Percy Ernst Schramm

Otto Steinert. Portrait of Percy Ernst Schramm, historian, 1961/1962

Percy Ernst Schramm (born October 14, 1894 in Hamburg , † November 12, 1970 in Göttingen ) was a German historian who primarily researched the history of the early and high Middle Ages as well as Hanseatic cultural and family history of the modern era .

With an interruption due to military service in World War II and a teaching ban until 1948, Schramm taught from 1929 to 1970 as a full professor of middle and modern history and historical auxiliary sciences at the University of Göttingen . Schramm's work is largely shaped by the contact with Aby Warburg , the pioneer of modern cultural studies, and the art and cultural historian Fritz Saxl . Schramm's uncritical attitude towards National Socialism broke up his friendship with Saxl and it also prevented further exchange with the Warburg Cultural Studies Library, which was run by Jewish scholars and moved to London . From 1943 Schramm kept the war diary in the high command of the Wehrmacht .

Schramm is one of the most internationally renowned German medieval historians of the 20th century. He earned merit in Medieval Studies by increasingly introducing cultural-scientific questions and interdisciplinary working methods, striving for international cooperation and evaluating the images of rulers as historical sources . Schramm's work therefore has a pioneering character in medieval research. His main interest was the research of medieval symbols of rule . He carried out pioneering research on symbols and rituals of rule, the Ottonian empire and political iconography .

In the early 1960s, he published the war diary of the Wehrmacht High Command . Through this edition and his lecturing activities, he gained the reputation of a leading expert on the history of the Second World War in the post-war period. Schramm's work on the history of his family exerted a significant influence on historical research in Hamburg in the second half of the 20th century .

Life

Origin and youth

Percy Ernst Schramm belonged to a wealthy merchant family that had lived in Hamburg since 1675 and whose history he later wrote himself. His father Max Schramm was born in Brazil in 1861 . He did not embark on a commercial career but became a successful lawyer . From 1892 Max Schramm was a partner in the important law firm " Wolffson , Dehn and Schramm". From 1904 he belonged as a member of the citizenship to the “faction of the right”, from 1912 he was an elected member of the Senate and from 1925 to 1928 he was second mayor of Hamburg. His mother Olga, née O'Swald, also came from an Old Hamburg merchant family. The English first name goes back to Olga's father Albrecht Percy O'Swald. Her great uncle William Henry O'Swald started the company “Wm. O'Swald & Co “to the leading trading house in East Africa . Thanks to a trade agreement concluded in 1859 with the Sultan of Zanzibar , the business could be extended far into the interior of Africa.

As the only son, Schramm had two younger sisters. He grew up in the upper class Hamburg district of Harvestehude . From 1901 to 1904 he attended Adolph Thomsen's private school and then the secondary school branch of the Johanneum . His parents wanted him to work as a businessman or a lawyer in a profession that had previously been common in the family. As a youth, Schramm integrated himself into the social life of the upper class of Hamburg's upper class. As a high school student, his enthusiasm for the tradition of the upper bourgeoisie prompted him to deal with the past using pedigrees. According to Schramm, the research into the origins of the ancestors was decisive for his interest in history. While still at home, he met the cultural scientist Aby Warburg and became his student. Warburg and Schramm's father, who was interested in culture, met through the same social circles in Hamburg. Warburg had been in close contact with Schramm since 1911. The sources allow only a few conclusions about the type and scope of the training. Warburg supported Schramm in his genealogical studies and gave him the necessary freedom for intellectual development. He granted Schramm free access to the private library he had built.

In addition to the connection to Warburg, Schramm began to discover the Middle Ages for himself in the years before the beginning of the First World War . Numerous trips and visits to castles, churches and cities were beneficial for this. At the age of sixteen he had already “devoured” Karl Hampe's very popular “Imperial History in the Age of the Salians and Staufers”, first published in 1909 . At seventeen Schramm was determined to become a historian. Since 1910 he took private lessons in Greek voluntarily. Schramm took pride in his origins, a sense of tradition and a high level of self-confidence with him from his childhood years.

Military service and front deployment

In August 1913, Schramm passed the Abitur at the Realgymnasium. In April 1914 he started at the University of Freiburg i. Br. The study of history. In the same year he published the results of his genealogical studies in the fifth volume of the “Hamburg Gender Book”. After a semester he had to interrupt his studies because of the outbreak of war. On August 3, 1914, at the age of 19, he volunteered for military service. He stayed mainly on the Eastern Front . Due to an injury to his left forearm on May 15, 1915, he was incapable of field service for three months. Schramm took advantage of a long, almost one-year rest period from the late summer of 1916 for his further training - he learned the Italian language - and for his genealogical studies. During the war he kept in close correspondence with his teacher Warburg. In June 1916 Schramm was promoted to lieutenant. In September 1917 his department was used in the conquest of Riga . For the successful advance in early 1918 he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class . After the peace of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918, Schramm's unit was transferred to the Western Front in France.

In his unpublished biographical notes for the year 1894, Schramm assigned the First World War essential importance for his personality development. He liked his military rank as Rittmeister, whose position in the cavalry indicated social prestige, and flirted with this rank until the time of the Second World War. The experience of war on the Eastern Front left him with an anti-Polish resentment and a "fear of a communist overthrow" fed by the immediate experience of the October Revolution in the Baltic States . The war experiences created a generational connection: the men of the interwar period were broken down into generations by their contemporaries. Schramm belonged to the "young front generation" of those born between 1890 and 1900 and felt himself to be a member of a special generation through military service.

Years of study in Hamburg and Munich

After the end of the war, Schramm returned to Hamburg in December 1918. He took care of his teacher Warburg, who developed a serious mental illness after the defeat became known. Schramm explicitly acknowledged the Weimar Republic, but the ceding of territories in the east strengthened "a tendency towards nationalistic radicalization" in him. He made himself available to the government as a time volunteer in the Bahrenfeld Freikorps . Whether against the left, against Poland or "someone else" was all the same to him. From the summer semester of 1919 Schramm studied history, historical auxiliary sciences, art history and constitutional law at the Hamburg University . Schramm was one of the first students at the newly founded University in Hamburg. Schramm was not involved in the suppression of the so-called brawn riots in Hamburg at the end of June 1919, since he had left Hamburg in the summer and continued his studies in Marburg . On the occasion of the Kapp Putsch in March 1920, Schramm began to keep a diary about the events that moved him. He rejected the coup mainly because Kapp had broken his oath of allegiance to the government. Schramm published his diary-like notes a little later.

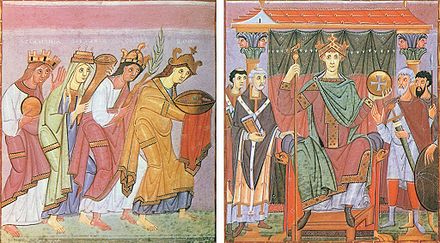

From the summer semester of 1920, Schramm studied in Munich to expand his knowledge of art. There he attended several courses with the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin . After the defeat of the war and the reorganization of the state structures in Germany, questions about the specifics of German art and the “essence of the state” were in the foreground for many intellectuals. These questions also preoccupied Schramm. From 1920 he turned to the Middle Ages. He was impressed by the dedication image in the Reichenau Gospels of Otto III. strong. The picture even inspired him a little later on the topic of his doctoral thesis, in which he wanted to grasp the "essence" of the "state" led by Otto.

Warburg's health did not improve during Schramm's stay in Munich. In 1920 Warburg, accompanied by Schramm, went to Jena for further treatment. In the following years, too, Schramm was particularly valued by Warburg. From then on, Fritz Saxl played an important role in the Warburg Library . He began to make the library accessible to young scientists at the University of Hamburg. Schramm and Saxl first met in person in Aby Warburg's Hamburg library in 1913. In the 1920s Schramm received more human and scientific impulses from hardly anyone else than from Saxl. There was also a friendly relationship with the art historian Erwin Panofsky . In addition to Saxl and Warburg, the historian Otto Westphal had a considerable influence on Schramm's scientific thinking.

Scientific beginnings in Heidelberg (1921–1929)

In the summer semester of 1921, Schramm moved to Heidelberg to finish his studies with a doctorate with Karl Hampe . During his years in Heidelberg he made contact with the historians Ernst Kantorowicz , Friedrich Baethgen , Otto Cartellieri , the Germanist Friedrich Gundolf , the church historian Hans von Schubert and the Indologist Heinrich Zimmer . The friendship with Kantorowicz was particularly close. He expressly emphasized night-long conversations with Kantorowicz. Schramm had a close relationship with his academic teacher Hampe in Heidelberg. He frequented Hampes family privately. In 1922 he started studying the history of Emperor Otto III at Hampe . (996–1002) doctorate summa cum laude. Hampe thought the dissertation was “a really significant piece of work”. It remained unprinted as a whole, but the results were published in articles.

In 1922 Schramm gave his first academic lecture at the Warburg Library in Hamburg, The Image of Rulers in Early Middle Ages Art . In the spring of 1923 his first mediaeval publication appeared under the title About our relationship to the Middle Ages in the “Österreichische Rundschau” . Further work focused on the imperial ceremony at the Ottonian court and its relation to antiquity. The most extensive study from the years 1922 to 1925 was the treatise The Rulers' Image in Early Middle Ages Art , which was published in the series “Lectures of the Warburg Library” edited by Saxl.

After completing his doctorate, Schramm had the opportunity, through his friend Saxl, of a well-paid position in Hamburg, where he was supposed to work on an edition of Warburg's unpublished writings in the library. Even more important for him, however, was Harry Bresslau's offer from Heidelberg to participate in editing projects for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH). Working at Bresslau not only meant a job at Monumenta Germaniae Historica, the most important institute dedicated to researching Franconian and German medieval history and the edition of its sources, but also offered him the prospect of a habilitation at the prestigious University of Heidelberg. So he decided to stay in Heidelberg. From 1923 to 1926 Schramm was Bresslaus' assistant and worked on the last volume of the "Scriptores" series of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. In addition, he worked on the issue of the documents of Heinrich III. With. During his assistantship he married Ehrengard von Thadden in March 1925 , the daughter of the Pomeranian landowner and district administrator Dr. jur. Adolf von Thadden (1858–1932) and his first wife Ehrengard, b. von Gerlach (1868–1909). The marriage had three children, including the architect Jost Schramm and the Eastern European historian Gottfried Schramm . Schramm's marriage inspired him to deal with the Junkers of Eastern Elbe in the second half of the 1920s .

In 1924 Schramm completed his habilitation in Heidelberg. In his habilitation thesis he again dealt with Otto III .; The focus of the investigation was the idea of Rome in the Middle Ages. From 1924 to 1929 he was a private lecturer in Heidelberg. He gave his inaugural lecture on the historical foundations of the border states of the German east . The losses of Germany in the east as a result of the Versailles Treaty were a dominant topic of political discourse in the Weimar Republic and also influenced Schramm's academic work. Schramm assumed that there was instability in Eastern Europe, which would enable Germany to become a hegemonic power there. However, he avoided specific suggestions as to how Germany should seize its power-political opportunity in the East. The inaugural lecture was not published because the “Österreichische Rundschau” intended for publication was discontinued. After a lecture in the winter semester of 1924/25 on the “History of Catholic Eastern Europe” in Schramm's further work, the topic quickly lost its importance.

In 1928 Schramm published his first monograph, The German Kings and Emperors in Pictures of their Time, 751–1152 . There he recorded the imperial images for the first time completely in their traditions (illumination, coins, seals, etc.). Schramm's father died in May 1928, but his strong influence on the son continued. It was evident from the fact that, decades later, Schramm would always think about every publication whether his father would have appreciated what he had written. In the winter semester of 1928/29, Schramm represented Hampes' chair in Heidelberg. The habilitation thesis was published in an expanded and revised version in 1929 as a two-volume description of Kaiser, Rome and Renovatio in the series "Studies of the Warburg Library" edited by Saxl. Saxl supported him with the dissertation as well as with Kaiser, Rome and Renovatio . According to one of David Thimmes' assumptions, the font Kaiser, Rom und Renovatio might never have appeared without Saxl's commitment , because Schramm had lost interest in the “Rome idea” at the end of the 1920s. At the end of his Heidelberg years, he probably joined the German People's Party in 1928 . He did not renew his membership when he moved to Göttingen.

First teaching activity in Göttingen (1929–1933)

Schramm's work Kaiser, Rom und Renovatio , published in the summer of 1929, brought him his academic breakthrough. Even before it went to press, it had a considerable impact and made a major contribution to Schramm being offered a professorship at the University of Göttingen in February 1929 . From April 1, 1929, he taught there as a professor for middle and modern history and historical auxiliary sciences. At the same time he became director of the history seminar. In the scientific organization, however, he played no special role in Göttingen.

The professorship also made Schramm financially independent. However, his appointment to Göttingen had dragged on for months, as the minister of education and his ministerial director initially intended the chair for sociology. In the year of his appointment, Schramm's teacher Warburg died. In the years that followed, the cooperation and exchange of ideas between Schramm and the cultural studies library led by Saxl intensified. Schramm even sounded out whether he had a chance of being called to Hamburg, but no such appointment was made.

In 1930 Schramm visited Emperor Wilhelm II, who was living in exile in Holland, in Doorn . In the 1960s, Schramm cited the ex-monarch's interest in the books of his Göttingen colleague Karl Brandi as the reason for his visit . During the conversation with Schramm, the emperor was interested in when the eagle had become the imperial emblem. Schramm published his visit in 1964 in the Festschrift for Max Braubach . In July 1930 he received offers to chairs of history in Freiburg and Halle. At this point in time, Schramm had only taught three semesters in Göttingen; he decided to stay there. As a result of the negotiations to stay, his salary was increased sharply, and an "apparatus for Middle Latin literature" was set up in the library of the historical seminary. On the basis of the “Middle Latin Apparatus”, the project to publish a bibliography on medieval intellectual history was born. With “Aristotle in the Middle Ages”, “Virgil in the Middle Ages” and “Literature on Latin Biblical Commentary”, three booklets emerged.

Schramm's growing recognition in the professional world was also reflected in the fact that he wrote literary reports for the history teacher magazine “ Past and Present ” and in 1931 was accepted into the editorial board of the “ Historical Journal ”, of which he became the youngest co-editor. He was also elected to the executive committee of the Association of German Historians . At the international level, he began to become involved in the International Iconographic Commission from 1929 and regularly took part in the meetings of the International Historical Committee. In the international environment, Schramm made contacts that lasted until the end of his life. His private life also continued to develop positively. Schramm's third son was born in the summer of 1932.

In his first years in Göttingen, Schramm resumed his eastern political engagement. In February 1931 he organized together with Karl Brandi at the University of Göttingen as the first German university an "Ostmarkehochschulwoche", which should bring the students closer to the "meaning of the Ostmark for people and empire". The two Göttingen historians undertook information trips through Silesia , East Prussia and the Danzig area. In the summer of 1932 Schramm and Brandi organized a German Historians ' Day in Göttingen , which for the first time focused on the problems of the German East at a German historians' event . The subjects dealt with were unmistakably directed against the Versailles Treaty and the neighboring states, especially Poland. However, this focus did not go back to the Schramms and Brandis initiative alone. Neither were experts in the history of the Germans in East Central Europe, nor were they spokesmen for historical research on the East. With the political upheavals of 1933, Schramm's activities in this area also ended.

From the 1930s onwards, Schramm researched the ordines , the rules for the course of medieval coronation celebrations. The starting point was his essay, The Ordines of the Medieval Imperial Coronation , published in 1930 in the Archive for Document Research. His interest in the Ordines was also evident in the courses “The election of the pope” and “The German coronation”.

Schramm's role in National Socialism (1933–1945)

Relationship to the Nazi regime

The biographical information available about Schramm's attitude towards National Socialism does not give a clear picture. Schramm's relationship to anti-Semitism, for example, is perceived differently. That he wrote in a private letter to Herbert von Bismarck on March 31, 1933 : “If German anti-Semitism is to be accepted as a fact that must be reckoned with politically in the near future, then it seems to me only in the form of a fight against Eastern Judaism and Marxist Judaism possible ”is generally interpreted as a willingness to come to terms with anti-Semitism at times. Nevertheless, according to Folker Reichert , Schramm was not an anti-Semite. Ursula Wolf, on the other hand, sees no fundamental racial prejudices in Schramm, but certain resentments typical of the time, at least towards a certain social Jewish class, when Schramm also wrote to his mother in 1933: I welcome it, of course. ”However, Schramm rejected the Nazi racial policy. For Eduard Mühle , however, Schramm was prepared to play down, even justify, the terror against Jews and other population groups long after 1933. Schramm dismissed some aspects of the Nazi regime that he disliked, such as the restriction of political freedoms, as a short-term “revolutionary unrest”. He tried to help displaced scientists like Ernst Kantorowicz or Sigfried Heinrich Steinberg with letters of recommendation.

Despite his adjustment and approval, Schramm also had difficulties with the Nazi regime. He considered the introduction of the Weimar Constitution to be a historically significant process, but he did not attach particular importance to its core content, the parliamentary party democracy. In 1932 he stood up as chairman of the Göttingen "Hindenburg Committee" for the re-election of the old Reich President Paul von Hindenburg , which he used to oppose the opposing candidate Adolf Hitler . To this end, he made numerous election speeches. Schramm's political activity thus reached its climax. It earned him the rejection of the National Socialists, in particular that of the Göttingen district leadership of the NSDAP. However, he quickly adapted to the political changes and enthusiastically welcomed the “ seizure of power ”. When the Reichstag fire on February 27, 1933, Schramm thought of "the fabulous opportunities" to use it as a pretext against the communists. In May 1933 he tried to understand the book burnings in Germany . He used his international contacts to justify the events in National Socialist Germany to the outside world. Like many other scholars, he was one-sided about the regime. From spring to summer 1933 he was visiting professor at Princeton University and in his speeches on “the National Revolution in Germany” he emphasized what he saw as the positive achievements of the Nazi regime. He praised the " synchronization of the countries " and the shedding of "the shackles of Versailles" as particularly positive . Schramm regretted that only a few people abroad would see how the new Germany developed.

During his absence, Schramm was removed from the board of the Göttingen student union by the new rulers . Even his professional position was in danger. Therefore, he returned from the United States in June. His longtime friend Otto Westphal committed himself unconditionally to National Socialism. Together with Alfred Schüz, he promoted Schramm's professional dismissal. This ended the decades-long friendship with Westphal; Schramm announced it in a letter. Despite the considerable problems with the Nazi regime, Schramm stuck to his positive attitude towards the political situation in Germany. Interpreting the present from history, in a letter to a Romanian friend dated September 20, 1933, he compared the political upheavals of 1933 with the German Reformation of the 16th century and described a “new, promising Germany”. The dictatorship seemed to him to have the advantage of protecting Germany from political turmoil.

At the celebration of the founding of the Reich at the University of Göttingen on January 18, 1934, the ancient historian Ulrich Kahrstedt criticized Schramm's international commitment. Kahrstedt accused Schramm and Brandi of failing to represent German interests in the East at the Warsaw Historians' Day in 1933. After these allegations, Schramm restricted his activities in international scientific cooperation. He also joined the Reiter SA in January 1934 , of which he remained a member until 1938. In 1935, Schramm was removed from the editorial office of the “Historischen Zeitschrift”; In 1937 he also had to stop working in the history teacher magazine “Past und Gegenwart”. As a “representative of late liberalism”, as the Göttingen rector Friedrich Neumann called him, the Göttingen Nazi leadership did not place any political trust in him. His application for membership in the NSDAP in 1937 therefore dragged on for two years. In 1939 Schramm achieved his admission to the NSDAP and even backdating to the year he was aiming to join 1937. In February 1947, however, he claimed that he had not even applied for membership himself. Rather, this happened through the SA without his knowledge.

Regardless of his attitude to National Socialism, Schramm was moved to London in May 1937 for the coronation of King George VI of England . invited. He was the only German civilian who received such an invitation - recognition that was recognized even in the “ Kladderadatsch ”. At that time Schramm was recognized worldwide as a recognized expert in coronation research. He was ready to use his knowledge of the symbols of power for politics. In doing so, he moved away from the position of his teacher Warburg, who had been critical of the political instrumentalization of art history. For the English coronation ceremony, he suggested to Hitler that the gilded dove scepter from the time of Richard of Cornwall , made in 1262 and kept in the Aachen Cathedral Treasury , be reproduced and given to the English king as a present. During his stay in England, the Archbishop of Canterbury Cosmo Gordon Lang asked him about his relationship to National Socialism, to which he replied differently: “With regard to rearmament (balance of forces) 200 percent Nazi. With regard to "labor peace", consolidation of peasantry, " strength through joy " 100 percent Nazi. Race theory, German cult, educational policy, Nazi ideology: 100 percent opponent. ”He advocated foreign and armaments policy because it would restore the German Reich's international position in the world. After the occupation of the Sudetenland, he cheered Hitler: “80 million - without bloodshed. Neither Bismarck nor the Maid of Orléans could do that , only someone who combined both skills […]. ”In 1938 he welcomed the“ Anschluss of Austria ”. A change to a professorship in Leipzig failed in 1941 because of the “liberalist attitude” that he was accused of.

Schramm's wife Ehrengard von Thadden was much more distant from the Nazi regime. After the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 , Schramm was denounced by the Göttingen rector, the classical philologist Hans Drexler , as a sympathizer of the July 20, 1944 resistance. Thanks to the advocacy of the university committees and above all his military superior, Colonel General Alfred Jodl , there were no consequences for Schramm. His sister-in-law Elisabeth von Thadden was sentenced to death by the People's Court in September 1944 for “high treason” and executed.

Research and teaching

Schramm's research topics differed from the emphases typical of the period in positivist imperial history, folk history and medieval constitutional history . Between 1933 and 1939 he also worked on topics of daily political relevance. This included his colonial history work on the Hamburg merchants.

In addition to the coronation ordines, Schramm mainly published numerous works on the history of kingship in Europe. In 1934 the coronation appeared among the West Franks and Anglo-Saxons and in 1935 the coronation in Germany until the beginning of the Salian house . Just in time for the coronation in England on May 12, 1937, his History of the English Royalty in the light of the coronation appeared in April 1937 in Germany and England . Shortly after the start of World War II, he published his portrayal The King of France . As a historian during the Nazi era, Schramm continued to adhere to scientific standards and rejected the purely pragmatic understanding of science of National Socialism. But as a staunch historian , he also orientated himself on the problems of his own time and investigated the question of why Germany's path to a powerful nation-state had been so difficult. In this sense, the work on the medieval symbols was “a kind of search for traces of the essence of peoples.” From 1938, however, he used terms in his scientific publications and made considerations that were more clearly oriented towards the National Socialist world of thought. He emphasized the importance of Germanic culture for the Middle Ages. With his symbol research he hoped to gain insight into the "intellectual history of the individual races". According to David Thimme, he tried with his research to catch up with the prevailing ideology in order to strengthen his own position in the changed academic structures. However, Thimme also states "that his attempts to get closer to the political opportunity did not go very far".

From 1933 onwards, Saxl could no longer continue his research in Germany because of his Jewish origin. At the end of 1933, he and his colleagues had to relocate the Warburg Cultural Studies Library from Hamburg to London. The Warburg Institute , which is still active today, emerged from this in London . In 1934, Edgar Wind , an employee of the cultural studies library, expressed himself critical of the Nazi regime in the introduction to the first volume of the "Cultural Studies Bibliography on the Afterlife of Antiquity". Another co-author of the bibliography, Raymond Klibansky , is said to have said “that he would no longer enter the house of a German professor”. Schramm did not differentiate between “hostility towards Germany” and criticism of the Nazi regime. In January 1935, Schramm broke off the longstanding collaboration with Saxl and the Warburg Library for Cultural Studies (KBW). The reason he gave was that he did not want to work on a work in which “anti-German” authors were also involved.

When the sociological seminar at the University of Göttingen was closed in 1936 and the subject of history took over its stock of books, Schramm not only accused sociology of intellectual poverty, but also expressed his political distrust of the Göttingen sociologists: their library had "a not inconsiderable number of books" contain "which cannot be made accessible to the students at all or only with precautionary measures".

Schramm's research until 1939 was characterized by a "hermit-like working style". The exchange with specialist colleagues, which is important for scientific knowledge, declined sharply. The National Socialist rule had brought Schramm's important interdisciplinary cooperation in the humanities at the University of Göttingen to a standstill through personnel changes. The “Middle Latin Apparatus” was also discontinued. Schramm's key interlocutor, Kantorowicz, had left Germany for good in 1938.

Schramm was not particularly involved in the Nazi war mission of the humanities . With the outbreak of war began the phase of research into topics that, with the exception of a few reviews, had nothing to do with the Middle Ages; Studies on the economic and social history of the 19th century came to the fore. In the middle of the war, he was able to complete the almost 800-page work Hamburg, Germany and the World in 1943 . In the same year his hometown was badly hit by Allied bombing during Operation Gomorrah .

Preparation of the war diary and expert work during World War II

In the Second World War, Schramm participated as a soldier from the start. A few weeks after the outbreak of war he was promoted to Rittmeister of the Reserve . In 1941 he belonged to the group of office Wehrmacht propaganda in the High Command of the Wehrmacht . There he wrote press releases for domestic and foreign newspapers. The reports are typical war propaganda and were approved by Major General Hasso von Wedel . In 1942 Schramm took part in the conquest of the Crimea as a staff officer . From March 1943 until the surrender in 1945 he was Helmuth Greiner's successor in the war diary at the Fuehrer's headquarters. In this function he summarized all "operational processes" of which he was aware and selected the documents and reports for the war diary. The focus was on operational decisions and processes. Due to his selective way of working, he did not document the aspects relevant to international war law. The war diary therefore gives only a limited picture of the course of the war from the perspective of top management. On June 1, 1943, Schramm rose to major in the reserve. Since 1943 he thought the war was finally lost. In the early summer of 1944, he expressly rejected a planned leave of absence to Göttingen in order to fulfill his obligations in science. Schramm preferred his service in the Wehrmacht . He celebrated his fiftieth birthday on October 14, 1944 at the Fuehrer's headquarters . At the end of the war, he ignored the order to destroy the war diary and ensured that it was preserved. When he described his role as a war diary keeper in the Wehrmacht command staff to his student Joist Grolle , he described himself as the “notary of doom”.

In addition to keeping the war diary, Schramm also acted as an expert. This includes the preparation of an expert opinion on the “fuel issue” from 1944/45. Schramm praised German science for its production of synthetic rubber ( Buna ) and synthetic gasoline. In doing so, it broke the Allies' monopoly on raw materials and supported IG Farben in setting up factories for the production of synthetic fuel. This meant that the German military economy and warfare continued to function. According to a presumption by Jörg Wollenberg , in the large-scale Auschwitz III project, the new facility in the Fürstengrube external command was related to Schramm's report. Even after 1945, Schramm saw no connection between his report and the Auschwitz complex. The expert opinion is printed in a smooth version in the Festschrift published in 1954 for the Göttingen international lawyer Herbert Kraus .

post war period

Schramm was in American captivity from May 1945 to October 5, 1946. As a prisoner of war , he wrote a military memorandum for the Historical Section of the US Army . During this time he resumed the work on his memories, which he had started as a soldier in 1942. In October 1946 he returned to Göttingen from the Nuremberg prison camp. The British occupation forces forbade him to return to his Göttingen chair. In a report from February 1946, the occupation authorities had doubts as to whether he would “incorporate positive democratic teaching into his teaching”. As a war diary keeper, Schramm witnessed the defense at the Nuremberg trial of the main war criminals and testified in June 1946 in favor of his former superior, Colonel General Jodl. On January 29, 1946, he was in discussion as one of the successors for the medieval chair in Hamburg. However, the professorship was awarded to Hermann Aubin . From 1946 to 1948 Schramm was banned from teaching. He felt this to be a bitter injustice. Like many other scholars, he endeavored to create the impression that he had remained untouched by Nazi ideology. In 1947 Schramm was able to establish friendly contact with several colleagues who had emigrated, including Ernst Kantorowicz and Hans Rothfels . Kantorowicz, Rothfels, and others were advocates in Schramm's denazification process , which lasted from October 1946 to September 1948. The American Historical Division , which had an interest in his collaboration and for whose predecessor unit he had temporarily worked, gave a positive opinion. In November 1948 Schramm was able to resume teaching as a professor in Göttingen.

In the post-war period, however, Schramm did not succeed in winning back his former friends from the Warburg Institute. In two letters, written in December 1946 and January 1947, he tried to resume personal and academic relationships with Saxl. Schramm began to communicate with the Warburg Institute as if the old injuries had never happened. As a victim of the Nazi regime, Saxl had no sympathy for Schramm's silence about the past and for his attempt to “move on to the agenda about these things”, as Saxl put it in a draft letter. In his obituary for Saxl from 1958 in the Göttingische Schehrten Advertisements , Schramm did not say a word of self-criticism. He kept quiet about his part in the break of friendship. Rather, it is said to have been Saxl who caused the break.

Schramm became a corresponding member of the Central Management of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica in 1948 and a full member in 1956 . Numerous other academies in Göttingen (member 1937), Munich (corresponding member 1965), Vienna, Stockholm, Spoleto and the American Historical Academy of Medieval Studies accepted Schramm as a member. In 1958 he was accepted into the Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts . For him this was the most important and most important honor. A year later he was awarded the highest distinction by the Herold association with the Bardeleben medal.

In the second half of the 1950s, Schramm and his colleague Hermann Heimpel made the history seminar in Göttingen one of the most respected addresses in Germany for the subject of history. In the post-war period, Schramm became one of the leading experts on the history of the Second World War. His public lectures in the 1950s met with a great response. In his speeches, he advocated honoring the memory of those who died in the World War. In 1952, Schramm prepared an expert report for the trial against Otto Ernst Remer on behalf of Fritz Bauer . In 1955, Schramm was one of the professors who ensured that Leonhard Schlueter , who was appointed Lower Saxony's Minister of Culture, had to resign a few days after his appointment. In the 1960s Schramm edited the war diary of the Wehrmacht command staff together with his two students Andreas Hillgruber and Hans-Adolf Jacobsen as well as Walter Hubatsch . From 1961 to 1964 he published the war diary in four volumes. He was the author and editor of the source at the same time. In 1963 he published Henry Picker 's notes on Hitler's table talks at the Führer Headquarters from 1941–1942 .

After 1945 Schramm saw no need for corrections to his books on English or French royalty. Schramm published his great works on medieval history in the 1950s and 1960s: three volumes of rule signs and state symbolism 1954–1956, in 1962 together with the art historian Florentine Mütherich the monuments of the German kings and emperors and 1968–1971 the five-volume work Charlemagne. Life's work and afterlife . From 1968 his collected essays on the history of the Middle Ages appeared in four volumes.

In 1958 Schramm was still tying in linguistically and in terms of content to contemporary research on the East by investigating the “historical legal title [s]” that the Germans had “in the areas separated from Germany”. He spoke of "the floods" which "had risen from the east since the Huns". Schramm also relativized the idea of a 'German cultural institution' in the East, pointed to the crimes committed by the Germans in East Central Europe and was committed to a German-Polish reconciliation. On the part of Polish historians Schramm's “attempt at a new view of the Polish-German problems” was perceived as “a sensation in the world of the West German intelligentsia”.

Last years

In the 1950s and 1960s Schramm wrote more on the commemorative work “Year 94”. The illustration remained unpublished until the end of his life. He never mentioned his former friend and sponsor Saxl in it. Half of the pages were taken up by the First World War.

In 1963 Schramm retired. In the same year he was elected Chancellor of the Pour le Mérite Order for Sciences and Arts. This gave him the highest distinction that a scientist could receive in the Federal Republic of Germany. A year later he was awarded the Great Federal Cross of Merit with a Star . In terms of the number of students he was one of the most successful German scholars of the post-war period. He supervised 59 doctorates as an academic teacher. On his seventieth birthday in 1964, Schramm was honored by his students and friends with a festschrift. Important pupils of Schramm were János Bak , Wilhelm Berges , Arno Borst , Marie Luise Bulst-Thiele , Donald S. Detwiler , Adolf Gauert , Joist Grolle , Andreas Hillgruber, Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, Norbert Kamp , Hans-Dietrich Kahl , Reinhard Rürup , Hans Martin Schaller , Ernst Schulin and Berent Schwineköper . Reinhard Elze was not his student during his studies, but saw him as his teacher for his own scientific development. In Göttingen, however, there was no school direction, rather Schramm attached importance to independence for his students from an early age.

In 1967, Schramm introduced the German-Jewish art historian Erwin Panofsky, his former friend from the Warburg School, to the order Pour le Mérite as Chancellor. There was no self-critical word on the problems of his past or on alienation. In 1968, the salvage of the Cathedra Petri confirmed the hypothesis put forward by Schramm in 1956 in the third volume of rulership and state symbols , according to which the wooden throne had been made around 870 for Charles the Bald .

Schramm died of a heart attack on November 12, 1970 in a hospital in Göttingen. He found his final resting place in the family grave in the Ohlsdorf cemetery in Hamburg. His estate is the most extensive part of the family archive and is in the Hamburg State Archive .

plant

Schramm presented around 355 publications in the more than four decades of his work. They extend from antiquity to the 20th century and are thematically diversified from the medieval history of the emperors and the popes to the social and economic history of the bourgeoisie. Schramm had three fields of work: Medieval history, history of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie and history of the Second World War. His focus of work remained the Middle Ages from 1920 to 1938/39, during the Second World War this area took a back seat. In the 1940s, the two subject areas of Hamburg history and contemporary history became increasingly important. Around 1967 he established that his scientific work had continuously "unfolded" through all the breaks and upheavals in German history. His colleague from Göttingen, Hermann Heimpel, confirmed this. On the other hand, his biographer David Thimme was able to show how Schramm made time-related corrections in the Weimar Republic, National Socialism and in the Federal Republic of Germany, because "the science of history, due to its constructive character, is always related to the present, to its problems and challenges".

middle Ages

One of Schramm's main research achievements is the discovery and consistent use of images as sources for the intellectual, cultural and political history of the Middle Ages. He did pioneering work in German medieval research. His studies on the utilization of pictorial monuments and symbols of rule as sources are considered groundbreaking. As early as 1928, he praised the images of rulers as an "informative historical testimony", since "the images of rulers [are] the clear expression of all the ideas that were linked to German kingship and empire in the early Middle Ages". Warburg and his "cultural studies library" had a great influence on the young Schramm. However, Warburg's cultural theory lost importance in Schramm's methodology. Influenced by his doctoral supervisor Karl Hampe, Schramm interpreted images increasingly “as clear signs of domination”.

Schramm has often broken new scientific ground. He interpreted the history of the monarchy “not in the conventional way in terms of the development of power, but of its self-portrayal, from the coronation to the foundations of rule”. Not the history of events, but coronation rites, symbols of power and representations of rulers provided him primarily with the information that he used to explain the monarchy. The focus of his work also included the afterlife of antiquity in the Middle Ages and the influence of Byzantium on the West.

The preoccupation with the images of the rulers caused Schramm to take into account insights from art history, numismatics , sphragistics and other subjects. The interdisciplinary approach was a matter of course for him from the start. In doing so, he went far beyond the previous practice of historical science.

Schramm favored an interpretation of history that in no way excludes an intention to have a political effect, but remains scientific. He saw Leopold Ranke as a role model for his understanding of history . This historian has succeeded in combining politically relevant statements with an objective view of history. For Schramm, the Middle Ages were a high point in German history. In doing so, he remained stuck with the common thought patterns of his time from a medieval imperial glory. The experiences of the lost First World War were decisive for the turn to the Middle Ages. Schramm's enthusiasm for the Middle Ages offered him a contrast to the present of the post-war period, when Germany appeared torn inside and outwardly weak. The preoccupation with the Middle Ages helped to answer the question of what actually was “German”.

With his dissertation studies on the history of Emperor Otto III. (996–1002) , when asked "What did Emperor Otto III want?", Schramm tried to shed light on the intellectual and historical context and the political actions of the ruler by clarifying the ideas prevailing at the time. His portrayal of Kaiser, Rome and Renovatio , presented in 1929, is considered to be his best known and most important work. In it, the reign of Otto III. the largest room. Schramm's view of the history of ideas broke with the historical image of a national direction which the government of Otto III. rated negatively from a power-political point of view. Schramm countered the accusation of the older research that Otto had let himself be guided by a unrealistic, fantastic crush on Italy by showing the emperor's planned renovation policy. Schramm saw the idea of the renewal of the Roman Empire, which aimed at restoring the ancient Roman Empire, as the core of this policy. Schramm considered the most important evidence of the introduction of a lead bull in April 998, whose motto was Renovatio Imperii Romanorum . The lead bull replaced the wax seals used until then to authenticate Otto's documents. Schramm's new point of view initially found it difficult to assert itself against the previous judgments in the professional world. Schramm's teacher Hampe, of all people, took a stand against his pupil's view in 1932 in his monograph “High Middle Ages”. Hampe continued to judge medieval rulers according to whether they could be held responsible for maintaining or decaying central monarchical power. Even before his account was published, Hampe explained his traditional point of view in detail in the “Historisches Zeitschrift”. For Hampe Otto was the “gifted, imaginative boy who was over-sensitive to all great impressions” and who misunderstood the demands of power politics.

After the idea of the emperor had been at the center of Schramm's research in the 1920s, towards the end of the 1920s he turned primarily to images of the emperor. In the following decade his interest shifted from imperialism to the ordines for the coronation. After 1945 he began to research the symbols of power. In doing so, he moved away from the pre-war question about the “spirit” of the peoples and turned his attention - in line with a typical interest of the time - to European commonalities. His main works in this area include signs of rule and state symbolism , which appeared from 1954 to 1956 in the MGH series of publications. In 1958 he published the representation Sphaira, Globus, Reichsapfel for the medieval symbols of rule . It formed the preliminary end point of his research on this complex of topics. By researching the symbols of rule, Schramm followed up on his teacher Warburg. He wanted to decipher the symbolic language of the symbols of power and thereby obtain information about the thinking on which it is based. As recently as 1956, he made it clear in rulers and state symbols how much his research was shaped by Warburg's suggestions. Schramm's explicit emphasis on his influence by Warburg "also served him to explain the breaks in his own biography as continuities." More than Warburg, Schramm emphasized the independence of the Middle Ages in cultural development. For him, the Middle Ages were not an extension of earlier epochs, but rather produced their own symbols.

Hamburg history

Schramm is considered a pioneer of Hanseatic cultural and family history. His important monographs on Hamburg's history total over 3000 pages. Hamburg, Germany and the world are considered important works . Achievement and limits of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in the time between Napoleon I and Bismarck (1943) and his two-volume family history, nine generations. Three hundred years of German “cultural history” in the light of the fate of a Hamburg bourgeois family (1648–1948) (1963/64). The history of his family was also the history of Hamburg, as his ancestors had been part of the city's leadership for several generations and helped shape its politics. In his research on Hamburg's history, Schramm relied on a material-rich family archive. This personal proximity to the sources also made it difficult for the historian to distance himself from the tradition. Schramm enriched the understanding of Hamburg's history from 1650 to 1950 with important insights in the fields of economic, social and cultural history. Even before women's studies entered history, he devoted himself to the role of women in civil society. He arranged his topics in German and overseas contexts, which aroused national interest. He understood the history of Hamburg primarily as a business history.

During the compulsory academic break in 1939, Schramm tackled his urban history projects. In 1939 he compiled the article The History of the Oswald Family - O'Swald for the first time with the help of his personal Hamburg archive . The article was published in 1939 in the anthology On the history of German trade with East Africa by the Hamburg economic historian Ernst Hieke . Schramm, together with Hieke, wanted to emphasize the contributions made by the Hamburgers to the early commercial development of Africa. The colonial question had meanwhile gained political importance when Hitler demanded the return of the former German colonies in 1937. During this time the number of colonial scientific publications increased. The current reference to the day was also made clear in Schramm's Göttingen lecture The German Part of Colonial History up to the Founding of Own Colonies . Schramm spoke of the “robbery of the colonies” that Germany suffered. When describing the colonial activity, Schramm paid special tribute to the merchants of the Godeffroys , Woermanns and O'Swalds families . This would have created the basis for the fact that, since Bismarck's colonial acquisition, “Germans could live across sea on German soil”.

Schramm had completed the manuscript of Hamburg, Germany and the world in 1943. Shortly after the Second World War, the collection of sources he had compiled was published by Merchants at Home and by Sea. Hamburg evidence of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries (1949). In 1950 he published the colonial history work Deutschland und Übersee. The illustration ends with the establishment of own German colonies in the 1880s. Schramm's remarks were based primarily on family documents that led to Mexico, Brazil and especially Africa. With his work he not only wanted to present the early colonial trade in Hamburg, but also to give a picture of Germany's overseas activities as a whole. His presentation fully reflected the attitude of his ancestors to colonial questions and Africa. He described the German colonial rulers as "honorable merchants" who were not successful through the slave trade. At the same time, he took a position on the criticism of the victorious powers of 1918, which denied the Germans the qualification to own colonies. The Germans are just as entitled to land in Africa as the British, French or Spaniards. For him, Africa was the epitome of “barbarism”. “Nowhere else was there an equally diabolical alliance between sadism, bestiality, orgiasm and magical misbelief.” He regarded the Europeans as bringing about progress. The natives would go through a "transformation" by building plantations. Schramm praised the positive influence that the Hamburg company Godeffroy had on Africans. The statements of an Englishman from 1874 about the Africans confirmed Schramm's personal judgment: “They arrive dirty, wrong and wild: after six months of planting they no longer look like the same creatures, and by the time their contracts expire they have advanced so far that they are just as unsuitable for fellowship with the brutal brothers in their homeland, as they were formerly for touching the civilized world. "

Schramm did not see his remarks on German colonial activities burdened by the Nazi ideology and stuck to his judgments and evaluations after 1945. A critical discussion in the history of Schramm's book Deutschland und Übersee can hardly be heard. The colonial valuation of Africa was not slowly questioned until the late 1960s. In his work Hamburg, Germany and the world , the focus is on Justus Ruperti , the businessman and president of the Commerzdeputation, and his brother-in-law Ernst Merck , head of a banking and trading company and one of three Hamburg members in the Frankfurt National Assembly . Both are Schramm's maternal ancestors. With the book Hamburg, Germany and the World , he wanted to set a memorial to the “bourgeoisie grounded in this war between the millstones of world history” and at the same time give an account of its origins.

His work Nine Generations , published in 1963/64 . Three hundred years of German “cultural history” in the light of the fate of a Hamburg bourgeois family (1648–1948) treats the history of Hamburg using the life and fate of four members of his family: the lawyers Eduard and Max Schramm and the merchants Adolph and Ernst Schramm.

The city gained identity and historical awareness through Schramm's work. He was involved in the Hanseatic History Association . From 1927 he belonged to this association, in 1950 he became a member of the board and in 1967 an honorary member of the association. For his services to Hamburg history, he was awarded the Lappenberg Medal in gold in 1964 on the 125th anniversary of the Association for Hamburg History . In the lecture he gave on this, Schramm presented the Hamburg thesis as a special case in history. Schramm saw in the history of Hamburg “from the 16th century to 1914 no retrograde phase, not even one of standstill”. In 1964 the Senate of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg awarded him the Medal for Art and Science of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg .

Second World War

Schramm's edition of the war diary is still an essential source for depicting the Second World War. In addition to this edition, he had already dealt with the history of the Second World War since the late 1940s. He has published work on numerous aspects of war history : history of the Second World War (1951); The fuel question 1943–1944 (1954); The 1944 Invasion (1959); Hitler as a military dictator (1961); Hitler as a military leader (1962). The focus was on the history of military events. For the first time he gave a lecture on The History of the World War in the winter semester of 1952/53 . It met with a great public response with 900 to 1000 listeners and was repeated every two years. His war history followed the approach of a Wehrmacht officer. The crimes of the Wehrmacht were left out.

Schramm's political and journalistic work was determined by the endeavor that an event like the Second World War should not happen again and that a possible stab-in-the-back legend should be prevented. After 1945, however, there were no reflections on the role of historians or even on one's own misconduct. After the war he dedicated himself to demonizing and pathologizing National Socialism, especially as " Hitlerism ". He did not see the death of millions of Jews as a "historical problem", but the "seduction of millions" by Hitler. Schramm repeatedly called for people to see through "Hitler's pied piper" and to "prevent a catastrophe like that of World War II". His thesis of Hitler's “double-faced and enigmatic” could serve to justify the behavior of even the “most loyal”; it was analyzed as an " apologetic construction" in a study by Nicolas Berg (2003) . His remarks on Hitler's character image were published in a large “ Spiegel ” series “Anatomy of a Dictator” in the spring of 1964 , and were widely approved. Such a perspective when dealing with the National Socialist past was by no means unusual in the post-war decades. Even then, Schramm's letters to the editor, in which he portrayed Hitler in isolation as a seducer of the people, met with criticism. He ignored the role of the population and, above all, the share of the German elite in the Nazi regime. According to his biographer Thimme, Schramm's publication is “perhaps an expression of a turning point in the history of the German way of dealing with the National Socialist past”. In the last years of his life, Schramm was less concerned with the Second World War.

effect

Scientific aftermath

Schramm's work exerted an early influence on younger historians such as Wilhelm Berges and Hans-Walter Klewitz . Schramm's student Reinhard Elze published an edition of the Ordines of the Imperial Coronation in 1960 and thus brought a project by his teacher to a close.

In 1975 Helmut Beumann gave an overview of German Medieval Studies. In addition to research on constitutional history, he saw the greatest achievement in post-war medieval studies in the "history of political ideas", i.e. the investigation of the intellectual backgrounds of political action. At the same time, Schramm's work on the testimony of rulership symbols provided impulses and was fundamental.

The research in the field of intercultural transfer processes, which has been intensified since the 1980s, recognized Schramm as a source of ideas. Medieval studies remembered Schramm as a representative of “question-led, detail-obsessed research”.

Schramm's book Kaiser, Rom und Renovatio had an enormous impact. In 1957 a second edition was published, a photo-mechanical reprint of the 1929 edition with supplements. The fifth and so far last edition was published in 1992. The book remained unchallenged in its basic theses for decades. It was not until the 1990s that Schramm's interpretation of Otto III's self-portrayal became popular. increasingly criticized. Knut Görich (1993) evaluated the renovatio motto not as a program of rule, but as a short-term reaction to current political changes in Rome. Gerd Althoff (1996) fundamentally criticized research that draws conclusions from political events to concepts; this is premature, since important prerequisites are missing with the written form and the implementing institutions.

Schramm's understanding of Hamburg's history is also no longer undisputed. His statements about the early modern social structure of the city are classified as too harmonizing. Schramm's image of an open civil society without social barriers, in which "from the mayor to the last man in the port" all Hamburgers are just one class, is seen as in need of correction. Recent studies have also shown that Schramm's image of Hamburg as a city that experienced an unchecked rise in the history of the city from the 16th century to 1914 received some additions and restrictions for the 18th century and especially for the “ French era ” got to.

Research on the history of science

Nowadays Schramm's remarks are themselves considered a historical source of science , as they show the point of view of a modern historian, whose origins can be traced back to the colonial era.

In 1987, the history of the University of Göttingen under National Socialism was systematically examined for the first time. Robert P. Ericksen found that Schramm's historical interests were "congenial with right-wing, and therefore also indirectly with National Socialist politics". Ericksen raised the question of whether Brandi and Schramm were really interested in unbiased research or whether they were primarily interested in politically exploitable results. According to Ericksen, who relies on statements from various contemporary witnesses, Schramm “liked to walk through Göttingen in his equestrian SA uniform with riding whip and boots”. Ericksen judges Schramm's behavior that he “served the National Socialist state in peace and in war, clearly without hesitation”.

Schramm's student Joist Grolle commented on these statements two years later. On April 9, 1989, Grolle gave the lecture on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Association for Hamburg History . The lecture dealt with the historian's attachment to the present and his limited perception of his own time. Grolle dealt extensively with Schramm's behavior during the Nazi era and summed up: "If you look closer, you come across a man who doesn't fit into the clichés of subsequent black and white painting." Grolle overestimated some formulations in Hamburg, Germany and the World (1943) the emancipation of Jews in Hamburg as “concessions to the spirit of the times and the circumstances of the times”. Grolle found the picture of Hamburg's Jews drawn there “mostly friendly”. He even considered the book to be "an amazing document of covert criticism of the regime". Ursula Wolf (1996) judged differently. In Hamburg, Germany and the world she saw a “substructure” which expressed Schramm's “at least selective and temporary approval” of the Nazi ideology. Wolf accused Schramm of “a lack of resistance to National Socialist ideas”. In his controversial account of 20th century medieval studies, the American medievalist Norman Cantor went so far as to equate Schramm with the convicted war criminal Albert Speer .

Grolle published further studies on Schramm's work on the history of Hamburg and followed the breakup of his friendship with Saxl. Schramm paid tribute to the importance of Hamburg historical research with the words: "No recent author has shaped the historical image of the Hanseatic city so much [...]"

In 2006 David Thimme presented the most comprehensive work on Schramm to date. Thimme examined the connections between the developing mediaeval work of Schramm and the life story of the scholar. Wolfgang Hasberg (2011) asked about the contribution of medieval research from 1918 to 1933 to cultural history and dealt extensively with Schramm.

Fonts (selection)

A directory of Schramm's writings up to 1962, edited by Annelis Ritter, was published in: Peter Classen , Peter Scheibert (ed.): Festschrift Percy Ernst Schramm was dedicated to his seventieth birthday by students and friends. Volume 2. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 281–316 (corrected and supplemented in: David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm und das Mittelalter. Changes in an image of history (= series of publications of the Historical Commission at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Vol. 75). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-36068-1 , pp. 629-637).

Monographs

- Emperor, Rome and Renovatio. Studies and texts on the history of the Roman idea of renewal from the end of the Carolingian Empire to the Investiture Controversy (= Studies of the Warburg Library. Vol. 17, 1–2, ZDB -ID 251931-8 ). 2 volumes (Vol. 1: Studies. Vol. 2: Excursions and texts. ). Teubner, Leipzig et al. 1928 (2nd edition, special edition, photomechanical reprint of the edition from 1929. Gentner, Darmstadt 1957; also: reprint of the edition from Leipzig 1929. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1992, ISBN 3-534-00442-6 ).

-

Signs of rule and state symbolism. Contributions to their history from the third to the sixteenth century (= writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Vol. 13, 1–3, ZDB -ID 964449-0 ). With contributions from other authors. 3 volumes. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1954–1956.

- in addition: rulership and state symbolism. Supplements from the estate (= writings of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Vol. 13, supplementary volume). Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-921575-89-3 .

- Sphaira, globe, orb. Migration and change of a symbol of rule from Caesar to Elizabeth II. A contribution to the “afterlife” of antiquity. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1958.

- Nine generations. Three hundred years of German “cultural history” in the light of the fate of a Hamburg bourgeois family (1648–1948). 2 volumes. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1963–1964.

- Germany and overseas. German trade with the other continents, especially Africa, from Charles V to Bismarck. A contribution to the history of rivalry in business life. Westermann, Braunschweig et al. 1950.

- Win and loss. The history of the Hamburg senatorial families Jencquel and Luis (16th to 19th centuries). Two examples of the economic and social change in northern Germany (= publication by the Association for Hamburg History. Vol. 24, ISSN 0931-0231 ). Christians, Hamburg 1969.

Editorships

- Henry Picker: Hitler's Table Talks in the Führer Headquarters 1941–1942. Newly published on behalf of the publisher by Percy Ernst Schramm, in collaboration with Andreas Hillgruber and Martin Vogt. Seewald, Stuttgart 1963.

- War diary of the Wehrmacht High Command (Wehrmacht command staff). 1940-1945. 4 (in 8) volumes. Run by Helmuth Greiner and Percy Ernst Schramm. On behalf of the Working Group for Defense Research . Bernard & Graefe, Frankfurt am Main 1961–1969.

literature

Necrologist

- Ahasver von Brandt : Percy Ernst Schramm †. [Obituary]. In: Hansische Geschichtsblätter . Vol. 89 (1971), pp. 1-14.

- Reinhard Elze : Nekrolog. Percy Ernst Schramm. In: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages . 27: 655-657 (1971). Digitized .

- Heinrich Fichtenau : Percy Ernst Schramm. In: Almanac of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. 121: 368-372 (1971).

- Hermann Heimpel : royalty, change in the world, bourgeoisie. Obituary for Percy Ernst Schramm. In: Historical magazine . 214: 96-108 (1972).

- Hans Patze : Percy Ernst Schramm in memory. In: sheets for German national history . Vol. 107 (1971), pp. 210-211 ( digitized version ).

- Reinhard Wenskus : Obituary for Percy Ernst Schramm October 14, 1894 - November 12, 1970. In: Yearbook of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences. 1971 (1972), ISSN 0373-9767 , pp. 51-54.

Representations

- János Bak: Percy Ernst Schramm (1894–1970). In: Helen Damico, Joseph B. Zavadil (eds.): Medieval Scholarship. Biographical Studies on the Formation of a Discipline. Volume 1: History (= Garland Reference Library of the Humanities. Vol. 1350). Garland Publishing, New York NY et al. 1995, ISBN 0-8240-6894-7 , pp. 247-262.

- Peter Classen , Peter Scheibert (eds.): Festschrift dedicated to Percy Ernst Schramm on his seventieth birthday by students and friends. 2 volumes. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1964.

- Ernst Schubert: Schramm, Percy Ernst. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 27, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018116-9 , pp. 279-285.

- Joist Grolle : Percy Ernst Schramm - a special case in the history of Hamburg. In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History . Vol. 81, 1995, pp. 23-60. ( online )

- Joist Grolle: Schramm, Percy Ernst . In: Franklin Kopitzsch, Dirk Brietzke (Hrsg.): Hamburgische Biographie . tape 1 . Christians, Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-7672-1364-8 , pp. 276-278 .

- Joist Grolle: Percy Ernst Schramm from Hamburg. A historian in search of reality (= lectures and essays. Vol. 28). Association for Hamburg History, Hamburg 1989, ISBN 3-923356-32-3 ( excerpts appeared in the newspaper Die Zeit ).

- Eckart Henning : "Making the invisible visible". In remembrance of Percy Ernst Schramm's “Signs of Power”. In: Herold Yearbook . NF Vol. 12, 2007, ISSN 1432-2773 , pp. 51-60.

- Manfred Messerschmidt : Karl Dietrich Erdmann, Walter Bußmann and Percy Ernst Schramm: Historians at the front and in the high command of the Wehrmacht and the Army. In: Hartmut Lehmann , Otto Gerhard Oexle : National Socialism in the Cultural Studies. Volume 1: Subjects - Milieus - Careers (= publications by the Max Planck Institute for History. Volume 200). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-35198-4 , pp. 417-446.

- Frank Rexroth : Making history in an age of extremes. The Göttingen historians Percy Ernst Schramm, Hermann Heimpel and Alfred Heuss. In: Christian Starck, Kurt Schönhammer (Hrsg.): The history of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. NF Vol. 28). Volume 1. De Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2013, ISBN 978-3-11-030467-1 , pp. 265-299.

- Hans Martin Schaller : Schramm, Percy Ernst. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , pp. 515-517 ( digitized version ).

- David Thimme: The memories of the historian Percy Ernst Schramm. Description of a failed attempt. In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History. Vol. 89, 2003, pp. 227-262 ( online ).

- David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in a historical image (= series of publications by the Historical Commission at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences. Vol. 75). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-36068-1 (At the same time: Gießen, University, dissertation, 2003/2004).

- Reviews of Thimme: Patrick Bahners : I am also a book painter. The legend of the historian: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Warburg Library. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . No. 230, October 4, 2006, p. L40 ( online ); Christoph Auffarth in: Yearbook of the Society for Church History of Lower Saxony . Vol. 106, 2008, ISSN 0072-4238 , pp. 255-257; Wolfgang Hasberg in: The historical-political book. Vol. 55, 2007, pp. 561-563; Hans-Christof Kraus in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 90 (2008), pp. 497–500; Rudolf Schieffer in: German Archive for Research into the Middle Ages. Vol. 63, 2007, pp. 639-640 ( online ); Bernd Schneidmüller in: Archive for Social History . Vol. 50, 2010, ( online ); Jörg Wollenberg in: Social.History. Journal of historical analysis of the 20th and 21st centuries . Vol. 22, 2007, ISSN 1660-2870 , pp. 171-174; Eckart Henning in: Herold yearbook. NF Vol. 12, 2007, pp. 257-259; Ludger Körntgen in: H-Soz-u-Kult , March 4, 2008, ( online ); Joist Grolle in: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History. Vol. 93, 2007, pp. 311-313 ( online ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Percy Ernst Schramm in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by and about Percy Ernst Schramm in the Opac der Regesta Imperii

- Life, writings, literature about PE Schramm

- Employee at the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (MGH) Munich

- Nuremberg Trial of the Main War Criminals, Person Index: Schramm

- Video: Percy Ernst Schramm, Göttingen 1964/65 . Institute for Scientific Film (IWF) 1965, made available by the Technical Information Library (TIB), doi : 10.3203 / IWF / G-100 .

Remarks

- ^ Percy Ernst Schramm: Nine Generations. Three hundred years of German “cultural history” in the light of the fate of a Hamburg bourgeois family (1648–1948). 2 vol., Göttingen 1963–1964.

- ↑ On Aby Warburg as Schramm's teacher, cf. David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 44-51.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 224; David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 52.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 223. David Thimme in detail on his origin: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 37-60.

- ^ Excerpt from the German lists of losses (Preuss. 268) of July 7, 1915, p. 7453 .

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 66, 518.

- ↑ Eduard Mühle : Hans Rothfels, Percy Ernst Schramm, the 'Ostraum' and the Middle Ages. To some new historiographical publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research. Vol. 57, 2008, pp. 112-125, here: pp. 121 f. ( online ).

- ↑ On the war years cf. David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 21-23, 61-85. For the front generation cf. also Ernst Schulin : World War II experience and historians' reaction. In: Wolfgang Küttler , Jörn Rüsen , Ernst Schulin (Hrsg.): Geschichtsdiskurs. Vol. 4: Crisis Awareness, Disaster Experience and Innovations 1880–1945. Frankfurt am Main 1997, pp. 165-188.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 79.

- ↑ Eduard Mühle: Hans Rothfels, Percy Ernst Schramm, the 'Ostraum' and the Middle Ages. To some new historiographical publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research. 57, 2008, pp. 112–125, here: p. 122. ( online ).

- ^ Percy Ernst Schramm: Nine Generations. Three hundred years of German “cultural history” in the light of the fate of a Hamburg bourgeois family (1648–1948). Göttingen 1964, p. 508.

- ↑ Percy Ernst Schramm: The Kapp Putsch in Hamburg, March 1920, based on a report by Senator Dr. Max Schramm to the Ambassador Dr. Friedrich Sthamer and the diary of his son, the then cand. Phil. Percy Ernst Schramm , edited by him as now professor of history. In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History. 49/50, 1964, pp. 191-210.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 168.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 97-102, 107-109, 553.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 187; David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 206 ff.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 279.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 225.

- ↑ Eduard Mühle: Hans Rothfels, Percy Ernst Schramm, the 'Ostraum' and the Middle Ages. To some new historiographical publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research . Vol. 57, 2008, pp. 112-125, here: p. 122 ( online ); David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 197-199.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 615.

- ↑ On the Heidelberg years cf. David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 189-225.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Nobert Kamp: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages research. In: Hartmut Boockmann , Hermann Wellenreuther (Hrsg.): History in Göttingen. A series of lectures. Göttingen 1987, pp. 344-363, here: pp. 344-348.

- ↑ Antti Matikkala: Percy Ernst Schramm and domination characters. In: Mirator 13/2012, pp. 37-69. here: p. 42 f. ( online ). Percy Ernst Schramm: Notes on a visit to Doorn (1930). In: Konrad Repgen , Stephan Skalweit (Hrsg.): Mirror of history. Festgabe for Max Braubach on April 10, 1964. Münster 1964, pp. 942–950.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 306.

- ↑ Robert P. Ericksen: Continuities of Conservative Historiography at the Seminar for Medieval and Modern History: From the Weimar Period through the National Socialist Era to the Federal Republic. In: Heinrich Becker, Hans-Joachim Dahms, Cornelia Wegeler (eds.): The University of Göttingen under National Socialism. 2nd, extended edition, Munich 1998, pp. 427–453, here: p. 435.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 314-319; Eduard Mühle: Hans Rothfels, Percy Ernst Schramm, the 'Ostraum' and the Middle Ages. To some new historiographical publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research. 57, 2008, pp. 112-125, here: pp. 122f. ( online )

- ↑ On this article cf. David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 242-249.

- ^ Nobert Kamp: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages research. In: Hartmut Boockmann, Hermann Wellenreuther (Hrsg.): History in Göttingen. A series of lectures. Göttingen 1987, pp. 344-363, here: pp. 353 f.

- ^ Joist Grolle: The Hamburger Percy Ernst Schramm. A historian in search of reality. Hamburg 1989, p. 23 f .; David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 361.

- ↑ Folker Reichert: Learned life. Karl Hampe, the Middle Ages and the history of the Germans. Göttingen 2009, p. 238.

- ↑ Ursula Wolf: Litteris et Patriae. The Janus face of history. Stuttgart 1996, p. 324 f .; Joist Grolle: Percy Ernst Schramm from Hamburg. A historian in search of reality. Hamburg 1989, p. 26 f.

- ↑ Eduard Mühle: Hans Rothfels, Percy Ernst Schramm, the 'Ostraum' and the Middle Ages. To some new historiographical publications. In: Journal for East Central Europe Research. 57, 2008, pp. 112–125, here: p. 123. ( online )

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 340, 341, 348.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 377; David Thimme: The memories of the historian Percy Ernst Schramm. Description of a failed attempt. In: Journal of the Association for Hamburg History. 89, 2003, pp. 227-262, here: p. 253 ( online ).

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 314, 333.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 338.

- ^ Karen Schönwälder : Historians and Politics. History in National Socialism. Frankfurt am Main et al. 1992, p. 294.

- ↑ Ursula Wolf: Litteris et patriae. The Janus face of history. Stuttgart 1996, pp. 119, 323; Joist Grolle: Percy Ernst Schramm from Hamburg. A historian in search of reality. Hamburg 1989, p. 24 f.

- ↑ To this letter in detail David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm und das Mittelalter. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, pp. 352-356.

- ^ Joist Grolle: The Hamburger Percy Ernst Schramm. A historian in search of reality. Hamburg 1989, pp. 30-32.

- ↑ David Thimme: Percy Ernst Schramm and the Middle Ages. Changes in an image of history. Göttingen 2006, p. 464 f.