Commandery Tempelhof

The Commandery Tempelhof was a Coming of the Knights Templar on the Teltow in the southern advance of Berlin , she played an important role in its creation. It was founded in 1200 and included the villages Tempelhof , Mariendorf and Marienfelde and a court later Rixdorf and Vorwerk in Treptow . The center of this coming was the castle-like Komturhof in Tempelhof, in the middle of which stood the Commandery Church, which also served as the village church and has been preserved to this day as the Tempelhof village church despite severe war damage.

After the dissolution of the Templar Order in 1312, the Tempelhof Commandery was transferred to the Knights of St. John in 1318 , who sold the property rights to the cities of Berlin - Cölln in 1435 , but retained fiefdom . Only after the secularization of the order by the October edict of 1810 did the property complex become fully private property . The main building of the Komturhof, which was converted into a manor in 1598, served as Tempelhof's local office building from 1863 until it was demolished around 1890 .

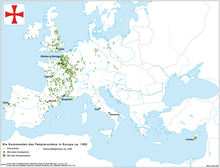

Until 1312 the Commandery Tempelhof belonged to the Templar order province of Alemania et Slauia (led by an order preceptor ), then to the Johanniter- Ballei Brandenburg, which had a special status within its order province due to its relatively high degree of independence.

Location of the Komturhof

As part of the high medieval eastward expansion of Ostsiedlung the Knights Templar on the central High was Teltow probably around 1200, at the latest in 1210, a property complex of about 200 in a hitherto largely uninhabited forest hooves given. The villages Tempelhof ( Tempelhove ), Mariendorf ( Margendorpe ) and Marienfelde ( Marghenvelde ) were created from wild roots on it. The Komturhof was on the southern outskirts of Tempelhof. The Tempelhof district initially extended to the banks of the Spree across from Stralau , where a Vorwerk was built. Halfway along the connecting path between the Vorwerk in Treptow and the Komturhof in Tempelhof was a farm that was converted into a village in 1360 and was given the name Rixdorf ( Richardsdorp ).

The Komturhof was outside the village, in a strikingly protected altitude between what were originally four lakes. Only two of them are left today in the Alten Park and in the Lehnepark ; the pond under today's Reinhardtplatz was filled in and filled up in favor of a market area. The Tempelhof village church still marks the center of the Komturhof as a former commandery church.

The settlement complex with the villages of Tempelhof, Mariendorf, Marienfelde and Rixdorf was, with around 200 hooves, significantly smaller than the other properties of the Knights Templar in the Mark Brandenburg: Lietzen , Zielenzig and Soldin have 250 to 300 hooves, the exceptional case Quartschen even 1000 hooves. With the exception of Lietzen, they were all in Neumark . For these branches it is clearly documented which princes the Knights Templar appointed as owners.

Foundation of the Commandery by the Knights Templar

First documentary mentions

However, it is disputed who brought the Knights Templar to the Teltow: the Ascanian Margraves of Brandenburg , the Wettin Margraves of Meissen , the Archbishops of Magdeburg , the Dukes of Silesia or the Dukes of Pomerania . Information can be obtained from the strategic location of the villages on the Teltow (see below). There is no document indicating that the villages of Tempelhof, Mariendorf, Marienfelde and Rixdorf were founded or owned by the Knights Templar; in particular, there is no document that the Knights Templar issued in or for Tempelhof. That they were the founders of these settlements can only be deduced from inferences. An Order of ownership is only for the Johanniter detectable than this in 1435 sold the four villages to the city of Berlin. In 1344 a Johannite commander is mentioned for the first time with express reference to Tempelhof: Burchard von Arenholz as "commendator in Tempelhoff" .

However, it is a fact that the Knights Templar was abolished in 1312 by Pope Clement V and its property was transferred to the Order of St. John. Apparently the Tempelhof knights initially resisted and were therefore initially subordinate to a procurator of Margrave Waldemar . The transfer to the Johanniter was not legally completed until 1318.

Magister Hermannus de Templo (1247)

The first mention of Tempelhof (not unambiguous) is a document that was issued in 1247 in the Walkenried monastery , with which the Bishop of Brandenburg transferred the tithe of 100 hooves to this monastery in the Uckermark . Among the documentary witnesses there is a “magister Hermannus de Templo” , but this document only proves that there was a man named “Hermann von Templo” in 1247 , who was worthy to act as a documentary witness due to his rank as a “magister” .

The addition of "templarius" (Templar, Knights Templar) or "de Templo" (from the temple, from the Templar order) usually denotes a member of the Templar order. It is also not uncommon for a commander to be referred to as “ magister ” .

The other witnesses are the abbots of the monasteries Zinna and Lehnin , the well-known provost Symeon from Cölln , pastor Heinrich von Oderberg , Johannes von Werneuchen and several clergymen from the Walkenried monastery. In the confirmation document of the Brandenburg Cathedral Monastery of the same day, two mayors ( Schulzen ) also appear as witnesses: Werner von Stettin and Marsilius von Berlin. A commander of the Knights Templar ( magister de Templo ) in the group of documentary witnesses, who mainly come from the Central Markets, fits best with the Komturhof on the Teltow.

Knight Jacobus of Nybede (1290)

Tempelhof is mentioned as a place in 1290, but also indirectly: The knight Jacob von Nybede gives the Franciscan monastery church in Berlin a brick barn for their building materials, which is between Tempelhof and Berlin ( dye tygelschüne, dy de lyt twuschen Tempelhoffe and Berlin ), namely probably on Kreuzberg , as indicated by archaeological finds from the 1830s. Jacobus is not a Knight Templar. He may be the owner of the Ritterhufen, later known as Hahnehof; the courtyard was located on today's corner plot of Alt-Tempelhof / Tempelhofer Damm, with an allegedly archaeologically proven tower foundation.

Evaluation of the written sources

Since the village is called "Tempelhof" in 1290 and in 1435 with its neighboring villages is owned by the Johanniter, who generally took over the Templar ownership in the Mark Brandenburg in 1318, research unanimously assumes that this settlement complex was founded by the Knights Templar. Apparently the village, at least the Komturhof, already existed in 1247; In any case, that is the most convincing classification of Master Hermann von Templo.

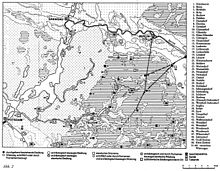

Strategic location of the Templar villages on the Hohe Teltow

So far, traces of Slavic pre-settlement have not been found either in Tempelhof or on the Knights Templar property complex. This confirms the assumption that the Teltow plateau was forested and unpopulated away from bodies of water such as the Bäke , because it represented a borderline no man's land between the tribal areas of the Heveller (center: Brandenburg an der Havel ) and the Sprewanen (center: Köpenick ).

It is undisputed that the villages are like a locking bolt over the Teltow. The eastern border of the districts of Tempelhof, Mariendorf and Marienfelde runs almost dead straight from north to south. In view of the competition between the aforementioned princes for supremacy on the Teltow and Barnim, there is agreement that, as in similar cases, one of the great religious orders was settled here in order to create a buffer-like border guard.

If you only look at the eastern district boundaries, this line can be continued via Birkholz to Diedersdorf . But if you have more aspects of settlement history in mind, you will notice that the village church in Heinersdorf also had the ship-wide transverse west tower typical for this settlement phase at the beginning of the 13th century, as can otherwise only be found in Marienfelde, Mariendorf and in the first building of Tempelhof ; Heinersdorf, however, had no apse .

If one continues the line of the villages in reverse to the north, it is aimed precisely at the Spreepass between Cölln and Berlin, where the Margrave on Mühlendamm had a plot of land that was later used as a mill yard and later as a mint . Close to Mühlendamm is the Nikolaikirche , for which the Knights Templar's right of patronage is mentioned in 1288 . Cases are known in which the sovereigns have withdrawn the property originally granted for border protection purposes; In many such cases, the orders were compensated with the right of patronage over the city parish church. It could therefore be that the Mühlenhof property was initially used as a bridgehead for a fortification by the Knights Templar, who also had to cover the Spreepass at Mühlendamm as part of their military protective function. However, this is only a speculation, albeit conclusive.

Another indication is that an apparently "fortified house" on the eastern part of the Tempelhof district belonged to the property complex of the order, which was separated in 1360 and became the newly founded " Richardsdorf ". If you extend the line from Tempelhof via Rixdorf to the Spreepass of Stralau , where a ford to the Slavic castle wall on the Stralau peninsula has been known since the Slavic era, you come across a forework of the Knights Templar in Treptow , mentioned at the end of the 13th century was referred to as "Burgwall" in the 19th century.

With the connecting lines Marienfelde – Mühlendamm or Marienfelde – Treptow, you can block the entire Hohe Teltow and at the same time control the accesses to the two most important Spree passes. Since the continuous linear boundary of the district lies on the eastern side of these villages, it is obvious that their "front" was directed against the eastern Teltow, i.e. against the dukes of Silesia and the margraves of Meissen . They are therefore not commissioned by the Knights Templar, especially since the Templars did not belong to the archdeaconate of Köpenick - Mittenwalde , like the neighboring villages of Britz and Rudow , but to Sedes Spandau .

The influence of the dukes of Pomerania is only vaguely comprehensible in a retrospective note in the Märkische Fürstenchronik dated 1280 . This influence presumably only consisted of a legal claim that was never further specified; Pomeranian settlement activity is not to be found either on the Barnim or even on the Teltow. Only the Margraves of Brandenburg and the Archbishops of Magdeburg remain as clients. The “Magdeburg hypothesis”, which only emerged in 1982, is highly controversial and has meanwhile been rejected by the majority.

The donation to the Knights Templar, by whomever, served several purposes:

- The donation to an important religious order should be beneficial for the salvation of the donor.

- The "locking bar" or "buffer" on the Teltow between the competing princes reduced the risk of losing territory.

- As the landlord, the Knights Templar took part in the expansion of the country (clearing, growing grain) and thereby increased the sovereign's income through taxes.

- Even without a special mandate, the Knights Templar was conducive to the Christianization of the previously Slavic areas.

The view that the Templar Order was set up as a fighting force against the Slavs is erroneous . Since 1200 at the latest, there have been no more reports of Slavic attacks, the military strength of which had in principle been broken since the Wendenkreuzzug in 1147. The of Margrave Albrecht II. (Brandenburg) in the Brandenburg tithe dispute against Pope Innocent III. The reason given that he kept the church tithe for himself in order to be able to finance the fight against the pagans is considered a protective claim in research.

Relations of the margraves to the Templar Order and its task

In contrast, all attempts in research to find out for the client which princes had the best (or supposedly worst) relationships with the Knights Templar remain in vain . The Knights Templar are, like the Cistercians , whose most important abbot Bernhard von Clairvaux exerted significant influence on the rule of the Templars, internationally active religious orders . That was also the reason for using them as border guards : Nobody would dare to attack the property of the most powerful and influential orders. That is why the crew of the commanderies did not have to consist of warriors capable of armed weapons, but only of invalids who, through skillful administration of the donated lands, ensured that good earnings improved the war chests of the Knights Templar.

The view that the Knights Templar were called into the country to repel attacks by the Slavs is also wrong for this reason. The last written reports about battles with pagan Slavs (who are often ruled by princes who have already converted to Christianity) date from around 1180. Later reports relate exclusively to battles between the conquering Christian princes. In 1187 and 1210, the Ascanians assert to the papal church that the Slavic threat was still ongoing, in order to justify the use of the church tithe for war expenditure. However, the majority of research assumes that these were only protective claims.

In the second half of the 12th century every prince who valued a great reputation and who could afford it financially visited the Holy Land , as did the Brandenburg margraves Otto II (as a pilgrim) and Albrecht II (as a crusader) even her grandfather Albrecht the Bear and his wife. Contacts with the Knights Templar can therefore be proven by all of the royal houses competing on the Teltow . Even the assumption that the loss of Jerusalem in 1187 could have given rise to land donations to the Knights Templar in order to make the reconquest possible can only be speculation. The Cistercian Order, which received land donations even more often than the Templars with the intention of protecting the border, received them for longer periods of time without current political reasons and certainly not with the commission of military activity.

Date of settlement of the Knights Templar

The western Teltow was developed as part of the "Central Markian Plan Settlement" of the Ascanian margraves around the years 1190-1230, in a two-phase cycle (first restructuring of existing Slavic settlements, then new early German villages), in several chain-like rows of villages parallel to Valley of the Bäke. The regularity of the overall network indicates that the Templar villages were part of the settlement concept from the start. Its foundation should therefore be around or shortly after 1190, possibly in time steps, but probably beginning with the Komturhof as the center. Since the later Margrave Albrecht II (1205–1220) attended the founding meeting of the Teutonic Order in Acre in 1198 , he would probably have given this priority; therefore the Templars were probably settled before 1198.

The legend of the "underground passage" of the Knights Templar

A curiosity is the legend of the "underground passage of the Knights Templar", which can be grasped in 1878 at the latest. Brecht reports that the royal builder Mr. K. Marggraff reported that after the "sparse documented reports and the few local traces and traditions [!] ... traces of the entrance walling [of the Komturhof] are still present decades ago and from the substructure of the waiting tower that still exists in the current jug house, which is now walled underground passage would have been accessible. "

The “underground corridor” is a frequent stereotype in the often problematic local history ideas about the village churches. As early as the 1920s and 1930s, on the occasion of the construction of the subway to Tempelhof, it was found that at the level of the "Krughaus" its cellar vault and a drainage canal from the old road to Mariendorf had been cut, but no underground passage to the village church. On the occasion of the reconstruction of the war-torn church and the previous archaeological investigation, the search for this passage was given new impetus, as a special file in the Tempelhof home archive shows. The excavator had to report in detail to the Tempelhof civil engineering department ; to his regret, he had not found an entrance to the underground passage in the church area. A large number of contemporary witnesses came forward, mostly citing other contemporary witnesses who had since died.

It turned out that there are three versions of the underground corridor: the "classic" one from the church to the village pitcher with the former "guard tower of the Vorwerk" (to the northeast), a second from the church (to the southeast) to a barred entrance in the Theodor-Francke-Park, which, however, closed an ice cellar , and a third: from the church in the direction of Schönburgstrasse (west) to cover three completely different cardinal points. The teacher Hoffmann and the sexton had entered the latter corridor around 1880, but soon had to turn back because of the stifling air after they could see the corridor being more than ten meters long. The teacher had written a brochure about this, of which he had sent deposit copies to the State Library and the National History Association. In 1952, the Tempelhof district office officially inquired about this with the two institutions; both reported no reports. Any conceivable war loss is excluded because the inventory catalogs have been preserved, but no Tempelhof author Hoffmann is recorded in them. Obviously, the gist of the rumor is that Dr. C. Brecht was published in 1878 in the writings of the Verein für die Geschichte der Stadt Berlin; But Brecht describes variant 1, without reference to the teacher and sexton.

The Commandery under the Hospitallers

The Knights Templar was 1307 followed in France by King Philip IV., And on the Council of Vienne in 1312, the Order by Pope was Clement V disbanded. On June 22, 1312, the Pope called on the Bishop of Brandenburg, the Knights Templar in the distant Mark Brandenburg to obedience to their Archbishop Burchard III. von Magdeburg , whose arrest attempts they had resisted. It was only with the Treaty of Kremmen of January 29, 1318, when the Knights of St. John bought the Templars withheld by the margravial bailiff , including Tempelhof, with all pertinent services (accessories to property in the form of rights and property) against payment of 1,250 marks for the appointment of margrave Woldemars were handed over to the patron and trustee of the interests of the Johanniter, the transition of the Templar property into the possession of the Johanniter could finally be realized.

In 1344 a Johannite commander is mentioned for the first time with express reference to Tempelhof: Burchard von Arenholz as "commendator in Tempelhoff". A document about the sale of interest rights in Marienfelde to the Berlin councilor family Reiche in 1356 shows that there must have been a convent of friars in Tempelhof , which was presided over by a prior in spiritual matters .

On the advice of the priest Jakob von Datz, the court between Tempelhof and Treptow was spun off as Richardsdorf by Komtur Dietrich von Zastrow from the Tempelhof district in 1360 , but without its own church. It is the only document of a medieval village foundation in the Mark Brandenburg. More details about the property complex of the Johanniter villages Tempelhof, Mariendorf, Marienfelde and Rixdorf (hoof ownership, rights, duties and services) can be found for the first time from the land book of Charles IV.

| Surname | mentioned in the year |

|---|---|

| Burchard of Arenholz | 1344 |

| Ulrich von Königsmarck | 1358 |

| Dietrich von Zastrow | 1360 |

| Heinrich von Duseke | 1376 |

| Heinrich von Ratzenberg | 1432 |

| Colditz nickel | 1435 |

In 1344 Arnold von Teltow is mentioned as prior, in 1360 Jakob von Datz as priest.

Sale of the Commandery to the cities of Berlin / Cölln and further changes of ownership

On August 24, 1435, the so-called Tempelhof feud occurred because of a border dispute on a lowland on today's Landwehr Canal . Allegedly, citizens of the twin cities of Berlin-Cölln had arbitrarily moved boundary stones there. With four village groups of infantry and 300 knights under the leadership of Commander Nickel von Colditz, the Johanniter then tried to attack the violators, but suffered a heavy defeat at the gates of the city. A few weeks later under the master master Balthasar von Schlieben on 23/26. September 1435 the entire order property was sold to the victorious cities for the huge sum of 2440 shock Prague groschen as a combing village as a perpetual fief, in order to finance the acquisition of the castle, city and country Schwiebus for the order.

The Komturhof and the Hahnehof were still sold by the twin towns to individual citizens in 1435. The further development of the history of ownership is complicated because it must be taken into account what the sold rights relate to (districts, farms, patronage rights , etc., separated by villages) and because the farms changed their bourgeois owners several times. In 1598 they were acquired by the electoral councilor and lawyer Johann Köppen and combined into a manor. About three years later, the complex passed into the possession of the Electress Katharina . The planned expansion of the Komturhof to the first electoral summer residence , however, got stuck in the beginning. After the Electress's death, the city of Cölln bought the former Kommende back in 1604. Around 1630 it came into the private possession of the then Johanniter master craftsman, Count Adam von Schwarzenberg .

Troops passing through devastated the court in the Thirty Years' War. In 1660, Schwarzenberg's heirs sold the estate to the Great Elector , who transferred the court to his wife Luise Henriette . In 1688 the court was again in noble private ownership when Elector Friedrich III. exchanged for hereditary property near Wesel of the court preacher Christian Cochius , who was called to Berlin .

By edict of October 30, 1810 and a document of January 23, 1811, the order was then secularized as part of the Prussian reforms . This meant that the owner of the fiefdom at that time, Prince Otto Hermann von Schönburg , was also given ownership of the farm in 1816. The estate changed hands several times until the banker Friedrich Carl Heinrich Ferdinand Jacques finally had the Feldmark parceled out after 1863.

aftermath

The district council of Berlin-Tempelhof decided in 1957 a heraldically correct district coat of arms using the Templar cross (based on several designs), in contrast to the eight-pointed Johanniter cross, which is in the district coat of arms of Neukölln (originated from the Johanniterdorf Rixdorf). The Templar Cross has been part of the new coat of arms of the Tempelhof-Schöneberg district since 2001.

The Kreuzberg (named after the Iron Cross , not after the Templar Cross) was previously called Templower Berg, because the area from Tempelhof originally extended to the Landwehr Canal . In Kreuzberg there are therefore Tempelherrenstrasse, Johanniterstrasse and Am Johannistische Strasse. In Tempelhof there is the Templerzeile, the Ordensmeisterstraße, the Komturstraße, the Colditzstraße, the Volkmarstraße and the Werbergstraße. Colditzstrasse is reminiscent of the Johanniterkomtur Nickel von Colditz, Volkmarstrasse of a Komtur with no sources; Hermann von Werberg was the Johannite governor of the Mark in Brandenburg and the Wendland and signed the deed of foundation of the village for Rixdorf in 1360 .

literature

- Carl Brecht: The village of Tempelhof. In: Writings of the Association for the History of the City of Berlin. Berlin 1878, booklet XV, p. 3ff.

- Oskar Liebchen: The beginnings of settlements in the Teltow and in the Ostzauche. In: Research on Brandenburg and Prussian history. Volume 53, 1941, pp. 211-247.

- Johannes Schultze : The age of the Tempelhof. In: The Bear of Berlin. Volume 4, 1954, pp. 89-99.

- Wolfgang H. Fritze : The advance of German rule in Teltow and Barnim. In: Yearbook for Brandenburg State History. Volume 22, Berlin 1971, pp. 81-154.

- Walter Kuhn : Church settlement as border guard 1200 to 1250 (using the example of the central Oder region). In: Walter Kuhn: Comparative studies on the medieval eastern settlement. Cologne and Vienna 1973, pp. 369–417.

- Adriaan von Müller : nobleman, citizen, farmer, beggar man. Berlin in the Middle Ages. Berlin 1979.

- Wolfgang H. Fritze: The early settlement of the Bäketal and the history of Berlin. In: Yearbook for Brandenburg State History. Volume 36, Berlin 1985, pp. 7-41.

- Wolfgang H. Fritze: founding city Berlin. The beginnings of Berlin-Cölln as a research problem. Edited, edited and supplemented by an addendum by Winfried Schich. Berlin 2000.

- Heiko Metz: Hermannus de Templo and Tempelhof. An investigation into the first mention of the village of the same name on the Teltow. In: Bulletin of the State Historical Association for the Mark Brandenburg. Volume 102, 2001, No. 3, pp. 73–87.

- Ulrich Waack: The early power relations in the Berlin area. A new interim balance sheet of the discussion about the “Magdeburg Hypothesis”. In: Yearbook for Brandenburg State History. Volume 56, 2005, pp. 7-38.

- Heinz-Dieter Heimann , Klaus Neitmann , Winfried Schich (eds.): Brandenburg monastery book. Handbook of the monasteries, pens and commander by the mid-16th century. 2 volumes. Berlin 2007.

Web links

- Ev. Parish Alt-Tempelhof

- Entries in the Berlin State Monument List:

Individual evidence

- ↑ Schultze (see Lit.) pp. 92, 97

- ↑ During the archaeological investigation of the ruins of the Tempelhof village church in 1952 by Ernst Heinrich (see lit.), two Slavic temple rings were found. Amazingly, Heinrich did not publish this find in 1954 (Brandenburgisches Klosterbuch 2007, Vol. 2, pp. 1275, 1284).

- ↑ A similar, elevated peripheral location to the village center, protected by a lake, can also be found in Britz .

- ↑ In particular, Polish dukes and the Bishop of Lebus

- ↑ See Lit. Fritze (Teltow) and Waack

- ↑ Metz (see lit.) p. 74

- ↑ A “Komtur in Tempelhof” actually presupposes the possession of an order, but according to historical-scientific criteria this can only be regarded as an indirect indication.

- ↑ Klosterbuch (see lit.) Vol. 2 pp. 1276f

- ↑ Hans Eberhard Mayer : On the Itinerarium peregrinorum. A reply. In: Hans Eberhard Mayer: Crusades and the Latin East . London 1983, pp. III 210f

- ↑ For this reason, the older discussion as to whether “Templo” represents a place name and where to look for this place is outdated because it was conducted in ignorance of Mayer's remarks (note 8); see. Metz (see lit.) p. 77.

- ↑ Ten years earlier, i.e. 1237, Symeon was not yet provost, but pastor of Cölln and, as a documentary witness in the Brandenburg tithe dispute, ensured the first documentary mention of the twin cities on the Spreepass.

- ↑ In particular because of the documentary witnesses Marsilius (Stadtschulze von Berlin), Symeon (Provost von Cölln) and Abbot Siger von Lehnin. However, the Komtur von Lietzen cannot be completely ruled out either, because “de Templo” means much more often “of the Templar Order” than “of Tempelhof”.

- ↑ Brecht (see lit.) p. 7

- ↑ Brecht (see lit.) p. 6f, monastery book (see lit.) p. 1280

- ↑ See note 2.

- ↑ Kuhn (see lit.)

- ^ Theo Engeser, Konstanze Stehr: Heinersdorf village church (destroyed) . Osdorf community, Teltow-Fläming district. Jühnsdorf , 2005.

- ↑ Even further away from the four-part apse church is the Buckow village church , which also has a nave-wide tower, but neither an apse nor a retracted choir.

- ↑ With good reasons, Metz (see Lit.) p. 76 also refers to the document on Berlinchen in der Neumark; it is difficult to decide which arguments are more convincing.

- ↑ Kuhn (see lit.) p. 415

- ↑ This village foundation document is unique in the Mark Brandenburg. - There is an "old village point" in the area around Rixdorf; At Richardplatz, the regional archaeologist Adriaan von Müller (see lit. p. 294f.) came across strong remains of the wall, which he attributed to this "court" of the Templars.

- ↑ Klosterbuch (see lit.) p. 1276. It must have been at the location of today's Zenner inn .

- ↑ Waack (see lit.)

- ↑ Hartwig Sippel: The Templars. History and mystery . Augsburg 2001, pp. 190, 196, 202

- ↑ Fritze (see Lit.) pp. 32–36

- ↑ Brecht (see lit.) p. 6

- ↑ Article in the Heimatbote of February 3 and 10, 1939. Headline: “Hopes that were not fulfilled. Underground construction destroyed a legend. No trace of the famous 'underground passage' in Tempelhof. How may the rumor originate? "The text says (as early as 1939) with reference to other significant building work in Berlin in the 1930s:" This proves that such opportunities are also suitable for destroying local legends that have persisted over many centuries Example of the underground excavation on Berliner Straße in Tempelhof. "

Coordinates: 52 ° 27 '48.9 " N , 13 ° 22' 59.4" E