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 203-204.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 221-224.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 224-228.

- ^ Dominick Graham, Shelford Bidwell: La battaglia d'Italia 1943–1945. Pp. 415-421.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 228-229.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 229-230.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 231-232.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 36-39.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 232-233, 236.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. P. 49.

- ↑ a b Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. P. 60.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 233-236.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. p. 237.

- ^ Dominick Graham, Shelford Bidwell: La battaglia d'Italia 1943–1945. Pp. 422-423.

- ↑ Tommaso Piffer: Gli Alleati e la Resistenza italiana. Pp. 201-206.

- ^ William Jackson: The Mediterranean and Middle East: Volume VI Victory in the Mediterranean. Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. pp. 210-211.

- ↑ Tommaso Piffer: Gli Alleati e la Resistenza italiana. P. 213.

- ↑ Tommaso Piffer: Gli Alleati e la Resistenza italiana. Pp. 219-220.

- ↑ Tommaso Piffer: Gli Alleati e la Resistenza italiana. Pp. 225-228.

- ^ Robin Kay: Italy Volume II: From Cassino to Trieste , The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945. Edition, Historical Publications Branch, Wellington 1967, p. 600.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 84-93.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 96-109.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 122-127.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 136-137.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 143-157.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 164-169.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 179-183.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 190-196.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 204-211.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 219-238.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 279-283.

- ↑ Luca Valente: Dieci giorni di guerra: 22 April-2 maggio 1945: La ritirata tedesca e l'inseguimento degli Alleati in Veneto e Trentino. Pp. 69-72.

- ↑ Marco Belogi, Daniele Guglielmi: Spring 1945 on the Italian front: a 25 Day Atlas from the Apennines to the Po River. Primavera 1945 sul fronte italiano: Atlante dei 25 giorni dall'Appennino al fiume Po. Pp. 306-323.

- ↑ Federico Melotti: 13 giorni di sangue. L'Italia settentrionale e il Veneto, 23 April-6 maggio 1945. In: Gianluca Fulvetti , Paolo Pezzino (Eds.): Zone di guerra, geografie di sangue: L'atlante delle stragi naziste e fasciste in Italia (1943–1945) . Il Mulino, Bologna 2016 ISBN 978-88-15-26788-7 p. 282.

- ↑ Federico Melotti: 13 giorni di sangue. L'Italia settentrionale e il Veneto, 23 April-6 maggio 1945. pp. 284–285.

- ^ Somplago, Cavazzo Carnico, May 5th, 1945 (Udine - Friuli-Venezia Giulia). In: straginazifasciste.it. Retrieved January 20, 2020 (Italian).