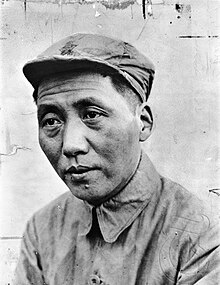

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong or Mao Tse-tung ( Chinese 毛澤東 / 毛泽东 , Pinyin Máo Zédōng , W.-G. Mao Tsê-tung , IPA transcription mau̯ ʦɤtʊŋ , ; * December 26, 1893 in Shaoshan ; † September 9 1976 in Beijing ) was a Chinese revolutionary , politician , party leader and dictator . In 1921 he was one of the founding members of the Chinese Communist Party , which he dominated from 1935. He led the communists in the Chinese Civil War against Chiang Kai-shek and consolidated his power on the Long March .

In 1949 he proclaimed the People's Republic of China . Mao helped launch China's industrialization programs and promulgated the first constitution of the People's Republic of China (1954). He also sent the troops of the People's Liberation Army to North Korea in the Korean War to help. At the same time he started the “ Chinese Land Reform ”, the “ Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries ”, the “ Three Anti and Five Anti Movements ”, the “ Sufan Movement ” and the “ Chinese Land Reform ” to consolidate control of the Communist Party. Anti-Right Movement ”. These movements resulted in the deaths of millions of Chinese and, in particular, made China a de facto one- party state . In 1958, Mao launched the " Great Leap Forward " campaign, which sought to quickly turn China into a powerful industrial country, but which eventually resulted in the deaths of 15–55 million people in the Great Chinese Famine . After Mao had partially left the center of power in 1962 , he started the " Socialist Education Campaign " in 1963 . To keep himself in power, he started the Cultural Revolution in 1966 . As a result, countless intellectuals and political opponents were murdered by the Red Guards and cultural treasures destroyed.

Mao is held responsible for up to 40–80 million deaths from avoidable famines, punitive actions and political cleansing. The so-called “ Mao Bible ”, a manual with quotations and short essays from Mao, was printed over a billion times worldwide. His socio-political approaches were largely reversed by his successors (especially Deng Xiaoping ); but his portrait still hangs on the Gate of Heavenly Peace . During his time, China saw the constant power struggles of the Cold War , particularly the Korean War , the Sino-Soviet rift , Nixon's visit to China, and the rise of the Khmer Rouge .

Childhood and school education

Mao Zedong was born on December 26, 1893 in a village near Shaoshan in the central Chinese province of Hunan into a wealthy farming family. His father Mao Yichang (毛 贻 昌, 1870-1920) saw himself in the 20th generation of the Mao clan and traced his ancestry back to the army leader Mao Taihua who fought against the Mongols until 1368 and after the establishment of the Ming dynasty in the Region of today's Xiangtan settled. Mao's father only had two years of schooling and was hard-working and hard-working. He managed to get out of the debt his father left him. With the money he had saved up while serving in the army, he bought between 15 and 20 mu of land, which he cultivated with the help of farm workers. He later became a wholesaler who, despite hunger, bought rice in Shaoshan and sold it to the big cities. Mao's mother Wen Qimei (文 素 勤, 1867-1919) came from a neighboring village of Shaoshan. She married Mao's father when he was 15 years old. Of their seven children, only three sons survived childhood. She was very religious and her folk Buddhism influenced Mao Zedong for all his life. By local standards of the time, the Maos were a wealthy farming family in their day.

Father Mao, who wanted to make his son a learned man and had given him the name Zedong ( benefactor of the east ), sent him to a private Confucian school in Shaoshan. Mao learned the material there by heart, but the ethical and moral concepts remained alien to him. His childhood China was in deep crisis. Mao's grandfather fought in the Taiping Uprising , considered the most terrible war of the 19th century. The Hundred-Day Reform had failed, the Boxer Rebellion had led to even greater concessions to the foreign powers. The population became impoverished because the traditional factories could not stand up to the factory goods from the foreign leased areas. During the self-strengthening movement , however, the beginnings of a modern education system and a modern army also arose. The numerous uprisings and reforms had created an awareness among the common people that the Qing dynasty would sooner or later fall; in the traditional thinking of many Chinese, the imperial family had forfeited the mandate of heaven . Mao experienced first hand the effects of the Ping Liu Li uprising and the insecurity that the activities of secret societies like the Gelaohui spread. This and his father's despotism made Mao a rebellious child.

At the age of 13, Mao left school due to the teacher's violence. Since the official examinations had been abolished and education no longer automatically meant entry into the imperial bureaucracy, his father hoped that Mao would help in his father's business. Against his father's wishes, however, Mao mainly occupied himself with reading, such as the works of the influential reformer Zheng Guanying . At the age of 16, Mao and his cousin 9 years older than him began attending a school that taught modern subjects. However, he only stayed at this school for a year because he suffered from the hatred and arrogance of his classmates: he was ostracized because of his rural origins and the dialect of the Xiang language , which was spoken in his home village. At the age of fourteen, Mao was married to eighteen-year-old Luo Yigu, whose clan was distantly related to the Mao family. Mao refused this marriage and hid with a friend in Shaoshan, Luo Yigu died in 1910.

At the beginning of 1911 Mao went to Changsha , 70 km away - at that time a transshipment point for goods and news from all over the world - to attend a new school there. A revolt against the Qing Dynasty was already in the air there and Mao was one of those who had their braids cut off as a sign of rebellion . After the news of the successful Wuchang uprising reached Changsha, Mao's school was closed. The province declared itself independent, Mao joined the Hunan army, but without completing a military mission. However, Mao saw the bodies of the leaders of the local uprising, Jiao Defeng and Chen Zuoxin - his first contact with power politics. He left the army and tried various schools until he was accepted into the Hunan Provincial Teachers Training College in the spring of 1913. There he was only diligent in the subjects that interested him, but the teachers respected him nonetheless. In 1917 he was named the best student in the school. He founded an association of Xiangtan students and becomes chairman of the student association. In this role, he revitalized the evening school for workers. In November 1917 he organized volunteers who, with the help of the police, defended the school from marauding soldiers. In April 1918 he co-founded the New People's Study Society , in which He Shuheg was also involved. The aim of this association was to renew China and the whole world. Mao Zedong's first writings date from this period. They show Mao's admiration for Shang Yang , the theories of vitalism and the power of human will, but also for the successful provincial governor Zeng Guofan . These were very widespread views among those Chinese who wanted to save their country from Western colonization efforts at the time. When Mao graduated from school, he had great ambitions, but was disoriented. During his school days he had built a friendship with the teacher Yang Changji , who strongly influenced Mao's viewpoints and drew his attention to radical positions such as those of Miyazaki Tōten . He was also influenced by classmates like Cai Hesen , one of the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party in its early days. In contrast to other politicians of his time, Mao did not attend any of the newly founded universities. He developed his positions in self-study in the Changsha City Library. He remained more rooted in cultural traditions than other, later communist revolutionaries.

Outsider in the Communist Party

Establishment of the CP cell in Hunan

Mao's teacher and friend Yang Changji was called to Peking University in 1918 . In mid-1918, Yang suggested that Mao and some of his classmates join the worker-student program and go to France. In August 1918, Mao and 25 classmates went to see Yang in Beijing . Through the mediation of this teacher, he found a job as an assistant librarian, where he got to know, among others, Li Dazhao , one of the most important early Chinese Marxists and co-founder of the Chinese Communist Party. Li was editor of Neue Jugend magazine , which shaped the political and intellectual direction of the May Fourth Movement . He introduced Mao to the ideas of Marxism and Bolshevism . He also made the acquaintance of Chen Duxiu here. Through him he got access to anarchist and Trotskyist ideas. In Beijing, too, he spent a lot of time studying himself, reading numerous articles on the topics of his time. At the end of his stay in Beijing, however, Mao was closest to Hu Shi and his philosophical pragmatism. Mao decided not to go to France while he was in Beijing. In April 1919 he was back in Hunan, not least because of his mother's illness.

Mao initially stayed in Changsha, where he was already an accepted leader, whereas in Beijing he was largely ignored. While he was working as a primary school teacher, China suffered a foreign policy defeat: the 1919 Paris Peace Conference decided that the German colonies in China would be handed over to Japan. Mao probably did not participate in subsequent May Fourth demonstrations , but he and friends organized a boycott of Japanese goods. He founded a student newspaper called Xiang River Rundschau (Xiangjiang Pinglun) with content similar to Chen Duxiu's publication. It attracted national attention, was printed in a relatively large edition of 5000 copies, but the 5th edition has already been confiscated by the police. Mao's early writings show the orientation towards communist anarchism of Pyotr Alexejewitsch Kropotkin , Mao's commitment to the abolition of Confucian constraints and for the rights of women. They also show the position that more justice can only be achieved peacefully, because if you try to remove oppression through oppression, in the end there will be oppression again .

In the winter, Mao went to Beijing again to get the central government to remove Governor Zhang Jingyao , who had plundered Hunan Province , but to no avail. During his stay, he often met with Li Dazhao and Deng Zhongxia and read the Marxist works available in Chinese translation. From May 1920 Mao stayed in Shanghai, where he worked as a washer and campaigned for Hunan's independence from China, a constitution and democratic elections. Chen Duxiu, who had fled Beijing to Shanghai in the meantime and was in contact with the Comintern , tried to talk him out of these ideas.

Upon his return to Changsha - Zhang had since been ousted - Mao got a job as elementary school director. In addition, he opened a book shop for political literature at affordable prices and founded a society for the study of Russia. His efforts for the independence of Hunan were unsuccessful, which Mao attributed to the lack of determination and willingness to make sacrifices of his colleagues. Towards the end of the year he came to the conclusion that Bolshevism was the right ideology because it was radical. From that point on, Mao saw himself as a Marxist and was guided by Marxism and the history of the October Revolution. He started by founding underground cells for the Changsha Socialist Youth League.

In July 1921, Mao attended the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) 1st Congress as one of the two representatives of the Changsha Cell. The party then had only 53 members and the possibility of a seizure of power was a long way off. Mao kept the minutes of this congress and, apart from that, was not very active. At the congress, the Comintern officials explained how to seize power in backward countries and colonies, but Mao did not understand this tactic, as did the other Chinese participants.

In Changsha, Mao devoted himself to the tasks entrusted to him. Together with Li Lisan , whom Mao had met at school, he founded trade unions, although there were fewer workers in Hunan in the sense of Karl Marx . In 1922 he organized several powerful strikes, for example in Anyuan , where Mao went several times to organize the miners and railroad workers of the coal mines. These strikes resulted in significant economic improvements for the workers. Most of the workers in Hunan were politically disinterested, so Mao's cells in the CCP and the Socialist Youth League grew slowly, mostly through personal relationships. In November 1922, both organizations had 230 members together, making them the strongest sub-organization in the country. As chairman of the Hunan Trade Union Federation, Mao was negotiating partner for Provincial Governor Zhao Hengti . With money from the governor, he founded a school to train cadres of the Communist Party. Mao traveled to Shanghai again for the 2nd Party Congress, but forgot the venue and therefore did not attend the congress.

In the fall of 1919, Mao had an affair with his former classmate Tao Yi, which, however, broke up because of different political views. From September 1920 he met the daughter of his late teacher and friend Yang Changji Yang Kaihui on a regular basis. After initial shyness, they married in the winter of 1920 without a bride present or a Chinese ceremony; Love marriages were not the norm back then. It was not until October 1921 that they were able to move into a shared apartment.

Kuomintang member

In January 1923, the CCP Central Executive Committee decided to move Mao to Shanghai headquarters. It was high time for that, because the warlord Wu Peifu had begun to use force to fight the unions and Governor Zhao Hengti had ordered Mao to be arrested and executed. Mao traveled via Shanghai to Canton , where the 3rd Party Congress was held in June. At this congress, at the request of the Comintern, the first united front was enforced and Mao was elected to the nine-member executive committee of the Communist Party and as head of the organizational department of the first united front. Mao was divided about the united front policy, but ultimately he supported it: It was clear to him that all democratic forces would have to unite in order to end the era of warlords . His efforts to set up cells for the Kuomintang (KMT) from Shanghai were unsuccessful. At the end of December 1924 he asked for leave of absence for health reasons; The never-ending friction between the Communist Party and the Kuomintang, as well as the constant interference and frequent changes in personnel and politics of the Comintern had troubled him.

Mao spent the greater part of 1925 in his native Shaoshan. There he began to organize the local farmers and to interest them in communism. Kaihui began to teach in an evening school for farmers. Although he had only disdain for the rural population until then, he realized here that a revolution in China could only be successful if it was based on the countless impoverished peasants. Mao had to flee Hunan again in the summer because he had instructed starving farmers to force a wholesaler to sell them rice at reasonable prices. He went to Canton and began to work at the Whampoa Military Academy , which had recently been founded . Among other things, he was the editor of the Politische Wochenzeitung , the KMT's propaganda organ. In mid-March he was appointed director of the Institute for the Education of the Peasant Movement, with which he could only deal with the mobilization of the rural population and became an expert on the peasant movement within the CCP. The many rural dwellers, who had no better alternative than to get by in gangs, as beggars or as mercenaries in one of the warlords' armies, saw Mao more and more as potential allies of the CP. He repeatedly let himself be released from his obligations in Canton in order to investigate the situation of the farmers.

In the course of the KMT's northern campaign , Mao was transferred back to Shanghai, where he headed the working group for the mobilization of peasants with great activity and extensive travel. Mao hoped that the end of the warlords' rule would also mean the end of the landlords. Again he was involved in the difficult maneuvering between the CCP, Comintern and Kuomintang. At the beginning of 1927 he went back to Hunan, where he researched the status of the peasant movement. The extensive report on an investigation of the peasant movement in Hunan , which he presented to the party leadership after his return, was accepted, published several times in China and partially published in English and Russian in the newspaper Communist International . From here on, Mao assumed a violent revolution by the peasantry. In April 1927 he was appointed a member of a five-member committee of the ZEK of the KMT, which is to work out measures for the transfer of land to farmers .

The first united front finally collapsed in mid-May when Chiang Kai-shek had numerous communists killed in Shanghai and three days later a blow was struck against the communists in Canton . Mao was in Wuhan at the time, trying to find a solution to the land distribution issue within the Kuomintang. However, he resigned himself to the fact that the Kuomintang leadership was not looking for a solution and that they were only making big words.

The CCP was in a hopeless position at this point. On a short trip to Hunan, Mao concluded that the CCP can only be successful in the struggle for power if it has its own military. Political struggle, mass movement and a united front are pointless because in militarized China of the 1920s all political power comes from the barrel of a gun . In Mao's view, such a communist army should be recruited from impoverished peasants. Mao's proposal to set up communist bases in hard-to-reach areas was only partially approved by the Comintern. It now counted on revolts against the Kuomintang, in whose planning Mao was involved as an expert in the mobilization of peasants.

Mao was not involved in the Nanchang uprising of August 1, 1927. On August 7th, he participated in the Extraordinary Conference of the Central Committee of the CCP , in which the new Comintern representative Bessarion Lominadze and Mao criticized Chen Duxiu's previous policies as not being radical. After the conference, Mao was supposed to go back to work for the party in Shanghai, but insisted on organizing an autumn harvest riot in Hunan to implement his own concept of creating liberated zones in the agrarian hinterland , probably inspired by Peng Pai's Hailufeng Soviet . In Mao's opinion, the entire land should be jointly owned, although he had to be aware that the farmers did not want this.

Base in Jinggangshan

In August 1927 Mao was sent to Hunan to carry out the autumn harvest uprising . According to the Comintern, the goal should be to capture the provincial capital, Changsha ; Mao was not convinced of this strategy. He headed the front committee, which dealt with the military questions of the uprising. The September 9 uprising, which was supposed to involve farmers, railroad workers and miners, was quickly put down. Mao narrowly escaped execution, so Mao and the members of the Hunan Communist Party Committee decided not to attack Changsha. Instead, Mao and about 1,500 soldiers moved towards the Jinggang Mountains , where they arrived in late October. An assembly of representatives of the workers, peasants and soldiers as the legislature and a people's assembly as the executive were brought into being. Mao had to come to terms with the leaders of the local gang called Brotherhood of the Forest, who controlled the region. Yuan Wencai , one of these bandit leaders, paired Mao with He Zizhen to ensure his loyalty.

While Mao was in the mountains, the CP shrank considerably under pressure from the Kuomintang. Numerous communists withdrew to the country. Mao was condemned for his "military opportunism" and removed from the Politburo. This started fights for him with rivals within the CP who viewed Mao's troops as ordinary bandits. In April 1928, the remaining Nanchang Uprising troops, commanded by Zhu De , arrived in the Mao-controlled area. Zhu and Mao agreed to jointly establish a Soviet with the capital Longshi , implement land reform and arm the masses. By the end of the year an egalitarian, militarized society based on terrorism against the individual and financed by looting and the opium trade was established in the Jinggang Mountains. In May 1928, Zhu and Mao commanded about 18,000 poorly trained, undisciplined and malnourished fighters, a third of whom were sick or wounded. The troops had a total of about 2,000 rifles. By November 1928, the entire land was confiscated and redistributed against considerable resistance from the farmers. The failure of the autumn harvest uprising had shown that the local elites had a very high influence on the poor farmers. For this reason, the people around Mao took action against the rich peasants and landlords with great severity.

At the 6th Congress of the CP in June and July 1928, which took place in Moscow, Mao's ideas were sharply criticized. Nevertheless, he was elected to the Central Committee of the CP in absentia - after all, he was the only one who could create and maintain a communist base. Criticisms of Mao included the issue of land distribution and how wealthy farmers were dealt with in the context of land reform. Party headquarters feared that it would lose control of Mao and Zhu and that they would become warlords. She instructed Mao and Zhu to relinquish army command and divide the Red Army into smaller units; Mao ignored these instructions. At the same time, the Comintern followed Mao's line of guerrilla warfare.

In December 1928, Peng Dehuai's troops also arrived in the Jinggang Mountains. It was clear that the region was so unproductive but also so plundered that it could not sustain the soldiers, and that the Jinggang Soviet had failed. Contrary to the party's wishes, the communist base was therefore relocated to southeast Jiangxi, on the border with Fujian , in January 1929 . During this period, Mao Zedong became a father again. Since Mao, his wife and the army were on the run from Kuomintang persecutors, their daughter Jinhua was left with farmers half an hour after she was born.

Jiangxi Soviet

The regime that Mao and Zhu established in their new base was not that different from the one in Jinggangshan. Land reform was also carried out in south-east Jiangxi, following the requirements of the Comintern and the deculakization .

The arrival of numerous officials and Comintern advisors trained in the Soviet Union led to intense conflicts. Mao was angry with the cadres who had no idea about grassroots work and only adhered to dogmas from the books. His motto, seeking truth in facts, goes back to this time. Conflicts between Zhu and Mao about the correct leadership of the Soviet intensified in the first half of 1929, and were intensified by the Central Committee envoy Liu Angong . From June to November 1929 Mao therefore withdrew due to illness and depression, until the Central Committee took his side.

After his return to Soviet politics, the party found itself on the Li Lisan line and thus on a much more aggressive course. In the summer of 1930, Zhu and Mao and their troops had to attack the cities of Jiujiang and Nanchang at the request of the Communist Party headquarters , both operations failed. The city of Changsha was captured and held for a few days, which the Kuomintang used as an opportunity to execute Mao's wife Yang Kaihui . The losses to the Red Army were also enormous. It now had 54,000 soldiers, but hardly any equipment. Mao's insight from these developments was that the Soviet must establish proper government organs. In October 1930, the poorly defended city of Ji'an was taken and the Soviet government of Jiangxi Province was proclaimed. A year later, on November 7, 1931, the First Congress of the Chinese Soviets took place in Ruijin. Mao was elected chairman of the All China Executive Committee and chairman of the Council of People's Commissars. Ruijin was made the capital of the Chinese Soviet Republic. In mid-April 1932, Mao got the Soviet government to declare war on Japan, hoping to win the sympathy of patriotic Chinese.

At the same time as these events, Comintern representative Pawel Mif arrived in Shanghai and began to reorganize the Communist Party leadership at will. Mao lost influence as a result, and his methods of guerrilla struggle were vehemently criticized. Since the Kuomintang smuggled provocateurs and spies into the Communist Party at the same time and launched an attack with 100,000 soldiers on the Soviet, the internal fighting with the Futian incident reached its peak for the time being. This wave of purges killed more than 1,000 communists. Little did he know at the time that Stalin had been protecting him and supporting him with propaganda since the late 1920s. When Mao fought fierce power struggles with graduates from Sun Yatsen University in Moscow and Pawel Mif, Mao and Zhu allied with Wang Jiaxiang and Zhou Enlai . Nevertheless Mao lost influence in the party and army. Again he retired to the mountains; Bo Gu took control of the party . Otto Braun replaced Mao Zedong's guerrilla strategy, with which four attacks by the Kuomintang could be repulsed, with trench warfare, as taught at Soviet military academies. In the summer of 1934, the situation of the Soviet was hopeless and preparations were made for evacuation. Mao found out about this only a few days before the march, when he was with the First Corps of the Red Army near Yudu , 60 km west of Ruijin. Mao's wife He Zizhen was allowed to take part in the Long March , the then two-year-old son Anhong had to stay behind and has been missing since then.

Seizure of power

Long march

At the beginning of November 1934 the communists withdrew almost 90,000 men towards the west with an unknown destination. The mood among the fighters was bad, the Red Army was like a platoon of defeated people. Mao used the atmosphere and the long rides to win Luo Fu , later Wang Jiaxiang and Zhou Enlai , from Bo Gu's supporters . He had the advantage of being able to reject any guilt for the loss of the Jiangxi Soviet. His name thus stood for a new beginning. At the first important vote on the Long March, namely the one about the goal of the evacuation, he was able to prevail and the mountainous terrain of Guangxi , Guizhou and Sichuan was chosen as the first place of refuge.

In January 1935, the Red Army took a break from marching in the town of Zunyi and the party leadership met for a discussion at the three-day Zunyi conference . Bo Gu and Zhou Enlai , who had been in charge of the Communist Party's military since 1932, had to report back. Luo Fu, and after him Mao Zedong, attacked Bo and Otto Braun heavily in their interventions and blamed their mistakes for the loss of the Soviet. At the end of this conference Bo Gu had no more supporters apart from Kai Feng and Otto Braun, while Mao was re-appointed as a member of the Standing Committee of the Politburo. In February Bo had to surrender his post as general secretary of the party to Luo Fu, and in March Mao was elected political commissioner of the newly created military council. After this conference, the trio of Luo, Wang and Mao dominated the party. Mao had thus regained the influence and positions that he had lost in 1932.

In June 1935, the Mao's First Front Army met Zhang Guotao's Fourth Front Army . Zhang's troops were stronger and better equipped, while the Red Army had practically lost its combat readiness. The political leadership of the First Front Army, however, was legitimized by Moscow. Zhang and Mao also had a personal dislike for each other. The inevitable power struggle between Zhang and Mao ensued; Mao risked another division of the communist camp. He wanted to move north to set up a Soviet together and expand it to the border with the Soviet Union . He also wanted to take up the fight against the Japanese invasion in order to legitimize his claim to leadership over Zhang Guotao with the argument of the fight for national sovereignty.

On October 22, 1935, Mao declared the Long March in northern Shaanxi Province over. Here Mao's army was united with the forces of the Bao'an Soviet of Liu Zhidan . The Long March allowed Mao to take power over the party, but the Red Army had shrunk to 5,000 soldiers. The Communist Party initially chose Wayaobao as its seat. Zhang Guotao and Zhu De did not arrive in North Shaanxi until November 1936 and were thus out as candidates for power in the Communist Party.

Rebuilding the Communist Party in Shaanxi

In the months after arriving in northern Shaanxi, Mao reorganized the Red Army, which now had about 10,000 fighters. The strategy of portraying the Red Army as an anti-Japanese army began to work. The movement of December 9, 1935, which had called for the government in Nanjing to take stronger action against Japanese aggression, led to an increased influx of the Communist Party. Mao Zedong's approach was in line with Moscow, although contact there was temporarily broken: Stalin wanted a stable China as a safeguard for the Soviet Union against Japan. So he directed the Communist Party to seek a united front with the Kuomintang. Mao also sought a consensus on this with his former opponents. In December 1935, the party decided that the national bourgeoisie should join the workers and peasants of China to fight the Japanese.

The Politburo meeting of December 8, 1935 accordingly formulated a call to the Kuomintang for an armistice and a common fight against Japan. However, Chiang Kai-shek prompted further attacks on the communists. The most important question now became to win at least part of the Kuomintang to a ceasefire. An opportunity to do so came in the person of Zhang Xueliang , who had withdrawn from Manchuria with his troops from the Japanese in Shaanxi's provincial capital, Xi'an , and who was also looking for allies. As early as November, Mao had offered a commander of Zhang's troops a ceasefire. In April 1936 there were direct negotiations that resulted in an armistice and even arms deliveries from Zhang to the Communist Party. For this reason, Chiang sought out Zhang for a personal conversation in Xi'an. Parallel to this conversation, over ten thousand students demonstrated against Chiang's slack policy on Japan. This conversation resulted in Chiang's arrest . Mao was jubilant - on December 15, the entire Communist Party leadership sent a letter to the Nanjing government demanding that Chiang be brought to a people's court. However, Stalin put pressure to release Chiang. Shortly before these events, Germany and Japan had signed the Anti-Comintern Pact . Stalin wanted a stable China now more than before and Chiang was the strongest actor. Therefore, Stalin urged Mao to resolve the conflict peacefully. Relations between Stalin and Mao came under great pressure because it was evident that Chiang and his numerous German advisors were working first to destroy the Communist Party and only then to oppose Japan. In the end, however, the Chinese Communist Party was financially dependent on the Soviet Union. On February 10, 1937, the Communist Party again sent a message to the third plenary session of the Kuomintang, in which it formulated the basis for cooperation against Japan.

From March to May 1937, pressure from Moscow resulted in an understanding between the Kuomintang and the KP for cooperation. In July 1937 the second united front was formally adopted. The Red Army was placed under the command of the government in Nanjing and was now the 8th March Army of the National Revolutionary Army, commanded by Zhu De . Mao recognized the leading role of the Kuomintang; however, both sides were already planning the internal Chinese struggle that would continue after the end of the war against Japan . Mao also enforced on August 22, 1937 that the Red Army would continue to be a partisan army with guerrilla tactics. He argued that the loss of the army would also be the end of the Communist Party and its officials personally. From then on, the Red Army carried out actions in Japanese-occupied territory, and social changes in the territories ruled by the Communist Party also continued.

During the Great Terror in the Soviet Union , Mao began to seek further allies. For example, he contacted the Labor Party and welcomed Evans Carlson , President Roosevelt's confidante . Carlson reported much more positively about Mao than of Chiang: he described him as a dreamer and genius and as someone with the gift of getting to the heart of a problem. He considered the policy of the CP at the time to be liberal-democratic and emphasized that Mao was planning a coalition government for China. At the same time, he resolved the power struggle with his opponent Wang Ming , Stalin's confidante and representative of China in the Comintern . Wang had repeatedly sowed doubts about Stalin's allegiance to Mao, and Stalin required Wang to report any Trotskyite deviations. Since Zhang Guotao , Kang Sheng , Bo Gu and Zhou Enlai were also on Wang Ming's line and, not least, worked closely with the Kuomintang, Mao sent his own representative, Ren Bishi, to Moscow. When the Comintern later emphasized the importance of supporting Mao Zedong as the leader of the Communist Party, the leadership problem was solved. Mao's Chinese communism thus prevailed against the communists trained in the Soviet Union. The cult of the leader and Stalinization of the party began; Mao began to actively promote this cult himself. The reports of Edgar Snow , Agnes Smedley and other Western journalists led to a certain spread of the Mao cult abroad.

In June 1936, because of an attack by the Kuomintang, the Communist Party lost its headquarters in Wayaobao and had to flee to Bao'an , a semi-deserted town with around 400 inhabitants. In January 1937, the CCP Central Committee moved from the Bao'an Caves to Yan'an . He Zizhen had recently given birth to their fifth child, Li Min . Life in Yan'an, where many young people came who wanted to become involved in communism, also brought many temptations in gender relations. The marriages of numerous party officials were divorced. He Zizhen also left Mao after affairs with the American journalist Agnes Smedley and the Chinese actress Wu Lili .

In September 1938, Mao began an affair with the film actress Lan Ping. He married her on November 19, 1939, having previously chosen the name Jiang Qing for her. Jiang Qing was the former lover of Kang Sheng , who would later become head of the Chinese secret services and, among other things, directed the campaign against the deviants . Later they were part of the gang of four . Their daughter Li Na was born on August 3, 1940.

Victory over the Kuomintang, beginning of the Mao cult

In July 1937 Mao began to deal intensively with Marxist and Bolshevik philosophy and to give lectures at the newly founded Anti-Japanese Military-Political University. He also published numerous reflections on political and military topics and transferred the ideology of Marxism to Chinese culture and reality. This Sinization of Marxism was tolerated by Stalin, because he knew that Mao had to demonstrate intellectual achievements in order to establish a leadership cult in China.

In order to broaden popular support and out of concern for the cohesion of the Communist Party, Mao and Chen Boda developed the concept of the New Democracy from the end of 1939 . It included state respect for property, encouragement of Chinese entrepreneurship, encouragement of foreign investment, control of key sectors by the state, a multiparty system with coalition government and democratic freedoms. However, the Communist Party claimed leadership in this concept. Mao told foreign visitors that the New Democracy was a necessary intermediate step for China on the way to socialism and ultimately communism. It is also possible that it was only developed as a deception from the start, similar to how Stalin disbanded the Comintern in World War II. When it became clear that the communists would win the civil war, Mao turned away from the concept. However, it had led to a split of left groups within the Kuomintang under the leadership of Sun Yat-sen's widow Song Qingling .

With the establishment of liberated areas behind the Japanese lines, the membership of the Communist Party grew very quickly. This meant that numerous new party members had not previously had any contact with communism. In addition, about two-thirds of the new members were illiterate . Mao rejected purges like the one in the CPSU; instead, Mao spoke of rectification and alignment movements. He took Liu Shaoqi to Yan'an to take care of the internal affairs of the party and to train the party cadres. In the base area of Yan'an alone, 44 party schools were established between 1935 and 1945, where new members were trained and socialized and where ideological control was to be exercised. In addition, meetings began to be called where the participants were expected to self-criticize and practice. Training courses and self-harm campaigns were organized. The first special commissions were set up under Kang Sheng .

At the party congress in Yan'an in 1945 754 delegates took part, which meanwhile represented 1.2 million members. At this unified party convention - Wang Ming had meanwhile been dismantled, Zhou Enlai no threat to Mao's claim to leadership - a new party statute was passed in which Mao Zedong thinking was the basis of the Chinese Communist Party. Mao was now the pre-eminent leader of the communist movement and held all power in his hands. His earlier positions, which had often brought him an outsider role, were now declared to be the central CP line and the policy previously pursued by the majority of the CP became minority positions. A committee for the purification of history was given the explicit mandate to adapt the story to the needs of the cult.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, it was clear to Mao that the US would have to defeat Japan and that the communists would have to spare their strength for the ensuing war against the Kuomintang. Mao therefore welcomed the Dixie Mission , with which the United States wanted a team led by David D. Barrett and John S. Service to investigate the communists. He was able to convey to the US representatives that the CCP was independent from the CPSU and that the US was the only country that could help China achieve the desired rapid economic growth. In order to prevent the US from giving aid to the Kuomintang, Mao even considered renaming the Communist Party. The picture that the participants in the Dixie mission drew of the CP was very positive. However, it was received with skepticism by large parts of the American secret services. The American government was not deceived.

Shortly before Japan's surrender , the Chinese civil war flared up again. Negotiations between Mao and Chiang brought no result. The US Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley tried to mediate an understanding between the KP and the Kuomintang and accompanied Mao to Chongqing on August 28, 1945. The talks should last six weeks. Chiang Kai-shek, however, persisted in refusing to cooperate with the communists. In the same month Chiang signed a friendship and alliance treaty with the Kuomintang. After the surrender, the Kuomintang controlled two-thirds of the Chinese territory, while the communists held some liberated areas with the center in the border area of Shaanxi , Gansu and Ningxia . A total of 95.5 million people lived in the communist-controlled areas. The Japanese soldiers were ordered to surrender only to Kuomintang soldiers; Japanese captured soldiers were used in activities against the communists. In this way, the Kuomintang was able to strongly push back the Red Army until 1947. The Yan'an Base also had to be abandoned. Mao instructed the Red Army troops to only engage in combat operations if their victory was certain and to use guerrilla tactics only.

Despite Chiang's offensive on the base in Yan'an in 1947 and despite Stalin's reluctance to deliver arms and money - his distrust of Mao had grown and he did not want to provoke the United States - the People's Liberation Army grew from 1.2 to 3 within one year .5 million soldiers. In the summer of 1947, the Red Army implemented Mao's plan to occupy the Dabie Mountains in central China. This destroyed all of Chiang's plans and forced him to move massive troops. The influx of the People's Liberation Army and the mistakes of Chiang Kai-shek meant that Mao was able to unite his armed forces with the troops of Liu Shaoqi and Zhu De in Xibaipo in May 1948 . While Chiang's troops increasingly disintegrated due to corruption and the persecution of personal interests by commanders, the Red Army fighters were fanatical. In January 1949 they took Manchuria , and a few months later Beijing, Shanghai and Nanjing were conquered. By 1950, all of China was taken over by the communists. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China at the Gate of Heavenly Peace and was now faced with the daunting task of stabilizing the new state and its unity. He led a coalition government as chairman, with Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De and Song Qingling as his deputies.

Chairman

When the People's Republic was founded, Mao was already 56 years old and his health was in poor health. He suffered from insomnia and at times from disorientation. Even so, he worked 15 to 16 hours a day, especially at night. From September 1949 he lived in Zhongnanhai , where he lived in a traditional courtyard with his relatives . Apart from political relations, he did not have any friendships. His wife Jiang Qing organized his daily routine, Mao's only amusement was dance events for which Jiang Qing organized young dance partners.

He preferred to receive his employees and guests in his bedroom with a huge bed, from which he organized the new state. Contrary to Stalin's advice, Mao had chosen Beijing as the new capital of China, even though he originally detested the decadence of the Qing dynasty . The fundamental changes planned for Beijing - including the demolition of the Forbidden City - were not implemented due to the political turmoil in the young People's Republic. The concept of the “ new democracy ” gave way to the “democratic dictatorship of the people”.

Emancipation from Stalin

As early as 1948 Mao was planning a visit to Stalin with his economists Ren Bishi and Chen Yun . However, Stalin repeatedly canceled this visit. Only in December 1949 did Mao go to Moscow on the occasion of Stalin's 70th birthday. A three-month stay was planned, which was also Mao's first trip abroad. For security reasons, Mao traveled by train - soldiers with machine guns were posted every 50 meters - and crossed the border to the Soviet Union in Otpor , from where the Soviet secret service took care of Mao. With the exception of two receptions, however, Stalin largely ignored Mao. Mao was disappointed and felt pushed back to the "Lipki" dacha . Stalin initially rejected Mao's request to terminate the friendship treaty with the Kuomintang government, which was advantageous for the Soviet Union . An agreement on friendship, alliance and mutual aid was only reached towards the end of the visit, but in the secret annexes of this agreement, China granted the Soviet Union privileges in Xinjiang and Manchuria . In addition, joint ventures in mining and heavy industry under Soviet leadership were planned and China did not regain control of railways in Manchuria and the military port of Lüshun for the time being.

Mao was very angry about what he perceived as Soviet imperialism . However, Stalin mistrusted Mao, whom he had repeatedly referred to as a “cave Marxist,” and saw a growing China as a potential competitor to his hegemony in the communist camp. However, Mao was largely dependent on Stalin. At Mao's request, Stalin sent his Marxism expert Pavel Yudin to China, who examined Mao's works for two years and confirmed to Stalin that Mao was a Marxist. In Moscow, however, Mao had also noticed Stalin's physical weakness. Stalin, who did not want a strong China, put a brake on economic aid for Mao and rejected Mao's requests to draw up a five-year plan. Mao therefore pushed through Stalinist changes without consulting Stalin. He let the communist apparatus oust the traditional rural elites, whose strong resistance was broken with violence. By 1951, about two million people paid with their lives for these measures and another two million were deported to camps. Mao's Stalinization was directed first against landowners ( Chinese land reform ), then against members of the army who were considered unreliable, later against (supposedly) corrupt officials and finally against private entrepreneurs ( three anti and five anti campaign ). By September 1952 two thirds of industry and 40 percent of trade were in state hands. In 1951, a campaign of indoctrination targeting the country's intellectuals began and the party was purged of unreliable party members - by 1953 10% of the Communist Party had been expelled.

With regard to the task of the New Democracy , the party leadership was divided. Above all, Liu Shaoqi and Zhou Enlai stuck to the term and the step-by-step construction of socialism called for by Stalin. The conflict became apparent in connection with Bo Yibo's tax concept - he wanted to equate private and state-owned companies. At the conference on economic and financial issues in the summer of 1953, Mao brought the party leadership on his line: Stalin had died in the meantime, and Mao was now unhindered to push for an acceleration of the construction of socialism. Despite the political disputes and repression, the economy was stabilized, in 1953 economic output returned to the level of 1936 and inflation fell into the single digits. The Soviet support - especially the know-how provided - was essential for this. However, the new approaches were not able to solve the supply problem. The farmers - often forcibly organized in co-operatives - were taxed heavily in order to be able to supply the cities, so that the rural population was latently undernourished.

Stalin's successor Nikita Sergejewitsch Khrushchev absolutely needed Mao's recognition as the leader of the communist camp, because Mao was held in high esteem in the communist-ruled world. He visited China in September 1954, made numerous promises to the Chinese side and surrendered to an exuberance of friendship. Mao and the rest of the party leadership interpreted this as weakness. On February 25, 1956 Khrushchev held on the XX. CPSU party congress gave his secret speech with which he initiated de-Stalinization . Mao was not present at the convention and was informed of the shocking news from Deng Xiaoping and Zhu De . Most of all, Mao was dismayed that Khrushchev obviously expected the other communist parties to accept what he was pretending to be. De-Stalinization gave Mao the opportunity to develop a course that was independent of the politically weak Khrushchev. Mao's impression of Khrushchev's weakness was confirmed during his visit, during which the Soviet side offered numerous joint projects. In April 1956 agreements were signed for 55 industrial projects, including systems for missile technology and nuclear weapons. Nevertheless, the Chinese party and the Soviet party argued over theoretical questions, above all a possible peaceful transition to communism and a peaceful coexistence of capitalism and communism. The Chinese side denied both possibilities. Stalin's performance ultimately rated Mao as 70% positive and 30% negative for China.

Korean War

Mao knew as early as 1949 - the Chinese civil war was not over yet - of Kim Il-sung's plans to attack the militarily much weaker South Korea . In view of the large number of Korean participants in the liberation of Manchuria, Mao Kim promised Chinese support in these plans. In the spring and May of 1950, Mao Kim promised to help him with the three Korean divisions of the People's Liberation Army and, if necessary, with Chinese "volunteer organizations." Neither Kim nor Mao knew at the time that Stalin wanted to provoke the United States' entry into the Korean War in order to bind the forces of both the United States and China in the longer term. Mao believed that the US would not risk a major war over an area as small as South Korea.

After North Korea had conquered South Korea almost completely by October 1950, UN troops under American leadership succeeded in repelling the North Korean troops and bringing them to the brink of defeat. Mao was reluctant to send his troops to war under these circumstances. He wrote to Stalin that the war in Korea would thwart all plans for the peaceful reconstruction of China. Most of the rest of the Chinese leadership - including Zhou Enlai and Lin Biao - were also against the war. Stalin brushed Mao's concerns off the table, but declined direct Soviet support for Kim. On October 5, Peng Dehuai argued in the extended plenary session of the Politburo that China must avoid an American-ruled Korea. The decision to enter the war was made. On October 12, Mao backed down again in a letter to Stalin, after which Stalin ordered Kim to give up Korea and retreat to Soviet or Chinese territory and take up guerrilla warfare from there. On October 13, Mao again agreed to send troops, so that on October 19, four field armies and three artillery divisions of the People's Liberation Army marched in. The number of war casualties on the Chinese and North Korean sides quickly rose into the hundreds of thousands, so that in the summer of 1951 Lin Biao and Gao Gang tried to get Stalin approval for armistice negotiations. In 1952, Mao even had to decide to provide food aid to North Korea despite shortages in China. However, Stalin wanted to delay the end of the war, so that an armistice could only be reached after Stalin's death on July 27, 1953. Economically, the war was an extreme burden for China because Stalin demanded that the granted Soviet credit be used to pay for Soviet weapons.

During the Korean War, Mao lost his son Mao Anying , who had volunteered for the war and was assigned to the General Staff. He was killed in an American air raid. Outwardly, Mao received this news indifferently and said that a war requires victims. On the inside, however, he was badly hit, suffered from insomnia for a long time, did not eat and smoked chain.

Rapid building of socialism

Stalin's death - on the occasion of which Mao should have honestly mourned - made it possible for Mao to break the resistance within the party to the rapid development of socialism and to give up the concept of the new democracy . In addition, the Soviet Union had promised to help with industrialization and electrification projects and to provide documents for the construction of industrial plants. The struggle for the party line between Mao and the moderates lasted until early 1954. One of the high points of this conflict was the Rao-Gao affair. Gao Gang was one of the most powerful politicians in the Mao camp; he had at the same time had good relations with Stalin and had also been Stalin's informant. Although Mao and Gao were close to each other in terms of content, Mao now wanted to get rid of Gao. Gao interpreted the confidential talks Mao had with him as evidence of Mao's support. He intrigued against the moderates around Liu and Zhou, but Mao dropped Gao and his ally Rao Shushi in February 1954. On Mao's initiative, they were criticized in the 4th plenary session of the Central Committee and lost their positions. This was the first major political purge since the People's Republic was proclaimed. A campaign followed to find more counterrevolutionaries inside and outside the party. Numerous cultural workers such as the philosopher Hu Shi , Yu Pingbo or the writer Hu Feng were attacked. Doctors were accused of poisoning the party leadership. There was repression against tens of thousands of party cadres.

The technical backwardness, the small units, the rural overpopulation and the archaic social conditions stood in the way of rapid progress in agriculture. It was clear that innovations were necessary, the party left around Mao rejected the market-based approach of the moderates and prevailed with their demand for collectivization. In November 1953, a state monopoly was introduced with artificially low purchase prices for grain, edible oil and cotton. This led to an increase in agricultural households, which were dependent on state aid, the farmers no longer had any incentive to increase their yields, and unrest in the country broke out. The grouping of farm households into cooperatives was accelerated compared to the goals of the first five-year plan, which again led to resistance from farmers. These often slaughtered their animals in order not to have to bring them into the cooperatives, or they fled to the cities. On the advice of the director for rural work Deng Zihui , the pace was slowed down and co-operatives formed under duress were partly dissolved again from 1955. Mao then called on the local cadres, bypassing the party hierarchy, to accelerate the movement of the cooperatives, and a party plenum with numerous delegates from the local party organizations approved Mao's course. The result was that in June 1956, of the 110 million rural households, around 92% belonged to a cooperative. Compared to the Soviet Union, collectivization was relatively peaceful despite coercion, resistance and unrest.

The private entrepreneurs in China were expropriated, which was partly done by setting purchase prices, partly by displacement and partly by compensation with pension payments. Workers' conditions deteriorated. There were numerous strikes in industry, although the unions were controlled by the Communist Party, which now also represented the employers' side. In the second half of 1956 alone, around 10,000 strikes were counted. Despite the shortages of raw materials, labor and electricity, the Communist Party now had absolute power over the politics and economy of China.

On September 20, 1954, the new constitution of the People's Republic was adopted, from then on Mao held the office of Chairman of the People's Republic. During this time he suffered from severe insomnia, barbiturates in very high doses did not help.

Hundred Flower Movement

After Mao no longer had to take Stalin's instructions, he began to think about building socialism more efficiently than in the Soviet Union. In his speech on the ten great relationships , he stated that, in his opinion, the Soviet Union had taken detours because Stalinism was not radical enough. According to the principle of “more, faster, better and more economical”, he proposed high investments in light industry and the development of the interior. The spiritual incentives to work should be strengthened alongside the material incentives. The share of the economy under central administration should be reduced and autonomous production complexes should emerge. The speech was largely ignored and misunderstood, with Zhou Enlai arguing that the proposed volume of investment was far beyond the capabilities of the Chinese economy. To publicly show his strength, Mao went swimming in the Pearl River , the Xiang River, and the Yangtze River . Nevertheless, Deng Xiaoping rejected personality cult in his speech at the 8th Congress of the Communist Party and Mao Zedong thinking was removed from the party's statutes. Mao was dissatisfied with the decisions.

Parallel to these events, anti-Stalinist uprisings took place in Eastern Europe, which Mao believed had been triggered by Khrushchev's policies. At the beginning of October in Poland, Mao summoned the Soviet ambassador, Pavel Fyodorovich Yudin . He explained to him in his bedroom and in pajamas that China would side with Poland in the event of Soviet violence. Mao sent a delegation to Moscow and called for the same peaceful solution to the Hungarian uprising as to the Polish October. It was only after intelligence officers and party officials were lynched in Hungary that Mao called for a violent restoration of order and accused the Soviet leadership of having laid the sword of Lenin down. Mao concluded that there were many counterrevolutionaries in Eastern Europe because the class struggle had not been properly waged.

Allegedly to bring the party out of conservatism and bureaucratism, Mao launched a call on May 10, 1957 to bring back the "spirit of Yan'an". Under the slogan of the Hundred Flowers Movement , which he had already used in December 1955, he granted freedom of speech and the press and called for criticism of grievances. The reaction of the population and especially of the intellectuals surprised the party, which was not prepared for serious talks. Freedom of speech was abolished as early as June 8th and the numerous “poisonous herbs” that had sprouted were eradicated. There is strong evidence that Mao deliberately provoked the critics in order to locate and prosecute the critics. Millions of intellectuals were branded as right-wing bourgeois elements and there was state terror, with which Mao also eliminated critics of his policy of the rapid construction of socialism. In the fall of 1957, at the 3rd extended plenary session, Mao described the campaign as successful and announced utopian and colossal projects in agriculture. He firmly believed in the power of socialism, because the Soviet Union had just launched the Sputnik into space, while the USA had "not even brought a potato" into space. A campaign in the party to see who could expose the most deviants in numbers was launched, and another wave of persecution swept across China.

Big leap forward

On the occasion of the celebrations for the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution, Mao visited Moscow, where he was courted by Khrushchev, who however violently and publicly attacked. He snubbed Khrushchev not only with political attacks, but also with the fact that he pondered in the presence of numerous other leaders of communist parties that a nuclear war would exterminate half of humanity, but would help communism to victory over capitalism. In response to Khrushchev's reports of the successes of his economic policies, he boasted that within 15 years China would overtake England in the amount of steel it produced.

At the party conferences in Hangzhou and Nanning , Mao criticized those who followed the model of the Soviet Union and did not want to rush forward blindly. One should not curb the enthusiasm of 600 million people. He warned the moderates that they were only 50 meters away from deviants. The “Sixty Theses on Working Methods” that were adopted at these conferences formed the theoretical basis for the great leap forward. “Three years of persistent work” became the slogan for the Maoist construction of socialism. Mao began to travel all over China and convince all party cadres that China needed to greatly increase the production of grain and steel - it is unclear why Mao used these two numbers as the sole targets for his policy. In January 1958, Mao called for permanent revolution, that is, an endless series of reforms and revolutionary campaigns. He feared that otherwise the people would become too comfortable. He called on the cadres to experiment and promised impunity for left deviants. Although Mao knew little about economics, he was aware that China's economic development had to be based on its huge supply of labor.

His first campaign was to eradicate the four plagues . Mao saw in rats , mosquitoes , flies and sparrows only pests that had to be combated. Mao had proposed this measure back in 1956, but had been ignored until then. In February 1958 it was started by decree and the whole country took part in the hunt for the animals. The killing of the birds in particular had drastic consequences for the ecological balance. The second campaign began in 1955 and consisted of expanding the cooperatives to include more than 10,000 households and mobilizing workers to build infrastructure such as canals, irrigation systems, dams or reservoirs. The ideas of deep plowing and dense planting were also spread. The calculation was that the yields in agriculture should increase sharply and that industrial development could be financed from the export proceeds from grain. In April 1958, the first such large-scale cooperative from Henan began on its own initiative to call itself the People's Commune, to offer free food in canteens and to organize the work militarily. This freed up a large number of workers and saved fuel for cooking, while at the same time it enabled the rural population to escape poverty and hunger. Mao was enthusiastic, the media spread the news of the "discovery of the People's Commune" with great zeal, and huge communes of this kind were being set up across China. Mao heralded an era of never-ending joy and in his exuberance predicted ever shorter times to catch up with England. In his opinion, municipalities should be developed into production complexes for agriculture, industry and the military and he promised that there would soon be an abundance of goods and that each district would soon have two planes.

The "Battle for Steel" was the next campaign of the great leap forward. Primitive blast furnaces were built across the country in which the surrounding vegetation was burned to make steel. To this end, metal objects that were no longer needed thanks to the people's communes were melted down and numerous workers were withdrawn from other economic sectors. In October 1958, 90 million Chinese were working on the blast furnaces, including farmers, students and doctors. This policy quickly resulted in food shortages across the country. As early as December 1958, 25 million people were starving. The bottlenecks also reached Zhongnanhai , there was no more meat. Mao accused party cadres of lying to him in February 1959, but he firmly believed in the correctness of his policies and set higher goals for 1959. In June 1959, he visited his home village and found that his parents' tombstone had been used as building material for a blast furnace and that the temple where his mother had always prayed had been demolished and burned. The metal objects had disappeared in all the houses. A few weeks later, Mao received a letter from Peng Dehuai in which Peng criticized the Great Leap very carefully. Mao was very angry and had Peng and some of his supporters like Luo Fu and Huang Kecheng removed from their posts at the Lushan Conference . In 1959 the harvest was poor and the famine deepened, but the party leadership continued to flatter Mao.

Mao also ran into a crisis in foreign policy. On July 31, 1958, Khrushchev suddenly came to Beijing on an unofficial visit to propose a joint Pacific fleet and joint radar stations to Mao. Mao was extremely hostile to Khrushchev. Not only did he completely reject Khrushchev's proposals and boast about the expected bumper harvest, he also humiliated him by negotiating with him in the swimming pool - Mao was a good swimmer, while the miner Khrushchev could barely swim. Khrushchev then met with US President Eisenhower to talk about easing tensions between the two superpowers and declared Soviet neutrality in the border war between India and China. On June 20, 1959, he withdrew the Soviet promise of aid for the construction of the atomic bomb, and in the summer of 1959 he criticized Chinese politics and especially the people's communes to other leaders of the communist camp. At the celebrations marking the 10th anniversary of the proclamation of the People's Republic, Mao and Khrushchev were openly hostile: Khrushchev suggested that Mao should show goodwill to Eisenhower and release five Americans captured in China since the Korean War , Mao accused Khrushchev of defrauding socialism and to act opportunistically. At the height of the Great Leap, the Soviet Union withdrew its 1,390 engineers and technicians from joint projects in China, which further deepened the economic crisis.

In 1960, China suffered from severe drought, so that the grain harvest was 50 million tons behind 1957. The Great Chinese Famine reached its climax, and the party leadership's families had to grow vegetables in the courtyards of Zhongnanhai and drove out of Beijing to look for something to eat. Mao allowed China to procure four million tons of grain from western countries in 1961, while Beijing turned down a Soviet offer of aid, citing alleged difficulties in the Soviet Union. At the same time, the party tried to keep the famine a secret, including inviting the Mao biographer Edgar Snow to China, who at the end of a tour of the world confirmed that the famine was a lie. It was not until the 1980s that the party leadership admitted 20 million people who had starved to death, while Western estimates put up to 50 million fatalities. Current estimates assume 20 to 45 million deaths.

In the spring of 1960, Mao admitted the failure of the Great Leap and agreed to proposals by the chairman of the state planning commission, Li Fuchun, to adjust economic policy. The people's communes were reformed in such a way that the agricultural organization practically reverted to the level of the early 1950s. Mao now viewed the public canteens as a "fatal tumor" and ordered them to be closed. He retired to the second row and now referred to Liu Shaoqi as his successor, after he had given up the office of chairman of the People's Republic in 1959. Liu tolerated the household contract system that had developed spontaneously. Direct criticism of Mao arose and grew louder, especially at the expanded Central Committee meeting in January and February 1962. While Mao withdrew to Hangzhou , the Politburo in Beijing worked out emergency economic measures. Mao sent his assistant Tian Jiaying to Hunan to gather information on the situation in the countryside - to Mao's great disappointment, the result was that the farmers demonized the Great Leap, welcomed the budget contracts and in some cases even wished for the New Democracy back.

From the results of the emergency measures - the 1962 to 1964 harvests were satisfactory - Chen Yun concluded that it was the forced amalgamations into people's communes that had caused the disaster. Deng Zihui , Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai therefore promoted the system of household contracts. In July 1962, however, Mao returned to the Central Committee and was angry with the budget contracts, warning of the return of the bourgeoisie and a degeneration as he thought it was going on in the Soviet Union. He launched a campaign that China must protect itself from external revisionism and prevent revisionism at home and gathered radical leftists like his wife Jiang Qing, Lin Biao , Zhang Chunqiao and Ke Qingshi around himself. In September 1962, Mao gave his wife power over the cultural department and the personality cult around Mao was reinforced. From 1963 the army newspaper Jiefang Ribao published a daily Mao quote, from which the well-known Mao Bible later emerged. The cult of the endlessly devoted soldier Lei Feng was promoted and communist operas by Jiang Qing supplanted the "feudal traditions". The People's Republic's first nuclear test was successful in 1964, and Khrushchev was deposed in the same year. Mao concluded from this from the correctness of his course. He visited Jinggangshan Base , from where he began his revolution, and took a new mistress, 18-year-old conductress Zhang Yufeng .

Mao's campaigns

Cultural Revolution (1966–1976)

In 1966 Mao started the great proletarian cultural revolution by supporting critical wall newspapers and calling on schoolchildren, students and workers to break through newly established social structures. With the slogan “Love for mother and father is not the same as love for Mao Zedong”, he urged children to denounce their parents as “counter-revolutionaries” or “deviants” - just as promoting denunciation was one of Mao's most effective instruments of rule. The stated aim of the campaign was to eliminate reactionary tendencies among party cadres, teachers and cultural workers. In reality, the resulting chaos was supposed to bring Mao Zedong to power again and to eliminate his internal party opponents, especially Liu Shaoqi , which Mao succeeded in doing with the help of Lin Biao and the Gang of Four . His internal party opponents were arrested for treason, killed or “rehabilitated” through physical labor. The young people incited in the course of the revolution formed so-called Red Guards . In the period that followed, the youngsters skipped schools and universities, killed and abused numerous people, especially people with education (teachers, doctors, artists, monks, party cadres), destroyed cultural monuments, temples, libraries and museums, fought one another and disrupted public order permanently .

See also: Red August

Mao Zedong, who had the power firmly under control again after the removal of Liu Shaoqi, therefore already in 1968 called on the rampaging youths to carry their “true revolutionary ideas” to the sparsely populated, rural western provinces and to consider the hard-working peasants there to take proletarian role models. Since only a few young people wanted to replace unrest in large Chinese cities with hard field work in poor western provinces, the army had to be deployed to openly fight the Red Guards and to force the newly introduced compulsory schooling. As a result, numerous Red Guards were shot in mass executions. The Cultural Revolution was only officially declared over after Mao's death in 1976 and the Gang of Four was held responsible for the unrest.

Mao's foreign policy

After Japan's invasion of China, Mao and Zhu De as commander-in-chief turned to the future British Prime Minister Clement Attlee , then chairman of the Labor Party, on November 1, 1937 , and asked him for support. Mao writes that China is in "a life and death struggle against the invaders [...] We believe that if the British people learn the truth about Japanese aggression in China, they will rise up to help the Chinese." " . The letter, written in English, ends with the sentence: "Long live the peace front of the democratic nations against fascism and the imperialist war." Attlee has not received an answer. New Zealander Munro Bertram claims to have encouraged Mao to write the letter.

In terms of foreign policy, the acceptance of the People's Republic of China into the United Nations in 1971 was Mao's greatest success. The Republic of China in Taiwan was expelled from the UN at the same time. The visit of US President Nixon in 1972 also contributed to the “bamboo curtain” becoming more permeable. After Mao suffered a first stroke that same year, Zhou brought top official Deng out of exile in February 1973.

reception

Mao cult and crime

After Mao's death, a new constitution was introduced and the " Gang of Four " were immediately arrested. Mao's widow Jiang Qing was sentenced to death on parole in a 1981 trial. The sentence was commuted to life two years later. In 1991 she was released for health reasons, and ten days later she killed herself.

After Deng Xiaoping's final rehabilitation in 1977 and diplomatic recognition by the USA on January 1, 1979, China opened its borders and rehabilitated the surviving Mao victims. The content of the Mao Bible (the "Little Red Book") was defined in 1980 as the wisdom of all Mao leadership.

In 1981 the CCP officially admitted the campaigns' failures for the first time without speaking out against Mao: The Cultural Revolution was a “gross mistake”, but overall Mao's work was rated “70 percent positive”, since the achievements more than the errors would have balanced.

Western historians discuss whether China would have experienced faster and more humane economic development without Mao. Mao continues to be worshiped in the form of mascots, pendants, statues and pictures during the economic boom since the 1980s. There are also Mao monuments in some cities, his likeness can be seen on all banknotes of the People's Republic . The “cultural revolution” has hardly been dealt with to this day.

In terms of foreign policy, China initially oriented itself towards developments in the Soviet Union during the Mao period (“leaning to one side”, yibian dao ). However, his doubts about the suitability of the Soviet model for the development and worldwide spread of communism allowed him to push ahead with the gradual break with the USSR after Stalin's death . Domestically, the time was shaped by a series of campaigns that did not begin with the Hundred Flowers Movement in 1956/1957.

The primary purpose of the permanent campaigns was to smash the bourgeois structures that were constantly forming through a permanent revolution. These purges, however, served at least as much as Mao's claim to authoritarian power, which he ruthlessly defended against all actual and supposed enemies inside and outside the party.

Scientists, including the American political scientist Rudolph Joseph Rummel , estimate the number of victims from the "Big Leap" alone at over 40 million people and reckon with a total of up to 76 million deaths (RJ Rummel). According to Rummels and Heinsohn's number of victims, there are:

- Consolidation of power and expropriations 1949–1953: 8,427,000 deaths

- “ Big leap forward ” and expropriations 1954–1958: 20 to 40 million victims

- Extermination through work (labor camp) and hunger as a result of the expropriations 1959–1963: 10,729,000

- Cultural Revolution 1964–1975: 7,731,000 dead (according to Rummel), 400,000 to 1 million (according to the Black Book of Communism )

The Dutch sinologist and historian Frank Dikötter determined at least an additional 45 million deaths in the years 1958 to 1962 as a result of Mao's failed policies by evaluating meticulous reports by the security services from that time.

The Maoism as a political movement was influential not only in China but also influenced the European student movement in 1968 , the Naxalites in India, the guerrilla movement Shining Path in Peru, the Communist Party of the Philippines and numerous other parties, groups and factions. Some young people in the West saw Mao's radical action against the bourgeoisie as a model for combating “ bourgeois ” structures worldwide.

Large monuments have been erected in honor of Mao to this day (2016). In total there are an estimated 2,000 Mao statues in China.

Classification and coming to terms with the past

Historical assessments of Mao outside the People's Republic were increasingly shaped by dismantling the myths surrounding the Great Chairman . In addition to the political achievements (which, however, fell in the early days of the communist takeover), such as the establishment of China as a state independent of colonial powers and the stabilization of the country after 30 years of armed conflict, the dark side of its dictatorship was highlighted. During the entire thirty-year rule of Mao, the PR China was an economically depressed country, marked by political persecution and largely isolated in terms of foreign policy until 1972.

In China, after his death, Mao's work was officially judged by his successors according to the "Deng formula"; H. 70% of his actions were good for China and 30% bad.

Cinematic reception

- Peter Adler: Mao Zedong - A 30-year catastrophe. The Mao dictatorship in testimony from contemporary witnesses and historians. in the series The Great Dictators. ZDF , 2006, 45 min.

plant

The publication of the works of Máo Zédong is still a sensitive issue. Four volumes of “Selected Works” ( Máo Zédōng Xuǎnjí “毛泽东 选集”) were compiled in the early 1950s and published in Chinese. They are still considered a canonical compilation and were translated into several languages (including German) and published by the publishing house for foreign language literature in Beijing at the end of the 1960s. However, these four volumes only contain writings from 1926 to 1945 (Dietz Verlag Berlin), or 1949 (Verlag für foreign language literature, Beijing). They were previously published in German by Dietz Verlag Berlin (1955).

- Mao Tse-tung: Selected Works. Publishing house for foreign language literature, Beijing 1968/69; Dietz Verlag Berlin 1955, four volumes.

More of Máo's works appeared in Chinese magazines and newspapers and were distributed in the form of brochures in various languages.

During the Cultural Revolution, several edited volumes of speeches and articles by Máo Zédōng appeared, but they were not freely sold. The best-known collection is entitled "Long live the Maozedong ideas". In 2005 a samizdat reproduction of this edition was published.

- Máo Zédōng Sīxiǎng Wànsuì. Nèibù Xuéxí, Bùdé Wàichuán. «毛泽东 思想 万岁» 内部 学习 • 不得 外传 Beijing 2005. Volume 1: 1913–1943. Volume 2: 1943-1949. Volume 3: 1949-1957. Volume 4: 1958-1960. Volume 5: 1961-1968. Volume 6: 1968-1976. ISBN 978-7-05-000010-5 .

Some of Máo Zédōng's works from this collection were translated into German by the German sinologist Helmut Martin and published in 1974 as a book under the title “Mao intern”. Previously, a book with other unpublished writings of Máos had already appeared under the title "Mao papers", which also contained other works from "Long live the Maozedong ideas". It was edited by Jerome Chen . In 1982 Helmut Martin published a critical edition of Máos works - also in Chinese and German - which shows how much the “official” Chinese editions were shortened and changed.

- Helmut Martin (Ed.): Mao intern. Hanser, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-423-01250-1 .

- Jerome Chen: Mao papers. Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, Munich 1972, ISBN 3-485-01823-6 .

- Helmut Martin (Ed.): Mao Zedong texts. 6 volumes. Hanser, Munich / Vienna 1982, ISBN 3-446-12474-8 .

In April 1977 a fifth volume of the “Selected Works” was published in China. This volume was also translated within a short time by the publishing house for foreign language literature and was also published in German. It contains writings of Máos from the period between 1949 and 1957. This volume was compiled under the direction of Huà Guófēng . The "Gang of Four" had already overthrown, but Mao's services during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution are praised in the foreword . When Dèng Xiǎopíng came to power, this volume was pulped again and the editorial committee for Volume VI disbanded.

- Mao Tsetung: Selected Works, Volume V. Publishing House for Foreign Language Literature, Beijing 1978.

From 1987 to 1998 a 13-volume edition was published in China, which supposedly contains all of Mo's works from 1949 to 1976. However, this edition is marked “for internal use only” and in theory may not be sold openly.