depression

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F06.3 | Organic mood disorders |

| F20.4 | Post-schizophrenic depression |

| F25.– | Schizoaffective Disorders |

| F31.– | Bipolar Affective Disorder |

| F32.– | Depressive episode |

| F33.– | Recurrent depressive disorder |

| F34.- | Persistent mood disorders |

| F41.2 | Anxiety and Depressive Disorder, mixed |

| F53.0 | Mild psychological and behavioral disorders associated with the puerperium , not elsewhere classified |

| F92.0 | Conduct disorder with depressive disorder |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The depression (Latin depressio of Latin deprimere "depressing") is a mental disorder or disease. Typical symptoms of depression are low mood , brooding , feelings of hopelessness, and decreased drive . Often joy and pleasure, self-esteem , performance , empathy and interest in life are lost. This often affects the joy of life and quality of life .

These complaints also occur in healthy people in the context of grief after an experience of loss and do not have to differ in appearance from depression; however, they usually go away on their own. Illness is present if the symptoms persist for a disproportionately long time or if their severity and duration are not proportionate to the factors triggering the symptoms.

In psychiatry , depression is assigned to mood disorders . The diagnosis is made based on symptoms and course (e.g. one-off or repeated depressive episode). The standard treatment for depression includes psychotherapy and, from a certain degree of severity, also the use of antidepressants .

In everyday parlance, the term depressive is often used for a normal, sad, depressed mood without any disease value (the correct technical term would be depressed ). In the medical sense, however, depression is a serious disease that requires treatment and often has serious consequences that cannot be influenced by the willpower or self-discipline of the person concerned. It is a major cause of incapacity for work or early retirement and is involved in around half of the annual suicides in Germany.

distribution

An international comparative study from 2011 compared the incidence in high-income countries with that in middle and low-income countries. The lifetime prevalence was 14.9% in the first group (ten countries) and 11.1% in the second group (eight countries). The ratio of women to men was roughly 2: 1.

A meta-analysis of 26 studies with data from 60,000 children born between 1965 and 1996 showed a prevalence of 2.8% for the age group under 13 and a prevalence of 5.6% for the age group 13-18 (girls 5.9%, boys 4 , 6%).

The burden of illness caused by depression, for example in the form of inability to work, inpatient treatment and early retirement, has risen sharply in Germany in recent years. It is assumed that the actual frequency of illness has changed much less seriously and that the increased occurrence is due to better recognition and less stigmatization of people with mental disorders. The diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, which have become lower threshold over time, are also critically discussed as a partial cause. On the other hand, the results of long-term studies tend to suggest a real increase that is associated with various social influencing factors.

In Germany too, according to health insurance data, younger generations seem to be more at risk of suffering from a mental disorder in the course of their lives. According to the Techniker Krankenkasse, the average length of incapacity for work of the insured patients in 2014 was 64 days (in comparison: an average of 13 days for all diagnoses). Of the ten groups with the highest incidence rates, seven belong to the occupational area of health, social affairs, teaching and education. By a long way, employees in call centers head the list; followed by carers for the elderly and nurses, educators and child carers, employees in public administration and employees in the security industry. University teachers, software developers and doctors are comparatively less susceptible. Women are affected almost twice as often as men. From 2000 to 2013, the number of prescribed daily doses of antidepressants almost tripled. In regional terms, Hamburg (1.4 days of incapacity for work per insured employee), Schleswig-Holstein and Berlin (1.3 days each) top the list. In Hamburg, 9.2 percent of all days of incapacity for work are caused by depression. In southern and eastern Germany the rates are lower on average. According to the Barmer GEK, 17 percent of students who were previously considered to be a relatively healthy group are now affected by a psychiatric diagnosis (around 470,000 people), especially older ones .

Signs

Symptoms

In 2011, several specialist societies such as the German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology (DGPPN) developed a care guideline on the subject of depression. She recommends distinguishing between three main and seven additional symptoms for diagnosis according to ICD-10.

The main symptoms are:

- Depressed , depressed mood : Depression is characterized by a reduced mood or, in the case of severe depression, the “feeling of numbness” or the feeling of persistent inner emptiness.

- Loss of interest and joylessness : loss of the ability to be happy or sad; Loss of affective resonance, that is, the patient's mood cannot be lightened by encouragement

- Lack of drive and increased fatigue: Another typical symptom is inhibition of drive. In the case of a severe depressive episode, those affected can be so inhibited in their drive that they can no longer perform even the simplest activities such as personal hygiene, shopping or washing up.

The additional symptoms are:

- decreased focus and attention

- decreased self-esteem and self-confidence ( feeling of insufficiency )

- Feelings of guilt and inferiority

- Negative and pessimistic prospects for the future (hopeless): Characteristic are exaggerated concern about the future, possibly exaggerated anxiety due to minor disturbances in the own body (see hypochondria ), the feeling of hopelessness, helplessness or actual helplessness

- Suicidal thoughts or actions: Those severely affected often feel that their life is completely meaningless . This excruciating condition often leads to latent or acute suicidality .

- sleep disorders

- decreased appetite

In addition, there may be a somatic syndrome :

- Loss of interest or joy

- lack of ability to react emotionally to the environment

- Early morning awakening: Sleep is disturbed in the form of premature awakening, at least two hours before the usual time. These sleep disorders are an expression of a disturbed 24-hour rhythm. The disruption of the chronobiological rhythm is also a characteristic symptom.

- Morning low: The sick person is often particularly bad in the mornings. In the case of a rare variant of the disease, the opposite is true: a so-called "evening low" occurs, that is, the symptoms intensify towards evening and it is difficult to fall asleep or only possible towards morning.

- Psychomotor inhibition or agitation : The inhibition of movement and initiative is often associated with inner restlessness, which is perceived physically as a feeling of suffering and can be very tormenting (silent excitation, silent panic ).

- significant loss of appetite ,

- Weight loss, weight gain ("grief fat"),

- sexual interest can also decrease or cease (loss of libido ).

Depressive illnesses are occasionally accompanied by physical symptoms, so-called vital disorders , pain in very different parts of the body, most typically with a painful feeling of pressure on the chest. The susceptibility to infection is increased during a depressive episode . Social withdrawal is also observed, thinking is slowed down (thought inhibition), senseless circles of thought ( compulsion to brood ), disturbances in the sense of time . Often there is irritability and anxiety . In addition, there may be an oversensitivity to noises .

Severity

The severity is classified according to the ICD-10 according to the number of symptoms:

- mild depression: two main symptoms and two additional symptoms

- Moderate depression: two main symptoms and three to four additional symptoms

- severe depression: three main symptoms and five or more additional symptoms

Gender differences

The symptoms of depression can develop in different ways in women and men. The differences in the core symptoms are small. While phenomena such as discouragement and brooding are more likely to be observed in women, there is clear evidence in men that depression can also be reflected in a tendency to aggressive behavior. In a 2014 study, the different manifestations in women and men were associated with differences in the biological systems of the stress response .

In children and adolescents

The recognition of symptoms of depression in preschool children has now been relatively well researched, but it requires a few specifics to be considered. The same applies to school children and young people. The prevalence of depression in children is around three percent, and around eighteen percent in adolescents. The symptoms are often difficult to recognize in children and adolescents because they are overlaid by behavior patterns typical of their age. This complicates the diagnosis.

The same diagnostic codes apply to children and adolescents as to adults. However, children can have a marked tendency to deny and feel great shame. In such a case, behavioral observation and parenting questions can be helpful. The family burden with regard to depressive disorders and other disorders should also be taken into account. In connection with depression, an anamnesis of the family system after relationship and attachment disorders, as well as early childhood deprivations or emotional, physical and sexual abuse is often created.

The further diagnostic steps can also include a survey of the school or kindergarten regarding the state of the child or adolescent. Often an orienting intelligence diagnosis is also carried out, which is intended to reveal any over- or underload. Specific test procedures for depression in children and adolescents are the Depression Inventory for Children and Adolescents (DIKJ) and the Depression Test for Children (DTK).

diagnosis

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F32.0 | Slight depressive episode (the patient feels ill and seeks medical help, but can still meet his professional and private duties despite the loss of performance, provided that it is routine.) |

| F32.1 | Moderate depressive episode (professional or domestic requirements can no longer be met or - with daily fluctuations - only temporarily). |

| F32.2 | Severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms (the patient requires constant care. Clinical treatment is necessary if this is not guaranteed). |

| F32.3 | Severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms (As F.32.2, combined with delusional thoughts, e.g. absurd feelings of guilt, fears of illness, madness of poverty, etc.). |

| F32.8 | Other depressive episodes |

| F32.9 | Depressive episode, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Since depression is a very common disorder, it should already be recognized by the family doctor , but this only works in about half of all cases. Sometimes the diagnosis is first made by a psychiatrist , a doctor specializing in psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy, or a psychological psychotherapist . Because of the particular difficulties in diagnosing and treating depression in childhood, children and adolescents suspected of having depression should always be examined by a specialist in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy or by a child and adolescent psychotherapist .

Common methods for assessing the severity of a depressive episode are the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), a third-party assessment method , the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a self- assessment method , and the Depressive Symptoms Inventory (IDS), which is divided into a third-party and a Self-assessment version is available.

Sometimes a depression is masked by another illness and not recognized.

In the ICD-10 , depression falls under the code F32 .–- and is referred to as a "depressive episode". In the case of recurring depression, this is classified under F33.– , in the case of alternation between manic and depressive phases under F31.– . The ICD-10 names three typical symptoms of depression: depressed mood, loss of interest and joy, and increased fatigue. According to the course, the current ICD-10 classification system differentiates between the depressive episode and the repeated ( recurrent ) depressive disorder .

questionnaire

According to the S3 guideline for unipolar depression, the following questionnaires are recommended for screening:

- " WHO-5 questionnaire on wellbeing"

- "Health questionnaire for patients (short form PHQ-D)"

- General Depression Scale (ADD).

- Another way of quickly identifying a possible depressive disorder is the so-called " two-question test ".

The following questionnaires are recommended in the guideline on progress diagnosis, i.e. to determine to what extent the therapy is responding and the symptoms are improving:

Self-assessment questionnaires:

- the patient health questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire-Depression (PHQ-D);

- the Depression Screening Questionnaire (DIA-DSQ);

- the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI or BDI-II);

- the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS);

- Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS);

- Questionnaire for the diagnosis of depression according to DSM-IV (FDD-DSM-IV).

Questionnaires for external assessment:

- Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS);

- Bech Rafaelsen Melancholy Scale (BRMS);

- Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).

Differential diagnostics

A differential diagnosis is used to try to rule out possible confusion with one of the following diseases or disorders:

- Dysthymia

- Bipolar disorder

- Borderline personality disorder

- Adjustment disorder

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- Dependence syndrome due to psychotropic substances

- Pernicious anemia , vitamin B12 deficiency

- Disease of the thyroid

- other anemia

- Fructose malabsorption

Different shapes

The ICD-10 diagnostic scheme is currently mandatory in medical practice. The severity of depression is differentiated there by the terms light, moderate and severe depressive episode , with the latter with the addition of with or without psychotic symptoms (see also: diagnosis ).

According to the ICD-10 diagnostic scheme, chronic depression is classified according to severity and duration into dysthymia or recurrent (repeated) depression . The DSM-5 is more precise here, as existing chronic depressive moods can be accompanied by additional depressions in phases. Within the DSM-5 this is called “double depression”. There, however, the exclusion of grief reactions as a diagnostic criterion was lifted.

Organic depression (ICD-10 F06.3 - "Organic affective disorders") is the name of a depressive syndrome that is caused by a physical illness, for example thyroid dysfunction , pituitary or adrenal disorders , stroke or frontal brain syndrome . Organic depression, on the other hand, did not include depression as a result of hormonal changes, e.g. B. after pregnancy or during puberty . “A depressive episode must be… distinguished from an organic depressive disorder . This diagnosis is to be made (primarily) if the affect disorder is very likely to be the direct physical consequence of a specific disease factor (e.g. multiple sclerosis , stroke, hypothyroidism ). ”This gives the doctor giving further treatment indications that a somatic disease is the underlying cause of depression and must be taken into account in diagnosis and treatment (and depression is not the cause of functional or psychosomatic complaints).

Historical forms

The reactive depression is seen as a response to a stressful event to date and now as a possible symptom of an adjustment disorder : diagnosis (ICD-10 F43.2).

The term endogenous depression encompasses a depressive syndrome without any recognizable external cause, which was mostly attributed to altered metabolic processes in the brain and genetic predispositions (endogenous means originated within). Today it is referred to as a form of affective psychosis in everyday clinical practice .

The neurotic depression or exhaustion depression is said to be caused by long-lasting stressful experiences in the life story.

Anaclitic depression ( anaclitic depression = dependence on another person) was seen as a special form of depression in babies and children if they were left alone or neglected . The anaclitic depression manifests itself through crying, whining, persistent screaming and clinging and can lead to psychological hospitalism .

The somatized (≠ somatic) depression (including masked or larval depression called) is a depression in the physical discomfort the disease dominated. The depressive symptoms remain subliminal. Symptoms in the form of back pain , headache , tightness in the chest region , dizziness and much more are described. The most varied of physical sensations acted as "presentation symptoms" of depression. The frequency of the diagnosis of “masked depression” in general practitioners was up to 14% (every seventh patient). The concept, which found widespread use in the 1970s to 1990s, has since been abandoned, but is still used today by some doctors, contrary to the recommendation.

The inner restlessness associated with the depressive symptoms led to manifestations that were subsumed under agitated depression . In doing so, the patient is driven by a restless urge to move that ran into emptiness, whereby goal-oriented activities are not possible. The patient walks around, cannot sit still and cannot keep his arms and hands still, which is often accompanied by hand rings and nestling. The need for communication is also increased and leads to constant, uniform wailing and complaining . The agitated depression was observed in the elderly comparatively more frequent than in younger and middle-aged.

About 15–40% of all depressive disorders were referred to as “ atypical depression ”. “Atypical” related to the demarcation from endogenous depression and not to the frequency of this symptom of depression. In a German study from 2009, the proportion of atypical depression was 15.3%. Compared to other depressed patients, patients with atypical depression were found to have a higher risk of also suffering from somatic anxiety symptoms, somatic symptoms, guilty thoughts, libido disorders , depersonalization and distrust.

As late / involutional was a depression that occurred the first time after the age of 45 and their prodromal phase was significantly longer than with the depression with earlier onset. Women were (were) more often affected by late-night depression than men. You limit yourself a. from earlier onset depressions due to their longer phase duration, more paranoid and hypochondriac thinking contents, a relative resistance to therapy and an increased risk of suicide.

A distinction should be made between this and the depression of old age , which appears for the first time after the age of 60. The term age depression is misleading, however, since a depressive episode in old age does not differ from that in young years, but depression occurs more frequently in older people than in younger people.

causes

The causes of depressive disorders are complex and only partially understood. There are both inherited and acquired susceptibilities ( predispositions ) to the development of depression. Acquired vulnerabilities can be triggered by biological factors and by life history, social or psychological stress.

Biological influences

genetics

A 2015 study based on family data from 20,198 people in Scotland found a heredity rate of 28 to 44%, with the common environmental influences of a family being only a small influencing factor of seven percent. Twin studies showed that the genetic component is only one factor. Even with identical genetic makeup (identical twins), the twin partner of the depressed patient falls ill in less than half of the cases. In the meantime, differences between affected and unaffected twin partners have also been found in the subsequent ( epigenetic ) change in genetic information, i.e. influences of life history on the control of genetic information. Furthermore, there is a gene-environment interaction between genetic factors and environmental factors . gene environment interaction (GxE). For example, genetic factors can be B. require that a certain person often maneuvers himself into difficult life situations by being willing to take risks. Conversely, it can depend on genetic factors whether a person copes with psychosocial stress or becomes depressed.

A major genetic vulnerability factor for the occurrence of depression is suspected to be a variation in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene 5-HTTLPR. 5-HTTLPR stands for Serotonin (5-HT) Transporter (T) Length (L) Polymorphic (P) Region (R) . The gene is located on chromosome 17q11.1 – q12 . It occurs in different forms in the population (so-called "different length polymorphism" with a so-called "short" and a "long allele "). Carriers of the short allele are more sensitive to psychosocial stress and are said to have up to twice as much risk (disposition) of developing depression as carriers of the long allele. Two meta-analyzes from 2011 confirmed the association between the short allele and the development of post-stress depression. A 2014 meta-analysis found significant data related to depression for a total of seven candidate genes: 5HTTP / SLC6A4, APOE, DRD4, GNB3, HTR1A, MTHFR, and SLC6A3. However, certain deviations that are decisive for the development of depression have not yet been found (as of December 2015) despite an extremely extensive search.

Neurophysiology

After reserpine was first introduced as a medicine in the 1950s, it was observed that some patients showed symptoms of depression after being treated with it. This has been attributed to the lowering of neurotransmitters in the brain. It is certain that the signal transmission, in particular of the monoaminergic neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline, is involved. Other signal systems are also involved, and their mutual influencing is highly complex. Although monaminergic drugs ( antidepressants ) can change depressive symptoms, it remains unclear to what extent these transmitter systems are causally involved in the development of depression. Around a third of patients do not respond or respond only insufficiently to drugs that affect monoaminergic systems.

season

The so-called winter depression is seen as an insufficient adjustment to the annual rhythm and to the seasonal changes in the daily rhythm . Several factors are involved, including the seasonal fluctuations in the formation of vitamin D from sunlight .

Infections

Also chronic infections with pathogens such as streptococci (formerly the virus of Borna disease ) are suspected to trigger depression. The depressive syndromes associated with severe infections or other serious illnesses can, according to the current state of knowledge, be mediated by inflammatory processes and the cytokines that are active in them and can be referred to as " sickness behavior ".

Medicines and drugs

Depressive syndromes can be caused by taking or stopping drugs or psychotropic substances . Distinguishing between substance-induced depression and drug-independent depression can be difficult. The basis of the distinction is a detailed medical history collected by a psychiatrist .

Drugs that can most commonly cause depressive symptoms are anticonvulsants , benzodiazepines (especially after withdrawal), cytostatics , glucocorticoids , interferons , antibiotics , statins , neuroleptics , retinoids , sex hormones, and beta blockers . As drugs with potential depressive effects such. B. diazepam, cimetidine, amphotericin B and barbiturates identified.

Since the 1980s, the use of anabolic steroids in weight training has increased significantly. Since this is considered doping , there is little willingness among athletes to confide in a doctor when they are discontinued. However, stopping the anabolic steroids leads to withdrawal symptoms that are similar to other drug withdrawal. At lower doses, the drop in the body's steroid level is comparable to the drop often seen in older people. According to a cross-sectional study from 2012, depression occurred twice as often in strength athletes with an anabolic steroids dependence than in strength athletes with anabolic steroids but no addiction. The difference was highly significant.

The appearance of a depressive syndrome as withdrawal symptoms after drug use enables researchers to use this effect specifically to investigate depression and its treatment options in animals.

Hormones and culture

Various possible neuroendocrinological causes are discussed regarding the mother's low mood after giving birth (“baby blues”) . With an often cited frequency of around 10 to 15 percent, this so-called postnatal depression is widespread. However, a comparison of 143 studies with data from 40 countries showed that the actual frequencies are in the range of 0 to 60%, which has been associated with large socio-economic differences. The frequency was very low in Singapore, Malta, Malaysia, Austria and Denmark, but very high in Brazil, Guyana, Costa Rica, Italy, Chile, South Africa, Taiwan and South Korea. Symptoms can include depression, frequent crying, symptoms of anxiety, brooding about the future, decreased drive, difficulty sleeping, physical symptoms and thoughts that are tired of life and even suicidality.

pregnancy

According to a large-scale British study, about ten percent of all women are affected by depression during pregnancy. According to another study, it is 13.5 percent in the 32nd week of pregnancy. The symptoms can be extremely different. The main symptom is a depressed mood, whereby this does not have to be sadness in the narrower sense, but is also often described by the patients concerned with terms such as "inner emptiness", "despair" and "indifference". Psychosomatic physical complaints are common. Negative future prospects and a feeling of hopelessness dominate. Self-esteem is low. The depressive symptoms during pregnancy are often influenced by “issues” typical of pregnancy. These could be concerns about the role of mother or the child's health.

Psychological influences

Learned helplessness

According to Seligman's model of depression, depression is caused by feelings of helplessness that follow uncontrollable, aversive events. The causes to which the person ascribes an event are decisive for the controllability of events. According to Seligman, attributing unpleasant events to internal, global and stable factors leads to feelings of helplessness, which in turn lead to depression. Using Seligman's model, the high comorbidity of anxiety disorders can be explained: It is characteristic of all anxiety disorders that people are unable to control their anxiety or can control it very poorly, which leads to experiences of helplessness and, in the course of the disorder, also to hopelessness. According to Seligman, these in turn are the cause of the development of depression.

Cognitions as the cause

At the center of Aaron T. Beck's cognitive theory of depression are cognitive distortions of reality caused by the depressed. According to Beck, the reasons for this are negative cognitive schemes or beliefs that are triggered by negative life experiences. Cognitive schemas are patterns that both contain information and are used to process information and thus have an influence on attention, encoding and evaluation of information. The use of dysfunctional schemata leads to cognitive distortions of reality which, in the case of the depressed person, lead to pessimistic views of themselves, the world and the future (negative triad). Typical cognitive distortions include: a. arbitrary inference, selective abstraction, over-generalization, and exaggeration or understatement. The cognitive distortions retrospectively reinforce the schemes, which leads to a solidification of the schemes. It is unclear, however, whether cognitive misinterpretations, caused by the schemes, represent the cause of the depression or whether cognitive misinterpretations arise through the depression.

Emotional intelligence

The proponents of the concept of emotional intelligence are close to Aaron T. Beck , but go beyond him. Daniel Goleman sees two momentous emotional deficits in depressed teenagers: First, as Beck describes, these show a tendency to interpret perceptions negatively, that is, to increase depression. Second, they also lack solid skills in dealing with interpersonal relationships (parents, peer groups , sexual partners). Children who have depressive tendencies withdraw at a very young age, avoid social contacts and thereby miss out on social learning that they will find difficult to catch up on later. Goleman invokes u. a. based on a study by University of Oregon psychologists at an Oregon high school in the 1990s .

Amplifier loss

According to Lewinsohn's model of depression, which is based on the operant conditioning of behavioral learning theory , depression arises due to an insufficient rate of reinforcement directly related to behavior . According to Lewinsohn, the amount of positive reinforcement depends on the number of reinforcing events, the amount of reinforcers available, and a person's ability to behave in such a way that reinforcement is possible. In the further course, a depression spiral can occur if those affected withdraw socially due to the lack of interest and the loss of amplifiers in turn contributes to a further deterioration in mood. This development must then be counteracted by changes in behavior in the sense of an "anti-depression spiral". The corresponding concept is the basis for behavior activation in treatment.

Stressors and trauma

Persistent stress, such as poverty, can trigger depression. Early trauma can also lead to later depression. Since children's brain maturation is not yet complete, traumatic experiences can promote the development of severe depression in adulthood.

Brown and Harris (1978) reported in their classic study of women from socially disadvantaged areas in London that women without social support are at a particularly high risk of depression. Many other studies since then have supported this finding. People with a small and unsupportive social network are particularly likely to become depressed. At the same time, people who have once become depressed have difficulty maintaining their social network. They speak more slowly and monotonously and make less eye contact, and they are less competent in solving interpersonal problems.

Lack of social recognition

On the basis of extensive empirical studies, the medical sociologist Johannes Siegrist has proposed the model of the gratification crisis (violated social reciprocity) to explain the occurrence of numerous stress diseases (such as cardiovascular diseases, depression).

Bonus crises are considered to be a major psychosocial stress factor. They can occur above all in the professional and working world, but also in private everyday life (e.g. in partner relationships) as a result of an experienced imbalance of mutual give and take. They express themselves in the stressful feeling of having committed or expended on something without this being properly seen or appreciated. Such crises are often associated with a feeling of being used up. In this context, violent negative emotions can arise. This in turn can lead to depression if it persists.

Consequences of parental depression

Depression in a family member affects children of all ages. Parental depression is a risk factor for many problems in children, but depression is particularly common. Many studies have shown the negative consequences of the interaction patterns between depressed mothers and their children. More tension and less playful, mutually rewarding interaction with the children was observed in the mothers. They were less receptive to their child's emotions and less affirmative in dealing with their experiences. In addition, the children were given opportunities to observe depressive behavior and depressive affect. André Green (1983) describes in his concept of the emotionally “dead mother” that depression could be the result of a lack of an emotional response from the parents in important development phases. At the same time he points out the danger of repeating this relationship through silence during a classic psychoanalysis (abstinence).

Suppression of personal interests (inhibition of aggression)

Karl Abraham (1912) observed an inhibition of aggression in depression, which was also recorded by Melanie Klein. It was then initially assumed that this inhibition of aggression could be the cause of the depression. In part, both inside and outside of psychoanalysis, the occurrence of aggression was interpreted as a positive sign. However, Stavros Mentzos assumes that it is not a senseless aggressive discharge that can alleviate the depression, but a solution to an internal conflict that takes into account one's own interests .

Evolutionary theories

The risk of depression is so considerable worldwide that for some an evolutionary adaptation (adaptive function) seems more likely than an isolated disease process. A previously advantageous mode of reaction may be insignificant under today's living conditions; H. the respective predisposition only emerges as an illness or disorder. It is also under discussion whether or not depression still has a function that may not be perceived enough.

Stevens and Price see various psychological disorders as once adaptive social responses based on their frequency, symptoms and social context. In this context, depression is seen as a submissive response to defeat. The observed increase in the burden of disease through depression is therefore associated with our living conditions, especially social factors and competition. Other authors see the essential adaptive aspect in the inhibition of action that is associated with depression, as this can be functional under a wide variety of environmental conditions. This further interpretation is based on the fact that depression has very different triggers, i. H. can occur as a psychological reaction, as a reaction to physical illness and as a light deficiency reaction.

The evolutionary biological theories about the development of depression are scientifically discussed, but have not yet been considered in concepts for the prevention and / or therapy of depression.

treatment

Depression can be successfully treated in the majority of patients. Drug treatment with antidepressants , psychotherapy or a combination of drug and psychotherapeutic treatment, which is increasingly being supplemented and supported by online therapy programs, are possible. Further therapy methods, e.g. B. electroconvulsive therapy, light therapy or waking therapy, sports and exercise therapy complement the treatment options.

The current national treatment guideline evaluates antidepressants as equivalent to psychotherapy for moderately severe to severe depressive periods. For severe depression, a combination of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication is recommended.

There are different psychotherapeutic procedures. Psychotherapy is carried out by doctors with the appropriate additional qualifications (medical psychotherapists), by psychological psychotherapists , by child and adolescent psychotherapists , by alternative practitioners or by alternative practitioners for psychotherapy in accordance with Section 1 of the Heilpraktikergesetz (HeilprG). Often, antidepressants are administered in parallel by the family doctor or psychiatrist.

A combination of psychotherapy and drug treatment can range from doctors (i. D. R. medical specialist in psychiatry or psychosomatic, partly also by general practitioners and other fields) an outpatient basis with psychotherapeutic training, or by a cooperation of physicians and psychotherapist or in psychiatric hospitals or specialized hospitals performed become.

Inpatient treatment

In the case of high levels of suffering and an unsatisfactory response to outpatient therapy and psychotropic drugs - especially in the case of impending suicide - treatment in a psychiatric clinic should be considered. Such treatment offers the patient a daily structure and the possibility of more intensive psychotherapeutic and medical measures, including those that cannot be billed on an outpatient basis and are therefore not possible in particular in the care provided by statutory health insurance doctors . The drug setting, e.g. B. in lithium therapy , a reason for hospitalization. It is also possible to receive intensive treatment in a day clinic during the day, but to spend the night at home. Psychiatric clinics generally have open and closed wards, with patients usually also having an exit on closed wards.

Inpatient depression treatments have become much more common in recent years; as an extreme example, the frequency of hospital treatments for recurrent ( recurrent ) depression increased more than 2.8 times between 2001 and 2010. However, the increase in the number of hospital treatments does not reflect the number of days of treatment, as the average length of stay in hospital decreased at the same time. According to data from the Barmer GEK, depression caused over six percent of all hospital days in 2010 and is therefore by far the top of all diagnoses. The success rates are sobering, however, with more than half of those who have been discharged are still depressed one year after discharge.

psychotherapy

A broad spectrum of psychotherapeutic methods can be used effectively to treat depression (overview of evaluated therapeutic methods in Hautzinger , 2008). These include cognitive behavioral therapy , psychotherapy based on depth psychology and analytical psychotherapy . The psychotherapy and Gestalt therapy can be used for treatment. Newer integrative approaches for the treatment of chronic or recurrent depression are the cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (English Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy , MBCT). For some years now, online therapy programs ( online counseling ) have also been used increasingly (e.g. deprexis24 or iFightDepression.).

The behavioral treatment of depression today is based on cognitive behavioral therapy performed. In the therapy, the thought patterns and behavior patterns that trigger depression should be worked out in order to then change them step by step. In addition, the patient is motivated to be more active in order to reactivate his personal reinforcement mechanisms and to take advantage of the positive effects of greater physical activity on mood.

In depth psychological treatment, the underlying causes of the disease should be made aware of by uncovering and dealing with unconscious psychological conflicts and repressed experiences. The underlying motives, feelings and needs that become perceptible to the patient in the course of the therapy should be able to be integrated into current life.

With regard to the differences in the effectiveness of different psychotherapies, no general recommendations can be given, so that the patient's preferences, main complaints and triggering or currently stressful factors should be taken into account when selecting the therapeutic method. The current national treatment guideline does not contain any recommendations on specific psychotherapy methods either, but refers to evidence tables with different research results.

Medication

The effectiveness of antidepressants depends heavily on the severity of the disease. While the effectiveness is absent or low in mild and moderate severity, it is clear in severe depression. In the most severe forms, up to 30% of treated patients benefit from antidepressants over and above the placeborate. Meta-studies indicate that antidepressant drugs vary widely in effectiveness from patient to patient and, in some cases, a combination of different drugs can have benefits. In the perception of the (professional) public, the effectiveness of antidepressants is more likely to be overestimated, since studies in which the antidepressant performed better than placebo are published much more frequently in specialist journals than those in which the antidepressant was not superior to placebo.

Undesirable side effects have decreased significantly since the introduction of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs, see below) in the 1980s, but should still be taken into account.

Treatment adherence ( compliance ) of the patients in the use of drugs is relatively low, as with other psychiatric medications. Only about half remain in the acute phase, and of this only about half also in the subsequent phase. Various strategies to improve this situation have been scientifically compared. Educational discussions alone were not effective. Comprehensive accompanying measures, e.g. B. also by telephone, were necessary here.

The best-known antidepressants can be divided into three groups (see below). Other antidepressants including phytopharmaceuticals such as St. John's wort can be found in the article Antidepressants . In the case of severe depression without a response to individual antidepressants, augmentations with other antidepressants, neuroleptics , stimulants or phase prophylactics are sometimes prescribed. More recent studies indicate that ketamine can be used for the acute treatment of therapy-resistant and above all suicidal depressed patients due to its rapid therapeutic effect (see below).

Selective reuptake inhibitors

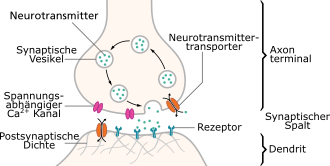

These active ingredients inhibit the reuptake of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine or dopamine in the presynapse . Direct effects on other neurotransmitters are much less pronounced with these selective active ingredients than with tricyclic antidepressants.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are most commonly used in depression today. They work after an intake of two to three weeks. They (largely) selectively inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin at the presynaptic membrane, whereby a “relative” increase in the messenger substance serotonin is achieved during signal transmission. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) have a similar effect , and additionally reduce the reuptake of norepinephrine into the presynapse. Norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitors and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, which inhibit the reuptake of noradrenaline, or noradrenaline and dopamine, have a comparable mechanism of action . SSRI and SNRI (e.g. reboxetine ) differ in their side effect profile.

The pathogenesis of depression, but also of manias and obsessions ( compulsive acts ), is reported by researchers and others. a. associated with serotonergically networked neurons. Therefore, SSRIs and SNRIs are also used against (comorbid) obsessive-compulsive and anxiety states, often with success. Since serotonin also plays a role in other neurally mediated processes in the whole body, such as digestion and coagulation of the blood, the typical side effects result from interaction with other neurally controlled processes.

SSRIs have been in use since 1986; since 1990 they have been the most prescribed class of antidepressants. They are very popular because of their profile with fewer side effects, especially with regard to the circulation and heart. However, relatively common side effects are sexual dysfunction and / or anorgasmia . Although these almost always regress completely a few weeks after stopping or changing the drug, they can lead to additional (relationship) problems.

Tricyclic antidepressants

The tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. trimipramine , amitriptyline ) were the most frequently prescribed until the advent of serotonin reuptake inhibitors. It is a relatively large group of substances that differ markedly in their effects and, above all, in their possible combinations with other classes of antidepressants and therefore require in-depth knowledge. The main disadvantage is their pronounced side effects (e.g. dry mouth, constipation, fatigue, muscle tremors and drop in blood pressure), although there are better tolerated exceptions (e.g. amoxapine , maprotiline ). Caution is therefore advised in the elderly and in people weakened by previous illnesses. In addition, some tricyclics often have a drive-increasing effect at first and only then do they improve mood, which can lead to a higher risk of suicide in the first few weeks of use. In the USA, however, SSRIs must also carry a warning notice.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

MAO inhibitors work by blocking the monoamine oxidase - enzymes . These enzymes break down monoamines such as serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine - i.e. neurotransmitters (messenger substances between the nerve cells in the brain) - and thereby reduce their availability for signal transmission in the brain. The MAO inhibitors inhibit these enzymes, which increases the concentration of monoamines and thus the neurotransmitters and increases the signal transmission between the nerve cells.

MAOIs are divided into selective or non-selective and reversible or irreversible. Selective inhibitors of MAO-A (e.g. moclobemide , reversible) only inhibit type A of monoamine oxidase and show an antidepressant effect. They are generally well tolerated, among other things with significantly fewer disorders of digestive and sexual functions than with SSRIs. Selectively MAO-B-inhibiting agents (e.g. selegiline , irreversible) are primarily used in Parkinson's treatment. Non-selective MAO inhibitors (e.g. tranylcypromine , irreversible) inhibit MAO-A and MAO-B and are highly effective in the treatment of (therapy-resistant) depression and anxiety disorders. Irreversible MAO inhibitors bind the MAO-A or MAO-B permanently. In order to reverse the effect, the affected enzyme must first be regenerated by the body, which can take weeks. Reversibility means that the drug binds only weakly to the MAO and releases MAO-A or MAO-B again intact at the latest when the drug breaks down.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors are considered to be very effective. However, patients taking non-selective, irreversible MAOIs must follow a strict, low-tyramine diet. In connection with the consumption of certain foods, such as B. cheese and nuts, the use of non-selective irreversible MAOIs can lead to a dangerous rise in blood pressure.

Ketamine

In depressive emergencies ( suicide risk ), several studies have confirmed a rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine , an antagonist of the glutamate - NMDA receptor complex . Study results showed a significant improvement over a period of up to seven days after a single dose. There are recommendations for low-dose prescriptions, which, in contrast to use as an anesthetic or dissociative, show hardly any side effects. The pharmacological effect in depression is triggered by (2 R , 6 R ) -hydroxynorketamine , a metabolite of ketamine. In contrast to ketamine and norketamine, hydroxynorketamine is inactive as an anesthetic and dissociative and does not produce intoxication . In March 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved a nasal spray containing the ketamine derivative esketamine for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression. Since December 2019, the drug ( Spravato ) has also been approved in the European Union for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression.

Combination therapy

A combination of antidepressants may be useful for patients whose depression does not improve with pharmacotherapy and who are willing to accept possible side effects. However, the combination is only recommended for very specific active ingredients. This applies to the combination of mianserin or mirtazapine on the one hand with an SSRI or a tricyclic antidepressant on the other.

light therapy

The current treatment guideline recommends light therapy for depression that follows a seasonal pattern. About 60-90% of patients benefited from light therapy after about two to three weeks. Previous results showed that light therapy was also effective for non-seasonal depression. In order to ensure an effect, the patients should look into a special light source for at least 30 minutes every day, which emits white full-spectrum light of at least 10,000 lux. The recommended starting dose is 10,000 lux for 30-40 minutes, at least two to four weeks each morning, as soon as possible after awakening. According to a systematic review published by the Cochrane Collaboration in 2015, no conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of light therapy for the prevention (prevention) of new depressive episodes.

Such seasonal depressions (as a subgroup of all seasonally occurring disorders, summarized in English Seasonal Affective Disorders - SAD ) are correlated with a circadian rhythm ( day length dependence) in humans. The organisms on earth have adapted to changes in the length of the day and have developed corresponding circadian internal clocks in order to set activities, reproduction and metabolic processes at biologically advantageous times. It is not yet clear whether a disturbed circadian system is causing the depression or whether the depression is the cause of the changed circadian system or whether other combinations are responsible. At least influences on this circadian system could also lead to therapies against seasonal depression. For example, sleep deprivation or lithium can influence such circadian systems and also treat depression.

Stimulation method

Particularly in the case of severe depression that has been resistant to drug and psychotherapeutic treatment for a long time, more recently stimulation methods have been used again, the mechanisms of which, however, are still largely unclear.

The most common procedure used in this regard is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). During epilepsy treatment, it was noticed that patients who were simultaneously suffering from depression also experienced an improvement in mood after an epileptic seizure. Electroconvulsive therapy is performed under anesthesia and is a possible alternative if drugs and psychotherapy do not work in severe depression. Significant short-term effects have been demonstrated. In detail, unexplained effects in severe depression are also associated with a decrease in the tendency to commit suicide and a decrease in suicides. There is evidence of influencing neuroendocrinological mechanisms.

Other stimulation methods such as magnetic convulsion therapy (a convulsion is induced by means of strong magnetic fields), vagus nerve stimulation (a pacemaker sends electrical impulses to the vagus nerve ; approved as a therapy method in the USA), and transcranial magnetic stimulation (brain stimulation by an external magnetic field) are in the experimental stage of the head), the transcranial direct current application (tDCS) (weak ectic brain stimulation through the skull bone). Evidence of the effectiveness of these procedures is not yet available (as of December 2015).

Move

One form of supportive therapeutic measures is sports therapy . If sport takes place in a social context, it makes it easier for people to resume contact. Another effect of physical activity is increased self-esteem and the release of endorphins . The positive effects of jogging on depression have been empirically proven by studies; In 1976 the first book on the subject was published under the title The Joy of Running .

Weight training, for example, was shown to be effective in a study for old patients (70+ years). After 10 weeks of guided training, there was a decrease in depressive symptoms compared to a control group (who had not trained, but had read with guidance). The effect was still detectable for some of the test persons two years after the end of the guided training.

A large number of methodologically robust studies on the benefits of exercise and exercise in depression exist. These show, for example, that exercise (under supervision, at home) is just as effective against depression as drug therapy (sertraline) or placebo medication. A meta study from 2013 assessed the effect more cautiously, but underlines the preventive effect, since "moderate aerobic exercise of at least 150 minutes per week [...] is associated with a noticeably lower risk of developing depression". If the goal is not prevention, but treatment of depression, according to a meta-study from 2019, three 45-minute exercise every week is necessary for a month to improve mood.

nutrition

Scientific studies suggest the particular importance of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) for lightening the mood and having a beneficial effect on reducing depression. EPA is a polyunsaturated fatty acid from the class of omega-3 fatty acids .

The mechanism of action of the omega-3 fatty acid has not yet been clarified, but an interaction of the fatty acid with the neurotransmitter serotonin is suspected: A deficiency in serotonin is often accompanied by a deficiency in omega-3 fatty acids; conversely, the administration of fatty acids seems to increase of serotonin levels.

The alternative medicine " orthomolecular medicine " also tried on the amino acids tyrosine , phenylalanine and tryptophan or 5-HTP to influence depression cheap (oxitriptan). Their representatives postulate that these amino acids are converted in the body into norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin. Increasing the levels of these neurotransmitters in the brain can be mood lift. However, there is a lack of scientific evidence for a positive effect of tryptophosphorus information (e.g. in the form of dietary supplements ).

It is certainly not wrong to ensure a balanced and healthy diet even after the depressive symptoms have subsided. A constant blood sugar level through regular meals plays a role, just as a moderate use of luxury foods such as coffee, nicotine and alcohol can help to remain mentally stable.

Sleep hygiene

Depression affects the quality of sleep (see above). Conversely, an improvement in sleep ( sleep hygiene ) can have a positive effect on depression. This includes regular times to go to bed, avoiding monitor light in the evening, adapted lighting, darkening the bedrooms and other measures.

sleep deprivation

Partial (partial) sleep deprivation in the second half of the night or even complete sleep deprivation in one night is the only antidepressant therapy with positive effects in around 60% of patients on the same day. However, the antidepressant effect is rarely sustained. Most of the time, the depressive symptoms return after the next night of rest. However, up to 15% of patients in clinical trials showed sustained improvement after total sleep deprivation. The national treatment guideline recommends that watch therapy should be considered as a supplementary therapy element in certain cases due to its relatively easy implementation, non-invasiveness, cost-effectiveness and rapid effect.

meditation

A systematic review from 2015 showed positive effects of meditation techniques . Similar work from 2014 described small to moderate effects, and it was also found that there was no evidence that meditation was more effective than other targeted activities, such as exercise or progressive muscle relaxation . The effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for the prevention of relapse of depression has been adequately proven by current meta-analyzes and was therefore included as a therapy recommendation in the S3 guideline / NVL Unipolar Depression . Mindfulness exercises are used to identify the activation of thoughts, feelings and body sensations that promote depression in good time, so that those affected can consciously turn to helpful measures to prevent relapse.

Obsolete treatment approaches

Based on the facial feedback hypothesis , the assumption arose in 2012 that a reduction in the vertical skin folds between the eyebrows ( glabella region) through botox injection would be effective against depression. However, this could not be scientifically confirmed.

forecast

Depressive underlying illness

Depressive episodes often resolve over time, regardless of whether they are treated or not. Outpatients on a waiting list show a 10–15% reduction in symptoms within a few months, with around 20% no longer meeting the criteria for a depressive disorder. The median duration of an episode was estimated to be 23 weeks, with the first three months having the highest recovery rate.

Most treated patients report residual symptoms despite apparently successful treatment. Residual symptoms that occur when the disease subsides temporarily or permanently have a strong prognostic value. There seems to be a connection between these residual symptoms and signs of recurrence . It is therefore recommended for treating physicians that the concept of recovery should also include psychological well-being.

The simultaneous occurrence of a personality disorder and depression has a negative impact on the treatment outcome. Personality disorder is approximately twice as likely to be associated with poor treatment for depression as it is for someone without a personality disorder.

Risk of suicide

It is estimated that around half of the people who have a suicide commit, have suffered from depression. In 2010 around 7,000 people with depression committed suicide in Germany. Depression is therefore a very serious disorder that requires extensive therapy.

Concomitant health risks

As a result of the frequently unhealthy lifestyle, patients with depression suffer more from the consequences of smoking, lack of exercise, nutritional deficiencies and obesity. There is also evidence that irregular medication intake also poses a cardiovascular risk, making it more susceptible to strokes. This is especially true for middle-aged women.

Depression itself is a risk factor for developing coronary artery disease . Possible causes for this are the influences of depression on the control of hormone regulation in the adrenal gland , influences on the immune system and hemostasis , but also an unhealthy lifestyle or side effects of antidepressants. In a patient with coronary artery disease, depression increases the risk of myocardial infarction three to four times. Furthermore, the risk of a fatal heart attack is increased. Studies show that in spite of this, the depression often remains untreated in patients with myocardial infarction. Treatment of depression would have beneficial effects on the patient's chances of recovery.

Social dimension

Economic relevance

In 2015, the healthcare sector incurred costs of 8.7 billion euros (5.8 billion for women and 2.9 billion for men). Estimates from 2008 show costs in Germany totaling between 15.5 billion euros and 22.0 billion euros. These costs are composed of the direct costs in the health system and the indirect costs such as “loss of productivity potential due to morbidity and mortality”. In 2018, only 12.1% of those affected who were in outpatient treatment were unable to work due to illness. On average, women and men are equally affected. People with a depressive episode tend to be absent in the long term (more than seven calendar weeks), which means that the average case duration is 12.9 days per case and thus sometimes exceeds the diagnoses of malignant neoplasms (cancer) and cardiovascular diseases.

Stigma

When it comes to the stigmatization of depressed people, both cross-cultural patterns and cultural differences have been found in empirical studies. For example, when comparing Australia and Japan, the stigma in depression was generally lower than in schizophrenia. The presence of suicidal ideation did not have a large additional impact. In Australia, however, almost a quarter of respondents believed that a person with depression could "get it back" if they wanted to. The Japanese numbers were far higher than Australia's. Almost half of respondents in Japan thought that a person with depression "can cope with it". Another finding was that 17% of Australians and 27% of Japanese said they would not tell anyone if they had depression and 30% of Australians and 58% of Japanese said they would not choose someone who had one Has depression.

State measures

To improve the framework conditions, the health system has initiated various model projects since the 1990s. The Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs has made “protecting health in the event of work-related psychological stress” one of the main goals of the Joint German Occupational Safety and Health Strategy from 2013 onwards. In 2012, the Federal Ministry of Health (BMG) commissioned the Deprexis research project on the possibilities of online therapy, which could possibly represent a way to bridge gaps in supply and long waiting times for a therapy place.

The treatment of depressive illnesses was established as a health goal in 2006 . The sub-goals include education, prevention and rehabilitation.

Statutory health insurance companies are obliged to support non-profit organizations in the field of self-help; in 2011 this support totaled around half a million euros.

Private organizations

Associations, non-profit GmbH (gGmbH) and foundations deal with the topic of depression. The offers start at the following points:

- Education, advocacy and networking - this is what the German Alliance against Depression e. V. or the German Depression League . In 2011, these organizations, together with the German Depression Aid Foundation, introduced the Depression Patient Congress. There are patient congresses for a wide variety of topics, including dementia or cancer - the goals are usually information and exchange between patients, scientists and stakeholders.

- Individual advice - will u. a. offered by local alliances against depression or self-help organizations . Affected people and their relatives can get information from these organizations, exchange ideas with people in similar situations or ask for help in acute situations, for example with telephone counseling or the SeeleFon .

- Self-help - Self-help groups are not a substitute for therapy , but they can provide accompanying help. Self-help groups can serve as lifelong companions and places of retreat. Some groups do not expect advance notice, so that those affected can spontaneously seek help in acute phases of depression. Self-help groups in the outpatient sector have established themselves as a low-threshold offer and make an important contribution. In hospitals and rehabilitation clinics , they help those affected to strengthen their personal responsibility and gain self-confidence .

reception

- The dark gene , documentary (2015)

See also

- E-Mental Health

- NotJustSad , a hashtag used by those affected to report on their depression on Twitter

- Online advice

- Acedia

- Dysphoria

literature

Introductions

- Michael Bauer, Anne Berghöfer, Mazda Adli (eds.): Acute and therapy-resistant depression. Pharmacotherapy - Psychotherapy - Innovations 2nd, completely revised and expanded edition. Springer, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-540-40617-4 .

- Tom Bschor (ed.): Treatment manual therapy-resistant depression: pharmacotherapy - somatic therapy methods - psychotherapy. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-019465-6 .

- Martin Hautzinger : Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. 7th edition. Beltz, Weinheim 2013, ISBN 978-3-621-28075-4 .

- Piet C. Kuiper : Soul Eclipse. A psychiatrist's depression . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-596-12764-5 (Dutch: Ver heen . Translated by Marlis Menges).

- Rainer Tölle , Klaus Windgassen: Psychiatry: Including psychotherapy. 16th edition. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-20416-6 .

Psychoanalytic writings

- Joachim Küchenhoff : Depression (= analysis of the psyche and psychotherapy . Volume 16 ). Psychosozial-Verlag, Giessen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8379-2705-4 ( table of contents and reading sample [PDF; accessed on August 21, 2018]).

Advisory literature

- Barbara Bojack: Depression in Old Age: A Guide for Relatives. Psychiatrie-Verlag, Bonn 2003, ISBN 3-88414-359-X .

- Recognize and treat depression. Information brochure for patients and relatives, published by the Federal Association for Health Information and Consumer Protection - Info Gesundheit. medcom, Bonn 2013, ISBN 978-3-931281-50-2 (free publication, can be ordered online)

- Pia Fuhrmann, Alexander von Gontard: Depression and Anxiety in Small and Preschool Children: A Guide for Parents and Educators. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8017-2627-0 .

- Gunter Groen, Wolfgang Ihle, Maria Elisabeth Ahle, Franz Petermann : Counselor sadness, withdrawal, depression: information for those affected, parents, teachers and educators. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-8017-2382-8 .

- Ulrich Hegerl, Svenja Niescken: Overcoming depression: Rediscovering the joy of life. 3. Edition. TRIAS, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-8304-6781-6 .

- Ruedi Josuran, Verena Hoehne, Daniel Hell: Right in the middle and not there: Learning to live with depression. Ullstein-Taschenbuch, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-548-36428-4 .

- Anke Rohde: Postnatal Depression and Other Psychological Problems: A Guide for Affected Women and Relatives. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-17-022116-1 .

- Larissa Wolkenstein, Martin Hautzinger : Counselor Chronic Depression. Information for those affected and their relatives. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8444-2516-1 .

S3 guidelines

- National Unipolar Depression Care Guideline . Program for National Supply Guidelines (NVL), as of November 16, 2015 awmf.org .

- Treatment of Depressive Disorder in Children and Adolescents . German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP), as of July 1, 2013, valid until June 30, 2018 awmf.org

- Psychosocial therapies for severe mental illness . German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology (DGPPN), as of October 25, 2012, valid until October 25, 2017, awmf.org

Web links

- Depression - editorially supervised collection of links in the joint project Psychlinker of the Leibniz Center for Psychological Information and Documentation and the Saarland University and State Library

- What is Depression? Information portal for neurologists and psychiatrists online , published by several German and Swiss professional associations and specialist societies.

- Education helps identify depression and prevent suicides . Further information in the Knowledge sectionon the website of the German Depression Aid Foundation .

- Guideline synopsis for a DMP depression . Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care , IQWiG reports , No. 502, April 4, 2017.

- Heike Le Ker: Body and psyche: How inflammation causes depression . In: Spiegel Online , April 17, 2015.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden | depressed | Spelling, meaning, definition, synonyms, origin. Retrieved July 23, 2018 .

- ↑ E. Bromet, LH Andrade, I. Hwang, NA Sampson, J. Alonso, G. de Girolamo, R. de Graaf, K. Demyttenaere, C. Hu, N. Iwata, AN Karam, J. Kaur, S. Kostyuchenko, JP Lépine, D. Levinson, H. Matschinger, ME Mora, MO Browne, J. Posada-Villa, MC Viana, DR Williams, RC Kessler: Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. In: BMC Medicine. Volume 9, 2011, p. 90, doi: 10.1186 / 1741-7015-9-90 . PMID 21791035 , PMC 3163615 (free full text) (review).

- ^ E. Jane Costello, A. Erkanli, A. Angold: Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? In: Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. Volume 47, Number 12, December 2006, pp. 1263-1271, doi: 10.1111 / j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x . PMID 17176381 (Review).

- ↑ a b E. M. Bitzer, TG Grobe u. a .: Barmer GEK Report Krankenhaus 2011. (= series of publications on health analysis. Volume 9). Barmer GEK, 2011, ISBN 978-3-537-44109-6 .

- ↑ DRV: Statistics of pension access. German Federal Pension Insurance (Ed.), Federal Statistical Office, 2012. www.gbe-bund.de

- ↑ AOK: Inability to work for employed AOK members. Federal Statistical Office, 2013. www.gbe-bund.de

- ↑ D. Richter, K. Berger u. a .: Are mental disorders increasing? A systematic review of the literature. In: Psychiatr Prax. 35, 2008, pp. 321-330.

- ↑ a b A. V. Horwitz, JC Wakefield: The Loss of Sadness. How Psychiatry Transformed Normal Sorrow Into Depressive Disorder. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2007.

- ↑ H. Spiessl, F. Jacobi: Are mental disorders increasing? In: Psychiatr Prax. 35, 2008, pp. 318-320.

- ↑ JM Twenge, B. Gentile et al. a .: Birth cohort increases in psychopathology among young Americans, 1938-2007: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the MMPI. In: Clin Psychol Rev. 30, 2010, pp. 145-154.

- ↑ a b B. H. Hidaka: Depression as a disease of modernity: explanations for increasing prevalence. In: Journal of affective disorders. Volume 140, number 3, November 2012, pp. 205-214, doi: 10.1016 / j.jad.2011.12.036 . PMID 22244375 , PMC 3330161 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ DAK: DAK health report 2011. German salaried health insurance, Hamburg 2011.

- ↑ Data from TK Depression Atlas 2014; see Florian Staeck: More and more days off due to depression. Doctors newspaper online, January 28, 2015.

- ↑ Depression: Older students in particular are at risk. Ärzteblatt, February 22, 2018.

- ↑ a b c d DGPPN u. a .: National Health Care Guideline - Unipolar Depression . Springer Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-13103-5 . ( Long version ( Memento from March 31, 2017 in the Internet Archive )).

- ^ A b Rainer Tölle : Psychiatry. 2012, ISBN 978-3-662-22357-4 , pp. 238-239, online .

- ↑ Psychology: Depression - the disease with the lack of meaning . Welt online, accessed February 19, 2012.

- ↑ Birgit Borsutzky: Painfully loud: When noises become torture . Report on the Odysso program on swr.de.

- ↑ DA Bangasser, RJ Valentino: Sex differences in stress-related psychiatric disorders: neurobiological perspectives. In: Frontiers in neuroendocrinology. Volume 35, number 3, August 2014, pp. 303-319, doi: 10.1016 / j.yfrne.2014.03.008 . PMID 24726661 , PMC 4087049 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Christiane Nevermann, Hannelore Reicher: Depression in childhood and adolescence . C. H. Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-47566-3 .

- ↑ G. Groen, F. Petermann: Depressive disorders. In F. Petermann (ed.): Textbook of clinical child psychology. (6th, fully revised edition, pp. 427–443) Hogrefe, Göttingen 2008.

- ↑ Annemarie Dührssen : Psychogenic diseases in children and adolescents , 10th edition, Göttingen 1974, page 81 f. and page 216

- ↑ a b DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPM, DGPs, DGRW (ed.): S3 Guideline / National Care Guideline Unipolar Depression - Long Version (Long Version Version 5) . 2009, p. 67 and 73 ( online ).

- ↑ MayoClinic.com - Vitamin B12 and Depression

- ↑ Innovations-Report - Experts study viruses as triggers of mental illness

- ↑ M. Ledochowski, B. Sperner-Unterweger, B. Widner, D. Fuchs: Fructose malabsorption is associated with early signs of mental depression . In: Eur. J. Med. Res. Band 3 , no. 6 , 1998, pp. 295-298 , PMID 9620891 .

- ↑ Anna M. Ehret: DSM-IV and DSM-5: What has actually changed? (Review) . In: behavior therapy . tape 23 , no. 4 , 2013, p. 258–266 , doi : 10.1159 / 000356537 ( karger.com [PDF] For major depression see p. 262).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j S3 guideline / National Care Guideline Unipolar Depression, 2015, valid until 2020, last revision 03/2017. (PDF) DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, accessed on August 27, 2017 .

- ↑ H.-P. Haack: frequency of larvae depression. In: The Medical World. (43 | 85), 1985, pp. 1370-1373.

- ↑ H.-P. Haack, H. Kick: How often is headache an expression of endogenous depression? In: German Medical Weekly . 111 (16), 05/1986, pp. 621-624.

- ↑ T. Bschor: masked depression: The Rise and Fall of a diagnosis. (PDF) In: Psychiatric Practice. 29 2002, pp. 207-210; accessed on December 16, 2015.

- ↑ M. Riedel et al. a .: Frequency and clinical characteristics of atypical depressive symptoms. ( Memento of March 14, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) 2009.

- ↑ AM Fernandez-Pujals, MJ Adams, P. Thomson, AG McKechanie, DH Blackwood, BH Smith, AF Dominiczak, AD Morris, K. Matthews, A. Campbell, P. Linksted, CS Haley, IJ Deary, DJ Porteous, DJ MacIntyre, AM McIntosh: Epidemiology and Heritability of Major Depressive Disorder, Stratified by Age of Onset, Sex, and Illness Course in Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study (GS: SFHS). In: PloS one. Volume 10, number 11, 2015, p. E0142197, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0142197 . PMID 26571028 , PMC 4646689 (free full text).

- ↑ EM Byrne, T. Carrillo-Roa, AK Henders, L. Bowdler, AF McRae, AC Heath, NG Martin, GW Montgomery, L. Krause, NR Wray: Monozygotic twins affected with major depressive disorder have greater variance in methylation than their unaffected co-twin. In: Translational psychiatry. Volume 3, 2013, p. E269, doi: 10.1038 / tp.2013.45 . PMID 23756378 , PMC 3693404 (free full text).

- ↑ KS Kendler, LM Karkowski, CA Prescott: Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. In: The American journal of psychiatry. Volume 156, Number 6, June 1999, pp. 837-841, doi: 10.1176 / ajp.156.6.837 . PMID 10360120 .

- ↑ K. Karg, M. Burmeister, K. Shedden, S. Sen: The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. In: Archives of general psychiatry. Volume 68, number 5, May 2011, pp. 444–454, doi: 10.1001 / archgenpsychiatry.2010.189 . PMID 21199959 , PMC 3740203 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ A. Daniele R. Divella, A. Paradiso, V. Mattioli, F. Romito, F. Giotta, P. Casamassima, M. Quaranta: serotonin transporter polymorphism in major depressive disorder (MDD), psychiatric disorders, and in MDD in response to stressful life events: causes and treatment with antidepressant. In: in vivo. Volume 25, number 6, 2011 Nov-Dec, pp. 895-901, PMID 22021682 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ J. Flint, KS Kendler: The genetics of major depression. In: Neuron. Volume 81, number 3, February 2014, pp. 484–503, doi: 10.1016 / j.neuron.2014.01.027 . PMID 24507187 , PMC 3919201 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ S. Ripke et al. a .: A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. In: Molecular psychiatry. Volume 18, number 4, April 2013, pp. 497-511, doi: 10.1038 / mp.2012.21 . PMID 22472876 , PMC 3837431 (free full text) (review).

- ↑ Hans Bangen: History of the drug therapy of schizophrenia. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4 . P. 94

- ↑ Monika Pritzel, Matthias Brand, J. Markowitsch: Brain and behavior: A basic course in physiological psychology . Springer, 2003, ISBN 978-3-8274-2340-5 , pp. 513 .

- ↑ Jeffrey R. Lacasse, Jonathan Leo: Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature . In: PLoS Med 2 (12): e392 . November 8, 2005.

- ↑ M. Hamon, P. Blier: Monoamine neurocircuitry in depression and strategies for new treatments. In: Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. Volume 45, August 2013, pp. 54-63, doi: 10.1016 / j.pnpbp.2013.04.009 . PMID 23602950 (Review).

- ↑ AE Stewart, KA Roecklein, S. Tanner, MG Kimlin: Possible contributions of skin pigmentation and vitamin D in a polyfactorial model of seasonal affective disorder. In: Medical hypotheses. Volume 83, number 5, November 2014, pp. 517-525, doi: 10.1016 / j.mehy.2014.09.010 . PMID 25270233 (Review).

- ↑ Background - Medicine: When harmless pathogens make you mentally ill . ( Memento from May 12, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Wissenschaft.de, May 9, 2007.

- ^ Robert Dantzer, Jason C. O'Connor, Gregory G. Freund, Rodney W. Johnson, Keith W. Kelley: From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain . In: Nature Reviews Neuroscience . tape 9 , no. 1 , January 2008, p. 46-56 , doi : 10.1038 / nrn2297 .

- ↑ Frank Block, Christian Prüter (ed.): Drug-induced neurological and psychiatric disorders. Springer Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-540-28590-3 .

- ↑ Monika Keller: Depression. In: Eberhard Aulbert, Friedemann Nauck, Lukas Radbruch (eds.): Textbook of palliative medicine. Schattauer, Stuttgart (1997) 3rd, updated edition 2012, ISBN 978-3-7945-2666-6 , pp. 1077-1095; here: p. 1083.

- ^ EJ Ip, DH Lu, MJ Barnett, MJ Tenerowicz, JC Vo, PJ Perry: Psychological and physical impact of anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence. In: Pharmacotherapy. Volume 32, number 10, October 2012, pp. 910-919, doi: 10.1002 / j.1875-9114.2012.01123 . PMID 23033230 .

- ↑ T. Renoir, TY Pang, L. Lanfumey: Drug withdrawal-induced depression: serotonergic and plasticity changes in animal models. In: Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. Volume 36, number 1, January 2012, pp. 696-726, doi: 10.1016 / j.neubiorev.2011.10.003 . PMID 22037449 (Review).

- ↑ A. Skalkidou, C. Hellgren, E. Comasco, p Sylvén, I. Sundström Poromaa: Biological aspects of postpartum depression. In: Women's health. Volume 8, number 6, November 2012, pp. 659-672, doi: 10.2217 / whe.12.55 . PMID 23181531 (Review).

- ↑ U. Halbreich, S. Karkun: Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. In: Journal of affective disorders. Volume 91, number 2-3, April 2006, pp. 97-111, doi: 10.1016 / j.jad.2005.12.051 . PMID 16466664 (Review).

- ↑ Werner Rath, Klaus Friese: Diseases in pregnancy. Thieme, 2005, p. 347.

- ↑ Jonathan Evans: Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. In: BMJ. 323, 2001, pp. 257–260 (August 4, 2001)