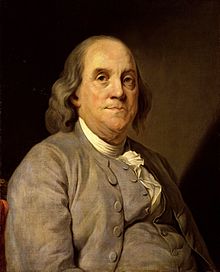

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (born January 17, 1706 in Boston , Province of Massachusetts Bay , † April 17, 1790 in Philadelphia , Pennsylvania ) was an American printer , publisher , writer , scientist , inventor and statesman .

As one of the Founding Fathers of the United States , he participated in the drafting of the United States' Declaration of Independence and was one of its signatories. During the American Revolution he represented the United States as a diplomat in France and negotiated both the treaty of alliance with the French and the Peace of Paris that ended the American War of Independence . As a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention , he participated in the drafting of the American Constitution .

Franklin's life was largely shaped by a will to promote the community. He founded the first volunteer fire departments in Philadelphia as well as America's first lending library and constructed a particularly effective and low-smoke wood stove. He also made scientific discoveries, among other things he invented the lightning rod .

The son of a soap and candle maker, he initially made a career as a printer before retiring from business and entering politics at the age of 42 . His social advancement - supported by his autobiography, which was printed in numerous editions - was for a long time a prime example of how one can work one's way up with one's own strength and discipline.

life and work

Early Years: Boston, 1706-1723

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17th, 1706 (January 6th of the Julian calendar ) as the 15th child of soap and candle maker Josiah Franklin in Boston , Massachusetts . His ancestors came from the village of Ecton in the central English county of Northamptonshire . In his autobiography, Benjamin Franklin later stated that his father emigrated to America because as a Puritan he could freely practice his faith there. In fact, it was probably also economic pressure that prompted Josiah to board a ship for Boston in 1683 with his first wife Anne Child and their three children. Wages in the New World were three times higher than in England, and at the same time the cost of living was lower.

Josiah's first wife died in 1689, and only months later he married Abiah Folger. She came from a family who had come to Boston with the first wave of Puritan immigrants . Together they had eight children, of whom Benjamin was the second youngest.

To prepare him for a degree at Harvard and a later career as a pastor, Josiah sent his son Benjamin to Boston Latin School at the age of eight . There his great talent was shown early on. He was one of the best students and skipped a class. Despite these successes, his father enrolled him in another school for a year, where he was supposed to learn writing and arithmetic . While Benjamin Franklin claimed in his autobiography that this was due solely to his father's low income, biographers such as Walter Isaacson assume that Josiah Franklin recognized the rebellious nature of his son early on and therefore decided that he was unsuitable for a spiritual career.

At the age of ten and after only two years of schooling, Benjamin started working in his father's shop. Two years later, Josiah finally apprenticed him to his older son James, a printer. In 1721 he founded his own newspaper, the New England Courant . Benjamin Franklin published his first article in this newspaper. As an apprentice printer, he had easier access to books, and as an avid reader he also began to take an interest in writing. Under the pseudonym "Mrs. Silence Dogood ”he wrote humorous and critical essays on social issues that he pushed under the door of his brother's print shop at night. His attacks on the closeness between church and state and thus on one of the pillars on which life in the Puritan colonies of New England rested were particularly biting . A parallel comment from James Franklin ("Of all villains, the pious villain is the worst.") Prompted the authorities to stop James Franklin from acting as editor of the Courant . In February 1723, the newspaper appeared briefly under the name Benjamin Franklins. But James Franklin quietly took over the management again. When Benjamin finally revealed to him that he himself was behind the pseudonym Silence Dogood , James felt betrayed. So far he had praised the writer behind the pseudonym in the highest tones. But now James was disappointed and jealous - and even let himself be carried away to harass and beat his brother. This led to the break between the two brothers. First Benjamin tried to get an apprenticeship at another printer in Boston. When this failed, the seventeen year old ran away from home and secretly embarked for New York .

Printer: Philadelphia and London, 1723-1732

Employed as a printer in Philadelphia

On the crossing to New York, Franklin met the printer William Bradford. From this he learned that New York did not have its own newspaper and Bradford was the only one of his guild there. So the printer had no use for Franklin, but recommended him to his son Andrew in Philadelphia . But even with the young Bradford there was no job available, so that only a renewed placement by William Bradford brought success. Franklin got a job with Samuel Keimer, who had just started his own printing company in Philadelphia.

When his brother-in-law Robert Holmes found out where Franklin was, he wrote to him requesting that he return to Boston for the sake of his family. In his reply, Franklin listed the reasons why he considered a life in Philadelphia more worth living. This letter came into the hands of the Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania, William Keith . Keith was impressed with Franklin's writing skills and contacted him immediately. He promised to help him open his own print shop in Philadelphia and sent him back to his father with a letter of recommendation.

In April 1724, Franklin sailed for Boston. Despite his pride in his son's accomplishments, Josiah Franklin refused to support his plans. Thereupon Franklin returned to Philadelphia without having achieved anything.

Stranded in London

On the advice of William Keith, Franklin traveled to London in November 1724 . There he was supposed to buy the equipment for his own printing house with the financial help of the lieutenant governor and to establish contacts with the London-based printers and paper manufacturers.

Upon his arrival, Franklin found that Keith had not kept his promise of financial support. Destitute and far from home, he tried to make the best of the situation and worked for various printing companies. The production of an edition of William Wollaston's The Religion of Nature Delineated inspired him to write his own work entitled A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain , which he had printed at his own expense during the first six months of his stay in London. At the same time he made contacts with Hans Sloane , who later became President of the Royal Society .

On his crossing to Europe, Franklin met the Philadelphia merchant Thomas Denham. Impressed by the Quaker's moral integrity , he made a "Plan for Future Conduct " in which he subscribed to the maxims of frugality, sincerity and ambition. When Denham offered him a partnership, they both returned to Philadelphia in July 1726.

Self-employed printer

Franklin's partnership with Denham ended after a few months when Denham died unexpectedly. Franklin then returned to Samuel Keimer's print shop, this time as managing director. In this function he developed a typeface that is considered the first on the North American continent. To commemorate this achievement, the well-known typographer Morris Fuller Benton developed a font family by 1902 that bears the name Franklin Gothic . Franklin himself mainly used a Caslon .

Together with one of Keimer's employees, journeyman Hugh Meredith, Franklin eventually went into business for himself. In early 1728, the equipment ordered in London for their own print shop arrived. The printing company flourished - not least because of Franklin's zeal and ambition. The partnership with Meredith did not last long. When he became addicted to alcohol, Franklin ended the collaboration and - with the financial help of two friends - was ultimately his own boss.

In October 1729, Franklin von Keimer took over the Pennsylvania Gazette and became a newspaper publisher. Like many other daily newspapers, the Pennsylvania Gazette contained not only newsflashes, announcements, and reports of events of public interest, but also amusing essays and letters to the editor, some of which Franklin himself had written under pseudonyms. The concept of his newspaper was successful. Since the early 1730s he has partnered with some of his former apprentices; they set up their own printing works in towns along the east coast and were supplied with printing presses and newspaper articles by Franklin. In return, they paid him part of their income.

Franklin was proud of the profession he had learned. He referred to himself as a printer until the end of his life. His will begins with the words "I, Benjamin Franklin from Philadelphia, printer".

The Junto Self-Education Club

In the fall of 1727 Franklin founded a self-education club, the Junto . His club consisted of entrepreneurs and artists and thus not of members of the social elite from which the traditional gentlemen's clubs were recruited. When they were accepted, applicants had to answer four questions: whether they disregarded one of the club members, whether they respect other people - regardless of religion or profession - whether a person may be persecuted because of their views or religious affiliation, and whether the applicant is truthful about theirs loved one's own sake. The topics discussed during the Junto's meetings ranged from asking why condensation formed over a cold jug to questions like “What makes a person happy?” Or “When a government denies a citizen his rights, he has one Right to resistance? "

From the earliest meetings, Franklin also used the junto to discuss practical suggestions for improving everyday life in the colony. For example, the members discussed whether Pennsylvania should increase the amount of paper money in circulation - a proposal that Franklin favored, not least because of his own business interests. When the club finally moved into its own rooms, these were furnished with books from the members' possession. In this way the basis of America's first lending library was created .

“The passions of youth, which are difficult to curb, often plunged me into love affairs with socially lower women who I ran into” - this is how Franklin describes the time before he lived with Deborah Read. As an aspiring businessman, especially with high moral standards, he could no longer afford such behavior. So in the summer of 1730 he entered into a marriage union with Deborah Read.

Franklin had met Deborah in 1724 and asked for her hand even then. Her mother, however, insisted that the wedding should take place only after his return from London. Franklin did not pursue the matter further and so the two lost sight of each other for several years. In the meantime, Deborah married a certain John Rogers, who fled to the West Indies and left his wife in debt. Although there were rumors that Rogers was killed in a brawl, Deborah and Benjamin Franklin ended up having only a " common law " marriage. In this informal type of marriage, the partners lived together without having officially married. For the couple, this was the only viable solution, as bigamy was punished with 39 lashes and life imprisonment.

But there was another complication to the young marriage. Franklin had a son with one of those "socially inferior women" around the same time. William Franklin was born sometime between April 1730 and April 1731 and was supposed to become Governor of New Jersey in 1762. Deborah could not stand this illegitimate child all her life and is said to have called it - according to the testimony of a domestic worker - "the greatest villain on this earth".

Benjamin and Deborah Franklin had two other children together: Francis Folger Franklin (1732–1736), who died of smallpox while still a child , and Sarah Franklin Bache (1743–1808), who in 1767 married the merchant Richard Bache.

Popular yearbooks: Poor Richard's Almanack

Franklin's best-known alter ego became the fictional character Richard Saunders (Poor Richard) . He invented the character for his Poor Richard's Almanack , a yearbook that he printed from 1732 on. Such yearbooks were extremely popular at the time, making them a welcome source of income for printers and publishers. In Philadelphia alone, six of these annual fonts came onto the market. The name Poor Richard's Almanack was based on the Poor Robin's Almanac published by Franklin's brother , and Richard Saunders was the name of an almanac writer in England at the end of the 17th century.

With the character of Poor Richard , Franklin helped, as his biographer Walter Isaacson put it, “to define what became a dominant tradition of popular humor in America”: the naive type of down-to-earth character who is sharp-tongued, wise and charmingly innocent was.

Poor Richard not only contributed the respective forewords to the yearbooks, but also a series of maxims that are still popular today, such as "Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise" (Eng., For example, "Going to bed early and getting up early." make a man healthy, wealthy and wise ”). These maxims were by no means an invention of Franklin. Rather, his performance consisted of reformulating existing sayings and thus getting them to the point better.

What was initially only conceived as filler material for his yearbook, developed into a bestseller as an independent publication. The collection of sayings The Way to Wealth was one of the most famous books from the American colonies. Within forty years it was reprinted in 145 editions and to date has been sold in more than thirteen hundred editions.

Citizenship: Philadelphia, 1731–1748

The Library Company of Philadelphia

In 1731, on Franklin's initiative, the Library Company of Philadelphia was founded as America's first lending library . The collection of the Junto Club founded by Franklin formed the basis of books . Each member of the Library Company had to pay a fixed contribution, from which additional books were purchased. The volumes could only be borrowed by members, but they were also available to any other citizen of Philadelphia to read.

Franklin himself said he spent an hour or two a day in the library, making up for the lack of formal education his father once had in mind for him. His commitment also benefited him in other ways: while the Junto Club consisted mainly of business people, Franklin now came into contact with members of higher social classes. For example, he developed a lifelong friendship with the English botanist and member of the Royal Society Peter Collinson , who sent the first book delivery for the Library Company from London to Philadelphia.

The Library Company of Philadelphia is now one of the oldest cultural institutions in the United States , with an inventory of more than 500,000 books and over 160,000 manuscripts.

Establishment of volunteer fire brigades

Although no city in the American colonies had experienced a fire disaster on the scale of the Great Fire of London , the risk of fire was a constant concern in everyday colonial life even in Franklin's time. The experiences from that conflagration of 1666 were directly incorporated into the planning for the city of Philadelphia. The streets were wider and the houses were further apart than they were in London. But the constant influx of immigrants ensured that the rooms became cramped and the risk of fire increased.

"An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure," wrote Franklin in an anonymous letter to the Philadelphia Gazette readers , suggesting the establishment of volunteer fire-fighting associations. Following the example of Boston, citizens should band together in small groups to fight fires.

In December 1736, the Union Fire Company was the first of these alliances. The twenty-five founding members were made up of members of the Junto, the Library Company , merchants, and a number of other citizens who cared about the protection of their belongings. After a short time, other groups formed and took up Franklin's idea.

The American Philosophical Society

Before Franklin, the botanist John Bartram had presented the plan to found an American learned society based on the model of the London Royal Society . As a printer, however, Franklin had the journalistic resources to spread the idea and ultimately to ensure its implementation.

In May 1743 he published A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge Among the British Plantations in America . The subjects to be discussed by the scholars, like much of what Franklin suggested, were more utility than theoretical. For example, discoveries in the field of crops, trade, land surveying, the manufacture of goods, animal breeding and other practical topics should be made known to one another.

From the spring of 1744, the American Philosophical Society began its regular meetings in Philadelphia. The founding members included Franklin, the scientist John Bartram and the doctor and later Governor of New York, Cadwallader Colden . Later some of the American founding fathers such as George Washington , John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were also accepted into the society.

While the members of the American Philosophical Society did not develop any particular activity in the first few years - Franklin himself spoke of them as "very idle gentlemen" - the society has endured the ages and still exists today.

Foundation of a citizens' militia

From 1689 the French and English colonies in North America fought for control of the western hinterland territories. This conflict, known in the USA as the French and Indian Wars, entered a new phase with the beginning of King George's War in 1744. This war threatened the security of Philadelphia when French and Spanish privateers began raiding the cities along the Delaware .

When the pacifist Quaker- ruled Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly hesitated to put in place appropriate defensive measures, Benjamin Franklin intervened. In November 1747 he published a pamphlet entitled Plain Truth (dt. The Naked Truth ), in which he denounced the indecisive attitude of the governors of Pennsylvania and the formation of a militia called. Only a union of the middle class, traders, shopkeepers and farmers, could save the colony. His proposal was radical because the citizen militia proposed by Franklin should expressly not be structured according to class, but according to geographical criteria. The individual companies should be led by officers of their own choice and not by those of the colonial administration.

Shortly after the publication of the publication, tens of thousands of volunteers enrolled in the registers of Franklin's carefully planned volunteer companies. What the militia lacked were cannons. Since the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly refused to provide funds for the purchase of weapons, Franklin organized a lottery, from the proceeds of which he procured cannons himself in negotiations with the governor of New York .

In the summer of 1748 the danger was over without the militia ever being used. What remained after the dissolution of the Pennsylvania Militia was Franklin's insight that the residents of the colony would have to take care of their welfare on their own in an emergency. Thomas Penn , son of William Penn , the founder of Pennsylvania, referred to Franklin in a letter as a “ tribune of the people ” and complained, “He is a dangerous man and I would be glad if he lived in another country because I believe he is is of an extremely restless spirit. "

Retreat from business life

In 1737 Franklin had taken over the post of Philadelphia postmaster from his rival Andrew Bradford . He not only had his own printing and publishing company, but also had an influence on the distribution system for his newspapers and other printed products. In addition, he had gradually built a network of profitable partnerships with printers along the east coast.

Well, at the age of 42 - exactly in the middle of his life - he largely withdrew from business life. He left the operation of his print shop to his foreman, David Hall. The deal with this stipulated that Franklin would receive half of the printing revenue for the next eighteen years, which amounted to about £ 650 annually. At a time when a simple clerk could earn around £ 25 a year, that was enough for a comfortable life.

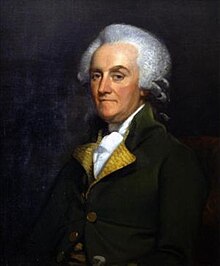

His new social status as a "gentleman philosopher" was recorded in an oil painting that the painter Robert Feke made of him in 1748. It is also the first known portrait of Franklin and depicts him - as the art historian Wayne Craven puts it - as a "member of the colonial merchant class who was successful but not really rich."

Scientists and Inventors: Philadelphia 1744–1751

The "Pennsylvania Fireplace"

Throughout his life, Franklin had a keen interest in scientific discovery. In the 1740s, especially after his retirement from business life, his preoccupation with natural phenomena reached a peak. Again, the practical use was the focus of his considerations.

Since the early 1740s, Franklin pondered how a wood-burning stove should be designed to maximize heat recovery while reducing smoke levels in the home. Building on his knowledge of convection and heat conduction , he designed a new type of furnace, which he had one of the Junto members, a blacksmith, build from 1744. The stove was designed so that the heat and smoke from the fire heated a hotplate and then passed through a duct behind the wall into a fireplace.

Called the "Pennsylvania Fireplace" by Franklin, the stove cost five pounds and was advertised by its inventor in numerous newspaper advertisements. When the Governor of Pennsylvania offered Franklin a lucrative patent for his new development, Franklin replied, “As we benefit from the inventions of others, we should be grateful for every opportunity to serve others through our inventions. And we should do this freely and generously ”.

Ultimately, however, the oven designed by Franklin failed to achieve great sales success. The initial heat build-up was not enough to effectively evacuate the smoke, so most of the Pennsylvania Fireplaces were converted into ordinary stoves by their owners.

First research on electricity

On a visit to Boston in 1743, Franklin had attended a performance by Archibald Spencer, where he had entertained the audience with a performance on electricity . Franklin was enthusiastic about the phenomenon of electricity. He wrote of Spencer's performances: "They surprised me and I liked them at the same time". Such demonstrations were very popular at the time. The French scholar Abbé Nollet , court scholar of Louis XV. , entertained the king and his entourage with a performance in which a human chain was struck with a blow from a Leyden bottle - an early condenser - causing the subjects to twitch.

In his first own experiments on electricity, Franklin investigated the nature of electrical charge . In experiments with a glass tube that was electrostatically charged by friction , he found that the sum of the electrical charges present in every closed system remains constant (principle of charge retention ). Franklin spoke of “a type of charge” that only changes its location and thus causes a positive or negative charge. In doing so, he disputed the "two- fluid theory ", which had been valid up to that point and was advocated by the Abbé Nollet , according to which electrified bodies are surrounded by two types of electricity, the effluvium and the affluvium . To explain his new finding more clearly, Franklin coined the terms “plus” and “minus”.

His research on electricity took Franklin in five letters to the Fellow of the Royal Society Peter Collinson in London during the period 1747 to 1750 together, the Collinson of the Royal Society presented and 1751 separately as experiment and Observations on Electricity, Made at Philadelphia in America published .

Invention of the lightning rod

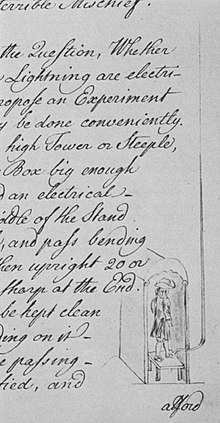

Franklin found that electrostatic discharge looked astonishingly similar to lightning. He found out that electrical charges are attracted to metal tips. In April 1749 he described his observations of thunderstorms in a letter to John Mitchell , geographer and member of the Royal Society in London: “When electrified clouds over a country, high mountains, tall trees, towering spiers, church spiers, masts of ships, chimneys, etc. . pull, then these draw the electric fire to them and the entire cloud is discharged there. "

In order to prove his thesis of the electrostatic charging of thunderclouds, Franklin developed his so-called "Sentry-box experiment" (German: Schilderhaus-Experiment ). For this purpose, a sentry house was to be placed on a tower , which was provided with a long iron rod protruding into the sky. The thunderstorm electricity was to be transmitted via the iron rod to a man standing in the sentry house, who produced sparks to prove the electrostatic charge of the cloud. If his hypothesis of the electrostatic charging of thunderclouds could be proven, so Franklin wrote to Peter Collinson in 1750, then "the electric fire can be silently derived from the cloud". A corresponding experiment was carried out on May 10, 1752 in Marly-la- Ville in France carried out under the direction of the naturalist Thomas François Dalibard , who took his inspiration from Franklin's treatise, which he had sent to Buffon , who in turn gave it to Dalibard for translation.

He also suggested an experiment using an electric kite to collect electricity in a storm cloud to prove the electrical nature of the lightning bolts. Whether and how he actually carried out the experiment is controversial. Franklin reported on it in the Pennsylvania Gazette on October 19, 1752 without explicitly disclosing whether he had carried out the experiment himself. This is what Joseph Priestley claimed in his book The History and Present State of Electricity of 1767, who probably got the information from Franklin himself ( from the best authority ). According to Priestley, Franklin carried out the experiment with his son in June 1752, a month after Dalibard's experiment in France.

Franklin's ideas caused a sensation in Europe. Excerpts of his correspondence with Peter Collinson were reprinted in The Gentleman's Magazine and published the following year in the form of an eighty-six page manuscript. The French king commissioned the experimental verification of Franklin's hypothesis and was enthusiastic about the result in a letter to the London Royal Society. Without his knowing it, Franklin had become a scientific celebrity in Europe. Peter Collinson enthusiastically wrote in a letter that the King of France had particularly insisted on “congratulating Mr. Franklin of Philadelphia for his useful discoveries in the field of electricity and the use of the pointed poles to prevent the terrible effects of thunderstorms can. ”But the invention also met with resistance; In France, for example, Abbé Jean-Antoine Nollet , who had been considered the leading French expert on electricity at the time and who felt ignored by Buffon and Dalibard, was a scientific opponent of Franklin's ideas about lightning rods. In addition, when the experiments were repeated, deaths occurred - the death of Georg Wilhelm Richmann in Saint Petersburg caused a particular sensation - which made their dangerousness clear.

Other inventions

Franklin is considered to be the inventor of the glass harmonica , the flexible urinary catheter , an early form of swim fins and bifocal glasses . In 1784, in a letter to the Journal de Paris , he calculated the enormous economic benefits of shifting the daily routine to make better use of daylight - an idea that was later realized in the form of summer time .

Politician: Philadelphia 1748–1756

Start of political career and framework in Pennsylvania

In 1748 Benjamin Franklin was elected to the Philadelphia Common Council , a precursor to what is now the Philadelphia City Council. A year later he was appointed justice of the peace and in 1751 councilor of the city of Philadelphia. He soon gave up the office of justice of the peace because his legal knowledge was apparently insufficient. That same year he was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly , the House of Representatives for the Pennsylvania Colony . He later commented on the move by saying, “I realized that my calling [MP] would increase my ability to do good. However, I cannot deny that I felt flattered by all of these elevations [into public office]. "

As an owner colony, Pennsylvania was not under the direct control of the British Crown, but of the Penn family. In 1681 the English King Charles II had issued a letter of protection to the Quaker William Penn , which identified the colony as his property. The second political force alongside Penn and his successors were the colony's long-established families. As the local elite, they ruled the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly and traditionally held the most important public offices. Between these two forces and the much larger group of the rest of the Pennsylvania population there was a recurring tension during the first half of the 18th century. In addition, Pennsylvania faced two major challenges in the 1850s: improving relations with the Indians and defending the colony against the French.

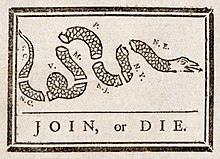

“Join, or Die”: the Albany Congress

For the French, Ohio, west of Pennsylvania, played an important bridging role in their strategy against the British. Ohio combined their possessions in Canada with Louisiana ; by setting up a chain of forts along the Ohio River , they tried to limit the British sphere of influence to the east of North America and to prevent further expansion of the British to the west. Faced with this threat, the London Board of Trade convened a conference in Albany , New York . The aim was on the one hand to negotiate with the emissaries of the Iroquois about their support, and on the other hand to coordinate the joint action of the Thirteen Colonies .

Benjamin Franklin was one of four Pennsylvania officials sent to Congress in Albany . In his luggage there was a paper entitled Short Hints towards a Scheme for Uniting the Northern Colonies (German: Brief Notes on a Plan to Unite the Northern Colonies ). He hoped this plan would be negotiated at the conference and then put to a vote in the UK Parliament in London. His plan anticipated what would later become the basis for the relationship between the individual states and the federal government of the United States : American federalism . A General Council (General Council) of the Thirteen Colonies should be responsible with the Indians for common issues such as the defense and treaties. This council should consist of delegates from all colonies and be headed by a governor-general appointed by the crown .

The Albany Congress met between June 19 and July 11, 1754. The alliance with the Iroquois came about after just a week. On July 10th, delegates voted on Franklin's plan. There were some votes against, but overall there was agreement that the draft should be sent to the Houses of Representatives in the individual colonies and to the British Parliament in London for ratification.

The result was sobering. Despite a public debate initiated by Franklin, the plan was rejected by all of the colonies. The London Board of Trade also spoke out against the change. In retrospect, Franklin later wrote: “The Houses of Representatives [of the colonies] rejected [the proposal] because they all believed that it contained too many [royal] prerogatives ; and in England he was seen as too democratic . "

Tensions in Pennsylvania

Subsequently, tensions between the political forces in Pennsylvania began to grow under military pressure on the colony. While the French and their allied Indians invaded Pennsylvania and killed settlers, the owners of the colony and the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly were at odds over how to raise the defense costs. The Penns, on the one hand, refused to tax their extensive land holdings and, on the other hand, the Assembly of Representatives insisted that all residents of the colony should pay for their defense.

In November 1755 Lieutenant Governor Robert Hunter Morris received a letter from London in which the Penns announced that they would provide a sum of £ 5,000 "as a gift" for the defense of the colony. In the meantime, at Franklin's request, the Assembly of Representatives had decided to set up a citizens' militia modeled on the 1747 model. Franklin was not only tasked with setting up the force, but was also sent to the border to organize the defense lines. On his return he was elected Colonel of the Philadelphia Regiment. For his part, from London, Thomas Penn ordered the formation of regiments under the command of Morris. To prevent a possible clash between the rival units, Franklin eventually gave up his post.

In January 1757, the Pennsylvania Assembly of Representatives decided not to accept the attitude of the owner family on the tax question any longer and sent Franklin to London as their agent.

For the first time on a larger stage: London 1757–1762

A new chapter in life began for Franklin with his trip to London. His experiments on electricity had brought him attention in the scientific world, especially in Europe. In contrast, the effectiveness of his political work has so far been limited to the colonies. He had implemented a number of proposals to improve public life at the local level in Philadelphia and, as his biographer HW Brands put it, "stimulated the imagination of many of his fellow men in America" with his plan for a Union of Colonies. In London, on the other hand, Franklin's work in politics counted little. "Its popularity means nothing here," wrote Thomas Penn. "The big ones [of this country] will treat him very coldly."

Penn turned out to be right in this assessment. Right at the start of his mission, Franklin requested a meeting with William Pitt , one of the most influential men in Britain. But Pitt refused to see Franklin. "He was too big a man at the time," Franklin later attempted to explain, "or too busy with more important matters."

So in August 1757 Franklin began to negotiate directly with Thomas Penn and his brother Richard. Right at the start of the talks, the two Penns asked him for a written version of his positions. Franklin titled his paper, filed two days later, "Major Complaints," calling the owners' refusal to tax their landed property "unjust and cruel." Even more provocative was the informal style in which the letter was drafted and the fact that Franklin did not address the Penns by their correct title as "True and Absolute Proprietaries". So snubbed, the Penns broke off the conversation and asked him to initially only communicate with them through their lawyer.

The situation worsened when Franklin and Thomas Penn clashed during a meeting in January 1758 over the status of the House of Representatives. While Franklin insisted that the charter issued by the King of England in 1682 gave the House of Representatives all the rights of a parliament, Penn replied that the charter had no power to grant such rights. Thereupon Franklin held Penn against that his father William Penn had "misled, betrayed and betrayed" the colonists. To which Thomas Penn replied laconically that the colonists should have read the charter carefully and that if they were misled it was their own fault.

Franklin's conclusion from the matter was that the conversion of Pennsylvania from an owner to a crown colony was more desirable than the continued rule of the Penns. Franklin's position was not only determined by his aversion to the owner family, but also by a deep loyalty to the royal family and the government in London. Franklin's biographer Gordon S. Wood explains this point in Franklin's political life, which seems difficult to understand from today's point of view, with the fact that Franklin at that time believed in unshakable fidelity in the British royal family and in no way foresaw what would happen later.

The meeting with Thomas Penn in January 1758 marked a turning point in Franklin's mission. Penn refused to meet again, and there was no majority in London to convert Pennsylvania into a crown colony.

Meanwhile, Franklin spent his summers traveling. He had brought his son William to Europe and they visited Scotland and the continent together. He met with famous scholars such as Adam Smith and David Hume and received an honorary doctorate from the University of St Andrews . In the summer of 1762, five years after arriving in London, Franklin decided to return to Pennsylvania. Shortly before, his son William had been appointed governor of New Jersey . Franklin no longer waited for Williams to marry Elizabeth Downes, the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner. While he had prematurely broken off a trip to Europe the year before in order to see the coronation of George III. to be present in London, he was already on a ship bound for America during the wedding of his illegitimate son.

Interlude at home: Philadelphia 1763–1764

As early as 1753 Franklin and William Hunter from Virginia had been appointed Deputy Postmaster for the British colonies in North America. Together with Hunter, he had enacted detailed regulations to make the postal system in the colonies more efficient, thus reducing the transit time of a letter from New York to Philadelphia by one day. After returning home, he went on a seven-month trip to inspect the postal system. With John Foxcroft, who had taken over the office of the late Hunter, Franklin expanded the postal network to Canada (Canada fell to Great Britain in the Peace of Paris in 1763 ). At the same time, they set up a parcel ship route to the West Indies and ensured that mail riders also traveled at night. On some key routes, such as the one from New York to Philadelphia, letter transit times were achieved in this way that were not undercut even two centuries later. For example, a letter writer in Philadelphia could expect a response from New York just a week after sending his letter.

When Franklin returned to Philadelphia, the old conflict with the Pennsylvanian family who owned it flared up again. This went so far that Lord Hyde , as General Postmaster Superior of Franklin in London, reminded him that "all officials of the Crown" are obliged to "support the state authority." Notwithstanding such warnings, Franklin drafted a petition calling for the impeachment of the Penns demanded. After a controversy that was also fierce in public through pamphlets , Franklin's supporters finally prevailed in the assembly and voted with 19 to 11 votes in favor of sending Franklin to England with this petition.

Colonies advocate: London 1765–1775

Stamp Act controversy

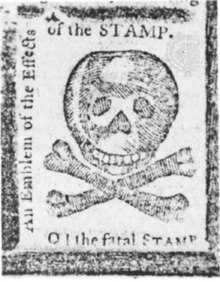

When the news of Franklin's safe arrival in London became public, church bells rang in Philadelphia. But the enthusiasm should lie quickly when Franklin in the controversy over the Stamp Act (Engl. Stamp Act ) was drawn. This stipulated that all official papers and documents, but also newspapers, card and dice games in the North American colonies had to be stamped with stamps or stamped on paper specially made in London. In this way the colonies were to be given a financial share in the stationing of British troops in North America. The British government took the position that the colonists, as beneficiaries of this military protection, should bear part of the costs.

In early February 1765, Franklin and a number of other plenipotentiaries from the colonies met with British Prime Minister and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Grenville . Grenville explained that the Indian threat made it necessary to levy a tax to finance military protection. When asked how this funding could be secured, Franklin suggested that the British government should leave the implementation of the taxation to the colonies. These alone have the right to collect such taxes from their residents. When asked whether the plenipotentiaries could guarantee the income and the distribution of the tax revenue between the individual colonies, Franklin and his colleagues did not have a satisfactory answer.

When the Stamp Act was passed in March 1765, Franklin took a pragmatic stand. He proposed his friend John Hughes for the post of tax collector, wrongly assuming that the excitement about the law would soon subside. In a letter to Hughes he wrote: “In the meantime, a steadfast loyalty to the crown and a loyal adherence to the government of this nation [...] will be the wisest course for you and me, whatever the madness of the common people [...] should be."

Franklin had apparently completely underestimated the resistance of the "common people". What modern biographers like Walter Isaacson rate as his "worst political misjudgment" began to turn against Franklin. When his position in the colonies became public, an angry mob tried to storm Franklin's Philadelphia home. It was only thanks to the intervention of a group of his supporters that the crowd broke up again.

Gradually Franklin realized that he had misjudged the situation in the colonies from afar. He began a defense campaign with letters addressed to his partner David Hall and other addressees in North America. In his letters he denied having ever supported the Stamp Act. He designed a political cartoon entitled The Colonies Reduced and had it printed on cards and distributed in front of Parliament in London. In a session of parliament on February 13, 1766, he was finally given the opportunity to present his changed attitude. He spent an afternoon answering parliamentarians' questions and restoring his reputation in the colonies by appearing as a prominent representative of American interests. When the Stamp Act was repealed in March 1766, a ship named The Franklin fired gun salutes in his honor in Philadelphia Harbor. Franklin's friend Charles Thomson wrote to him: "Your enemies finally began to be ashamed of their mean insinuations and to acknowledge that the colonies owe you thanks".

The autobiography

Franklin began writing his autobiography while staying at his friend Jonathan Shipley's country estate in 1771 . He was to continue this work over a period of almost nineteen years in a total of four sections - but at his death the work was unfinished.

It starts with a long letter to his son William, the then governor of New Jersey. The autobiography was nevertheless intended for a wider audience from the start. Franklin's goal was to portray his own rise from a humble background to a wealthy and respected personality. With this he connected the wish that others should emulate his example. His biographer Charles van Doren notes that Franklin "wrote for a middle class that had few historians [at the time]."

The judgments of Franklin's autobiography differ. The literary critic Charles Angoff complains that it lacks everything that makes a really great work of the Belles Lettres : grace of expression, magic of personality and intellectual height. The historian Henry Steele Commager , on the other hand, emphasizes the unaffected simplicity, clarity, simplicity in style, freshness and humor that made the work recommendable for every new generation of readers. To date, the text has appeared in several hundred editions, making it one of the most popular autobiographies in history.

The Hutchinson Letters Affair

In the early 1770s, Franklin still believed he could settle the dispute between the colonies and the motherland. This belief led to the 1773 Hutchinson Letters affair, which Franklin's biographer Gordon S. Wood described as "the most extraordinary and illuminating event in Franklin's political life." The affair, Wood said, "effectively destroyed his position in England and eventually made him an independent advocate."

In the late 1760s, Thomas Hutchinson , Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts , had written a series of letters to British Foreign Secretary Thomas Whately . In these letters he had spoken out in favor of a tough stance towards the colonies and in particular recommended that their freedoms be curtailed. After Whately's death in 1772, these letters had fallen into Franklin's hands. He sent them to Massachusetts to prove that the fault for the crisis between the colonies and the motherland lay not with the British government, but rather with colonial officials like Hutchinson. If only the real cause of the crisis emerged, Franklin believed, hostility to the British government in the colonies would end.

As before with his hope of converting Pennsylvania into a crown colony and his initial stance on the stamp law, Franklin misjudged the real situation this time too. He had hoped that the Hutchinson letters would only circulate in a small circle in the colonies. Instead, they were printed in June 1773 and caused a scandal. After the letters became public in England, Franklin finally had to admit publicly that it was he who had sent them to Boston.

The mood in London heated up further when Franklin wrote two anonymous satires for the English newspapers that same year , in which he ridiculed the conduct of the motherland towards the colonies. The first satire was entitled Rules by Which a Great Empire May be Reduced to a Small One (German about rules by which a large empire can be transformed into a small one ). In it he listed twenty suggestions how Great Britain could behave towards its colonies in order to further separate the two sides. Among them were suggestions such as "Take special care that the provinces [...] do not enjoy the same rights and the same trade privileges [as the motherland] and that they are governed by stricter laws" or "Quarter troops with them because of their cheek Can provoke uprisings of the mob ”. The second satire, entitled An Edict by the King of Prussia, was a fictional edict of the Prussian King Frederick II. In this bogus announcement, Franklin had Frederick the Great argue that the Germans had sent settlers to England a long time ago and therefore now have income from them Prussian colonies in Great Britain should flow to Prussia. In addition, it would be possible to send Prussian prisoners to England and to populate the colonies on the island in this way. For those readers who did not understand the point of satire, Franklin added that these measures were only fair because they accurately mirrored what Britain was doing against its colonies in North America.

When news of the Boston Tea Party reached London in January 1774 , the wrath of the British government focused on Franklin's person. On January 29, he was summoned before the Privy Council and had to endure a rant from Assistant Attorney General Alexander Wedderburn . Shortly afterwards, he lost his position as Deputy Postmaster .

When the mood against the colonies worsened a year later and his wife Deborah had died in Philadelphia in the meantime, Franklin finally boarded a ship at the end of March 1775 and returned to America.

First Steps to Independence: Philadelphia 1775–1776

Congressman

When Franklin arrived in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, the fighting between British troops and colonists had already begun with the skirmishes of Lexington and Concord . Franklin was delighted with the way things were. He told a reporter that only a brave resistance could save Americans from "the deeply despicable slavery and destruction."

The day after his arrival, Franklin was elected to the Second Continental Congress, which was due to begin work on May 10th. At nearly 70 years of age, he was by far the oldest MP. He was noticeably calm during the debates. Members of Congress like John Adams even complained that Franklin sat in his chair for long stretches of the day and slept.

Nonetheless, the delegates were impressed by the vehemence with which Franklin took a stand for the cause of independence. John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail , "He [Franklin] does not hesitate to agree to our most daring measures, but on the contrary seems to think we are too indecisive and backward-looking". Historians like Gordon S. Wood consider Franklin's revolutionary zeal to be well calculated. There were still voices in the colonist camp who regarded Franklin as anything but a man of independence and even saw him as a British spy. Franklin countered these allegations by drafting a hostile letter to longtime friend William Strahan in London and closing it with the words, “You and I have long been friends. Now you are my enemy and I am yours ”. Franklin never mailed this letter, only showed it to a few of his friends. Only days later he began to write to Strahan again in his usual warm tone.

The personal side of the revolution: break with William

Even if Franklin's revolutionary zeal may have been calculated in part, the revolution also had very personal effects on him. In 1762 his son William had been appointed governor of New Jersey. At that time both had shared the dream of a future for the British Empire. But when Benjamin Franklin lost his post as deputy postmaster in the context of the Hutchinson affair, he asked William in vain to resign from his position as royal governor. In 1775 he tried to convince his son to join the American independence movement. When William refused, Franklin broke off contact with him. William was arrested in June 1776 and taken to Connecticut as a prisoner . But his father was unmoved and did not allow himself to be changed by an urgent appeal from William's wife. Even when William tried to resolve the conflict years later, Benjamin Franklin was tough. In July 1785 they met again in the English port city of Southampton . The conversation - which everyone involved kept silent about - ended irreconcilably. From that day on, Benjamin Franklin would no longer communicate with his son.

Declaration of Independence and Pennsylvania Constitution

To replace the British postal system in the colonies, Franklin had been appointed Postmaster General in July 1775 . For his services he received a sum of 1000 pounds a year, which he donated, however, to the care of wounded soldiers. On August 23, 1775, the proclamation of King George III appeared. that all American colonies would join in a rebellion. In October of the same year and again in March 1776, Franklin was instructed by Congress, along with other delegates, to take two inspection trips to get an idea of the state of the Continental Army . During his meeting in 1775 with George Washington at his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts , the general was just successfully besieging the British who had moved into Boston. But the financial problems of the ongoing war, a lack of recruits and a lack of supplies worried Washington very much. So Franklin worked out a detailed plan for supplying and training the soldiers - just as he had done earlier with the Pennsylvania Citizens' Militia. While the trip to Cambridge in the autumn was easy to manage, his posting to Canada in March 1776 brought Franklin, now seventy years old, to the limit of his capabilities. This went so far that he sent farewell letters to his friends while he was still on the trip, believing that he would not be able to survive the exertion.

Upon his return to Philadelphia, Franklin was elected to a committee that drafted the American Declaration of Independence . Still suffering from health problems, his role was initially limited to going through Thomas Jefferson's designs and developing suggestions for improvement. His amendments have been handed in the document that Jefferson (Engl. As a "rough draft" rough draft ) designated and which now houses the Library of Congress is kept. Probably the most important of his changes was as small as significant: In Jefferson's formulation " We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable " Franklin deleted the words "holy and indisputable" and replaced them with it "Of course" (English self-evident ).

After the separation from Great Britain was complete, the individual states set about drafting constitutions. For Pennsylvania, Franklin was unanimously elected president of the body that would shape the new constitution. At a time when the English mixed constitution with its balance between crown, upper house and lower house was considered the ideal, the Pennsylvania Constitution only provided for a unicameral system . This makes it the most democratic of all draft constitution of that time. In France in particular, the idea was received with great acclaim and implemented years later in the French Revolution .

Diplomat: Paris 1776–1785

Personification of America: Franklin enthusiasm in Paris

Given their tense military situation, it was crucial for the Americans to seek support from other European powers. Therefore, the Continental Congress decided in 1776 to send a delegation to Paris. France, with its centuries-long history of wars against England, was all the more suitable as the French had lost large parts of their overseas possessions to Great Britain in the Seven Years' War . The delegation consisted of Benjamin Franklin, the merchant Silas Deane and Arthur Lee (1740–1792) from Virginia . Their goal was to procure weapons and ammunition for the Continental Army and forge an alliance with France.

On his arrival in Paris, Franklin was enthusiastically received. This enthusiasm was no coincidence: in 1751 the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon read Franklin's work Experiments and Observations on Electricity and suggested a French translation. When it went to press a year later, Franklin received a personal congratulatory letter from the French king. In the years that followed he received a growing number of letters from his French admirers. Among them was the physician and botanist Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg (1709–1799), who translated many of Franklin's essays and works into French, including the minutes of the House of Commons meeting in which Franklin had commented on the stamp law. This font alone was printed and distributed in five different editions. Just a few weeks after his arrival, Franklin's The Way to Wealth was published under the title La Science du Bonhomme Richard and experienced four new editions within a very short time. Such was his fame in France that the streets of Paris were lined with people when Franklin got there in December 1776.

"[Franklin] is in great demand," noted one diary writer, "and not just from his learned colleagues, but from anyone who can gain access to him." Wherever he went in his carriage, groups of people formed who cheered him up and wanted to take a look at him. The ladies of the Paris salons imitated Franklin's brown mink hat by giving their wigs the shape of a fur hat and thus wearing their hair “à la Franklin”. His discovery of the lightning rod and the designs by Jacques Barbeu-Dubourg based on it led to a fashion craze . An observer in the French capital wrote that it was also fashionable for a Franklin engraving to hang over the mantelpiece in every household. His face appeared everywhere - on snuff boxes, clocks, pocket knives, vases, plates, and candy boxes. Some French even tried to co-opt Franklin as one of their own by pointing out that the family name "Franquelin" was common in Picardy . At the same time, a series of portraits, busts and medallions with his image was created. Jean-Antoine Houdon and Jean-Jacques Caffieri designed busts, Jean-Baptiste Greuze and JF de L'Hospital portrayed him and Joseph-Siffred Duplessis (1725–1802) created a dozen oil paintings, which were used in a large number of prints.

1784 were u. a. Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier and Franklin member of a commission set up by the Académie française to examine what is known as animal magnetism ( mesmerism ). She declared mesmerism ineffective. He became friends with the Lavoisier family. By Marie Lavoisier also a portrait of Benjamin Franklin from the years 1787/88 to originate; it was created by her based on a template by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802). He was a member of the Masonic Lodge Les Neuf Sœurs, founded in 1776 .

From the point of view of French philosophers , according to Gordon S. Wood, America possessed precisely those qualities which France lacked: natural simplicity, social equality, religious freedom and a rural enlightenment . Thus the Enlightenment created an ideal image of America, which they used as a weapon against the aristocratic corruption and the material luxury of the ancien régime . Franklin, with his simple demeanor and the backwoods-looking mink cap on his head, became the symbol of this ideal.

Alliance with France

Just a few days after Franklin's arrival in Paris, the first meeting of the American ambassadors took place with the French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes . The aim of the Americans was to enter into an alliance with France as quickly as possible. But Vergennes responded wait and see. The Continental Army had been inferior to regular British troops since the beginning of the war. Apart from the poor level of training, the soldiers not only lacked clothing and food, but above all weapons and ammunition. From the French point of view, it was therefore by no means foreseeable where the adventure of entering the war would lead. When Vergennes only nodded noncommittally at the explanations of the three ambassadors, Franklin promised to send him a memorandum .

In this memorandum he struck a fine balance between promises and threats. Together, said Franklin, France, Spain (which was bound to France by the Bourbon House Treaty ) and America were so strong that the British would forfeit their valuable possessions in the West Indies in a war. Their economic - and thus also political - decline is inevitable for the British in such a situation. If French aid fails to materialize, however, this could ultimately mean for the Americans to be forced into a peace with Great Britain. Franklin urged the time to make a decision. Any further delay could result in disaster.

But Vergennes was not impressed. He rejected the American request for an alliance at this time, as well as the sending of French liners . For the next few months he kept Franklin at bay and waited to see how the war developed. At the same time the French granted the Americans a secret loan and opened their ports to American merchant ships.

The turning point came a year later. Late in the morning of December 4, 1777, a messenger rode into the courtyard of Franklin's French host at Passy near Paris. He conveyed the message to him that the British General Burgoyne had to surrender with all his troops after the Battle of Saratoga and that the Americans had won a decisive victory. This changed the situation fundamentally. In December France formally recognized the independence of the United States, and on January 28 the French government pledged financial support of 6 million livres annually to the Americans . To sign the formal friendship and trade treaty between France and the United States on February 6, 1778, Franklin demonstratively wore the brown velvet suit that he had worn when he was humiliated before the British Privy Council in January 1774. And on March 20, the King of France received Deane, Lee and Franklin as the first official representatives of the United States of America.

Bon vivant

In April 1778, John Adams came to Paris to replace Silas Deane as the United States' diplomatic representative. Adams and Franklin had known each other from earlier days, but were very different in their lifestyle and characters. Adams was 42 years old when he arrived in Paris, thirty years younger than Franklin. Rather stiff in his behavior and in his personal morals, he looked with a certain envy of Franklin, who seemed to have adapted completely to life in Parisian society. Adams complained in a letter to a friend that Franklin enjoyed "a monopoly of reputation" in France. According to Adams in a diary note, Franklin's life in Paris was marked by a constant addiction to pleasure. He doesn't get up until late in the morning, then meets with friends, has fun in the afternoon and is invited to dinner every day, from which he doesn't come back until between nine in the evening and midnight.

Adams was particularly shocked by Franklin's dealings with women in Paris society. Franklin first flirted with Anne-Louise de Harancourt Brillon de Jouy, the wife of a French nobleman who lived on an estate not far from Franklin's host in Passy, and later with Anne-Catherine de Ligniville Helvétius , a salonnière known as “Madame Helvétius ". Franklin, as John Adams noted, was in his seventies “neither lost his love of beauty nor his taste for it”. Nineteenth-century commentators, in particular, interpreted Franklin's romantic, flirtatious relationships with women negatively, portraying him as an immoral philanderer. More recent research, however, shows that Franklin's relationships with women were not “affairs”, but rather platonic relationships in which Franklin mostly played the role of the older and therefore more experienced mentor. In this way, Franklin, who spent many years away from his own family, built up a new and more perfect substitute family each time, which was reflected, among other things, in the fact that many of his - mostly younger - correspondents called him “mon cher papa” or “father “Titled.

The peace of Paris

With the intervention of the French, the tide turned in the War of Independence . After the British defeat in the Battle of Yorktown , General Cornwallis realized the hopelessness of the situation and in October 1781 agreed to the complete surrender of his troops. Thereupon the British House of Commons voted on February 27, 1782 for a cessation of the fighting. The peace agreement was within reach.

On April 15, the British negotiator Richard Oswald contacted Franklin and proposed a separate peace between Great Britain and the United States. But at first Franklin hesitated. He wrote, "I let him know that America would only negotiate in conjunction with France". Since Franklin wanted to avoid at all costs that Great Britain and France would come to a compromise without the participation of the Americans, he finally accepted Oswald's offer and began secret peace negotiations with the British. On July 10, 1782, he handed Oswald a letter in which he stipulated the terms of peace. Britain should recognize the United States as an independent nation and withdraw all its troops from America. At the same time, the British should pay reparations for the destruction in America, sign a free trade agreement and cede Canada to the United States. Franklin did not reveal his actions to either the American Continental Congress or the French Foreign Minister Vergennes.

In October 1782 Franklin had in his hands Britain's written answer to his peace proposal. Canada, the British replied, was to remain in the British Empire, but the British went on Franklin's condition that the United States be recognized. Finally, on the morning of November 30, 1782, the American negotiators, including Franklin, John Jay , John Adams and Henry Laurens , met to sign the contract with the British negotiator at the Paris Grand Hotel Muscovite. The contract contained a clause according to which it would only become legally binding if France had also agreed. But that didn't change the fact that Franklin had negotiated with the British behind the back of the French. On December 17, Franklin sent the French Foreign Minister Vergennes the text of the treaty and a letter of apology. A week later, the two met for a personal meeting in Versailles . Vergennes stated coolly and at the same time in a friendly manner that the French king was not pleased with the sudden conclusion of the treaty, and that the actions of the Americans had not been "particularly polite". At the same time he assured Franklin that the French would remain on friendly terms with the Americans. With this success in bringing about the peace of Paris , according to the American historian Gordon S. Wood, Franklin was involved in the creation of all three great documents of the war: the declaration of independence, the friendship treaty with France and finally the peace treaty with Great Britain.

Last Years: Philadelphia 1785-1790

Back home

After Franklin had been replaced as the diplomatic representative of the United States in France by Thomas Jefferson in the spring of 1785 , he returned to Philadelphia and was greeted there with gun salutes and church bells. His reputation had not suffered from the reports from John Adams and Arthur Lee . Plagued by serious, painful illnesses, he spent time with family and socialized with old friends. So he met with the four surviving members of his 1736 Volunteer Fire Brigade and made his home available to the American Philosophical Society for some of their meetings. He had his house enlarged so that there was space for his extensive private library. When it turned out during the construction work that a lightning rod he had installed had saved his house from disaster while he was away in France, Franklin proudly wrote: "After all, the invention was useful for the inventor."

President of Pennsylvania

The revolution had done with one blow many of the problems in Pennsylvania that Franklin had been so closely involved in early in his political career. In 1776, the Penn family, who owned it, had lost all privileges. At the same time, all taxable residents of Pennsylvania were given the right to vote. The members of the unicameral parliament favored by Franklin had to take an oath after their election in which they undertook to represent the interests of the people. The political landscape of Pennsylvania remained divided. Representatives of the artisans and peasants (called "constitutionalists") faced the representatives of the wealthy citizens (called "republicans").

When Franklin returned, both groups were campaigning. Hoping Franklin would play a reconciling role, both sides nominated him to the Executive Council . This consisted of twelve representatives and exercised the power of government instead of a governor. After his election to the Executive Council , the House of Representatives named Franklin President of Pennsylvania.

Franklin held this office two more times in 1786 and 1787. He admitted to his sister: "This general and unlimited trust of the whole people flatters my vanity much more than a title of nobility."

The Constitutional Convention of 1787

With the ratification of the articles of confederation in 1781, the thirteen founding states constituted themselves as a loose union of sovereign individual states. Due to the conflicting interests of the individual states, this confederation was repeatedly unable to act. Time and again , the Continental Congress was unable to settle outstanding payments and a necessary quorum of 9 out of 13 votes hampered decision-making in votes. In addition, economic development was hampered by protective tariffs in the individual states. In order to remedy these abuses, a constitutional convention was convened in Philadelphia in May 1787. This should review the political organization of the United States and renegotiate if necessary.

The Philadelphia Convention met from May 25 to September 17, 1787. At 81 years old, Franklin, a delegate from Pennsylvania, was the oldest member of the convention. To relieve his pain, he was carried in a litter to the meetings. Since he found it difficult to stand, he wrote down his speeches and had them read by another delegate in the meeting. He received smaller groups of delegates at his home on Market Street during breaks in consultation.

As for his political proposals, these were taken note of with great respect, but mostly closed in silence. This applied to his idea of a unicameral system as well as to his idea that incumbents should not receive a salary for their work. His proposal to set up a multi-member government council instead of a president was also rejected, as was his suggestion to pay a priest to initiate the meetings of the constitutional convention with a common prayer.

On one central issue, however, Franklin's influence had a decisive effect. The delegates were faced with the question of whether the future Congress should be filled in proportion to the number of inhabitants in the individual member states, or whether the member states should send an equal number of delegates. While the first model favored the populous states, the second model favored the smaller states. As the congress participants became more and more divided over this question, Franklin - following a compromise proposal by Roger Sherman from Connecticut - worked out a solution that was eventually incorporated into the constitution . In the House of Representatives , each state would be represented in proportion to its population , and each state should send two members to the Senate . Franklin was not the originator of the idea, but his prestige pre-eminence ultimately ensured that consensus could be found on this crucial issue.

At the end of the constitutional convention, Franklin turned once more to the delegates. He emphasized that in the course of his long life he had already had to revise many opinions and that no one knew the pure truth. Even if the present constitution has flaws, it can never be avoided. He was amazed at how close the final document was to perfection. “Therefore,” he continued, “I approve [the adoption] of this constitution. Because I don't expect anything better and because I'm not sure that it is not the best. "

Fight against slavery

In the last year of his life, Franklin campaigned for the abolition of slavery . By then he had fundamentally changed his attitude towards slavery. During his time as a publisher in Philadelphia, he still had advertisements printed for the sale of slaves or for the search for runaway slaves and also kept his own slaves in his household. But as early as 1729 he had printed one of the first publications against slavery in the colonies, and his wife Deborah enrolled her house slaves in a school for blacks in Philadelphia. His Observations on the Increase of Mankind , published in 1751, shows that at that time Franklin was still largely condemning slavery out of economic considerations. In the 1770s he sympathized with the anti-slavery opponent Anthony Benezet , but admitted that an immediate ban on the importation of slaves would only come “with time”.

Franklin's anti-slavery commitment culminated in his appointment as president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, founded in 1787 . In a manner typical for him, he gave the society detailed statutes “for the improvement of the living conditions of free blacks”. Finally, on behalf of society, he sent a petition to Congress calling for the freedom of citizens of the United States to be guaranteed regardless of their skin color. But his efforts were unsuccessful. Led by Mr James Jackson from Georgia , the Congress dismissed the petition, stating that slavery legitimized by the Bible and without the slaves could not be overcome on the plantations of the hard work.

In response to Jackson's speech to Congress, Franklin wrote the fictional speech by a certain Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim, a member of the Dīwān of Algiers , which he sent to the Federal Gazette under the pseudonym "Historicus" . In this text, which was based on Franklin's Edict from the King of Prussia , an Ottoman scribe attacked a petition calling for the end of the enslavement of European Christians. "Who will work our land in this hot climate if we forbid enslaving their people [the Christians]?" Franklin asked the clerk. Franklin's satire ends with the comment that the Diwan - analogous to the American Congress - rejected the petition with the remark that it was in the interest of the state to maintain the practice of slavery.

Sickness and death

In April 1790, Franklin's health deteriorated. He suffered from pleurisy, high fever, and severe pain in his lungs. When his daughter Sally wished he would soon recover and live for many more years, Franklin replied weakly: "I hope not."

On the evening of April 17, 1790, three months after his 84th birthday, Franklin died with his family. Four days later he was buried next to his wife, Deborah, with great sympathy from the Philadelphia population. According to his last will, a simple marble slab with the words "Benjamin and Deborah Franklin 1790" covers the grave.

In 1728, at the age of twenty-two, Franklin had written the following epitaph, which was initially only in circulation in various manuscripts until it was published in An Astronomical Diary in 1770 ; Or Almanack, printed for the Year of Our Lord Christ 1771, Calculated for the Meridian of Boston, New England :

- "The body of Benjamin Franklin, printer,

- Like the cover of an old book

- Its contents torn out and robbed of the title like the gilding,

- Lies here, food for worms;

- But the work should not be lost

- But it will, as he believed, all over again

- Appear in a new, nicer edition,

- Corrected and supplemented by its Creator.

- He was born on January 6, 1706 and died on 17th. "

Franklin and the game of chess

Franklin played a major role in popularizing the game of chess in the United States. His essay The morals of chess from 1786, which was also reprinted in the first chess book Chess made easy from 1802 printed in the USA , is considered the first American contribution to chess literature . In 1999 Franklin was inducted into the US Chess Hall of Fame .

When exactly he learned the game is not known. In his autobiography he mentions that in 1733 he often played chess with a friend. In order not to be distracted too much from his other studies, he agreed with his opponent that the winner of a game could give the loser a learning task and that this would improve the education of both players. Franklin has been shown to own several chess books and was familiar with the work of François-André Danican Philidor . Before leaving for England in 1757, he wrote to his wife asking him to send some of these books to him. During his stay in London, he was considered a good player there, which in 1774 gave him an advantage by being able to use invitations to a game of chess with Lord Howe's sister for informal negotiations with him. In Paris, Franklin frequented the Café de la Régence and very likely met Philidor too. In 1780 he met William Jones , known as an enthusiastic chess player , there. In addition, Franklin played - with an unknown result - against the chess Turk and gave his inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen a letter of recommendation for Hans Moritz von Brühl . Upon his return to the United States, Franklin's chess activities ended. Apparently he couldn't find any more suitable playing partners and turned to the card game. Since no games have been received from him, one can only speculate about his skill level.

reception

In the first decades after Franklin's death, former Franklin critics expressed themselves mildly about his person. In an eulogy at the funeral, William Smith , First Chancellor of the University of Pennsylvania, highlighted Franklin's philanthropic and academic achievements. And even John Adams , who had sharply criticized Franklin during his lifetime, came to a much more balanced judgment in retrospect. Adams highlighted the great achievements of Franklin in the scientific and literary field and justified his earlier criticism by pointing out that Franklin's greatness almost challenged Franklin to portray his negative qualities.

Franklin's reputation rose even further after his grandson William Temple Franklin (1760–1823) published an edition of his writings in 1817. The literary critic Lord Jeffrey praised Franklin for his "simple joke" and praised him as one of the great exponents of rationalism .

Supporters of romance as John Keats came in the first half of the 19th century naturally to a different verdict. For example, Keats wrote in a letter to his brother that Franklin was "full of pathetic and thrifty rules of life" and "not a great man."

With the dawn of the Gilded Age , an economic boom in the United States, Franklin was seen in a far more positive light as a model of social climber. Thomas Mellon , founder of the Bank of New York Mellon , had a Franklin statue erected in front of his bank's headquarters and said Franklin's example inspired him to leave his parents' farm near Pittsburgh and pursue a career as a businessman. Andrew Carnegie said he was inspired by Franklin to set up public libraries. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner wrote in 1887 that Franklin's life was the story of American common sense in its purest form.

The mood changed again in the first half of the 20th century. The sociologist Max Weber used Franklin time and again in his work The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism as a negative example of an attitude that is solely aimed at increasing one's own financial prosperity. The English writer DH Lawrence rejected Franklin because of his unromantic and bourgeois attitude and stated in his Studies in Classic American Literature in 1923 simply: "I don't like him". In his criticism, he equated Franklin with his character Poor Richard , with whose sayings he associated bad childhood memories. Lawrence converted Franklin's own maxims to suit his own taste. From “Be always employed in something useful” he made: “Serve the Holy Ghost; never serve mankind "and" Wrong none by doing injuries "transformed Lawrence into" The only justice is to follow the sincere intuition of the soul, angry or gentle. "

In the Great Depression , Franklin's reputation rose sharply again - values such as frugality and public spirit were again very popular . In his book The Puritan Mind , the philosopher Herbert Schneider pointed out that previous attacks were directed primarily at the Poor Richard and not so much at Franklin himself, who had not directed his life towards his own wealth. Carl Van Doren (1885–1950), Schneider's colleague at Columbia University, published a highly regarded Franklin biography in 1938, for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography a year later and which is still one of the standard works on Franklin today. And the science historian I. Bernard Cohen began his university career with an investigation in which he placed Franklin on a par with Isaac Newton in terms of his scientific achievements .