Hermannstrasse (Berlin-Neukölln)

| Hermannstrasse | |

|---|---|

| Street in Berlin | |

| Hermannstrasse and Boddinstrasse | |

| Basic data | |

| place | Berlin |

| District | Neukölln |

| Created | around 1875 |

| Hist. Names |

Road to Britz (1859 to 1874) |

| Connecting roads |

Kottbusser Damm (north) , Britzer Damm (south) |

| Cross streets |

(Selection) Hasenheide , Karl-Marx-Strasse , Columbiadamm , Flughafenstrasse , Silbersteinstrasse , Mariendorfer Weg |

| Places | Hermannplatz |

| Buildings | Old churchyard of the St. Jacobi parish, Hermannshof, churchyard of the Emmaus parish, churchyard of the St. Michael parish, churchyard of the St. Thomas parish I, churchyard of the St. Thomas parish II, cemetery V of the Jerusalem and New Church, New Cemetery of the Luisenstadtgemeinde, New Cemetery of the St. Jacobi Congregation |

| use | |

| User groups | Pedestrian traffic , bicycle traffic , car traffic , public transport |

| Technical specifications | |

| Street length | 2490 meters |

The Hermann road leads in Berlin district of Neukölln from Hermannplatz approximately 2.6 kilometers to the south and continues to the corner Juliusstraße or after the new highway entrance of the Berlin city ring as Britzer Damm continued. With the continuation as Buckower Damm in the direction of Großziethen , the street is one of the historical and larger Berlin north-south connections. Several neighborhoods and churchyards determine the image and structure of the densely built-up residential and commercial street. In making an investment in 1900 as a civic designed quarters, two are the neighborhoods to the deprived areas of Berlin.

Course on the Teltowhang

In the first part, Hermannstraße runs parallel to Volkspark Hasenheide , only separated by a small side street . On this gently rising section, it leads from the Berlin glacial valley up to the Teltowhang , a flat, undulating plateau that rises on average around 15 meters above the level of central Berlin. The Teltowhang changes its direction in the Hasenheide from east to south, so that Hermannstraße at the corner of Flughafenstraße reaches the level of the Teltowplatte and continues on its slope.

The parallel Neukölln Magistrale, on the other hand, Karl-Marx-Straße , lies in the lower Spree valley level with the result that all cross connections between the two main streets are sloping. This geological condition can be seen particularly clearly on Rollbergstrasse, which leads down from the former Rollberg, which has been concreted over. The gradient is - by Berlin standards - very pronounced: the residents of the Rollbergsiedlung facing Hermannstrasse used to ironically refer to the rather simple dwellings in this working-class area as their “ chalets in the Rixdorf Alps ”.

Separated by the Kiez on the Schillerpromenade and the Werner-Seelenbinder-Sportpark (formerly: Sportpark Neukölln ), Hermannstraße runs from Flughafenstraße parallel to the Tempelhof airport , which connects to the Hasenheide park to the south. In the area from the Leinestrasse underground station to the south, Hermannstrasse passes six different churchyards , each of which extends as a narrow strip to the west to the airport or to the east to Karl-Marx-Strasse.

Here, the closed St. Thomas Cemetery to Schillerpromenade neighborhood (in short: Schillerkiez ) to the airport to traffic from, resulting in a similar insularity of Kiez as in the Schöneberg Red Island leads. The adjoining Warthekiez , the southern border of which is the St. Jacobi churchyard, is even more isolated . The following quarter around Emser Strasse, which accompanies Hermannstrasse to the S-Bahn route , is a little more open again.

Two name cartridges

The previously unnamed street was renamed Straße nach Britz in 1859 . From 1875 it was gradually renamed from the north to Hermannstraße and since 1899 it has had its current name along its entire length. There is an official and an unofficial version of the name.

Arminius

The street is officially named after Hermann the Cheruscan , the common name form of the Cheruscan prince Arminius in 19th century Germany , which was characterized by patriotism and nationalism . The historical Arminius had defeated the Roman legions under Varus in the battle in the Teutoburg Forest in the year 9 . Only the Latinized form of his name has survived from him, but the transfer with the name Hermann is probably not historical. The mythical transfigured and excessive Arminius was when Hermann an important identification figure of the young German Empire , for which the 1875 completed Hermann Monument in Detmold is the most famous product.

Hermann Boddin

For almost the entire imperial period , the dominant figure in local politics in Rixdorf , which was called Neukölln from 1912 and was incorporated into Berlin in 1920, was the mayor and later mayor Hermann Boddin (1844–1907). A side street off Hermannstrasse, Boddinstrasse, is named after him. There is also Boddinplatz, the Boddinstraße underground station, the Hermann Boddin primary school, an honorary grave in the state's own Britz cemetery and a memorial plaque. The patriarchal dominance with which Boddin ruled "his" suburban community led among the Rixdorfers to the assumption that the naming of the much larger, more important Hermannstrasse - for the expansion of which he had campaigned massively since he took office in 1874 - in its ambiguity of Boddin was at least not disliked to be seen. Meyer-Kronthaler and Kramer report on this: “[…] to this day it has not been completely clarified which Hermann has been the namesake since then. [...] If you believe the files of the district office, Boddin is meant, although as early as 1924 there was a denial on the table that Boddin's brother-in-law published. "

On Boddin's initiative, the renaming of Rixdorf, which is badly acclaimed as an entertainment district ( Gassenhauer : In Rixdorf is music ), goes back to Neukölln, which Kaiser Wilhelm II approved only after the death of the mayor. The renaming should increase the attraction of the new quarter on the Schillerpromenade, for example, for higher earners. As mayor, Boddin had obtained the building permit, the quarter was not least built on his initiative - and he is said to have benefited financially not insignificantly from these buildings.

history

From the early days of Hermannstrasse

Historic junction at the Rollkrug

Detail of a painting by Wilhelm Barth from 1834

Long before Hermannstrasse got its name, its first building, the historic Rollkrug , stood at its northern starting point , which at that time was still far outside the Berlin city limits south of the Cottbusser Tor . The horse changing station was between quarry lands and meadows at the crossroads that form Hermannplatz . At that time the west-south-east connection from Hallescher Tor via Rixdorf to Wusterhausen passed here , which led through the Hasenheide and over the Schlächterwiesen to the old Wusterhausener Chaussee . From Hermannplatz, this connection is largely identical to Bundesstraße 179 , which was built in 1849 by the Wusterhausen-Lübbener Chausseebau-Aktiengesellschaft as a paved art road ( Chaussee ) and, according to its name, ran via Wusterhausen to Lübben in the Spreewald . As far as the Berlin border, this street is represented by: Hasenheide , Karl-Marx-Strasse , Buschkrugallee, Rudower Chaussee, Neuköllner Strasse and Waltersdorfer Chaussee. On the other hand, the old north-south connection crossed from the Kottbusser Tor to Mittenwalde , which began as Dresdener Heerstraße (today: Kottbusser Damm ) and continued in today's Hermannstraße, Britzer Damm, etc. The rollkrug existed until 1907 and was replaced by a commercial building after its demolition. In the first few years the building was home to one of the most prominent Berlin cinemas.

Four windmills on the road

In the second half of the 19th century there were various windmills along Hermannstrasse . There was the Hänsche mill , the Rohleder'sche on the corner of Leykestrasse and the Fuhrmann'sche just a few steps further south opposite the St. Thomas churchyard - all of them post mills . The only Dutch mill on the street crowned the Rollberg between 1860 and 1872; The Jungfernmühle came from Potsdam and was then moved to Buckow at Goldammerstrasse 34, where it is the only one of the former Hermannstrasse mills that has been preserved.

Hermannshof

From 1904 to 1905 was built on the Hermann Straße 48 in the second backyard of Hermannshof . This had become necessary because there were previously no commercial yards, most of the residents worked outside the neighborhood. The commercial building has had this name since it was built. In contrast to the Rixdorf commercial rear buildings typical of the time, the Hermannshof became just as well known as the Elisabeth- or Oranienhof in Kreuzberg , which means it was given an individual name based on the location. The outside of the factory building also stands out, for example through the large, detailed windows that create light-filled rooms. Decorative shapes and name (still preserved in the original) emphasize the central axis and portal in a way that is unusual for commercial buildings. Clubs, shared apartments and art projects are housed in the listed building; it no longer serves as an industrial building. In addition to the Hermannshof , the Ottilenhof was also built on the property at Hermannstrasse 56/57, which was fundamentally renovated in 2000.

Churchyards and slave labor

In addition to the almost uninterrupted row of residential and commercial buildings, several cemeteries determine the image of Hermannstrasse, in whose area a unique collection of eight cemeteries can be found in a very small space.

Unique concentration

The founding of the cemeteries goes back mainly to the communities in the former Luisenstadt district . Therefore, the communities are not located in Neukölln, but to a large extent in Kreuzberg. After the rapid development measures of the Wilhelminian era (the population of old Berlin, today's core area of the city, quadrupled from 500,000 in 1861 to two million in 1910), the Berlin communities in the narrow city could no longer find space for their graves and moved the cemeteries the gates of the city. In the fields and meadows in front of Cottbusser Tor, there was free and inexpensive space, which was also easily accessible via the Hermannstraße road. The church yards were built on both sides of the street, with the facilities running to the east in the direction of Karl-Marx-Straße showing the sloping incline of the former Rollberge. Half of the eight cemeteries are protected as garden monuments .

Even before the city's big building boom, the Protestant St. Jacobi congregation laid the first of the Hermannstrasse cemeteries in the immediate vicinity of the Rollkrug in 1852. This only cemetery in the lower first part of the street is in the area of Karl-Marx-Straße. Unlike the narrow, transverse churchyard strips in the middle part of the street, the churchyard runs parallel to the street for around one hundred meters and provides one of its few green and open passages opposite the dense row of houses in the Hermannstrasse district .

The concentration is in the middle of the street around the Leinestraße underground station . Between the Oker Strasse and Emser Strasse, six cemeteries were built here in the sixties and seventies of the 19th century, also narrow and vertical. The street front of these burial sites is only very short, but they extend into the depths to over 600 meters. All of these cemeteries are characterized by a long central avenue, which is loosened up by a different number of roundabouts and cross paths. Only in the upper area can you find some hereditary burial sites on the side walls, which is due to the population structure. The chapels and administration buildings are mostly in the area of the entrance gate, the roundels occasionally have sculptures that optically interrupt the depth of the avenues.

At the southern end of Hermannstrasse there is a cemetery with the Emmauskirchhof, parallel to the new motorway tunnel, which is also perpendicular to the street and can hardly loosen up the building.

Confusing numbering of Hermannstrasse and inconsistent designation of the cemeteries

With the beginning of the development, the Rixdorf administration had determined the numbering of the houses according to the horseshoe principle. This Berlin numbering goes back to the fact that the right side (in this case the western side) seen from Schlossplatz (in the city center) has consecutive numbers, then the east side back in the opposite direction to the highest house number. The parcels in Hermannstrasse were not counted alternately from street side to street side according to even and odd house numbers. The count began here with number 1 on the west side at Hermannplatz / Hasenheide and already reached number 171 in the 1880s. Many free parcels in between were shown in the address book as construction sites. The cemeteries were initially numbered 73 (Jerusalem and New Church), 77 (Jakobi Church) and 168. In the following overview, they were sorted from north to south according to their location. It should be noted that the cemeteries in the middle area and in particular the two cemeteries of the St. Thomas parish are exactly opposite each other despite the completely different numbers.

In 1900, the parcel numbers on Hermannstrasse already extended to number 258, so they were reassigned with the increasing development, the cemeteries are now as follows: 79–83 St. Thomas, 84–90 Jerusalemer und Neue Kirche, 99– 105 Jacobi parish, 129–137 Emmaus parish, 186–190 Luisen-Kirchhof and 191–195 St. Michael. The designation of the church yards remains in the traditional form in the 21st century. Above the entrance portal is the old lettering "Friedhof der St. Michael Gemeinde", a plaque on the portal names the churchyard "Alter Friedhof der Kath. Gemeinde St. Michael" and a historical plaque 20 meters from the portal bears the inscription "Kirchhof der Catholic St. Michael Congregation ”. The following orientation corresponds to the naming of the respective municipalities.

Eight cemeteries in detail

Northern area, a churchyard

Old churchyard of the St. Jacobi community , Hermannstrasse 234–253 (east side) / Karl-Marx-Strasse 4–10

In the lower part of the street just behind Hermannplatz is the old churchyard of the St. Jacobi parish . The garden monument between Hermannstrasse and Karl-Marx-Strasse had the St. Jacobi community laid out as early as 1852. It is a largely geometric layout with avenues and individual trees, especially chestnuts and linden trees . There are no jewelry spaces on the 40,908 m².

There are hereditary burial walls on the cemetery wall and an urn grove was added later in the eastern part of the cemetery . The chapel was built from 1911 to 1912 by the city councilor Reinhold Kiehl as a rectangular plastered building in the ancient Roman style. The wall surfaces were given a structure by putti friezes and pilasters . The vestibule is designed to be open in the central axis, followed by a rectangular main room with a semicircular apse , Tuscan columns on the sides and smaller pilasters and pillars in the choir area . The partially colored windows consist of arched windows that alternate with blinds and square windows above. Together with the administration building, the entrance gate and the adjoining cemetery grille made of metal spears and Tuscan columns as well as a part of the colonnade , the chapel is combined into one assembly that was executed at the same time. After its partial destruction during the war, the St. Jacobi community was able to restore the ensemble shortly after the end of the war.

City councilor Reinhold Kiehl , to whom listed buildings such as the Neukölln Town Hall and the Royal Prussian Building Trade School , which later became the Technical College for Construction from 1914 and today's Carl-Legien-Oberschule in the Leinestrasse at the end of the Schillerpromenade, found his final resting place in 1913 ; the tomb bears the inscription "In memory of the city of Neukölln". In addition to Hermann Boddin, Kiehl, after whom the Kiehlufer on the Neukölln shipping canal was named, is probably the best-known local politician from the Rixdorf period.

The Indologist Albrecht Weber (1825–1901), the painter and graphic artist Franz Skarbina (1849–1910), as well as the fairy tale researcher, Germanist and folklorist Johannes Bolte (1858–1937) were buried here.

Central area, east side, three cemeteries

At the underground station Leinestrasse, order south

Churchyard of the St. Michael Congregation, Hermannstraße 191–195 (east side)

The churchyard of the St. Michael parish was built in several stages between 1863 and 1895 on an area of 21,537 m² geometrically along a central avenue with oaks and linden trees and three roundels. There is a dominant crucifix in the front roundel.

The chapel of the churchyard on the street by an unknown architect in the late romantic style dates from 1884. The facade is made of yellow facing bricks, with the street front being visually divided into three areas. In the gable there is a bell carrier, including a Christ head, and a morgue and an administration building are attached. In 1912 the facade was redesigned and the chapel was expanded. Damage occurred during the Second World War and in 1954 Wilhelm Fahlbusch restored the building. In a niche in the entrance area, an impressive sculpture of the Archangel Michael catches the eye.

The graves of honor in the cemetery are the graves of the two city elders Alfred Rojek and Richard Schönborn, as well as the writer and translator August Scholz .

New churchyard of the Luisenstadtgemeinde , Hermannstrasse 186–190 (east side)

The new churchyard of the Luisenstadtgemeinde dates back to 1865. The 47,996 m² site has a main avenue from which several side avenues branch off as cross paths and is loosened up by four roundels. The planting consists mainly of linden trees.

The chapel from 1958/1959 is the work of architects Paul and Jürgen Emmerich . It is a building with a rectangular base and a monopitch roof , which is designed with clinker bricks and rough plaster, the front surface is glazed. The vestibule has plaster sections on the side walls. The building is used as a morgue.

Churchyard of St. Thomas Parish II , Hermannstrasse 179–185 (east side)

The second churchyard of the St. Thomas parish was built in 1872 opposite the first. The garden monument is 51,635 m² in size and, like all other cemeteries, is geometrically laid out. The center is an avenue of plane trees with four roundabouts and four crossways lined with spruce and lime trees. The border planting is also represented by linden trees, and Taxus hedges also subdivide the areas.

The chapel dates back to 1870, the architect is unknown. It is a brick building with a cross connection. The hall is open to the side and has a broken apse and two-part windows. The interior has a semicircular altar niche and a gallery . The octagonal flower house, which was probably built in the 1920s, is also striking.

Reinhold "Krücke" Habisch (1889–1964), the Berlin original and, as the "inventor" of the legendary four whistles in the Sportpalast waltz, the secret star of many six-day races, has his final resting place here. There is also the grave of the former mayor of Berlin, Robert cell , the grave of the Rixdorf city councilor Gustav Leyke , namesake of the neighboring Leykestrasse, and the communal grave of the city elders Marie and Wilhelm Wagner.

In the churchyard there is also a memorial pavilion and a memorial stone for a forced labor camp, which was located in the churchyard V of the Jerusalem and New Churches at Hermannstrasse 84-90. The memorial stone, which was erected in the churchyard V in 2002, was later (in 2013 at the latest) moved to the churchyard of St. Thomas Parish II (see chapter Forced Laborers of the Church below ).

Central area, west side, three cemeteries, magic shop

At the underground station Leinestrasse, order south

Churchyard of St. Thomas Parish I , Hermannstrasse 79–83 (west side)

The older churchyard of St. Thomas Parish was laid out in 1865. It has a main avenue with plane trees and a roundabout on the area of 65,697 m², another may have been there. The border planting is represented by pyramid poplars . There is no chapel in this churchyard, as the chapel in the second churchyard opposite the municipality is sufficient for both parts of the garden monument. This cemetery has been cleared since the beginning of 2007.

The dancer ( Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy ) and actress ( Fritz Lang's Dr. Mabuse, the player ) Anita Berber , who died in 1928 , was buried here. The grave no longer exists, as the cemetery administration closed the resting place after the occupancy period had expired.

Cemetery V of the Jerusalem and New Churches , Hermannstrasse 84–90 (west side)

The fifth churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Church parishes in Berlin from the years 1870 to 1872 has a central avenue of lime trees with seven cross paths and several roundabouts, the area is 56,024 m².

Louis Arndt laid out the chapel in the years 1899/1900 as a red brick building in the Gothic style. After war damage, it was rebuilt at the end of the war. In 2002 the owner, the Evangelical Parish in Friedrichstadt , left the chapel to a parish of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church for 30 years in return for building maintenance and upkeep. At Easter 2003, the Bishop of the Diocese of Western and Central Europe consecrated the chapel as the cathedral church of St. Tsar Boris the Baptist . The administration building and the gate on Hermannstraße were built in 1873, the architect is unknown. In 1877 the administration building was converted into a morgue by C. Dammeier.

During the last two years of the Second World War, a barrack for slave laborers who had to work in the surrounding cemeteries stood at the west end of the churchyard, just before the former Tempelhof Airport . A memorial plaque was erected at the site of the forced labor camp. In 2002 a memorial stone by the Berlin sculptor Rainer Fest was inaugurated near the Hermannstrasse entrance. The memorial stone was later (in 2013 at the latest) moved to the churchyard of St. Thomas Congregation II , Hermannstrasse 179–185 (see below chapter Forced Laborers of the Church ).

The church yards of St. Thomas I and Jerusalems- and neue Kirche V also served together as the eastern approach lane of the former Tempelhof Airport and for this reason were criss-crossed with rows of beacon masts.

Magic shop , Herrmannstrasse 84–90

There are still barracks on the cemetery area, in one of which the Zauberkönig shop has had its long-term domicile since 1952 . The magician Josef Leichtmann had opened a trade in accessories for magic in Friedrichstrasse in 1884 . The daughter took over the business together with her husband Arthur Kroner, but had to hand it over to an Aryan operator in 1938 because the Leichtmanns and the Kroners were Jews . The former employee Regina Schmidt became the owner.

After the end of World War II and the division of the city into four sectors , Regina Schmidt moved from the eastern part of Berlin to a new location in Neukölln, in one of the quickly erected makeshift buildings. After Schmidt's death, family members took over the business again. From the late 2010s it became known that the church property owners wanted to build new buildings instead of the barracks, operated by a non-profit foundation. So Zauberkönig had to close in the summer of 2018, but was given the opportunity to reopen diagonally across the street on the same street.

"He was a citizen of Rixdorf"

New churchyard of the St. Jacobi community , Hermannstraße 99-105 (west side)

The new churchyard of the St. Jacobi community from 1867 has an area of 74,048 m², a central avenue of linden trees with several roundabouts and five cross paths.

The year of construction and the architect of the asymmetrical chapel in the romantic style are not known. It has a facade made of yellow facing bricks in a cross connection and has a semicircular apse and several flat outbuildings. Damaged in the war, the chapel was rebuilt in 1952.

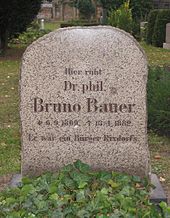

The grave of the theologian Bruno Bauer (1809–1882), whose work Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in Die Deutsche Ideologie (1845/1846) polemically criticized (“Sankt Bruno”), is located in the St. Jacobi churchyard . The gravestone bears the inscription: "He was a citizen of Rixdorf".

In Theodor Fontane's novel Irrungen, Wirrungen (published 1888, set in Berlin around 1880) this cemetery is mentioned in chapter 22. Botho von Rienäcker, the protagonist of this story, visits the grave of the foster mother of his lover Lene Nimptsch. It is interesting that there is still a relic from this time with the resting place of Bruno Bauer, who died in 1882. In the 21st chapter of the novel, the approach is also described in great detail: Via Kreuzberg, you then pass the Hasenheide, the Rollkrug and the overcrowded old churchyard of the St. Jacobi parish , down Hermannstrasse.

Southern area, a churchyard

Churchyard of the Emmaus community , Hermannstrasse 129–137 (west side)

The garden monument Emmauskirchhof of the municipality of the same name from 1888 is located at the southern end of Hermannstrasse shortly before its transition to Britzer Damm, parallel to the new motorway tunnel to the west (see below chapter cyclists ).

The cemetery is both the youngest and, at 128,781 m², the largest cemetery on Hermannstrasse. The builder of the chapel from around 1900 is unknown. Stylistically, the building is to be classified in the transition area between Romanticism and Gothic . It is an irregular building with a red brick facade and gray plastered surfaces that structure the facade as panels and bands. A ridge with a pointed helmet stands on the roof . The interior has three naves, with the central nave being equipped with a cross vault and a semicircular apse. The aisles have pointed barrel vault and are located on the columns Roman figures capitals .

Here is Walter Bromme buried (1885-1943), who in the Golden Twenties popular operettas and hits composed and temporarily as director of in the season 1923/1924 Metropol Theater acted in Behrenstraße. The operettas Brommes ranged from Die Dame im Frack (1919) to Dolly (1924) and Spiel nicht mit der Liebe (1934).

Church slave laborers

In the last years of the 20th century, in connection with the research for the compensation fund for forced laborers, it became known that the churches in Germany had requested a considerable number of forced laborers and employed them throughout Germany during the Second World War . In the summer of 2000, the Berlin-Brandenburg bishop Wolfgang Huber admitted that in the last three years of the war there was a barrack camp for around 100 forced laborers in Berlin in the churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Church at Hermannstrasse 84-90 Bomb victims' burials were used. There were 39 Protestant and three Catholic parishes that supplied themselves with undertakers from the cemetery camp. The churches are also said to have tacitly accepted the murder of the workers' children. With the active support of the top church leadership, this cemetery camp was given a so-called "armament number" and was thus recognized as "important to the war effort". The head of the camp, Gustav Less (a member of the Confessing Church ), was an employee of the Evangelical City Synod Association. The unlawful forced laborers were at the mercy of him as camp managers and the Gestapo, but none of the inmates died under him.

The Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) has made an admission of guilt , and the churches also participated in compensation payments.

Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko, who was abducted from the Ukraine to Berlin at the age of 16 and in 2005 wrote a diary about everyday life and that, describes the horrors and privations under which the predominantly Russian and Ukrainian workers, in the National Socialist ideology " Slavic subhumans", suffered Survival published in camp. It says: “The heavy bombs fell on the cemetery and hurled those previously buried back up […] parts of the body, entrails - everything on the tree - terrible. It was a horror. We ' Eastern workers ' put them back in the graves. But not everyone could bear it, endure it psychologically. "

The forced laborers suffered from constant fear of death because the camp was located directly next to the Tempelhof airport, which was important for the war effort and which was a special destination for the Allied flights . Kudrenko writes: "During the attacks, we sought protection where the alarm surprised us: between the coffins, in the sewer system, in pipes". The barrack camp was bombed several times, and in 1944 it burned down completely in a very short time. The forced laborers were denied refuge in shelters .

Forced laborers between the ages of 53 and 64 were put on a list as "no longer usable due to their physical condition" and were deported to a collection camp. In the camp there was almost certainly no longer any medical care, and there was almost no food here - the result was a high mortality rate. The end of the war freed the survivors in the assembly camp and in the churchyard.

An information column (formerly in the churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Churches ) with eight picture and writing boards lists all participating Berlin parishes. The boards also list the names of the 96 forced laborers, whose names are known. In 2002, also in the churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Churches , a memorial stone by the Berlin sculptor Rainer Fest was inaugurated, which engraved the participating communities on the surface . Fest cut out a layer of the boulder from which the stone was made and divided it into 42 individual parts - each with a name of the parishes involved. As a reminder of their responsibility, each congregation received “their” stone, a responsibility that is combined on the surface of the memorial stone with all names to form the overall responsibility. The memorial stone and the information column were later (2013 at the latest) moved to the churchyard of St. Thomas Parish II in Hermannstrasse 179–185.

traffic

Public transport

The Poststraße Berlin – Mittenwalde– Dresden , which was inaugurated in 1712, led over today's Hermannstraße. The integration of the populous neighborhoods on the street into the Berlin transport network began early on. On June 6, 1885, the city of Rixdorf opened a horse-drawn railway line from Hermannplatz to Hermannstrasse and the corner of Knesebeckstrasse (today: Silbersteinstrasse). The operator was the horse tram of the municipality of Rixdorf, which was already a good two years later in the Great Berlin Horse Railway A.-G. rose. From Wittenau coming metro line U8 leads under the road. The line runs through the Hermannplatz , Boddinstrasse and Leinestrasse subway stations to the Hermannstrasse terminus , which was opened in 1996 and is located around 500 meters before the transition from Hermannstrasse to Britzer Damm. The Ringbahn , which maintains the busy Hermannstraße S-Bahn station here, crosses at the same point .

The Ringbahn has been crossing Hermannstrasse since November 1877. However, the station on Rixdorfer Hermannstrasse was only built in the course of the four-track expansion of the ring line between 1887 and 1910 and opened on February 1, 1899. Hermannstrasse was thus initially connected to the railway network by steam-powered trains, and from 1928 by “ electric S-Bahn ”.

On September 28, 1900, the connection with the Neukölln-Mittenwalder Railway (NME; until 1919: Rixdorf-Mittenwalder Railway ), which received its own passenger platform, took place at Hermannstraße station . After the Second World War, their passenger train traffic lost its importance, on May 1, 1955 it was discontinued in Berlin. The NME is still active in freight transport. S-Bahn traffic at Hermannstrasse station was idle from 1980 to 1993.

→ See also: Bahnhof Berlin Hermannstrasse

Private transport

Car traffic

Despite the excellent integration into the city's local public transport by underground and S-Bahn, Hermannstrasse is not able to cope with the traffic of the densely populated urban area due to its structure; an extension of the street is hardly possible due to the dense development.

The density of individual traffic is no higher than that of streets with similar traffic. Furthermore, the connection to the Berlin city ring with the junction Britzer Damm in 2000 led to a noticeable relief of through traffic to Britz and Buckow. Nevertheless, the traffic continues to flow very slowly through the road and driving through it brings with it a high level of stress for road users . Reasons for this are:

The four lanes and two parking lanes are interrupted by several traffic islands for underground stations and bus stops, where the lane narrows. The high number of side streets only slowly absorbs left and right turns, as the large number of pedestrians in the green phases only allows a few vehicles to pass. The traffic lights follow one another very quickly in some sections. The dense development with blocks of flats and shops means that residents and suppliers very often keep in the second lane or park for a short time. All in all, these factors mean that the drive through Hermannstrasse, especially in rush hour , usually resembles a slalom race. It is almost impossible to evade, because the traffic does not flow much differently on the parallel Karl-Marx-Straße. Due to their island location, the streets of the eastern Kiez areas also lead partly back to Hermannstrasse and, due to the separation by the church yards, do not offer any shortcuts; In addition, all adjoining residential areas are designated as a 30 km / h zone .

This stop-and-go traffic causes a high level of noise pollution and exposure to pollutant concentrations for residents and road users .

Bicycle traffic

The environmentally polluted slalom route has structurally inadequate and narrow bike paths in the lower part between Hermannplatz and Boddinstraße underground station . On the remaining sections of the route, cyclists ride in mixed traffic on the lane. In the Hermannstraße conurbation there is a varied cycle connection to the neighboring districts of Britz , Schöneberg and Kreuzberg , despite the city center location . This very good connection - also with regard to the pavement - leaves out Hermannstraße and runs through the neighborhood right next to Tempelhof Airport to Columbiadamm . Cyclists and pedestrians get on at the places that are closed to car traffic.

Coming from Britz (the Britzer Damm has a cycle path) the route begins at the new Britzer Damm motorway junction. The motorway runs through the 1.7 kilometer long, ultra-modern and so far permanently fault-prone tunnel in the town center Britz from the year 2000 under the western Neukölln residential areas and under the Britzer Damm in the direction of the Neukölln triangle; the junction leads down into the tunnel. After completion, the State of Berlin created an elongated green area with playgrounds and sports fields (Carl-Weder-Park) on the tunnel ceiling, which runs parallel to the Emmauskirchhof garden monument. This elongated strip is easy to drive through for cyclists. At the height of the Mariendorfer Weg you can get to the little-used Eschersheimer Straße via the S-Bahn route into the Oderstraße and thus into the neighborhood area. A two-lane cycle path runs between Oderstrasse and the Neukölln sports park, which has been named after the resistance fighter and successful wrestler Werner Seelenbinder , who was executed in 1944 for several years . The path leads past the renovated ice rink, the following sports buildings and fields as well as the Werner Seelenbinder memorial.

At the western end of the churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Churches , the path meets the field of the former airport and leads in an arc around the field that is not passable for car traffic into the second part of Oderstrasse. Here, parallel to the airport, there is an old cycle path that has burst open many times and is impassable. The entire Oderstraße, which has very little motor vehicle traffic, is available for cycling. At the northern end of Oderstrasse, where motorized traffic has to turn again, a wide cycle and pedestrian path between the Columbiadamm summer pool and the leisure facilities at the Jahnsporthalle leads to Columbiadamm. At the dam there are cycle paths to the west towards Tempelhof and Schöneberg or to the east towards the Boddinstraße underground station , which is connected to Hermannstraße. Cyclists can get down to Hermannplatz via the only cycle path section on Hermannstrasse. The landscape of Hermannplatz can be reached even more beautifully if you cross the Columbiadamm and enter the Volkspark Hasenheide opposite . Optionally, asphalt paths or solid sand paths lead through the park in a north-east direction to Hermannplatz and in a north-west direction to Kreuzberger Südstern .

In March 2019, preliminary planning for a new cycle path was completed, with a protected cycle path being named as the preferred variant. The year 2020 was named for the start of the successively planned construction work. Since the conversion of the parallel Karl-Marx-Straße had already started, the conversion of Hermannstraße is to begin in the southern part further away from it, so as not to burden the detour traffic from Karl-Marx-Straße any further. From May 2020, with the Covid-19 pandemic, several pop-up bike paths were built in the city. This led to a stronger political discourse about a protected cycle path in Hermannstrasse and several demonstrations for an early, safe cycle infrastructure. In June, the district assembly voted to set up a pop-up cycle path on a section of Hermannstrasse from August 2020. The CDU spoke out against such a cycle path.

Structural development and neighborhoods

The social structure of the commercial and residential street is determined by small commercial enterprises, a large number of shops, including numerous Turkish markets and bakeries, snack bars, betting shops and game libraries, as well as houses and apartment blocks, some of which date from the Wilhelminian era. On the east side of Hermannstrasse 214-216, the modern office and business center Kindl-Boulevard was built in 1996 , which extends deep into the area of the former Rollberge. In addition to shops, restaurants, the Rollberg cinemas and exhibition rooms, the Neukölln Job Center and the Neukölln Women’s Business Center will find space here , in particular for women starting up a business . The center, in which a Munich construction company had invested 400 million euros, contrasts with the other business structure of the street, which is largely characterized by retailers and low-cost shops with frequent changes of ownership.

Hermannstrasse is accompanied by three neighborhoods in the entire western part . In the lower part of the Hermannstraßenkiez , which is bordered to the west by Volkspark Hasenheide , north by Straße Hasenheide and south by Columbiadamm. Beyond Columbiadamm, the Volkspark is joined by the grounds of the former Tempelhof airport and the Neukölln sports park , which delimit the neighborhoods to the south, the Schillerkiez , the Warthekiez and the district on Emser Straße, to the west.

Hermannstraßenkiez

The Hermannstraßenkiez around Wissmannstrasse and Karlsgartenstrasse at Volkspark Hasenheide was created in the early days as an entertainment district with beer gardens , theaters and dance halls. In the 1920s, Hermannstrasse developed from this area into an important "cinema mile" and remained so until the great cinema deaths in the 1960s. The Kiez became a purely residential area with a few smaller garden bars. The Workshop of Cultures in Wissmannstrasse provides a diverse flair, which attracts visitors with numerous exhibitions and sees itself as a dialogue and cooperation partner of the migrant scene in Berlin and wants to be a forum for a multicultural civil society. The Workshop of Cultures has existed since October 22, 1993 in the historic building of the former Lion Brewery - Bohemian Brewery, which is well worth seeing .

Another piece of the old entertainment district can be found with the Neues Off cinema directly at Hermannstrasse 20, which was founded in 1919 as a theater and vaudeville and has been used as a cinema since 1926 under the name Rixi (Rixdorfer Lichtspiele). Despite the restoration, the house still exudes a lot of charm from bygone times - in the foyer, for example, a red Sarotti counter in the design of the 1950s catches the eye. The cinema is part of a four-storey residential building and one of the last old movie theaters that could still survive in Berlin.

The Stern Palace Cinema was one of the smaller movie theaters of the interwar period. It was built in 1925/1926 by Max Bischoff and Heinrich Möller and the engineer Gustav Heun by converting a burnt-out rear hall at Hermannstraße 49. The wide entrance area consisted of the renovated ground floor and first floor of the residential building, next to the door there were showcases with the cinema program. The vestibule formed a room with dark wood paneling and a blue and gold ceiling. The rectangular auditorium offered 638 spectators on the stalls, on rank 464 and 98 in the boxes protruding into the hall. In 1935 Heinrich Möller rebuilt the facade, parts of the building were destroyed in the Second World War and could be restored in 1946. In 1956 the cinema was remodeled by the architect de Born, in 1973 its use as a cinema ended, and another renovation turned the building into a self-service shop.

Largest cinema in Europe

Between 1926 and 1927, at Hermannstrasse 214 at the corner of Rollbergstrasse, in the middle of the Neukölln workers' district, under the direction of the architect Fritz Wilms , the Mercedes-Palast was the largest film theater in Europe. Up until then, the Kindl brewery's spacious beer garden was located there, which was particularly well-known across the region at the turn of the century. Fritz Wilms had made a name for himself in Berlin with a number of other theaters, in particular with Piccadilly in Charlottenburg . His buildings were unstructured, clear block buildings. With the Mercedes-Palast , he for the first time dispensed with the overly expressionistic details familiar from other of his buildings. It is no longer possible to determine whether this trend was due to the taste of the times or the available funds. The building has a construction area of around 3773 m², with the front on Hermannstrasse being around 50 meters long and the side on Rollbergstrasse around 72.5 meters. There were shops on both sides of the extended entrance area and five meter high billboards above the four entrances, separated by square half-columns. The upper end was a cornice with green lanterns.

The interior design did not continue this simplicity. In the spacious foyer the colors gold, silver, blue and the scarlet red dominated the walls, the floor consisted of yellow-brown stone slabs from Solnhofen . The adjoining projection room had a dome-shaped, blue-green ceiling, which, illuminated by spotlights above the top of the box, was supposed to imitate an evening sky. During the performance, the vault was transformed through small, illuminated openings into a star-studded night sky. The center of the ceiling was formed by a star-shaped rosette made of colored crystal glass, which was illuminated from the inside and decorated with gold leaf on the edge . The stage with an orchestra pit was connected to the rear by a semicircular projection surface . The room provided the visitors with 2320 parquet and 180 box seats.

A two-manual Oskalyd cinema organ from the company Walcker, Luedke & Hammer from Ludwigsburg was installed in the Mercedes-Palast in 1927 for the musical illustration of the still silent films . Emil “Mile” Sagawe (1895–1988) was the organist in residence from 1950 . In 1951, after the organ had been rebuilt according to his wishes by the organ builder Glöckner, he recorded records for the Odeon company ( Tonfilm-Quellen , Potpourri I and II, Odeon O-28 081 [mx. Be 14 142/43 -I] and Odeon O-28 082 [mx. Be 14 251/52]).

In a report from 1927, the Deutsche Bauzeitung praised not so much the equipment as a completely different, no less important detail of the cinema:

“Each seat costs 0.60 M for the first performance and 1 M for the later performances. In this way, the Mercedes-Palast is a people's theater in the truest sense of the word, since the less well-to-do population is able to watch big films that are mostly still are accompanied by small revues, to be seen at affordable prices. "

However, these admission prices quickly became unaffordable for the majority of the population in the wake of the global economic crisis that began in 1929 : the cinema was nevertheless closed for the first time in 1930 due to insufficient attendance and subsequently served as a ballroom for events in competition with the neighboring Kindl halls. For example, the twelve-year celebration of the Red Flag took place here; The cabaret artist Leon Hirsch was also a guest with his ensemble “ Die Wespen ” in the Mercedes-Saal. In 1932 the architect Gustav Neustein and his artistic assistant Bruno Meltendorf carried out the first renovations. During the National Socialist era, the cinema was open most of the time and was the venue for a number of film premieres such as the 1942 film The Infinite Path (director: Hans Schweikart ). After 1943 it was badly damaged by aerial bombs .

The restoration took place between 1948 and 1951, this time again under the direction of Fritz Wilms. Performances took place during the construction phase, and the foyer , which was used as a demonstration room under the name Metro-Palast , still offered space for 854 spectators. The work gave the projection room a trapezoidal shape with new walls. After its completion in 1951, it had 1,426 seats in the parquet and 634 in the high parquet and resumed film operations as the Europa-Palast .

In 1955, the architect de Born installed a false ceiling in the foyer - the Roxy cinema with 750 seats was built on the upper floor . In 1966 Hans Joachim Woyke undertook further redesigns and in 1969 Woolworth had the entire building converted into a department store, with the facade in particular undergoing massive changes. In 1992 Woolworth moved to the neighboring Kindl-Saal and the former Mercedes-Palast had to give way to the new building on Kindl-Boulevard .

Schillerkiez, Warthekiez and Rollbergsiedlung

The quarter around the Schillerpromenade , which arose on old farmland, was designed by the city of Rixdorf and its mayor Hermann Boddin around 1900 as a “residential quarter for higher earners” and as a counterpoint to the workers' settlement on the Rollbergen, which had been built in the decades before . With its old buildings and the still spacious and leafy median of the 50-meter-wide Schillerpromenade, the district has been under ensemble protection since 1996 . The promenade leads from Columbiadamm over the central Herrfurthplatz with the Galilee Church from 1906 directly to the historic building of the former engineering school for civil engineering and ends there; the listed building from 1914 in the Leinestrasse houses the Carl-Legien-Oberschule . In the 1920s, Bruno Taut , the architect of the Britzer Hufeisensiedlung , added inexpensive workers' apartments on Oderstrasse, which were kept in the style of his social reform, non-commercial concepts.

While the population structure of the Schillerkiez at the beginning of the 2000s was one of the more disadvantaged districts with a high proportion of social assistance recipients , structural unemployment and especially long-term unemployment are particularly pronounced in the Warthekiez . The socio-spatial polarization in both quarters is due to the loss of old industrial workplaces as well as the immediate vicinity of Tempelhof Airport, the noise of which has significantly reduced rental prices and, as a result, the quality of the apartments. Only in the last few years has a slight recovery been noticeable in this area, which is due to the relocation of air traffic to Tegel and Schönefeld airports . With the closure of the airport on October 30th, 2008, this disadvantageous situation came to an end.

The Neukölln district tries to counteract this through measures such as neighborhood management , intensified youth work , model projects for the prevention of violence or the improvement of leisure activities in cooperation with church and independent organizations. Investments such as in the sports park on Oderstrasse are intended to upgrade the district, for example the Neukölln ice rink , which had been restored and expanded with considerable resources, was reopened in autumn 2005 . Since these neighborhoods to the west of the street are joined by the Rollbergsiedlung to the east , which is considered a very special social hotspot, it can be concluded that Hermannstrasse runs through a particularly disadvantaged part of Berlin.

Side streets and cross streets (seen out of town)

- Hasenheide

- Karl-Marx-Strasse

- Karlsgartenstrasse

- Biebricher Strasse

- Airport road

- Mahlower Strasse

- Boddinstrasse

- Selchower Strasse

- Rollbergstrasse

- Herrfurthstrasse

- Werbellinstrasse

- Briesestrasse

- Kienitzer Strasse

- Head street

- Allerstrasse

- Leykestrasse

- Okerstrasse

- Leinestrasse

- Thomasstrasse

- Jonasstrasse

- Warthestrasse

- Schierker Strasse

- Nogatstrasse

- Emser Strasse

- Siegfriedstrasse

- Silbersteinstrasse

- Kranoldstrasse

- Mariendorfer Weg

- Delbrückstrasse

- Glasower Strasse

- Juliusstrasse

literature

- Christiane Borgelt, Regina Jost: Architecture Guide Berlin-Neukölln . Stadtwandel Verlag Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-933743-91-5 .

- District Office Neukölln of Berlin, Dept. Construction (Ed.): 100 Years of Building for Neukölln - A Municipal Building History . Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-00-015848-0 .

- Udo Dittfurth: Line without end - The Berlin Ringbahn . GVE Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89218-074-1 .

- Willy Grigat: Britz once and now , 1932. Excerpts reproduced and used here in: Britzer Heimatgeschichte, published in the parish letter of the Britz village church . Issues February 1979 to December 2000. Britz ( Memento from February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) on the Rollkrug: p. 36, on the windmills: p. 31

- Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko: Are you a bandit? The camp diary of the forced laborer Wasyl Timofejewitsch Kudrenko . Wichern Verlag, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-88981-173-6 . Quotations after the information boards, see "other sources"

- Jürgen Meyer-Kronthaler: Berlin's subway stations - the first hundred years . be.bra Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-930863-16-2 .

- Jürgen Meyer-Kronthaler, Wolfgang Kramer: Berlin's S-Bahn Stations - A Three-Quarter Century . be.bra. Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-930863-25-1 . Quote on Hermann Boddin : p. 120

- Robert Riedel (ed.): Berlin and its buildings. Part V: Buildings for Art, Education and Science, Volume A: Buildings for Art . Verlag von Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-433-00944-9 .

- Erich Schuppan (Ed.): Slave in your hands. Forced labor in church and diakonia Berlin-Brandenburg . Wichern Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-88981-155-8 .

- Klaus Konrad Weber, Peter Güttler, Ditta Ahmadi (eds.): Berlin and its buildings. Part X Volume A: Facilities and structures for supply (3) Funeral services . Verlag von Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 1981, ISBN 3-433-00890-6 .

Web links

-

Hermannstrasse. In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein (near Kaupert )

- Road to Britz . In: Luise.

- Schockwellenreiter, Kiez Schillerpromenade ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Neukölln online, Schillerpromenade settlement

- rbb-online, May 7, 2005: 60 years ago: Liberation of the church forced laborers in Berlin

- Kindl Boulevard

- Frauenwirtschaftszentrum Neukölln

Individual evidence

- ^ Monuments in Rixdorf - Hermannshof

- ↑ Monument List Berlin ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF)

- ↑ Appendix> Rixdorf> Hermannstrasse . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1880, Appendix, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Rixdorf> Hermannstrasse . In: Address book for Berlin and its suburbs , 1900, V, pp. 164, 165.

- ↑ After 65 years: The Magic King disappears from Herrmannstrasse for the time being . On: bz-berlin.de

- ↑ Silvia Perdoni: From the magic . In: Berliner Zeitung , May 8, 2018, p. 10.

- ↑ Information column in the churchyard of the Jerusalem and New Churches with eight picture and writing panels. Kudrenko's quotes are taken from these tables.

- ↑ Bodo Bost: The forgotten cemetery camp . In: Christ in der Gegenwart , CIG, No. 45/2014, p. 515

- ↑ Much of the information for this section is taken from the information column. Kudrenko's quotes are taken from these tables.

- ↑ Bodo Schulz /, Michael Krolop: The private and industrial railways in Berlin (West) . P. 71

- ^ Homepage of the NME , accessed on January 29, 2014

- ↑ Carl-Weder-Park . ( Memento of the original from September 19, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Neubritz.de

- ↑ Hermannstrasse | Construction of a bicycle traffic facility. Retrieved September 13, 2019 .

- ↑ Working, living and living in Neukölln - What about the cycle paths in Neukölln? Retrieved September 13, 2019 .

- ↑ Pop-up cycle path planned on Hermannstrasse - Tagesspiegel Checkpoint. Retrieved June 28, 2020 .

- ^ Karl Heinz Dettke: Cinema organs and cinema music in Germany . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1995, pp. 244-246; on Oskalyd p. 294 f.

- ↑ Deutsche Bauzeitung , year 1927, p. 638; quoted from Riedel 1983

Coordinates: 52 ° 28 ′ 21.7 " N , 13 ° 25 ′ 41.4" E