Edward I (England)

Eduard I. , English Edward I , also called Edward Longshanks (Eduard Langbein) and Hammer of the Scots (hammer of the Scots) (* June 17 or June 18, 1239 in Westminster ; † July 7, 1307 at Burgh by Sands ), was King of England , Lord of Ireland and Duke of Aquitaine from 1272 until his death . As a young heir to the throne, Eduard made a major contribution to the victory of the royal party in the Second Barons' War in 1267. After returning from his crusade , he took control of England in 1274. Through a series of reforms and new laws, he strengthened the royal authority over the barons. In two campaigns by 1283 he conquered Wales, which had been largely autonomous until then. Although the attempt to subordinate the previously independent Kingdom of Scotland to his direct supremacy from 1290 failed, he is considered one of the great medieval monarchs of England.

Edward I was not the first English king to use this name, but the French tradition of numbering identical royal names was only introduced in England after the Norman conquest of England in 1066 by William the Conqueror . That is why the Anglo-Saxon monarchs Edward the Elder , Edward the Martyr and Edward the Confessor are not counted in today's chronology.

Childhood and youth

Edward I came from the Anglo-Norman dynasty Anjou-Plantagenet . He was born on the night of June 17-18, 1239 as the first child of King Henry III of England . and his wife Eleanor of Provence . His father named him after the canonized King Edward the Confessor, whom he particularly admired . The birth of the heir to the throne initially sparked great enthusiasm, but this quickly subsided when the king, who was already in financial distress, declared that he was demanding gifts from his subjects on the occasion of the birth. The heir to the throne soon had his own household, in which he was brought up together with other children of the high nobility, including his cousin Henry of Almain . Initially, Hugh Giffard was responsible for the heir to the throne until he was replaced by Bartholomew Pecche in 1246 . Henry III. regularly supervised the upbringing of his heir. At least in 1246, 1247 and 1251 the boy became seriously ill, but grew up to be a healthy and handsome young man. At the age of seventeen he took part in a tournament in Blyth .

Eduard as heir to the throne

Lord of Aquitaine, Ireland and areas of Wales and England

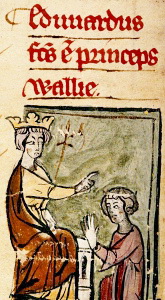

As heir to the throne, Eduard did not have his own title, but was simply called Dominus Edwardus or Lord Edward . When in 1254 an invasion of the English king Gascony by the neighboring Castile was feared, the plan arose to marry Edward to Eleonore , daughter of King Alfonso X of Castile , in order to improve relations between the two empires. The Castilian king wanted his son-in-law to own a sizeable estate himself, so that Henry III. Gascogne to his son, the Lordship of Ireland and an extensive property in the Welsh Marches with the Earldom Chester and Stamford and Grantham as appanage . The wedding then took place on November 1, 1254 in Burgos , northern Spain . Although Eduard was supposed to manage the estates he had received from his father himself, it was not until 1256 that he was given control of Ireland. Even after that, the king occasionally intervened in the rule of his son. The king and Edward had different ideas about rulership in Gascon in particular. While the king pursued a conciliatory policy after the rebellion from 1253 to 1254, Eduard resolutely supported the Soler family from Bordeaux , which angered other influential families.

From his Welsh possessions Edward earned an annual income of about £ 6,000. This was apparently not enough to cover his expenses, because in 1257 Edward had to sell the lucrative guardianship administration for Robert de Ferrers for 6,000 marks and get himself from Boniface of Savoy , the archbishop borrow another £ 1000 from Canterbury. The strict rule of Edward's officials in Wales, who, like Geoffrey de Langley, pursued the enforcement of the English feudal system , led to a Welsh revolt in 1256 . A campaign by the king against the rebels in North Wales failed in 1257, so that large areas of Edward's possessions in Wales were lost to the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd .

Involvement in the power struggles at the royal court

At that time there was a rivalry at the royal court between the relatives of Queen Eleonore from Savoy and the Lusignans from south-west France, the king's half-siblings and their respective supporters. From 1254 onwards, Eduard was politically influenced primarily by his mother's relatives, who in addition to Archbishop Boniface of Savoy, especially Peter of Savoy belonged. From 1258, however, Eduards sympathy switched to the Lusignans. He pledged his English possessions Stamford and Grantham to William de Valence and wanted Geoffrey de Lusignan to Gascony Seneschal and his brother Guy as the administrator of the Ile de Oléron and the Channel Islands appoint. Through this promotion of the Lusignans, which were particularly unpopular in England, the popularity of the heir to the throne also fell.

Involvement in the power struggle between the aristocratic opposition and the king

From opponent to supporter of the reform program of the aristocratic opposition

Against the unsuccessful policy of Heinrich III. In the spring of 1258, a powerful aristocratic opposition formed which called for a reform of the government. After the king, under the pressure of the aristocratic opposition, had agreed to the development of a reform program, the young heir to the throne had to agree to this project, albeit with considerable reluctance. During the Parliament of Oxford in May 1258 was this reform program, called Provisions of Oxford presented. One of the main demands was that the Lusignans had to leave England. Eduard then openly sided with the Lusignans, fled with them from Oxford at the end of June and holed up in Winchester . Just a few days later, however, they had to surrender to the militarily superior barons. While the Lusignans had to leave England, Eduard swore on July 10th to comply with the Provisions of Oxford. John de Balliol and Roger de Mohaut , two supporters of the aristocratic opposition , as well as his former officials John de Gray and Stephen Longespée were to advise Eduard and try to change his mind in favor of the barons. When the new government set up by the aristocratic opposition had increasing success, Eduard's attitude to the reform movement changed. He surrounded himself with a new retinue of young barons, including his cousin Henry of Almain, John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey , Roger de Clifford , Roger of Leybourne and Hamo le Strange . In March 1259, Edward officially allied himself with Richard de Clare, 5th Earl of Gloucester , one of the leaders of the aristocratic opposition. It is possible that Eduard sought the support of Gloucester, especially as lord of Gascony, because Gloucester was one of the negotiators who were supposed to negotiate a peace treaty with France. When especially young barons protested against the reform movement in October 1259, Eduard replied that he had meanwhile firmly stood by the oath he had taken in Oxford on the reform program. Possibly he was heavily influenced by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester , who was married to Edward's aunt Eleanor and who had become one of the most important leaders of the aristocratic opposition.

When the king was in France from November 1259 to recognize the peace treaty , Eduard tried to act independently in England without consulting his father. The disappointed king, who continued to secretly try to regain his power, was now convinced that his son wanted to overthrow him. When he returned to England in April 1260, he initially refused to see Edward. Only through the mediation of his brother Richard of Cornwall and Archbishop Boniface of Savoy could the two be reconciled. Edward's temporary rift with the Earl of Gloucester was also settled. Edward's henchmen Roger of Leybourne, whom he had appointed in command of Bristol Castle , and Roger de Clifford, who commanded the strategically important three castles Grosmont , Skenfrith and White Castle in Wales, were replaced.

Stays in France and approach to the politics of the king

After the reconciliation with his father, Eduard traveled to France in 1260, where he took part in several tournaments. In autumn 1260 he returned to England, but in November 1260 he traveled to France again, where he met the exiled Lusignans. In the spring of 1261 Edward returned to England, where it briefly seemed that he would again support the barons around Gloucester and Montfort. Shortly thereafter, however, he supported his father's policy before he left for his rule Gascony in July 1261. There he succeeded in consolidating English rule and pacifying the troubled province. When he returned to England in early 1262, he accused Roger of Leybourne, whom he had appointed as administrator of his English possessions, to have embezzled funds. Eduard found him guilty and dismissed him from his service. This led to a break with many of the young barons who had previously supported him. Henry of Almain, John de Warenne and Roger de Clifford in particular were convinced of Leybournes innocence and no longer supported the heir to the throne. To prevent further embezzlement and mismanagement, Eduard returned most of his lands to his father. In return, he received the protection money that the English Jews had to pay to the crown for three years. Apparently he had fallen out of favor with his father, because shortly afterwards he traveled back to France in 1262, where he presumably again participated in various tournaments in Senlis and other places.

Determined supporter of his father

When Edward returned to England in the spring of 1263, he tried to curb the growing power of the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd. This had exploited the political weakness of the English king and brought large parts of Wales and the Welsh Marches under his control in a war with England . In April and May 1263 Edward led a campaign to Wales, but although he was supported by Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd , the expedition was unsuccessful. In addition, the situation of the king in England deteriorated after Simon de Montfort, who had also left England in 1261, returned in the spring of 1263. The Earl of Gloucester had died in 1262, and Montfort was now the undisputed leader of the aristocratic opposition, which wanted to restrict the rule of the king again. Eduard now stood resolutely on his father's side. When he traveled to Bristol , the behavior of his entourage led the citizens of the city to besiege him at Bristol Castle . It was only after Bishop Walter de Cantilupe of Worcester brokered a truce that he was able to escape the castle. To the indignation of the aristocratic opposition, he reinforced the garrison of Windsor Castle with foreign mercenaries. As the king's financial situation remained extremely tense, Eduard illegally confiscated part of the treasures that had been deposited with the Knights Templar in the New Temple in London. When on July 16, 1263 the king had to give in again to the demands of the aristocratic opposition in the face of political pressure, Eduard continued his resistance. In August he resumed contact with his former supporters Henry of Almain, John de Warenne and Roger of Leybourne and dismissed the unpopular foreign mercenaries. In October 1263 the attempt at an understanding between him and the barons failed during parliament. Eduard then plundered Windsor Castle, which he had shortly before handed over to the government of the aristocratic opposition. Only after lengthy negotiations were the parties to the conflict able to agree that they would receive an arbitration verdict from the French King Louis IX. would accept. Eduard accompanied his father to France at the end of 1263, where Louis IX. in the Mise of Amiens in January 1264, as expected, decided in favor of the position of the English king.

The Barons' War

However, the Mise of Amiens did not end the conflict between the king and the aristocratic opposition, but rather expanded it into open civil war. Edward himself was actively involved in the first fighting when he tried to retake the rebel-occupied Gloucester . When a relief army moved under his former ward Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby to relieve the city, Eduard concluded a truce. When Ferrers withdrew, however, Eduard had the city plundered. He then moved to Northampton , where he made a decisive contribution to the conquest of the city, which was occupied by a rebel garrison. Then Eduard left the royal army and plundered the property of the Earl of Derby. Now the royal troops turned against the City of London , whose citizens remained determined to support the rebels. Montfort went against the royal troops, which led to the Battle of Lewes on May 14, 1264 . Eduard had previously rejoined the royal army. The cavalry attack of the right wing of the royal army led by him destroyed the left wing of the rebel army, but afterwards his knights pursued the fleeing opponents. When Eduard returned to the battlefield with his troops, Montfort had in the meantime defeated the main royal army. After lengthy negotiations, Eduard surrendered. Eduard was to be held hostage for the good behavior of the king, who also came under the control of the aristocratic opposition, until he accepted the government of the barons led by Montfort. For safety he had to hand over Bristol Castle and five other royal castles to the government for a period of five years. He was then officially released, but remained under close supervision by supporters of Montfort. Over time this supervision relaxed, and when Eduard went out on horseback in May 1265, he was able to escape his guards, who included Thomas de Clare and Henry de Montfort , at Hereford . He fled to Wigmore Castle to meet Roger Mortimer , an opponent of the government of the barons, then he joined Gilbert de Clare , the young Earl of Gloucester, who had fallen out with Montfort the previous year. The Marcher Lords and other supporters of the royal party quickly joined them, and finally they united their army with the small contingent of John de Warenne and William de Valence, who had landed in Wales from exile in France. Without a fight they moved into Worcester , while Gloucester Castle was captured after a heavy siege. Montfort, who had moved to the Welsh Marches with an army, allied himself on June 19 with Lord Llywelyn ap Gruffydd. The royal party destroyed the bridges over the Severn , so that Montfort in the Welsh Marches was cut off from further reinforcements. One of Montfort's sons, Simon de Montfort the Younger , reached Kenilworth Castle with his troops . On a night march from Worcester, Eduard and his troops surprised the rebels encamped in front of the castle and drove them to flight. Then he moved towards the older Montfort. On August 4, 1265, Gilbert de Clare and Eduard were able to decisively defeat the rebel army under Montfort in the Battle of Evesham . What part Eduard had in the triumphant victory, however, can no longer be clarified.

Even if the Battle of Evesham had decided the Second War of the Barons militarily, it could not end the war. The main reason for this was the ruthless treatment of the surviving rebels, who were declared expropriated by the victorious royal party. The so-called disinherited therefore desperately continued the rebellion. Eduard himself took a hard line against the disinherited and at the end of 1265 led a campaign against the Isle of Axholme in Lincolnshire , where Simon de Montfort the Younger had fled. Due to his military superiority, Eduard Montfort was able to force himself to give up at Christmas 1265. Then turned Eduard together with Roger of Leybourne against the Cinque Ports , which surrendered to him before March 25, 1266. After that, Eduard took action against the disinherited in Hampshire . He defeated the well-known rebel Adam Gurdun , a knight, in a duel. Legend has it that Eduard was so impressed by Gurdun's bravery that he returned his lands to him. In fact, Eduard handed his prisoner over to the queen, and Gurdun only got his possessions back against a heavy fine. In May 1266 Edward joined the siege of Kenilworth Castle, where a large number of the disinherited had holed up. Eduard, however, had neither the siege nor the drafting of the Dictum of Kenilworth , which was to reconcile the disinherited with the king. Even before the Kenilworth garrison surrendered in December 1266, Edward had moved to northern England, where he put an end to the revolt of John de Vescy . To redeem his land, Vescy had to pay a heavy fine of 3,700 marks . Nevertheless, he reconciled himself with Eduard and became one of his closest followers. The last rebel group was led by John de Deyville . This received support from the Earl of Gloucester, who together with the rebels occupied the City of London in April 1267. He wanted to extort better conditions from the king for the disinherited. Gloucester had played a large part in the royal party's victory in 1265, but had received little rewards from the king thereafter. Due to his alliance with the disinherited there was a danger that civil war could break out again. After negotiations, Gloucester finally left London while the king made concessions to the disinherited. Eduard was now proceeding against the last rebels who had withdrawn to the Isle of Ely . Due to the dry summer, the wetlands of the Fens were not an obstacle for Edward's troops, so the disinherited surrendered in Ely on July 11th.

England after the civil war

In order to secure the position of the king after the end of the civil war, important measures were taken in autumn 1267. On September 29, 1267, the Treaty of Montgomery was signed, which ended the Anglo-Welsh War. Not only was Llywelyn ap Gruffydd recognized as Prince of Wales , but Eduard also renounced Perfeddwlad, which Llywelyn had conquered in north-east Wales in 1256 . As early as 1265 Eduard had given his remaining Welsh possessions Cardigan and Carmarthen to his brother Edmund . In November 1267 the Marlborough Statute was enacted, which took up numerous legal reforms of the former aristocratic opposition. In many ways it prepared laws to be enacted during Edward's reign, but again it is unclear to what extent Edward participated in the many provisions of the Marlborough Statute. Indeed, little is known of Edward's role in the years following the Barons' War, and his known actions have not always been well received. He continued to have a strained relationship with the Earl of Gloucester. Among other things, the possession of Bristol was disputed between them, and when Eduard had the conflict between the Marcher Lords and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd investigated in 1269, he snubbed Gloucester. In 1269 he supported the harsh treatment of his former ward Robert de Ferrers, the former Earl of Derby. He had to accept an enormous debt of £ 50,000 to Edward's brother Edmund for his release, which effectively expropriated him. Otherwise, Eduard took part in tournaments, but also took on debts that Christians had with Jewish moneylenders, and drove them back at a profit. The king had endowed him with numerous estates, including oversight of the City of London, seven royal castles and eight counties. He apparently needed the income from these properties to pay off the debts he had incurred in the war of the barons. Despite these extensive holdings and although he was often involved in leading discussions in the Privy Council , Eduard's political influence remained limited. Instead of the aging king, the papal legate Ottobono and Edward's uncle Richard of Cornwall had greater political influence. Eduard, on the other hand, concentrated on preparing for his crusade after taking a crusade vow at Ottobono's instigation in June 1268 .

Edward's crusade

Preparing for the Crusade

Edward's father Heinrich III. had already made a crusade vow in 1250, but had not yet redeemed it. Usually his second son Edmund could have undertaken the crusade on his behalf. It is unclear why the heir to the throne, Eduard, also made a vow of crusade. The Pope actually considered Edward's presence in England to be necessary because of the political situation that remained tense after the barons' war. But now Edward was determined to lead the crusade. Maybe he wanted to escape the problems in England, maybe he felt hurt in his honor, because not only the French king, but also his sons wanted to embark on a crusade. With Eduard and Edmund, both sons of the English king wanted to embark on the crusade.

Travel to Tunis and on to the Holy Land

Since both the financing and the recruitment of soldiers for the crusade were difficult after the long civil war, Eduard left England in the summer of 1270 with only a relatively small army to travel to the Holy Land . However, he wanted to unite with the crusader army of the French king . But when Eduard and his troops reached the French army at Tunis , Louis IX was. of France died of an epidemic that attacked numerous other French soldiers. The French therefore signed an armistice on November 1st and had to retreat to Sicily, where the French broke off the crusade. Eduard, however, traveled on to Acre with his contingent in 1271 . Once there, however, he had to realize that he could do little with his few crusaders against the militarily superior Mameluks .

End of the crusade and assassination attempt on Edward

After King Hugo I of Jerusalem had concluded a ten-year armistice with the Mamlukes in May 1272, the English crusader army began their return journey. Eduard himself remained in Acre, where he was critically injured in an attack in June 1272. The assassin had apparently been familiar to Eduard, since he had given him a private conversation. During the conversation, the assassin attacked Eduard with a poisoned dagger. Eduard was able to repel the attack and kill the alleged assassin , but he was wounded in the arm. How Eduard survived this injury is reported in various ways. The Grand Master of the Knights Templar is said to have tried in vain to heal the wound with a special stone. The wound probably started to get infected and was eventually treated by an English doctor who cut the affected flesh from the arm. According to a later legend, Edward's wife Eleanor is said to have sucked the poison out of the wound, according to other sources, Edward's close friend Otton de Grandson did so . However, this is not mentioned in any of the contemporary sources which report that the plaintiff Eleanor had to be led out of the room before the operation. On September 24, 1272 Eduard finally started his journey home.

Edward's crusade was marked by overzealousness and an awareness of limited resources. Eduard had appropriately restrained himself militarily, but he had misjudged the cost of the crusade. The available funds only lasted until Edward's arrival in Acre, so that he then had to borrow money from Italian merchants and other donors. The Riccardi merchants from Lucca lent him over £ 22,000 on the return trip alone. The total cost of the crusade was arguably over £ 100,000, making it an extremely expensive adventure with little militarily accomplished. Edward's attempts to get Mongol support against the Mamluks had been unsuccessful and his own military actions had been pinpricks to the Mamluks. However, the joint expedition to the Holy Land had led to close and good contacts between numerous crusaders even after the end of the crusade. Edward himself had won the trust of a number of barons such as John de Vescy , Luke de Tany , Thomas de Clare and Roger de Clifford , who from then on served him faithfully.

Return from the crusade

During the return journey from Acre, Eduard learned in Sicily that his father had died. Instead of quickly returning to England and taking power there, Eduard traveled leisurely through Italy to France. On the way he visited Pope Gregory X , who had also been to Acre before his election as Pope, where Edward had met him. He then traveled on to Savoy, where he visited Count Philip I , an uncle of his mother's. There he also met several English magnates who had traveled to meet their new king, including Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall and the bishops John le Breton , Nicholas of Ely , Godfrey Giffard and Walter of Bronescombe . Eduard was a guest in the new, heavily fortified castle of St-Georges-d'Espéranche , which later served as a model for the castles he built in Wales. On their onward journey, Peter de Châtelbelin , a son of Johann von Chalon , invited the English to a tournament in Chalon-sur-Saône . There was heavy fighting between the English and Burgundians in the Buhurt . Peter de Châtelbelin is said to have grabbed Eduard in the most unknightly manner in the neck to pull him off his horse. Eduard was able to fend off this and reciprocated by ultimately having to surrender to a simple knight, not to him. However, this little Chalons war had no further consequences and the English were able to continue their journey. At the end of July 1273, Eduard reached Paris, where he met the French King Philip III. paid homage to the Duchy of Aquitaine . He then traveled to Gascony, where the French barons paid homage to him as Duke of Aquitaine. When the powerful Baron Gaston de Béarn , who originally also wanted to take part in the crusade, did not appear to pay homage, Eduard led a swift campaign against him and took him prisoner. Eduard did not leave Gascony until late spring 1274. He traveled north through France, crossed the English Channel and reached Dover on August 2, 1274 . This meant that Eduard had only returned to England almost two years after his father's death. Still, this was the first undisputed accession to the throne since the Norman conquest .

The government of Edward I until 1290

Eduard as legislator

When Edward returned to England in 1274, he first took care of the final preparations for his coronation, which took place on August 19, 1274 by Archbishop Robert Kilwardby in Westminster Abbey . There was a dispute with his brother Edmund over his role as Steward of England at the ceremony, so that Edmund probably stayed away from the coronation. There was also a dispute between the Archbishops of Canterbury and York over their primacy, which led to Archbishop Walter Giffard of York being excluded from the ceremony. The actual coronation went as planned and was accompanied by exceptionally splendid celebrations. After the coronation, Eduard appointed his confidante Robert Burnell as the new Chancellor, and he also appointed other new ministers and high-ranking officials. On October 11, 1274, he ordered a survey of the royal lands, which was completed before March 1275. Only a few reports of this collection, the so-called Hundred Rolls , have survived, but they demonstrate the large extent of the collection. The surveyors were able to uncover fewer cases than hoped in which barons had illegally seized royal possessions and rights. Instead, numerous examples of abuse of office by officials and judges were reported, but since this was not the reason for the recording, no judicial commissions were set up to punish these abuses. Because of the enormous volume of feedback, the collection was probably only of limited use. However, the results of the Hundred Rolls were incorporated into the First Statute of Westminster, issued during Parliament in April 1275 . In addition to this statute, Edward passed a number of other statutes and laws as king, including the 1278 Gloucester Statute , 1279 Mortmain , 1283 Acton Burnell , 1285 the Second Statute of Westminster and the Statute of Winchester . 1285 was followed by the Statute of Merchants , 1290 Quia emptores and Quo Warranto . A focus of these laws were rules for land ownership. The first article of the First Statute of Westminster, De donis conditionalibus , dealt with the frequent complaint that the precise rules by which land were given to tenants and vassals were often disregarded. The Quia emptores, issued in 1290, regulated that when a fiefdom was transferred to a new fiefdom, the new owner would also assume the same feudal duties as his predecessor. In addition, the law regulated the rights of tenants and protected them from unjustified attachment of their property. However, the law also strengthened landowners' rights against unruly tenants. Westminster's Second Statute made it easier for landowners to deal with fraudulent bailiffs. The Mortmain Statute was probably the most political law Edward passed. Against the background of his dispute with Archbishop Pecham, the king renewed a regulation in the 1259 Provisions of Westminster , according to which land donations to the church required royal approval. The treatment of debt was the subject of the Acton Burnell Statute , which was supplemented by the Statute of Merchants. These laws enabled merchants to register their debtors. If a debtor fails to repay his debts in time, he faces jail and eventually expropriation. The Second Statute of Westminster dealt with the observance of law and order and renewed the right to own arms. For the cities it was determined who was responsible for guarding and supervising within the walls. It also stipulated that the Hundreds , a subdivision of the counties, were responsible for bringing criminal charges. It was ordered that the streets should be wide and the edges free of undergrowth so that muggers could not hide in them.

These numerous laws show that the king had an intense interest in legislation, and in memory of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian who had the corpus iuris civilis compiled, Edward I was referred to as the English Justinian in the 19th and early 20th centuries . Eduard obviously did not pursue the vision of fundamentally reforming the legal system. Instead, the laws it enacted were intended to complement the complex system of common law where deemed necessary. The extent to which the king himself was involved in the formulation of the laws cannot be understood. Because of his experience with the reform efforts of the barons in the 1250s and 1260s, he certainly had a personal interest in the legislation, but he certainly left the details of the work to the experts of the royal chancellery. The expansion of the royal central administration led to an increasing specialization of the administration. The great central courts, the Court of King's Bench and the Court of Common Pleas were separated from the Curia Regis , the royal council .

Relationship to the Church and to Justice

After John Pecham became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1279, several conflicts arose between the King and the Primate of the Church of England. Pecham announced that same year at a synod in Reading that he wanted to implement church reforms. He also attacked royal officials, who were often given church benefices instead of a salary . In doing so, he challenged the traditional right of the king to grant church benefices. During parliament in the autumn of 1279, the archbishop was therefore forced to limit the scope of his reforms. Nevertheless , Pecham continued to excommunicate royal officials who held several benefices at the same time and thus violated canon law . Pecham's stance was strengthened by a council meeting in Lambeth in 1281 , which decided to carry out further church reforms. In a long letter to the king, Pecham reminded him of his duty as Christian king to protect the Church in England according to the general rules of Christianity. After numerous complaints from the clergy against royal officials had been submitted to Parliament in 1280, further complaints arose in 1285, mainly from clergy from the Diocese of Norwich . The Crown, on the other hand, took the view that in this diocese ecclesiastical courts would illegally interfere in secular matters. However, since the king wanted to travel to France, he instructed the royal judge Richard of Boyland in 1286 to be particularly considerate of the clergy in the Diocese of Norwich.

When the King returned to England in 1289 after an absence of almost three years in France, complaints were made against numerous officials and judges. The king then appointed a commission to collect the complaints. A total of around 1,000 officials and judges were accused of wrongdoing and abuse of office. For example, the Chief Justice of the Common Pleas , Thomas Weyland , was charged with covering two murderers. He then fled to church asylum , from which he later had to surrender. The king forced him to go into exile. Even Ralph de Hengham , the Chief Justice of the King's Bench , offenses were accused. Numerous judges and officials were dismissed, but on the whole the king's verdict against his officials was rather mild and almost only imposed fines. Hengham was also later in the king's favor again.

The conquest of Wales

Starting position

By the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267, Edward recognized the loss of most of his Welsh possessions. As king, however, he had to take care of relations with the Welsh princes again after his return from the crusade in 1274. Llywelyn ap Gruffydd , who had been recognized as Prince of Wales in the Treaty of Montgomery, did not understand how the political situation in England changed after the death of Henry III. had changed. He refused to pay homage to the new king and continued a border war against the Marcher Lords , which is why he began building Dolforwyn Castle . To do this, he stuck to his plan to marry Eleanor , the daughter of the rebel leader Simon de Montfort. His own brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd and Lord Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn rebelled against his supremacy in Wales in 1274 . However, their revolt failed and they had to flee to England. After Llywelyn had repeatedly failed to pay homage to Edward I, war became inevitable.

The campaign from 1276 to 1277

In the autumn of 1276 Edward I decided to wage a campaign against Wales . In the summer of 1277 he raised a feudal army of over 15,000 men with whom he moved from Chester along the coast of North Wales to Deganwy . At the same time, an English fleet landed on the island of Anglesey , where English harvest workers brought in the grain. Threatened by famine and faced with the overwhelming military superiority of the British, Llywelyn had to surrender and make far-reaching concessions in the Aberconwy Treaty . In addition to assignments, part of which Dafydd ap Gruffydd received, Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was to pay a heavy fine of £ 50,000, which was never seriously recovered. Although Edward I ultimately left his rank to the Welsh prince and finally allowed him to marry Eleonor de Montfort, the relationship remained tense. The strict English officials and judges who worked in Wales after the war and aroused the displeasure of the Welsh people contributed to this. There was also a dispute over the affiliation of Arwystli , which was claimed by both Lord Llywelyn and Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn.

The conquest of Wales from 1282 to 1283

Despite the tense situation, the English were surprised when Dafydd ap Gruffydd attacked Hawarden Castle on April 21, 1282 , triggering the signal for a nationwide uprising of the Welsh. Prince Llywelyn quickly took over the leadership of the uprising, which was supposed to drive the English out of much of Wales again. In April Edward I decided then at a Council meeting in Devizes , Wales fully conquer . The main English army was to advance again into North Wales, while smaller armies attacked from Central and South Wales. For his army, the king gathered troops not only from England, but also from Ireland and Gascony. Anglesey was again conquered by an English fleet, and by autumn 1282 Snowdonia , the heart of the kingdom of Lord Llywelyn, was surrounded by English troops. Llywelyn then made an advance with a small force to Mid Wales, where he fell in the battle of Orewin Bridge . Dafydd now took over the leadership of the Welsh, but could do little against the far superior English, who continued their advance in Snowdonia. In April 1283, Castell y Bere was the last Welsh castle to be conquered, and in June the fugitive Dafydd and his last followers were captured. He was taken to Shrewsbury , where he was convicted of traitor and executed.

Building English Rule in Wales

In conquered Wales Edward I now set up an English administration, which was regulated by law in the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284. Almost all the Welsh lords who had supported Lord Llywelyn lost their dominions, some of which Edward distributed among his English magnates . To secure his conquest, Eduard expanded his castle-building program in Wales , in addition he founded a number of boroughs , which are only allowed to be inhabited by the English. In 1287, the Welsh Lord Rhys ap Maredudd rebelled in Wales . As a Welsh lord, he had previously stood on the side of the English and was therefore allowed to retain his rule after the conquest of Wales. However, Rhys ap Maredudd did not feel adequately rewarded by the king for his support, and as he was increasingly harassed by English officials, he began an open rebellion with extensive raids in 1287. Since Rhys had been on the side of the English during the conquest of Wales, he received almost no support from the rest of the Welsh. Edmund of Lancaster could therefore easily put down the rebellion as regent for the king residing in Gascony. In September 1287 Dryslwyn Castle , the headquarters of Rhys ap Maredudd, was captured. Then, at the end of the year, the latter surprisingly captured Newcastle Emlyn , which was then recaptured in January 1288. But again Rhys was able to flee. He was not caught until 1292 and executed as a traitor.

Much more dangerous for English rule was the Welsh uprising, which hit large parts of Wales in 1294 . The high taxes, a strict English administration and massive drafting of troops for the war with France meant that the uprising was supported by numerous Welsh people. The king used his army, which he had gathered in southern England for the war with France, to suppress the uprising. Against this military superiority, the Welsh could do little again, so that the uprising was finally suppressed by the summer of 1295. The King then went on a triumphant tour of Wales, imposing heavy penalties on the Welsh communities. The campaign cost the stately sum of about £ 55,000 and delayed the deployment of English reinforcements to south-west France by a year.

The reform of royal finances from 1275 to 1289

Successful measures to increase income

At the beginning of his reign Edward I found himself in a difficult financial situation. His father had left him with shattered finances, and Edward himself was heavily indebted to foreign bankers at the cost of his crusade. In addition to the income from the royal goods, as king he was able to dispose of the customs income, while taxes had to be approved by the parliaments as required. Therefore, from 1275 onwards, Eduard tried to increase his income through several measures. In April 1275 Parliament passed a duty of six shillings and eight pence on every sack of wool exported. This tax paid in around £ 10,000 annually. Still not enough, Parliament in October 1275 granted a tax on the fifteenth part of the movable property, bringing in over £ 81,000. To do this, the king took measures to improve his financial management. New regulations were enacted for the treasury, and the king appointed three officials to replace the local sheriffs with the administration of the royal property. Of course, this measure met with resistance from the sheriffs and ultimately did not work. That is why it was given up after three years. In contrast, in 1279 the English clergy granted the king a temporary tax on their income. The clergy of the Canterbury ecclesiastical province granted him a tax of the fifteenth for three years and the clergy of the ecclesiastical province of York granted him a tithe for two years in 1280 . Since the silver coins in circulation had lost value through use and pruning , the king decided in early 1279 to reform the coins . To this end, numerous foreign skilled workers were recruited and local mints were set up again. The mints remained in operation until the late 1280s, but by 1281 alone, silver coins worth at least £ 500,000 were re-minted. The coin reform proved to be successful, because although the new coins were slightly lighter than the old coins, they were traded higher in value than the previous ones. Around 1300, however, an increasing number of counterfeit coins were discovered, which probably came from abroad.

Heavy financial burdens from the king's wars

Despite these successes, the king's numerous wars put a considerable strain on the royal finances. No tax was levied on the first campaign against Wales in 1277 because the government did not want to levy a new tax shortly after the tax levied in 1275. The Welsh uprising of 1282 was so unexpected that no parliament could be called to pass a tax. Therefore the campaign was initially financed by loans of £ 16,500 granted to the king by the English cities. However, these loans were nowhere near enough. In January 1283 regional parliaments were convened in York and Northampton, which granted the king a tax on the thirtieth. Further loans came from the Riccardi banking house , and other Italian banks made about £ 20,000 more loans to the king. The problems with the financing of the war flowed into the statute of Rhuddlan 1284. The law provided for a simplification of the treasury's bookkeeping by eliminating the need to constantly re-enter old loans in the pipe rolls . The high debts nevertheless forced the king to send agents to the counties in order to collect more of the king's outstanding debts. The Court of Exchequer should it and not treat only the king's processes and its officials further by nobles. These measures caused displeasure among the nobility and brought in little money.

The expulsion of the Jews from England

Another regular source of income for the king was the taxes of the Jewish population, who in England were directly subordinate to the king. In 1275, the king passed a law that forbade Jewish moneylenders to pay usurious interest. In return, this Statute of Jewry allowed the Jews to operate as traders and merchants and possibly even to lease land. While the Jews had previously had to pay high taxes and had suffered considerable financial losses due to the coin reform, they were spared financially in the 1280s. The Pope had objected to the Statute of Jewry, however, and by 1285 there were increasing complaints that Jews were breaking the law, continuing to lend money, and continuing to charge usurious interest. In addition, anti-Semitism was widespread in England . While Edward's wife, Eleonore, was actively involved in business with Jews and profited considerably from the collection of debts that she had taken on from Jews, Edward's mother, Eleonore of Provence, had declared in 1275 that no Jew was allowed to live on her lands. In addition, Jews were repeatedly accused of alleged ritual murder , as in the case of the youth Hugh of Lincoln, who died in 1255 . After the king had expelled the Jewish population from Gascony in 1287, he had all Jews in England declared arrested on May 2, 1287. The Jewish community was to pay a fine of £ 12,000, but in fact little more than £ 4,000 was raised. Finally, on July 18, 1290, the king ordered the expulsion of the Jews from England. At that time there were about fifteen Jewish communities with about 3,000 members in England. The expulsion of the Jews was generally welcomed by contemporaries, but it proceeded without great difficulty and without pogroms . There were only isolated reports of attacks, because the king had granted the Jews safe conduct to the Cinque Ports. He also made sure that the Jews did not have to pay excessive fees for the crossing. The king took over the Jewish property and also the debts that Christians still owed to Jewish creditors. He was able to sell the houses for around £ 2,000, but with the eviction he closed off a regular source of income. The role of Jewish moneylenders was taken over by Italian bankers such as the Riccardi, who, however, could not fill this role nationwide and did not pay the king any taxes. After the expulsion, Jews were only allowed to live sporadically in England. They were only allowed to resettle again in 1656.

The relationship between the king and his magnates

As with all medieval kings, the power of Edward I depended above all on the support of his magnates . His relationship with some magnates was consistently good, such as Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln , who was an important friend and ally, or the barons such as Roger de Clifford . On the other hand, the king had had a tense relationship with the powerful Gilbert de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester, since the 1260s. Although the king was known for his lack of generosity towards the barons, numerous knights and barons served him faithfully.

Edward's manipulations of inheritance law

Eduard tried to take advantage of family fortunes, although he did not shrink from interpreting inheritance law in his favor. He was evidently reluctant to confirm the succession of existing earldoms, nor did he create new earl dignities. After the death of Aveline , heir to the Count of Aumale in 1274, the king aided a swindler who claimed the title. He bought the alleged rights from him for the annual payment of only £ 100, with which he acquired a considerable inheritance for the crown. He put considerable pressure on Aveline's mother, the widowed Countess of Devon , to sell her extensive holdings to the Crown. But it wasn't until she was on her deathbed in 1293 that royal officials persuaded her to hand over the Isle of Wight and other possessions to the King for £ 6,000 . This practically disinherited the rightful heir Hugh de Courtenay . Another case was the Earl of Gloucester when he married the king's daughter Joan of Acre in 1290 . Before the marriage he had to hand over his possessions to the king and then received them back as a fief together with his wife. His heirs were to be his children from his marriage to Joanna of Acre, while his daughters from his first marriage were in fact disinherited. Edward reached a similar settlement in 1302 when the Earl of Hereford married the king's daughter Elizabeth . In 1302 the Earl of Norfolk was persuaded to hand over his lands to the Crown. He then received it back with the condition that it was strictly inherited by men. Since he was an older man and so far childless, this meant that when he died, his lands would almost inevitably go to the Crown and not to his brother. When Alice de Lacy , daughter of the Earl of Lincoln Thomas of Lancaster , married a nephew of the king in 1294 , the king convinced the earl to hand over most of his possessions to the king and to get them back as a lifelong fief. To this end, an agreement was made that the possessions would go to the Crown and not to the rightful heirs if Alice should die childless. With these agreements, the king unscrupulously circumvented traditional inheritance law on several occasions. However, the acquired lands did not belong to the crown estate , but the king used them to provide members of the royal family with lands.

The quo warranto procedure

The manipulations of inheritance law carried out by the king affected only a few noble families. The review of the jurisdictions he initiated between 1278 and 1290, in which the landowners were supposed to present written evidence, so-called Writs of Quo Warranto ( German with which authority ), affected almost all nobles. The Hundred Roll Inquiry, carried out in 1274, revealed that there was often uncertainty as to whether the local jurisdiction, which many magnates exercised, was actually legitimate or whether royal courts had jurisdiction. Initially, the king wanted parliament to review the claims of the magnates, but before Easter 1278 it became clear that this procedure was too time-consuming and therefore not practical. During the Gloucester Parliament in 1278, a new procedure was therefore adopted. Those claiming jurisdiction should prove their claims before traveling judges. The crown was able to call on magnates directly through a quo warranto to prove their claims. This led to numerous lawsuits, especially with old property claims from the time of the Norman conquest . The Quo Warranto investigation made it clear that exercising local jurisdiction was a privilege granted by the Crown, but no agreement could be reached on what evidence would be generally accepted. Numerous cases were adjourned by the courts, and only in a few cases did the Crown Magnates withdraw their rights from local jurisdiction. This method ultimately also proved to be ineffective. By renouncing the consistent enforcement of its claims, however, the crown probably avoided major conflicts with the magnates. When the king returned to England from his long stay in Gascony in 1289, he dealt with the problems of the procedure. He appointed Gilbert of Thornton , who had been one of the king's most energetic lawyers to date, as chief justice of the king's bench . The latter now took over numerous previously adjourned proceedings, although in numerous cases he did not see centuries of land ownership as a substitute for a missing document that confirmed the right to jurisdiction. This led to furious protests by numerous magnates during Parliament at Easter 1290, whereupon the Statute of Quo Warranto was issued in May . In this law the year 1189 was set as the reference date. Those who did not have a certificate but could prove that their ancestors had owned the lands before 1189 were granted local lower jurisdiction. However, in 1292, Crown Attorneys began again to review barons' legal rights. In view of the impending war with France, in which the king needed the support of his barons, the king finally prohibited further proceedings in 1294.

Edward I's foreign policy until 1290

Through his crusade, Edward I was able to undoubtedly increase his reputation vis-à-vis other European rulers. It was particularly recognized that he had remained in the Holy Land much longer than the other leaders of the crusade of 1270, although the crusade had obviously failed militarily. Despite this failure, Edward I still had the hope of being able to undertake a second crusade to the Holy Land for a long time. In 1287 he made another vow of crusade. His foreign policy towards France, which was willing to compromise, must be seen in this context, because it was clear to him that he could only leave England if the security of his empire, including the possessions in south-west France, was not threatened. However, the conflict between Charles of Anjou and the kings of Aragon over the Kingdom of Sicily prevented a new crusade. Therefore Edward I tried to mediate in the conflict in the 1280s. In 1283 he even offered that in Bordeaux, which belonged to his possessions in France, a duel as a divine judgment between Charles of Anjou and Peter III. of Aragón could take place, but this was never implemented. In 1286, Eduard was finally able to broker an armistice between France and Aragon, which, however, was not kept for long. In 1288 he concluded with Alfons III. of Aragón signed the Treaty of Canfranc and thus brokered the release of Charles II , the son and successor of Charles of Anjou, from Aragonese captivity. Edward I paid a large sum of money and held high-ranking hostages for the release of Charles, but in the end there was no lasting peace between the Anjous and the kings of Aragon. Eduard also planned marriage alliances with Navarra , Aragón and with the German King Rudolf I of Habsburg , but all of them failed for various reasons. The only marriage alliance he could make was with the Duchy of Brabant , whose heir Johann married Edward's daughter Margaret in 1290. Edward I even hoped that the Christian western European empires would ally with the Mongols in order to jointly fight the Islamic empires in the Holy Land. However, this idea was too idealistic, far too ambitious and too extensive for the time. Ultimately, Edward's lively diplomacy and his attempt to pacify the Western European empires in order to induce a new crusade failed in the early 1290s. With the conquest of Acre by the Muslims in 1291 and the conquest of the last remnants of the Kingdom of Jerusalem shortly thereafter, Edward I's dream of a new crusade became obsolete.

The reign of Edward I in Gascony

Even under Edward's father Heinrich III. England had become the main part of the Angevin Empire , while the remaining French possessions became a sub-country. This development continued during Edward's reign. However, Gascony had a special meaning for Edward I, perhaps because he was allowed to rule there independently for the first time, albeit limited, from 1254 to 1255. In the early 1260s he visited Gascony at least twice, maybe even three times, and on his return from the Crusade he first traveled to Gascony, not England. There he had to subjugate the powerful Baron Gaston de Béarn . Gaston's daughter had married Henry of Almain , thereby strengthening his bond with the English kings. With the assassination of Henry of Almain in 1271, however, the marriage alliance had lapsed and Gaston now refused to appear before the court of the English Seneschal of Gascony . When Edward I himself came to Gascony after his crusade in autumn 1273, Gaston refused to pay homage to him. Edward I now proceeded cautiously and strictly according to current law against Gaston in order to give him no justification to turn to the French king as overlord of Gascony. Eventually he was able to subjugate Gaston militarily, but the legal battle continued. In fact, Gaston took advantage of Gascon's position as a French fiefdom and turned to the Parlement in Paris. An agreement was not reached until 1278, and after that Gaston remained an obedient vassal.

During his stay in Gascony in 1274, Edward I had a survey of the feudal duties of the nobility towards the king as Duke of Aquitaine made. This was not yet completed when he traveled on to England, but it illustrates Edward's desire to reorganize and consolidate his rule. The importance he attached to Gascony becomes clear again in 1278 when he sent two of his most important advisors and confidants, Chancellor Robert Burnell and the Savoyard Otton de Grandson to Gascony. There they were supposed to investigate allegations against Seneschal Luke de Tany . Tany was replaced by Jean de Grailly , who came from Savoy . In the autumn of 1286 Eduard traveled again to Gascon himself, where he tried hard to solve problems in the administration of the region. He had the feudal duties in the Agenais examined and granted several new cities, the so-called bastides , a charter . The Jewish population was expelled and land was acquired for the king. In March 1289, shortly before his return to England, Edward I in Condom issued a series of orders for the administration of the duchy. In these the duties and rights of the Seneschal and the Constable of Bordeaux were precisely defined and the salaries of civil servants were regulated. For the individual provinces, the Saintonge , the Périgord , the Limousin , the Quercy and the Agenais, special regulations were issued that took regional interests into account. Due to the position of Gascony as a fiefdom of the French king, Edward's options were limited, so he did not try to adapt the administration of Gascony to the administration of his other countries. But he was determined to improve the conditions and order of Gascon through clear rules.

The government of Edward I from around 1290

Not only did the king mourn the death of his beloved wife Eleanor on November 28, 1290, but Treasurer John Kirkby also died in 1290 . Long-time chancellor Robert Burnell died two years later. As a result, the king had to appoint new members of his government, the character of which changed significantly.

Financial Problems and Controversial Taxes 1290 to 1307

Increasing taxation of the population and the clergy

When Eduard returned to England in August 1289 after almost three years in Gascony, he was faced with new financial problems. For the stay in south-west France he had to take on new debts, so that in April 1290 he first wanted to ask parliament to be able to raise a feudal tax on the occasion of the marriage of his daughter Johanna with the Earl of Gloucester . This fee on the occasion of the marriage of the eldest king's daughter was an old custom, but only relatively low income was expected. Therefore the plan was dropped again. Instead, he called Parliament, including the Knights of the Shire, to Westminster on July 15 to approve a tax on the Fifteenth. In return, he had the Jewish population expelled from England in the same year, which met with broad approval. The tax on the fifteenth brought in a handsome £ 116,000, and the clergy of both ecclesiastical provinces agreed to a tenth of the church's income. This initially gave Edward I sufficient financial leeway, but the costs for the war with France from 1294, for the crushing of the Welsh uprising from 1294 to 1295 and for the war with Scotland from 1296 soon exceeded the income again. To make matters worse, the Riccardi banking house, to which the king owed over £ 392,000, was in fact bankrupt. In order to be able to raise the costs of the wars, the parliaments approved new taxes in 1294, 1295 and 1296, the income of which, however, fell rapidly. When the king asked for a tax on the eighth to be granted in 1297, he met fierce opposition until he was granted a ninth in the autumn. The clergy were even less accommodating. In 1294 the king pressed half of their income from them under threat of ostracism , and in 1295 a tenth. When the king demanded a new tax from the clergy in 1296, Archbishop Robert Winchelsey refused to give his approval at a council in Bury St Edmunds , citing the papal bull Clericis laicos . With this bull, Pope Boniface VIII had forbidden the taxation of the clergy by secular rulers, with the intention of meeting the kings of France and England so that they had to end the war between the two empires. In the face of the resistance, Edward I ostracized the clergy at the beginning of 1297 and collected fines from them in the amount of the taxes he expected.

Introduction of a wool tax and other taxes

In order to cover the further costs of the war, the king planned to confiscate the English wool in 1294 and then sell it abroad at a profit. This led to the protest of the merchants, who feared for their income and instead proposed a duty of 40 shillings per sack, the so-called maltote . This proposal has been implemented. Nevertheless, at Easter 1297 the king again ordered the confiscation of the wool, which, however, only brought little income. In August the king ordered 8,000 more sacks of wool to be confiscated. Due to the strong protests, the king waived further confiscations and higher tariffs in the autumn of 1297. In the last years of his reign Edward I had to forego additional income. In 1301 the tax of a fifteenth and in 1306 the tax of a thirtieth and a twentieth was granted. After negotiation, in 1303 he was able to impose an additional three shillings and four pence duty on every sack of wool exported by foreign merchants. Taxes were levied on the clergy for alleged crusades, the income of which the king shared with the pope. However, this income was not enough for the king's increased expenses, which were mainly caused by the war in Scotland. Therefore, he had to continue to borrow from Italian merchants, especially the Frescobaldi family . Eventually the king could no longer settle his debts, which he owed to numerous creditors. At his death, his debt was approximately £ 200,000.

Development of Parliament under Edward I.

During Edward's reign the parliament developed not only as a council of the crown vassals , but also as a representation of the individual counties. These were called to parliaments as Knights of the Shire . As a rule, these were respected landowners from the equestrian order, who were nevertheless informed about problems on site. In the Magna Carta the kings had to accept that they could not raise taxes without general approval. The increasing financial demands of Edward I meant that the representatives of the counties and not only the crown vassals had to give their consent to new taxes. Although the county representatives were not invited to all parliaments, they managed to ensure that no parliament could pass new taxes to which they had not been invited.

Policy of the king towards the nobility

Politics of Strength towards the Marcher Lords

The king had not had the Quo Warranto investigations carried out in the Welsh Marches, where he needed the support of the Marcher Lords for his wars against the Welsh. However, when there was a conflict between the Earl of Gloucester and the Earl of Hereford in south Wales in early 1290 , the king intervened vigorously in the jurisdiction of the Welsh Marches. The Earl of Hereford accused the Earl of Gloucester that the Morlais Castle he had built was built on Hereford property. However, Hereford did not want to resolve the conflict through negotiations or a feud , as was customary in the Welsh Marches so far, but turned to the king first. But when Gloucester did not stop raiding Hereford properties, the latter carried out retaliatory attacks. The king first heard the complaints in Abergavenny in 1291 before passing his sentence in Westminster in 1292. Both magnates had to submit to the king, who imposed humiliating penalties on them. He confiscated their properties and imposed heavy fines. Although their lands were soon returned to them and they did not have to pay the fines, the king clearly showed that he could assert himself against noble magnates with old rights and privileges. The king also took action against other Marcher Lords, for example against Edmund Mortimer von Wigmore in 1290 , when he arbitrarily sentenced a criminal and had him executed instead of handing him over to the royal judges. For this, the king confiscated Wigmore Castle , which was eventually returned to Mortimer. Also Theobald de Verdon was his rule in the same year Ewyas Lacy withdrawn after he had defied the royal sheriff. However, the property was later returned to him as well. With these actions against the self-confident and militarily influential Marcher Lords, the king demonstrated strength and determination towards his nobility.

The relationship of the king to his English magnates

When a group of magnates, led by the Earl of Arundel , refused to take part in the campaign in Gascony in 1295 because this would not be part of their duties as English vassals, the king tried not to persuade them, but rather intimidated them. He threatened them that the treasury would collect their outstanding debts to the crown, whereupon the magnates gave in. Nevertheless, the chronicler Peter Langtoft noted that Eduard received little support from his magnates during his campaigns, especially in the suppression of the uprising in Wales from 1294 to 1295 and in the campaign to Flanders in 1297. Langtoft led this to the lack of generosity of the king back. However, Eduard promoted some magnates, including his friend Thomas de Clare, to whom he generously gave Thomond in Ireland in 1276 . Otton de Grandson was rewarded for his service with properties in Ireland and the Channel Islands. After the conquest of Wales, the king gave several magnates important holdings in the conquered areas, and after the campaign against Scotland in 1298, the king forgave lands in Carlisle in Scotland. In the years that followed, the king gave away major Scottish possessions before they were conquered. He promised Bothwell to Aymer de Valence in 1301 before the castle was conquered. In this way he gave lands in Scotland to around 50 English barons until 1302.

The crisis of 1297

Revolt of some magnates

The high burdens placed on the population by the wars in Wales, Scotland and against France from 1296 onwards generated great opposition among the subjects. Eduard tried to get support for his politics through the approval of the parliaments. In 1294 a parliament was convened, to which plenipotentiary Knights of the Shire were invited. In 1295, knights and citizens were appointed to a parliament that was later called the Model Parliament . The shape of the invitations later served as a template for further invitations. In the invitations to the representatives of the clergy, the phrase What concerns everyone, everyone should agree to it ( Latin quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur ) was used. Nevertheless, there was increasing resistance to the king's financial demands. During Parliament, which met in Salisbury on February 24, 1297 , Roger Bigod, 5th Earl of Norfolk, vehemently criticized the king's plans for a campaign in Flanders, while he was to be sent to Gascony with other magnates. The legality of military service became a major issue in the emerging crisis. With a new form of convocation of the feudal army, called to London on May 7, 1297, military service was extended to all residents who owned land worth £ 20 or more. When the mustering of the troops appeared, the King asked Bigod as Marshal and Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford as constable , to keep records of the soldiers who had appeared, as if it were a normal case of feudal service. When the earls refused to do so, they were dismissed from their offices. When the king offered the soldiers pay at the end of July, only a few volunteers continued to volunteer. Apart from the knights of the royal household, Eduard found little support for his military plans among the nobility.

Resistance from the Archbishop of Canterbury

In addition to complaints about military service, there were also complaints about high taxes and the confiscation of wool and other goods by royal officials. The government requisitioned food for the army, and the king generously interpreted the traditional right to requisition food for his household. This inevitably led to mismanagement and corruption, which bitter many residents. In July 1297, the Monstraunces (also: Remonstrances ) were published, a letter of complaint in which the king was even suspected of subjugating the population through the high demands. At this point in time, the complaints were directed against the amount of the charges, not against their sometimes illegal collection. However, when the king wanted to levy a tax of the eighth in August and wanted to confiscate wool again, there was a new dispute. The clergy, led by Archbishop Winchelsey, firmly opposed the new tax after the king had threatened to ostracize them and imposed fines equal to the taxes demanded. Nevertheless, the king managed to reconcile with Winchelsey on July 11th. However, on August 20, 1297, the Treasury requested a new tax from the church. At the time, both parties tried to influence public opinion through publications. In a long letter to the archbishop dated August 12th, the king defended his actions. He apologized for the high burdens that were necessary to end the war quickly and successfully. After the end of the war he promised to respond to popular complaints. However, he achieved little with this, so that he had to leave for Flanders with only a small army. With civil war looming, the king's decision to leave England was foolhardy. When the king set out on his campaign on August 22nd, Bigod and Bohun appeared at the Treasury to prevent the collection of the tax of the eighth and the confiscation of the wool.

Confirmation of the Confirmatio cartarum and settlement of the crisis

When the news of the Scottish victory in the Battle of Stirling Bridge reached London a little later, the king's policy received support again. The demands of the king's opponents corresponded almost exactly to the demands published in De tallagio , a series of articles that supplemented the Magna Carta. This required approval for the collection of taxes and for confiscations. The maltote was to be abolished and those who refused to take part in the campaign to Flanders were to be pardoned. In the absence of the king, the Privy Council approved the Confirmatio cartarum on October 10, which was a kind of supplement to the Magna Carta of 1215. It was assured that taxes and duties could only be levied with general consent. Even in the event of war, there were no exceptions. The maltote was abolished. On October 12, a promise was made to convince the king to reinstate the earls in their dignities. The King in Flanders must have been annoyed by the concessions, which went further than he wished, but in view of his weak military situation he had no choice but to confirm the Confirmatio on November 5th and give Bigod, Bohun and their supporters pardon.

Reforms and regaining of authority from 1298

When the king returned from his campaign in Flanders in 1298, he ordered a nationwide investigation into corruption and abuse of office by his officials. These grievances were certainly responsible for the resistance to his policies, but the real cause was the king's insistence on his military plans against all opposition. The relationship with his magnates was strained from then on, and the magnates feared that the king would now withdraw the concessions he had made. The question of examining the boundaries of the royal forests now became a test of whether he still trusted his magnates. It was generally believed that the borders of the royal forests and thus the royal forest sovereignty had been illegally expanded. The statute De finibus levatis , issued in 1299, stated that the examination of the forest boundaries would not allow any curtailment of royal rights. If the forest charter was confirmed again, important rules would be left out. In 1300 the king agreed to the Articuli super Cartas , which restricted royal jurisdiction, the powers of the Treasury and the use of the Privy Seal . The sheriffs should be elected in the counties and the enforcement of the Magna Carta should be sought. However, the king made no concessions in military service, as was also required.

The controversy continued during Parliament in 1301 when Henry of Keighley , a Lancashire Knight of the Shire, tabled a bill harshly criticizing the government. The king had to make concessions on the boundaries of the royal forests, and although he continued to make no concessions on military service, he refrained from new forms of recruitment. The last years of his reign were politically relatively calm, although the problems of the 1290s were not yet resolved. In 1305 he even had the Pope issue a bull that declared his concessions null and void. In 1306 he reversed the change in the forest boundaries from 1301. However, there was no new opposition, and during his last parliament in Carlisle in January 1307 the main arguments were about the implementation of a papal tax and other demands of the Pope. However, there were other domestic political problems at the time. In Durham , Bishop Antony Bek , the king's old friend, and the monks of the cathedral priory found themselves in a heated dispute, after which the diocese was placed under royal administration twice. The king got into a heated argument with Thomas of Corbridge , Archbishop of York, when he wanted to fill a benefice with a royal official. The archbishop protested against it, whereupon the king personally rebuked him so severely that he suffered a shock and died a little later, in September 1304.

Edward I's foreign policy from 1290

The war with France

causes

In 1294 war broke out with France. This war came as a surprise to Edward I, because his relationship with the French kings had so far been good. In 1279 he had visited Paris, where Queen Eleanor was able to pay homage to the French king for the Ponthieu inherited from her . In Amiens, an agreement was concluded which settled issues that were still open, especially over the Agenais. When the French King Philip III. Edward I, as Duke of Aquitaine, requested feudal military service in the Aragonese Crusade in 1285 , Edward's position became problematic. Since the campaign ultimately did not take place and the French king died a little later, Edward's failure to appear was without consequences. In 1286, Eduard paid homage to the new King Philip IV in Paris, so that good relations were restored. The French king saw Eduard as Duke of Aquitaine but as an overpowering vassal who did not recognize French rule and jurisdiction. When there were conflicts between seafarers from France and Gascony in 1293, Eduard was supposed to answer before the parliament in Paris. He sent his brother Edmund of Lancaster to Paris, who was to reach an agreement there. According to a secret agreement made in 1294, Eduard Margarethe , a sister of the French king, was to marry. Almost all of Gascony, including the castles and towns, was to be handed over to the French, but returned a little later. For this, Edward's summons before the parliament should be revoked. However, the English negotiators were betrayed. The English kept to the agreements they had made, but the French did not revoke the summons before Parliament, and when Edward refused to appear, Philip IV declared the fief of Gascony forfeited.

Course of war

In October 1294 a first small English army broke into Gascony. They could occupy Bayonne , but not Bordeaux. Eduard did not only want to wage the war in southwest France, but allied himself with the Roman-German King Adolf von Nassau and numerous West German princes in order to be able to attack France from the Netherlands. However, the uprising in Wales and the beginning of the Scottish War of Independence prevented Edward from quickly leading an army into the Netherlands, and without his military support his allies would not start the fight. After Eduard had subjugated the Scottish King John Balliol in 1296 , his negotiators succeeded in including the Count of Flanders in the anti-French alliance, and Eduard prepared the campaign for 1297. The French king responded to this threat. In a swift campaign he occupied almost all of Flanders, and when Edward I landed there in August 1297, the war was almost militarily decided. In view of the long lack of military support from the English king, most of his allies had hesitated to take to the field against the French king, and with his rather small army alone the English king could not hope to defeat the French army. Since the war in Gascony was also militarily undecided, England and France signed an armistice on October 9, 1297, in which the Count of Flanders was included. Eduard was only able to leave Flanders again in March 1298, after he had paid part of the promised aid money to his allies and after the first revolt of the citizens had broken out in Ghent . Eduard married Margarethe of France in 1299, but it was not until 1303 that the Treaty of Paris was concluded, which restored the prewar status in Gascony. For both France and England the war was an expensive failure. For Edward I the fighting in Gascony alone had cost £ 360,000, the failed campaign to Flanders cost over £ 50,000. Eduard had promised his allies about £ 250,000, of which about £ 165,000 was also paid.

The attempt to conquer Scotland

The great cause

Probably in the autumn of 1266 Edward I first visited Scotland when he visited his sister Margaret in Haddington . To his brother-in-law King Alexander III. Edward had a good relationship with Scotland, and Alexander's homage, which Alexander had to pay for his English possessions in 1278, went smoothly. When Alexander III. however, in 1286 died with no surviving male descendants, Eduard tried to take advantage of this opportunity. In 1290 he achieved that Alexander's heiress and young granddaughter Margaret of Norway should be married to his own son and heir Edward . Although it was agreed in the Treaty of Northampton that Scotland should remain an independent kingdom, Eduard apparently wanted to take over actual rule in Scotland after the treaty was concluded. This plan failed in the autumn of 1290 when Margaret died while crossing from Norway to Scotland. Thereupon, in addition to Robert de Brus and John Balliol , a total of eleven other candidates as descendants of Scottish kings raised claims to the Scottish throne. Eduard now claimed as feudal overlord of Scotland to clarify the succession to the throne. The Scottish magnates were initially unwilling to accept this, but through negotiations in May and June 1291 in Norham , Eduard reached the agreement that he was entitled to do so. In November 1292 it was finally determined that John Balliol had the most justifiable claims to the Scottish throne, so that he was crowned king.

Right to sovereignty over Scotland

After this solution to the Great Cause, Eduard made various attempts to assert his claim to suzerainty over Scotland. Finally, on Michaelmas 1293, he called the Scottish King John Balliol because of a dispute with Macduff , a younger son of the 6th Earl of Fife , before the English Parliament, which was to rule the case as a court of appeal . If the Scottish king had appeared, he would have recognized English suzerainty. Balliol, however, only sent the Abbot of Arbroath Abbey as a representative. In 1294 Eduard demanded feudal military service from the Scottish king and eighteen other Scottish magnates in vain in the war against France, which the latter failed to perform. Above all, John Balliol turned out to be a weak king, so that in 1295 a twelve-person council of state effectively took over the government of Scotland. The French, with whom England had been at war since 1294, now tried to form an anti-England alliance with Scotland, which was finally concluded in early 1296 . Thereupon Eduard took the quarrel with Macduff and the refusal of the Scottish king to answer himself in English courts as an occasion to invade Scotland militarily.

The conquest of Scotland in 1296

The campaign of 1296 was a triumphant advance for the English king. At the end of March 1296 he occupied the border town of Berwick . A Scottish army was defeated in the Battle of Dunbar , after which the English hardly encountered any military resistance. After 21 weeks, Scotland was apparently conquered and John Balliol was deposed as king under disgraceful circumstances. Then Eduard had the Scottish coronation stone brought from Scone to Westminster and handed over the administration of the conquered land to English officials. As early as 1297, however, there was a widespread Scottish rebellion, whose leader was Robert Bruce , a grandson of one of the earlier heirs to the throne. Among the most successful opponents of the English, however, were William Wallace , who came from a knightly family, and the noble Andrew Moray . The uprising was in fact a popular uprising against the English, and in September 1297 an English army under Earl Warenne was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge .