Task forces of the security police and the SD

The Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD (abbreviated EGr ) were ideologically trained and partly mobile, partly stationary "special units" that Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler commissioned Adolf Hitler for mass murders during the attack on Poland in 1939, during the Balkan campaign in 1941 and above all during the war against the Soviet Union 1941-1945 set up and deployed. The task forces served the step-by-step implementation of the National Socialist racial ideology and genocide policy and, along with other groups of perpetrators, were significantly involved in the Holocaust (Shoah) and the Porajmos , the genocide of the European Roma during the National Socialist era. They were divided into 16 so-called Einsatzkommandos and comprised a total of up to 3,000 men.

In Poland the Einsatzgruppen from September 1939 on Hitler's orders and with the knowledge of the murdered Wehrmacht at least 60,000 members of state elites, including about 7,000 Jews, as well as thousands mentally ill. From 1941 onwards, in cooperation with the Wehrmacht, they murdered Jews , Roma (then called " Gypsies "), communists , actual and alleged partisans , " anti-social " as well as the mentally ill , mentally or physically handicapped in the sovereign territory of the Soviet Union and in the Balkans . The main perpetrators were members of the Security Police (Sipo) - consisting of the Secret State Police (Gestapo) and Criminal Police (Kripo) -, the Security Service (SD), the Ordnungspolizei (Orpo) and the Waffen SS .

Task Force Groups before the Second World War

Since his appointment as "Reichsführer SS" (1929), Himmler had begun to develop the SS , a sub-organization of the NSDAP , into an armed, paramilitary elite force. To this end, Reinhard Heydrich had founded the "Security Service of the Reichsführer SS" (SD) since 1931, which was given a central, nationwide organization in the spring of 1933. After the Röhm putsch in 1934, Himmler also became chief of the political police, and in 1936 of the other German police. With Heydrich, he sought a close connection between the SS, SD and police. For special tasks before almost every area expansion, Himmler had special "task forces", also known as "special" or "special units", set up from the ranks of the organizations subordinate to him. SS-Obergruppenführer Werner Best was responsible for building it up until 1940 . Immediately after the German troops marched into a new area, these groups were supposed to take over the “fight against the enemies of the Reich”, primarily through investigations and arrests. By September 1939 they had no murder orders, but they had considerable room for maneuver in the implementation of their orders. Their list marked the transition to a systematic persecution of all actual and supposed opponents of the Nazi regime in these areas.

When Austria was " annexed " to the German Reich , the Task Force Austria , founded in 1938, was deployed. It consisted of members of the SD and was led by SS-Standartenführer Franz Six . His task was the arrest of opponents of the "Anschluss" with prepared wanted lists.

When the Sudetenland was incorporated in September 1938, the term Einsatzgruppe appeared for the first time in Nazi administrative language: It referred to the Einsatzgruppe Dresden, which consisted of five Einsatzkommandos under SS-Standartenführer Heinz Jost , and the Einsatzgruppe Wien with two Einsatzkommandos under SS-Standartenführer Walter Stahlecker . Both were established and dispatched by the Gestapo, which claimed jurisdiction because the Sudeten Germans were defined as citizens of the Reich. The commandos were supposed to carry out all Gestapo tasks in their area relatively independently in a "special operation", i.e. arrest "anti-Reich" persons using a " special wanted list " and reports from Sudeten Germans, confiscate their documents, close their facilities, occupy Czechoslovak police stations and post office and monitor telephone traffic. They were strictly forbidden from mistreating and killing arrested persons and harassing bystanders because it seemed necessary. They arrested around 10,000 people and, together with Sudeten German organizations, drove numerous Czechs from their residential areas.

For the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia (the "rest of Czech Republic " ) in March 1939, Einsatzgruppe I Prague and Einsatzgruppe II Brno were set up. They were in turn divided into several Einsatzkommandos: Budweis , Prague , Kolin , Pardubitz , Brünn , Olmütz , Zlin , the Einsatzkommando 9 Mies under SS-Hauptsturmführer Gustav vom Felde and the Sonderkommando Pilsen . They also arrested about 10,000 people.

Poland

Setup and task

On April 11, 1939, Hitler gave the Wehrmacht orders to prepare militarily for the attack on Poland ("White Fall"). This made it possible for Himmler and Heydrich to use the SS, SD and security police outside of German territories for a racist population policy (known as "ethnic land consolidation"). To this end, a conference led by Heydrich on July 5, 1939, decided to set up five Einsatzgruppen. They were assigned to the five armies of the Wehrmacht intended for the attack on Poland and subordinated to the Army High Command (OKH).

The total of 16 task forces consisted of 120 to 150 men each with a total strength of 2700 or 3000 men.

Werner Best organized their construction and equipment. Thereupon were set up:

- Task Force I under SS-Standartenführer Bruno Linienbach . It consisted of four task forces under:

- (1) SS-Sturmbannführer Ludwig Hahn ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer Bruno Müller ,

- (3) SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Hasselberg ,

- (4) SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Brunner .

- Task Force II under SS-Standartenführer Emanuel Schäfer consisted of two task forces under:

- (1) SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Sens ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer Karl-Heinz Rux .

- Task Force III under SS-Obersturmbannführer and Government Councilor Hans Fischer consisted of two task forces under:

- (1) SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Scharpwinkel ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Liphardt .

- Task Force IV under SS Brigadführer Lothar Beutel (from October 23, 1939 SS Obersturmbannführer Josef Meisinger ) consisted of two task forces under:

- (1) SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Helmut Bischoff ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer and Councilor Walter Hammer

- Task Force V under SS Brigadefuhrer Ernst Damzog consisted of three task forces under:

- (1) SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Heinz Gräfe ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer and Councilor Robert Schefe ,

- (3) SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Walter Albath .

According to the sources, the assignment of these groups has not yet been fully clarified. According to the “guidelines” of the OKH dated July 5, 1939, agreed with the SS, they were to “fight all elements hostile to the Reich and German in enemy territory behind the fighting troops”. This deliberately vague mandate allowed the task force leaders to largely determine their own approach and to select their victims themselves. According to post-war statements of involved witnesses declared Himmler and Heydrich selected task force leaders in mid-August 1939 them was "as part of the fight against resistance movements and groups anything goes ... so both shootings and arrests." They had the Polish "intelligentsia" ( inteligencja ) not specifically mentioned. However, from May 1939 onwards, the Wehrmacht and SS expected resistance to the Germans, especially from members of the elite, intelligentsia and Jews of Poland. On August 22, 1939, Hitler explained to the Wehrmacht generals that he had given the order "for the time being only in the East" to send deaths to deaths "mercilessly and mercilessly man, woman and child of Polish origin and language". The historian Jochen Böhler interprets this as an extensive execution order to the Einsatzgruppen, parallel to Hitler's order to conquer the Wehrmacht.

On August 29, Heydrich and Best agreed with the General Quartermaster of OKH Eduard Wagner that the Einsatzgruppen should arrest 10,000 and then another 20,000 Poles and bring them to concentration camps . The OKH was thus informed of their plans and procedures and agreed to them. The Einsatzgruppen were supposed to track down, arrest and murder up to 61,000 Poles "in accordance with the Führer’s special order" (so Heydrich 1940 in a retrospective note) according to a “ Special Investigation Book Poland ” compiled before the war under the code name “ Company Tannenberg ”. On September 3, Himmler ordered them to shoot all "Polish insurgents" (in fact mostly regular, scattered Polish soldiers) found armed on the spot. On September 7, 1939, Heydrich ordered the task force leaders "to render the leading strata of the population in Poland as harmless as possible."

- From September 3rd: Einsatzgruppe zbV ("for special use") under SS-Obergruppenführer Udo von Woyrsch and SS-Oberführer Otto Rasch . It consisted of four police battalions and a special command of the security police with 350 men. Their area of application was the Upper Silesian industrial area.

- From September 9th: Einsatzgruppe VI (Frankfurt / Oder) under SS-Oberführer Erich Naumann with two operational commands under:

- (1) SS-Sturmbannführer Franz Sommer ,

- (2) SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Flesch .

Her area of application was the Posen room .

- From September 12th: Einsatzkommando 16 (Danzig) under SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Tröger .

On September 21, 1939, Reinhard Heydrich issued a secret order to the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD to begin the temporarily planned concentration of Jews from the country in demarcated areas of the Polish cities ( ghettoization ). This should make it easier for the Jews to be controlled and used as slave labor for economic exploitation . There their assets could also be systematically recorded with the aim of Aryanization .

execution

Since the beginning of the war, the Einsatzgruppen committed targeted mass murders of Poles. The " Bromberger Blutsonntag " on 3./4. September, served them as well as the OKW as a welcome excuse to pass off their mass murders planned before the start of the war as retribution. By October 26, 1939, the end of the military administration, the Einsatzgruppen, other police units and members of the Wehrmacht murdered around 16,000 to 20,000 Poles in 714 executions.

During these weeks there were isolated conflicts with Wehrmacht officers who protested against the massacre . The Commander-in-Chief East, Colonel-General Johannes Blaskowitz , clearly criticized the actions of the SS and the police in several memoranda, as he was concerned about the morale of the troops and feared that the abused Polish population could now support riot movements so that military security would be endangered. The Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Colonel General Walther von Brauchitsch , tried overwhelmingly to dampen the indignation. He did not formulate a fundamental statement against the criminal occupation policy. At a meeting with Brauchitsch, Heydrich achieved greater independence for the Einsatzgruppen from the military administration in Poland. After Hitler appointed Himmler " Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Volkstum " on October 7, 1939 and released the Einsatzgruppen from Wehrmacht jurisdiction, they were able to act completely independently. After that, the number of those murdered by them rose significantly. According to conservative estimates, they murdered a total of 60,000 to 80,000 Poles between the beginning of the war and the spring of 1940.

Balkans

Serbia

In connection with the planning for the " Operation Barbarossa " (the attack on the Soviet Union planned for May / June 1941 since July 1940), the Balkan campaign was planned at relatively short notice and carried out in April 1941. In addition to the Einsatzgruppen for the Russian War, the Einsatzgruppe Serbia has been set up and trained with two Einsatzkommandos since March 1941 . From April 1941 to January 1942, its head was SS-Oberführer and Colonel of the Police Wilhelm Fuchs . He was followed in January 1942 by SS Oberführer Emanuel Schäfer . Their tasks and subordination were regulated between the high command of the army and the chief of the security police and the SD: They were supposed to fight " emigrants , saboteurs , terrorists ", but above all "communists and Jews". In January 1942 the task force was disbanded and the police duties were transferred to the HSSPF SS-Gruppenführer and Lieutenant General August Meyszner .

Croatia

In Croatia (NDH), Einsatzgruppe E became active from August 2, 1941: until April 24, 1943 under SS-Obersturmbannführer Ludwig Teichmann , until October 1944 under SS-Standartenführer Günther Herrmann , from November 1944 under SS-Oberführer and Police Colonel Wilhelm Fox . Other groups working there were:

- the Einsatzkommando 10b ( Vinkovci or later Esseg ) under SS-Obersturmbannführer and Oberregierungsrat Joachim Deumling (March 15, 1943 to January 27, 1945), then SS-Sturmbannführer Franz Sprinz (January 27, 1945 to May 8, 1945)

- the Einsatzkommando 11a ( Sarajevo ) under SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Rudolf Korndörfer (May 15, 1943 to September 9, 1943), then SS-Obersturmbannführer Anton Fest (September 9, 1943 to 1945)

- the Einsatzkommando 15 ( Banja Luka ) under SS-Hauptsturmführer Willi Wolter (June 12, 1943 to September 1944)

- Task Force 16 ( Knin )

- SS-Obersturmbannführer and Oberregierungsrat Johannes Thümmler (July 3, 1943 to September 11, 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Freitag (September 11, 1943 to October 28, 1944)

- Task Force Agram

- SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Rudolf Korndörfer (from September 9, 1943)

Soviet Union

In the opinion of the National Socialist leadership, the German-Soviet war was a “ worldview war ”: it was not only intended to conquer Soviet territory and defeat the Soviet armed forces, but also to destroy the Soviet leadership elite, the structures of their state and their ideology, known as “ Jewish Bolshevism “Were designated. Since March 1941, both the Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen, which were set up from May 1941 for special systematic murder tasks, had been aimed at this goal.

Positioning and training

In May 1941, four task forces, each with battalion strength, were set up in the border police school in Pretzsch and the surrounding towns of Bad Düben and Bad Schmiedeberg . The personnel manager of the RSHA, SS-Brigadführer Bruno Straßenbach, was responsible for this and commissioned the head of the school, Tummler, with the training. Some of the leaders of the task forces were delegated from the leadership of the RSHA. Two of the task force leaders came from the RSHA: Otto Ohlendorf , head of SD Inland, and Arthur Nebe , head of the criminal investigation department. Most of the officers in the Einsatzgruppen were academics between the ages of 30 and 40, and many had doctorates . While the personnel for the leading positions was selected or at least confirmed by Himmler and Heydrich, the units were preferably filled with personnel from the ranks of the Sipo, Orpo, Kripo and SD, who had already been used for similar purposes without being used for the Selection of special guidelines existed. Rather, the heads of department of the RSHA had to assign a predetermined number of their employees. For example, the entire course of the Sipo driving school in Berlin was assigned to the task forces. A special selection based on political reliability did not take place, according to a statement by Bruno Linienbach. This was already assumed by the members of the Sipo and the SD due to the employment requirements for these organizations. The necessary auxiliary personnel such as drivers, radio operators, interpreters, typists, etc. consisted in part of emergency services who did not belong to the SS. A company from Reserve Police Battalion 9, later from Reserve Police Battalion 3 , was assigned to each of the Einsatzgruppen A – C for reinforcement.

Example of the number of personnel in a task force (here EGr A):

- Waffen-SS: 340 (34%)

- Ordinance Police: 133 (13.4%)

- Secret State Police: 89 (9.0%)

- Auxiliary Police: 87 (8.8%)

- Criminal Police: 41 (4.1%)

- Security service: 35 (3.5%)

- Motorcyclists: 172

- Interpreter: 51

- Telex typists: 3

- Radio operator: 8

- Administration: 18

- Female employees: 13

Total: 990

Order and subordination

In March 1941, Adolf Hitler granted Himmler special powers to set up special troops to wage the “ideological war”. The guidelines on special areas for directive No. 21 (Barbarossa case) of the High Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) of March 13, 1941 said:

“In the area of operations of the army, the Reichsführer SS receives special tasks on behalf of the Führer in preparation for the political administration , which result from the final battle between two opposing political systems. In the context of these tasks, the Reichsführer SS acts independently and on his own responsibility. Incidentally, the ob. d. H. [Commander-in-Chief of the Army] and the executive powers delegated by him are not affected by this. The Reichsführer SS ensures that operations are not disrupted while his duties are being carried out. The OKH [High Command of the Army] regulates further details directly with the Reichsführer SS. "

According to the division of the Eastern Army into three army groups , initially three, then four Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD with a total strength of about 3,000 men with the letters A to D (running from north to south) were set up. The workforce fluctuated between 500 (EGr D) and 990 (EGr A) men. The Einsatzgruppen were divided into Einsatzkommandos (EK) and Sonderkommandos (SK) (consecutively numbered), which were about 70 to 120 men strong and in turn were divided into 20 to 30 men strong sub-commands. The technical and disciplinary authority as well as the judicial authority lay with the chief of the security police and the SD Reinhard Heydrich.

A written order for the general extermination of the Jews in the conquered areas has not been handed down and has not been indirectly documented by witnesses. The entire complex was formulated in a veiled manner, and attempts were made to keep the circle of those informed narrowly. A received letter from Heydrich dated July 2, 1941 to the Higher SS and Police Leaders (HSSPF) informed them in concise form about the instructions that he had personally given the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen and their commandos in Berlin on June 17. The key phrase is:

“Even if all the measures to be taken are ultimately to be geared towards the ultimate goal [the economic pacification of the conquered eastern region], on which the emphasis has to be placed, they are nevertheless in view of the decades-long Bolshevik organization of the country with ruthless severity on the most comprehensive Area. "

The following was a list of those to be executed:

- all functionaries of the Comintern (like the communist professional politicians in general)

- the higher, middle and radical lower functionaries of the party, the central committees, the district and regional committees

- People's Commissars

- Jews in party and state positions

- other radical elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins, agitators, etc.)

It is unclear when the murder orders were extended to all Jews in Soviet territories, including women, children and the elderly. Some researchers see Heydrich's verbal orders of June 17, 1941 as authorization to murder Jews as unrestricted as possible, since the target groups named there were only vaguely defined and suggested equating communist functionaries with Jews. Others date the expansion of the orders to August 15, 1941, when Himmler attended a mass shooting in Minsk and encouraged the perpetrators to do their necessary job. From then on, the indiscriminate murder of Jews became the rule. Heydrich instructed the task force leaders to burn their written orders immediately; four of them subsequently resigned from their posts.

Relationship to the armed forces

The relationship between the Einsatzgruppen and the Wehrmacht was regulated in a written agreement between Heydrich and the Army Quartermaster General Eduard Wagner at the end of March 1941, which the Commander-in-Chief of the Army Walther von Brauchitsch signed on April 28th. It provided for a separation of duties between the task forces and their commands. The rear army area was assigned to the Einsatzkommandos as the operational area , while the special commands in the rear army area were only to be used with a limited scope of tasks.

In the agreement it says u. a .:

- “The implementation of special security police tasks outside of the troops necessitates the deployment of special units of the security police (SD) in the operational area. [...]

- 1.) Tasks:

- a) In the rear army area:

- Securing of objects (material, archives, files of anti-Reich or anti-state organizations, associations, groups, etc.) as well as particularly important individuals (leading emigrants, saboteurs, terrorists, etc.) [...] before operations begin.

- b) In the rear army area:

- Researching and combating the anti-state and anti-imperial efforts, insofar as they are not incorporated into the enemy armed forces , as well as general information of the commanders of the rear army areas about the political situation. [...]

- The Sonderkommandos are entitled to take executive measures against the civilian population on their own responsibility. [...] "

The authorization given in the last sentence represents the dominant task from a historical point of view, the "special treatment of potential opponents" , which is a secret imperial matter . The agreed separation of duties in rear army and rear army territory disappeared very quickly in practice.

Deviating from the regulation during the attack on Poland, the Einsatzgruppen were only subordinate to the army with regard to marching, food and accommodation. The Wehrmacht arranged these logistical services for them.

The guidelines for the handling of political commissars of the OKW of June 6, 1941 (“commissar order”) obliged the armed forces to hand over commissars who were apprehended in the rear of the army to the task forces or task forces of the security police and the SD.

In addition, the management of the prisoner-of-war camps was provided with task forces of the security police and the SD to sort out “politically unsustainable elements” from civilians in the prison camps and those who “appear particularly trustworthy and therefore for use in the reconstruction of the occupied territories are usable ”and had to decide on their further fate ( “ Guidelines for the segregation of civilians and suspected prisoners of war of the Eastern campaign in the prisoner of war camps in the occupied territory, in the operational area, in the general government and in the camps in the Reich territory ”of the chief of Sipo and of the SD of July 17, 1941).

Involvement of the higher SS and police leaders

Before the conquered territories of the Soviet Union were placed under civil administration, the Wehrmacht first formed a military administration from its own troops in the rear army areas. In a parallel organization to these Wehrmacht troops , SS troops , police troops and security police were deployed under the so-called Higher SS and Police Leaders (HSSPF), which formed a separate instrument directly subordinate to Himmler and claimed their own responsibility. These associations were additionally strengthened by local police auxiliaries who operated under names such as “Schutzmannschaft” or “Selbstschutz” (including ethnic Germans). These HSSPF troops provided considerable support for the Einsatzgruppen.

For example, the task forces were formed by the Higher SS and Police Leader North ( Riga ), Group Leader Hans-Adolf Prützmann , Center ( Minsk ), Group Leader Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski and South ( Kiev ), Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln , each with a regiment of the Ordnungspolizei as well Units of the Waffen-SS supported. In mid-1942, Brigadefuhrer Gerret Korsemann joined as HSSPF Caucasus.

Indigenous non-Russian population groups as auxiliary workers

According to Himmler's order No. 1, the aim of German occupation policy was to use anti-Semitism to activate nationalist, non-Russian population groups and local helpers as supporters of Einsatzgruppen and BdS.

Task Force A organized "spontaneous" pogroms in Lithuania , whose nationalists, especially the Iron Wolf organization , were strongly anti-Semitic. About 5,000 Jews fell victim to them. In Latvia the came reports of the Einsatzgruppen , according to 400 Jews in pogroms. In Estonia , efforts to unleash pogroms failed completely.

Attempts to recruit collaborators as organized helpers resulted in significantly higher numbers of victims: In Lithuania, around 22,000 Jewish residents were murdered by local "partisans", as well as a large but indeterminate number who were killed by Lithuanian helpers who were directly involved Actions of the Einsatzkommandos were involved. In Latvia, the number of Jewish victims of the Thunder Cross is unknown.

Organization and leaders of the task forces

Task Force A

1. Strength and areas of application:

- approx. 990 men

- Area of Army Group A or North in the Baltic States

2. Locations of the staff:

- Pleskau (from July 18, 1941)

- Novoselje (from July 23, 1941)

- Pesje (from August 24, 1941)

- Kikerino (from September 2, 1941)

- Meshno and Riga (end of September 1941)

- Krasnogwardeisk (from October 7, 1941)

- Nataljewka (from November 1942)

3. Leader:

- SS Brigade Leader and Major General of the Police Walter Stahlecker (June 1941 to † March 23, 1942)

- SS Brigade Leader and Major General of the Police Heinz Jost (March 24 to September 1942)

- SS-Oberführer and Colonel of the Police Humbert Achamer-Pifrader (September 10, 1942 to September 4, 1943)

- SS-Oberführer Friedrich Panzinger (September 4, 1943 to May 1944)

- SS-Oberführer and Police Colonel Wilhelm Fuchs (May to October 1944)

- 4. Partial commands (before restructuring)

Sonderkommando 1a

- SS-Standartenführer Martin Sandberger (June 1941 to autumn 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Bernhard Baatz (October 30, 1943 to October 15, 1944)

Sonderkommando 1b

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Ehrlinger (June to December 3, 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Eduard Strauch (December 3, 1941 to June 1943)

- SS-Standartenführer Erich Isselhorst (June 30 to October 1943)

Task Force 2

- SS-Sturmbannführer and Government Councilor Rudolf Batz (June to November 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Eduard Strauch (November 4 to December 3, 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Lange (December 3, 1941 to?)

Task Force 3

- SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger (June 1941 to autumn 1943)

- SS-Oberführer Wilhelm Fuchs (September 15, 1943 to May 6, 1944)

- SS-Standartenführer Hans-Joachim Böhme (May 11, 1944 to January 1, 1945)

- 5. Partial commands after the reorganization in 1942/43

Task Force 1a

- SS-Standartenführer Martin Sandberger (mid to autumn 1942)

Task Force 1b

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Hubig (mid to October 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Manfred Pechau (from October 1942)

Task Force 1c

- SS-Sturmbannführer Kurt Graaf (August to November 1942)

Task Force 1

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl Tschierschky (1942 for a short time)

- SS-Standartenführer Erich Isselhorst (November 1942 to June 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Bernhard Baatz (from August 1, 1943 to October 15, 1944)

Task Force 2

- SS-Sturmbannführer Manfred Pechau (March 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Reinhard Breder (March 26 to July / August 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Oswald Poche (from July / August 1943)

Task Force 3

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl Traut (November 1942 to May (?) 1943)

Task Force B

1. Strength and areas of application:

- approx. 655 men

- Area of Army Group B or in the middle of Belarus

2. Locations of the staff:

- Wolkowysk (from July 3, 1941)

- Slonim (from July 5, 1941)

- Minsk (from July 6, 1941)

- Smolensk (from August 5, 1941)

3. Leader:

- SS-Gruppenführer and Lieutenant General Arthur Nebe (June to October 1941)

- SS Brigade Leader and Major General of the Police Erich Naumann (November 1941 to February / March 1943)

- SS-Oberführer Horst Böhme (March 12 to August 28, 1943)

- SS-Standartenführer Erich Ehrlinger (August 28, 1943 to April 1944)

- SS-Standartenführer Heinrich Seetzen (April 28 to August 1944)

- SS-Oberführer Horst Böhme (August 12, 1944 to?)

- 4. Partial commands

Sonderkommando 7a

- SS-Standartenführer Walter Blume (June to September 1941)

- SS-Standartenführer Eugen Steimle (September to December 1941)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt Matschke (December 1941 to February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Albert Rapp (February 1942 to January 28, 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Helmut Looß (June 1943 to June 1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Bast (June to October / November 1944)

Sonderkommando 7b

- SS-Sturmbannführer Günther Rausch (June 1941 to January / February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Ott (February 1942 to January 1943, possibly from July to October 1942 represented by SS-Sturmbannführer Josef Auinger )

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Georg Rabe (January / February 1943 to October 1944)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Hotzel (October 1944 to 1945)

Sonderkommando 7c / Pre-Command Moscow

- SS-Standartenführer Franz Six (June to August 20, 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Waldemar Klingelhöfer (August to December 1941, from October 1941 "Pre-Command Group Staff")

- SS-Sturmbannführer Erich Körting (September to December 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Bock (December 1941 to June 1942)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Rudolf Schmücker (June to late autumn 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Bluhm (late autumn 1942 to July 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Eckhardt (July to December 1943), then merged with SK 7a

Task Force 8

- SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Bradfisch (June 1941 to April 1, 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Heinz Richter (April 1 to September 21, 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Isselhorst (September to November 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Schindhelm (November 13, 1942 to October 1943 or 1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Renndorfer (April 1944 to?)

Task Force 9

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Alfred Filbert (June to October 20, 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Oswald Schäfer (October 1941 to February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Wilhelm Wiebens (February 1942 to January 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Buchardt (January 1943 to October 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Werner Kämpf (October 1943 to March 1944)

- Subdivision into task forces

The detective commissioner and SS-Untersturmführer Wilhelm Döring was assigned to Einsatzkommando 8 under Otto Bradfisch in the summer of 1941. Döring led the task force 5, which included two detectives, 2 members of the Gestapo, 1 member of the SD, 3 drivers, 7 members of the Waffen-SS and 1 interpreter with the rank of SS-Untersturmführer.

Task Force C

1. Strength and areas of application:

- about 700 men

- Area of Army Group C or South in northern and central Ukraine ( Babyn Yar and Drobyzkyj Yar )

2. Locations of the staff:

- Lemberg (from July 1, 1941)

- Zhitomir (from July 18, 1941)

- Pervomaisk (from August 17, 1941)

- Novo-Ukrainska (from September 19, 1941)

- Kiev (from September 25, 1941)

- Starobelsk (from September 1942)

- Poltava (from February 1943)

3. Leader:

- SS Brigade Leader and Major General of the Police Otto Rasch (June to September 1941)

- SS Brigade Leader and Major General of the Police Max Thomas (October 1941 to August 28, 1943)

- SS-Oberführer Horst Böhme (September 6, 1943 to March 1944)

- 4. Partial commands

Sonderkommando 4a

- SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel (June 1941 to January 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Erwin Weinmann (January 13 to July 1942)

- SS-Standartenführer Eugen Steimle (August 1942 to January 15, 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Theodor Christensen (January to the end of 1943)

Sonderkommando 4b

- SS-Standartenführer Günther Herrmann (June to September 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Braune (October 1941 to March 21, 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Walter Haensch (March to July 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer August Meier (July to November 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer and Councilor Friedrich Suhr (November 1942 to August 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Waldemar Krause (August 1943 to January 1944)

Task Force 5

- SS-Oberführer Erwin Schulz (June to September 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer August Meier (September 1941 to January 1942)

Task Force 6

- SS-Sturmbannführer Erhard Kroeger (June to November 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Robert Mohr (November 1941 to September 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Ernst Biberstein (September 1942 to May (?) 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer and Councilor Friedrich Suhr (August to November 1943)

Task Force D

See: Einsatzgruppe D of the Security Police and the SD

Strength and areas of application:

- about 600 men

- Area of the 11th Army in southern Ukraine , Bessarabia , Kishinev and the Crimea

Others

- The Tilsit task force under SS-Standartenführer Hans-Joachim Böhme and SS-Oberführer Bernhard Fischer-Schweder was formed on June 22, 1941 and carried out mass shootings of Jews and Communists in the former border area.

- The Einsatzgruppe zbV had additional "Einsatzkommandos" or "Einsatztrupps" set up for Galicia on behalf of the RSHA under SS-Oberführer Karl Eberhard Schöngarth . In July 1941, they were assembled from members of the security police in the General Government and stationed in Lemberg , Brest-Litovsk and Białystok . They were dissolved again in autumn 1941.

- Sonderkommando 1005 under SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel was deployed from July 1942 to October 1944 to destroy traces of the Einsatzgruppen .

- During the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht in the later course of the German-Soviet war, Einsatzgruppe F for Hungary, Einsatzgruppe G for Romania and Einsatzgruppe H for Slovakia were formed in 1944. Task Force G was no longer used.

commitment

The four Einsatzgruppen met in Bad Düben at the beginning of June 1941 in order to follow the Eastern Army after the war against the Soviet Union began to carry out their mission: "3,000 men hunted Russia's 5 million Jews." Of these, four million lived in the army conquered Russian territories. Of these, 1.5 million were able to escape the access of the Einsatzgruppen by fleeing, so that 2.5 million came into the sphere of influence of Heydrich's units.

The mass of Soviet Jews were completely surprised by the well-organized extermination actions of the Einsatzgruppen. The cities in particular, where 90% of the Jewish population lived, became a trap. Immediately after the conquest and occupation by the Wehrmacht, the special commandos of the Einsatzgruppen followed. Initially taking advantage of the naivety of their victims, they were prompted by posting posters and calling for a meeting at a central location or building. From there, they were then usually transported to the place of their killing under the pretext of resettlement or labor. After the fate intended for the Jews had spread among the population, the registration of the Jewish inhabitants was ensured with coercive measures. The villages and individual parts of the city were partially cordoned off with the help of Wehrmacht units using chains of posts and searched house by house.

The operational or special commandos operated largely independently. The manner in which their victims were captured and the executions differed only in details for the individual units. In the following, the corresponding passage from the judgment of the Regional Court of Munich I of July 21, 1961 in the criminal case against Otto Bradfisch and others should be cited as a representative of the basic procedure :

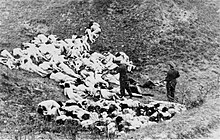

“In executing the order to annihilate the Jewish population in the east as well as other groups of the population who were also considered to be racially inferior and the functionaries of the Russian Communist Party, EK 8 carried out shooting operations after crossing the demarcation line established in 1939 between the German Reich and the Soviet Union Jews were killed. […] The recording of the Jews in the respective places affected - called 'overhaul' in the linguistic usage at the time - happened in such a way that the villages or streets were surrounded by some of the members of the task force and then the victims by other members of the commando Houses and apartments were randomly rounded up. The victims were then either transported immediately after their capture with the help of trucks to the previously determined and prepared shooting sites or held in suitable buildings (schools, factory buildings) or other locations until they were then the next day or a few days were later shot. Even during these so-called 'combing actions' there was physical abuse and, in individual cases, the killing of old and sick people who were no longer able to walk and were consequently shot in their homes or in their immediate vicinity.

The mass shootings took place outside the 'overtaken' town or village, with either natural depressions in the ground, abandoned infantry and artillery positions and, above all, anti-tank trenches or mass graves dug by the victims themselves as places of execution. In the executions that took place during the first weeks of the Russian campaign , only men between the ages of 18 and 65 were killed, while women and children were apparently initially spared. From August 1941 at the latest, however - already with the shootings in Minsk - people started killing men and women of all ages, as well as children. After the preparations were completed, the victims, who were unloaded from the trucks in the immediate vicinity of the firing pit and had to sit on the ground waiting for the further events, were either led to the pits by members of EK 8 or through alleys that were formed by members of the commando , to the pits, if necessary with the help of cane blows. After they had first given in their valuables and the well-preserved items of clothing, if they had not already done so when they were captured, they had to lie face down in the pit and were then shot in the back of the head. During the initial shooting actions ( Białystok , Baranowicze , Minsk ), but also occasionally later on the occasion of large-scale actions, execution platoons were put together from the members of the task forces and the assigned police officers , the strength of which corresponded to the number of groups of people driven to the shooting pit or individually Cases also had twice the strength, so that one or two shooters had to shoot a victim. These firing squads, which were equipped with carbines, were mostly composed of police officers and were given orders by a platoon leader of the subordinate police unit in accordance with the instructions given to him by the leadership of EK 8. During these executions carried out by the firing squad, it sometimes happened that the victims had to stand on the edge of the pit in order to be 'shot' into the pits afterwards.

In the course of the mission, however, people increasingly switched to stopping the shooting with rifle volleys and killing the people destined for execution with single fire from submachine guns. The reason for this was, on the one hand, that the shooting with rifle volleys took a relatively long time, and on the other hand, that the effect of the shots fired from very close range was so violent that the firing squad and other people involved in the actions of blood and brain parts of those killed were splashed, a circumstance which increased the already extraordinary mental stress of the men assigned to the execution squads so much that misses were often missed and the suffering of the victims was prolonged.

The shootings with submachine guns were usually carried out in such a way that the members of the task force designated to carry out the execution walked in the pit along the line of the people to be shot and killed one victim after the other with shots in the back of the head. However, this type of execution inevitably meant that some of the victims, lying on the poorly or not at all covered corpses and facing certain death, had to wait a long time before they themselves received the fatal shot. In some cases the killing of the victims was carried out in such a way that they were driven at a running pace to the shooting site, pushed into the pit and then shot while falling. While in the shootings in Białystok and Baranowicze, and in some cases also in the executions in Minsk, the bodies were more or less well covered with sand or earth before the next group was driven or brought up to the pit, there was such a cover the later shooting operations only rarely take place, so that the subsequent victims, insofar as they were shot in the pit, each had to lie on the corpses of those killed immediately before. But even in those cases in which the corpses had been thrown with sand or earth, the subsequent victims felt the bodies of their fellow fates who had been killed, whose body parts often protruded from the thin layer of earth or sand.

A doctor was not involved in the executions. If one of the victims still showed signs of life, a member of the commando, usually a Führer, gave him a margin with a pistol.

The execution sites were cordoned off by members of the task force or police officers subordinate to it, so that there was no way for people waiting for their death in the immediate vicinity of the shooting pits to escape their fate. Rather, they had the opportunity - this circumstance represents a particular aggravation of their suffering - to hear the crack of rifle volleys or machine pistol shots and in some cases even to watch the shootings to which neighbors, friends and relatives fell victim. In the face of this gruesome fate, the victims often burst into crying and wailing, praying loudly, and trying to plead their innocence. In some cases, however, they went to their deaths calmly and composed. "

Although Himmler repeatedly emphasized that he was solely responsible before God and Hitler for everything that the Einsatzgruppen had to carry out in the East , so that the horrific events could not lead to a burden of conscience for the individual man, pseudo-justifications were given for all killings. So it was once the fear of epidemic dangers , then alleged partisans or suspected partisans or the general “Jewish danger” that justified the shootings. Inmates of lunatic asylums had to be shot because they represented a danger to the environment, etc. The psychological justification went so far that, without such a sham justification, no further liquidations were carried out.

Event reports USSR

With the start of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) collected the reports requested by the Einsatzkommandos and their staffs and initially compiled them as "Event reports USSR " (EM) and after May 1 as weekly "reports from the occupied territories " together. In 195 "incident reports" and 55 "reports from the occupied eastern territories", Heydrich's Berlin headquarters documented on approx. 4500 pages what she thought was important about German occupation policy and the measures it took to "pacify" the conquered area. Klaus-Michael Mallmann , Andrej Angrick and other historians see the source value of the reports primarily in their evidential value for the fact of at least 535,000 - predominantly Jewish - murder victims of the Einsatzgruppen up to spring 1942 alone, their problem in their justifying representation from the "optics of the Perpetrator ".

The incoming reports were compiled in Section IV A 1 , headed by SS-Sturmbannführer Josef Vogt , under the supervision of Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller , from May 1, 1942 and their renaming to "Reports from the Occupied Eastern Territories" by Section IV D (" Occupied Eastern Territories ”) under Gustav Nosske , who had just been replaced as chief of Einsatzkommando 12. Initially, they only had a very small group of recipients within the RSHA. The mailing list for the first event report shows only Himmler, Heydrich and their seven heads of office as mailing lists. Almost two months later, the EM 53 was distributed to 48 recipients. The reports on the mass murder of Soviet Jews often only take up a relatively small part of the total reporting, which also contains many banalities and models of justification. Both court proceedings and historiography serve as a “central source for coming to terms with German crimes in World War II ”. The originals can be found under the shelfmarks R 58 / 214-221 in the Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde, copies in a number of other archives, e.g. B. also at the Institute for Contemporary History . From July 19, 1941, according to the distributor, the reports were also sent to the " OKW -leitungsstab-Oberstleutnant Tippelskirch". According to Mallmann and others, this fact shows that "post-war allegations by high OKW officers that they did not learn anything about the actions of the EC or that they only heard about it at a late stage" were a "legend".

The Ulm Regional Court determined the creation and use of the "incident reports" and stated the following in its judgment of August 29, 1958 ( Ulm Task Force Trial ):

“The task forces were instructed to submit activity reports on their activities to the head of their task force. For their part, the task force leaders had, as instructed, to report the reports they received from their task force leaders to the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), Amt IV ( Müller ) by couriers, radio or telex . In Department A 1 of Office IV of the RSHA, which is under the direction of Government Councilor Jupp Vogt, the reports received by this office and any reports received by Office III from the SD were evaluated and compiled according to a system determined by Office Chief Müller, so u. a. von Vogt himself or from the department members Fum. (Witness) and Dr. Kno. (Witness). The event reports written on matrices were presented to the head of office Müller for review, with some minor changes being made by him. In any case, the event reports by and large gave the content of the original reports from the Einsatzgruppen respectively. -commands, especially the exact numbers of those killed, again.

The USSR event reports were numbered consecutively, with the date and with the heading 'The Chief of the Security Police and the SD, Office IV A 1 – B No. 1 B / 41 g.Rs.' as well as with the obvious imprint 'Geheime Reichssache' and forwarded to interested party and government agencies, above all to the heads of office of the RSHA, according to a very specific, originally very low distribution plan.

The fact that the incident reports fell under the highest level of secrecy protection as a 'secret Reich business' ensured that only a very small group of people learned about the mass extermination measures carried out by the Einsatzgruppen. In order to prevent the leakage of news about the mass extermination measures into the German people, the individual members of the task forces were obliged to maintain the strictest silence. In addition, by a decree of the Reichsführer SS of November 1941, photography of the executions was prohibited and the confiscation and extermination or Order to send the photographs taken up to this point to the RSHA as documentary material. As far as such photos could be secured by the Allied forces, they were used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials. "

From the extremely plentiful material, some passages from the incident reports on the executive activities of Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C, which carried out the mass murder of the Jewish population of Kiev in Babyn Yar on September 29 and 30, 1941, are cited for illustration .

No. 97 of September 28, 1941:

"Pre-command 4a since 19.9. directly with fighting troops in Kiev. [...] Allegedly 150,000 Jews present. […] In the first action 1,600 arrests. Measures initiated to cover all Judaism. Execution of at least 50,000 Jews planned. Wehrmacht welcomes measures and requests radical action. City Commandant Major General Kurt Eberhard endorsed the public execution of 20 Jews. "

No. 101 of October 2, 1941:

"The Sonderkommando 4a executed 33,771 Jews in Kiev on September 29 and 30, 1941 in cooperation with the group staff and two commandos of the South Police Regiment ."

No. 128 of November 3, 1941 of Einsatzgruppe C:

“As far as the actual executive is concerned, around 80,000 people have so far been liquidated by the commandos of the task force. These include around 8,000 people who, on the basis of investigations, have been found to be anti-German or Bolshevik activities. The remainder has been taken care of due to retaliation. Several retaliatory measures were carried out as part of large-scale operations. The largest of these actions took place immediately after the capture of Kiev; only Jews with their entire family were used for this purpose. The difficulties that arose in carrying out such a large-scale operation - especially with regard to the registration - were overcome in Kiev by the fact that the wall was posted on the Jewish population was requested to resettle. Although at first only about 5,000 to 6,000 Jews were expected to be involved, more than 30,000 Jews turned up who, thanks to an extremely skillful organization, believed in their resettlement until immediately before the execution. Even if a total of around 75,000 Jews have been liquidated in this way up to now, it is already clear that a solution to the Jewish problem will not be possible with this. It has indeed been possible to bring about a complete settlement of the Jewish problem, especially in smaller towns and villages; In larger cities, on the other hand, the observation is always made that after such an execution all Jews have disappeared, but if a commando returns after a certain period of time, a number of Jews is determined again and again, which is quite considerably the number of Jews executed exceeds. "

No. 132 of November 12, 1941:

“The number of executions carried out by Sonderkommando 4a has meanwhile increased to 55,432. In the sum of those executed by Sonderkommando 4a in the second half of October 1941 up to the reporting date, in addition to a relatively small number of political functionaries, active communists, saboteurs, etc., primarily Jews, and here again a large number of those who did Jewish prisoners of war transferred by the Wehrmacht. In Borispol , at the request of the commandant of the prisoner-of-war camp there, a platoon of Sonderkommando 4a shot 752 and on October 18, 1941 357 Jewish prisoners of war, including some commissioners and 78 Jewish wounded handed over by the camp doctor. At the same time, the same train executed 24 partisans and communists who had been arrested by the local commandant in Borispol. It should be noted that the smooth implementation of the operation in Borispol was not least due to the active support from the Wehrmacht services there. [...] In the area of Sonderkommando 4b, the Wehrmacht showed full understanding for the security police activities of the Sonderkommando. "

Second wave of killings

This phase, defined as the first wave of killing, was followed by a second wave after an intermediate phase, which, depending on the unit and area of operation, overlapped with the first and is to be scheduled from autumn 1941. In this second wave of killings, Wehrmacht personnel also increasingly took part. The Einsatzgruppen were subordinated to the higher SS and police commanders and the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen were appointed commanders of the Security Police.

Stationary commands of the Einsatzgruppen in the civil administration

The Einsatzgruppen followed the advance of the German Army Groups to the east. After the initial military administration of the conquered areas, the Reichskommissariat Ostland and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine were created, which received civil administrations. There were now stationary offices, commander of the security police and the security service (BdS) and commander of the security police and security service (KdS). As a rule, they were taken over by the HSSPF and their SS and police troops, but also by Einsatzgruppe leaders. The head of Einsatzgruppe A, Walter Stahlecker , had been using the title of BdS in Riga since September 29, 1941 , and Sonderkommando 1a became the KdS office with its headquarters in Reval and with several branch offices. In addition to these stationary offices, there were mobile commandos of Einsatzgruppe A in the Leningrad front area .

The aim of the second phase, with the killing of the remaining Jews in the occupied area, was the complete annihilation of the Jewish part of the population and, based on previous experience and the increased forces, was far more efficient than the first wave of killing. In addition to the organizational consolidation, the task forces were also strengthened by local so-called “ protection teams ” (Schuma), which finally had a strength of 47,974 men at the end of 1942. In addition, there were the so-called " gang fighting associations" with a strength of 14,953 Germans and 238,105 volunteers from the East (Hiwis) at the end of 1942. The "chief of the gang fighting associations", the HSSPF center group leader Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, was also able to perform certain actions ad hoc to fall back on Wehrmacht members of the security divisions, police and SS as well as personnel of the Einsatzgruppen, which were then regarded as "gang fighting units" and shot the Jews who fled into the forests as partisans. This becomes clear, for example, in the balance sheet of the “ Aktion Sumpffieber ” in February / March 1942. 389 partisans, 1,774 suspects and 8,350 Jews were shot.

The number of victims in this second phase is put at 400,000, so that the total number of Jewish victims of the mobile extermination campaigns was around 900,000. Together with the additional killings by Einsatzgruppen, the HSSPF, gang combat units and the German and Romanian armies, the number of Jewish victims of the mobile extermination campaign in the Soviet Union is around 1.35 million.

Type of killing "gas truck"

The shooting of the victims, especially women and children, caused the perpetrators increasing psychological problems. A process was therefore sought that would largely exclude the direct confrontation with the victims and the bloody craft. For this the "gasification" offered to the victims, as already at the Aktion T4 , the euphemistically as euthanasia was practiced killing designated by mentally and physically disabled, in 1940 and 1941st The carbon monoxide used and filled in steel bottles could only be transported over long distances with great effort. The head of Department II D in the RSHA , Obersturmbannführer Walter Rauff , therefore developed a plan to equip trucks with a closed body and use them as mobile gas chambers . In order to kill the victims, the engine exhaust gases should be fed into the closed structure. After a "test gassing" of Soviet prisoners of war in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in autumn 1941, the gas vans, referred to as S (onder) wagons in the camouflage language of the Endlöser, were delivered to the task forces by June 1942 in a number of 20 vehicles.

A member of EK 4a described the function and use of these gas trucks during his interrogation by the public prosecutor's office after the war as follows:

“There were two gas vans in use. I've seen them myself. They drove into the prison yard, and the Jews, men, women and children, had to get into the car directly from the cell. I also know the gas vans inside. They were covered with sheet metal and covered with a wooden grate. The exhaust gases were directed into the interior of the car. I can still hear the knocking and the screams from the Jews: 'Dear Germans, let us out!' The Jews went through our barriers and into the car without hesitation. The driver started the engine after the doors were closed. He then drove to an area outside Poltava. I, too, was at that place outside Poltava when the car stopped. When the doors were opened, smoke came out first and then a ball of tense people. It was a terrible picture. "

Overall, however, the system of mobile gas vans did not meet expectations, so that the first extermination camp in Kulmhof ( Chełmno ) was set up for the extermination of Jews in the province of Posen (Poznań) and in Litzmannstadt ( Łódź ) . The Lange Sonderkommando put together for this purpose under Hauptsturmführer Herbert Lange of the same name used three gas trucks in stationary use. The victims were concentrated in Kulmhof and imprisoned until they were killed. This happened in the gas truck during the transport to the so-called “forest camp”, where the corpses were buried or burned. In 1962/63, the Bonn jury court found the killing of at least 152,676 people in Kulmhof. Since only evidence that could be used in court was admitted, the actual number of victims is certainly far higher.

Transport to the extermination camp

The genocide carried out by the SS Einsatzgruppen in the east reached its climax in terms of both the number of victims and the systematic nature of the murders, ultimately as part of the “ Aktion Reinhardt ” 1942/43 and the establishment of the three extermination camps Belzec , Sobibor and Treblinka . After the dissolution of these camps, the Nazi took over a concentration camp (KZ) Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek the task of now factory-organized mass killings of the persecuted Jews in gas chambers with the agent Zyklon B .

Trace destruction

The Nazi regime had individual mass murders such as those in Kiev (Babyn Yar) and Lubny documented, for example with photographs by the German war correspondent Johannes Hähle (1906–1944). After the massacre, Sonderkommando 4a reported “trouble-free” execution. Towards the end of the second wave of killings, however, the traces of the murders should be covered because of the advance of the Red Army. The piles of corpses, which were barely buried, bear witness to the extermination actions of the Einsatzgruppen. The corpses, inflated by the decomposition process, rose and rose again to the surface. In May 1943, Himmler therefore ordered that traces of the executions be covered. The former commander of the SK 4a, SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel , who had already gained experience with the excavation and cremation of corpses in Chelmno , was commissioned with this. For this purpose, Blobel put together its own special command called “1005” ( Sonderkommando 1005 ), which had to open the mass graves and burn the corpses. However, he was only able to cover part of the trail before the Red Army finally recaptured the affected areas in 1944.

Casualty numbers

From June 1941 to 1943 the Einsatzgruppen murdered at least 600,000 people in the Soviet Union, according to other estimates up to one and a half million people. The large deviations in the number of victims arise for a number of reasons:

- Reliable death statistics in the sense of a death register do not exist. All information is calculated and checked for plausibility; they are based on

- Mission reports of the task forces, which are often not reliable in terms of their figures and the number of victims is rather too high to appear in a better light to superiors,

- Population statistics before and after the war, made more difficult by refugee and resettlement movements between 1939/1941 ( Hitler-Stalin Pact ) and after the liberation of the territories by the Red Army,

- Witness reports from relatives of the victims and from uninvolved local residents,

- Statements by defendants and accomplices in trials in the post-war period and

- forensic results from mass graves found.

- Various statistics use different temporal and spatial delimitations of the actions of the Einsatzgruppen, which were transferred to stationary units in 1942 (1943 at the latest) under the command of the BdS / KdS responsible for the respective region . Some statistics only include the mobile killings, which were essentially complete by the summer of 1942, while other statistics also include the acts of the stationary units.

- Murders that were not committed directly by the Einsatzgruppen, but instead were carried out in pogroms and shootings by collaborating locals, relief and protection teams, Orpo and Sipo under the command of the EG, Wehrmacht, are assigned to the Einsatzgruppen in some statistics, not in others . The demarcation is difficult per se, since the participation of locals in the acts was a declared aim of the SD and incited rumors, posters, etc. were circulated for this purpose. The numerically small EC units were also regularly reinforced by units of Wehrmacht security divisions, order police , field commanders, etc., which were mostly responsible for guarding and locking off the mass murders.

- While in the vast majority of cases in 1941 the fight against Soviet partisans was only a pretext or a welcome occasion for carrying out mass shootings, the number of partisans and the fight against them increased sharply by 1942/1943 at the latest, first in Belarus and parts of Ukraine. then with the approach of the Red Army in the other occupied territories. The people murdered by mobile units of the SS, Wehrmacht, Orpo and by local protection teams in the course of fighting partisans and the " scorched earth policy " are in some statistics partially assigned to the Einsatzgruppen, especially since the methods (mass shootings) and the participants who can be seen by witnesses are different (Officers with the SD diamond ) partially covered.

- The murdered Jews, who by far made up the majority of the Einsatzgruppe victims, are listed separately in the Einsatzgruppen reports and also in evaluations of the secondary literature. In comparison and tabulation, these different counting methods lead to deviations.

At the end of 1941, the Einsatzgruppen reported the following figures:

- EGr A: 249,420 Jews killed

- EGr B: 45,467 Jews killed

- EGr C: 95,000 Jews killed

- EGr D: 92,000 Jews killed

The total number of Jews killed by all units involved by the end of 1941 was thus around 500,000. Task Force A was the first of the four task forces to attempt a systematic extermination of the Jews in their area of operations.

Other countries

During the Western campaign and various other military actions of the Wehrmacht, Einsatzgruppen were formed and active, but unlike the groups formed for the attack on Poland, the Balkans and the Soviet Union, they had no specific mass murder tasks. These include:

Task Force L (Cochem)

- SS standard leader Ludwig Hahn

Task Force Norway (SS-Oberführer, Colonel of the Police and Government Councilor Heinrich Fehlis )

- Task Force 1, Oslo: SS-Oberführer, Colonel of the Police and Government Councilor Heinrich Fehlis

- Task Force 2, Kristiansund

- Task Force 3, Stavanger

- Task Force 4, Bergen

- Task Force 5, Trondheim

- Task Force 6, Tromso

Task Force Iltis (Carinthia)

- SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel

Task Force France: Helmut Bone

Task Force Belgium: Erwin Weinmann

Task Force Netherlands

- SS standard leader Josef Kreuzer

- SS standard leader Hans Nockemann

- SS-Sturmbannführer Knolle

Task Force Luxembourg (1944/45)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Wilhelm Nölle

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Erich Hartmann

Task Force Tunis (1942/43)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Walter Rauff

Post-war proceedings against the perpetrators

The so-called Einsatzgruppen Trial was one of the Nuremberg follow-up trials , Case IX, which took place from 1947 to 1948 and in which 17 Einsatzgruppe leaders of the Schutzstaffel (SS) were convicted. The charges (according to the indictment of July 25, 1947) were crimes against humanity , war crimes and membership in criminal organizations. The United States brought charges. On April 10, 1948, fourteen death sentences were passed (of which only four were carried out), twice life imprisonment and five imprisonment sentences between 10 and 20 years. The last convicts were released in 1958 at the latest.

The Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial began in 1958 before the Ulm jury court and was directed against Gestapo, SD and police members who were involved in the shooting of Jews in the Lithuanian- German border area. The former police chief of Memel , Bernhard Fischer-Schweder , and nine other members of Einsatzgruppe A stood before the court. In 1958 they were found guilty of 4,000 cases of murder and aiding and abetting murder and sentenced to between 3 and 15 years in prison.

literature

- Christopher Browning : Just normal men. The Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the “Final Solution” in Poland. Translated by Jürgen Peter Krause, rororo, Reinbek 1996, vol. 1690, ISBN 3-499-19968-8 .

- Philip W. Blood: Hitler's Bandit Hunters. The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe. Potomac Books, Washington 2006, ISBN 1-59797-021-2 .

- Hans Buchheim , Martin Broszat , Hans-Adolf Jacobsen , Helmut Krausnick: Anatomy of the SS state. Documentation. Munich 1967, ISBN 3-423-02915-3 . (2 volumes, frequent new editions, mostly in 2 separate volumes; the reports for the 1st of the Auschwitz trials ).

- Raul Hilberg : The annihilation of the European Jews. Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-596-24417-X .

- Peter Klein (Ed.): The Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union 1941/42. The activity and situation reports of the chief of the security police and the SD. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-89468-200-0 . (Source edition with introductions and comments on Einsatzgruppen A to D by Wolfgang Scheffler, Christian Gerlach , Dieter Pohl and Andrej Angrick).

- Helmut Krausnick , Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm: The troop of the Weltanschauung war. The Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and SD 1938–1942. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-421-01987-8 . (Basic work).

- Klaus-Michael Mallmann , Andrej Angrick , Jürgen Matthäus , Martin Cüppers (eds.): The "Event Reports USSR" 1941. Documents of the task forces in the Soviet Union (= publications of the Ludwigsburg Research Center , vol. 20). WBG, Darmstadt 2011, ISBN 978-3-534-24468-3 .

- Katrin Stoll: The production of truth. Criminal proceedings against former members of the Bialystok District Security Police. Diss. At the University of Bielefeld 2011, Legal History Series , Department 1, Volume 22, De Gruyter , Berlin / Boston 2012.

- Ralf Ogorreck: The task forces and the “Genesis of the Final Solution”. Metropol, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-926893-29-X .

- In French: Les “Einsatzgruppen”. The groupes d'intervention et the “genèse de la solution finale”. Translated by Olivier Mannoni . Calmann-Lévy, Paris 2007, ISBN 2-7021-3799-7 .

- Richard Rhodes: The German Murderers. The SS Einsatzgruppen and the Holocaust. Translated and edited by Jürgen Peter Krause, Bastei-Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 2004.

- Benjamin Ferencz : From Nuremberg to Rome. Review. A life for human rights. In: Structure . The Jewish monthly magazine. 72nd year, No. 2, Zurich 2006, p. 6, ISSN 0004-7813 . (Among other things, BF was chief prosecutor in the Einsatzgruppen trial.)

- Heinz Höhne : The order under the skull. Munich 1967 (Verlag S. Mohn, ISBN 3-570-05019-X ), 1983 (Goldmann, ISBN 978-3-442-11179-4 ), 1996 ( ISBN 978-3-893-50549-4 ), 2002 / 2008 (Bassermann Verlag, ISBN 978-3-8094-2255-6 ).

- Eugen Kogon , Hermann Langbein , Adalbert Rückerl a . a .: National Socialist mass killings using poison gas. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 1983, ISBN 3-596-24353-X (4th edition 2003, ISBN 978-3-596-24353-2 ).

- Hamburg Institute for Social Research (Ed.): Crimes of the Wehrmacht. Dimensions of the War of Extermination 1941–1944. Exhibition catalog, Hamburger Edition , January 2002, ISBN 3-930908-74-3 .

- Andrej Angrick : Occupation Policy and Mass Murder. Task Force D in the southern Soviet Union. 1941-1943. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-930908-91-3 .

- Harald Welzer , Michaela Christ: perpetrators. How normal people become mass murderers. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-596-16732-6 .

- Michael Wildt : Generation of the Unconditional. The leadership corps of the Reich Security Main Office. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 978-3-930908-87-5 .

- Alex J. Kay : Transition to Genocide, July 1941. Einsatzkommando 9 and the Annihilation of Soviet Jewry. In: Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Vol. 27, 2013, Issue 3, pp. 411–442 ( PDF ) (New findings on the transition to the murder of Jewish children and women by the Einsatzgruppen).

- Jürgen Matthäus, Jochen Böhler , Klaus-Michael Mallmann: War, Pacification, and Mass Murder, 1939: The Einsatzgruppen in Poland. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014, ISBN 978-1-442-23141-2 .

Movies

- The Ulm Trial. SS Einsatzgruppen in court. Documentation, Germany, script and direction: Eduard Erne, production: SWR , first broadcast: May 4, 2006.

- Radical Evil (film)

Web links

- NS archive: Documents on National Socialism - The affidavits of the Einsatzgruppen perpetrators ( Otto Ohlendorf , Paul Blobel , Erwin Schulz , Ernst Biberstein , Erich Naumann and Karl Jonas )

- Task forces from hagalil.com

- Task forces from the German Historical Museum

- Task Force Groups ( Memento from August 1, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Task Force Groups on deathcamps.org

- Book Review: Occupation Policy and Mass Murder. Task Force D in the southern Soviet Union 1941–1943

Individual evidence

- ^ Wolfgang Benz , Konrad Kwiet ( Center for Antisemitism Research , Technical University Berlin): Yearbook for Antisemitism Research. Volumes 7–8, Campus, 1998, p. 71.

- ↑ Saul Friedländer : The Third Reich and the Jews, Volume 2: The Years of Destruction 1939–1945. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54966-7 , pp. 52 f., 56, 74, 87 and 213.

- ^ Josef Fiala: "Austrians" in the SS Einsatzgruppen and SS Brigades. The killings in the Soviet Union 1941–1942. Diplomica Verlag, 2010, ISBN 3-8428-5015-8 , p. 18 .

- ↑ Barbara Distel : Best, Werner. In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Volume 2/1: People A – K. Walter de Gruyter / Sauer, ISBN 3-598-44159-2 , p. 75 .

- ↑ a b c Dieter Pohl : Persecution and mass murder in the Nazi era 1933–1945. Darmstadt 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Jörg Osterloh: National Socialist Persecution of Jews in the Reichsgau Sudetenland 1938–1945. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-57980-0 , p. 191 .

- ^ Franz Weisz: The Secret State Police, State Police Headquarters Vienna 1938–1945. Organization, working methods and personal issues. Diss. University of Vienna, Vienna 1991, p. 23.

- ^ Jörg Osterloh: National Socialist Persecution of Jews in the Reichsgau Sudetenland 1938–1945. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2006, pp. 191–193 .

- ↑ Horst Rohde: Hitler's first "Blitzkrieg" and its effects on Northeast Europe. In: Klaus A. Maier u. a., Military History Research Office (Ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War , Volume 2: The establishment of hegemony on the European continent. DVA, Stuttgart 1979, p. 82.

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 28. The task force "zbV" is not counted: p. 255, fn 10.

- ↑ Christopher Browning: Unleashing the Final Solution. National Socialist Jewish Policy 1939–1942. List Taschenbuch, 2006, ISBN 3-548-60637-7 , p. 36.

- ↑ a b Carsten Dams, Michael Stolle: The Gestapo. Rule and Terror in the Third Reich. CH Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 3-406-62898-2 , p. 140 .

- ^ Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Jochen Böhler, Jürgen Matthäus (eds.): Einsatzgruppen in Poland. Presentation and documentation. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 3-534-21353-X , p. 121.

- ↑ Jochen Böhler: The destruction of the neighborhood. The beginning of the war of extermination in Poland in 1939. In: Mike Schmeitzner, Katarzyna Stoklosa (ed.): Partner or opponent? German-Polish neighborhood in the century of dictatorships. Lit Verlag, 2008, ISBN 3-8258-1254-5 , p. 79 .

- ↑ Manfred Messerschmidt: "Greatest hardship ...": Crimes of the Wehrmacht in Poland, September / October 1939. (PDF; 2.2 MB). Friedrich Ebert Foundation , 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ a b Alexander Kranz (Military History Research Office, ed.): Reichsstatthalter Arthur Grieser and the "civil administration" in Wartheland 1939/40. Population policy in the first phase of German occupation in Poland. ISBN 3-941571-05-2 , p. 19 .

- ↑ Carsten Dams, Michael Stolle: The Gestapo. Rule and Terror in the Third Reich. CH Beck, Munich 2011, p. 141 .

- ↑ Ghettos. In: deathcamps.org. September 8, 2006, accessed February 10, 2015 .

- ^ Josef Fiala: "Austrians" in the SS Einsatzgruppen and SS Brigades. The killings in the Soviet Union 1941–1942. 2010, p. 29 .

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. The troop of the Weltanschauung war. Fischer TB, Frankfurt am Main 1985, pp. 78 f., 83-86.

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. The troop of the Weltanschauung war. Fischer TB, Frankfurt am Main 1985, p. 86 f.

- ^ Kerstin Freudiger: The legal processing of Nazi crimes. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147687-5 , p. 68 .

-

↑ For the structure and procedure, see Eberhard Jäckel , Peter Longerich , Julius H. Schoeps (Ed.): Enzyklopädie des Holocaust. The persecution and murder of the European Jews. Volume 1, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-87024-301-5 , pp. 393-400.

For the breakdown of the Einsatzgruppen, their commands and personnel, see Volume 3, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-87024-303-1 , pp. 1735-1738. - ↑ Document VEJ 7/15 - Bert Hoppe , Hiltrud Glass (edit.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. (Collection of sources), Volume 7: Soviet Union with annexed areas I. Occupied Soviet areas under German military administration, the Baltic States and Transnistria. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-58911-5 , pp. 145-148.

- ↑ Quoted from Helmut Krausnick : Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. The troops of the Weltanschauung war 1938–1942. Frankfurt a. M. 1998, p. 129.

- ^ Helmut Krausnick: Hitler's Einsatzgruppen. The troops of the Weltanschauung war 1938–1942. Frankfurt a. M. 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Roland G. Foerster: Operation Barbarossa. Oldenbourg, 1999, ISBN 3-486-55979-6 , p. 156 ( online excerpt ).

- ↑ Guido Knopp : Holocaust. Goldmann TB, Munich 2001, p. 103 ff.

- ↑ Facsimile in: Crimes of the Wehrmacht. P. 58 ff.

- ^ Gerd Robel: Soviet Union. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Dimension of the genocide. The number of Jewish victims of National Socialism. Munich 1991, ISBN 3-486-54631-7 , p. 511 ff.

- ↑ 213-12_0598 Rabe, Karl Hermann, u. a., for the shooting of around 3,000 Jews and communist functionaries in the period from June 1941 to the end of 1944 (activity as SK of Einsatzgruppe B) by members of SK 7b of Einsatzgruppe B (Hamburg public prosecutor's office 147 Js 34/67), 1941-1980 (Series). In: Hamburg State Archives. Hanseatic City of Hamburg, accessed April 30, 2018 .

- ^ LG Bonn, February 19, 1964. In: Justice and Nazi crimes . Collection of German convictions for Nazi homicidal crimes 1945–1966. Vol. XIX, edited by Irene Sagel-Grande, HH Fuchs, CF Rüter . University Press, Amsterdam 1978, No. 564, pp. 703–733: " Subject matter of the proceedings: shooting of Jewish men, women and children and Russian civilians suspected of being partisans in several executions in various places in Belarus, as well as of 16 neglected mentally ill children in Shumyachi." ( Memento of March 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive ), here p. 712.

- ↑ Hans Mommsen : Path to the European “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-423-30605-X , p. 117.

- ↑ Heinz Höhne: The order under the skull. P. 330.

- ^ Judgment of the Regional Court Munich I of July 21, 1961 (22 Ks 1/61). Quoted from: Irene Sagel-Grande (arr.): Justice and Nazi crimes. The criminal judgments issued from November 4, 1960 to November 21, 1961: serial no. 500–523. Volume 17. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1977, ISBN 90-6042-017-9 , p. 669 ff.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, p. 7 f.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, pp. 7–38.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, pp. 146–148, footnote 8. Thereafter, Lieutenant Colonel Werner von Tippelskirch, b. 1910, from January 1941 head of the quartermaster department in the OKW, recipient of messages No. 27–38.

- ^ Judgment of the Ulm Regional Court of August 29, 1958 (Ks 2/57). Quoted from: Irene Sagel-Grande (arr.): Justice and Nazi crimes. The criminal judgments issued from July 4th, 1958 to July 8th, 1959: Serial No. 465-480. Volume 15. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1976, ISBN 90-6042-015-2 , p. 36.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, pp. 589-600, here p. 598; the identity of the city commander is given on p. 600 in footnote 4.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, pp. 615–618, here p. 615.

- ↑ Klaus-Michael Mallmann u. a. (Ed.): The “Event Reports USSR” 1941. Documents of the Einsatzgruppen in the Soviet Union. WBG, Darmstadt 2011, pp. 743-748, here p. 744.