Second Polish Republic

| Rzeczpospolita Polska | |||||

| Republic of Poland | |||||

| 1918-1939/1944 | |||||

|

|||||

| Official language | Polish | ||||

| Capital | Warsaw | ||||

| Form of government |

parliamentary republic (1921–1926) semi-presidential republic (1926–1935) presidential republic / dictatorship (1935–1939 / 1990) government in exile in Angers, then London (1939–1945) |

||||

| Government system | parliamentary (1921–1926) authoritarian (1926–1945) |

||||

| Head of state | president | ||||

| Head of government | Prime Minister | ||||

| surface | 388,634 (1938) km² | ||||

| population | 27,177,000 (1921) 32,107,000 (1931) 34,849,000 (1938) |

||||

| Population density | 70 / km² (1921) 83 / km² (1931) 89 / km² (1938) inhabitants per km² |

||||

| Population development | 8.5% (between 1931 and 1938) per year | ||||

| currency | 1918 to 1924: Polish Mark 1924 to 1939: Złoty |

||||

| founding | February 20, 1919 (appointment of Pilsudski as head of state) March 17, 1921 (adoption of the “March constitution” by the Sejm) |

||||

| resolution | 1945 (or 1990) | ||||

| National anthem | Mazurek Dąbrowskiego | ||||

| Time zone | until 1922 no uniform time zone from 1922: UTC + 1 CET |

||||

| License Plate | 1918 to 1921: no uniform from 1921: PL |

||||

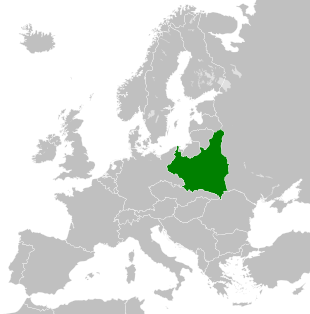

The re-establishment and history of Poland in the interwar period and during the Second World War is referred to as the Second Polish Republic ( Polish II. Rzeczpospolita ) . Formally, the period of the Second Polish Republic began on November 11, 1918 on the territory of Congress Poland or the Kingdom of Poland .

history

Independence and consolidation of the state

At the beginning of the First World War, the German Emperor Wilhelm II made the decision to found a Polish state in the conquered area of Congress Poland (at the time demoted to the Russian Vistula governorate).

After gaining military space in the east, the Central Powers Germany and Austria-Hungary proclaimed the establishment of an independent Kingdom of Poland (two emperor manifesto) from previously Russian territories, the so-called Regency Kingdom of Poland . Due to the events of the war, the resolution did not last longer.

In the last year of the First World War , in early 1918 in Brest-Litovsk , the Central Powers demanded a kind of state independence for Poland from Soviet Russia . The borders of Poland with Germany and Austria-Hungary were drawn even closer than in 1772 when Poland was first partitioned - that of the territory of Poland-Lithuania . The US President Wilson's 14-point program also envisaged an independent Polish state "which would have to include the areas that are undoubtedly inhabited by Polish people " and should have "free access to the sea".

In the peace of bread between the German Empire and Austria-Hungary and the Ukrainian People's Republic , the advocates of Ukrainian independence were assured of the Cholm governorate , which Poland also claimed. This resulted in protests and strikes, on February 18, for example, a nationwide strike in Galicia and a brigade of the Austro-Hungarian army switched to the enemy. Thereupon the Foreign Ministry declared in Vienna that provisions of the Bread Peace would not come into force immediately and would be examined by a commission. However, it was not until the military defeat of the Central Powers began to become clearly apparent on the Western Front in autumn 1918 and Russia had sunk into the chaos of civil war for a year that ethnic Poles regained full sovereignty in their own state - also thanks to the political support of the Western powers .

On October 7, 1918, the Regency Council in Warsaw proclaimed an independent Polish state and five days later took command of the army. The general active and passive right to vote for women was introduced at the same time as the corresponding right for men. This happened with the decree of November 28, 1918 on the election procedure for the Sejm shortly after the re-establishment of the Polish state. Article 1 guaranteed the active , Article 7, the passive right to vote .

As early as November 1918, Józef Piłsudski , who had been released from prison in Magdeburg, had taken power in Warsaw as “interim head of state”. His dismissal took place at the request of Polish independence advocates, who otherwise feared an uprising in Poland due to the poor living conditions. Such would have separated the German troops in the east, so that preventing the uprising was also in Germany's interest. Piłsudski had the Constituent Sejm elected on January 26, 1919 , who should draft and adopt a democratic constitution.

According to the provisions of the Versailles Treaty , Poland became an internationally recognized and independent republic in 1919 . After some pogrom - like anti-Semitic riots broke out in several cities , Poland had to sign a minority protection treaty on June 28, 1919, under pressure from American-Jewish representatives . This led to protests on the Polish side, as neither the Triple Entente nor Germany (with the exception of Upper Silesia in the form of the German-Polish Geneva Agreement of 1922) had to sign such an agreement. In the Sejm, however, 286 to 41 members voted for the treaty.

The border in the west was determined by the Treaty of Versailles, in which the two western powers of the partitions of Poland , Austria and Prussia's successor Germany, as defeated warring parties, had to make territorial concessions. In the east, however, Poland's border was unclear and controversial. Russia, which was one of the victorious allies, was not forced to make concessions under international law. Some advocates of a Polish revival took the military initiative and attacked Soviet Russia under the leadership of Marshal Józef Piłsudski's . In the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918-1919) Poland was able to record territorial gains. In 1919 the Polish-Soviet War began with fighting for the city of Vilnius (now Vilnius in Lithuanian ).

On April 21, 1920, Poland recognized the Ukrainian People's Republic under Symon Petljura . Linked to this was the idea of having an ally and a buffer state against Russia. In an additional agreement, Ukraine renounced eastern Galicia and Volhynia , both of which had predominantly Ukrainian populations , in favor of Poland , in return for support for the fight against the Red Army , which had occupied Ukraine. Poland then invaded the Ukrainian territories and occupied Kiev . The subsequent counter-offensive by the Red Army led them until shortly before Warsaw. Contrary to their expectations, the Red Army, like the Polish one in the Ukraine, received no popular support.

It was weakened by the very extensive front and was decisively defeated militarily in a counterattack by newly formed troops under Piłsudski and pushed back to a line that roughly corresponded to the German-Russian front of 1916. The Polish counterattack and victory near Warsaw became a “ miracle on the Vistula ” and became the founding myth of the Polish Republic. In 1921 the war ended with the Peace of Riga .

Poland had not achieved its main goal of regaining the territory of the Russian division, which was once part of Poland-Lithuania, albeit predominantly Ukrainian, or the establishment of a Ukrainian republic as a buffer state. Vilnius, the historic capital of Lithuania, but with a predominantly Polish and Jewish population, came to Poland together with the short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania . This put a permanent strain on relations with Lithuania and led to a break in diplomatic relations on the part of Lithuania. The eastern areas of Poland were ethnically heterogeneous, which in the future would require a balance between the interests of the different nationalities or would lead to new conflicts.

From 1921 good relations developed with Great Britain and France , who were interested in Poland primarily as a counterweight to Bolshevik Russia. Intensive relations developed with France in particular ( Kleine Entente ). In the Polish-Soviet War Britain and France supported Poland with arms deliveries in order to defeat Bolshevism with the Soviet Union. The showmen in Danzig had, however, in part striked to delete western arms deliveries in order to keep the front of the young Soviet Russia, the supposed workers' state, free from ever new weapons directed against it.

After the hopes of Poland to bring the port city of Danzig completely under control were not fulfilled and this had been declared the Free City of Danzig with a predominantly German population, who opposed the Polish state, the Polish state began building a new port in neighboring Gdynia .

In just a few years the fishing village with 1,000 inhabitants became a trading and military port with over 100,000 inhabitants, through which mainly the export of Polish agricultural products and coal from Upper Silesia took place. The competition with the Danzig harbor and the establishment of a Polish ammunition depot on the Westerplatte against the will of the Danzig Senate led to tensions.

On March 17, 1921, the Sejm adopted Poland's new constitution . This provided for two parliamentary chambers, with the Sejm with 444 deputies exercising the actual power, the Senate acting as a supervisory authority with the right to object. The Catholic Church had been given priority, but it was not a state religion. In mid-1923 the Sejm wanted to curtail the power of the Narrow War Council (Ścisła Rada Wojenna) , and thus Piłsudskis, whereupon Piłsudski angrily resigned from his military offices. But he was still in close contact with the military and politics.

The first years of independence passed with the internal structure of the state. The existing state structures, which the three different partitioning powers had left behind, had to be unified, but in some cases also created from scratch. Domestically, the years up to 1926 were therefore dominated by the succession of several parliamentary governments; In 1925 there were 92 registered parties, 32 of which were in parliament . Gabriel Narutowicz , a representative of the moderate left, was elected Poland's first official president in 1922 . However, Narutowicz was murdered by a nationalist fanatic a few days after his inauguration.

His successors chose the National Assembly the moderate socialists Stanisław Wojciechowski . Since the majority in the Polish Parliament (Sejm) was very unstable, the governments often took turns and were sometimes very weak.

Even in 1925, the state was still very heterogeneous due to the previous division. Although drastic changes were made with the adoption of social legislation, four different civil and criminal law systems continued to exist side by side. The broad-gauge railway network , as it partially existed in the former Congress Poland and was carried out throughout the formerly Russian division to the east, was converted to standard gauge until 1929 , as was the case throughout the formerly Prussian and formerly Austrian division.

Access from the rest of the German Reich to East Prussia , which had been geographically separated since 1919, was without entry into the unified Polish and Free City-Danzig customs area, only with a sealed corridor train from Konitz to Dirschau through the Polish Pomeranian Voivodeship on the Eastern Railway , by ship across the Baltic Sea through the East Prussian Sea Service or possible by air connection to the newly opened Königsberg Airport Devau in 1921 . In June 1925 a trade war began between Poland and Germany .

May coup and Sanacja regime

After a few years, Józef Piłsudski was dissatisfied with the unstable domestic political situation. Although he did not hold an official position in the army and state, he carried out a coup d'état in May 1926, based on his great authority among the people and the loyalty of the armed forces, and remained in power until his death in May 1935.

However, Piłsudski held here only rarely and only for a short time officially important offices. He was z. B. never president, but left this office to his loyal follower Ignacy Mościcki . Piłsudski was mostly just defense minister. However, he was the generally recognized supreme authority in the state. There was also a more or less functioning opposition, even represented in parliament, at least until the end of the 1920s, which, however, was consistently prevented from taking power.

With the beginning of the regime, repression began against the critics. Critical press reports were confiscated and corresponding editors were sentenced to several weeks' imprisonment. Also dismissing officials, banning assemblies, dissolving opposition organizations and the like. In 1928 , the Bezpartyjny Blok Współpracy z Rządem ( non-party block of government supporters ) was founded for the upcoming Sejm election . With the support of the administration, it achieved a quarter of the votes in the elections, with a turnout of 78%. At the same time, the relative election victory does not mean sufficient parliamentary power for Piłsudski's supporters.

When the Sejm brought charges against the Minister of Finance in 1929 for financing the Piłsudski Party's canvassing from state funds, the government threatened parliament, which culminated on October 31, 1929 with the deployment of armed men in the Sejm's foyer. The Sejm Marshal Ignacy Daszyński then refused to open the Sejm. At the end of August 1930 the parliament was dissolved and shortly afterwards 18 MPs, up to the elections in November a total of 84 former MPs were arrested. From now on Poland was governed by dictatorship .

After the assassination of Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki by a Ukrainian nationalist in 1934, the government set up an internment camp for Ukrainian nationalists, communists and other prominent opponents of the regime in the small town of Bereza Kartuska in what is now Belarus .

The "moral dictatorship" introduced while the constitution was formally retained called itself Sanacja ("rehabilitation" or "recovery") and was intended to lead to recovery after the alleged failure of the previous political system. A new constitution tailored to the person of Piłsudski came into force in April 1935 (" April Constitution "). However, the marshal died a few weeks later. The elections to the Sejm on September 8, 1935 were boycotted by the entire opposition, the turnout was only 43%.

After Piłsudski's death, the system that had hitherto been shaped by his personal prestige fell into disrepair, as the aspirants for his successor did not have the charisma and popularity of the national hero Piłsudski. Two centers of power emerged - the “Castle” group around Mościcki, named after the president's residence, the Warsaw Royal Castle , and the “Colonelists” group around the new Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły . The trend towards an authoritarian nationalist state now intensified. Rydz-Śmigły intensified fascist tendencies within the Sanacja in order to bring about an alliance with other fascist or fascistoid groups against his internal party opponents from the "castle". In the autumn of 1937 he even toied with a coup to establish a one-party system , but failed because of President Mościcki and his supporters.

According to the German historian Wolfgang Benz , the "fascist elements of the Polish dictatorship [...] are unmistakable" during this period. The British historian Norman Davies, on the other hand, denies that the regime can be called fascist, since the Polish sympathizers of fascism, for example within the Narodowa Demokracja , were in opposition to the regime and formally it did not represent a dictatorship. The Polish historian Jerzy Holzer sees tendencies towards the establishment of a fascist regime in Poland at the end of the 1930s, which were broken off by the German attack . However, they were by no means irreversible, since there was always strong resistance from the communist, socialist and democratic sides as well as from the Sanacja movement itself. British sociologist Michael Mann expects Poland under the Sanacja regime as well as Spain , Portugal or Yugoslavia to the states where the old regime was strong enough, the challenge posed by the global economic crisis withstand the 1930s and not fascist, but korpratistisch -autoritär were ruled.

The foreign policy efforts of Poland, which are primarily connected with the person of Foreign Minister Józef Beck , were, in line with French policy, aimed at creating a bloc of small and medium-sized states to contain both Germany and the Soviet Union. However, this was mainly hampered by the mutual territorial claims that had arisen after the First World War. For example, shortly before it was occupied by Germany and the Soviet Union, Poland actively participated in the smashing of Czechoslovakia and , according to the Munich Agreement , annexed the industrial areas around the city of Teschen (Těšín) , the so-called Olsa area, which were mostly populated by Poland at the end of October 1938 , and smaller areas in the border area with Slovakia .

population

numbers

Poland had 27 million citizens in the early 1920s (up from 32 million in the early 1930s). One third of the nationals belonged to national minorities. The 1921 census found the following ethnic groups in Poland:

- 18 million Poles (69.2%)

- 3.7 million Ukrainians (14.3%)

- 1.06 million Belarusians (3.9%) in north-eastern Poland

- 1.06 million Germans (3.9%) reside throughout Poland

- 2.7 million Jews (7.8%) mainly in eastern Poland

In 1919 there were about two million Germans on the territory of the Polish Republic. Around half emigrated in the first few years after the end of the war.

Minority policy

The minorities were theoretically protected by the Minorities Treaty of Versailles , the Constitution, the Peace of Riga and the Geneva Convention. The German minority in particular used the opportunity to appeal to international arbitration bodies. Between 1920 and 1930 there were over 1,200 petitions to the League of Nations , 300 of which came from Poland and almost half of them from the years 1931/32, when Poland and the Weimar Republic reached the climax of their conflict. Thus Poland was de facto a multinational state.

In official usage, however, the Polish character of the republic was emphasized. This led to considerable conflicts with the national minorities. The Ukrainians and Belarusians had no institutions of higher education. Government agencies also denied the Upper Silesians their special regional awareness. Poland was the state with the largest Jewish population in Europe.

In 1926 Michał Grażyński became a voivode of Silesia . He took action against the German school system, German landowners and large industrialists. Between 1926 and 1929 there were almost 100 complaints about violations of the German-Polish Geneva Agreement on Upper Silesia . The German parties increased their share of the vote in elections from 26% (1922) to 34% (1930). The share of the votes of German parties in Upper Silesia was well above the percentage of German speakers shown in the official statistics, which according to the 1931 census was 6.0% (in 1921 it was still 44.2%). This only led to the conclusion that many Polish-speaking Upper Silesians had also voted for German parties, which was something Polish nationalists were particularly angry about. The proportion only fell in 1930 after the opposition, not just the German, were massively hindered by the police and authorities. Poland was condemned by the League of Nations in January 1931 for this.

For central Poland ( Lodz area ) the German People's Association was represented in Poland in the Sejm and Senate. By reducing the Sejm from 444 to 408 seats, the minorities' chances of sending members to parliament decreased again in 1935.

In the Sejm, the Ukrainians fought, unsuccessfully, the school reform of 1925, during which the number of Ukrainian-speaking primary schools fell from 2,450 during the Habsburg era to 500 in 1937. At the same time, however, the number of bilingual schools rose from 1,426 to 2,710. The 600,000 Jews who emigrated from or returned to Russia in 1917/1919 received Polish citizenship between 1926 and 1928.

The Belarusians managed to improve their situation, at least in the short term. In 1929 a chair for Beloruthenistics was even established at the University of Vilnius . In Eastern Galicia, however, the Ukrainian minority was denied the promised Ukrainian University of Lviv . In the previously Russian Ruthenia, on the other hand, the authorities took a benevolent course. The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists was active in the south-east of the country and fought the Polish state with attacks and acts of sabotage, which led to Polish military actions.

On September 13, 1934, Poland announced the minority protection treaty and announced that it would only sign such an agreement again if there was a uniform one for all of Europe. The German-Polish Geneva Agreement on Upper Silesia expired in May 1937. A bilateral treaty was signed with Germany on November 5, 1937, which tied the protection of minorities to the protection of one's own compatriots in the other country.

The rights of the many minorities (especially Ukrainians, Belarusians and Germans) were severely restricted, and Jews in particular were discriminated against and persecuted. In 1936 the regime organized a boycott against the Jews, which was supported by the Catholic Church . Several dozen people were killed in the simultaneous pogroms. The Jews were blamed as scapegoats for negative side effects of modernity such as atheism , communism and pornography as well as for the structural problems from which the country's economy suffered in the interwar period . Various professional associations excluded Jews from membership following the example of the German Aryan paragraphs , and some universities introduced a numerus clausus for Jewish students. In March 1938, the Sanacja regime refused entry to 16,000 Jews with Polish citizenship who had been expelled from the country by the Nazi regime in the so-called Poland campaign and who were then stuck in the no man's land between Germany and Poland.

The German minority supported by the Nazi state came under the scrutiny of Polish intelligence agencies, despite the officially good German-Polish relations since the non-aggression treaty between Adolf Hitler and Piłsudski, to which the growing enthusiasm of many members of the German minority for National Socialism also contributed.

Conflicts with neighboring countries

The disintegration of the multi-ethnic monarchies in Central, Southern and Eastern Europe left behind a power-political vacuum that led to the emergence or re-emergence of eleven nation states , including Poland. This development was not always peaceful, so that there were a number of military conflicts over the redesign of the borders.

In the case of the Second Republic of Poland, these were the following conflicts:

- Poznan Uprising (1918-1919)

- Polish-Ukrainian War of 1918 and 1919

- Uprisings in Upper Silesia , three armed conflicts in Upper Silesia between 1919 and 1921

- Polish-Czechoslovak border war from January 23 to February 5, 1919 for the Olsa region and Teschen

- Polish-Lithuanian War against Lithuania , August 1920 to October 7, 1920

- Polish-Soviet War of 1920

So Poland was involved in conflicts over territories and ethnic minorities with almost every neighboring country. In the east, Poland had strengthened its borders after the fighting with Soviet Russia about 200 km east of the Curzon Line , which was not accepted by Poland and Soviet Russia . Warsaw only had tension-free relations with Romania and Latvia .

In total, the new state had almost 5,000 km of borders, of which only 350 with Romania and 100 km with Latvia did not border on opponents. As a result, about a third of government spending was managed by the Ministry of Military Affairs . Criticism of this high budget was not expressed by the opposition either. The Republic was initially a parliamentary democracy, but it was after the May Coup Józef Pilsudski in May 1926 in one of this authoritarian-run Sanacja converted regime with only a democratic facade. The actual end date is usually September 1, 1939, the beginning of the German invasion of Poland .

With Międzymorze , Piłsudski also proposed the concept of a Slavic-Baltic state in Central and Eastern Europe under Polish leadership that would stretch from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, which was rejected by the other nations.

The Polish Eastern Territories were assigned to Josef Stalin's sphere of interest in the division of interests agreed in the secret additional protocol to the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 24, 1939 ( fourth partition of Poland ). Stalin let the Red Army march there on September 17th , the areas remained with the Soviet Union as a result of the Second World War . He proposed to Poland the eastern German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line as compensation. The Western Allies of the anti-Hitler coalition agreed to this for the time being. Thus, against the will of the Polish as well as the German population, a complete reorganization of the borders took place with a resulting shift to the west of Poland .

Germany

There were disputes with Germany between 1919 and 1921, primarily over the possession of Upper Silesia . In the vote on March 20, 1921 , 59.6% of voters voted to remain with Germany. In some areas, the pro-Polish vote prevailed. In general, the pro-German share of the vote was particularly high in the cities and the pro-Polish in some rural eastern regions.

Polish irregulars thereupon began on May 3, 1921, aided by French occupation troops - Italians and British supported the German side - an armed uprising in order to forcibly enforce the annexation of at least parts of Upper Silesia to Poland. Due to the restrictions imposed by the Versailles Treaty, the German Reich could not take action against the militants, but with the approval of the Reich government, the Freikorps of the "Self-Protection of Upper Silesia" proceeded against the Polish rebels. There were bloody clashes between Germans and Poles. On May 23, 1921, the German Freikorps succeeded in storming the St. Annaberg , which stabilized the situation.

On October 20, 1921, the Supreme Council of the Allies, following a recommendation by the League of Nations, decided to transfer the East Upper Silesian industrial area to Poland, to which it was annexed as the Autonomous Silesian Voivodeship . The larger part of the voting area in terms of area and population remained with the German Reich - industrial cities such as Beuthen OS , Gleiwitz or Hindenburg OS remained German - but Eastern Upper Silesia with around 80% of the industrial area came to Poland. At the instigation of the League of Nations, both sides had to undertake to protect the respective national minorities in Upper Silesia ( Geneva Agreement ). The observance of this minority protection, contractually limited to 15 years, was in the following period a constant source of international tensions between Germany and Poland.

Most of the provinces of the Kingdom of Prussia, West Prussia and Posen, which had come to Prussia through the partition of Poland in 1772 and 1793, were detached from the German Empire and incorporated into the new Polish Republic without referendums . This gave Poland access to the Baltic Sea near Gdynia . The Polish military had already occupied some of the areas during the Wielkopolska uprising .

The old Hanseatic city of Danzig, which Poland had hoped to acquire, was declared a Free City of Danzig by the Allies and remained with Poland's rights of use at the Danzig port and inclusion in the Polish customs area, but outside the borders of the new Polish state, under the supervision of the League of Nations . Due to the non successful acquisition and the negative attitude of the German population of Danzig Poland started few kilometers on Polish territory in Gdynia ( Gdynia ) with the construction of a new port, which quickly developed to the competition for Gdansk.

For other areas, the Versailles Treaty provided for referendums on nationality. In Masuria ( Olsztyn administrative district ) and in the Marienwerder district (formerly West Prussia), referendums took place under Allied supervision, in which the large majority of the population (98% and 92%, respectively) decided to remain with East Prussia and Germany.

Lithuania and Ukraine

Polish efforts to restore its historical borders from 1772 also met resistance in Lithuania and Ukraine and endangered especially Ukrainians and Lithuanians . A week after the Polish declaration of independence, the Ukrainians in Lviv also proclaimed their independence. In the Polish-Ukrainian War, around the former Habsburg Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria , Poland expanded its territory eastward into the Ukraine. Particularly fierce fighting was waged around Lemberg, which was captured by Polish volunteer units and regular army units on November 21. The war lasted until March 1919 and was only officially ended on April 21, 1920 by an agreement between Poland and the People's Republic of Ukraine under Symon Petljura .

Jews living in western Ukraine were also attacked by Polish soldiers. When Lemberg, after some fierce fighting on 21/22 After being captured by Polish troops on November 22nd, 1918, a pogrom broke out on the town's Jewish community from November 22nd to 24th.

The League of Nations, established with the Treaty of Versailles, envisaged the drawing of a border line based on the recommendations presented in December 1919 by a commission headed by the British Foreign Minister Curzon , through which the Polish state would lose the majority of Polish-speaking areas around Vilnius in Lithuania and Lemberg in Galicia .

Piłsudski's more far-reaching plans were also aimed at the re-establishment of a republic under Polish leadership in the tradition of the aristocratic republic that fell in 1795 and which should also include areas inhabited by the majority of Ukrainians and Belarusians . Polish troops therefore occupied the eastern part of Lithuania around Vilnius in 1919 , which had just achieved independence against Russia, as well as temporarily Kiev in the Ukraine, which led to the Polish-Soviet war due to the overlap with the territorial claims of Soviet Russia.

Soviet Union

First, the Polish troops under General Rydz-Śmigły advanced as far as Kiev with the support of national Ukrainian forces. The quick success was facilitated by the evasion of the Soviet troops, who launched a counter-offensive after the conquest of Kiev by the Poles. The Soviet units under General Tukhachevsky advanced as far as Warsaw, while General Budjonny besieged Lemberg.

By a daring pincer maneuver succeeded Polish army under Pilsudski command of the breakthrough and an almost complete destruction of the Soviet units: While the Polish units tried the army of General Tukhachevsky in Radzymin stop northeast of Warsaw, Pilsudski launched from the river Wieprz in the Lublin Region a Major offensive to the north. The surprise effect was so great that the last retreating units of the Red Army had to flee via German territory - East Prussia.

In 1921 the warring parties concluded a peace treaty in the Latvian capital Riga , whereupon the internal reconstruction of Poland began. Piłsudski missed his goal of reestablishing the state border of 1772, but succeeded in expanding the Polish state border about 200 km east of the Curzon Line , the closed Polish language border with a relative majority of the population.

In the eastern part of Poland the Polish population was around 25% in 1919, and 38% described themselves as Polish in 1938. The remaining portion was made up of other nationalities. The majority of the population described themselves as Ukrainian, Belarusian or Jewish. The cities of Wilna and Lemberg, on the other hand, were mostly Polish - with a high proportion of Jews.

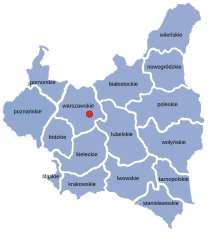

Administrative division

The national territory was divided into 16 voivodeships and the equivalent capital Warsaw. The boundaries of these administrative units were initially based on the former German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian administrative borders, but on April 1, 1938 there were some reallocations of areas.

- Białystok Voivodeship

- Kielce Voivodeship

- Krakow Voivodeship

- Lublin Voivodeship

- Lviv Voivodeship

- Łódź Voivodeship

- Nowogródek Voivodeship

- Polesian Voivodeship

- Pomeranian Voivodeship

- Poznan Voivodeship

- Stanislaw Voivodeship

- Tarnopol Voivodeship

- Warsaw Voivodeship (Country)

- Warsaw (city)

- Vilnius Voivodeship

- Volyn Voivodeship

economy

The fighting of the First World War on the front, which had been relocated several times on the soil of what would later become the Polish state, had left heavy destruction. Only in the formerly Prussian partition area had there not been any fighting. In central Poland, over 1.75 million civilians had been evacuated to Russia and industrial facilities dismantled. The Austrian and German occupiers had confiscated large parts of the harvest and industrial production and deported civilians to their national territories for forced labor.

Overall, the area of what would later become Poland lost two to three fifths of its livestock during the World War, grain and potato production fell to around half, and wheat production fell to a third of the pre-war level. It is estimated that by November 1918 only 15 percent of the 1913 workers were still working in industry. About half of the bridges and almost two thirds of the stations were destroyed. Because of the partitions of Poland , the parts that were now reunified in one state had developed very differently. In simplified terms, a distinction was made between the comparatively well-developed Poland A and the backward Poland B with the dividing line on the Vistula .

The labor and social legislation of the Second Polish Republic was among the most modern of the time. In 1918/1919 decrees were issued on the 8-hour working day , trade unions, health insurance and labor inspection. In 1920 there followed laws on health insurance , working hours and in 1922 on vacation entitlements. From mid-October to the end of November, the number of registered unemployed rose from 200,000 to 300,000.

The state budget was in deficit, in 1921 40 percent, in 1922 51 percent of the expenditures were covered. Throughout the state's existence, the Ministry of Military Affairs consumed up to a third of the state budget.

currency

The Polish mark was introduced on January 15, 1920 , previously there were six valid currencies in the state. Between Wincenty Witos' assumption of government activity in May 1923 and August 1, 1923, the exchange rate between the mark and the US dollar fell from 1: 52,000 to 1: 230,000. This is seen as the beginning of hyperinflation in the Polish Republic. In December 1923 the exchange rate had already climbed to 1: 4.3 million. On February 1, 1924, Bank Polski was founded, which was largely independent of the government. In April 1924 the złoty (i.e. guilder) was introduced and the Polish mark was completely replaced by the middle of the year.

Agriculture

At the beginning of the 1920s, three quarters of the population lived from agriculture, with many small farms dominating the picture. A third of the agricultural enterprises cultivated less than two hectares (a total of 3.5% of the arable land), a further third less than five hectares (14.8%) only 0.9 percent of the companies owned more than 50 hectares (47.3% of the Soil). The most important landowners were the Zamoyski families , with 191,000 hectares, and Radziwiłł , 177,000 hectares. By 1923, agriculture had returned to pre-world war levels in most areas.

There were several approaches to land reform from 1919 , but it was not until 1925 that Władysław Grabski was able to successfully enact an effective law. He converted a decree of 1923 into law, according to which the large landowners had to transfer at least 200,000 hectares annually to smallholders for full compensation.

Industry

During the division, industry was geared to the needs of the partitioning powers and was not very export-oriented, perhaps apart from the Prussian partition. In addition, it was insufficiently funded. About 40 percent of the industry was ruled by cartels. The state was an important factor in the economy through Bank Polski and through state monopolies . About 30 percent of government revenue was generated in state-owned companies. The number of industrial workers, excluding Upper Silesia, quintupled between 1919 and 1922, but remained below the number of 1913. Real wages also rose, reaching 98 percent of 1914 incomes in mid-1921.

Industrial production rose and in 1929 reached 143% of the 1926 level. The economic and trade war of 1925 and the loss of imports promoted the establishment of Polish electrical, chemical and optical companies. Although coal exports were initially affected by the trade war, the British miners' strike in 1926 led to increased demand and an increase in coal production by almost 60% by 1926.

Infrastructure

The infrastructure, as it was previously geared towards the respective dividing power, was poorly connected to one another. There was no direct rail connection from the coal fields in the south of the country to the emerging port in Gdynia or the existing Danzig . Many routes were significantly longer than necessary due to war damage and unfavorable routes. The journey from Warsaw to Lviv, about 400 kilometers away, took 12 hours until 1925, and 9 hours from the summer of that year.

education

- See also: Education system in Poland

The Second Polish Republic quickly expanded its higher education system. In addition to the existing universities in Krakow , Warsaw and Lviv, the Catholic University of Lublin was added in 1918 , the re-established University in Wilno in 1919 and the University of Poznan in the same year . In 1920 a framework law for universities was passed.

In 1923, one third of the population was illiterate , although the distribution varied widely. In the previously Russian East, Polesia and Volhynia , this was up to 50%, in the Polish part of Upper Silesia only 1.5%. In the east of Poland, compulsory schooling was introduced in 1919, which meant that the number of teachers and students rose by two thirds within four years. Nevertheless, around 40% of school-age children did not attend school in the mid-1920s, and the ratio of teachers to the population reached 70% of the areas of central Poland and about half of the areas of western Poland.

literature

- Manfred Alexander : Small history of Poland . Updated and expanded edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-017060-1 (= Reclams Universal Library , 17060).

- Werner Benecke : The Eastern Territories of the Second Polish Republic. State power and public order in a minority region 1918–1939 Böhlau, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-412-01199-1 (= contributions to the history of Eastern Europe, volume 29).

- Włodzimierz Borodziej : History of Poland in the 20th Century. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60648-9 .

- Norman Davies : God's Playground. Columbia University Press, New York 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3 ( Google Books ).

- Rudolf Jaworski , Christian Lübke , Michael G. Müller : A little history of Poland . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-518-12179-0 (= Edition Suhrkamp , Volume 2179).

- Hartmut Kühn : Poland in the First World War: The struggle for a Polish state up to its re-establishment in 1918/1919 , Peter Lang Verlag Berlin 2018, ISBN 978-3-631-76530-2

Web links

- Module Second Polish Republic of Documents and Materials on East Central European History ( Herder Institute )

- Time travel blog: Poland 1918–1939: Between Democracy and Dictatorship. ( Memento from July 1, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ From 1939 to 1944 the Second Polish Republic was occupied by Germany and the Soviet Union. The Polish government in exile first took its seat in Angers / France (until 1940) and then in London . The People's Republic of Poland from 1944 is considered the successor state , although the government-in-exile in London maintained its claim to be the legitimate representative of Poland until 1990.

- ^ Law of March 17, 1921, regarding the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. Retrieved December 16, 2012 .

- ↑ Keya Thakur-Smolarek: The First World War and the Polish Question: The interpretations of the events of the war by the contemporary Polish spokesmen. Berlin 2014.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 88.

- ^ Blanca Rodríguez-Ruiz, Ruth Rubio-Marín: Introduction: Transition to Modernity, the Conquest of Female Suffrage and Women's Citizenship. In: Blanca Rodríguez-Ruiz, Ruth Rubio-Marín: The Struggle for Female Suffrage in Europe. Voting to Become Citizens. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden and Boston 2012, ISBN 978-90-04-22425-4 , pp. 1-46, p. 46.

- ↑ Malgorzata Fuszara: Polish Women's Fight for Suffrage. In: Blanca Rodríguez-Ruiz, Ruth Rubio-Marín: The Struggle for Female Suffrage in Europe. Voting to Become Citizens. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden and Boston 2012, ISBN 978-90-04-22425-4 , pp. 143–157, p. 150.

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 310.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, pp. 92–93.

- ^ N. Pease: "This Troublesome Question": The United States and the "Polish Pogroms" of 1918-1919. In: MBB Biskupski (Ed.): Ideology, Politics, and Diplomacy in East Central Europe. University of Rochester Press, 2004, ISBN 1-58046-137-9 , pp. 58 ff.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, pp. 107-108.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, pp. 112–117.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 118.

- ↑ Wojciech Antoszkiewicz, Mariusz Jablonski, Bogdan Kwiatkowski u. a .: Gdynia: Tourist Vademecum [uniform title: 'Gdynia: vademecum turysty'; Ger.], Jerzy Dąbrowski (trans.), Gdynia Turystyczna, Gdingen 2009, ISBN 978-83-929211-0-3 , p. 12.

- ↑ a b c Manfred Alexander: Small history of Poland. 2008, pp. 286-287.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 149.

- ^ "Polska - koleje" , on: Encyklopedia Gutenberga online , accessed on November 29, 2018.

- ^ Theodor Schieder. (Ed.): Handbook of European history - Volume 7 Europe in the age of world powers. 1996, ISBN 3-12-907590-9 , p. 1006.

- ^ A b Dieter Bingen: Poland: 1000 years of eventful history. (PDF) In: Information on Political Education No. 311/2011. P. 8 , accessed October 1, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c d e Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, pp. 169–176.

- ^ Jerzy Holzer: The Political Right in Poland, 1918-39. In: Journal of Contemporary History 12, No. 3 (1977), pp. 395-412, here p. 408.

- ↑ Stephen J. Lee: European Dictatorships, 1918-1945 . Routledge, London / New York 2000, p. 270.

- ^ Jerzy Holzer: The Political Right in Poland, 1918-39. In: Journal of Contemporary History 12, No. 3 (1977), pp. 395-412, here pp. 409 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz: Fascism . In: the same (ed.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus , Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 86 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Norman Davies: In the Heart of Europe. History of Poland. Fourth, revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Jerzy Holzer: The Political Right in Poland, 1918-39. In: Journal of Contemporary History 12, No. 3 (1977), pp. 395-412, here p. 410 f.

- ↑ Michael Mann: Fascists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2004, p. 363.

- ↑ Eugenjusz Romer : Powszechny Atlas Geograficzny. Książnica-Atlas, Lwów-Warszawa 1928, map 48

- ^ Atlas Historyczny Polski. PPWK Warszawa-Wrocław 1998, p. 46.

- ↑ a b c d e Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, pp. 132-133.

- ^ Richard Blanke: Orphans of Versailles: The Germans in Western Poland 1918–1939 . The University Press of Kentucky, 1993, ISBN 0-8131-1803-4 . Appendix B: Population of Western Poland and Chapter 4: The Piłsudski Era and the Economic Struggle p. 90 ff.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, p. 169.

- ↑ Philipp Heyde: The end of the reparations. Germany, France and the Young Plan 1929–1932. Schöningh, Paderborn 1998, p. 118.

- ^ Christian Jansen and Arno Weckbecker: The "Volksdeutsche Selbstschutz" in Poland 1939/1940. Oldenbourg, Munich 1992, ISBN 978-3-486-70317-7 , p. 19 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ a b c Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 165.

- ^ Gertrud Pickhan: Poland . In: Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Vol. 1: Countries and regions. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-598-24071-3 , p. 281; Wolfgang Benz: Fascism . In: the same (ed.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus, Volume 3: Terms, Theories, Ideologies. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-023379-7 , p. 86 (both accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Marek Kornat: The rebirth of Poland as a multinational state in the conceptions of Józef Piłsudski. Forum for Eastern European History of Ideas and Contemporary History, 1/2011

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, pp. 97–99.

- ↑ a b c d Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ a b c d Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 144.

- ↑ a b Manfred Alexander: Brief history of Poland. 2008, pp. 288-289.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, pp. 137-139.

- ↑ a b Manfred Alexander: Brief history of Poland. 2008, p. 290.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 156.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th Century. Munich 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: History of Poland in the 20th century. Munich 2010, p. 166.