Potawatomi

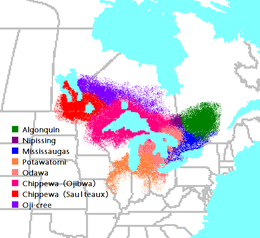

The Potawatomi (also Pottawatomie or Pottawatomi ) are an Indian tribe of Algonquin - language family from the region of the upper Mississippi River . Culturally and historically, the Potawatomi belong to the tribal group of the Anishinaabe (g) ("First People", "Original People", or "Beings Created from Nothing"), who spoke different variants and dialects of the Anishinaabemowin - which is also the Anishinabe (Ojibwe or Chippewa) , Saulteaux (Salteaux) , Mississauga , Odawa (Ottawa) , Algonkin (Algonquin) , Nipissing and Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibwa) .

Today there are nine First Nations in Canada and eight federally recognized tribes in the United States of the Potawatomi or with a large Potawatomi population; the Potawatomi today number around 28,000 tribesmen.

Surname

The Potawatomi called and still call themselves “Neshnabé” (without syncope : “Eneshenabé”, plural: “Neshnabék”), a word equation of Anishinaabe (g) and Nishnaabe (g) , the self-designation of Anishinabe (Ojibwe or Chippewa) and Odawa ( Ottawa) .

The Potawatomi belonged to the Council of Three Fires (" Council of Three Fires ", in Anishinaabemowin: Niswi-mishkodewin ), a loose, powerful alliance with neighboring Anishinabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) and Odawa (Ottawa).

The name "Potawatomi" is derived from Potawatomink (g) or Boodewaadamii (in Odawa ( Nishnaabemwin, Daawaamwin ) : Boodwadmii (g) ), the name of the neighboring Anishinabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) for the Neshnabék , and means something like " Keeper of the Hearth Fire, ”referring to the Council of Three Fires Council Fire. The Neshnabék took over the name and since then mostly called and call themselves Bodéwadmi (without syncope: Bodéwademi , plural: Bodéwadmik , derived from: bodewadm or bodewadem - "to preserve / guard the hearth").

language

The Potawatomi (also Neshnabémwen , sometimes Bodéwadmimwen , Bodéwadmi Zheshmowen - "Potawatomi language") is closely related to the language of the Ojibwe ( Anishinaabemowin ), Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi, Menominee ( Omāēqnomenew ), Miami-Illinois ( Myaamia ) Mesquakie- Sauk-Kickapoo ( Meshkwahkihaki ), which is closest to the Ojibwe - however, it is not a dialect of the Ojibwe, as was previously assumed. It not only has parallels in sound and structure with the southern Ojibwe and Odawa ( Nishnaabemwin, Daawaamwin ), but also shares numerous similar vocabulary with the Fox , Sauk and Kickapoo dialects.

There are two regional dialect groups within the Neshnabémwen (Potawatomi) : Southern Potawatomi in Kansas and Oklahoma and Northern Potawatomi in the Great Lakes area .

Some western Potawatomi today use certain aids in their rituals in the form of pictograms that are drawn on birch bark. This way, long and complex religious ceremonies are better remembered. Charles F. Hockett developed a phonetic alphabet for the Potawatomi language in 1960, but it found neither widespread acceptance nor practical use. A second system was developed in 1974 by John Nichols together with the Forest County Potawatomi of Wisconsin .

In the 1970s, the Potawatomi moved numerous people to other, often distant, communities. Tribesmen mingled with white Americans, Menominee , American and Canadian Chippewa and Odawa, and Kansas Kickapoo , for example . In addition, many elderly Potawatomi speakers lived in the cities with their English-speaking children and grandchildren and had no opportunity to use their traditional language. By 1970 there were only a few places left where Potawatomi was spoken. Presumably they did not number more than 1,000 people, most of them in the Kansas Potawatomi and Kickapoo Reservations (350) and in Oklahoma (200).

Council of Three Fires

Once the various Anishinaabemowin-speaking Anishinaabe (g) were a people or a union of closely related bands ( English " tribal groups ") from northeast North America, the Anishinaabe (g) split into a northern group ( Algonquin (Algonquin) , Nipissing , Mississaugas) and Oji-Cree (Severn Ojibwa) ) and into a southern group - with the southern group ( Anishinabe (Ojibwe or Chippewa) , Odawa (Ottawa) and Potawatomi) maintaining a close political-military unit and the core of the alliance of the Council of Three fires formed.

The individual members of the alliance developed independent identities as Anishinabe, Odawa and Potawatomi , at the latest when they reached Michilimackinac on their wanderings from the Atlantic coast to the west .

Within the alliance, the Anishinabe (Ojibwe or Chippewa) were considered to be the "Oldest Brother" and the "Keeper of the Faith", the Odawa (Ottawa) as the "Middle Brothers "('Middle Brother') as well as" Guardians of the Trade "('Keepers of the Trade') and the Potawatomi as" Youngest Brothers "('Youngest Brother') as well as" Keepers of the hearth "('Keepers / Maintainers of / for the Fire '). Hence, when the three Anishinaabe nations are mentioned one after the other in this particular series, it is always an indication that it is mostly referring to the Council of Three Fires as a whole.

Although the Alliance had several meeting places, Michilimackinac became the preferred place for the council of the allied tribes because of its central location. Here they met to discuss war, peace and politics as well as trade and diplomacy; In addition, from there they maintained contact with the relatives - and often allies - Ozaagii ( Sauk ), Odagaamii ( Fox ), Omanoominii ( Menominee ), Wiinibiigoo ( Ho-Chunk ) and the Iroquois-speaking Nii'inaawi-Naadawe (also: Nii 'inaa-Naadowe - the "Naadawe / Nadowe (Iroquois) within our tribal area", i.e. the Wyandot , as they often settled under them) and the Wemitigoozhi ( New France ). The enemies of the Council of Three Fires therefore included first the Zhaaganaashi ( British Empire ) and their allies the Naadawe ( Iroquois League ) and the Naadawensiw or Natowessiw ( Sioux ) and later the Gichi-mookomaan ( United States ).

Most of the time, however, the allied tribes were able to maintain peace with the neighboring peoples through trade and diplomacy, but during the so-called Beaver Wars (including French and Iroquois Wars , from 1640 to 1701) and due to the growing settlement pressure, the settlers advancing to the west became violent and particularly gruesome armed conflicts with the Iroquois League and the Sioux . During the French and Indian War (also: Great War for the Empire or Guerre de la Conquête , from 1754 to 1763) the Alliance fought together with the Wabanaki Confederation , the Shawnee , Algonquin , Lenni Lenape and the Seven Nations of Canada ( Tsiata Nihononwentsiake - "Seven Fires Alliance", also The Great Fire of Caughnawaga ) ( Wyandot , Mohawk from Akwesasne, from Kahnawake and from Kanesetake (including Algonkin and Nipissing ), Abenaki from Odanak and from Becancour (now Wôlinak) and Onondaga from Oswegatchie) Against england; during the Northwest Indian War (also Little Turtle's War , from 1785 to 1795) for the Northwest Territory and in the British-American War (mostly War of 1812 ) they then fought against the United States.

After the founding of the United States of America in 1776, the Council of Three Fires formed the centerpiece of the newly formed pan-Indian Western Confederacy (also known as the Western Indian Confederacy ), made up of members of the Iroquois League, the Seven Nations of Canada, the Wabash Confederacy (Wea, Piankashaw, as well as Kickapoo and Mascouten ), the Illinois Confederation as well as the Miami , Mississaugas, Wyandot, Menominee, Shawnee, Lenni Lenape, Chickamauga Cherokee (Lower Cherokee) and Upper Muskogee . The Algonquin, Nipissing, Sauk, Fox (Meskwaki) and other tribes also took part in these battles.

The Council of Three Fires was one of the most important and powerful tribal confederations, also known as the People of the Three Fires ; Three Fires Confederacy or known as the United Nations of Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians .

In the east, the alliance was often allied with the related Mississaugas (derived from Missisakis - "many estuaries") and the various tribal confederations of the Algonquin - in particular the Wabanaki confederation and the eastern Cree groups.

Integration into the Cree Confederation (Nehiyaw-Pwat)

When the Saulteaux (Anihšināpē) moved further west and southwest into the Prairie Provinces of Canada and the Northern Plains of the United States in the 1770s, they developed a horse- based nomadic Plains culture , went bison hunting, and became known as the Plains Ojibwe / Plains Ojibwa known.

There they joined the powerful Cree - Assiniboine - Confederation (in Cree : Nehiyaw-Pwat - "Cree-Assiniboine", in English also: Iron Confederacy ). The Cree ('Nehiyaw') and Assiniboine ('Pwat-sak', including the Stoney ) represented the majority within the Confederation, followed by the Saulteaux / Plains Ojibwa (in Cree: 'Soto'). In addition to these three dominant ethnic groups, smaller bands from neighboring tribes (Chipewyan, Daneẕaa, Kutenai, Flathead, Secwepemc), Indian traders in the northwest - who ethnically belonged to the Iroquois - as well as Métis who were related by marriage were also among the Nehiyaw-Pwat .

The various Cree, Assiniboine, Stoney and Ojibwa bands of the Nehiyaw-Pwat often married with one another or formed alliances that were strengthened by family ties - so that almost every band in the Iron Confederacy was of mixed ethnicity and language. Many bands were only nominally (in name) Cree ('Nehiyaw'), Nakoda ('Pwat-sak' - 'Assiniboine' - 'Stoney') or Plains Ojibwa ('Soto'), as they were often ethnic and politically indistinguishable from each other. In general, the bands living south on the Plains tended to be mostly nominally Nakoda , the eastern and southeastern bands nominally Soto and the northern and northwestern bands nominally Cree . These designations usually said little about the ethnic and linguistic identity and origin of the so-called bands - there were even groups of the Nakoda and Soto, especially in the northwest and later in the southeast, who were originally Secwepemc, Kutenai, Daneẕaa or even Métis. Important personalities as well as many famous chief families ( Cayen dit Boudreau, Piche, Cardinal, George Sutherland, Belanger ) of the Nehiyaw-Pwat were culturally Indians, but ethnically Métis.

Historically, the term bungi or bungee (from Anishinaabemowin bangii or from Cree pahkl ; both "a little (like)") for both the Manitoba Saulteaux (who are "a little like the Cree") and those from marriages between Red River Métis (which are "a bit like the Saulteaux" (Anihšināpē)) used by Saulteaux and Europeans . The language of their Métis people was also called Bungee (Red River Dialect) . In the Red River Rebellion of 1869 and the later Northwest Rebellion of 1885 , the Red River Métis attempted in vain for themselves and their Indian allies and relatives - most recently bands of the Cree and Assiniboine - their cultural and religious uprisings by means of military and political uprisings as well as being able to preserve linguistic identity.

Residential and hunting area

The Potawatomi inhabited three different areas in the course of their history until they had to move to reservations around 1840 . The first known territory was on the lower Michigan Peninsula and was abandoned around 1641. The second is to be seen as a kind of retreat from the Iroquois threat until a profitable political and economic alliance with the French had developed. The area extended over the entire Door Peninsula , which separates Green Bay from Lake Michigan . During this time, the neighboring forests in Wisconsin served as hunting grounds.

The Potawatomi residential area was not limited to the relatively small peninsula for long. Even before 1670, through the alliance with the French and the acquisition of firearms, they had gained so much power that they were able to expand their tribal territory. Until 1820, their territory grew steadily and included the Door Peninsula, the entire western shore of Lake Michigan south to what is now Milwaukee and Chicago and further east and north to the St. Joseph River and the Grand River in Michigan. It also included parts of southern Michigan on the St. Joseph River and the Detroit area ; furthermore the northern half of Indiana and Illinois , especially the catchment area of the Wabash River and the Kankakee , Des Plaines , Chicago and Illinois rivers . Finally, areas in southern Wisconsin west of Lake Geneva and the Mississippi. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Potawatomi inhabited more than 100 villages in the described area: 14 in northern and central Illinois, 21 in Indiana, 11 in southern Michigan, and more than 80 in Wisconsin. The villages were not all inhabited at the same time, nor were they the same size.

The prehistoric territory in lower Michigan consisted of fertile arable land and woodland, ideal for growing corn, hunting and fishing. The forest area was mostly covered with oak and hickory , as well as birch and maple, in the north there were hardwood and pine forests, interrupted by numerous lakes and in the south there were marshland and open prairie . Given the many waterways, the Potawatomi used the canoe to travel to the hunting grounds.

When the Potawatomi reached their retreat on the Door Peninsula, they came to a country with a harsher climate and a shorter growing season. It was as far north as the French trade and missionary station of Chequamegon , which was visited by a large Potawatomi group in 1668. Although the peninsula was temporarily overpopulated by Algonquin tribes who had fled, the land around Green Bay produced very good harvests. The Indians lived especially from wild rice , from hunting and fishing. Water fowl and buffalo were preferred on the upper Fox River .

The location on Green Bay offered social and strategic advantages. On the one hand, relative security against raids by the Iroquois, on the other hand, direct access to French merchants without intermediaries and the acquisition of French weapons, tools and other goods. In contrast to many other tribes that dwindled in number from contact with Europeans as a result of war and disease, the Potawatomi saw population growth until 1820. By this time their tribal area was at its greatest expansion, and its villages and cornfields covered much of southern Wisconsin and Michigan, as well as northern Illinois, Indiana and northwestern Ohio .

Culture

Way of life in the seventeenth century

In the two centuries from 1642 to 1842, the way of life and culture of the Potawatomi changed significantly. This is particularly true of the early period when the tribe had no contact with Europeans. There are some reports from 1640-1660, but none from the years before the Potawatomi lived in their traditional home and hunting ground in Michigan.

It is certain that Potawatomi, Odawa and Chippewa belonged to a single people with a common culture and language. Originally they lived on the east coast of North America and split up into three groups as they migrated west. The division took place at an unknown point in time on Mackinacstrasse . The group, later named Potawatomi, moved south to the east bank of Lake Michigan in what is now Michigan.

There are only a few archaeological sites that can be clearly assigned to the early Potawatomi culture around 1600. This includes the site on Dumaw Creek in Michigan, which can be seen as an example of the way the Potawatomi lived shortly before the arrival of the French. The Moccasin Bluff Village in Berrien County is probably also part of the Potawatomi, but was inhabited a few years earlier. Both places indicate large summer villages that were built on the edge of the forest, nearby smaller prairies and rivers or lakes. The Potawatomi of that time practiced a seasonally two-part way of life, which consisted of gardening, hunting, fishing and collecting wild edible herbs. In summer they grew squash , beans, corn and tobacco, and gathered a variety of wild plants and fruits. They hunted deer, elk and beaver in the nearby forest. In late autumn they left the summer village, split up and moved to smaller, sheltered winter camps. In the spring they gathered again and held buffalo hunts together in the prairies to the south.

The Potawatomi lived in dome-shaped wigwams , which were made from curved, thin trunks of young trees and covered with woven mats or pieces of bark. Their armament consisted of bows and arrows and lances with triangular flint tips. The villages were built on narrow watercourses and were protected against sudden attacks by palisades .

The Potawatomi made a variety of fired pottery. Their clothing consisted of sewn skins and fabrics made using the braiding technique. They adorned their hair, body, clothing, and other items with paints and ornaments made from native copper from Lake Superior . Other jewelry items were pearls, necklaces and pendants from the Atlantic coast. They smoked tobacco in stone or clay-baked pipe bowls with wooden or reed pipe stems.

The funerals were lavish. The corpse was buried in festive clothing facing east-west and equipped with numerous grave goods such as tools, weapons and food for the journey to the afterlife. The members of the Rabbit Clan (rabbit clan ), who were burned, were an exception .

The Potawatomi kinship system was strictly patrilineal with an associated clan organization that formed the basis of the village community. There was polygamy in the form that a man could marry his wife's sisters. The marriage was matrilocal ; after the marriage, the man moved into his in-laws' house. The system was found to be beneficial for population growth, as demonstrated by facts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The common ownership of a local clan was more supernatural than real. At the time, each group owned a sacred bundle , the contents of which represented the supernatural powers of the clan. In addition, a clan had a collection of names of the ancestors and the associated powers, various ritual utensils and the various visions of its members. The actual possessions, such as canoes, wigwams, weapons and food supplies, belonged to the individual or the family. In every summer village of the Potawatomi there were representatives of the individual clans, grown men, boys and unmarried girls who belonged to the core clan, and women from other villages who had married into the local groups.

Through the exchange of women from the clans of other villages, a local clan was related to other clans. There were also other relationships between the individual villages, such as trade, mutual ritual obligations, and mutual economic and military support. There is no known case of hereditary chief dignity from this period. Leaders of the most important clans were occasionally recognized as head of a large village and served as war chief or negotiator in intertribal contracts. Perrot wrote a report on the political leadership style of the Potawatomi: “The old men were proud, sensible and prudent. It seldom happened that they did unexpected things. "

Culture in the nineteenth century

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Potawatomi inhabited and controlled an area that was far larger than in previous centuries. The most important unit within the tribe was the village, of which there were more than a hundred at that time. These villages were usually referred to by certain landscape features, such as village at the old Redwood Creek (Village of the old red woodcreek), a large village in Indiana. In contrast, the Americans generally referred to the villages after the names of the chiefs there. By 1800 there were no more animal-related clans and a multitude of different clans lived in the villages, which must be viewed as a random group of clan fragments or lineages .

Anthropologist John R. Swanton pointed out that bands were not formed until late in Potawatomi history. The reason was contracts with the Americans to divide the tribe into larger groups. These bands consisted first of reservation groups like the Citizens' Band , second of contract groups like the United Bands of Ottawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi , and third of dispersed refugee groups like the Forest Band .

Villages and chiefs

The Potawatomi lived in small villages around 1818 that were spread over a large area. Each village was headed by a chief who considered himself independent. The social relationships between the widely scattered villages were different and varied. Kinship was an important factor and led to a certain solidarity, especially at the regional level. The expansion of the tribal area was often due to the fact that clans or parts of clans were pressured to found a new village. They moved to another location, but kept in touch with their original clan or village. A local chief could rule several villages for a long time if he was sufficiently influential, wealthy and successful. One such man was Chief Blackbird in Milwaukee, who managed to prevent an alliance between the Potawatomi and the British in the American War of Independence .

The leader or wkema of a village was respected but had little power. He was usually an older man of decent character who was a member of the clan with chieftainship. The candidate was chosen from several suitable applicants by the village, but did not get the office through inheritance. A chief's power depended on his personal standing, not on formal authority. Much of the reputation came from the level of supernatural powers attributed to him as a result of his successes.

The leader of a village was assisted by a council of warriors , which represented both public opinion and personal interests. In addition, there was a special sodality (wkectak), which consisted of merited warriors. She had her own songs and dances and performed police functions. It was an inter-tribal brotherhood with members in numerous villages, which promoted cohesion within the tribe. At the side of the leader of the brotherhood stood a so-called pipe lighter and a crier or herald . He proclaimed messages, organized ceremonies, called council meetings and helped the chief with routine tasks. In the 1820s, the Council of Warriors carefully monitored and controlled the work of the Wkema , for they were suspicious for good reason. According to Tecumseh , some chiefs would sell Indian land for their own account and would be given greater powers by the British and Americans.

Clans and rituals

By 1800 most of the Potawatomi clans were hopelessly fragmented. Its members and lineages were to be found in numerous, sometimes widely spaced villages. Some younger clans, however, weren't spread out over such a large area. In 1823, William Keating reported that the Potawatomi clans were not linked to any animal ancestor. Rather, he found that they "had some sort of distinguishing feature for families whose symbols resembled our heraldry ". They called these symbols n-totem ("my clan totem"). According to Keating, the totem groups did not believe in a common animal ancestor. They were patrilineal after the fathers line and exogamous (outside marriage) organized and divided into six groups or phratries divided (clan associations): Water (Water) , Bird (Bird) , Buffalo (Buffalo) , Wolf (Wolf) , Bear (Bear) and Man (man) . Of the 23 clans Alanson Skinner identified in 1923, 13 years later there were only 11 with living members. For this there was a new clan called Engel (Angel) . As a result, old clans died out and new ones were introduced. 10 Potawatomi clans were discovered in Wisconsin and Kansas-Oklahoma. It was noticeable that the most southern clans were associated with large animals, namely with buffalo (Buffalo) , grizzly bear (Grizzly bear) and elk (Moose) . The northern clans, on the other hand, were named after small fur animals such as otters (otters) , muskrats (muskrat) and marten ( marten ) .

When numerous clans broke up and their members and lineages were spread over different villages and regions, the clan system nevertheless promoted the cohesion of the entire tribe. The clans served as an important factor of order, assigning each member their special place in the village and tribe. As a child, each Potawatomi was given one of their traditional names and personal levels of spiritual power from their clan. The individual was thus integrated into a system of social relationships with other clan members. The most important functions of a clan consisted of the preparation and implementation of rituals, festivities and dances, with one phratry being responsible for the host, the second for providing food and drink and the third for the ceremonies themselves. A child's name came from a pool of names derived from the clan's nickname. For example, was a woman from the Thunder Clan (Thunder clan) named "Coming noise" (Coming Noise) , or a man of the Wolf Clan, the term "Growler" (Growler) . As a rule, the Potawatomi had several other names, such as warrior names and nicknames, which were often used as first names.

Each clan had a "sacred bundle", the associated myths and a series of songs, chants and dances. The Potawatomi believed they got the clans along with the sacred bundle of Wiske , the cultural hero . The bundle itself consisted of a leather pouch adorned with colored ribbons and pearls. It contained powerful keepsakes, talismans and fetishes that the clan of Kcemneto ("Great Spirit") had received.

The Potawatomi shared the custom of dual subdivision with the Central Algonquin . This divided the entire population, women and men, young and old, in two halves according to the order in which they were born. The first, third, and fifth children were on the senior side , and the second, fourth, and sixth children were on the junior side . This dichotomy was important, for example, in the formation of teams for games, as well as in some rituals. This dual system divided the family, the lineage , the clan and the village and served as a means of organization and as an opportunity to resolve emerging rivalries.

The Potawatomi had a number of brotherhoods and religious experts who determined village life and maintained connections with other villages. The Midewiwin , a medical society, represented an inter-tribal association of very influential magicians who could use their power for good or bad. The sawnoke was a spring ritual performed on behalf of someone who lost a relative the previous winter. The caskyet was a fortune teller who, as a ventriloquist and juggler , entertained his audience before predicting the future or determining the place where lost things were to be found. There was also a healer who used his skills to treat illnesses. The French and English called all these people "jugglers" (jugglers) and regarded them with suspicion and skepticism.

Houses

The Potawatomi moved twice a year, in spring to a large summer village and in autumn to several small winter villages. The summer villages varied considerably in size, from less than 50 to more than 1,500 residents. Around 1800 there were at least nine Potawatomi villages with a total population of around 4,000 people in the area of what is now Milwaukee. There were different types of buildings in the summer villages: Rectangular bark-covered houses with a pointed roof; huts open on the sides and used as cooking areas; and a little out of the way, the mat-covered menstrual huts for women. The dome-shaped winter houses covered with bark or matting were smaller.

One house was initially inhabited by a nuclear family, which later expanded over several generations. The family was also able to grow through sororal polygyny . It was the preferred form of marriage union, comprising around twenty-five percent of all marriages. Young husbands lived with the woman's family for about a year, providing them with hunting booty and looking after the horses. Then they returned to the husband's village.

Way of life

The life of the Potawatomi was closely linked to the change in nature. They also knew four seasons and at least twelve months, which were named after the most important resources and activities in the corresponding time. For example, January was called Big Bear Month , when a hunter and his dog could easily kill a bear while it was hibernating. February had at least four names, such as sugar month, wolf month, snow month and baby birth month . Further months were called the trap month , hunting month and planting month . In the north of the tribal area, the year began in mid-April when the maple trees were tapped to make sugar. Now began a time of abundance after a cold, hard winter.

The Potawatomi used traps, weirs, nets, fishhooks and harpoons for fishing. They had long cylindrical fish traps connected to dams for catching fish with traps or harpoons. They gathered wild herbs and fruits, such as cherries, raspberries, blackberries, plums, grapes and roots of various kinds. The animals that could be hunted included bears, deer, elk, buffalo, squirrels, muskrats, raccoons, porcupines, wolves, turkeys, geese and ducks . The dog was the only pet that was eaten mainly for religious reasons.

The collected or harvested food was preserved and stored for the winter. Many supplies were dried and stored in bark containers or vessels. Squash was cut into rings and smoked or dried in the sun. Corn was boiled and then scraped off the cob, dried and placed in containers. The women immediately cut the meat that was not eaten into strips, dried it and smoked it. Ducks, geese, and turkeys were pickled, then smoked and stored while fish were dried and smoked. Maple sugar was used more often than salt to refine dishes.

transport

Considerable logistical planning was required for the seasonal relocation of a village. By 1800 the Potawatomi traveled either along the waterways or over land. On the water, they used both the standard dugout canoe and a larger canoe, which consisted of a boat-shaped frame covered with pieces of bark from birch, white elm or linden. This canoe was 25 feet (7.60 m) long and 5 feet (1.52 m) wide. Such a canoe could not be made by everyone, only by certain members of the Man clan . The Potawatomi apparently had little interest in long journeys on the water or risky and arduous canoe trips. Before 1800, canoes were often transported by horses, especially in the south of the Potawatomi Territory, and then used for shorter distances on the water, such as for hunting and fishing. By 1800 the Potawatomi in the Milwaukee area had herds of ponies so large that white farmers fenced their corn fields. The horses were given a saddle, which consisted of a wooden frame covered with rawhide, and was suitable for riding or for carrying loads. Large saddlebags made from woven rush mats were used to carry goods and wild rice, which was collected in large quantities. In addition, the Potawatomi used a kind of carrying device, which was attached between two horses, and on which sick, infirm or heavy goods could be transported.

Life cycle

The pregnant woman has been the focus of numerous restrictions in order to protect the unborn child from bad influences and to make the birth easier. These restrictions included strict taboos and bans on certain foods. The birth took place in a special bark-covered hut, with the mother on her knees and supported by experienced women. The mother and baby were isolated for a month, after which they were allowed to return to their family, where a party was held for the child. After about a year the child got a name from the clan's fund. It became a member of the clan and got a certain status. After several years, the child was weaned from breast milk, but no later than when the mother became pregnant again. From the first steps to puberty , the child was called Wsk eniksi (boy) or Kiyalo (girl). During this time, children were expected to develop certain skills depending on their gender. Perseverance, discipline and toughness in the face of hunger and deprivation were all required. Boys and girls acted out the work of adults. Boys made small bows and arrows, built small bark canoes, and played lacrosse . Girls played with homemade dolls and practiced household chores.

Adulthood began with puberty. The girl spent her menstrual period alone in the menstrual hut outside the village. When the villagers moved, the girl had to stay parallel to the main train at some distance. The boy in puberty sought solitude to fast and expects a powerful vision. Girls generally married a little earlier than boys. Marriage marked the entry into adulthood, and boy and girl were then called man and woman.

The ancient people of the Potawatomi were considered wise, experienced, and powerful and were treated with great respect. Her responsible tasks in the village included the moral upbringing of the children and participation in council meetings. Her work was highly valued until death took her on the journey west, where the twin brother (Cipyapos) of the cultural hero (Wiske) and the guardian of the afterlife awaited him. The death was accompanied by special burial rituals of the clan members. The best clothes were put on the corpse and he was given various grave goods: moccasins , rifles, knives, money, silver jewelry, provisions and tobacco. The type of burial followed the deceased's express wish. The body was buried upright, seated, or tilted, or placed in the fork of a tree. Finally, the grave was marked with a post and painted or incised pictograms that identified his clan and listed the deceased's most important merits. Shortly afterwards, the main mourner looked for a replacement for the deceased. For example, a daughter would adopt a new mother and a grandson would adopt a new grandfather.

history

Early history

The accounts of the Potawatomi, Odawa and Ojibwe consistently show that all three tribes moved from the northeast to the east coast of Lake Huron around 1400. The Ottawa initially stayed on the French River and on Manitoulin and other islands in Lake Huron, while the Potawatomi moved north along the coastline to Sault St. Marie. Here they swiveled south and crossed Mackinac Strait around 1500 to settle in lower Michigan. Although now separated, the three tribes called themselves the three brothers because of their previous alliance, and the Potawatomi were called the keepers of the council fire. The Potawatomi are first mentioned in French lore from the early 17th century as residents of what is now southwestern Michigan. When the French built Fort Ponchartrain near today's Detroit in 1701 , the Potawatomi mainly settled in the area between today's cities of Milwaukee and Detroit. During the Beaver Wars , they fled attacks by the Iroquois and neutrals on Green Bay and the Door Peninsula on the west bank of Lake Michigan in what is now Wisconsin .

Refuge on the Door Peninsula

When the Potawatomi appeared in French reports around 1640, they were first perceived as a single tribe and given a distinctive name. Their neighbors were local groups (local bands) , which were among the Chippewa or Odawa. In the earliest historical records of Potawatomi clans, they are clearly identified as groups belonging to a single tribe. Nicolas Perrot, for example, described the conflict between two French traders and the leader of the Red Carp clan , who quickly spread to other leaders of other clans. This information indicates that the Potawatomi developed more unity and identity than the similar Chippewa and Odawa.

In 1642 the Jesuit Gabriel Lalemant provided a second hand account of the distant "nation" of the Potawatomi, who sought refuge in Sault Sainte Marie from "some other hostile nations who pursued them with endless wars". Further evidence of their stay there comes from archaeological finds on Rock Island, which could be dated to 1650. Ménard wrote in 1659 that some Potawatomi had visited him in June in his station on Keweenaw Bay . They reported 40 other tribesmen who had died of diarrhea eleven days away last winter. By 1652 the majority of the tribe was believed to be in a fortified village that the Potawatomi called Méchingan and for which the Jesuits were planning the new Saint Michel mission . The exact location of this village has not yet been found. It could have been at the tip of Green Bay or on the opposite side of the Door Peninsula on the shores of Lake Michigan. The danger of raids by the Iroquois caused the Potawatomi to assemble in such large numbers in Méchingan and to ally themselves with remnants of the Petun and Winnebago , as well as with parts of the Chippewa from the north. Originally refugees, they now formed a powerful but defensive coalition against the Iroquois League. Perrot wrote that the Potawatomi felt superior to other tribes and considered themselves to be arbitrators for all the tribes at Green Bay. Neither external threats nor successful military campaigns were sufficient to bring together the highly individualistic and independent peoples, clans or families into a functioning local unit. Cross-tribal sodalities and symbols were required. The Midewiwin were a religious brotherhood that developed among the Algonquians on the Great Lakes and can be seen as a reaction to the changed living conditions during this period. The Mediwiwin were first mentioned in connection with the Potawatomi in the Detroit area in 1714. At that time the brotherhood was already an established institution.

There were so strong countercurrents among the Potawatomi around 1670 that the earlier village communities broke up. This was primarily due to population growth and positive economic prospects as the Iroquois threat subsided. The result was a migration of the Potawatomi clans to new territories. Perrot lived with the Potawatomi around 1670 and was familiar with the wishes and ideas of the tribesmen. He gave a careful report of the situation at the time. In one passage that is often incompletely quoted, he describes the efforts of the Potawatomi to gain respect, loyalty and appreciation from neighboring tribes and to establish trade relationships. “They give away a large part of their possessions and separate themselves from important things, animated by the fierce desire to be viewed as generous.” Regarding the consequences, Perrot remarks: “Their ambition to please everyone led to jealousy and Divorces, so that the families on the right and left of Lake Michigan split up. "

In the same year the Potawatomi had successfully entered into the Odawa trade on Green Bay. Most of the French goods that the Odawa obtained from Montreal were taken over by the Potawatomi. But they wanted to be dealers and not producers of fur and were now in the classic position of intermediaries at the lower end of the exchange network. In order to ensure a constant supply of furs from other tribes, the Potawatomi leaders had to severely limit their own needs and those of their close family members, their clan and those of the other villagers. The Potawatomi leaders thereby neglected their most important duty within the clan and the village, namely generosity towards their relatives. The result was divorces and the emigration of numerous small, economically independent groups.

Allies of the French

Relations with other tribes were largely dependent on their behavior towards the French, English and later the Americans. Around 1648 there was a conflict with the Odawa , who viewed themselves as mediators in trade between the French and the tribes on Green Bay. The dispute was successfully resolved in 1655 by Médard Chouart des Groseilliers . By 1653, the Potawatomi were probably the most populous tribe on Green Bay. In the same year, the Journal of the Jesuit Fathers reported : "To counter the threat from the Iroquois, 400 Potawatomi, 200 Odawa, 100 Winnebago, 200 Ojibwe and 100 Mississauga warriors gather in the area of Green Bay ." A few years later, the Potawatomi took control of the trade with the tribes in the south and west, although they could only muster half the warriors valued by the French.

In the summer of 1668, members of the Mascouten , Miami , Kickapoo and some Illinois came to Green Bay to escape the Iroquois raids and at the same time to make contact with the tribes who already had trade relations with the French. The visitors came on foot, not by canoe like the Potawatomi, and wanted to ask the French under Nicolas Perrot for an invitation. The Potawatomi wanted to prevent direct contact between the tribes and Perrot in order to act as mediators themselves. They had previously visited the French in Montreal, were proud of their new trading partner, their future prosperity and believed in a certain supremacy. Perrot made it clear to the Potawatomi that he wanted to negotiate personally with the individual tribes and enforced French interests. This began a mutually lucrative commercial relationship that would last for almost 100 years until the end of the French era in North America in 1763.

The French policy of those years was to break the monopoly of the tribes who acted as intermediaries in order to optimize their own profits. The attempt of the Potawatomi to emulate the role of the Hurons and Odawa in trade was doomed to failure. They quickly changed their stance and "declared themselves arbitrators for all the tribes on Green Bay and their neighbors. And they were anxious to maintain that reputation in every way. ”At Perrot's request, the Potawatomi manned thirty canoes for the next fur shipment to Montreal and then extended their collaboration with the French.

At this point the expansion of their tribal area through the exercise of prudent politics began. They always made alliances with strong tribes and occupied the territories of weaker peoples. In the early 1670s, the Potawatomi formed an alliance with the Sauk , Fox and Odawa and waged war against the Sioux , which cost them fewer victims than their allies, "because they showed their heels at the beginning of the battle". They accompanied Perrot on the visit of Miami 1671 in Chicago. In the same year, they convinced the Great Chief of Miami that the long trip to Sault Sainte Marie to attend the celebrations of the French occupation of the West could harm his health. The chief allowed the Potawatomi to officially represent Miami at the celebration. No one, however, was able to oversee all trade and restrict it to the French posts, as the French and Potawatomi had agreed. In 1674, for example, they had exchanged French goods for beaver skins from the Kaskaskia in Illinois without a French knowing about it.

Potawatomi warriors also took part in the French campaigns against the Iroquois in 1684, 1688 and 1696. In 1695, 200 Potawatomi warriors moved with their families to the Miami Territory north of the Saint Joseph River in Michigan and displaced the Miami living there. It was partly an area they had left almost 53 years ago. In 1712 an alliance of Potawatomi and Odawa attacked several groups of the Fox and Mascouten near Detroit and drove them out. Two years later they settled the area.

Around 1720, Potawatomi hunting groups were found hunting buffalo on the Mississippi. Other Potawatomi and Odawa raided groups of Chickasaw together in western Tennessee and the Mississippi in 1740–1741 . Together with the French, Potawatomi warriors raided British colonies in Connecticut and New York . In the second half of the eighteenth century, they defeated the Illinois tribes and took over their territory on the prairie. In 1763 they were allied with Pontiac , captured the British positions in Saint Joseph and supported Pontiac in the siege of Detroit. By 1769 they had extensive trade relations with the Spanish in St. Louis .

The policy of expansion of the Potawatomi at the expense of the weaker tribes lasted almost until the middle of the nineteenth century. For example, in the Treaties of Chicago 1833 to 1834, most of the Indian villages in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois were combined and named United Bands of Odawa, Chippewa and Potawatomi . However, the affected villages were mainly inhabited by members of the Potawatomi and only a minority consisted of Odawa and Chippewa. Once the United Bands (later Council Bluffs Bands ) moved west to the Iowa prairies , they took on buffalo hunting and horseback warfare. Around 1840 they enlisted allies in the fight against the Yankton Dakota in order to gain access to more productive hunting grounds for buffalo hunting.

Division and move to reservations

Soon after the end of the war of 1812 , in which the majority of the Potawatomi were on the British side, the chiefs made it clear that they would recognize the power of the Americans. The living conditions of the Potawatomi changed noticeably when their land in the old Ohio area was inundated by American settlers. Still, there were numerous tribesmen who remained loyal to the English until 1839 and who went to the British posts in Amherstburg , Sarnia , Drummond Island and Manitoulin Island to collect their annual gifts and rations. The Potawatomi in southern Michigan and northern Indiana were initially shocked by the massive American colonization of their residential area. In the meantime there were numerous mixed marriages with French and English people and they were to a considerable extent dependent on European goods, although there was hardly any fur in return and the war services of the Indians were no longer needed. The Potawatomi in Michigan and Indiana were the target of intensive proselytizing and educational programs. They showed a great reluctance to migrate to areas west of the Mississippi. Until 1841 they resisted relocation and tried to live on annual pension payments. Eventually they were forced by the US government to move to a reservation on the Osage River in Kansas , where they were called the Mission Band . The situation of the Potawatomi in Illinois and southern Wisconsin was different after 1833. Most of the villagers still had access to fur animals, even if it was muskrats and raccoons instead of beavers. Together with the Sauk and Fox, they now hunted on the prairies west of the Mississippi. This area has not been so much shaped by American settlers. They had signed contracts with the option to return. Under the leadership of their chiefs, they decided to move west, although not all took part. In lower Michigan there was now a large group of acculturated Potawatomi who lived on the outskirts of American cities. In Wisconsin, on the other hand, most of the Potawatomi tried to make a living through a mixture of the traditional way of life and American farming methods.

The Illinois-Wisconsin Potawatomi were relocated to a reservation at Council Bluffs in western Iowa and renamed the Council Bluff Band . Within 15 years they had adopted the Plains Indian culture and become skilled hunters and warriors on horseback. They had to move again around 1847. Together with the Potawatomi from the Osage River, a new reservation was established for them on the Kaw River in eastern Kansas and was considered a project that was overseen by Reverend Isaac McCoy. He intended to form a civilized Christian Potawatomi nation . It was a project that was doomed to fail for several reasons, as the two groups living on the reservation were too different. One was conservative, did not accept any innovations and wanted to regulate internal affairs itself, while the second group became increasingly acculturated.

The conservative group was now called the Prairie Band and consistently kept its stake in the Kaw River Reservation until the Dawes Allotment Act of 1890 forced them to agree to the area being subdivided into individual lots. The Mission Band had their reservation parceled out earlier and was impoverished within a few years. In 1867 the relatives signed the last Potawatomi contract, in which they agreed to move to a new reservation in Oklahoma and were now called Citizen Band . For the prairie band, the Dawson Act had the effect that in 1960 only 22 percent of the Kansas reservation was owned by the members. By 1970 there were around 20 groups in the United States and Canada that identified themselves as Potawatomi, or were known to have descended from a nineteenth-century Potawatomi band. These include four independent reservations in the United States, namely the Citizens Band Reservation in Oklahoma, the Prairie Band Reservation in Kansas, the Hannahville Community on the Upper Michigan Peninsula, and the Forest County Potawatomi Community in northern Wisconsin.

Potawatomi in Canada

Between 1837 and 1840, about 2,000 Potawatomi moved from Wisconsin, Michigan and Indiana to the southwest of the Canadian province of Ontario . They chose the route via Detroit and Port Huron to Sarnia and Walpole Island . It was the same groups that had previously picked up gifts and payments from Canada either for military service they did in the War of 1812 or for their loyalty on a regular basis. By 1970 there were twelve different places where descendants of the Potawatomi lived. The largest were Walpole Island, Sarnia, Kettle Point, Orillia, Cape Croker, Saugeen, and Manitoulin Island. The situation of the Canadian Potawatomi differed from that of their American relatives so much that they assimilated mostly with Indians from other communities, preferably with Chippewa and Odawa. When they reached Canada, they had no contractual rights, including no land ownership and no pension entitlement to land sales. Gradually they were accepted into the reserves of other tribes, accepted after a few problematic years and finally formally recognized as reserve members.

Chiefs

Potawatomi groups that exist today

The following recognized groups of the Potawatomi currently live in the USA and Canada:

United States

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation (CPN) , (descendants of the Potawatomi of the Woods (southern Michigan and northern Indiana), the Mission Band from St. Joseph (southern Michigan) and Mission Band of Potawatomi Indians ( Wabash River Valley in Indiana), The administrative seat is Shawnee , Oklahoma , the reservation is in Cleveland and Pottawatomie Counties, population 2011: 29,155)

- Forest County Potawatomi Community (FCP) (the Forest County Potawatomi Indian Reservation , consisting of several non-contiguous pieces of land in southern Forest County and northern Oconto County , Wisconsin as well as a small piece of land (approx. 28,000 m²) in the urban area of Milwaukee , comprises approx. 50 , 5795 km, population 2000: 531)

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (formerly: Northern Michigan Ottawa Association, Unit 2 , consists of descendants of the former Indian alliance Council of Three Fires - the Odawa (Odaawaa / Ottawa), Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa) and Potawatomi (Boodewaadami / Bodéwadmi / Bodowadomi), the reservation as well as additional land parcels that were handed over to the tribe for administration cover approx. 4.5 km² in Michigan, population: 3,985 tribal members, of which approx. 1,610 live on tribal land)

- Hannahville Indian Community (the reservation (22.21 km²) is located on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan , approximately 15 miles west of Escanaba , in eastern Menominee County and southwestern Delta County , Michigan , population 2013: 891)

- Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi (formerly known as Gun Lake Tribe or Gun Lake band , was namesake of the Potawatomi chief Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish , 1795 the Treaty of Greenville with signed by the English, the administrative seat is Dorr in Allegan County , Michigan - the tribe is made up of descendants of the former alliance "Council of Three Fires" - the Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa), the Odawa (Odaawaa / Ottawa) and the Potawatomi ( Boodewaadami / Bodéwadmi / Bodowadomi), who today identify themselves linguistically and culturally as Pottawatomi)

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (NHBP) (only federally recognized tribe) as a tribe on December 19, 1995, the reservation (524,000 m²) is located in Athens Township in southwestern Calhoun County in southern Michigan, despite their tribal designation they are both linguistically and culturally not related to the Iroquois-speaking Hurons - however, both names Nottawaseppi and Huron refer to the original tribal area along the Clinton River (named after DeWitt Clinton, the Governor of New York from 1817 to 1823) in southeast Michigan up to whose confluence with Lake St. Clair on the Canadian border, since the river wasonce referred to bythe tribal alliance in Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin) as Lake Nottawasippee - "River of the rattlesnakes -like, ie the Hurons", the French allied this indigenous name, later the British named the river Huron River of (Lake) St. Clair - however, it was in 1824 in Cl renamed inton River to avoid confusion with the neighboring Huron River , population: approx. 800)

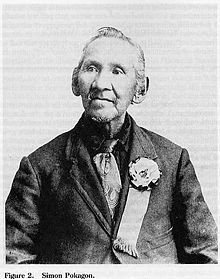

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi (the Pokégnek Bodéwadmik or Pokagon Band of Potawatomi are descendants of the allied Potawatomi settlements along the Saint Joseph River , Paw Paw River and Kalamazoo Rivers in southwest Michigan and northern Indiana, eponymous is Leopold Pokagon (approx. 1775 - 1841), a Potawatomi leader ( Wkema ), since 1826 chief of the Potawatomi in the Saint Joseph River Valley, administrative seat is Dowagiac, Michigan, the reservation is in the six counties of LaPorte, St. Joseph, Elkhart, Starke, Marshall and Kosciusko in northern Indiana and four counties from Berrien, Cass, Van Buren and Allegan in southwest Michigan, population (2014): 4,990)

- Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (formerly Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians , own name: Mshkodésik - "People of the Small Prairie", this band originally lived along the southern shore of Lake Michigan in what is now southern Wisconsin, northern Illinois and northwestern Indiana, later they were forciblyrelocatedalong with other groups of the Potawatomi in the 1830s during the Indian Removal Act west of the Mississippi , first in 1835-36 to the Platte River in Missouri, in 1837 the groups that had been drawn together split up due to contentious issues Referring to the acceptance of European culture and religion in two bands - the Conservative settled in the Council Bluffs , Iowa area and became known as the Bluff Indians or the Bluff Indian Band - this is where they adopted the Plains Indian way of lifewith bison hunting and evolved to warlike equestrian nomads , the already strongly acculturated and progressive mission band them Delte in Linn County, Kansas and tried tokeepparts of their culture as the Northeastern Woodland Indians of the Great Lakes, in both places they controlled an area of approximately 20,000 km², between 1837 and 1846 the bands continued to settle in two different areas - the mission Band along the Kansas River , the Prairie Band (formerly: Bluff Indian Band) roamed the area along Big and Little Soldier Creeks in Jackson County, Kansas , the attempt in July 1846 to reunite the two bands by means of a contract was unsuccessful, 1861 a new contract was concluded because the internal differences wg. Religion and culture could not be resolved, the Mission Band of Linn County became US citizens and now known as the Citizen Band , while the Prairie Band wanted to continue to follow their traditions, in 1867 the contract was revised again and two new tribes were established: the Citizen Band of Potawatomi sold all of the land claims in Kansas and settled on their present reservation in the Shawnee, Oklahoma area - however, the Prairie Band of Potawatomi triedto keepas much of their Kansas reservation, which once included parts of what is now the capital, Topeka , but was 1960 only 22 percent of the Kansas reservation is owned by the members, today's administrative headquarters is near Mayetta , Jackson County, Kansas)

Canada

Southern First Nations Secretariat

- Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation (the First Nation consists largely of descendants of the Potawatomi and Anishinabe (Ojibe / Chippewa) as well as some Odawa (Ottawa), administrative seat in the Kettle Point Reserve # 44, 35 km northeast of Sarnia on the southeastern shore of the lake Huron , approx. 10 km² in Lambton County , Ontario, population: 2,364)

- Chippewas of the Thames First Nation (refer to themselves as Anishinabek , the reservation of the First Nation, which consists of Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa) and Bodaywadami (Potawatomi), lies on the north bank of the Thames River , which is from the Odawa As Askunessippi - "the antlered river" (by the Anishinabe Eshkani-ziibi ) was called, approx. 20 km southwest of London , Ontario, its current territory covers most of the southwest of Ontario, administrative seat: Muncey, Ontario, population: 2,694)

- Walpole Island First Nation (also Bkejwanong First Nation , which consists of members of the Potawatomi, Anishinabe (Ojibe / Chippewa) and Odawa (Ottawa), called the area Bkejwanong - 'where the waters divide', the administrative center is on the island of Walpole Island # 46 at the confluence of the St. Clair River in Lake St. Clair , approx. 50 km northeast of Detroit , Michigan and Windsor , Ontario, additional reservation land includes the islands of Squirrel, St. Anne, Seaway, Bassett and Potawatomi, reservation: Walpole Iceland # 46 (between the USA and Canada), approx. 160 km², population: 4,527)

Ogemawahj Tribal Council (OTC)

- Beausoleil First Nation (mostly an Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa) First Nation, which, according to its own information, also consists of descendants of the Potawatomi; however, there are # 30 tribesmenin the main Christian Island reserve, who claim to bedescendedfrom Odawa, the reservation areas of the First Nation are located at the southern end of Georgian Bay on Christian Island, Beckwith Island and Hope Island in what is now Simcoe County , Ontario , reservations: Christian Island # 30 (southeast of Georgian Bay), Christian Island # 30A (16 km west of Midland ), Chippewa Island ( 30 km south of Parry Sound Island), population: 2,199)

- Moose Deer Point First Nation (Moose Point # 79 reservation is located approximately 51 km west of Bracebridge on the east bank of Georgian Bay , Ontario, the First Nation is within the Township of Georgian Bay , with three separate parcels of land: King Bay and Isaac Bay (as residential areas) and Gordon Bay (as a commercial, leisure and administrative center), administrative headquarters: MacTier, Ontario, approx. 2.50 km², population: 460)

Wabun Tribal Council

- Saugeen First Nation (official name: Chippewas of Saugeen , although mostly Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa) there are also many descendants of Odawa and Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi) whofled northwards from the USAdue to the war of 1812 and settled on the east bank of the Bruce Peninsula (also Saugeen Peninsula ) settled in Ontario, together with the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation , they are referred to as Saugeen Ojibway Nation Territories or as Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory , as the Nawash and Saugeen First Nations share tribal areas in southwestern Ontario , The reserves are along the Saugeen River (from Zaagiing - "at the outlet of the river, ie at the mouth of the river") and on Lake Huron and in the south of the Bruce Peninsula in Ontario, about 3.2 km northeast of the administrative center Southampton and about 18 miles from Owen Sound , Ontario, reserves: Chief's Point # 28, Saugeen # 29, Saugeen Hunting Grounds # 60A, Saugeen & Cape Croker Fishing Island # 1)

Independent First Nations

- Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation (formerly: Cape Croker First Nation , eponymous is Chief Nawash, whofoughttogether with Tecumseh in the war of 1812, after the defeat many Odawa and Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi) fled the USA northwards to the Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa) on the east bank of the Bruce Peninsula, so that today's First Nation mostly consists of Anishinabe as well as descendants of Odawa and Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi), the administrative seat is in the most populous reserve Neyaashiinigmiing # 27 on the east bank of the Bruce Peninsula (also Saugeen Peninsula ) southwest of Georgian Bay , Ontario , about 26 km away from Wiarton, 40 miles from Owen Sound or 250 km from Toronto, together with the Saugeen First Nation they are referred to as the Saugeen Ojibway Nation Territories or Chippewas of Saugeen Ojibway Territory , since the Nawash and Saugeen First Nations share tribal areas in southwestern Ontario, reservations: Cape Croker Hunting Ground # 60B, Neyaa shiinigmiing # 27, Saugeen & Cape Croker Fishing Island # 1, approx. 63.80 km², population: 2,075)

- Wasauksing First Nation ( Wasauksing - 'shining shore', formerly Parry Island First Nation , is an Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa) and Potawatomi First Nation on Parry Island in Georgian Bay, with approx. 77 km² and a 126 km long shoreline of one of the largest islands in the Great Lakes, administrative headquarters is in the Parry Island First Nation reservation, 64 km west of Huntsville on the east bank of Georgian Bay, population: 1,073)

- Wikwemikong First Nation ("Bay of Beavers", also: Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve , the First Nation - consisting of descendants of the Odawa, Potawatomi and Anishinabe (Ojibwe / Chippewa), is the most populous First Nation on Manitoulin Island, the main reserve is Wikwemikong Unceded IR lies on a peninsula at the eastern end of the island of Manitoulin and on the coast of Georgian Bay, the smaller reserve Point Grondine is on the opposite bank of Georgian Bay near Killarney in the Sudbury District on the mainland of Ontario, the Odawa have been alive since the mid-1600s the island, three Potawatomi families settled since 1832 and from 1850 fleeing Anishinabe joined them, in the following years the tribes on Manitoulin Island had to cede most of the land to Canada in several treaties and were settled in reservations - today's Saugeen, Sheguiandah, Sheshegwaning, Zhiibaahaasing and Aundeck-Omni-Kaning First Nations ; - 1968 wu rde recognized the First Nation and today's reservation, it consists of three previously independent bands - Manitoulin Island Indian Reserve, Point Grondine, South Bay - which had never ceded land (hence: Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve ), administrative headquarters: Wikwemikong, Ontario, reservations : Wikwemikong Unceded IR, Point Grondine, 412.97 km², population (2009): 7,278, of which approx. 3,030 live in the reserve)

Demographics

Estimating the total population of the Potawatomi is difficult because of the lack of comparable data. Numbers from the entire eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are incomplete. These usually consist of the number of warriors under arms that could be used for or against the British and French. In addition, numerous villages in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois were often missing from the calculation. The standard estimate from prehistoric times around 1600 was 4,000 and could come from the first French census. The next estimates came from French missionaries and government agents between 1653 and 1695. These gave 700 warriors and a total population of 3,000. After 1778 the British spoke of 2,250 tribesmen, but this estimate is considered to be as incomplete as an American estimate from the 1830s that gave 6,500 people. In the 1850s, more than 600 "wandering Potawatomi" were known in Wisconsin, but no one had counted the tribesmen who had previously fled to Canada. There were also numerous Potawatomi who joined other tribes, such as about five hundred the Kickapoo under Kenekuk, several hundred the Menominee and some the Kickapoo in Mexico.

The official US census of 1836 found a total of 6,694 Potawatomi living in the United States. It should be noted, however, that a large number of tribesmen in the Wisconsin forests or en route to Canada were not included in the census during this period. Together with these people, a total of nine to ten thousand Potawatomi is likely in the first half of the nineteenth century. The 2000 US census found a total of 15,817 Potawatomi. Around 6,000 tribesmen lived in Canada at the time.

| year | total | United States | Canada |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1667 | 4,000 | ||

| 1765 | 1,500 | ||

| 1766 | 1,750 | ||

| 1778 | 2,250 | ||

| 1783 | 2,000 | ||

| 1795 | 1,200 | ||

| 1812 | 2,500 | ||

| 1820 | 3,400 | ||

| 1843 | 1,800 | ||

| 1854 | 4,440 | 4.040 | 400 |

| 1889 | 1,582 | 1,416 | 166 |

| 1908 | 2,742 | 2,522 | 220 |

| 1910 | 2,620 | 2,440 | 180 |

| 1990 | 23,000 | 17,000 | 6,000 |

| 1997 | 25,000 | ||

| 1998 | 28,000 |

See also

literature

- Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Northeast (= Handbook of North American Indians . Volume 15). Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1978, ISBN 0-16-004575-4 .

Web links

- Hannahville Indian Community; Wilson, MI

- Citizen Potawatomi Nation

- First Nations Compact Histories: Potawatomi History

- Forest County Potawatomi

- Kettle & Stony Point First Nation

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

- Potawatomi author Larry Mitchell's blog

- Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation

- Treaties with the Potawatomi

- "Treaty Between the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi Indians"

Individual evidence

- ^ Anishinaabe Nations - Anishinaabe Nations by State or Province / Anishinaabe Akiing ( Memento of May 10, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Anishinaabeg or Anishinabek

- ↑ History of the Potawatomis (Neshnaabe / Neshnabek)

- ↑ Neshnabek: The People

- ↑ Neshnabék Links ( Memento of the original from February 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The Odawa - Council of Three Fires ( Memento from June 30, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Omniglot - Potawatomi (Bode'wadmi)

- ↑ ( page no longer available , search in web archives: Bode'wadmi Zheshmowen (Potawatomi language) )

- ↑ Some hints for Potawatomi students… (No longer available online.) In: APWAD - A Potawatomi Word a Day. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010 ; Retrieved July 5, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 725/726

- ↑ Project Ojibwa - Council of the Three Fires ( Memento of the original from October 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Project Ojibwa - Who are the Ojibwa? ( Memento of the original from October 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Virtual Museum of New France - French Colonial Expansion and Franco-Amerindian Alliances

- ↑ The Seven Nations of Canada - The Other Iroquois Confederacy ( Memento of the original from December 13, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ 1812 First Native Nations (Anishinaabeg, Algonquin, Haudenosaunee, Wendat) ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Often erroneously referred to as the Miami Confederacy by the Americans, as they overestimated the military and numerical power of the Miami within the Western Confederacy

- ↑ American Indian Heritage Month: Commemoration vs. Exploitation ( Memento from September 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The History of the Wea ( Memento of the original from October 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Potawatomi History ( Memento of the original from April 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ About MNCFN. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on July 14, 2011 ; Retrieved July 5, 2016 (in the mid-19th century, the Mississaugas believed they were named after the mouths of the Trent , Moira , Shannon , Napanee , Kingston and Gananoque rivers ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 728-730.

- ↑ a b c d e f Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 731-733.

- ↑ Potawatomi Culture ( Memento of the original from October 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Volume 15: Northeast , pp. 734-736.

- ↑ a b c d e Potawatomi History , accessed February 26, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 727/728

- ↑ a b c d Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 736-740.

- ^ Homepage of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Forest County Potawatomi Community

- ^ Homepage of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- ↑ homepage of Hannah Ville Indian Community

- ↑ Homepage of the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi ( Memento of the original from December 6, 2001 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ However, Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish is listed as a Chippewa chief named Bad Bird by the English, as the whites often could not distinguish the close allies Potawatomi, Chippewa and Ottawa from one another

- ^ Homepage of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi

- ↑ Homepage of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi

- ↑ Homepage of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation ( memento of the original from March 7, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ the Mshkodésik - "People of the Small Prairie" of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation must not also with the Algonquian-speaking mascouten be confused with a name from the language of the Fox was derived and "small prairie people" means; In addition, the Wyandot (Hurons) called this Algonquin people Atsistaehronon - "Nation of Fire" (French "Nation du Feu") - but the claim that the Mascoutes had been confused with the Potawatomi could be refuted, this assumption was based on the wrong one Hypothesis that the name Potawatomi in Ojibwa means “people at the place of fire” and similar names in different languages would only refer to this tribe - however the correct meaning of the name is “keepers of the hearth fire”

- ^ Website of the Southern First Nations Secretariat

- ^ Homepage of the Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point First Nation

- ^ Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point Language, Arts, Culture, and History Online

- ^ Homepage of the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation

- ↑ Information about Bkejwanong (Walpole Island First Nation) (Engl.)

- ↑ website Ogemawahj Tribal Council. Retrieved July 5, 2016 .

- ^ Homepage of the Beausoleil First Nation

- ↑ The Odawa ( Memento of the original from January 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Today an Odawa descent is often summarized under the name Anishinabe (g) with that of the more populous Ojibwe / Chippewa (Anishinabe) - and the Odawa are often ignored as an independent people in modern reports. Due to their small number in mixed reserves , the Odawa are now something of a forgotten or at least neglected people in Ontario . Today Odawa live in various First Nations in Simcoe County and the District of Muskoka

- ↑ the IR Chippewa Island is shared by three First Nations: Beausoleil First Nation, Chippewas of Georgina Island and the Chippewas of Rama First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Moose Deer Point First Nation

- ^ Website of the Wabun Tribal Council

- ^ Homepage of the Saugeen First Nation

- ↑ the Saugeen & Cape Croker Fishing Island # 1 reserve is shared by the Saugeen First Nation with the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

- ↑ website of the Chippewas of Nawash unceded First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Wasauksing First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Wikwemikong First Nation

- ↑ a b Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 15: Northeast, pp. 740/741

- ↑ US Census 2000 (PDF; 145 kB), accessed on March 1, 2013.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Hodges, Frederick Webb (1908). "Potawatomi" in Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico

- ^ American Language Families, 7th Annual Report of the Office of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution Secretariat , 1885-1886, United States Government Printing Office, 1891

- ↑ "Potawatomi" at www.firstnationsseeker.ca

- ↑ Ethnologue: Potawatomi