In the shackles of Shangri-La

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | In the shackles of Shangri-La |

| Original title | Lost Horizon |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1937 |

| length | 133 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 6 |

| Rod | |

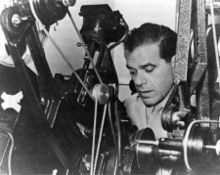

| Director | Frank Capra |

| script | Robert Riskin |

| production | Frank Capra for Columbia Pictures |

| music | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| camera | Joseph Walker |

| cut |

Gene Milford , Gene Havlick |

| occupation | |

| |

In the shackles of Shangri-La (original title: Lost Horizon ) is an American drama film directed by Frank Capra from 1937. Ronald Colman , Jane Wyatt and Edward Everett Horton played the main roles . The script was based on the utopian novel The Lost Horizon by James Hilton . The focus of the action is Shangri-La , a fictional place in Tibet where people live in peace and harmony . The premiere of the Oscar-winning film took place on March 2, 1937 in San Francisco .

Due to its pacifist message and criticism of the Western way of life , the film was massively cut and edited during the Second World War and the Cold War in the wake of the then US film censorship ; only the soundtrack remained of the premiere version . After the Hays Code was abolished , the American Film Institute initiated a restoration of the original film in 1973 . Over a period of 25 years, a number of missing scenes could be reinserted using film material that was visited worldwide .

The restored original version of Columbia TriStar was released in 1999, digitized in 4K format by Sony Pictures in 2013 , and premiered again in this version in 2014 at the Cannes International Film Festival . In the USA, the Library of Congress in 2016 classified Frank Capra's timeless masterpiece in the National Film Registry as "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant". For the 80th anniversary of the film, the restored version won the Saturn Award in 2018 as one of the best publications .

action

During an uprising in China in 1935, the pacifist British diplomat Robert Conway and his younger brother George tried to evacuate several foreigners from the (fictional) town of Baskul to Shanghai with hastily organized planes . He criticizes the fact that only “ whites ” can be flown out. In the last machine with which the refugees can take off, besides the two brothers, there are the American Henry Barnard, wanted for fraud, the English paleontology professor Alexander Lovett and the prostitute Gloria Stone, who is suffering from an incurable disease. The passengers fall asleep exhausted. It wasn't until the next morning that they noticed that the plane had deviated from its course and that an Asian pilot was behind the wheel instead of the British one. After a stopover, during which a mountain people provided aviation fuel, the plane crashed in a snowstorm in the Himalayas, far from civilization. When all hope of rescue seems to be lost, the group is found by strangers and taken to a remote valley called Shangri-La .

In Shangri-La, a valley of wonderful beauty, there are not only climatic paradisiacal conditions - unnoticed by the western world , the residents have created a Garden of Eden and consider their community to be the last oasis in which the spiritual treasures of mankind are kept, protected from wars and disasters. They live in harmonious peace and age only slowly. In the introduction, the monk Chang explains that the districts in Shangri-La are representative of the realm of the human soul, which in today's world is mortally harassed with its haste, its superficiality, its dogmas and its coercion. Chang goes on to explain that there are different religions in Shangri-La, including a Taoist and a Confucian temple further down the valley, and adds: “Every jewel has facets, and it is possible that many religions contain the moderate truth . "

Although the arrival of the group is not accidental, Robert and his companions quickly get used to the fabulous life. The seclusion forces the unwilling guests to self-reflection and inner probation. Robert slowly finds access to and trust in the High Lama of Shangri-La, a monk from Belgium who is over 200 years old. He reveals to him that he had the plane hijacked because he had taken from Robert's books and public actions that he longed for peace and belonged to Shangri-La. The High Lama explains the peculiarities and advantages of life in this small, secluded world, in which the lifespan of people with mental and physical youth is extended by a factor of 3 to 4:

“We are not miracle workers, we have neither conquered death nor decay. All we can do is slow down this short interlude called 'life'. We do this through methods that are as simple here as impossible anywhere else. But make no mistake, the end awaits us all. In these days of wars and rumors of wars, have you ever dreamed of a place where there is peace and security, where life is not a struggle but a lasting joy? Of course you have. Everyone has this dream. It's always the same dream. Some call this place Utopia, others call it fountain of youth. Look at the world today. Is there anything that is more pathetic? What madness! What a blindness! What a mindless leadership elite! A hasty mass of confused people clashing headlong and fueled by an orgy of greed and brutality. It is our hope that one day the brotherly love of Shangri-La will spread around the world. When the greedy have devoured one another and the meek inherit the earth, Christian ethics can finally be fulfilled. "

Increasingly, Robert and his companions feel happy and satisfied in the new environment. Only George longs to return to civilization and his former existence, although Maria, a young girl from Shangri-La, loves him passionately and encourages him to stay. Chang says that Maria is actually almost 70 years old and that she owes her youth and beauty to the miraculous power of Shangri-Las. Robert also falls in love with a resident, the mysterious and beautiful Sondra. In addition, a warm affection develops between Gloria, who is regaining her health, and Henry, who both leave their dark past behind them.

Shortly before his death, the High Lama asked Robert to take over the leadership and responsibility of Shangri-La. However, George arouses doubts in Robert about the miraculous power of the place and moves him to leave Shangri-La with Maria and a group of untrustworthy Sherpas . On the way through the snow-capped mountains, the brothers and Maria lose touch more and more. To get rid of the ballast, the Sherpas shoot in the direction of the falling back. The gunshots set off a snow avalanche that buries all Sherpas under itself. Robert, George and Maria find refuge in a cave where Maria suddenly ages and dies. Now George realizes that he wrongly deprived his brother of his belief in Shangri-La. Seized by madness and remorse, he leaps to death from a high mountain range.

Robert reaches civilization with the last of his strength and is cared for in a hospital. A series of telegrams to the Prime Minister in London make it clear that he had amnesia but is now to be brought back to England by the British embassy official Lord Gainsford. However, Robert regains his memory and flees shortly before leaving to return to Shangri-La. After ten months of searching for Robert, Gainsford gives up and returns to London. He tells his club members about Robert's amazing adventures and attempts to find his lost horizon. While the men toast Robert's success, Roberts returns to Shangri-La under adventurous circumstances, where he can realize his dream of peace.

production

Frank Capra was, according to later statements by his son , deeply affected by the effects of the Great Depression , but did not give up hope for a better world. Like millions of other people, he was fascinated by the novel Lost Horizon by the young British writer James Hilton , who, with his paradise, Shangri-La, had created the ideal image of a human community. For Capra it was clear that a people mentally battered by the depression had to believe in the realization of a community in peace and harmony. At the time, Frank Capra was considered the highest paid director in Hollywood and could shoot whatever he wanted.

Columbia Pictures acquired the film rights as early as 1934 on behalf of Capra . Joseph Walker , who worked with Capra on a total of 18 films, was hired as cameraman . The writer wrote Capra also longtime collaborator Robert Riskin . James Hilton was on hand to advise. Essentially, the later original version of the film corresponded to the novel. The characters of Sondra and the amusing professor Alexander Lovett, both of which do not appear in the novel, have been added for romantic reasons. Hilton approved of these differences.

The start of filming was delayed due to numerous auditions considerably and screen tests. For Capra, Ronald Colman could only play the main role as Robert Conway, who was also involved in other productions, so the start of shooting was postponed further. David Niven and Louis Hayward , among others, auditioned for the role of George Conway ; Capra only decided on John Howard two days before filming began . Rita Hayworth took part in the selection process for the role of Maria , who eventually got Margo Albert . Several then very well-known actors could be won for the supporting roles, such as David Torrence , Lawrence Grant , Willie Fung , Richard Loo and Victor Wong . Capra had big arguments with Harry Cohn , the studio boss of Columbia Pictures, when casting the role of High Lama. Cohn didn't like the Sam Jaffe recordings and insisted that Capra replace him with Walter Connolly . Capra bowed to this request and even had a new, expensive set built especially for Connolly at Cohn's request . Ultimately, the two of them agreed that the recordings with Connolly weren't nearly as good as the ones with Jaffe. As a result, he got his part back, for which all of his scenes had to be shot again.

The Shangri-La set, which Stephen Goosson built with 150 workers in a construction period of two months, was an extraordinary artistic achievement and is still considered to be the largest film set ever built in Hollywood. Originally, Capra wanted to shoot the film in color using the new Technicolor process . Harry Cohn refused this not only because of the extremely higher material costs. In the mid-1930s, it was technically difficult to take pictures of avalanches and snow-covered high mountains, which is why black and white film material from a documentary about mountain sports in the Alps had to be used for these scenes .

Filming began on March 23, 1936. They ended on July 17, 1936 and thus lasted a hundred days, 34 more than planned. Outdoor scenes were created in Ojai , Palm Springs , Victorville , Griffith Park and Idyllwild-Pine Cove , among others . The lama line was built on Columbia Ranch in Burbank, Los Angeles County . The valley of the blue moon was in the San Fernando Valley , about 40 miles northwest of Hollywood. The Baskul riot scene originated at Los Angeles Municipal Airport . A Douglas DC-2 was used , with which Capra also had several recordings made in the air. The refueling sequence for the hill tribe took place on a dry lake in the Mojave Desert . Many scenes could be realized in the ice and cold store in Los Angeles , where Capra had 13,000 square meters of cooling space available. The camera team had great difficulties with the equipment because the extreme cold generated static electricity . Tons of plaster of paris and bleached corn flakes were used for the recordings in the snowstorm .

The budget planning was $ 1.5 million. In the end, Lost Horizon cost twice as much, making it the most expensive film in cinema history at the time. For comparison: $ 3 million in 1936 corresponds to the purchasing power of around $ 55 million in 2018.

Awards

In 1938, Lost Horizon was nominated for seven categories at the 10th Academy Awards . Stephen Goosson won the Oscar for best artistic direction with the film's lavish sets . Gene Havlick and Gene Milford shared the Oscar for Best Editing . Five other nominations were made in the following categories:

- Best movie

- Best Supporting Actor ( HB Warner )

- Best Assistant Director ( Charles C. Coleman )

- Best note ( John Livadary )

- Best Film Score ( Morris Stoloff ).

The American Film Institute (AFI) repeatedly nominated the premiere version of the film for the categories:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies (List of the best films)

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores (list of the best film scores)

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Movies - 10th Anniversary Edition (Greatest Movies List)

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 (List of the Best Fantasy Films)

In 2016, the US Library of Congress classified Frank Capra's timeless masterpiece in the National Film Registry as "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant". For the 80th anniversary of the film, the restored version won the Saturn Award in 2018 as one of the best publications .

Edits

In film studies, lacuna is an accessible gap in old films, the cause of which can be traced back, among other things, to the mechanical destruction of part of the material or the censoring of films with the subsequent destruction of entire parts of the text. One of the most prominent examples of this is Frank Capra's Lost Horizon , which was 360 minutes long in the first cut, premiered in a 210-minute rehearsal and a 132-minute version , after which it underwent massive cuts and adaptations several times due to its pacifist tendencies and not only recovered scenes, but also with black screen and occasional still images (slide show) later restored could be.

original version

After completing the shooting and the first cut , Frank Capra had around six hours of usable film material available, whereupon the studio considered a multi-part series . Such sequels were largely considered unpopular and financially risky at that time. As a result, Capra had Gene Havlick and Gene Milford shorten the material to 210 minutes for a preview . This preview took place on November 22, 1936 in Santa Barbara and was received negatively by the majority of the audience. The test subjects had previously seen the screwball comedy Theodora Goes Wild and then couldn't get excited about an epic drama of 3½ hours. Sometimes the audience laughed at sequences that should be meant seriously; many left the cinema prematurely. Frank Capra is said to have been so disappointed with the reactions that he retired to a weekend house on Lake Arrowhead for several days and was not available to anyone.

This was followed by several months of revision of various scenes. For this purpose, Capra shot more shots with the High Lama in January 1937 and placed more emphasis on a pacifist message and an empathetic reference to the world situation at that time. After these cuts, Lost Horizon was successfully premiered on March 2, 1937 in San Francisco with a length of 132 minutes. The subsequent marketing took place via a roadshow attraction in selected US cities with only two performances per day and pre-reserved seats. Ultimately, Lost Horizon was a critically acclaimed film that went on sale worldwide in September 1937 .

Propaganda versions

Towards the end of the 1930s, the production and distribution of feature films in the United States was increasingly regulated and monitored. At the latest when the United States entered World War II , all films had to be submitted to the Production Code Administration (PCA), which was directly assigned to the United States Office of War Information (OWI). All studios were under the government and had the task of supporting the warfare of the USA. The OWI was an additional instrument for controlling the content of American film production and issued licenses from 1942, without which no film could be made. As a result of this censorship, studios withdrew films "voluntarily" from the distribution, or re-released older films, which were often completely re-edited to reflect the current view of the US government. Various productions by Frank Capra were affected by this.

Shangri-La had an extraordinary and far-reaching effect on Franklin D. Roosevelt . Historians describe the influence of this fiction on the then US president as a downright obsession . In order to increase the willingness of the US population to go to war, Roosevelt cited a complete passage from Lost Horizon in his famous " Quarantine Speech " as early as October 1937 . In 1939 he renamed the Roosevelt family seat in Indio (California) and in 1942 even the country seat of the US presidents in Shangri-La (from 1954 Camp David ). At a press conference on April 21, 1942, Roosevelt replied to the question of where the planes had started in the Doolittle Raid , a surprise attack on Tokyo: "They came from our new base at Shangri-La." The reporters responded with loud laughter . Later received aircraft carrier of the Essex class named USS Shangri-La .

The new edition of Lost Horizon was triggered personally by James Harold Doolittle , who was in close contact with Franklin D. Roosevelt and had been entrusted with the development of air strikes on Japan . Accordingly, the producers of Columbia Pictures changed the title of the film to The Lost Horizon of Shangri-La in 1942 and cut 24 minutes from the world premiere version. In the first film adaptation of the novel was written in the opening credits :

"Our story begins in the ancient Chinese city of Baskul, where Robert Conway was sent to evacuate ninety whites from a local uprising ... Baskul, the night of March 10, 1935."

The original version from 1937 left open who the local rebels were. In the 1942 version, the opening sequence was completely rewritten, which completely changed the historical background of the film and the characters of the antagonists . So it was now:

“The story begins in the ancient Chinese city of Baskul, ravaged by invaders from Japan, where Robert Conway tries to evacuate ninety white people so they won't be slaughtered by the Japanese hordes ... Baskul, the night of July 7th, 1937 . "

The Chinese rebels were not only transformed into Japanese "hordes": the date of the action now coincided with the incident at the Marco Polo Bridge . The transformation was particularly unrealistic because this event, which triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War , only took place after the film was originally completed and premiered. In addition, all scenes were cut out in which Robert Conway expressed criticism of the British Empire , but mostly protested against the conduct of wars in general.

Like all later shortened versions, the new edition was advertised unchanged as "a Frank Capra film from 1937". In fact, Capra had already ended its collaboration with Columbia Pictures before 1942 due to unsettled adaptations in various of his films and founded Frank Capra Film Production together with his long-time screenwriter Robert Riskin . Capra, who later referred to Lost Horizon as “one of his greatest films”, said of the new edition that “the film no longer makes sense without the scenes”. The film historian Leslie Halliwell came to the same conclusion . He described the missing sequences as "vital" for the film.

Regardless, The Lost Horizon of Shangri-La from 1942 developed into a complete success for the Columbia producers. Only with this 110-minute version was it possible to achieve an enormously high distribution and significantly exceed the break-even point . This was not least due to the United Service Organizations , which used the film to propaganda against Japan in troop support .

Even more massive cuts were made during the McCarthy era . In 1952 Columbia Pictures eliminated all scenes and dialogues that could even remotely be associated with pacifist utopias and pro-communist ideals . From then on, a 95-minute version was shown, which was cut several times for later television productions and was finally 66 minutes.

American film historians later judged the changes: " Lost Horizon is less utopia than propaganda and has always developed along with the respective political situation in the United States." In 1967, the political situation in the USA changed as a result of the rupture between the Once again changed by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China , Columbia Pictures found during an examination that the original negatives were no longer complete and that the reels that were still there could no longer be repaired.

restoration

After the Hays Code was abolished , Columbia Pictures handed over the original remains of the nitrate film to the American Film Institute , founded in 1967 , which initiated the restoration of the world premiere in 1973 . The project was carried out by the UCLA Film Archives at the University of California at Los Angeles and funded by Columbia Pictures. In 1974 the restorer Robert Gitt began looking for missing material in various film archives around the world. In total, his efforts to restore the film lasted 25 years. In the early phase of the restoration, Gitt was supported by Frank Capra, who, however, had to withdraw from the project due to his old age and after several heart attacks . Capra is said to have been particularly pleased with the recovered scenes and dialogues of Sam Jaffe as High Lama on peace and brotherhood.

In London, Robert Gitt discovered a complete soundtrack of the 132-minute version and three minutes of the footage previously believed to be lost at the British Film Institute . In 1978 he tracked down a 16mm film in Canada that was in French but contained more of the missing scenes. Until 1986, all 132 minutes of the original soundtrack and 125 minutes of footage (in different quality levels) could be restored. Gritt replaced the missing seven minutes with still existing slides of the actors in costumes during the filming. This restored version was first presented to the public in January 1986 in the presence of the then only surviving leading actors Jane Wyatt and John Howard at the Park City Film Music Festival in Utah and then to the public in over 50 US cities by the end of the year. In an interview, John Howard said:

“I was thrilled to see the restored version. The last time I saw the film on TV, I thought it was ground beef. Only through the reinserted scenes are the characters understandable. There was a cut out dialogue between Ronald Colman and me on the plane on the way to Shangri-La, which conveyed how important it was for Robert Conway to prevent another world war. For me it's a very important scene. "

In 1999, Columbia TriStar Home Video released the previously restored version on DVD in English with subtitles available in Spanish, Portuguese, Georgian, Chinese and Thai . Bonus features included three deleted scenes, an alternate ending, a restoration commentary by Charles Champlin and Robert Gitt, and photo documentation with explanations by film historian Kendall Miller. Another DVD of this version with the same bonus features, plus the original cinema trailer, was released in 2001 in English and dubbed in French, German, Italian and Spanish, with subtitles in English, Spanish, German, French, Italian, Hindi, Portuguese, Turkish, Danish, Icelandic, Bulgarian, Swedish, Hungarian, Polish, Dutch, Arabic, Finnish, Czech and Greek on the market.

On a very poorly preserved 16-millimeter film, a total of one minute of the missing scenes was rediscovered in 2013 and integrated into the still incomplete 132-minute version. The imagery replaced still images that until then had to be used for scenes during Conway's meeting with the High Lama. This newly reconstructed version was digitized in 4K format by Sony Pictures in the same year and premiered again at the Cannes International Film Festival in 2014 .

In 2017, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment released the film on Blu-ray , which contains material lost a minute earlier. The total running time is 133 minutes. The opening credits were extended by about a minute with explanations of the reconstruction. About five minutes of the original version are still missing. As in previous DVD versions, these scenes replace still images with continuous sound. The bonus features and comments of the DVD versions have been retained in the Blu-ray edition.

German versions

The German first edition of the novel Lost Horizon was published in 1937 under the title Irgendwo in Tibet by Herbert Reichner Verlag (Vienna-Leipzig-Zurich) , which sold most of its production in Germany. Registered in the Reichsfilmarchiv with card number 3168, title signature Das verlorene Paradies (The Lost Horizon) , the film was released in the spring of 1938 in the original version with German subtitles in German-language cinemas and was advertised on posters and in film magazines.

It is unclear in which year the film fell victim to censorship in the Third Reich . According to unproven statements, Lost Horizon is said to have been banned because of its pacifist content in the course of war preparations in Germany. In contrast, the American journal The Hollywood Reporter stated that the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda had banned the film on the grounds that it (quote): "hurts our [German] holiest feelings and also our artistic souls". This statement also contradicts other sources, according to which the film was withdrawn from distribution due to a copyright conflict . In fact, according to assistant director Andrew Marton , several cuts were made from recordings from two German mountain sports films. There is no reliable evidence for any of these depictions, as the majority of the holdings in the Reich Film Archive was stored in the Berlin bell tower and was lost in a fire in 1945. Even the index cards of the Reichsfilmarchiv are only available to the Federal Archives in fragments.

According to recent research results, foreign films that were approved by the censors were shown in German cinemas throughout the period of National Socialism, and in special screenings for certain groups of people even those that were not approved. In general, Frank Capra's socially critical films were considered unproblematic, at least probably until 1942, because of the sometimes open criticism of the American way of life in Germany. In addition, Capra was a staunch Republican and repeatedly criticized the policies of the Democrats , especially in the person of Franklin D. Roosevelt . Although basically all American films in Germany were withdrawn from distribution when the United States entered World War II (as were all German films in the United States, by the way), Joseph Goebbels is said to have worked intensively on the showing rights of Capra's film Mr. Smith goes to Washington to have tried hard. By 1942 at the latest, with Capra's propaganda films Why We Fight , all of his films are likely to have been banned in Germany.

In Switzerland , the original version with subtitles was also released for the first time in 1938 under the title The Lost Horizon . As Orizzonte perduto (Lost Horizon) the film was shown in Italy, an ally of Germany, from 1937 onwards; and, for example, in Hungary under the title A kék hold Völgye (The blue moon valley), it can be proven that at least 1941.

The first German dubbing took place in 1950 by Ala-Film GmbH Munich under the dubbing direction of Conrad von Molo in the revised US version from 1942. The first screening in German took place on March 13, 1950. According to the description in the opening credits of this version, the plot has generally been relocated to the time during the Second World War. From then on, the film received the title In den Fesseln von Shangri-La in German-speaking countries .

On July 2, 1979, the film was first broadcast on German television , re-dubbed in an edited US version from 1952. Based on the dialogue book and under the dialogue direction by Hilke Flickenschildt , the Berlin dubbing company Wenzel Lüdecke realized a dubbing of the restored version in 2000 . The DVD (127 minutes) was released in German in 2001. The original version (133 minutes), almost completely restored with missing scenes, has been on the market in German on Blu-ray in very good quality since November 9, 2017 .

| role | actor | Voice actor 1950 | Voice actor 1979 | Voice actor 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Conway | Ronald Colman | Ernst Fritz Fürbringer | Hellmut Lange | - |

| Sondra Bizet | Jane Wyatt | Eleanor Noelle | Marianne Bernhardt | - |

| Alexander Lovett | Edward Everett Horton | - | Klaus Miedel | Michael Brennicke |

| George Conway | John Howard | Ulrich Folkmar | Lutz Mackensy | - |

| Chang | HB Warner | - | Hans Paetsch | Friedrich Schoenfelder |

| Henry Barnard | Thomas Mitchell | - | Günther Jerschke | - |

| Maria | Margo | - | - | Bianca Krahl |

| Gloria Stone | Isabel Jewell | - | Katrin Miclette | - |

| the high lama | Sam Jaffe | - | Hans Hessling | Eric Vaessen |

Trivia

The film was in the late 1930s to a media hype and significantly to the myth of Shangri-La in. Lost Horizon has had a lasting impact on the western view of Tibet and Lamaism to this day, although the name Shangri-La, as a synonym for paradise or an ideal retreat from world events, has a certain life of its own in the vernacular of many countries. Examples:

- Countless shops and restaurants around the world bear the name Shangri-La .

- In Denver , an eccentric millionaire had an exact replica of the Shangri-La llamas seen in the film built as a villa.

- The millionaire heiress Doris Duke christened her luxurious estate in Hawaii on Shangri-La .

- Participants of Victoria University's Antarctic Expeditions gave 1961 a completely isolated by mountains Valley in Victoria Land the name Shangri-La .

- In 1963 an American girl group called itself The Shangri-Las .

- From 1963 to 1973, an Italian racing driver under the pseudonym Shangri-La competed regularly in international car races.

- The multi-billionaire Robert Kuok founded the luxury hotel chain Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts in 1971 .

- Steve Bing and Adam Rifkin founded the film production company Shangri-La Entertainment in 2000 .

- In 2001 the Tibetan town of Zhongdian was renamed Shangri-La .

- The Shangri-La Dialog is an annual security forum of the International Institute for Strategic Studies that has been held since 2002 .

- In 2004, Mark Knopfler titled his fourth solo album with Shangri-La .

- The tallest skyscraper in Vancouver was named Living Shangri-La after its completion in 2009 .

- In the English-speaking world in particular, a quote from the film is widely used as a saying : “Even in Shangri-La the doors have locks.” (“Even in Shangri-La the doors have locks.”).

Furthermore, according to various accounts, Heinrich Himmler is said to have fallen under the spell of myth and sent several Tibet expeditions in search of Shangri-La. Influenced by this, an adventure game named Lost Horizon , which was awarded the German Developer Prize , was released in 2010 , in which SS soldiers can be hunted in a Shangri-La SS soldier that is virtually reproduced from the film . In 2015 the game Lost Horizon 2 followed .

In 1956, the Broadway musical Shangri-La , composed by Harry Warrens , was premiered . The musical was produced in 1960 under the same title by George Schaefer as a television film and in 1973 by Ross Hunter under the title Lost Horizon (dt. The lost horizon ) as a film musical .

Sequences from Frank Capra's original version have been adapted in countless other films . For example, in Steven Spielberg's Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the airplane scenes, the unnoticed change of pilot and the crash in the Himalayas resemble the plot of Lost Horizon .

Reviews

Lost Horizon's status as a groundbreaking classic adventure film has been undisputed for over 80 years. The New York Herald Tribune , one of the leading and most influential newspapers in the United States at the time, stated in a review in March 1937 (excerpts):

"In exciting scenes, Frank Capra filmed the strange story of a group of people who ended up in the timeless utopia of a Tibetan paradise. It is a triumph of ingenuity and image integrity that the film has retained so much of the profound spell of its original. The main attraction is the empathic imagination and its philosophy. The viewer is shown an escapist paradise with the secrets of a Tibetan nirvana, with which he can break through the grids of reality in a restless world. It is remarkable that the film preserves the book's thoughtful quality so well. Lost Horizon is a real success in the art of film. "

In July 1979, the Spiegel described the film in a program preview as an “opulent melodrama about a nirvana in Tibet” and as a “classic of sophisticated comedy in New Deal America ”, whereby this assessment was based on the dubbed version at the time. A criticism that is often still performed in various media in the German-speaking world comes from the Filmdienst (as of 2018), according to which Capra's work is a “fantastic film adaptation of the old human dream of absolute external and internal peace” as well as “a romantic and pessimistic allegory that is particularly fascinating due to its atmosphere "Which deals with" the escape from the real world, but not the confrontation with it. "This review also does not refer to the original, but an abridged 97-minute version from before 2001.

In current reviews, In the Fetters of Shangri-La is mostly positively rated. So the message of the film has lost none of its relevance, in particular the pacifist approaches speak for themselves, even if they can seem a bit naive today. In a comprehensive review in March 2017, The Huffington Post praised the restoration work of the American Film Institute and the film's “unchanged fascinating features”. Particular mention should be made of “scenes that lend the film life, such as the evacuation of the refugees; the events and dialogues during the flight to Tibet; Conway's conflicts and split loyalty, his sense of loyalty and responsibility; the unwise attempt to escape; and Conway's adventurous return. "In particular," the characters in the film provided a lot of empathy , which did not affect the themes and messages of the novel. "

In 2018, 92 percent of Rotten Tomatoes ' critics rated “Frank Capra's timeless masterpiece” positively. At the same time, the Motion Picture Editors Guild , the most important professional association of American film and television editors , ruled : "Like Shangri-La, Lost Horizon has proven to be timeless - and that is his legacy."

Web links

- Mein Film - Illustrierte Film- und Kinorundschau, issue 635 from February 25, 1938, p. 19 in: Austrian National Library , accessed on June 6, 2018

- Lost Horizon in the Internet Movie Database (English), accessed on June 6, 2018

literature

- Victor Scherle, William Turner Levy: The Complete Films of Frank Capra . Citadel Press, 1992.

- James Hilton : The Lost Horizon. Novel . Unabridged paperback edition, Piper, 2003.

- Bodo Traber: In the shackles of Shangri-La. In: Bodo Traber, Hans J. Wulff (Hrsg.): Filmgenres. Adventure. Reclam, 2004.

- John R. Hammond: Lost Horizon Companion. A Guide to the James Hilton Novel and Its Characters, Critical Reception, Film Adaptations and Place in Popular Culture. McFarland & Company, 2008.

- Stephanie Wössner: Lost Horizon. A film review. GRIN Verlag, 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Online film database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La. Sony Pictures In: ofdb.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ In the Shackles of Shangri-La. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed June 5, 2018 .

- ↑ American Film Institute Catalog of feature films, Details of 'Lost Horizon' (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ↑ Jerry Hopkins: Romancing the East: A Literary Odyssey from the Heart of Darkness to the River Kwai. Tuttle Publishing, 2013, p. 151.

- ^ University of Kiel: Lexicon of film terms: Lacuna, special case Lost Horizon . In: filmlexikon.uni-kiel.de, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ Stephen Farber: Cuts in film 'Lost Horizon' restored. New York Times , September 3, 1986. In: Online Archives New York Times, accessed June 5, 2018

- ↑ Sony Pictures Entertainment: Brief Description In the Shackles of Shangri-La. in: sphe.de Film presentation, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ Cannes Classics 2014: Lost Horizon (Horizons Perdus) by Frank Capra (1937, 2h12) In: Archives Festival de Cannes, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ The Digital Bits: Lost Horizon 1937 (1999) - Columbia TriStar In: thedigitalbits.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ^ Ashley Hoffman: These 25 Movies Were Just Added to the National Film Registry. Time Magazine, December 14, 2016. In: Archives Time Magazine, accessed June 6, 2018

- ^ Awards In the Fetters of Shangri-La (1937) , Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA 2018. In: Internet Movie Database IMDb.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ↑ a b c d Internet Movie Database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La (1937). Quotes. In: imdb.com, accessed June 12, 2018

- ↑ Mein Film - Illustrierte Film- und Kinorundschau, Issue 635 of February 25, 1938, p. 19. In: ÖNB - ANNA Austrian National Library , accessed on June 5, 2018

- ↑ Hal Erickson: Lost Horizon (1937). Allmovie Rhythm One group, 2018. In: Allmovie.com , accessed June 12, 2018

- ↑ Kevin Lewis: Topic of Capra-Cohn. The Battle over Lost Horizon. Editors Guild Magazine, No. 20056, Feb. 23, 2011.

- ↑ Barry Gewen: It Wasn't Such a Wonderful Life. The New York Times, May 3, 1992. In: nytimes.com, accessed June 17, 2018

- ↑ American Film Institute Catalog of feature films, Details of 'Lost Horizon' (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ↑ American Film Institute Catalog of feature films, Details of 'Lost Horizon' (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 16, 2018

- ↑ Internet Movie Database (English): Trivia. In the Shackles of Shangri-La (1937). In: imdb.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Sony Pictures Entertainment: Brief Description In the Shackles of Shangri-La. in: sphe.de Film presentation, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ Joseph McBride: Frank Capra. The Catastrophe of Success. Touchstone Books, 1992, p. 351.

- ↑ Kevin Lewis: Topic of Capra-Cohn. The Battle over Lost Horizon. Editors Guild Magazine, No. 20056, Feb. 23, 2011.

- ↑ American Film Institute Catalog of feature films, Details of 'Lost Horizon' (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 16, 2018

- ↑ Kevin Lewis: Topic of Capra-Cohn. The Battle over Lost Horizon. Editors Guild Magazine, No. 20056, Feb. 23, 2011.

- ↑ Inflation calculator dollar 1935 to dollar 2018 In: dollartimes.com, accessed on June 17, 2018

- ↑ Academy Awards 1938, USA In: Internet Movie Database IMDb.com, accessed June 5, 2018

- ↑ Nominations American Film Institute In: afi.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Nominations American Film Institute In: afi.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Nominations American Film Institute In: afi.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Nominations American Film Institute In: afi.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ^ Ashley Hoffman: These 25 Movies Were Just Added to the National Film Registry. Time Magazine, December 14, 2016. In: Archives Time Magazine, accessed June 6, 2018

- ^ Awards In the Fetters of Shangri-La (1937) , Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, USA 2018. In: Internet Movie Database IMDb.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ^ University of Kiel: Lexicon of film terms: Lacuna, special case Lost Horizon . In: filmlexikon.uni-kiel.de, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ Stephen Farber: Cuts in film 'Lost Horizon' restored. New York Times , September 3, 1986. In: Online Archives New York Times, accessed June 5, 2018

- ^ Rudy Behlmer: Behind the Scenes. Samuel French Books, 1990, p. 362.

- ↑ American Film Institute Catalog of feature films, Details of 'Lost Horizon' (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ↑ Joseph McBride: Frank Capra. The Catastrophe of Success. Touchstone Books, 1992, pp. 369-370.

- ↑ Juliane Scholz: The screenwriter. USA - Germany. A historical comparison. Transcript Verlag, 2016, pp. 205 ff.

- ↑ Michael Baskett: The Attractive Empire. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Roger K. Miller: Looking for Shangri-La. The Denver Post, February 14, 2008. In: denverpost.com, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Lezlee Brown Halper, Stefan Halper: Tibet. An unfinished story. Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 21 ff.

- ↑ Peggee Standlee Frederick: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's "Shangri-La". Archived from the original on September 28, 2013 ; accessed on July 1, 2018 .

- ↑ Joseph E. Persico: Roosevelt's Centurions. Random House Publishing Group, 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Lewis E. Lehrman: Churchill, Roosevelt & Company. Studies in Character and Statecraft. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017, p. 28 ff.

- ↑ Joseph McBride: Frank Capra. The Catastrophe of Success. University Press of Mississippi, 2011, p. 370.

- ↑ Michael Baskett: The Attractive Empire. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p. 112.

- ↑ Michael Baskett: The Attractive Empire. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p. 112.

- ↑ Michael Baskett: The Attractive Empire. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Michael Baskett: The Attractive Empire. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p. 112 ff.

- ^ John Whalen-Bridge, Gary Storhoff: Buddhism and American Cinema. SUNY Press, 2014, p. 74.

- ↑ Joseph McBride: Frank Capra. The Catastrophe of Success. Touchstone Books, 1992, p. 366.

- ^ Leslie Halliwell: A Nostalgic Choice of Films from the Golden Age. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1982, pp. 180-183.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database (English): Trivia. In the Shackles of Shangri-La (1937). In: imdb.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Joseph McBride: Frank Capra. The Catastrophe of Success. Touchstone Books, 1992, pp. 369-370.

- ↑ Lost Horizon In: tvtropes.org, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Kevin Lewis: Topic of Capra-Cohn. The Battle Over 'Lost Horizon'. The Motion Picture Editors Guild, 2005. ( October 21, 2007 memento on the Internet Archive ) In editorsguild.com, accessed July 1, 2018

- ^ John Whalen-Bridge, Gary Storhoff: Buddhism and American Cinema. SUNY Press, 2014, p. 74.

- ↑ Stephen Faber: Cuts in film 'Lost Horizon'. New York Times, September 3, 1986. From nytimes.com, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Stephen Farber: Cuts in film 'Lost Horizon' restored. New York Times , September 3, 1986. In: Online Archives New York Times, accessed June 5, 2018

- ^ Leslie Halliwell: A Nostalgic Choice of Films from the Golden Age. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1982, pp. 180-183.

- ↑ Stephen Farber: Cuts in film 'Lost Horizon' restored. New York Times , September 3, 1986. In: Online Archives New York Times, accessed June 5, 2018

- ↑ The Digital Bits: Lost Horizon 1937 (1999) - Columbia TriStar In: thedigitalbits.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ↑ Cannes Classics 2014: Lost Horizon (Horizons Perdus) by Frank Capra (1937, 2h12) In: Archives Festival de Cannes, accessed on June 6, 2018

- ↑ The Digital Bits: Lost Horizon 1937 (1999) - Columbia TriStar In: thedigitalbits.com, accessed June 6, 2018

- ^ Murray G. Hall: Austrian publishing history. Herbert Reichner Verlag (Vienna-Leipzig-Zurich). CIRCULAR. Special issue 2, October 1981, pp. 113-136. In: verlagsgeschichte.murrayhall.com, accessed June 8, 2018

- ↑ Mein Film - Illustrierte Film- und Kinorundschau, Issue 635 of February 25, 1938, p. 19. In: ÖNB - ANNA Austrian National Library , accessed on June 5, 2018

- ^ Federal Archives (Germany): The card files of the Reichsfilmarchiv. Title signature 3168, verlorene Paradies, Das (The lost horizon) , p. 205. In: bundesarchiv.de, accessed on June 5, 2018

- ↑ Dirty Pictures: Film No. 55, The Lost Horizon (OT: Lost Horizon, USA 1937) In: dirtypicture.de, Film-Kurier No. 1836, accessed on June 12, 2018

- ↑ Stephanie Wössner: Lost Horizon - A film review. GRIN Verlag, 2009, p. 2 f.

- ↑ American Film Institute: Lost Horizon (1937) In: afi.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ^ Sarah Rayne: Roots of Evil. Simon & Schuster, 2008, p. 177.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database (English): Trivia. In the Shackles of Shangri-La (1937). In: imdb.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ^ Federal Archives (Germany): The card files of the Reichsfilmarchiv. S. 2. In: bundesarchiv.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ Ingo Schiweck: Because we prefer to sit in the cinema than in sackcloth and ashes. Waxmann Verlag, 2002, p. 31.

- ↑ Markus Spieker: Hollywood under the swastika. The American feature film in the Third Reich. Scientific publishing house Trier, 2003, CD-ROM.

- ^ Richard Plaut: Taschenbuch des Films. A. Züst, 1938, p. 138.

- ↑ Magyar Film (film magazine): A kék hold Völgye (Lost Horizon) , May 3, 1941, advertisement on p. 2. In: epa.oszk.hu, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ Internet Movie Database (English): Release Info. In the Shackles of Shangri-La (1937) In: imdb.com, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Voice actor database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La (1937); Synchronized (1950) ( Memento from April 8, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: synchrondatenbank.de, accessed on June 5, 2018

- ↑ Online film database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La. Columbus Film, release date: March 13, 1950. In: ofdb.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ Prisma Verlag: Fantasy film: In the fetters of Shangri-La. In: prisma.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ Voice actor database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La (1937); Synchronized (1979) ( Memento from March 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: synchrondatenbank.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ In the Shackles of Shangri-La. In: synchronkartei.de. German synchronous index , accessed on June 6, 2018 .

- ↑ Online film database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La. Columbia Tristar, 2001 In: ofdb.de, accessed June 11, 2018

- ↑ Online film database: In the Fetters of Shangri-La. Sony Pictures, release date: November 9, 2017 In: ofdb.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ^ Claudia Frickel: Mystery. The hidden paradise of Shangri-La . Web.de-Magazin, June 7, 2017. In: web.de Magazine, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ^ The search for the "micro-Shangri-La" as a place of retreat in the age of globalization In: internetloge.de, accessed on June 12, 2018

- ↑ Notes from Lost Horizon (1937) in: watershade.net, accessed June 27, 2018

- ↑ Peter Dittmar: Where the greatest happiness resides . Die Welt , August 15, 2006, in: welt.de, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ^ Claudia Frickel: Mystery. The hidden paradise of Shangri-La . Web.de-Magazin, June 7, 2017. In: web.de Magazine, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ↑ Peter Dittmar: Where the greatest happiness resides . Die Welt , August 15, 2006, In: welt.de, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ^ Till Boller: The cinematic computer game check. Lost Horizon. Moviepilot.de, October 27, 2010. In: moviepilot.de, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ↑ German Developer Award 2010: Jury selects Lost Horizon as Best Adventure. In: adventurespiele.de, accessed on June 7, 2018

- ^ William T. Leonard: Theater. Stage to screen to television. Volume 1. Scarecrow Press, 1981, p. 917.

- ↑ Ian Scott: In Capra's Shadow. The Life and Career of Screenwriter Robert Riskin. University Press of Kentucky, 2015, p. 119.

- ↑ Lost Horizon (1937) In: theraider.net, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Lost Horizon . Hufftingtonpost, March 30, 2017. In: hufftingtonpost.com, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Der Spiegel: This week on television (Monday, July 7, 1979, 11 pm. ARD. In shackles by Shangri-La.), Der Spiegel, 27/1979. In: spiegel.de, accessed on June 11, 2018

- ↑ In the Shackles of Shangri-La. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed April 8, 2017 .

- ↑ Blu-ray Disc Review: In the Shackles of Shangri-La . in: blurayreviews.ch, accessed on June 12, 2018

- ↑ Lost Horizon - the 1937 movie adaptation of the James Hilton novel features a pacifist action-adventure hero and a preternatural high lama, and a fantastic climate change. Hufftingtonpost, March 30, 2017. In: hufftingtonpost.com, accessed July 1, 2018

- ↑ Tomatometer Lost Horizon (1937) in: rottentomatoes.com, accessed on June 5, 2018

- ↑ Kevin Lewis: Topic of Capra-Cohn. The Battle Over 'Lost Horizon'. The Motion Picture Editors Guild, 2005. ( October 21, 2007 memento on the Internet Archive ) In editorsguild.com, accessed July 1, 2018