High medieval east settlement

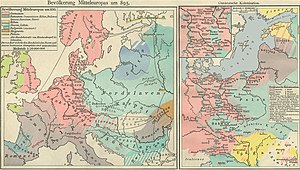

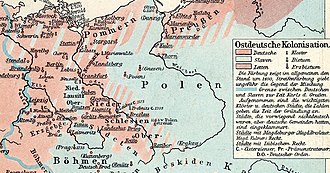

The term High Medieval Ostsiedlung (also German Ostsiedlung or simply Ostsiedlung ) describes the immigration of predominantly German-speaking settlers to the eastern fringes of the Holy Roman Empire during the High Middle Ages and the associated changes in the settlement and legal structures in the immigration areas. These are the areas east of the Saale and Elbe , in Lower Austria , Styria and Carinthia, as well as the Baltic states , Bohemia , Poland , Hungary , Romania and Moldova, which have been predominantly Slavic and partially inhabited by the Baltic since around 1000 AD . The scientific literature used for the operation since the 1980s, increasingly the concept of high medieval eastward expansion and called the settlement area as Germania Slavica ( "High medieval colonization in the Germania Slavica"). In Medieval Studies , the term German Ostkolonization , which was often used in the past, has hardly been used since the middle of the 20th century due to its linguistic proximity to the colonialism of modern times .

In the immigration area, which cannot be clearly delimited, cities and colonist villages were laid out according to German law , and existing villages and early urban settlements were expanded and restructured. In the former Marche near to the empire , the southern Baltic region and in Silesia, the West Slavic pre-population was assimilated with the exception of a few enclaves. In Poland, but also partly in Upper Lusatia , the German-speaking new settlers were absorbed by the Slavic majority population. In the regions between the Elbe and Oder, as well as in the Baltic States, the process carried out from the very beginning to around 1150 features of conquest and violent proselytizing; elsewhere, the initiative of local landlords showed a more peaceful settlement.

The settlement movement has its origins in the early Middle Ages , but it was not until the middle of the 12th century (in the High Middle Ages ) that there were larger, if not quantifiable, settlement movements from west to east. The purely political expansion before, without significant settlements east of the Elbe and Saale, can therefore only be attributed to the eastern settlement to a limited extent. By the beginning of the 14th century (in the early late Middle Ages ) the process can be considered to be over. The German settlement in the east took place mainly in the high Middle Ages. Beginning in the 1980s, it is understood as part of a pan-European intensification process from the Carolingian-Anglo-Saxon core countries to the periphery of the continent. The ethnic, cultural, linguistic, religious and economic changes caused by the German settlement in the east shaped the history of East Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains until at least the 20th century.

Framework

A historical-political history of events before the onset of the settlement movement can only be seen in connection with the structural preconditions of the German eastern settlement. Together they form the framework for the historical process described.

Historical-political history

Since the process of settlement in the east outside the Baltic region was only associated with military-political conquests in its early phase and was usually initiated by the Slavic sovereigns , but not by the Roman-German kings, a chronological, event-oriented overall presentation makes little sense and also hardly possible. However, a chronological series of developments existed up to the middle of the 12th century, which forms the background for the actual onset of the settlement movement.

10th and 11th centuries

Under the Ottonen and Saliern subjugation campaigns were carried out beyond the eastern borders of the empire. These took place in an area bounded in the west by the Elbe - Saale - Naab line and in the east by Oder , Bober , Queis and Moldau . Border marks were set up in the conquered areas. Castles were occupied or newly built; they were used for military control and the collection of tributes . However, there was no influx of new settlers. This phase can therefore be more appropriately described as eastward expansion (instead of eastward settlement). Christianization was limited to mass baptisms and the establishment of missionary dioceses such as Oldenburg , Brandenburg or Havelberg . The development of a parish church system only took place with the settlement of German colonists from the 2nd half of the 12th century.

However, control over areas that had already been conquered was repeatedly lost. The Slavs' uprising in 983 and an uprising of the Abodrites from 1066 had particularly serious consequences. In addition, the German rulers in the area between the Elbe and Oder came increasingly into competition with the princes of Poland , who also had a keen interest in the subjugation and conquest of the Wendish areas . The first Polish king, Boleslaw I. Chrobry, was particularly successful .

The Gospel Book of Otto III. shows four women who pay homage to the emperor , including for the first time Sclavinia , the Slavic part of Europe.

From the 12th century

A first approach to the settlement of the country east of the Saale can be found in the controversial call to fight against the Wends ( epistola pro auxilio adversos paganos slavos , 1108 ), which probably came from the Magdeburg area and the crusade against the pagans was first proposed profitable land gains for new settlers. However, the appeal had no noticeable effect; there were neither campaigns against the Wends nor a settlement of their areas. From 1124 the first settlements of Flemings and Dutch in northern Germany up to the Eider. This was followed by the conquest of the land of the Wagrians ( Abodrites ) by the Holsten or Holsteiner , Stormarner and Dithmarscher in 1139, the founding of Lübeck in 1143 and the call by Count Adolf II of Schauenburg to settle East Holstein in the same year. An important stage was the militarily only partially successful Wendenkreuzzug of 1147, a subsidiary of the Second Crusade . He was followed in 1157 the conquest of the Mark Brandenburg by Albert the Bear , the first Margrave of Brandenburg. In the 12th century, the Mark Meissen (later the Electorate of Saxony ) was also settled by Germans. Another settlement area arose in Transylvania . From the end of the 12th century onwards, monasteries and cities were established in Pomerania , the Mark Brandenburg, Silesia , Bohemia , Moravia (later German Bohemia and German Moravia or Sudetenland) and the eastern regions of Austria . In the beginning of the 13th century the Knights of the Teutonic Knights founded their own religious state in the Baltic States .

Social, demographic and legal framework

The political events took place against the background of a strong population increase throughout Europe in the High Middle Ages , which could not be absorbed either by the massive establishment of cities or by intensifying the existing settlement areas. From the 11th to the 13th centuries, the population in Germany increased from around four to 12 million. During this time, the arable land was initially expanded at the expense of the previously otherwise used areas and forest areas. The so-called inland colonization in the old settlement areas, e.g. B. in the Odenwald, but not enough. According to Robert Bartlett, other factors were a surplus of offspring of the nobility who were not entitled to inheritance, and after the success of the first crusade, the chances of acquiring new lands not only in the Holy Land but also in the peripheral regions of Europe were clearly in their sights. Added to this were the phenomena of the dissolution of the villication constitution , which enabled the population to be more mobile, as well as increasing tax pressure on the farmers.

Natural, technical and agricultural framework conditions

Climate change has been observed in Central Europe since around the 11th century, which resulted in higher average temperatures and is known as the Medieval Warm Period . In addition, there was technical progress, for example through the construction of mills, three-field farming and increased grain cultivation ( graining ). All of these factors favored the population increase mentioned above and made the development of new cultivation areas attractive, including the concentration of settlements through evaporation .

Aspects of the Ostsiedlung

In this section, elements of the high medieval country development are presented, which can be found in all affected areas of the Germania Slavica , the Baltic States as well as East Central and Southeast Europe. They can be regarded as characteristic of the process of German settlement in the east.

The old and new rulers in East Central Europe owned a lot of land, but large parts of it had not been made arable and therefore did not generate any income. After prisoners of war and forced laborers had proven to be ineffective, they therefore advertised with considerable privileges and promises for voluntary new settlers from the old territories of the empire. Beginning in the border marks, the princes settled people from the empire by granting them land ownership and improved legal status. This included binding taxes (instead of unreasonable obligations) which, however, initially did not have to be paid in the first “free years”, and the inheritance of the farm. After a time lag, the landowners themselves benefited from what at first glance appeared to be far-reaching benefits for these farmers, as they were able to generate income from the land that had previously been fallow.

As a rule, the sovereigns transferred the specific recruitment of settlers, the distribution of the land and the establishment of the settlements to so-called locators . These often wealthy men, who often came from the lower nobility or the urban bourgeoisie, professionally organized the settlement trains, starting with advertising, equipment and travel to the clearing and construction of the new settlements in the founding phase. The rights and obligations of the locators and the new settlers were regulated in a locator contract.

Stephan the Saint (1000-1038) sums up the interest of the sovereigns in new settlers in his prince mirror De institutione morum and warns his son Imre:

“Just as the settlers come from different countries and provinces, they also bring with them different languages and customs, various instructive things and weapons which adorn and glorify the royal court, but frighten the foreign powers. A country that has only the same language and the same customs is weak and frail. Therefore, my son, I ask you to meet them and treat them properly so that they prefer to stay with you than elsewhere. "

The place names of the new villages with an advertising character show that the advertising was not followed naturally in large numbers. B. Schönefeld / Schöneberg / Schönwalde, Rosenfelde / Rosenthal, Reichenbach / Reichenberg / Reichental etc. It is not uncommon for the new settlements to be named after the locators themselves, e.g. In Saxony, for example, there are a number of places called Dittmarsdorf, Dittmannsdorf, Dittersdorf and Dittersbach, whose name goes back to a locator Di (e) thmar in the 13th century.

The high medieval state development did not only take place with German-speaking settlers, but was also carried out by the long-established Slavic population in Slavic areas such as the Altmark and Wendland .

population

Long-established residents

The population density of the Wendenländer, but also of the areas east of the Oder, was low before the Ostsiedlung compared to the old settlement area and was decimated by attacks from Eastern Franconia and attacks by the Poles in the early and high Middle Ages. However, the settlers did not advance into deserted areas, but into areas that were inhabited by western Slavs such as Abodrites , Poles or Czechs to varying degrees . Elsewhere, for example, the Slavs of Carantania placed themselves under Frankish suzerainty in order to find protection from the Avars . Since the Slavs preferred to be close to the water for their settlements, there were Slavic settlement chambers between the Elbe and Oder , which were separated from each other by border forests. The areas of today's Austria were settled by Bavarians as early as the 6th century . A not inconsiderable number of the Slavs prisoners of war were enslaved and sold by mostly Jewish traders to the Muslim cultural area. The Belgian historian Charles Verlinden suggests that this population shift, which lasted into the 14th century, is a significant demographic factor.

The relationship between new settlers and the autochthonous population was shaped equally by competition and cooperation. The chronicler Otto von Freising, for example, wrote praising the wealth and fertility of Hungary, but devalued the inhabitants massively by asking himself "how such a pleasant country could fall into the hands of such - people would be said too much - into the hands of human monsters" ( Otto von Freising, Gesta Friderici, 1.32).

As a rule, the rights and habits of the local population were not curtailed, as there was enough fallow land for new settlements. New techniques and tools as well as the possibility of gradually participating in the new economic methods also opened up new opportunities and incentives for old settlers who were willing to learn and assimilate.

However, it also happened that the locals were expelled to make room for new settlers. For the village of Böbelin in Mecklenburg z. B. documented that expelled Wends repeatedly attacked the newly settled village. However, there are no known attempts at extermination. Discrimination against the old settlers was not a general concept; wherever it occurred, it was certainly not based on ethnicity. Rather, for the sovereigns, the significantly higher medium-term income from the new settlement made the displacement of the long-established population by settlers attractive. Therefore, Wends who took part in the development of the country were quickly assimilated.

Culture and language of Altsiedler disappeared during the Ostbesiedelung up isolated rural areas, such as the enclaves of Drawehnopolaben in Wendland , the Sorbs in the Lausitz and the Slovincians Eastern Pomerania . The Kashubians of Pomerellen also survived the eastern settlement, but not as a linguistic island, but as a linguistic corridor with a connection to Polish , supported by the centuries-long membership of the Prussian royal portion of the Polish crown and aristocratic republic . Kashubians and Sorbs have been able to preserve their language and culture to this day.

New settlers and long-established residents between the Elbe and Oder gradually formed the so-called “ new tribes ” of Brandenburg , Mecklenburg, Upper Saxony , Pomerania , Silesia , East Prussia and others. In addition, reference should be made to the successful self-assertion of the originally Slavic ruling families of Mecklenburg or Greifen , who continued to rule as dynasties into modern times and in some cases into the 20th century.

New settlers

Most of the new settlers came from the west of the empire (Flanders, Holland, Rhineland, Westphalia, also Swabia and Franconia). There were various motives for leaving the old homeland: On the one hand, due to inheritance law, the agricultural land at home was becoming increasingly fragmented. The entire property had to be divided among all male descendants ( real division ); this reduced the income per family. The taxes to the landlords remained the same, however, and were therefore increasingly difficult to afford, which is why many farmers barely reached the subsistence level. The opportunity to cultivate much larger arable land in the east, which, according to the promises of the sovereigns, was fertile and rich in animals, was correspondingly attractive.

The settlement to the east also meant a gain in personal freedom. So the new settlers could become hereditary tenants . The relatively low rent and the free cultivation of the land were not known in the West. As long as the owner was not damaged, the tenant could even sell the land and, in the event of inheritance, freely choose his successor. The possessions no longer had to be divided among all male descendants, but could be inherited as a whole ( inheritance law ).

In addition to the larger cultivation areas and the more generous inheritance law, many other perks also encouraged emigration to the new settlement areas in the east. In the first years of their settlement, for example, the settlers were exempt from tithe and other taxes. These benefits (free years) were valid for three to seven years or until the land to be reclaimed began to generate income. The higher yield compared to home made the taxes then incurred less onerous. Another relief were cut correspond raw measured Frondienste such. B. Help with building churches and castles. The farmers could concentrate fully on agriculture. The new settlers were also not obliged to make military trips.

Due to these privileges and the professional organization of the eastern settlement by the sovereigns, the large settlement trains set in, which have successfully opened up today's Central and Eastern Europe and have shaped structurally and culturally to this day. Similar projects were later implemented through the settlement of German farmers in Russia.

Language exchange

Language contacts on the Ostsiedlung train occurred between 1050 and 1600. In linguistics , the term language contact is understood to mean the adoption of loan words , foreign words and loan translations . In this case it is a question of a form of language exchange between the German and the Slavic languages, which remains incomprehensible without the Ostsiedlung. A distinction is made between direct and indirect language exchange. Direct language exchange occurs through direct contact between people from different language groups. This can include so-called close contact, i.e. the exchange of language elements due to the bilingualism of people or the spatial proximity of the speakers of the respective language. Remote contact, on the other hand, is the adoption of words in direct contact, which, however, occurs in the distance, i.e. not in the immediate home, B. took place during trade trips or political delegations. Indirect language exchange could take place through related dialects or through another language that acted as a "mediator" between the two languages.

Examples

The oldest evidence for the adoption of naming units is older than German and z. B. Czech or Polish. They come from the primitive Germanic and primeval Slavonic. The original Slavic name kъnędzъ can be found in almost all Slavic languages and is the borrowed Germanic word kuninga , nhd. King . German was mainly used to convey words in Slavic languages that related to handicrafts, politics, agriculture and nutrition (e.g. in the table below). This includes B. cihla , althd. ziegala , mhd. brick , which resulted from the sound shift of the Latin tegula . An example of borrowing from Slavic into Germanic usage is the word limit . So it was called in mhd. Grenize, which is a borrowing of the old Czech granicĕ or the Polish granica . City names are also affected by language exchange, sound shifting and the second palatalization . Regensburg is called Řezno in Czech and Rezъno in Ur-Slavonic . Due to the intensive language contact, idioms were also transmitted. Two examples from Czech and Polish are na vlastní pěst / na własną rękę (“on your own”) or ozbrojený po zuby / uzbrojony po zęby (“armed to the teeth”), comparable in Hungarian “saját szakállára” (on own beard) and "állig felfegyverzett" (armed to the chin), with different wording, but with the same meaning.

| Area of borrowing | German | Polish | Czech | Slovak | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| administration | mayor | burmistrz | purkmistr | richtár / burgmajster | polgármester |

| administration | Margrave | margrabia | markrabě | markgróf | gróf |

| administration | parish | fara | fara | fara | pap (pfaffe) |

| administration | town hall | ratusz | radnice | radnica | - |

| Legal system | judgment | - | Ortel | ortieľ | - |

| Craft | Bracket | klamra | rummage | - | - |

| Craft | plumber | - | klempíř | klampiar | kolompár |

| Craft | Bricklayer | murarz | - | murár | - |

| Craft | top, roof | top, roof | - | roof (dialect.) | - |

| Craft | mortar | zaprawa (malta) | Malta | Malta | painted |

| Craft | brick | cegła | cihla | tehla | tégla |

| Craft | brush | pędzel | - | - | pemzli |

| Craft | Piece | stiuk | štuk (dialect.) | štuk (dialect.) | stukkó |

| Craft | Workshop | warsztat | - | - | - |

| food | pretzel | precel | preclík | praclík | perec |

| food | sugar | cukier | cukr | cukor | cukor |

| food | Soup | zupa | - | - | szósz (sauce) |

| food | oil | olej | olej | olej | olaj |

| Agriculture | plow | pług | pluh | pluh | eke (harrow) |

| Agriculture | whip | pejcz, bicz | BIC | BIC | - |

| Agriculture | Mill | młyn | mlýn | mlyn | malom (grind) |

| Agriculture | Granary | spichrz (spichlerz) | - | - | spejz |

| trade | Lead | for a | for a | for a | furious |

| trade | Libra | waga | váha | váha | - |

| trade | Fair | jarmark | jarmark | jarmok | - |

| Animals | Peitzker | piskorz | piskoř | - | - |

| Animals | cod | dorsz | - | - | - |

| Animals | Pointed | szpic | špicl | špic | - |

| other | glasses | bryle (dialect.) | brýle | bríle (dialect.) | - |

| other | flute | flet | flétna | flauta | flóta |

| other | Heap | hałda | halda | halda | - |

| other | stud | - | knoflík | knofľa (dialect.) | - |

| other | have to | musieć | muset | musicť | muszáj (n) (must be) |

East migration of the dialect borders

As a result of the Ostsiedlung, the existing German dialect borders also expanded eastwards, although the "new" dialects differed slightly from the western dialect forms due to the composition of the settler communities into which the Wends were also integrated.

Place names

Since the Slavic field names have been adopted in many places, these represent (in an adapted and further developed form) a very high proportion of East German field names and place names. They are recognizable z. B. at endings on -ow (or Germanized -au , as in Spandau), -vitz or -witz and sometimes -in . Some villages, mostly those that were founded on cleared land or otherwise from wild roots , that is, completely new, were given German names that ended, for example, with -dorf or -hagen ; The name of the locator or the place of origin of the settlers (example: Lichtervelde in Flanders) could also become part of the place name. Sometimes Wendish field names were also adopted. If a German settlement was founded alongside a Wendish settlement, the name of the Wendendorf could also be adopted for the German village, the distinction was then made through additions ( e.g. Klein- or Wendisch- / Windisch- for Wendendorf, Groß- or Deutsch- for German ).

Technology transfer

In the course of the country's expansion, the new settlers brought with them not only their customs and language, but also new technical skills and equipment, which were able to establish and establish themselves within a few decades, especially in agriculture and crafts.

Dyke construction and drainage

Settlers from the Flemish and Dutch areas along the North Sea coast made a significant contribution to the development and development of the lands east of the Elbe. At the beginning of the 12th century they were among the first to immigrate to Mecklenburg and in the years that followed they moved further east to Pomerania and Silesia and in the south to Hungary. The motives for the large number of Dutch emigrants were varied. In addition to the lack of settlement areas in their home areas, which were already largely developed, several flood disasters and famines were decisive for the emigration from their homeland.

In addition, due to their experience and special skills in the construction of dykes and in the drainage and reclamation of marshland, they were in demand as experts for the settlement of the still undeveloped areas east of the Elbe. The land was drained by creating a network-like structure of smaller drainage ditches that drained the water in main ditches. Traffic routes connecting the settlers' individual farms ran along these main trenches.

Dutch settlers were recruited from the local rulers in large numbers, especially from the second half of the 12th century. In 1159/60 , Albrecht the Bear granted Dutch settlers the right to take possession of former Slavic settlements. The preacher Helmold von Bosau reported on this in his Slav chronicle when he wrote: “Finally, when the Slavs were gradually waning, he (Albrecht) sent to Utrecht and the Rhine region, and also to those who live by the ocean and under the power of the sea suffered, the Dutch, Zealanders and Flemings, attracted a lot of people from there and let them live in the castles and villages of the Slavs. ”In particular, Flemish law and the Flemish hooves were often adopted by other settlers. The targeted recruitment of Flemings by the Archbishop of Magdeburg is reflected in the name of the Fläming ridge .

Agricultural implements

Even before the western immigrants were resettled, the Slavs used an agricultural tool to cultivate their fields. The oldest meaningful reference to this can be found in the Slavic Chronicle , in which the use of a Slavic plow is mentioned as a measure of area: "A Slavic plow (land is that which) works a pair of oxen or a horse in one day."

In the documents of the 12th and 13th centuries, the terms hook or hook plow were often used for this device. The way the hook worked was that it tore up the soil at the surface and spread the soil on both sides without turning it. It was therefore particularly suitable for light and sandy ground. From the middle of the 13th century, the three-field economy introduced by the western settlers finally established itself in the areas east of the Elbe, especially in the previously untapped clayey soils. The new type of cultivation required the use of the heavy reversible plow.

Unlike the hook, the reversible plow consisted of several individual parts. Its most important parts were the six , the moldboard and the ploughshare . In contrast to the hook, which required another transverse operation in the case of heavy soils in order to loosen the soil, the reversible plow could dig up the earth deeply and turn it to one side in just one operation.

This fact was taken into account when determining the taxes. The burden of interest and tithes for the farmers, who still used the hook to cultivate their fields, was only half of the fees of the users of the more economical reversible plow due to the lower yields.

The different modes of operation of the two devices also had an impact on the shape and size of the cultivation areas. The fields worked with the hook had roughly the same field length and width and had a square base that was plowed like a chessboard. Long fields with a rectangular base ( Zelgen ) were much more suitable for the reversible plow , as the heavy implements had to be turned less often. In addition to the introduction of the new production techniques, there was also a change in the type of planting due to the cultivation of new types of grain , of which oats , and in Brandenburg also rye , became the most important type of grain.

Pottery

The potters were among the first group of craftsmen who also settled in the rural areas. Stand-up vessels were typical of Slavic ceramics. With the influx of new settlers from the west, new vessel shapes such as the spherical pot emerged . In addition to their appearance, they also differed in the harder firing process from the previous Slavic ceramics, which were widespread in Eastern Central Europe. This type of ceramics, known as hard gray ware , appeared more and more in the areas east of the Elbe from the end of the 12th century, initially in a softer variant. It was manufactured across the board in Pomerania by the 13th century at the latest, when new or further developed manufacturing methods, such as the horizontal pottery kiln, enabled the mass production of ceramic household goods.

At the same time, with the progress of the country's expansion, the need for household goods such as pots, jugs, jugs and bowls, which were previously often made of wood ( stave shells ), increased steadily and promoted the development of new sales markets.

Further refinements in ceramics production in the 13th century were the emergence of glazed ceramics and the increasing importation of stoneware , so that Slavic ceramics were completely displaced in the course of a few generations. For Slavic ceramics, see also: Ceramics of the Leipzig Group

The transfer of technology and knowledge affected the way of life of old and new settlers in a variety of ways and, in addition to innovations in agriculture and handicrafts, also included other areas, such as weapon technology, documents and coins.

architecture

Type of the half-timbered house

The Slavic population ( Sorbs ) who lived east of the Elbe built primarily in log houses (scrap wood houses), which had proven themselves in regional climates. The wood, much needed for this, was plentiful in the continental regions. The German settlers, mainly from Franconia and Thuringia, who advanced into the area in the 13th century, brought with them the half-timbering , which was already known to the Germans, as a wood-saving, stable construction method. This made it possible to erect multi-storey buildings. A combination of the two construction methods was difficult because the horizontally stacked wood of the log room expands differently in height than the vertical posts of the framework. The result was the new type of half-timbered house with a half-timbered frame around the log room on the ground floor, which alone supports the upper floor, which is also made of half-timbered houses.

Village forms and corridor systems

The Ostsiedlung also produced typical shapes in the morphology of settlements and arable land.

Village forms

Different village forms are typical of the German eastern settlement, such as the street village , the Angerdorf , the Rundling or the Waldhufendorf . These types of settlement were to a lesser extent transferred from the old settlement area, but to a greater extent also developed for the new settlements in order to adapt ideally to the geographical conditions. The founding of the villages in the German East Settlement was a deliberate intervention by the rulers. The new settlements were planned and controlled, so it was not a matter of uncoordinated individual activities. By the 12th or 13th century, individual farms and hamlets in the Altreich had developed into medium-sized villages without any villication ("vaporizing"). Three types of land division were predominant in the Ostsiedlung: broad strips, regular Gewannflure with three-field farming and forest hoof settlements . A hoof village (or row village) was created when the hooves were attached to the regularly lined up farms in closed longitudinal strips. Courtyards at a distance of 100 m each led to elongated villages, the Waldhufensiedlungen. There were also special forms such as the Rundling and the alley village . The origin of the Rundling cannot be clearly explained, but it is relatively certain that there is a close connection between the influx of German landlords and the restructuring process of Slavic settlements in the new agricultural and legal system.

In the middle of Brandenburg there were also regular anger and street villages with Hufengewannfluren. The creation of large plan forms is probably a sign of the dissolution of small Slavic settlements and integration into the new villages, often as kossas . However, this did not mean the complete abolition of the previously existing Slavic small settlements, which were restructured more regularly. The forms of settlement can be spatially differentiated more clearly the further east one looks. Breaks in the forms of settlement in the areas occur, for example, due to forest mountains.

Research methods

In connection with the investigation of the village forms in the eastern settlement, two methods of map evaluation should be mentioned in addition to steppe heath theory and primeval landscape research, old landscape and place name research and geographical desertification research . On the one hand there is the static-formal cadastral map evaluation . This method was used for the first time by A. Meitzen , who used land maps and cadastral plans as an aid for legal disputes as a commissioner in the Prussian judicial service. In the 19th century it was generally assumed that rural forms of settlement represented characteristics of certain cultural groups. On the other hand, the write-back cadastral map evaluation is important. This is based on Wilhelm Müller-Wille's topographical-genetic method of land map interpretation , which refers to spatially differentiated fields that are not only based on unequal parcel associations or the land distribution of social groups. The developments of individual parcels and natural circumstances are also taken into account here. The extent to which an investigation is possible at all is based mainly on the source situation, the regularity of a hallway, the size of the mixture, the inheritance law and the social structures. Only on this basis can the static-formal and topographical-genetic methods as well as the write-back be used.

criticism

The origins of the village forms of the German eastern settlement and the Slavic influence on it are little questioned and not yet adequately documented. The assumption that the street, Anger and Waldhufendörfer were simply taken over from the old settlement areas in their entire structure is now being strongly questioned. For this research approach, it is more likely that these forms only fully developed in the Neusiedel area. It should also be assumed that the integration process of the new settlers has continued over a period of several generations. Another deficit in previous research lies in the limitation of the investigation of this topic to the new settlement areas. According to Eike Gringmuth-Dallmer , an attempt should be made “ to compare the conditions in the areas of origin and the areas of development directly and in a complex manner”.

Hallway types

The corridors are to a large extent characteristic of the medieval eastern settlement. A corridor is understood to be the agricultural area that is available to a settlement minus the forest area. The smallest elements of a hallway are called parcels . These parcels have different shapes and sizes. Several blocks or strips can combine to form a parcel structure. Larger corridor districts are also known as Zelgen .

In the research, two basic types of land are distinguished, regardless of the German Ostsiedlung:

Block corridor

The block corridor consists of several rectangular parcels or blocks , with each individual block belonging to a different owner. A distinction is made between the consolidated ownership of a company ( Einödlage ) and the distribution of parcels over different corridors ( mixed situation ) as well as large and small blocks. A large block should cover at least 10 to 15 hectares . Everything below is understood as a small block. A distinction is made between regular and irregular parcels in both small and large blocks . The ratio of width to length of the plots is less than 1: 2.5 in block corridors. Block corridors, suitable for the use of light hook plows, are therefore understood as areas of the Slavic old settlers.

Basement hall

The corridor is also called a strip corridor. The term won could come from turning the plow, which should be avoided because of the high physical exertion and so led to the long strip of land. This can be seen in the fields that are only approx. 20 m wide, but up to 150 m long, because the plows were not set down over long distances. If several tubs are put together, one speaks of a tub hallway. The individual tubs were divided into smaller and smaller strips due to inheritance law.

Gully corridors emerge from a strip-like division of the above-mentioned blocks. The ratio of width to length of the parcels is therefore over 1: 2.5 in the striped fields. This type of corridor has been observed since the 8th to 10th centuries, but has continued to expand into modern times. In the context of the Ostsiedlung it served as an indicator for the reclamation by new settlers because the use of the new plows with more efficient draft animals enabled better yields. Due to their higher weight, they worked the ground not only superficially, but could only be turned with difficulty and thus favored the creation of long strips of land.

Change of cities

The Ostsiedlung not only changed the rural and agricultural environment, it also had a massive impact on the urban settlements in Eastern Central Europe.

City foundations

The development of the state in Germania Slavica was not only associated with the establishment of villages, but also with the establishment of towns. On the one hand, there were already many Slavic castle towns ( castra ) such as B. Lübeck , Brandenburg an der Havel or Krakow , which were already the centers of power. However, they experienced substantial growth from the end of the 12th century through targeted new settlements and expansions ( locatio civitatis ). The settlement of a bishopric, such as in Havelberg , could lead to the development of a town. But cities were also founded out of nowhere ( from wild roots ), such as B. Neubrandenburg . As with the villages, locators were also used here . Characteristic of the founding cities are geometrical or at least planning-revealing floor plans, such as two main streets as intersecting axes and a central, often rectangular market place. Combined urban and village settlements can be observed, especially in the case of new establishments: Villages are created to generate excess grain, which at the same time need an urban collection point (often in the form of oppida for connection to the trade). In the emergence of twin cities, which accordingly have names such as new town or old town , different settlement phases and settlement leaders are reflected.

Role of city rights

The granting of city rights played an important role in the course of the German settlement in the east. Due to the city rights , the residents of a specified area were privileged, which attracted new settlers. Existing suburban settlements with a market function were given formal town charter and then rebuilt or expanded. Small settlements inhabited by old settlers also enjoyed these rights. Independently of existing suburban settlements, locators were commissioned to completely re-establish cities. The focus was always on the goal of attracting as many people as possible under more favorable legal conditions in order to create new, flourishing centers.

Expansion of the German city rights

There were a number of different German city rights or families of city rights. The greatest role in the eastern settlement played the Magdeburg and Lübische law , which served time and again, often in more or less modified form, as a model for new cities. Other city rights that were of regional importance include a. the Nuremberg law , the Mecklenburg law and the law of Jihlava . Lübeck law had its beginnings in the city of Lübeck as early as 1188. In the 13th and 14th centuries, it served as a model for around 100 cities in the entire maritime and trading area of the Baltic Sea, including Rostock , Stralsund and Greifswald . In addition, it spread to the Baltic States (e.g. Reval and Narwa ) and was introduced in a few cities in the order country (e.g. Elbing ). According to Luebian law, around 350,000 people lived at the beginning of the 15th century. Magdeburg law, which goes back in part to privileges granted by Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg from 1188, first spread to Brandenburg , Saxony (e.g. Dresden and Leipzig ) and Lusatia . Later the rights based on the Magdeburg model (e.g. the Kulmer law and Neumarkt law ) were also introduced in other areas of Eastern Central Europe such as Silesia , Poland , the Order of the Land , Bohemia and Moravia , up to today's Ukraine .

Changes in the municipal rights families in the new settlement areas

In the course of time, widespread municipal rights families developed. If z. If, for example, Magdeburg law was transferred to a city, it was not unusual for this “daughter city” to function as the “mother city” in the further course (e.g. Berlin for Frankfurt / Oder). Some of the rights were changed to a greater or lesser extent. These changes could affect a reduction or increase in fines or even limit the independence of cities. So it happened B. in the Order Land, where the Teutonic Order preferred a modified form of Magdeburg law, the Kulmer Handfeste , for its cities, because the Luebian law went too far with regard to the independence of the cities. Magdeburg not only served as a model for many cities, but the city also acted as a legal supervisor in the event of legal problems, that is, the daughter cities turned to the Magdeburg Council with their problems. Since only one council was overwhelmed and ineffective in the widespread city legal family, so-called Oberhöfe were founded in the various areas to which the cities could turn. In the Lübeck family with city rights, the connections were even closer; there, until the middle of the 17th century, Lübeck served as an appeal authority for the daughter cities. Landlords and rulers often disliked the fact that cities in their sphere of influence turned to distant cities and justice was pronounced from there. They were afraid that the cities' aspirations for autonomy would run counter to their claim to rule and therefore took action against it, but only had greater success with it in the late Middle Ages .

Legal differences between old and new settlers

In some cities in the east that were founded under German law, old and new settlers had the same rights and obligations or the old settlers were granted them in the course of the 13th century. In some Polish areas, however, the indigenous rural population was forbidden from moving into the cities, as the sovereigns feared that their estates would be depopulated. It was also Slavs completely denied civil rights in some cities. The biggest difference between old and new settlers can be determined from the case law in the cities. German new settlers generally had an advantage over native old settlers. This was especially noticeable in the setting of fines. B. pay only a third of the amount for wounding an Estonian that was due if a German was wounded. There was also ethnic unequal treatment in the languages admissible in court. B. Defendants prove that they did not speak German. In Breslau in 1329 even Polish was completely banned in court. The only new settlers who were also systematically disadvantaged were the Jews, as was also common in the old settlement area. Robert Bartlett summarized the situation in many cities of the time as follows: “Social and ethnic discrimination entered into a complex symbiosis in the peripheral areas of Europe, but one thing is very clear in the reflection of ethnic legislation: how the respective balance of power between the individual ethnic groups looks like were."

Change in the religious field

The pagan religions of the Wends were faced with attempts at Christianization even before the start of settlement in the east, since the government of Otto I and the establishment of dioceses east of the Elbe . The Slav uprising of 983 threw these efforts back for almost 200 years. In contrast to the Czechs and Poles who were Christianized before the turn of the millennium , the conversion of the Elbe Slavs to Christianity was initially accompanied by violence . The arrival of new settlers from around 1150 led to a Christian reshaping of the areas between the Elbe and Oder. On the one hand, the new settlers built parish churches in their villages out of wood and later out of field stones . On the other hand, places of worship, such as the Marienkirche in Brandenburg , and monasteries, such as the Zisterze Lehnin , were built on pagan shrines . In addition, the Cistercians in particular have repeatedly been assigned a special role by church circles ("Rodeorden"), which combined the spread of faith and the development of the country. The irreplaceable merits of the Cistercians , however, lay in other areas.

European context and regional developments

The expansion and intensification of the German settlement in the east is by no means unique in Europe's medieval history. Similar phenomena can be found in all the peripheral areas of the former Carolingian empire, for example southern France and the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms or Ireland. But the emigration of the Walsers from the canton of Valais ( Switzerland ) to previously sparsely populated to uninhabited valleys in Northern Italy, Graubünden and Vorarlberg also had the same conditions in some cases. The development of individual regions in the geographically poorly delimited area that was shaped by the eastern settlement cannot be outlined here. See: Nordmark / Mark Brandenburg ; Pomerania ; Silesia ; Teutonic Order State ; Saxony ; Lesser Poland ; Bohemia and Moravia ; Austria ; Slovenia ; Slovakia ; Transylvania ; Moldova . A large part of the German settlers in the Danube region immigrated to Hungary, but only after the end of Ottoman rule .

Endpoints

There is no clear cause for the end of the Ostsiedlung, nor is there a clearly defined end point. However, a slowdown in the settlement movement can be observed around 1300; in the 14th century there were only isolated settlements with the participation of German-speaking colonists. An explanation for the end of the eastern settlement must include various factors without being able to clearly weight or differentiate between them: the deterioration of the climate from around 1300 as the beginning of the "Little Ice Age" , but also the agricultural crisis that began by the middle of the 14th century at the latest of the late Middle Ages . Together with the demographic slump caused by the Great Plague , profound devastation processes can be demonstrated. If a clear connection could be established here, the end of the eastern settlement would be understood as part of the crisis of the 14th century .

Research history

In the 18th century, the history of the German settlement in the east received more attention for the first time. With the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, an increasingly ideological research on the East emerged , which reached its peak in the interwar period (see also folk and cultural soil research ). The German eastern settlement of the Middle Ages, then almost exclusively referred to as German eastern colonization, became a kind of substitute for a missed overseas expansion for the Germans who "came too late" . After the politico-military catastrophe of the First World War , which on the one hand put an end to the colonial dreams of the Wilhelmine era and on the other hand discredited the ruling class, Germanness and the German people themselves became the most important source of identification . The German Ostsiedlung became a role model and legitimation for ethnic and national circles for a new " urge to the east ". The ideas of the “German urge to move east” and the racial superiority of the German people had a decisive influence on Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist blood-and-soil ideology . The Second World War was intended to revive and complete the German colonization in the east, which was now interpreted in a folkish way, although there were not nearly enough people available to settle.

East research in the Federal Republic of Germany was characterized by a high degree of personal and methodological continuity. It was placed in the service of the East-West conflict and the problem of displaced persons . The decidedly national, if not nationalist perspective on the eastern settlement was ended by Walter Schlesinger , who in 1975 summarized the relevant lectures of the Reichenau meetings of the Constance working group for medieval history as editor: The German eastern settlement of the Middle Ages as a problem of European history . It was not until the end of the Cold War that the way was cleared for a more impartial approach to research on the East and the German settlement in the East, above all through the more unbiased professional exchange between German, Polish and Czech researchers.

More recent research approaches see the German Ostsiedlung in a pan-European context: In addition to Charles Higounet and Peter Erlen, Robert Bartlett also stands for this with his work The Making of Europe. Conquest, Colonization and Cultural Change, 950-1350 (London 1993). For the German paperback edition (1998) the dramatic title The Birth of Europe from the Spirit of Violence. Conquest, colonization and cultural change from 950 to 1350 . Bartlett, professor for the history of the Middle Ages at the Scottish University of St. Andrews, advocates (simplified) the following thesis: The medieval climatic optimum leads to increased crop yields and thus in turn to an increase in population . This “overpressure” discharges as an expansion to the periphery of Europe, where the younger generation of sons who are not entitled to inheritance hopes to find better opportunities. In a clockwise direction, these are: Ireland, Iceland / Greenland, the Baltic States, the countries east of the Elbe and Danube (eastern settlements), but also Spain during the Reconquista and the Palestine of the Crusades .

However, at the German Historians' Day in Göttingen in 1932, Polish and Czech researchers interpreted the history of Eastern Europe as the history of its cultural Europeanization : The adaptation of ancient world culture in the form of its Christian successor cultures and their spread across Europe were interpreted as the characteristic of the development of the European field of history . The emphasis was on westernization , assimilation and acculturation . The starting point for this perspective was the fundamental cultural-regional contrast between “Old Europe” (the area of the former Roman Empire and the peripheral areas that it culturally strongly influenced) and “New Europe” (the area beyond the Rhine and Danube, which never belonged to the Roman Empire ).

For Klaus Zernack it is indubitable that the cultural expansion process of the medieval country development with the high medieval colonization of East Central Europe reached its peak in the 12th and 13th centuries in terms of scope and intensity. Such a cultural expansion, however, required the entire post-ancient Europe in order to gain the basis for the real European history of the second millennium AD. The meeting of the economic amelioration and expansion possibilities - radiating from the north-west European centers to the east - with the impulses of the northern Italian communal constitutional development has brought about the efficiency of the great west-east movement, which extends over the eastern brand areas of the empire far into the east and north-east and neighboring countries to the south-east.

Since Walter Schlesinger's paradigm shift in the view of Ostsiedlung (Ed .: Die deutsche Ostsiedlung des Mittelalters als Problem der Europäische Geschichte , 1975), changes in research approaches have led to significant changes in the image of settlement processes in Germania in the 12th to 14th centuries Slavica surrendered. These include in particular:

- In the countries primarily involved (Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia), the respective research has largely freed itself from a nationalist approach and thus paved the way for a joint working on the topic.

- It has been recognized that settlement processes can at best be justified marginally as ethnic , but that their causes are to be sought in economic, social and political changes. The fact that the Slavic population was extensively involved in the development of the country meant that the term German eastern settlement was largely replaced by the neutral formulation of the high medieval eastern settlement .

- Comparable transformation processes can be demonstrated in large parts of Europe at about the same time and thus relativize the importance of the Ostsiedlung.

- The eastern settlement has taken up the traditions of the long -established Slavic population to a far greater extent than previously assumed .

- The radical innovations to be connected with the Ostsiedlung were only partially brought with them from the areas of origin of the settlers. In many cases, they only developed and fully developed in the expansion areas.

- The inaccurate picture of the new conditions and knowledge brought with them from the West is mainly due to the fact that in many cases no attempt was made to prove the corresponding conditions in the settlers' regions of origin.

As an example of the paradigm shift see Art. History of the Mark Brandenburg .

Source collections in translation

- Herbert Helbig and Lorenz Weinrich (eds.): Documents and narrative sources on the German East Settlement in the Middle Ages I. Central and Northern Germany. Baltic coast. 3. verb. Aufl., Darmstadt 1984 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Volume 26a).

- Herbert Helbig and Lorenz Weinrich (Hrsg.): Documents and narrative sources on the German East Settlement in the Middle Ages II. Silesia, Poland, Bohemia-Moravia, Austria, Hungary-Transylvania. Darmstadt 1970 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Volume 26b).

- Helmold von Bosau : Slavic Chronicle = Helmoldi Presbyteri Bozoviensis Chronica Slavorum . Retransmitted and explained by Heinz Stoob . Scientific Book Society, 2., verb. Aufl., Darmstadt 1973 (= selected sources on the German history of the Middle Ages. Vol. 19).

- Karl Quirin: The German East Settlement in the Middle Ages, Göttingen 1986 (= source collections for cultural history, vol. 2).

literature

- Robert Bartlett : The Birth of Europe from the Spirit of Violence. Conquest, colonization and cultural change from 950 to 1350. Knaur-TB 77321, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-426-60639-9 .

- Wojciech Blajer: Comments on the state of research on the enclaves of medieval German settlement between Wisłoka and San . In: Późne średniowiecze w Karpatach polskich . Editor Jan Gancarski. Krosno 2007, ISBN 978-83-60545-57-7 .

- Sebastian Brather : High medieval settlement development and ethnic identities - Slavs and Germans east of the Elbe in an archaeological and settlement geographic perspective , in: The rural eastern settlement of the Middle Ages in northeast Germany. Studies on the development of the country in the 12th to 14th centuries in rural areas , Felix Biermann, Günter Mangelsdorf (eds.), Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 29–37. ISBN 978-3-631-54117-3

- Enno Bünz : The role of the Dutch in the Ostsiedlung. in: Eastern settlement and regional development in Saxony. The Kührener deed of 1154 and its historical environment , Enno Bünz (Ed.), Leipzig 2008, pp. 95–142.

- Michael Burleigh . Germany Turns Eastwards. A Study of Ostforschung in the Third Reich. Cambridge 1988.

- Werner Conze (founder), Hartmut Boockmann , Norbert Conrads , Horst Glassl , Gert von Pistohlkors , Friedrich Prinz , Roderich Schmidt , Günter Schödl , Gerd Stricker , Arnold Suppan (ed.): German History in Eastern Europe , 10 vol., With a Preface by Wolf Jobst Siedler . Siedler Verlag 1999. DNB certificate

- Peter Erlen: European regional development and medieval German eastern settlement. A structural comparison between southwest France, the Netherlands and the Order of Prussia. Marburg 1992.

- Eike Gringmuth-Dallmer : Reversible plow and planned town? Research problems of the high medieval eastern settlement. In: Siedlungsforschung 20/2002 pp. 239–255.

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Henning : German agricultural history of the Middle Ages, 9th to 15th centuries , Stuttgart 1994.

- Charles Higounet: The German East Settlement in the Middle Ages. Siedler, Berlin 1986/2001. - ISBN 3-88680-141-1

- Walter Kuhn : Comparative Studies on the Medieval Eastern Settlement , Cologne / Vienna 1973.

- Heiner Lück, Matthias Puhle, Andreas Ranft (eds.): Foundations for a new Europe. Magdeburg and Lübeck law in the late Middle Ages and early modern times , Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-412-12806-7 (= sources and research on the history of Saxony Anhalt , volume 6).

- Lutz Partenheimer : The emergence of the Mark Brandenburg. With a Latin-German source attachment. 1st and 2nd edition, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2007.

- Manfred Raether: Poland's German Past , 2004, ISBN 3-00-012451-9 . New edition as an e-book (Kindle version), 2012.

- Andreas Rüther : Stadtrecht, Rechtszug, Rechtsbuch: Jurisdiction in Eastern Central Europe since the 12th Century , in: Klaus Herbers / Nikolas Jaspert (eds.): Border areas and border crossings in comparison. The East and West of Medieval Latin Europe , Berlin 2007, pp. 123-143, ISBN 9783050041551 .

- Gabriele Schwarz: Textbook of General Geography. General Settlement Geography , Part 1: The Rural Settlements. The Settlements Standing Between Country and City , Berlin ⁴1988.

- Robert Müller-Sternberg: Deutsche Ostsiedlung, a balance sheet for Europe. 4th edition, Gieseking, Bielefeld 1975, ISBN 3-769-40033-X .

- Walter Schlesinger (Ed.): The German East Settlement of the Middle Ages as a Problem of European History (= lectures and research 18), Sigmaringen 1975.

- Klaus Dieter Schulz-Vobach: The Germans in the East. From the Balkans to Siberia. Hamburg: Hoffmann and Campe, 1989, ISBN 3-455-08331-5 .

- Klaus Zernack : Prussia - Germany - Poland. Essays on the history of German-Polish relations , ed. v. Wolfram Fischer and Michael Müller, Berlin 1991.

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ On the conceptual history of Christian Lübke : Ostkolonisierung, Ostsiedlung, Landesausbau in the Middle Ages. The ethnic and structural change east of the Saale and Elbe in the view of modern times. in: Enno Bünz : Eastern settlement and regional development in Saxony. The Kührener deed from 1154 and its historical context. Leipziger Univ.-Verlag, Leipzig 2008, pp. 467-484, in particular pp. 479-484.

- ^ Robert Bartlett (see literature), pp. 14 f, 213.

- ^ Werner Rösener: Agriculture, the agricultural constitution and rural society in the Middle Ages. Munich 1992, p. 17.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 147 f.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 148

- ^ Higounet, p. 93

- ↑ Corpus iuris Hungarici 1000-1526, S. Stephani I. Cap. 6)

- ↑ historical directory of Saxony http://hov.isgv.de/Dittmannsdorf_(2) , http://hov.isgv.de/Dittersdorf_(1) , http://hov.isgv.de/Dittersbach_(2)

- ^ Matthias Hardt , Hans K. Schulze : Altmark and Wendland as a German-Slavic contact zone. In: Settlement, Economy and the Constitution in the Middle Ages. Selected essays on the history of Central and Eastern Germany (= sources and research on the history of Saxony-Anhalt. Vol. 5). Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2006, ISBN 3-412-15602-7 , pp. 91-92 ( online on Google Books ).

- ↑ Charles Verlinden : Was Medieval Slavery a Significant Demographic Factor? In: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 66, Heft 2 (1979), pp. 153–173, here p. 161.

- ^ Association for Mecklenburg History and Archeology (ed.): Mecklenburgisches Urkundenbuch . Volume I (1863): Nos. 1-666 (786-1250). Schwerin 1863, p. 452 .

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 135

- ↑ Higounet, p. 88

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 149

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 160

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 146

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 155

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 161

- ↑ Joachim Schildt: Outline of the history of the German language, 3rd revised. Berlin 1984 edition.

- ^ Tomasz Czarnecki: The German loanwords in Polish and the medieval dialects of Silesian German (2006). In: German in contact between cultures. Silesia and other comparable regions, pp. 39–48

- ^ Germanisms in the Czech language

- ↑ Bünz, pp. 101-104 and Higounet, pp. 90-93.

- ↑ Helmold v. Bosau, Slawenchronik, Book I, Chap. 89.

- ↑ Bünz, pp. 104 f., 142.

- ↑ Helmold v. Bosau, Slavenchronik, Book I, Chap. 12.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 184 and Kuhn, p. 145 f.

- ↑ Brather, p. 33 f., Higounet, p. 266 f., Kuhn, p. 145 f.

- ↑ Bartlett, pp. 184-188 and Kuhn, p. 146.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 187 and Brather, p. 33 f.

- ^ Higounet, p. 268.

- ↑ Eberhard Kirsch: Comments on the change in utility ceramics during the state expansion in the 12th and 13th centuries in Brandenburg- in: The rural eastern settlement of the Middle Ages in northeast Germany. Investigations on the development of the country in the 12th to 14th centuries in rural areas , Felix Biermann, Günter Mangelsdorf (Ed.), Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 121–143, here: p. 127, Ulrich Müller: Craftsmen in the south of the Baltic rim. Two case studies - five theses , in: Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters 34 (2006), pp. 3–24, here: pp. 5–12 and Marian Rebkowski: Technology transfer as a factor in cultural changes in the Pomeranian region in the 13th century , in : Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters 34 (2006), p. 63–70, here: p. 63 f.

- ↑ Werner Troßbach, Clemens Zimmermann: The history of the village. 2006.

- ^ Martin Born: The development of the German agricultural landscape , 1989, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Martin Born: The development of the German agricultural landscape , 1989, pp. 18-22.

- ↑ Eike Gringmuth-Dallmer: Reversible plow and planned town? In: settlement research. Archeology-History-Geography 20, 2002, pp. 239-255.

- ^ Winfried Schenk: Historical geography. Darmstadt 2011, p. 34

- ^ Winfried Schenk: Historical geography. Darmstadt 2011, p. 34

- ↑ Higounet, pp. 272-295.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 326.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 320.

- ↑ Higounet, pp. 292-294.

- ↑ Bartlett, pp. 329-332.

- ↑ Higounet, p. 294.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 328.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 332 f.

- ↑ Danuta Janicka: On the Topography of the cities of Magdeburg Rights in Poland: the example Kulm and Thorn. In: Heiner Lück u. a. (Ed.): Foundations for a new Europe. Magdeburg and Lübeck law in the late Middle Ages and early modern times , Cologne a. a. 2009 (= sources and research on the history of Saxony Anhalt 6), pp. 67–81, here p. 68.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 339.

- ↑ Higounet, p. 317.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 393.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 396.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 320.

- ↑ Bartlett, p. 394.

- ^ Klaus Zernack: The millennium of German-Polish relationship history as a historical problem area and research task. In: Klaus Zernack, Wolfram Fischer (ed.): Prussia - Germany - Poland. Essays on the history of German-Polish relations. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-428-07124-7 , pp. 3–42, here pp. 6 and 8.

- ↑ Klaus Zernack: The high medieval state expansion as a problem of the development of East Central Europe. In: Ders .: Prussia - Germany - Poland. Essays on the history of German-Polish relations, ed. v. Wolfram Fischer and Michael Müller, Berlin 1991, pp. 171-183, here pp. 201 f.

- ^ According to Eike Gringmuth-Dallmer , Jan Klápště: Exposé on the publication project Tradition - Redesign - Innovation. Transformation processes in the high Middle Ages. Berlin, Prague 2009 (in preparation)