Iron hammer

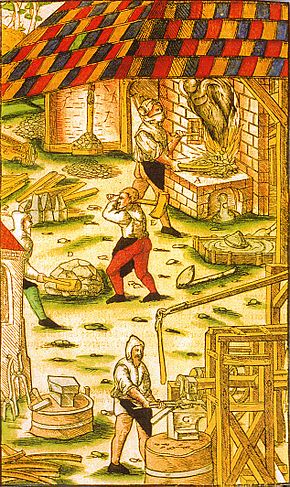

An iron hammer is a workshop for the manufacture of wrought iron as semi-finished products and consumer goods made from it from the time before industrialization . The name-giving feature of this hammer forge was the water-powered tail hammer . The hammer was lifted by a shaft on which radial "thumbs" (see also camshaft ) were attached, which periodically pressed down the end of the hammer handle and thus raised the hammer head. When falling up and down, the latter moved in a circular line . The Hammerbahn was steeled for long-term use.

Hammer mills

Initially, the ore was processed in factories that were only moved by muscle power (in so-called pedal huts or fabricae pedales ). These huts were not located on rivers, but near the iron ore deposits, mostly on the slopes of mountains. With the introduction of forge hammers and bellows powered by water power in the 14th century, hammer mills were founded on rivers and streams. In the 19th century the works were operated by steam power; this innovation caught on when the workpieces to be machined became larger and larger over time and were difficult to machine by hand.

The ore to be processed has already been pre-cleaned underground. It then first had to be roasted and chopped to the size of a nut . Before it was crushed by machines, the ore was crushed by hand. The ore chunks were then picked out on "klaubtischen" and again cleaned of loamy parts in a washing process. The iron hammers smelted iron ore with charcoal (sometimes also with peat ) in so-called racing stoves ( Georgius Agricola 1556, also known as "racing fire" or "racing furnace": from the "draining" of the slag or "Zerenn-" or "Zrennherd" from the melting ) . In these smelting furnaces, which were also equipped with bellows operated by water power, the ore was melted after a three to four hour "cutting" into a glowing lump of about 175 kg of raw soft iron and coal residues. During the smelting process, the liquid slag , which still contained up to 50% iron, drained again and again. During this process, the iron did not become liquid like in a blast furnace , but remained a "doughy" and porous lump. This historic Luppe -called lump, as because of its porous consistency sponge iron called, was initially manually using sledgehammers compacted. The iron was then forged several times with the mechanical tail hammer or sledgehammer until all slag and coal residues were removed. For this, the iron in a (was Eat ), fire extinguishing or fire hearth or corrugated called heated. The forged iron could then be used directly as soft wrought iron . A subsequent remuneration process such as refining in the blast furnace process was not necessary. When heated in the corrugated fire, liquid Deucheleisen was also formed , which collected in the bottom of the corrugated hearth. This "zwieschmolzene Deuchel" was traded and processed separately.

The resulting coarse bar iron was partly forged externally in separate small hammer hammers into thin iron bars (or strong wires ), the so-called tooth iron , which was needed by nail smiths for the production of nails , for example . Further processing to the so-called fermentation steel ( refining steel ), elastic steel, as z. B. for epee blades , was carried out by specialized refining hammers or by blacksmiths on site.

As early as the 13th century, an iron hammer was usually the union of a smelter and a processing facility. But there were also cases where only one smelter was operated (e.g. the Pielenhofen ironworks ) and the pellet was given to smelters for further processing. This also determined the appearance of a hammer hut: the mostly two chimneys were characteristic : one for extracting the smoke from the racing furnace, which was used to extract the pig iron, the other for the forge furnace for forging under a water-powered hammer . There were also two (or more) water wheels to drive the bellows and the forging hammers. The interior of a hammer workshop consisted of the two herds mentioned, the bellows made of wood and pigskin, one or more water-powered tail hammers each with a hammer stick, smaller and larger anvils and a variety of other handicraft and blacksmith tools.

The wealthy owners of hammer mills, especially along today's Bavarian iron road and Austrian iron road (called “Black Counts”), built representative mansions, the so-called hammer castles, next to their hammer mills .

Workers in a hammer mill

A hammer was owned by a hammer gentleman. This often gained respect, performed important local functions (mayor, council member) and occasionally rose to the lower nobility (e.g. the Sauerzapf or the Moller von Heitzenhofen ).

For the operation of a hammer, a “hut caper” was usually employed, who organized the work processes of a hut as hammer master or supervisor. If several wax burners were operated, a shift supervisor also had to be employed.

The next most important person was the "Zerenner" (also called "Zerennmeister"), who was responsible for the correct loading of the furnace with charcoal and ore and the tapping . The quantity and quality of the iron obtained depended on his skill and the accuracy of his work. He was assisted by one or more “Zerennknechte” who brought ore and coal into the smelter, removed the iron slugs from the furnace and removed the slag produced during the smelting process.

A hut also employed one or more "Handpreu" (also called "Handprein"); they were assistants employed in a hammer. One of them was the "Hauer" or "Kohlzieher", who was responsible for providing charcoal.

A blacksmith master worked with one or more blacksmiths on the well and the tail hammer. They forged the shell into commercially available iron rails or rods.

The "Kohlmesser", also known as the "Kohlvogt", assumed an official function. Each hammer owner had to have the amount of coal delivered and processed by an ordered coal knife recorded. If this was not done, severe penalties threatened. The amount of coal was entered in a kerbholz , half of which was given to the hammer owner and the other half to the charcoal burner , in order to be able to make an exact account to the forester. The cabbage knives were sworn in and were only allowed to measure the coals according to the calibrated measurements under threat of punishment. This was important because the hammer lords were given a certain amount of charcoal, measured in buckets and barriers, from the manorial forests .

An iron hammer had to employ more servants and one or more wagoners to keep the business going. Occasionally, charcoal burners , known as “assassins”, were employed by a hammer. One can assume at least eight people employed in an iron hammer, whereby this number could also increase to 80 (e.g. for the Heitzenhofen hammer ).

distribution

In hammer mills, a distinction has to be made between iron- producing and iron- processing plants. The former include the tibia and bar hammers to the latter, the sheet metal , wire , Zain- , stretching , refining and ball hammers and Zeug- and weapons hammers .

Geographically, the iron hammers were dependent on the availability of water power (see hammer mill ). At the same time, forests had to guarantee the production of large quantities of charcoal. In addition, there had to be iron ore deposits in the vicinity in order to enable short transport routes for the iron-bearing rock to smelting. Agriculturally usable areas were also important for feeding the many workers needed.

Many localities or districts are now named after hammer mills or hammer mills that used to exist there.

Germany

Iron hammers were widely used from the late Middle Ages

- in the Bergisches Land (with well over a hundred systems),

- in the Upper Palatinate , especially near the cities of Amberg and Sulzbach ,

- in the Thuringian Forest : Lauterhammer and Niederhammer in Suhl as early as 1363, Tobiashammer in Ohrdruf (later also Kupferhammer and Kupfermühle ),

- in the Fichtel Mountains ,

- in the Ore Mountains : 1352 Hammer in Pleil, around 1380 Hammer Erla, Frohnauer Hammer ,

- in the Harz ,

- in the Siegerland on the Sieg (today about Siegen ),

- in the Sauerland around Hagen , see also hammer mills in the Sauerland ,

- in the Lahn-Dill area and on the upper Eder .

In these areas there were iron deposits that could be extracted with the means available at the time. There was a high density of several hundred systems in the Wupperviereck .

The Upper Palatinate was one of the European centers, which earned it the nickname "Ruhr area of the Middle Ages" due to the many hammer mills. Place names ending in -hammer are very common in this area. The manor house belonging to an iron hammer is known as the hammer lock. These mostly inconspicuous castle complexes, which served as the seat of the hammer lords, are usually located in the immediate vicinity of the hammer mill. There are significant hammer locks along the Bavarian Iron Road , for example in Theuern , Dietldorf and Schmidmühlen .

Austria

In Austria, iron hammers were particularly widespread in the Eisenwurzen along the Austrian Iron Road in the triangle of Lower Austria - Styria - Upper Austria (e.g. Ybbsitz ) and in the Upper Styrian valleys of the Mur and Mürz and their side valleys. The seats of the Hammerherren (Black Counts) there are called Hammerherrenhäuser .

Switzerland

15 hammer smiths have survived in Switzerland.

Products

Typical products of the iron hammers were

- Bar iron ,

- Rails ,

- Black plate ,

- Tinplate and

- Wires .

These products ended up on the market as semi-finished products , but in some cases they were also processed into end products such as scythes , sickles , shovels , weapons or tack in the production plant.

Known iron hammers

Most of the facilities listed here have been preserved and are open to the public as a museum.

Germany

- Ore Mountains

- Eisenhammer Dorfchemnitz (museum)

- Erla ironworks

- Freibergsdorfer Hammerwerk (open to the public)

- Frohnauer Hammer (Museum)

- Arrow hammer

The Bavarian Iron Road is an important and historic holiday route in southern Germany, which, over a length of 120 km, connects numerous historical industrial sites from several centuries with cultural and natural monuments. Part of it is the Sulzbacher Bergbaupfad . The Bavarian Iron Road runs along old traffic routes from the Nuremberg region near Pegnitz in a southerly direction to Regensburg and connects the former iron centers of Eastern Bavaria , namely the Pegnitz, Auerbach , Edelsfeld , Sulzbach-Rosenberg and Amberg districts . From there it becomes an approximately 60 km long waterway on the rivers Vils and Naab to their confluence with the Danube near Regensburg.

- Eisenhammer in Eckersmühlen (museum)

- Hammer smithy on the Gronach near Gröningen (Satteldorf) , Hohenlohe

- Ironworks and hammer mill in Peitz (museum)

- Hammer forge (Burghausen)

- Hammer and bell forge in Ruhpolding (museum)

- Oelchenshammer (museum)

- Upper Palatinate

- Gaisthal hammer

- The Mining and Industry Museum East Bavaria in Theuern (municipality of Kümmersbruck ) is a nationally important museum that researches and documents the mining and industry of the entire East Bavarian region. The museum was established in 1978 in the former Hammerherrenschloss Theuern . In addition to the castle, the museum area includes three other industrial monuments typical of the region, which have been transferred to Theuern. One of the outdoor facilities of the museum is the Staubershammer hammer mill. The plant was broken up in 1973 near Auerbach and originally rebuilt in Theuern. Most of its factory equipment dates from the end of the 19th century.

- Eisenhammer Edlhausen

- Eisenhammer Shell Hops

- Ruhr area

- Deilbachhammer (museum)

- Sauerland

- Bremecker Hammer Lüdenscheid (museum)

- Luisenhütte (museum)

- Oberrödinghauser Hammer (Museum)

- Wendener Hut (museum)

- historical hammer mill in Blaubeuren (museum)

- Spessart

- Eisenhammer in Hasloch (museum)

- Thuringian Forest

- Tobiashammer (museum)

- Eisenhammer Weida (museum, functional monument)

- historical hammer mill in Dassel (museum)

- Lower iron hammer Exten (museum)

- Hammer mill in Dinkelsbühl, Middle Franconia

- Hammer mill in Moosbach, Upper Palatinate

- Hammer forge Grafing

- Augsburg hammer mill

- Hammerschmiede Scholl in Bad Oberdorf

- Hammerschmiede Neue Welt , Münchenstein

- Tobiashammer in Ohrdruf (later also copper hammer or copper mill )

- Freibergsdorf hammer

- Hammerschmiede Schwabsoien

- Frohnauer Hammer

Hammer smithy in Corcelles BE , Switzerland

A hammer forge in Amendingen (around 1930)

Austria

- The Hammerbachtal lies between Lassing (municipality of Göstling) and Hollenstein an der Ybbs . The remains of the hammer mills of the time can be viewed here, namely the Hof-Hammer, the Wentsteinhammer, the Pfannschmiede and the Treffenguthammer

- Along the forge mile in Ybbsitz there are several hammer mills, the Fahrngruber hammer, the Eybl hammer mill with artist workshop , the Strunz hammer and the Einöd hammer. The unique cultural ensemble for iron and metal processing was included in the register of intangible cultural heritage in Austria in 2010 . (See also: forging in Ybbsitz)

- In Vordernberg you can visit historic blast furnaces ( wheel works ) and the Lehrfrischhütte. This conveys the atmosphere of an old forge, whose still fully functional tail hammer is driven by a water wheel. This hammer is mainly used for show forging.

reception

The iron hammer got its firm place in literature through Friedrich Schiller's ballad Der Gang nach dem Eisenhammer (1797), which was set to music by Bernhard Anselm Weber for the actor August Wilhelm Iffland as a great orchestral melodrama and later arranged as a fully composed ballad by Carl Loewe .

literature

- Ludwig Beck: The history of iron in technical and cultural-historical significance. 5 volumes. Friedrich Vieweg and son , Braunschweig 1893–1895.

- Jutta Böhm: Mill bike tour. Routes: Kleinziegenfelder Tal and Bärental. Weismain environmental station in the Lichtenfels district, Weismain / Lichtenfels (Lichtenfels district), 2000.

- Gaspard L. de Courtivron, Étienne Jean Bouchu : Treatise of the iron hammers and high ovens. Translated from the French of the “Descriptions des arts & metiers” and annotated by Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi . Rüdiger, Berlin, Stettin and Leipzig 1763 (E-Book. Sn, Potsdam 2010, ISBN 978-3-941919-72-3 ).

- Peter Nikolaus Caspar Egen : Hammerwerke , in ders .: Investigations on the effect of some existing waterworks in Rhineland-Westphalia , ed. from the Ministry of the Interior for Trade, Industry and Construction, Part I-II. A. Petsch, Berlin 1831, pp. 69–95 ( Google Books ) (detailed presentation of mechanics and technology)

- Lothar Klapper: Stories about huts, hammers and hammer masters in the central Ore Mountains. A lecture on the history of former huts and hammers in the district of Annaberg (= forays through the history of the Upper Ore Mountains 32, ZDB -ID 2003414-3 ). Volume 1. New local history working group, Annaberg-Buchholz 1998, online version .

- Bernd Schreiter : Hammer works in the Preßnitz and Schwarzwassertal (= Weisbachiana. Issue 27, ZDB -ID 2415622-X ). 2nd, edited edition. Verlag Bernd Schreiter, Arnsfeld 2006.

- Johann Christian zu Solms-Baruth, Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi: Treatise of the iron hammers and high furnaces in Germany. Rüdiger, Berlin, Stettin and Leipzig 1764 (e-book. Becker, Potsdam 2010, ISBN 978-3-941919-73-0 ).

- E. Erwin Stursberg : History of the iron and steel industry in the former Duchy of Berg (= contributions to the history of Remscheid. Issue 8, ISSN 0405-2056 ). City archive, Remscheid 1964.

Web links

- Bavarian iron road

- Mining and Industry Museum East Bavaria

- Deilbachtal cultural landscape

- Photo documentation Hammerwerk Erft

- Hammerschmiede Burghausen (proven since 1465)

- Literature database on historical mining, metallurgy and saltworks

- Upper iron hammer in Exten

- Fahrngruber Hammer in Ybbsitz (Austria)

- The oldest operated hammer forge in Europe in Burghausen

Individual evidence

- ↑ Short biography

- ↑ [1] . Explanation “stealing”. At www.enzyklo.de. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ↑ Reinhard Dähne & Wolfgang Roser: "The Bavarian Eisenstrasse from Pegnitz to Regensburg." House of Bavarian History, Volume 5, Munich 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Götschmann, Dirk: Upper Palatinate iron. Mining and iron industry in the 16th and 17th centuries. Edited by the Association of Friends and Sponsors of the Mining and Industry Museum in East Bavaria (= Volume 5 of the series of publications by the Mining and Industry Museum in East Bavaria), Theuern 1985, p. 68. ISBN 3-924350-05-1 .

- ^ Carl Johann Bernhard Karsten: Handbook of the iron and steel industry. Bar preparation and steel production. In: Berlin. 1828, Retrieved February 2, 2018 .

- ↑ Hüttkapfer in the German legal dictionary

- ↑ Johann Georg Lori : Collection of the Baierischen Bergrechts: with an introduction to the Baierische Bergrechtsgeschichte , S. 578. (No longer available online.) In: Franz Lorenz Richter, Munich. 1764, formerly in the original ; accessed on March 19, 2018 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Thomas Wagnern: Corpus juris metallici recentissimi et antiquioris. Collection of the newest and older mining laws. In: Johann Samuel Heinsius. 1791, p. 616 , accessed March 21, 2018 .

- ↑ Franz Michael Ress: History and economic importance of the Upper Palatinate iron industry from the beginning to the time of the 30-year war. Negotiations of the Historical Association of the Upper Palatinate, 91, 1950, 5-186.

- ^ Franz Michael Ress: The Upper Palatinate iron industry in the Middle Ages and in the early modern times. Archives for the iron and steel industry , 1950, 21st year, p. 208.

- ↑ Herbert Nicke : Bergische Mühlen - On the trail of the use of water power in the land of a thousand mills between Wupper and Sieg ; Galunder; Wiehl; 1998; ISBN 3-931251-36-5 .

- ↑ K. Erga: The Ruhr area of the Middle Ages. Oberpfälzer Heimat , Volume 5, 1960, pp. 7–2.

- ↑ Klaus Altenbuchner, Michael A. Schmid: The hammer lock in Schmidmühlen. To rediscover an Italian style castle and its important decoration. In: Negotiations of the historical association for Upper Palatinate and Regensburg. Vol. 143, 2003, ISSN 0342-2518 , pp. 397-418.

- ↑ Mill list Switzerland , 2009. Retrieved from the “Association of Swiss Mill Friends” on June 7, 2013. (PDF file, 33 kB.)

- ↑ Schmieden in Ybbsitz ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved March 29, 2013.