Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarroti [ mikeˈlanʤelo buonarˈrɔːti ] (full name Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni ; born March 6, 1475 in Caprese , Tuscany ; † February 18, 1564 in Rome ), often just called Michelangelo , was an Italian painter , sculptor , master builder ( architect ) and poet . He is considered one of the most important artists of the Italian High Renaissance and far beyond.

Life

Origin, childhood and education

Michelangelo came from a respected bourgeois family in Florence who belonged to the Guelph party . He was the second son of Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni and Francesca di Neri and was born on March 6, 1475 in Caprese in what is now the province of Arezzo , where his father was bailiff for a year. After that, his family moved back to Florence. He was baptized on March 8, 1475 in the church of San Giovanni in Caprese. Michelangelo had four brothers: Lionardo (1473–1510), Buonarroto (1477–1528), Giovansimone (1479–1548) and Sigismondo (1481–1555). His wet nurse was the wife of a stonemason from Settignano near Florence. Michelangelo's mother died when he was six years old; his father married Lucrezia Ubaldini (d. 1497) in 1485.

Around 1482 Michelangelo came to the Latin school of Francesco da Urbino. Even as a boy, Michelangelo wanted to become an artist against the resistance of his father. After a violent argument, his will triumphed over his father's pride, and so at the age of 13 he became a paid student in Domenico Ghirlandaio's workshop . With him Michelangelo studied the basics of fresco art , with which he succeeded twenty years later in Rome. Like all Florentine artists of his time, he also learned in the Brancacci Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine .

Although Michelangelo initially turned to painting, he was more inclined to sculpture . Before the end of his training as a painter, he entered the art school of Lorenzo il Magnifico in 1489 with the support of his friend Francesco Granacci . Bertoldo di Giovanni , a student of the famous sculptor Donatello, was in charge . One of his first statues was the faun's head (lost), which Michelangelo provided with a tooth gap after a remark by Lorenzo in order to make it appear more realistic. The marble relief of the Battle of the Centaurs created during this period is considered the oldest surviving sculptural work by Michelangelo, as the attribution of the relief of the Madonna on the stairs is controversial. Lorenzo de 'Medici treated Michelangelo like his own son and encouraged him in art and philosophy . During an argument, his classmate Torrigiano slapped him in the face and disfigured him, causing Michelangelo to suffer from his "ugliness" throughout his life. Michelangelo plunged into depressive crises as a result of these and other injuries he suffered. However, he emerged stronger from these, which is evident from his grandiose works.

Study visit to Bologna

Michelangelo had been a member of the Medici school and household for barely three years when his famous patron Lorenzo died. His son Piero di Lorenzo de 'Medici inherited the position, but not his father's qualities. Florence soon rubbed against his rule, and by the autumn of 1494 it became apparent that disaster threatened him and his followers. In anticipation of political upheaval, Michelangelo and two companions left for Bologna .

At the age of twenty he was kindly received there by a member of Ulisse Aldrovandi's family, on whose behalf he created two figures of saints and an angel for the tomb of St. Dominic in the Basilica of San Domenico. After about a year, when work in Bologna failed and in Florence his name had been placed on a list of artists who were to furnish a new meeting room for the Grand Council in Florence while he was away, Michelangelo returned home.

Return to Florence under Savonarola

After Savonarola came to power in 1494, which changed the whole character of bourgeois life in Florence, Michelangelo did not receive any commissions from the city government. But he did not remain idle, because he found a friend in another Lorenzo , the son of Pierfrancesco de Medici , for whom he made a statue of the young Saint John. After imitating the ancient model of a sleeping Cupid , the same patron suggested that his work should be colored and treated so that it looked antique and was sold as such. Without increasing the wages for his work, Michelangelo took part in this fraud for fun, and the piece was dearly sold as a true work of antiquity to a Roman collector, the Cardinal of San Giorgio , Raffaele Riario . When the cardinal discovered the fraud, the dealer had to reimburse the purchase price; It was explained to the young sculptor Michelangelo that the art lover, who had just involuntarily paid such a high tribute to his skills, will certainly take care of him when he comes to Rome.

First stay in Rome (1496 to 1501)

Michelangelo accepted and first arrived in Rome in late June 1496. Cardinal Riario commissioned him to create an ancient Bacchus as compensation for the artificial fraud. It was later suspected that the actual client was Jacopo Galli, a Roman nobleman, since the statue was found in his garden, but an exchange of letters between Michelangelo and his father clearly shows that Riario was the client. Finally, Michelangelo won the favor of Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas (also Jean de Villiers de La Groslaye ), Abbot of St. Denis and Cardinal Priest of Santa Sabina , from whom he received the commission for the Pietà of St. Peter .

These contrasting themes are both originally conceived as well as technically ingeniously executed: the mother with the dead body of the son on her lap, who with her left free hand, pointing in an extended direction, expressively accompanies the tragedy; and the dead Christ. The Pietà is the only statue Michelangelo signed, indicating the importance it had for the artist himself. There is a ribbon diagonally across the Madonna's breast on which the words are chiseled: MICHAEL ANGELUS. BONAROTUS. FLORENT. FACIEBA [T].

Second return to Florence

Michelangelo's first stay in Rome lasted five years from summer 1496 to summer 1501. The period was marked by extreme political unrest in Florence . The excitement over the French invasion, the mystical and ascetic regime of Savonarola, its overthrow, and finally the external wars and internal dissidences that preceded a new unification had all created an atmosphere unfavorable for art.

Nonetheless, Ludovico Buonarroti, who had lost his small permanent office in the turmoil of 1494 and who now regarded his son Michelangelo as the mainstay of his house, had repeatedly urged him to come home. Family duty and family pride dominated Michelangelo's behavior. Throughout the best years of his life he unmistakably accepted severe hardship for the sake of his father and brothers, who were supported by him.

After returning home due to an illness, Cardinal Francesco Piccolomini commissioned Michelangelo to decorate a tomb with 15 sculptures that had already been started in the cathedral of Siena in honor of the most famous member of the family, Pope Pius II . Only four of these figures were finally executed, admittedly only partially by the hand of the master himself.

David sculpture

A work of greater interest in Florence distracted him from the commission for Siena: the execution of the colossal statue of David . It was carved from a huge block of marble that another sculptor, Agostino di Duccio , had unsuccessfully started working on 40 years earlier and has been lying around since then. Michelangelo succeeded, regardless of the traditional treatment of the subject or the historical character of his hero, carving out a youthful colossus, alert and balanced before his great deed.

The result impresses with the free and at the same time precise execution and the triumphant power of expression. The best artists in Florence should work together to determine the location of the statue. They finally agreed on the terrace of the Signoria's palace opposite the Loggia dei Lanzi . Michelangelo's David kept his place here until in 1882 he was transferred to a hall of the Academy of the Arts for his protection, where he inevitably appears narrowed; only one copy of the work is in front of the Signoria today. After a series of light earthquakes in Tuscany, the Italian Minister of Culture announced in 2014 that the statue would be equipped with an earthquake-proof base.

Other sculptures from the same period: a second David in bronze and on a smaller scale, commissioned by Marshal Pierre Rohan and given for completion by the young master Benedetto da Rovezzano, who sent it to France in 1508; a magnificent, roughly hewn Saint Matthew for Florence Cathedral , which he began but never finished; a Madonna and Child commissioned by a Bruges merchant and two unfinished bas-reliefs on the same subject.

Painting of the Cascina battle

Michelangelo was by no means idle as a painter at the same time, but created the Holy Family (Tondo Doni) (tempera on wood) for his and Raphael's common patron, Angelo Doni , which is now in the Uffizi . In the autumn of 1504, when he was completing the David, the Florentine government commissioned him with a monumental painting. Leonardo da Vinci had been hired to paint his magnificent cardboard box of the Battle of Anghiari on the walls of the great hall of the city council . The gonfaloniere Piero Soderini has now secured the order for an accompanying work for Michelangelo.

Michelangelo chose an event of 1364 at the Battle of Cascina during the war with Pisa , when the Florentine soldiers were surprised by the enemy while bathing. With his usual zest he got to the task and had completed a large part of the box when he broke off work at the beginning of the spring of 1505 to accept an appointment to Rome by Pope Julius II . In Karl Woermann's History of Art (1911) it is reported that the copperplate engravings by Agostino Veneziano and Marc Antons ( Marcantonio Raimondi ) can give us the best idea of some groups of this battle picture, which is considered to be a work that has been destroyed without a trace.

His beautifully designed, unfinished box shows how much Michelangelo had benefited from the role model of his older rival Leonardo. For the most part, Michelangelo's early works are comparatively calm in character. His early sculpture surpasses the works of antiquity in their science and perfection and yet exudes ancient serenity. It is shaped by intellectual research, not turmoil or exertion. On the cardboard of the bathers, the qualities were expressed for the first time that were later proverbially associated with Michelangelo, his furia and terribilità , which accompany his incomparable technical mastery and his knowledge. With Michelangelo's departure for Rome in early 1505, the first phase of his career can be considered to have ended.

Second stay in Rome (1505 to 1506)

Shortly after his arrival in Rome, Michelangelo received an appropriate commission from Pope Julius II. The idiosyncratic and enterprising spirit had the idea of a grave monument that would praise him and celebrate him after his death, but which had to be carried out during his lifetime and according to his own plans. After Michelangelo's design was accepted, the artist spent the winter of 1505/1506 in the Carrara quarries, overseeing the excavation and delivery of the marble. In the spring he returned to Rome, and when the marble arrived, he vigorously set about preparing the work. For a while the Pope watched the progress eagerly and was full of kindness to the young sculptor. But then his mood changed. In Michelangelo's absence, Julius had chosen Donato Bramante - no friend of Michelangelo - to carry out a new architectural plan: the new building of St. Peter's Church. Michelangelo attributed the unwelcome invitation now coming to him to the influence and malice of Bramante to interrupt the great sculptural work in order to decorate the Sistine Chapel with frescoes .

Third return to Florence

Soon Julius' thoughts were diverted from plans for war and conquests. One day Michelangelo heard him say to his jeweler at the table that he no longer intends to spend any more money on stones, whether small or large. The artist's discomfort was compounded by the fact that when he appeared in person to collect payments, he was put off day after day and finally dismissed with little courtesy. Then his dark mood seized him. Convinced that not only his employment but also his life was in danger, he suddenly left Rome, and before the Pope's messengers could catch up with him, he was in safe Florentine territory in April 1506.

After returning home, he overheard any request from Rome to return and stayed in Florence for the summer. What he was doing is not known for certain, but apparently, among other things, with the continuation of the great battle painting.

Julius sculpture in Bologna

During the same summer Julius planned and carried out the victorious campaign that ended in his unopposed entry at the head of his army in Bologna . Michelangelo was persuaded to go there under safe guidance and a promise of renewed favor. Julius received the artist kindly, for there was indeed a natural affinity between the two volcanic natures. He asked him to make his own portrait in bronze, which was to be placed over the main entrance of the Basilica of San Petronio as a symbol of his conquering authority .

Over the next fifteen months Michelangelo devoted all his energy to this new endeavor, but the price paid left him with little to live on. He was also inexperienced in metalworking, and an assistant he had summoned from Florence turned out to be defiant and had to be fired. Even so, his genius prevailed against all odds, and on February 21, 1508, the majestic bronze colossus of the seated Pope in robe and scepter, grasping the keys with one hand and the other stretched out in a gesture of blessing and command, came to his place raised above the church portal.

Three years later the sculpture was destroyed in a revolution. The people of Bologna rose against the authority of the Pope; its delegates and supporters were chased away and the effigy thrown from its place. Michelangelo's work was mockingly dragged through the streets, smashed and the fragments thrown into the furnace.

Third stay in Rome

Sistine Chapel - ceiling and wall paintings

Preparations

In the meantime, after the work was finished, the artist had followed his reconciled master back to Rome . However, it was not the continuation of the papal tomb that awaited him here, but the execution of some paintings in the Sistine Chapel , which had been questioned before his departure. He always said that painting was not his business; he was aware of the hopes of his enemies that a great fresco-painting venture would be beyond his ability; and he approached the project with concern and reluctance. In fact, this work that was forced on him has become his most important title of fame to this day.

His story is that of an indomitable will and almost superhuman energy, even if his will could hardly ever prevail and his energy always struggled with the circumstances. The Pope's first plan only included the twelve apostles . Michelangelo began accordingly, but was not satisfied with it and instead proposed a design with many hundreds of figures that would embody the history of creation up to the Flood, with additional portraits of prophets and sibyls and the forefathers of Christ. The whole was to be framed and subdivided by an elaborate framework of painted architecture, with a multitude of nameless human figures to mediate between the static framework and the great dramatic and prophetic scenes. The Pope granted the artist the freedom to proceed according to his ideas.

execution

By May 1508, the preparations in the chapel were finished and work began. Later that year, Michelangelo appointed a couple of assistant painters from Florence. Trained in the traditions of the earlier Florentine School, they were apparently unable to interpret Michelangelo's fresco designs either freely or uniformly enough to satisfy him. In any case, he soon released her and carried out the rest of the colossal task on his own, apart from any necessary, purely mechanical help.

The physical conditions of the continuous work face up on this vast ceiling surface were extremely unfavorable and stressful. After four and a half years of arduous work, the task was complete. Michelangelo had been plagued by payment delays and hostile intrigues alike as he advanced, with his opponents casting doubts about his abilities and praising Raphael's superiority . That gentle spirit would not have been an enemy by nature, but unfortunately Michelangelo's capricious, self-centered temperament prevented a friendship between the two artists that could have halted the troublemakers.

At one point, an urgent need for funds to support the project forced him to pause his work for a moment and pursue his patron as far as Bologna. This was between September 1510, when the great series of themes along the center of the vault was completed, and January 1511, when the master went back to work and began filling in the intricate side spaces of his decorative plan.

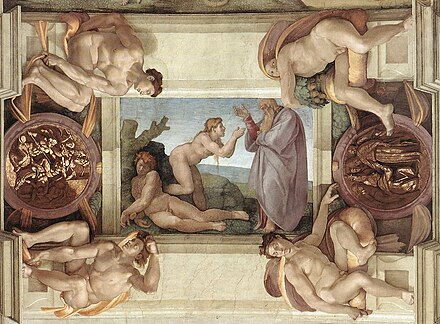

The main area of the Sistine ceiling forms the barrel vault overlying the chapel and is divided into four larger fields, which alternate with five smaller fields. The following subjects are dealt with in this order by Michelangelo:

- the separation of light from darkness;

- Creation of the sun, moon and stars;

- Creation of water;

- Creation of man;

- Creation of woman;

- Temptation and expulsion from paradise;

- the sacrifice of Noah ;

- the flood;

- the drunkenness of Noah.

The characters in the last three scenes are on a smaller scale than those in the first six. Apparently he started with the chronologically last subject, Noah's drunkenness, and worked backwards, increasing the scale of his figures from the fourth subject (temptation by the serpent and expulsion from paradise). This is attributed to the fact that he was only able to effectively judge the visual foreshortening and composition from the ground after the completion of the three topics .

In fields 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, the field of view is narrowed by the architectural framework with its seated pairs of supports - commonly known as slaves or atlases.

Flanking these smaller compositions, there are figures seated on the sides, alternating prophets and sibyls, along the side surfaces between the vaulted crown and the walls. The seated architectural figures are great in the variety of their poses and exude a lot of vitality.

The way the ceiling fresco in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican works is relatively simple. For this purpose, cardboard boxes with the drafts that Michelangelo had previously drawn up on a 1: 1 scale and in which he had made holes in the most important places, placed on the still damp plaster and worked on the holes with coal dust . Then the stencils were removed and he could concentrate on the markings while painting.

Two more prophets are introduced at the ends of the series, making a total of seven prophets and five sibyls. The triangles to the right and left of the prophets at either end contain the death of Goliath, the death of Holofernes , the brazen serpent and the punishment of Haman . In the twelve bezels above the windows are groups of Christ's ancestors , whose names are marked with inscriptions, and in the twelve triangles above them (between the prophets and sibyls) are other related groups, crouching or sitting. The latter are shown in comparatively simple human actions - exalted but not falsified.

The work reflects all of Michelangelo's skills at their peak. The artist seems to have gained sovereignty in the course of the work. The absolute top work, however, is the fresco of the “Creation of Adam”, which has been published thousands of times in the world and embodies a qualitative improvement in all figures. With his enormous personality and powerful painting, Michelangelo exerted a great influence on all painters of his time. Some, however, persisted in clumsy exaggerations and clumsiness and could in no way come close to the model in terms of size and strength. A few, however, showed a certain independence and thus developed images of strong expressiveness.

Julius grave monument

No sooner was the Sistine Chapel completed than Michelangelo resumed work on the marble for Julius' monument. But after only four months Julius died. His heirs immediately (in the summer of 1513) signed a new contract with Michelangelo for a smaller version of the monument. The original plans are unknown. We only know that the monument was supposed to stand in one of the chapels of St. Peter, detached from the wall, square and free, which was unknown in the tomb architecture of the Renaissance.

The new plan was also extensive and grand. It envisaged a large three-sided, two-story structure protruding from the church wall and adorned with statues on its three free sides. The colossal figure of the Pope was to lie on the upper floor, with a vision of the Virgin with the child above him, lamenting angels on the sides, prophets and allegories in the corners - a total of 16 figures. On the lower floor there were 24 figures in niches and on protruding plinths: in the niches winner; before the end, slaves or prisoners pilasted between them, apparently symbolizing either conquered provinces or the arts and sciences in slavery after the death of their patron.

A very damaged and controversial design by the master in Berlin, with a copy by Sacchetti, is said to represent the design at this stage of reduction. The entire work should be completed within nine years. During the next three years Michelangelo appears to have completed at least three of the promised figures, for which blocks from Carrara had already arrived in Rome in July 1508. In addition to David, these are his most famous traditional sculptures, the Moses , since 1545 in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, and the two slaves in the Louvre .

Moses, originally intended for one of the pages on the upper floor, is now placed at eye level: in the center of the main view of the monument, as it was finally finished, on a reduced and changed scale, by Michelangelo and his assistants in old age. The prophet, who should have come down from Mount Sinai and seen the Israelites worship the golden calf, sits heavily bearded and wrapped up, only with his left arm exposed, his head raised and turned to the left, his left hand on his lap and the right the tablets of the law grasping. The work is extremely accomplished, except for a spot or two, and the statue looks like one of the prophets of the Sistine Ceiling carved in marble - an incarnation of majestic indignation and menace.

The two slaves in the Louvre are young male figures of equally perfect execution, naked except for the ribbon on the chest of one and on the right leg of the other. One, with his left hand raised to his head and the right pressed to his chest, his eyes almost closed, seems to be succumbing to the agony of death. The other, with his arms behind his back, looks up, hopelessly fighting. All three figures were finished between 1513 and 1516.

Return to Florence

Plan for the facade of San Lorenzo

In 1513 Cardinal Giovanni de Medici succeeded him to the papal throne under the title Leo X. Julius II. At about the same time, the Medici, through violence and deceit, had restored their influence in Florence by overthrowing the free institutions that had prevailed since the days of Savonarola. On the one hand, this family was traditionally a friend and patron of Michelangelo; on the other hand, he was a patriotic friend of the Republic of Florence. From then on, then, his personal sympathies and political allegiance were in conflict.

It has often been said that grief and confusion over this conflict have cast their shadow over much of his art. First of all, after the Medici came to power, he again interrupted his work on Julius' tomb. Leo X and his relatives had a grand new plan to enrich and decorate the facade of their own family church of San Lorenzo in Florence . Michelangelo let himself be carried away by the idea, forgot about his other big task and offered his services for the new facade.

They were gladly accepted, even though the work was initially intended to be entrusted to Leonardo da Vinci. Julius' heirs, for their part, were accommodating, and Leo's request allowed them to cancel the three-year-old contract in favor of someone else after the size and sculptural decorations of the Julius Monument were again reduced by almost half. Michelangelo quickly drew up a plan for the facade of San Lorenzo, combining sculpture and architecture, as grand and ambitious as the one for the original Julius monument. The contract was signed in January 1518 and the artist went to Carrara to oversee the breakage of the marble.

Although Michelangelo was 43 years old and facing the second half of his life, his best days were over. All the adversities so far were nothing compared to those that were still ahead of him. He had hired a firm of stonemasons in Carrara to supply the material for the facade of San Lorenzo, and he himself apparently entered into a kind of partnership with them.

When everything was going well there under his supervision, the Medici and the Florentine magistrate asked him for political reasons to move to new quarries in Pietrasanta near Serravalle on Florentine territory. To the indignation of his old customers in Carrara and his own, Michelangelo has now had to relocate his place of work. The mechanical difficulties in excavating and transporting the marble, the infidelity and incompetence of his employees angered him so much that he abandoned the entire contract. The contracts for the facade were canceled in March 1518 and nothing came of the whole magnificent plan.

Other works (1518–1522)

Michelangelo returned to Florence, where he received numerous proposals for work. The King of France asked for something from his hand to be placed next to two of Raphael's pictures that were in his possession. The authorities of Bologna wanted him to design the facade of their Church of St. Petronius; that of Genoa, a bronze statue of its great commander Andrea Doria . Cardinal Grimani pleaded for any paintings or statues that he had left; other art lovers pressed him for trifles such as pen drawings or drafts.

Finally, his friend and supporter Sebastiano del Piombo in Rome - always eager to feed the feud between Michelangelo and Raphael supporters - begged him after Raphael's death to return to Rome to snatch the painting work from the dead master's students, which were still had to be done in the chambers of the Vatican. Michelangelo did not comply with any of these requests. Reliable knowledge of his activities between 1518 and 1522 is limited to the rough processing of four more slaves for Julius' tomb and the execution of an order for three Roman citizens for the statue The Risen Christ , which he had received in 1514.

The roughly worked slaves were for a long time in a grotta in the Boboli Gardens ; their current location is the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence. The Christ, practically finished by the master, with the last repairs by his pupils, stands in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, for which it was intended; he shows little dedication and ingenuity, even if the parts made by Michelangelo himself are extremely perfect in terms of form and craftsmanship.

Medici tombs

Michelangelo spent the next twelve years (1522–1534) in Florence, again mainly in the service of his opposing and capricious patrons - the Medici. The plan for a large group of monuments for deceased members of this family to be erected in a new sacristy or burial chapel in San Lorenzo was first proposed to Michelangelo in 1520 by Cardinal Giulio de Medici . However, there was no practical impetus for the work until Giulio after the death of Leo X and the brief pontificate of the Puritan and iconoclastic Hadrian VI. 1523 himself became Pope under the title Clement VII .

Even then, the initiative was just wavering. First, Clemens suggested that Michelangelo hire another artist, Andrea Sansovino , for this task. After this proposal was dropped at Michelangelo's decisive objection, Clemens next distracted the artist with an order for a new architectural design, namely for the proposed Medici or Laurentine library. The Biblioteca Laurenziana had been classified as a priority project by Clement VII and, with 50,000 ducats, was to be built as quickly as possible. The work took up Michelangelo's time between April 1524 and October 1526. Only then did he return to working on the chapel. After many changes finally taking shape, the plans for the funerary chapel ( Sagrestia Nuova ) did not include monuments to the founding fathers of the house, Cosimo il Vecchio , Lorenzo il Magnifico or Leo X , as initially envisaged , but only to two younger members of the house, the had died shortly before, Giuliano, duc de Nemours, and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino.

Michelangelo pored over various designs for this work for a long time and was still busy with the execution - some of his time was also devoted to the blueprints for the Medici library - when he was interrupted by political revolutions. In 1527 the Sacco di Roma and with it the fall of Pope Clement took place. The Florentines took the opportunity to drive the Medici out of the city and re-establish a republic.

Defense of Florence

Of course, there were no more funds available for the work in San Lorenzo, and at the invitation of the new Signoria, Michelangelo occupied himself for a while with a group from Hercules and Cacus and another from Samson and the Philistines - to carve the latter out of a block of marble, the had already been edited by Baccio Bandinelli for another purpose.

Soon after, however, he was called to protect the city itself from danger. Clemens and his enemy Charles V had reconciled and were now both anxious to bring Florence back under the rule of the Medici. In view of the imminent siege, Michelangelo was appointed chief technician for the fortifications. He spent the early summer of 1529 strengthening the defenses of San Miniato ; from July to September he was on a diplomatic mission in Ferrara and Venice .

After he returned in mid-September, the Florentine cause proved hopeless because of internal treason and the overwhelming strength of the enemies. After a fit of melancholy , he suddenly left for Venice, where he stayed for a while negotiating a future residence in France. He returned to Florence during the siege, but he had no part in the final agony for the freedom of the city.

When the city submitted to its conquerors in 1530, most of those who helped defend it received no mercy. Michelangelo thought he was in danger with the others, but at the intervention of Baccio Valori he was immediately re-employed by Pope Clement. In the next four years he temporarily continued his work on the Medici monuments - from 1532 with the support of Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and other students - and the construction of the Laurentine Library .

Completion of the Medici tombs

In 1531 Michelangelo fell seriously ill; In 1532 he had a longer stay in Rome and entered into another contract for the completion of the Julius Monument, which has now been reduced even more and should be placed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli instead of St. Peter . In the autumn of 1534 he left Florence for good. Pending work in the Medici Chapel was completed by students, and the chapel was not opened for viewing until 1545.

The statues for the Medici Monument, along with Moses and the slaves, are among the best works of Michelangelo's middle period of sculpture. They consist of a Madonna and Child and two monumental groups, both with a seated portrait statue in a niche and two emblematic figures leaning on each side above a sarcophagus. The unfinished Madonna and Child combines a realistic, naturally lively motif with a learned, complex design and majestic effect. In the end - contrary to the artist's initial intention - it was erected on an empty wall in the chapel and flanked at a large distance by statues of Saints Cosmo and Damian, works by students.

The portraits are not realistic, but treated in a typical way. Lorenzo seems to symbolize cunning brooding and concentrated inner deliberation, Giuliano vigilance and self-assured practical survey immediately before an action. This contrast between meditative and active character corresponds to the contrast between the emblematic groups that accompany the portraits. Night and day lean at Duke Giuliano's feet, the former feminine, the latter masculine. The night sinks into an attitude of deep, restless slumber; the day, head and face stuck out of the marble, awakens full of anger and unrest.

Equally grandiose, but less powerful, are the postures of the two corresponding figures who lean against the sarcophagus of the pensive Lorenzo between sleeping and waking. Of these, the male figure is known as evening, the female as morning (Crepuscolo and Aurora). Michelangelo's original idea, which was partly based on ancient models in gable and sarcophagus groups, connected earth and sky with night and day on the Giuliano monument, and other, undoubtedly corresponding figures, with morning and evening on the Lorenzo monument. These figures later fell out of the plan, and the corners intended for them remained empty.

According to his own notes, Michelangelo wanted to depict how the elements and powers of earth and heaven mourn the death of the princes . River gods should lie on the broad base at the foot of the monuments. They were never completed, but a bronze cast of one of them and the torso of a large model have been identified and can be seen in the National Museum and Academy in Florence, respectively.

Rome (1534–1541)

Sistine Chapel - Last Judgment

Michelangelo had intended, in accordance with the new treaty of 1532, to devote all his efforts to completing the Julian Monument once he had finished the Medici Tombs. But his intention was again disappointed. Pope Clement insisted that he complete his decorations of the Sistine Chapel by repainting the large front wall above the altar, which until then had been decorated with frescoes by Perugino . The theme chosen was the Last Judgment , and Michelangelo began preparing drafts. In the fall of 1534, at the age of 60, he settled in Rome for the rest of his life. Clemens died immediately afterwards. His successor in the papacy was Paul III. from the house of the Farnese .

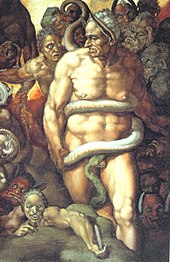

Paul III claimed even more than his predecessor . Michelangelo for himself and forced him to postpone all other engagements. For the next seven years, Michelangelo's time was essentially filled with painting the Last Judgment. In contrast to the ceiling frescoes, Michelangelo used almost lavishly blue paint, which at the time consisted of ground lapis lazuli and was correspondingly expensive. One of the reasons for this was that this work was personally commissioned by the Pope, which meant that he had a considerably higher budget for the mural. Measured by the value of the materials, it is now considered one of the most expensive paintings in the world. Since Michelangelo was not allowed to sign his frescoes, he used a trick to be immortalized in them anyway. The skin that Bartholomew holds in his left hand shows Michelangelo's likeness. After this was completed in 1541, he then had to take over two more large frescoes in a new chapel, which the Pope had built in the Vatican and which was named after him Cappella Paolina . The subjects of these frescoes were the conversion of Paul and the martyrdom of Peter.

The Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel is one of the most famous individual images in the world. In it Michelangelo expressed all his spiritual experiences as an artist. In the center of the picture is the world judge. Divine justice inexorably separates the good from the damned. In the lunettes at the top of the picture you can see the attributes of Christ: cross, column and crown of thorns, the symbols of the passion. On the left side of the picture one can see how a companion takes John the Baptist by the right arm to point out the two women on his right. It is about Herodias , who asks her daughter Salome for forgiveness. Pavel Florenskij points out the special "spatial planning in the 'Last Judgment'" Michelangelo and continues:

“The fresco shows a certain inclination. (The higher a point is on a picture, the more distant the point of representation is from the eye of the beholder. According to the nature of the eye, it should see them becoming ever smaller, force of perspective foreshortening of the figures. that the lower figures adjust the higher ones.) But as far as their size is concerned, the size of the figures on this fresco increases with increasing height, ie with increasing distance from the viewer! But these are properties of the spiritual space. The more distant something is, the larger it is, and the closer something is inside it, the smaller it is. This is what is known as the reverse perspective . If we look at this fresco, we begin to feel our complete incomparability with its space. We are not drawn to this space. And on the contrary: it repels us just as a sea of mercury would repel our body. Even if we are able to contemplate it, it is transcendent to us, who think with Kant and Euclid. Although Michelangelo lived in the Baroque era, he did not belong in the past or future epoch. He was their contemporary and he wasn't at the same time. "

Rome (1542–1564)

After the completion of the Last Judgment , Pope Paul III. by Michelangelo to decorate his private chapel, the Cappella Paolina , with frescoes. In the two frescoes, Michelangelo once again reached a spiritual climax. The artist depicts the fate of the individual in symbols, because the conversion of Saul and the crucifixion of Peter are inner self-portraits and are intended to frighten the randomly wandering spectators and encourage them to recognize them. Michelangelo said of himself that fresco painting was not a thing for old people, so he no longer felt the strength that such a love as painting claims.

In the unfinished sculptures, the pictorial work has been replaced by a sign that cannot be interpreted by the word.

Art that reveals or veils again as beauty, veils the truth again, is a conscious and deliberate understanding of the cycle of creation.

In 1547 Michelangelo took over the construction management of the still fragmentary new St. Peter's Basilica . With reference to the plans of his predecessor Donato Bramante , he also designed the ribbed dome in the middle of a central building, which, however, was only executed in a modified form by Giacomo della Porta after his death .

Michelangelo Buonarroti died on February 18, 1564 in Rome. He was buried in the Church of Santa Croce in Florence.

plant

opinion

Michelangelo saw himself primarily as a sculptor, not a painter, architect or poet, although he achieved significant and groundbreaking achievements in all of these areas. But he placed sculpture above all other art forms, as evidenced by many of his letters, which are mostly signed with "Michelangiolo, scultore" ("Michelangelo, sculptor").

In accordance with his Platonic conceptions, Michelangelo's artistic work was based on the idea that the spirit, as the highest principle, contains the idea that takes precedence over all sensual experience.

He saw the work of art preformed in the raw marble block, it was already slumbering as an idea in the stone and only had to be "freed" from it.

He also regarded the stone as something to be given soul. The examination of the nature and shape of the material was of great importance to him. For Michelangelo, the choice of the block was already an important aspect of his artistic work, as he spent several weeks, sometimes even months, in the quarries.

The basic idea came about with the help of drawings made exclusively from the model. If he then went to the block, he usually worked on all parts of the figure at the same time in order to keep an eye on the whole. Side views were not developed separately, they arose as the work progressed. Often he only devoted himself to the back view and the face as the last. He proceeded step by step when working on the surfaces. In his numerous unfinished works, which give us an insight into his approach, there were perfectly worked out and polished next to half and roughly hewn parts.

A special aspect in Michelangelo's work and at the same time an expression of his respect for the material shows his design and treatment of the bases of his sculptures. In early works such as Bacchus, the Pietà of St. Peter's Church, David or Christ, a certain realistic imitation of nature can still be recognized.

Later, for example in the case of Moses, Rachel, Lea, Sieger and the slaves of the Louvre, the shape of the plinth is subject to a geometric principle, which is, however, characterized by a lack of consistent rigor. These bases are enlivened by numerous, subtle irregularities and asymmetries and thus acquire an artistic statement. They are on an equal footing with the actual representation, with greater harmony being achieved through the emphasis on wholeness.

The problem of the non-finito in Michelangelo

In the course of his life, Michelangelo developed a large number of plans for works and projects, some of which were gigantic in size. Only a fraction of what his mind produced was ultimately carried out. The reasons for this are discussed very contradictingly. From simple explanations, such as lack of time or loss of interest, to philosophical and psychological interpretations, various approaches to this problem can be found in the literature.

The most striking example of the rudimentary realization of a large-scale project is the intellectual and artistic work on the tomb of Pope Julius II. For over 40 years, Michelangelo was engaged in this, his most ambitious project, which he himself described as "his tragedy". From the original design of a free-standing monument with more than 40 figures, after numerous circumcisions and revisions, due to numerous external influences, the comparatively modest solution of a wall grave with only three self-executed figures (Moses, Rahel and Lea) as well as some individual sculptures that are not used find in the ensemble (six slaves, winner).

The unfinished is reflected in much of Michelangelo's sculptural work. After all, it is generally assumed that the "non-finito" in Michelangelo was not a fixed principle from the outset, as was almost 400 years later with Rodin, who was undoubtedly inspired by the idea of the unfinished in Michelangelo's sculptures and calculated this effect in integrated his own work in order to give more emphasis to specially elaborated parts.

It is believed, however, that the failure of some figures was the result of carefully considered aesthetic decisions made during the work process.

Some authors are of the opinion that the “perfectionist” Michelangelo would always have been dissatisfied with the realization of his “idea” in the form of a fully elaborated figure and would rather have accepted the inadequacy of a certain openness than take the risk of getting to the core by completely defining it not to hit in an absolute way. Michelangelo ascribes similar assumptions to this attitude: “It doesn't work perfectly anyway, so a continuation doesn't make sense.” Overall, it is difficult to decide in which of the unfinished sculptures such considerations may have played a role.

If one looks at the heads of the evening redden and the day in the entirety of the other, largely elaborate figures of the Medici graves, the question arises whether there really was a deliberate termination of the work for artistic considerations, or whether the planned one Failure to complete due to external circumstances.

Michelangelo worked on the Pietà Rondanini until his death and was unable to complete it. Here you can see that the artist carried out a complete redesign while creating and even destroyed parts of the sculpture again. Whether this was done to replace an original idea with a new one, or whether the master simply "messed up" remains open.

Just as unexplained and subject to speculation is the question of whether the four unfinished slaves could not have been designed more perfectly or whether they simply remained lying there because they no longer fit into the circumcised program of the Julius tomb that was ultimately executed.

Works (selection)

painting

| image | title | When originated | Size, material | Exhibition / collection / owner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The temptation of Saint Anthony | 1487 or 1488 | 47 × 35 cm, oil and tempera on panel | Kimbell Art Museum , Fort Worth | |

| The Holy Family with the Boys of St. John (Tondo Doni) | 1503/04 or 1507 | 91 × 80 cm, tempera on wood | Galleria degli Uffizi , Florence | |

| Sistine ceiling | 1508-1512 | 40.5 × 13.2 m, fresco | Sistine Chapel , Rome | |

| The Last Judgement | 1536-1541 | 17 × 15.5 m, fresco | Sistine Chapel, Rome | |

| Conversion of Saul | 1542-1545 | 625 × 661 cm, fresco | Cappella Paolina , Rome | |

| Crucifixion of Peter | 1546-1550 | 625 × 662 cm, fresco | Cappella Paolina, Rome |

sculpture

| image | title | When originated | Size, material | Exhibition / collection / owner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madonna on the stairs | 1489-1492 | 57.1 × 40.5 cm, marble | Casa Buonarotti, Florence | |

| Centaur Battle | 1492 | 80 × 90.5 cm, marble | Casa Buonarotti, Florence | |

| crucifix | around 1492/93 | 139 × 135 cm, wood, colored | S. Spirito , Florence | |

| Saint Petronius | 1494/95 | 64 cm high, marble | Arca di San Domenico , Basilica of S. Domenico, Bologna | |

| Holy Proculus | 1494/95 | 58.5 cm high, marble | Arca di San Domenico , Basilica of S. Domenico, Bologna | |

| Kneeling angel (candlestick angel) | 1494/95 | 51.5 cm high, marble | Arca di San Domenico , Basilica of S. Domenico, Bologna | |

| Bacchus | 1496/97 | 203 cm high, marble | Museo Nazionale del Bargello , Florence | |

| Pietà | 1498/99 | 174 cm high, marble | St. Peter's Basilica , Rome | |

| Saint Paul | 1501-1504 | 127 cm high, marble | Piccolomini Altar , Duomo, Siena | |

| Saint Peter | 1501-1504 | 124 cm high, marble | Piccolomini Altar , Duomo, Siena | |

| Saint Pius | 1501-1504 | 134 cm high, marble | Piccolomini Altar , Duomo, Siena | |

| Saint Gregory | 1501-1504 | 136 cm high, marble | Piccolomini Altar , Duomo, Siena | |

| David | 1501-1504 | 516 cm high, marble | Galleria dell'Academia , Florence | |

| Madonna and Child (Bruges Madonna) | around 1504/05 | 128 cm high, marble | Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk , Bruges | |

| Madonna with Child and St. John the Baptist (Tondo Taddei) | around 1504–1506 | 109 cm diameter, marble | Royal Academy of Arts , London | |

| Madonna with Child and St. John the Baptist (Tondo Pitti) | around 1504–1506 | 85.5 × 82 cm, marble | Museo Nazionale del Bargello , Florence | |

| Saint Matthew | 1506 | 216 cm high, marble | Galleria dell'Academia , Florence | |

| The dying slave (the dying prisoner) | around 1513-1516 | 229 cm high, marble | Musée du Louvre , Paris | |

| The Rebel Slave (The Rebel Prisoner) | around 1513-1516 | 215 cm high, marble | Musée du Louvre , Paris | |

| Moses | around 1513–1516 and 1542 (?) | 235 cm high, marble | S. Pietro in Vincoli, Rome | |

| The victory (the winner) | around 1520–1525 | 261 cm high, marble | Palazzo Vecchio , Florence | |

| The risen Christ | 1519-1521 | 205 cm high (without cross), marble | S. Maria sopra Minerva , Rome | |

| Madonna and Child (Medici Madonna) | 1521-1534 | 226 cm high, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| Lorenzo de 'Medici | around 1525 | 178 cm high, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| The morning (aurora) | 1524-1527 | 206 cm long, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| The evening (crepuscolo) | 1534-1531 | 195 cm long, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| Giuliano de 'Medici | around 1526–1534 | 173 cm high, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| The night (Notte) | 1525-1531 | 194 cm long, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| The day (Giorno) | 1526-1531 | 185 cm long, marble | S. Lorenzo , Florence | |

| Apollo | around 1530-1532 | 146 cm high, marble | Museo Nazionale del Bargello , Florence | |

| Brutus | around 1539–1540 | 74 cm high, marble | Museo Nazionale del Bargello , Florence | |

| Pietà Bandini | around 1547–1555 | 226 cm high, marble | Museo dell'Opera del Duomo , Florence | |

| Pietà Rondanini | 1552 / 53-1564 | 195 cm high, marble | Museo del Castello Sforzesco , Milan |

architecture

- 1524–1526 Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence

- 1537–1564 design of the Capitol Square in Rome

- 1547 Construction management of St. Peter's Basilica, dome

- 1560–1562 Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri in Rome

drawing

- 1533 The fall of Phaeton. Royal Library, Windsor (since 1810)

- 1533 The fall of Phaeton. British Museum

- 1540 (or circle?) The Holy Family with the Johannesknaben

- 1553 The fall of Phaeton. Venice, Accademia Gallery

Poems and letters

In addition to the pictorial work, a number of sonnets were created, especially dedicated to his long-time girlfriend Vittoria Colonna and his friend Tommaso de 'Cavalieri , as well as madrigals and other poems. A treatise on eye care and cosmetics from around 1520 (on the last page of the “Vatican Codex” of his poems) is based on recipes from an ophthalmological treatise by the doctor and later Pope Petrus Hispanus .

- Michelangelo Buonarroti: Me, Michelangelo: Letters, Poems and Conversations . Ed .: Fritz Erpel. 7th edition. Henschel, Berlin 1979.

- RA Guardini: Michelangelo. Poems and letters in Project Gutenberg

- Michelangelo Buonarroti: Love poems , Italian and German, from the Italian by Michael Engelhard , selected and provided with an afterword by Boris von Brauchitsch , Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2007. ISBN 978-3-458-34944-0

Some of these poems have been set to music by various composers:

- Hugo Wolf : Michelangelo-Lieder , three poems by Michelangelo for a bass voice and piano (1897)

- Richard Strauss : Madrigal (I bow my neck into the yoke) op.15 No. 1

- Josef Schelb : Three Sonnets by Michelangelo for voice and piano op.5 (1916)

- Benjamin Britten : Seven Sonnets after Michelangelo op.22

- Dmitri Schostakowitsch : Suite based on words by Michelangelo Buonarroti op. 145 for bass and piano (1974), world premiere: October 12, 1975; Version for bass and orchestra op.145a, world premiere: December 23, 1974, Leningrad

Quote

- You know lord that I know how much you know

- that in order to feel you I reach you,

- and know i know you know i'm the same:

- what is it that makes us hesitate in greeting?

- Is the hope that you brought me true

- and true the wish and sure that it will apply,

- the wall between us breaks

- Concealed woes now have double the power.

- If I only love what you love about you

- love most about yourself, heart, do not be angry.

- These are the ghosts who so woo each other.

- What I desire in your face

- the people watch it incomprehensibly,

- and whoever wants to know has to die first.

Sonnet to Tommaso de 'Cavalieri, translation: Rainer Maria Rilke

Commemoration

- April 6th memorial day on the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod calendar

- Since September 29, 1985 namesake for the asteroid (3001) Michelangelo

- Michelangelo Buonarroti was depicted on the Italian 10,000 lire banknote issued by the Banca d'Italia between 1962 and 1973.

- On March 5, 2003, on his 528th birthday, a Google Doodle was dedicated to him.

literature

Non-fiction

- Hans Mackowsky : Michelangelo , Berlin, Marquardt, 1908.

- Sigmund Freud : The Moses of Michelangelo , 1914 ( online resource ).

- Ernst Steinmann , Rudolf Wittkower : Michelangelo Bibliography 1500–1926 , Leipzig 1927.

- Luitpold Dussler : Michelangelo Bibliography 1927–1970 , Wiesbaden 1974.

- Lutz Heusinger: Michelangelo. Life and work in chronological order . Gondrom Verlag, Bayreuth 1976.

- Joachim Poeschke : The sculpture of the Renaissance in Italy; Volume 2: Michelangelo and his time , Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7774-5430-3 .

- Peter Dering: Michelangelo. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 5, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-043-3 , Sp. 1489-1502.

- Valerio Guazzoni, Alessandro Nova , Pier Luigi de Vecchi: Michelangelo - The Sculptor, The Architect, The Painter , Stuttgart and Zurich 1984 (3 volumes, including an important entry by Enzo Noè Girardi: Michelangelo's seals ).

- Michael Rohlmann, Andreas Thielemann (Eds.): Michelangelo - New Contributions , Munich, Berlin 2000.

- Fritz Erpel (Ed.): Ich Michelangelo , Henschelverlag Berlin 1964

- Ross King: Michelangelo and the Pope's frescoes , Munich 2003, ISBN 978-3-8135-0193-3 .

- Daniel Kupper: Michelangelo . Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-50657-2 (with further literature after 1970).

- Susanne Gramatzki: On the lyrical subjectivity in Michelangelo Buonarroti's rime . Heidelberg, University Press Winter, 2004.

- Trewin Copplestone: Michelangelo . Publisher EDITION XXL, 2005, ISBN 3-89736-334-8 .

- Stefanie Penck: Michelangelo . Prestel Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-7913-3428-8 .

- Antonio Forcellino: Michelangelo. A biography . Munich 2006, ISBN 3-88680-845-9 .

- Frank Zöllner , Christian Thoenes, Thomas Pöpper: Michelangelo 1475–1564. The complete work. Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3053-6 .

- Horst Bredekamp : Michelangelo - Five Essays , Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8031-5179-7 .

- Volker Reinhardt : The Divine. The life of Michelangelo. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59784-8 .

- William E. Wallace: Michelangelo - the artist, the man, and his times , Cambridge [u. a.] Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-11199-7 .

- Stephanie Buck: Michelangelo's Dream , exhibition catalog Courtauld Gallery , London, University of Washington Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-907372-02-5 .

- Cristina Acidini Luchinat: Michelangelo. The sculptor , Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2010. ISBN 978-3-422-07014-1 .

- Giovan Battista Fidanza: Reflections on Michelangelo as a wood sculptor . In: Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte , 59 (2011), pp. 49–64, ISBN 978-3-205-78674-0 ( digital version ).

- Michael Hirst: Michelangelo , New Haven [u. a.] Yale Univ. Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-300-11861-2 (Volume 1).

- Grazia Dolores Folliero-Metz, Susanne Gramatzki (eds.): Michelangelo Buonarroti. Life, work and effect. Positions and Perspectives in Research / Michelangelo Buonarroti. Vita, Opere, Ricezioni. Approdi e prospettive della ricerca contemporanea . Frankfurt a. M. [et al.]: Peter Lang, 2013.

- Petr Barenboim, Arthur Heath: 500 Years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel , LOOM, Moscow, 2019, ISBN 978-5-906072-42-9 ( online resource ).

- Andreas Beyer: "... what a person can do ..." Comments on Goethe's appreciation of Michelangelo, in which: Art brought to language, Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2017, pp. 83–98, ISBN 978-3- 8031-2784-6

- Horst Bredekamp : Michelangelo . Wagenbach, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-8031-3707-4 .

Fiction

- Karel Schulz: Petrified Suffering , Gütersloh 1960.

- Rosemarie Schuder : The battered Madonna. The life of Michelangelo 1527–1564 , Berlin 1960.

- Irving Stone : Michelangelo . Reinbek, Rowohlt-Taschenbuch Verlag, 2005, 736 pages, 19th edition, ISBN 3-7766-0694-0 / ISBN 978-3-499-22229-0 (original title: The Agony and the Ecstasy , first edition 1961).

- Rosemarie Schuder: Der Gefesselte , Berlin 1962.

- Michael Petery: Michelangelo - Piety and Ironie , Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-9810448-0-5 .

- Michael Petery: Michelangelo - The Wrath of the Creator , Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-9810448-1-2 .

- Sebastian Fleming : The Dome of Heaven , Munich 2010, ISBN 3-404-16490-3 .

- Mathias Énard : Tell them about battles, kings and elephants , Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-8270-1005-6 (original title: Parle-leur de batailles, de rois et d'éléphants , 2010).

- Leon Morell: The Sistine Heaven ; Scherz, Frankfurt 2012, ISBN 978-3-502-10224-3 .

Movies

- Michelangelo - Inferno and Ecstasy . Period film, USA, 1965, 138 min., Written by Philip Dunne , directed by Carol Reed , based on the novel by Irving Stone .

- Michelangelo - genius and passion . Period film, USA, I, 1991, book: Julian Bond , Vincenzo Labella .

- The divine Michelangelo (OT: The Divine Michelangelo ). Documentary and docu-drama , Great Britain, 2004, 116 min., Written and directed by Tim Dunn, production: BBC .

Web links

- Literature by and about Michelangelo in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Michelangelo in the German Digital Library

- Works by Michelangelo at Zeno.org

- Artcyclopedia: Michelangelo Buonarroti (works)

- Casa Buonarroti, Florence (Italian, English)

- Michelangelo's biography

Individual evidence

- ^ Klaus Oppermann: Michelangelo Buonarroti. Childhood and adolescence. In: oppisworld.de. January 25, 2014, accessed January 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Reinhard Haller: The power of hurt. Ecowin, Salzburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-7110-0078-1 , p. 213.

- ↑ Michelangelo's "David" gets earthquake protection. On: ORF.at of December 21, 2014 ( Memento of December 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Thompson, B .: Humanists and reformers: a history of the Renaissance and Reformation . Grand Rapids, Me. : WB Eerdmans, 1996, ISBN 978-0-8028-3691-5 ( archive.org [accessed May 29, 2021]).

- ↑ Art: DOT IN THE SKY BLUE . In: The mirror . tape 9 , February 28, 1994 ( spiegel.de [accessed October 6, 2017]).

- ↑ My eyes will see him - Michelangelo's self-portrait in his “Last Judgment”. Retrieved October 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Fig.

- ↑ Pavel Florenskij: The reverse perspective . Matthes & Seitz, Munich 1989, p. 44 f. (Russian original: 1920).

- ↑ Carl Hans Sasse: History of ophthalmology in a short summary with several illustrations and a history table (= library of the ophthalmologist. Issue 18). Ferdinand Enke, Stuttgart 1947, p. 30 f.

- ↑ DD Shostakovich - Catalog raisonné ( Memento of February 8, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Calendar - April 6th - Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints. Retrieved November 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Minor Planet Center: Minor Planet Circulars. September 25, 1985, accessed November 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Michelangelo's 528th birthday. March 5, 2003, accessed August 29, 2020 .

- ↑ IMDB: The Divine Michelangelo. Retrieved November 27, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Michelangelo |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Buonarroti, Michelangelo (shortened); Michelagniolo di Ludovico di Buonarroto Simoni (complete) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian painter, sculptor and architect |

| BIRTH DATE | March 6, 1475 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Caprese, Tuscany |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 18, 1564 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Rome |