Francesco Patrizi da Cherso

Francesco Patrizi da Cherso (also Patrizzi , Patricio , Latinized Franciscus Patricius , Croatian Frane Petrić , Franjo Petrić or also Franjo Petriš ; born April 25, 1529 in Cres ; † February 7, 1597 in Rome ) was a Venetian humanist , philosopher , writer, Literary , political and historical theorist , military scientistand poet of Croatian descent.

Patrizi studied Aristotelian philosophy at the University of Padua , but turned to Platonism while still a student . He became a sharp, high-profile opponent of Aristotelianism, which he dealt with extensively in extensive writings. After many years of unsuccessful efforts to secure a permanent material existence, he finally received an invitation to the ducal court of the Este in Ferrara in 1577 . At the university there , a chair for Platonic philosophy was set up especially for him. In the years that followed he gained respect as a professor, but also involved himself in scientific and literary controversies; he was prone to polemics and was himself violently attacked by opponents. In 1592 he accepted an invitation to Rome, where thanks to papal favor a new chair was created for him. The last years of his life were darkened by a serious conflict with the ecclesiastical censorship authorities , which banned his main work, the Nova de universis philosophia .

One of the last Renaissance humanists, Patrizi was distinguished by a broad education, varied scholarly activity, a strong will to innovate, and exceptional literary fertility. He critically examined established, universally accepted teachings and proposed alternatives. In particular, he wanted to replace the prevailing Aristotelian philosophy of nature with his own model. He opposed the traditional view of the meaning of historical studies, which was narrowed down to moral instruction, with his concept of a broad, neutral, scientific historical research. In poetry he emphasized the importance of inspiration and fought against conventional rules, which he saw as arbitrary, unreal restrictions on creative freedom.

In the early modern period , despite the condemnation of the church, Patricius' highly controversial natural philosophy found considerable support, but remained an outsider's position. Modern research appreciates his contributions to the constitution of the modern concept of space and to the theory of history.

origin and name

Francesco Patrizi came from the town of Cres on the island of the same name off Istria (Italian : Cherso ). The island was then part of the Republic of Venice , but a large part of its population was Croatian. Francesco was an illegitimate son of the priest Stefano di Niccolò di Antonio Patrizi (Petrić), who belonged to the lower nobility. His mother was Stefano's partner Maria Radocca. In older specialist literature, Francesco's father was mistakenly identified with the judge of the same name, Stefano di Niccolò di Matteo Patrizi, and his mother Maria was equated with Maria Lupetino, the alleged wife of the judge. The claim that the philosopher is related to the famous theologian Matthias Flacius , which is related to the erroneous genealogy, is also inaccurate .

According to Francesco, his family was originally based in Bosnia and, according to their coat of arms, was of royal descent. As a result of the Turkish conquest of her homeland, she emigrated, and that is how an ancestor named Stefanello came to Cres. This happened, if the report is correct, in the second half of the 15th century.

Following a humanistic custom, the philosopher Latinized his name and called himself Patricius or Patritius . Since he lived in Italy and published his works there, the form of the name Francesco Patrizi has prevailed internationally, but variants of the Croatian form are preferred in Croatia. The addition "da Cherso" (from Cres) serves to distinguish it from the humanist Francesco Patrizi (Franciscus Patricius Senensis), who came from Siena and lived in the 15th century.

Life

youth and study time

Francesco Patrizi was born on April 25, 1529 in Cres. He spent his childhood in his hometown. In February 1538, his uncle Giovanni Giorgio Patrizi, who commanded a Venetian warship, took the boy, who was only nine years old, on a campaign against the Turks. So it happened that Francesco took part in the naval battle of Preveza , in which the Christian fleet was defeated. He almost ended up in Turkish captivity. He spent several years at sea. In September 1543 he went to Venice to acquire a professional qualification. Initially, he attended a commercial school at the will of Giovanni Giorgio, but his inclination was towards humanism. Since his father showed understanding, the youngster received Latin lessons. His father later sent him to study in Ingolstadt , where the Bavarian University was based at the time. There he learned Greek. In 1546, however, he had to leave Bavaria because of the turmoil of the Schmalkaldic War .

In May 1547 Patrizi went to Padua , whose university was one of the most prestigious in Europe. Initially, at the request of his practical father Stefano, he studied medicine with Giambattista Montano , Bassiano Lando and Alberto Gabriele, albeit very reluctantly. When Stefano died in 1551, he was able to break off his medical training. He sold the medical books. He continued to be interested in humanistic education. During his studies he attended philosophical lectures by professors Bernardino Tomitano, Marcantonio de' Passeri (Marcantonio Genova), Lazzaro Buonamici and Francesco Robortello . Among his friends and fellow students was Niccolò Sfondrati, who later became Pope Gregory XIV . The philosophy classes were a disappointment for Patricius, because Padua was then a stronghold of Aristotelianism , whose representatives continued the tradition of medieval scholasticism . This was a direction that Patricius firmly rejected and later fiercely opposed. Under the influence of a Franciscan scholar, he turned to Platonism . The Franciscan recommended him the Neoplatonic teachings of the humanist Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499). The reading of Ficino's writings, especially his major philosophical-theological work, the Theologia Platonica , became groundbreaking for Patrizi. He later expressed his distance from Padua's scholastic-Aristotelian teaching establishment by describing himself as an autodidact in an autobiographical letter in 1587 . During his student days he already wrote and published philosophical and philological writings; in 1553 he had a collection of his youthful works printed in Venice.

First attempts at securing a livelihood (1554–1560)

In 1554 Patrizi had to return to Cres because of a protracted inheritance dispute with his uncle Giovanni Giorgio. There he experienced an unpleasant time, marked by illness, isolation and family conflict. Apparently he belonged at that time - at least until 1560 - to the clergy. In order to secure his livelihood permanently, he tried in vain to obtain a church benefice at home. After this failure he went to Rome in 1556, but his efforts to secure a benefice failed there too. Then he moved to Venice. The young scholar unsuccessfully sought employment at the splendid court of the House of Este in Ferrara . At least he gained a foothold in Venetian humanist circles: he joined the Accademia della Fama, a scholarly community in which he found like-minded people.

Activities in Cyprus (1560–1568)

In 1560 the philosopher entered the service of the nobleman Giorgio Contarini, who belonged to one of the most distinguished families in Venice. First he had to give his employer lessons in Aristotelian ethics. Patrizi soon gained Contarini's trust and received an important commission: he was sent to Cyprus to inspect and then report to the family estate, which was managed by one of Contarini's brothers. When he described the conditions he found after his return in the summer of 1562, Contarini sent him back to Cyprus and gave him authority to carry out improvement measures. As the new administrator, Patrizi ensured a significant increase in the value of the land through melioration , which could now be used for cotton cultivation. However, the necessary measures were expensive, and bad harvests also reduced income, so that the customer could not be satisfied. Contarini's Cypriot relatives, whom Patrizi had discredited with his report, took this opportunity to take revenge and blacken the administrator to the head of the family. When Patricius' justification was not accepted, he asked for his dismissal in 1567.

In the period that followed, Patrizi initially stayed in Cyprus. He now entered the service of the Catholic Archbishop of Nicosia , the Venetian Filippo Mocenigo, who entrusted him with the administration of the villages belonging to the Archdiocese. But already in 1568 he left the island threatened by the Turks together with the archbishop and went to Venice. Looking back, he saw the years in Cyprus as lost time. After all, he used his stay in the Greek-speaking area for an important humanistic concern: he searched with considerable success for Greek manuscripts, which he then bought or had copied, perhaps also copied himself.

Alternating efforts to secure a material livelihood (1568–1577)

After his return, Patrizi turned to science again. He now went again to Padua, where he apparently no longer worked at the university, but only gave private lessons. Among his students was Zaccaria Mocenigo, a nephew of the archbishop. Very important to him was the fruitful exchange of ideas with the well-known philosopher Bernardino Telesio , with whom he later corresponded.

During this time Patricius' relationship with the archbishop deteriorated. He now made contact with Diego Hurtado de Mendoza y de la Cerda, Viceroy of Catalonia , who was an avid book collector. The beginning of this connection was promising: the viceroy invited him to Barcelona and promised him a position as court philosopher with an annual salary of five hundred ducats . Patrizi then undertook his first trip to Spain. In Barcelona, however, he suffered a severe disappointment when the financial promise was not kept. Under these circumstances, the philosopher was forced to return home in 1569.

One benefit of the trip, however, was the prospect of making a living in the long-distance trade in books. Exporting books from Italy to Barcelona seemed lucrative, and Patrizi had been able to make a corresponding agreement with local business partners before he left. Dispatch got underway and did indeed prove worthwhile at first, but the venture eventually foundered due to the philosopher's inexperience and lack of business acumen. Patrizi suffered a severe blow in 1570 when the Turks in Cyprus captured a shipment of goods that belonged to him and were intended for export to Venice, for which he had paid 3,500 ducats. This put him in such distress that he turned to his former employer Contarini, who in his opinion still owed him 200 ducats. When he refused to pay, a lengthy process ensued, which Patrizi apparently lost.

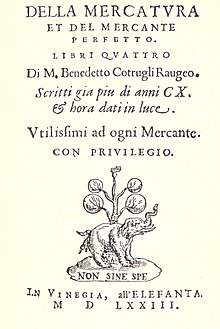

In order to rehabilitate his finances, Patrizi turned to book production. In August 1571 he contracted with the heiress to the manuscript of a treatise on emblems by the late scholar Girolamo Ruscelli , Le imprese illustri . He took over as editor and the work was published by a Venetian printer the following year. However, Patrizi was unable to meet his contractual obligations due to his precarious financial situation. This resulted in a conflict that was difficult to resolve. After this unpleasant experience, Patrizi founded his own publishing house, all'Elefanta . There he brought out three books in 1573, but then the publishing house went under. The philosopher then made a new trip to Spain in 1574 to sue his former business partners and sell Greek manuscripts. In February 1575 he was received by Antonio Gracián, secretary to King Philip II , who bought 75 codices from him for the royal library in the Escorial . From a humanist point of view, however, this commercial success was questionable, because the Escorial was considered a "book grave" by scholars. When the court proceedings about the failed book trade dragged on without any foreseeable result, Patrizi returned home after thirteen months.

On his return, Patrizi settled in Modena in 1577 , where he entered the service of the distinguished musician and poet Tarquinia Molza , to whom he taught Greek.

Professorship in Ferrara (1578–1592)

In Modena, Patrizi received the invitation to the ducal court of Ferrara that he had been aspiring to for two decades. At the turn of the year 1577/1578 he arrived in Ferrara. He was well received by Duke Alfonso II d'Este , an important patron of culture . His advocate there was the ducal council - from 1579 secretary - Antonio Montecatini, who valued him very much, although he was a representative of the Aristotelianism fought by Patrizi from a platonic perspective. At the suggestion of Montecatini, a chair in Platonic philosophy was set up especially for Patrizi at the University of Ferrara . The starting salary of 390 lire was later increased to 500 lire. The time of material worries was over.

With the move to Ferrara, a pleasant and fruitful phase of life began for the new professor. He was held in high esteem both at Alfonso's glamorous court and in the academic community. He was friends with the duke. Patrizi also had a good personal relationship with the famous poet Torquato Tasso , who lived in Ferrara, although he had a difference of opinion with him in a controversial controversy. During the fourteen years he worked in Ferrara he published numerous writings.

However, the dedicated statements made by patricians on philosophical and literary issues also provoked opposition and led to arguments. A written polemic with the Aristotelian Teodoro Angelucci broke out over the criticism of Aristotle. In the literary field, Patrizi engaged in a dispute about the criteria of poetic quality, in which Camillo Pellegrino and Torquato Tasso took the opposite view.

Professorship in Rome, conflict with censorship and death (1592–1597)

Patricius' academic career finally reached its peak thanks to the goodwill of Cardinal Ippolito Aldobrandini, who invited him to Rome in October 1591. In January 1592 Aldobrandini was elected Pope and took the name Clement VIII . He gave an enthusiastic welcome to the scholar, who arrived in Rome on April 18, 1592. At the Roman University of La Sapienza , a chair in Platonic philosophy was created for Patrizi. The professor resided in the house of Cinzio Passeri Aldobrandini , who was a nephew of the Pope and a well-known patron of the arts and was made a cardinal in 1593. On May 15, he gave his inaugural lecture on Plato's Timaeus in front of a large audience . The remuneration granted to him - 500 ducats basic salary, with allowances a good 840 ducats - was the highest at the Sapienza. It was a sign of the special papal favor bestowed on the Platonist. Among his listeners and interlocutors was Torquato Tasso, now living in Rome, who did not hold grudges against him for the dispute in Ferrara.

Despite his excellent relationship with the pope, Patrizi was soon targeted by church censorship. His major philosophical work Nova de universis philosophia , which he had published in Ferrara in 1591, provided the occasion . There, the censor Pedro Juan Saragoza discovered a series of statements that he considered heretical or at least suspicious and denounced in a report. Among other things, he declared the assertion that the earth rotates to be erroneous, because this was incompatible with the Holy Scriptures. According to the consensus of theologians, the Bible tells us that the heavens of fixed stars revolve around the immovable earth.

In October 1592 the Index Congregation, the authority responsible for the Index of Prohibited Books , became active. She summoned the author of the suspect writing in November 1592 and allowed him to read Saragoza's expert opinion, which was an unusual accommodation towards the accused at the time. Patrizi reacted to the censor's attack with a defence, the Apologia ad censuram , in which he professed his submission in principle, but aggressively defended his position on the matter and accused Saragoza of incompetence. He met with no understanding. He later tried unsuccessfully to satisfy the panel with written explanations of his doctrine and concessions. Even after the congregation decided in December 1592 to cite the Nova de universis philosophia in the revised index, the author continued his rescue efforts while the publication of the new 1593 index was delayed. The fact that the last responsible censor, the Jesuit Francisco Toledo , was a well-known representative of the scholastic Aristotelianism that Patrizi fought against had an especially unfavorable effect . In July 1594 the Congregation imposed an absolute ban on the distribution and reading of the work and ordered the destruction of all copies that could be found. In the updated edition of the Index, which appeared in 1596, and in subsequent editions, the writing was cited. However, it was expressly left to the author to submit an amended version for approval. The aged philosopher, worn down by the conflict, began the revision but was unable to complete it, for he died of a fever on February 7, 1597. He was buried in the Roman church of Sant'Onofrio al Gianicolo next to Torquato Tasso.

factories

Most of Patricius' writings are in Italian, the rest in Latin. The Latin part of the oeuvre includes two monumental works in particular: the Discussiones peripateticae , an extensive pamphlet against Aristotelianism, and the Nova de universis philosophia , the unfinished overall presentation of his teachings.

Anti-Aristotelian writings

Discussiones peripateticae

The fight against Aristotelianism was a central concern of Patricius, which appears throughout his texts. He not only wanted to refute individual teachings of the ancient thinker, but to bring down his entire system. Especially for this purpose he wrote a polemical writing, which he called Discussiones peripateticae (Peripatetic Investigations) , with which he referred to the Peripatos , the philosophical school of Aristotle, referring. The first impetus for this came from a wish from his student Zaccaria Mocenigo, who asked him to write a history of Aristotle. Patricius fulfilled this request with the original version of the Discussiones , a critical examination of the life and works of the Greek philosopher, which he published in Venice in 1571. After a long break, he later took up the systematic analysis of Aristotelianism again and expanded his original text into a comprehensive critique of the Peripatetic worldview. In this expansion of the project, the Discussiones printed in 1571 were included as the first volume in a four-volume complete work, which Patrizi had printed in folio format by Pietro Perna in Basel in 1581. In doing so, he presented a polemical writing that was also designed as a handbook of Aristotelianism.

The first volume consists of thirteen books. The first book offers a detailed biography of Aristotle, the second a catalog raisonné. The following seven books contain philological investigations. There it is about clarifying the questions of which of the writings traditionally attributed to Aristotle actually come from him, which work titles are authentic and how the writings are to be arranged systematically. Patrizi defines a series of stylistic, content-related and historical criteria for distinguishing between genuine and fake writings. Particular attention is paid to the fragments from the Greek thinker's lost works, which have survived in later ancient literature. They are assembled in large numbers. The tenth book deals with the reception history. The last three books are devoted to the various methods that come into consideration for the interpretation of the doctrine and for an Aristotelian philosophizing.

In the second volume, Patrizi compares the Peripatetic philosophy with older doctrines, especially Platonism. His intention is to discredit Aristotle as a plagiarist and compiler . He expresses himself carefully, however, since this volume is dedicated to his friend and colleague Antonio Montecatino, professor of Aristotelian philosophy in Ferrara. A contrast to this is offered by the open, violent polemics in the last two volumes, in which the author gives up his reserve. The third volume presents the Peripatetic teachings as incompatible with those of the pre- Socratics and Plato . Patrizi discusses the disagreements between the authorities through a wealth of contradictory statements, always declaring Aristotle's view to be wrong. From his point of view, Aristotelianism is an intellectual-historical phenomenon of decay, a falsification and destruction of the knowledge of earlier thinkers. The fourth book serves to prove errors in Aristotelian natural philosophy.

When dealing with peripatetic thinking, Patricius attaches great importance to taking Aristotle's doctrinal opinions directly from his own words and not - as has been customary since the Middle Ages - to being influenced by the interpretations of numerous commentators. In addition, he demands that Aristotle's view should not be substantiated by a single statement, as has been the case up to now, but that all relevant statements of the philosopher should be used. In the Discussiones peripateticae , Patrizi does not consistently assume a Platonic alternative system to Aristotelianism, but also makes use of arguments based on non-Platonic, rather nominalistic and empiricist ideas. In terms of the history of philosophy, he sees a fateful development: Aristotle's first students still thought independently and even contradicted their teacher; later, however, Alexander von Aphrodisias gave himself unreservedly to the founder of the school and thus renounced free thinking. The first medieval Arabic-language interpreters, Avicenna , Avempace , and Alfarabi , were relatively unbiased, but then Averroes proclaimed the absolute authority of Aristotle, paving the way for sterile scholastic Aristotelianism.

Controversy with Teodoro Angelucci

The scathing judgment on Aristotelian philosophy in the Discussiones peripateticae led to a controversy with the Aristotelian Teodoro Angelucci. He reacted to the Discussiones with a counter-writing in which he sharply criticized Patricius' statements on metaphysics and natural science. The attacked responded with the Apologia contra calumnias Theodori Angelutii (defense against the slanders of Teodoro Angelucci) , which he had printed in 1584. The following year, Angelucci continued the argument with another pamphlet, the Exercitationes (Exercises) .

Metaphysics, natural philosophy, mathematics and number symbolism

Preliminary work on the system of the "new philosophy"

In the 1580s Patricius dealt with preparatory work for an overall presentation of his philosophical system, which he conceived as an alternative to Aristotelianism. First, he provided relevant material. He translated the commentary by Pseudo- Johannes Philoponos on Aristotle's metaphysics and the Elementatio physica and the Elementatio theologica of the late antique Neoplatonist Proclus into Latin. Both translations were printed in 1583. Then Patrizi worked out his theory of space. In the treatise Della nuova geometria , completed in 1586, which he dedicated to Duke Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy, he presented a new basis for geometry, which he preferred to Euclidean definitions. In 1587 a Latin exposition of his understanding of spatiality appeared as the first part of a Philosophia de rerum natura (Philosophy Concerning the Nature of Things) . This publication consists of the two books De spacio physico (On physical space) and De spacio mathematico (On mathematical space) . There he presented his alternative to Aristotelian cosmology and physics.

As part of this preliminary work, Patricius' work Zoroaster et eius CCCXX oracula Chaldaica (Zarathustra and his 320 Chaldean oracles) was created, the first independent modern collection of fragments of the Chaldean oracles . He believed that these were authentic teachings of Zarathustra and that the oracles were the oldest testimony in the history of philosophical thought. It was therefore important to him to secure the text. He took the passages from the works of the late antique authors Proclus , Damaskios , Simplikios , Olympiodoros and Synesios . His collection, comprising 318 oracular verses, was a vast expansion of the previously authoritative compilation of the Georgios Gemistos Plethon , which contains only sixty hexameters .

Nova de universe philosophia

Patricius' main work, the Nova de universis philosophia (New philosophy about things in their entirety) , was to consist of eight parts according to his plan and should present his entire interpretation of the world. But he was only able to complete the first four parts and publish them in Ferrara in 1591. He worked on another part, De humana philosophia , in 1591/1592, but the manuscript remained unfinished, and the conflict with the censorship authorities prevented it from being completed and published. The author dedicated the first edition of 1591 to Pope Gregory XIV , with whom he had a childhood friendship from his student days in Padua.

In the preface, Patrizi recommended to the Pope a far-reaching revolution in the Catholic school system: He suggested replacing the Aristotelianism that had been dominant since the Middle Ages with an alternative world view, that of the dominant school philosophy, in the teaching of church educational institutions - the religious schools and universities under papal control be superior There are five models to consider. The first is his own system according to the Nova de universis philosophia , the second is Zoroastrianism , the third is Hermetics , the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus , the fourth is an allegedly ancient Egyptian philosophy - meaning the teachings of the Theologia Aristotelis, which was wrongly attributed to Aristotle -, the fifth the Platonism. He reconstructed, ordered and explained the four older philosophies. All five models are conducive to religion and acceptable from a Catholic perspective, in contrast to Aristotelianism, which is godless and incompatible with faith. The church fathers of antiquity would have already recognized that Platonism corresponded to Christianity . Nonetheless, Aristotelian philosophy prevailed. Their continued dominance goes back to the medieval scholastics. The works of Plato were unknown to them, so they turned to the useless writings of Aristotle.

In the preface, Patricius provocatively criticized the actions of the Counter-Reformation church, which tried to secure belief in its teachings by means of censorship, the Inquisition and state violence. He strongly recommended relying on reason and the persuasiveness of philosophical argument rather than on coercion.

The first part of the scripture, entitled Panaugia ( All -enlightenment or All- Splendour ), deals with the principle of light, presented as the formative and animating force in the universe, and with physical light and its properties. Among other things, the reflection and refraction of light and the nature of colors are discussed . The second part is called Panarchia ( all- rule or all- causality ). This is a neologism of the author, derived from the Greek noun archḗ (“origin”, “cause”, “rule”), which refers to the hierarchical world order and its divine source. The Panarchia describes the emanation - the gradual outpouring of entities from their divine source - and the resulting hierarchy in the universe. The third part is entitled Pampsychia (All Souls) . There the philosopher presents his concept of the animation of the entire physical cosmos through the world soul and discusses in particular the souls of animals. In the fourth part, the Pancosmia (universal order) , topics of physical cosmology are discussed, in particular the question of the spatial expansion of the universe, which Patrizi considers infinite.

Attached as appendices are, in addition to source texts, two digressions by the author on specific subjects: an attempt to determine the order of Plato's dialogues and a compilation of contrasts between Aristotelian and Platonic philosophy. The source texts are Patrizi's collection of fragments of the Chaldean oracles, Hermetic literature and the Theologia Aristotelis , referred to as the "mystical philosophy of the Egyptians" , a pseudo-Aristotelian writing, the content of which Patrizi equated with the " unwritten teaching " of Plato, which was only presented orally. He said it was a record of wisdom teachings of ancient Egyptian origin made by Aristotle that Plato had conveyed to his students in class.

Despite his great respect for the authors of the ancient wisdom teachings, Patricius did not hesitate to express a different opinion in individual cases. He stressed the need for solid evidence and refused to accept citations from reputable authorities as a substitute for missing arguments. He saw his task as providing arguments for what was not sufficiently founded in the traditional texts of the ancient sages.

De numerorum mysteriis

The writing De numerorum mysteriis (On the Secrets of Numbers) , which Patrizi wrote in 1594 on behalf of Cardinal Federico Borromeo , deals with number symbolism according to the Pythagorean theory of numbers . It has been handed down in manuscript, but has remained unedited .

State theory, historical theory and military science

La citta felice

La città felice (The happy city) is an early work of the philosopher, which he wrote as a student, completed in 1551 and had it printed in Venice in 1553. The treatise is intended to show the conditions for a successful life in an ideal state community. The starting point is formed by the relevant considerations in the politics of Aristotle, whose views the young humanist still largely follows. In addition, however, the influence of Platonism is already recognizable. Material from Stoic literature is also used in the model of the state, and the influence of Niccolò Machiavelli is also noticeable.

Della historia diece dialoghi

Patrizi was one of the pioneers of historical theory , a branch of research that was still young at the time. Ten dialogues by the Venetian scholar, which he published in 1560 under the title Della historia diece dialoghi , deal with the basics of historical philosophy and the methods of historical research . The fictional dialogues take place in Venice among friends and acquaintances of the author, he himself is always there. The participants in the discussion represent different opinions in speech and counter-speech. Her arguments are presented in a manner consistent with the natural course of conversation, with frequent interruptions and digressions, irony, doubt, mockery, and a wealth of witty remarks.

La militia romana by Polibio, by Tito Livio, and by Dionigi Alicarnaseo

The treatise La militia romana di Polibio, di Tito Livio, e di Dionigi Alicarnaseo (Roman warfare according to Polybius , Titus Livius and Dionysius of Halicarnassus ) , which Patrizi wrote in 1573, was not printed until ten years later. It is strongly inspired by Machiavelli's ideas. The starting point is the thesis that the art of war is the basis of peace and a prerequisite for human happiness. Decisive is the warfare of the ancient Romans, which is superior to all others, especially the Turkish. You have to stick to this example, because if you succeed in regaining the old Roman clout, you no longer need to fear the Turks. The only one who has come close to succeeding in this so far is Duke Alfonso I d'Este , who is the unrivaled role model of all other rulers as a general, as well as in siege technology and fortress construction. With this flattery, Patrizi wanted to impress Duke Alfonso II d'Este, Alfonso I's grandson, who was reigning in Ferrara at the time. He dedicated his writing to him.

Paralleli militari

The Paralleli militari (Military Comparisons) , printed in two parts in 1594 and 1595, are Patricius' last publication. They contain the balance of his reflections in the face of Italy's political and military crisis in the late 16th century. He claimed that with his theory of warfare he could instruct the military in their own field. For this purpose he sent his writing to the well-known commanders of the troops Ferrante Gonzaga, Francesco Maria II della Rovere and Alfonso II d'Este.

literary studies

Discorso della diversità de' furori poetici

The Discorso della diversità de' furori poetici (Discourse on the Diversity of Poetic Emotions) , an early work of Patricius, printed in 1553, deals with the origin and the different products of poetic inspiration. The author deals with the controversial relationship between inspired work in a state of emotion and learned verse technique based on traditional norms and patterns. According to the discorso concept , the inspired poet is a creator who follows his impulses without being bound by rules; his art cannot be learned, but is a divine gift. Following the poetics of the Roman poet Horace , the humanistic theorist assumes that ingegno and furore work together in poetic production. By ingegno he understands individual inclination, talent and especially mental agility, by furore the inspiration by the divine muses . Thanks to the interplay of these factors, the poet attains a privileged relationship with the deity, which makes him seem sick and mad from the perspective of uncomprehending people. However, Patrizi concedes that the reception of other people's works, erudition and practice could also make a contribution to success.

Lettura sopra il sonetto del Petrarch "La gola, e'l sonno, e l'ociose piume"

This writing is also one of Patricius' youthful works, printed as early as 1553. Here he analyzes the sonnet La gola, e'l sonno, e l'ociose piume by the famous poet Francesco Petrarch from a philosophical perspective , giving it a symbolic meaning in the context of Plato's doctrine of the soul .

Della retorica dialoghi dieci

Patricius' ten dialogues on rhetoric were printed in Venice in 1562. They are dedicated to Cardinal Niccolò Sfondrati, later Pope Gregory XIV. Each dialogue is named after one of the participants in the conversation. The author himself is involved in all discussions. The writing opposes the opinion, which is widespread in humanist circles and is based on the view of Aristotle and Cicero , that rhetoric is an art of persuasion required for any knowledge transfer. Patrizi sees this as an overestimation of this discipline, which he considers a means of deception and is skeptical about. He describes it as a mere technique of dealing with the means of linguistic expression without any inner connection to truth and reality. Since the principle of rhetoric is unknown and since it deals with the probable and not with the true, it cannot be called a science in the current state of knowledge, although the possibility of future scientific rhetoric remains open.

Other themes of the rhetoric writing are the emergence of language and the power of words. The author believes that in a mythical past the spoken word possessed magical power. The later introduced control of minds with the art of persuasion is only a faint echo of this original power, because mankind has lost the former connection with the truth. Patrizi paints a culturally pessimistic picture of human history, emphasizing fear as a key factor that led to the deplorable state of civilization of his time and that dominated social life. He places the emergence and history of rhetoric in the context of this decline.

Parere in difesa dell'Ariosto

The publication of the final version of Torquato Tasso's epic poem La Gerusalemme liberata in 1581 caused a lively controversy in Ferrara. Tasso's admirers faced a group of literary critics for whom Ariosto's Orlando furioso represented the definitive model. After the poet Camillo Pellegrino had made disparaging remarks about Ariosto's treatment of the subject, Patrizi intervened in the debate in 1585 with a polemic. In his statement, entitled Parere in difesa dell'Ariosto , he praised the independence of Ariosto, who neither imitated the epics of Homer nor followed the rules of Aristotle's Poetics. Based on the current controversy, Patrizi wanted to show the uselessness of the established Aristotelian theory of poetry. Among other things, he asserted that Homer, like Ariosto, had not followed the rules of this poetics. Tasso responded immediately with a reply in which he defended the conventional principles.

Poetica

The Poetica is a large-scale presentation of Patricius' theory of poetry, an alternative to Aristotle's Poetics . It comprises seven volumes, which are called Decades because they each consist of ten books. The first two decades, the Deca istoriale and the Deca disputata , were printed in 1586. The Deca istoriale offers a detailed description of the poetic products of antiquity and the forms of their public reception. The inventory is followed by classification, study of metrics , and presentation of the presentation of poetry in cultural life. One thesis put forward here is that the actors always sang in the performances of tragedy in ancient Greece. The second decade deals with the theory. It concludes with an examination of Torquato Tasso's understanding of poetic quality. Patrizi called this part of his work Trimerone (three-day work) because it took three days to write it. The remaining five decades, which were lost in the early modern period, were only discovered in 1949 and published in 1969/1971.

Controversy with Jacopo Mazzoni

Patrizi had an intensive discussion with the scholar Jacopo Mazzoni , who contradicted him on a philological question. It was about the lost work Daphnis or Lityerses by the Hellenistic poet Sositheos , which was probably a satyr play . Patrizi wrongly believed that Daphnis and Lityerses were the titles of two tragedies by Sositheos, while Mazzoni - also wrongly - assumed it was an eclogue entitled Daphnis and Lityerses . In 1587 Patrizi responded to Mazzoni's criticism of his hypothesis with a reply, the Risposta di Francesco Patrizi a due opposizioni fattegli dal Signor Giacopo Mazzoni (Reply to two objections by Mr. Jacopo Mazzoni) , whereupon Mazzoni published a reply, to which Patrizi in turn published a new one Reply replied, the Difesa di Francesco Patrizi dalle cento accuse dategli dal Signor Iacopo Mazzoni (defense of Francesco Patrizi against the hundred accusations made against him by Mr Jacopo Mazzoni) .

eroticism

Discorsi et argomenti on Luca Contile's sonnets

Patrizi was friends with the poet Luca Contile . When he published an edition of his friend's collected poetic works in Venice in 1560, he accompanied it with his discorsi et argomenti , introductory and explanatory texts in which he presented a philosophical basis for love poetry. In doing so, he continued the treatment of the eros theme in Plato's Dialogue Symposium and gave his dear friend Tarquinia Molza the role of Plato's famous literary character Diotima , who imparts the essential knowledge about love. He compared ancient love poetry with that of the Renaissance . After treating the theory, he went into the poetic implementation of the philosophical thoughts and commented on fifty sonnets contiles.

Il Delfino overo Del bacio

It is disputed when Patrizi wrote the dialogue Il Delfino overo Del bacio (Delfino or About the Kiss) . He did not publish it; the work was not made accessible in print until 1975, when the critical first edition appeared. The interlocutors are the author and an unidentifiable Angelo Delfino, after whom the work is named. Delfino is probably a member of the important Venetian noble family of Dolfin . The starting point is a question that the young Delfino asks the reclusive Patricius: he wants to find out what the reason for the "sweetness" of the kiss is. He has not found anything about it in love literature; she ignores the kiss as if it were irrelevant to love. The two men discuss the different types of kissing and their effects, and Patrizi gives a detailed physiological explanation that satisfies the questioner. In doing so, he addresses the different erotic sensibilities of individual parts of the body and rehabilitates the sense of touch, which Marsilio Ficino judged disparagingly. Finally, the grateful Delfino directs a prayer to the “extremely powerful” god of love , Cupid .

L'amorosa filosofia

L'amorosa filosofia belongs to the genre of love treatises, the trattati d'amore , which were extremely popular in Italy in the 16th century . It is a treatise on female attractiveness and love that Patrizi wrote in Modena in 1577 but did not publish. The incomplete surviving, apparently unfinished work was only edited in 1963 on the basis of the author's handwritten manuscript. It consists of four dialogues. The interlocutors are a number of people, including the author and Bernardino Telesio as the central figure, Tarquinia Molza. In the first dialogue, which makes up about half of the text, Tarquinia does not appear in person, but is the center of attention as the interlocutors describe and praise her intellectual, artistic, and physical assets. According to this portrayal, she embodies the ideal woman of her time in unique perfection, which is modeled after the Renaissance ideal of the universal human being. She comes from a noble family, has an excellent musical and literary education and is an excellent poet, has a quick grasp and an excellent memory and is inspired by a passionate thirst for knowledge. Her character is exemplary, her voice angelic, her beauty makes her godlike. In the other three dialogues, Tarquinia speaks for herself and expresses her views with great authority. Here the traditional ideas, which derive from the concepts of platonic , courtly and Christian love , recede into the background; Self-love is emphasized as the basis of all other manifestations of love.

water management

In 1578/1579 Patrizi dealt with a water management and at the same time political question. The reason was a serious problem on the lower reaches of the Po , on whose banks Ferrara is located. After a devastating flood in 1442, the Reno River was canalised and channeled into the Po. The amelioration measure was in the interests of the flood-damaged city of Bologna , which the Reno flows past. In the opinion of the Ferrarese, however, it was the cause of the landing that severely affected shipping traffic on the Po in their area. That is why the rulers of Ferrara in the 15th and 16th centuries either reluctantly approved or refused the discharge of the Reno water into the Po. In the 1570s, a new conflict arose between the two cities for this reason, in which Pope Gregory XIII. mediation took over.

The pope set up a commission of inquiry in which Scipione di Castro, a political adviser with no engineering expertise, set the tone. Di Castro wrote a report in 1578 in which he came to the conclusion that the landing was not caused by the Reno. This enraged the Ferrarese, for whom Patrizi, after thorough studies, took the floor. He first formulated and justified his views in a 1579 report for Duke Alfonso II d'Este, the Discorso sopra lo stato del Po di Ferrara (Treatise on the State of the Po of Ferrara) , and then in a devastating statement on the document di Castro's Risposta alla scrittura di D. Scipio di Castro sopra l'arrenamento del Po di Ferrara . His contact in the Curia was Bishop Tommaso Sanfelice, with whom he was able to communicate well. In 1580 Patrizi wrote an account of his negotiations with Sanfelice. However, his bold proposals for the construction of new canals were not taken up by the duke.

Il Barignano

An ethical theme is treated by Patrizis Dialogo dell'honore (Dialogue on Honour) published in 1553 in the Collection of Early Works , which he called Il Barignano . The namesake is Fabio Barignano, a contemporary, then still very young poet from Pesaro , who appears as one of the two participants in the fictional discussion. His interlocutor is also a historical figure, Count Giovan Giacomo Leonardi , a diplomat in the service of the Duke of Urbino . In the dedication letter, Patrizi remarks that everyone attaches great importance to honor. Even the worst person wants to be respected and respected everywhere and takes revenge for insults and slander. Nonetheless, no one has ever devoted their own work to honor and philosophically examined what it actually consists of. Only one special aspect, the duel , has been discussed in the literature so far. The Barignano is intended to remedy this deficiency . In the course of the conversation, Leonardi conveys his understanding of true honor to his young dialogue partner. According to his explanations, this does not consist in reputation, but in an unshakable, virtuous basic attitude. Therefore, true honor, which does not depend on the judgments of others, can never be forfeited, unlike sham honor, a ephemeral reputation based on external values and questionable beliefs.

poems

Two poems of praise by Patrizi date from the late 1550s. In addition, in 1559 he glorified the painter Irene di Spilimbergo after her early death in two sonnets.

The first of the two poems of praise, L'Eridano (The Po) , was written when the philosopher was trying in vain to get a job at the court of the Duke of Ferrara, Ercole II d'Este . It was intended to show the ruling house the humanistic qualifications of the author and at the same time to make an impression with the usual flattery. Patrizi dedicated the poem, in which he praised the ruling family, to a brother of the duke, Cardinal Ippolito d'Este . He had it printed in 1557 and included an explanation of the verse form, the Sostentamenti del nuovo verso heroico . Here, as in other fields, he was an innovator: he claimed to be introducing a new heroic meter into Italian poetry, suited to the heroic content of an epic. These are thirteen syllables with a break after the sixth syllable, a form modeled after the classic hexameter. In reality, this meter, which probably goes back to the Alexandrian , was not new, it was already in use in the 14th century.

The second poem of praise, the Badoaro , was written in 1558 and is also in the "new" heroic meter. Patrizi praises the Venetian humanist, politician and diplomat Federico Badoer. The long-lost text was not published until 1981.

letters

Around a hundred letters from Patricius have survived, including a letter of June 26, 1572 to Bernardino Telesio , which is particularly important as a source, in which he critically examines his philosophical principles, and an autobiographical letter to his friend Baccio Valori of January 12, 1587. They make up only a modest part of his correspondence, mostly from the Ferrara and Rome years; all letters from my youth are lost. The style is matter-of-fact and dry, without literary adornment. This source material shows the scholar as an important figure in the cultural life of his era.

Del governo de' regni

According to a hypothesis by John-Theophanes Papademetriou, which is considered plausible, Patrizi made the Italian translation of an oriental collection of fairy tales, which was printed in Ferrara in 1583, under the title Del governo de' regni . The original was a Greek version of this work, originally written in India, known as the Fables of Bidpai or Kalīla wa Dimna .

teach

With his teachings in various subject areas, Patrizi wanted to make a name for himself as a critic of traditional ways of thinking and as a finder of new paths. He liked to distance himself from everything that had gone before and chose an unusual approach, which he presented – sometimes exaggeratingly – as a fundamental innovation. He strove to broaden horizons and go beyond familiar boundaries. In doing so, he came up against a main obstacle that he tried to remove: the relatively rigid framework of Aristotelianism, which dominated school philosophy and which had formed over the centuries through the extensive commentary on Aristotle and which only permitted innovation within a predetermined narrow framework. In view of this situation, the humanist's polemics were directed not only against Aristotle, but also against the scholastic tradition, which was shaped by Aristotelian thought, and in particular against its Averroist current. He accused the Aristotelians and Scholastics of dealing with words—abstractions introduced haphazardly and without reason—instead of things, and of having lost touch with the reality of nature.

In general, Patrizi's philosophy is characterized by the priority of the deductive approach. He derived his theses from premises whose correctness he considered evident. He was striving for a scientific approach that should be based on the model of mathematical discourse. The aim was knowledge of the whole (rerum universitas) existing through order by comprehending structures. Patrizi justified his rejection of the Aristotelian argument by saying that it failed in relation to the contingent . His approach was intended to remedy this deficiency; he wanted to systematize the contingent and thus make it scientifically capable.

metaphysics, natural philosophy and mathematics

In natural philosophy, Patrizi emphasized the novelty of his teaching with particular emphasis; he stated that he was proclaiming "great" and "unheard-of". In fact, he made a fundamental break with medieval and early modern scholastic tradition.

room conception

In the scholastic physics based on Aristotelian principles, which still prevailed in the 16th century, the idea of space was tied to the concept of place. The place was conceived as a kind of vessel that can hold bodies and constitute the space. The idea of a three-dimensional space existing independently of places as a reality of its own kind was missing.

Patrizi countered this way of thinking with his new spatial concept. According to his understanding, space is neither a substance nor an accident , it cannot be classified in the Aristotelian category scheme. He is also not a "nothing" or similar to non-being, but something that actually exists , namely the first being in the world of the sensible. The being of space precedes all other physical being in terms of time and ontology , it is the prerequisite for its existence. If the world were to perish, space would still exist, not only potentially but actually. As something that is, space is qualitatively determined; its characteristics are receptivity, three-dimensionality and homogeneity. He is indifferent to what is within him. In and of itself, it can be equated with the vacuum . Physical space is corporeal on the one hand, because it has three dimensions like a body, and incorporeal, on the other hand, because it offers no resistance.

philosophy of mathematics

With the "new geometry" that Patrizi proposed, he meant a new philosophical foundation of this science. He justified their necessity with an inadequacy of the Euclidean system: although Euclid had defined elementary concepts such as point, line and surface, he had failed to develop a philosophical system that would enable the remaining geometric concepts to be determined correctly. Above all, Euclid lacks a definition of space, although space must be the primary object of geometry. Patrizi tried to remedy this deficiency by making space the basis of his own system and deriving points, lines, angles, surfaces and bodies from it.

According to Patricius, the continuum is a real fact, while the discrete is a product of thought. For him, this resulted in the priority of geometry over arithmetic within mathematics . This view corresponded to the state of knowledge at the time; the analytic geometry that extends the concept of number and makes it continuous was not yet discovered.

cosmology and the origin of the world

According to Aristotelian cosmology, the world of material things enclosed by the spherical vault of heaven forms the totality of the universe. Nothing can exist outside of this limited universe, not even time and empty space. Patrizi, on the other hand, considered the part of three-dimensional space that he imagined containing all matter to be a delimited area surrounded by empty space. The question of the shape of this area remained open. The Aristotelian assumption that the material world is spherical was viewed with skepticism by Patrizi, since no proof of the spherical shape of the sky had been provided. Apparently he preferred the hypothesis that the physical part of the universe was in the form of a regular tetrahedron . In the center of the material world, according to his model, is the earth, which rotates daily on its axis. He did not consider the counter-hypothesis, a daily rotation of the heavens around the earth, to be plausible, since the speed required for this was hardly possible. He rejected the conventional explanation of the movements of the heavenly bodies, according to which the heavenly bodies were attached to transparent material spheres ( spheres ) whose revolutions they follow. Instead, he assumed they were moving freely in space. For him, the traditional idea that the orbits were circular also became obsolete. Therefore he also gave up the concept of the harmony of the spheres, which had been widespread since antiquity and which presupposes physical spheres. However, he stuck to the idea of a harmonious structure of the cosmos in the sense of Platonic natural philosophy. He took the appearance of a new star, the supernova of 1572 , as an opportunity to declare Aristotle's assertion that the heavens were immutable and imperishable to be refuted.

In Patricius' model, the material world is surrounded by an infinitely extended, homogeneous, empty space. This is flooded with light; an empty space must be light, because light is present everywhere where there is no matter that, with its impenetrability, could create darkness. The space that encompasses the material world existed before the creation of matter, which was then placed in it. With this hypothesis, the humanistic thinker contradicted the Aristotelian doctrine, according to which a vacuum is fundamentally impossible. Even within the physical world he assumed vacua; these are tiny spaces between the particles of matter. He saw one of several proofs for the existence of such vacuums in the processes of condensation , in which, in his opinion, the empty spaces are filled.

In cosmogony , the doctrine of the origin of the world, Patrizi adopted the basic features of the Neo-Platonic model of emanation , which depicts the generation of everything created as a gradual emergence from a divine source. In doing so, he used the ideas of the Chaldean oracles and Hermetics .

Contrary to Aristotle, Patrizi assumed a temporal beginning of the world. According to his teaching, the creation of the cosmos is not an arbitrary act of God, but a necessity. It flows inevitably from God's nature, which demands creation. God must create. As Creator, he is the source, the first principle from which everything originates. This source is called “ the One ” in Neoplatonism. Patrizi used his own neologism for this: un'omnia ("One-All").

According to the "new philosophy" model, the first product of the creative process is the spatial principle, the indifferent, neutral principle of the local. Its existence is the prerequisite for everything else, for the unfolding of nature. The starting point of nature is the second principle, "light". This does not mean light as a natural phenomenon and object of sensory perception, but a super-objective natural fact, the generating principle of form, which is at the same time the principle of recognition and being recognized. Out of this light, in a continuous process , emerge entities metaphorically referred to as the "seeds" of things. These are introduced through “warmth” (Latin calor ) into “flow” or “moisture” (Latin fluor ), a flexible substrate from which the preforms of world things, their patterns, are then fashioned. All of this is not yet material; the first emanation processes take place in a purely spiritual realm. In this context, expressions such as fluor and calor only serve to describe what is not clear. Thus, fluor means the principle of continuity that establishes the connection between the different elementary areas, forces and configurations. At the same time, fluor is the passive principle of assimilation of form and the factor that gives bodies the resistance needed to maintain their mutual delimitation. The "heat" represents an active principle, it is the dynamic development of the light principle in the fluor .

Thus, the four basic principles "space", "light", "flow" and "warmth" are the basis of the cosmos. The material world emerges from them. They form a complex ideal unity inherent in all material being and antecedent to it as a condition of existence. On the material level, the fluor principle manifests itself in the form of the relative “liquidity” of material objects. This means their different degrees of density. These are the cause of the different resistances of physical bodies, their hardness or softness.

This cosmology also has an epistemological aspect. When the physical universe depends on the formative principle of light, it is lightlike. Accordingly, from Patricius' perspective, nature does not appear as impenetrable, strange and dark matter, but is clear in itself, it manifests itself. Its clarity does not have to be set and produced by the human observer. Accordingly, there can be no fundamental, insoluble problem of knowledge of nature.

concept of time

In examining time, Patricius dealt with Aristotle's definition of the term, which he subjected to fundamental criticism. With the definition that time is "number or measure of movement by means of the earlier or later", Aristotle made several mistakes at the same time. He made measure and number, which are products of human thinking, essential characteristics of the natural given time, as if a thought of man gave being to a natural thing. In reality, time exists without any measurement or counting. In addition, Aristotle only considered movement and ignored standstill or rest. It is not time that measures movement, but movement that measures time. Movement and measurement are not even essential for the human perception of time. The "earlier" and "later" of things subject to the passage of time are also not part of the essence of time. Rather, time is nothing other than the duration of bodies.

According to this understanding, time cannot be ontologically equal to space. Since it is defined as the duration of bodies, but the existence of bodies presupposes that of space, time must be subordinate to space, the primary condition, and also to bodies.

anthropology

In Pampsychia , the third part of the Nova de universis philosophia , Patrizi dealt with the determination of what is specifically human by delimiting it from the animal . There he treated the animus , the enlivening and movement-enabling entity in the cosmos and specifically in living beings. He came to the conclusion that there could be no such thing as an inherently irrational animus . In doing so, he went against the conventional wisdom that animals have irrational souls . According to his understanding, rationality is not a specific feature of humans, but is also present to a greater or lesser extent in the animal world. The empirical findings do not allow for a fundamental demarcation of the rational from the irrational, rather the differences between the species in terms of rationality are only gradual.

It also does not make sense to use the act of speech – defined as “utterance expressed in words” – as a distinguishing feature of humans, because there is no fundamental discontinuity in this regard either. Animal sounds are a means of communication that are part of their languages and function analogously to human languages. The animals are also given a certain amount of knowledge (cognitio) that enables them to act in a goal-oriented manner, and they have reason (ratiocinium) at their disposal , because they are able to meaningfully link individual memory contents with new perceptions, and that is what the mental activity. The special position of man is based only on his ability to gain deep insight into causal connections with the intellect , and on the immortality of his soul. In the writing La gola, e'l sonno, e l'ociose piume , Patrizi named impulse control as a characteristic of the specifically human in addition to access to knowledge that goes beyond what is attested to by sensory perception.

Like all Neoplatonists, Patrizi dealt intensively with the relationship between the spiritual ( intelligible ) and the sensually perceptible world. In the hierarchical order of his system, the material sphere is in every respect subordinate to the spiritual, being its image and product. The spiritual as the overriding area is the simpler and closer to the divine origin, the sensually perceptible appears in the variety of the individual sensory objects and the complexity of the physical world. Each of the two spheres is graded in itself, whereby the simpler is always the superior in terms of rank and power. The relatively simple is always at the same time the comprehensive, since it brings forth the relatively complex and diverse. Within this order of total reality, man occupies an intermediate position. He forms the lowest level of expression of the spiritual world, for his intellect is that spiritual form which combines its unity with the greatest degree of multiplicity. At the same time he is the highest level of existence in the realm of beings bound to a physical substrate, since he is the only one among them who has an intellect.

With regard to the classification of the soul in this system, Patricius agrees with the teaching of Plotinus , the founder of Neoplatonism. The issue at stake is whether the soul, through its descent into the physical world, surrenders itself completely to the material conditions, as the late antique Neoplatonists believed, or whether it can maintain its presence in the spiritual world at all times, as Plotinus assumed. According to Patricius' conviction, the human soul has no non-rational or only suffering life in itself, but only a knowing life; the impulsiveness, the irrational, is a result of physicality, which confronts it from outside.

history and theory of the state

The design of a state utopia

With his youthful work La città felice , Patrizi presented a utopian state model based on the political theory of Aristotle . At that time, the Aristotelian guidelines were still decisive for him.

The starting point is the determination of the human goal in life. For the author, as a Christian, this can only lie in the attainment of the highest good, future bliss in the hereafter. The hope of this sustains people in the distress of their earthly existence. However, there must also be an interim, earthly goal: the creation of favorable living conditions conducive to higher aspirations. For Patricius, as for other humanists, the optimum that can be achieved in earthly existence represents felicità , happiness, which he, like the ancient Peripatetics and Stoics, equated with the exercise of virtue (operazione della virtù) . The state, which is understood as a city state in the sense of the ancient polis and the Italian city republic, has the task of creating and guaranteeing stable framework conditions for this. The happiness of the city is the sum of the happiness of its citizens. This presupposes the opportunity for happy activity.

On the social level, the needs that arise from the natural love of community life must be satisfied. On an individual level, it is about carefully preserving the bond that unites soul and body, preserving the spirit of life through the fulfillment of bodily needs. First, the physical must be assured; conditions include favorable climatic conditions and adequate supplies of water and food. If these elementary requirements are met, community and public life can be optimized. This requires that citizens know and interact with one another, for example by eating together, and in particular that they connect with one another through educational endeavors and spiritual exchanges. In order for this to be possible, the citizenry must not exceed a certain size. Furthermore, the social and class inequality among the citizens must be kept within limits; the state should provide public meeting places, and legislation should counteract private hostilities. Central demands of Patricius are the time limitation of the exercise of power and the free access of every citizen to the highest offices of state. This is intended to prevent tyrannical or oligarchic abuse of power. External security is to be guaranteed by the citizens themselves, not by mercenaries.

Religious cult, rites and a priesthood to satisfy a basic human need is considered necessary by Patricius, "temple and churches" should be built and "the gods" should be worshiped. The religion of the "happy city" is not described in detail, in any case it shows no specifically Christian character.

A particularly important goal of the state is the education of children in virtue. The legislator has to ensure that they are not exposed to bad influences. Great emphasis is to be placed on the musical education of young people. The lessons in music and painting have a propaedeutic function with regard to later philosophical activities.

According to Aristotle's theory of the state, the population of the city-state is divided into estates. Only the upper classes, the ruling class, form the citizenry with political rights. The members of the lower classes - farmers, craftsmen and traders - are busy securing their livelihood and have no opportunity to achieve the happiness they aspire to in the "happy city". They are also, as the author believes, not naturally predisposed and capable of doing so. Their arduous existence is a prerequisite for the well-being of the upper classes. – With regard to the inevitability of oppression, the young Patricius followed the guidelines of Aristotle, who reserved the possibility of a successful life for an elite and saw such social conditions as a natural given. This view was widespread in the Italian educated class to which Patrizi belonged.

The evaluation of forms of government

When comparing the different forms of government, Patrizi came to the conclusion that a balanced republican mixed constitution was superior to all alternatives. One should neither entrust an individual with too much power nor paralyze the state through radical democratization. The rule of a small group spurs on ambition too much, which can lead to civil wars. The mixed constitution of the Republic of Venice , in which aspects of the different forms of government are combined, is ideal. There the element of individual rule was represented by the office of the Doge , the principle of the rule of a small elite came into play through the Senate and the idea of everyone having a say was taken into account through the establishment of the Great Council.

The justification of interest in history

As in his state utopia, Patrizi's approach to history is based on his definition of human life's goal as happiness (felicità) . According to his teachings, this has three aspects: mere being as successful self-preservation, eternal being as union with the deity and being "in a good way" (bene essere) , successful life in the social context. The consideration of history is about the study of the human striving for a "good" being in this sense. The philosopher turns to him in his examination of the historical dimension of life.

According to Patricius, the need for happiness in the sense of being good arises from sensuality and thus from the realm of the affects . Man is a sensual being filled with passions. The affects are primary facts and in themselves neither praiseworthy nor blameworthy, but they create the possibility of behavior to which praise or blame can be referred. Whether it is possible to realize the bene essere depends on whether people learn to deal with their passions properly. A person's work on himself begins when he behaves towards his own affect-relatedness, and only there can "being good" be demanded as a goal. It should be noted that – according to Patrizi – the passions do not come into their own without a reason, but are always ignited in encounters with other people and always aim to have a certain effect on others. The right relationship with them can only be gained and strengthened through practice in the community. Thus, being good through the mastery of passions proves to be identical with ethical behavior in social life, in the family and in the state.

This is where the time dimension comes into play for Patrizi. The community is not only determined by the present, but also by its history. Therefore, confronting the social challenge must include the entire past, which shows itself as history. A person living only in the present would be at the mercy of his affects like an animal. What keeps him from it is the confrontation with the past. Only history opens up the field in which the individual has to face his social task and can prove himself through his ethical behavior. A constructive reference to the present is established through the analysis and awareness of the past.

Criticism of the traditional approaches of historians

The idea that the purpose of studying history is to exemplify the validity of moral teachings and to envisage encouraging or discouraging patterns has been very common since antiquity. Also in the Renaissance, numerous authors had known of this view, including the well-known humanist Giovanni Pontano and Patrician teacher Francesco Robortello. In this way, the consideration of history was placed in the service of moral education and subordinated to its purposes. In this way, she was brought closer to poetry and rhetoric, which should also aim at educational yield. In addition, a gripping, entertaining, literary narrative was expected from the historian as well as from the poet or speaker. As a result, the distinctions between historical reporting and fiction became blurred, for example in the speeches of statesmen and generals invented by historians.

Patricius rigorously opposed this way of dealing with historical material, which had been common for thousands of years, although he was also ultimately pursuing an ethical goal and enthusiastically affirmed the role model function of great figures of the past. Like his predecessors, he emphasized the practical use of history in civic life and above all in politics. His innovation, however, was that he insisted on a consistent separation between truth-finding and moral instruction or application, and condemned any embellishment. In doing so, he attacked the famous historians Thucydides and Livy , whom he accused of inventing alleged speeches that were never actually delivered. According to his concept, the lessons to be drawn from history are knowledge that is not conveyed through rhetorical language art, but rather is to be acquired through reflection and contemplation on the basis of the facts determined by the historian.

According to Patricius' argument, the concept of historiography, which has been common since antiquity, is based on a contradictory relationship to the object of observation. The starting point of his considerations can be summarized as follows: The theorists of history dogmatically profess the ideal according to which historians are obliged to be impartial and to strictly adhere to the truth. It is evident, however, that in practice this is hardly ever the case, for the accounts of historians contradict one another on innumerable points. In addition, there are serious obstacles to fulfilling the truth claim: Because of the obvious subjectivity of perceptions and perspectives and the inadequacy of the sources, historians have only very limited access to historical reality. At best, they can determine the results of the historical events reasonably correctly, while the closer circumstances, the background and the causes remain in the dark. The actual connections are only known to the respective actors, who, however, lack the impartiality required for a truthful representation. Only impartial eyewitnesses are truly reliable, but such reporters are not usually available. The neutral historian does not have access to the information that he would actually need for his work.

For Patrizi, the train of thought can now be continued as follows: A representative of the conventional, moralizing, rhetorically embellished representation of history may concede that the pure truth must remain hidden because of the weaknesses mentioned. However, he will assert that a rough approximation is possible. One has to accept the fact that the backgrounds cannot be clarified. This concession will not seem too serious to him, because from his perspective the historical truth is irrelevant anyway. He believes that historical knowledge is not worth striving for in itself, but only as a means to an end of instruction that ultimately serves the actual goal of attaining happiness.

But this is where the decisive counter-argument comes in, with which Patricius wants to refute the view he is attacking. It reads: A free poetic invention - such as the epics of Homer and Virgil - can produce the desired moral yield just as well as a historical work that mixes the true with the invented. Thus, if one resigns to finding the truth and clinging only to the educational effect, the difference between poetry and history is abolished. Historicity loses its intrinsic value and thus historical research its meaning. Then - according to Patrizi - one can do without historical studies and instead teach happiness with arbitrary fables.

The concept of a scientific historical research

Patrizi countered the criticized understanding of history with his opposite conviction, according to which the only goal of the historian is to know the historical truth and the discovery of the facts as a contribution to the bene essere is of significant value. According to this concept, objectivity and certainty must be achieved to the extent that the human mind is at all possible. In such work, standards of morality are not taken into account, there is no question of good or bad. The assessment of what happened is important, but it is a different matter and has to be done in a different context, from a different perspective. Patricius rejected the combination of philosophy and history, as Polybius had undertaken; in his opinion, the historian should not philosophize about hidden causes of the course of history, but only deal with facts - including the recognizable motivations of the actors.

As the subject of scientific historical research in this sense, Patrizi determined the documented and remembered processes in the world of the sensually perceptible in their entirety. He called them effetti ("effects"), by which he meant the individual concrete realities over time. It is the singular and contingent facts that enter through the senses and are then processed by the mind and assigned their reasons. They are effects in contrast to the general causes and purely mental facts with which philosophy deals. However, the activity of the historian is not limited to compiling and documenting the effetti ; Rather, through meticulous research, he can also determine the reasons for their emergence, recognize the intentions and motives behind them. The possibility of explaining empirical historical facts causally justifies the claim of historical research to be a science.

According to this definition of the research object, the field of work of the historian is the universal history of what is empirically found. In doing so, Patricius turned against the usual limitation to the actions of people and the further narrowing of the field of vision to the actions of kings, statesmen and generals. Going beyond the human world, from his point of view universal history also includes the processes in nature, i.e. natural history . He also called for the full inclusion of cultural history , i.e. achievements in the intellectual field, technical achievements, the discoveries of unknown countries and peoples and the history of individual estates such as craftsmen, farmers and sailors. Constitutional history deserves special attention ; the cause of constitutional changes should always be asked. The history of ideas, which deals with conceptions, ideas, opinions and attitudes (contti dell'animo) , Patricius considered more important than the history of deeds. In addition to manners and customs, he also counted products such as clothing, buildings and ships as well as all equipment manufactured for work and everyday life as culturally and historically relevant.

Furthermore, Patricius demanded the inclusion of economic history , which had been completely neglected by historians. Without taking into account the economic and financial situation of a state, the presentation of its history is empty and airy, because the economy is the basis for the life of every community. Precise information on the state budget is important.

Another field that Patrizi has been neglecting is peace research. He remarked that he had never heard of a history of peace, although that area would be a particularly worthwhile topic.

The method