Battle of Jena and Auerstedt

| date | October 14, 1806 |

|---|---|

| place | Jena and Auerstedt , Thuringia |

| output | French victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Jena: |

Jena: |

| Troop strength | |

|

123,200 men Jena: 95,900 men 180 cannons Auerstedt: 27,300 men 44 cannons |

102,800 men Jena: 53,000 men 215 cannons Auerstedt: 49,800 men 230 cannons |

| losses | |

|

14,920 dead and wounded |

33,000 dead, wounded and prisoners |

Schleiz - Saalfeld - Jena and Auerstedt - Lübeck - Greater Poland - Czarnowo - Golymin - Pułtusk - Dirschau - Prussian Eylau - Ostrolenka - Stolp - Danzig - Kolberg - Guttstadt - Heilsberg - Friedland

The battle of Jena and Auerstedt (also double battle of Jena and Auerstedt ; or Auerstädt in older sources) took place during the Fourth Coalition War on October 14, 1806 near the places Jena and Auerstedt .

The Prussian army suffered a heavy defeat against the French troops. On October 14, 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte and his numerically superior main army defeated a Prussian- Saxon corps near Jena, while at the same time, about 25 kilometers away, Marshal Davout and his corps were able to defeat the numerically superior Prussian main army under the Duke of Braunschweig near Auerstedt . In older sources, instead of “Battle of Jena and Auerstedt”, it also says “Double Battle of Jena and Auerstedt”. Both terms do not indicate that both the French and the Prussians had next to no knowledge of the battles that took place in parallel. However, neither of the two battles can be viewed to the exclusion of the other.

prehistory

After the overwhelming victory over the allied armies of Russia and Austria in the Battle of Austerlitz on December 2, 1805, Napoleon increasingly dictated European politics and division. The Peace of Pressburg on December 26, 1805, which Emperor Franz II had to conclude, included extensive territorial losses by the Habsburgs in southern Germany and Italy in favor of France and its allies such as Bavaria, Baden, Württemberg and the Kingdom of Italy . In the reorganization of Europe by Napoleon, Bavaria and Württemberg were upgraded to kingdoms, Baden , Hesse and Berg to grand duchies. Napoleon left his troops in Central Europe and Italy in order to underline his policy with military pressure. Napoleon's brothers Joseph and Louis were appointed kings of Naples (March 1806) and of Holland (May 1806), respectively . Napoleon's brother-in-law Murat became Grand Duke von Berg . Under French protectorate, the Rhine Confederation was founded on July 26th by 16 German principalities that left the German Empire. On August 6, 1806, at Napoleon's pressure, Francis II resigned the imperial dignity of the Holy Roman Empire. The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation ceased to exist.

Napoleon also had increasing influence on Prussian politics. In order to achieve Prussia's neutrality in the conflict with England, Austria and Russia, Napoleon offered the Electorate of Hanover as a pledge. When the French 1st Corps under Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte , who had been in charge of Hanover since June 1804, crossed the border of the Prussian margraviate of Ansbach on the train south on the orders of Napoleon , the abandoned Hanover was occupied by the Prussians and the Russians were allowed to march through Prussian territory. Prussia actually wanted to demand that Napoleon separate the crowns of France and Italy and recognize the neutrality of Switzerland and the Netherlands. After the Battle of Austerlitz, however, this did not happen again. The Prussian cabinet minister Haugwitz , who also had the secret instructions to keep peace by his king, agreed on December 15, 1805 in Schönbrunn, where Napoleon resided, to an alliance treaty with France. This also envisaged the transfer of Prussian possessions such as the Margraviate of Ansbach to Bavaria, which was allied with France, and the Duchy of Kleve and the Principality of Neuchâtel (Neuchâtel) to France. In return, Prussia was to receive Hanover and, for Ansbach, a small region near Bayreuth.

The possession of Hanover, which was actually in personal union with Great Britain , posed a problem for Prussia, as it would have been against England. Prussia tried to present the property only as a temporary administration or pledge, until Hanover could really get it in a peace treaty, and also wanted the land cedings to be postponed. However, Napoleon threatened Prussia in renegotiating more stringent conditions than before. The territorial transfers should take place more quickly, with Ansbach being handed over to Bavaria without consideration and the county of Valangin also falling to France. In this treaty of Paris on February 15, 1806, Hanover had to be captured with full sovereignty and Prussia was to close all ports to English ships. As a result, England and Sweden declared war on Prussia and fought and destroyed the Prussian merchant fleet. With further pressure Napoleon also managed to force the Prussian Foreign Minister Hardenberg, whom he considered to be an opponent, out of office and to have him replaced by Haugwitz. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon demanded the Abbeys Essen , Werden and Elten, which belonged to Prussia, for the newly created Grand Duchy of Berg from the Duchies of Kleve and Berg , and annexed - ignoring Prussian protests - the Wesel fortress . When the Rhine Confederation was founded shortly afterwards, Napoleon brought up a North German Confederation under Prussia's leadership, even with an imperial crown for the Prussian king. Prussia's efforts were not given particular support, nor were there any great successes.

After the death of William Pitt , who was a staunch opponent of Napoleon, the more moderate Whig Charles Fox took over the office of British Prime Minister , and France and England entered new, secret peace negotiations. When Prussia learned that France had proposed to England that Hanover be returned to the United Kingdom, it mobilized its military in early August. Prussia's ultimatum of August 26, 1806, that Napoleon should return his troops across the Rhine by October 8, finally prompted him to act.

requirements

The Prussian army had not developed much since the Silesian Wars . She adhered to the traditional order of line tactics , only divided the troops into divisions shortly before the war and was not used to the interaction between the modern general staff and operations management. The experiences from the campaigns on the Rhine (1792–1795) and in Poland (1794/1795) had largely been suppressed by the old generals , especially since the Prussian army had met a revolutionary army in the west in the tactical-strategic transition. In addition, the younger generation of officers in the army in Prussia still had little influence. In addition, the Prussian army was a standing army of the old type, in which the officers were rarely promoted according to their performance, but rather according to their seniority ( seniority ). The equipment was also inadequate, as many items were saved as a result of the company economy.

The Napoleonic army, on the other hand, had war experience and was highly motivated by previous victories. It consisted of conscripts who were conscripted annually , although Napoleon had to allow numerous exemptions from compulsory military service out of consideration for the French upper bourgeoisie (“notables”) who supported his rule, reminiscent of “exemptions” (withdrawals from compulsory military service) of the Prussian cantonal system. Tactically, these troops were up to date by flexibly combining rifle tactics (see infantry , volley ), column tactics and line tactics . A more flexible baggage and catering system made the French army more agile and faster. Of course, it often degenerated into looting, which put a heavy burden on the civilian population. French subaltern officers had no horses; the soldiers had winter coats instead of tents. The French requisitioned on site for a receipt, the Prussians operated with a supply fleet. Napoleon's soldiers were not hindered by a large train and were able to achieve significantly higher marching speeds.

The campaign up to the battles

Napoleon and his troops advanced from the Main through Thuringia to the Prussian capital Berlin . In this way he hoped to force the Prussian army into battle and at the same time cut off the Saxons from their lines of communication. The allied Prussians and Saxons had gathered west of the Saale in order to be able to react flexibly to Napoleon's attack, regardless of whether it would take place east or west of the Thuringian Forest . When they heard of Napoleon's advance from Bavaria , a time-consuming dispute arose among the commanders-in-chief as to whether it was better to gather their forces west (concentration of the armies near Eisenach, Erfurt and Weimar) or east of the Saale in order to find the routes to Berlin and Dresden cover up. General Ernst von Rüchel's sub-army gathered near Hanover and from there drew closer to the main army via Göttingen and Mühlhausen. Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia was to cover the Saale crossing near Saalfeld with an advance guard. On October 10, this corps was wiped out in the battle near Saalfeld . The prince fell in a horse fight.

The day before, Joachim Murat's troops met nearby Prussian and Saxon troops at Schleiz , but were thrown back. Only the intervention of infantry under Marshal Bernadotte decided the fight in favor of the French. They lost around 200 soldiers, while the Prussians lost 500 men to death, wounding and capture. The battle at Schleiz was the first major encounter between Prussian and French troops in this war.

The troops of Napoleon now advanced especially east of the Saale to the north, while the allies gathered on the western side of the river. On October 12th they decided to avoid a battle for the time being and to move the main army quickly north so as not to be cut off from Berlin. The army corps of the Prussian generals Prince zu Hohenlohe and Ernst von Rüchel stopped at Jena and Weimar to cover the march of the main forces under the leadership of the Duke of Braunschweig towards the Saale crossings at Naumburg .

Napoleon's enlightenment also failed completely during these days. He was unsure of where the Allied forces were; he suspected it was near Gera or further north. So he sent Murat's riders partly in the direction of Leipzig and the corps of Davout and Bernadotte to Naumburg. Finally, on the 13th, Lannes discovered the Prussian troops near Jena. Assuming that this was the main allied army, Napoleon concentrated his corps in front of Jena and occupied the city and the important heights, in particular the Landgrafenberg (280 m) and the Windknollen (363 m), from which he determined the strength and position of his opponents scouted. Even though there had been minor skirmishes between Lanne's troops and the Prussians in the afternoon, the latter did not see themselves in danger and the Prussians camped on the plateau. They considered an attack from the side of the Landgrafenberg impossible, u. a. because it was believed that this could not be climbed with cannons from Jena. Napoleon ordered exactly this and his troops worked all night to get the landgrave's guns up.

On the night of the 14th, Davout, who had occupied the Kösener Pass, was ordered to Jena via Apolda. He should head in the direction of the cannon thunder. However, the letter ended:

“When Marshal Bernadotte is with you, you can march together, but the Kaiser hopes that he will be in the position that is assigned to him at Dornburg. - When you are close enough to Jena that you can be heard there, fire a few cannon shots. These will be the signal [to attack] if we are not forced to start earlier. "

This order, which Napoleon wrote around 10 p.m. and which Davout received at 3:00 a.m. on the 14th, shows that Napoleon was not yet sure whether he would attack immediately in the morning or whether the battle would take place later. Probably the combination of the success of getting the cannons on the Landgrave and the surprise advantage let Napoleon start early and he renounced Davouts (about 40–50 km from Jena) and Bernadotte's participation at the start of the battle. Bernadotte, who was in Naumburg but whose troops were already camping on the way to Dornburg, decided to continue via Dornburg.

When the battle began the next morning, Napoleon's main army was facing only the Hohenlohe corps , while the French Davout corps unexpectedly encountered the assembled Prussian-Saxon main army 22 km to the north-east near Hassenhausen . At Dornburg, Bernadotte had the problem of overcoming 80 to 100 meters in altitude under difficult circumstances with his troops from the Saale bridge to Dornburg and subsequently did not reach either battlefield.

The battles

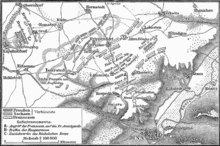

The battle near Jena

Preparation (October 13, 1806)

Up until the day before the battle of Jena, October 13, 1806, a Saxon battalion held the so-called " Landgrafenberg ", a ridge northwest of Jena. It was spread over a length of 2 kilometers and was unable to offer any significant resistance to a French force led by Marshal Lannes . Lannes and his 22,000 soldiers had already crossed the Saale that morning and taken Jena. With its withdrawal, the Saxon battalion gave the French a strategically favorable position. The Prussian commanders, above all the Prince of Hohenlohe , did not worry about this. They thought it was impossible to move artillery up the steep slope. They did not order a counterattack to recapture the "Landgrafenberg". For Napoleon, who arrived with his guards (8,500 men) at 4 p.m. on the Landgrafenberg, the ridge offered a convenient observation point. From here, as long as there was no fog obstructing the view, he could see as far as the Saale valley. At night, Marshal Lannes' corps moved cannons up the mountain on what is now the " Hohen Steiger ". Napoleon himself intervened in the organization when the artillery platoon jammed. The emperor gathered all the nearby French troops on the "Landgrafenberg", with the corps of Soult and Augerau not arriving until the night. Before he went to sleep in the middle of his guard on the south side of the Windknollen , he inspected the individual corps at Jena again.

Starting situation on the morning of October 14th

On the morning of October 14, the day of the battle, Napoleon only faced the Hohenlohe corps. However, Hohenlohe had not concentrated his troops. 22,000 of his soldiers camped at Kapellendorf and 8,000 men at Dornburg . Between Kapellendorf and Dornburg, directly opposite the French troops, there were another 8,000 Prussian soldiers of the corps. It was led by General Tauentzien . Hohenlohe were therefore subordinate to 38,000 soldiers near Jena. The 15,000 men under the leadership of General Rüchel who were still in Weimar were not supposed to reach the battlefield in time. That morning Napoleon had 56,600 men at his disposal; he outnumbered the Prussians. However, he still assumed that he would have to take on the Prussian-Saxon main army, which he estimated to be at least 100,000 men. By 11 o'clock he received reinforcements from two more corps. Napoleon's troop strength was then 96,000 men, but only 54,000 French soldiers were involved in combat operations.

In the morning there was still thick fog over the Landgrafenberg. The poor visibility, as the French General Savary was supposed to record in his memoir, favored the French troops. On the Landgrafenberg, Napoleon's soldiers stood “extremely crowded together” (so Savary). With good visibility they would have made an easy target for the nearby Prussian artillery. According to Savary, any shot by the Prussians could have "hit" and caused "great damage" to the French ranks. The French were only able to form an effective battle formation in the western plain of Jena. Therefore, they had to march down the long, narrow ridge as quickly as possible, before the Prussian soldiers could effectively cordon off the access to the plain.

course

At 4 a.m. Emperor Napoleon held a personal meeting with Marshal Lannes. He gave him final instructions for an attack. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon strengthened the morale of his troops by leaving their ranks and reminding them in a speech of the quick victory in the battle of Ulm against the Austrians last year. A first, short battle occurred shortly before Napoleon's ordered official attack at 6 a.m. Prussian hunter troops opened fire on the French advance troops from Soult . Soult Vortruppe was commissioned by Napoleon for the streets of the mountain ridge into the plane scout . However, due to the poor visibility in the fog, the fire was stopped relatively quickly for the time being. At 6 o'clock Napoleon let the gunfire open on Closewitz. The shelling should prepare for the subsequent storming of the village. Then the soldiers of Marshal Lannes set in motion, where they met the Prussian corps of General Tauentzien, which blocked access to the plain. The visibility was about 100 paces in the persistent fog. Because of these poor visibility, Lannes initially estimated the Prussian division (8,000 men) to be numerically larger than it actually was. It was only when the fog slowly began to dissipate at 8:00 a.m. that Lannes realized the true balance of power. He pushed Tauentzien's troops back to the Dornberg, the highest point on the battlefield, where the soldiers fought another battle at 8:30 a.m.

At this point, the Prince of Hohenlohe was still not prepared for a battle. He assumed that the main French army was marching towards Naumburg to prevent the Prussian soldiers from crossing the Unstrut. Hohenlohe reckoned with a maximum of smaller skirmishes. While the French had started their attack on Closewitz, the members of the headquarters were still in the bedrooms of Kapellendorf Castle . Until shortly before 7 o'clock we had breakfast in peace. The Hohenlohe area could not imagine that Napoleon would take the risk of attacking from Jena, because in the event of a French defeat, the difficult to access terrain and the river would have made it difficult for Napoleon to retreat. So Hohenlohe did not take reports of a French attack seriously at first. At 8 o'clock he obstructed General Grawert's order to dismantle the tents and prepare for battle. It was only at 8:30 a.m. that Hohenlohe gave the order to react to the French offensive.

As on the previous days, fog prevailed until around nine o'clock. The Prussian camp had been marked out by Massenbach in anticipation of the French along the road from Jena to Weimar in the south-west; in fact, however, the attack came from the southeast over the steep slope of the Saale valley. The troops of the Prussian-Saxon bulk therefore rallied late and hesitantly, when their vanguard under Tauentzien had long since been massively pushed back.

The French attack took place around 6 a.m. from Landgrafenberg and the Windknollen near Jena out of the fog with surprisingly strong artillery support. He met the Prussian vanguard under Tauentzien. This command of his own avant-garde - detachment , which had withdrawn in the previous days fighting with small losses from farm ago. In addition, the command of the remnants of the vanguard defeated in the battle near Saalfeld of the fallen Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia had been entrusted to him. The Saxon commander Lieutenant General Zezschwitz had his division under General Niesemeuschel take up defensive positions on the so-called "snail" ridge southwest of Lützeroda.

Napoleon ordered the V Corps under Lannes to attack the advanced Prussian-Saxon positions first at the villages of Cospeda , Lützeroda and Closewitz and then at Rödigen and Lehesten . To this end, the Gazan Division was assigned to the left and the Suchet Division to the right . Compared to the Saxons, the French VII. Corps under Augereau formed the left wing, while the Desjardin division was able to penetrate Isserstedt with the advance guard, while the Heudelet division advanced from the Mühltal behind . On the Landgrafenberg, under Marshal Lefebvre, the imperial guard, formed in five meetings at Karees, remained and later followed behind Lannes to the Dornberg. General Tauentzien commanded battered, insufficiently prepared troops. The Zweiffel regiment under Colonel Brandenstein was attacked by Vierzehnheiligen at the height between Krippendorf and the windmill. The French troops succeeded in pushing these units off the Dornberg through the foggy battlefield. The IV Corps under Marshal Soult , which formed the right wing of the French, had reached the plateau going through the Rautal . The Saint Hilaire division and the Margaron cavalry brigade pushed the left wing from Tauentzien to Kloswitz and then fell on the intact lines of the Prussian left wing under General Holtzendorff at Rödigen . Meanwhile, Tauentzien's defeated vanguard had gone past Krippendorf to Klein-Romstedt .

The main Prussian power under Hohenlohe formed with a front in the direction of the villages of Isserstedt and Vierzehnheiligen and attacked around 9:30 a.m. Isserstedt was initially recaptured. The infantry of the Prussian Grawert division attacked the village of Vierzehnheiligen and temporarily halted the battle there. On Hohenlohe's orders, the Prussian-Saxon troops moved close to Vierzehnheiligen and shot at it, standing in line and without cover. This defenseless position was maintained for one and a half hours, during which the French infantry and artillery fired on Hohenlohe's troops, because Hohenlohe believed that he could not attack without the support of Rüchel, who was marching from Weimar. The Prussian left wing under Holtzendorff was also thrown back behind Altengönna by the Soult corps and had to retreat to Hermstedt and Apolda . General Sanitz was wounded and fell into French captivity near Heiligenholz. The Prussian front remained too wide, and the French, who received constant reinforcements from Corps Ney , threatened to outflank and encircle the village at Vierzehnheiligen. The Prussian front line broke apart as a result of continuous enemy fire without cover during the attack of the increasingly stronger French infantry, whereupon Hohenlohe had to order the retreat, which, however, led to a panic escape when the cavalry under Murat attacked.

At around 1 p.m. Rüchel's corps reached Kapellendorf , where the Hohenlohe corps , which had already broken up, came towards him. Rüchels Korps undertook an unsuccessful counterattack in which it suffered heavy losses and Rüchel was also badly wounded. Then it went down in the crowd of those fleeing towards Weimar and on to Erfurt Fortress . A total of around 10,000 Prussian and Saxon soldiers were killed or wounded and another 10,000 were captured. The French, on the other hand, had only about 7,500 dead or wounded.

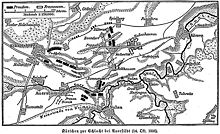

The battle of Auerstedt

15 kilometers further north, 27,300 French under Marshal Davout fought against around 49,800 Prussians under the Duke of Braunschweig . The Prussian cavalry had 8,800 horsemen in the battle of Auerstedt, while the French only had 1,300. In addition, the Prussians had 230, while the French had only 44 cannons . However, the commanders on both sides were unclear about the strength of the enemy. The battlefield was shrouded in unexpectedly thick fog. The Prussian army had been pulled apart in long rows by crossing the Ilm over the only bridge. The French avant-garde met the Prussian vanguard at Hassenhausen and was then attacked by the Prussian cavalry under General Blücher , but was able to repel them with heavy losses.

The French division Gudin could enter the village Hassenhausen while the Division Friant around 9 am north of the road after the attack from reaching Prussian troops Kosen held. Davout ordered his 21st Infantry Regiment to reinforce the positions in Hassenhausen and the 12th Regiment to reinforce his left wing after his right wing was secured by the arrival of Morand's division . Shortly after the attack by the Prussian division Schmettau , the Duke of Braunschweig was hit in the head by a bullet, whereupon he lost his sight. The Prussian division of General Wartensleben , which was on the attack, was thrown back by Morand's troops, Wartensleben was injured and his horse was shot under him. Since General Schmettau was also seriously injured and no new commander- in -chief was appointed to replace the duke, there was no longer any uniform warfare on the Prussian side. Each officer was left to his own devices on tactical issues, something that had never been practiced in the Prussian army.

After further fighting, Prussia's King Friedrich Wilhelm III. in the afternoon finally to retreat. At first he had not even tried to allow the impressive reserves under Kalckreuth , including the guard cavalry, to intervene in the fighting. In contrast to Jena, the withdrawal was initially orderly, albeit without a leader. Soon, however, there was utter confusion with the troops fleeing from Jena to Erfurt. 10,000 Prussians were killed or wounded, 3,000 were taken prisoner. The French had lost 7,420 soldiers. Marshal Davout, who had beaten a double superiority, was honored by Napoleon with the title Duke of Auerstedt .

Causes of defeat

The main cause is in the indecision of Friedrich Wilhelm III. and the Duke of Braunschweig, who overly cautiously and hesitantly shifted responsibility to each other and trusted in the actions of the other (from their own point of view more competent). In contrast, the rivalries and airs of the leading generals Hohenlohe, Rüchel and Kalckreuth are of secondary importance.

The battle did not necessarily have to be lost, as Clausewitz analyzed: Napoleon had taken a high risk when he had his troops occupy a spur around the Landgrafenberg late in the evening. Lannes' corps and the guards crowded into a narrow space in the center (the VI Corps under Ney could only move up in the course of the morning with Marchand's division ). A determined early and massive attack by the Prussian-Saxon troops would have plunged the French, who were clearly inferior at that time, back down the steep slope into the maze of streets of Jena, where there were only inadequate opportunities to retreat over two narrow bridges over the Saale - the catastrophe would probably have been inevitable . Hohenlohe had already prepared this attack, but failed to do so when, at the moment of the attack, Massenbach returned from headquarters with orders to avoid fighting.

Napoleon, however, had correctly assessed Prussian indecision. On the contrary, he always attacked resolutely and energetically and effectively coordinated his army corps, which were under the command of relatively young war-experienced marshals, with independence, responsibility and commitment - the exact opposite of the Prussian generals.

aftermath

The defeats were bitter for the Prussian-Saxon army, but they alone did not lead to a catastrophe. During the retreat attempts had been made to bypass the French troops in the north and to relocate them to Berlin. That failed because the French corps could advance north faster. A large part of the troops deserted . During this retreat the soldiers were ruthlessly pursued and blown up by the French troops. Only a few larger departments managed to withdraw in an orderly manner, in which Blücher and Scharnhorst in particular stood out . But within a few weeks they were forced to surrender west of the Oder near Halle , Prenzlau and Lübeck . King Friedrich Wilhelm III. escaped with his family to East Prussia , and Napoleon entered Berlin on October 27th as a victor.

Likewise, in October and November the great Prussian fortresses of Erfurt , Spandau , Stettin , Küstrin , Magdeburg and Hameln surrendered without a fight. After the king announced in the Ortelsburg audience on December 1st that every commanding officer would be shot if he did not maintain his fortress "with the most strenuous efforts to the utmost", other fortresses resisted to the point of exhaustion: Breslau , Brieg , Glogau , Danzig , Glatz and Neisse . At the time of peace, Kolberg , Glatz , Graudenz , Silberberg , Kosel and Pillau were still in Prussian hands. Military court proceedings were initiated against the commanders of the capitulating fortresses , which resulted in two death sentences . In the Spandau case, the king converted it into fortress arrest on royal mercy , and in the Küstrin case it could not be carried out because of desertion.

With the remnants and reserve troops, Prussia continued the fight east of the Vistula on the side of the Russian army . Rüchel, meanwhile governor of the province of Prussia, helped together with Hardenberg from Königsberg to organize the supplies for the Russian and Prussian armies. The Prussians even achieved local successes under General L'Estocq , e.g. B. in the battle of Heilsberg . The war was finally ended only after further bloody battles: While the Russian army under General Levin August von Bennigsen, in conjunction with the Prussian auxiliary corps under L'Estocq, brought the Grande Armée to the brink of collapse for the first time in the Battle of Prussian Eylau , Bennigsen undermined it Defeat in the Battle of Friedland as well as the subsequent occupation of Königsberg the war will of the Tsar.

When Napoleon concluded an armistice with Russia on June 21, 1807, he had conquered or bound all European states - with the exception of Great Britain, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire - or bound them by treaties. Only a few weeks later, on July 7th, the Treaty of Tilsit between France and Russia stipulated that Prussia had to cede half of its national territory but was retained. Two days later, Prussia was left with no choice, and it also signed a corresponding peace agreement. Napoleon also pushed through the dismissal of Hardenberg and Rüchel. In the Königsberg follow-up agreement of July 12, 1807, France undertook to withdraw its troops from Prussia step by step in accordance with the compensation for the war contribution still to be determined. The amount of the war contribution was not set by Napoleon until September 8, 1808 in the Paris Convention. According to this agreement, French garrisons were to remain in the Prussian fortresses of Stettin , Küstrin and Glogau until 120 million francs were paid , the Prussian army was to be reduced to 42,000 men, and any kind of militia or reserve was forbidden. France undertook to evacuate Prussia with the exception of the fortresses within 40 days.

The catastrophic defeat cleared the way for Prussia for far-reaching reforms in the municipal constitution and trade law (city and trade regulations), agriculture, military and education (peasant exemption, conscription, University of Berlin and trade schools). These contributed to the fact that Prussia was able to fight Napoleon again in 1813. After the Congress of Vienna in 1814, Prussia again became a major power in Europe .

European historiography sets the epochs - the break between “ modern and modern history ” to the year 1789 ( French Revolution ); for Prussia in particular, this epochal break can be seen in the year of the battle of Jena and Auerstedt.

Trivia

On October 11, 1806, three days before the battle, Professor Hegel from Jenens quickly sent the finally finished, extensive manuscript of his first major work “ Phenomenology of the Spirit ” to his publisher. The false report that the French had broken into the city resulted in indescribable chaos in the city and its surroundings for the rest of the day, so that Hegel feared the loss of the manuscript for a long time, but it actually reached his publisher.

On the evening of the battle, Goethe was threatened by plundering French soldiers in his house in Weimar and rescued by the courageous intervention of his long-time partner Christiane Vulpius . He married her five days later on October 19, 1806. Goethe chose the date of the Battle of Jena as the engraving for the rings: October 14, 1806.

Commemoration

For the 180th anniversary in 1986, the Kulturbund of the GDR held a commemorative event for the Prussian defeat at Kapellendorf. The battles were recreated by soldiers in historical uniforms. The mayor of Kapellendorf welcomed the guests of the multi-day event at the memorial on the Sperlingsberg.

On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the double battle, the battle was re-enacted on October 14, 2006 with 1,800 participants on a 600 m by 800 m fenced area near the village of Cospeda. Annually in October, close to the historical date, the association AG “Jena 1806 e. V. “Commemorative events organized. This takes place on a larger scale every five years.

In the vicinity of Jena , several hiking trails are named after Napoleon and some of his marshals . In the villages of Cospeda (here the museum 1806 ), Lützeroda and Vierzehnheiligen near Jena, several memorial plaques, memorial stones and wall paintings commemorate the battle.

In Paris the most are the Eiffel Tower located His bridge Pont d'Iéna (1814) and the Avenue d'Iéna (1858) along with their metro station named (1923) after the battle.

The French Navy commemorated Napoleon's victory with the following ships named "Jena": a corvette (1807-1810), a 110-gun ship of the line (1814-1864) and an ironclad from 1897, which exploded in 1907 in the port of Toulon. After that, no warship received this name.

See also

- List of wars

- List of battles

- List of infantry regiments of the Old Prussian Army

- List of cavalry regiments of the Old Prussian Army

literature

Modern analysis

- Frank Bauer: Jena October 14, 1806. The first part of Prussia's debacle. (Small series History of the Wars of Liberation 1813–1815, no. 33), Potsdam 2011.

- Frank Bauer: Auerstedt October 14, 1806. The finale of Prussia's debacle. (Small series History of the Wars of Liberation 1813–1815, no. 34), Potsdam 2011.

- Holger Nowak, Birgitt Hellmann, Günther Queisser, Gerd Fesser: Lexicon for the battle near Jena and Auerstedt 1806. People, events, terms . Municipal museums Jena, supplemented and corrected rough version 2006.

- Gerd Fesser : 1806 - The double battle at Jena and Auerstedt. Publishing house Dr. Bussert & Stadeler, Jena / Quedlinburg 2006, ISBN 3-932906-70-5 .

- Detlef Wenzlik, Wolfgang Handrick: The battle of Auerstedt - October 14, 1806. VRZ Verlag Zbod, Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-931482-00-6 .

- The battle of Jena and Auerstedt on October 14, 1806. A production by Jena Kultur / Stadtmuseum Jena in cooperation with the Institute for Military History Research Jena 1806 e. V. and G-VIDEO Wuppertal. DVD 47 min. Jena 2006.

- Holger Nowak, Birgitt Hellmann (ed.): The battle near Jena and Auerstedt on October 14, 1806 . Municipal museums, Jena 2005, ISBN 3-930128-17-9 (exhibition catalog).

- Werner Meister: 200 Years of the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt - The Auerstedt events on October 14, 1806. 1st edition. Auerstedt 2005.

- Olaf Jessen: "Prussia's Napoleon"? Ernst von Rüchel. 1754-1823. War in the Age of Reason . Schöningh, Paderborn 2007, ISBN 978-3-506-75699-2 (also: Dissertation, University of Potsdam 2004).

- Arnaud Blin: Iéna. October 1806 . Perrin , Paris 2003, ISBN 2-262-01751-4 .

- Gunther Rothenberg: The Napoleonic Wars. Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, 1999/2000, ISBN 3-89488-134-8 .

- Gerd Fesser: Change in the shadow of Napoleon: the battles of Jena and Auerstedt and their consequences. (Building blocks for Jena city history; 3). Bussert publishing house, Jena 1998, ISBN 3-9804590-9-8 .

- Gerd Fesser: Jena and Auerstedt. The Franco-Prussian War of 1806/07 . Glaux-Verlag , Jena 1996, ISBN 3-931743-07-1 .

- Günter Steiger: The battle near Jena and Auerstedt 1806. Published by the municipal administration of Cospeda in conjunction with Marga Steiger (Jena); edited by Joachim Bauer (Cospeda) and Klaus-Peter Lange (Lützeroda) [based on the older version from 1981, GDR]; 2. edit and exp. Edition. Verlag Gerhard Seichter, Rudolstadt 1994, ISBN 3-930702-00-2 .

- Karl-Volker Neugebauer (Ed .; on behalf of the Military History Research Office , Breisgau): Basic features of German military history. Volume 1, Rombach Verlag , Freiburg 1993, ISBN 3-7930-0662-6 .

- Ruth-Barbara Schlenker: "Ponapart, a right iron eater and our enemy too" - The battle of Auerstedt and other catastrophes (= PS08 ).

Meetings

- Mathias Tullner , Sascha Möbius (Ed.): 1806. Jena, Auerstedt and the surrender of Magdeburg. Shame or chance ?. Protocol of the scientific conference from October 13th to 15th, 2006 in Magdeburg (= contributions to regional and state culture of Saxony-Anhalt . H. 46). Landesheimatbund Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle 2007, ISBN 978-3-928466-99-8 .

Older representations

- Carl von Clausewitz : News about Prussia in its greatest catastrophe (1823/24). reprinted in excerpts in: Gerhard Förster (Ed.): Carl von Clausewitz - Selected military writings. Berlin 1981, pp. 76-124.

- Frederic N. Maude: The Jena campaign, 1806. (Napoleonic library; 33). Greenhill Books, London 1998, ISBN 1-85367-310-2 . (Reprint of the London 1909 edition)

- Francis L. Petre: Napoleon's conquest of Prussia 1806. (Napoleonic library; 23). Greenhill Books, London 1993, ISBN 1-85367-145-2 . (Reprint of the London 1907 edition)

- Joh. Gust. Droysen : The life of Field Marshal Count Yorck von Wartenburg 7th edition. 2 volumes, Insel Verlag , Leipzig 1913.

- Ms. Rud. von Rothenburg: The battles of the Prussians and their allies from 1741 to 1815. Melchior Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-939791-12-1 . (Reprint of the 2nd improved edition from 1847)

- Leipzig Teachers' Association (ed.): In the struggle for freedom and fatherland 1806–1815. 9th edition. Alfred Hans Verlag, Leipzig 1918.

- Hermann Müller-Bohn: The German Wars of Liberation. First volume, published by Paul Kittel / Historischer Verlag in Berlin, 1901.

- Paul Schreckenbach : The collapse of Prussia in 1806. A souvenir for the German people. With 100 illustrations and supplements based on contemporary representations . Diederichs , Jena 1906

Eyewitness and military reports

- 1806. The Prussian officer corps and the investigation of the war events. ed. v. Great General Staff, Berlin 1906 (the statements of the most important participants for the investigative commission in 1807 and 1808). Digitized

- P. Foucart (ed.): Campagne de Prusse - (1806) d'apres les archives de la guerre - IENA (Compiled orders, correspondence and bulletins of the French war archives with comments); Librairie Militaire Berger-Levrault et Cie, Paris, 1887

- Ruthard von Frankenberg: In the Black Corps to Waterloo. Memoirs of Major Erdmann von Frankenberg . edition by frankenberg, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-00-048000-3 .

- Birgitt Hellmann (ed.): Citizens, farmers and soldiers. Napoleon's war in Thuringia 1806 in self-reports. (Building blocks for Jena city history; 9). Hain-Verlag, Weimar 2005, ISBN 3-89807-082-4 .

- Christina Junghanß (Ed.): My Hegira. Diary entries from 1806 . Stadtmuseum, Weimar 1997, ISBN 3-910053-30-0 . (Experience report by Friedrich Justin Bertuch (1747–1822))

- Klaus-Peter Lange (Ed.): Descriptions of the strangest war events at Auerstädt . New edition. Wartburg-Verlag , Jena 1992, ISBN 3-86160-066-8 (experience report from master butcher Johann Adam Krippendorf )

- Journal historique of the 3rd Davout Corps, 1809

Anecdotes

- Heinrich von Kleist : Anecdote from the last Prussian war . In: Ders .: All the stories and anecdotes . Dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-02033-4 (1810-1811 first published in the Berliner Abendblatt ).

Poems

The battle stimulated numerous contemporary authors to publish poems, including Moritz Ferdinand Gustav von Rockhausen . A selection, including other journalistic echoes, was offered by Paul Schreckenbach in 1906.

Web links

- Jena 1806

- Auerstedt 1806

- Detailed description of the battle

- Experimental documentation of the battle, created in 2006/07 at the Faculty of Media, Bauhaus University Weimar . Also teaches the basics of linear and Column tactics, but without being able to realistically visualize contemporary experiences of battle and violence.

- Extensive information on the first day of the war . As well as the events in Saalburg on October 8, 1806, when the first shots were fired.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Main sources for this chapter unless otherwise indicated: Veit Valentin: Illustrierte Weltgeschichte ; Volume 3; Special edition for Lingen Verlag Cologne, 1976 | World history in pictures - Volume 18 - Napoleon and his conquests / The collapse of the empire ; Editions Rencontre Lausanne, 1970 | Günter Steiger: The battle near Jena and Auerstedt 1806 ; Verlag Gerhard Seichter, 2nd edit. and exp. 1994 edition | Gerd Fesser: 1806 - The double battle near Jena and Auerstedt ; Publishing house Dr. Bussert & Stadeler, 2006 | Detlef Wenzlik / Dr. Wolfgang Handrick: The battle of Auerstedt October 14, 1806 ; VRZ Verlag, Oct. 2006 | various Wikipedia articles on the topic, especially those of the cross-references

- ↑ Müller-Bohn: The German Wars of Liberation 1806–1805 (see bibliography) p. 15

- ↑ Müller-Bohn (see Lit.-Verz.) P. 17; even Hardenberg learned nothing of this instruction

- ↑ Müller-Bohn (see Lit.-Verz.) P. 19

- ↑ Müller-Bohn (see Lit.-Verz.) P. 22

- ↑ Müller-Bohn (see Lit.-Verz.) P. 26; according to Fesser 1806 - The double battle near Jena and Auerstedt p. 34 also called the "Paris treatise"

- ↑ Wenzlik / Handrick The battle of Auerstedt (see lit.-catalog) p. 9

- ↑ Müller-Bohn (see Lit.-Verz.) P. 32 ff. (As its source is named here: Baillen, Paul, Diplom. Korrespondenzen. Publications from the royal Prussian state archives), the seriousness of the offer is, however questioned; Valentin, Veit: Illustrierte Weltgeschichte (see Lit.-Verz.) Volume 3, p. 925, whereby he notes here: “It is very possible that Napoleon would have tolerated such a foundation if Prussia got involved in a vassal relationship would have."

- ↑ Source: u. a. Marshal Bernadotte, Crown Prince of Sweden by Hans Klaeber, Gotha 1910; P. 174 ff. (Shown as a facsimile; original in the Swedish war archive); Jean Baptiste Bernadotte , by Gabriel Girod de L'Ain p 167; also with DP Barton Bernadotte 1936 and other Bernadotte biographers; Missing in the French war archive ( Campagne de Prusse - (1806) d'apres les archives de la guerre) by P. Foucart), but analogous confirmation by the Journal historique of the 3rd Corps of Davout 1809

- ↑ A few hours earlier, Napoleon had overcome the same height difference on Landgrafenberg, even with artillery . This surprise coup laid the foundation for victory. After crossing the Saale, Bernadotte marches on Apolda, although he heard the thunder of cannons from both Jena and Auerstedt and yet did not intervene in the fighting either here or there.

- ↑ Owen Connelly: Blundering to Glory: Napoleon's Military Campaigns , Rowman, Lanham 2006, third edition, p 97th

- ↑ Volkmar Regling: Basics of land warfare at the time of absolutism and in the 19th century , in: Handbuch zur deutschen Militärgeschichte 1648-1939 , ed. v. Military history research office by Friedrich Forstmeier u. a., Hamburg 1979, p. 267

- ↑ Gerd Fesser: 1806, The double battle near Jena and Auerstedt, Bussert, Jena 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Owen Connelly: Blundering to Glory: Napoleon's Military Campaigns , Rowman, Lanham 2006, third edition, p 97th

- ↑ Gerd Fesser: 1806, The double battle near Jena and Auerstedt, Bussert, Jena 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Holger Nowak u. Brigitt Hellmann: Report of General Savary on the Battle of Jena In The Battle of Jena and Auerstedt on October 14, 1806 , 2nd verb. Jena 2005, p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Wolf Jörg Schuster: We are invited to a rendezvous - Napoleon in Thuringia 1806, Köhler, Jena 1992, pp. 174–175 and Gerd Fesser: 1806, Die Doppelschlacht bei Jena and Auerstedt, Bussert, Jena 2006, pp. 44–45 .

- ↑ Wolf Jörg Schuster: We are invited to a rendezvous - Napoleon in Thuringia 1806, Köhler, Jena 1992, p. 178 and Wilhelm Bringmann: Prussia in 1806 , ibidem, Stuttgart 2019, p. 349–359.

- ↑ Since the Seven Years' War of Frederick the Great, the cuirassier regiment Garde u Corps has boasted: "No battle is lost until the regiment Garde du Corps has attacked."

- ↑ Hohenlohe and Massenbach opposed the headquarters during the entire campaign and sometimes even acted contrary to orders. It is not known why they obeyed at this very promising moment.

- ^ Philippe Caresse: The Iéna Disaster , 1907. In: John Jordan, Stephen Dent: Warship 2007. Conway Maritime, London 2007, ISBN 1-84486-041-8 , pp. 121-138.

- ↑ Vom schmauchender Fähndrich (Dedicated to the battle of Jena-Auerstedt in 1806). In: Soldiers World, by Richard von Meerheim, Verlag CC Meinhold and Sons, Dresden 1857, pp. 113–115

- ↑ Lit., pp. 199–208, with facsimiles from pp. 192, 204, 206