Königspfalz Frankfurt

The Königspfalz Frankfurt , historically incorrect often also Kaiserpfalz Frankfurt , was an important base of the Carolingian and Ottonian kings and emperors located on the Frankfurt Cathedral Hill . It was created at the beginning of the 9th century under Ludwig the Pious , the son of Charlemagne , and replaced a royal court of the Merovingians in the 7th century, who in turn had conquered the area around Frankfurt am Main from the Alamanni . In the following two centuries the complex was repeatedly rebuilt and expanded, with the previous buildings of today's Imperial Cathedral of St. Bartholomew being built .

From the 11th century the Palatinate lost its importance as the residence of German rulers. Only in the Hohenstaufen period, around the middle of the 12th century, the place was under Konrad III. again place of farm days. It is controversial whether the Saalhof, which was built according to the classical interpretation as a royal castle from this time, was a direct successor, or whether the Palatinate on the cathedral hill was still used. The abandoned Palatinate disappeared under the subsequent civil development of the late Middle Ages . The Palatinate Church gradually replaced the Gothic cathedral.

In the early modern period , the search for the Palatinate began, which scholars and scientists, for centuries, equated with the Saalhof due to the lack of visible structural remains. Only after the destruction of Frankfurt's old town by the air raids on Frankfurt am Main in World War II , archaeological excavations were able to uncover the Palatinate at its actual location. Their remains have been presented in the Archaeological Garden since the early 1970s . It was built over with the town house as part of the Dom-Römer project from 2013 to 2016 upon receipt of the finds . Since August 2018, the finds have been presented in the new exhibition Kaiserpfalz Franconofurd as a branch of the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt .

Geography and topography

Frankfurt am Main is located in the Lower Main Plain , part of the Hessian depression that continues the Central European Rift northwards from the Upper Rhine Plain . In the Pleistocene , between 2.5 million and 10,000 years before our era, there were three significantly different levels of terrain, which are known as the main, middle and lower terraces . The lower terrace near the river is characterized by deposits of gravel and sand.

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein from 1862 with overlay based on Karl Nahrgang )

The level of the main terrace forms the plateau of the Berger Ridge , which reached in a geological clod as a limestone barrier to the Sachsenhausen mountain . The floe was cut by the Main between the Röderberg in the north and the Mühlberg in the south, which established a narrow valley that was shaped for a long time by floods, swamps and rivers, but which at the same time opened up the best possible access to the river.

In the Holocene , individual rivers settled within the lower terrace and then gradually cut into the deposited gravel, which led to the formation of individual high water-free hills. In the same epoch, flooded alluvial clay was deposited in the entire current urban area, which today represents the geological subsoil of all cultural layers above it.

The cathedral hill , on which the royal palace and the eponymous cathedral were later built, was such a flood-free hill on the lower terrace about 325 meters long and 125 meters wide. In the north the area was protected by a boggy oxbow lake of the Main , the Braubach , in the approximate course of today's road ; in the east, beyond today's tramline , the swampy fishing field . To the south, the Main, which ran about 100 meters north of today's bank, bordered, and in the west, around today's Römerberg, another boggy depression began.

Only at the height of the Römerberg did a narrow jetty lead safely from the Carmelite Hill, which is also flood-free, a little further to the west, at the site of the present monastery, into the area, which is therefore also known as Cathedral Island . To the southwest of the landing stage, the ford formed by limestone rocks was around today's Fahrtor , which Frankfurt owes not only its name to, but also its existence in general. It only disappeared in the 19th century when the Main was dredged in favor of increasing shipping traffic.

history

Prehistory and previous buildings

Archaeological finds show regular settlement of the cathedral hill since the Neolithic Age , and settlement continuity has existed since late antiquity at the latest . After the extensive destruction of the Roman settlement on the Cathedral Hill in the wake of Limes If the mid left there the 3rd century Alemanni down. Shortly after 531 these were driven out by Franks , led by the ruling family of the Merovingians .

The kings of the dawning Middle Ages did not have a permanent seat of power, but traveled with their large entourage through the empire, in which they owned a large number of royal corpses. This was the result of an initial lack of administrative facilities, an oral way of governing and the fact that the management of the entire court staff of a region could only be expected for a certain period of time. Only economically particularly efficient and well-developed land and water estates were built in a position to accommodate the royal court over longer periods of time.

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein from 1862 with overlay after Magnus Wintergerst )

Several Fronhöfe were combined in so-called fiscal districts. In the Lorsch Reichsurbar , which dates from the late 12th century but has been reproducing documents since the middle of the 8th century, Frankfurt appears as the center of such a district of about 20 × 22 km between Kelsterbach and Bürgel with parts of the Reichsforst Dreieich ; the core district was to be delimited between Main and Nidda , Nied to Bischofsheim with a northern extension to about Hausen and Seckbach . Side courtyards were in Griesheim , Kelsterbach, Seckbach and Vilbel .

A Merovingian royal court in Frankfurt for the administration of this extensive property is likely to have been established relatively soon after the Frankish conquest in the 6th century. In view of its importance, it must be assumed that the complex on the cathedral hill is much larger than the very sparse archaeological evidence - no written documents are available for this period - have so far been able to show. The Carolingian royal palace and, above all, the far-reaching late medieval cellars have erased a large part of the traces of this time.

The remains of an approximately 11.5 meter long and 7 meter wide St. Mary's Church were excavated in the southern area of today's cathedral tower , also referred to in research as the apse building . North-east of the foundations were long one about 10 meters and about 4.5 meters wide, with post-Roman underfloor heating -equipped building, known as Building I . Its function has not been fully clarified by research, for the presentation see Die Domgrabungen 1991–1993 in the review .

Small remains of other stone buildings were uncovered in the area of the former Tuchgaden and under the Red House that was formerly located there . According to the latest research, another rectangular building can be seen in them in an east-west direction and to the west of it a perpendicular building with a conspicuous semicircular apse or niche. Ceramic finds point to the 7th or 8th century. The connection of the buildings on the cathedral and on Tuchgaden results in a complete system that extends over almost 100 meters across the cathedral hill.

In Building I, which soon fell into disrepair, at the beginning of the 8th century, a noble girl was buried with rich grave goods, whose undisturbed grave was only rediscovered in 1992. The girl certainly came from the high Franconian nobility, which the king had appointed to administer his property, perhaps the family of the treasury administrator Nantcarius , who was documented in the times of Charlemagne in Frankfurt and who has been attested in the region since the early 7th century.

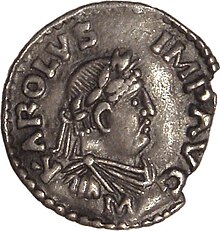

Charlemagne in Frankfurt

It makes sense to associate the Königspfalz Frankfurt with the legendary founder of the city, Charlemagne : After the Christmas party in 793 in Würzburg , he drove down the Main and on February 22nd, 794 put “sup (er) fluvium Moin (in ) loco nuncupante Francono FURD " the MonasterySankt Emmeram in Regensburg from a document, which today represents the oldest original name obtained certificate of Frankfurt. Due to only insignificantly more recent sources, however, it can be assumed that the Carolingian ruler arrived there in the last days of 793 and overwintered.

The most important events during his subsequent eight-month stay were the celebration of Easter and the Synod of Frankfurt , which met there in June 794 with probably several thousand participants from all over Europe on 56 spiritual and political questions. Fastrada , the fourth wife of Charlemagne, died on August 10, 794 and was transferred to St. Alban near Mainz for burial . After he left shortly afterwards, as far as is known, he did not return to Frankfurt for his entire life.

It is unclear why Charlemagne went to a city that at that time stepped out of the darkness of history, made it the site of a synod of such rank, and stayed there for a long time. There is speculation about a short-term, unscheduled decision against the background of the bad harvests reported for the year 793, which accordingly hit the west and south of the empire particularly hard. The Frankish empire, which had grown rapidly through conquests, was also acutely threatened at that time:

From the east the Avars , a Central Asian equestrian people, advanced again and again, especially against the Lombard kingdom in Italy, which was only incorporated in 774, and Bavaria , which was conquered in 788 . In 792/93 the Franconian ruler from Regensburg was therefore preparing for a major campaign against the greatest enemy of the empire. But the bad harvests were not enough, in 793 the Saxons residing in what is now northern Germany and the Saracens in the south-west invaded the empire, which is why the Avar campaign had to be postponed to move against the Saxons.

Thus the previously unknown, but safe, Franconian royal court, which has been recognized as Franconian territory for centuries, was recommended from a geographical point of view, especially since Mainz , Regensburg , Worms and Würzburg were bishoprics where clergy and nobility could make claims. Also in view of the fact that Frankfurt in the east of the empire was perhaps less affected by the bad harvests, it was suitable as a place for lodging and catering not only for the court staff, but also for the subsequent synod.

Whether the construction of a royal palace actually took place or took place during this time, or only under Charles' son, Ludwig the Pious , can not be fully clarified on the basis of the archaeological findings and surviving written documents. In research in the last few decades, however, the prevailing opinion is that it was Ludwig the Pious who first became active as a builder; for the representation see discourse about the builders of the Königspfalz . According to the majority opinion, the Synod of 794 will have taken place in the buildings of the Merovingian era. Wooden buildings on the cathedral hill, tent camps and accommodation in the other royal courts of the Treasury are also possible, but can of course no longer be proven.

Construction of the Palatinate under Ludwig the Pious

The majority of the walls in today's Archaeological Garden are therefore the remains of the Palatinate, which was probably commissioned by the son of Charlemagne in 815 and completed at the latest on his next visit in 822. Not only the fact that large parts of the Merovingian predecessor buildings were removed from the ground itself, but also that almost the entire enclosing walls have survived to this day despite the massive interventions of the later medieval buildings, speaks in favor of the demands on the execution .

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein from 1862 with overlay based on Magnus Wintergerst )

The foundations consist of hammer - right limestone and basalt lava pieces ; The rising masonry is made up of irregular, partly sandstone blocks , partly basalt, limestone and sand rubble stones . At the particularly well-preserved northeast corner, a corner block made of carefully worked sandstones can be observed. In connection with the non-uniformity of the rest of the masonry, this indicates that the building was once largely plastered and only the corner blocks were left exposed to stone. The whitish and gravelly lime mortar was poured into the foundations like a pour and still has a hardness similar to concrete.

The main building, the aula regia , i.e. King's Hall, was a 28.3 meter long and 14.4 meter wide building. Due to the thickness of the walls of around 0.9 meters and the fact that at least one excavated inner pillar was excavated, an original two-storey structure is considered to be secure . The seat of the ruler was assumed to be in the east of the upper floor. On the west side of the building there were similar, square extensions in the north and south, which perhaps served as stairwells for the management of the throne room. The main staircase with vestibule can be seen in another, archaeologically poorly documented structure on the west wall. That porticus , "per quam gradatim ascensus et descensus est in palatium" , was given in 979 by Emperor Otto II to Bishop Hildebald von Worms , which is considered a written confirmation of the two-story building of the King's Hall.

It is interesting to compare it with other Palatinate buildings from the Carolingian era, for example in Aachen , Ingelheim or Paderborn . The older Pfalzen in Aachen and Ingelheim were single-storey buildings based on the ancient model, although the older one, built from 776 onwards, is also two-storey and also similar in size to the Königshalle in Paderborn. Particularly when looking at later Salian and especially Hohenstaufen palaces or castles such as Gelnhausen or even Goslar , there are striking similarities: the Palas in Gelnhausen has almost identical dimensions, while that in Goslar is almost twice as long, but only slightly wider. The Frankfurt Palatinate was thus probably one of the first representatives of a more independent, progressive type with a future-oriented effect, more detached from the ancient models.

To the east of the King's Hall, a gate hall was built, whose contemporary function has not been clearly clarified by research. Their slight offset to the north compared to the Palatinate building is striking, which means that the building line of the apsidal building was deliberately respected. It was probably the beginning of a church complex with an atrium , which could no longer be realized during the reign of Louis the Pious, perhaps because of the disputes with his sons.

With the birth of Charles the Bald from Ludwig's second marriage to Judith , the Palatinate in Frankfurt was the site of an event in 823 that was supposed to trigger shocks of European dimensions: in 817 he passed a succession regulation with the Ordinatio imperii , which, contrary to Franconian tradition, was not a classic after his death Reich division according to Frankish tradition would have meant. Instead, he elevated his eldest son Lothar I to co-emperor and successor while he was still alive, and his younger sons Pippin I and Ludwig the Germans to be subordinate kings with their own partial empires.

Probably under the influence of Judith, Ludwig changed the succession plan in favor of Karl, for whom he wanted to create a new sub-kingdom with Swabia . In 830 and 833 the three sons from their first marriage revolted against their father, but recognized him again in 834. After the unexpected death of Pippin at the end of 838, his eldest son rose up against him because he was again disadvantaged in the inheritance regulation that was now in place. In the winter of 838/39 that followed, Ludwig the German prevented his father from spending his time in the Frankfurt Palatinate. This happened again: already in 833/34 he had briefly occupied Frankfurt, which shows the increasing strategic importance of the Palatinate as a bridgehead for Eastern Franconia . It was not until January 839 that Ludwig the Pious was able to cross the Rhine , push back his son's troops and move into Frankfurt, where he stayed until Lent.

In the summer of 840, a few months before his death, he was in the Frankfurt Palatinate for the ninth and last time in his life and, unlike his father, had visited it every two to three years on average. With the division of Verdun in 843 , clear conditions and peace returned to Central Europe for at least a few years. Ludwig the German became King of Eastern Franconia and thus beneficiaries of the Frankfurt Palatinate.

Salvatorkirche and -stift

Despite his more than a decade-long argument with his father, Ludwig the German fulfilled his wish to equip Frankfurt am Main with an appropriate sacred building. In the area of the nave of today's imperial cathedral , the Salvator Church , which was probably begun around 843 and consecrated in 852 by Archbishop Rabanus Maurus of Mainz , was built in research (against the background of a building II, which was accepted until recently, at roughly the same place, see The cathedral excavations 1991–1993 in Criticism ) also referred to as building III .

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein from 1862 with overlay based on Magnus Wintergerst )

As a result of the consecration message, the Salvatorkirche is the oldest building on the Frankfurt Cathedral Hill, which can be both accurately dated and clearly assigned to a builder. It is also archaeologically documented outstanding by numerous excavations since the 19th century in large parts and reconstruct:

Typologically, the building was a three-aisled basilica with a semicircular east apse attached directly to the transept . The transept was designed “pushed through” based on ancient models, so it was the same height as the central nave. The proof of this is the fact that the crossing in the extension of the nave walls was not eliminated in this type of building, for which no archaeological evidence could be found.

The internal dimensions of the church were 29.80 meters long and 22.20 meters wide. The east apse had exactly the same width as the central nave at 7.20 meters, the side aisles were probably about 4.20 to 4.30 meters wide. A separation of the central and side aisles by rows of pillars is certainly considered safe, but their number and shape can only be speculated, since no archaeological finds have been made on this so far.

Only the westwork is missing almost any archaeological findings from the 9th century, as these were destroyed by later renovations. In analogy to comparable church buildings of the time, it is most likely to be reconstructed as a simple straight facade that opened the main entrance to the north aisle in the north. At the same time a corridor was added to the gate hall to the east of the King's Hall, which was still unfinished under Ludwig the Pious, which enabled the ruler to walk through this gate to the new church building.

It is noticeable that the center line of the new basilica was aligned precisely with the grave of the Merovingian girl who had found her final resting place there almost 300 years ago. Consciously, both the grave and the remains of Building I, which fell into disrepair in the 7th century, remained intact in the ground. Grave finds also show that a cemetery was again created around the new church after one was laid out around the girl's grave in the 8th and perhaps the first half of the 9th century.

Coinciding with the dedication of the Basilica was in the tradition and as a substitute for at Lotharingien fallen Aachen a collegiate of twelve clerics founded. Ludwig the German endowed it richly with royal property in the whole Rhine-Main area , which formed the basis of the important position in the Holy Roman Empire , which the monastery was able to maintain in the 950 years of its existence. In contrast to the Salvator Church , which in the late Middle Ages changed its patronage in favor of St. Bartholomew and thus its name, the Frankfurt Abbey always retained its founding name as Salvator Abbey .

In the first centuries of its existence there was naturally a close relationship between the monastery and the rulers who regularly came to Frankfurt, who probably also appointed the abbots - who later became the monastery - until the end of the Ottonian period . In the Salian period there was a transition into the sphere of influence of the Archbishop of Mainz. As early as the middle of the 12th century, these conditions had become so entrenched that the Hohenstaufen rulers who were active in the Pfalzort no longer even attempted to reclaim rights to the monastery.

The Palatinate's heyday

With the construction of the Salvatorkirche and the establishment of the monastery, the royal palace was not only structurally completed in the middle of the 9th century, but was now also able to hold all church festivals and other important events there in a representative setting. When he died in the Frankfurt Palatinate in 876, Ludwig the German had demonstrably stayed there at least 34 times during his life. With this, the place next to Regensburg had risen to become its main Palatinate, which the contemporary historian Regino von Prüm even referred to as "principalis sedes orientalis regni" .

Important events in the reign of Ludwig the German during his stays in Frankfurt were Lothar II's ascension to the king over the Lotharingia named after him on the occasion of the division of Prüm in 855; Court days in the years 859, 865, 866, 870, 871, 873 and 876 as well as army assemblies on the occasion of campaigns in the years 858, 862 and 867. Numerous Easter and Christmas celebrations held there also fall in these years.

Frankfurt at that time did not only consist of the stone buildings of the Palatinate, of course: at the later chicken market , stone foundations, perhaps of simple half-timbered houses, were uncovered on today's Römerberg remains of pit houses . They served as accommodation for unfree royal people who worked as farmers and craftsmen. From there they managed forest and meadows as well as fishing, animal husbandry and storage for the maintenance, sub-management and administration of the Palatinate and monastery. Since visitors to the Palatinate were not provided with, but had to pay for the maintenance of themselves and the extensive entourage themselves, the existence of a market and a port on the Main can be assumed as early as the 9th century.

In the tradition of his father, Ludwig the German told his second son Ludwig III during the division of the empire in 865 . the eastern kingdom to. At that time it already consisted of Franconia , Saxony and Thuringia . In 869, Lothar II, who had been made king in Frankfurt, died without legitimate descendants, which is why his empire - Lotharingien - was divided between West and East Franconia in the Treaty of Meerssen in 870 . The large areas that Ludwig the German was able to win, he also spoke to Ludwig III. to.

Due to the size of this inheritance, the death of Ludwig the German immediately aroused the desires of Frankfurt-born Charlemagne , the ruler of western France. Its territory now encompassed a large part of what is now France , over which Charles had ruled as Roman emperor since December 875 . After he had already reluctantly accepted the Treaty of Meerssen, he wanted to expand his empire militarily to include eastern Lotharingia and thus to the Rhine .

The following devastating defeat in the battle of Andernach was only the beginning of a devastating development for the west of Franconia, at the end of which in 880 the Treaty of Ribemont stood, in which the grandsons of Charlemagne in military distress also passed western Lotharingia to the son of Louis the Germans had to cede. This established the western border between what would later become France and the Holy Roman Empire , which was to remain unchanged until the early modern period .

Extensions in the Ottonian period and decline

( chromolithography by Friedrich August Ravenstein from 1862 with overlay after Magnus Wintergerst )

By the year 1000 at the latest, the palace complex and the small settlement that was supposed to be around it were surrounded by a wall under the Ottonian rulers . The central reference of the wall to the Palatinate as well as the documented regular visit of the Saxon ruling dynasty shows the unbroken importance of Frankfurt am Main compared to the Carolingians . A total of 40 stays made the facility there together with the one in Ingelheim the most important of its time in the Rhine-Main area. Major renovations to the Salvator Church also took place in the same era:

The old apse in the east was replaced by a rectangular presbytery with a stilted, semicircular apse. In the west, the building received a westwork with a gallery, whereby the Merovingian grave also disappeared under the pillar foundations. It stands to reason that the Saxon aristocratic house, in contrast to the Franconian aristocratic family, could no longer make any reference to it. In front of the westwork were twin towers standing directly next to one another, which presumably opened up the gallery and also served as bell towers. The distance to the Merovingian St. Mary's Church was thus further reduced, a demolition can be ruled out despite its unexplained duration, at least in connection with the Ottonian expansion of the Salvator Church.

Under the Salian dynasty , Frankfurt am Main - measured in terms of visits to the king - rapidly lost its importance. The synod of 1027 under the newly crowned Emperor Konrad II was the last major event of the 11th century. Until the first visit of a Hohenstaufen ruler in 1140, i.e. in over 100 years, only five further stays of the king can be proven.

The reasons for this change are unknown. In research, the point in time at which an archaeologically verifiable fire disaster occurred is just as controversial as that of the final demolition and development of the Palatinate; for the representation see discourse about the decline of the royal palace . The tendency is that the western annex buildings of the Königshalle were removed and built over earlier than the Königshalle itself. This would explain in a satisfactory manner that only the buildings and streets that developed on the east of the former Palatinate area and that were preserved until 1944 were based on the former Carolingian buildings.

Linked to the return of the Staufers to Frankfurt is the question of the location of their numerous stays and diets. As the only partially preserved non-church building from this time in the old town area, the Saalhof , located southwest of the cathedral hill on the Main , is traditionally seen as a royal castle that replaced the royal palace, which was no longer used. Both contradictions with regard to its dating and dimensions give rise to the alternative interpretation, whether it was not more the seat of a bailiff or another high-ranking personality; for the representation see relationship to Saalhof .

In this case, a third, unknown building - perhaps in the area of the Römerberg - or against the background of the questionable final departure of the old royal palace, this would also have served the Staufers for the aforementioned purposes. A little later, classical palaces were no longer used when residences were built. The narrow-lined development of the cathedral hill with town houses, which spread in the late Middle Ages, preserved the remains of the Carolingian-Ottonian complex primarily by using its massive walls for cellars.

At the same time, with the successive Gothic construction of the cathedral , the sacred buildings of the former royal palace disappeared from the cityscape. While the Carolingian Church of St. Salvatore had to give way in the course of the 14th century at the latest, the Merovingian Church of St. Mary may have survived until 1415 - in that year the foundation stone of the cathedral tower was laid in its place. According to archaeological findings, its foundations are based directly on the remains of the church.

Research history

The search for the Palatinate

(engraving by Theodor de Bry after presentation of Jean-Jacques Boissard )

In the course of humanism at the beginning of the early modern period , an interest in the origins of the city and the search for the Palatinate mentioned in a document gradually arose in Frankfurt am Main , starting with the Stiftsdekan and historian Johannes Latomus in 1562. The only one that looked particularly ancient at the time and free-standing building in the center of the old town was obviously the Saalhof , which he consequently equated with the building of Ludwig the Pious .

At the beginning of the 18th century, the chronicler Achilles Augustus von Lersner followed , but also introduced a "two-palatinate theory" with the assumption of locating an independent palatinate built by Charlemagne at the site of the Leonhardskirche . As a basis for his acceptance, he made the document from 1219, with which the Staufer ruler Friedrich II gave the land on which the church was to be built to the citizens. The document speaks of “area seu curtis” . So far, a previous building cannot actually be ruled out, as archaeological investigations have been carried out on the oldest standing church in the old town for the first time since 2011 .

In the 19th century, the theory of two Falzes was further solidified, representatives were among others Johann Georg Battonn , Anton Kirchner and Georg Ludwig Kriegk . On the occasion of the demolition of parts of the Saalhof in 1842/1843 in favor of the early historic Burnitz building that is still preserved today, the autodidact Georg Heinrich Krieg von Hochfelden examined it in detail. He saw large parts as Romansh , but still considered the core to be Carolingian , and also provided otherwise imprecise, sometimes speculative information.

After the fire in the cathedral on August 15, 1867, during the restoration work under Franz Josef Denzinger , excavations were also carried out inside the nave, which marked the beginning of modern archaeological research for Frankfurt am Main. Despite considerable methodological and documentary deficiencies, larger parts of a previous building were uncovered, which were assigned to the documented Salvator Church of the 9th century. Franz Jacob Schmitt was the first to create a reconstruction based on this data in 1892, which was to remain largely unchanged until the post-war period.

The discovery of the sacred part of the royal palace changed nothing in the research opinion on its secular parts. War von Hochfelden's drawings and conjectures shaped research and literature for almost a century. Even the third volume , published between 1902 and 1914 and co-authored with Rudolf Jung by the head of the city archives at the time, of the standard work Die Baudenkmäler in Frankfurt am Main , which is still relevant today , was adopted almost unchanged. Despite some critical work in detail, there was no valid argument against equating the Saalhof with the royal palace until the period after the First World War , mainly due to a lack of further actual investigations into the building fabric .

It was not until the 1920s that they returned to the basic idea of Latomus, and in 1932 Karl Nahrgang even suspected the Palatinate to be in Sachsenhausen . In 1936 Heinrich Bingemer came to the conclusion that the Palatinate must be under the cathedral hill after studying the sources beyond the early Middle Ages . He concluded this from a historical report, according to which a covered corridor led from the Salvatorkirche, i.e. the predecessor of today's cathedral , to the Palatinate.

He was also able to date the Saalhof correctly as a purely Romanesque building for the first time, not just in reverse, but also in the course of a short excavation . Since Bingemer did not publish his findings and only represented them in lectures, with reference to the fact that the location of the royal palace on the cathedral hill had to be confirmed by archeology, they were initially not taken up in research and literature. However, there was no room for maneuver for archaeologists due to the extremely dense development of the area in question.

Excavations and rediscovery

In March 1944, Allied bombings destroyed the entire old town of Frankfurt , making it possible to excavate the largest and most important old town in Germany to date. However, the urban archeology was paralyzed by the war events for around seven years, so that in many parts of the city, especially in the eastern part of the cathedral hill, rebuilding took place without prior investigation of the cultural soil. It was not until 1952 that Hans Jürgen Hundt was commissioned to rebuild the Museum of Early and Prehistory - since 2002 the Frankfurt Archaeological Museum - so that excavations on the Dom-Römer area, i.e. the west of the cathedral hill, could begin the following year.

In the same year, archaeologists , including Hundt, Dietwulf Baatz , Walter Sage and Otto Stamm , came across the northeast corner of the Königshalle in the cellar of the former Goldene Waage house. In the further course of the "classic period" of research into the old town on the Cathedral Hill, which lasted until 1957, the dimensions of the Palatinate and its extensions were almost completely documented. The results published by Stamm in 1955 in the Germania magazine as a preliminary report in the context of the historical sources on the Royal Palatinate are still the key work of modern Palatinate research.

Subsequent excavations at the Saalhof under the direction of Stamm were also able to confirm Bingemer and thus conclusively prove that the Hohenstaufen - Romanesque royal castle on the Main was not connected with the stay of Charlemagne or the royal palace. As early as the spring of 1955, the remains of a Merovingian church - the so-called apse building - under the cathedral tower had been discovered under Stamm , which, however, was not included in any published plan of the old town excavations until 2007 and was therefore largely unknown to researchers.

The favorable situation for archaeologists in the decades after the Second World War ended in 1969 when the rapid reconstruction of the city also affected the west of the cathedral hill: within a very short time, the almost four-meter-high cultural layers for the construction of the Dom / Römer underground station were created , the new building of the historical museum , an underground car park and finally the technical town hall were excavated down to the geological subsoil. As a result, considerable parts of the oldest Frankfurt settlement soil, which had not been fully investigated, was lost forever. For research, this represents a considerable gap, especially in view of the destruction of large parts, including the written records, when the Frankfurt City Archives were destroyed .

As a concession to the archeology, the area of the former royal palace with the excavation remains has been presented in the archaeological garden since 1973 . Since the surrounding area was artificially raised above the level actually existing until 1944 through the construction of the underground car park, the impression of a deep pit resulted, especially to the north and west, although the level between the Pfalzboden and the last historical surface was only about two meters amounted to. Furthermore, the floor level between today's and historical Palatinate floor is 50 to 80 cm lower, so that not only the walls but also the foundations of the Königshalle can be seen. Also, some of the findings are visibly no longer preserved in situ , but have been modernized for reasons of didactics .

Younger development

In November 2006, the Technical University of Darmstadt and Architectura Virtualis GmbH presented a three-dimensional computer reconstruction of the Frankfurt Königspfalz, which was based on the data from Wintergerst. The reconstructed construction stages from the 7th to the 11th century allow a better understanding of the ruins presented in the Archaeological Garden than is possible with the information material presented there. The latter is partly out of date because it goes back to the research status of 1994.

From 2012 to 2018, the Dom-Römer-Areal was rebuilt after the Technical Town Hall was demolished, based on the state of the pre-war period. Due to the reconstruction of the south side of the former Altstadtgasse Markt , whose cellar once partially included the substance of the Palatinate, a new building of approximate historical dimensions was built on the site of the former Königshalle. The architecture of the new building, known as the town house and opened in 2016, was hotly contested for a long time, as was its future use. It serves as an exhibition and event building, but above all to provide permanent protection for the excavations from the weather. In August 2018 the exhibition opened under the new name Kaiserpfalz Franconofurd as a branch of the Historical Museum. The exhibition includes an approximately two-meter bronze model of the Carolingian Palatinate, designed based on the findings of the most recent excavations from 2012 to 2014, which shows the structural status of the time around 860 AD on a scale of 1:90, as well as a large-format three-dimensional digital one Reconstruction as a so-called image of life .

Controversial Aspects of Palatinate Research

Discourse about the builder of the Königspfalz

In his preliminary report from 1955, Otto Stamm clearly advocated Ludwig the Pious as the builder of the royal palace and thus a construction period from around 815 to 822. In the absence of an exact datability of the archaeological finds, he essentially justified this by the fact that, despite the numerous written documents relating to the events of 794 in Frankfurt am Main, not a single one can be used for building research, but those from 815 onwards.

Marianne Schalles-Fischer countered this in 1969 in the first major scientific work on the Frankfurt Palatinate in the 20th century, and advocated for 794 existing Palatinate buildings built on behalf of Charlemagne . Criticism of the interpretation by Schalles-Fischer quickly arose, but it was only completely refuted by the work on the Frankfurt Palatinate published from 1985 to 1996 by Elsbet Ort , Michael Gockel and Fred Schwind in the series Die Deutsche Königspfalzen . In spite of passages that have already been partially overtaken by the latest research, the latter must be regarded as a basic standard work, particularly with regard to the complete listing and registration of all sources on the Frankfurt Palatinate from the early to the late Middle Ages.

Schalles-Fischer saw in Frankfurt a. a. the "planned re-establishment of a royal palace complex by Charlemagne", which he had developed by building Wormser Strasse. However, it was unable to provide any evidence for this assumption. She also looked for arguments in a documentary way in early attributions of Frankfurt with palatium , which at first glance have actually come down to 794.

On the occasion of the synod, the description of villa predominates in the written sources , which indicates the still existing Merovingian royal court. A document made out in Frankfurt in 794 with the addition palatio - cited by Schalles-Fischer - is no longer in the original, but only in three later, mutually differing copies of the 17th century (one even without a palatio ), which at least has evidential value in the The context of building research.

A third designation of the buildings during the Synod, also used by Schalles-Fischer, with “in palatio retinendum” is contextually less to be translated as “at the Palatinate Frankfurt retained” and more as “at the court”. The only contemporary mention used in the local sense remains a report by Italian bishops that the synod took place “in aula sacri palatii” . Here, too, it must be taken into account that the presence of the king justified such a designation, so the assembly can also have met in the so-called aula der domus regalis of the farm yard or in the church.

Abstract speaks against building activity under Charlemagne, that in contrast to Aachen , Ingelheim , Paderborn , Nijmegen , the Main-Danube Canal or the construction of the Rhine bridge near Mainz, this was not explicitly recorded, although the tradition of the projects mentioned shows that there was an interest in documenting this. This is underlined by the fact that, as far as we can tell, his stay in Frankfurt was the only one of his life.

The written documents that pass on his stays in Frankfurt am Main also point to Ludwig the Pious as the builder. One year after the death of his father, Ludwig visited the city for the first time. When he returned in 822, he was able to stay in “eodem loco constructis ad hoc opere novo aedificiis, sicut dispositum habuerat” . The sources become even clearer in 823 when his son, Charles the Bald, was born “in palatio novo” .

In the light of their thesis of a palace building already at the time of Charlemagne, Schalles-Fischer evaluated the tradition, which for the first time was explicitly to be understood as building news, merely as evidence of a building activity ordered by Ludwig the Pious. Your translation of “opere novo” with “in a new way of building” does not explain the meaning of the verb that characterizes the building process, the activity of the construction with “contructis […] opere novo aedificiis” .

Against the background of the rare and, if at all, questionable connotation of Frankfurt as Pfalzort 794, it is noticeable that these attributions increase from 823 onwards or become a common part of the imperial certificates issued there. Stamm also stated that a Palatinate built under Charlemagne would hardly have required a new building after 28 years, but rather much older royal buildings, in which the 7th century Merovingian buildings can be recognized.

Discourse about the decline of the royal palace

Archaeological evidence

The disputes in research about the decline of the complex are on a much broader scale than that at the time when the royal palace was built. According to Otto Stamm, the archaeological findings showed on the connecting passage to the Salvatorkirche, in and in front of the outer walls of the gate hall and inside the royal hall a fire layer 8 to 25 cm thick made of gray and black charcoal tapes . Furthermore, burn damage was found on the rising walls of those rooms; no corresponding findings could be made on the western extensions.

Above the fire layer, but still below the subsequent demolition layer of the Palatinate, stone embroidery spread out, which certainly served as a substructure for a floor. It can therefore be assumed that at least parts of the Palatinate were rebuilt after the fire. The following thick gray-yellow to brown demolition layer, 25 to 100 cm thick, consisted largely of rubble, the pebbly light mortar typical of the Palatinate buildings and Carolingian stone blocks. Numerous excavation pits showed that the excellent stone material was widely used for new buildings.

Both mica ware , which was produced from the middle of the 9th century and real Pingsdorf ware , which was produced between the 10th and 12th centuries , were found in the ceramics . The fire cannot have started before the 10th century. The dating of the reconstruction is not possible due to the lack of ceramics, or it is just as uncertain as that of the fire layer. The ceramics of the demolition layer contained both mica ware and genuine Pingsdorf ware, but as a special feature a variant with engobe painting, which, according to the latest research, can be dated to the 12th century.

Historical-critical classification

The classification of the archaeological findings in the context of historical development and historical sources is difficult. The finding does not allow an exact dating of the fire, as the terminus post quem can only be named as the 10th century due to the pottery. The rebuilding of whatever type or the timing of the abandonment of the plant is, however, uncertain. The more recent findings on ceramics from the demolition layer point to the 12th century for the latter event. The periods of time that lie between the three events cannot be determined.

From the point of view of classical historiography, in contrast to the emergence of the Palatinate, there is no tradition whatsoever. Contemporary historians evidently took no notice of the three events, which means that they can only be viewed in the light of the otherwise traditional urban development. The rapid loss of importance of Frankfurt am Main during the Salier period is often associated with the decline of the secular part of the complex. Following this, this should be set early against the background of the royal stays.

Marianne Schalles-Fischer referred to the year 1012 as the terminus post quem , in which the last time the last Ottonian , Heinrich II. , Was mentioned for the last time in a document about “regio palacio” , although it should be noted that the following "actum F." is now predominantly used and has already found numerous uses in previous years. The last stay of Heinrich II in the years 1017/18 appears to be a more frequent approach, since the synod of 1027 did not necessarily take place in palace buildings; as terminus ante quem the visit of Heinrich III. 1045, as this was only due to illness and tradition does not mention any special rooms. However, the classification based on stays by the king is always fraught with the uncertainty of not being able to differentiate between the fire and the demolition.

However, the Salians also visited other old royal places comparatively rarely and increasingly relocated their stays to bishops. It is therefore also possible that the lack of visits led to the facility being neglected and decaying. Archaeological evidence suggests that the fire and the indications of reconstruction are by no means completely destroyed. After all, the rare presence of rulers is not a direct argument in favor of the destruction of the building; rather, appropriate rooms must have been available for a ruler to stay at all.

Even more recent research is increasingly moving away from a quantitative abandonment of the Palatinate in the literature around the middle of the 11th century. In contrast to his earlier publications, Stamm advocated as early as 1980 in a posthumously published but no longer completed work that the Palatinate was only given up in the second half of the 12th century. As announced, he could no longer back up his thesis by dating ceramics from the layer of destruction. Ceramic research over the last few decades has proven him right by confirming the dating of the finds from the demolition layer.

Relationship to the Saalhof

Closely related to the discourse about the decline of the Königspfalz is the question of the client, the time of construction and the function of the Saalhof . The archaeological excavations by Otto Stamm 1958–1962 and 1964 showed u. a. that the residential tower and residential building ( palas ?) of the property were built in one go and only then was the chapel built on it. The latter received a little later an increase to the current height. Almost identical foundation heights and the very similar masonry technique suggest that the construction of the residential tower and chapel was very close. The excavations also showed that the buildings were placed on the south-west corner of the oldest city wall from the outside, but were included in the Staufer city wall , which was probably built in the 1230s .

As the terminus post quem for the chapel extension, due to the wood finds in its foundation, the spring 1200 can be dendrochronologically relatively exact; corresponding data for the tower and residential building are missing due to a lack of wooden substructures. The top floor of the chapel, which has been raised, unanimously follows the late Romanesque capitals of the double arcade windows there in the period around 1210/20. The capitals of the chapel, whose stylistic classification ranges from around 1165 to 1200, may contradict the dating of the foundation.

Regardless of the problems and attempts at explanation that this raises, such as seeing the capitals in secondary use, the Saalhof can not, following the archaeological and art-historical findings, neither Konrad III. at least initially served as the seat of Frederick I. The Hohenstaufen rulers came back to Frankfurt from 1140 onwards, Konrad III alone. eight times up to 1149, for which adequate quarters were required. This means that there is a discrepancy between the aforementioned findings and the historical tradition, for the resolution of which there are essentially two theories in research.

Classic theory: Königsburg

If one follows the classical, historical arguments, more evaluative theory, which was mainly represented by Otto Stamm and Elsbet Orth , then the Saalhof was a Hohenstaufen royal castle in the structure of the targeted promotion of the city at that time. Even with knowledge of the dendrochronological dating of the chapel building, Orth at least continued to follow Konrad III in important key works . as the client. In 1975 and 1980, Stamm corrected himself, probably knowing that the ceramics from the demolition layer of the Carolingian - Ottonian Palatinate were younger than had been thought two decades before, for construction to begin in the last quarter of the 12th century, but still saw an imperial building in the Saalhof .

According to this, depending on the branch of this theory, a new beginning or a temporally almost seamless change between old and new royal buildings would have taken place around the middle to the end of the 12th century. According to Stamm in his older view and Orth one would have to assume that under Konrad III. 1140 keep and Palas of Saalhofs arose, and only under their successors the Kapellenbau and a little later the increase were added. In spite of a time gap of around half a century, almost the same masonry technology would have been used. According to Stamm in his last opinion, it could be assumed that the kings used the palace on the cathedral hill or an unknown third building, at least initially.

The greatest advantage of this theory is the relative continuity of historical tradition it creates. According to Orth, it is even resilient to the now outdated opinion that the older Palatinate should give up in the first half of the 11th century, but it does not exist even before the more recent archaeological- ceramic references and the research opinion derived from them of a demolition in the second half of the 12th century Century; see. on this discourse about the decline of the royal palace . It is only very unsatisfactory in explaining the discrepancy between the style-critical and absolute dating of parts of the Saalhof, and not at all the unusually small dimensions for a Hohenstaufen complex of this type, which is also one of the main arguments of opponents of this theory.

On the other hand, it was again stated that size comparisons to determine the property of a builder are generally problematic, as the proportions of the Palas Gelnhausen or Munzenberg , even if not achieved by Seligenstadt or Bad Wimpfen . The fact that the building was incorporated into the new city wall, which appears to be planned, also tends to support the assumption of a royal builder status.

Orth, as a proponent of the theory, consequently assumed that a juxtaposition of the old and new kingship as well as the continued existence of the Carolingian complex beyond the Staufer period should have been reflected in topographical designations, most of which manifest themselves during this period. In contrast to Saalgasse , for example , in which the name of the Saalhof is still alive today, there is no reference to the continued existence of the Carolingian complex in any documents from the 12th, 13th or even 14th centuries.

Alternative theory: ministerial seat

Especially Fritz Arens and Günther Binding have doubted since the early 1970s that the Saalhof the successor in the Carolingian - Ottonian Pfalz can be seen. Above all, Binding cited a comparison of the building program and room sizes with other smaller castles of the 12th and 13th centuries: the “rîches saal” , the “Reichssal” on the upper floor of the palace , had dimensions of only 7.80 × 8.00 meters Which, not only in relation to the dimensions of the previous building, but also at the same time as the Hohenstaufen palace complex, appears completely undersized for court days of the high Middle Ages . The residential building can therefore hardly be addressed as a hall, since it lacks the typical hall.

Fritz Arens therefore saw the building as the seat of an empire ministerial , such as a burgrave or bailiff . In this case, the Hohenstaufen rulers would either have used the older Palatinate on the cathedral hill beyond the construction period of the Saalhof or a new, but no longer verifiable new building. In connection with this, the round tower on the Römerberg, first excavated in 1942, 80 meters north of the Saalhof, as a keep and the previous building of the old Nikolaikirche excavated in 1989 as the actual palatine chapel, both of which are still dated to the Hohenstaufen era. As residents of the Saalhof, Arens can imagine the Reichsministeriale von Hagen-Münzenberg , for whose Munzenberg Castle the capitals of the Saalhof chapel were perhaps originally made. This could also be an elegant explanation of the discrepancy between the style and installation time of the structural members.

Since palaces lost their importance as royal residences in the course of the 13th century - when it was first mentioned in 1277 the empire was the Saalhof "just" sitting mayor - could the old King's Hall has therefore acted without problems even for the king stays the early 13th century before with the formation of permanent royal residences, this type of government fell into disuse.

Magnus Wintergerst also indirectly supports the alternative theory when he recently advocated that the Königshalle “stood at a certain height - possibly as a ruin” - until the 13th, maybe even the 14th century. In support leads Winter Gerst on, is that until the Second World War, town houses preserved the building block between market , Höllgasse and cloth Gaden , among which was the majority of the Palatinate, oriented to the east visible at the King's Hall, while this was not the case in the West. This also applies to the streets Markt and Höllgasse, while the Tuchgaden ran diagonally over the former western annex buildings of the Palatinate. An extensive pavement, evidenced in the old town excavations, probably Ottonian period, moved in a three-quarter circle from south-east to north around the complex, and already over the later uncovered wall remains of the western annex buildings, but not the king's hall with its square north and south annexes.

Otto Stamm already saw this as a clear indication that the western annex buildings were removed and built over much earlier than the Königshalle itself. In the southern annex building of the Königshalle, the porticus would be recognizable, which Otto II. 979 Worms Bishop Hildebold with the possibility donated to extend it on all sides up to 20 Carolingian feet, which actually happened according to excavation findings. A further use of the annex building into the early modern period would also explain the conspicuous depiction of such a building at its assumed position in the first topographically accurate Frankfurt city map by Matthäus Merian from 1628.

Disadvantages of this theory are that the ceramic findings from the demolition layer of the Palatinate do not coincide as clearly as with the older theory with the time of their task in this case in the late 13th century. However, it does not seem unusual for pottery produced during the 12th century to be found in layers from the 13th century.

The cathedral excavations 1991–1993 in the criticism

Excavations in the cathedral in the years from 1991 to 1993 under the direction of Andrea Hampel yielded new findings, especially on the sacred parts of the Palatinate and the previous buildings of the cathedral. Hampel published the results back in 1994: in Building I , which was first uncovered during the excavation campaign and in which the untouched Merovingian girl's grave was discovered in 1992, she saw the first church building on the site of today's cathedral - hence the name - which, however, very soon became the research met with criticism.

Inside the building there was no altar foundation , no remains of choir screens or other fittings of a sacred space, only the cemetery around it could be taken as an indication. The most important argument against using the church, however, is hypocaust heating , for which there is no example in any other early medieval church. Finally, comparisons with ecclesiastical and non-ecclesiastical buildings in Europe at the same time speak predominantly against Hampel's view.

Thus, according to the latest research, represented by Magnus Wintergerst in his review of all archaeological findings on the Palatinate published in 2007, the building should only be viewed as functionally related to the nearby church, but not as an independent church. According to Wintergerst, the apsidal building, which has been archaeologically documented for a long time but has not been published and thus probably also unknown, had the status that Hampel postulated for Building I: in the Merovingian St. Mary's Church of the 7th century in the area of the cathedral tower he sees the first verifiable predecessor building of the cathedral .

Wintergerst was also able to dispel the previously existing uncertainty as to whether building I was built before or at the same time as the grave in favor of the first-mentioned variant. Other important findings of his processing of the excavations are that there was probably never a building II in which Hampel saw an expansion of building I in favor of the synod of 794. With this, Hampel had indirectly returned to the older theories, according to which Charlemagne was the client.

In the light of their consideration of Building I as a church building, and its location within the later Salvatorkirche, from which today's cathedral developed, such a Building II would have fitted perfectly into the development series. However, the analysis of Hampel's findings by Wintergerst clearly shows that they essentially only reconstructed Building II from the foundations of the east wall, which is speculative in a rectangular building. In addition, the qualitative analysis of the findings assigned to Building II also suggests that the foundations were strip foundations of the Salvator Church, consecrated in 852.

Wintergerst continues to take the view that von Hampel is still known as Building IIIa ("The post-Carolingian west facade"), Building IIIb ("The renovations between the 10th and 12th centuries"), Building IV ("The early Gothic hall church") and Building IVa (“The early Gothic choir building from 1239”), the post-Carolingian reconstructions of the Salvator Church, which are stylistically critical, cannot be ascribed to the 10th to 13th centuries, but to a planned Ottonian expansion around 1000.

This would be supported by comparisons with preserved Ottonian buildings as well as the antiquity of architecture, which was inappropriate for the importance of the monastery and church in the 13th century, had the expansion in the forms described, especially with stilted presbytery yokes, actually taken place during this time. The 41 Ottonian visits to the city by the Kings also suggest that the Saxon noble house commissioned large-scale renovations.

swell

Documents and regesta works

- Alfred Boretius (Ed.): Leges 2. Capitularia regum Francorum 1. Hannover 1883 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Richard Froning: Frankfurt Chronicles and Annalistic Records of the Middle Ages. Carl Jügel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1884.

- Friedrich Kurz (Ed.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separately in editi 50: Reginonis abbatis Prumiensis Chronicon cum continuatione Treverensi. Hanover 1890 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Friedrich Kurz (Ed.): Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separately in editi 6: Annales regni Francorum inde from a. 741 usque ad a. 829, qui dicuntur Annales Laurissenses maiores et Einhardi. Hanover 1895 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Paul Kehr (ed.): Diplomata 8: The documents of Ludwig the German, Karlmann and Ludwig the Younger (Ludowici Germanici, Karlomanni, Ludowici Iunioris Diplomata). Berlin 1934 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Engelbert Mühlbacher with the participation of Alfons Dopsch , Johann Lechner and Michael Tangl (eds.): Diplomata 4: The documents of Pippin, Karlmann and Charlemagne (Pippini, Carlomanni, Caroli Magni Diplomata). Hanover 1906 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Georg Heinrich Pertz a . a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 1: Annales et chronica aevi Carolini. Hanover 1826 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Theodor Sickel (Ed.): Diplomata 13: The documents Otto II. And Otto III. (Ottonis II. Et Ottonis III. Diplomata). Hanover 1893 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Georg Waitz , Wilhelm Wattenbach a . a. (Ed.): Scriptores (in Folio) 15.2: Supplementa tomorum I-XII, pars III. Supplementum tomi XIII pars II. Hannover 1888 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

- Albert Werminghoff (Ed.): Leges 3. Concilia 2,1: Concilia aevi Karolini. Hanover 1906 ( Monumenta Germaniae Historica , digitized version )

Literary sources

- Achilles August von Lersner, Florian Gebhard: The far-famous Freyen imperial, electoral and trade city of Franckfurt on Mayn Chronica […]. Self-published, Franckfurt am Mayn 1706 ( online ).

literature

Major works

- Johannes Fried: Charlemagne in Frankfurt am Main. A king at work. In: Johannes Fried (Ed.): 794 - Charlemagne in Frankfurt am Main. A king at work. Exhibition for the 1200th anniversary of the city of Frankfurt am Main. Jan Thorbecke Verlag GmbH & Co., Sigmaringen 1994, ISBN 3-7995-1204-7 , pp. 25-34.

- Elsbet Orth, Michael Gockel, Fred Schwind: Frankfurt. In: Max Planck Institute for History (ed.), Lutz Fenske, Thomas Zotz: Die Deutschen Königspfalzen. Repertory of the Palatinate, royal courts and other places of residence of kings in the German Empire in the Middle Ages. Volume 1. Hessen. Delivery 2–4, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985–1996, ISBN 3-525-36503-9 / ISBN 3-525-36504-7 / ISBN 3-525-36509-8 , pp. 131–456.

- Andrea Hampel: The Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt am Main. Excavations 1991–1993. Rolf Angerer Verlag, Nussloch 1994 ( contributions to monument protection in Frankfurt am Main 8).

- Tobias Picard: Royal Palaces in the Rhine-Main area: Ingelheim - Frankfurt - Trebur - Gelnhausen - Seligenstadt. In: Heribert Müller (Ed.): "... Your Citizens Freedom" - Frankfurt am Main in the Middle Ages. Contributions to the memory of the Frankfurt media artist Elsbet Orth . Kramer, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-7829-0544-X , pp. 19–73, here pp. 37–52.

- Marianne Schalles-Fischer: Palatinate and Treasury Frankfurt. An investigation into the constitutional history of the Frankish-German kingdom. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1969 ( publications by the Max Planck Institute for History 20).

- Otto Stamm : To the Carolingian royal palace in Frankfurt am Main. In: Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute (Hrsg.): Germania. Bulletin of the Roman-Germanic Commission of the German Archaeological Institute. Year 33, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 1955, pp. 391–401.

- Egon Wamers , Archaeological Museum Frankfurt , Architectura Virtualis GmbH: Franconofurd. The Carolingian-Ottonian Imperial Palace Frankfurt am Main. German English. 3D computer reconstruction. DVD video. Architectura Virtualis GmbH, Darmstadt 2008.

- Magnus Wintergerst: Franconofurd. Volume I. The findings of the Carolingian-Ottonian Palatinate from the Frankfurt old town excavations 1953–1993. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 3-88270-501-9 ( Writings of the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt 22/1).

Further reading used

- Ulrich Fischer : Excavation of the old town Frankfurt am Main. One hundred years of urban archeology, prehistory to the high Middle Ages. In: Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum - Research Institute for Pre- and Early History (ed.): Excavations in Germany. Funded by the German Research Foundation 1950–1975. Part 2. Roman Empire in free Germania. Early Middle Ages I. Verlag of the Römisch Germanisches Zentralmuseum commissioned by Rudolf Habelt Verlag, Bonn 1975 ( monographs of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums 1/2), pp. 426–436.

- Andrea Hampel (Hrsg.), Egon Wamers (Hrsg.): Fundgeschichten. Archeology in Frankfurt 2010/2011. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt / Monument Office Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISSN 2192-4244 .

- Rudolf Jung , Julius Hülsen: The architectural monuments in Frankfurt am Main - Volume 3, private buildings. Self-published / Keller, Frankfurt am Main 1902–1914.

- Georg Heinrich Krieg von Hochfelden: The oldest buildings in the Saalhof in Frankfurt a. M .; its fortification and its chapel. In: Archive for Frankfurt's History and Art. Third issue, Verlag der S. Schmerber'schen Buchhandlung (successor Heinrich Keller.), Frankfurt am Main 1844, pp. 1–27.

- Ernst Mack: From the Stone Age to the Staufer City. The early history of Frankfurt am Main. Verlag Josef Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-7820-0685-2 .

- Karl Nahrgang : The Frankfurt old town. A historical-geographical study. Waldemar Kramer publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1949.

- Elsbet Orth: Frankfurt am Main in the early and high Middle Ages. In: Frankfurter Historische Kommission (Ed.): Frankfurt am Main - The history of the city in nine contributions. (= Publications of the Frankfurt Historical Commission . Volume XVII ). Jan Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1991, ISBN 3-7995-4158-6 .

- Guido Schoenberger : Contributions to the building history of the Frankfurt Cathedral. Englert & Schlosser publishing house, Frankfurt am Main 1927 ( writings of the Historisches Museum III ).

- Otto Stamm: The royal Saalhof in Frankfurt am Main. With a preliminary report on the excavations of the Museum of Prehistory and Early History 1958–1961. Waldemar Kramer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1962 (special print from the writings of the Historisches Museum Frankfurt am Main 12).

- Otto Stamm: Late Roman and early medieval ceramics in the old town of Frankfurt am Main. Reprint of the original edition from 1962. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-88270-346-6 ( writings of the Frankfurt Museum for Early and Prehistory 1).

- Otto Stamm: Was there a Staufer Palatinate in Frankfurt? In: State Office for Monument Preservation Hessen (Ed.): Find reports from Hessen. 19th / 20th year 1979/80, self-published by the State Office for Monument Preservation Hesse, Wiesbaden 1980, pp. 819–842.

- Egon Wamers : On the archeology of Frankfurt's old town - the archaeological garden. In: Frankfurt am Main and the surrounding area . Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-8062-0585-X ( Guide to archaeological monuments in Germany 19), pp. 154–159.

- Egon Wamers, Patrick Périn: Queens of the Merovingians. Noble graves from the churches of Cologne, Saint-Denis, Chelles and Frankfurt am Main. Schnell & Steiner publishing house, Regensburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-7954-2689-7 .

- Magnus Wintergerst, Herbert Hagen: High and late medieval ceramics from the old town of Frankfurt am Main. Text and panels. Archaeological Museum Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-88270-343-1 ( Writings of the Archaeological Museum Frankfurt 18/1).

Web links

Remarks

Individual evidence

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 134.

- ↑ Stamm 2002, p. 63.

- ↑ a b Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985–1996, p. 144.

- ↑ Orth 1991, p. 11.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 92.

- ↑ Orth 1991, p. 10.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 19 and 20th

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 38 and 39.

- ↑ a b Wintergerst 2007, p. 20 u. Plan 16.1.

- ↑ Wamers, Périn 2012, p. 163 and 164.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 27 and 28.

- ↑ Wamers, Périn 2012, p. 164 with reconstruction

- ↑ Hampel 1994, pp. 112-152; Findings on the girl's grave.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 30-39; Interpretation of the findings on the girl's grave.

- ↑ Wamers, Périn 2012, pp. 178–180.

- ↑ MGH DD Kar. 1 pp. 236-238; MGH SS 1 p. 35, 36, 45 and 300-302; MGH SS rer. Germ. 6 p. 94 and 95; MGH Capit 1. pp. 73-78; MGH Conc. 2.1 pp. 165-171; Document dated February 22, 794, reports on the arrival, stay and departure of Charlemagne in the Lorsch Annals and the Reichsannals as well as minutes of the Synod (Frankfurt capitular).

- ↑ Fried 1994, pp. 25-34.

- ↑ a b Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985–1996, p. 161.

- ↑ Mack 1994, pp. 106-109.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 40.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 110.

- ↑ Stamm 1955, p. 392.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 47-60.

- ↑ a b c Wamers, Archaeological Museum Frankfurt, Architectura Virtualis GmbH 2008.

- ↑ MGH DD O II / DD O III p. 207 and 208.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 162.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 60-67.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 60-67.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 183-193; Regesten.

- ↑ Mack 1994, pp. 130-138.

- ↑ MGH SS 15.2 p. 1284.

- ↑ Hampel 1994, pp. 62-71.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 67.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 163.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 68.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 71.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 75.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 40–43.

- ↑ MGH DD LD / DD Kn / DD LJ, pp. 357-359; for furnishing with royal property, at the same time the first mention of the monastery.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 360-362.

- ↑ Orth 1991, p. 21 and 22nd

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 190-211; Regesten.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 212; Text passage MGH SS rer. Germ. 50 p. 111.

- ↑ Orth 1991, pp. 18-21.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 335 and 336; Regesten.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 345-347; Regesten.

- ↑ Orth 1991, p. 22 and 23.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 95-98.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 166 and 167.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 42.

- ↑ a b c Stamm 1955, p. 395.

- ↑ Froning 1884, pp. 69, 71 and 72; Quote: "Anno 822 a Ludovico pio extruitur palacium vulgo der Saalhoeff, unde aliquando vocari legimus curtem imperialem."

- ↑ Lersner 1706, Das Erste Buch, p. 17.

- ↑ Lersner 1706, Das Zweyte Buch, p. 112.

- ↑ Boehmer, Lau 1901, p. 23 and 24, Document No. 47, August 15, 1219.

- ↑ Hampel, Wamers 2011, p. 8.

- ↑ Krieg von Hochfelden 1844, pp. 1–27.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 11.

- ↑ Schoenberger 1927, p. 8.

- ↑ Jung, Hülsen 1902-1914, p. 1; Quote: “It may appear doubtful where the palace of Charlemagne was located in Carolingian Frankfurt […], but that the new royal palace built by Ludwig the Pious in 822 took the place of today's Saalhof, can be considered certain . "

- ↑ Stamm 1966, p. 12 and 13.

- ↑ a b Orth 1991, p. 17 and 18th

- ↑ Stamm 1966, p. 13, footnote 95 on p. 59; Quote: “As early as February 1936, Bingemer took up the question of Frankfurt's imperial palace in front of the Association for the Historical Museum. The interpretations of Frankfurt historians are mostly assumptions that lack impeccable evidence. The Saalhof chapel, which has always been regarded as the remnant of a Palatinate of Ludwig the Pious, does not show any Carolingian features. The palace of Charlemagne would be on the site of today's cathedral. Only excavations could produce definitive evidence. "

- ↑ Wintergerst 2002, p. 22.

- ↑ Fischer 1975, p. 427 and 428

- ↑ Stamm 1962, pp. 50-53.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, p. 24.

- ↑ Fischer 1975, p. 430 u. 431.

- ↑ Stamm 2002, plate 30.

- ↑ Wamers 1989, p. 158.

- ↑ The new model of the Imperial Palace Franconofurd

- ↑ Stamm 1955, pp. 393-395 and 398

- ↑ Fischer 1975, p. 430; Footnote 21 on p. 435.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 37; Footnote 65.

- ↑ Schalles-Fischer 1969, p. 90 and 226-228.

- ↑ Schalles-Fischer 1969, p. 200 and 202.

- ↑ MGH SS 1 p. 35 and 36; SS rer. Germ. 6 p. 95.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 150, 151, 155 and 160.

- ↑ MGH DD Kar. 1 p. 239 and 240.

- ↑ a b Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985–1996, p. 156 and 157.

- ↑ MGH Capit 1. p 74; MGH Conc. 2.1 p. 166.

- ↑ Schalles-Fischer 1969, p. 201 and 225

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 157.

- ↑ MGH Conc. 2.1 p. 131.

- ↑ a b Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985–1996, p. 160.

- ↑ MGH SS rer. Germ. 6 p. 142.

- ↑ MGH SS 1 p. 111; MGH SS 2 p. 597 u. 626ff .; MGH SS rer. Germ. 6 pp. 159-162.

- ↑ Schalles-Fischer 1969, p. 227 ff.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Stamm 1955, p. 393.

- ↑ Stamm 2002, p. 85.

- ↑ a b c Wintergerst 2007, p. 59.

- ↑ a b Stamm 2002, p. 85 u. 86.

- ↑ Schalles-Fischer 1969, p. 232 ff.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp 178-326.

- ↑ Orth 1991, p. 25.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 165.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 42 and 43.

- ↑ a b c Stamm 1980, p. 840.

- ↑ Stamm 1966, pp. 33-35, 50 and 51.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 176 and 177.

- ↑ Stamm 1980, p. 820.

- ↑ Binding 1996, p. 345.

- ↑ a b Binding 1996, p. 336 f.

- ↑ Picard 2004, p. 48 and 49.

- ↑ Stamm 1966, pp. 50-53.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 175 and 176.

- ↑ Orth 1991, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ Stamm 1980, p. 836.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, pp. 422, 423, 449 and 450

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 165 and 166.

- ↑ So also: Strickhausen, Gerd: Castles of the Ludowingers in Thuringia, Hesse and the Rhineland. Studies on architecture and sovereignty in the High Middle Ages, Darmstadt and Marburg 1998.

- ↑ Stamm 1962, p. 83 and 84.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 60, 91 and 92.

- ↑ Stamm 1955, p. 394 and 398

- ↑ Mack 1994, pp. 184-188.

- ↑ Hampel 1994, pp. 172-178.

- ↑ Orth, Gockel, Schwind 1985-1996, p. 371 and 372.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 33–37.

- ↑ Wintergerst 2007, pp. 28-30.

Translations

- ↑ "Headquarters of the Eastern Empire", whereby "orientalis regni" means the Eastern Franconian kingdom as distinct from the "regni occidentalis", ie the Western Franconia, which have been understood as independent since the division of Verdun in 843.

- ↑ "Boden und Hof", "curtis" can also be translated as "royal court" or even "Pfalz" in Middle Latin.

Coordinates: 50 ° 6 ′ 38 ″ N , 8 ° 41 ′ 4 ″ E