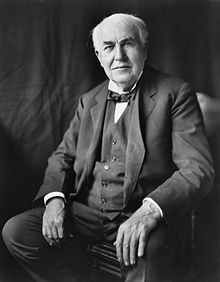

Thomas Alva Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (born February 11, 1847 in Milan , Ohio , † October 18, 1931 in West Orange , New Jersey ) was an American inventor and entrepreneur with a focus on the field of electricity and electrical engineering . His merits are based primarily on the marketability of his inventions, which he was able to combine with skill into a whole system of electricity generation , electricity distribution and innovative electrical consumer products. Edison's fundamental inventions and developments in the fields of electric light, telecommunications and media for sound and images had a great influence on general technical and cultural development. In later years he made important developments in process engineering for the chemical and cement sectors. His organization of industrial research shaped the development work of later companies.

Edison's accomplishments in electrifying New York and introducing electric light marked the beginning of the extensive electrification of the industrialized world. This epochal change is particularly associated with his name.

Life

Youth and beginning of his career as a telegraph operator (1847 to 1868)

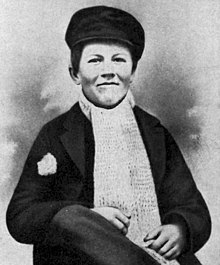

Thomas Alva Edison was born on February 11, 1847 in Milan, a village in northern Ohio, the seventh child of Samuel Ogden Edison (1804-1896) and Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810-1871). His mother worked for a while as a teacher, his father frequently held changing freelance activities, including gravel mining, agriculture and property speculation. He was a free thinker and political activist who had to emigrate from Canada to the USA. The parental home is considered to be intellectually stimulating.

Thomas Edison only received regular schooling for a few months. After that, his mother continued to teach him. When he was seven, the family moved to Port Huron , Michigan . Four years later, in 1859, he got his first job selling candy and newspapers on the Grand Trunk Railroad between Port Huron and Detroit . He used the long stopping times of the train in Detroit until the return journey to read books in the local library.

Edison had hearing problems as a child and was hard of hearing all his life.

In 1862 he received instruction in telegraph technology from a telegraph operator, whose son he had saved from an accident . He then worked as a telegraph operator for James U. MacKenzie in Mount Clemens . For five years, from 1863 to 1868, he held frequently rotating positions as a telegraph operator in Stratford , Indianapolis , Cincinnati , Memphis , Louisville and Boston . During this time he gained a profound understanding of telegraph technology in addition to operation, as the telegraph operators often also had to maintain the equipment and batteries. By working with telegraph operators from companies and newspapers, he recognized the importance of this technology for many business areas. At that time, he is said to have trained himself further with electrical engineering books and specialist magazines and started experimenting. In 1868 in Boston he came into contact with the world of telegraph manufacturers, telegraph constructors and the financiers of this technology, and began developing telegraph technology himself.

Rise as an inventor in the telegraph industry (1868 to 1876)

On April 11, 1868, the journal The Telegrapher published a report written by Edison himself. The topic was a variant of the duplex technology developed by him for the simultaneous transmission of two messages over one line. This first publication by Edison also caused his perception in the professional world outside of his personal circle. In 1868 he applied for his first patent for an electric meeting voting counter. However, this was not used in Congress . MEPs preferred the traditional slow process, as it left more opportunities to delay unpopular motions and change MEPs' minds.

In 1869 Edison went to New York. There he met Franklin Leonard Pope , through whom he came into contact with the Gold & Stock Telegraph Company and was responsible for all of the company's telegraph technology. He later became a partner in the company Pope, Edison & Co. founded by Pope. Both of them jointly acquired patents for telegraphs with printing devices. These were needed , among other things, to transmit gold prices from the stock exchange to traders. Another printing telegraph developed by Edison and Pope should be especially suitable for use by private individuals or small companies without specialist staff. The American Printing Telegraph Co. was founded together with other partners for this market segment . The joint enterprise Pope, Edison & Co. was dissolved again at the end of 1870. The joint patents and also the successful business of the American Printing Telegraph Co. bought the Gold & Stock Telegraph Co. Among other things, through the cooperation with Pope, who was in contact with many specialist newspapers and electrical companies, the telegraph industry became increasingly aware of Edison's talent . The developments of Pope and Edison were also relevant in the struggle of the telegraph companies for the lucrative market of financial information services.

From the end of their collaboration until his death in 1895, Franklin Pope had a significantly different opinion of Thomas Edison from the public perception. In specialist books and articles for specialist journals, he qualified the inventions attributed to Edison. As a patent attorney or expert witness, he often represented plaintiffs against Edison companies.

In 1870, Edison's first design and manufacturing workshop was opened in Newark , New Jersey. His partner in the production of course telegraphs was the mechanic William Unger . For the expanding business, Edison founded a new workshop in 1872 with the mechanic Joseph Thomas Murray and paid Unger out. These workshops for the production of telegraphs and telegraphs for private lines had around 50 employees and had a production of around 600 devices per year. They marked the beginning of Edison's activity as an inventor-entrepreneur.

Edison's financial situation improved in these years through numerous collaborations and the exploitation of inventions in telegraph technology. While he was still living with the family of his then friend Pope in 1869, he was able to buy his first house and start his own family in 1871. He married Mary Stilwell. In 1873 his first child Marion was born. Edison's financial situation remained unstable, however, because the high costs for his development work and his own production workshops were offset by only irregular income. He had to give up his house again in 1874 and temporarily move into an apartment.

The central problem of the telegraph companies at that time was the efficient use of expensive telegraph lines. Automatic telegraphs, which send pre-prepared messages quickly on paper tape, were designed by Julius Wilhelm Gintl and developed by Joseph Barker Stearns (1831–1895) to be ready for use in England. However, they did not work on the long distances of the telegraph lines in America. Edison was able to solve the problem of signal quality and further accelerate the telegraph, whereby in particular the recording of messages at the receiver had to be further developed for the speed requirements. From 25 to 40 words per minute for the manual telegraph and 60 to 120 words for the original invention of the automatic telegraph, Edison improved the transmission speed to 500 to 1000 words per minute.

An attempt to sell the technology to the British Post Office Telegraph Department failed. During a trip to London in 1873, Edison found problems in solving it with underground telegraph lines. The realization that he knew less than he believed, as well as the contact with the more advanced electrical engineering in England, were probably the reason for expanding his development activities to include experimental research and a more intensive study of specialist literature.

With the quadruplex telegraph, Edison developed a technology for the simultaneous transmission of four messages and thus further increased the use of telegraph lines. His solution was to use the voltage amplitude for signal transmission of one message (amplitude modulation) and the polarity for the second message (phase modulation). He combined this technology with the well-known duplex technology, which enabled the simultaneous transmission of messages in both directions. Telegraph companies that had rights to this technology saved large amounts of money for the otherwise necessary expansion of their transmission capacities through additional lines.

The sale of rights to quadruplex technology and other inventions in early 1875 opened up new opportunities for Edison. He benefited from the intention of the railroad industrialist Jay Gould to build a network with the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Co. that would compete with the market leader Western Union . Western Union's approach to building telegraph lines along railway lines could easily be copied by Gould, and the rights to high-performance technology he bought from Edison. With the proceeds, he was able to adjust his precarious financial situation and set up his first inventor laboratory in Newark, which he expanded a short time later and relocated to Menlo Park . With Charles Batchelor , Charles Wurth and John Kruesi , employees from his telegraph manufacturing workshops, and the newly hired James Adams, Edison made research, invention and development his core activity.

The development of the electric pen, begun in 1875, and a copying and printing technique based on it, which was later developed into mimeography , was inspired by work on telegraph technology. The invention was patented by US Patent 180,867 from August 8, 1876 as Autographic Printing . It was Edison's first attempt to generate regular income from inventions and their commercialization. The inventor and entrepreneur Albert Blake Dick developed a variant without electrics using an Edison patent, sold the product as the Edison Mimeograph and achieved high sales figures for decades. By 1889 he had sold around 20,000 devices in the USA and established copier technology in companies and authorities. The devices produced by Edison itself were considered "too technical" and were far less successful. While the telegraphy inventions were about infrastructure for a few interested parties, the electric pen was Thomas Edison's first product for the mass market with the special importance of advertising, sales and customer reactions. His employees, Adams and Batchelor, participated in the proceeds.

For a short time Edison was involved in a scientific dispute about an effect he had discovered called Etheric Force , which later turned out to be the discovery of high-frequency electromagnetic waves. However, he failed to develop his advanced experiments in wireless telegraphy.

Thomas Edison had a contractual relationship with the important Western Union Telegraph Co. The company paid him to develop acoustic telegraphy . In telegraph technology, he established his reputation as an inventor from 1869 to 1875 and worked out the financial prerequisites for his further achievements. Edison was a well-known man in the industry in 1875 and featured in professional journals. However, he only became known to the general public in the following years. Telegraph technology was no longer the focus of his work.

Franklin Pope, Marshall Lefferts , President of the Gold and Stock Telegraph Co. , and William Orton , President of the Western Union Telegraph Co., are considered essential pioneers in Thomas Edison's further rise. He owes a network of relationships with newspapers, technology companies and patent attorneys in particular to Pope. He owes contact with investors and knowledge of financing and the need for a business plan to Lefferts and Orton, who also promoted Edison's reputation with other business people. From them he learned in particular that you need a complete set of all the necessary patents to control a technological project.

The Edison Laboratory in Menlo Park, founding years (1876 to 1880)

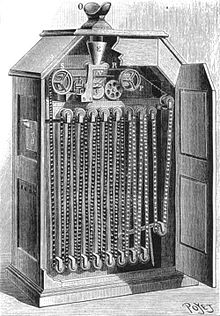

On July 18, 1877, Edison invented the phonograph , which was developed in the following months. In contrast to many of his other inventions, this was something fundamentally new and not a further development of known technology. Edison's work on automatic telegraphs that sent texts stored on embossed paper strips led to the discovery that the embossed paper strips, when executed at high speed, generated vibrations and sounds in the mechanics of the telegraph. This observation was further developed by Edison into the phonograph. According to Thomas Edison's recollections, the first recording with a working phonograph was a verse Mary had a little lamb . He wrote that he was "moved" when hearing his own voice. The phonograph was presented to the public in November 1877 and received the patent on February 19, 1878.

Also in 1877, Thomas Edison achieved a decisive improvement in telephone technology with the development of his charcoal microphone . The patent for it was only awarded to him after a long dispute with Bell Labs , which had acquired a patent from Emil Berliner that was later declared invalid . In the telephones already offered by the Bell Telephone Company at that time, the energy for generating an electrical signal in the microphone itself was obtained from the sound that was picked up. However, without the electronic amplification that was only available in the 20th century, signals generated in this way were too weak for transmission over longer distances. Bell's telephones could therefore only be used in local areas. Telegraph companies competing with Bell, which themselves wanted to implement new business models based on the telephone invention, commissioned Edison to develop a solution to this problem. Edison's carbon fiber microphone no longer extracts the energy required for the electrical signal from sound, but takes it from an external energy source. A suitably strong, externally fed current is conducted through the microphone. The sound waves influence the electrical resistance of the charcoal filling contained in the microphone. In this way, a strong signal current is modulated by a weak sound pressure . Understandable voice transmission by telephone was thus possible over significantly longer distances. The economic value to the emerging telephone companies was substantial.

Thomas Edison used the call hello on the phone, while Alexander Graham Bell preferred ahoy .

Edison realized that the proliferation of consumer electrical products required electrical power grids. Electric light was seen as a key product in financing them and in building homeowners' willingness to lay cables. The model was the business model of the gas industry with central supply, gas meters and the one-time sale of lamps on the one hand, but sustainable income from regular energy supplies on the other. In order to implement his vision of the electrification of cities, Edison and his employees worked intensively on all the necessary components, in particular on the light bulb, the switches and the electricity meter . The construction of suitable generators was a particular challenge. The dynamos , which Edison initially only built for its own use, could only provide electricity for 60 light bulbs. All components of the power supply infrastructure therefore had to be redesigned and then manufactured by the company or by partner companies. A group of investors around JP Morgan made $ 130,000 available for development work on the electrical inventions through a stake in Edison Electric Light Co., founded in 1878 .

Previous inventors had also dealt with the electric light bulb. But none of them had succeeded in making them permanently functional and their energy consumption competitive with that of the gas lamps . The advantages such as freedom from flickering and odor, lower heat emission and easier switching on and off could not be implemented in practical products. Another unsolved problem was the division of light. Only a few lamps could be operated from a power source with the solutions known at the time. Some physicists considered the problem to be unsolvable and that electric light was in principle not suitable for replacing gas light.

Edison's attempts to improve the well-known incandescent lamps with platinum filament also initially failed. In 1879, however, he had his first successes with incandescent lamps with a high-resistance carbon filament and perfect vacuum sealing, with which he supposedly reached around 40 hours of lighting time. The breakthrough is usually associated with a test and demonstration on October 21, 1879; this date is therefore the date of the invention of the practical incandescent lamp. The more recent research on sources cannot confirm this widespread account; the laboratory books record the beginning of tests with carbon threads made of cotton on October 21, 1879 and about 14.5 hours burning time of a lamp with high-resistance carbon thread on October 23, 1879. The improvement to up to 1000 hours of lighting duration took another three years of development. Presentation events in Menlo Park, especially on December 31, 1879, already impressed the newspapers and the public. This created a public awareness of the beginning electric age. Edison was able to gain support and tackle his project to electrify New York. The basic patent for lamp development by Thomas Edison, No. 223,898 "Electric Lamp", was applied for on November 4, 1879 and granted on January 27, 1880.

The consumption meter, which is important for the business model of electricity networks, was based on an electrolytic measuring principle that was only suitable for direct current; various other developments were discarded. The construction was strongly influenced by Michael Faraday's experimental investigations of the electrochemical processes of electrolysis and his construction of the voltameter . The Edison consumption meter is a further development of the copper voltimeter, later zinc was used. The core problem of the measuring range was solved by a parallel connection that only leads a proportionally small proportion of the current through the measuring device ; the patent was applied for on March 20, 1880. Edison compensated for the influence of temperature on the resistance behavior of the electrolyte with a negative temperature coefficient by using a coil resistance with a positive temperature coefficient. An incandescent lamp in the meter housing switched on as a heat source via a bimetal switch when the temperature dropped too much . Edison referred to further developments as Webermeter , in honor of the German physicist Wilhelm Eduard Weber . The level of development of the model exhibited at the electricity exhibition in Paris in 1881 was part of the development of the electricity industry as an Edison meter in the 1880s. Although the meter had a high level of accuracy, was less prone to failure due to the saving of mechanical parts and had only very little internal consumption, consumers were often skeptical because the consumption could not be read. To determine consumption, employees of the electricity industry had to remove the electrodes and weigh them on a precision scale; one gram weight difference corresponded to 1000 hours of lamp burning. To be on the safe side, each meter had a second electrolytic measuring device designed to reduce the weight of the anode by one gram for every 3000 hours of lamp burning. One hour of burning of the lamp corresponds to 800 mAh , or 88 Wh at 110 V of the Edison network .

After public demonstrations of the phonograph to the President of the United States and elsewhere in April 1878, the local and European press celebrated Thomas Edison for the first time as a great inventor. He also impressed the public in December 1879 with previously unknown light displays with a large number of light bulbs instantly turning on and off, and in 1880 by installing his lighting system on the newly built steamship SS Columbia . From the late 1870s, not only trade magazines but also daily newspapers reported on Edison, who thereby became a world-famous personality. Some newspapers called him the "Wizard of Menlo Park". This designation, coined by William Augustus Croffut , became an established term in American culture.

The electrification of New York and the establishment of an electrical company (1881 to 1886)

In the years that followed, the focus of Edison's personal work shifted away from the development and towards the marketing and implementation of electrification projects. At times he moved his residence and parts of his development team from Menlo Park to New York. While up to then production sites mostly had the character of workshops, the manufacture of light bulbs and components for the mass business with light and electricity required the construction of factories and the development of efficient manufacturing processes. Edison's first lamp factory, Edison Lamp Co. , was located first in Menlo Park and then in Harrison , New Jersey. From its foundation to April 1882, 132,000 light bulbs were produced there.

The Edison Electric Light Co. was founded on 15 November 1878th It had the right to exploit the patents developed in Menlo Park and in return financed the work of the development laboratory. The company founded subsidiaries and cooperation companies in the USA and abroad and provided them and other partners with the necessary patent rights. This company can therefore be seen as the core of the electrical company that will emerge from it. The Edison Electric Light Company of Europe was established in December 1880. In 1883, the German Edison Society for Applied Electricity , later AEG , was established through a cooperation with Emil Rathenau . At the end of 1886, the companies founded by Edison with around 3,000 employees and around ten million dollars in capital were among the large corporations of their time. The individual Edison companies in the USA, however, had different ownership structures and interests. Edison's focus on overseas license income rather than building a global company was not particularly a sustainable strategy.

Raising capital for the expansion of manufacturing capacities and for the large investments required in power plants and in urban cabling was the main problem until the mid-1880s. The lack of specialists for cabling and the operation of power plants also prevented electrification projects from being implemented quickly and safely. Edison himself was no longer available to some important employees in the USA because they had to take care of electrification projects and the establishment of companies in Europe.

For these reasons, electrification was initially supported by lighting systems with their own steam engine dynamo. Edison developed solutions for different quantities of lamps to be operated. Factories for which gas lamps represented a fire hazard, theaters, train stations and wealthy private individuals were the customers. A theater in Boston was wired within a few days and over 600 light bulbs and a dynamo were installed. The Mahen Theater in Brno was the first building in Europe to have an Edison lighting system installed in 1882. In Germany, in 1884, the Café Bauer in Berlin was the first building to be illuminated with incandescent lamps; the lamps were manufactured by Emil Rathenau according to Edison patents.

Underground cables were laid in New York by 1881. Edison also invented electrical fuses, gauges, and improved steam engine dynamos . On September 4, 1882, the first central power station in the USA was opened with the Pearl Street Station in New York's Pearl Street; it was designed for direct current technology. In the office of the banker J. P. Morgan, who had invested in the Edison Electric Light Co. , the network was switched on by switching on lamps. The six steam engine dynamos constructed weighed 27 tons each and delivered 100 kW of power each, sufficient for around 1100 lamps. As early as October 1, 1882, 59 customers were supplied, a year later there were 513 customers. The Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York ( New York Edison Company from 1901 ), founded for the project in 1880, was the prototype for other local electrification companies. In 1911, the company operated 33 power plants that supplied 4.6 million lamps for 108,500 customers. This growth took place analogously in other cities of the world and had to be managed technically and administratively. The first commercial Edison electricity network in Europe went into operation in Milan in 1883.

The costs of power plants and networks had to be reduced in order to spread this concept. The first electrification projects in smaller towns in the USA with alternative constructions such as above-ground cabling were operational in 1883. The search for suitable locations with a sufficient number of customers in the area of a power plant that had to be cabled economically and the financing of these projects initially remained problematic. In order to utilize the planned power plants to full capacity throughout the day and operate them economically, Edison dealt with the development of engines and the electrification of rail vehicles. The process up to the acceptance of power plants and networks by investors and finally up to a self-supporting wave of electrification took place slowly. After successful projects, however, more and more cities without an electricity network feared location disadvantages and invested in power plants and networks; Edison could limit himself to the role of a technology supplier.

The three-wire system for the electrical power supply developed by Edison allows smaller cross-sections of the cables and thus saves considerable amounts of copper. Edison thought in terms of systems and always kept an eye on economic factors such as the price of copper, since the success of his project depended on the fact that gas lighting was kept below the cost. In addition to the three-wire system, the invention of a special cabling technology was of great importance. It enabled a constant voltage in the entire supply network ( Electric Distribution System , patent 264642). Without this solution, the luminosity of the incandescent lamps would have decreased with the distance from the power station.

The key product incandescent lamp has been continuously developed. In 1882 alone, 32 patents were registered in connection with light bulbs, their production and the manufacture of filaments. As early as February 13, 1880, while investigating the reason for the consumption of filaments, Edison had first observed the glowing electrical effect, which was later called the Edison effect and, according to the mathematical description by Owen Willans Richardson, is now mostly called the Edison-Richardson effect . On November 15, 1883, Edison applied for patent 307,031 for an application of this effect. He used the effect to display voltage changes in a circuit and to regulate the voltage.

The years from 1880 to 1886 with activities in the USA and Europe and numerous company reasons on the one hand, but also technical problems and the need for an immediate reaction to them as well as frequent lack of capital on the other hand, were very intense in Thomas Edison's life. For lack of time, he had to leave far-reaching decisions to employees, and he often only had time to talk to his private secretary well after midnight. During this phase, his wife Mary died in August 1884 at the age of 29. His second marriage in 1886 and the permanent departure of his home and laboratory in Menlo Park mark the beginning of a new phase of life.

After the death of his wife, Edison first worked on improving some of his earlier inventions. Among other things, he improved his telephone for Bell Telephone Co. by using granulate made of anthracite carbon for the microphone. This construction remained in use until the 1970s. He also found a solution to operate several telephones on one line. Edison worked on this with his friend Ezra Gilliland . Both acquired in 1885 in Fort Myers ( Florida adjacent) land and built the same building. Thomas Edison regularly spent winter holidays there with his second wife; later the house became a second residence.

The Edison Laboratory in West Orange and the founding of General Electric (1887-1900)

In 1887, Edison moved development work to a new laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, about ten times the size of his previous laboratory and the most modern of its time.

As a reaction to the further development of his phonograph to the Graphophone , which worked for the first time with a phonograph cylinder made of wax and had a considerable improvement in sound, by Alexander Graham Bell , his first cousin Chichester Alexander Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter , the three members of the Volta Laboratory Association , active in the Volta Laboratory of the same name , Edison further developed the phonograph after he had rejected an offer from the developers of the Graphophone to jointly promote the commercialization of their “new” speaking machines. By 1890 he improved the phonograph (Improved Phonograph) and developed it into a dictation machine ( Edison Business Phonograph , later sold as Ediphone ) and phonograph cylinders made of wax, the recordings of which could be erased by scraping off the top layer of wax and the grooves engraved in it and then reused . Lack of time and money due to his intensive involvement in the electrical industry led him to sell the marketing rights to the entrepreneur Jesse H. Lippincott , who then founded the North American Phonograph Company . An application of the phonograph in talking toy dolls failed, however.

In the competition for market share in electrification, there was the so-called power war between Thomas Edison and his competitors George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla in the late 1880s . Edison preferred the direct current system , Westinghouse and Tesla preferred alternating current electrification . Animal experiments with alternating voltage were carried out by Edison's company in order to demonstrate the dangers of direct current. These later aroused outrage among animal rights activists ; at that time, however, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals encouraged the development of electrocution as a painless alternative to the then frequent drowning of stray animals. Harold P. Brown also carried out animal experiments for the development of the electric chair , a work commissioned by the American government to Edison . Ultimately, because of its technical advantages, Westinghouse's AC voltage system prevailed in electrification, and Thomas Edison had to admit that one of his biggest mistakes was to have stuck to direct current after the invention of the transformer in 1881. Edison's solution with 110 volts DC voltage could not be implemented economically in rural areas with long distances from the consumer to the power plant, nor could the inexpensive energy from remote hydropower plants be transported to the consumers.

The Westinghouse companies were commissioned in 1892 to supply their AC voltage system and a large number of a newly developed incandescent lamp, the so-called Westinghouse Stopper-Lamp , for the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 . It was a particularly prestigious business because this exhibition celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of America. The loss of that contract made 1892 a year of setback in Edison's career. He also lost financial control of his electrical company during this time.

Edison merged his companies on the advice of the manager Henry Villard until 1890 to the Edison General Electric Co. , because the previous group of companies could no longer be managed efficiently. The merger of the numerous companies to Edison General Electric Co. required a lot of capital for the purchase of company shares of third parties in the companies to be merged, which came from investors, including Deutsche Bank and Siemens & Halske . Edison had no controlling financial stake in Edison General Electric Co. He was a shareholder, had a seat on the board of directors, and was affiliated with the company by contract as an external inventor. A number of positions in the company were occupied by confidants of Edison, for example his former private secretary Samuel Insull was Vice President .

This company merged in 1892 with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric Co. This was necessary for financial reasons, because bad decisions such as with alternating current, expiring patents and high costs due to expansion and patent litigation put the company in a difficult position. The Thomson-Houston Co. brought the Edison missing, but necessary for further market participation rights to AC voltage patents and their experience with this technology in the merger. Chief of General Electric Co. was Charles A. Coffin, until then head of Thomson-Houston Co. had been. Elihu Thomson became the chief developer of the new company; Its developments and patents led to the success of General Electric Co. in the early years . Edison lost its influence and importance. The merger was initiated by the other shareholders of Edison General Electric Co. and their analysis of the company situation, in particular Bank Drexel, Morgan & Co. In the mindset of the banks, including those behind Thomson-Houston Co. , the reduction of competition resulted and the settlement of patent disputes through mergers on more reliable terms for investors. It's unclear when Edison was informed and whether he agreed or was coerced. His close associates, Samuel Insull and Alfred Tate, reported that he had been presented with a fait accompli and banned his popular name from being used for the new company. Edison officially supported the merger, albeit with dissociative statements such as that he no longer had time for electrical engineering anyway. Electrotechnical infrastructure and light bulbs only played a marginal role in Edison's continued inventiveness. Edison's partner Charles Batchelor , who was a shareholder in Edison companies and also became a shareholder in General Electric , served in the management of General Electric until 1899 .

As early as 1894 and 1895, Edison was constantly selling General Electric shares and using the proceeds to finance his developments and investments in other industries. He also bought back previously sold rights in the phonograph business and in the film business in order to regain control of his associated patents and their exploitation.

In 1891, the kinetograph , a forerunner of the film camera , was invented in Edison's laboratory . From 1896 he dealt with X-rays and the development of the fluoroscope with a calcium tungstate layer, which improved the image display compared to the solution by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen . Edison's colleague Clarence Dally died as a result of the experiments, and he himself suffered damage to his stomach and eyes.

In 1895 he founded the German Edison Phonograph Society , based in Cologne, together with his friend, chocolate manufacturer Ludwig Stollwerck, and other partners .

Kinetograph , Kinetoskop (playback device) and the first set up film studio in the world (the Black Maria , 1893) in West Orange made Edison the founder of the film industry. In 1893 he introduced 35mm film with perforations for transport, which became an industry standard. In 1894 the film " Chinese Opium Den " was made. A projection apparatus invented in 1897 made the film business one of his greatest financial successes. In Germany, Ludwig Stollwerck founded the German-Oesterreichische Edison-Kinetoskop-Gesellschaft in 1895 as a partner of Edison for the marketing of the kinetoscope. The films produced in the early years only mention the name Thomas Edison in the opening credits. However, this is to be understood as a brand name; Edison himself was hardly involved in film production. The whole development was probably inspired by Eadweard Muybridge and his invention of the zoopraxiscope . Edison's film studio technicians secretly made copies of the film Journey to the Moon .

However, entry into the iron ore business failed and was Edison's biggest failure. He had already developed a magnetic process for separating ore granules in the 1880s, tried to sell it in vain and then invested in some pilot plants with partners. In the 1890s he invested a great deal of the money he had earned in the electrical industry and a great deal of his time in the implementation of the large-scale exploitation of ores with a low iron content, which, however, never worked economically. The investment in process development became just as worthless as the purchased mining rights due to the discovery of iron ore deposits with a higher iron content. In 1900, the process ran for six months for the first time, but the ore could not be sold, and Edison closed his mine in Ogden, New Jersey. Edison presumably had taken a high risk because he wanted to compensate for the loss of influence over his electrical company with entrepreneurial success in another business area. Edison also sold his stake in the New York utility Edison Electric Illuminating Co. in 1897 to finance the failed iron ore business.

The new business activities with an association of around 30 companies and around 3,600 employees were initially combined under the National Phonograph Co. , founded in 1896 . In 1911 the reorganization was completed and the company was renamed Thomas A. Edison Incorporated .

The National Phonograph Co. achieved high sales figures from the late 1890s with a phonograph newly developed by Edison for the home sector. In particular, an inexpensive variant with a spring drive instead of an electric motor sold well. 25 years after the original invention of the phonograph, it was transformed into a consumer good in mass business. With the spread of the devices, the demand for sound carriers increased. For about 10 years Edison remained the market leader in the segment in the USA. Annual sales rose from around 5,000 units in 1896 to 113,000 units and 7 million records in 1904.

Although Edison spent most of his time and money developing capital goods for industrial customers such as electricity grids, telegraphy, telephones, and iron ore mining, manufacturing consumer goods for private consumers was his main source of income around the turn of the century. These new markets have only just emerged as a result of increasing leisure time and increasing prosperity as a result of industrialization. In addition to the invention and production of devices, business models had to be found and sales channels established. In particular, cost-efficient production and low prices were of great importance for the mass market. Edison worked intensively on the automation of the production of the phonograph and the reproduction of sound carriers.

Achievements and events from the turn of the century

Together with Ludwig Stollwerck , Edison developed the “Talking Chocolate” as a record with subscript and a phonograph (optionally made of sheet metal or wood) produced especially for children in 1903, which played music from such a chocolate record. This phonograph was called "Eureka", contained a Junghans wind-up clock mechanism and was sold in Europe and the USA. In addition to the chocolate records, those made of durable material were also offered.

With the improved phonograph rollers , especially the more cost-effective copying process of the cast gold rollers from 1902 and the longer playing time of the Amberol rollers from 1908, Edison was able to withstand the competition against the gramophone invented by Emil Berliner for a few years. The main competitor in the US was the Victor Talking Machine Company , which had well-known musicians such as Enrico Caruso under contract. Thomas Edison was of the opinion that the voices of well-known stage artists were not suitable for recording and produced well-known pieces of music with unknown performers that met his quality standards. Initially, only the brand name Thomas Alva Edison was on the recordings, and the performers were supposed to have as little part of the recordings business as possible. For direct competition with Berliner's record, Edison developed the Diamond Disc in 1911 , its own record format with subscript, and the associated record phonograph. The shellac record market expanded rapidly at that time; the offer grew enormously, especially in the lower price range. Despite its technical advantages, Edison's invention could not prevail because of the higher costs and the limited range. In addition, under the name Blue Amberol Record, he manufactured unbreakable phonograph cylinders made of celluloid and the very compact Amberola phonograph that went with it. In 1919 Edison had a market share of only 7.2% for devices and 11.3% for phonograms in the USA. The production of equipment and sound carriers for entertainment, including cylinder phonographs and sound cylinders, was discontinued in 1929. After that, the phonograph with cylinder was only marketed as a dictation machine. A correction system for dictation machines was patented as early as 1913, the Telescribe system (combination of telephone and phonograph) in 1914.

Until 1910, Thomas Edison was busy building cement works in Stewartsville, with rotary kilns , building prefabricated concrete houses and everyday objects made of concrete, such as furniture or a special phonograph. A rotary kiln he developed became an industry standard. His goal was a more economical cement production through automation, reduction of energy consumption and dimensioning of the daily production capacity to several times the capacity of cement production facilities at that time. The problems involved took years to deal with. In the 1920s, the Edison Portland Cement Co. was the largest producer in the United States and made a profit. Edison improved the quality of the cement by grinding the starting material more finely.

In 1912 the Kinetofon was patented, a combination of a film camera and phonograph (earlier sound film). Edison and other entrepreneurs founded the Motion Picture Patents Company in 1908, which was supposed to control the American film market through the patent rights of the companies involved and the General Film Company , founded in 1910 . A court ruling under the Sherman Antitrust Act ruled the company illegal in 1916. Expiring own patents and the loss of income from the film business in Europe as a result of the First World War led to high sales losses. While after 1900 films by Edwin S. Porter in particular ensured success, later production was no longer competitive. In 1918 Thomas Edison ended his entrepreneurial activities in the film business.

Thomas Alva Edison was friends with Henry Ford , who had started his career at Edison Illuminating Co. and who is said to have been encouraged by Edison to set up his own business in vehicle construction. Edison's intensive preoccupation with the further development of battery technology can be traced back to the requirements in automobile construction. Inadequate battery technology stood in the way of the electrification of automobiles. The known lead accumulators were too heavy in particular. The railways also had a need for rechargeable batteries. After preliminary work on the Edison-Lalande element and a long development period with many setbacks, the nickel-iron accumulator was perfected as a solution. The basic solution was found in 1904 and went into production. Customers were happy, but Edison was concerned about failure rates. He stopped production and invested another 5 years of development work in detail improvements. The Edison Storage Battery Company achieved a million dollar sales in its first year of production, which documents the market demand. The numerous and carefully documented experiments became an important database for the following generations of battery developers. As part of the battery development, Thomas Edison designed cars and rail vehicles with electric drives. He saw such vehicles as the most important future market for accumulators and electrical energy from power plants. The development of internal combustion engines, however, led to the displacement of the electric cars offered by various manufacturers at the time. The loss of this market, which initiated the development of the battery, was compensated for by the diverse other demand. The battery replaced the phonograph and film business as the foundation of Edison's business. Specifically, a compact battery developed in 1911 became the foundation of safe electric lamps for miners, another successful Edison product. In Germany, the German Edison Akkumulatoren Gesellschaft was founded in 1904 . The company went on in today's company Varta .

The USA obtained substances from the German chemical industry. With the outbreak of World War I, the supply stalled. This stimulated Edison's study of chemical engineering. In 1914 he set up factories for the synthesis of phenol (carbolic acid) from benzene for the production of records. In 1915 he built factories for the synthesis of aniline and para-phenylenediamine in a few weeks and in 1916 factories for the synthesis of benzidine base and sulfate.

Together with other inventors and scientists, Edison made himself available to the government after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by the German Imperial Navy in the First World War in order to develop defensive measures against German submarines. He became chairman of the Naval Consulting Board , which was supposed to examine proposals and inventions and implement them in prototypes.

From 1926 he withdrew from his company. His son Charles Edison became president of the parent company Thomas A. Edison Inc. in 1927. On the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1927, Thomas Edison was honored by visiting delegations from all over the world and by numerous awards.

For the last two decades of his life, Edison had frequent celebrity duties. He was visited by well-known personalities, invited to opening ceremonies and interviewed about current events.

The Edison Botanic Research Company was the last Edison founded in 1927. Were involved Harvey Firestone and Henry Ford. The company should because of the import US dependence on natural rubber are looking for national alternatives. The aging Edison got personally involved in this project with his proven working methods. A biological research laboratory was built in 1928 based on the model of his successful development facility Menlo Park . Around 17,000 plants were examined, a process for extracting rubber from goldenrod was developed and the project was handed over to the government. The process remained insignificant as synthetic materials reduced reliance on natural rubber.

Thomas A. Edison died on October 18, 1931, at his Glenmont home, Llewellyn Park, West Orange, New Jersey. US President Herbert Hoover asked the Americans to turn off the electric lamps in honor of Edison at the funeral, which were associated with his name like no other product in the public perception. In the presence of Lou Hoover , the wife of Herbert Hoover, as well as Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone, he was buried in Rosedale Cemetery in Orange, New Jersey, on October 21, 1931, on the 52nd anniversary of the date on which the practical incandescent lamp was invented October 1879.

Weltanschauung, politics, culture

Edison was politically a supporter of the Republican Party . He supported Republican Presidents Theodore Roosevelt , Warren G. Harding , Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, among others . In 1912 he spoke out in favor of introducing the right to vote for women in the USA. Edison had no schooling himself. He criticized the American education system and expressed disdain for the value of subjects such as Latin. He saw the training of practically skilled engineers as his main task.

Edison personally decided on the pieces of music and performers offered on his phonograms. However, he had an aversion to jazz music. The hearing-impaired since his youth is also said to have selected interpreters according to the intelligibility of sung texts. As time went on, choosing based on personal preferences rather than market demand became an economic disadvantage for his companies.

He advocated a philosophy of nonviolence. On April 4, 1878, he joined the Theosophical Society . But even though he opposed the death penalty , his company took on a government contract to develop the electric chair . Edison emphasized several times that he had never dealt with the invention of weapons.

Thomas Edison criticized Christian religious ideas and campaigned against religious instruction in schools. He is quoted in newspapers as saying "Religion is all bunk ... All bibles are man-made." (All religion is gossip ... All Bibles are man-made.) In October 1910, statements by him in the United States attracted attention in which he had ideas about the Rejected the existence of a soul and its immortality. His second wife, a devout Methodist , tried in vain to change his mind; he remained a religiously independent free thinker.

Paul Israel, who was involved in researching the sources of Edison, points out that his view of the Jews was nuanced and that there was no evidence of a correspondence with the anti-Semitic publications of his friend Henry Ford. Edison saw social conflict as a result of centuries of persecution of the Jews and assumed that these problems would go away on their own in time as Jews in America were no longer persecuted. However, Edison shared common prejudices about Jews, such as that they had supernatural business acumen.

family

Thomas Alva Edison's parents are Samuel Ogden Edison, Jr. (1804–1896) and Nancy Matthews Elliott (1810–1871). In his first marriage, he was married to Mary Stilwell (1855-1884) from 1871 until her early death. The marriage had three children: Marion Estelle Edison (1873-1965), Thomas Alva Edison Jr. (1876-1935) and William Leslie Edison (1878-1937). In his second marriage, Thomas Alva Edison was married to Mina Miller (1865-1947) from 1886 until his death in 1931. This marriage also resulted in three children: Madeleine Edison (1888–1979), Charles Edison (1890–1969) and Theodore Miller Edison (1898–1992).

Best known in public was Thomas Edison's son Charles Edison, who as a politician of the Democratic Party was temporarily governor of New Jersey and US Secretary of the Navy . His daughter Marion was married to the German lieutenant Oscar Oeser and lived in Germany from 1895 to 1925.

Inventions, innovations, aftermath

Invention and development

Edison has filed a total of 1,093 patents in the course of his life, along with others along with other researchers. In 1882 alone, he submitted almost 70 new inventions to the patent office.

Working method

The laboratory operated by Edison in Menlo Park is widely regarded as the forerunner and role model of the emerging industrial research and development departments of technology companies.

Finding a suitable material to make charcoal filaments is an example of Edison's working methods. His co-workers found that fibers from fast-growing tropical plants would do well. Edison then financed an expedition to collect such plants. The properties of the plant fibers were examined in extensive test series and after 18 months the Japanese bamboo species Phyllostachys bambusoides , which is called "Madake" there, was determined to be the most suitable. Patent 251,540 is dated December 27, 1881.

The records of the experiments carried out at that time for the development of the incandescent lamp and the electrotechnical infrastructure are said to comprise 40,000 pages. The empirical development of the solutions sought in extensive test series combined with the understanding that every failure brings the solution closer is an important reason for Thomas Edison's invention successes.

An empirical paper examined the relationship between Edison's creative productivity and the number of projects he worked on. In particular, the research found a positive correlation between the number of projects and Edison's inventive productivity over the same period. This positive correlation increased when Edison's age was included as an additional variable. By working on projects on different topics at the same time, Edison always had the opportunity to channel his efforts as soon as he encountered temporary obstacles, especially during long periods of trial and error in which only multiple failures followed.

The ability to find and involve competent employees for upcoming problems is another reason. For many years his most important partner was the Englishman Charles Batchelor , who is considered to be particularly skilled at carrying out experiments. Its special position among the employees is evident from its participation of 10% in the proceeds from all inventions. The precision mechanic John Kruesi worked for Edison from 1872 and was involved in the implementation of numerous construction drawings and sketches. The glassblower Ludwig Karl Böhm from Lauscha , who had previously worked with the inventor of the vacuum pump Heinrich Geißler in Germany , was the first specialist in this field in his team. Technician and organizer Sigmund Bergmann , mathematician and physicist Francis Robbins Upton , chemist Otto Moses, and electrical engineer Harry Ward Leonard are other examples of incorporating expertise to advance Edison's business goals. Inventors like Lewis Howard Latimer , who had already acquired his own patents in the field of incandescent lamp development, also worked for Edison companies. However , Edison did not recognize Nikola Tesla's talent . He left the dispute and became an important employee of his competitor Westinghouse Electric . Tesla later criticized Edison's unscientific way of working as inefficient.

The inventions in Menlo Park and later in West Orange were patented under the name of Thomas Edison, but for the most part developed by a team of craftsmen, engineers and scientists under his direction. Kinetoscope and kinetograph , for example, are considered inventions by William KL Dickson, who works in the Edison laboratory . The shares of individual employees in the team in creative achievements cannot be precisely determined. In traditional public communication, the image of Thomas Edison as the sole intellectual author of the inventions was inaccurate. Technological leadership, organization and financing were the focal points of his inventions related achievements from 1875.

Edison is described as a charismatic personality. Menlo Park employees later said he made them feel like partners, not employees. With relatively low pay, Edison offered his employees the prospect of shares in companies that were later to be founded according to their performance. When the first successes emerged in the development of the incandescent lamp and the electrical infrastructure, even the smallest proportions of his employees already had the equivalent of several annual salaries. The combination of a charismatic person with a natural authority, team spirit and the financial participation of the employees were decisive for their high motivation and the ensuing success. Edison himself supervised the few regulations such as the recording of all experiments carried out in the laboratory books.

This form of organization and cooperation, which was successful in the development area and tailored to the person of Edison, proved to be largely unsuitable for the emerging company with several thousand employees. It was only when the various Edison companies founded in the 1880s were combined to form Edison General Electric Co. in 1890 and General Electric was founded in 1892 that the deficits in organization, reporting and management could be eliminated. However, this cost Edison a serious loss of influence on the companies he founded. These were temporarily without management in the 1880s, as Edison was absorbed in technical problems and did not take care of the mail and necessary decisions.

Another characteristic of Edison's inventiveness is the buying up of patents, which were supplemented by further developments in new patents.

The invention process he established is sometimes referred to as the "invention of the invention" and Menlo Park himself is described as an important invention. The merging of scientific experimental facilities with workshop facilities of various trades, putting together a team with a broad coverage of knowledge and craft skills and the organization of working conditions that promote the creativity of all employees are not only considered reasons for Thomas Edison's success today, but also as groundbreaking for the technology companies of the 20th century. Menlo Park was copied by many industrial companies and was particularly the model for Bell Laboratories .

Thomas Edison commented on his recipe for success with the words:

"Genius is one per cent inspiration and ninety-nine per cent perspiration.

Ingenuity consists of one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration . "

“I'm a good sponge, I soak up ideas and make them usable. Most of my ideas originally belonged to people who didn't bother to develop them. "

His type of management, which worked under the conditions of daily personal communication in the laboratory, but was a likely cause of problems in his group of companies, he commented without doubt:

“There is no organization; I am the organization.

There is no organization. I am the organization. "

Selected inventions

| Area | Number of patents |

|---|---|

| Light bulb, energy | 389 |

| Phonograph | 195 |

| Telegraph | 150 |

| battery | 141 |

| Metal extraction | 62 |

| cement | 40 |

| phone | 34 |

| railroad | 25th |

| Movie | 9 |

| automobile | 8th |

| mimeograph | 5 |

| typewriter | 3 |

| military | 3 |

| chemistry | 3 |

| radio | 2 |

| Others | 24 |

- 1868: Electric vote counter for meetings

- 1869 stock price indicator , pressure telegraph (Stock Ticker)

- 1874: Quadruplex transmission technology for telegraphy

- 1876: Electric pen

- 1877: phonograph

- 1877: Grain microphone (for telephone)

- 1879: carbon filament lightbulb, light bulb

- 1880: Magnetic metal separator

- 1881: Edison thread (screw socket for light bulbs)

- 1881: electricity meter

- 1882: System for the distribution of electrical energy ( single-phase three-wire network )

- 1883: Application of the Edison effect for a device for voltage display and regulation

- 1888: electric chair

- 1888: Phonograph cylinder with subscript

- 1891: Kinetograph

- 1891: Kinetoscope

- 1897: projection kinetoscope

- 1900: Rechargeable galvanic cell

- 1902: Phonograph cylinder (Gold Molded Record)

- 1903: Rotary kiln for cement production

- 1911: Diamond Disc (record format)

- 1914: Nickel-iron accumulator

(In each case calendar year of the first patent application. Further patent applications for improvements to the original invention often took place over many years. Invention, patent application, patent grant and start of marketing can fall in different calendar years. Different information in publications has its cause. The then patent system of the USA saw also the registration of reservations on inventions in progress. For the patent on the kinetograph, for example, a reservation was filed in 1891, it was granted in 1897.)

An Edison invention is still present in every private household today: the so-called Edison thread , with which incandescent lamps or compact fluorescent lamps ("energy saving lamps ") and, as the most recent development, LED lamps can be screwed into the corresponding socket. The thread , which used to be made of sheet brass , is now mostly made of plastic, is characterized by simple production and safe handling, even for laypeople . The solution is said to go back to an idea by Thomas Alva Edison from 1881, which he then developed together with Sigmund Bergmann in his Bergmann and Company's shop in New York. The first patent was granted on December 27, 1881 in the patent 251554. The lamp base was produced in a joint company. Bergmann sold his shares to Edison in 1889 and went back to Berlin. The solution is still frequently used in successor products to the incandescent lamp and for other light sources.

Edison didn't always develop his inventions into products. With the patent 465,971 "Means for the transmission of electrical signals", applied for in 1885 and issued in 1891, he owned a basic patent for wireless telegraphy. In 1903 he sold it to his friend, Guglielmo Marconi , who was able to protect his own patents against copyright claims by previous inventors.

The tasimeter for fine thermometric observations is an example of an unpatented invention by Edison. Publication without a patent application means release to the general public for use without copyright remuneration.

Thomas Edison's unsuccessful inventions include some bizarre ideas like making furniture and pianos out of concrete. The patented preservation of fruit in evacuated glass containers derived from the manufacture of incandescent lamps was also unsuccessful at the time.

Implementation in innovations

Social transformation using the example of electrical inventions

The technical solution and the possible use of an invention are not sufficient for a successful innovation process . The transformation of a technical achievement into a social process that leads to a positive evaluation by consumers, investors and politicians is a difficulty that often causes innovations to fail. Successfully addressing these issues is an essential part of Thomas Edison's overall accomplishment in introducing electric light.

Edison, like other inventors and scientists, faced communication problems when it came to innovations, as many of the terms related to the innovations, such as dynamo, fuse, direct current or incandescent lamp, were unknown to large parts of the population and most of them had no idea about the nature of electricity. In addition to consumer acceptance, it needed the trust of investors and politicians. The latter could have delayed the electrification of New York for years with safety concerns about laying underground electricity cables. Ultimately, the resistance of the gas industry and its lobbying in politics had to be overcome.

He solved the task through personal contacts with decision-makers and the press, using his charismatic personality, his self-confidence, his rhetorical skills and his popularity for his goals. In contrast to the development work in Menlo Park , Edison had to communicate with a large number of actors for the implementation of his electrification project, present his project in terms of investors, building authorities, etc. and ensure that all actors cooperate.

He countered the problem of the lack of comprehensibility of the innovations through non-verbal communication such as show events with light effects. The company founded in New York was not called "Electricity Company" but "Lighting Company" (Edison Illuminating Co.) . The power plant was called "light plant", and Edison was communicating with it that you provide light and not electricity; linguistically he built on what people knew. Since consumers would have mistrusted an unknown physical unit for electrical energy such as ampere-hour as the basis for billing, a conversion into lamp hours was carried out; Edison introduced the unit Lh (about 0.8 Ah ) for this . Great importance was attached to the design of lamps, so that they were perceived as beautiful from the start, in line with contemporary tastes, and were perceived as enhancing the personal environment. The design of the light bulb itself as a pear with a screw thread is still considered aesthetically successful. The light bulb became an iconographic symbol for “idea”, “enlightenment”, etc. The operators of theaters were particularly open to the innovation. As a result, electric light was present at an early stage in focal points of public life and perceived in connection with culture and entertainment.

The integration of the innovation into an existing cultural system of concepts, meanings and values was essential for success. The transformation of this invention into an everyday object on various levels of society was particularly successful. Charles Bazerman, a university professor from the United States, analyzes aspects of this in his book The Languages of Edison's Light .

Patent litigation - a side effect of successful innovations

Thomas Edison made more than 2000 inventions, 1093 of which he patented in the USA . By October 1910, 1239 patents had been registered abroad, 130 of them in Germany. The inventions relate not only to innovative consumer products, but also to machines and processes for their production, process engineering, capital goods and other areas.

Edison mostly sold the rights of commercial use of his patents to companies that belonged to him or in which he was a partner, such as As the Edison Electric Light Co. The Edison Electric Light Co. then sold in turn limited rights to electrification companies, manufacturers or foreign patent exploiter on.

The number of patents developed by Edison made it increasingly difficult for competitors in the electronics market in the 1880s to develop products that were not affected by them. The rapid technological changes and the high economic value of the inventions as a result of the successful innovation process led to widespread disregard for patents. This forced the respective beneficial owners of the patents granted to Edison to spend large sums of money on the legal defense of their property. At times, Edison's companies were no longer financially able to do so. The pressure to enforce the exclusive rights of use sold to third parties weighed heavily on Edison Electric Light Co. and Thomas Edison.

In particular, financially strong companies have been able to afford years of legal disputes across all instances and continue to infringe patents in pending proceedings. The benefits of participating in the market evidently exceeded the legal costs incurred. The infringers were also able to use the duration of the proceedings to develop circumvention techniques. According to the Edison biographers Dyer and Martin, between 80 and 90 lawsuits have been carried out for incandescent lamp patents and at least 125 further patent processes for inventions related to the incandescent lamp in the electrotechnical infrastructure. In 1889, Edison had to set up his own division for the control and administration of the procedures.

To date, there is no known patent litigation that resulted in a court-ordered cancellation of a patent granted to Edison by the US Patent Office. The numerous challenges were a means of competing for market share. Edison attributed the necessary merger of his companies with Thomson-Houston Co. to high costs for patent litigation and reduced earnings from patent infringements.

The patent process of the Edison Electric Light Co. against the United States Electric Lighting Co. lasted from 1885 to 1892 and is said to comprise about 6,500 pages of files. It ended with the Edison incandescent lamp patents being ratified in all courts. The company United States Electric Lighting Co. was able to continue production because at the end of the process a new incandescent lamp had been developed that did not infringe any Edison patent. The United States Electric Lighting Co. got into financial difficulties in the meantime, but was able to afford the legal dispute and expensive new developments, since the railroad industrialist George Westinghouse bought the company in 1888. The argument between Thomas Alva Edison and George Westinghouse had a cause here.

In methods of the Edison Electric Light Co. against the Beacon Vacuum Pump and Electric Co., the Electric Manufacturing Co. and the Columbia Incandescent Lamp Co. was claimed originally from Germany Heinrich Göbel had already invented the light bulb before Thomas Edison, see there Section on patent litigation with “Goebel Defense” .

aftermath

Summary of the innovation consequences

Robert Rosenberg and Paul Israel believe that Thomas Edison did not invent the modern world, but that he was involved in its creation. Edison biographer Robert Conot describes Edison's accomplishment by saying that he pushed the door open.

The consequences of the innovations emanating from Edison in this sense have an extraordinary dimension. Global and temporal changes occurred through electrification and media for sound and image. New industries sprang up around the world. The perception of the world changed through moving images; with the cinemas, new cultural centers emerged in the cities. The electric light changed social life, which shifted into the evening hours; Shift work also increased due to the better light. The electricity grids made it possible to rationalize manufacturing processes and lead to greater prosperity. The carbon filament lamps developed by Edison were the first electrical products to find widespread use in private households, and which paved the way for today's extensive household electrification. The rechargeable batteries he developed brought about another wave of electrification, especially of cars, ships and railways. Edison was involved in the global innovation of the telephone with changed processes, for example in retail, with inventions that were an industry standard until the introduction of digital telephony in the 1980s.

The enormous changes are made clear by an event leading to the death of Edison. The President of the USA Herbert Hoover wanted to shut down the country's power plants for a short time in Edison's honor. In 1931, however, that was no longer possible.

Cultural influence of inventions using the example of the phonograph

While Thomas Edison initially saw the use of the phonograph in the office as the main application, the Pacific Phonograph Co. in San Francisco in 1889 had great success with a coin-operated phonograph for entertainment purposes. This business model spread rapidly in the United States. As early as 1890 there are said to have been around 1500 such phonographs in pubs, restaurants, ice cream parlors, etc., where people consumed music on hearing tubes for a fee. In Germany, showmen copied the business model and, thanks to the large influx, were able to amortize their investments in a short time and generate high profits. While the operators initially had to produce their own rollers for their customers' musical tastes, a new industry for the production and marketing of sound carriers emerged in parallel with the change in music consumption. The success of the coin operated phonograph led to the construction and manufacture of inexpensive phonographs for the home; Devices and sound carriers were a mass business around 1900.

Thanks to the phonograph, music became available in terms of location and time independent of concert events. Among other things, this resulted in an increased influence among musicians and an accelerated spread of some musical styles. The pubs with phonographs in the USA, for example, increased the spread of African-American music, some of which was previously only known in the local area of the work of the respective sound artists.

This effect quickly became a global phenomenon; Music was produced specifically for the world market. Some authors therefore see the invention of the phonograph as the beginning of the cultural globalization of music. The cultural significance of the invention for music is assessed as being comparable to the significance of the invention of printing for literature. Both inventions have led to a new dimension of exchange and mutual influence between cultures.

Success as a businessman, fortune

In the usual lists of entrepreneur billionaires, contemporaries such as Henry Ford (automobile manufacture), Jason Gould (owner of railway lines such as Union Pacific Railroad) or John D. Rockefeller (petroleum) appear, but not Thomas Edison. His attempt to gain a dominant position with light bulbs and electrical infrastructure had failed. In companies that were founded in the 1880s, Edison was often only a partner, even if they bore his name. Partners, employees and investors built factories, organized electrification projects and held company shares. These companies paid royalties for the use of Edison patents, which was a major source of income for Thomas Alva Edison. Most of the electrical companies formed in the 1880s merged into General Electric , where he was a shareholder without controlling the company ( no source is available on his stake in General Electric ). His later company, Thomas Alva Edison Inc. , remained under the control of the family during Thomas Edison's lifetime. Most patents had expired and many inventions were technically obsolete. W. Bernard Carlson, professor of technology at the University of Virginia , sees Edison's lack of understanding of the software side of the industries he founded, with the result that he had to give up business areas such as phonograms and films while still alive. The early inventions of telegraphy, which he sold for a few thousand dollars each, made big profits for others. Edison companies did not benefit from the sales and profit growth in other industries as a result of electrical inventions, for example copper producers.

The biographers Dyer and Martin describe Edison as an ingenious solver of technical problems, but not as a great corporate strategist. You even find a carelessness and negligence on his part in business matters as well as a gullible trust in contractual partners. One consequence of this was that Edison did not earn a penny from the exploitation of his electropatents in England and Germany. The biographer Paul Israel sees on the one hand a great interest on the part of Thomas Edison in the development of technologies and the establishment of new industries, on the other hand, however, a disinterest in the day-to-day business of companies that have been founded and a faulty management that can be blamed on the necessary reaction of his companies to changed market conditions and technological change. As a result, his companies were only dominant in the market for a short time. As a businessman, Edison was "moderately successful" in the assessment of Paul Israel.

The Great Depression , which began in 1929, fell into Edison's last years and probably had a huge reduction in the value of his fortune at the time of death.

Influenced founders and careers

Some men who were at times employees of Thomas Edison later became inventor-entrepreneurs themselves:

- Sigmund Bergmann (electricity, turbines, vehicle construction),

- Robert Bosch (electricity),

- Henry Ford (automotive engineering),

- Sigmund Schuckert (electricity).

Many Edison lab workers have had successful careers. Examples are:

- Francis Jehl . He was hired as a laboratory assistant at Menlo Park. Because of his skill, he became a close associate of Edison and later worked on electrification projects in Europe for decades.

- Samuel Insull . Thomas Edison's private secretary became president of the Chicago Edison Co. and the Commonwealth Edison Co. Later he was responsible for standardizing the electrical infrastructure in North America.

- William Joseph Hammer .

Honors (selection)

In recognition of Thomas Edison's achievements, the United States has been celebrating National Inventor's Day on his birthday since 1983 . A star was dedicated to him on the Hollywood Walk of Fame . Numerous institutions and streets, also in Germany, were named after him.

- 1889: Appointed Commander of the Legion of Honor by the French President

- 1904: A group of Edison's friends and coworkers issued the Edison Medal in commemoration of the first electric incandescent lamp 25 years earlier . It has been awarded annually by the American Institute of Electrical Engineers since 1908 and by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers since 1963 .

- 1909: Edison was awarded the gold medal by the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences

- 1922: Edison received an honorary doctorate from Rutgers University

- 1927: Membership in the National Academy of Sciences

- 1928: Awarded the " Special Congressional Medal " to Edison (prestigious US award)

- 1929: Celebrations on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the invention of the practical incandescent lamp. Henry Ford had the Menlo Park laboratory reconstructed and Thomas Edison repeated the historic incandescent lamp demonstration of October 21, 1879 in the presence of the American President Herbert Hoover and well-known personalities, among them Marie Curie . The event was broadcast on the radio; Special postage stamps and first day covers labeled with them helped make the event a national event in the United States. (In Germany, where Heinrich Göbel was thought to be the inventor of the practically usable incandescent lamp, associations of the electrical industry responded with a celebration in his native town of Springe on September 14, 1929, a few weeks before the event in the USA.)

- around 1931: Name of the asteroid (742) Edisona after him

- around 1933: John Kunkel Small (1869–1938), curator of the Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden , named the Edisonia plant genus after him , which is now part of the Matelea genus ( silk plant family ). Thomas Edison was elected to the board of directors of the New York Botanical Garden in 1930 .

- 1940: Biographies The Young Edison with Mickey Rooney and The Great Edison with Spencer Tracy in the lead roles

- 1961: The moon crater Edison is named after him

- 1977: Presentation of the Grammy Trustees Award

In early November 1915, newspapers, including the New York Times , reported on the impending award of the Nobel Prize in Physics to Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison in equal shares. In fact, the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to William Henry and William Lawrence Bragg .

state of research

Historian Keith Near said in 1995 that of all famous people, Thomas Edison was the least known about. What most people thought they knew about him were nothing more than fairy tales. Since the lifetime of Thomas Edison, representations have been handed down that are interspersed with legends, which journalists freely invented for the decoration of their articles or Thomas Edison and his employees for the purpose of self-expression. Furthermore, a wealth of errors have entered the traditional representations.