Krimml

|

Krimml

|

||

|---|---|---|

| coat of arms | Austria map | |

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| Country: | Austria | |

| State : | Salzburg | |

| Political District : | Zell am See | |

| License plate : | ZE | |

| Main town : | Oberkrimml | |

| Surface: | 169.46 km² | |

| Coordinates : | 47 ° 13 ' N , 12 ° 10' E | |

| Height : | 1067 m above sea level A. | |

| Residents : | 830 (January 1, 2020) | |

| Population density : | 4.9 inhabitants per km² | |

| Postal code : | 5743 | |

| Area code : | 06564 | |

| Community code : | 5 06 07 | |

| NUTS region | AT322 | |

| Address of the municipal administration: |

Oberkrimml 37 5743 Krimml |

|

| Website: | ||

| politics | ||

| Mayor : | Erich Czerny ( ÖVP ) | |

|

Municipal Council : ( 2019 ) (13 members) |

||

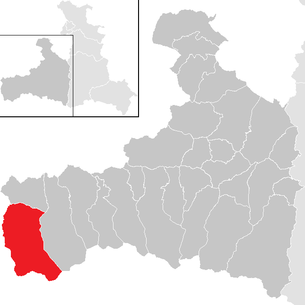

| Location of Krimml in the Zell am See district | ||

View of Krimml from the Krimml waterfall |

||

| Source: Municipal data from Statistics Austria | ||

Krimml is an Austrian municipality in the Zell am See (Pinzgau) district in the Salzburg region with 830 inhabitants (as of January 1, 2020). It is located in the Oberpinzgau region , about 26 kilometers from the main town of Mittersill and 54 kilometers from the district capital of Zell am See and is part of the Hohe Tauern national park communities .

etymology

There are different theories about the origin of the place name itself. On the one hand, reference is made to the Slavic word “Chrumbas”, meaning “hostel”, which could indicate the importance of the place as a resting place when crossing the Krimmler Tauern. At Lahnsteiner there is a derivation of the word "curvature", as the Krimmler Ache has a strong loop shortly before its confluence with the Salzach at today's municipal boundary between Krimml and Wald im Pinzgau .

geography

The center of Krimml is 1067 meters above sea level, below the Gerlos Pass in a valley basin. Krimml is the most south-westerly municipality in the state and, in addition to state borders with the Tyrolean districts Schwaz and Lienz , also has a federal border with Italy . Above the waterfalls, the Krimmler Achental extends with the two side valleys Rainbach and Windbachtal. From the Krimmler Achental, two foot crossings, the Birnlücke and the Krimmler Tauern, lead to the neighboring Ahrntal and thus to Italy. About the Rainbachtal resp. The Rainbachscharte leads to the Wildgerlostal , which also belongs to Krimml .

Krimml is best known for the Krimmler Waterfalls , where the Krimmler Ache plunges in three stages with a total drop of 380 m from the Krimmler Achental into the Krimml basin. While today the origin of the Salzach is generally located on the Salzachgeier, and Krimml cannot therefore be counted as part of the Pinzgau Salzach Valley, it is largely certain that in the past the Krimmler Ache was seen as the uppermost course of the Salzach. It was not until the Salzburg pedagogue and enlightener Franz Michael Viertaler in 1796 that the origin was determined in the northwest corner of the Oberpinzgau.

climate

|

Average monthly temperatures for Krimml

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Community structure

The municipality includes the following three localities (population in brackets as of January 1, 2020):

- Hochkrimml (30)

- Oberkrimml (542)

- Unterrimml (258)

The municipality consists of the cadastral municipality of Krimml.

While Hochkrimml encompasses the Gerlosplatte area, and most of the settlements are holiday apartments and houses, the other two districts form the original town of Krimml.

As part of the citizenship and registry office association Neukirchen am Großvenediger, the citizenship registry responsible for Krimml and the registry office are located in Neukirchen am Großvenediger . Until 2002, Krimml was part of the Mittersill judicial district and has been part of the Zell am See judicial district since 2003 . Together with eight other Oberpinzgau communities, Krimml forms the Oberpinzgau regional association. The community is, together with the other Oberpinzgau communities as far as Hollersbach , part of the Oberpinzgau West cleanliness association, which is responsible for the infrastructure regarding sewer systems and the proper disposal of waste water from the region.

Neighboring communities

| Forest in Pinzgau | ||

|

Gerlos ( District Schwaz , Tir.) Brandberg ( District Schwaz , Tir.) |

|

Neukirchen am Großvenediger |

| Prettau (BG Pustertal , BZ , Reg. Trentino-South Tyrol , IT ) | Prägraten am Großvenediger ( District Lienz , Tir. ) |

Population development

history

Prehistory and early history to antiquity

Traces of the first settlement of today's municipality of Krimml go back to the Early Bronze Age . These are documented by numerous finds from this epoch as well as from the later Bronze Age and the early Hallstatt Age , which excavations under the prehistorian Martin Hell in the middle of the 20th century brought to light .

How permanent these early settlements were is difficult to reconstruct today. At the turn of the 7th to the 6th century BC, the change to a new culture took place in the western Alpine region, which is commonly referred to as Celtic . With a bit of a time lag, this also caught on in the Eastern Alpine region.

With the Celtic settlement or "Celtization" of the resident population of today's Pinzgau, the transition from prehistory or prehistory to the historical age for this region can be dated. According to general agreement, the whole of today's Pinzgau and with it Krimml was the settlement area of the Ambisonts . Around 200 BC, the Kingdom of Noricum emerged as a loose association of Celtic tribes , which very soon came into contact with its Roman neighbors. 15 BC The Alpine Celts were finally subjugated by the Romans under the step-sons of Augustus , Tiberius and Drusus , including the Ambisonters, who are listed next to almost fifty other Celtic tribes at the great victory monument of La Turbie .

In the year 10th BC Regnum Noricum became part of the Roman Empire. Like the cisalpine, the transalpine Celts became Romans. The use of the Krimmler Tauern as a transition has been documented since that time, but has been assumed to be probable since the Bronze Age.

With the Romans, a new language, a new culture and new goods came to the region and many of these goods found their way across the Krimmler Tauern. Belonging to the Roman Empire lasted 500 years. Assimilation to Roman culture meant that the Celts in this area were referred to by the Germans as "Roman" or "Walchen". Under Claudius , Noricum finally became a Roman province, Iuvavum a municipality town, whose administrative district also included the area of today's Krimml as a peripheral area.

There are no indications of a permanent settlement in today's municipal area in Celtic and Roman times. During this time, too, its importance as a transport connection to the neighboring Ahrntal is crucial. According to Lahnsteiner, Albert Muchar writes in his first volume of The Roman Noricum about the significant remains of a Roman road up to the Krimmler Tauern and about the fact that today's Edenlehen was an old restaurant and, above all, a rest stop before the ascent to the Tauern. There is also said to have been a rock cellar for storing wines in the Schmiedpalfen. Otherwise, as for the rest of the Inner Mountains, the settlement was extremely sparse (for example, an estate in today's Bramberger district of Weyer is occupied). The increasing incursions of the Alemanni and other Germanic tribes also led to the abandonment of most of the manors and unprotected villages. In 488 the population of Ufernoricum was evacuated and transferred to Italy. Smaller parts of the population remained in the country and were referred to by the Teutons as Roman and Walchen.

middle Ages

After the Celts and Romans, it was the Bavarians who brought a new language and culture into the country. In the first phase of the Bavarian conquest of the land, however, the Inner Mountains remained unattractive for heavy settlement.

As part of the Duchy of Bavaria, the County of Oberpinzgau was given to the Counts of Lechsgemünd in 1100. During this time there was also increased clearing and reclamation in the Upper Pinzgau, which was also caused by a general increase in population. In a purchase agreement between the “Hauskloster” Kaisheim in Lechs- münd and the Archbishop of Salzburg, an estate with the name “Chrvmbel” is mentioned for the first time. In 1228 the Upper Pinzgau came to the Archbishopric of Salzburg under Archbishop Eberhard II Eberhard von Regensberg .

With the exception of the church, only a few traces have survived from the Middle Ages. However, this is one of the oldest in Pinzgau. In 1244, the Raitenhaslach monastery received a hat from the "Churches in the Khrumbe" - the first mention of the Krimml parish church through a donation from Eberhard II. The importance of the Tauern traffic in this context is evident from the fact that the goods belonging to the Raitenhaslach monastery had to pay an annual fee to Wallisch-Wein (wine from Italy).

In the middle of the 14th century, the archbishop's land register for Krimml had 12 houses. The transitions into the neighboring Ahrntal valley into today's South Tyrol were particularly important for craftsmen and merchants (wine and cattle trade) as well as for the farmers who grazed their cattle in the Krimmler Achental in summer. The Krimmler Tauernhaus was documented in writing as early as 1389 as an important station before the transition to Tyrol. This is now in operation as a hostel and snack bar.

Modern times

The Reformation and the Peasant Wars also affected the most remote corners of the Archdiocese of Salzburg. In his chronicle for Krimml, the priest Josef Lahnsteiner lists in detail those families and fiefs who sympathized with Protestantism. Those who were not prepared to renounce the teachings of the Reformation were also expelled from Krimml.

Krimml formed the westernmost cross costume in the archbishopric of Salzburg (administrative district with a church), consisting of the Ober- and Unterkrimml ranks, in the administrative area of the Mittersill nursing court.

Krimml belonged to Bramberg church until 1555 , then to Neukirchen am Großvenediger until 1675 and then to Wald im Pinzgau until 1784. In 1784 Krimml became independent as a vicariate.

In Lorenz Hübner a brief description of the inhabitants Krimmls found in 1796: "It now counts 300 people here, a funny, liberal and open-hearted folk, without deceit and false. The Ortswirthshaus also eats witness that there is a happy crowd who eats and loves to dance and jump. "

In 1803, with secularization, the spiritual rule over Salzburg ended after a millennium. This was followed by the short-lived Electorate of Salzburg 1803-1805, the years of belonging to the Austrian Empire until 1809 and that of the Kingdom of Bavaria between 1810 and 1816 as the Salzach District . When French and Bavarian troops occupied parts of Salzburg in 1809, the son of the farmer's back in Krimml, Anton Wallner , excelled in resisting the occupiers. The Anton Wallner monument is still located in the center of Krimml today. Both the historic rifle company and the local music band are named after Anton Wallner. The Anton Wallner Bräu microbrewery has also existed in the village for several years .

Between 1816 and 1849 Salzburg was part of the province of Upper Austria and Salzburg as the Salzburg district before the crown land of Salzburg was established in 1849/50. The Zillertal was separated from Salzburg in 1816. For Krimml this means that the Gerlos Pass has now also become a border pass.

As is typical for the entire region, Krimml was primarily characterized by the cattle farming, which was limited to the production of milk and dairy products. Due to the labor-intensive production in the high mountain region, it was not competitive in comparison with that of other crown lands. This only changed with the advent of early tourism, alpinism and the associated transport links in the late 19th century.

As early as 1835, the keeper of Mittersill, Ignaz von Kürsinger , had a path and a tourist and painter's house built to the upper end of the lower waterfall. In 1879, the German Alpine Club and the Austrian Alpine Club built a path with viewing platforms and bridges. Finally, in 1898, the Pinzgauer Lokalbahn runs from Zell am See to Vorderkrimml (district of Wald im Pinzgau ), which means that more and more people are visiting the waterfalls. This makes a renewed expansion of the waterfall path necessary, which is finally carried out by the Warnsdorf Alpine Club section. Until the outbreak of the First World War , tourism increased gradually, which is reflected in the construction of numerous refuges and inns. The railway restoration at Krimml station was carried out in 1898, the Falkenstein restoration in 1899, the Hotel Krimmler Hof in 1900, the Filzstein inn in Hochkrimml in 1901, and the "Hotel zu den Krimmlerfälle" in 1902.

Contemporary history

Of the 85 men who were involved in the First World War from Krimml, 20 died. In the inter-war period, the change from a purely agricultural to a tourist community continued, and the beginning winter tourism in particular became increasingly important. A restaurant built on the Gerlosplatte in 1903 is expanded into a Plattenhotel in 1932. However, the global economic crisis and the thousand-mark barrier ultimately resulted in an almost complete collapse in tourism.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Krimml was one of the strongholds of the National Socialists in the Inner Mountains, where they achieved the best result in the district with 37.92% in the 1932 state elections. After the annexation of Austria , Krimml and Wald were united to form the municipality of Krimml-Wald on January 1, 1939, and were only divided again at the end of the Second World War . In the years 1939–1942, the former mayor of Wald, the farmer Johann Oberhauser, acted as mayor of Krimml-Wald, then until 1945 the former mayor of Krimml, the businessman Johann Schleinzer.

The historian Sonja Nothdurfter-Grausgruber describes the Krimmler's relationship to the Nazi regime as ambivalent, since the bourgeois camp clung to the new rulers unconditionally, while the enthusiasm of the Christian-social peasants was less, because church struggle, restriction of their property rights by the Hereditary Farm Act and the Court controls of the National Socialists were rejected.

Tourism came to a standstill in the war years 1939–1945. The hotels and inns were used differently accordingly. There was a rest home for the German railway workers in Krimml as well as a rest home for mothers run by the National Socialist People's Welfare. The Krimmler Achental was used as a hunting area by high-ranking National Socialists. Numerous foreign workers ("Eastern workers", prisoners of war) were also employed in Krimml, here primarily in agriculture. Towards the end of the war, according to Lahnsteiner, many SS men came from Italy over the Krimmler Tauern in order to get to their homeland from here. In addition, more than 1,000 bomb refugees were quartered in the Krimml households. Of the 125 Krimml men who had been involved in the Second World War, 34 died. On May 10, 1945, a colonel in the US Army took quarters with his officers at the Waltl Inn.

The fact that Krimml was the only municipality in the state of Salzburg - located in the American zone of occupation from 1945 to 1955 - borders on Italy (western North Tyrol was French, southern East Tyrol was occupied by the British), led to the Krimml Jews fleeing from Krimml in the summer of 1947 . After the previously used Alpine crossings in the British and French occupation zones of Austria had been closed to the thousands of Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe, 5000 Jewish refugees crossed the Krimmler Tauern Pass on their way via Italy to Palestine . The hut owner Liesl Geisler-Scharfetter looked after these people in the Krimmler Tauernhaus before they finally started the arduous crossing into the South Tyrolean Ahrntal . However, the perpetrators were also on the run, and many of them also chose the route over the Krimmler Tauern to Italy and from there often on to South America. During this time, the municipality of Krimml issued many identity cards for crossing the border.

With the economic miracle , tourism resumed early after the Second World War, which over the decades has increasingly focused on winter tourism. The construction of the Gerlos Alpine Road and the Durlaßboden reservoir in the early 1960s represented major infrastructure projects . In 1963 the first tow lifts were built on the Gerlosplatte and the ski area was gradually expanded. The preliminary highlight was the merger with neighboring ski areas in Königsleiten and the Zillertal to form the Zillertalarena in 2003. In the Hochkrimml, an alpine village was built, similar to the Königsleiten settlement in the municipality of Wald im Pinzgau , whereby winter tourists could be accommodated in the immediate vicinity of the ski area. So far, not implemented, but discussed again and again is a cable car project that is supposed to connect the actual town of Krimml directly with the Zillertal Arena .

In 1967 the Krimml Waterfalls were awarded the European Diploma for Protected Areas and with the establishment of the Hohe Tauern National Park in 1981, Krimml became a national park community.

coat of arms

The coat of arms of the municipality is "divided by an oblique left wave cut from silver over blue and in it the blue initial 'K' above, exaggerated by a blue crown."

politics

The community council has a total of 13 members.

- With the municipal council and mayoral elections in Salzburg in 2004, the municipal council had the following distribution: 7 ÖVP, 5 SPÖ, and 1 ÜWK.

- With the municipal council and mayoral elections in Salzburg in 2009 , the municipal council had the following distribution: 7 ÖVP, 5 SPÖ, and 1 ÜWK.

- With the municipal council and mayoral elections in Salzburg in 2014 , the municipal council had the following distribution: 7 ÖVP and 6 SPÖ.

- With the municipal council and mayoral elections in Salzburg in 2019 , the municipal council has the following distribution: 8 ÖVP and 5 SPÖ.

- mayor

| Surname | job | time |

|---|---|---|

| Simon Geisler | Handlbauer | 1908-1912 |

| Andrä Bachmaier | Duxerbauer | 1912-1919 |

| Anton Hofer | Innkeeper | 1919-1922 |

| Nikolaus Lerch | Bamerbauer | 1922-1925 |

| Stefan Lerch | Veitenbauer | 1925-1938 |

| Hans Schleinzer | Merchant | March 1938 to December 13, 1938 (merger of the municipalities of Wald and Krimml) |

| Johann Oberhauser | Mayor of Krimml-Wald | December 14, 1938–1942 |

| Hans Schleinzer | Mayor of Krimml-Wald | 1942-1945 |

| Stefan Lerch | Veitenbauer | April 1945 - May 1945 |

| Ernst Hofer | Sandbichlbauer | May 1945 - spring 1946 |

| Stefan Lerch | Veitenbauer | 1945-1949 |

| Johann Oberholenzer | Duxerbauer | 1949-1957 |

| Jakob Lerch | Bamerbauer | 1957-1964 |

| Ferdinand Oberholenzer | Duxerbauer | 1964-2003 |

| Erich Czerny | Managing Director of the Oberpinzgau Regional Association, Director of Bramberg Tourism Schools | 2003 - |

- Mayor until 1957

- Mayor to this day

Culture and sights

- Catholic parish church Krimml hl. James the Elder: first mentioned in 1244

- Krimml waterfalls : the waterfalls have a total drop of 380 m

- Krimmler Achental

- Krimmler Tauernhaus

- Krimmler Tauern

- Pear gap

- Durlaßboden memory

- Plattenkogel

- Gerlos Pass

- WasserWunderWelt - water experience

- regional customs

Although the municipality of Krimml never belonged to Tyrol politically, the geographical proximity and the intensive exchange, both with the Zillertal , but above all with the neighboring South Tyrolean Ahrntal , have resulted in both customs and culinary specialties in Krimml are unknown in the rest of Pinzgau. On the other hand, many of the customs that are widespread in the Salzburg area can of course also be found in Krimml.

The peculiarities of the Krimml tradition include a .:

“Easter fochiz” : The word itself is derived from the Italian focaccía and describes a flatbread made from wheat flour, which is baked for Easter and is traditionally given away by the godparents to the godchildren. It is baked in such a way that a small hollow is created in the middle in which the colored eggs are laid. In its original form, however, the fochiz has almost been forgotten in Krimml. In South Tyrol, especially in Vinschgau , the name Oster-Fochaz is common. On All Saints' Day the sponsored children are presented with a deer (made from white bread or milk bread). This tradition can also be found in other regions of Salzburg and is probably of Celtic origin.

“Alperer” (“Genoiperer”): around Saint Martin's Day, boys between eight and fourteen years of age go from house to house in Krimml. One of them, disguised as a milker, is equipped with a fenugreek and a large basket into which the visitors give their presents - mostly in the form of sweets. Money is also often given away, which is divided up at the end of the day. The rest of the boys have cowbells tied around their stomachs, with which, after the milker has given the horn, they ring extensively in front of each house. This custom is also unknown in the rest of the Pinzgau, whereas in South Tyrol, both the German and the Ladin- speaking inhabitants, have similar traditions.

“Lessln” : On Thomasnacht , from December 21st to 22nd, in Krimml the lot is still occasionally drawn and the future is looked at. Nine hats are distributed on a table and a symbol is hidden under each hat. A prophecy is assigned to each symbol. The person who wants to look into their future leaves the room three times so that the others can swap the symbols under their hats. Three hats are now lifted and one of the symbols is drawn three times, according to superstition, the corresponding prophecy comes true.

For a long time there were also special features in the culinary area, which can be traced back to the exchange with the Ahrntal. While the well-known Pinzgau way of preparing Kasnocken has established itself in Krimml today, these were originally prepared in the Ahrntal style.

language

Up until the first half of the 20th century, a dialect was spoken in Krimml that was clearly distinguishable from the rest of the Pinzgau and was very similar to that of the neighboring Tyrol. In the course of the 20th century, presumably due to the consequences of the new demarcation after the First World War and the emerging tourism, this dialect, which some called "Old Krimmlerisch", disappeared and today no longer has a speaker. The word “just” in the meaning of “only” or “only”, which is typically pronounced in Pinzgau with a long vowel, was pronounced in Krimml, as is typical for many Tyrolean dialects, as “juscht”. It was also called "hosch" instead of "hôst" ("you have"), "bisch" instead of "are" (with a long vowel; "you are") or "z'morgats" instead of "a da Friah" ("morning" , "early in the morning").

Today, however, the variant of the Pinzgau dialect that is typical for Oberpinzgau is spoken in Krimml as well , with individual peculiarities. In Krimml, for example, people speak of "Grantn" instead of "Grangn" ( cranberries ), or they say "g'schnochts" instead of "d'schnochts" for "in the evening" or in the evening.

education

The community of Krimml has a community kindergarten and elementary school.

traffic

There is a road connection to the village from Zell am See via Gerlosstrasse (B165), which, if the Gerlos Pass is passable, also provides a connection to Gerlos and thus to the Zillertal.

Until 2005, the place could be reached by train from the Krimml train station , which is outside the town, about 3 km from the waterfalls, in the municipality of Wald im Pinzgau , with the Pinzgauer local railway from Zell am See . As of 2005, the route was no longer passable due to a flood between Mittersill and Krimml train station. Traffic on the rebuilt narrow-gauge railway was resumed on September 11, 2010. An extension of the run to the Krimml Waterfalls is also under discussion again.

Post buses run regularly in the direction of Zell am See. In terms of tariffs, these, like the local railway, are part of the Salzburger Verkehrsverbund .

Personalities

- Anton Wallner (1758–1810), Salzburg freedom fighter, born and raised in Krimml

- Liesl Geisler (1905–1985), hut landlady, born and raised in Krimml

- Franz Innerhofer (1944–2002), writer, born in Krimml

- Simon Geisler (1868–1931), member of the National Council, born in Gerlos , innkeeper and farmer in Krimml

- Helmut Zobl (* 1941), visual artist, grew up in Krimml

- Sybille Schmitz (1909–1955), German actress, lived with her husband, the German-Swedish screenwriter Harald G. Petersson (1904–1977), in part in Krimml

Web links

- 50607 - Krimml. Community data, Statistics Austria .

- Krimml . In: Salzburger Nachrichten : Salzburgwiki .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Website of the Krimml elementary school , accessed on November 21, 2013.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 173.

- ^ Karl Forstner: New interpretation of old river names in Salzburg. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 144th year of the association, 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ Statistics Austria: Population on January 1st, 2020 by locality (area status on January 1st, 2020) , ( CSV )

- ↑ Website of the market town of Neukirchen am Großvenediger ( Memento of the original from December 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Website of the Oberpinzgau Regional Association , accessed on November 25, 2013.

- ^ Website of the RHV Oberpinzgau West ( memento of the original from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 186.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch : A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. Salzburg. 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch: A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Alexander Demandt: The Celts. (= CH Beck knowledge). 2007, p. 91.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch: A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. 2001, p. 16f.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 182.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch: A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. 2001, p. 20f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Sonja Nothdurfter-Grausgruber: In a nutshell: Why Krimml? A short story. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Website of the municipality of Mittersill , accessed on November 21, 2013.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, pp. 187-189.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 187.

- ^ A b Lorenz Huebner: Description of the archbishopric and imperial principality of Salzburg with regard to topography and statistics. Second volume. The Salzburg mountains. Pangau, Lungau and Pinzgau. 1796, p. 589.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 192.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch: A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. 2001, p. 160ff.

- ↑ Heinz Dopsch: A Little History of Salzburg. Urban and countryside. 2001, p. 166f.

- ^ Website of the Krimml Waterfalls ( Memento of the original from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 204.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 188ff.

- ^ Laurenz Krisch: The electoral successes of the National Socialists in the late phase of the First Republic in Pongau and in Pinzgau. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 140th year of the association, 2000, p. 258.

- ↑ Peter Schernthaner: Pinzgauer NS mayor as reflected in local historical representations. In: Communications from the Society for Regional Studies in Salzburg. 147th year of the association, 2007, p. 335.

- ^ Josef Lahnsteiner: Oberpinzgau. From Krimml to Kaprun. A collection of historical, art-historical and local history notes for friends of the homeland. 1956, p. 188.

- ↑ Judith Brandtner: Don't look out of the window. 5000 Jewish refugees cross the Krimmler Tauern Pass. Destination: Palestine. on: diepresse.com , August 17, 2007.

- ^ Victims and perpetrators on the run. In: Susanne Rolinek and others: In the shadow of the Mozartkugel. Travel guide through the brown topography of Salzburg. 2009, p. 211ff.

- ^ History of the Gerlos Alpenstrasse. Retrieved December 1, 2013.

- ↑ Ferdinand Oberhollenzer . In: Salzburger Nachrichten : Salzburgwiki .

- ↑ Erich Czerny . In: Salzburger Nachrichten : Salzburgwiki .

- ↑ Anton Solingen: Solingen Chronik.gedruckt 1993, p 65, list the mayor of 1908-1957.

- ^ List of the mayors of Krimml on Salzburgwiki , accessed on December 27, 2013.

- ↑ diebackstube.de

- ↑ salzburg.com

- ↑ altabadia.it

- ↑ search.salzburg.com ( Memento of the original from April 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.