Judensau

The animal metaphor "Judensau" refers to a common motif of anti-Judaist Christian art that was created in the High Middle Ages . It was supposed to mock, ostracize and humiliate Jews , since in Judaism the pig is considered unclean ( Hebrew tame ) and is subject to a religious taboo on food . Mocking pictures with the Judaism motif have been documented since the early 13th century and can still be seen on stone reliefs and sculptures at around 30 churches and other buildings, especially in Germany .

Since the 15th century the motif has also appeared as an aggressive type caricature in pamphlets and other printed matter, and since the 19th century as an anti-Semitic caricature. The swear words “Judensau” and “Judenschwein” have been used in German-language literature since the 1830s at the latest , and “Saujude” since the late 1840s . The National Socialists took up these motifs and swear words and used them for incitement , slander , humiliation and threats.

Anyone who uses these expressions to people today or expresses them publicly about them is liable to prosecution in Germany ( Section 185 of the Criminal Code ) and Austria ( Section 115 of the Austrian Criminal Code ) for insulting and in Switzerland under the racism penal norm (Section 261 to StGB ). In particularly serious cases in Germany, punishment for sedition ( Section 130 ) can also be considered.

The medieval motif

distribution

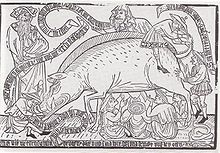

Medieval sculptures, reliefs or pictures of a “Jewish sow” depict people and pigs in intimate contact. The human figures show the typical characteristics of the Jewish costume that was prescribed in many places at the time , such as a “ Jewish hat ” or yellow ring . Usually these figures suckle like piglets on the teats of a sow. In other variants, they ride a pig upside down, their face turned towards the anus , from which urine spurts, or they hug or kiss pigs.

48 such representations are known in Europe; in Central Europe they can still be found in around 30 locations. Some are so badly weathered that the motif is unrecognizable. Some were not listed in sources and have only been rediscovered since 2000.

| No | image | place | country | building | Art | Time of origin | Status | description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Aarschot | Belgium | Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk (Church of Our Lady) | Misericord | late 15th century or 1510-1525 | receive | Jewish figure rides backwards on a billy goat. |

| 2 | Ahrweiler | Germany | St. Laurence | Gargoyles | 1295 | well preserved | ||

| 3 | Bacharach | Germany | Werner Chapel | Gargoyles | around 1290 | partially destroyed | ||

| 4th |

|

Bad Wimpfen | Germany | Collegiate Church of St. Peter | Gargoyles | restored copy | Preserved original is in the Imperial City Museum . | |

| 5 | Basel | Switzerland | Basel Minster | Relief on the misericords of the canon stalls | after 1363 | Removed in 1997 and stored in the Historical Museum. | Pig suckling two men in Jewish hats. | |

| 6th |

|

Bayreuth | Germany | City Church | Sandstone sculpture | partially destroyed | Was partially knocked off in November 2004 - a plaque on the base indicates the former depiction. Condition before November 2004 can be seen here . | |

| 7th |

|

Brandenburg on the Havel | Germany | St. Peter and Paul Cathedral | Column capital in the cloister | around 1230 | well preserved | |

| 8th | Bützow | Germany | Collegiate church | Relief on the column capital in the central nave | around 1314 | receive | ||

| 9 |

|

Cadolzburg | Germany | Cadolzburg | Sandstone relief on the castle gate | 1380-1480 | badly weathered | Largest known Judensau sculpture. |

| 10 | Calbe (Saale) | Germany | St. Stephen's Church | Gargoyles | 15th century | 2019/2020 removed | ||

| 11 |

|

Colmar | France | Martinsmünster | a gargoyle and a figure at the west portal | around 1350 | ||

| 12 | Eberswalde | Germany | Maria Magdalenen Church | Column capital | ||||

| 13 | Erfurt | Germany | Erfurt Cathedral | Late Gothic bas-relief, carving on the left side of the left choir stalls | 14th century | well preserved | The relief shows the fight between two people rushing towards each other: from the left comes a young man, sitting on a horse and armed with a shield and a lance; from the right an unarmed Jew sitting on a saddled and bridled sow. | |

| 14th |

|

Frankfurt am Main | Germany | Old bridge tower , not far from Frankfurt's Judengasse | Mural | 1475 | destroyed | was a tourist attraction in Frankfurt until the bridge tower was demolished in 1801 |

| 15th | Gniezno | Poland | Arch-Cathedral of Gniezno , St. Andrew's Chapel | Capital with relief, portal on the right side | around 1350 | |||

| 16 |

|

Goslar | Germany | from an unknown building | Fragment of a sandstone column | 1150 to 1250 | well preserved | One Jew, recognizable by the cone hat, stabs the pig in the snout, the other tries to milk it. |

| 17th | Heilbad Heiligenstadt | Germany | Anne Chapel | Fragment of a gargoyle on the north corner | around 1300 | badly weathered | broken or not recognizable | |

| 18th |

|

Heilsbronn | Germany | Heilsbronn Monastery | Sculpture on a column in the “Mortuarium” as a base for a figure of a saint | 15th century | ||

| 19th | Kelheim | Germany | at the city pharmacy | figure | 1519 | destroyed | was removed in 1945 after the end of World War II , probably on the instructions of a US Army officer. | |

| 20a |

|

Cologne | Germany | Cologne cathedral | Side wall of the choir stalls, wood | around 1310 | well preserved | In the picture the left quatrefoil, the right one refers to the legend of the ritual murder . See also: Judensau on the choir stalls of Cologne Cathedral |

| 20b |

|

Cologne | Germany | Cologne cathedral | Gargoyles on the southeast choir | around 1280 | restored and secured | |

| 21st |

|

Lemgo | Germany | St. Marien , western atrium | Sandstone sculpture | around 1310 | receive | A kneeling Jew with a pointed hat holds or hugs a pig. |

| 22nd |

|

Lutherstadt Wittenberg | Germany | City Church , southeast wing | Sandstone relief with engraving | around 1440; other sources: around 1300 | well preserved, restored | |

| 23 |

|

Magdeburg | Germany | Magdeburg Cathedral , Ernst Chapel | Sandstone frieze with traces of paint | around 1270 or 1493 | well preserved | A Jew in a pointed hat kneels under a sow and sucks on one of her teats. Two piglets are to the right of it. On the left a bearded Jew is turned towards the rear of the sow (his broken right hand may have originally touched the sow). Around the corner is a scene with an oak tree and two people: a woman facing the sow, holding a bowl of acorns, and a Jew with a scroll. |

| 24 |

|

Metz | France | Metz Cathedral , Carmel Chapel | Sandstone relief | around 1300-1330 | ||

| 25th | Nordhausen | Germany | Nordhausen Cathedral | carved choir stalls | around 1380 | receive | ||

| 26th |

|

Nuremberg | Germany | St. Sebald , southeast choir | Sandstone sculpture as a console | around 1380 | well preserved, restored | Two Jews are shown hanging from the teats of a sow (the one on the left shows a Jewish hat). A third feeds the sow on the left, while a fourth collects its excrement in a pot. The console was originally intended to carry a figure of a saint and is now about seven meters high behind a wire mesh that protects against contamination by pigeons. |

| 27 |

|

regensburg | Germany | Regensburg Cathedral | Stone sculpture, wall pillars outside at the south entrance | 14th century | ||

| 28 |

|

Pirna | Germany | Marienkirche | Stone sculpture at the foot of the pulpit | 1546 | well preserved | The person depicted can be identified as a Jew by their typical hat, their face is that of a pig, they are about to hide a purse under their coat. |

| 29 | Salzburg | Austria | Town hall tower | Stone sculpture | around 1487 | destroyed | created by the sculptor Hans Valkenauer on behalf of the city council. It was removed around 1800. | |

| 30th | gap | Germany | House Stiftsgasse 10 (formerly Herrngasse 146) | Sandstone relief | 15th century | badly weathered | Attached to a private building (originally the library of the Spalter Canon Monastery). Was plastered during a house renovation in 1969, but could be exposed again in good time. It depicts a Jew with a pointed hat lying under a sow and sucking on one of its teats while one arm pushes up one of the sow's forelegs. | |

| 31 | Theilenberg | Germany | St. Wenceslas Church, east side of the tower | Sandstone relief | 14th century | weathered | ||

| 32 |

|

Uppsala | Sweden | Uppsala Cathedral , choir | Column capital, three-sided relief | around 1350 | ||

| 33 | Wiener Neustadt | Austria | formerly at the house at Hauptplatz No. 16, today in the city museum |

Sandstone relief | 15th century | well preserved | ||

| 34 | Xanten | Germany | Xanten Cathedral , north side in front of the high choir | Stone sculpture as the base of a figure of Mary; Figure with a Jew hat, sow bites the hat | receive | |||

| 35 |

|

Zerbst / Anhalt | Germany | St. Nikolai (ruin), on the buttress on the northeast side of the choir | Stone relief | 1446-1448 | well preserved | |

| 36 | Zerbst / Anhalt | Germany | Residential building Markt 16 | carved gothic beam | receive | today in the city museum |

origin

When YHWH calls man to his image according to Gen 1.26 EU , he places him above fellow creatures. Animals and plants should benefit man, he should preserve all life ( Gen 2.15 EU ), but not confuse created anything with God ( Ex 20.4f. EU ). The Torah forbids intimacy between humans and animals ( zoophilia ) as a particularly serious perversion and threatens it with the death penalty ( Ex 22.18 EU ). It differentiates between pure and unclean animal species and forbids the sacrifice and consumption of the latter, including the pig ( Lev 11.7 EU ; Dtn 14.8). In Isa 65,4 pigs are rejected as sacrificial animals because they were used in non-Jewish sacrificial cults. That is why the pig became a symbol of illicit sacrifice in the Jewish priesthood. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) used this biblical prohibition to persecute the Jewish religion: He ordered the Jews in his domain to sacrifice pigs ( 1 Makk 1.47 EU ). He is said to have tried to force Jews to eat pork ( 2 Makk 6,18–31 EU ). Since that time, the complete renunciation of pork has been an unconditional commitment of a devout Jew. Be based in the Talmud executed Jewish dietary laws , according to which pork and pig milk belong to the non-kosher food.

The rejection of the pig as a distinguishing feature between Jews and non-Jews is also evident in the New Testament . According to Mark 5.1–20 EU, Jesus of Nazareth has a many-headed demon called Legion , who rules a person in the non-Jewish town of Gerasa , drive into a herd of pigs, whereupon the pigs fall into the sea and drown. The demon is understood as an allusion to Roman rule, because a Roman legion stationed in Gerasa wore the pig as a legion mark and many Jews at the time wished to drive the Romans into the sea. In Mt 7,6 EU Jesus warns his disciples: “Do not give the holy things to the dogs and do not throw your pearls before the pigs, because they could trample them with their feet and turn around and tear you to pieces.” What was meant was the precious words not to waste the Torah and the message of the kingdom of God on non-Jewish, cultically unclean persecutors of Jews and early Christians. In 2 Petr 2,22 EU it says of those who turned away from the Christian faith: “The saying happened to them: The dog will eat again what it has spewed; the sow rolls around in the feces again after relieving herself. ”This portrayed the return of Jewish Christians to Judaism as unclean behavior.

Some church fathers already insulted Jews and heretics as such as "pigs". John Chrysostom applied this degradation in his eight sermons in 388 to the Jewish worship in the synagogue . With the adoption of Hellenistic catalogs of virtues and vices, Christian theology developed the series of the “seven deadly sins ” from the 5th century onwards : The last two, gluttony (Latin gula ) and lust (luxuria) , were often symbolized in images with a pig . It embodies the unclean and the sinners, whose stomach is filled with filth, whose digested excrement they left behind their offspring ( Ps 17:14 EU ). These general human errors were not identified with Judaism until the 9th century, only compared. Rabanus Maurus , in his encyclopedia De universo (847), placed Jews on the side of pigs, since both “inherited” their ungodly, sinful intemperance and unchastity in the same way. He was referring to the "self-curse" in Mt 27.25 EU : His blood come on us and our children! Here Jews like pigs were still an allegory for the two vices, against which the simple Christian was warned with drastic pictures. Also embodied monks and monkeys the inconstantia (infidelity, inconsistency).

In the early 13th century, the theological "rejection" of Judaism was cemented socio-politically: At the 4th Lateran Council in 1215, a discriminatory dress code for Jews and their exclusion from secular offices was ordered. This initiated the later Europe-wide ghettoization of the medieval Jewish communities. Sculptures on churches from the High Middle Ages symbolized the rise of Christianity to the dominant worldview by allegorically contrasting the victorious Ecclesia with the defeated synagogue (→ Ecclesia and synagogue ). At the Strasbourg cathedral, for example, the latter was portrayed as a perfectly formed, noble and majestic female figure in mourning over her defeat (created around 1230). Their blindfolded eyes symbolize the blindness of disbelief without mocking the Jews.

Change of meaning

The oldest known Judensauskulptur is the figure from around 1230 on a column capital in the cathedral cloister of Brandenburg. It shows a hybrid of a Jew and a pig, indicating that both are identical. This version was not taken up later. Isaiah Shachar also dates the Judensauskulpturen in Bad Wimpfen, Eberswalde, Lemgo, Magdeburg and Xanten to the 13th century . According to him, these early examples should not yet mock Judaism as such, but rather represent Jews as moral examples for all sinners.

Shachar dates the motifs in Colmar, Gnesen, Heiligenstadt, Cologne Cathedral, Metz, Nordhausen, Regensburg and Uppsala to the 14th century. He denied the origin of these sculptures from the motif of the Capitoline Wolf , the Romulus and Remus suckling. However, in 2013 the historian Rudolf Reiser interpreted the Regensburg sculpture as a suckling she-wolf, not as a “Jewish pig”, because of its long tail.

The conflict of religions is presented as a tournament on the choir stalls of Erfurt Cathedral . While the church rides a horse, the synagogue sits on a pig. A misericord in the Flemish Aarschot modifies the motif: There a Jew is riding a billy goat . This was also the symbol of the devil , so that the motif now went beyond mere satirical ridicule. At that time, Judaism was increasingly devalued as a depraved, filthy and ridiculous religion. In Spain , for example, Jews who had converted to Christianity through compulsory baptism were insulted as marranos (pigs) since around 1380 , as they were not believed to have turned away from Judaism and this was attributed to an unchangeable Jewish nature. Using the early racist criterion of blood purity ( limpieza de sangre ) , Spanish Christians tried to exclude baptized Jews from social advancement. In the 15th century there were nationwide pogroms and expulsions of Spanish Jews and Jewish Christians. In Spain, however, no Jewish sculptures have been found.

The Central European Judensauskulpturen are interpreted as the earliest form of anti-Jewish caricature, which fulfilled three main social-psychological functions: 1. To expose the Jews to the ridicule of the general public by pointing to their supposedly typical behavior according to the anti-Judaistic prejudices of the observer; 2. to consolidate these prejudices and to encourage demarcation from Jews, indirectly also to act against them; 3. To attack and hurt the Jews in their religious self-image. As rough mockery, they often combine the depiction of intimacy between humans and animals with excretory and digestive processes. This was aimed at the most effective defamation of the portrayed by extreme, symbolically shortened exaggeration of the "typical". The obscenity of the pictures is supposed to arouse disgust , shame , hatred and contempt in the viewer . This was intended to publicly denigrate, humiliate and exclude believing Jews from the human community in a particularly agonizing form. The viewer of the Judensaum motif was suggested that Jews do particularly sinful, repulsive, wrong and extravagant things and that they are related to pigs. That denied them their human dignity , which is what matters in their religion. At the same time, the motif cemented a social distance to the Jewish minority. That is why historians see it as a forerunner of later racial anti-Semitism .

Jewish illustrations attached to non-church buildings are mostly dated to the 15th century. They show that the audience of the viewer had spread beyond the church framework into the bourgeoisie and that Jews were now despised by society as a whole. The mural of the Frankfurt Judensau , created around 1475, was particularly provocative . It showed a rabbi riding a sow upside down, sucking a young Jew under his stomach on the teats, another on the anus or vulva ; standing behind the sow is the devil himself and a Jewess riding on a billy goat, a symbol of the devil. In addition, the mutilated corpse of Simon von Trient , who allegedly fell victim to a ritual murder of Jews, could be seen above it . The caption read: "You suck the milk, you eat the dirt, that's your best taste." This should underline that Jews are abnormal beings who are closer to animals and the devil than to humans. The connection of the Judaism motif with an anti-Judaistic ritual murder legend should stir up a pogrom mood.

The relief of Judensaur on the Wittenberg town church, created in 1280, also depicts an emphatically “perverse”, mocking image that should arouse disgust and disgust. "The Jew" then appeared as a disgusting creature. Since 1517 the town church was Martin Luther's place of preaching and the origin of the Reformation . His anti-Judaistic diatribe from 1543 with the title Vom Schem Hamphoras und vom Gen Christi interpreted the motif as follows: “Behind the Saw stands a Rabin, who lifts the Saw up his right leg, and with his left hand he draws the pirtzel over himself, The Saw stoops and peeps under the pirtzel into the Thalmud with great vein, as if he wanted to read and see something sharp and peculiar. ”With this, Luther referred the Jewish sow to the Talmud and mocked the biblical exegesis of the rabbis and the Jewish faith as a whole as dirty Ridiculousness. So he ruled out any conceivable theological dialogue with Jews and the recognition of their independent religion. Luther's rhetorically offensive inclusion of the Judaism motif entered the Reformation example and history literature.

In 1570 the sculpture was moved to the south facade of the town church and added the heading Rabini Schem HaMphoras (Hebrew "the undisguised name"). This brought the sculpture, like Luther's eponymous anti-Jewish diatribe, into connection with the biblical name of God . This connection of the ineffable name of God with an animal that is unclean according to the Torah means tremendous blasphemy for believing Jews . In the early modern period, the originally religious opposition between church and synagogue had thus condensed into a total contempt for Judaism encompassing all areas of life.

Modern reception

The carnival game by Hans Folz Ein spil von dem Herzogen von Burgland (work title: The Jews Messiah ) from the 15th century shows that the Judensau motif had also spread in German-language literature. In this stage play, the Jewish Messiah is exposed as an antichrist and at the end suggested as a punishment for the Jews:

“I say that above all one

pring the allergrost pork mother's mother, under

it they nestle all

suckers tooting with sound;

The Messiah lig under the tail! "

The scene forms the dramatic climax of the game and, because of its taboo-breaking and drastic nature, is considered to be "one of the most extensive anti-Jewish representations in the vernacular literature of the German Middle Ages".

Since the invention of the printing press (≈ 1440), mock images with the Judean seam motif have increasingly been found in books, pamphlets and “Judean medals”, especially during the Reformation period (16th century). The associative connection between Jews, sow and devil was now also transferred to their physical characteristics by caricaturing them with pig's ears, goat's feet and horns. An anti-Jewish pamphlet from 1571, for example, shows figures of Jews with the yellow spot on the cover, who are equipped with devil's claws, claw and crow's feet, and pig faces with horns and antlers. One of them, a juggler with a bagpipe, rides a sow that eats her excrement.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the particularly popular depictions of Jews from Wittenberg and Frankfurt am Main were often depicted in books for anti-Jewish purposes, for example with woodcuts and copper engravings of various variants, and in the 19th century also as specially printed graphics. The devil usually has a physiognomy that is regarded as Jewish and also wears the yellow ring. Johann Jacob Schudt described the Frankfurt Jewish picture in one of his anti-Semitic pamphlets in 1714: “... under this pig lies a young Jew / who sucks the teats / behind the sow lies an old Jew on his knees / and lets the sow urine and otherwise out of it Affter running into his mouth. ” Achim von Arnim described the same picture in his dinner speech on the characteristics of Judaism (1811) as follows:“ A rabbi sits on his back on a mother pig suckling a young Jew… another Jew listens underneath for prophecy while the Jewess clings to the horns of the scapegoat and is led to the devil by him ”. Arnim claimed that the best painters in Frankfurt had "freshened up the picture over the course of two centuries ..." because it had found "such general approval". He suggested that the picture be transferred to the curtains of the Berlin theater to “amuse the intermediate acts” in order to humiliate Jewish buyers of the best boxes there. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe mentioned that “great mockery and disgrace” in his autobiography From my life. Poetry and Truth (1808–1838).

The anti-Semitic motive

Type caricatures and insults since 1800

The continuation of anti-Jewish propaganda in the 19th century, which was widely diversified in the media, required an established association between Jews and pigs, reinforced by the pictorial evidence mentioned above. Since when “Judensau” was also used as a swear word is uncertain. An example can be found in the magazine Die Bayer'sche Landboetin in 1833 and in Der Katholik in 1836 . The German dictionary of the Brothers Grimm from 1877 does not contain the keyword "Judensau". The word "Saujude" appears in Viennese newspapers in connection with the revolutionary upheavals of 1848 and spread in printed works increasingly from the 1860s.

During the legal emancipation of the Jews (1870–1890) in the German Empire , the tradition of anti-Semitic caricatures took off. Political cartoons of the time mocked the rulers in order to educate about power relations and to promote a subversive distance among the population. Anti-Semitic caricatures, on the other hand, were directed against an inferior minority, which was delivered to the viewer as despicable and offered as a scapegoat, for example for the economic crisis of 1877. This took up current events and in the form of a "personal type caricature" of an allegedly typical, permanent character trait of all Jews pointed, which should refer to causes in the Jewish culture, religion and an alleged "race".

Since the establishment of the Weimar Republic in 1919 as a result of the November Revolution of 1918, German right-wing extremists publicly insulted democratic politicians as " November criminals" and as "Judensau". A German national Stammtisch song from around 1920 incited against the foreign minister at the time:

“Bang the guns - tak, tak, tak on the

black and on the red pack.

Also Rathenau, the Walther,

does not reach old age,

bangs from the Walther Rathenau ,

the goddamn Judensau! "

In 1922 Rathenau was shot on the street in response to this request.

National Socialism

Since 1919, the National Socialists activated the medieval anti-Judaist stereotypes that had linked the “Judensau” motif with ritual murder legends, motifs of Jews as “bloodsuckers” and “ Satan ” specifically for their propaganda . The Nazi party propaganda sheet Der Stürmer , founded in 1923, took over and increased the tradition of anti-Semitic caricatures to caricatures of Jews with crooked teeth, animal claws, dripping corners of the mouth and greedy eyes, seduced and “poisoned” crowds of young blonde girls: This combined religious with pornographic and racist motifs and related it to the “ racial disgrace ” and the “sucking out” of the “ Aryan race ”. In a caricature of the striker from April 1934, the Judensaum motif symbolizes the supposed media power of the Jews. The sow pierced with a pitchfork bears the inscription “Juden-Literatur-Verlage”, the caption reads: If the sow is dead, the piglets must also spoil. Albert Einstein , Magnus Hirschfeld , Alfred Kerr , Thomas Mann , Erich Maria Remarque and others are depicted as "piglets" hanging on the publisher's drip .

This inflammatory propaganda prepared the persecution of the Jews during the Nazi era, which began with the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor on January 30, 1933 and was steadily increased from the " Jewish boycott " (April 1, 1933). Since the " Laws for the Protection of German Blood " of 1935, sexual contact between Jewish and non-Jewish Germans was strictly forbidden and threatened with imprisonment for the male partner. Non-Jewish women who were accused of such “racial disgrace” were publicly humiliated as “Jewish whores”, for example by hanging signs around their necks that read: “I am the biggest pig in the area and only get involved with Jews.” Survivors inmates of Nazi concentration camps tell of sadistic rituals of some overseer of the SS : They forced Jewish prisoners about to undress and call of a tree down, "I'm a dirty Jewish pig!" the non-Jew Carl von Ossietzky was weeks of SA ists in Concentration camp Sonnenburg insulted and tortured as "Judensau" and "Saujude" before he was murdered.

Karena Niehoff, a " half-Jewish ", was the main witness in the 1950 trial against Veit Harlan , the director of the Nazi propaganda film Jud Süss from 1940. She incriminated him with the statement that he had personally tightened the draft script in an anti-Semitic way. She was then insulted and threatened by the audience as a “Jewish pig”, so that she needed police protection and the public was henceforth excluded from the trial. The threats against her, further trial circumstances and the acquittal for Harlan were noticed in the media worldwide and often viewed as a sign of a lack of coming to terms with the past in Germany in the post-war period , so that Chancellor Konrad Adenauer publicly regretted the incident.

present

Sculptures

The handling of historical representations of Jews is controversial. Preservationists and historians also want to document extremely offensive motifs as evidence of the time in their architectural context at the time. Critics want to have these pictures removed because they see in them a lack of sensitivity to the feelings of today's Jews and a lack of turning away from anti-Semitism.

In 1988, the sculptor Wieland Schmiedel from Crivitz (Mecklenburg) designed a commemorative plaque on behalf of the parish council of the Wittenberg town church, which was set into the ground below the relief of the Jews. She refers to the Holocaust as a historical consequence of this hatred of Jews. Your step plates should cover something that oozes out of all joints. The text border quotes in Hebrew the psalm verse Ps 130.1 LUT (“From the depths I call, Lord, to you”) and the Berlin writer Jürgen Rennert : “God's real name, the reviled Shem Ha Mphoras, which the Jews before the Christians held almost inexpressibly holy, died in six million Jews under the sign of the cross. ”On April 24, 1990, the Synod of the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg adopted this initiative and recommended:“ If the works of art remain in their place, the Observers are made aware of the guilt and concern of the church through references [...] and are guided to a new perspective. "

Some critics find the remaining representations unbearable and demand that they be removed or that they be clearly distanced in accompanying texts. Thus, the performance artist themed Wolfram P. Kastner the Judensau the choir of Cologne Cathedral at a protest in 2002 as "a model for the production of images of violence in our minds." The cathedral builder Barbara Schock-Werner rejected his suggestion to use a distancing plaque to "draw attention to the defamatory anti-Jewish mockery" : the valuable work of art was invisible to visitors anyway; Nor do they want to point it out elsewhere in the cathedral. In the cathedral catalog, an art historian classifies the representation of Jews in the choir stalls as evidence of medieval anti-Judaism, "although the Jews were under the protection of the archbishop".

On March 30, 2005, those responsible put a notice board in Regensburg Cathedral: “The sculpture as a stone testimony to a bygone era must be seen in connection with its time. Its anti-Jewish content is disconcerting for today's viewer. ”The text was a compromise between the Diocese of Regensburg , the Ministry of Education and the State Association of the Jewish Religious Communities in Bavaria . A counter-draft by Wolfram Kastner from May 11, 2005, which named Christian complicity, was removed by community representatives from the church wall within a few hours.

In Bayreuth, pastor Klaus Rettig has been demanding the removal of the Judensauskulptur since 2000. The parish council of the Bayreuth city church wanted to leave the barely recognizable representation in its place and decided at the end of October 2004 to put a plaque underneath. A week later, strangers smashed the sculpture. The memorial plaque was installed in 2005 and bears the inscription: “The stone testimony of hatred of Jews on this pillar has become unrecognizable. All hostility to Judaism is gone forever. "

In Nuremberg, the church council of St. Sebald passed a declaration on September 15, 2005, the 70th anniversary of the Nuremberg Laws, with the wording: "The" Judensau "derogatory image from the late Middle Ages expresses the hatred of Jews that prepared the Shoah. In the same demon, the Jewish citizens of Nuremberg were despised and vilified, expelled and destroyed until the 20th century. We bow in shame to the millions of victims of hatred of Jews. We ask her and our common God for forgiveness. "

Since autumn 2016, the London theologian Richard Harvey has been calling for the Wittenberg Judensauskulptur to be accepted on the Internet for the 2017 Reformation anniversary . His petition quickly found 5,000 supporters. The Central Council of Jews in Germany supported the acceptance and found the explanatory panel to be inadequate. The Protestant regional bishop Ilse Junkermann rejected the acceptance: The church had to "keep this wound in our own history open" and could not correct it itself. The sculpture had to stand as a "reminder and warning sign" to show that the church does not want to gloss over anything, but rather hopes for the power of forgiveness. The floor slab under the relief provides the necessary classification. Starting in May 2017, an ecumenical “alliance for the acceptance of the 'Judensau' in the Reformation year 2017” demonstrated every Wednesday on the Wittenberg market square: The sculpture hinders reconciliation should be brought to a museum and serve as an enlightenment there. Members of the right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland then published a petition to preserve the sculpture.

On the occasion of the right-wing extremist march and murder in Charlottesville (August 11th / 12th, 2017), Morten Freidel (FAZ) referred to the missing information boards for some sculptures of Jews, including in Calbe, Eberswalde and Cologne. He gave the arguments of affected Jews in favor of preserving the sculptures. Then Salomon Korn , Vice President of the Central Council of Jews, pleads for "clarification before elimination". Active engagement with historical anti-Semitic phenomena and people is more important than their mere removal from public space. One can learn more about it in the original context of churches than in the artificial context of a museum. The sculptures should only be removed in extreme exceptional cases. Josef Schuster (President of the Central Council) wanted to give church parishes the choice of either removing the sculptures or putting up clear plaques to explain. Other German Jews wanted to keep the abusive sculptures in churches so that they would not be relieved of their responsibility for their history. The distance would make the genuine anti-Judaism inherent in Christianity invisible.

On May 24, 2019, the Dessau Regional Court dismissed the action brought by Michael Düllmann, a member of the Berlin Jewish Community, to remove the Wittenberger Judensau because the relief was part of the historic monument of the city church and neither as a disregard for the Jews in Germany nor as an insult to the Plaintiff is to be understood. In June 2019, however, the plaintiff appealed to the Naumburg Higher Regional Court. The President of the EKD Synod Irmgard Schwaetzer and Regional Bishop Friedrich Kramer proposed in May 2019 that the sculpture be removed from the church facade and integrated into a new memorial in front of the church, which was designed together with the Jewish institutions and supported by the parish, the municipality and should be supported by the district. Kramer argued that the sculpture remains an insult even with the comment board. Schwaetzer said that the inscription added later expresses “pure hatred of Jews”, to which the Protestant Christians “have to behave again today”. They should "also think of the feelings our Jewish brothers and sisters have when they see this historical place".

The Naumburg Higher Regional Court rejected Düllmann's appeal on February 4, 2020 because the town church community had integrated the relief into a memorial ensemble and unmistakably distanced itself from the anti-Judaism of sculpture and Luther's writings with an information board. The plaintiff's wish to move the sculpture to a museum contradicts his argument that even an insult with commentary remains an insult. The danger of misunderstanding the sculpture as part of the Christian proclamation no longer exists thanks to the memorial ensemble. Because of the importance of the case for the civil law handling of the degradation of groups of people, however, the court allowed an appeal on appeal to the Federal Court of Justice. The plaintiff Michael Düllmann announced that he would continue to take legal action against the relief, "if necessary to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg". The Federal Government Commissioner for Anti-Semitism, Felix Klein , again demanded that the Wittenberg vicious sculpture be removed from the town church and brought to the museum. In contrast, the anti-Semitism commissioner in Saxony-Anhalt, Wolfgang Schneiß, advocated a “careful further development” of the memorial ensemble, such as an artistic intervention as part of the nationwide remembrance of “1,700 years of Jewish life in Germany” planned for 2021 and an out-of-court settlement of all parties to the dispute on this redesign of the memorial. At the St. Stephani Church in Calbe (Saxony-Anhalt) 2019/2020 fourteen fake historic gargoyles from the 15th century removed to have it restored them. According to Pastor Jürgen Kohzt, the “Judensau” sculpture underneath should not be re-attached because it is still “insulting” today. Behind this is the opinion that Jews are undesirable.

Insults

The insults "Judensau", "Judenschwein" or "Saujude" are mainly used in neo-Nazism to this day. In federal German criminal law, they are clearly punishable offenses. They go beyond ordinary xenophobia as they deliberately portray, belittle and threaten people in the anti-Semitic tradition as belonging to an inferior race. Such anti-Semitic abuse is an integral part of the desecration of Jewish cemeteries . Such crimes have increased in Germany since 1990. For example, the joint grave of Bertolt Brecht and his wife Helene Weigel , who was of Jewish origin, was smeared with the slogan “Pig-Jew” shortly after the Berlin Wall opened in 1989. On the night of April 20, 1992, the anniversary of the “ Führer birthday ”, neo-Nazis threw half a pig's head into the front garden of the Erfurt synagogue . A neo-Nazi and three skinheads repeated this on July 20, 1992, after the death of Heinz Galinski , with two halves of the pig's head. The attached note read: "This pig Galinski is finally dead. There must be more Jews."

The memorial for deported Jews in Berlin-Grunewald was desecrated with pigs' heads in October 1993. In the same year, a skinhead in Marl cursed a homeless man as a “Jewish pig” and beat him so severely that he passed out and died three months later in the hospital without coming to. The perpetrator was sentenced to a 15-month suspended prison sentence for dangerous bodily harm. In 1997, the right-wing extremist group Blood and Honor in Altenburg , Thuringia, called for the murder of seven people with a death list and described one of them, the Lord Mayor, as a “corrupt Jewish pig”.

In October 1998, during the public debate between Martin Walser and Ignatz Bubis about the alleged "moral club Auschwitz", neo-Nazis drove a piglet with a painted Star of David and the name of Ignatz Bubis across Alexanderplatz in Berlin. This degradation was directed at a representative of the Jews in Germany, whom neo-Nazis often attacked. Meir Mendelssohn , who had doused Bubis's grave in Israel with black paint, asked the audience at a theater evening organized by Christoph Schlingensief in the Volksbühne Berlin on November 22, 1999 , “... to say the word Judensau, completely normal and completely natural . ”He was then charged with sedition.

In June 2006, the Swiss right-wing extremist Pascal Lüthard insulted a restaurant guest who wanted to mediate a brawl provoked by neo-Nazis as a “Jewish pig”. Lüthard was then sentenced to a fine for violating the Swiss criminal law on racism . The appeal for a revision, according to which he had insulted only one person, was rejected by the higher court: he was aware of the Jewish identity of the person insulted, and the specific statement therefore deliberately reduced an ethnicity and religious affiliation beyond an individual judgment of unworthiness. On April 16, 2010, a 17-year-old native Israeli, the grandson of a Holocaust survivor from the Warsaw ghetto , was severely physically abused by a right-wing extremist classmate in Laucha without warning and insulted as a "Jewish pig". The family, who have lived there since 2002, considered leaving Germany again because of the incident.

Footballers and referees who are regarded as Jewish are still often insulted as "Judensau" in Germany. For example, the footballers of TuS Makkabi Berlin were increasingly abused and physically threatened by right-wing spectators during a game in October 2006 until they left the pitch together. All of the German-Jewish clubs affiliated with Makkabi Germany then agreed to stop games in the event of such incidents in the future and to bring them to sports and criminal courts. This sparked a nationwide debate about anti-Semitism in German football. In December 2006 the German Football Association (DFB) and the DFL German Football League set up a joint task force against violence, racism and xenophobia . In 2008, the DFB included "insults (Section 185 StGB) for racist or xenophobic motives" as a reason for the clubs' permanent stadium bans.

Some anti-Semitic Muslims abuse Jews as “monkeys and pigs”. They refer to three suras of the Koran (2.65; 5.60; 7.166), according to which Allah is said to have transformed wicked Jews into monkeys and / or pigs. Similar to prophetic biblical passages, the suras are interpreted as time-related reproaches to the majority of Jews for not being godly. In 2003, Islamic theologians recommended that these passages no longer be used against today's Jews.

literature

to medieval representations

- David Kaufmann : The sow from Wittenberg. In: Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums . 54. Jg. 1890, p. 614 ff. (Also in: Gesammelte Schriften. Volume 1, Frankfurt am Main 1908, p. 161 ff .; digitized version ).

- Bernhard Blumenkranz : Jews and Judaism in Medieval Art. Kohlhammer, 1965.

- Isaiah Shachar : The Judensau. A Medieval Anti-Jewish Motif and its History. Warburg Institute, London 1974, ISBN 0-85481-049-8 , pdf (authoritative monograph for research).

- Wilfried Schouwink: The wild boar in God's vineyard. For the representation of the pig in literature and art of the Middle Ages. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1985, ISBN 3-7995-4016-4 , pp. 75-88.

- Thomas Bruinier: The "Judensau". A symbol of hatred of Jews and its history. In: Forum Religion. Kreuz-Verlag Breitsohl, Stuttgart 1995, 4, pp. 4-15, ISSN 0343-7744 .

- Claudine Fabre-Vassas: The Singular Beast. Jews, Christians, and the Pig. Columbia University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-231-10366-2 (English).

- Heinz Schreckenberg : The Jews in European Art. A historical picture atlas. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-525-63362-9 , pp. 343-349 (“The 'Judensau' motif”).

- Petra Schöner: Images of Jews in German single-sheet printing during the Renaissance. A contribution to imagology. Valentin Koerner, Baden-Baden 2002, ISBN 3-87320-442-8 , pp. 189-208 ( review ).

- Hermann Rusam: "Judensau" representations in the plastic art of Bavaria. A testimony to Christian hostility towards Jews. In: Encounters. (Special issue March 2007), ISSN 1612-4340 .

- Birgit Wiedl: Laughing at the Beast. The Judensau. Anti-Jewish Propaganda and Humor from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Period. In: Albrecht Classen (Ed.): Laughter in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times. Epistemology of a Fundamental Human Behavior, its Meaning, and Consequences. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-024547-9 , pp. 325–364. ( Digitized version )

to anti-Semitic cartoons

- Matthias Beimel: The caricature as a substitute act. Anti-Semitism in Nazi propaganda and its role models. In: Learning History. Friedrich, Velber 3/1990, 18, pp. 28-33, ISSN 0933-3096 .

- Eduard Fuchs : The Jews in the caricature. A contribution to cultural history. (Munich 1921) Reprint, Ehv-History, 2013, ISBN 3-95564-424-3 .

- Angelika Plum: The caricature in the field of tension between art history and political science. An iconological study of the enemy in caricatures. Reports from art history. Shaker, Aachen 1998, ISBN 3-8265-4159-6 .

- Stefan Rohrbacher , Michael Schmidt: Images of Jews. Cultural history of anti-Jewish myths and anti-Semitic prejudices. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1991, ISBN 3-499-55498-4 .

- Julius H. Schoeps , Joachim Schlör (ed.): Images of hostility towards Jews. Anti-Semitism, Prejudice and Myths. Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-8289-0734-2 .

- Michael Wolffsohn : The picture as a source of danger and information. From the "Judensau" to the "Nathan" to the "Striker" and to Nachmann. In: Uwe Backes , Eckhard Jesse , Rainer Zitelmann (eds.): The shadows of the past. Impulses for the historicization of National Socialism. Ullstein, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-548-33161-0 , pp. 522-542.

- Josef Wirnshofer: A mess . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin , December 22, 2017, pp. 18–23. ( Link , with photos from Cologne, Regensburg, Wittenberg, Nuremberg, Bad Wimpfen, Calbe and Xanten)

Web links

- Judensau in Wiener Neustadt with picture

- Erfurt relief with picture

- Andrea-Martina Reichel: The clothes of passion. For an iconography of the costume. (PDF, pp. 122–130 and appendixes No. 155 and 156) Humboldt University Berlin, January 8, 1960

Single receipts

- ↑ Hermann Rusam: "Judensau" representations in the plastic art of Bavaria. A testimony to Christian hostility towards Jews. In: Evangelical Lutheran Central Association for Encounters between Christians and Jews (ed.): Encounters. Journal for Church and Judaism 90/2007, special issue. ISSN 0083-5579 , p. 3.

- ↑ Main sources: Isaiah Shachar: The Judensau (1974); Wilfried Schouwink: The wild boar in God's vineyard (1985); in individual cases local church leaders, local history or museum descriptions, see sources in Wolfram Kastner: Christliche Sauerei (list of individual locations on the right).

- ^ A b Louis Maeterlinck: Les miséricords d'Aerschot (Fin du XVe siècle). In: the same: Le genre satirique, fantastique et licencieux dans la sculpture flamande et wallonne. Les miséricordes de stalles. Art et folklore. Jean Schemit, Paris 1910, pp. 151–174, here pp. 160–161, digitized .

- ↑ a b Isaiah Shachar: The Judensau, pp. 40, 84 (footnote 280), plate 36b.

- ↑ Dorothea Schwinn Schürmann, in: Hans-Rudolf Meier , Dorothea Schwinn Schürmann et. al .: Das Basler Münster, Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Basel-Stadt Vol. X , Basel 2019, ISBN 978-3-03797-573-2 , p. 306, fig. 373.

- ↑ Gerhart von Graevenitz, Stefan Rieger, Felix Thürlemann : The inevitability of pictures. Narr, 2001, ISBN 3-8233-5706-9 , p. 109 .

- ^ Photographic illustration of the gargoyle on the south-east choir of Cologne Cathedral in Wolfram P. Kastner's Christian Mess .

- ↑ Ulrike Brinkmann, Rolf Lauer: Representations of Jews in Cologne Cathedral . In: Barbara Schock-Werner, Klaus Hardering (ed.): Kölner Domblatt 2008. Yearbook of the Central Cathedral Building Association. tape 73 . Verlag Kölner Dom, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-922442-65-3 , p. 27-32 .

- ↑ The "Judensau" remains? Heise, June 4, 2019

- ↑ Isaiah Shachar: The Judensau. A Medieval Anti-Jewish Motif and its History , Warburg Institute, London 1974, pp. 19f.

- ↑ Description of the building sculpture of the "Judensau" sculpture on the official website of the Sankt-Sebald-Kirche .

- ↑ Hermann Rusam: "Judensau" representations in the plastic art of Bavaria. A testimony to Christian hostility towards Jews , In: Encounters. (Special issue March 2007), p. 20.

- ^ Eduard Fuchs: The Jews in the cartoon , reprint 2013, p. 117 f .

- ↑ Hermann Rusam: "Judensau" representations in the plastic art of Bavaria. A testimony to Christian hostility towards Jews , In: Encounters. (Special issue March 2007), p. 28.

- ↑ Bernd Iben, magazine "GROSSTIERPRAXIS" 05/2009, Witzenhausen: Pearls before the sows (1st part). Humans in ambivalence to pigs (pdf, image No. 10: Judensau Xantener Dom, p. 186; 1.6 MB).

- ↑ Donald Guthrie, J. Alec Motyer: Commentary on the Bible: AT and NT in one volume. R. Brockhaus, 2012, ISBN 978-3-417-24740-4 , p. 178 .

- ↑ Matthias Krieg (Ed.): Explains: The commentary on the Zurich Bible, Bible and commentary in 3 volumes. Theologischer Verlag, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-290-17425-5 , p. 273 .

- ↑ Othmar Keel, Max Küchler, Christoph Uehlinger: Places and landscapes of the Bible. A handbook and study guide to the Holy Land. Volume 1: Geographical-historical regional studies. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1984, ISBN 3-525-50166-8 , p. 122 .

- ↑ Andreas Brämer: The 101 most important questions. Judaism. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59984-2 , p. 49 .

- ^ Matthias Klinghardt: Legion pigs in Gerasa: Local color and historical background from Mk 5.1–20. In: Journal for New Testament Science 98/2007, pp. 28–48.

- ↑ Peter Fiedler: Theological Commentary on the New Testament (ThKNT): The Gospel of Matthew. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-17-018792-9 , p. 15 .

- ↑ Petra Schöner: Images of Jews in German single-sheet printing of the Renaissance. P. 189ff.

- ^ Stefan Rohrbacher, Michael Schmidt: Judenbilder. Rowohlt, 1991, ISBN 3-499-55498-4 , p. 161.

- ↑ Isaiah Shachar: The Judensau , 1974, pp. 22f.

- ↑ Isaiah Shachar: The Judensau , 1974, p. 74.

- ↑ Thomas Dietz (Mittelbayerische Zeitung, October 12, 2013): Why the "Judensau" is a she-wolf.

- ↑ Max Sebastián Hering Torres: Racism in the premodern: The "purity of blood" in Spain in the early modern period. Campus, 2006, ISBN 3-593-38204-0 (on the term Marranos : p. 16, fn. 7).

- ↑ Angelika Plum: The caricature in the field of tension between art history and political science: An iconological study of enemy images in caricatures. 1998, p. 81ff.

- ^ Gerhard Langemeyer: Means and motifs of the caricature in five centuries. Prestel-Verlag, 1984, ISBN 3-7913-0685-5 , p. 151.

- ↑ Alex Bein: The Jewish question: Biography of a world problem. Volume 2, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1980, ISBN 3-421-01963-0 , p. 74.

- ↑ Alex Töllner: Judensau. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus , Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. Walter de Gruyter, 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , pp. 159f .

- ↑ Heinz Schreckenberg: The Jews in European Art. Göttingen 1996, p. 343ff.

- ↑ Wilfried Schouwink: The wild boar in God's vineyard. P. 88.

- ↑ Weimar Edition Volume 53, p. 600ff; Original print of Luther's “Schem Hamphoras”, full text .

- ↑ Folker Siegert: Israel as a counterpart: From the ancient Orient to the present. Studies on the history of an eventful coexistence. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, ISBN 3-525-54204-6 , p. 299 and fn. 39.

- ↑ a b Debate about the removal of the Wittenberg "Judensau" from the church facade. epd, May 28, 2019

- ^ Wilhelm Güde: The legal position of the Jews in the writings of German jurists of the 16th and 17th centuries. J. Thorbecke, 1981, ISBN 3-7995-6026-2 , p. 10.

- ↑ quoted from Petra Schöner, p. 197; Full text in: Dieter Wuttke: Fastnachtsspiele des 15th and 16th centuries , Reclam, Ditzingen 1986, ISBN 3-15-009415-1 .

- ↑ Ursula Schulze: Jews in the German literature of the Middle Ages. Religious concepts - enemy images - justifications. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-11-093304-7 , p. 163 .

- ^ Stefan Rohrbacher, Michael Schmidt: Judenbilder. P. 160.

- ^ Stefan Niehaus (ed.): Ludwig Achim von Arnim: Texts of the German table society. De Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-484-15611-2 , p. 111 f. (Arnim), 371 (Goethe) and 498 (Schudt). All quotes from Jutta Ditfurth : The Baron, the Jews and the Nazis. Noble anti-Semitism. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-455-50394-4 , p. 43 f. and pp. 324 f., footnotes 75-79.

- ^ Karl Friedrich August Müller (ed.): Bayerische Landbötin No. 132, November 2, 1833, p. 1150 .; Nikolaus von Weis (Ed.): Der Katholik , Vol. 60, Speyer 1836, Appendix V, S. LXII . The existence of older sources is possible.

- ↑ Wolfgang Duchkowitsch: Media: Enlightenment - Orientation - Abuse. From the 17th Century to Television and Video , Volume 3 of the Communication Series . Time. Raum , Wien / Berlin 2014, p. 14 and p. 60 ( limited preview in the Google book search, see also p. 60)

- ^ Eduard Fuchs: The Jews in the cartoon reprint 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ Eduard Schneider: Shadows of the past and the present. Simowa, 1999, ISBN 3-9521463-9-0 , p. 12.

- ^ Eduard Fuchs: The Jews in the Caricature , reprint 2013; Julia Schäfer: Measure - drawn - laughed at. Campus, 2005, ISBN 3-593-37745-4 .

- ↑ Ernst Toller: A youth in Germany . Text based on the 1936 edition by Querido Verlag, Amsterdam, Reclam Leipzig 1990, ISBN 3-379-00558-4 , p. 266.

- ↑ Dieter Heimböckel: Walther Rathenau and the literature of his time: studies on work and effect. Königshausen & Neumann, 1996, ISBN 3-8260-1213-5 , pp. 354 - 358

- ↑ Carsten Pietsch: The Unleashed Hate: Anti-Jewish Stereotypes in the caricatures and inflammatory articles of the "Striker" (PDF, 758 kB; University of Oldenburg, WS 2001/2002).

- ↑ Paul Egon Hübinger: Thomas Mann, the University of Bonn and contemporary history: three chapters of the German past from the life of the poet 1905–1955. Oldenbourg, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-486-44031-4 , p. 138; Hinrich Siefken: Thomas Mann's “Service to Time” in the years 1918–1933. In: Thomas Mann Jahrbuch 10 (1997), pp. 167-185, here: p. 172 .

- ^ Christian Zentner : Germany 1870 to today: Pictures and documents. Südwest-Verlag, 1970, p. 296; Micha Brumlik, Rachel Heuburger, Cilly Kugelmann: Travels through Jewish Germany. DuMont, 2006, p. 404.

- ↑ David A. Hackett: The Buchenwald Report. Report on the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar. Beck, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-406-47598-1 , p. 187 .

- ↑ Elke Stenzel (Ed.): "Give the Nazis a resounding slap in the face": Contemporary witnesses remember. Frank & Timme; 2009, ISBN 3-86596-254-8 , p. 137 .

- ↑ Torben Fischer, Matthias N. Lorenz (Ed.): Lexicon of "Coping with the Past" in Germany. Debate and discourse history of National Socialism after 1945. Transcript, 2nd edition, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89942-773-8 , p. 97 .

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk, March 31, 2005: Correction in the name of political correctness (interview with Achim Hubel from the Chair for Monument Preservation in Bamberg)

- ^ Albrecht Steinwachs, Stefan Rhein, Jürgen M. Pietsch: The city church of Lutherstadt Wittenberg. Edition Akanthus, 2000, ISBN 3-00-006918-6 , p. 107 .

- ↑ Oliver Gußmann: The so-called "Judensau" . ( Memento from August 22, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: Encounters. Journal for Church and Judaism. 84/2001, pp. 26–28, revised in 2003; Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation Palatinate: The so-called "Judensau" motif - brief information.

- ↑ Marten Marquardt: Enmity against Jews in Christian art using the example of the Cologne Judensau. (Lecture on October 7, 2002)

- ^ Letter from the cathedral building administration of the High Cathedral in Cologne to Wolfram Kastner, 2002 .

- ↑ Marc Steinmann, art historian: Wange NC west, Judensau - choir stalls north. (Cologne cathedral)

- ↑ Netzeitung, March 29, 2005: Sign on Regensburg Cathedral - dispute over “Judensau” continues

- ↑ Wolfram P. Kastner, Günter Wangerin: “Judensau” sculpture: panel on Regensburg Cathedral. HaGalil, May 11, 2005

- ↑ Wilfred Engelbrecht: The Bayreuth city church. Our lis goczhawss sant Marie magdalene. History of the oldest building in the city. Bayreuther Zeitlupe Verlag, Bayreuth 2017, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Bernd Mayer: "Judensau" - disgrace of Christians. How can communities deal with the medieval mocking sculptures? ( Memento from April 21, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Sunday newspaper Bavaria, March 13, 2005.

- ^ Declaration by the Church Council of St. Sebald on September 15, 2005 - 70 years after the “Nuremberg Laws” were enacted.

- ↑ MDR, October 7, 2016: Controversy over image at Stadtkirche Wittenberg: Church wants to keep "Judensau" relief. ( Memento from June 23, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Corinna Nitz (Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, May 17, 2017): Silent vigil Alliance protests against Jewish pig mockery.

- ↑ Morten Freidel: A big mess. Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung , August 20, 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Justice: Appeal against "Judensau" judgment. Jewish General, June 26, 2019

- ↑ "Judensau" - vile sculpture may remain at the city church. Evangelisch.de, February 4, 2020

- ↑ Debate about anti-Jewish portrayals of churches continues. Evangelisch.de, February 5, 2020

- ^ Klaus Hillenbrand: In a pinch to Strasbourg . The daily newspaper , February 5, 2020, accessed on June 2, 2020.

- ↑ Axel Töllner: Judensau. In: Wolfgang Benz, Brigitte Mihok (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus, Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-598-24074-4 , p. 159 .

- ^ Juliane Wetzel: Anti-Semitism as an element of right-wing extremist ideology and propaganda. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Antisemitism in Germany. On the timeliness of a prejudice. dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-04648-1 , p. 106.

- ↑ Werner Bergmann, Rainer Erb: Neo-Nazism and right-wing subculture. Metropol, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-926893-24-9 , p. 38; Frank Jansen , Johannes Radke, Heike Kleffner , Toralf Staud (Tagesspiegel, May 31, 2012): Deadly hatred: 149 deaths from right-wing violence .

- ↑ Johannes Jäger: The right-wing extremist temptation. Lit Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5722-0 , p. 139 .

- ^ Anton Maegerle (Material Service Evangelical Working Group Church and Israel in Hesse and Nassau): Anti-Semitism in Germany - a chronicle .

- ^ Constitutional Protection Report 2004: The Significance of Anti-Semitism in Current German Right-Wing Extremism ( Memento of March 11, 2011 on WebCite ) (pdf).

- ^ Marlies Emmerich: Schlingensief and Mendelssohn indicated. Incitement of the people in the Volksbühne? In: Berliner Zeitung . November 24, 1999, accessed June 10, 2015 .

- ↑ Racism judgment revised: Higher court partially overturns racism judgment against former Pnos president in: Humanrights.ch .

- ↑ Alexander Schierholz (Frankfurter Rundschau, May 18, 2010): Saxony-Anhalt: An attack in Laucha .

- ↑ Gerd Dembowski, Michael Preetz u. a .: crime scene stadium. Anti-Semitism, Racism and Sexism in Football. PapyRossa, 2002, ISBN 3-89438-238-4 , p. 83; Stefan Mayr, Andreas Lüdke: You whistle for your ass !: Soccer abuse from amateur to Zidane's sister. Bastei Lübbe, 2016, p. 141 .

- ^ Netzeitung, October 12, 2006: Nazi slogans against Jewish soccer players in Berlin ( Memento from March 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Amballbleiben.org, August 21, 2007: “We will continue to fight against any kind of anti-Semitism” - Interview with Roger Dan Nussbaum from Makkabi Germany ( Memento from June 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Michaela Glaser, Gabi Elverich (ed.): Right-wing extremism, xenophobia and racism in football. Prevention experiences and perspectives (PDF)

- ↑ DFB Prevention & Security Department, March 2008: Guidelines for the Uniform Handling of Stadium Bans , Item 13 (PDF; 123 kB) ( Memento from May 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Handbook of Antisemitism: Anti-Semitism in Past and Present, Volume 1: Countries and Regions. De Gruyter / Saur, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-598-24071-6 , p. 148.

- ↑ Hanno Loewy (ed.): Rumors about the Jews: anti-Semitism, philosemitism and current conspiracy theories. Klartext, 2005, ISBN 3-89861-501-4 , pp. 152 and 168, fn. 3.