Haiti: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Country in the Caribbean}} |

|||

{{Infobox_Country |

|||

{{Redirect|Hayti|other uses|Haiti (disambiguation)|and|Hayti (disambiguation)}} |

|||

|native_name = {{lang|fr|''République d'Haïti''}}<br />{{lang|ht|''Repiblik Ayiti''}} |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

|conventional_long_name = Republic of Haiti |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

|common_name = Haiti |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} |

|||

|image_flag = Flag_of_Haiti.svg |

|||

{{Infobox country |

|||

|image_coat = Coat of arms of Haiti.svg |

|||

| conventional_long_name = Republic of Haiti |

|||

|image_map = LocationHaiti.svg |

|||

| common_name = Haiti |

|||

|national_motto = ''"L'Union Fait La Force"''{{spaces|2}}<small>([[French language|French]])<br />"Unity makes Strength"</small> |

|||

| native_name = {{lang|fr-HT|République d'Haïti}}{{nbsp}}([[Haitian French|French]])<br />{{native name|ht|Repiblik d Ayiti}}<ref>[http://www.haiti.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/konstitisyon.pdf Konstitisyon Repiblik d Ayiti]</ref> |

|||

|national_anthem = ''[[La Dessalinienne]]'' |

|||

| image_flag = Flag of Haiti.svg |

|||

|official_languages = [[French language|French]], [[Haitian Creole language|Haitian Creole]] |

|||

| image_coat = Coat of arms of Haiti.svg |

|||

|demonym = Haitian |

|||

| national_motto = <div style="padding-bottom:0.3em;">{{native phrase|fr|"[[Liberté, égalité, fraternité]]"|italics=off|nolink=on}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.haiti-reference.com/histoire/constitutions/const_1987.htm |title=Article 4 of the Constitution |publisher=Haiti-reference.com |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref><br />{{native phrase|ht|"Libète, Egalite, Fratènite"|italics=off|nolink=on}}<br />"Liberty, Equality, Fraternity"</div> {{nowrap|'''Motto on traditional coat of arms:'''}}<br />{{native phrase|fr|"[[Unity makes strength|L'union fait la force]]"|italics=off|nolink=on}}<br />{{native phrase|ht|"Inite se fòs"|italics=off|nolink=on}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.haitiobserver.com/blog/tag/election/after-the-group-of-g8-now-come-g30-headed-by-louko-desir.html|title=After The Group Of G8, Now Come G30 Headed By Louko Desir|website=Haiti Observer|access-date=28 January 2018}}</ref><br />"Union makes strength" |

|||

|ethnic_groups = 95% [[Black (people)|Black]], 5% [[Mulatto|Multiracial]], [[Arab Haitian|Arab]], [[European ethnic groups|European]] |

|||

| national_anthem = {{native name|fr|[[La Dessalinienne]]|italics=off|nolink=on}}<br />{{native name|ht|Desalinyèn|italics=off|nolink=on}}<br />"The Dessalines Song"<div style="padding-top:0.5em;">{{center|[[File:Haiti National Anthem.ogg]]}}</div> |

|||

|capital = [[Port-au-Prince]] |

|||

| image_map = {{switcher | [[File:Haiti (orthographic projection).svg|frameless]] | Location in the Western Hemisphere | [[File:Map of Haiti and the neighboring countries.jpg|frameless]] | Haiti and its neighbors }} |

|||

|latd=18 |latm=32 |latNS=N |longd=72 |longm=20 |longEW=W |

|||

| image_map2 = |

|||

|largest_city = capital |

|||

| capital = [[Port-au-Prince]] |

|||

|government_type = [[Presidential system|Presidential republic]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|18|32|N|72|20|W|type:city}} |

|||

|leader_title1 = [[List of Presidents of Haiti|President]] |

|||

| largest_city = Port-au-Prince |

|||

|leader_name1 = [[René Préval]] |

|||

| official_languages = {{unbulleted list | [[Haitian French|French]] | [[Haitian Creole]] }} |

|||

|leader_title2 = [[List of Prime Ministers of Haiti|Prime Minister]] |

|||

| ethnic_groups = 95% [[Afro-Haitians|Black]]<br />5% [[Mulatto Haitians|Mixed]] or [[White Haitians|White]]<ref name="CIA_20110303" /> |

|||

|leader_name2 = [[Michèle Pierre-Louis]] |

|||

| ethnic_groups_year = |

|||

|area_rank = 147th |

|||

| religion = {{ublist |item_style=white-space:nowrap; |

|||

|area_magnitude = 1 E10 |

|||

|87.0% [[Christianity in Haiti|Christianity]] |

|||

|area_km2 = 27,751 |

|||

|10.7% [[Irreligion|no religion]] |

|||

|area_sq_mi = 10,714 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

|2.1% [[folk religion]]s |

|||

|percent_water = 0.7 |

|||

|0.2% others}} |

|||

|population_estimate = 8,706,497<ref name = "Haiti in CIA World Factbook"/> |

|||

| religion_year = 2020 |

|||

|population_estimate_rank = 85th |

|||

| religion_ref = <ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/interactives/religious-composition-by-country-2010-2050/|title=Religious Composition by Country, 2010–2050 |date=21 December 2022|publisher=[[Pew Research Center]]|accessdate=2 August 2020}}</ref> |

|||

|population_estimate_year = 2007 |

|||

| demonym = [[Haitians|Haitian]] |

|||

|population_census = 8,527,817 |

|||

| government_type = Unitary [[semi-presidential republic]] under an [[Provisional government|interim government]] |

|||

|population_census_year = 2003 |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[Transitional Presidential Council]] |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 335 |

|||

| leader_name1 = {{unbulleted list |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = 758.1 <!--Do not remove per [[WP:MOSNUM]]--> |

|||

| [[Edgard Leblanc Fils]] (Chairman) |

|||

|population_density_rank = 38th |

|||

| [[Fritz Jean]] |

|||

|GDP_PPP = $11.14 billion |

|||

| Laurent St Cyr |

|||

|GDP_PPP_rank = 133th |

|||

| Emmanuel Vertilaire |

|||

|GDP_PPP_year = 2007 |

|||

| Smith Augustin |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = $1,291 |

|||

| Leslie Voltaire |

|||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 154th |

|||

| Louis Gérald Gilles |

|||

|sovereignty_type = [[History of Haiti|Formation]] |

|||

}} |

|||

|established_event1 = as [[Saint-Domingue]] |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[Prime Minister of Haiti|Prime Minister]] |

|||

|established_date1 = 1697 |

|||

| leader_name2 = [[Fritz Bélizaire]] (acting)<ref name="Press 2024 e024">{{cite web | last=Press | first=DÁNICA COTO Associated | title=Haiti's transitional council names a new prime minister in the hopes of quelling stifling violence | website=ABC News | date=2024-04-30 | url=https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/haitis-transitional-council-names-new-prime-minister-hopes-109792487 | access-date=2024-04-30}}</ref> |

|||

|established_event2 = [[Independence]] from [[France]] |

|||

| leader_title3 = |

|||

|established_date2 = <br />1 January 1804 |

|||

| leader_name3 = |

|||

|HDI = {{increase}} 0.529 |

|||

| legislature = [[National Assembly (Haiti)|National Assembly]]{{efn|name=vacantleg|The National Assembly currently has zero members, with all 30 seats in the Senate and all 119 seats in the Chamber of Deputies vacant since all previous members have served their terms as prescribed by the [[Haitian Constitution]] and no election has been held to fill those vacated seats.}} |

|||

|HDI_rank = 146th |

|||

| upper_house = [[Senate (Haiti)|Senate]]{{efn|name=vacantleg}} (vacant) |

|||

|HDI_year = 2007 |

|||

| lower_house = [[Chamber of Deputies (Haiti)|Chamber of Deputies]]{{efn|name=vacantleg}} (vacant) |

|||

|HDI_category = <font color="#ffcc00">medium</font> |

|||

| sovereignty_type = [[Haitian Revolution|Independence from France]] |

|||

|Gini = 59.2 |

|||

| established_event1 = Independence declared |

|||

|Gini_year = 2001 |

|||

| established_date1 = 1 January 1804 |

|||

|Gini_category = <font color="#e0584e">high</font> |

|||

| established_event2 = Independence recognized |

|||

|currency = [[Haitian gourde|Gourde]] |

|||

| established_date2 = 17 April 1825 |

|||

|currency_code = HTG |

|||

| established_event3 = [[First Empire of Haiti|First Empire]] |

|||

|country_code = |

|||

| established_date3 = 22 September 1804 |

|||

|time_zone = |

|||

| established_event4 = [[State of Haiti|Southern Republic]] |

|||

|utc_offset = -5 |

|||

| established_date4 = 9 March 1806 |

|||

|cctld = [[.ht]] |

|||

| established_event5 = [[State of Haiti|Northern State]] |

|||

|calling_code = 509 |

|||

| established_date5 = 17 October 1806 |

|||

| established_event6 = [[Kingdom of Haiti|Kingdom]] |

|||

| established_date6 = 28 March 1811 |

|||

| established_event7 = [[Unification of Hispaniola]] |

|||

| established_date7 = 9 February 1822 |

|||

| established_event8 = Dissolution |

|||

| established_date8 = 27 February 1844 |

|||

| established_event9 = [[Second Empire of Haiti|Second Empire]] |

|||

| established_date9 = 26 August 1849 |

|||

| established_event10 = Republic |

|||

| established_date10 = 15 January 1859 |

|||

| established_event11 = [[United States occupation of Haiti|United States occupation]] |

|||

| established_date11 = 28 July 1915 – 1 August 1934 |

|||

| established_event12 = Independence from the United States |

|||

| established_date12 = 15 August 1934 |

|||

| established_event13 = [[Constitution of Haiti|Current constitution]] |

|||

| established_date13 = 29 March 1987 |

|||

| area_km2 = 27,750<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/haiti/summaries/#geography|title=Country Summary|publisher=Central Intelligence Agency|access-date=1 September 2023|via=CIA.gov}}</ref> |

|||

| area_rank = 143rd <!-- Area rank should match [[List of countries and dependencies by area]] --> |

|||

| area_sq_mi = 10,714 <!--Do not remove per [[Wikipedia:Manual of Style/Dates and numbers]]--> |

|||

| percent_water = 0.7 |

|||

| population_estimate = 11,470,261<ref>{{Cite CIA World Factbook|country=Haiti|access-date=22 June 2023|year=2023}}</ref> |

|||

| population_estimate_year = 2023 |

|||

| population_estimate_rank = 83rd |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 382 <!--(population_estimate ÷ area_km2)--> |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = 989.7 <!--(population_estimate ÷ area_sq_mi)--> |

|||

| population_density_rank = 32nd |

|||

| GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $38.952 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.HT">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/October/weo-report?c=263,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2020&ey=2028&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Haiti) |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |website=IMF.org |date=10 October 2023 |access-date=15 October 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| GDP_PPP_year = 2023 |

|||

| GDP_PPP_rank = 144th |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $3,185<ref name="IMFWEO.HT" /> |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 174th |

|||

| GDP_nominal = {{increase}} $25.986 billion<ref name="IMFWEO.HT" /> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_year = 2023 |

|||

| GDP_nominal_rank = 139th |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{increase}} $2,125<ref name="IMFWEO.HT" /> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 172nd |

|||

| Gini = 41.1 <!--number only--> |

|||

| Gini_year = 2012 |

|||

| Gini_change = <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

| Gini_ref = <ref name="wb-gini">{{cite web |url=http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/ |title=Gini Index |publisher=The World Bank |access-date=21 November 2015}}</ref> |

|||

| Gini_rank = |

|||

| HDI = 0.552 <!--number only--> |

|||

| HDI_year = 2022<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> |

|||

| HDI_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

| HDI_ref = <ref name="UNHDR">{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22pdf_1.pdf|title=Human Development Report 2021/2022|language=en|publisher=[[United Nations Development Programme]]|date=8 September 2022|access-date=8 September 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| HDI_rank = 158th |

|||

| currency = [[Haitian gourde|Gourde]] (G) |

|||

| currency_code = HTG |

|||

| time_zone = [[Eastern Time Zone|EST]] |

|||

| utc_offset = −5 |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = −4 |

|||

| time_zone_DST = [[Eastern Time Zone|EDT]] |

|||

| drives_on = right |

|||

| calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in Haiti|+509]] |

|||

| cctld = [[.ht]] |

|||

| country_code = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Haiti''',{{efn|{{IPAc-en|audio=En-us-Haiti.ogg|ˈ|h|eɪ|t|i}} {{respell|HAY|tee}}; [[Haitian French|French]]: {{lang|fr-HT|Haïti}} {{IPA-fr|a.iti|}}; {{lang-ht|Ayiti}} {{IPA-ht|ajiti|}}}} officially the '''Republic of Haiti''',{{efn|{{Lang-fr| République d'Haïti|links=no}}; {{Lang-ht|Repiblik d Ayiti|links=no}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00000626/00001/5j |title=Konstitisyon Repiblik Ayiti 1987 |publisher=Ufdc.ufl.edu |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref>}}{{efn|name=Hayti|1=The nation was officially founded as ''Hayti'' in its Declaration of Independence and early prints,<ref name="auto5">{{Cite web|url=http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C12756259|title=Catalogue description Haitian Declaration of Independence|date=1 January 1804|via=National Archive of the UK}}</ref><ref name="auto3">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/dol/images/examples/haiti/0001.pdf|title=National Archives – Haiti|accessdate=1 September 2023}}</ref> constitutions,<ref name="auto2">[https://sema-kama.org/la-constitution-imperiale-du-20-mai-1805/ La Constitution Impériale du 20 mai 1805]{{Dead link|date=July 2020 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> and imperial declarations.<ref name="auto4">{{Cite web|url=https://www.brown.edu/Facilities/John_Carter_Brown_Library/exhibitions/remember_haiti/rev_henri-christophe.php|title=Remember Haiti | Revolution | Royaume d'Hayti. Déclaration du roi.|website=brown.edu}}</ref> Published writings of 1802–1919 in the United States commonly used the name ''Hayti'' (e.g. ''The Blue Book of Hayti'' (1919), a book with official standing in Haiti). By 1873 ''Haiti'' was common among titles of US published books as well as in US congressional publications. In all of [[Frederick Douglass]]' publications after 1890, he used ''Haiti''. As late as 1949, the name ''Hayti'' continued to be used in books published in England (e.g. ''Hayti: 145 Years of Independence—The Bi-Centenary of Port-au-Prince'' published in London, England in 1949) but by 1950, usage in England had shifted to ''Haiti''.<ref name="auto1">{{cite web|url=http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/haiti-archive-new/msg17201.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170309003250/http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/haiti-archive-new/msg17201.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=9 March 2017 |title=17201: Corbett: Hayti and Haiti in the English language |editor=Corbett, Bob |date=9 November 2003 |publisher=Webster University |access-date=8 March 2017}}</ref>}} is a country on the island of [[Hispaniola]] in the [[Caribbean Sea]], east of [[Cuba]] and [[Jamaica]], and south of [[The Bahamas]]. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the [[Dominican Republic]].<ref name="Dardik">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=de9NDQAAQBAJ|title=Vascular Surgery: A Global Perspective |editor=Dardik, Alan |page=341 |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-319-33745-6|access-date=8 May 2017}}</ref><ref name="Current Affairs">{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5wBsDQAAQBAJ|title=Current Affairs November 2016 eBook |editor=Josh, Jagran |page=93 |year=2016 |access-date=8 May 2017}}</ref> Haiti is the third largest country in the [[Caribbean]], and with an estimated population of 11.4 million, is the most populous Caribbean country.{{UN Population|ref}} The capital and largest city is [[Port-au-Prince]]. |

|||

'''Haiti''' ('''[[English language|English]]''': {{pronEng|ˈheɪ·tiː}} or {{pronEng|haɪ·ˈjiː·tiː}}; '''[[French language|French]]''' ''[[wikt:fr:Haïti|Haïti]]'' {{pronounced|a·i·ti}}; '''[[Haitian Creole language|Haitian Creole]]''': ''Ayiti''), officially the '''Republic of Haiti''' ({{lang|fr|''République d'Haïti''}} ; {{lang|ht|''Repiblik Ayiti''}}), is a [[Haitian Creole language|Creole]]- and [[French language|French]]-speaking [[Caribbean]] nation. Along with the [[Dominican Republic]], it occupies the island of [[Hispaniola]], in the [[Greater Antilles|Greater Antillean]] [[archipelago]]. ''Ayiti'' (Land on high) was the indigenous [[Taíno]] or [[Amerindian]] name for the island. The country's highest point is [[Pic la Selle]], at {{convert|2680|m|ft|0|}}. The total area of Haiti is 27,750 [[square kilometre]]s (10,714 [[square mile|sq mi]]) and its capital is [[Port-au-Prince]]. |

|||

The island was originally inhabited by the [[Taíno]] people.<ref name="national-geographic"/> The first Europeans arrived in December 1492 during the [[Christopher Columbus#First voyage (1492–1493)|first voyage]] of [[Christopher Columbus]],<ref name="NgCheong-Lum, Roseline 19">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FUSD2v4EQE8C |title=Haiti (Cultures of the World) |last=NgCheong-Lum |first= Roseline |location=New York |publisher=Times Editions|page=19|isbn=978-0-7614-1968-6|access-date=29 September 2014|year=2005}}</ref> establishing the first European settlement in the [[Americas]], [[La Navidad]], on what is now the northeastern coast of Haiti.<ref name="Davies1953">{{cite journal|last=Davies|first=Arthur|title=The Loss of the Santa Maria Christmas Day, 1492 |journal=The American Historical Review|year=1953|pages=854–865|doi=10.1086/ahr/58.4.854}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Maclean |first= Frances| title=The Lost Fort of Columbus| url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/fort-of-columbus-200801.html| work=[[Smithsonian (magazine)|Smithsonian Magazine]]| date=January 2008| access-date=24 January 2008}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{cite web|url=http://www.nilstremmel.com/haiti/f_noframes.htm |title=Haïti histoire – 7 Bord de Mer de Limonade |publisher=Nilstremmel.com |access-date=15 July 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/histarch/ebs_intro.htm |title=En Bas Saline|date=20 September 2017|publisher=Florida Museum of Natural History}}</ref> The island formed part of the [[Spanish Empire]] until 1697, when the western portion was [[Peace of Ryswick|ceded to France]] and subsequently renamed [[Saint-Domingue]]. French colonists established [[sugarcane]] [[sugar plantations in the Caribbean|plantations]], worked by enslaved persons brought from Africa, which made the colony one of the world's richest. |

|||

Haiti's regional, historical, and ethnolinguistic position is unique for several reasons. It was the first independent nation in the Caribbean, the first [[Decolonization|post-colonial]] independent [[African|black]]-led nation in the world, and the only nation whose independence was gained as part of a successful [[slave rebellion]]. Haiti is the only predominantly [[Francophone]] nation in the Caribbean, and one of only two (along with [[Canada]]) which designate French as an official language; the other French-speaking North American countries are all [[Overseas department|overseas]] ''[[Departments of France|départements]]'' of [[France]]. |

|||

In the midst of the [[French Revolution]], enslaved persons, [[Haitian Maroon|maroons]], and [[free people of color]] launched the [[Haitian Revolution]] (1791–1804), led by a former slave and general of the [[French Army]], [[Toussaint Louverture]]. [[Napoleon]]'s forces were defeated by Louverture's successor, [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] (later Emperor Jacques I), who declared Haiti's sovereignty on 1 January 1804, leading to a [[1804 Haitian massacre|massacre of the French]]. Haiti became the first independent [[Nation state|nation]] in the [[Caribbean]], the second [[republic]] in the Americas, the first country in the Americas to officially abolish slavery, and the only country in history established by a [[Slave rebellion|slave revolt]].<ref>{{cite journal|title=Anacaona, Golden Flower|last=Danticat |first= Edwidge|journal=Journal of Haitian Studies|publisher=Scholastic Inc.|year=2005|isbn=978-0-439-49906-4|volume=11|location=New York|pages=163–165|jstor=41715319|author-link=Edwidge Danticat|issue=2}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Matthewson |first= Tim|year=1996|title=Jefferson and the Nonrecognition of Haiti|journal=Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society|volume=140|issue=1|pages=22–48|issn=0003-049X|jstor=987274}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/country_profiles/1202772.stm |title=Country profile: Haiti |date=19 January 2010 |work=BBC News |access-date=23 January 2010}}</ref> |

|||

==Derivation of the name of the country== |

|||

Haiti is the poorest country in the world. The name ''Haiti'' comes from the [[Taíno]] word ''Aytí'', which means "Mountainous Land" and referred to the entire island later called Hispaniola. The French staked their claim on the entire island based on settlement of [[Tortuga]] and [[Gonâve Island|Gonâve]] islands by French pirates in the 16th century. France officially incorporated the colony in the early 1600s. In 1697, with the signing of the [[Treaty of Ryswick]] with [[Spain]], the French took the western third of the island, naming their colony ''Saint-Domingue''. The Spanish kept control of Santo Domingo, the eastern two-thirds of the island. Following the [[Haitian Revolution|revolution]] and Saint-Domingue's declaration of independence from France on 1 January 1804, leader [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]], of African descent, restored the original Taíno name of Haiti as an ode of honor to the Amerindian predecessors and as a demonstration of defiance against France. |

|||

The first century of independence was characterized by political instability, international isolation, [[Haiti Independence Debt|crippling debt payments to France]], and a [[Dominican War of Independence|costly war]] with neighboring Dominican Republic. Political volatility and foreign economic influence prompted a [[United States occupation of Haiti|U.S. occupation from 1915 to 1934]].<ref name="Haite1934">p 223 – {{cite book| last = Benjamin Beede| title = The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898–1934: An Encyclopedia| year = 1994| edition = May 1, 1994| pages = [https://archive.org/details/americanrevoluti0000unse_o8w2/page/784 784]| publisher = Routledge; 1 edition| isbn = 0-8240-5624-8| url = https://archive.org/details/americanrevoluti0000unse_o8w2/page/784}}<BR>''The Haitian and U.S. governments reached a mutually satisfactory agreement in the Executive Accord of August 7, 1933, and on August 15, the last marines departed.''</ref> A series of unstable presidencies gave way to nearly three decades of dictatorship under the [[Duvalier dynasty|Duvalier family]] (1957–1986), which brought state-sanctioned violence, corruption, and economic stagnation. Following a [[2004 Haitian coup d'état|coup d'état in 2004]], the [[United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti|United Nations intervened]] to stabilize the country. In 2010, Haiti suffered a [[2010 Haiti earthquake|catastrophic earthquake]] that killed over 250,000 people, followed by a deadly [[2010s Haiti cholera outbreak|cholera outbreak.]] With its deteriorating economic situation,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelshellenberger/2022/09/22/haiti-riots-triggered-by-imf-advice-to-cut-fuel-subsidies/?sh=406676905169 |title=Haiti Riots Triggered By IMF Advice To Cut Fuel Subsidies |work=Forbes |last=Shellenberger |first=Michael |date=22 September 2022 |access-date=18 October 2022}}</ref> Haiti has experienced [[Haitian crisis (2018–present)|a socioeconomic and political crisis]] marked by riots and protests, widespread hunger, and increased gang activity.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/18/haiti-un-talks-gangs-hunger-cholera|title=Haiti on verge of collapse, NGOs warn as UN talks on restoring order continue|last=Taylor|first=Luke|date=18 October 2022|website=[[The Guardian]]|access-date=24 October 2022}}</ref> As of May 2024, the country has had no remaining elected government officials and has been described as a [[failed state]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jan/10/haiti-no-elected-officials-anarchy-failed-state|title=Haiti left with no elected government officials as it spirals towards anarchy|last=Taylor|first=Luke|newspaper=[[The Guardian]]|date=11 January 2023|access-date=10 February 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://news.yahoo.com/violence-haiti-worsens-canada-bets-153056650.html|title=As violence in Haiti worsens, Canada bets on assistance to police|last=Charles|first=Jacqueline|date=3 May 2023|access-date=3 May 2023|newspaper=[[Miami Herald]]}}</ref> |

|||

Haiti is a founding member of the [[United Nations]], [[Organization of American States]] (OAS),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oas.org/en/member_states/member_state.asp?sCode=HAI|title= OAS – Member State: Haiti|publisher=OAS – Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development|last=OAS|date=1 August 2009|website=oas.org}}</ref> [[Association of Caribbean States]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.acs-aec.org/sites/default/files/english_ebook_acs_20_low_res.pdf |title=Association of Caribbean States (1994–2014) |editor=Press |page=46 |year=2014 |access-date=25 April 2016}}</ref> and the {{Lang|fr|[[Organisation internationale de la Francophonie]]|italic=no}}. In addition to [[CARICOM]], it is a member of the [[International Monetary Fund]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/memdate.htm|title=International Monetary Fund: List of Members|website=imf.org}}</ref> [[World Trade Organization]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/org6_e.htm|title=WTO ¦ World Trade Organization: Members and Observers|website=wto.org}}</ref> and [[Community of Latin American and Caribbean States]]. Historically poor and politically unstable, Haiti has the lowest [[List of countries by Human Development Index|Human Development Index]] in the Americas. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

''Haiti'' (also earlier ''Hayti''){{efn|name=Hayti}} comes from the indigenous [[Taíno language]] and means "land of high mountains";<ref>{{cite book |last1=Haydn |first1=Joseph |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HOE8AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA321 |title=A Dictionary of Dates Relating to All Ages and Nations: For Universal Reference Comprehending Remarkable Occurrences, Ancient and Modern, The Foundation, Laws, and Governments of Countries-Their Progress In Civilization, Industry, Arts and Science-Their Achievements In Arms-And Their Civil, Military, And Religious Institutions, And Particularly of the British Empire |last2=Vincent |first2=Benjamin |year=1860 |page=321 |access-date=12 September 2015}}</ref> it was the native name{{efn|1=The Taínos may have used ''Bohío'' as another name for the island.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Guitar|first1=Lynne|last2=Ferbel-Azcárate|first2=Pedro|last3=Estevez|first3=Jorge|title=Indigenous Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean|date=2006|publisher=Peter Lang Publishing|location=New York|isbn=978-0-8204-7488-5|page=41|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qXZeQZMDpgYC&pg=PA41|access-date=10 July 2015|chapter=iii: Ocama-Daca Taíno (Hear me, I am Taíno)|lccn=2005012816}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Edmond|first1=Louisket|title=The Tears of Haiti|date=2010|publisher=[[Xlibris]]|isbn=978-1-4535-1770-3|page=42|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_1wDXEB1fOUC&pg=PA42|access-date=10 July 2015|lccn=2010908468}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Senauth|first1=Frank|title=The Making and Destruction of Haiti|date=2011|publisher=[[AuthorHouse]]|location=Bloomington, Indiana, US|isbn=978-1-4567-5384-9|page=1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QBdccuwnqY8C&pg=PA1|lccn=2011907203}}</ref>}} for the entire island of [[Hispaniola]]. The name was restored by Haitian revolutionary Jean-Jacques Dessalines as the official name of independent Saint-Domingue, as a tribute to the Amerindian predecessors.<ref>{{cite book|last=Martineau |first= Harriet|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lp54N7g2CYQC&pg=PA12|title=The Hour and the Man: A Fictional Account of the Haitian Revolution and the life of Toussaint L'Ouverture|year=2010|isbn=978-99904-1-167-6|page=12|publisher= Aruba Heritage Foundation|access-date=12 September 2015}}</ref> |

|||

In French, the ''[[ï]]'' in ''Ha'''ï'''ti'' has a [[Diaeresis (diacritic)#French|diacritical mark]] (used to show that the second vowel is pronounced separately, as in the word ''na'''ï'''ve''), while the ''H'' is silent.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stein |first= Gail |title=The Complete Idiot's Guide to Learning French|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zaT3kj55aTcC&pg=PA18|year=2003|publisher=Alpha Books|isbn=978-1-59257-055-3|page=18}}</ref> (In English, this rule for the pronunciation is often disregarded, thus the spelling ''Haiti'' is used.) There are different anglicizations for its pronunciation such as ''HIGH-ti'', ''high-EE-ti'' and ''haa-EE-ti'', which are still in use, but ''HAY-ti'' is the most widespread and best-established.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/legacy/magazinemonitor/2010/01/how_to_say_haiti_and_portaupri.shtml |title=How to Say: Haiti and Port-au-Prince |publisher=BBC |access-date=19 November 2014 |archive-date=19 November 2014 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20141119070029/http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/legacy/magazinemonitor/2010/01/how_to_say_haiti_and_portaupri.shtml |url-status=dead }}</ref> In French, Haiti's nickname means the "Pearl of the Antilles" (''La Perle des Antilles'') because of both its natural beauty<ref>{{cite web |last=Eldin |first=F. |year=1878 |title=Haïti, 13 ans de séjour aux Antilles |trans-title=Haiti, 13 years of stay in the Antilles |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3xAIAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA33 |access-date=21 July 2015 |page=33 |language=fr}}</ref> and the amount of wealth it accumulated for the [[Kingdom of France]].<ref>{{Cite web |year=1797 |title=Voyage a Saint-Domingue, pendant les années 1788, 1789 et 1790 |trans-title=Travel to Santo Domingo, during the years 1788, 1789 and 1790 |url=https://archive.org/details/voyagesaintdomin00wimp |access-date=31 March 2018 |language=fr}}</ref> In [[Haitian Creole]], it is spelled and pronounced with a ''y'' but no ''H'': {{lang-ht|Ayiti|label=none}}''.'' |

|||

Another theory on the name Haiti is its origin in African tradition; in Fon language, one of the most spoken by the bossales (Haitians born in Africa), [http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/haiti-archive/msg02162.html Ayiti-Tomè] means: "From nowadays this land is our land."{{Citation needed|date=April 2024}} |

|||

In the Haitian community the country has multiple nicknames: Ayiti-Toma (as its origin in Ayiti Tomè), Ayiti-Cheri (Ayiti my Darling), Tè-Desalin (Dessalines' Land) or Lakay (Home). |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|History of Haiti}} |

||

{{seealso|Politics of Haiti|Elections in Haiti|National Assembly of Haiti|President of Haiti|2004 Haitian rebellion|United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti}}<!--Please add new information to relevant articles of the series--> |

|||

===The Taíno=== |

|||

The island of [[Hispaniola]], of which Haiti occupies the western third, was originally inhabited by the [[Taíno]] [[Arawak]]s, a seafaring branch of the South American Arawaks. [[Christopher Columbus]] landed at [[Môle Saint-Nicolas]] on 5 December 1492, and claimed the island for Spain. Nineteen days later, his ship the [[Santa Maria]] ran aground near the present site of [[Cap-Haitien]]; Columbus was forced to leave 39 men, founding the settlement of [[La Navidad]]. Ayti, which means "mountainous land", is a name used by the Taíno-Arawak people, who also called some sections of it Bohio, meaning "rich villages". Kiskeya is yet a third term that has been attributed to the Taínos for the island. |

|||

===Taino history=== |

|||

The Taíno population on Hispaniola was divided through a system of established ''cacicazgos'' (chiefdoms), named Marien, Maguana, Higuey, Magua and Xaragua, which could be further subdivided. The cacicazgos (later called ''caciques'' in French) were tributary kingdoms, with payment consisting of food grown by the Taíno. Taino cultural artifacts include cave paintings in several locations in the nation, which have become national symbols of Haiti and tourist attractions. Modern-day [[Léogane]], a town in the southwest, is at the epicenter of what was the chiefdom of Xaragua. |

|||

[[File:Copia de Cacicazgos de la Hispaniola.png|thumb|upright=1.6|The five [[cacique]]doms of Hispaniola at the time of the arrival of Christopher Columbus]] |

|||

The island of [[Hispaniola]], of which Haiti occupies the western three-eighths,<ref name="Dardik" /><ref name="Current Affairs" /> has been inhabited since about 5000 BC by groups of Native Americans thought to have arrived from Central or South America.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti">[https://www.britannica.com/place/Haiti "Haiti"]</ref> Genetic studies show that some of these groups were related to the [[Yanomami]] of the [[Amazon Basin]].<ref name="national-geographic">{{cite news |last1=Lawler |first1=Andrew |title=Invaders nearly wiped out Caribbean's first people long before Spanish came, DNA reveals |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/12/invaders-nearly-wiped-out-caribbeans-first-people-long-before-spanish-came-dna-reveals/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201223160603/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/12/invaders-nearly-wiped-out-caribbeans-first-people-long-before-spanish-came-dna-reveals/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=23 December 2020 |work=National Geographic |date=23 December 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=LALUEZA-FOX |first1=C.|last2=CALDERÓN|first2=F. LUNA|date=2001|title=MtDNA from extinct Tainos and the peopling of the Caribbean|journal=Annals of Human Genetics|volume=2001|issue=65|pages=137–151|doi=10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6520137.x|s2cid=221450280|doi-access=free}}</ref> Amongst these early settlers were the [[Ciboney]] peoples, followed by the [[Taíno people|Taíno]], speakers of an [[Arawakan]] [[Taíno language|language]], elements of which have been preserved in [[Haitian Creole]]. The Taíno name for the entire island was ''Haiti'', or alternatively ''Quisqeya''.<ref name="Bradt9">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 9.</ref>{{Main|Chiefdoms of Hispaniola}}In Taíno society the largest unit of political organization was led by a ''[[cacique]]'', or chief, as the Europeans understood them. The island of Hispaniola was divided among five 'caciquedoms': the Magua in the northeast, the Marien in the northwest, the Jaragua in the southwest, the Maguana in the central regions of Cibao, and the Higüey in the southeast.<ref>{{cite book|last=Cassá |first= Roberto |title=Los Indios de Las Antillas|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJ-wJ49cNwAC&pg=PA126|year=1992|publisher=Editorial Abya Yala|isbn=978-84-7100-375-1|pages=126–}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Samuel M.|last=Wilson|year=1990|title=Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus|publisher=University of Alabama Press|page=110|isbn=978-0-8173-0462-1}}</ref> |

|||

Taíno cultural artifacts include [[cave paintings]] in several locations in the country. These have become national symbols of Haiti and tourist attractions. Modern-day [[Léogâne]], started as a French colonial town in the southwest, is beside the former capital of the caciquedom of ''Xaragua.''<ref name="royal">{{cite journal|url=http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/ant/ROYAL-01.ANT|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090216092556/http://www.millersville.edu/~columbus/data/ant/ROYAL-01.ANT|archive-date= 16 February 2009|title=1492 and Multiculturalism|last=Royal |first= Robert |journal=The Intercollegiate Review|date=Spring 1992|volume=27|issue=2|pages=3–10}}</ref> |

|||

Following the destruction of La Navidad by the Amerindians, Columbus moved to the eastern side of the island and established [[La Isabela]]. One of the earliest leaders to fight off Spanish conquest was Queen [[Anacaona]], a Taíno princess from Xaragua who married Chief Caonabo, a Taíno king (cacique) from Maguana. The two resisted European rule but to no avail; she was captured by the Spanish and executed in front of her people. To this day, Anacaona is revered in Haiti as one of the country's first founders, preceding the likes of founding fathers such as [[Toussaint Louverture]] and [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]]. The [[Spaniards]] exploited the island for its gold, mined chiefly by local [[Amerindians]] directed by the Spanish occupiers. Those refusing to work in the mines were slaughtered or forced into slavery. Europeans brought chronic infectious diseases with them that were new to the Caribbean. Diseases were the most powerful of the elements because the Taíno had no natural immunity, but ill treatment, malnutrition and a drastic drop of the birthrate also contributed to decimation of the indigenous population. |

|||

===Colonial era=== |

|||

The Spanish governors began importing enslaved Africans for labor. In 1517, [[Carlos V, Holy Roman Emperor]] and [[King of Spain]], authorized the draft of slaves. The Taínos became virtually extinct on the island of Hispaniola. Some who evaded capture fled to the mountains and established independent settlements. There survivors mixed with escaped African slaves (runaways called maroons) and produced a multiracial generation called ''zambos''. French settlers later called people of mixed African and Amerindian ancestry ''[[Marabou (ethnicity)|marabou]]''. The ''mestizo'' increased in number from children born to relationships between native women and European men. Others were born as a result of unions between African women and European men, who were called ''mulatto'' in Spanish and ''mulâtre'' in French. |

|||

====Spanish rule (1492–1625)==== |

|||

{{Main|Columbian Viceroyalty|New Spain|Captaincy General of Santo Domingo}} |

|||

[[File:Columbus landing on Hispaniola adj.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|right|[[Artist's impression]] of [[Christopher Columbus]] landing on [[Hispaniola]], engraving by [[Theodor de Bry]]]] |

|||

Navigator [[Christopher Columbus]] landed in Haiti on 6 December 1492, in an area that he named ''[[Môle-Saint-Nicolas]]'',<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924097691590|title=Columbus the Discoverer |editor=Ober, Frederick Albion |page=[https://archive.org/details/cu31924097691590/page/n119 96] |year=1906 |publisher=Harper & Brothers Publishers New York and London |access-date=2 December 2015}}</ref> and claimed the island for the [[Crown of Castile]]. Nineteen days later, his ship the ''[[Santa María (ship)|Santa María]]'' ran aground near the present site of [[Cap-Haïtien]]. Columbus left 39 men on the island, who founded the settlement of [[La Navidad]] on 25 December 1492.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> Relations with the native peoples, initially good, broke down and the settlers were later killed by the Taíno.<ref name="Bradt10">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 10.</ref> |

|||

The sailors carried endemic Eurasian [[infectious disease]]s, causing [[epidemic]]s that killed a large number of native people.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/What-Became-of-the-Taino.html|title=What Became of the Taíno?|journal=[[Smithsonian (magazine)|Smithsonian]]|date=October 2011|access-date=16 October 2013|archive-date=7 December 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131207130050/http://www.smithsonianmag.com/people-places/What-Became-of-the-Taino.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Koplow |first= David A. |title=Smallpox: The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge|url=https://archive.org/details/smallpoxfighttoe00kopl|url-access=registration |year=2004|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-24220-3}}</ref> The first recorded [[smallpox]] epidemic in the Americas erupted on Hispaniola in 1507.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/preparedness/bt_public_history_smallpox.shtm |title=History of Smallpox – Smallpox Through the Ages |publisher=Texas Department of State Health Services |access-date=24 July 2013 |archive-date=24 September 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190924141608/https://www.dshs.state.tx.us/preparedness/bt_public_history_smallpox.shtm |url-status=dead }}</ref> Their numbers were further reduced by the harshness of the ''{{lang|es|[[encomienda]]}}'' system, in which the Spanish forced natives to work in gold mines and plantations.<ref>{{cite book|last=Graves |first= Kerry A. |title=Haiti|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8b047XP92i4C&pg=PA22|date=2002|publisher=Capstone|isbn=978-0-7368-1078-4|page=22}}</ref><ref name="Bradt10"/> |

|||

The western part of Hispaniola soon was settled by French [[buccaneer]]s. Among them, Bertrand D'Ogeron succeeded in growing tobacco, which prompted many of the numerous buccaneers and freebooters to turn into settlers. This population did not submit to Spanish royal authority until the year 1660 and caused a number of conflicts. |

|||

The Spanish passed the [[Laws of Burgos]] (1512–1513), which forbade the maltreatment of natives, endorsed their [[Proselytism|conversion]] to Catholicism,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://faculty.smu.edu/bakewell/BAKEWELL/texts/burgoslaws.html |title=Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513 |publisher=Faculty.smu.edu |access-date=24 July 2013 |archive-date=6 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190606074822/http://faculty.smu.edu/bakewell/bakewell/texts/burgoslaws.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> and gave legal framework to ''{{lang|es|encomiendas}}.'' The natives were brought to these sites to work in specific plantations or industries.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/186567/encomienda |title=Encomienda (Spanish policy) |encyclopedia=Britannica.com |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref> |

|||

===17th century settlement=== |

|||

Bertrand D'Orgeron attracted many colonists from [[Martinique]] and [[Guadeloupe]], such as the Roy family (Jean Roy, 1625-1707), Hebert (Jean Hebert, 1624, with his family) and the Barre (Guillaume Barre, 1642, with his family), driven out by pressure on lands generated by extension of sugar plantations. From 1670 to 1690, a drop in the tobacco markets affected the island and significantly reduced the number of settlers. Freebooters grew stronger, plundering settlements, such as those of Vera Cruz in 1683 and Campêche in 1686. [[Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Seignelay]], elder son of [[Jean-Baptiste Colbert]] and Minister of the Navy, brought back some order. He ordered the establishment of [[indigo]] and [[sugar cane]] plantations. The first windmill for processing sugar was created in 1685. |

|||

As the Spanish re-focused their colonization efforts on the greater riches of mainland Central and South America, Hispaniola became reduced largely to a trading and refueling post. As a result [[Piracy in the Caribbean|piracy]] became widespread, encouraged by European powers hostile to Spain such as France (based on [[Tortuga (Haiti)|Île de la Tortue]]) and England.<ref name="Bradt10"/> The Spanish largely abandoned the western third of the island, focusing their colonization effort on the eastern two-thirds.<ref>Knight, Franklin, ''The Caribbean: The Genesis of a Fragmented Nationalism'', 3rd edn, p. 54, New York, Oxford University Press 1990.</ref><ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> The western part of the island was thus gradually settled by French [[buccaneer]]s; among them was Bertrand d'Ogeron, who succeeded in growing [[tobacco]] and recruited many French colonial families from [[Martinique]] and [[Guadeloupe]].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Ducoin, Jacques.|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/849870919|title=Bertrand d'Ogeron, 1613–1676 : fondateur de la colonie de Saint-Domingue et gouverneur des flibustiers|year=2013|isbn=978-2-84833-294-9|location=Brest|oclc=849870919}}</ref> In 1697 [[Kingdom of France|France]] and [[Imperial Spain|Spain]] settled their hostilities on the island by way of the [[Treaty of Ryswick]] of 1697, which divided Hispaniola between them.<ref name="Bradt11">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 11.</ref><ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> |

|||

===Treaty of Ryswick=== |

|||

France and Spain settled hostilities on the island by the [[Treaty of Ryswick]] of 1697, which divided Hispaniola between them. France received the western third and subsequently named it [[Saint-Domingue]]. Many French colonists soon arrived and established plantations in Saint-Domingue due to high profit potential. From 1713 to 1787, approximately 30,000 colonists, emigrated from [[Bordeaux]], France to the western part of the island. By about 1790, Saint-Domingue had greatly overshadowed its eastern counterpart in terms of wealth and population. It quickly became the richest French colony in the New World due to the immense profits from the sugar, coffee and indigo industries. The labor and knowledge of thousands of enslaved Africans made it possible, who brought skills and technology for indigo production to the island. The French-enacted [[Code Noir]] (Black Code), prepared by [[Colbert]] and ratified by [[Louis XIV]], established rigid rules on slave treatment and permissible freedom. |

|||

=== |

====French rule (1625–1804)==== |

||

{{Main|Saint-Domingue|French West Indies}} |

|||

{{main|Haitian Revolution}} |

|||

The [[French Revolution]] contributed to social upheavals in Saint-Domingue and the French and West Indies. Most important was the revolution of the slaves in Saint-Domingue, starting on the northern plains in 1791. In 1792 the French government sent three commissioners with troops to try to reestablish control. They began to build an alliance with [[gens de couleur]], who were looking for their rights. In 1793, France and Great Britain went to war, and British troops invaded Saint-Domingue. The execution of [[Louis XVI]] heightened tensions in the colony. To build an alliance with the gens de couleur and slaves, the French commissioners [[Sonthonax]] and [[Polverel]] abolished slavery in the colony. Six months later, the national [[Convention]] endorsed abolition and extended it to all of the French colonies. |

|||

France received the western third and subsequently named it Saint-Domingue, the French equivalent of ''[[Captaincy General of Santo Domingo|Santo Domingo]]'', the Spanish colony on [[Hispaniola]].<ref name="firstcolony">{{cite web |url=http://countrystudies.us/dominican-republic/3.htm |title=Dominican Republic – The first colony |access-date= 19 June 2006 |work=Country Studies |publisher=[[Library of Congress]]; [[Federal Research Division]]}}</ref> The French set about creating sugar and coffee plantations, worked by vast numbers of those enslaved imported from [[Africa]], and Saint-Domingue grew to become their richest colonial possession,<ref name="Bradt11"/><ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> generating 40% of France’s foreign trade and doubling the wealth generation of all of England’s colonies, combined.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Walter E. Kretchik |chapter=1. Haitian Culture and Military Power |date=2016 |language=en |page=6 |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |quote=the French colony’s seven thousand plantations to produce 40 percent of France’s foreign trade, nearly double the production of all British colonies combined |title=Eyewitness to Chaos: Personal Accounts of the Intervention in Haiti, 1994}}<!-- auto-translated from Spanish by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> |

|||

[[Toussaint Louverture]], a former slave and leader in the slave revolt who rose in importance as a military commander because of his many skills, achieved peace in Saint-Domingue after years of war against both external invaders and internal dissension. He had established a disciplined, flexible army and driven out both the Spaniards and the English invaders who threatened the colony. He restored stability and prosperity by daring measures, including inviting the return of planters and insisting that freedmen work on plantations to renew revenues for the island. He also renewed trading ties with [[Great Britain]] and the [[United States]]. Finally France appointed him Governor. |

|||

The French settlers were outnumbered by enslaved persons by almost 10 to 1.<ref name="Bradt11"/> According to the 1788 Census, Haiti's population consisted of nearly 25,000 Europeans, 22,000 free coloreds and 700,000 Africans in slavery.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Coupeau| first=Steeve|title=The History of Haiti|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=tA-XfYZFNvkC&pg=PA18|publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group|year=2008|page=18|isbn=978-0-313-34089-5}}</ref> In contrast, by 1763 the white population of [[New France|French Canada]], a far larger territory, had numbered only 65,000.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://faculty.marianopolis.edu/c.belanger/QuebecHistory/encyclopedia/ImmigrationHistoryofCanada.htm |title=Immigration History of Canada |publisher=Faculty.marianopolis.edu |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref> In the north of the island, those enslaved were able to retain many ties to African cultures, religion and language; these ties were continually being renewed by newly imported Africans. Some West Africans in slavery held on to their traditional [[Haitian Vodou|Vodou]] beliefs by secretly syncretizing it with Catholicism.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> |

|||

===Independence=== |

|||

The French government changes and the legislature began to rethink its decisions on slavery in the colonies. After [[Toussaint Louverture]] created a separatist constitution, [[Napoleon Bonaparte]] sent an expedition of 30,000 men under the command of his brother-in-law, General [[Charles Leclerc]], to retake the island. Bonaparte was influenced by [[Creole peoples|Creole]] planters and traders. Leclerc's mission was to oust Louverture and restore slavery. The French achieved some victories. In addition, Leclerc kidnapped Toussaint Louverture and sent him to France, where he was imprisoned at Fort Le Joux. He died there of malnutrition and pneumonia. |

|||

The French enacted the ''[[Code Noir]]'' ("Black Code"), prepared by [[Jean-Baptiste Colbert]] and ratified by [[Louis XIV]], which established rules on slave treatment and permissible freedoms.<ref name="Bradt12">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 12.</ref> Saint-Domingue has been described as one of the most brutally efficient slave colonies; at the end of the eighteenth century it was supplying two-thirds of Europe's tropical produce while one-third of newly imported Africans died within a few years.<ref name="Farmer-LROB">{{cite web |last=Farmer |first= Paul | title=Who removed Aristide? |access-date=19 February 2010 |date=15 April 2004 |url=http://www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n08/farm01_.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080608222428/http://www.lrb.co.uk/v26/n08/farm01_.html |archive-date=8 June 2008 }}</ref> Many enslaved persons died from diseases such as [[smallpox]] and [[typhoid fever]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kiple |first= Kenneth F. | title = The Caribbean Slave: A Biological History | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=veMLoyrX0BEC| publisher = Cambridge University Press | year = 2002 | page = 145 | isbn = 978-0-521-52470-4 }}</ref> They had low [[birth rate]]s,<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6K-DocgDY6gC&pg=PA119|title=Sugar Island Slavery in the Age of Enlightenment: The Political Economy of the Caribbean World|author-link1=Arthur Stinchcombe|last=Stinchcombe|first=Arthur L.|date=11 December 1995|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-1-4008-2200-3|language=en}}</ref> and there is evidence that some women [[abortion|aborted]] fetuses rather than give birth to children within the bonds of [[slavery]].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_z17AAAAMAAJ|title=Journal of Haitian Studies|date=2001|publisher=Haitian Studies Association|pages=67|language=en}}</ref> The colony's environment also suffered, as forests were cleared to make way for plantations and the land was overworked so as to extract maximum profit for French plantation owners.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> |

|||

The native leader [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]], long an ally of Toussaint Louverture, defeated the French troops led by [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau]] at the [[Battle of Vertières]]. At the end of the double battle for emancipation and independence, former slaves proclaimed the independence of Saint-Domingue on 1 January 1804, declaring the new nation as Haiti, honoring the original indigenous Taíno name for the island. Haiti was consequently the first country in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery. |

|||

[[File:Fire in Saint-Domingo 1791, German copper engraving.jpg|thumb|Saint-Domingue [[Slave rebellion|slave revolt]] in 1791]] |

|||

Dessalines was proclaimed governor for life by his troops. He exiled the remaining whites and ruled as a despot. He was assassinated on 17 October 1806. The country was divided then between a kingdom in the north directed by [[Henri Christophe]], and a republic in the south directed by a ''gens de couleur'' [[Alexandre Pétion]]. President [[Jean Pierre Boyer]], also a ''gens de couleur'', managed to reunify these two parts and extend control again over the eastern part of the island. |

|||

As in its [[Louisiana (New France)|Louisiana colony]], the [[New France|French colonial]] government allowed some rights to [[free people of color]] ({{Lang|fr|gens de couleur}}), the [[mixed-race]] descendants of European male colonists and African enslaved females (and later, mixed-race women).<ref name="Bradt11"/> Over time, many were released from slavery and they established a separate [[social class]]. White French [[Creole peoples|Creole]] fathers frequently sent their mixed-race sons to [[France]] for their education. Some men of color were admitted into the military. More of the free people of color lived in the south of the island, near [[Port-au-Prince]], and many intermarried within their community.<ref name="Bradt11"/> They frequently worked as artisans and tradesmen, and began to own some property, including enslaved persons of their own.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/><ref name="Bradt11"/> The free people of color petitioned the [[New France|colonial]] government to expand their rights.<ref name="Bradt11"/> |

|||

The brutality of slave life led many people in bondage to escape to mountainous regions, where they set up their own autonomous communities and became known as [[Haitian Maroon|maroons]].<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> One maroon leader, [[François Mackandal]], led a rebellion in the 1750s; however, he was later captured and executed by the French.<ref name="Bradt11"/> |

|||

In July 1825, the king of France [[Charles X]] sent a fleet of fourteen vessels and troops to reconquer the island. To maintain independence, President Boyer agreed to a treaty by which France recognized the independence of the country in exchange for a payment of 150 million francs (the sum was reduced in 1838 to 90 million francs). |

|||

====Haitian Revolution (1791–1804)==== |

|||

A long succession of coups followed the departure of Jean-Pierre Boyer. National authority was disputed by factions of the army, the |

|||

{{Main|Haitian Revolution}} |

|||

elite class and the growing commercial class, now made up of numerous immigrants: [[Germans]], [[United States|Americans]], [[French people|French]] and [[English people|English]]. |

|||

[[File:Général Toussaint Louverture.jpg|thumb|upright|General Toussaint Louverture]] |

|||

Inspired by the [[French Revolution]] of 1789 and principles of the [[rights of man]], the French settlers and free people of color pressed for greater political freedom and more [[civil rights]].<ref name="Bradt12"/> Tensions between these two groups led to conflict, as a militia of free-coloreds was set up in 1790 by [[Vincent Ogé]], resulting in his capture, torture and execution.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> Sensing an opportunity, in August 1791 the first slave armies were established in northern Haiti under the leadership of [[Toussaint Louverture]] inspired by the Vodou ''houngan'' (priest) Boukman, and backed by the Spanish in Santo Domingo – soon a full-blown slave rebellion had broken out across the entire colony.<ref name="Encylopedia Britannica - Haiti"/> |

|||

In 1792, the [[French First Republic|French]] government sent three commissioners with troops to re-establish control; to build an alliance with the ''[[gens de couleur]]'' and enslaved persons commissioners [[Léger-Félicité Sonthonax]] and [[Étienne Polverel]] abolished slavery in the colony.<ref name="Bradt12"/> Six months later, the [[National Convention]], led by [[Maximilien de Robespierre]] and the [[Jacobin Club|Jacobins]], endorsed [[abolition of slavery timeline|abolition]] and extended it to all the French colonies.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/291/ |title=Decree of the National Convention of 4 February 1794, Abolishing Slavery in all the Colonies |publisher=Chnm.gmu.edu |access-date=24 July 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110603234817/http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/291/ |archive-date=3 June 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

===Twentieth century=== |

|||

The United States [[United States occupation of Haiti|occupied]] the island from 1915 to 1934. From 1957 to 1986, the [[Duvalier]] family reigned as dictators. They created the private army and terrorist death squads known as ''[[Tonton Macoute]]s''. Many Haitians fled to exile in the United States and [[Canada]], especially French-speaking [[Quebec]]. |

|||

The [[United States]], which was a new republic itself, oscillated between supporting or not supporting [[Toussaint Louverture]] and the emerging country of Haiti, depending on who was President of the US. Washington, who was a slave holder and isolationist, kept the United States neutral, although private US citizens at times provided aid to French [[Planter (plantation owner)|planters]] trying to put down the revolt. John Adams, a vocal opponent of slavery, fully supported the slave revolt by providing diplomatic recognition, financial support, munitions and warships (including the [[USS Constitution]]) beginning in 1798. This support ended in 1801 when Jefferson, another slave-holding president, took office and recalled the US Navy.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/HaitianRev |title=1784–1800 – The United States and the Haitian Revolution |publisher=History.state.gov |access-date=24 July 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130920081517/http://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/HaitianRev |archive-date=20 September 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/22/books/poles-in-haiti.html |title=Poles in Haiti |work = [[The New York Times]] |date=22 March 1987 |access-date=24 July 2013 |last=Joseph|first= Raymond A.|author-link=Raymond Joseph}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/john-adams-supports-toussaint-louverture-horrifies-jefferson/ |title=John Adams Supports Toussaint Louverture, Horrifies Jefferson|date=29 March 2017}}</ref> |

|||

In December 1990, the former priest [[Jean-Bertrand Aristide]] won the [[Haitian general election, 1990–1991|election]]. His mandate began on 7 February 1991. During August, 1991, Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s government faced a non-confidence vote within the Haitian Chamber of Deputies and Senate. 83 voted against him, and only 11 members voted in support of Aristide’s government. On 29 September 1991 President Aristide resigned and flew into exile. In accordance with Article 149, of Haiti’s Constitution of 1987, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Nerette was named Provisional President and elections were called for December, 1991. These were blocked by the international community and chaos resulted extending into 1994. |

|||

With slavery abolished, Toussaint Louverture pledged allegiance to France, and he fought off the British and Spanish forces who had taken advantage of the situation and invaded Saint-Domingue.<ref name="Latin America's Wars: Volume 1">{{cite book|last1=Scheina|first1=Robert L.|title=Latin America's Wars: Volume 1|date=2003|publisher=Potomac Books}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution|date=2009|publisher=[[Harvard University Press]]|page=182}}</ref> The Spanish were later forced to cede their part of the island to France under the terms of the [[Peace of Basel]] in 1795, uniting the island under one government. However, an insurgency against French rule broke out in the east, and in the west there was fighting between Louverture's forces and the free people of color led by [[André Rigaud]] in the [[War of the Knives]] (1799–1800).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www2.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/revolution/revolution3.htm |title=The Haitian Revolution of 1791–1803 |first=Bob |last=Corbett |publisher=Webster University}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Smucker|first=Glenn R.|at=Toussaint Louverture|url=http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/httoc.html|title=A Country Study: Haiti|editor=Richard A. Haggerty|publisher=Library of Congress Federal Research Division|date=December 1989}}</ref> The United States' support for the blacks in the war contributed to their victory over the mulattoes.<ref name=YPT/> More than 25,000 whites and free blacks left the island as refugees.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Magazine |first=Smithsonian |title=The History of the United States' First Refugee Crisis |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-united-states-first-refugee-crisis-180957717/ |access-date=10 June 2022 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en|quote=In spite of all this paranoia, however, South Carolina actually lifted its ban on foreign slaves in 1804, and all those who arrived from Saint-Domingue eventually settled there. According to Dessens, many were even welcomed quite warmly. This was especially true for the 8,000 or so of the 25,000 refugees who shared both skin color and a common religion with their American counterparts.}}</ref> |

|||

In 1994, Haitian [[General officer|General]] [[Raoul Cédras]] asked former [[U.S. President]] [[Jimmy Carter]] to help avoid a [[U.S. military]] [[invasion]] of Haiti.<ref name="CCHaiti">{{Citation | author= The Carter Center| title="Activities by Country: Haiti"|url=http://www.cartercenter.org/countries/haiti.html|accessdate=2008-07-17}}</ref> President Carter relayed this information to [[Bill Clinton|President Clinton]], who asked Carter, in his role as founder of [[Carter Center|The Carter Center]], to undertake a mission to Haiti with Sen. [[Sam Nunn]], D-Ga., and former [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]] Chairman [[Colin Powell]].<ref name="CCHaiti"/> The team successfully negotiated the departure of Haiti's military leaders, paving the way for the restoration of Jean-Bertrande Aristide as president.<ref name="CCHaiti"/> |

|||

[[File:Battle for Palm Tree Hill.jpg|thumb|Battle between [[Polish Legions (Napoleonic period)|Polish troops]] in French service and the [[Haitian Revolution|Haitian rebels]]. The majority of Polish soldiers eventually deserted the French army and fought alongside the Haitians.]] |

|||

Aristide left the presidency in 1995. He was [[Haitian general election, 2000|re-elected in 2000]]. The election of 2000 was not recognized by the international community, which claimed that massive fraud had taken place{{Fact|date=September 2008}}. The country continued to struggle. In 2004, after several months of popular demonstrations against him because of a poor economy and his corruption, and pressures exerted by the international community, especially by France, the USA and Canada, Aristide went into exile on 29 February 2004. |

|||

After Louverture created a separatist constitution and proclaimed himself governor-general for life, [[Napoléon Bonaparte]] in 1802 sent an expedition of 20,000 soldiers and as many sailors<ref>{{cite book|last=Frasier |first= Flora|title=Venus of Empire:The Life of Pauline Bonaparte|publisher=John Murray|date=2009}}</ref> under the command of his brother-in-law, [[Charles Leclerc (general, born 1772)|Charles Leclerc]], to reassert French control. The French achieved some victories, but within a few months most of their [[French Army|army]] had died from [[yellow fever]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/napoleon/yellow_fever_haiti.htm |title=The Haitian Debacle: Yellow Fever and the Fate of the French |publisher=Montana State University |access-date=24 July 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131207060224/http://entomology.montana.edu/historybug/napoleon/yellow_fever_haiti.htm |archive-date=7 December 2013 }}</ref> Ultimately more than 50,000 French troops died in an attempt to retake the colony, including 18 generals.<ref>{{cite news|author=Adam Hochschild |url=http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2004/05/30/CMGKG6F3UV1.DTL |title=Birth of a Nation / Has the bloody 200-year history of Haiti doomed it to more violence? |work=San Francisco Chronicle |date=30 May 2004 |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref> The French managed to capture Louverture, transporting him to France for trial. He was imprisoned at [[Fort de Joux]], where he died in 1803 of exposure and possibly [[tuberculosis]].<ref name="Farmer-LROB" /><ref name="Bradt13">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 13.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Revenge taken by the Black Army for the Cruelties practised on them by the French.png|thumb|Haitians hanging French soldiers]] |

|||

The enslaved persons, along with free {{Lang|fr|gens de couleur}} and allies, continued their fight for independence, led by generals [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]], [[Alexandre Pétion]] and [[Henry Christophe]].<ref name="Bradt13"/> The rebels finally managed to decisively defeat the French troops at the [[Battle of Vertières]] on 18 November 1803, establishing the first nation ever to successfully gain independence through a slave revolt.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Jackson|first1=Maurice|last2=Bacon|first2=Jacqueline|editor1-last=Jackson |editor1-first=Maurice |editor2-last=Bacon |editor2-first=Jacqueline|chapter=Fever and Fret: The Haitian Revolution and African American Responses|date=2010|title=African Americans and the Haitian Revolution: Selected Essays and Historical Documents|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dZDcAAAAQBAJ&q=African%20American%20and%20the%20Haitian%20Revolution&pg=PT14 |access-date=10 October 2018 |publisher=Routledge |quote=...the momentous struggle that began in 1791 and yielded the first post-colonial independent black nation and the only nation to gain independence through slave rebellion.|isbn=978-1-134-72613-4}}</ref> Under the overall command of Dessalines, the Haitian armies avoided open battle, and instead conducted a successful guerrilla campaign against the Napoleonic forces, working with diseases such as yellow fever to reduce the numbers of French soldiers.<ref>C.L.R. James, ''Black Jacobins'' (London: Seckur & Warburg, 1938)</ref> Later that year France withdrew its remaining 7,000 troops from the island and Napoleon gave up his idea of re-establishing a North American empire, selling [[Louisiana (New France)]] to the [[United States]], in the [[Louisiana Purchase]].<ref name="Bradt13"/> |

|||

Throughout the revolution, an estimated 20,000 French troops succumbed to yellow fever, while another 37,000 were [[killed in action]],<ref>{{cite web |title=The Haitian Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase |url=https://gazette.com/woodmenedition/jefferson-the-haitian-revolution-and-the-louisiana-purchase-get-out-of-town/article_e5b9a5de-88b2-11ea-9b22-1f1cf7020e1f.amp.html |website=The Gazette}}</ref> exceeding the total French soldiers killed in action across various 19th-century colonial campaigns in Algeria, Mexico, Indochina, Tunisia, and West Africa, which resulted in approximately 10,000 French soldiers killed in action combined.<ref>{{cite book |title=Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. | isbn=9780786474707 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8urEDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA199|quote=French losses from 1830–51 were 3,336 killed in battle and 92,329 died of wounds or from all other causes. Between 1830 and 1870, 411 French officers were killed and 1,360 were wounded. The toll for the ranks was an estimated 10,000 killed and 35,000 wounded in all French colonial campaigns. A few thousand from this number died in Mexico or Indochina, but the great bulk met their deaths in Algeria. Disease took an even greater toll. One estimate puts total French and Foreign Legion deaths from battle and disease for the entire century at 110,000. | last1=Clodfelter | first1=Micheal | date=23 May 2017 | publisher=McFarland }}</ref> The British sustained 100,000 casualties.<ref name=YPT>{{cite web |title=Haitian Revolution: A YPT Guide|url=https://www.youngpioneertours.com/haitian-revolution-ypt-guide/ |website=Young Pioneer Tours|date=7 March 2020 }}</ref> Additionally, 350,000 ex-enslaved Haitians died.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Wilson|first1=Colin|last2=Wilson|first2=Damon|title=An End To Murder: Human beings have always been cruel, savage and murderous. Is all that about to change?|date=2015}}</ref> In the process, Dessalines became arguably the most successful military commander in the struggle against Napoleonic France.<ref>Christer Petley, ''White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of REvolution'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 182.</ref> |

|||

[[Boniface Alexandre]] assumed interim authority. In February 2006, following [[Haitian general election, 2006|elections]] marked by uncertainties and popular demonstrations, [[René Préval]], close to Aristide and former president of the Republic of Haiti between 1995 and 2000, was elected. |

|||

===Independent Haiti=== |

|||

[[Image:Palaisnationalhg9.jpg|right|thumb|270px|Presidential Palace in Port-au-Prince]] |

|||

====First Empire (1804–1806)==== |

|||

The government of Haiti is a [[presidential system|presidential]] [[republic]], pluriform multiparty system wherein the [[President of Haiti]] is [[head of state]] directly elected by popular [[elections in Haiti|elections]]. The Prime Minister acts as [[head of government]] and is appointed by the President from the majority party in the National Assembly. [[Executive power]] is exercised by the President and Prime Minister who together constitute the government. |

|||

{{main|First Empire of Haiti|1804 Haiti massacre}} |

|||

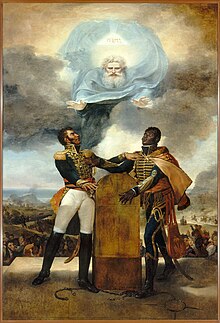

[[File:Le Serment des Ancêtres, 1823.jpg|thumb|Pétion and Dessalines swearing allegiance to each other before God; painting by [[Guillaume Guillon-Lethière|Guillon-Lethière]]]] |

|||

The independence of Saint-Domingue was proclaimed under the native name 'Haiti' by [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] on 1 January 1804 in [[Gonaïves]]<ref name="autogenerated2">{{cite web|url=http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/dessalines.htm |title="A Brief History of Dessalines", 1825 Missionary Journal |publisher=Webster University |access-date=24 July 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051228150910/http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/dessalines.htm |archive-date=28 December 2005 }}</ref><ref name="Bradt209">Clammer, Paul (2016), ''Bradt Travel Guide – Haiti'', p. 209.</ref> and he was proclaimed "Emperor for Life" as Emperor Jacques I by his troops.<ref>Constitution of Haiti [{{sic}}] ''New-York Evening Post'' 15 July 1805.</ref> Dessalines at first offered protection to the white planters and others.<ref>{{cite book|title=Monthly Magazine and British Register|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YVEoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA335|volume=XLVIII|year=1819|publisher=R. Phillips|page=335}}</ref> However, once in power, he ordered the [[1804 Haiti Massacre|genocide]] of nearly all the remaining white men, women, children; between January and April 1804, 3,000 to 5,000 whites were killed, including those who had been friendly and sympathetic to the black population.<ref name="Davies2008">{{cite book|last=Boyce Davies |first= Carole |title=Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. A-C. Volume 1|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mb6SDKfWftYC&pg=PA380|year=2008|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1-85109-700-5|page=380}}</ref> Only [[1804 Haiti massacre#Aftermath|three categories of white people]] were selected out as exceptions and spared: [[Polish Haitian|Polish]] soldiers, the majority of whom had deserted from the French army and fought alongside the Haitian rebels; the small group of [[German Haitian|German]] colonists invited to the [[Nord-Ouest (department)|north-west region]]; and a group of [[Doctor of Medicine|medical doctors]] and professionals.<ref>{{cite book|last=Popkin |first= Jeremy D. |title=Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VSeLGtVm0iIC&pg=PA363|access-date=20 June 2017|date=15 February 2010|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-67585-5|pages=137}}</ref> Reportedly, people with connections to officers in the Haitian army were also spared, as well as the women who agreed to marry non-white men.<ref>{{cite book|last=Popkin |first= Jeremy D. |title=The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=03XSP22p3kgC|access-date=20 June 2017|date=11 February 2011|publisher=University of Alabama Press|isbn=978-0-8173-1732-4|pages=322}}</ref> |

|||

[[Legislative power]] is vested in both the [[government]] and the two chambers of the [[National Assembly of Haiti]]. The government is organized [[unitary state|unitarily]], thus the [[central government]] ''delegates'' powers to the departments without a constitutional need for consent. The current structure of Haiti's political system was set forth in the [[Constitution of Haiti]] on 29 March 1987. The current president is [[René Préval]]. |

|||

Fearful of the potential impact the slave rebellion could have in the [[slave states]], U.S. President [[Thomas Jefferson]] refused to recognize the new republic. The Southern politicians who were a powerful voting bloc in the American Congress prevented U.S. recognition for decades until they withdrew in 1861 to form the [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/haitian-rev|title=The United States and the Haitian Revolution, 1791–1804|website=history.state.gov|language=en|access-date=7 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

The [[United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti]] (also known as MINUSTAH) has been in the country since 2004. |

|||

The revolution led to a wave of emigration.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/topic.cfm;jsessionid=f8303469141230638453792?migration=5&topic=2&bhcp=1 |title=From Saint-Domingue to Louisiana, The African-American Migration Experience |publisher=Inmotionaame.org |access-date=24 July 2013 |archive-date=25 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225063309/http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/topic.cfm;jsessionid=f8303469141230638453792?migration=5&topic=2&bhcp=1 |url-status=dead }}</ref> In 1809, 9,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue, both white planters and people of color, settled ''en masse'' in [[New Orleans]], doubling the city's population, having been expelled from their initial refuge in Cuba by Spanish authorities.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thenation.com/article/congo-square-colonial-new-orleans?page=0,1|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180914132009/http://www.thenation.com/article/congo-square-colonial-new-orleans?page=0,1|url-status=dead|archive-date=14 September 2018|title=In Congo Square: Colonial New Orleans |publisher=Thenation.com |date=10 December 2008 |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref> In addition, the newly arrived enslaved persons added to the city's African population.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ccet.louisiana.edu/tourism/cultural/The_People/haitian.html |title=Haitians |publisher=Center for Cultural & Eco-Tourism, University of Louisiana |access-date=24 July 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Haitian politics have been contentious. Most Haitians are aware of Haiti's history as the only country in the Western Hemisphere to undergo a successful [[Haitian Revolution|slave revolution]]. On the other hand, the long history of [[oppression]] by dictators, including [[François Duvalier]], has markedly affected the nation. [[France]] and the [[United States]] have repeatedly intervened in Haitian politics since the country's founding, sometimes at the request of one party or another. People's awareness of the threat of such intervention also permeates national life. |

|||