Friedrich Wilhelm (Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel)

Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig , also called the Black Duke (born October 9, 1771 in Braunschweig ; † June 16, 1815 in the Battle of Quatre-Bras , Kingdom of the United Netherlands ), was one of the German folk heroes of the Napoleonic Wars , Prussian general, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and Prince in the Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel region . By inheritance he was also from 1805 as Duke of Oels a mediatized prince in the Prussian state.

Life

Friedrich Wilhelm was born as the sixth child of the Duke of Brunswick and Prussian Field Marshal Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand of Brunswick and his wife Augusta of Hanover , Princess of Great Britain. In 1789 he joined the Prussian army , became captain of an infantry regiment and from 1792 took part in the First Coalition War against France. In 1800 he was regimental commander of the Old Prussian Infantry Regiment No. 12 . The high point of his military career was his appointment as major general by King Friedrich Wilhelm III. in July 1801. He was a member of the Military Society . While his father was fatally wounded on October 14, 1806 in the Battle of Auerstedt , Friedrich Wilhelm was in the corps of Duke Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar near Ilmenau . It joined the withdrawal of the defeated army under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher . His dying father called him to Braunschweig to appoint him heir to the throne in the Principality of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , as his three older brothers were unable to rule. A little later, on November 6, 1806, Friedrich Wilhelm took part in the Blücher corps in the battle of Lübeck . Since then, the relationship with Blücher, who attributed his defeat to tactical mistakes by Friedrich Wilhelm, was clouded. Both fell into French captivity through the surrender of Ratekau .

Friedrich Wilhelm could not take up the government in the principality because Napoleon had declared it extinct and in the Peace of Tilsit in 1807 allocated its territory to the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia under the reign of his brother Jérôme . Friedrich Wilhelm retired to Prussia in Oels in Lower Silesia , which he inherited in 1805.

As a result, Friedrich Wilhelm took part in uprising plans against Napoleon's rule and maintained contacts with Ferdinand von Schill and Wilhelm von Dörnberg . When Austria was heading for a war against France in the form of a German popular uprising in 1809, he went to Vienna in January 1809. In February 1809 the Vienna Convention came about between Austria and him, which regulated the task, strength, uniformity, standard, minimum number and salary of a Duke Braunschweig Corps in the Fifth Coalition War, which was now beginning . The Freikorps was under the protection of Austria, but remained independent, was set up and maintained at the Duke's expense. It was to be used against France.

Placing debts on the principalities of Oels and Bernstadt , he managed to finance this new force. In Bohemia , near the Prussian border, at the Náchod Castle , which the Duchess Wilhelmine von Sagan made available to him, and in Braunau , Friedrich Wilhelm formed the 2300-strong " Black Band " until April 1, 1809 .

The “Black Squad” and the Braunschweigische Leibbataillon

The corps, known as the “Schwarze Schar” because of its black uniform, invaded Saxony , acting independently, but was unable to trigger the desired popular uprising, despite the goodwill of the residents. Friedrich Wilhelm, who regarded himself as a warring sovereign, did not want to accept the Znojmo armistice of July 1809, in which Austria recognized its defeat. While the Austrians under Karl Friedrich finally returned to Bohemia, his corps, without their knowledge, moved from Zwickau, fighting with the battle cry "Victory or Death", via Halle , Halberstadt , Braunschweig , Burgdorf , Hanover , Delmenhorst and Elsfleth to Brake , where they embarked succeeded to the British Isle of Wight . In particular, the storming of Halberstadt on July 29, 1809 and the battle at Ölper at the gates of Braunschweig on August 1, 1809, in which the black crowd under Friedrich Wilhelm asserted themselves against a three-fold superiority, were celebrated in poems and songs by the German public .

Great Britain took the “Black Company” in pay and deployed them in the Iberian theater of war . According to an agreement with the British government, Friedrich Wilhelm lost command of his corps and, as the brother of Caroline von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel , the Princess of Wales, and with a stately pension from the British Parliament , chose London as his seat where he was in Brunswick House resided. From there he maintained contact with the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III through the secret envoy August Neidhardt von Gneisenau .

During the Wars of Liberation , Friedrich Wilhelm returned to Braunschweig on December 22, 1813, after the French rulers had been driven out of the city, and took over the government as sovereign to the cheers of the residents. Soon afterwards he went into the field against Napoleon, who had returned from the island of Elba, with the newly formed Braunschweigian Life Battalion , now a fully valid sovereign and ally of the British in the function of a division general under the Duke of Wellington .

Death on the battlefield

The later master carpenter Ernst Carl Külbel was previously a corporal in the 2nd company of the Braunschweigischen Body Battalion and participant in the battle of Quatre-Bras. Due to a legal dispute in the late 1850s about the circumstances of the death of the Duke of Brunswick, Külbel published The Last Moments of our Most Serene Duke Friedrich Wilhelm bei Quatrebras on June 16, 1815 in 1859 . In it he described in detail the course of events. Accordingly, the following should have happened:

At over 30 ° C, the Braunschweig body battalion arrived on the battlefield around 4 p.m. and was immediately involved in heavy, loss-making battles. The 1st platoon of the Braunschweig had formed a screech line that was under constant fire. Artillery fire forced some units to move to an earlier position around 7:30 p.m., which was also the location of the Hanoverian formations at that time. Both units had already suffered heavy losses and were now repeatedly attacked by French cavalry. The Brunswick line infantry had formed a square in order to be able to repel the cavalry attack better than the French attacked. At that moment, Duke Friedrich Wilhelm rode unaccompanied and without cover directly between the Brunswick and the French, where he was hit by the fatal bullet at the Gémioncourt homestead. The bullet first brushed his right wrist and then entered the lower right side of the chest. It penetrated the liver, injured the diaphragm, eventually went through the lungs and exited on the left side of the shoulder. The victim fell from his horse and remained about 25 meters from the Braunschweig group while the French cavalry charged. Since the body battalion changed position in this phase under enemy influence, the event went largely unnoticed. Corporal Külbel was one of the few who had noticed. He then took the hunter Reckau and the horn player Aue (r) to rescue the wounded and not to leave him to the French. The Duke was still conscious when he was brought behind the German lines and was initially put down in the open. Due to increasing artillery fire, he was finally brought to a building on a nearby farm, where he died shortly afterwards in the presence of medical officer August Pockels .

The day after his death, the body was first brought to Antwerp , where the Belgian painter Mathieu Ignace van Brée made an oil painting showing the Duke with a bare chest on the death bed . The right hand injured by the bullet and the bullet hole are clearly visible. The portrait is now in the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum. The body was then placed in a lead-lined coffin. This was filled with alcohol and finally tin-plated so that it could be transferred to Braunschweig, where it arrived at midnight on June 22nd.

Funeral ceremonies

The body was laid out in the city for a few days before the Black Duke was buried in the crypt of the Brunswick Cathedral on the night of July 3rd to 4th, 1815 . The hearse, drawn by eight horses, was followed by Karl II , eldest son and successor of Friedrich Wilhelm as Duke of Braunschweig, the Duke of Cambridge , Friedrich Wilhelm's second son Wilhelm and his uncle Duke Ernst August , who in turn were followed by the rest of the court . The coffin covered with black velvet is still in the crypt today.

Marriage and offspring

Friedrich-Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel-Oels married Marie von Baden, who was eleven years his junior on November 1, 1802 in Karlsruhe .

He had three children with her:

- Charles II of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Wolfenbüttel (1804–1873), Duke of Braunschweig

- Wilhelm August Ludwig Maximilian (1806–1884), last Duke of Braunschweig from the "New House of Braunschweig"

- a stillborn daughter in April 1808

Shortly after the daughter's stillbirth , his wife died at the age of 25 on April 20, 1808 in Bruchsal .

Afterlife

Glorification of person and death

Even before his death on the battlefield, Friedrich-Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel-Oels was celebrated by the population as a “ hero ” and became a living legend . This was largely due to his campaign through northern Germany with the storming of Halberstadt on July 29, 1809, the battle at Ölper on August 1, 1809 and finally the embarkation for England in Elsfleth and Brake on the Lower Weser on August 6 and 7, 1809 .

His violent end in a battle, at the comparatively young age of 43, corresponded to the zeitgeist and was immediately stylized as a “ heroic death ” in order to make him completely immortal . In the following years and decades it became part of the collective memory and went down in " patriotic memory ". Over the years published numerous literary works (biographies, novels, poems, plays) that his life and death glorified in which it mythical - mystical excessive was. Friedrich Wilhelm was celebrated as a freedom fighter and liberator, and his name was mentioned in the same breath as Ferdinand von Schill , Andreas Hofer and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher . A number of monuments, paintings, sculptures and the like were created. Friedrich Wilhelm was also depicted on everyday objects such as plates or cups. For a few years even the black of the uniform of the black crowd was fashionable, people dressed “à la Brunsvic” - the Brunswick style - and thereby expressed their sympathy with those who resisted during the French period in Brunswick . For example, a black christening gown from 1809, which was modeled on the Braunschweig hussar uniform , is still in the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum . This type of “ hero worship ” lasted until the 1940s, at last once again enforced by the National Socialists , who instrumentalized the “Black Duke” as Germany's liberator from French rule.

Various circumstances contributed to the transfiguration of the death of the Duke of Brunswick. So was the Duke z. B. only a few hours earlier and unaware of the upcoming battle in Brussels at the Duchess of Richmond's ball . The British historian Elizabeth Pakenham described the ball as "the most famous ball in history" ("the most famous ball in history"). It served Wellington as a kind of command center, so the proportion of women among the 224 present was correspondingly low at 25%. This major social event owes its historical importance on the one hand to the immediate proximity to the battles of Quatre-Bras and Waterloo and on the other hand, above all, to the large number of famous people present: Almost all of the high officers of Arthur Wellesley's army, which was drawn together against Napoleon, were present: Next to him, Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel-Oels, Thomas Picton , Prince Wilhelm of Oranien-Nassau , Miguel Ricardo de Álava and Edward Somerset . The Duke of Brunswick fell the next day, General Picton three days later in the battle of Waterloo.

The ball and its participants were depicted by various artists in the 19th century. B. by the British painters William Heath ( Intelligence of the Battle of Ligny , from 1818), John Everett Millais ( The Black Brunswicker , from 1860), Henry Nelson O'Neil ( Before Waterloo , from 1868) and Robert Alexander Hillingford ( The Duchess of Richmond's Ball , from the 1870s).

In the United Kingdom , too , the death of the Black Duke was received with consternation, not least because of the very close ties that existed through the ruling Welfenhaus , the personal union between Great Britain and Hanover , which lasted from 1714 to 1837, and the Duchy of Braunschweig-Lüneburg . In addition, Braunschweig troop units had fought alongside or as part of British units on various theaters of war against Napoleon since 1809. B. in the Napoleonic Wars on the Iberian Peninsula , but also decades before as a Brunswick hunter on the British side under General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel during the Saratoga campaign in the American War of Independence .

Commemorations

On "round" memorial days of the battle of Quatre-Bras and the death of the Duke of Brunswick, memorial events were organized by veterans or "patriotic associations", who practiced an almost cultic veneration. In 1840, on the 25th anniversary of the battle, Friedrich Karl von Vechelde published his Braunschweigisches Gedenkbuch for the twenty-five year anniversary of the battles of Quatrebras and Waterloo. On the 50th anniversary of the bivouac before the battle at Ölper in 1859, the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Eiche was consecrated. In 1890, on the 75th anniversary of the battle, there was a special exhibition in Braunschweig entitled "Patriotic memories". In this context, the population was called upon to collect memorabilia from the Wars of Liberation . The "Vaterländisches Museum" in Braunschweig, from which today's Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum emerged, arose from the resulting collection of around 1,000 individual items . In the same year, a memorial for him and the Braunschweig troops was erected in Belgium not far from the place where the duke fell. In 1915, in the middle of World War I , the centenary of the battle took place on June 16 in Braunschweig. In memory of the participants in the battles of Quatre-Bras and Waterloo, the engraver Johann Carl Häseler created a commemorative coin, the "Waterloo Medal", in silver and bronze. On the obverse the Duke is depicted in profile in uniform. The very similar Braunschweig Waterloo Medal had already been awarded in 1818 . The last event of this kind, the 125th Memorial Day, took place in 1940, in the middle of World War II . He turned out much more modest. Only a wreath was laid on the coffin in the cathedral.

Streets and squares

As a result of the victorious Napoleonic wars and the resulting growing national feeling, in Braunschweig, as in numerous other German cities, streets and squares were named after battles and soldiers of the time. In Braunschweig, it was Friedrich-Wilhelm-Strasse, named after the Black Duke, and the adjoining Friedrich-Wilhelm-Platz . Furthermore, streets and squares were named after members of the Brunswick troop units, namely after Georg Ludwig Korfes , Johann Elias Olfermann and Friedrich Ludwig von Wachholtz , after the Brunswick Hussars and after Waterloo. Marienstraße was named after Marie von Baden , Friedrich Wilhelm, who died in childbirth in 1808 , as was the Brunswick Marienstift . Olfermann, who took command of the Brunswick units in the battle of Waterloo after the death of Friedrich Wilhelm , holds a special position in that not only a street and a square in the eastern ring area were named after him, but also a monument to him in 1832 the nearby Nussberg was built. In 1955 a passage between Friedrich-Wilhelm-Strasse and Bankplatz was christened "Friedrich-Wilhelm-Passage".

As in Braunschweig, streets and squares were named after events and people from the period between 1806 and 1815 in various places in the then Duchy of Braunschweig .

Artistic processing

Monuments and memorial stones

In addition to the Olfermann memorial from 1832 , the Schill memorial was erected in 1837 at today's intersection of Schillstrasse / Leonhardplatz for Ferdinand von Schill and 14 of his soldiers, who were shot at this point by French troops in 1809 .

Monuments and memorial stones were erected over a period of many decades.

- 1823: Obelisk on the Löwenwall for Friedrich Wilhelm and his father Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand on Monumentplatz, today Löwenwall

- 1832: Memorial for Johann Elias Olfermann on the Nussberg

- 1843: Obelisk in Ölper in memory of the battle near Ölper on August 1, 1809

- 1859: Monument in Burgdorf near Hanover

- 1859: Memorial in Elsfleth to commemorate the embarkation for England

- 1863: Memorial stone with plaque in Syke to commemorate the embarkation for England

- 1865: Inauguration of the edging of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Oak on the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Quatre-Bras

- 1874: Inauguration of the equestrian statue in front of the Brunswick Palace (together with that of his father Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand)

- 1890: Monument in Genappe, Belgium

- 1909: Memorial stone with plaque in Hesse am Fallstein

- 1910: Memorial stone with plaque in Schöppenstedt

Paintings, engravings etc.

Duke Friedrich Wilhelm had already been the subject of artistic representations during his lifetime; so painted z. B. Johann Christian August Schwartz 1809 one of the most famous portraits of the Duke and Eberhard Siegfried Henne made some well-known engravings, the subject of which was the battle at Ölper . After Friedrich Wilhelm's “heroic death”, many other works of art were created, such as paintings, engravings, etchings, sculptures, etc. In particular, the death of the duke and the last moments of his life were represented - often idealized.

Works come from, among others:

- Mathieu Ignace van Brée : Duke Friedrich Wilhelm on his death bed from June 1815

- William Heath : The Battle of Quatre-Bras, 16th. June 1815. HRH The Duke of Brunswick commanding the avant-garde under the Duke of Wellington.

- Franz Joseph Manskirch : The death of the Duke of Braunschweig

- Johann Friedrich Matthäi : Death of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm around 1836

- Dietrich Monten : The death of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig at Quatrebras , after 1837

There are also a number of everyday objects or decorative objects on which the duke is depicted; so exist z. B. from the Stobwasserschen lacquerware manufacture snuff boxes or trays with his portrait or scenes from his life.

Literature on Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig from 1815 (selection)

Numerous literary works were created during the Duke's lifetime. Immediately after his death, a multitude of other works appeared, some of which portrayed his life and death in an idealized manner.

Biographies, obituaries and the like

In chronological order appeared in Germany among others:

- Hoffmann von Fallersleben : Elegy on the death of the Duke of Braunschweig. Meyer, Braunschweig 1815.

- Jacob Ludwig Römer : Duke Friedrich Wilhelm as a person in faithful trains from his painting. Published by Friedrich Vieweg , Braunschweig 1815.

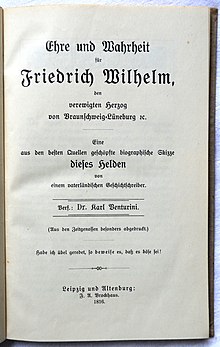

- Karl Venturini : Honor and Truth for Friedrich Wilhelm, the immortalized Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg. A biographical sketch of this hero drawn from the best sources. FA Brockhaus , Leipzig and Altenburg 1816.

- Friedrich Ludwig von Wachholtz : History of the Herzoglich-Braunschweigischen army corps in the campaign of the allied powers against Napoleon Bonaparte in the year 1815. By an officer of the general staff. Vieweg, Braunschweig 1816.

- Heinrich Conrad Stäffe: Punctual description of the incidents between Sr. Herzogl. Your Highness, the Duke of Braunschweig-Oels ... , Braunschweig 1824.

- Friedrich Karl von Vechelde : Braunschweigisches Gedenkbuch for the twenty-five year celebration of the battles of Quatrebras and Waterloo. Friedrich Otto, Braunschweig 1840.

- Wilhelm Müller (Ed.): Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg and Oels in songs of the Germans. Friedrich Otto, Braunschweig 1843.

- Wilhelm Görges : Friedrich-Wilhelm's album. Memorial sheets dedicated to the memory of the immortalized Duke. Meyer brothers, Braunschweig 1847.

- Franz Joseph Adolph Schneidawind : The last campaign and the heroic death of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Braunschweig-Lüneburg in 1815. Darmstadt 1852.

- Ernst Carl Külbel : The last moments of our most noble Duke Friedrich Wilhelm near Quatrebras, June 16, 1815. Schweiger & Pick, Celle 1859.

- NN: In memory of Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig and his procession from the borders (sic!) Of Bohemia to Elsfleth 1809. Oldenburg 1859.

- Citizens' Association : Celebration of the death of the hero Duke Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig who fell for the German fatherland 50 years ago at Quatrebras. Sievers, Braunschweig 1865.

- C. Matthias: The campaign of Waterloo and the Brunswick under Duke Friedrich Wilhelm. A contribution to the fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1815. Friedrich Wagner's Hofbuchhandlung, Braunschweig 1865.

- Bruno Bauer : Duke Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig († June 16, 1815) in its historical significance. A contribution to the 75th anniversary celebration of June 16 and 18, 1815. Arnold Weichelt, Hanover 1890.

- Hermann Tiemann: The black duke. A story from Germany's hardest time. Told to the German people and especially to the German youth. In: From the Sachsenlande. Patriotic Tales VII. A. Appelhans and Pfenningstorff, Braunschweig 1894.

- Paul Zimmermann : Friedrich Wilhelm Herzog zu Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels in voices of his contemporaries Dr. K. Venturini, EC Külbel and Heinr. Conr. Stäffe. In: From the time of severe need. IV., Verlag von Wilhelm Scholz , Braunschweig 1907 (summary and new edition of the works from 1816, 1824 and 1859).

- Christopher Schulze: The Black Duke: Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Oels. A biography. Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg 2014.

Poems

In addition to Hoffmann von Fallersleben, other authors such as B. August Geitel poems on the subject of the Duke. This is how the English writer Lord Byron wrote in Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, which he completed in 1818 :

Within a window'd niche of that high hall

Sate Brunswick's fated chieftain; he did hear

That sound the first amidst the festival,

And caught its tone with Death's prophetic ear;

And when they smiled because he deem'd it near,

His heart more truly knew that peal too well

Which stretch'd his father on a bloody bier,

And roused the vengeance blood alone could quell:

He rush'd into the field, and , foremost fighting, fell.

In the hall, in a bay window,

Braunschweig's condemned prince looks ! At first,

searching for

the premonition of death, he discovered the sound of Thunder, which frightened the cheering;

Whether one teased him because he thought he was close,

his heart was too familiar with the sound

That stretched his father on the stretcher.

Burned with a

thirst for revenge , which blood only quenches. He rushes ahead into the field, fought until death he found!

Novels

The last works of this kind of “hero worship”, including numerous novels and books for young people , appeared during the National Socialist era when attempts were made to reinterpret the “heroic deeds” of the Duke of Brunswick in the sense of Nazi ideology as a fight against an external enemy.

For example:

- Johannes von Kunowski: rider to the north. Novel about Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig, the "Black Duke". Munz, Berlin, undated (approx. 1930/40).

- Sebastian Losch: Brave summer 1809. Report on the fate of Major Ferdinand von Schill and the daring march of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm of Braunschweig from Bohemia to the North Sea. Voggenreiter, Berlin 1935.

- Wolf Oeringk: The black duke. A historical tale from 1806–1815. Leipzig 1938.

- Hansgeorg Trurnit: Frisians and the black crowd. Kolk, Berlin 1936.

- Georg von der Vring : Black hunter Johanna. Ullstein, Berlin 1934 (was filmed in the same year).

Movies

The life of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm was also the subject of feature films:

- 1932: The black hussar , with Bernhard Goetzke as "Black Duke"

- 1934: Black hunter Johanna , with Marianne Hoppe in the leading role, Paul Bildt as "Black Duke" and Paul Hartmann as Georg Ludwig Korfes

Other honor

The Prussian infantry regiment "Duke Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig" (East Frisian) No. 78 was named in his honor.

Restoration of the coffin

On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the Duke's death, his coffin was restored . The oak coffin weighs approx. 500 kg and is covered on all sides with a textile covering made of velvet and silk . Circumferential textile braids woven from fine silver threads are attached to it . There are lettering on the four inclined sides. "Bürgerfürst" is written on the top, "Frühverklärter" on one of the long sides, and the lettering on the other long side is missing. The two initials “FW” for “Friedrich Wilhelm” can be read at the foot end . A woven cross can be seen on the lid of the coffin, on which there was originally a metal crucifix that has been lost; only the leaf-shaped holder is still there. The wooden coffin in turn contains a lead coffin, in which the body has been since July 1815.

Metal and wood restorers as well as employees of the parament workshop of the von Veltheim Foundation were involved in the restoration . The textile covering was cleaned and loose textile fragments were reattached, metal and wooden elements were cleaned and preserved . The total cost of the restoration work amounted to 42,000 euros and was partly raised by private donors, including the “Herzoglich Braunschweigische Feldkorps” (a re-enactment group), the Braunschweig Cathedral Foundation and the majority by the Richard Borek Foundation .

Exhibition on the 200th anniversary of death in 2015

Between May 1 and October 18, 2015, the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum showed the exhibition When is a hero a hero? The Black Duke 1815/2015. which commemorates the Duke's death and the battles of Quatre-Bras and Waterloo. Accompanying events took place in parallel.

Pedigree

literature

- Gerd Biegel (Ed.): On the way to Waterloo. The Black Duke. For Braunschweig against Napoleon. MatrixMedia Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-932313-86-8 .

- Robert F. Multhoff: Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , p. 502 ( digitized version ).

- Kurt von Priesdorff : Soldier leadership . Volume 3, Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt Hamburg, undated [Hamburg], undated [1937], DNB 367632780 , pp. 116-122, no. 1025.

- Eik FF Reher: Elsfleth and the Black Duke. To commemorate August 6th and 7th, 1809, the end of the march of the "black crowd" across Germany in Elsfleth. Isensee Verlag, Oldenburg 1999.

- Eberhard Rohse : Tears of the Fatherland 1815. Hoffmann's "Elegy on the death of the Duke of Braunschweig". In: Marek Halub, Kurt GP Schuster (Hrsg.): Hoffmann von Fallersleben. International Symposium Wrocław / Breslau 2003 (= Braunschweig Contributions to German Language and Literature. Volume 8). Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2005, ISBN 3-89534-538-5 , pp. 85-131.

- Gerhard Schildt : Braunschweig-Lüneburg (-Oels), Friedrich-Wilhelm Duke of. In: Horst-Rüdiger Jarck , Günter Scheel (ed.): Braunschweigisches Biographisches Lexikon - 19th and 20th centuries . Hahnsche Buchhandlung, Hannover 1996, ISBN 3-7752-5838-8 , p. 92 .

- Christopher Schulze: The Black Duke: Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Oels. A biography. Diplomica Verlag, Hamburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-95850-513-1 .

- Louis Ferdinand Spehr : Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels. Gebr. Meyer, 1848, ( books.google.de ).

- Ferdinand Spehr: Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, pp. 508-514.

- Paul Zimmermann : The Black Duke - Friedrich Wilhelm of Braunschweig. August Lax, Hildesheim 1936 ( digisrv-1.biblio.etc.tu-bs.de ).

Web links

- Lyrics of the black hussars on ingeb.org

- Historical representation group of the Herzoglich Braunschweigisches Feldkorps on braunschweiger-feldkorps.de

- Literature about Friedrich Wilhelm in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Friedrich Wilhelm in the German Digital Library

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Ruthard von Frankenberg: In the Black Corps to Waterloo. Memoirs of Major Erdmann von Frankenberg. edition von frankenberg, Hamburg 2015. pp. 28–31 / 21, 55/152, 166.

- ↑ Otto Elster : The historical black costume of the Brunswick troops. Zuckschwerdt & Co., Leipzig 1896, p. 29.

- ↑ Ernst Carl Külbel : The last moments of our most noble Duke Friedrich Wilhelm at Quatrebras, June 16, 1815. Celle 1859, p. 4.

- ^ Ernst Carl Külbel: The last moments of our most noble Duke Friedrich Wilhelm at Quatrebras, June 16, 1815. P. 7.

- ↑ paintings Mathieu Ignaces van Brée

- ^ Louis Ferdinand Spehr: Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels. P. 217.

- ↑ Friedrich Görges : The Sanct Blasius Cathedral in Braunschweig, built by Heinrich the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, and its curiosities, as well as the hereditary burials of the House of Braunschweig-Lüneburg in Braunschweig and Wolfenbüttel. 3rd edition, Eduard Leibrock, Braunschweig 1834, p. 67.

- ↑ Gustav von Kortzfleisch : The Duke Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig train through Northern Germany in 1809. ES Mittler und Sohn, Berlin 1894. ( digisrv-1.biblio.etc.tu-bs.de ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) PDF).

- ^ Louis Ferdinand Spehr: Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels. Pp. 112-134.

- ↑ Willi Müller: The battle at Ölper on August 1, 1809. In: Lower Saxony Yearbook for State History 1, 1924, pp. 156–197. ( historical-kommission.niedersachsen.de ( Memento from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- ^ Eik FF Reher: Elsfleth and the Black Duke. To commemorate August 6th and 7th, 1809, the end of the march of the “black crowd” across Germany in Elsfleth. Oldenburg 1999.

- ↑ Ulrike Strauss: The "French Time" (1806-1815). In: Horst-Rüdiger Jarck , Gerhard Schildt (ed.): The Braunschweigische Landesgeschichte. A region looking back over the millennia . 2nd Edition. Appelhans Verlag, Braunschweig 2001, ISBN 3-930292-28-9 , pp. 707 .

- ↑ Max Hastings (Ed.): The Oxford Book of Military Anecdotes. Oxford University Press 1985, ISBN 0-19-214107-4 , p. 194 ( books.google.co.uk ).

- ↑ Marian Füssel : Waterloo 1815.Beck , Munich 2015, ISBN 3-406-67672-3 , p. 30.

- ^ Friederike Riedesel zu Eisenbach : Professional trip to America: Letters and reports from General and General von Riedesel written during the North American War in the years 1776 to 1783 , ed. by Claus Reuter, Berlin 1801.

- ↑ Friedrich Karl von Vechelde: Braunschweigisches Gedenkbuch for the twenty-five year celebration of the battles of Quatrebras and Waterloo: With a picture of the battlefield of Waterloo. Friedrich Otto, Braunschweig 1840. ( digitized version )

- ^ Waterloo Medal

- ^ Chronicle of the city of Braunschweig for 1940

- ↑ Jürgen Hodemacher : Braunschweig's streets, their names and their stories. Volume 1: Inner City. Elm-Verlag, Cremlingen 1995, ISBN 3-927060-11-9 , pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Jürgen Hodemacher: Braunschweigs streets - their names and their stories, Volume 3: Outside the city ring. Joh. Heinr. Meyer, Braunschweig 2002, ISBN 3-926701-48-X .

- ^ Britta Berg: Marienstift. In: Luitgard Camerer , Manfred Garzmann , Wolf-Dieter Schuegraf (eds.): Braunschweiger Stadtlexikon . Joh. Heinr. Meyer Verlag, Braunschweig 1992, ISBN 3-926701-14-5 , p. 153 .

- ↑ Jürgen Hodemacher: Braunschweigs streets - their names and their stories, Volume 1: Innenstadt . Elm-Verlag, Cremlingen 1995, ISBN 3-927060-11-9 , p. 87.

- ^ Erecting the monument in Burgdorf

- ^ NN: Braunschweig in the years 1806–1815. A list of images compiled for the exhibition of patriotic memories from the period from 1806 to 1815 organized in Braunschweig in June 1890. Braunschweig 1890, pp. 24–71.

- ↑ NN: Judicial finding in the indictment of Major v. Wachholz [sic!] Against the master carpenter Ernst Carl Külbel. Braunschweig, July 4th 1860.

- ^ Engraving by M. Dubourg after a painting by Manskirch.

- ↑ Lord Byron: Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Canto iii. Verses 21-30.

- ↑ Knight Harold's Pilgrimage. From the English of Lord Byron. Translated in the meter of the original by [Joseph Christian von] Zedlitz . Verlag der JG Cotta'schen Buchhandlung, Stuttgart / Tübingen 1836, 3rd song, verse 23, p. 126.

- ↑ With surgical needles against decay (with photos)

- ↑ Website of the "Ducal Brunswick Field Corps"

- ↑ The coffin of the "Black Duke" has been restored. In: Braunschweiger Zeitung. June 9, 2015 (chargeable).

- ↑ Heike Pöppelmann (Ed.): When is a hero a hero? The Black Duke 1815/2015. In: Small series of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum. Volume 7, Wendeburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-932030-66-6 .

Remarks

- ↑ In the first edition from 1859 Külbel gives the name with Auer (p. 5), in the second edition from 1865 the name is given as Aue (p. 6).

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Re-establishment as the Duchy of Braunschweig |

Duke of Braunschweig 1814–1815 |

Charles II |

| Friedrich August |

Duke of Oels 1806–1815 |

Charles IV |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Friedrich Wilhelm |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | The black duke |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Duke of Braunschweig, German military leader of the Napoleonic Wars |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 9, 1771 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Braunschweig |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 16, 1815 |

| Place of death | near Quatre-Bras , Belgium |