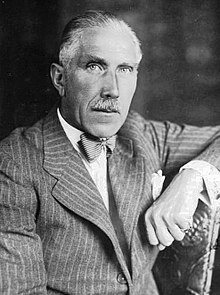

İsmet İnönü

Mustafa İsmet Pascha , from 1934 İsmet İnönü (born September 24, 1884 in Izmir , † December 25, 1973 in Ankara ), was a Turkish politician of the Kemalist Republican People's Party (CHP) and companion of the state's founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk . He was the first Prime Minister of the Republic of Turkey from 1923 to 1937 with a three-and-a-half-month break under Ataturk and then from 1938 to 1950 the second President of the Republic of Turkey. From 1961 to 1965 he was prime minister again.

Inönü himself had opened the way for a multi-party system from 1943 and subsequently lost the presidency. For more than half a century, both in government responsibility and as opposition leader, he had a major influence on Turkish foreign and domestic policy, especially since Ataturk had left him with the practical aspects of domestic and foreign policy at an early stage.

origin

Mustafa İsmet was born in 1884 as the second son of the Hajji Reşit Efendi and Cevriye Temelli Hanım couple . His father came from Malatya and his father came from the well-known Kürümoğulları family from Bitlis , who were Kurdish . İsmet İnönü's mother came from the city of Razgrad in Bulgaria and moved with her family to İstanbul in the 1870s. They married there in 1880. After the birth of their eldest son Ahmet Mithat, Mustafa was born, then Hasan Rıza, Hayri and Semiha. Mustafa Ismet's father was transferred to Sivas as a magistrate , where Mustafa attended school.

Military career under the Ottomans

This was followed by a cadet school from 1892 to 1895, followed by a civil school until 1897. In 1897 he went to Istanbul , where he attended the artillery academy until 1903 and then the military academy of the Ottoman army until 1906 .

During his staff training in Istanbul he met Mustafa Kemal (later Ataturk) know and they became friends. In 1906 he became a captain in the general staff . From there he went to Edirne , where he gained his first negotiating experience after an incident on the Bulgarian border. Because of overly open political discussions, he received two warnings. Mustafa İsmet joined an opposition group. In 1908/09 he did not take part in the uprising of the Young Turks because he was of the opinion that officers were not entitled to do so. When this opinion was not accepted, he left the Committee on Unity and Progress .

Before the First World War he was stationed in Yemen in 1910 , where he contracted a malaria infection that damaged his hearing. In negotiations with the rebels under Imam Yahya, he earned considerable merit. In 1912 he was promoted to major .

In 1913 he took over the leadership of the first section of the General Staff in Çatalca near Istanbul. During this time he traveled to Austria, Germany, France and Switzerland. In the same year he was a military advisor in the negotiations on the Treaty of Constantinople , which ended the Second Balkan War .

After the outbreak of World War I, he was promoted to colonel in December 1914 and placed under the German General Liman von Sanders . During this time he had long conversations with Ataturk. In 1915 he worked under Enver Pascha . During the Battle of Gallipoli , he headed the Operations Department at the Turkish Grand Headquarters. As an army commander he was deployed in Syria (against the Western Allies). In 1915 he was Chief of the General Staff on the Caucasus Front (against Russia ) and in 1917 Commanding General of the III. Army Corps in Palestine . He was also stationed with the Second Army in Diyarbakır . İsmet married Mevhibe (born 1897; died on February 7, 1992 in Ankara) in 1916, for which he stayed for ten days in Istanbul while the Second Army was posted to the southeast. İsmet and Mevhibe İnönü had three children, their son Erdal , born in 1926, became Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey in 1995.

When the commanding general of the Second Army died in the battle on the Russian front (August 6–7, 1916), Mustafa İsmet took his place. The later Ataturk worked there for the first time with the later Inönü. The latter directed the orderly withdrawal of the army from Syria.

After the defeat of the Central Powers , the Ottoman Empire lost its remaining territories outside Anatolia and Thrace as a result of the Peace Treaty of Sèvres . In addition, the area of what would later become Turkey was to be largely fragmented. İsmet received various posts in Istanbul after the Mudros armistice of October 30, 1918, including that of an undersecretary in the Ministry of War.

Military-political career under Ataturk

In the Turkish War of Liberation , which Mustafa Kemal Pascha waged from 1919 to 1923 against the occupying powers of the Triple Entente , i.e. against Italian, French and British occupation zones in Anatolia and the Aegean Sea, but then also against the plan of Greater Armenia in the east and Greater Greece in the West, İnönü was sentenced to death in absentia by the military tribunal of the Istanbul Sultan's government on June 6, 1920 . He had supplied Ataturk with messages and discarded weapons from the Ottoman army. When Ataturk formed his counter-government in 1920, Mustafa İsmet, after some hesitation, took his side because he was initially extremely pessimistic. In January 1920 he also went to Ankara. On March 18, 1920, Istanbul was occupied by Allied forces. İsmet left the capital for Ankara the next day. On April 9, 1920, he became a representative of the army in the Grand National Assembly in Ankara. He was commissioned to build a regular army after he had convinced Ataturk that a continuation of the fight with militias had little prospect.

On October 25, 1920 İnönü was given the supreme command of the Greek-Turkish or Western Front by the National Assembly . In the two battles of İnönü in January and March / April 1921, his troops decisively triumphed against the Greek army, which had to evacuate Anatolia. After the capture of Smyrna (today Izmir), which until then had a large Greek community, on September 9, 1922 the war ended. In 1934, Mustafa İsmet took the surname İnönü in memory of the victories of İnönü according to the Turkish Family Name Act .

In 1922 he was appointed Foreign Minister (he spoke German, English and French). İsmet İnönü took part in the armistice negotiations in Mudanya on October 11, 1922 as a delegation leader. Ataturk appointed him Foreign Minister on October 26, 1922 and from November 21, 1922 to July 24, 1923 he led the delegation in the negotiations on the Treaty of Lausanne , after Ataturk had appointed him head of the delegation on November 2 of the previous year. Ataturk and İsmet prepared the amendments to the 1921 Constitution, which enabled the proclamation of the Republic on October 29, 1923, of which Ataturk became the first president.

Inönü held the office of prime minister from 1923 to November 20, 1924 - İsmet resigned "for health reasons" - but was reappointed on March 3, 1925 to fight the uprising of Sheikh Said in eastern Turkey. İsmet had been replaced by Ali Fethi Bey (Okyar) in November 1924 because a strong group had developed within the CHP that was Kemalist-oriented but turned against authoritarianism and centralism. She eventually founded the Progressive Republican Party (Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası). The popularity of this group was just as strong in the traditionalist East as in Izmir and Istanbul. To ease tensions, İsmet was temporarily replaced by Ali Fethi Bey, who was the head of the party's liberal wing. The ban on the Kurdish language, the abolition of the overarching caliphate, Turkish nationalism and the deportation of the insubordinate led to the uprising of the Kurds, which in turn strengthened Kemalist centralism. Already on March 2, 1925, İsmet got his office back. The TCF was disbanded, many banned newspapers were received, and the uprising quickly collapsed.

On November 3, 1928, the Latin alphabet was introduced and the Arabic script fell out of use. Inönü himself never wrote in Arabic again, and he also made sure that this script was not used in his surroundings, not even by Ataturk. This was considerably more impulsive, so that he had to be reassured by Inönü, whom he referred to as the state pascha, as he might have been ready in 1930 to engage in a military confrontation with Mussolini.

He resigned on September 20, 1937 because of disputes with the Minister of Economics, Celâl Bayar, from office. This put more emphasis on privatization, while Inönü gave priority to the state economy. Inönü also gave up the chairmanship of the party. Ataturk, who withdrew more and more and finally fell ill with cirrhosis of the liver, but who overruled Inönü with his decisions at any time, provoked the rupture that occurred in 1937. From the summer of 1938, Ataturk only lived in the rooms of the Dolmabahce Palace on the Bosporus. After Ataturk's death, Inönü was elected second President of Turkey on November 11, 1938 and was again party leader. As Inonu noted in his diary, they unanimously voted for someone who was out of power, whose views they disagreed with, and whom they feared.

President (1938–50)

Personality cult (1938-46)

On December 3, 1938 İnönü was awarded the title of National Head or National Leader ("Millî Şef") and Unalterable Party Chairman ( Değişmez Genel Başkan ) at the 4th Extraordinary Congress of the Republican People's Party (CHP) . Therefore, the period between November 11, 1938 and May 22, 1950 (according to other information only until 1945) is referred to as the "Period of the National Leader in Turkey" ( Türkiye'de Millî Şef Dönemi ). Furthermore, the late President Ataturk was given the title of "Eternal Head" ( Ebedi Şef ). In May 1946, before the first multi-party elections on July 21, 1946, İnönü dropped both titles.

The acceptance of the title led to the accusation that he had established a personality cult. His political opponents accused him of authoritarian administration, if not tyranny. After 1950 it became the sole focus of criticism of the one-party regime between 1923 and 1945, especially since criticism of Ataturk was taboo. Inonu himself expressed this, and Ataturk had already cast criticism of his policy on Inonu. In addition, Inönü was not prepared to discuss or even justify his decisions during the war years.

Waving between the Allies and the Axis powers

During the Second World War Inönü gave up his plans to liberalize the country. Under his leadership, Turkey maintained its neutrality until shortly before the end of the war, although the war opponents tried to protect the country. Franz von Papen , Ambassador to Ankara since 1939, traveled to the Turkish capital for Berlin in February 1942, while London sent Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen and Paris René Massigli there. Turkey navigated between the alliance systems. On April 23, 1939, the Turkish Foreign Minister Şükrü Saracoğlu Knatchbull-Hugessen announced that Ankara was threatened by the Italian expansion in Albania and the German expansion in the Balkans. Therefore he proposed a British-Soviet-Turkish alliance. In May 1939 Inönü informed the French ambassador Massigli that the best way to stop Germany was an alliance between his country, the Soviet Union and France and Great Britain. Inonu wanted to give Soviet troops appropriate landing permits and asked Paris for trainers for his army. The Ankara Pact of October 1939 came about through mutual aid between Turkey, France and Great Britain, which however had no consequences.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill , inclined to win Turkey for the Allies since late 1942, traveled to Ankara on January 30, 1943 to urge Turkey into an alliance. Churchill negotiated secretly with Inönü in January 1943 in a railroad car in Yenice near Adana . He tried to persuade Inönü to set up bases for the British Air Force so that they could bomb the Romanian oil fields from there, but Inönü delayed a decision. It was only when it became clear that the Axis powers would succumb that Inönü met in public with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Churchill at the Second Cairo Conference from December 4 to 6, 1943 . But Turkey continued to hesitate, so that on February 3, 1944, London abruptly broke off negotiations and a little later withdrew its equipment and instructors. Diplomatic relations reached their lowest point when London sent a protest note to Inonu about the passage of camouflaged German warships.

Since the attack by Italy on Albania on April 7, 1939, Ankara had sought rapprochement with London and Paris, with France ceding the Republic of Hatay with the capital Antakya to Turkey. On June 18, 1941, Inönü added a friendship treaty with the German Reich , with which such a friendship treaty had existed since March 3, 1924 , to the assistance agreements that were now signed with Great Britain and France on October 8, 1939 . The initiative to establish diplomatic relations with Berlin had come from Ankara since 1921, which by no means wanted the friendly relationship with Germany to be valued as if the good relations from the Ottoman era were being continued. Berlin hesitated and did not appoint Rudolf Nadolny , who was the German representative in Ankara, as official ambassador until June 1925. Ankara joined the League of Nations in 1932 . With the beginning of the Second World War, Turkish foreign policy changed. Inönü called on Berlin and von Papen on November 29, 1940 to formulate his thoughts on a non-aggression pact and on the division of the Balkans in the event of Hitler's victory. Berlin agreed to respect the Turkish borders, but the Turkish Foreign Minister Şükrü Saracoğlu demanded an unspecified “Turkish sphere of interest”. Germany was thus faced with the same dilemma as Great Britain, because with this reservation it was not possible to mobilize the Arab world against the enemy. When Berlin was negotiating the free march through the Wehrmacht in the direction of the Suez Canal in May 1941 , the same Foreign Minister called for Iraq to be recognized as part of the aforementioned sphere of interest.

In Berlin, Turkish politics and the Ataturk in particular have been followed with great attention for some time. When he died, a long article about his successor appeared in the Völkischer Beobachter on November 12th . Hitler congratulated Inonu by telegram, while Mussolini failed to do so. In the spring of 1941, almost the entire Balkans were in the hands of Italy and especially Germany. However, while the Turkish General Staff, like large parts of the military leadership, leaned towards Germany, which had been victorious up to then, and continued to pursue Turanist goals reaching far into Central Asia, Inonu remained skeptical. Şükrü Saracoğlu, meanwhile Prime Minister, informed von Papen that he would be very pleased if the German Reich would smash the Soviet Union, it would even be “the Fuehrer's greatest deed”. But this would require the killing of half of the Russian population.

As a precaution, Turkey blew up all bridges over the Mariza river . Von Papen had threatened the bombing and destruction of Istanbul during the negotiations. Nevertheless, Turkey continued to supply raw materials to the Axis powers until an Allied boycott in May 1944 forced the country to stop supplying chrome. At the same time, leading Turanists were arrested and their organizations disbanded. Turkey had diplomatic relations with Germany until August 1944. The number of soldiers grew from 120,000 to over a million, with Turkey only having 17 million inhabitants. Only when the defeat of the Axis Powers became apparent did Ankara break off diplomatic relations with Berlin on August 2, 1944. On February 23, 1945, Turkey declared war on the German Reich (and Japan) without intervening in the fighting.

Cold War

After the war, Inönü leaned on foreign policy to the USA, which increasingly interfered in the politics of Europe and the Mediterranean region. Meanwhile, after the termination of the neutrality treaty in August 1946, relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated. The main point of contention besides the ideological differences remained the straits between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea . In March 1947, the United States took over the British protective role for Greece and Turkey, which also received loans to counter an expansion of power in the course of the Soviet territorial claims in Turkey . Because of these conflicts, Turkey finally gave up its neutrality and joined on February 18, 1952 together with Greece the NATO , which had been founded three years earlier . On October 31, 1959, Ankara approved the deployment of US medium-range missiles. On January 9, 1948, the USA had already started delivering military equipment. On July 14, 1948, 14 communists were convicted in a show trial. Turkey joined UNESCO at the end of the year.

Democratization (from 1943), religious groups, multi-party system (1946–1950)

Domestically, İnönü set in motion a cautious democratization. In 1943 he allowed a larger number of independent members of parliament. In a speech on May 19, 1945, he announced the transformation of Turkey into a democracy . On July 12, 1947, he declared the opposition of the Democratic Party to be legitimate and thus the emergence of a multi-party system.

In religious politics, İnönü strengthened secularism on the one hand by further limiting the influence of the clergy on the state, but on the other hand promoted the training of young clergymen. In 1932 the number of institutions called Diyanet within the state body of the same name ( Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı , later Başkanlığı , i.e. Directorate for Religious Affairs), in which the Koran was memorized, had fallen to nine, with a total of 252 students. In 1934-35 their number had risen to nineteen, with 231 boys and 15 girls being taught here. After Ataturk's death, their number rose by leaps and bounds in 1938-39 to 48 institutions, where 1,239 boys and 142 girls learned by heart. On the other hand, the subject of religious instruction disappeared from village schools in 1939, perhaps an expression of a dispute between Diyanet and the Ministry of Education. The state claimed sole control over the dissemination of religious content, but after the madrasas , like Türbe and Tekke , were closed , only a few institutions remained, such as imams and hodschas , who acted on the edge of legality with their teaching. Various networks emerged in which Nurcus (founded by Said Nursî from Kurdistan, 1876–1960) and Süleymancıs stand out. Said Nursi, who wanted to combine Islam and modernity, was arrested in 1934 and 1943, but in 1948 his work was given legality by the Diyanet. His followers ("followers of the light") gained such influence in the 1950s and 60s that the chairman of the Diyanet had to resign after Said Nursi was attacked in a book published by his organization in 1964. His successor was considered close to Nurcus. From 1946 Said Nursi supported the party of Inönü's opponent Adnan Menderes; In his view, the threat to religion from atheistic materialism and Marxism required the cooperation of Muslims and Christians. Behind Süleymancıs was Süleyman Hilmi Tunahan (1888-1959). He was also arrested twice, namely in 1939 and 1944. From 1938 to 1943 he preached as an employee of the religious authority in the smaller mosques of Istanbul, then, after a ban of several years, again from 1950. His organization also managed to influence the Diyanet and other state organizations to win. In 1957 he was suspected of having declared himself a Mahdi , but was acquitted. The Association of Islamic Cultural Centers in Germany goes back to his organization . Fethullah Gülen's movement, which emerged as a local group in İzmir and the surrounding area at the end of the 1960s, plays a special role .

A land reform, which İnönü himself considered to be extremely important, divided the state property among the peasants. But as early as November 1947, the CHP approached the DP, because now it too was calling for privatizations and cutting back on the land distribution law. Fevzi Cakmak and other national conservative to extreme right set DP members founded the Millet Partisi , the nation party - "the later springboard for Alparslan Türkeş ., Decades of leaders of the ultra-nationalists" in 1949 called Inonu, probably to attract voters from the conservative spectrum, the theology professor Şemsettin Günaltay as prime minister, who considered the connection between Kemalist form of government and Islam possible. Economic growth averaged 10% from 1946 to 1949, but was subject to strong fluctuations; the inflation rate also grew.

After the election defeat of his CHP on May 14, 1950 Inönü resigned; his party had only won 69 of the 487 seats, although 39.8% of the CHP voters had voted. Adnan Menderes , his main political opponent, whose DP fell 53.4%, nonetheless called Inönü a great hero and legendary rival. The military is said to have been ready for the coup, but Inönü refused.

Opposition leader (until 1960), military coup, again Prime Minister (1961–1965)

İsmet İnönü was the opposition leader for the next ten years, but provided the Democratic Party with his expertise in foreign policy matters. He also pushed for free elections, freedom of the press and the independence of the courts and thus personally opposed the increasingly authoritarian style of government of the election winner. In May 1959 Inönü was hit by a stone thrown from a crowd of DP demonstrators, and a few days later he was met by an aggressive crowd in Istanbul. According to reports from the CHP, it was only thanks to the deployment of soldiers that Inönü's life was saved. CHP delegates and Inönü were also stopped by soldiers on the way to Kayseri, who, however, allegedly saluted and let them pass in view of his merits. Already in 1951 Menderes had 500 halkevler , village centers for the dissemination of Kemalist teachings, closed. In 1954 the DP had the property of the CHP confiscated, and in 1957 a law was supposed to make it difficult for it to form coalitions. Finally, Inönü was banned from speaking in parliament for 12 sessions. After serious unrest at the universities of Istanbul, martial law was declared for the provinces of Istanbul and Ankara.

On May 27, 1960 , the military under Cemal Gürsel carried out a coup and ruled the country until October 15, 1961. Menderes and other politicians were executed. Inönü offered his advice and was first chairman of the constituent assembly and then again prime minister from November 20, 1961 to February 1965 under the military, but nevertheless liberal Gürsel. Inonu, he said, would never allow a non-democratic regiment, he would never take part in such an attempt, on the contrary, he would oppose any attempt. The association treaty with the European Economic Community (EEC) fell during his last term of office .

Inönü's party could not rule alone, so he led three short-lived coalitions. Initially, his CHP ruled with the Adalet Partisi (AP), the justice party. This was followed by a coalition with the New Turkey Party , then with the Republican Peasant People's Party under Osman Bölükbaşı (June 25, 1962 to December 2, 1963). Finally, a coalition of independents followed, which lasted from December 25, 1963 to February 13, 1965. On February 22, 1962 and May 21, 1963 there were coup attempts by members of the army. Inonu played the decisive role in suppressing them.

In 1964, the prime minister narrowly escaped a pistol attack. When his company car didn't start after the attack, İnönü reassured his secretary and the chauffeur: "Don't be in such a hurry, they'll say afterwards that we're scared."

Towards the end of his tenure, Inönü supported the left wing of the CHP under Bülent Ecevit. On October 10, 1965, the AP won the elections and Inönü was again the opposition leader.

Party chairmanship (until 1972) and death

In the last ten years Turkey had developed from an agricultural state to an industrial state in the making. The production of vehicles, beer, radios and textiles increased rapidly. From 1973 onwards, private and state industries did more for the gross national product than agriculture. At the same time, the power base shifted, a shift to which Inönü tried to adapt his concepts. As early as 1965, in view of the growing workforce, he adopted the slogan "center-left", an opening to the social question that Demirel attacked with the formula "center-left is the way to Moscow".

Inönü, who had doubts about the new course, promoted Bülent Ecevit , whom he finally had to give way within the party in 1966. Nevertheless, he retained enormous prestige that many politicians sought advice from him. Ecevit's program of renewal was adopted on April 28, 1967 at the party congress.

On March 12, 1971, the army intervened again. But this time it did not claim leadership of the state, but demanded a non-partisan government. Inönü supported Nihat Erim from the CHP. Ecevit, however, resigned in protest. On October 20, 1972, İnönü resigned as party chairman and became a member of the Senate on November 16.

Only in October 1973 did parliamentary elections take place again , from which the democratic socialists under Bülent Ecevit emerged victorious. At the same time, under Necmettin Erbakan , an Islamist party entered parliament for the first time. However, the coalition between Islamists and socialists only lasted until the Cyprus crisis of 1974. The Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) emerged at another source of ethnic conflict, in Kurdistan . At the same time, the influence of religious groups continued to grow.

Inönü died on December 25, 1973. He was buried in the Anıtkabir mausoleum in Ankara. In 1975 İnönü University in his father's hometown, Malatya, was named after him.

literature

- İsmet İnönü: Hatıralar (= Bilgi yayınları. Özel dizi. Vol. 21, ZDB -ID 2299579-1 ). 2 volumes. Bilgi Yayınevi, Yenişehir - Ankara 1985–1987.

- Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman (= Social, economic and political Studies of the Middle East and Asia. Vol. 62). Brill, Leiden et al. 1998, ISBN 90-04-09919-0 .

Web links

- Literature by and about İsmet İnönü in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about İsmet İnönü in the press kit of the 20th century of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Remarks

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ Burhan Kocadağ: Doğu'da Aşiretler, Kürtler, Aleviler , İkinci Basım, Can Yayınları, ISBN 975-7812-70-6 , p. 209.

- ↑ Şerafettin Turan: İsmet İnönü - Yaşamı, Dönemi ve Kişiliği , TC Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara 2000, ISBN 975-17-2506-2 , p. 1.

- ^ Dietrich Gronau: Mustafa Kemal Ataturk or the birth of the republic , Fischer, 1994, p. 112.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Tukish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 16.

- ↑ Matthes Buhbe: Turkey. Politics and Contemporary History , Springer, 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 21.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 22.

- ↑ Matthes Buhbe: Turkey. Politics and Contemporary History , Springer, 2013, p. 58.

- ↑ Analogous to Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 22.

- ↑ Cemil Koçak: Türkiye'de Millî Şef Dönemi , 2 vol., Istanbul 1996, passim.

- ^ With "Period of the National Leader in Turkey" translated by Matthes Buhbe: Turkey. Politics and Contemporary History , Springer, 2013, p. 254.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, pp. 183, 185.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 4 f.

- ^ Nicole Pope, Hugh Pope: Turkey Unveiled. A History of Modern Turkey , Overlook Press, 2011, p. 78.

- ↑ Donald Cameron Watt: How War Came. The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938-1939 , London 1989, p. 278.

- ↑ Donald Cameron Watt: How War Came. The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938-1939 , London 1989, p. 282.

- ^ Andrew Mango: The Turks Today , New York 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Mogens Pelt: Military Intervention and a Crisis Democracy in Turkey. The Menderes Era and its Demise , Tauris, 2014, p. 39.

- ↑ Stefan Ihrig: Ataturk in the Nazi Imagination , Harvard University Press, 2014, p. 139 f. and p. 142.

- ↑ Stefan Ihrig: Ataturk in the Nazi Imagination , Harvard University Press, 2014, p. 217.

- ↑ Stefan Ihrig: Ataturk in the Nazi Imagination , Harvard University Press, 2014, p. 211.

- ↑ Stefan Ihrig: Ataturk in the Nazi Imagination , Harvard University Press, 2014, p. 217.

- ↑ Andrew Mango: The Turks Today , 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Natalie Clayer: An Imposed or a Negotiated Laiklik? The Administration of the Teaching of Islam in Single-Party Turkey , in: Élise Massicard (coordination): Order and Compromise. Government Practices in Turkey from the Late Ottoman Empire to the Early 21st Century , Brill, Leiden 2015, pp. 97–120.

- ↑ Matthes Buhbe: Turkey. Politics and Contemporary History , Springer, 2013, p. 63.

- ↑ Matthes Buhbe: Turkey. Politics and Contemporary History , Springer, 2013, p. 63 f.

- ^ Mogens Pelt: Military Intervention and a Crisis Democracy in Turkey. The Menderes Era and Its Demise , IBTauris, 2014, pp. 166-171.

- ↑ Metin Heper: İsmet İnönü. The Making of a Turkish Statesman , Brill, Leiden 1998, p. 24.

- ↑ Mustafa İsmet İnönü Der Spiegel, March 4, 1964. Retrieved October 10, 2012

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | İnönü, İsmet |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Inönü, Mustafa İsmet |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | General of the Ottoman Army, President and Prime Minister of Turkey |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 24, 1884 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Izmir , Vilâyet Aydın |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 25, 1973 |

| Place of death | Ankara |