Cyrus II

Cyrus II ( Old Persian Kūruš , New Persian کوروش بزرگ Kurosch-e bozorg "Kurosch the Great", Babylonian Kuraš , Elamish Kuraš , Aramaic Kureš , Hebrew כורש Koreš , Greek Κῦρος Kŷros , Latin Cyrus ; * around 590 BC BC to 580 BC Chr .; † August 530 BC BC), often also called Cyrus the Great , son of Cambyses I , ruled Persia from around 559 BC. BC to 530 BC As the sixth king of the Achaemenid dynasty and appointed his son Cambyses II as his successor.

Through his policy of expansion, Cyrus significantly expanded the borders of the formerly small old Persian empire , which under his successors reached from India via Iran , Babylon , Asia Minor to Egypt and until 330 BC. Before it was conquered by Alexander the Great .

Archaeological campaigns and, in the meantime, improved transmissions of a number of cuneiform texts led to new insights that could refine the previous picture of historical Cyrus. Soon after his death, the Persian king was legendarily glorified by his people as the ideal king. This positive view was adopted by the Greeks , reinforced by his portrayal in the Bible as a religiously tolerant ruler and still dominates his judgment today. His person is still regarded today as the model image of a king and ruler.

Historical sources

The reports that have been received from ancient historians differ widely, especially on the origin and early years of Cyrus, because of the contradicting legends that arose very early on. The greatest credibility is ascribed to the contemporary cuneiform texts, on the basis of which scholars can partially check the statements of the Greek historians.

Cuneiform texts

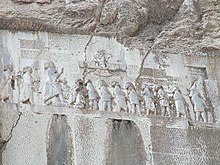

The oldest sources about Cyrus are written in cuneiform . The Cyrus Cylinder one and in great brick inscription found in 1850, four-line allowed Cyrus to submit itself.

The name "Achaemenide" in the inscriptions from Pasargadae was added by Darius I afterwards and probably served to establish a relationship with Cyrus, since Darius I was not a direct descendant of the founder of the empire and therefore introduced a common ancestor to Achaimenes . The Bisutun texts deal with the subjugated provinces. Babylonian private documents, which were found in large numbers, serve to determine the chronology more precisely.

Also important is the so-called Nabonidus Chronicle , which reports in its legible part about the last years of the independent Babylonia and its conquest by Cyrus.

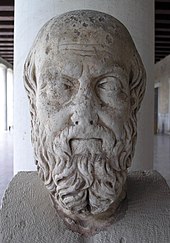

Ancient historians

Of the ancient Greek authors, around a hundred years after Cyrus , Herodotus is the historian who delivers the earliest account, which has also been fully preserved. That is why it is the main Greek source on the life of Cyrus. He already knew various legends about the Persian king, B. both about his youth and the circumstances of his death. That is why he chose the version that appeared to him “most likely” from among the versions available to him.

The decorative elements, which were already partially adopted by Herodotus, developed even more clearly in later historians. This applies in particular to the politically motivated work Education of Cyrus by Xenophon . But the extensive accounts of the historian Ktesias von Knidos on the history of the Persians in his Persika , which reports on Cyrus in volumes 7-11, but only exists today in fragments in excerpts from the Byzantine patriarch Photios , are considered dubious by research and considered difficult to verify.

A detailed excerpt from Nikolaos of Damascus deals with the youth and early rise of the Persian king. In a text-critical analysis, the ancient historian Richard Laqueur contradicted the widespread view, represented by Felix Jacoby , among others , that this report, handed down by Nikolaos of Damascus, was a pure excerpt from Ktesias. Rather, Laqueur assumes that Nikolaos worked two sources into one another: the main source was a Lydian author, perhaps Xanthos , who had a similarly positive view of Cyrus as Herodotus and celebrated him as a noble hero. The view of the secondary source used by Nikolaos, which Laqueur identified with Ktesias, was completely different: the Greek historian, who lived at the Persian court for so long, characterized the founder of the Persian Empire as a person of low descent, who acted completely dependently and only guided and guided through the help of others was finally put on the throne. After this analysis, Ktesias gave an extremely negative portrait of Cyrus and all points of contact between the portrayal of Herodotus and Nikolaos were based on his Lydian source. It is possible that the story of Herodotus is of Lydian origin, only that he did not receive this source as pure as Xanthos.

The Babylonian historian Berossus is to be counted among the sources that contain mostly reliable representations, e.g. B. also in the short extant excerpt that reports on the conquest of Babylon. Fragments of the Alexander historians also report on the tomb of Cyrus .

After all, Cyrus “as the liberator” of the Jewish people from exile in Babylon plays a prominent role in the Bible and is portrayed accordingly.

Surname

The ancient historians Ktesias von Knidos and Plutarch translated the name Cyrus with " sun " (Kur-u). In addition, an attempt was made to extend it to “like the sun”, as a reference to the Indo-European root word “khor” and the suffix “-vash” was made. However, this translation has meanwhile been rejected by modern research.

The interpretation is still controversial. Among other things, a derivation from the Vedic language using "Ku, ru-" for "young man or child" is being considered. Linguists such as Karl Hoffmann and Rüdiger Schmitt translate the name as "Gracious ruler over the enemy / ruler with the gracious judgment of the enemy".

origin

Herodotus' information about the lineage of Cyrus is confirmed by the inscription of the Cyrus cylinder on the father's side. Accordingly, the Persian king was a son of Cambyses I and grandson of Cyrus I. According to Herodotus , the mother of Cyrus was Mandane , the daughter of Astyages , under whose suzerainty Cyrus' father Cambyses I stood as king of Anjan . At that time, Astyages was given the title of ruler as the main military leader. So that Astyages was the maternal grandfather of Cyrus cannot be proven by cuneiform finds. Ktesias denied Herodotus' statements and named another genealogy of the parents of the Persian king, who was therefore not the son of a king, but the son of a robber and a goatherd. However, this information turns out to be incorrect when compared with the inscriptions. Obviously Ktesias tried with a deliberate falsification of history to belittle the founder of the Persian Empire and therefore let him descend from low parents. His entire further report on the youth of Cyrus presents this in an extremely unfavorable light. On the other hand, Herodotus' report is that Astyages, warned by a dream, recognized a danger in little Cyrus and therefore wanted to have him killed, but the infant instead without it Knowledge of the ruler of a shepherd living in the distant mountains, whose wife gave birth to a dead child who is said to have been secretly exchanged for Cyrus, raised and thus saved, an unhistorical legend based on older Mesopotamian models. Since there is no further cuneiform information on Cyrus's early years, it must be stated that nothing is known about it.

The cylinder inscription, the Nabonaid Chronicle and another cuneiform text can be seen that Cyrus around 559 BC. As a regional member of the Median Confederation, he followed his father Cambyses I as King of Anjan.

Cyrus saw himself as a descendant of Teispes and accordingly referred to himself as "Teispide". The later change of the genealogy made by Darius I and the assignment of Achaimenes as the founder of the dynasty served to substantiate his claims to the throne. Today, however, it is largely doubted that the Teispiden, as the ancestors of Cyrus, were actually related to the Achaemenid ancestors of Darius I. Accordingly, Cyrus was not an Achaemenid.

The cuneiform tradition did not begin until the war between the Persian king and Astyages.

Fall of the Astyage

The disputes between Cyrus and Astyages are described in two cuneiform texts. Babylon knew neither the name media nor the royal name Astyages and used, as also z. B. in the Sippar cylinder, the Babylonian terms "King Ištumegu from Umman-Manda" ("somewhere-da-land"). The god Marduk told Nabonidus in a dream that Ištumegu was defeated by the militarily much weaker Cyrus, captured and taken to his kingdom, Anjan. The text about the war against Astyages in the Nabonidus Chronicle is difficult to read due to damage, but the following additional messages could be translated: The Median army rebelled against Astyages and handed him over to Cyrus, who then moved into the Medes capital Agamtanu (Ekbatana) and had the riches of the city brought to Anshan. The report of Herodotus fits to some extent that a courtier named Harpagos , who once failed to carry out Astyages' order to kill little Cyrus and was punished for it with the murder of his own son, went over to Cyrus, so that the Medieval king his army personally led into the next battle, but was defeated and taken prisoner. The portrayal of Herodotus should correctly confirm that Cyrus had a powerful helper on Astyages' military staff. Whether this was called Harpagos remains to be seen.

According to the Nabonidus Chronicle, the fall of Astyages took place in 550 BC. In Nabonidus sixth year of reign. In the inscriptions on the Sippar cylinder, in Nabonidus' third year of reign, the "awakening of Cyrus" is described, who marched with an army against Astyages. The seemingly temporal contradiction shows that the Medes campaign of Cyrus was subsequently noted and moved to the third year of the reign of the Babylonian king in order to avoid a temporal overlap with the Tayma stay, which is not specifically mentioned in the other report of the Sippar cylinder.

The background is shown by the tendency writing of the Cyrus oracle , which was created later as a subsequent prophecy ( vaticinium ex eventu ). Nabonid expressed concern about the siege of Harran by the Medes, which would prompt the immediate rebuilding of the temple of Ehulhul in 555 BC. Made impossible. The moon god Sin prophesied in response to the Babylonian king, "that the Medes, their land and their kings as well as all allies will soon be destroyed by the hand of another king". Nabonidus moved the year of promise to 553 BC. In his third year of reign in order to simulate a timely start of construction. The Marduk priesthood, hostile to the Babylonian king, had named in their diatribes the “wrath of Sins” as the reason that led to the “divine expulsion of Nabonids to Tayma”, with which Sin wanted to punish the failure of the Babylonian king with regard to holy duties.

From this information, the probable course emerges that the fall of the Astyage took place in partial steps and Cyrus led individual campaigns against the other partners of the Astyage over several years, which in the year 553 BC. Began in the Harran region. The final takeover of the Meder Confederation by the Persians is therefore mostly dated to 550 BC. BC.

The fictional account of Nikolaos of Damascus, who relies on Ktesias, mentions the cuneiform documented details that Cyrus invaded the hostile capital and seized its treasures; a point left out by Herodotus. According to another fragment of the Ktesias, Cyrus installed the conquered Astyages as ruler in Hyrcania on the Caspian Sea .

Cyrus later resided in at least two capitals. The Ekbatana (today roughly equivalent to Hamadan ), conquered by the Medes, was used in the summer months. The establishment of Pasargadae in Persis followed as a new metropolis ; supposedly in place of his victory over Astyages. After completion it held court there in winter.

Military expansions

Median principalities

After Ekbatana was taken without a fight in 550 BC. Cyrus began in 549 BC. BC with the subjugation of the principalities and regions that previously belonged to the Median confederation. These probably included Parthia and areas south of Lake Urmi in the Zāgros Mountains .

Based on reports from Greek historians, scholars earlier believed that Cyrus began his military expansion as a vassal of Astyages. Archaeological excavations and new cuneiform evaluations of the neighboring countries allow the conclusion that the Achaemenids were not subjects of the Medes: "The Achaemenids were never dependent on the Medes, but took over a well-functioning administrative and military apparatus from the Medes".

Urartu

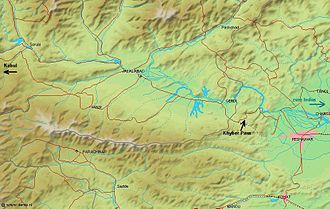

Campaign stations on the way to Urartu. ( Country data indicate the center of Paršua and the media ). Physical map of Iraq and environs |

The spread of the year 547 BC. BC for the beginning of the Lydian War took place on the assumption that Smith's reading from 1924 with "Lu-u- [d-di]" was correct. In the further course, however, doubts arose about this translation. The historians Grayson and Hinz did not exclude "Su" and "Zu" as the first syllables and moved the campaign to Palmyra . In 1977 Cargill came to the conclusion that a reading as "Lydia" was unlikely and that Cyrus continued until the years 543/542 BC. Was busy with campaigns in the Median core area; In 1985, Zadok also doubted Smith's earlier reading in this context, as the usual spelling of Lydia was in "Lu-u-du".

New investigations between 1996 and 2004 revealed the reconstruction of the damaged fragment: " Itu guana KUR U- [raš-tu il-li] k", where the name "Uraštu" is the shortened form of Urartu in cuneiform .

“In the month of Nisanu , Cyrus, king of Parsu, gathered his troops and crossed the Tigris below Erbil . In the month of Ajaru he marched to Urartu, killed the local king and stationed his troops in a fortress. "

Detailed evaluations of the campaigns show in addition that the Euphrates - Route for activities in the regions of Tabal , near Lydia, always Carchemish led. The military campaign in 547 BC However, Cyrus led Arrapcha , Erbil, Nisibis , Mardin and Tur Abdin via the Urartu route . Since Nabonaid mentioned the Erbil station, it can be safely assumed that Cyrus took the usual route and at the same time claimed the territory of Babylon for the passage.

A scheduling of the Lydian campaign for 541 BC Is supported by the Nabonaid Chronicle. Cyrus first sent messengers to the rulers of the Greek cities of Asia Minor from the Lydian king Croesus and asked them to submit to his rule. Most of the instructions were not followed. The Lydian king, who was informed of the activities of the Persian king, feared, with good reason, that Cyrus would advance into his country and concluded an alliance with Egypt and Babylon, which, however, did not occur until Nabonaid returned in 542 BC. Could have been done. After the subsequent questioning of the oracle of Delphi (which is said to have spoken: "If Croesus attacks the Persians, he will destroy a mighty empire." Or "If you cross the Halys, you will destroy a great empire"), Croesus ordered them Mobilization of his army.

War against Lydia

The Lydian king then crossed the border into Cappadocia , conquered the fortress of Pteria and awaited the Persian army east of Halys . This soon approached under the leadership of Cyrus. After a long fight in the battle of Pteria brought no decision, Croesus withdrew to Sardis . He released his troops into the winter quarters as he apparently did not expect any further fighting. In anticipation of the continuation of the military conflict next spring, Croesus hoped for military support from his allies Egypt and Babylon . A call for help to Sparta contained the request for further troop units.

Aware of this situation, Cyrus ordered his army units to march to Lydia in forced marches. The Persian king acted spontaneously, attacked the capital Sardis and defeated the Lydian cavalry outside the city gates. This was followed by a two-week siege, which was probably due to renewed attacks and the storming of the stronghold of Sardis in 541 BC. Ended with a victory for Cyrus.

There is disagreement in the sources about the further fate of Croesus. According to the Greek chronicler Eusebius of Caesarea , he was killed by Cyrus II. According to Bakchylides , Croesus wanted to be burned on a stake with his family before Cyrus' arrival, but Zeus put out the fire and raptured them. On the other hand, according to Herodotus, Cyrus II wanted the Lydian king to be burned at the stake, but then regretted it, had the flames extinguished and used him as an advisor in the future. Occasionally it was concluded that when the victors arrived, Croesus had already placed himself at the stake to immolate himself, but was stopped from doing this by Cyrus.

Submission of Asia Minor

After the defeat of Croesus, the Greek cities of Asia Minor were ready to submit to the Persians on the condition that Cyrus would confirm the privileges they had enjoyed under the rule of the Lydian king. However, Cyrus had not forgotten the rejection of the princes at the beginning of the dispute with Croesus to support his campaign militarily and now rejected their messengers with contempt. This is probably why the cities of Asia Minor behaved in the following rebellion in 540 BC. Chr. Loyal opposite the Cyrus as treasurer used Lydians PAKTYES . He had previously received the order from the Persian king to collect and deliver the Lydian gold, but instead passed the gold on to the Greek coastal cities to finance the uprisings.

Harpagos had been promoted to general of Cyrus for his services. Now he and Mazares could quickly suppress the rebellion and punish Paktyes. There were campaigns of revenge against the Greek allies of the insurgent. Mazares plundered Priene and enslaved its noblest citizens. Then he proceeded similarly with magnesia on the meander . Mazares passed away soon after. His successor was Harpagos, who subjugated Smyrna , Phokaia and subsequently all the mainland Ionians , who from then on had to support him on his further campaigns.

The Karer surrendered almost without a fight with the exception of Pedasa . The inhabitants of the Lycian city of Xanthos are said to have fallen to the last man in the fight against the troops of Harpagos, after they had previously burned their families and treasures.

Only Miletus was spared and was allowed to maintain a certain independence because it had helped Cyrus against Croesus and not supported the rebellion against the Persians.

War against Babylon

An exact reconstruction of the 542 BC After the return of Nabonaid from his exile in Tayma in the 14th year of the reign , due to the lack of cuneiform evidence, this cannot be done. We have certain knowledge of the activities leading up to Cyrus, who fueled tensions between Nabonaid and the Marduk priesthood by making aid pledges to the Nabonaid opponents and offering himself as an alternative government . In the meantime, Nabonaid initiated defensive measures for Babylon, which began in March 539 BC. Were intensified by bringing the Ishtar statue home from Uruk . First attacks by Cyrus on territories of Babylon in the spring of 539 BC. BC, which the Persian king carried out in the Gutium region , caused Nabonaid to transfer more statues of gods to Babylon as reinforcements. The Babylonian king acted according to the old Mesopotamian belief, since the gods grant their blessings to those who are in possession of their pictures. Cyrus later turned this act of Nabonaid into its opposite by claiming that the Babylonian king had the images brought to Babylon against the will of the gods and thus incurred their wrath.

The fall of Babylon

Campaign stations of Cyrus ( country data indicate the center of the respective state). Large Map: Iraq Small Map: Saudi Arabia |

For his part, Cyrus moved in late summer with an alliance of Persians, Medes and other tribes on the way back over the Rewanduz Pass, about 66 kilometers northeast of Erbil, through the province of Sagartia , which he occupied without a fight after the Persian king with the Sagartian prince Ugbaru entered into a military alliance and assured him of the satrap position in Babylon. The attack campaign on Babylon was started from there in September via the Diyala River to Opis on the Tigris , about 400 kilometers away . At this fortress at the eastern end of the so-called " Median Wall ", the battle was decided very quickly, and the Babylonian Empire was subject to the Persian-Median alliance. After the subsequent massacre of the Babylonian prisoners, the last strategic fortress, Sippar , was captured without resistance. Cyrus tried to catch Nabonaid, who had meanwhile fled. The Nabonaid Chronicle reports in detail about the events:

“In the month of Tashritu , Cyrus fought the battle of Opis on the banks of the Tigris. Because of the strength of the army of Cyrus the Akkadian soldiers withdrew ... On the 15th Tashritu Sippar was captured ... Cyrus had the spoils of war carried away and the prisoners killed ... On the 16th Tashritu Ugbaru, governor of Gutium and the army of Cyrus entered Babylon . "

After Ugbaru entered the city without a fight on October 6, 539 BC. According to the Nabonaid Chronicle, Nabonaid was captured in Babylon. Cyrus, who had sent Ugbaru ahead to Babylon, entered Babylon 17 days later on October 23rd. According to the report of the Nabonaid Chronicle, branches of reed were spread out for the Persian king when he proclaimed peace for the whole country on his arrival.

Even before the Babylonian New Year, which took place in the month of Nisanu in 538 BC. Should be celebrated, Cyrus left Babylon with a view to the remaining scarce period and had his decree announced in Ekbatana .

Ugbaru was appointed as satrap of the land of Babylon, in turn, appointed provincial governors subordinate to him and confirmed Nabû-ahhe-bullit in his previous office as commander of Babylon city. According to the proclamation in the Cyrus decree, the "gods of Akkad ", who were brought to Babylon by Nabonaid, returned home in the months from Kislimu to Adaru .

In contrast to his predecessor Nabonaid, the Persian king respected Marduk as the supreme god of Babylon, whose cultic veneration he had to renew and confirm. Without the divine legitimation by Marduk, an appointment as King of Babylon would have been unthinkable, which took place on March 21, 538 BC. Through the Babylonian prescribed protocol with the "taking of the hands of Marduk" took place. For a closer connection to the newly formed Persian Empire, the Persian king not only promoted the Marduk priests, but also left other important officials of Nabonaids in their functions. This strategically wise behavior and the no longer existing Babylonian army meant that there were initially no uprisings in Babylon, so that the entire territories of the conquered empire, e.g. B. Palestine , after the receipt of the royal insignia now fell to the Persian king.

The time after Nabonaid

The chronicle gives no information about the whereabouts of Nabonaid, but his execution is to be regarded as probable, since the reports on the subsequent actions of Cyrus hardly allow any other interpretation. After the coronation, the Persian king ordered the demolition or the pillage of all Nabonaid structures. Writings that had Nabonaid as their content obeyed the same purpose as statues and pictures of him. The last statements about Nabonaid end in the " verse poem " with the words: "Everything that Nabonaid had created in his life was distributed as ash by the wind in all directions."

According to Xenophon, Ugbaru (Gobryas) and another defector, both of whom had been badly treated by the Babylonian king, entered the palace the night after the Persians entered Babylon and killed the king they hated. According to Berossos, however, Nabonaid surrendered in Borsippa , was pardoned by Cyrus and was allowed to spend his old age in Carmania . Abydenus reported that Nabonaid also became regent of Carmania .

Ugbaru died on October 18, 538 BC. About a year after Cyrus entered Babylon, who subsequently appointed his son Cambyses II as his successor and gave him the title of "King of Babylon". After handing over the title to his son, the Persian king retained the superior rank of "King of the Countries". The wife of Cyrus, Kassandane , suffered the same fate as Ugbaru a few months later and died on March 28, 537 BC. BC immediately before the Babylonian New Year, the official main celebrations of which began on April 5th with the obligation of the Babylonian king after the seven-day state mourning had been ordered . Cambyses II, who was apparently unfamiliar with the Babylonian protocol, appeared in army clothing to greet the Babylonian deities, causing a scandal that snubbed and insulted the priesthood. This is probably why Cambyses II soon had to hand over his office to Gobrya's successor , who was officially mentioned in the Babylonian Chronicle from 536 BC. Was led as satrap of "Babylon and the Transeuphratene".

Few cuneiform sources are available about the economic and administrative policy pursued by Cyrus. Nabonid had already started to change the infrastructure and spread it over several pillars. The Babylonian king used his stay in Tayma to build up an extensive trade network, which Cyrus took over and further intensified after the conquest of Babylonia. However, the Persian king avoided making fundamental theological changes.

Administratively, the Persian king appointed "commissioners" who took care of domestic political affairs in the newly introduced administrative districts. Phenicia was cooperative with Cyrus , but remained independent. Thanks to the Phoenician fleet, Persia also advanced to become a major sea power. Under Darius I, a fundamental division of the regions into provinces followed later, as Cyrus was mainly occupied with the campaigns in the eastern provinces.

Eastern Persian Provinces

Since Babylon initially remained calm in the next few years and the countries of Asia Minor were militarily ruled by Cyrus, he now turned his attention to the provinces east of Elam and undertook after 539 BC. Several campaigns in the following years. He first subjugated in 538 BC BC Bactria ; followed by Gandhara , Sogdia and Khorezmia . Over the Chaiber Pass , Cyrus reached further and further east, including to Sattagydia and the Indus . Finally he reached the area at Yachša-Arta (Jaxartes) , which was far in the north-east of the old Iranian language area .

The there nomadic resident Saken and Massagetae could not completely subdue the Persian king and had to protect several fortresses, such. B. Kurushata , establish. The building of these protective castles apparently could not bring about lasting pacification, as small revolts of the local tribes were reported again and again.

religion

Cyrus in the Bible

Little is known about the personal religious attitude of Cyrus. From the statements in the Bible, the impression is gained that the Persian king did not impose any restrictions on other faiths, such as Judaism .

Cyrus is mentioned positively in 2 Chr 36,22 EU , Ezra 1,1 ff. EU as well as Isaiah (44,28 EU and 45 EU ) and compared with a “ Messiah ” who “through the awakening of his spirit” the return of Jews Parts of the population from the Babylonian exile made possible. In addition, the Persian king is said to have received the order " to build YHWH a house in Jerusalem ".

The historical evidence suggests that Cyrus probably continued the religious practice of the Assyrians and Babylonians, if Nabonaid's short-term change to monolatry is ignored. There are no indications of restrictions on traditional and individual religious practice in the private sphere. The commission to build a temple in Jerusalem is not mentioned in the Cyrus Edict and appears for the first time in Xenophon's novel The Education of Cyrus , which was written about 160–180 years after the decree.

The biblical tradition therefore interprets the statements of the generally accepted possibility of returning to the home countries and the tolerance of private faith theologically from a retrospective perspective at a time when the building of the temple and other measures had long since ended.

Religious politics

Cyrus, who apparently respected the individual beliefs in other countries, consistently curtailed the powers of larger temples in the conquered states in order to weaken their sphere of power and effectiveness. First, government grants to maintain the temples were canceled and a tax payment was imposed. In addition, services had to be provided to the Achaemenids.

The office of royal commissioner was created for the control and administration of the temples. New constructions and extensions of the temple complex had to be financed from own reserves. The additional financial services that were previously provided by the respective states and provinces were no longer applicable.

The financial aid granted by Cyrus for the construction of the Jerusalem temple and the tax exemption of the priests, according to the biblical report (cf. Book of Ezra, chapters 6.9 ff. And 7.20 ff.) Contradict these regulations.

Cyrus and Zoroastrianism

Attempts to connect Cyrus with Zoroastrianism are mostly based on the reports of ancient historians regarding the furnishings of the Cyrus tomb and on conclusions about the current state of the last resting place of the Persian king. The main reason against the statement that Cyrus already took over the religion of Ahuramazda is the missing name of the Persian king in Zoroastrian documents.

Only under Dareios I is from 521 BC In the Behistun inscription, the confession of the Zoroastrian faith is documented. The depiction in Naqsch-e Rostam shows him with a golden crown around which a cloth diadem is wrapped. Opposite, Ahuramazda can be seen in the winged sun disk as the manifestation of the miter .

The only completely proven connection between Cyrus and the Avestan faith is the name of his daughter Atossa . However, this fact raises the question of whether the Persian king or his wife Kassandane were responsible for the naming. There are no references to Cyrus himself as a sympathizer of Zoroastrianism. At least at the present time there is no evidence of an active role by Cyrus at Ahuramazda, so the answer to these questions must remain open.

death

In August of the year 530 BC Cyrus was killed in another campaign against a nomad tribe on the eastern border of his empire. There are various statements about the exact circumstances of death from Herodotus, Ktesias of Knidos and Berossus, while Xenophon deviates entirely. According to Herodotus, the Persian king probably died in a campaign against the massagers, although he initially won against the king's son Spargapises, who therefore took his own life. In the decisive battle, however, Cyrus was defeated by Queen Tomyris and was fatally wounded. In revenge, the winner had the fallen Cyrus cut off the head and put him in a blood-filled tube.

According to Ktesias von Knidos, the Persian king last waged war against the Derbiker, who were reinforced by Indian contingents with elephants. During the fight, Cyrus was thrown from his horse and suffered a spear stab in the thigh. Although neither side could decide the bloody battle, the Persians received additional contingents and won the next fight with a loss of 11,000 men, while the Derbiker had to mourn 30,000 dead, including their king Amoraios. However, three days after his injury, Cyrus also died of his wounds. Only Ktesias mentions the transfer of his body to Persia in order to have it buried there. Alexander the Great was born in 330 BC. The alleged tomb of Cyrus in Pasargadai shown. A small building nearby, called "Mother Solomon's Tomb", is often identified with the Cyrus tomb described below.

The Babylonian historian Berossus tells that Cyrus was killed in a battle on the Daas plain. Historically, Xenophon's statement in his Cyrus novel Education of Cyrus that the Persian king died peacefully like a Greek philosopher has been refuted .

Tomb

At the request of Alexander the Great, who admired Cyrus, Aristobulus of Kassandreia twice visited the final resting place of the great Persian king in Pasargadai. Both Arrian and Strabo included his description in their works; both authors differ only minimally from one another.

Thereafter, the rectangular grave building was in a large garden, was built at the base of solid stone blocks and had a burial chamber with a narrow entrance above. Inside it was a table with glasses, a gold sarcophagus in which the body of Cyrus had once been buried, a bier, and magnificent clothes and jewelry. Near the ascent to the grave was a hut for its guardians, the Mager . A Persian inscription adorned the grave: “O man, I am Cyrus, who founded the rule of the Persians, King of Asia! Do not envy me this monument! ”After Aristobulus' first visit, the grave was robbed. Now he had it restored and walled up.

The biographer Plutarch gives a similar text of the inscription , who incidentally only reports briefly about the grave and only generally states Persia as its location.

The so-called "Tomb of Mother Solomon" (Mašhad-e Madar-e Solayman) , a small stone monument known to Europeans since the 16th century about 1 km southwest of Pasargadai, was first mentioned in 1809 by Morier because of its similarity to the description of Aristobulus identified in the tomb of Cyrus. This view is still largely undisputed today. At the beginning of the 13th century the building was converted into a mosque.

The Cyrus Tomb is a rectangular, small building with a sloping roof and a very small door (139 cm high and 78 cm wide), to which a staircase used to lead. It stands on six almost square stone slabs tapering towards the top, the lowest of which is about 13 m long and 12 m wide. The building itself measures approximately 6 m in length and 5 m in width and houses an approximately 3 × 2 m empty room. The total height of the grave is estimated at 11 m. The inscription mentioned by Aristobulus is missing. A 50 m long and 40 m wide, rectangular wall formerly enclosed the grave. Art traditions of the peoples subjugated by the Persians flowed into this building. The stepped base resembles a Babylonian ziggurat , while the structure of the cella has Greek-Ionic stylistic elements.

reception

Legends of Cyrus' Youth

A predominantly positive picture of the Persian founder of the empire was drawn very early on and his life was transfigured by numerous legends. There were various imaginative versions, especially over the early years of Cyrus:

According to Herodotus, Astyages, king of the Medes, had two dreams that indicated his overthrow by the son of his daughter Mandane. He therefore ordered his confidante Harpagos to kill the newborn Cyrus. However, Harpagos did not carry out the order, but instructed the shepherd Mithradates to abandon the baby in the mountains. But Mithradates did not follow Harpago's instructions and raised little Cyrus with his wife.

When Cyrus was ten years old, he was playfully appointed king by the village children and had one of the boys flogged for insubordination. His father, a distinguished Mede, complained to Astyages, who therefore summoned the people concerned and learned at the following meeting that his grandson was still alive. On the reassurance of his fortune-tellers, he did nothing against the young Cyrus, but had Harpagos' son killed. Later the grieving father incited the grown-up Cyrus against Astyages, which should lead to his overthrow.

The detailed report by Nikolaos of Damascus, which probably goes back essentially to Ktesias and was supposed to completely discredit the Persian king, is quite different. According to this, Cyrus was the son of the poor robber Atradates from the tribe of the marten and the goatherd Argoste. After arriving at the court of Astyages at a young age, he first had to do the basest work as a palace sweeper. He is even said to have been flogged and only slowly rose through his services in the hierarchy . In the end he inherited the great fortune of an upper cupbearer who also recommended him to the king. So he gained the favor of Astyage and significant influence.

His mother, whom he had brought in, told him about a dream she had had when she was pregnant. This dream is unmistakably similar to the first of Astyages in Herodotus. A Babylonian interpreted it as a sign that Cyrus would become king. The cadusii then planned without the consent of their king Onaphernes an uprising against the Medes. Astyages sent Cyrus as an envoy to Onaphernes, who on the way met a man named Hoibares, whom he made his companion on the advice of the Babylonian. The three men returned to the Median royal court after the delegation had been completed and planned the overthrow. Hoibares, however, eliminated the Babylonian interpreter of dreams in order to have one less confidante.

At the suggestion of his son, Atradates was now arming against Astyages. Soon after, Cyrus left the Mederhof to visit his father. A song by one of his singers drew Astyages' attention to the overthrow plans, as it told of a mighty lion who released a boar into freedom. The boar's powers grew until he was finally able to defeat the stronger lion. Astyages immediately related this fable to his relationship with Cyrus and tried to have him brought back to his court, either alive or dead. Since this project failed, there was a military conflict between Astyages and Cyrus over the throne of the Mederreich. From here on the fragment of Nikolaos breaks off and one only learns brief details from the end of the war through Photios' excerpt from Ktesias.

The documentaries of the Greek historians also contain the traditional ideological claims of the Persians on the media and also on Lydia. The legends about mandans were copied from Mesopotamian models, e.g. B. Sargon von Akkad , and with Iranian characteristics prove the later appreciation of Cyrus as the charismatic founder of the ancient Persian world empire.

The image of Cyrus from antiquity to the Middle Ages

Aeschylus called Cyrus a peace-loving king who acted very prudently. Xenophon wrote around 360 BC Although the eight-volume monograph Education of Cyrus was about the Persian king, it became clear after a modern review that this work wanted to portray an ideal king in the form of a novel and that the historical facts were imaginatively interpreted and adapted. The philosopher Aristotle characterizes Cyrus as a benefactor who brought freedom to the people.

The negative aspects of Cyrus' person and politics were pushed into the background. According to Herodotus, the ancient Persians called him their "father" and evidently adored him very much. It is probably not by chance that Xenophon chose him in his novel as a role model for an ideal king. The Greek historian reports accordingly that songs and legends about Cyrus were still circulating among the Persians in his day.

The positive representation in the majority of ancient literature continued into the Middle Ages. The Judeo - Christian tradition interpreted the Median king's dream of the vine as a portent for the birth of a king who was destined to liberate the Jewish people from their exile in Babylon. According to the Speculum humanae salvationis from the 14th century, Cyrus' birth predicted that of Mary , who would bring the "Messiah of humanity" into the world.

Modern scientific assessment

The United Nations published in 1971 in all official UN languages the inscription of Cyrus Edict, this was called at the initiative of the Iranian government as "the first charter of human rights." This happened without a neutral examination of the historical background. To date, the UN has not commented on critical questions relating to the propaganda purpose of the text. The construction of a connection with the modern concept of human rights, which did not exist at the time of Cyrus, is not accepted by historians, since such an approach is unhistorical and does not do justice to the reality of the time. The ancient historian Josef Wiesehöfer contradicts unscientific representations that describe Cyrus as a king "who brought ideas about human rights into circulation". The inscription is one-sided as a self-portrayal of the ruler. Fake translations circulating on the Internet also serve propaganda purposes , in which Cyrus even advocates minimum wages and the right to asylum.

The publication of the inscription by the UN in 1971 was in connection with the jubilee celebrations "for the 2500th anniversary of the Empire of Iran" , which the then government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi celebrated at great expense. The Shah attached great importance to building on the old Persian tradition. The German Iranian Studies dedicated a commemorative publication with prefaces a. a. of the Federal President and the Federal Chancellor. In fact, the figure of 2500 years did not refer to a (fictional) year of the founding of the empire - as was claimed by the Iranian side and also by German well-wishers - but to the fact that Cyrus died two and a half millennia ago. According to the occasion, the appreciation of Cyrus in the Festschrift by the Göttingen Iranist Prof. Walther Hinz was extremely positive. The printing of the Festschrift was financed by funds from the German economy, the Federal Foreign Office and the Institute for Foreign Relations.

From the point of view of modern research, Cyrus appears to be an exceptionally capable ruler who achieved his foreign policy goals through the skillful use of pressure and temptations. His successful strategy enabled him to create the first great Persian empire from a modest inherited territory in just three decades. It is therefore not surprising that numerous legends and glorifications of Cyrus soon began to circulate in his empire as well as in other countries . Materials from Mesopotamian myths were combined with legends of Persian origin.

Fiction

The story of Pantheia - who, according to Xenophon, was the wife of an enemy of Cyrus, fell into the hands of the Persian king and, despite its beauty, was not touched by him - found its way into the works of the Italian poet Matteo Bandello and the English author William in the 16th century Painter ; The German playwright Hans Sachs also created some poems based on this motif. The French Pierre Mainfray ( Cyrus triomphant , 1628) and Antoine Danchet ( Cyrus , 1706) treated the youth of Cyrus dramatically. The most extensive novel (13,000 pages) about the Persian king was written by the French writer Madeleine de Scudéry ( Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus , 1649–1653). In order to get a job with the Prussian ruler Frederick the Great , the German poet Christoph Martin Wieland named the monarch a New Cyrus in his Golden Mirror (1772) .

performing Arts

Since the Speculum humanae salvationis, which emphasized the religious importance of the king , was widespread in church circles, many pictorial representations of the Cyrus theme in churches and monasteries were encouraged, for example stained glass from the Ebsdorf monastery near Uelzen . Four tapestries in Notre-Dame in Beaune go back to the work of the Count of Lucena (1470), written for the Burgundian Duke Charles the Bold , which was based on Xenophon's education for Cyrus . The American painter Benjamin West relies on a picture (1773, London) for the British King George III. , on which Cyrus generously forgives an Armenian king who he defeated, also on Xenophon. The Persian king appears before the throne of Astyages in the painting by J. Victor (1640, Oldenburg). A portrait of Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (around 1655, Dublin) depicts the motif of little Cyrus suckling a dog . A fresco by the Italian painter Pietro da Cortona (1641/42, Florence, Palazzo Pitti) shows how nobly Cyrus behaved towards the beautiful Pantheia .

music

Since the 17th century, musical works, mainly operas, have also dealt with the subject of Cyrus. So wrote Antonio Bertali Divertimento Il Ciro crescente (1661). For the libretto by GC Sorentino, Francesco Cavalli wrote the opera Il Ciro (1654) , among others . For example, operas by Tomaso Albinoni ( Ciro , 1709) and Antonio Lotti ( Ciro in Babilonia , 1716) are based on the text by Pietro Pariati . Settings of the libretto Ciro riconosciuto of Metastasio created about Baldassare Galuppi (1737), Niccolò Jommelli (1744) and Johann Adolph Hasse (1751). Gioachino Rossini composed the opera Ciro in Babilonia (1812) based on the text by Francesco Aventi.

Family table

|

Achaimenes 1st King, Regent of Persia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Teispes 2nd King, Regent of Persia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ariaramna I. 3rd King, Regent of Persis |

Cyrus I. 4th King, Regent of Anzhan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arshama I. Regional Regent |

Cambyses I. 5th King, Regent of Anjan |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hystaspes prince |

Cyrus II. 6th King, Regent of Persia |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dareios I. 9th King, Regent of Persia |

Cambyses II. 7th King, Regent of Persia |

Bardiya 8th King, Regent of Persia (or Gaumata as Smerdis) |

Artystone princess |

Atossa princess |

Roxane princess |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Xerxes I. 10th King, Regent of Persia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Artaxerxes I. 11th King, Regent of Persia |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

swell

- Hanspeter Schaudig : The inscriptions of Nabonids of Babylon and Cyrus the Great, together with the trend writings created in their environment (= Old Orient and Old Testament . Volume 256). Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2001, ISBN 3-927120-75-8 .

- Otto Kaiser (Ed.): Texts from the environment of the Old Testament , volume 1. Old series. Mohn, Gütersloh 1984, ISBN 3-579-00063-2 .

- James B. Pritchard : Ancient near Eastern texts. Pro Quest, Ann Arbor (Mich.) 2005, ISBN 0-691-03503-2 (reprint).

- Adolf Leo Oppenheim : The cuneiform texts. OO 1970 (translations of James B. Pritchard's Ancient near Eastern texts ).

- Joseph Feix (Ed.): Herodots Historien, Greek-German ( Tusculum Collection ). 2 volumes, 5th edition, Artemis, Munich 1995.

- Rainer Nickel (Ed.): Xenophons Kyrupädie, Greek-German ( Tusculum Collection ). Artemis & Winkler, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7608-1670-3 .

- Dominique Lenfant (Ed.): Ctésias de Cnide. La Perse, l'Inde, autres fragments. In: Les Belles lettres , Paris 2004, ISBN 2-251-00518-8 .

literature

Standard works

- Robert Rollinger : Herodotus Babylonian Logos. A critical examination of the credibility discussion on the basis of selected examples - historical parallel tradition - argumentation - archaeological evidence - consequences for a history of Babylon in Persian times. Publishing house of the Institute for Linguistics of the University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck 1993, ISBN 3-85124-165-7 (also diploma thesis, University of Innsbruck 1989).

- Heidemarie Koch : Achaemenid Studies. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03328-2 .

- Josef Wiesehöfer : Ancient Persia 550 BC Chr to 650 AD Patmos, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96151-3 .

- Muhammad A. Dandamayev: Cyrus II the Great . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume 6 (5), pp. 516-521 (English, including references).

- Josef Wiesehöfer: Cyrus 2. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1014-1017.

- Franz Heinrich Weißbach : Cyrus 6. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplement volume IV, Stuttgart 1924, Col. 1129-1166.

- Klaas R. Veenhof : History of the ancient Orient up to the time of Alexander the great. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-51686-X .

- Annemarie Ambühl: Cyrus. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 595-602.

Individual examinations

- Robert Rollinger : The Median Empire, the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great Campaign in 547 BC BC (Nabonaidus Chronicle II 16). In: Ancient West & East , Volume 7 (2009), pp. 49-63 ( online ( registration required ) ).

- Robert Rollinger: The phantom of the medical "great empire" and the Behistun inscription. In: Ancient Iran and its Neighbors. Studies in hour of Prof. Józef Wolski on the occasion of his 95th birthday (= Electrum. Volume 10). Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, Cracow 2005, ISBN 978-83-233-1946-7 .

- Robert Rollinger: Media. In: Walter Eder , Johannes Renger (Ed.): Ruler Chronologies of the ancient world. Names, dates, dynasties (= The New Pauly . Supplements. Volume 1). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2004, ISBN 3-476-01912-8 , pp. 112-115.

- Josef Wiesehöfer : Continuity or caesura - Babylon under the Achaemenids. In: Johannes Renger (Ed.): Babylon - Focus Mesopotamian History. Cradle of earlier learning as a myth of modernity. 2nd International Colloquium of the German Orient Society. Saarbrücker Druckerei und Verlag, Saarbrücken 1999, ISBN 3-930843-54-4 .

- Josef Wiesehöfer: Daniel, Herodotus and "Dareios (Cyrus II) the Medes". In: From Sumer to Homer. Festschrift for Manfred Schretter for his 60th birthday (= Old Orient and Old Testament. Volume 325). Ugarit-Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-934628-66-4 .

- Reinhard-Gregor Kratz: Judaism in the age of the Second Temple (= research on the Old Testament. Volume 42). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-16-148835-0 .

- Mischa Meier : Deiokes, King of the Medes - A Herodotus episode in its contexts (= Oriens et Occidens . Volume 7). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08585-8 .

- Vesta S. Curtis, Sarah Stewart: The Idea of Iran , Volume 1: Birth of the Persian Empire. Tauris, London 2005, ISBN 1-84511-062-5 .

- Wolfgang Röllig : Ran Zadok - Répertoire géographique des textes cunéiformes , Part 8: Geographical names according to new- and late-Babylonian texts. Reichert, Wiesbaden 1985, ISBN 3-88226-234-6 .

- Albert-Kirk Grayson: Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles (= Texts from cuneiform sources. Volume 5). Augustin, New York 1975.

- Jack Cargill: The Nabonidus Chronicle and the Fall of Lydia. Consensus with Feet of Clay. In: American Journal of Ancient History , Volume 2 (1977), pp. 97-116.

- Sidney Smith: Babylonian Historical Texts to the Capture and downfall of Babylon. Olms, Hildesheim 1975, ISBN 3-487-05615-1 (reprint).

- Alireza Shapour Shahbazi: Old Persian inscriptions of the Persepolis platform: plates I-XLVIII (= Corpus inscriptionum Iranicarum. Part 1: Inscriptions of ancient Iran. Volume 1, Portfolio 1). Lund Humphries, London 1985, ISBN 0-85331-489-6 .

- Manfred Mayrhofer: About the Avesta name. Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1977, ISBN 3-7001-0196-1 .

- Mary Boyce : A history of Zoroastrianism. 3 volumes, Brill, Leiden / Cologne 1975–1991.

- Norbert Ehrhardt : Resistance - Adaptation - Integration: The Greek States and Rome. Festschrift for Jürgen Deininger on his 65th birthday. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-515-07911-4 .

- Martin L. West : Early Greek philosophy and the Orient. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-19-814289-7 (reprint).

Web links

- Literature by and about Cyrus II in the catalog of the German National Library

- M. Boyce: Achaemenid Religion (Religions of the Achaemenids) . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of December 15, 1983, accessed on June 8, 2011 (English, including references)

- Declaration of Cyrus - livius.org (PDF)

- Nabonaid Chronicle: Cyrus II in Babylon

- Contents of the Nabonaid Chronicle (Sippar cylinder)

- Sippar cylinder (Nabonaid Chronicle) in the British Museum

- Pictures of the Cyrus tomb ( memento from January 20, 2015 in the web archive archive.today )

Remarks

- ↑ The year of birth is an estimate and taken from the Encyclopædia Britannica (15th edition, 2007, volume 3, p. 831, article Cyrus II. ). The calculation of the year of birth at 600 BC is improbable. After the Greek historian Dinon von Kolophon (quoted in Cicero , De Divinatione 1,23), according to whom Cyrus II was 70 years old because this information is unreliable (as already FH Weißbach, in: Paulys Realenzyklopädie der classical antiquity ( RE), Supplementary Volume IV, Sp. 1157). The year of death is secured by dating cuneiform texts.

- ↑ a b c Josef Wiesehöfer: Kyros 2. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1014-1017, here Sp. 1014.

- ↑ Otto Kaiser: Texts from the environment of the Old Testament , Volume 1 - Old Series; Gütersloh: Mohn, 1985; Pp. 409-410.

- ^ Histories , 1st book, from column 46.

- ^ Richard Laqueur : Nikolaos 20 . In: RE XVII 1, col. 362-424, here: col. 375-390.

- ^ FH Weißbach: Kyros II. In: RE, Supplement IV., Sp. 1129–1131.

- ↑ Plutarch: Artaxerxes 1. 3 ; Photius , Epitome of Ktesias' Persica 52

- ↑ a b Rüdiger Schmitt and Karl Hoffmann in the Encyclopædia Iranica (online)

- ↑ However, Herodotus incorrectly characterized Cambyses I as a middle-class Persian, while Xenophon more correctly describes him as "King of the Persians".

- ↑ Robert Rollinger: The Phantom of the Medic "Great Empire" ; in Edward Dabrowa: Ancient Iran and its Neighbors ; Krakow 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ The year in which Cyrus came to power is estimated after the year of his death (530 BC) and the statement by Herodotus ( Historien 1, 214, 3) that he ruled for 29 years. According to Diodor (Eusebius of Caesarea, Praeparatio evangelica 10,10), Cyrus became king at the beginning of the 55th Olympiad (around 560 BC).

- ↑ In summary Richard N. Frye: Cyrus was no Achaemenid . In: Carlo G. Cereti u. a. (eds.), Religious themes and texts of pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia , Wiesbaden 2003, p. 111ff.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 123–128

- ^ A b Reinhard-Gregor Kratz: Judaism in the Age of the Second Temple ; Study edition from the series: Research on the Old Testament, No. 42; Tübingen: Mohr (Siebeck), 2006; Pp. 44-47.

- ^ FH Weißbach: Kyros II. In: RE, Supplement IV., Sp. 1142-1144; M. Dandamayev: Cyrus II. In: Encyclopædia Iranica , Vol. 6, pp. 517-518

- ↑ Cyrus II . In: Encyclopædia Britannica , 2007, Vol. 3, p. 831.

- ↑ M. Dandamayev: Cyrus II. In: Encyclopædia Iranica , vol. 6, p. 518.

- ↑ Mischa Meier: Deiokes, König der Meder , Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, p. 19.

- ↑ J. Cargill: The Nabonidus Chronicle and the Fall of Lydia ; in: American Journal of Ancient History 2 (1977), pp. 97-116

- ↑ "This reading forms the new basis for all future evaluations". In: Robert Rollinger: The Median Empire, the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great Campaigne 547 BC. In Nabonaid Chronicle II 16 . In: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Ancient Cultural Relations between Iran and West-Asia , Teheran 2004, pp. 5-6.

- ^ Robert Rollinger: The Median Empire, the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great Campaigne 547 BC. In Nabonaid Chronicle II 16 ; in: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Ancient Cultural Relations between Iran and West-Asia ; Tehran 2004, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ a b c Dietz-Otto Edzard: Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology (RLA) , Volume 6; Berlin 1983; P. 401.

- ↑ a b c d e f Dietz-Otto Edzard: Real Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology (RLA) , Volume 6; Berlin 1983; P. 402.

- ↑ According to the fragmentary Nabonidus Chronicle here, Cyrus II killed 547 BC. After a campaign a king; the country, which cannot be precisely deciphered, is now read “Urartu”. The Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea, however, puts the fall of Croesus in the year 547 BC. Chr .; the manuscripts of the chronicle of Hieronymus based on Eusebius vary between 548 and 545 BC. Chr .; the marble Parium mentions the end of the Lydian Empire around the year 541/540 BC. Chr.

- ↑ The most important source for the battle between Croesus and Cyrus II is Herodotus ( Histories 1, 71; 1, 75–81; 1, 83–84).

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Chronicle (Armenian), p. 33, 8-9 ed. Karst

- ↑ Bakchylides 3, 23ff.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 85–87; in Xenophon ( education of Cyrus 7, 2) Cyrus II behaves almost “gentlemanly” towards Croesus.

- ↑ Main report in Herodotus, Historien 1, 154–176

- ^ As the son and public representative of Nabonaid, Belshazzar was only sealed from April 4th to 13th. Year of government, cf. in addition: Klaas R. Veenhof: History of the Old Orient up to the time of Alexander the Great - Outlines of the Old Testament ; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2001; P. 284.

- ↑ a b c Josef Wiesehöfer: Kyros 2. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1014-1017, here Sp. 1015.

- ↑ The Nabonaid Chronicle names the month of Adaruu in the 16th year of the reign and the associated attacks by the Persians.

- ↑ The equation of the name Ugabru with Gobryas is in no way certain. The name Ugbaru is therefore used, which is also listed in the Nabonaid Chronicle. See also Rüdiger Schmitt in the Encyclopædia Iranica online

- ↑ That is the equivalent of October 6th. The beginning of the 16th Tashritu fell in the proleptic Julian calendar in 539 BC. On the evening of October 12th - lasted until the evening of October 13th - and the beginning of spring on March 28th. In conversion to today's Gregorian calendar, 7 days must therefore be deducted. It is not clear whether the date has to be converted to the actual Babylonian lunar or the static annual calendar. Calculations according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms - Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4.5 , Barth, Leipzig 2000 and Ephemeris Tool 4.5 conversion program .

- ↑ Similar to the conquest of Babylon described here after the Nabonaid Chronicle, only Berossus reports of the ancient historians (in Eusebius of Caesarea ( Chronik , p. 15.20 ed. Karst) and Josephus ( Against Apion 150ff.)); The depiction of Herodotus ( Historien 1, 188–191) and Xenophons ( Education of Cyrus 7, 5), that Cyrus II had the Euphrates diverted and thereby penetrated Babylon, is unhistorical .

- ↑ This is the 5th Nisanu. In the proleptic Julian calendar of 538 BC The beginning of the 5th Nisanu fell on the evening of March 27th - the seizure of Marduk's hands on March 28th - and the beginning of spring on March 28th. In conversion to today's Gregorian calendar, 7 days must therefore be deducted. Calculations according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms - Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4.5 , Barth, Leipzig 2000 and Ephemeris Tool 4.5 conversion program .

- ↑ Xenophon, Education of Cyrus 7, 5.

- ↑ Josephus, Kontra Apion 1, 20 § 151-153; u. a.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Praeparatio evangelica 9, 41; u. a.

- ↑ According to the Nabonaid Chronicle on the night of the 11th Arahsamna . In the proleptic Julian calendar of 538 BC The 11th Arahsamna fell on October 25th and the beginning of spring on March 28th. In conversion to today's Gregorian calendar, 7 days must therefore be deducted. Calculations according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms - Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4.5 , Barth, Leipzig 2000 and Ephemeris Tool 4.5 conversion program .

- ↑ In the literature the term “shortly after” is also used and usually the year 539 BC. BC. However, in the Encyclopædia Iranica online ( memento of January 27, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), Rüdiger Schmitt refers to the possibility of “one year”. The Nabonaid Chronicle accordingly also stipulates a one-year term of office.

- ^ Hubert Cancik: The New Pauly (DNP) - Encyclopedia of Antiquity , Volume 6; Stuttgart: Metzler, 2003; P. 219.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 2, 1; 3, 2.

- ↑ According to the Nabonaid Chronicle on Adaru 26th. In the proleptic Julian calendar of 537 BC The 26th Adaru fell on April 4th and the beginning of spring on March 28th. In conversion to today's Gregorian calendar, 7 days must therefore be deducted. Calculations according to Jean Meeus: Astronomical Algorithms - Applications for Ephemeris Tool 4.5 , Barth, Leipzig 2000 and Ephemeris Tool 4.5 conversion program .

- ↑ The first three days were also part of the New Year celebrations, but the processions for the Babylonian population did not begin until the 4th day and lasted until the 11th day

- ↑ According to the Nabonaid Chronicle on Nisanu 4 (8 days after the date of death of the Kassandane).

- ↑ According to documents in the 4th year of Cyrus' reign, cf. Hubert Cancik: The New Pauly (DNP) - Encyclopedia of Antiquity. Volume 4 ; Stuttgart: Metzler, 2003; S. 1126. An exact date is not given in the chronicle. According to the Babylonian counting of the years of reign, the entire year is assigned to the old incumbent, even if he did not reign for the full year. The handover to Gobryas took place in the course of the year 537 BC. Chr .; the nomination as the new incumbent became official from 536 BC. Chr. Noted chronologically.

- ↑ a b c Klaas R. Veenhof: History of the Old Orient up to the time of Alexander the Great - Outlines of the Old Testament ; Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2001; Pp. 288-291.

- ↑ Mary Boyce In: Cyrus II . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- ^ Norbert Ehrhardt: Resistance - Adaptation - Integration: The Greek world and Rome. Festschrift for Jürgen Deininger on his 65th birthday , Steiner, Stuttgart 2002, p. 161.

- ^ Manfred Mayrhofer: On the name of the Avesta , Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1977, p. 10.

- ↑ Herodotus: Historien 1, 204-215.

- ↑ Ktesias, pp. 133 ff. Ed. Gilmore.

- ↑ Aristobulus von Kassandreia , FGrH 139, F 51 in Arrian, Anabasis 6, 29 and Strabo 15, 3, 7.

- ↑ Berossus in Eusebius of Caesarea , Chronik, p. 23, ed. Karst.

- ↑ So FH Weißbach ( Kyros II., In: RE, Supplementvol IV, Sp. 1156) on Xenophon, Education of Kyros 8, 7

- ↑ Strabo 15, 3, 7; Arrian, Anabasis 6, 29.

- ↑ Plutarch, Alexander 69.

- ↑ FH Weißbach: Kyros II. In: RE, Supplement IV, Sp. 1157–1160; Antigoni Zournatzi: The Tomb of Cyrus. In: Encyclopædia Iranica . Vol. 6, pp. 522-524.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 107–130.

- ↑ Nikolaos of Damascus in Felix Jacoby , The Fragments of the Greek Historians (FGrH), No. 90, F 66; on this Ktesias, FGrH 688 F 9.

- ↑ Aeschylus, Persai 472; 770ff.

- ↑ Aristotle, Athenaion politeia 5, 8; 5, 15.

- ↑ a b c d Article Cyrus II. In: Eric M. Moormann, Wilfried Uitterhoeve: Lexicon of ancient figures. With their continued life in art, poetry and music (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 468). Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-520-46801-8 , pp. 409-411.

- ↑ a b Matthias Schulz: Legends - The False Prince of Peace on Spiegel Online from July 7, 2008

- ↑ Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran , p. 39. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30731-8 ( limited online version in Google Book Search - USA )

- ^ Josef Wiesehöfer: Ancient Persia 550 BC. To 650 AD Patmos, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-96151-3 , chapter "Cyrus and Xerxes"

- ↑ Announcement of German Iranists for the 2500 anniversary of Iran , ed. Wilhelm Eilers, Stuttgart 1971.

- ↑ Josef Wiesehöfer: Cyrus, the Shah and 2500 years of human rights, in: Stephan Conermann (ed.), Mythen, Geschichte (n), Identities: The fight for the past, EB-Verlag, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-930826-52 -6 , pp. 55-68

- ↑ Josef Wiesehöfer: Kyros 2. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 1014-1017, here Sp. 1017.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Cambyses I. |

Persian king 559-530 BC Chr. |

Cambyses II |

| Nabonidus |

King of Babylonia 539-530 BC BC Cambyses II. 538 BC Chr. |

Cambyses II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cyrus II |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cyrus the Great |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Founder of the ancient Persian world empire |

| DATE OF BIRTH | uncertain: 601 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 530 BC Chr. |