terrorism

Under terrorism (from the Latin terror , fear ',' terror ') is defined as criminal acts of violence against people or property (such as murders , kidnappings , assassinations and bomb attacks) with which political, religious or ideological objectives are to be achieved. Terrorism is the practice and spread of terror . It serves as a means of pressure and is primarily intended to spread insecurity and horror or to generate or force sympathy and willingness to support. There is no generally accepted scientific definition of terrorism. The various legal definitions of the term, whether in national criminal law or international law , are often controversial for similar reasons.

Terrorists do not reach for space militarily (like the guerrillero ), but rather want to “occupy the mind” according to a classic formulation by Franz Wördemann and thereby force processes of change. Terrorism is not a military - but primarily a communication strategy.

People and groups who carry out attacks are often simply referred to by politics and the media as “terrorism”, for example in terms such as “international terrorism”. The term state terrorism denotes state-organized or sponsored acts of violence that are not always based on a legal basis or are assessed as terrorist.

term

The words terrorism , terrorist, and terrorize were first used in the 18th century to denote a violent government action. In connection with the French Revolution , the “ Terror of the Convention ” was proclaimed from 1793 to 1794, when the government executed or imprisoned anyone classified as counter-revolutionary . Among other things, Louis XVI. , Marie Antoinette and Countess Dubarry guillotined . In 1795 the term terrorism found its way into German usage. It is initially synonymous with the Jacobin reign of terror in France and was transferred to art and aesthetics from the 1820s.

Delimitations

It is difficult to objectively delimit the term terrorism, as it is often used by the ruling governments as legitimation, to denounce their opponents - sometimes regardless of whether they use violence or not - and to justify their own use of violence against supposed or actual enemies of the current state order is used. In particular, it is difficult to distinguish between criminal acts and legitimate acts of resistance.

Terrorism differs from resistance movements , guerrillas or national liberation movements less in the choice of its weapons than in the choice of its targets: A national liberation or resistance movement is mostly militarily extensive, while terrorism tries to attract the greatest possible attention with its acts of violence in order to to undermine closed power structures and to exemplify the vulnerability of such structures and to open them publicly to the population.

In terrorist organizations that have existed for a long time, commercialization (“violent entrepreneurship” according to Elwert ) often blurs the boundaries to organized crime (for example, the IRA and ETA partly financed themselves by extorting protection from local entrepreneurs.)

Definitions

There is no uniform definition of what can and cannot be termed terrorism, either in political practice or in research. In 2004, the United Nations Security Council drew up a definition that is binding under international law in Resolution 1566 , although it has not yet been widely recognized. The line between “ resistance fighter ” and “terrorist” is ideologically shaped and therefore often controversial. The sociologist Henner Hess finds the terminology a problem, since it would lie in the eye of the beholder. Whom some call terrorists, others can define them as “god warriors”, revolutionaries or freedom fighters. Richard Reeve Baxter , former judge at the International Court of Justice , said:

- We have reason to regret that a legal concept of terrorism was ever imposed on us . The term is imprecise; it is ambiguous; and above all, it serves no decisive legal purpose.

There is a different definition of terror for almost every state . In addition, different definitions of the individual authorities apply in the USA . The definition reflects the priorities and special interests of the respective authority. For example, the US State Department considers violent acts to be terrorist if they are directed against non-combatants , while the Department of Homeland Security speaks of terror when important infrastructure is attacked.

In 1988 there were already 109 different definitions of the word "terror" and this number is likely to have increased significantly after September 11, 2001 in particular. Some terrorism researchers differentiate between the terms "terrorism" and "terror". Accordingly, a violent method is understood as terror if it is used by a state, which is also known as state terrorism . This designation is not included in the other definitions, at least. In terrorism research, terrorism is understood as a violent method that is directed not least against civilians and civil institutions. The freedom or resistance fighter does indeed use physical violence, but in doing so he restricts himself primarily to military goals and thus intends to directly achieve the goals of his organization. In contrast, the terrorist is primarily concerned with the psychological consequences of the use of force. The violence of the terrorist is communicative and indirect, the terrorist can only reach his goal via detours. Its communication is directed to its victim, who can be a state and its apparatus, or civilians. The resistance or freedom fighter is primarily limited to military goals.

The discipline of terrorism research is more recent and has not yet produced a generally applicable scientific definition. The term was first used during the French Revolution, but in contrast to its negative connotation today, it had a positive connotation. For the so-called "regime de la terreur", also La Grande Terreur of the years 1793/94, from which both the English word "terrorism" and the German term are derived, terreur ( horror ) was regarded as an instrument to enforce order in the unrest and uprising anarchic period after the 1789 uprising. It aimed to cement the power of the new government by intimidating counter-revolutionaries and dissenters. One of the intellectual engines of the revolution, Maximilien de Robespierre , sums up his understanding of terror as follows: “Terror is nothing more than justice , immediate, unrelenting and indomitable justice; it is therefore a form of expression of virtue ”(Berhane 2011).

However, it was only when it was linked to the mass media that terrorism became a global politico-military strategy. According to Carsten Bockstette , terrorism can be defined as follows: Terrorism is the sustained and covertly operating struggle on all levels through the conscious generation of fear through serious violence or the threat of it, for the purpose of achieving one's own political goals. This is done with partial disregard for existing conventions of warfare. The aim is to achieve the highest possible publicity. So creating terror is an important part of the definition.

According to Bockstette, terrorism can be part of an asymmetrical conflict and wages a conflict with minor resources against a clearly superior power with violent means from the underground. Terrorist groups often claim that they are guerrillas and that they have to fight partisans with unconventional methods of using force because of their military inferiority. In comparison to partisans, however, terrorists are usually not able to withstand a direct military confrontation and avoid it, as they are inferior to the enemy in numbers and equipment. Unlike partisans, terrorists pay attention not to the physical, but rather to the psychological consequences of their attacks.

According to Pehlivan's extensive definition, terrorism is “[...] the creation of terror

- as a means of resistance ( ultima ratio ) through the long-term and centrally controlled union of more than two people

- to achieve a certain (political) goal, which is based either on a social revolutionary, nationalist or religious ideology or on a separatist motivation (secession autonomy)

- through the use of or with the threat of organized, continuous, repeated, asymmetrical, purposeful and planned, unpredictable and predictable, unexpected and criminal violence

- with an arbitrary , impersonal, symbolic and chaotic character

- against civil, military or neutral persons and objects

- using secret, military or technical methods

- using conventional, biological, nuclear, chemical or virtual weapons

- without any humanitarian or legal restriction

- at national, regional or global level.

Terrorism can be distinguished from terrorism, the reign of terror as a means of power (prima ratio) by states over their own people. "

The term has experienced a worldwide unique expansion since 2013 in Turkey. In May 2016, the Ankara-based think tank TARK determined that there were 11,000 prisoners in Turkey for political reasons, not least academics, journalists and other intellectuals, although it is a worldwide unique situation that Turkey is also convicted of terrorism could be if even indirectly no connection to political violence was accused. The term "unarmed terrorism" was invented for this by the AKP government and applied through the jurisprudence.

In April 2018, Facebook specified the criteria for the deletion of articles on its platform and for the first time presented the definition of terrorism on which the deletions are based: According to this, terrorist is "any non-governmental organization that engages in willful acts of violence against people or property, against a civilian population or a government or intimidate an international organization to achieve a political, religious or ideological goal ”.

Academic Approaches

"The [...] guerrilla tends to occupy the space in order to later capture the thinking, the terrorist occupying the thinking because he cannot take the space." Franz Wördemann's sentence is possibly the most comprehensive definition of terrorism. He differentiates terrorism from other violent conflicts such as interstate wars, guerrilla wars and war entrepreneurship. However, this does not rule out that actors in the latter conflicts also use terrorist means. According to the common view, terrorist actions are the use of force against civilian targets and non-combatants with the intention of spreading fear and horror and possibly to woo a third party for sympathy and malicious pleasure with the intention of undermining and overturning the existing system of rule.

Instead of an attempt to define the term terrorism per se, the moral dilemma already described will be illustrated using the example of the United Nations' handling of terrorism, which was also described by Hoffman in 2002:

- example

After the Munich Olympic assassination attempt at the 1972 Olympic Games , in the course of which eleven Israeli athletes were killed, the then UN Secretary-General suggested that the United Nations should become actively involved in the fight against terrorism. Various Arab , African and Asian member states contradicted this on the grounds that every liberation movement would inevitably be described by the oppressors as terrorism. But peoples who are oppressed and exploited have every right to defend themselves, including violence. Therefore, a decision to actively “fight against terrorism” would place the established structures above the non-established challenges and thus consolidate the status quo. Syria added that it was the moral and legal duty of the United Nations to support the struggle for liberation.

This debate resulted in a definitional paralysis of the United Nations, which has not yet been overcome. The communication of December 8, 2004 to the 59th General Assembly of the United Nations recommended tackling the outstanding definition of terrorism. However, this had already been recommended in previous communications, combined with a declaration on the fight against terrorism .

According to Kofi Annan's definition, terrorism is any act with the intention of causing death or serious physical injury to civilians and non-combatants with the aim of intimidating the population or forcing a government or international organization to do something to do or not to do. It is not necessary to discuss whether states can be guilty of terrorism or not, because the unrestricted use of armed force by a state against a civilian population is already clearly prohibited by international law.

Sometimes there are also voices promoting an ideologically and politically more neutral approach to the subject of terrorism.

Derivatives - Terrorist

A person or groups of persons who intend, announce, plan and carry out attacks and other terrorist actions or effects are referred to as a person or groups of persons. The assignment is typically made by the groups affected.

history

Terrorism is widespread worldwide and is a current, but by no means a new phenomenon (see Sicarians , Zealots , Assassins and the Young Italy movement around Giuseppe Mazzini ). The lists of known assassinations , explosives and terrorist attacks provide an overview . The modern form of terrorism developed in Europe in the saddle time around 1800 and is usually justified with an ideology that is directed against the attacked persons, groups of persons or the state and which cannot be enforced by peaceful means (see also fundamentalism and extremism ). In her study of the invention of terrorism, the historian Carola Dietze came to the conclusion in 2016 that the modern expression - with recourse to the American and French Revolutions - only became apparent with the assassination attempt by Felice Orsini on Napoleon III. 1858 and its transnational reception in Europe, Russia and the United States.

Terrorism expert David C. Rapoport has identified four waves of terrorism since the 19th century - anarchist , anti-colonial , neo-left and religious - that have been transnational media events from the start (while earlier terrorist activities such as that of the Ku -Klux-Klan remained regionally isolated): In the first, anarchists founded modern terrorism in the 1880s from the Russian tsarist empire, which lasted for about a generation . The following, partly overlapping waves were also global phenomena: From the 1920s the anti-colonial wave was dominant for about 40 years, from the 1960s the new left wave, which subsided at the end of the 20th century, and from the religious wave prevalent from 1979 onwards had been replaced. Significant examples of the new left wave are the Red Army Faction (RAF), the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Brigate Rosse (BR) and the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA).

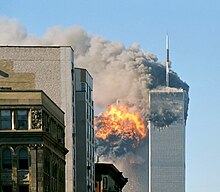

After September 11, 2001 , the US government's " war on terrorism " led to the terrorization of the civilian population (for example in Pakistan) and to a new dimension of terrorism through deliberately planned suicide attacks by Islamists, particularly through the terror network Al- Al-Qaida . Its members cited a historical background that goes back to the time of the Crusades. Marked Osama bin Laden , the peoples of the West as " Crusaders " and called on the Muslims of the East a "war of religions" to support the Muslim community in the West. The historical reference point is the Islamic religious community of the Ismailis , a splinter group of the Shiites , which, however, is incompatible with their theological and philosophical traditions.

Targets and terrorist calculation

The terrorists' aim is to draw attention to their political, moral or religious concerns and to force them to be heeded. The terrorist calculation is characterized by a sequence of three:

- The (planned) act of violence aims at destabilizing the attacked person, which is to be achieved through factual evidence of his vulnerability.

- The intention is to use fear and horror to disrupt the previous functionality of the conditions under attack, that is, to damage their processes and weaken their coherence.

- To generate reactions of the attacked through which the actual goals of terrorism can be achieved.

Retaliatory measures generate (in the best case) sympathy and willingness to support the target group. The terrorists hope that the system will be “unmasked” or “exposed”. If, through increasing support, it is possible to switch to open guerrilla warfare, then the terrorist calculation has paid off.

The fear that has arisen in the population as a result of attacks tends to increase the belief that the government cannot protect the citizens of the country. The power of the government is thus weakened from “within”. That the state is taking countermeasures was z. E.g. the German RAF actually intended: The state reactions should induce the citizens to rebel against the state and its rulers .

Characteristics of terrorism: strategy and approach

Terrorism is a violent strategy of non-state and state actors who use it to achieve political, ideological, but also religious and even business goals. In terms of the cost-result ratio, terrorism can also be a very efficient form of warfare. Without much effort and equipment, very great damage can be done and a great impression can be made.

The strategy of terrorism is primarily based on psychological effects. The target group affected should be shocked and intimidated, for example the war should be carried into the supposedly safe “hinterland” of the enemy. By spreading uncertainty and confusion, the resistance against the terrorists is to be paralyzed.

In fact, all terrorist organizations share certain basic features, for example a relatively weak position vis-à-vis the attacked power apparatus. The violence is often directed against targets with a high symbolic content (e.g. religious places, government buildings) in order to humiliate and provoke the opponent, but increasingly also against so-called soft targets, i.e. places in public life that are difficult to protect (e.g. public transport, restaurants). There are also hostages and kidnappings . a. also official representative of the "opponent". Typically, the victims of acts of terrorism in the conflict are completely uninvolved (women and children, citizens of states not involved in the conflict).

The impact of terrorist activities can be increased by reporting in the mass media ; some terrorists use this effect deliberately, for example by distributing execution videos of kidnap victims.

Another goal of terrorist activities is the mobilization of sympathizers and the radicalization of politically related movements. Terrorists see themselves as liberators of the "oppressed".

The mobilization of supporters is often achieved primarily through the counter-reactions of the "opponent" to attacks. If he can be provoked into disproportionate, brutal measures, this should "de-legitimize" him (e.g. restriction of the rights of freedom through curfews ). In this way, terrorists can change into the role of the attacked.

In recent times, terrorists' strategy of violence has also been aimed at generating economic effects. By attacking targets of economic importance that are difficult to protect (e.g. attacks on oil production facilities or tourist centers), the economy and the governments of the "opponents" are intended to be destabilized and their own political ideologies to be enforced.

An important characteristic of terrorist groups is that they mostly operate as terrorist cells tactically completely independently of one another. Each terrorist cell decides autonomously when and where to take the initiative. As a result, terrorists cannot be attacked as clearly identifiable and delimitable combat units (see counter-terrorism ).

Terrorist groups often also engage in criminal activities that are not primarily politically motivated but, for example, serve to raise funds. Therefore, they (such as ETA or the PKK ) often inevitably have a connection to organized crime.

Types of terrorism

Two ways of subdividing terrorism seem sensible. On the one hand according to the spatial extent, on the other hand according to motivation and goal setting. According to the spatial extent, three types of terrorism can be distinguished:

- National terrorism is limited in terms of objectives and scope of action to the territory of a state. Examples of this are the Maoist movements in Nepal , Bhutan , Bangladesh , Indonesia and the Philippines or the RAF in the Federal Republic of Germany .

- International terrorism has internal goals, but the scope of action extends beyond the borders of the country and uninvolved third parties are made victims. An example of this is the Filipino Abu Sajaf .

- Transnational terrorism has large parts of the world in its sights and aims to change the international (economic or domination) order. The terrorist networks Al-Qaeda and Islamic State are the only associations to which this applies.

If one takes motivation and objective as a basis, the following main forms of terrorism can be identified:

Social revolutionary terrorism, left-wing terrorism

The politically left-wing , social revolutionary terrorism, also known as left- wing terrorism , has its intellectual origin in the propaganda of the deed of the 19th century, which did not target the civilian population.

In the context of the " New Left " in West Germany in the early 1970s, a new form of left-wing terrorism emerged, characterized by the rejection of the Federal Republic. Left-wing terrorism had its best-known offshoots in the RAF and in the Italian Red Brigades with regard to the publicity of their attacks. The attacks were aimed at the revolutionary overturning of existing social domination and property relations in the affected country, sometimes also at the attempt to unleash a revolutionary civil war . However, they met with great general opposition in Germany. In the countries of the western world, such movements consistently failed and completely lost their importance with the fall of the Iron Curtain . In Latin America it was the origin of today's guerrilla groups such as the FARC or the ELN . There is currently this Marxist- inspired terrorism in the form of “ Maoist movements” in some countries in South and Southeast Asia .

Right-wing terrorism

Right-wing terrorist activities are mostly based on racist and ethnic beliefs. The largest number of deaths from terrorist activities is recorded in Germany from right-wing terrorism. Right-wing terrorist activities in Germany started with the murder of Kurt Eisner in 1919. In the Weimar Republic, right-wing extremists committed up to 400 " political assassinations ", among the victims of the mostly in volunteer corps organized perpetrators were mainly politicians from the Social Democrats and Communists . When the National Socialists came to power in 1933 , right-wing terrorism became state policy. For the first two decades of the Federal Republic of Germany , no right-wing terrorist activities can be proven. At the end of the 1960s a violent neo-Nazi underground formed and in 1968 the group around Bernd Hengst shot at the DKP's office . The most famous attack by the military sports group Hoffmann was the bomb attack on the Munich Oktoberfest with 12 dead. German action groups under Manfred Roeder committed seven attacks with two dead. In the 1980s and 1990s, the focus of right-wing terrorist activities shifted from political opponents to racist attacks such as the Mölln assassination attempt and the Solingen assassination attempt and the series of murders and attacks by the National Socialist Underground . In addition to the organized groups, individual perpetrators such as Kay Diesner acted . Several attacks such as the one on the Munich synagogue by the Action Office South could be uncovered in advance. Similar activities can be traced across Europe, with the 2011 attacks in Norway causing the greatest number of fatalities . In the United States the right-wing terrorism is also based on religion and explained by apocalyptic eschatology and the fight against the satanic identified individuals and groups and has overlap with the Militia - and abortion opponents milieu on. In the USA, right-wing extremist terrorism can be traced back to the 19th century with the Ku Klux Klan . Well-received recent incidents include Ruby Ridge and Branch Davidians, as well as the bomb attack on the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City .

(Ethnic) nationalist terrorism

The nationalist and ethnic-nationalist terrorism is the struggle of a people or an ethnic minority with the aim of increased autonomy or the establishment of an independent state, citing "historically evolved special features". The politics of this form of terrorism include the tradition of conflict and violent self-help.

Examples: The ETA (Basques), ASALA (Armenians), the PKK (Kurds), the IRA , UVF and UDA (all three Northern Irish) in Europe and the Middle East.

Religious Terrorism

The expression “religious terrorism” meets with great opposition, both from the representatives of the religions themselves and from outsiders, who often do not attribute any terrorist potential to religion itself. Historically, however, it has been shown that actions that can be classified as terrorist often take place in a religious context, but so differently and spatially in terms of time and space that the possibility of a definition is repeatedly questioned.

A consideration of religious terrorism focuses on the motive by which religious people are moved to terrorist acts. The main characteristic of religious terrorism is therefore the personal convictions of the perpetrators. In the 19th century, the philosopher Jakob Friedrich Fries created a theoretical basis not only for religious assassins. According to Bruce Hoffman , violence for the religious terrorist is "first and foremost a sacramental act or a divinely ordained duty".

Religious terrorism has gained in importance, especially since the mid-1980s. It emerges from sects or fundamentalist currents within certain religions. In particular, radical Islamic organizations such as the Palestinian Hamas , the Lebanese Hezbollah and, last but not least, the terror networks Al-Qaeda and Islamic State are well-known examples of Islamist-motivated terrorism . A well-known Christian terrorist organization is the Lord's Resistance Army .

Material and spiritual motives are given as reasons for Islamist terror. The economist Muhammad Yunus says: “Take the Islamists: They give the poor something to eat, as well as weapons and an ideology. There is no doubt that poverty is the breeding ground for terrorism. ”However, some Islamist terrorists such as Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab come from the educated upper class , so that poverty can be seen as a factor, but not the sole cause.

Homegrown Terrorism

Homegrown Terrorism ("homemade terrorism") originally referred to terror that emanates from people who grew up inconspicuously in the target country of the terror and only there came to their terrorist convictions. The term is mainly used in the Anglophone-speaking area for Islamist terror of recent times.

It was used to describe, for example, the terrorist attacks on July 7, 2005 in London , where a total of four explosions in three underground trains and one bus killed 56 people and injured more than 700. Most of the Pakistani perpetrators were born in Great Britain, came from secular families and were integrated into community life before they joined Islamist organizations and terrorized their own country. The term was introduced because previous Islamist terrorist attacks in Western countries were mainly carried out by people who came here for this purpose. Regardless of this, until the 1980s, terror in Europe came primarily from people who came from the respective target country, such as the Red Army faction in the Federal Republic of Germany or the Action directe (AD) in France .

Since the beginning of the 21st century, security circles in Germany have referred to homemade terrorism as a type of Islamist terrorism whose actors no longer traditionally come from Islamic countries or are descendants of Islamic immigrants. Rather, the “new” home-made terrorism is recruited from native German nationals, especially young people who have converted to Islam and got caught up in Islamism. They are trained in special training camps in Islamic countries and equipped with the technical and ideological prerequisites for carrying out terrorist actions.

The German Federal Minister of the Interior Wolfgang Schäuble characterized the three members of the Islamic Jihad Union , two of whom were Germans who had converted to Islam, who were caught by German investigators on September 5, 2007, as a typical example of homemade terrorism .

The former President of the Federal Criminal Police Office Jörg Ziercke sees Germany no longer just as a quiet room, but also as a target of international terrorism.

Conservative “vigilantist” terrorism

In contrast to other forms of terrorism, conservatively motivated “ vigilantist terrorism” does not aim at weakening but rather at strengthening the existing state order, albeit by breaking the laws on which this order is based through vigilante justice . The racist Ku Klux Klan in the USA and paramilitary groups in Latin America and Northern Ireland can be described as vigilantist terrorism, as well as - according to the sociologist Matthias Quent - the right-wing terrorist National Socialist underground in Germany.

Terrorism due to violated legal feeling

Even in states with an established legal system, terror was occasionally a response from those who were actually or allegedly injured in their rights to the stronger. One example is the bloody feud of the businessman Hans Kohlhase against the Elector of Saxony , which Kleist used in the novella Michael Kohlhaas . Gerhard Gönner describes this form of terror as the "answer to the injured and absolutized righteousness". It results from an actually passive attitude towards the world, which leads to a build-up of aggression in constant fear of injury. This could lead to terrorist outbreaks in the face of an unpunished legal violation.

State terrorism

State terrorism denotes acts of violence that are classified as terrorist and are carried out by state organs or at least informally by actors controlled by a state (e.g. death squads or underground movements ) or promoted by a sovereign government. In the recent past, for example, cases have been documented in which states or their secret services initiated acts of terror under “ false flags ”, which were then foisted on undesirable political groups in order to discredit them.

State terror

In terms of the philosophy of the state , state terror describes the targeted use of the citizens' fear of the state's monopoly of force as a means of coercion to force its citizens to abide by the law. The term was most prominently coined by the liberalism of Hobbesian contractualism in his work Leviathan . For Hobbes, terror gave the state ( terror of legal punishment ) the necessary and legal means of coercion to establish its constitution.

In the theory of totalitarianism , state terror, for example through control and monitoring and the renunciation of the rule of law , is a central characteristic of totalitarian states. In particular, there is talk of state terror when a totalitarian system forcibly gets rid of its opponents: The most prominent examples of such state terror in the 20th century are the domestic political suppression of alleged opposition members during the Nazi dictatorship in Germany as well as under the reign of Josef Stalin in the Soviet Union , there in particular the so-called Stalin Purges , also referred to as the " Great Terror ". The use of the term is not clear in other historical events, for example the kidnapping and murder of up to 30,000 people by the Argentine military dictatorship from 1976 onwards, depending on the source, is referred to as both state terrorism and state terrorism.

Ecoterrorism

The term refers to acts (explicitly including criminal acts) that have a political dimension (terrorism) and are related to the environment (ecology). According to different understandings, it is called

- either acts of violence aimed at protecting the environment

- or acts with considerable damage to the environment (see for example agroterrorism ).

Bioterrorism

The use of biological agents by terrorists as bioterrorism referred.

Crime-Terror Nexus

Since the attacks of September 11, 2001 in particular , terrorism has been analytically linked to organized crime . Terrorist organizations, however, generate financial resources in order to pursue political goals, and economic goals do not come first, as is the case with organized crime, but serve as a means for an overarching end. The structures also differ in their modus operandi - while in organized crime the focus is primarily on feeding illegally generated funds into the legal circulation of money (e.g. through money laundering), terrorist organizations are more interested in their finances (whether legally, e.g. in the form of donations, or acquired illegally) within their terrorist networks. However, terrorist organizations also generate finance illegally, e.g. B. hostage-taking, extortion, robbery, goods and people smuggling and drug trafficking . This link between criminal activity and politically motivated terrorist violence is often referred to as the “nexus” of organized crime and terrorism.

The best-known historical crime-terror alliances existed between the international drug trade and terrorist organizations, such as the Colombian Medellin-Cocaine cartel , which in 1993 commissioned the Marxist-oriented guerrilla group ELN ( Ejército de Liberación Nacional ) to plant car bombs against the government . The cooperation between the left-wing revolutionary Colombian FARC ( Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia ) and Mexican drug cartels was also notorious . Other well-known cases are Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb , which secured a financial basis both through extortionate hostage-taking and by taking over the smuggling of cocaine and synthetic drugs between Spain and Algeria, or Mokhtar Belmokhtar , who belongs to al-Qaida and who is known as “Marlboro Man “became known for his smuggling activities (cigarettes and drugs).

The IS, strengthened by the wars in Iraq and Syria, finally controlled a territory for a long time, on which it was able to exploit not only natural resources, but the entire infrastructure, and thus advanced to probably the most financially strongest terrorist organization to date, which also controlled illegal financial income ( Hostage-taking, money laundering, etc.). In its heyday, the IS was considered the financially strongest terrorist organization worldwide, with a "war chest" of around 500 million dollars after several successful bank robberies in northern Iraq and the development of the opportunity to secure several main sources of income through oil revenues and taxation measures in occupied territories.

In Europe, however, the situation was different - mainly due to the rigid anti-terrorist measures that have been taken since 2001. Jihadist groups in Europe felt compelled to finance the implementation of their plans themselves, to secure themselves financially and logistically and to organize their operations on their own. More and more criminal networks were used for this purpose. The devastating attacks in Europe by members of the “ Islamic State ” (IS), in Paris in 2015 and in Brussels and Berlin in 2016 , were in part carried out by individuals with a criminal history. Before turning to jihadism , they were involved in criminal activities such as petty crime, organized crime or illicit trafficking . This finding is also confirmed by German security authorities and international research associations, whose analyzes of the biographical background of German emigrants from Syria and Iraq show that two thirds of those who emigrated from Germany were around jihadist-motivated organizations such as IS or the local Al Qaeda offshoots of the al-Nusra Front, to join, had already caught criminals before they left. For the European scene, the modus operandi of IS, using small cells to carry out attacks outside of war zones, can be implemented particularly well with a model of locally generated criminal, often petty criminal financing. With the new recruitment pool, the type of attacks is also changing. Logistically and organizationally complex attacks are no longer in the foreground, but so-called "low cost" attacks, as they have spread fear and horror in Europe with little effort in recent years. 90% of the jihadist-motivated "plots" in Europe were self-financed and comparatively inexpensive, and security authorities assume that the financing of terrorist activities via criminal offenses will increase.

Domestic political consequences

Democracy can be defined as “rule by the people”. This includes a responsible government that must respond to the interests of the people and that is dependent on the people. The people have the power to vote out the government in elections. The electorate thus largely determines the direction of politics. If terrorist organizations (especially in the period before elections) influence the preferences of the electorate, this can influence the domestic politics of a state directly or indirectly and / or affect the outcome of the election.

The effect of terrorism on the preferences of the electorate can be illustrated using the Middle East conflict as an example . Looking at the time of the conflict, the political orientation of individual areas shows that terrorist incidents in right-wing districts increase the support of right-wing parties. In left-wing areas, on the other hand, support for right-wing parties declines if the attacks occurred outside of the respective district. Terrorist activities thus polarize the electorate. These results mainly relate to ongoing domestic terrorism. On the other hand, there is the influence of transnational terrorism. The Spanish parliamentary elections shortly after the train attacks in Madrid offer a glimpse here. The attacks mobilized citizens who usually do not participate, including younger or less educated citizens. In addition, voters from the center and the left were mobilized and some switched to the opposition. Last but not least, the attacks influenced citizens' voting decisions. The mismanagement of the conservative Partido Popular (PP) party and its foreign policy in Iraq and Afghanistan has demonstrably influenced the preferences of the Spanish electorate; the PP lost votes in the elections shortly after the attacks and had to join the opposition. If terrorist attacks take place shortly before parliamentary elections, this triggers an evaluation of the political results of the ruling parties so far on the part of the opposition and the media. Terrorism thus helps mobilize the electorate.

In addition to the direct influence of terrorism on voter preferences, terrorist attacks also affect the formation of coalitions within representative democracies. As a result, coalitions that can withstand external shocks are more likely to form. In view of terrorist threats, it is therefore more likely that oversized coalitions are formed , as it is assumed that politicians want to avoid government instability through oversized coalitions during this period. In addition, external threats lead to ideologically homogeneous coalitions, since an internal consensus tends to lead to stability. This effect arises in particular in the case of transnational terrorist attacks, since parties already take political positions with regard to domestic terrorism and coalition options are therefore restricted in any case. Transnational terrorism therefore promotes oversized, ideologically homogeneous governments, as they can allegedly take action more consistently against external threats.

Another problem is the ban on terrorist parties, as this is in conflict with the right of citizens within a democracy to run competitive elections. So if political parties are banned, the fundamental principles of representation and equality are ignored - a democratic paradox arises (cf. controversial democracy). Nonetheless, in some post-communist countries and in numerous African and Indian constitutions, it is possible to ban parties. In Israel and Germany there is also the possibility of banning a party with a so-called party ban because it supports or encourages acts of terrorism or armed conflict against the state. Terrorism thus influences the legitimacy principle of representative governments.

In summary, it can be assumed that democracies increase the risk of terrorist attacks: The electorate, but also the government of a state react to terrorist attacks, which gives terrorists the opportunity to influence the domestic politics of a state. However, this link is not clear, as the responsiveness of democratic systems could lead to a moderation of extremist groups and also reduce the usefulness of terrorist activities. The relationship between democracies and terrorism cannot therefore be clearly worked out, even taking into account the political consequences.

Counter-Terrorism

Essentially, one can distinguish between two approaches: Combating terrorism

- through actual fighting and the use of force (operational measures) or

- through measures that serve to combat the political, ideological or economic causes ('structural measures').

In addition, there are monitoring measures - in particular

- electronic communication

- and various financial flows , as well

- the structure of anti-terrorism files .

In the meantime, however, there is a growing skepticism about excessive wiretapping and surveillance, especially since Edward Snowden's revelations about the NSA . In the European media, the term “terror paranoia ” was coined in this regard , which is primarily associated with the USA.

See also Counter Terrorism in Israel

Fighting terrorism as a state proclaimed war target:

The war on terrorism is a political slogan used by the US administration under George W. Bush that summarizes a range of political, military and legal steps against the international terrorism identified as a problem.

Terrorist groups

A 'terrorist organization' (German legal term since 1976) or 'terrorist organization' (United Nations) is a long-term organization of several people (terrorists), the aim of which is to use actions that are assessed as criminal offenses under the rule of law , above all to achieve political goals. These goals can be accompanied by other (for example religious or economic) motives. Terrorist organizations try to use violence to bring horror (Latin: terror ) into a country in order to achieve their goals.

Criminal law

The criminal offense "formation of terrorist organizations" set out under ( § 129a ) StGB was included in the StGB in 1976 in the course of the fight against terrorism and introduced the term " terrorist organization " as a legal term . 129a StGB is part of a bundle of laws that critics call Lex RAF , which was passed (= introduced) with special reference to the Red Army Faction (RAF) .

The list of terrorist organizations overseas designated by the United States Department of State is used by many states as a legal basis for law enforcement.

Casualty numbers

Worldwide

The Global Terrorism Database (GTD) comprises systematic data on domestic and international terrorist events from 1970 to 2017 and contains more than 180,000 cases from this period.

According to the US National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), a total of 12,500 people died in 2011 from terrorist attacks. The Global Terrorism Index of the Institute for Economy & Peace examines the number of victims, most affected countries etc. every year. For example, in 2013 over 80% of the victims died in one of the following five countries: Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria. 66% of the attacks were carried out by one of the following terrorist groups (or their partners): Islamic State , Boko Haram , the Taliban and al-Qaeda .

For example, in 2014, 78% were killed in one of the five countries Iraq, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Syria. Boko Haram killed 6,644, ISIL 6073, the Taliban 3,310 and Islamists from the Fulbe people 1,229.

According to data from the Institute for Economics and Peace :

| year | Dead from terrorism | thereof in Europe |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 3,329 | |

| 2012 | 11,133 | |

| 2013 | 17,958 or 18,111 |

244 |

| 2014 | 32,685 | 31 |

| 2015 | 29,376 | 487 |

| 2016 | 25,673 | 827 |

| 2017 | 18,814 | 204 |

| 2018 | 15,952 | 62 |

Germany and Europe

Two very detailed studies of the Northern Ireland conflict from 1969 to 1998, the University of Ulster's CAIN project and Lost Lives, calculated around 1,800 deaths.

Between 1970 and 1998 34 people were murdered in attacks by the RAF . According to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (Global Terrorism Database of the University of Maryland, USA), 675 people died in Europe from 2000 to 2015.

Relative probability

The population generally overestimates the risk of a terrorist attack in western countries. Terrorist attacks are extremely rare events, but they are highlighted disproportionately in media coverage. In Germany (as of spring 2016) it is about 1.13 times more likely to be struck by lightning than a victim of an Islamist terrorist attack, and the probability of dying from flu is 3797 times higher.

List of terrorist attacks

literature

- Mark Juergensmeyer : Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. 4th edition. University of California Press, Berkeley 2017, ISBN 978-0-520-29135-5 .

- Florian Peil: Terrorism - how we can protect ourselves. Murmann, Hamburg 2016.

- Christine Hikel, Sylvia Schraut (ed.): Terrorism and gender. Political violence in Europe since the 19th century (= history and gender . Volume 61 ). Campus , Frankfurt a. M./New York 2012, ISBN 978-3-593-39635-4 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- David J. Whittaker (Ed.): The Terrorism Reader. 4th edition. Routledge, Abingdon 2012, ISBN 978-0-415-68731-7 (review) .

- Peter Waldmann : Terrorism. Provocation of power. Gerling-Akademie-Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 978-3-932425-09-7 ; Murmann Verlag, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 3-938017-17-1 .

- Dipak K. Gupta: Understanding Terrorism and Political Violence. Routledge, London, New York 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-77164-1 .

- Tobias O. Keber : The concept of terrorism in international law. Lines of development in contract and customary law with special consideration of the work on a comprehensive convention to combat terrorism (= public and international law. Volume 10). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-58240-4 .

- Philipp H. Schulte: Terrorism and anti-terrorism legislation - a legal sociological analysis. Waxmann, Münster 2008, ISBN 978-3-8309-1982-7 .

- Alexander Straßner (ed.): Social revolutionary terrorism. Theory, ideology, case studies, future scenarios. Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15578-4 .

- Eric Hobsbawm : Globalization, Democracy and Terrorism. DTV, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-423-24769-6 (collection of articles, English original 2007).

- Peter Waldmann , Stefan Malthaner: Terrorism. In: Dieter Nohlen , Florian Grotz (Hrsg.): Small Lexicon of Politics . 4th, updated and expanded edition. Beck, Munich 2007, pp. 573-578.

- Wilhelm Dietl , Kai Hirschmann, Rolf Tophoven : The Terrorism Lexicon - perpetrators, victims, backgrounds. Frankfurt am Main 2006.

- Institute for Security Policy (Ed.): Yearbook Terrorism. Opladen, Farmington Hills, MI 2006 ff.

- Ben Saul: Defining Terrorism in International Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York 2006.

- Johann Ulrich Schlegel, Terror and Freedom, Reaction, Philosophy and the Returned Religion, Baden-Baden 2016

- Ulrich Schneckener : Transnational Terrorism. Character and background of the "new" terrorism. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 978-3-518-12374-4 .

- Charles Townshend : Terrorism. A short introduction (= Reclams Universal Library . Volume 18301). Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-018301-4 .

- Paul Berman: Terror and Liberalism. Federal Agency for Political Education, Bonn 2004 (licensed edition of the European publishing company), ISBN 3-89331-548-9 .

- Josef Isensee (ed.): Terror, the state and the law. Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-428-11127-3 .

- Walter Laqueur : War on the West. Terrorism in the 21st Century. Propylaea, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-549-07173-6 .

- Sean K. Anderson, Stephen Sloan (Eds.): Historical Dictionary of Terrorism. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD 2002.

- Bruce Hoffman: Terrorism - The Undeclared War. New dangers of political violence. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-596-15614-9 .

- Martha Crenshaw, John Pimlott (Eds.): Encyclopedia of World Terrorism. Three volumes. Sharpe, Armonk 1997.

Web links

- Terrorism. In: From Politics and Contemporary History , Edition B51 / 2001.

- Robert Goehlert (responsible), Kira Homo, Christina Jones, John Russell: Terrorism. A Guide to Selected Resources. Indiana University , Bloomington 2004 (PDF) .

- Igor Primoratz: Terrorism. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . , October 22, 2007 (English).

- United States Department of State : Country Reports on Terrorism (English, "Country Reports on Terrorism").

Individual evidence

- ^ Definition according to Peter Waldmann : Terrorism and civil war. The state in distress. Gerling Academy, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-932425-57-X .

- ^ Franz Wördemann : Terrorism. Motives, perpetrators, strategies. Piper, Munich, Zurich 1977, p. 53; Andreas Elter : The definition of terrorism. In: Dossier: The History of the RAF. Federal Agency for Civic Education , August 20, 2007.

- ↑ a b c Bockstette, Carsten: "Terrorism and asymmetrical warfare as a communicative challenge". In: Carsten Bockstette, Siegfried Quandt, Walter Jertz (eds.) (2006) Strategic Information and Communication Management. Manual of Security Policy Communication and Media Relations ; Bernard & Graefe Publishing House.

- ↑ Charles Tilly: "Terror, Terrorism, Terrorists." In: Sociological Theory 22 (1): 5-14, p. 8, 2004.

- ↑ See Marsavelski, A. (2013) The Crime of Terrorism and the Right of Revolution in International Law Connecticut Journal of International law, Vol. 28, pp. 278–275.

- ↑ See Sociology of Crime: theoretical and empirical perspectives (2002), p. 98.

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman: Terrorism - The Unexplained War, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 3-10-033010-2 , pp. 21-80.

- ↑ bpb : The Definition of Terrorism , accessed on November 22, 2011.

- ↑ cf. Adam Roberts: The 'War on Terror' in Historical Perspective , in: Thomas G. Mahnken and Joseph A. Maiolo: Strategic Studies - A Reader , Oxon: Routledge 2007, 398.

- ↑ Original wording : “We have cause to regret that a legal concept of terrorism was ever inflicted upon us. The term is imprecise; it is ambiguous; and, above all, it serves no operational legal purpose. ” Quoted from University of New South Wales : What is 'terrorism'? Problems of legal definition , 2004.

- ^ University of Oklahoma : International Law: Blaming Big Brother: Holding States Accountable for the Devastation of Terrorism ( Memento January 14, 2009 in the Internet Archive ), 2003.

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman: Terrorism - The Unexplained War, Frankfurt 2006, ISBN 3-10-033010-2 , p. 68 f.

- ↑ See University of New South Wales : What is 'terrorism'? Problems of legal definition ( memento of August 19, 2006 in the Internet Archive ), 2004.

- ↑ E. Pehlivan: Improving police cooperation between the EU and Turkey through Europeanization of internal security: an investigation using the example of the fight against terrorism. Duisburg. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-280226 . 2009.

- ↑ See Peter Waldmann: Terrorism. Provocation of power. Munich 1998, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Abuse Of Anti-Terror Law Is Destroying Turkey's Democracy. Institute of Social and Political Researches (TARK), Ankara, May 10, 2016, archived from the original on May 17, 2016 ; accessed on May 17, 2016 .

- ↑ WORLD: Extremist Posts: Facebook now has its own definition for terrorism . In: THE WORLD . April 24, 2018 ( welt.de [accessed May 4, 2018]).

- ^ Franz Wördemann with the assistance of Hans-Joachim Löser: Terrorism. Motives, perpetrators, strategies. Munich u. Zurich: Piper 1977. p. 57.

- ↑ Five Points Against Terrorism - Kofi Annan on Terrorism. In: ag-friedensforschung.de. March 11, 2005, accessed February 28, 2015 .

- ↑ Steffen Roth, Jens Aderhold: World Society on the Couch: Anti ‐ Terror Consultancy as an Object and Test ‐ Bed of Professional Sociology. In: HUMSEC Journal. Volume 1, Number 2, 2008, pp. 67-82.

- ↑ See also wiktionary .

- ↑ Thoroughly reflective on the term and with further references to the literature Thomas Marzahn: Feindstrafrecht as a component of the prevention state? (= Contributions to criminal law studies. Papersbacks. Vol. 6). Lit, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-10704-6 , pp. 29-32.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: Metternich. Statesman between restoration and modernity. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58784-9 , p. 66 f.

- ↑ Carola Dietze : The Invention of Terrorism in Europe, Russia and the USA 1858–1866. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-86854-299-8 (based on the habilitation thesis). Review by Armin Pfahl-Traughber , review by Peter Eisenmann .

- ^ David C. Rapoport: The Four Waves of Modern Terrorism. In: Audrey Kurth Cronin, James M. Ludes (Eds.): Attacking Terrorism. Elements of a Grand Strategy. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC 2004, pp. 46–73, here p. 46 f. (PDF) .

- ^ Stanford Law School: Living Under Drones: Death, Injury and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan. Retrieved May 9, 2019 .

- ^ Glenn Greenwald: New Stanford / NYU study documents the civilian terror from Obama's drones | Glenn Greenwald . In: The Guardian . September 25, 2012, ISSN 0261-3077 ( theguardian.com [accessed May 9, 2019]).

- ↑ Bigalke Abou-Taam (ed.): The speeches of Osama bin Laden. 2006, p. 111 f.

- ↑ Sebastian Simmert: Terrorism under the sign of false traditions. About the incompatibility of Ismaili ideology with acts of terrorism. In: Journal of Legal Philosophy. Issue 2, 2013, pp. 3–17, here p. 16 f.

- ↑ Brent Smith: A Look at Terrorist Behavior: How They Prepare, Where They Strike , NIJ Journal, Vol. 260, July 2008.

- ↑ Nohlen 2001, pp. 514-518 (names nine).

- ↑ Calling for V-people is pure actionism ( memento of November 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Financial Times Deutschland, November 16, 2011.

- ^ Right- wing terrorism - It began in 1919 by Sven Felix Kellerhoff in Welt online, November 14, 2011.

- ↑ Right Wing Terrorism and Weapons of Mass Destruction (pdf; 91 kB) by Paul de Armond, 1999, on the Public Good Project website, accessed November 16, 2011.

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman: Terrorism - The Undeclared War. New dangers of political violence. Fischer Taschenbuch, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-596-15614-9 , p. 122.

- ↑ Hasnain Kazim : Economist Muhammad Yunus: "People are not money machines". In: Spiegel Online , May 8, 2007.

- ↑ Detroit bombers - rich parents, radical minds. In: Die Welt , December 27, 2009.

- ↑ Investigators are looking for backers (tagesschau.de archive)

- ↑ For the definition and cause of aggression congestion cf. [1]

- ↑ Gerhard Gönner: About the “split heart” and the “fragile institution of the world”. Attempt at a phenomenology of violence in Kleist. Stuttgart 1989, p. 175.

- ↑ Thomas Lange / Gerd Steffens: The National Socialism Volume 1: State Terror and Volksgemeinschaft 1933-1939 . Wochenschau Verlag , Schwalbach 2013, ISBN 3-89974-399-7 .

- ↑ Michael Riekenberg : Small history of Argentina. CH Beck , 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Josef Oehrlein : Certainty after decades. FAZ, July 31, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Tamara Makarenko: Europe's Crime-Terror Nexus: Links Between Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the European Union . Ed .: European Parliament: Directorate-General for Internal Policies. No. 20 . Brussels Brussels.

- ^ A b c Colin P. Clarke: Drugs & Thugs: Funding Terrorism through Narcotics Trafficking . In: “Journal of Strategic Security. Special Issue: Emerging Threats . No. 2016: 1-15 .

- ↑ Magnus Ranstorp: Microfinancing the Caliphate: How the Islamic State is Unlocking the Assets of European Recruits . Ed .: CTC Senitel. May 25, 2016.

- ↑ Matenia Sirseloudi: Double Trouble: petty crime, organized crime and terrorism . Ed .: Violence Prevention Network. tape 13 . Berlin ( violence-prevention-network.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Kacper Rekawek et al .: From Criminals to Terrorists and back? Ed .: Globsec. Bratislava ( globsec.org [PDF]).

- ^ Colin P. Clarke: Crime and Terror in Europe: Where the Nexus Is Alive and Well . Ed .: Rand Corporation. 2016.

- ↑ Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (BfV), Hessian Information and Competence Center against Extremism (HKE): Analysis of the background and course of radicalization of people who traveled from Germany to Syria or Iraq for Islamist motivation. 2016, accessed May 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Matenia Sirseloudi: From Criminals to Terrorists and Back. The German Case. Report I and II . Ed .: Globsec. Bratislava ( globsec.org [PDF]).

- ↑ Hazim Fouad: Quo vadis Jihadis? Current dynamics in the field of jihadist radicalization in Germany . In: Sabrina Ellebrecht, Stefan Kaufmann, Peter Zoche (ed.): (In-) certainties in change. Social dimensions of security . Lit-Verlag, Münster 2018.

- ^ Claude Berrebi and Esteban F. Klor (2006): On Terrorism and Electoral Outcomes: Theory and Evidence from the Israeli-Palestinan Conflict. In: The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 50/6, pp. 899-925.

- ↑ Claude Berrebi and Esteban F. Klor (2008): Are Voters Sensitive to Terrorism? Direct Evidence from the Israeli Electorate. In: American Political Science Review. 102/3, pp. 279-301.

- ↑ Valentina A. Bali (2007): Terror and Elections: Lessons from Spain. Electoral Studies 26/3, pp. 669-687.

- ↑ Indridi H. Indridason (2008): Does Terrorism influence Domestic Politics? Coalition Formation and Terrorist Incidents. In: Journal of Peace Research. 45/2, pp. 241-259.

- ↑ Sozie Navat (2008): Fighting Terrorism in the Political Arena: The Banning of Political Parties. Party Politics. 14/6, pp. 745-762.

- ↑ Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, Mogens K. Justesen and Robert Klemmensen (2006): The political economy of freedom, democracy, and transnational terrorism. In: Public Choice. 128, pp. 289-315.

- ↑ Sarah Jackson Wade and Dan Reiter (2006): Does Democracy Matter? Regime Type and Suicide Terrorism. In: Journal of Conflict Resolution. 51/2, pp. 329-348.

- ^ Seth G. Jones , Martin C. Libicki, How Terrorist Groups End. Lessons for Countering al Qa'ida (free PDF), Rand Corporation , July 2008, ISBN 978-0-8330-4465-5 .

- ↑ Defensive democracy or "conviction terror"? ( Memento from October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) at political-bildung-brandenburg.de.

- ↑ Global Terrorism Database . Retrieved December 6, 2018.

- ↑ https://fas.org/irp/threat/nctc2011.pdf

- ↑ Institute for peace & economics, Global Terrorism Index 2014 , page 2 - quote: "In 2013 terrorist activity increased substantially with the total number of deaths rising from 11,133 in 2012 to 17,958 in 2013, ...", "Over 80 per cent of the lives lost to terrorist activity in 2013 occurred in only five countries - Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria. "," .., 66 percent in 2013, are claimed by only four terrorist organizations; ISIS, Boko Haram, the Taliban and al-Qa'ida and its affiliates. "

- ↑ Islamists commit 66 percent of all bloody acts. Welt online , November 18, 2014.

- ↑ Institutes for economy & peace: Global Terrorism Index 2015 page 4 - Quote: 'The largest ever year-on-year increase in deaths from terrorism was recorded in 2014, rising from 18,111 in 2013 to 32,685 in 2014.' Page 2 - Quote: 'Terrorism remains highly concentrated with most of the activity occurring in just five countries - Iraq, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Syria. These countries accounted for 78 per cent of the lives lost in 2014. ' (Number of victims of terrorist organizations, pp. 41–43)

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2015, p. 2 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ a b Global Terrorism Index 2014, p. 2 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2015, p. 4 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2015, p. 35 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ a b Global Terrorism Index 2015, p. 37 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2016, p. 2 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2016, p. 22 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2017, p. 4

- ↑ a b Global Terrorism Index 2017, p. 2 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2018, p. 4 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2019, p. 2 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ Global Terrorism Index 2019, p. 3 Institute for Economics and Peace

- ↑ David McKitrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney, Chris Thornton, David McVea (Eds.): Lost Lives. 2004.

- ^ National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), Global Terrorism Database , accessed 2016.

- ↑ Why is there a lot more likely than a victim of a terrorist attack. In: Südkurier . April 14, 2016; Ortwin Renn : Terror in Europe: No reason to be so afraid. In: Zeit Online . 19th July 2016.