Kołobrzeg

| Kołobrzeg | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Poland | |

| Voivodeship : | West Pomerania | |

| Powiat : | Kołobrzeg | |

| Area : | 25.67 km² | |

| Geographic location : | 54 ° 11 ' N , 15 ° 35' E | |

| Residents : | 46,309 (June 30, 2019) |

|

| Postal code : | 78-100 to 78-106 | |

| Telephone code : | (+48) 94 | |

| License plate : | ZKL | |

| Economy and Transport | ||

| Street : | DK 11 : Kołobrzeg → Bytom , | |

| Ext. 102 : Międzyzdroje → Kołobrzeg | ||

| DK 163 : Kołobrzeg → Wałcz | ||

| Rail route : | Koszalin – Goleniów | |

| Szczecinek – Kołobrzeg | ||

| Next international airport : | Szczecin-Goleniów | |

| Gmina | ||

| Gminatype: | Borough | |

| Surface: | 25.67 km² | |

| Residents: | 46,309 (June 30, 2019) |

|

| Population density : | 1804 inhabitants / km² | |

| Community number ( GUS ): | 3208011 | |

| Administration (as of 2015) | ||

| Mayor : | Anna Mieczkowska | |

| Address: | ul.Ratuszowa 13 78-100 Kołobrzeg |

|

| Website : | www.kolobrzeg.pl | |

Kolobrzeg ([ kɔwɔbʒεk ] ), German Kolberg ([ kɔlbɛʁk ]), formerly Colberg , is a port city in the Polish West Pomeranian Voivodeship . Kolobrzeg is Sol - and spa on the Baltic Sea . The main economic features of the city with around 46,700 inhabitants (2015) are tourism and the port and fishing industries .

geography

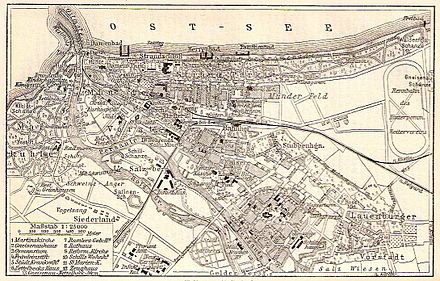

The city is located as a municipality in the north of the powiat Kołobrzeski directly on the Baltic Sea coast, which here has the character of a compensation coast . The Parsęta River flows into Kołobrzeg after 127 km . To the east is Ustronie Morskie (Henkenhagen), to the west and south is the rural municipality of Kołobrzeg , which is not part of the urban area.

The urban area itself extends over approx. 1,800 hectares and includes, in addition to typical urban areas, a river, canal and port area, a coastal area and a varied mosaic of urban parks, nature park areas (e.g. the park in Jedności Narodowej / Park der national unity on the left bank of the Parsęta ) and fallow and meadow areas, some of which have a wet biotope character (e.g. Solne Bagno ).

The voivodeship capital Stettin (Szczecin) is located about 150 kilometers southwest of Kołobrzeg, the nearest larger neighboring town Koszalin (Köslin) is 41 kilometers.

climate

Average temperature over the last 20 years (1990-2010)

| month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum values (during the day) [° C] | 1 | 2 | 6th | 8th | 13 | 17th | 21st | 20th | 16 | 11 | 6th | 3 | 11 ° C (during the day) |

| Lowest values (at night) [° C] | −1 | −1 | 1 | 3 | 7th | 11 | 13 | 13 | 10 | 6th | 2 | 0 | 5 ° C (at night) |

| Number of days with precipitation | 20th | 15th | 15th | 13 | 12 | 12 | 14th | 11 | 14th | 15th | 18th | 19th | 178 |

| Source: Weatherbase.com | |||||||||||||

history

Pomoran predecessor settlement

From the 9th century on there was a settlement that served to exploit the salt springs at the mouth of the Persante. This was first mentioned in Thietmar von Merseburg's chronicle under the name salsa Cholbergiensis - for example: Salz-Kolberg - as the seat of Bishop Reinbern in the year 1000. With his expulsion the diocese went under again a few years later. In 1124 Bishop Otto von Bamberg proclaimed Christianity in Kolberg and inaugurated St. Mary's Church in 1125. When a German city was founded in the middle of the 13th century, the name Kolberg was transferred to it. The old settlement continued to exist under the name of the Altstadt (now also in Polish: Budzistowo ).

From the foundation of the German city to the end of the Duchy of Pomerania

In the course of the German settlement in the east , German settlers settled about 2 km north of the existing Slavic settlement. The result was a place with a regular floor plan and a surrounding wall. In 1248 Duke Barnim I and Bishop Wilhelm Kolberg and Stargard exchanged, which was confirmed in 1255 by the Brandenburg Margraves Johann and Otto. In 1255 the "new" settlement Kolberg received from Duke Wartislaw III. from Pomerania and Bishop Hermann von Gleichen von Cammin the town charter according to Lübischem law . The still existing Wendish city lost its importance in the new city in 1282 after the cathedral chapter was moved in 1287 and the Marienkirche, later the Kolberg cathedral . Later called the old town Kolberg , it was preserved as a village and is now incorporated as Budzistowo . In 1277 Kolberg became part of the Cammin monastery, the secular domain of the bishop. The Hanseatic League belonged to Kolberg already before the first documented mention of the affiliation in 1361 (Hanserecesse vol. 1, no. 259) and remained in this city association until 1610. In this heyday of the city, salt production, salt trade and fishing were the Main sources of income Kolberg and brought great wealth. Since the beginning of the 14th century as a Hanseatic city, Kolberg had its own minting right, which was confirmed by Emperor Charles V in 1548 when the city paid homage to him.

The first traces of Jewish citizens can be found in 1261, and from the 14th century onwards, some Jewish families settled in ul.Brzozowa (formerly: Judenstrasse ). In 1492/93 most of the Jewish population was expelled after the Sternberg host-molester trial. Jews who were baptized were allowed to stay temporarily, but had to live in the Jewish quarter between ul. Gierczak and ul. Narutowicza (formerly: Lindenstrasse and Schlieffenstrasse) and ultimately had to leave the city in 1510 as well. The German name Enge Judengasse was a reminder of this ghettoization . Until 1812, Kolberg was the only town in Western Pomerania besides Tempelburg in which the permanent settlement of Jews was prevented by the magistrate and, after protests, by Christian merchants. Jews were allowed to trade with a license, but they had to leave the city after 24 hours at the latest.

In 1442 there was a conflict between the bishop of Cammin Siegfried II. Bock and Kolberg, as a result of which this the city in an alliance with the Duke Bogislaw IX. besieged. Siegfried II had pledged various uplifts, leases and other sources of income to the city. When he made claims to the saltworks and the harbor, an open conflict broke out, which continued until 1468 during the period in office of Siegfried's successor, Henning Iven . Kolberg successfully fended off all attacks.

From 1530 the Reformation was introduced in Kolberg , 1534 the Catholic institutions in the city were abolished by a resolution of the city council.

In the 17th century Kolberg was depopulated by the plague and the Thirty Years' War with its effects. In 1627 imperial troops occupied the city and fortified it. In 1631 the Swedes conquered Kolberg after a five-month siege.

Kolberg in Brandenburg-Prussia

See also: Colored postcard

Western Pomerania and with it the city of Kolberg came to Brandenburg-Prussia with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 , but was only issued by the Kingdom of Sweden in 1653 after the Szczecin border recession was agreed . In the year 1653, the highest regional authorities for the now Brandenburg-Brandenburg were established in Kolberg, including the new Pomeranian government , the chamber, the court court and the Pomeranian and Camminian ecclesiastical consistory . Also in 1653, relatively late, Kolberg received its first printing press. In 1669 the state authorities were relocated from Kolberg to Stargard in Pomerania .

In the Seven Years' War , in which Pomerania was a secondary theater of war, the Kolberg fortress was successfully defended against the Russians in 1758 and 1760 by the Prussian troops under Colonel Heinrich Sigismund von der Heyde . When a protective occupation army under Friedrich Eugen had withdrawn from Württemberg due to a famine during the four-month third siege , Heyden had to hand over the fortress to the Russian general Pyotr Alexandrovich Rumjanzew-Sadunaiski in December 1761 . Kolberg only recovered after 1800 from the severe destruction, the decline in the number of inhabitants from over 5000 to under 4000 and the loss of all 40 merchant ships.

During the Fourth Coalition War , Kolberg was besieged in 1807 by Napoleon's troops . Defended by the commandant Gneisenau , the Freikorpsführer Schill and the citizens around the citizen representative Nettelbeck , the fortress lasted until the peace agreement . This success soon became a legend that took on various forms in the political power play of the 19th and 20th centuries. It was last used in 1944 as a template for the National Socialist propaganda film " Kolberg ". In 1812 the fortress watch ship Colberg was put into service here, which remained the only one of its kind until it was decommissioned in December 1813.

After the reorganization of the district structure in the Prussian state, Kolberg was from 1816 in the Fürstenthum district in the administrative district of Köslin in the province of Pomerania . With the dissolution of the principality district on September 1, 1872, Kolberg became the district town of the newly created Kolberg-Körlin district . District administrator was Robert von Schröder .

With the Jewish edict of 1812 , the living conditions of the Jews in Kolberg had improved and they were allowed to settle again. After the foundation stone for the synagogue was laid in 1844 at 28 Baustraße (after 1945 ul. Budowlana ), it was inaugurated a year later. The building was replaced by a new building around 1900. From approx. 1865 to 1925, Dr. Salomon Goldschmidt Rabbi von Kolberg.

Well-known personalities such as Adam Heinrich Dietrich Freiherr von Bülow (from October 1806 to May 1807), Friedrich Ludwig Jahn ( gymnastics father Jahn ), Arnold Ruge and Martin von Dunin served their imprisonment in Kolberg . Kolberg was a fortress until 1872, but remained a garrison town.

In 1891 the spelling of the city with K = Kolberg, which had been naturalized for decades, became official. On May 1, 1920, the municipality of Kolberg left the Kolberg-Körlin district and has since formed its own urban district .

The 19th and early 20th centuries were characterized by a long economic boom, which was mainly based on spa tourism. In 1919, from February 11 to July 3, Kolberg was the last seat of the Supreme Army Command under Paul von Hindenburg and Wilhelm Groener .

As of 1932, there were the following 19 residential spaces in the Kolberg district in addition to the city of Kolberg itself : Am Kautzenberg , Am Ostseestrande , Bohlberg , Elysium , Erdmannshof , Forsthaus Malchowbrück , Gastwirtschaft Kautzenberg , Hanchenberg , Heinrichshof , Karlsberg , Maikuhle , Malchowbrück , Neugeldern , Ringenholm , Schülerbrink , Stadtfeld , municipal peat bog near Gribow , Waldenfelsschanze and Wickenberg .

Kolberg at the time of National Socialism

After 1935, several barracks complexes were built in Kolberg as part of the armament of the Wehrmacht , including the Kolberg air base . During the Second World War the capacities of the torpedo school in Flensburg - Mürwik were no longer sufficient. Another torpedo school was set up in Kolberg in October 1941, but it was still under Flensburg-Mürwik.

During the Reichspogromnacht the New Synagogue, which opened in 1899, and all Jewish shops were completely destroyed. The Jewish sanatorium was dissolved and subsequently converted into a coal shop, the synagogue was converted into a hardware store and most of the Jewish men were taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for a few months and abused there. On 12./13. In February 1940 a surprise action followed in which 1,200 Jews from Pomerania and Kolberg were deported to the General Government of Poland . Finally, the German authorities ended Jewish life in Kolberg in 1942 after almost all of the remaining Jewish residents had been deported to extermination camps. The synagogue and the adjacent street were completely destroyed in the fighting for the city in 1945 and residential buildings were built on in the post-war period. Thus, after the pogrom night from 1940 to 1942, the entire Jewish population was deported and most of them were murdered.

In the further course of the Second World War, after great initial successes in Poland and Soviet Russia, German troops were on the retreat from 1943. When the Soviet troops were on the eastern border of Germany, Adolf Hitler declared Kolberg to be a permanent place in November 1944 . At the end of January 1945, in the Vistula-Oder operation , the Red Army separated northern Pomerania from the interior with its major attack on Berlin. On February 14, 1945, Colonel Fritz Fullriede became the city's commander . In the second stage of the battle for East Pomerania , the 1st Belarusian front, operating to the northwest, advanced against Kolberg and the 2nd Belarusian front against Koslin . On March 5, Koslin was conquered and the Baltic Sea reached, thereby dividing the German front.

From March 10, 1945, the troops of the 1st Belarusian Front controlled the Baltic coast from Kolberg to the mouth of the Oder . Kolberg had been besieged since March 4th and lasted until March 18th. In the meantime, almost the entire population and many refugees (over 70,000 people) had been evacuated by sea. Soviet and Polish troops occupied the city, which was over 90 percent destroyed.

After the Second World War

In May 1945 only about 2200 Germans lived in Kolberg, most of whom were later expelled . These deportations took place on the basis of the decisions of the Allies at the Potsdam Conference . The expulsion and previous expropriations were carried out by ordinances of the Polish state called Bierut decrees by the German expellees' associations .

In 1945 the city was renamed Kołobrzeg and settled by Poles, partly by (forcibly) resettled Poles from the previous eastern parts of the country. With this settlement, the city was rebuilt with the completely destroyed infrastructure.

After the Second World War , many citizens of Kołobrzeg and especially the members of the Polish Home Army were subjected to reprisals during the Stalinist era.They were abducted by members of the NKVD in Gulags and some were murdered there because some of them were both German and fought the Soviet troops. There is a memorial in their honor in the city cemetery.

In 2000, the city administration of Kolberg set up a German lapidarium with the German gravestones that can still be found to commemorate the former German population, which was inaugurated with the participation of the German home district. A little later a Jewish lapidary was set up. Since 2000, Polish and German war veterans have been commemorating their victims together on the anniversary of the “end of the fighting for Kolberg” on March 18, 1945. In March 2005, on the initiative of the Polish veterans, a trilingual book of honor was published for the Soviet, Polish and German soldiers and Volkssturmmen who died in Kolberg.

In the 2010s, many spa hotels were built in the spa district, separated from the Baltic Sea by a narrow forest belt, now over 20 facilities. The numerous spa guests and tourists come mainly from Scandinavia and Germany.

Development of the population

After the demolition of the ramparts, the population had almost doubled to over 20,000 by 1900. In the 19th century a Polish and Jewish minority emerged in Kolberg, whose share in 1900 was 2% and 1.5%, respectively.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Brine springs

Kołobrzeg has sources containing vitriol with a relatively weakly saturated approx. 6 percent brine - in Lüneburg , for example, saturated brine with 25 percent salt content is obtained. The salt production led to the settlement of the place and was the basis for the later wealth of the city. Have the former German town or street names as the history of Kolobrzeg Kolberg or as a salt city Salzberg , boilers country , Gradierstraße and Pfannschmieden out. The salt springs and the salt production facilities were initially located on both sides of the Parsęta, later the salt was mainly extracted on the salt island . This is surrounded by the main course of the Parsęta and the Kanał Drzewny (wooden canal). In a description of the 18./19. Century they were located as follows:

“The salt springs… are in front of the Münder Thore on the Zillenberg, on this side of the Persante, close together. Not far from the mouth of the port there are 17 boiling and 8 desolate koths on the mountain of salt, together with a general boiling house, of which a boiling kothe with a pan 4600 Rthlr. and a desert Kothe 1800 Rthlr. is appreciated. "

Around the year 1000 Colberger salt was supra-regional a. a. sold to Poland, as own demand was low. From the 12th century, the salt pans and pans were lent to church institutions by the Pomeranian dukes. The monasteries initially transported the salt for their own use, while later they ceded their salt righteous persons in exchange for money and they thus came into the hands of the bourgeoisie. From 1255 the supervision and operation of the saltworks was transferred to the council and the citizens. In the 15th century, Kolberg salt was exported both by sea to the neighboring coastal strips and by land and river to Poland, the Pomeranian hinterland, the Neumark and the Mark Brandenburg . In 1473, residents of Rügenwalde (today: Darłowo ), Stettin, Stargard , Schivelbein (today: Świdwin ), Belgard (today: Białogard ) were financially involved in the salt pans, as noted in the manure book and the city book.

The springs were no longer intensively exploited at the beginning of the 19th century because of their relatively low salt content, the resulting high demand for wood and its lack for boiling salt and the competition with rock salt . Since the 1990s there has been a stone-framed spring on the salt island, from which the brine flows out of a metal pipe.

Culture and sport

Regional cultural center

The city's regional cultural center ( Regionalne Centrum Kultury w Kołobrzegu ) at Teatralny Park organizes events from various cultural areas. Exhibitions take place in the center building, which also houses a café and internet café. The adjacent covered stage area is used for music concerts, smaller theater or comedy performances.

music

Since 2003, the Sunrise Festival has been held at the end of July, which is dedicated to a rave according to electronic music and takes place in the Amfiteatr , on the promenade and directly on the beach.

Sports

The city has two larger sports halls, which are grouped under the term Milenium sports halls : The knight's hall for basketball and volleyball is located in the center of Kołobrzeg, the sports and event arena MILENIUM offers 1,306 seats, commentary spaces as well as technical and sanitary facilities Facilities that enable local and international trade fairs, exhibitions, concerts, cultural events as well as celebrations and performances.

The professional basketball team Kotwica Kołobrzeg is based in Kołobrzeg . The club has played in the highest Polish league since 2005 .

Every year in June a triathlon (or a duathlon ) is organized, which is sponsored by the Polish energy supplier Enea and marketed as Enea Tritour . The start and finish is at the city's lighthouse. Around 400 participants took part in 2015.

Kołobrzeg is a possible end point for canoe tours on the Parsęta and can be a stop for coastal paddling on the Baltic Sea.

From 1921 to 1945 the sports club Viktoria Kolberg existed in Kolberg .

Between 1926 and 1929, the Kolberg bathing race , which was one of the most important motorcycle races in Germany at that time , was held four times around Kolberg .

Museums

In the Museum of the History of the City of Kołobrzeg , which is housed in the Braunschweigschen Haus , archaeological finds are exhibited which come from excavations in the city and the predecessor settlement Budzistowo . Topics are the settlement of Kolberg with the exploitation of the salt springs, the history of the Kolberg fortress and the development of the city into a health resort. One floor is dedicated to exhibits from seven centuries of German city history that were found during the reconstruction. In addition, other changing exhibitions are presented.

The exhibition of the Museum of the History of the Polish Army and Polish Arms documents the development of the Polish Army from the Piasts to the end of the Second World War. The museum's collection presents military technology in a hall and in an open-air area, including aircraft and a tank. A copy of the German Enigma encryption machine is also on display.

The Gothic town house from the 15th century is only used temporarily as a museum and for the presentation of exhibitions. It mainly serves as a research facility and warehouse.

On the salt island there is a small open-air museum with a warship and other military technology.

The Natural Stone Museum is located in the basement of the Kołobrzeg lighthouse . Natural stone exhibits from Morocco, Russia, Brazil and Madagascar are on display there.

Religions

Christian churches

history

The old Slavic settlement Alt-Kolberg (today Budzistowo ) was the seat of the first Bishop Reinbert in Pomerania in the year 1000. Its existence, however, only lasted about five years. After the Pomeranian mission in 1124/25 several new churches were built there, including a new cathedral with collegiate monastery and the Johanneskirche, which has been preserved to this day

Today's city of Kolberg, about two kilometers to the north, received town charter in 1255. In the period that followed, a new cathedral (mentioned in 1282), a Nikolaikirche, a Benedictine monastery and a Heilig-Geist-Hospital, later also a Georgen and a St. Gertrud Hospital, were built there.

The Reformation was introduced in Kolberg in 1531, and in 1534 all Catholic institutions were dissolved or converted into Protestant ones, such as the Benedictine monastery into a Protestant women's monastery. The cathedral church and the churches of St. Nikolai, St. Georgen, St. Spiritus and St. Gertraud have been preserved. In 1630, some churches were destroyed or damaged in the Thirty Years War, but then rebuilt. After the city of Kolberg was handed over to Brandenburg-Prussia, the women's collegiate church was converted into a garrison church for the military and a reformed church was created. In 1758 and 1807, further damage to church buildings took place during sieges.

In 1895 the Catholic Church of St. Martin was built, in 1929 a church for Old Lutherans and in 1932 another Protestant church, the Church of the Redeemer .

When the old town was completely destroyed in 1945, only the remains of the cathedral, the garrison and the Redeemer Church remained. These were converted into Catholic churches in 1945 and 1949, and a Franciscan convent was established. In 1974 the cathedral ruins were handed over to the Catholic Church and repaired by it, in 1986 it was elevated to a minor basilica , and after 2000 to a co-cathedral of the Koszalin-Kołobrzeg diocese.

Today's churches

Today there are eight Catholic churches and chapels in Kołobrzeg, one Greek Catholic church, as well as three evangelical free church communities and Jehovah's Witnesses.

- Mariendom , built around 1300, today a co-cathedral, with valuable medieval works of art

- Church of the Exaltation of the Cross , built in 1932, first Church of the Redeemer

- St. Matthias Church

- Church of Divine Mercy

- Church of the Conception of the Virgin Mary on the Persante, built in 1832 as a garrison church

- Church of Mary the Protection, Greek Catholic

Jewish community and population

history

The first traces of Jewish citizens in Kolberg can be found in 1261, and from the 14th century onwards, several Jewish families lived in the Judenstrat (today ul. Brzozowa ). In 1492/93 most of the Jewish population was expelled after the Sternberg host-molester trial. Jews who were baptized were allowed to stay temporarily, but had to live in the Jewish quarter between what would later become Lindenstrasse and Schlieffenstrasse (today ul. Gierczak and ul. Narutowicza ) and ultimately had to leave the city in 1510 as well. The German name Enge Judengasse was a reminder of this ghettoization .

In the following centuries Jews were no longer allowed to stay permanently in Kolberg. They could do business, but had to leave the city no later than 24 hours. Until 1812, Kolberg was the only city in Western Pomerania besides Tempelburg in which the permanent settlement of Jews was prevented by the magistrate and, after protests, by Christian merchants.

With the Jewish edict of 1812 , the living conditions of the Jews in Kolberg had improved and they were allowed to settle again. After the foundation stone for the synagogue was laid in 1844 at 28 Baustraße (today ul. Budowlana ), it was inaugurated a year later. The building was replaced by a new building around 1900. From approx. 1865 to 1925, Dr. Salomon Goldschmidt Rabbi von Kolberg.

From 1935, access to the seaside resorts was made more difficult for Jews. In 1938, the synagogue was destroyed during the pogrom night and numerous male Jews were deported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. After further transports, in 1942 there were only seven Jewish residents in the city who lived in mixed marriage .

More Attractions

Buildings

The old town was almost completely destroyed in 1945. Very few buildings have survived. With the redesign of the inner city from 1975 there was a turning point in building policy. An architect designed an overall concept that was to represent a city that had "grown" over the centuries, with building fronts and gables of different styles - instead of larger prefabricated buildings . The few buildings that have not yet been destroyed were included in the “city composition”.

- The Braunschweigsche Haus is named after the respected Kolberg council family from Braunschweig. It was built in the middle of the 17th century by the Plüddemann family of merchants and shipowners and was rebuilt in 1808. Today it serves as the city museum with an exhibition on the city history of Kolberg.

- The medieval match tower (powder tower) was used to store gunpowder.

- The town hall was built from 1829 to 1831 by Ernst Friedrich Zwirner based on a design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel , including the remains of the previous Gothic building that was destroyed in 1807. The monument to King Friedrich Wilhelm III erected in front of the town hall in 1860 . von Friedrich Drake was eliminated after 1945.

- The Kołobrzeg lighthouse was one of the first buildings to be rebuilt after the Second World War and is now a symbol of the city. It is located on the remains of an old fort to defend the port of Kolberg, formerly the independent town of Kolbergermünde , and on the site of the old pilot's office. In the basement of the lighthouse there is a private museum for minerals and rocks.

- The 220 meter long Kolberger Seebrücke is the second longest concrete bridge in Poland. It was reopened in 2015 after complete renovation.

- The monument to the marriage of Poland to the sea on the promenade between the lighthouse and the pier was unveiled in 1963. It commemorates the symbolic marriage to the sea after the city was conquered on March 18, 1945.

Cemeteries and memorials

- In addition to the Christian graves, the municipal cemetery (in Polish : Cmentarz Komunalny ) contains various memorials: for the Jews deported during the National Socialist era, for the Soviet soldiers who died in the battle for Kołobrzeg and for the Poles and members of the Poles who were deported during the Stalinist era Polish resistance movement.

- The old Jewish cemetery was located in what is now Teatralny Park from 1812 until it was destroyed in the Night of the Reichspogrom in 1938 . Today, a few tombstones have been re-erected there in a lapidarium and a memorial stone has been erected for the former Jewish community that was deported to the Bełżec extermination camp in 1940 and murdered.

- The new Jewish cemetery was located in ul. Koszalińska (formerly: Kösliner Strasse) and was also devastated in 1938 during the Night of the Reichsspogroms.

Infrastructure and economy

traffic

In Kołobrzeg, many infrastructure projects have been implemented with funds from the European Union since 2004. These include the access and urban roads, bridges over the Parsęta and the Drzewny Canal , the beach paths, the port facilities and the cycle paths.

Kołobrzeg is located on the national road 11 as well as the provincial roads 102 and 163.

There are rail connections to Szczecin , via Koszalin ( Köslin ) to Danzig and via Białogard ( Belgard ) to Szczecinek ( Neustettin ). With the Pendolino there is a connection via Słupsk , the Trójmiasto (Gdynia, Sopot, Danzig), Malbork and Warsaw to Krakow , the journey time is around 8.5 hours. From 1895 until the 1960s, the Kolberger Kleinbahn (KKB) connected the surrounding area with the city.

There is a ferry connection from Kołobrzeg harbor to Nexø on the Danish island of Bornholm , which runs daily in the summer months.

The Baltic Sea Cycle Route (EuroVelo 10) (Polish: Międzynarodowy szlak rowerowy wokół Bałtyku R-10 ) runs through Kołobrzeg . The BTBP1 ( Bike the Baltic - Pomerania 1 ) begins or ends here as a regional cycle path.

The nearest airports are Koszalin Zegrze Airport, approx. 44 km away, and Szczecin-Goleniów Solidarność Airport, approx. 80 km away . The former military airport in Bagicz, about 9 km away (Polish: Lotnisko Kołobrzeg-Bagicz ) is only partially used for private sport aviation, some hangars are rented out, others are in ruins.

Port and fishing industry

The port of Kołobrzeg handled a total of 117,309 tons of goods in 2013, compared to 170,608 tons in 2012. Wood, including pellets and wood chips, accounted for the largest share at 69 percent . In 1848 there were 19 merchant ships in the port of Kolberg, in 1929 998 ships were in service in the port of Kolberg; the cargo turnover was 111,127 tons.

In the extended eastern port area, there are several excursion boats modeled on pirate ships that offer touristic tours off the coast. A light warship is set up as a museum.

The catch from the fishing cooperative's fleet is marketed directly in the port and includes both fresh and locally prepared smoked fish. A factory in the port produces ice for refrigerated transport in trucks and for use in larger fishing vessels .

The marina was modernized by the West Pomeranian Tourist Association with funds from the European Union by the end of 2011 . Another area between the yacht and fishing port was newly developed with additional boat and yacht berths by 2015.

Shortly before the mouth of the Parsęta, part of the port on the western side is a naval port (Polish: Port wojenny ) and a restricted military area. As a rule, light warships of the 8th Coast Guard Flotilla (Polish: Flotyllę Obrony Wybrzeża ) of the Polish Navy are located here , which serve to defend the coast.

tourism

Because Kolberg has been since the 19th century. was both lake and moor and brine baths and the care of the guests reached a high level, it developed into one of the largest German Baltic Sea baths by 1933 . Most of the visitors came from Berlin and central and eastern Germany. The proportion of Polish-speaking visitors from Austria and Russia was also relatively high at (estimated) 5–8%. For these visitors there were Catholic church services (held in St. Martin) in their language, initially during the season and from around 1890 all year round. In 1904 13,288 spa guests were counted.

From 1933, at the time of National Socialism, tourism was mainly limited to guests within the framework of the organization Kraft durch Freude , which aimed to organize an ideologically motivated leisure or vacation.

Since the end of the 20th century, tourism in Kołobrzeg has been the strongest economic branch, especially in the summer months: a large number of accommodation in all categories is available to guests and there is a wide range of tourist attractions.

education

A cathedral school was first mentioned in Kolberg around 1300, possibly before 1250. It later developed into a lyceum and existed as the Kolberg cathedral high school until 1945. Associated with this was a first-class secondary school and a secondary school for girls .

Until 1854, one of the fifteen garrison schools of the Prussian Army was located in the city . This was temporarily closed in 1854 due to insufficient use and the good condition of the Kolberg civil school, but reopened later; around 1867 she was visited by 260–270 children of both sexes.

In the 21st century Kołobrzeg has six primary schools, several secondary schools (Polish: Gimnazja) and technical schools for the fields of technology, economy / hotel industry, social affairs and (maritime) shipping. There are also vocational schools (Polish: Szkoły policealne) for economics / health management, business administration and an art college for music.

Since 2005, the two-day media education conference Od Becika Każdy Klika (freely translated: 'From diapers to computer mice') has been taking place in Kołobrzeg every year since 2005. It offers teachers of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship advanced training, primarily in the field of digital media. Those from the Technical School Zespół Szkół No. 1 ?? in the. Henryka Sienkiewicza w Kołobrzegu ( Henryk Sienkiewicz Community School ) is under the auspices of local and regional politicians and sponsored by companies primarily in the fields of education and technology.

Personalities

The list of personalities of the city of Kołobrzeg includes people born in the city as well as those who had their sphere of activity in Kołobrzeg.

Twin cities

- Bad Oldesloe , Schleswig-Holstein

- Barth , Northern Pomerania

- Pankow district , Berlin

- Koekelberg , Brussels

- Feodosia , Crimea

- Follonica , Tuscany

- Landskrona , western Skåne

- Nexø , Bornholm

- Nyborg , Funen

- Pori , Finland

- Simrishamn , Eastern Skåne

literature

- anonymous: Memories of the three sieges of Colberg by the Russians in 1758, 1760 and 1761 . Frankfurt / Leipzig 1763 ( full text )

- Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann : Detailed description of the current state of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Part II, Volume 2: Description of the to the judicial district of the Royal. State colleges in Köslin belonging circles . Stettin 1784, pp. 462–497 ( full text, without folded plates ).

- Hans-Jürgen Eitner: Kolberg. A Prussian myth 1807/1945 . Berlin 1999.

- Ulrich Gehrke: 50 years ago: Kolberg 1939 - last season in peace. Messages, reports and advertisements from the Kolberger Zeitung from May to September 1939, supplemented by 44 illustrations and photos . Hamburg 1989.

- Peter Jancke: Kolberg. Guide through a lost city. Contributions to the history of the city of Kolberg and the Kolberg-Körlin district, Volume 34. Husum Verlag, Husum 2007, ISBN 978-3-89876-365-3 .

- Gustav Kratz (editor): The cities of the province of Pomerania. Outline of their history, mostly based on documents. Introduction and preface by Robert Klempin . Berlin 1865, pp. 81-99 ( books.google.de ).

- Heinrich Berghaus : Land book of the Duchy of Pomerania and the Principality of Rügen . Part III, Volume 1. Anklam 1867, pp. 39-162 ( books.google.de ).

- Ostseebad Kolberg . In: Unser Pommerland , vol. IX, H. 6.

- Peter Johanek , Franz-Joseph Post (ed.); Thomas Tippach, Roland Lesniak (edit.): City book of Hinterpommern. Deutsches Städtebuch, Volume 3, 2. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-018152-1 , pp. 116–129.

- Hieronym Kroczyński: Dawny Kołobrzeg. The old Kolberg . Wydawnictwo Le Petit Café, Kołobrzeg 1999.

- Gottfried Loeck, Peter Jancke: Kolberg on old maps. Views and city maps from seven centuries. Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-927996-40-3 .

- H. Riemann: History of the city of Kolberg. Illustrated from the sources . Kolberg 1924.

- Szczecin State Archives - guide through the holdings up to 1945 (edited by Radosław Gaziński, Pawel Gut and Maciej Szukała). Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-486-57641-0 , pp. 302-308 ( books.google.de ).

- Johannes Voelker: The last days of Kolberg (March 4th – 18th, 1945) (= East German contributions from the Göttingen working group; vol. 12th Göttingen working group: publication no. 190). Holzner, Würzburg 1959.

- Johann Friedrich Wachse : Historical-diplomatic history of the old town Kolberg . Hall 1767 ( books.google.de ).

- Johann Ernst Fabri : Geography for all classes . Part I, Volume 4. Leipzig 1793, pp. 507-518 ( books.google.de ).

- Manfred Vollack : The Kolberger Land - Its cities and villages - A Pomeranian homeland book . Husum 1999, ISBN 3-88042-784-4 .

- Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Province of Pomerania - city and district of Kolberg-Körlin. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- Rudolf Benl, Origins and Beginnings of the City of Kolberg , In: Baltic Studies , NF 100 (2014), pp. 7–30.

- Dirk Schleinert : The city and the salt. Sources on the Kolberger Saline in the State Archive of Saxony-Anhalt , In: Pommern. Zeitschrift für Kultur und Geschichte, 43rd vol. (2005), no. 4, pp. 11-21.

Ludwig Biewer : Kolberg - a Hanseatic city in Western Pomerania. Thoughts on the history of a European cultural landscape, In: Pommern. Zeitschrift für Kultur und Geschichte, 43rd vol. (2005), no. 4, pp. 2–10.

Web links

- Website of the City of Kołobrzeg

- History and genealogy of the city and the Kolberg district

- Kolberger Strasse 1584, 1865, 1916–1939

- Bibliography on the history of the city near Litdok East Central Europe / Herder Institute (Marburg)

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b population. Size and Structure by Territorial Division. As of June 30, 2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny (GUS) (PDF files; 0.99 MiB), accessed December 24, 2019 .

- ↑ The work of the surf - Processes on the coast Exogenous processes in connection with the design of landscape; accessed on March 5, 2015.

- ^ Heinrich Gottfried Philipp Gengler : Regesta and documents on the constitutional and legal history of German cities in the Middle Ages . Erlangen 1863, p. 609 ff.

- ^ The Recess and other files of the Hanseatic Days from 1256 - 1430, Volume 1 (Hanseatic Days from 1256 - 1370), Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1870 (digitized: State and University Library Hamburg)

- ↑ Location of ul. Brzozowa, inhabited by Jews, on Openstreetmap

- ↑ A short Jewish history of the Baltic resort of Kolberg , published on December 6, 2012; Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area ; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ^ Kolberg - Description in the Jewish Virtual Library (English); accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ^ Hellmuth Heyden: Church history of Pomerania. Volume 1, 1937, pp. 258-259.

- ↑ Martin Wehrmann : History of Pomerania. Volume 2. 2nd edition. Verlag Friedrich Andreas Perthes, Gotha 1921, p. 169. (Reprint: Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-112-6 ).

- ↑ Jakob Franck: Kuse, Jakob . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 17, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, p. 433 (mentioned in the article on the printer Kuse).

- ↑ Martin Wehrmann: History of Pomerania. Volume 2. 2nd edition. Verlag Friedrich Andreas Perthes, Gotha 1921, p. 182. (Reprint: Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-112-6 ).

- ↑ Karl von Sulicki : The Seven Years' War in Pomerania and in the neighboring Marche. Study of the Detachment and the Little War . Mittler, Berlin 1869 ( full text ).

- ↑ See e.g. B. Johann Gottlieb Tielke: Contributions to the art of war and the history of the war from 1756–1763 . Part II: The campaign of the Imperial Russian and Royal Prussian peoples in 1758 . Vienna 1786 ( full text, without folded plates ).

- ↑ Hans von Held : History of the three sieges of Kolberg in the Seven Years' War . Berlin 1847, books.google.de .

- ↑ Old Synagogue in Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Description on sztetl.org.pl; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area ; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ^ Entry "Kolberg" in the private information system Pomerania.

- ↑ Georg Tessin : Associations and troops of the German Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS 1939–1945, torpedo services in the Navy

- ^ Entry "Kolberg" in the online work by Klaus Dieter Alicke: From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area.

- ↑ New Synagogue of Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) on Budowlana Street ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on sztetl.org.pl; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ^ The importance of March 18 for Kołobrzeg

- ↑ No. 62: Combat operations during the siege of Kolberg and evacuation of the population ( Memento of November 17, 2012 in the Internet Archive ). Reports on the website of the Center against Evictions ; accessed on March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Manfred Vollack : The Kolberger Land - Its cities and villages - A Pomeranian home book . Husum 1999, ISBN 3-88042-784-4 , p. 34.

- ↑ Kroczyński (see bibliography) cites the 1905 census, p. 52.

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack : Brief historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal Prussian duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1793, p. 575.

- ↑ Ludwig Wilhelm Brüggemann : Detailed description of the current state of the Royal Prussian Duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Part II, Volume 2, Stettin 1784, p. 463.

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack : Short historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal-Prussian duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1793, p. 737.

- ↑ Christian Friedrich Wutstrack : Addendum to the short historical-geographical-statistical description of the royal Prussian duchy of Western and Western Pomerania . Stettin 1795, p. 204 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area

- ^ A b Heinrich Berghaus : Land book of the Duchy of Pomerania and the Principality of Rügen . Part III, Volume 1, Anklam 1867, p. 48.

- ↑ a b c d Heinrich Berghaus : Land book of the Duchy of Pomerania and the Principality of Rügen . Part III, Volume 1, Anklam 1867, pp. 62-65.

- ↑ Gustav Kratz : The cities of the Prince of Pomerania - Outline of their history, mostly according to documents . Berlin 1868, p. 94 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Pomerania - Kolberg district. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition, 1st volume, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna, 1908, pp. 257–258.

- ↑ Description of the city's history on kolobrzeg.de; Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ↑ a b Dieter Kausche: Kolberger Salt and its sales in the Middle Ages as a research problem - in: Society for Pomeranian History, Antiquity and Art (ed.): Baltic Studies ; Vol. 64; 1978; Publishing house Christoph von der Ropp; Pp. 7-17.

- ^ Settlement and economy in the "Germania Slavica" - in: Winfried Schich: Economy and cultural landscape - collected contributions 1977 to 1999 on the history of the Cistercians and the "Germania Slavica" ; BWV publishing house; 2007; Pp. 283/284.

- ↑ Schich, Neumeister: Economy and cultural landscape; collected contributions from 1977 to 1999 on the history of the Cistercians and the 'Germania Slavica'; BWV Verlag, 2007; P. 285; describes the location 'on the eastern Persanteufer, near the Nikolaikirche'.

- ↑ a b Oeconomische Encyclopädie (1773–1858) by JG Krünitz Digitized online edition of the encyclopedia on the pages of the University of Trier ; Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ↑ Location of the brine source on the salt island; Link to Openstreetmap

- ↑ Current program of the regional cultural center of the city ( Regionalne Centrum Kultury w Kołobrzegu ) ; accessed on June 23, 2015.

- ^ The Sunrise Festival in Kołobrzeg on kolberg-cafe.de ; Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Description of the Milenium sports halls on kolobrzeg.de; Retrieved March 3, 2015

- ↑ Information on the triathlon taking place in June ; accessed on June 22, 2015.

- ↑ The Triathlon in Kołobrzeg , pictures and information on gk24.pl (Polish); accessed on June 22, 2015.

- ↑ Location of ul. Brzozowa, inhabited by Jews, on Openstreetmap

- ↑ A short Jewish history of the Baltic resort of Kolberg , published on December 6, 2012; accessed on January 21, 2020.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area ; accessed on January 21, 2020.

- ^ Kolberg - Description in the Jewish Virtual Library (English); accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Old Synagogue in Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Description on sztetl.org.pl; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ↑ From the history of the Jewish communities in the German-speaking area ; accessed on January 21, 2020.

- ↑ New Jewish Cemetery in Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on sztetl.org.pl; accessed on March 4, 2015.

- ↑ Opening of the harbor bridge in February 2015 - video on YouTube ; Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ↑ Departure times and route information for the Pendolino connection Kołobrzeg-Krakow

- ↑ Overview of the Polish, supraregional cycle paths in the Baltic Sea coast area ( memento of the original from March 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English); accessed on March 5, 2015.

- ↑ Cargo handling in the ports of Kołobrzeg and Darłowo ( Memento of the original from June 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Polish); accessed on June 22, 2015.

- ^ E. Wendt & Co. (Ed.): Overview of the Prussian Merchant Navy . Stettin January 1848, p. 5 ( online [accessed June 4, 2015]).

- ^ Description of the marina on the municipal website kolobrzeg.de ; accessed on February 23, 2015.

- ↑ Dr. von Bünau : Rules for using the Sool. and seaside resorts based on the latest experience and with special attention to the Colberg pool and seaside resort . Colberg 1852 ( full text ).

- ↑ Nestor Girschner : The Baltic Sea and the seaside resorts on its German coast with special consideration of Colberg and its surroundings, its brine and seaside baths . With a postscript by Hermann Hirschfeld : What offers and does Colberg as a spa resort, and in which diseases is it recommended above all other baths? Colberg and Dramburg 1868 ( full text ).

- ↑ Overview of the accommodation in the city

- ↑ Arwied von Witzleben: military affairs and infantry service of the Royal Prussian Army . 4th edition, Berlin 1854, pp. 45-46.

- ^ Prussian House of Representatives, Negotiations of the Second Chamber on the Highest Order of November 14, 1854. Volume 3, Part 1, File No. 53, Berlin 1855, p. 195, left column below - right column above.

- ↑ Website of the teachers' conference Od becika każdy klika , accessed on February 3, 2017

- ^ Website on the organization, patronage and sponsors of the conference , accessed December 21, 2018