Friedrich the fair

Friedrich the Beautiful (* 1289 in Vienna ; † January 13, 1330 in Gutenstein ) from the noble family of the Habsburgs was the Roman-German king from 1314 .

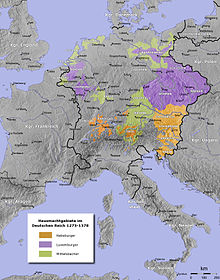

After the death of Emperor Henry VII in 1313, two kings were elected and crowned in the Roman-German Empire , the Wittelsbacher Ludwig the Bavarian and the Habsburg Frederick, as the votes of the electors were divided. Decades before the unambiguous rules of the Golden Bull were bitterly debated over the legitimacy of the Roman election. Armed conflicts in the Battle of Mühldorf in 1322 led to a preliminary decision for the Wittelsbach side. Friedrich was imprisoned for three years. Conflicts with the curia and with Friedrich's brothers forced Ludwig to settle. The Munich Treaty of September 1325 between Ludwig and Friedrich established a constitutional construct that was unique in medieval imperial history with equal dual power. From then on, Friedrich only played a secondary role in the empire, while Ludwig achieved the imperial crown.

Friedrich now emerged particularly in the field of foundations, which he used as a means of legitimizing and stabilizing rule. Under him, the focus shifted from the Habsburg homeland in the west to the new duchies in the east. At the same time it paved the way for Vienna as a Habsburg residence. Friedrich was only given the nickname “the beautiful” in the 16th century. The voluntary return of the Habsburgs to the captivity of Ludwig of Bavaria was often artistically processed in the 19th century.

Life

Origin and early years

Friedrich belonged to the Habsburg family . The noble family can be traced back to a Guntram who lived around the middle of the 10th century . Guntram's grandchildren included Radbot and Bishop Werner von Straßburg . One of the two is said to have built the Habichtsburg / Habsburg around 1020/30 . The Habsburg possession was based on the allod between the Reuss and Aare with the eponymous castle and monastery bailiwicks in northern Switzerland, the Black Forest and Alsace. When the Zähringer died out in 1218, the Habsburgs became the leading family between the Upper Rhine and the Alps.

Friedrich was one of the grandsons of Rudolf von Habsburg , the first Roman-German king from the House of Habsburg. In 1282 belehnte Rudolf his sons Albrecht I and Rudolf II. With the countries of Austria , of Styria , Carniola and the Windic March . The kingdom of the home fallen fief Rudolf was awarded as King to his family members. Seven years later, Friedrich was born as the second son of the Duke and later King Albrecht I and Elisabeth . The marriage resulted in a total of 21 children. Friedrich's mother came from the Counts of Tyrol - Gorizia . He was the first Habsburg to be given the name Friedrich, which is typical of the Babenbergs . With this guiding name Friedrich was placed in the tradition of the Babenberg dukes. This was intended to promote the beginning integration of the dynasty in the eastern duchies, with which the Habsburgs had been enfeoffed in 1282. Friedrich, his older brother Rudolf and younger brother Leopold was on 21 November 1298 in Nuremberg by Albrecht entire hand with Austria, Styria, Carniola, the Windic March and Pordenone invested. Gerald Schwedler was able to show that for decades the Habsburgs mainly oriented themselves towards the legal principle of total hand lending. The multiple security model was intended to prevent conflicts between the Habsburg sons and the extinction of the family in the male line.

According to a source from the Augustinian canons of Dießen from 1365, Friedrich and his later rival Ludwig spent part of their childhood together in Vienna at the court of Duke Albrecht I of Austria. They were cousins because Ludwig's mother Mechthild was a granddaughter of Rudolf I von Habsburg and Friedrich's mother Elisabeth was a granddaughter of Wittelsbacher Otto II. In Vienna, Friedrich and Ludwig are said to have learned the litterae , that is, were taught in Latin. However, there is no other evidence for Ludwig and Friedrich's knowledge of Latin.

On January 17, 1303, Friedrich took an active part for the first time by privileging the Swabian monastery in Zwiefalten . From this it can be concluded that he had received government powers for the western territories from his father. However, he did not rule independently, as in the following years he mostly stayed in the vicinity of his father. Friedrich's older brother Rudolf was made King of Bohemia in October 1306 , but died in 1307. In 1306 Friedrich took over the rule of the duchies of Austria and Styria from his older brother . In addition to the confirmation of privileges, his tasks included legal transactions such as the granting of Graz city rights to Voitsberg . Friedrich's father, King Albrecht, fell victim to an assassination attempt by his nephew Johann Parricida on May 1, 1308 . On the same day, Johann had repeatedly asked Albrecht, in vain, to recognize his inheritance claims and to assign him his own domain.

After the father's death, Friedrich was the eldest of the surviving sons. The tasks that the heirs faced included asserting the Habsburg claims to the Bohemian royal crown, a possible candidacy of the eldest son in the upcoming election of the Roman-German king and the prosecution of her father's murderers. Friedrich laid claim to his father's succession, but the electors agreed on Count Heinrich from Luxembourg . Leopold took over the pursuit of the regicide, while Friedrich concentrated on the struggle for the Bohemian inheritance in the east. In Moravia Friedrich moved with an army one, but in Bohemia Habsburg rule collapsed soon. The estates elected the Meinhardin Duke Heinrich of Carinthia as king. Friedrich advanced as far as Prague, but could not bring about a change with his army. Therefore, in the Znojmo Treaty of August 14, 1308, he renounced the Kingdom of Bohemia and received 45,000 marks pfennigs from Heinrich von Kärnten.

In order to come to an understanding with the new king, Friedrich traveled to Speyer for the court day in the summer of 1309. The negotiations were extremely difficult, to which Frederick's pompous appearance with a large entourage may have contributed. When Friedrich was about to leave, an agreement was reached on September 17, 1309. Friedrich renounced the Bohemian crown and promised the king support for the acquisition of Bohemia through army orders and a loan. He also promised Heinrich army succession against Friedrich the free and for the planned Rome train . In return, Heinrich Friedrich and his brothers gave the total mortgage lending for all their possessions. Johann and his like-minded comrades Rudolf von Balm, Rudolf von Wart and Walter von Eschenbach, as the murderers of King Albrecht, were ostracized by the king as a majesty criminal. Their estate was awarded to the Habsburgs. Heinrich also agreed to the transfer of the remains of Albrecht I from the Cistercian monastery Wettingen to the royal burial place in Speyer Cathedral .

A year later, Friedrich fell so seriously ill that many thought he was dead, so they showed him around to prove that he was still alive.

Dispute over Lower Bavaria from 1313

Friedrich and Ludwig rivaled tried to expand their influence in Lower Bavaria. From 1312 Ludwig was guardian of the underage dukes Heinrich XIV. , Heinrich XV. and Otto IV. The Lower Bavarian ducal widows Agnes and Judith, on the other hand, wanted to transfer the guardianship of their sons to the Habsburgs. In negotiations in the Aldersbach monastery and in Landau, the two opponents could not find a solution. Ludwig emerged victorious from the so-called battle of Gammelsdorf west of Landshut in November 1313. The assessment of events in historical science fluctuates between "decisive battle" and mere "skirmish".

A contract that Friedrich and Ludwig concluded in Salzburg on April 17, 1314 ended the conflict. They slept together in one bed and thus, according to Johann von Viktring's report, made clear the “complete settlement and settlement of all open disputes”. This ritual was widespread and is widely attested. Friedrich, who did not take part in the lost battle, was ousted from Lower Bavaria by the defeat. There, Ludwig was able to secure access to the rule. At the same time he strengthened his position in the south-east of the empire. For Bernhard Lübbers , Ludwig's victory over Friedrich represented a “milestone” on the way to the Roman-German throne.

Marriage to Isabella of Aragón in 1313

As Duke of Austria and Styria, Friedrich probably first contacted the Crown Aragón in 1311 . With the Aragonese king Jayme II / Jacob II he negotiated a marriage with his third daughter Isabella of Aragón , because he could not find a suitable wife in the empire. The Habsburgs were already related to all of the great princely families. The Aragonese marriage project at that time was less geared towards the Roman-German monarchy than towards gaining prestige in a society with a sense of rank; it was intended to increase political networking beyond the borders of the empire. This in turn gave a wide range of leeway to consolidate and expand the Habsburg position of power. On October 14, 1313, Isabella and Friedrich were married by the Archbishop of Tarragona in the royal castle in Barcelona . The wedding ceremony took place on January 31, 1314 in Judenburg . The marriage had three children: Friedrich II, born in 1316, who died just a few days after his birth, and the daughters Elisabeth (1317–1336) and Anna (1318–1342). Isabella appeared quite independently, which shows, for example, the use of her own seal. Based on the documentary tradition and the letters, Stefanie Dick came to the conclusion that Isabella and Friedrich acted as a couple, especially in connection with political networks.

Controversy for the throne (1314-1325)

Outbreak of conflict

In August 1313, Emperor Henry VII died of a severe attack of malaria while on his way to Italy. After Heinrich's death, given their house power and membership of a royal family, Friedrich the Fair and Johann , Heinrich's son, could be the successors. Johann was King of Bohemia from the late summer of 1310.

In the spring of 1314, Friedrich was able to unite the votes of three electors behind him with lavish payments and numerous favors: Count Palatine Rudolf of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, Margrave Waldemar of Brandenburg and Archbishop Heinrich of Cologne from the family of the Counts of Virneburg said their support to. Friedrich and the Archbishop of Cologne strengthened their alliance with a marriage alliance: Friedrich's younger brother Heinrich was married to a niece of the Archbishop. Johann's supporters were his paternal uncle, Archbishop Balduin von Trier , who was to develop into one of the most important Reich politicians of the 14th century, and the Archbishop of Mainz , Peter von Aspelt , who had already campaigned for the election of Henry VII. After more than a year, the situation remained confused. The Archbishop of Mainz and Trier finally persuaded Johann von Böhmen to renounce his candidacy when it became foreseeable that it would be hopeless. You now spoke out in favor of the Wittelsbacher Ludwig as a compromise candidate. Ludwig only had a comparatively narrow power base, because he had to share the Palatinate Countess near the Rhine and the Duchy of Upper Bavaria with his older brother Rudolf as co-regent, but he had gained fame throughout the empire through his victory at Gammelsdorf and was therefore in the The electors' field of vision shifted. For the Luxembourg parliamentary group under the leadership of the Archbishop of Trier, Ludwig was the ideal candidate precisely because of his limited domestic power, because he could not endanger the position of the electors, but had the ambition to oppose the Habsburgs. In addition, Ludwig was able to secure the vote of Waldemar of Brandenburg. The Habsburgs did not give up, however.

Both candidates for the throne went to Frankfurt am Main, the traditional place of election. However, the city's citizens refused entry to both camps. On October 19, 1314, Friedrich in Sachsenhausen on the left bank of the Main was made king by Duke Heinrich of Carinthia, Count Palatine Rudolf bei Rhein and Duke Rudolf von Sachsen-Wittenberg . A day later, Ludwig was elected on the right side of the Main by the Archbishops of Trier and Mainz, King John of Bohemia, Margrave Waldemar of Brandenburg and Duke Johann II of Saxony-Lauenburg . Thus the majority of the electors stood on Ludwig's side. On November 25, 1314, Friedrich was crowned Roman-German King in Bonn Minster by Archbishop Heinrich von Virneburg, while Ludwig's coronation was performed on the same day in Aachen, the traditional coronation site, by the Archbishop of Mainz. According to the documents, both kings viewed the day of their coronation as a constitutive event of their rulership. Friedrich was in possession of the imperial insignia and also had the correct coronator ("King Crown"), the Archbishop of Cologne, on his side. The use of the insignia at the royal coronation was less important than the power of disposal over them, which identified Friedrich as the legitimate king. Ludwig, for his part, had the insignia reproduced.

However, contrary to custom, Friedrich was crowned in Bonn and not in the prescribed place of Aachen. The citizens of Aachen had prevented him from entering their walls. As Manfred Groten has shown, this was primarily a consequence of the regional balance of power, the conflict between the Rhenish count families and the Archbishop of Cologne, Heinrich. In Cologne, too, the archbishop had to reckon with resistance from the citizens. From 1314 he stayed mainly in Bonn and on the Godesburg . With its magnificent collegiate church, Bonn offered the conditions for a worthy ceremony. For Groten, Friedrich's coronation there was a "key event in Rhenish history with far-reaching consequences".

Frederick's wife Isabella von Aragón was crowned Roman-German queen by the Archbishop of Cologne on a court day during Pentecost on May 11, 1315 in Basel. The imperial treasure with the crown was also shown to the people. Despite the coronation, Friedrich did not renounce his ducal power in Austria and did not make a clear separation of the administrative areas.

Course of the clashes

Both parties to the dispute made use of symbolic acts of communication in order to present their own uprising as legitimate and to discredit that of the other side. According to the Austrian historiographer Johann von Viktring, Bonn was a worthy place for a royal coronation. Friedrich not only gathered influential supporters around him and held the title of king, but also held lavish court days. In order to prove the legitimacy of Friedrich's coronation in Bonn, Johann performed all the coronations known to him since the time of the East Franconian Carolingians that had not taken place in the traditional location. The anti-Habsburg author of Chronica Ludovici, on the other hand, reports that Friedrich was elected on a field in a place called 'Pung' near Bonn and was proclaimed king while standing on a barrel. Hardly 30 people were present. Furthermore, Friedrich fell into the barrel at this unworthy elevation.

Both sides tried to get the Pope to recognize their kingship. Friedrich intensified his correspondence with his father-in-law, who had good relations with the Curia. In order to consolidate his position in Italy, Friedrich also pursued an active Italian policy, in which Count Heinrich III played a key role . von Gorizia as well as father and son Ulrich I. and Ulrich II. von Walsee -Graz supported. In 1316 Frederick made an alliance with King Robert of Naples . His sister Catherine was married to Charles of Calabria , Roberts' heir to the throne. Pope John XXII, elected in 1316 . held back, however, with a clear statement for one of the two kings. In 1314 nine electors participated in the election; At that time it was not yet binding who was legally entitled to vote, and the majority principle in royal elections did not yet exist. Hence, an armed conflict was inevitable. Between 1314 and 1322, however, none of the crowned sought a decision in a major battle. His previous military failures gave Frederick the Fair cause for restraint: after losing to Ludwig at Gammelsdorf, the Habsburgs suffered a defeat against the Confederation on November 15, 1315 in the Battle of Morgarten . Ludwig did not take advantage of this situation, however, he also hesitated. Smaller skirmishes took place in 1315 near Speyer and Buchloe , 1316 near Esslingen , 1319 near Mühldorf and 1320 near Strasbourg, but initially there was no major battle.

Imprisonment of Frederick in 1322 and Agreement in 1325

In September 1322 the Habsburgs wanted to bring about a military decision. Friedrich advanced from the east, his brother Leopold from the west via Swabia. The armies were to be united at Mühldorf am Inn . However, Ludwig arrived before Leopold and defeated Friedrich in the battle of Mühldorf . At the time of the defeat, Leopold's armed forces stood west of Munich. It withdrew towards Alsace. Friedrich was taken prisoner. Ludwig is said to have welcomed his Habsburg relatives with the words: "Cousin, I never saw you as much as I do today." The pro-Habsburg Matthias von Neuchâtel reports that the two kings behaved differently. Friedrich had clearly identified himself as king through the crown and banner, while Ludwig, on the other hand, had disguised himself in a group of knights dressed in the same way with white and blue tunics for fear for his life. Friedrich lost the battle because he was not adequately supported by his troops. He let himself be captured because a brave warrior would not flee cowardly, but would fight on to the end. Ludwig, on the other hand, was, as far as is known, not praised by his followers for bravery and fighting courage.

In the late Middle Ages it seldom happened that a king was captured in open battle. The burgrave Friedrich IV of Nuremberg and several other fighters were involved in Friedrich's capture. They were probably primarily concerned with ransom, so they were interested in Friedrich's survival. Ludwig's victory was not perfect. Friedrich was alive, and despite his capture, the outcome did not appear to be a clear judgment from God . Thanks to Leopold's army, the Habsburgs were still able to act in the empire. Ludwig left the battlefield quickly; he refrained from making his victory evident by the symbolic act of lingering at the battlefield, as is often the case.

Ludwig held Friedrich in custody for three years at Trausnitz Castle in Upper Palatinate . According to the Fürstenfeld Chronicle, Friedrich was kept there without chains or leg irons. This corresponded to late medieval practice; they shied away from humiliating royal prisoners so obviously. Friedrich was allowed to keep his servants, but had to bear the cost of his meals himself. A visit by Ludwig to the prisoner is not documented.

The Wittelsbacher's rule was by no means secured with his victory, because Friedrich's brothers continued to oppose him. At the same time, his conflict with the Pope came to a head in October 1323, when Ludwig tried to assert his claims to royal rule in Italy as well. Pope John XXII. then opened the trial against Ludwig on October 8, 1323. He declared his election invalid and asked him to give up the throne within three months. When the Wittelsbacher did not comply with this demand, he was excommunicated by Johannes on March 23, 1324. In the empire, Friedrich's brothers and their followers continued the fight.

In this explosive situation, Ludwig decided to settle with Friedrich. On March 13, 1325, the two rivals to the throne concluded an agreement, the " Trausnitzer Atonement ". Friedrich had to renounce the title of king and recognize Ludwig as king, hand over the imperial property acquired during the throne dispute and make up for the feudal tribute for his legal title. Friedrich also promised this for his brothers, whom he thus committed to the Wittelsbacher. If the brothers refused to give their consent, he undertook to return to detention. He also promised the Wittelsbacher unlimited help, including against the Pope. He was released from custody for this without paying a ransom. The agreement was secured with a promise of engagement: Friedrich's daughter Elisabeth was to be married to Ludwig's son, Duke Stephan .

The aim of the Trausnitz Atonement was not to humiliate and subjugate Frederick the Beautiful, but to restore Ludwig's political capacity to act by establishing a consensus. However, Friedrich's younger brothers refused to accept the agreement, after which he returned to captivity.

Dual rule (1325-1327)

Half a year after the Trausnitz Atonement, Ludwig the Bavarian and Friedrich the Beautiful agreed on September 5, 1325 in the Munich Treaty on a joint and equal rule. Friedrich was recognized as co-king, and his brother Leopold was to become the imperial vicariate in Italy. Ludwig wanted to bind Friedrich to himself and thereby win over the Habsburg family. The dual kingship established in this way is a unique phenomenon in medieval constitutional history. Ancient Greek or Roman models are probably out of the question. The Munich Treaty is judged differently in research. Michael Menzel calls it "an amazing testimony of constructive awareness". For Karl-Friedrich Krieger it is a “strange” contract. Marie-Luise Heckmann believes that the two kings wanted to "manage the Roman kingship by mutual agreement and acquire the empire together for the Wittelsbacher". The agreement was agreed in writing and reinforced with ritual acts. On Easter, the contracting parties demonstrated their agreement ritually by receiving the Lord's Supper and kissing peace. Since the early Middle Ages, peace and friendship have been established with a common meal. Friedrich and Ludwig listened to mass together and received communion in the form of a host shared between them . With this, Friedrich demonstratively expressed his partisanship, because he ignored the Wittelsbacher's excommunication, which forbade him to take communion.

In the past, there was no possibility of orientation for the processes of public representation of dual power. According to the treaty, the two kings should act with "one other than one person." Unity and fraternity formed the basis for the public representation of dual power. Friedrich and Ludwig referred to each other as king, ate food together and even shared a bed. Both intended to use the title of Roman king and Augustus by mutual agreement and together and to address the other as brother. The Munich Treaty stated that the seals and the letters in the romanization should be adapted. The plan of a common seal was not realized, however, everyone continued to use their own seal. Whoever moved to Italy should have full authority. Questions that were still important in the controversy for the throne, such as the correct place of coronation, the coronator responsible for it and the insignia, were not discussed.

During the years of dual rule, the two kings continued to demonstrate their consensus politically and symbolically. In a large number of files they emphasized their mutual trust and unanimity. However, the double kingship lasted only a short time. According to Marie-Luise Heckmann, it failed because Friedrich and Ludwig did not agree on the dynastic protection. According to Claudia Garnier , the Munich Treaty could not work because there were no practical instructions for action for equal dual power and this deficiency was concealed by general and unclear provisions. The staging of dual power could not fall back on role models, as the contemporary Peter von Zittau recognized. Already at the first meeting of the kings in Ulm in January 1326 there were disputes of interpretation. In a treaty concluded in Ulm, Ludwig declared that he was ready to renounce the throne if Friedrich were recognized by the Pope as king. The Pope had to refuse, however, because Friedrich had publicly and symbolically maintained contact with an excommunicated person and even formed an alliance. Due to his apparent willingness to give up, Ludwig was able to present himself in the empire as capable of compromises and the Pope as irreconcilable. In this way he brought the princes in the empire behind him and created room for maneuver for his undertakings in Italy.

The two kings met for the last time in Innsbruck at the end of 1326. This apparently led to tensions that may have affected the implementation of the common rule. Ludwig ended the dual kingship in February 1327 by making King John of Bohemia vicar general instead of Frederick . Ludwig's coronation as emperor in 1328 meant an increase in rank that made the concept of equal rights of the Munich Treaty completely obsolete. Although Frederick still chartered several times before his death, he no longer intervened in great imperial politics and withdrew to the Duchy of Austria. His attempts at Pope John XXII. to achieve recognition of his kingship was unsuccessful.

Court and rulership practice

Until well into the 14th century, medieval royal rule in the empire was exercised through outpatient government practice. There was neither a capital nor a permanent residence. Dominion was based on presence. The development of Vienna into a Habsburg royal residence, which began under Friedrich the Beautiful, was an innovation, the importance of which Günther Hödl first emphasized in 1970. However, Friedrich was only able to pursue his residency plans for Vienna after his release from captivity. According to Hödl, the Habsburgs were less “planless and inactivity” than “lack of opportunity to fully devote themselves to the city”, the decisive reason why the planned expansion of Vienna into a Habsburg residence was not made until Friedrich's younger brother Albrecht II in the 1330s and operated in 1340s. The addition in the coin ordinance first issued by King Rudolf in 1277 goes back to Friedrich, stating that the coin may be renewed “in chain instead of the whole of Austria, only in Vienna, which is the forerunner and mainstay of the same country”. According to Christian Lackner , the founding of the Augustinian Hermit Monastery on March 15, 1327 was another sign that Friedrich viewed Vienna as his preferred residence. Hödl emphasized the importance of the monastery complex located directly next to the Hofburg for Vienna's residence. The extraordinary position of the city is also evident in the itinerary . From March to October 1318, Friedrich stayed mainly in Vienna.

Since the 12th century the court developed into a central institution of royal and princely power. According to Werner Rosener's definition, it can be understood as a complex system of domination and society . The most important part of the court was the chancellery . In the 13th and 14th centuries, significantly more documents were issued than before, and the written form increased significantly. Friedrich had a single "royal-ducal chancellery", in which the competencies merged. The head of the chancellery and court chancellor was temporarily (1320/21 and 1326) Johann von Zurich, who was appointed bishop of Strasbourg in 1306 . As king, Frederick wrote mainly in Latin; in the documents that he wrote as Duke, however, he preferred the German language. Connections to Bologna were found in both Ludwig and Friedrich's offices. Both firms were familiar with the Italian letter teaching .

On the basis of the document findings and itineraries, Christian Lackner shows that Friedrich often stayed in the eastern rulers of the Habsburgs. The investigation of the donor activity gives a similar finding. In April 1316, Friedrich had a letter of donor issued for the Mauerbach monastery . During his time as Duke of Austria and Styria, Friedrich and his brothers had already made plans to build the monastery for a prior and twelve monks, including a poor house for 17 needy people. The clergy were supposed to celebrate the anniversary with masses and other liturgical acts for the Habsburg kings Rudolf and Albrecht, for Albrecht's wife Elisabeth, for Friedrich's deceased brother and for himself. Although the Habsburg monastery in Königsfelden , located in the western homeland , which Friedrich's mother had donated in 1309 at the place where her husband Albrecht died, was also favored by Friedrich several times, but Claudia Moddelmog came to the conclusion in her investigation that the Königsfeld Foundation for the representation of rulership was not was particularly suitable. The construction of the complex was not yet completed, the Königsfeld nuns lived in a strict enclosure and the monastery only had one female burial place. Frederick therefore showed little interest in Königsfelden and barely incorporated this monastery into his representation of power. The last foundation outside the Austrian territories was made by Friedrich in Treviso in 1318 . In the period that followed, his well-known foundation activities were limited to the eastern territory of the Habsburgs. Sums of money were awarded by the foundations so that an eternal mass could be celebrated on the day of Friedrich's death during Friedrich's lifetime and on the day of his own death after his death.

In terms of personnel, in contrast to his father and older brother, Friedrich no longer exclusively surrounded himself with Alemanni. He increasingly resorted to "Austrians" as advisors and envoys. The Commander of the Teutonic Order Konrad von Verbehang and Otto, the abbot of the Styrian Benedictine monastery of St. Lambrecht , took on important tasks in the duke's marriage negotiations with the Aragonese court. The oldest known evidence of the term "House of Austria" (domus Austriae) , which was used to designate the entire Habsburg complex of territories , also dates back to the time of Friedrich .

For Styria, Annelies Redik stated that Friedrich did not enter his duchy in six of the 23 years of his Styrian principality. Because of the war and imprisonment, he is not at all detectable there for the period from September 1321 to March 1326. Until 1322, the focus of his relationship with the Duchy of Styria was on realizing the goals of the Habsburg imperial policy. He needed human and financial resources from Styria for his fight against the Wittelsbacher. This becomes clear in numerous pledges and service obligations. After settling with Ludwig in 1325, Friedrich stayed more in his sovereign principality and, as sovereign, undertook numerous acts such as donations, privileges and foundations. In the last months of his life he stayed in Graz for weeks . In addition to Graz, Judenburg was Friedrich's preferred place of residence in Styria.

Robert Suckale spoke in a study published in 1993 of a targeted "court art of Ludwig of Bavaria". Suckale saw a style-forming artistic center in the courtyard. In 2017, Christian Freilang, on the other hand, was unable to prove a specific or detailed design language for either Ludwig or Friedrich. A specific program to leave until much later in France under King Charles V show.

Last years and death

On February 28, 1326 Friedrich lost his brother Leopold. Less than a year later, his brother Heinrich of Austria also died . During this time Friedrich's wife became seriously ill, she was almost completely blind due to a brain tumor. The death of his brothers and the illness of his wife were probably the reason for him to draw up his will. In June 1327, at the age of 38, he issued a comprehensive foundation diploma with his will in Vienna. It is the oldest surviving will of an Austrian prince. With the foundation document, the king wanted to secure the memory of himself and that of his ancestors and descendants. A total of more than 80 places of worship were furnished with 4,280 pounds of Viennese pfennigs and 1,636 marks of silver. The sum should be paid through the toll in Enns. In return, the spiritual communities had to celebrate eternal masses and anniversaries. In the duchies of Austria and Styria, 48 monasteries were given legacies between 40 and 200 pounds pfennigs.

In 1328 Frederick's itinerary was almost entirely restricted to the Duchy of Austria. It can be found in Wels (January 15), Vienna, Krems (May 20), Bruck an der Leitha (September 21) and Laab (November 25). Only seven notarizations are attested.

Friedrich died quite lonely at the age of 41 on January 13, 1330 at Gutenstein Castle near Wiener Neustadt in Lower Austria . A stroke was suspected in research. But there was also a suspicion of poisoning. Friedrich was buried in the Carthusian monastery in Mauerbach, which he founded . According to Heinrich Koller , in the first half of the 14th century the burial places of the Habsburgs lost the task of "indicating political orientation". At the instigation of the family, Friedrich's father Albrecht was buried in the tomb of Speyer and thus at the most important burial place of the Roman-German monarchy. Albrecht's sons, on the other hand, had made the provision for their souls more important through burial in their personal foundations, where they could organize the memorial system. Friedrich's grave was the first of a ruling Habsburg dynasty in the east. However, no funeral tradition developed in the churches founded by Friedrich the Handsome, Duke Otto and Albrecht II. Instructions from the king for his burial place or the procedures for the funeral are not known. The burial proceeded without any particular display of pomp. His wife Isabella died six months later on July 12th.

According to Michael Borgolte , the historical memory of the resting places of the descendants of King Frederick was stronger than the liturgical visualization of the grave by the monks. In 1514 the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I came to Mauerbach and asked about his ancestor's grave, but the monks were already unable to show him. Maximilian then had investigations carried out, and after a three-day search, two coffins were found that were identified as those of Friedrich and his daughter. Seven years after the monastery was dissolved by Emperor Joseph II , Friedrich's remains were transferred to St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna in 1789 . They are kept in the ducal crypt there to this day.

Nickname 'the beautiful'

Even in the Middle Ages, Friedrich was not counted as the third of his name, but as Friedrich I, according to Thomas Ebendorfer . His nickname 'the beautiful' (Latin Pulcher) is not contemporary, but dates from the 16th century. This is how Wolfgang Lazius referred to him in 1564 and Johannes Cuspinian in 1601. The nickname probably goes back to the Chronicle of Königsfelden. As early as the end of the 14th century, Friedrich was described as "beautiful and mild even princely" in the anonymous chronicle of 95 lords . From the statement in the Königsfeld Chronicle that Friedrich von Habsburg was “a proud and beautiful man”, the nickname “the beautiful” developed. A fantasy portrait by Antoni Boys from the 16th century shows him with the inscription "Fridericus Pulcher Rom (anorum) rex". Alphons Lhotsky's suggestion to abandon the nickname has not caught on in research. Other nicknames such as Fortis, Pius, Verax, Modestus or Affabilis come from the Baroque .

effect

Late medieval judgments

The late medieval Austrian chronicle of the country, the chronicle of the 95 rulers , had difficulties in properly classifying Friedrich in the history of the country. Its structure is based on a threefold chronological run through the history of the pope, the emperor and the state of Austria. According to Christian Lackner, Friedrich found “no real place” in the history work in his dual role as duke and king . One of the most important historiographical sources is the imperial chronicle of Matthias von Neuenburg , who was active in the diocese administration in Basel in 1327 and in Strasbourg from 1329. Ludwig is twice dubbed “the Bavarian” by Matthias, who is friendly to the Habsburgs, while Friedrich is once called “King of the Romans”. The Chronica Ludovici , which probably originated to a large extent in 1341/42 in the Augustinian canons of Ranshofen and was then supplemented with supplements by 1347, is prob-Bavarian and takes a negative and polemical stance against the Habsburgs. According to this source, Friedrich and Ludwig negotiated by no means about a permanent dual kingship, but about the renunciation of Friedrich's claims. Ludwig only trusted in the binding power of the Eucharist received together. Friedrich violated the agreement by maintaining the title of king. For this he received the just punishment in 1330, because he was murdered by his own servants (a pediculis) . The detailed descriptions of trust-building gestures in this context made the subsequent betrayal of Frederick all the more vivid. The Cistercian abbot Johann von Viktring made use of similar presentation and argumentation models for the Habsburg side. He wrote his chronicle, the Liber certarum historiarum , at the suggestion of Duke Albrechts II. In it, Frederick is acquitted of breach of the oath and contract with Ludwig. Rather, the breach of the agreements is blamed on the Wittelsbacher.

Friedrich's efforts to be included in the prayer of the donated communities were successful. This is proven by various memorial books. However, in numerous books of the dead, only the name of Friedrich around the day of his death was cited, so that the specific course of the memorial ceremony remains unclear. However, a document issued in 1331 from the Diocese of Constance documents a concrete implementation of Friedrich's foundation conditions. The clerics there committed themselves and their successors to the observance of the jointly decided Anniversar celebration. In 1498 the Konstanz canons copied the document from 1331 into their liturgical manuscript for compliance.

Artistic reception

Friedrich received little attention in posterity. He was often presented in relation to his opponent Ludwig. The representations made during his lifetime and shortly after his death show him as an idealized king and are hardly individual. The only contemporary illustration is the royal seal. A picture in the Innsbruck handwriting of the Chronicle of 95 Dominions shows him with a short beard in a middle age group. His depiction is embedded between Friedrich I and either his father Albrecht I or the first Habsburg king Rudolf I. A glass painting around 1370/80 from the Bartholomäus chapel in St. Stephan in Vienna shows him with a full beard.

The war between Friedrich and Ludwig was also reflected in art. A miniature in a Jewish manuscript from the Lake Constance area shows two knights with Habsburg and Bavarian coats of arms meeting directly on their horses. Sarit Shalev-Eyni limited this image to the battle of Mühldorf in 1322. According to Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck, however , the picture does not illustrate a specific event; rather, criticism is made of the unexplained conditions in the Lake Constance region for years. He justifies this with the little man above the frame of the two opponents, who does not aim with his exposed rear end at one of the two fighters, but at the space between them.

The reconciliation of the warring kings inspired several artists of the 19th century ( Joseph Wintergerst : Reconciliation of Ludwig of Bavaria with Friedrich the Beautiful 1816; Wilhelm Lindenschmit : Reconciliation of Ludwig of Bavaria with Friedrich the Beautiful 1835/36; Karl von Piloty : The release of Frederick the Beautiful from Austria from Trausnitz Castle by Ludwig the Bavarian around 1855/60; Sebastian Staudhamer : Reconciliation of Ludwig of Bavaria with Friedrich the Beautiful 1892). Trausnitz im Tal drew the attention of poets, artists and historians in the 19th century as the scene of imprisonment and reconciliation, as a place of unbreakable faithfulness to words and intimate friendship. The voluntary return of the Habsburgs to captivity met with a wide range of admiration and respect during this time, which was enthusiastic about the Middle Ages. Friedrich Schiller sang about it in his poem Deutsche Treue and celebrated Ludwig Uhland in a play. Friedrich's loyalty work also impressed the Bavarian King Ludwig I , who found him worthy of admission to the Walhalla , while he excluded his own ancestors as an unfaithful ruler from the circle of the "most praiseworthy" Germans. Friedrich the Beautiful was received in poems in the 19th century by Maximilian Fischel , Joseph von Hormayr and Ludwig August Frankl .

Research history

In the Protestant-Little German historiography of the 19th century, the late Middle Ages were considered to be an era of disintegration, as from the end of the Hohenstaufen the expansion of territories and the power of the princes over the power of the king increased steadily. The late medieval rulers were characterized as weak and the princes as selfish. This view of history remained prevalent even after 1945. Since the 1970s, medieval studies have turned more towards the late Middle Ages. Since then, the time of Frederick the Beautiful has been perceived less under the aspect of crisis-ridden developments, rather it is understood as an epoch of transitions, the “open” constitutional states and new approaches. For Michael Menzel (2012), concepts and drafts such as the idea of the double kingship are the characteristics of the years between 1273 and 1347. He sees this period as characterized by a fundamental “joy in designing”, by a “spirit of optimism”, but also by "The drying up of vigor", which is why this period of time appears "like a torso". According to Marie-Luise Heckmann, the rulership model of the double kingship "fell into a development phase of the constitution of the Holy Roman Empire, which is characterized by openness and a willingness to experiment".

The verdict on Friedrich was mostly negative because of his various diplomatic and military setbacks. He was the main focus of Austrian research. Alphons Lhotsky (1967) expressed himself critically in his History of Austria 1281-1358 : Friedrich was “not an equal successor to his father”. He had "seen from the standpoint of the dynasty" everything that was built up by the father "completely brought down". Friedrich's death marks an important turning point, because it marked the turn for the "Austrification" of the Habsburg dynasty around 1330. According to Günther Hödl (1988), Friedrich remained “dependent, politically inactive and without ideas”, especially after being imprisoned in Trausnitz. Even for Karl-Friedrich Krieger , who presented an overview of the Habsburg dynasty in 1994, Friedrich was not an “equal successor to his father”. Otherwise, Krieger did not want to accept Lhotsky's negative assessment. The assessment depends on the extent to which King Albrecht's building work is considered successful. The caesura made by Lhotsky was put into perspective by Alois Niederstätter (2001), since under Friedrich "the situation in Austria had changed". Annelies Redik confirmed Niederstätters judgment for Styria in a study published in 2010. She stated that the network of relationships between the Habsburg dynasty and the former Babenberg duchies became denser, especially in terms of personnel under Frederick.

On the occasion of the anniversary of the coronations of the two kings on November 25, 1314, Ludwig published a large number of publications in 2014, and in Regensburg the Bavarian state exhibition entitled We are emperors! dedicated. The scientific reception of Friedrich was rather restrained and locally limited. On the occasion of the 700th anniversary of his coronation, the interdisciplinary conference "Bonn 1314 - Coronation, War and Compromise" was held in Bonn in November 2014. This was intended to emphasize Friedrich's importance and at least to some extent relativize the one-sided focus of research on Ludwig. The contributions to the conference were published in 2017 by Matthias Becher and Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck in an anthology.

swell

- Regesta Habsburgica. Regesta of the Counts of Habsburg and the Dukes of Austria from the House of Habsburg. III. Department: The regests of the Dukes of Austria and Frederick the Fair as German King from 1314–1330. Edited by Lothar Gross, Innsbruck 1922–1924 ( digitized ).

- Annelies Redik (arrangement): Regesta of the Duchy of Styria . First volume: 1308–1319 . 1st delivery (1976). Part 2: Register tape for the 1st delivery (1985). Second volume, 1st part: 1320–1330 : 2nd part: Registers and directories (= sources on the historical regional studies of Styria. Vol. 6–8). Historical Provincial Commission for Styria, Graz 2008.

- Chronica Ludovici imperatoris quarti . In: Bavarian Chronicles of the XIVth Century , edited by Georg Leidinger ( MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 19), Hanover / Leipzig 1918, pp. 119-138 ( digitized version ).

- Johann von Viktring , Liber certarum historiarum , edited by Fedor Schneider ( MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum 36), Hanover / Leipzig 1909/10 (vol. 1: digitized , vol. 2: digitized ).

- Mathias von Neuenburg , Chronica , edited by Adolf Hofmeister ( MGH Scriptores rerum Germanicarum . Nova Series 4), Berlin 1924–1940 ( digitized version ).

literature

Representations

- Matthias Becher , Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314. Coronation, war and compromise. Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2017, ISBN 978-3-412-50546-2 ( limited preview on Google books ).

- Günther Hödl : Friedrich the beautiful (1314-30). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic-topographical handbook, Vol. 1: Dynasties and Courtyards (= Residence Research. Vol. 15). Thorbecke, Ostfildern 2003, ISBN 3-7995-4515-8 , pp. 292-295.

- Karl-Friedrich Krieger : The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd updated edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-17-018228-5 , pp. 110-127.

- Alphons Lhotsky : History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281–1358). Vol. 2: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century. Part 1: (1281–1358) revision of the history of Austria by Alfons Huber, vol. 2,1 (= publications of the commission for the history of Austria. Vol. 1). Böhlau, Vienna 1967, pp. 169–309.

- Michael Menzel : The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbook of German History . Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-608-60007-0 .

- Michael Menzel: Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347) and Friedrich the Beautiful (1314-1330). In: Bernd Schneidmüller , Stefan Weinfurter (Hrsg.): The German rulers of the Middle Ages. Historical portraits from Heinrich I to Maximilian I (919–1519). Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-50958-4 , pp. 393-407.

- Alois Niederstätter : The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Ueberreuter, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-8000-3526-X .

Lexicon article

- Alphons Lhotsky: Friedrich the beautiful. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , p. 487 ( digitized version ).

- Werner Maleczek : Friedrich the beautiful . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 4, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-8904-2 , Sp. 939 f.

Web links

- Entry on Friedrich der Schöne in the Austria Forum (in the AEIOU Austria Lexicon )

- Entry on Frederick the Beautiful in the State's Memory of the History of the State of Lower Austria ( Museum Niederösterreich )

- Coronation of Frederick the Beautiful in Bonn Minster 700 years ago

Remarks

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Paul-Joachim Heinig: Habsburg. In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 85–96, here: p. 85. Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 14.

- ^ MGH Constitutiones 3; 1273-1298, ed. by Jacob Schwalm, Hanover / Leipzig 1904–1906, No. 339, p. 325 f.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 151.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Family model in transition. On corporate and dynastic ideas of the Habsburgs at the time of Frederick the Fair. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 119–147.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 258.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 152.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 114.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 115.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 110.

- ↑ Andreas Büttner: The way to the crown. Rituals of the rulership in the late medieval empire. Ostfildern 2012, pp. 269–275 ( digitized version ); Andreas Büttner: Rituals of the elevation of the king in conflict. The double election of 1314 - course, interpretation and consequences. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 27–66, here: p. 29.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 116.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, pp. 190-192; Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 112.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, p. 169, quoted from ibid .: p. 200.

- ^ Ludwig Holzfurtner: The Wittelsbacher. State and dynasty in eight centuries. Stuttgart 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Heinz Thomas: Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Regensburg 1993, pp. 40-42.

- ↑ Quoted from Bernhard Lübbers: Briga enim principum, que ex nulla causa sumpsit exordium ... The battle of Gammelsdorf on November 9, 1313. Historical events and aftermath. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 205–236, here: p. 230.

- ↑ Klaus van Eickels: From staged consensus to systematized conflict. Anglo-French relations and their perception at the turn of the high and late Middle Ages. Stuttgart 2002, pp. 368-393 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Bernhard Lübbers: Briga enim principum, que ex nulla causa sumpsit exordium ... The battle of Gammelsdorf on November 9, 1313. Historical events and aftermath. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 205–236, here: p. 235.

- ↑ Stefanie Dick: Isabella von Aragón and Friedrich the beautiful. Marriage policy under the sign of royalty. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 165–180, here: p. 168.

- ↑ Stefanie Dick: Isabella von Aragón and Friedrich the beautiful. Marriage policy under the sign of royalty. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 165–180, here: p. 175.

- ↑ Stefanie Dick: Isabella von Aragón and Friedrich the beautiful. Marriage policy under the sign of royalty. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 165–180, here: p. 176.

- ↑ Stefanie Dick: Isabella von Aragón and Friedrich the beautiful. Marriage policy under the sign of royalty. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 165–180, here: p. 179.

- ↑ See introductory Michel Pauly: Balduin von Trier, the Luxemburger. In: Dioceses of Luxembourg and Trier (ed.): Balduin from the House of Luxembourg. Luxembourg 2009, pp. 175–197.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 260.

- ↑ Andreas Büttner: The way to the crown. Rituals of the rulership in the late medieval empire. Ostfildern 2012, p. 312 ( digitized version ); Andreas Büttner: Rituals of the elevation of the king in conflict. The double election of 1314 - course, interpretation and consequences. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 27–66, here: p. 45.

- ↑ Andreas Büttner: The way to the crown. Rituals of the rulership in the late medieval empire. Ostfildern 2012, p. 707 f. ( Digitized version ); Andreas Büttner: Rituals of the elevation of the king in conflict. The double election of 1314 - course, interpretation and consequences. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 27–66, here: p. 49.

- ↑ Jürgen Petersohn: “Real” and “false” insignia in German coronation custom in the Middle Ages? Critique of a research stereotype. Stuttgart 1993, pp. 83-86; Matthias Becher: The coronation of Frederick the beautiful in Bonn 1314. Classification and meaning. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 11–25, here: p. 18.

- ↑ Manfred Groten: The role of the northern Rhineland and the Archbishop of Cologne in the election of Frederick the Beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The king's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314. Coronation, war and compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 181–191, here: p. 184.

- ↑ Manfred Groten: The role of the northern Rhineland and the Archbishop of Cologne in the election of Frederick the Beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The king's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314. Coronation, war and compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 181–191, here: p. 185.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Family model in transition. On corporate and dynastic ideas of the Habsburgs at the time of Frederick the Fair. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 119–147, here: p. 132.

- ↑ Claudia Garnier: In the sign of war and compromise. Forms of symbolic communication in the early 14th century. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 229–253, here: p. 231.

- ↑ Stefanie Dick: Isabella von Aragón and Friedrich the beautiful. Marriage policy under the sign of royalty. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The medieval succession to the throne in European comparison. Ostfildern 2017, pp. 165–180, here: pp. 175 f.

- ↑ Annelies Redik: Friedrich the beautiful and Styria. In: Anja Thaller, Johannes Giessauf, Günther Bernhard (eds.): Nulla historia sine fontibus: Festschrift for Reinhard Härtel on his 65th birthday. Graz 2010, pp. 387-400, here: p. 393.

- ^ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 159 f.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 121.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 263 f.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Meeting of rulers of the late Middle Ages. Forms - rituals - effects. Ostfildern 2007, p. 218.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 265.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 265; Malte Prietzel: Warfare in the Middle Ages. Actions, memories, meanings. Paderborn et al. 2006, pp. 150–158.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Meeting of rulers of the late Middle Ages. Forms - rituals - effects. Ostfildern 2007, p. 221.

- ^ Jörg Rogge: Assassinations and battles. Observations on the relationship between royalty and violence in the German Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Martin Kintzinger, Jörg Rogge (Hrsg.): Royal violence - violence against kings. Power and murder in late medieval Europe. Berlin 2004, pp. 7–50, here: p. 39.

- ↑ Gerald Schwedler: Meeting of rulers of the late Middle Ages. Forms - rituals - effects. Ostfildern 2007, p. 232.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 124 ff.

- ↑ On the consequences cf. Heinz Thomas: Ludwig the Bavarian (1282-1347). Emperors and heretics. Regensburg 1993, p. 163 ff.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 124 ff.

- ^ Regesta Habsburgica. Regesta of the Counts of Habsburg and the Dukes of Austria from the House of Habsburg, ed. by Oswald Redlich, 3rd Department: The Regests of the Dukes of Austria and Frederick the Fair as German King from 1314–1330, edited. by Lothar Gross, Innsbruck 1924, no. 1511; MGH Constitutiones 6/1, ed. by Jacob Schwalm, Hannover 1914-1927, No. 29, p. 18 ff.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 269.

- ↑ Claudia Garnier: In the sign of war and compromise. Forms of symbolic communication in the early 14th century. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 229–253, here: p. 249.

- ↑ MGH Constitutiones 6.1, ed. by Jacob Schwalm, Hannover 1914-1927, p. 72 ff., no. 105.

- ↑ Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double kingship of Frederick the Beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: pp. 56–64.

- ^ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbook of German History. Volume 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 167.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 126.

- ↑ Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double kingship of Frederick the Beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: p. 79.

- ↑ Gerd Althoff: The peace, alliance and community-creating character of the meal in the early Middle Ages. In: Irmgard Bitsch, Trude Ehlert, Xenja von Ertzdorff (eds.): Eating and drinking in the Middle Ages and modern times. Sigmaringen 1987, pp. 13-25.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 271.

- ↑ Florian Hartmann: Letter Customs in Unusual Times. Letters and doctrines in times of the double kings. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 271–288, here: p. 277; Gerald Schwedler: The changing family model. On corporate and dynastic ideas of the Habsburgs at the time of Frederick the Fair. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 119–147, here: p. 139.

- ↑ Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: Works of art from the environment of Friedrich the beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 303–343, here: p. 337.

- ↑ Claudia Garnier: In the sign of war and compromise. Forms of symbolic communication in the early 14th century. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 229-253, here: pp. 251f.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Emperor Ludwig IV. Imperial rule and imperial princely consensus. In: Journal for Historical Research 40, 2013, p. 369–392, here: p. 382. Claudia Garner: Der doppelte König. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 288.

- ↑ Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double kingship of Frederick the Beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: pp. 54–64, here: p. 79.

- ^ Claudia Garnier: Staged Politics. Symbolic communication during the reign of Ludwig of Bavaria using the example of alliances and peace agreements. In: Hubertus Seibert (ed.): Ludwig the Bavarian (1314-1347). Empire and rule in transition. Regensburg 2014, pp. 169–190, here: p. 188.

- ↑ Claudia Garner: The double king. To visualize a new concept of rule in the 14th century. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 44 (2010), pp. 265–290, here: p. 286.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: Ludwig IV. And Friedrich the beautiful. Vienna - Mühldorf - Munich. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 255–270, here: p. 269.

- ^ Jörg Rogge: Assassinations and battles. Observations on the relationship between royalty and violence in the German Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries. In: Martin Kintzinger, Jörg Rogge (Hrsg.): Royal violence - violence against kings. Power and murder in late medieval Europe. Berlin 2004, pp. 7–50, here: p. 42.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer: From place to place. Tasks and results of research into outpatient domination practice. In: Caspar Ehlers (Ed.): Places of rule. Medieval royal palaces. Göttingen 2002, pp. 11-23.

- ^ Ferdinand Opll: Rule through presence. Thoughts and Comments on Itinerary Research. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 117 (2009), pp. 12–22.

- ^ Günther Hödl: Friedrich the Beautiful and the Vienna Residence. A contribution to the capital city problem. In: Yearbook of the Association for the History of the City of Vienna 26 (1970), pp. 7–35.

- ^ Günther Hödl: Friedrich the Beautiful and the Vienna Residence. A contribution to the capital city problem. In: Yearbook of the Association for the History of the City of Vienna 26 (1970), pp. 7–35, here: p. 23; Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 157.

- ↑ Günther Hödl: Friedrich der Schöne (1314-30). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 292–295, here: p. 293.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 159.

- ^ Günther Hödl: Friedrich the Beautiful and the Vienna Residence. A contribution to the capital city problem. In: Yearbook of the Association for the History of the City of Vienna 26 (1970), pp. 7–35, here: p. 22.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 157.

- ↑ Werner Rösener: Hof . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 5, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-7608-8905-0 , column 66 f.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 23.

- ↑ Günther Hödl: Friedrich der Schöne (1314-30). In: Werner Paravicini (ed.): Courtyards and residences in the late medieval empire. A dynastic topographical handbook. Vol. 1: Dynasties and courts. Ostfildern 2003, pp. 292–295, here: p. 294.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 353.

- ↑ Florian Hartmann: Letter Customs in Unusual Times. Letters and doctrines in times of the double kings. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 271–288, here: p. 274.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, passim.

- ^ Reprint of the deed of foundation of April 18, 1316 in: Rolanda Hantschk: The history of the Kartause Mauerbach. Salzburg 1972, pp. 139-142.

- ↑ Katrin Proetel: Great work of a "little king". The legacy of Frederick the Beautiful between disposition and execution. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Foundations and Foundation Realities. From the Middle Ages to the present. Berlin 2000, pp. 59–95, here: p. 61.

- ↑ Claudia Moddelmog: Royal foundations of the Middle Ages in historical change. Quedlinburg and Speyer, Königsfelden, Wiener Neustadt and Andernach. Berlin 2012, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Katrin Proetel: Great work of a "little king". The legacy of Frederick the Beautiful between disposition and execution. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Foundations and Foundation Realities. From the Middle Ages to the present. Berlin 2000, pp. 59–95, here: p. 63.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 160.

- ^ Alfred Strnad: The Diocese of Passau in the church policy of Frederick the beautiful. In: Communications from the Upper Austrian Provincial Archives. Volume 8, Linz 1964, pp. 188–232, here pp. 207f, note 81, online (PDF) in the forum OoeGeschichte.at.

- ↑ Annelies Redik: Friedrich the beautiful and Styria. In: Anja Thaller, Johannes Giessauf, Günther Bernhard (eds.): Nulla historia sine fontibus: Festschrift for Reinhard Härtel on his 65th birthday. Graz 2010, pp. 387-400, here: p. 399 f.

- ^ Robert Suckale: The court art of Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria. Munich 1993.

- ^ Christian Freilang: On the question of court art in the empire and in France in the 14th century. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 289–301.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 129.

- ↑ Katrin Proetel: Great work of a "little king". The legacy of Frederick the Beautiful between disposition and execution. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Foundations and Foundation Realities. From the Middle Ages to the present. Berlin 2000, pp. 59-95, here: p. 65; Michael Borgolte: The grave in the topography of memory. On the social structure of remembrance of the dead in Christianity before modernity. In: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 111 (2000), pp. 291–312, here: p. 303.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: pp. 156f.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, p. 306.

- ^ Heinrich Koller: The Habsburg tombs as a characteristic of political leitmotifs in Austrian historiography. In: Dieter Berg, Hans-Werner Goetz (Ed.): Historia Medievalis. Studies of historiography and source studies of the Middle Ages. Festschrift for Franz-Josef Schmale on his 65th birthday. Darmstadt 1988, pp. 256-269, here: pp. 260 and 267.

- ↑ Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: Works of art from the environment of Friedrich the beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 303–343, here: p. 339.

- ↑ Claudia Moddelmog: Royal foundations of the Middle Ages in historical change. Quedlinburg and Speyer, Königsfelden, Wiener Neustadt and Andernach. Berlin 2012, p. 172.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 163.

- ^ Rudolf J. Meyer: King and Emperor burials in the late Middle Ages. From Rudolf von Habsburg to Friedrich III. Vienna 2000, p. 75.

- ↑ Michael Borgolte: The grave in the topography of memory. On the social structure of remembrance of the dead in Christianity before modernity. In: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 111 (2000), pp. 291–312, here: p. 303.

- ^ Rudolf J. Meyer: King and Emperor burials in the late Middle Ages. From Rudolf von Habsburg to Friedrich III. Vienna 2000, pp. 67-75; Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 163 f.

- ↑ Austrian Chronicle of the 95 Dominions, ed. Joseph Seemüller (MGH Dt. Chron. 6), Hanover 1906/09, p. 196.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, p. 169.

- ^ Christian Lackner: The first 'Austrian' Habsburg Frederick the Beautiful and Austria. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 149–164, here: p. 150.

- ↑ Martin Clauss: War defeats in the Middle Ages. Presentation - interpretation - coping. Paderborn 2010, p. 260.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: Sources on Ludwig the Bavarian. In: Journal for Bavarian State History 60 (1997), pp. 71–86, here: pp. 78 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ^ Chronica de ducibus Bavariae. In: Bavarian Chronicles of the XIV Century , ed. by Georg Leidinger. Hannover 1918, p. 151–175, here: p. 157. Cf. also Klaus van Eickels : Trust in the mirror of treason. The chance of handing over trust-building gestures in medieval historiography. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 39 (2005), pp. 377–385, here: pp. 383 f.

- ↑ Klaus van Eickels: Trust in the mirror of betrayal. The chance of handing over trust-building gestures in medieval historiography. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 39 (2005), pp. 377–385

- ↑ On the author and work cf. Urban Bassi, Margit Kampter: Studies on the historiography of Johann von Viktring. Klagenfurt 1997; Alphons Lhotsky: Source studies on the medieval history of Austria. Graz et al. 1963, p. 292 ff.

- ↑ Katrin Proetel: Great work of a "little king". The legacy of Frederick the Beautiful between disposition and execution. In: Michael Borgolte (ed.): Foundations and Foundation Realities. From the Middle Ages to the present. Berlin 2000, pp. 59–95, here: p. 76.

- ↑ Michael Borgolte: The grave in the topography of memory. On the social structure of remembrance of the dead in Christianity before modernity. In: Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 111 (2000), pp. 291–312, here: p. 304.

- ↑ Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: Works of art from the environment of Friedrich the beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 303–343, here: p. 319.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 115; Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281–1358). Vienna 1967, p. 171; Image at Habsburger.net.

- ↑ Sarit Shalev-Eyni: Art as history. For illumination of Hebrew manuscripts from the Lake Constance area. Trier 2011, p. 17 f.

- ↑ Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck: Works of art from the environment of Friedrich the beautiful. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 303–343, here: pp. 335 f.

- ^ Karl Borromäus Murr : The Middle Ages in the Modern Age. The public memory of Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian in the Kingdom of Bavaria. Munich 2008, pp. 238-251.

- ↑ Schiller's poem Deutsche Treue at Zeno.org .

- ^ Matthias Becher: The coronation of Friedrich the beautiful in Bonn 1314. Classification and meaning. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 11–25, here: p. 24.

- ^ Karl Borromäus Murr: The Middle Ages in the Modern Age. The public memory of Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian in the Kingdom of Bavaria. Munich 2008, pp. 225 and 251.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, p. 173.

- ↑ Bernd Schneidmüller: Consensus - Territorialization - Self-interest. How to deal with late medieval history. In: Frühmittelalterliche Studien 39 (2005), pp. 225–246, here p. 232.

- ↑ Michael Menzel: The time of drafts (1273-1347) (= Gebhardt Handbuch der Deutschen Geschichte. Vol. 7a). 10th, completely revised edition. Stuttgart 2012, p. 12.

- ↑ Marie-Luise Heckmann: The double kingship of Frederick the Beautiful and Ludwig of Bavaria (1325 to 1327). Contract, execution and interpretation in the 14th century. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 109 (2001), pp. 53–81, here: p. 80.

- ↑ Alphons Lhotsky: History of Austria since the middle of the 13th century (1281-1358). Vienna 1967, p. 308 f.

- ^ Günther Hödl: Habsburg and Austria 1273–1493. Shape and shape of the Austrian late Middle Ages. Vienna 1988, p. 64.

- ↑ Karl-Friedrich Krieger: The Habsburgs in the Middle Ages. From Rudolf I to Friedrich III. 2nd, updated edition, Stuttgart 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Alois Niederstätter: The rule of Austria. Prince and country in the late Middle Ages. Vienna 2001, p. 130.

- ↑ Annelies Redik: Friedrich the beautiful and Styria. In: Anja Thaller, Johannes Giessauf, Günther Bernhard (eds.): Nulla historia sine fontibus: Festschrift for Reinhard Härtel on his 65th birthday. Graz 2010, pp. 387-400, here: p. 399.

- ^ Matthias Becher: The coronation of Friedrich the beautiful in Bonn 1314. Classification and meaning. In: Matthias Becher, Harald Wolter-von dem Knesebeck (Hrsg.): The King's rise of Frederick the Beautiful in 1314: Coronation, War and Compromise. Cologne 2017, pp. 11–25, here: p. 24.

- ↑ See the reviews by Ralf Lützelschwab in: Mediaevistik 30 (2017), pp. 448–450; Herwig Weigl in: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 126 (2018), pp. 185–188 ( online ); Ivan Hlaváček in: Český časopis historický 115 (2017), p. 1173 ( online ); Immo Eberl in: Historische Zeitschrift 309 (2019), pp. 484–485.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Leopold I. |

Count of Habsburg 1326-1330 |

Albrecht II. |

| Albrecht I. |

Duke of Austria and Styria (III. And I.) 1308–1330 (with Rudolf III. Until 1307, Leopold I until 1326) |

Albrecht II. |

| Henry VII |

Roman-German king 1314–1330 |

Ludwig IV. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Friedrich the fair |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Friedrich III. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Duke of Austria, Roman-German King |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1289 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vienna |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 13, 1330 |

| Place of death | Gutenstein |