Phoenicians

The Phoenicians (also Phoenicians or Phoenicians ) were a Semitic people of antiquity , who lived in the 1st millennium BC. Settled the Levant . The geographical area known as Phenicia extends along the eastern Mediterranean coast and its hinterland , with the Carmel Mountains as a natural border. The northernmost Phoenician city is Aruad , the southernmost city is Dor . The most influential Phoenician city-states were Akko , Aruad, Byblos , Beirut , Sidon, and Tire . The area is located in what is now Lebanon , Syria and Israel .

General

The ethnic groups of the Levant, known as the “Phoenicians”, were organized in city-states and did not form a single empire. The area known as “Phenicia” is a series of city-states. Although the Phoenician city-states were largely autonomous, for a long time they were under the influence of great empires such as Egypt , Assyria , Babylonia and finally the Persian Empire .

The Phoenician city-states specialized in trade and shipping and were heavily involved in the flourishing Mediterranean trade. Their economic heyday lasted from around 1000 to 600 BC. Chr. During this period they established sea and long-distance trade with all the great empires and neighboring states, especially the Hittite Empire , Egypt, Assyria and Babylonia. Starting from the Levant , the Phoenician city-states established numerous trading posts in large parts of the southern and western Mediterranean. Important export goods included wood , purple and dyed textiles , ivory and ivory objects, as well as food such as B. Wine and Olive Oil . Cedar wood from the Lebanon Mountains was particularly popular . They also acted as intermediate producers, so they processed z. B. imported ore such as tin from the tin islands from ancient Britain or copper from Cyprus and sold the resulting products (bronze) on.

Surname

The name Phoenicians is not a self-designation . The term goes back to the ancient Greeks. It is a collective name for the inhabitants of the Levant. Ethnologically , these inhabitants are probably Canaanites or Arameans . In this context, the Old Testament speaks of Canaanites and the land of Canaan (e.g. Gen 10.15). However, it mainly refers to the southern part of the Levant. The Phoenician city-states shared many cultural features, but did not identify themselves as a unit in the sense of the ancient Greek name. Ancient Phoenician sources assign the inhabitants of the coast to the corresponding city-states. B. by Tyrians, Sidonians and Arwadites.

Of the Romans and the inhabitants of the Phoenician colonies in North Africa were such in the result. B. Carthage , called Poeni ( Punier ).

Greek etymology

The name Phoenicians is derived from the Mycenaean name po-ni-ki-jo ( linear script B ) or the ancient Greek name Φοίνικες (Phoínikes) . This term has been used since Homer and is related to φοίνιξ ( phoínix "purple red"): The dyeing of fabric with the help of purple snails was a typical Phoenician craft . This term could be connected - perhaps folk etymologically - with the Greek adjective φοινός ( phoinós “blood red”), which in turn is derived from φόνος ( phónos “murder”) or φονεῖν ( phoneîn “to kill”).

| Fenchu (Phoenicians) in hieroglyphics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New kingdom |

|

|||||

| or |

Fenchu Fnḫ.w loggers , carpenters, joiners |

|||||

Ancient Egyptian etymology

In ancient Egyptian sources the Phoenicians are mentioned under the name Fenchu . The expression Fenchu was, among other things , in connection with the islands of the Aegean Sea trading with them , the so-called Islands of the Fenchu .

The Egyptian name is derived from fench ("carpenter, carpenter") and refers in particular to the trade in wood that the Phoenicians also carried out with the islands of the Aegean Sea. Egypt imported the cedar growing in Lebanon for shipbuilding. In this context, the nickname "Land of the tree fellers" or "tree felling country" arose. In an inscription , Seti I boasted of having "destroyed the lands (city-states) of the Fenchu".

Language and writing

The Phoenicians spoke a north-west Semitic language that formed a dialect continuum with several other languages of the Levant and that differs only slightly from ancient Hebrew . The language is close to Hebrew , Moabite and Ammonite .

The Phoenician alphabet consists of 22 consonants ( vowels were not notated). Due to the extensive trading activities, the Phoenician alphabet also spread in the Mediterranean area. In the 8th century BC It reached Spain and developed a separate expression in the Punic language of North Africa, starting from Carthage . Phoenician inscriptions are from the 9th to the 3rd century BC. Attested in various Mediterranean regions ( Cyprus , Rhodes , Crete , Malta , Sardinia and Attica ). From the 8th to the end of the 7th century BC Phoenician is also widespread in the Luwian language area in Asia Minor . Different dialects of individual Phoenician cities can be distinguished through inscriptions. Original sources from the Phoenician area are in the 1st millennium BC. BC to around 2nd century BC BC, although numerous, they deal primarily with religious topics. Information on the history or internal organization of the Phoenician city-states is rare. The most plausible reason for the loss of Phoenician literature is the impermanence of most of the writing supports, which are believed to have been made of organic materials. The extent of Phoenician literature is therefore difficult to assess. However, it is likely that it was a very extensive literature. As a result, our current knowledge of Phoenician culture, administration, organization and agriculture is also limited. These areas can only occasionally be traced from external sources.

Phoenician-Punic sources are also rare. The only exceptions are a few Punic sentences in the fifth act of the comedy Poenulus by Plautus and various linguistic monuments in the form of inscriptions, coin finds and fragments by later Roman and Greek authors, such as Augustine and Eusebius . Tradition - z. B. Mago's multi-volume work on agriculture, which has been translated into Latin - allows further insights. A Greek translation of a travelogue from Hanno the Navigator has been preserved .

origin

Ethnologically, the inhabitants of the eastern Mediterranean coast are probably Canaanites or Arameans . Along with the political and ethnic upheavals that u. a. mark the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, characteristic changes in the area of the Phoenicians in writing, language and naming of people can be observed.

In addition to the observations of modern research, there are also ancient text sources that deal with this topic about the origin of the Phoenicians. Examples of this can be found in mythology as well as in ancient historiography: Phoinix , the brother of Kadmos and Europe , is considered the progenitor of the Phoenicians in Greek mythology . According to the histories of Herodotus , the Phoenicians came from the Red Sea and had their origin in the area of the Persian Gulf . In the biblical table of nations the Genesis is Sidon , the ancestor of the Sidonians, the son Canaan (grandchild of the Noach ) denotes ( gene 10.15 LUT ). Canaan is the son of Ham . "Cham" means "red" in Phoenician like the Greek name for the people.

Due to the great heterogeneity of the text genres from which these examples originate, they must be taken into account and interpreted from an individual perspective. Under no circumstances should they be taken literally.

history

Our current knowledge of the history of Phenicia is composed of several, sometimes very different, sources. Original sources from the Phoenician area are in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. BC, although numerous, but these deal primarily with religious topics. Information on the history or internal organization of the Phoenician city-states is rare. To review the historical events during the 1st century BC However, external philological sources can be consulted to reconstruct them. One of the most important sources for the Neo-Assyrian period is the annals of the Assyrian kings. There are also written testimonies from Latin and Greek authors and the Bible. Due to the great heterogeneity of the text genres from which the sources originate, these must be taken into account and interpreted from an individual perspective. Archaeologically, several layers of destruction have been documented for the Neo-Assyrian period, as well as Assyrian ceramic forms and building types. For the Neo-Babylonian and Persian times, the findings from archeology are very sparse. Hardly any find contexts and finds from this period are known, but this could possibly also be a research gap. The beginning of the actual Phoenician story begins at the end of the Late Bronze Age and the beginning of the Early Iron Age. The end of the Late Bronze Age was marked by complex political and ethnic change - often referred to in research as collapse. However, this change is not limited to the Levant, but to the entire Mediterranean area, the Middle East and, in some cases, beyond. Large trading centers along the coast (e.g. Ugarit ) have been destroyed and are losing their political and economic importance. The resulting vacuum is filled by the rise of other settlements. New trading centers such as B. Sidon , Tyros and Byblos . Characteristic changes in the area of the Phoenicians take place in writing, language and naming of persons.

Assyrian dominance (883-669 BC)

The Assyrian ruler Tiglath-pileser I (1114-1076 BC) invaded as early as 1090 BC. BC to the Mediterranean and received tribute payments from Sidon and Byblos . However, this early advance is not comparable to the later influence and supremacy of the Assyrian Empire , during the Assyrian expansion, over the Levant.

With the Neo-Assyrian ruler Assurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) the expansion of the Assyrian Empire began in the west of the Near East , as far as the Phoenician region on the Mediterranean coast. The trading cities of the Levant Coast - u. a. Sidon , Tire , Byblos and Aruad - were obliged to pay tribute to the Assyrian Empire, but remained autonomous beyond that. Such tribute payments are z. B. on stone reliefs from Assurnasirpal II palace in Nimrud . To establish itself in the west, however, six more campaigns under Shalmaneser III (858-824 BC) were necessary. Aramaic principalities - including Aruad, Byblos, Hama and Damascus - continued to oppose Assyrian dominance, making the creation of Assyrian provinces in the west difficult. After these advances, however, the Assyrian efforts slackened. During the reign of Adad-niraris III (810–781 BC) the kingdom of Israel gained strength and often acted as a buffer between the great powers of Egypt and the Assyrian Empire.

The climax of the Assyrian expansion, beginning with Tiglath-pileser III (745–727 BC), can be traced back to about the period from 745 to 632 BC. BC and is probably mainly due to a reform in the administration of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The establishment of a standing army is probably the decisive factor here and military campaigns took place almost annually. These campaigns included conquests, destruction and looting, but also the demand for tribute payments and oaths of loyalty. If the oath was broken or tributes were not paid, punitive actions such as B. Deportations . As before, the Phoenician city-states remained largely autonomous even during the height of the Assyrian expansion. However, the Assyrian attacks had a strong impact on the tributary cities. This led to a change in the organization and structure of the Phoenician city-states. During his first campaign in 733-732 BC. Tiglath-pileser III succeeded in conquering the cities of Dan , Hazor , Bet Sche'an , Rehov , Megiddo , Taanak , Jokne'am and Dor . Samaria was discovered during the Second Campaign, 722–721 BC. BC, conquered. The conquests were followed by the establishment of new Assyrian provinces (Meggido, Samaria, Dor and Gilead ). It was not until Sargon II (721–705 BC) that the northern Levante managed to be annexed and fully integrated into the Assyrian Empire. However, due to alliances between the city-states and kingdoms of the southern Levante and Egypt , Sargon II failed to expand to the south. Sennacherib's (704–681 BC) campaigns in the Levant left considerable damage. Around 701 BC BC Sennacherib's army conquered the cities of Sidon , Sarepta , Akko and Akhziv . Ashkelon and Ekron experienced an economic boom at this time, possibly the production and export of wine and olive oil played an important role. Parallel to the Tiglath-Pileser III, Sennacheribs and Sargons II campaigns and beyond, the Phoenician trading establishments flourished in the western Mediterranean in the period from 733 to 630 BC Chr.

Sennacherib's successor Asarhaddon (681–669 BC) also left his mark along the Levant coast with the establishment of numerous control bases and military bases. He consolidated his control, as mentioned earlier, over oaths taken by Levantine rulers and penalties for breaking oaths. Asarhaddon even managed to penetrate into Egypt and capture Memphis - the capital of Egypt - and hold it for two years. The second conquest of the capital brought with it its destruction. This was followed by the withdrawal of the Assyrian ruler due to unrest in Mesopotamia. The Assyrian control of the Levant was not diminished. Due to the so-called fratricidal war between Asarhaddon's sons, Assurbanipal on the Assyrian throne and Šamaš-šuma-ukin on the Babylonian throne, the Assyrian dominance over the Levant subsided. The Assyrians withdrew completely from Philistia - in what is now Palestine . Thereupon Egypt advanced into this area.

The reasons for the Assyrian expansion to the west and the numerous advances to conquer the Levant were probably primarily economic, not territorial. The creation of provinces and the demand for tribute payments gave the growing empire access to goods and the Mediterranean trade of Phoenician port cities. In summary, it can be said that the Assyrians did not succeed in fully annexing the Levant. The southern Levante and especially the Phoenician city-states remained autonomous. Despite the campaigns and the destruction that they brought with them, the Phoenician trading cities became increasingly prosperous. Factors for this were, among other things, the standardization of units of measurement and ceramic types, which facilitated the cross-regional exchange of goods, as well as the expansion of the sales market to the east.

Chaldean-Babylonian dominance (626-539 BC)

On the retreat of the Assyrian Empire from the Levant in the 7th century BC A short phase followed in which the Phoenician city-states were not under the dominance of larger kingdoms. However, they soon came under Egyptian influence again. It was only under Nabupolassar (626–605 BC) that Mesopotamia's influence on the Levant strengthened again and led to the Babylonian dominance of the area. The course of the change of power or the takeover of the established Assyrian structures in the West is not known.

Nebuchadnezzar (605–562 BC) led several powerful military campaigns along the Levant - including against Egypt around 601 and 568 BC. And Judah, around 597 and 586 BC His army conquered all of southern Syria, the southern Levant as far as Gaza. His aim was evidently, among other things, to bring the smaller kingdoms bordering Egypt under his control. In the course of this, Nebuchadnezzar besieged in 587 BC. The city of Tire - this lasted for 17 years. A year later, 586 BC. The destruction of Jerusalem and the deportation of its inhabitants to Babylonia followed. In northern Israel only a few large places remained intact, including larger centers such as Bethsaida , Dor, and Hazor . The most important cities of the Philistines ( Ashdod , Ashkelon , Gaza and Miqne ) were completely destroyed. The Babylonian dominance over the Levant ended with Nabonidus (555-539 BC).

Persian dominance (539–333 BC)

After the conquest of Babylonia by the Persian ruler Cyrus II (559-530 BC) around 539, the Levant became part of the so-called Transeuphratic administrative unit, a Persian satrapy or province . Sidon or Damascus may have served as the administrative center. At that time the Levant was divided into smaller administrative units. On the one hand, these units differed in their size and their form of administration. The provinces were administered by local or appointed Persian governors, including: Judah , Samaria , Moab, and Ammon . Added to this are the largely autonomous city-states of Sidon, Byblos , Aruad , Tire , Damascus and even the cities of Cyprus . The demand for tributes and oaths of loyalty, the establishment of military bases and way stations, the securing or control of the road and trade network - as in the Neo-Assyrian era - strengthened the dominance of foreign powers in the Levant. In contrast to the neo-Assyrian and neo-Babylonian empires, Cyrus II did not exert any influence on the cultic interests of the local groups. The ethnic groups previously deported to Assyria or Babylonia were also given the opportunity to return to their homeland. Under Darius I (522–486 BC) the first tensions can be seen in the relationship between the Persian Empire and the Greek cities, when Asian Minor and Cypriot cities around 499 BC. BC revolted against the Persian Empire. Around 490 BC The conflict culminated in the defeat of the Persian army at the Battle of Marathon . Although the Phoenician cities did not always exist in peace and harmony with the dominant empire, even under Persian rule, they submitted more readily than to the Assyrians and Babylonians. In contrast, the resistance against Alexander the Great seems to have taken place in 333 BC. Chr. All the more violently. The destruction of Tire by Alexander the Great in 332 BC. And Carthage by the Romans 146 BC. BC meant the end of Phoenician-Punic statehood.

economy

Coinage

The minting of the cities of Aruad , Tire and Sidon began towards the end of the 5th century BC. Initially using the Persian coin standard . After the Macedonian conquest, the Attic standard of coinage (standard of Alexander money) was adopted.

The beginning of the coinage is in Phoenician space a later than in other Mediterranean regions. This is possibly due to the different economic structures of the individual regions and city-states. The Phoenician city-states retained the trade-based economy - which had established itself in the Bronze Age - until the 5th century BC. Chr. At. The first coins from the Phoenician area date to the time of Persian rule over the Phoenician area, during the reign of Cambyses II , around the year 525 BC. It is not yet clear what the reasons for the start of coinage. One possibility discussed in research is the need for a means of payment for the Persian military fleet, which is exclusively manned by Phoenicians. Coins and coinage are also closely related to military activities in other contexts.

purple

The Phoenicians were the first known users of the color purple (a hue between red and purple). The source of this royal color were the purple snails (Latin : Murex : the blunt prickly snail Hexaplex trunculus and the fire horn, Haustellum brandaris ). Due to the complexity of the manufacturing process, the production of the purple colored fabrics could hardly be outweighed by gold. These fabrics were in great demand throughout ancient times and enjoyed great esteem. Homer already sings about the skill of the brightly colored textile work of the Sidonian women. The book of Ezekiel lists purple colors and purple fabrics among the main exports of the city of Tire. Ovid is annoyed with the fashion of the rich Roman elites. Under the Roman emperor Diocletian (301 AD) a maximum price edict of 150,000 denarii was in effect for one pound of double-dyed Tyrian purple silk. For a gram of pure color substance you paid between 10 and 20 grams of gold.

Glass

The manufacture of glass, especially in the cities of Tire and Sidon, was taken over by the Phoenicians from ancient Egypt . The first products can be found in Mesopotamia of the 3rd millennium BC; the technology first made its way to Egypt from there. In the 14th century BC. The presented glassworks and cylinder seals forth stained with cobalt blue and pieces of lapis lazuli so deceptively similar saw that the pharaohs of the Amarna period on supplies were of real lapis lazuli. In the Iron Age, the technique of glass blowing was further developed with the help of local sands and admixtures of metal oxides and minerals to make glass paste for actual mass production. The glass products were popular commodities throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. The Phoenician glass industry was an important branch of the economy and expanded the economic base of the Phoenician city-states in the 7th and 6th centuries BC. During excavations in the whole Mediterranean area, many ointment vessels and amulets were found, which are characterized by their intense colors.

Wood

As a natural resource, the Lebanon cedar , which is ideal for shipbuilding , was instrumental in the rise of the city-states. The 500,000 hectare natural area originally in Lebanon has now shrunk to 2,000 hectares, 342 hectares of which are pure stands, 85 hectares near Tanourinne and Hadem and 40 hectares each near Ain Zahalsa and Jebel Baroun . There is only one old stock of 16 hectares near Bischarri .

The cedars made large thick trunks of very beautiful, durable and easy-to-work wood . This does not twist when drying. Not only the wood hunger of the fleets from 2700 BC. BC until the first millennium AD devoured hectare after hectare. The cedar wood was also popular for palaces and temples in the wide area. The first report comes from the time of Pharaoh Sneferu around 2750 BC. And mentions its delivery of cedar wood from Byblos . But cedar wood was also delivered to Mesopotamia , received around 2400 BC. BC Prince Gudea in Lagasch made many 20 to 30 meter long trunks. The ceiling of the audience hall in Persepolis , which went up in flames when it was conquered by Alexander, was made of Lebanese cedar. When Phenicia was part of the Egyptian Empire, forced laborers carried out large clear cuts for the huge temples of Thebes , Karnak and Memphis . But consumer goods such as the coffins (including those of the pharaohs) were made from the aromatic wood, which was even burned as incense . Even Greece for imported. B. for the temple of Artemis in Ephesus cedar wood from Phenicia, as well as the kings of the Israelites , David and Solomon , for the temple building and their palace buildings. In the Bible alone , the Lebanon cedar is mentioned over a hundred times in 40 chapters in 18 books. In ancient times it was considered the most beautiful tree on earth. In the Temple of Solomon in the Bible pillars, walls, were according to the report Choir , roof construction, the Holy of Holies and the paneling of the altar of cedar. Cedar shingles were used as a roof covering. No wonder that 333 BC BC Alexander the Great found no more cedar wood for shipbuilding in southern Lebanon and was only able to meet his needs in remote areas of anti-Lebanon . In Phenicia, wood was also used to make high-quality furniture and utensils. The resin was also valued and widely used, for example in the embalming of Egyptian mummies.

ivory

An art form that was in no way inferior to bronze and silver work in terms of prestige value was bone and ivory carvings, which continued traditions that went well beyond the year 1200 BC. BC. Also in the Palestinian Megiddo and in the later Phoenician Byblos "Canaanite" ivory works have been found, in which the wealth of forms of the Iron Age is already heralded. The spectrum includes combs, mirror handles, spoons, cassettes and plaques that were attached to valuable furniture as fittings. The Phoenician cities perfected the processing of the noble material that gave it plasticity and softness. With the Phoenician Mediterranean trade, handicrafts with the associated technologies for production spread to the Mediterranean west. As with other artifacts, it is impossible to determine whether the objects were made in the Phoenician cities or by indigenous artisans in locally operated workshops.

Most of the carvings, however, were found in Assyrian Nimrod and Khorsabad. Apparently, Saragon II (721–705 BC) took a large part of the carvings as booty.

Trade between Orient and Occident

However, the Phoenicians ultimately became rich through their trade, based on their colonies and bases and their powerful trade and war fleet made of Lebanon cedar.

seafaring

The Phoenicians were excellent seafarers . They colonized the Mediterranean from Cyprus via Sicily to Spain as well as parts of the Andalusian , Portuguese and North African Atlantic coasts. B. Abdera , Baria , Gadir , Malaka , Sexi , all in the south of the Iberian Peninsula. The Phoenicians had intensive trade relations with the Greeks, but also with Mesopotamia and Egypt . Under Hanno the Navigator , they crossed the Strait of Gibraltar from Carthage and traveled to the Gulf of Guinea . The Azores would also have been visited by the Phoenicians in antiquity, if Carthaginian and Cyrenian coins, which were supposedly found in a broken clay jug by Enrique Flórez on the island of Corvo in the 18th century , were actually brought there by the Phoenicians or Carthaginians.

- Legends

According to popular scientific theories , the Phoenician seafarers found their way across the Atlantic to America two millennia before Christopher Columbus . This is not scientifically proven and also not supported by archaeological finds ( inscription from Parahyba ), but is mostly based on forgeries. It is also possibly a legend that they traded in Britain and bought tin from the pits on the Cornwall peninsula . - Your northernmost proven outpost on the Atlantic Ocean was Abul in Portugal.

shipbuilding

The Phoenician ships through Neo-Assyrian known reliefs from about sargonischer time of Nineveh and Khorsabad , of Balawat from the time of Shalmaneser II. They often have duck heads to Steven , who can look inward or outward. D. Conrad distinguishes three types of ships:

- Coasters with round ribs : They were used to transport loads and were both rowed and sailed. They were also used as river ships on the Euphrates in New Assyrian times .

- Warships had a ram at the bow and a flat hull. Shields are often hung on the railing. They were rowed, but had a detachable mast, the bracket of which sat on the keel.

- Merchant ships had tall stems, often with an animal head. They were rounded, which is why the Greeks later called them gaulos , and were mostly rowed, but later also had sails.

Phoenician ship images are hardly known, exceptions are the seal of Onijahu and a stamp on an amphora handle from Acre , which was found in Area K in 1983. The ship has equally high stems drawn up at both ends, the stern of which ends in a duck's head. A single mast with a lookout ( crow's nest ) and a square sail can be seen. This type of merchant ship was used between the 8th and 6th centuries BC. In use. Square sails came in the 2nd millennium BC. BC, in the 1st millennium BC The ram was invented.

Shipwrecks

Several shipwrecks were found , which on the basis of several indicators - z. B. their cargo or the items that probably ended up on the ship as personal belongings of the crew - were identified as Phoenician ships. The wrecks are widely distributed in different regions of the Mediterranean. Although the term “Phoenicians” is strictly speaking limited to the Iron Age , shipping was an important part of the Levantine economy as early as the Bronze Age . Therefore, Bronze Age shipwrecks, which are likely to have come from the area known as Phenicia , are also presented in the following section .

The oldest, well-preserved and researched shipwreck is the wreck off Ulu Burun on the Turkish coast. The approximately 15 m long ship dates back to the Bronze Age in the 14th century BC. According to the excavator, the ship came from the coast of the south Levante, i.e. from Canaan . The ship was loaded with organic cargo, including pomegranates , figs , nuts , spices , olives , but also with raw materials such as B. Copper in the form of " ox skin bars ". A total of 150 amphorae of the “ Canaanite Jar ” type were recovered, these are occupied on the ship in three different sizes (about 7 l, 15 l and 30 l volume). The vessels with the smallest volume were probably filled exclusively with resin . The other two groups almost all have smaller amounts of resin. Whether they were filled with wine before the ship sank is a controversial topic in research and could not be unconditionally clarified even by chemical content analyzes. In addition, there are valuable items or luxury goods - jewelry , stones , glass objects and ceramics from the Phoenician region, Egypt , Cyprus , the Aegean and Sicily . Whether it is a merchant ship or an exchange of gifts between rulers in the Mediterranean is not clear.

A slightly younger shipwreck - dating back to the late 13th or beginning of the 12th century BC. Dated - is that off Cape Gelidoya also found on the Turkish coast. Due to the strong current, only a single fragment of the ship's wood remained. However, it is believed that it was originally around 10 m long. The cargo received included ox hide bars, scrap metal, small amounts of tin , numerous tools for working metal, stone hammers, anvils and ceramics ( oil lamps and transport vessels ). There are also a scarab and a cylinder seal from the Levant and four other scarabs from Egypt; some of these objects were centuries old by the time the ship was last voyaged. No luxury goods or organic materials could be detected.

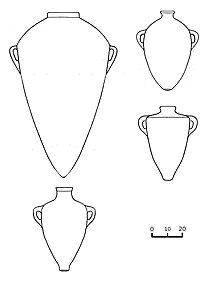

Two Iron Age shipwrecks are the "Elissa" and the "Tanit", which were built in close proximity to each other around 750 BC. Sank off the coast of Gaza. The naming in Elissa and Tanit took place in modern times. The Tanit was originally around 14 m long and it is documented that it contained 385 amphorae as well as ceramics (e.g. saucepans) and other items that are interpreted as belongings of the crew. The length of the Elissa was originally believed to be around 14.5 m; around 396 amphorae and other ceramics in small quantities could be detected.

The ships show strong parallels to each other, so it is believed that they belonged to the same fleet and sank together to the seabed due to a storm. A decisive example is that the amphorae correspond to the same type of ceramic, the so-called " torpedo-shaped jar ". This type of ceramic is typical of the southern Levante, but was also found in Carthage - a Phoenician trading post in North Africa - in the 8th century . What the amphora contained could not yet be fully clarified; there may be wine among the transported goods.

In the western Mediterranean, off the coast of Spain , three other shipwrecks were found, which date back to the 7th or 6th century BC. To date. Among them are the so-called Mazarrón 1 and 2 shipwrecks in close proximity to each other. No cargo in situ could be detected for Mazzarón 1 . The freight from Mazzarón 2 mainly contains products or ceramics from Spain, but also several elephant tusks. It is noteworthy that these tusks bear inscriptions, which are Phoenician personal names. The third shipwreck is located a few kilometers north of the Mazzarón wrecks at Bajo de la Campana . His received cargo includes, among other things, some Phoenician ceramics. However, it is not entirely clear whether these are actually Phoenician shipwrecks.

Phoenician religion

Belief in gods

Due to the rather poor source situation, the religious ideas and practices of the Phoenicians can only be partially reconstructed. In addition to inscriptions and personal names , the Phoenician story of Herennios Philon is an important but also problematic source. The myths contained therein are similar to those of the religion in Ugarit . There the creator and main god El rules over a pantheon , to which deities such as Dagān , Anat and Aschera belonged.

In addition to these ideas common in Syria and Canaan, the religion of the Phoenician city-states is characterized by the veneration of a triad that stood at the head of the respective pantheon. The exact composition of the triad differed from town to town, but it always consisted of a gentleman, a lady and a young son. Despite their different names, the Phoenician gods hardly differed in function and character. They were presented as less individual than the deities of Greek and Roman mythology . This can be seen, for example, in the fact that the deities were often referred to only as Lord ( Ba'al ) and Mistress ( Baalat ). There were anthropomorphic cult images , but here too the universality was emphasized more than the individuality of the deities. As the main god of the most important Phoenician city-state Tire, Melkart ("King of the City") played an important role in the Mediterranean region. He stands for civilization and trade and embodies the overcoming of the natural state by protecting the seafarers and colonists.

| Role in the triad | Byblos | Sidon | Tire |

|---|---|---|---|

| father | El | Baal | Melkart |

| mother | Baalat | Astarte | Astarte |

| son | Adonis | Eschmun |

The Punians, with their center Carthage, also worshiped a Phoenician pantheon, although it differed from that of the mother city of Tire. So Melkart was not the highest god, but probably Baal shamim ("Lord of Heavens"). The most important goddess was Tanit , the consort of Baal-Hammon . Tanit was virgin and mother at the same time, and was responsible for fertility and the protection of the dead. In Carthage she was clearly distinguished from Astarte. Other deities of the Punic religion , which can only be partially reconstructed, were Baal Sapon , Eschmun and Sardus Pater .

Sacrificial cult

From the excavations of the Astarte temple in Kition (Cyprus) in 1962 by the Department of Antiquities, 1328 teeth and animal bones have been analyzed by the archaeozoologist Günter Nobis. They date around 950 BC. BC, about 25 percent were determined by animal species.

The bones of the sacrificed animals were deposited in pits on the temple grounds ( bothroi ). The most common sacrificial animal was the sheep (many lambs), followed by the cattle. Four complete sheep skeletons in the forecourt of Temple 1 are interpreted by Nobis as building victims . Near the altar were 15 cattle skulls, mostly from bulls that were not yet fully grown (under two years of age). The skulls were perhaps also used in the cult, which is indicated by traces of processing on the skulls. Some shoulder blades are notched, perhaps they were used in oracles. Of sheep and cattle, however, the different body parts are present in quite different proportions, so that it can be doubted that whole animals were always sacrificed or remained in the temple area.

The sacrificed donkeys correspond in size to the recent house donkeys . Among the twelve Damhirschresten are also antler fragments, but Nobis does not specify whether it's skull real concerns or antlers - (the importance of fallow deer as a sacrificial animal Dionysus ?) Is so so perhaps overrated. Apart from the antlers, only leg bones are present. The bird bones were not determined by animal species, so that the question of pigeon sacrifices to be expected in an Astarte temple according to the written documents cannot be clarified. There is also a single pig humerus from a sacrificial pit at Temple 4 in the Holy District of Kition .

seal

The seals were used between the 9th and 6th centuries BC. Mostly scarabs , more rarely dice used. They were found not only in Phenicia itself, but also in Greece and the western Mediterranean.

research

Since only a few written sources have survived from the Phoenicians themselves, research is dependent on reports from neighboring peoples. These are above all the Homeric epics , the oldest books in the Bible , Egyptian texts and Greek literature, especially Herodotus . In addition, archaeometallurgy has led to new discoveries in recent times . Archeology is faced with the fundamental difficulty that the Phoenician goods were so popular in the entire Mediterranean area that they were imitated by Greek craftsmen and Greek pottery also had an influence on Phenicia, so that the original and the imitation can often hardly be distinguished.

- The picture of the sources

The oldest layers of the Iliad , which are probably memories of the conditions at the end of the second millennium, speak with great respect of the artful Sidonians. The very name "purple dyers", which also appears in the Iliad, indicates the respect that Sidon showed for the craftsmanship of the purple snail dyers. Mycenaean Greeks came into contact with the Phoenicians early on through their sea expeditions to the Levant.

"... work by women from Sidon, whom he himself, Alexandros the godlike, had brought up from Sidon ..."

So Paris had brought Sidonian weavers to its palace.

Achilles offers a price for victory in the short-distance run at the funeral games in honor of his fallen friend Patroclus :

“… A silver mixing vessel, artful work, could hold six measures, but in terms of beauty it was by far the victory all over the world, because Sidoners, full of artistry, had made it beautifully. But phoinists had brought it with them. '"

Such magnificent cauldrons made of silver and gold were found by archeology from the 7th century. Joachim Latacz points out that these passages in the Iliad point back to an ancient time when the Phoenicians made sea voyages to the northern Aegean , to Lemnos and Thasos , the Silver Island. Memories that go back to the distant days of the Argonaut saga. Thus probably in the Bronze Age of the 2nd millennium.

Around 1050 BC With the beginning of the Iron Age , an Egyptian papyrus, the Wenamun Report , probably a piece of fictional literature, reports how the hegemony of the New Kingdom is crumbling. In a complicated process of capture and trade, the wood required is ultimately delivered from Byblos in return for appropriate consideration and privileges. Research today assumes that this fictional story is a reflection of the situation around 1050 BC. In the Levant.

In the Odyssey, however, a negative Phoenician image is already drawn in some places. The story of the swineherd Eumaios tells of a Phoenician nanny who kidnapped him, a king's son, from the island of Syria . The beautiful Phoenician originally came from Sidon and was stolen by Taphier and Eumaios' father sold. When Phoenician traders came to Syria and stayed there for some time, the nanny let one of the sailors trick her into stealing the king's son Eumaios and bring him on board with the promise to bring her back to Sidon. This was sold by the Phoenicians to Laertes , king of Ithaca and father of Odysseus.

Envy and competition had brought the Greeks to contempt for the Phoenician seafarers. Such a negative reputation can also be found in Canto 14 during Odysseus' stay in Egypt:

“… A man from Phenicia who knew fraudulent things arrived, scoundrel! He had already done a lot of bad things to people! He cleverly chatted me and took me with him until we came to Phoinike, where his property and goods were. "

This phoinist turned out to be a deceiver who, after seven years, wanted to bring Odysseus to Libya and sell him there into slavery. Further negative examples can be found in the Odyssey.

The books of Kings and Chronicles describe how King Solomon of Jerusalem claims to have his temple built. King Hyram of Tire is said to have provided him with gold, cedar wood and other noble materials, builders and craftsmen. In return, Solomon Hiram ceded 20 cities in Galilee . These cities were part of the immediate hinterland of Tire in the north. And probably Tire had already extended his hegemony to the old northern kingdom of Judea. It is a matter of dispute whether these things happened in such an early period or whether the conditions of later centuries were reproduced here.

853 BC A coalition of Syrian and Canaanite small states, including various Phoenician cities, as well as Damascus and Jerusalem opposed the Assyrian army at Qarqar . An Assyrian inscription by Shalmaneser III reports about this . than from a great victory. In fact, however, the Assyrians had to withdraw and leave Syria and Phenicia to the local princes.

The Bible also tells of an alliance between Tire and Jerusalem, which was strengthened by a dynastic marriage between King Ahab of Israel and Jezebel , daughter of Etbaal , king of Tire. During this time the king had succeeded in subjugating the other Phoenician cities, especially Sidon, the ancient enemy and the second most powerful city-state on the Levant. Also Kition in Cyprus Tire became tributary. At this time, towards the end of the 9th century, Tire became the most powerful trading metropolis in the Mediterranean, which was probably only matched by the port of Gaza.

In Ezekiel is that reflected so contradictory:

“The people of Sidon and Arados were your rowers; your wise men who were in you, Tyros, were your helmsmen. "

After the victory of Tiglath Pilesar III. Further Assyrian inscriptions of the conquered cities by the Phoenicians report about the entire area up to Ashurbanipal and are therefore an important source of Phoenician research.

Flavius Josephus tells of the defeat of the Assyrians in the siege of Tire with the help of the Sidon fleet. Finally, Tire was besieged from the land side by Sargon II . However, a senior official reports that the residents continued to go about their business overseas.

The island fortress was also able to hold its own against Sennacherib , although the mainland was probably completely under his control. Despite its military strength, Assyria continued to rely on long-distance trade from the Phoenicians.

The more recent history is also dealt with in the Histories of Herodotus.

Phoenicians and Modern Ethnic Identities

Since the 19th century there have been attempts to trace the origin of the inhabitants of Lebanon , especially those of the Maronites , back to the Phoenicians and thus to differentiate them from both the Arabs and the Jews, cf. Phoenicianism . DNA studies have shown that every 17th inhabitant of the Mediterranean is genetically related to the Phoenicians and that in Lebanon 27% of the population, i.e. about one in four, have this relationship.

See also

literature

- S. Abdelhamid: Phoenician Shipwrecks of the 8 th to the 6 th century BC - Overview and Interim Conclusions, In: R. Pedersen (ed.), On Sea and Ocean: New Research in Phoenician Seafaring. Proceedings of the symposion held in Marburg, June 23–25, 2011 at Archaeological Seminar, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg Contributions to Archeology, 2, 2011.

- ME Aubet: Philistia during the Iron Ages II Period , ML Steiner (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 2014, 706-716.

- AM Bagg: The Assyrians and the Westland: Studies on historical geography and rulership practice in the Levant in the 1st millennium BC , Orientalia Lovaniesana Analecta 216, Leuven 2011.

- GF Bass: Excavating a Bronze Age Shipwreck , Archeology 14/2, 1961, 78-88.

- GF Bass, P. Throckmorton, J. Du Plat Taylor, JB Hennessy, AR Shulman & HG Buchholz: Cape Gelidonya. A Bronze Age Shipwreck, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 57/8, 1967, 1-177.

- D. Ben-Shlomo: Philistia during the Iron Ages II Period, ML Steiner (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 2014, 717-729.

- N. Boulto & C. Heron: Chemical detection of ancient wine . In: PT Nicholson & I. Shaw (eds.), Ancient Egyptian materials and technology, 2000, 599-603.

- Diethelm Conrad: Stamp impression of a ship from Tell el-Fuhhar (Tel Akko). In: Paul Åström , Dietrich Sürenhagen (eds.): Periplus. Festschrift for Hans-Günter Buchholz on his eightieth birthday on December 24, 1999 in Nebuchad. Jonsered, Åström 2000, ISBN 91-7081-101-6 , p. 37 ff.

- R. Giveon: Dating the Cape Gelidonya Shipwreck , Anatolian Studies 35, 1985, 99-101.

- P. Guillaume: Phoenician Coins For Persian Wars: Mercenaries, Anonymity And The First Phoenician Coinage , A. Lemaire, B. Dufour Et F. Pfitzmann (eds), Phéniciens d'Orient et d'Occident. Mélanges Josette Elayi, Paris 2014.

- Arvid Göttlicher: The ships of antiquity. Mann, Berlin 1985; Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, ISBN 3-7861-1419-6 .

- C. Haldane: Direct Evidence for Organic Cargoes in the Late Bronze Age , World Archeology 24/3, 1993, 348-360.

- Gerhard Herm : The Phoenicians - The purple kingdom of antiquity. Econ, Düsseldorf 1980, ISBN 3-430-14452-3 (popular science).

- Asher Kaufman: Reviving Phenicia - in search of identity in Lebanon. Tauris, London / Jerusalem 2004, ISBN 1-86064-982-3

- AE Killbrew: Israel during the Iron Age II Period. In: ML Steiner (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 2014, 730-742.

- G. Lehmann: Trends in the Local Pottery Development of the Late iron Age and Persian Period in Syria and Lebanon, ca.700 to 300 BC , Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 311, 1998, 7.

- O. Lipschitz: Ammon in Transition from Vassal Kingdom to Babylonian Province , Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 335, 2004, 37-52.

- G. Markoe: Phoenicians. Peoples of the Past , Berkeley 2000.

- Glenn E. Markoe: The Phoenicians . Translated by Tanja Ohlsen. From the series: Völker der Antike, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-8062-1816-1 .

- P. McGovern: Charting a Future Course for Organic Residue Analysis in Archeology, J Archaeol Method Theory, 2015, doi : 10.1007 / s10816-015-9253-z

- Sabatino Moscati : The Phoenicians. From 1200 BC Until the fall of Carthage. Magnus, Essen 1975.

- Sabatino Moscati: The Phoenicians (= exhibition catalog Palazzo Grassi. Istituto di Cultura di Palazzo Grassi [Venezia]). Bompiani, Milan 1988.

- Hans-Peter Müller : Religions on the Edge of the Greco-Roman World. Phoenicians and Punians. In: Hans-Peter Müller, Folker Siegert: Ancient marginal societies and marginal groups in the eastern Mediterranean (= Münster Judaic Studies. Vol. 5). Münster 2000, ISBN 3-8258-4189-8 , pp. 9-28.

- Günter Nobis: Animal remains from the Phoenician Kition. In: Periplus. Festschrift for Hans-Günter Buchholz on his eightieth birthday on December 24, 1999. Edited by Paul Åström and Dietrich Sürenhagen. Jonsered, Åström 2000, ISBN 91-7081-101-6 , pp. 121-134.

- C. Pulak: Discovering a royal ship from the age of King Tut: Uluburun , Turkey. In GF Bass (ed.), Beneath the seven seas: Adventures with the Institute of Nautical Archeology, 2005, 34-47.

- Wolfgang Röllig : Phoenicians and Greeks in the Mediterranean . In: Helga Breuninger, Rolf Peter Sieferle (eds.): Market and power in history . Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-421-05014-7 , pp. 45–73 ( archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de [PDF; 11.5 MB ; accessed on February 22, 2016]).

- TJ Schneider, Mesopotamia (Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Levant. In: ML Steiner (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 2014, 98-106.

- Michael Sommer : The Phoenicians. Merchants between Orient and Occident (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 454). Kröner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-520-45401-7 ( review ).

- Michael Sommer: The Phoenicians. History and culture (= Beck knowledge: Beck'sche Reihe. Vol. 2444). Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-406-56244-2 .

- E. Stern: Archeology in the Land of the Bible: Vol. 2. The Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian Periods, 732-332 BCE , New York 2001.

- B. Stern, C. Heron, T. Tellefsen, & M. Serpico: New investigations into the Uluburun resin cargo , Journal of Archaeological Science 35, 2008, 2188-2203.

- Werner Huss : Carthage. Beck, Munich 1995 / 4th, revised edition, Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-406-39825-1 .

- W. Weißer, The Owls of Cyrus the Younger: on the first coin portraits of living people , ZPE 76, 1989, 267–279.

- JR Zorn: The Levant during the Babylonian Period , ML Steiner (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 2014, 825-840.

- The Phoenicians. From trading people to great power. In: EPOC. No. 4, Heidelberg 2009, ISSN 1865-5718 , pp. 8-45.

Web links

- Phenicia (English)

- The Phoenicians and their cultural achievements

- ZDF documentary The History of the Phoenicians: Rise and Fall of a Great Power on YouTube (43:37 min.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Wolfgang Röllig: Phoenicians, Phönizien . In: Otto Edzard, Michael P. Streck (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie . tape 10 , 2005, pp. 526-537 .

- ^ Propylaea world history. Volume 2: Advanced Cultures of Central and Eastern Asia . Propylaea, Berlin / Frankfurt / Vienna 1962, p. 95.

- ^ Assaf Yasur-Landau: The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 0-521-19162-9 , pp. 41 ( books.google.com ).

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The memorial stone Sethos 'I for the chapel Ramses' I in Abydos . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1965, p. 85.

- ^ Oswald Spengler mentions the name Fenchu .

- ↑ Siegfried Schott: The memorial stone Sethos 'I for the chapel Ramses' I in Abydos. P. 20 f.

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Röllig: Phoenicians, Phenicia . In: Otto Edzard, Michael P. Streck (Hrsg.): Reallexikon der Assyriologie . tape 10 , 2005, pp. 358 .

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1,1

- ↑ a b c A. M. Bagg: The Assyrians and the Westland: Studies on the historical geography and rule practice in the Levant in the 1st millennium BC In: Orientalia Lovaniesana Analecta . tape 216 , 2011.

- ^ G. Markoe: Phoenicians. Peoples of the Past . Berkeley 2000.

- ^ TJ Schneider: Mesopotamia (Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2011, p. 100 .

- ^ A b c A. E. Killbrew: Israel during the Iron Age II Period . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE, 730-742 . 2014, p. 737-738 .

- ↑ a b c D. Ben-Shlomo: Philistia during the Iron Ages II Period . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 719 .

- ^ TJ Schneider: Mesopotamia (Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 101-102 .

- ^ E. Stern: Archeology in the Land of the Bible: Vol. 2. The Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian Periods, 732-332 BCE . 2001, p. 228 .

- ^ TJ Schneider: Mesopotamia (Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 103 .

- ↑ ME Aubet: Philistia during the Iron Ages II period . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 714 .

- ↑ G. Lehmann: Trends in the Local Pottery Development of the Late Iron Age and Persian Period in Syria and Lebanon, ca.700 to 300 BC In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research . tape 311 .

- ↑ JR Zorn: The Levant during the Babylonian Period . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 837 .

- ↑ JR Zorn: The Levant during the Babylonian Period . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 831 .

- ^ O. Lipschitz: Ammon in Transition from Vassal Kingdom to Babylonian Province . In: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research . tape 335 , 2004, pp. 39 .

- ^ TJ Schneider: Mesopotamia (Assyrians and Babylonians) and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 834 .

- ↑ J. Elayi: Achemenid Persia and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 111-112 .

- ↑ J. Elayi: Achemenid Persia and the Levant . In: ML Steiner (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of the Archeology of the Levant: C. 8000-332 BCE . 2014, p. 114 .

- ^ E. Stern: Archeology in the Land of the Bible: The Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian Periods, 732-332 BCE . tape 2 , 2001, p. 353 .

- ^ E. Stern: Archeology in the Land of the Bible: The Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian Periods, 732-332 BCE . tape 2 , 2001, p. 354 .

- ^ Eva Szaivert, Wolfgang Szaivert, David R Sear: Greek coin catalog. Volume 2: Asia and Africa. Battenberg, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-87045-187-4 , p. 275.

- ^ A b P. Guillaume: Phoenician Coins For Persian Wars: Mercenaries, Anonymity And The First Phoenician Coinage . In: A. Lemaire et al. (Ed.): Phéniciens d'Orient et d'Occident . Paris 2014, p. 225-227 .

- ↑ W. Weißer: The Owls of Cyrus the Younger: to the first coin portraits of living people . In: ZPE . No. 76 , 1989, pp. 273 .

- ↑ Gerhard Herm: The Phoenicians. The purple kingdom of antiquity. Econ, Munich 1985, ISBN 3-430-14452-3 , pp. 83-86.

- ↑ Drawing based on Fig. 2 from D. Regev: The Phoenian Transport Amphora . In: J. Eiring and J. Lund: Transport Amphorae and Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean , 2004, pp. 337-352.

- ^ Roger Collins: Spain. (= Oxford Archaeological Guides. ). University Press, Oxford 1998, ISBN 0-19-285300-7 , p. 262.

- ↑ Critical remarks on this find already in Alexander von Humboldt : Critical studies on the historical development of geographical knowledge of the New World and the progress of nautical astronomy in the 15th and 16th centuries. Volume 1, Berlin 1836, pp. 455ff ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Frank M. Cross: The Phoenician Inscription from Brazil. A Nineteenth-Century Forgery. In: Orientalia Romana No. 37, Rome 1968, pp. 437-460.

- ^ D. Conrad: Stamp impression of a ship from Tell el-Fuhhar (Tel Akko) . In: Paul Åström, Dietrich Sürenhagen (eds.): Periplus. Festschrift for Hans-Günter Buchholz on his eightieth birthday on December 24, 1999 . 2000.

- ↑ C. Pulak: Discovering a royal ship from the age of King Tut: Uluburun, Turkey . In: GF Bass (Ed.): Beneath the seven seas: Adventures with the Institute of Nautical Archeology . 2005, p. 42-44 .

- ^ C. Haldane: Direct Evidence for Organic Cargoes in the Late Bronze Age . In: World Archeology . tape 24 , no. 3 , 1993.

- ^ Patrick E. McGovern, Gretchen R. Hall: Charting a Future Course for Organic Residue Analysis in Archeology . In: Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory . tape 23 , no. 2 , June 1, 2016, ISSN 1072-5369 , p. 592-622 , doi : 10.1007 / s10816-015-9253-z .

- ^ B. Stern, C. Heron, T. Tellefsen, & M. Serpico: New investigations into the Uluburun resin cargo . In: Journal of Archaeological Science . tape 35 .

- ↑ N. Boulton & C. Heron: Chemical detection of ancient wine . In: PT Nicholson & I. Shaw (Eds.): Ancient Egyptian materials and technology . 2000.

- ↑ Serena Sabatini: Revisiting Late Bronze Age oxhide ingots. Meanings, questions and perspectives. In: Ole Christian Aslaksen (Ed.): Local and global perspectives on mobility in the Eastern Mediterranaean (= Papers and Monographs from the Norwegian Institute at Athens, Volume 5). The Norwegian Institute at Athens, Athens 2016, p. 35 f. (with further documents)

- ↑ GF Bass: Excavating a Bronze Age Shipwreck . In: Archeology . tape 14 , no. 2 , 1961, p. 78-88 .

- ^ GF Bass, P. Throckmorton, J. Du Plat Taylor, JB Hennessy, AR Shulman & HG Buchholz: Cape Gelidonya. A Bronze Age Shipwreck . In: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society . tape 57 , no. 8 , 1967, p. 1-177 .

- ^ R. Giveon: Dating the Cape Gelidonya Shipwreck . In: Anatolian Studies . tape 35 , 1985, pp. 99-101 .

- ↑ a b S. Abdelhamid: Phoenician Shipwrecks of the 8th to the 6th century BC - Overview and Interim Conclusions . In: R. Pedersen (Hrsg.): Marburg contributions to archeology . tape 2 , 2011.

- ↑ M. Sommer: The Phoenicians. History and culture. Munich 2008, p. 101f.

- ↑ a b c M. Sommer: The Phoenicians. History and culture. Munich 2008, p. 103.

- ↑ a b M. Sommer: The Phoenicians. History and culture. Munich 2008, p. 103f.

- ^ W. Huss: Carthage. Munich 2008, p. 100f.

- ^ W. Huss: Carthage. Munich 2008, p. 102.

- ↑ Homer, Odyssey 15, 402-484.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Pierre Zalloua (University of Beirut) at: epoc.de News: Phoenicians. The love of the sailors . dated October 30, 2008 and according to EPOC. No. 4, 2009, p. 27.