Classifications of musical instruments

Classifications of musical instruments establish relationships between the individual musical instruments based on certain characteristics and allow them to be classified into groups within a fixed structure. In a cultural tradition, they either emerged naturally over a long period of time or were theoretically (“artificially”) developed by an outside observer for a special purpose. The classifications that are only valid within a culture are no less important in the respective context than the classifications with universal claims. The individual types of instruments are assigned to one another according to certain similarities, which mostly relate to several determination criteria. Possible criteria include the type of sound generation, the design of the musical instruments, the material, their symbolic and mythological content or their social function.

The oldest classification of Chinese music probably goes back to the 23rd century BC. And divides the musical instruments according to the material into eight sound categories ( bāyīn ). The ancient Indian music theory, which was recorded in writing around the turn of the ages, still shapes Indian music today . It is divided into idiophones (self- tinklers), membranophones (fur-tongues), string instruments and wind instruments . In the European Middle Ages, the music theorist took largely from the Greek and Roman antiquity known division into percussion instruments (which included string instruments) and wind instruments, distinguishing them together by the sound of the human voice. Al-Farabi evaluated the instruments of medieval Arabic music with different criteria according to their usefulness, with the string instruments, above all to the kink neck lute ʿūd , received the highest status.

A systematic classification began in Europe at the end of the 19th century, when Victor-Charles Mahillon took the Indian system as a starting point in 1880 and formed four main groups according to the type of vibration generation. The Hornbostel-Sachs system , which is most widespread today and was published in 1914, is based on this. The open and universal Hornbostel-Sachs system, which is in principle suitable for all musical instruments, was later supplemented by missing groups. Further classifications emerged in the 20th century; in most cases to refine the system (Francis W. Galpin 1937, Mantle Hood 1971, Jeremy Montagu and John Burton 1971, MIMO Consortium 2011) or in an effort to include the neglected musical and social significance of musical instruments. Hans-Heinz Dräger (1948) was concerned with acoustic aspects and the relationship between players and their instruments, Kurt Reinhard (1960) with their musical possibilities.

Basics

"Any kind of classification is superior to chaos." ( Claude Lévi-Strauss ) The classification is supposed to bring order into things and lead to a better understanding of relationships. It usually follows the hierarchical system of a taxonomy and leads from the general to the particular. At the same time, the Greek τάξις táxis means not only “order” but also “rank”: the objects are evaluated and ranked. An order in which only one positioning is possible for each object is desirable.

In the graphic representation, there is usually an asymmetrical tree-like structure with branches branching downwards. A universal system is open and can be expanded to the sides and downwards, while a system that has only one purpose, such as showing why some instruments are used for certain ceremonial occasions, is self-contained. Most classifications use more than one selection criterion and, as a result, lead to their own conceptual structure ( paradigm ) based on societal or subcultural ideas or the interpretations of an individual researcher.

The description of the musical instruments played in a regional culture with the universally applied, but hierarchical and rigid categories of the Hornbostel-Sachs systematics is a variant of the etic perspective of the outsider, which can lead to misunderstandings and errors because it overlooks the social significance of the instruments . The methodology and purpose of the emic and etic classifications differ. Similarly, in many musical cultures, an initial distinction is made between one's own and other musical instruments. In Japan, for example, gakki denotes a “musical instrument” in general, but it is added whether this musical instrument is uchi (“inside”) or soto (“outside”): categories that are applied to objects and equally to social groups. The uchi instruments are called wagakki (“Japanese musical instruments”), while yogakki refers to the imported “Western musical instruments”. A distinction of culture for a long time growing divisions of musical instruments and ethnomusicologist developed classifications is not to hit consistently. Musicologists like Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva (1980) for Indian musical instruments have tried to develop a new system based on traditional principles.

Development of the European instrument classifications

Antiquity

The oldest musical instruments in the Aegean are known from the early Cycladic culture (around 2800–2000 BC). There were harps in the middle of the 3rd millennium and the first lyre appeared in the Minoan culture of Crete towards the end of the 2nd millennium . The knowledge of these musical instruments is due to marble figures, relief seals, wall and vase paintings . They are first mentioned in writing in the works of Homer , Iliad and Odyssey , in the 7th century BC. Overall, it becomes clear that in ancient Greece string instruments were preferred over wind instruments (originally generally aulos ). The bowl-shaped lyra associated with the cult of Apollon was considered a national symbol. Percussion instruments were at the lower end of the range. Frame drums ( tympanum ), cymbals ( kymbala ) and wooden rattles ( krotala ) were only allowed to be used in the cult of Cybele and Dionysus , from where they later found their way into light entertainment music.

Plato (428 / 427–348 / 347 BC) and Aristotle (384–322) considered the lyre kithara and especially the aulos to be morally questionable and unsuitable for free citizens because the latter wind instrument also belonged to the Dionysus cult. Apart from such assessments, the Greek philosophers paid little attention to the classification of the instruments, rather to that of the music itself. Aristotle declared aulos and kithara to be lifeless objects without a “voice” and called the artificial musical instruments organon apsychon (“soulless tools”) to distinguish it from the human voice, organon psychon . This fundamental distinction was later adopted by Porphyrios (around 233 - around 305), who in turn cited kithara and aulos as examples of inanimate tools.

A Greek idea of far-reaching effects was that every movement must necessarily produce a tone, and consequently the planetary movements should also produce a kind of spherical harmony . Pythagoras (around 570 - after 510 BC) and his successors developed a model from this that combined the relationship of the planets with musical harmonies. Plato transferred the cosmic proportions to the microcosmic scale of man. Spherical music and music made by people should represent and influence moods and emotions in the same numerical proportions. The preoccupation with music was now directed more towards the psychic powers of man instead of the heavenly spheres and became more empirical after Plato . So the Greeks took measurements with the monochord to research the relationship between string pitches and harmonies. This led to the distinction between Claudius Ptolemy (around 100 - before 180 AD) in string instruments, which could not be influenced by the player inadvertently and which were used for measurements (essentially the monochord), compared to other instruments that were used to make music. Nikomachus (late 1st / early 2nd century) continued the Pythagorean harmony theory with the number proportions on the monochord, with the difference that he also transferred the experiments to other musical instruments, i.e. he did not differentiate between theoretical and practical sound tools.

The previous classifications were all quite imprecise. Aristeides Quintilianus (about 3rd century AD) goes into more detail on an instrument classification in the second book of his work Peri musikes (also De musica libri tres , "Music in three books"). Through his first division into wind and string instruments, which he made on the basis of sound generation - strings are connected to the heavenly planetary orbits, wind instruments with the wind that blows over the earth - he can explain the superiority of string instruments. In a second, symmetrical hierarchy, he formulates three levels. The musical instruments therefore have a male, middle (female man, male woman) and female character. “Male” are the lyre and the natural trumpet salpinx , purely “female” the sambuke (possibly a small harp) and the Phrygian aulos with its plaintive soft sound. Relatively male are the Pythian aulos and the lyre kithara , relative female of the ensemble played aulos and kithara "with many strings." The string instruments belong to the “ethereal” and “dry” area of the world. Aristeides rates them, following Plato, higher than the wind instruments of the “windy”, “humid” and “changeable” areas below.

In his work Omnastikon in the 2nd century AD, the Greek rhetorician Julius Pollux divided musical instruments into the two categories of percussion instruments and, in turn, subordinated wind instruments. Percussion instruments ( cruomena ) include both percussion and string instruments, because both are stimulated with a similar hand movement of the player. In doing so, he anticipates a view that was common in Arabic music and in Europe until the late Middle Ages.

The three-category model of the Neo-Platonist Porphyrios (around 233 - around 305) was the starting point for the division of instruments ( divisio instrumentorum ) that prevailed throughout the Middle Ages . In his commentary on the theory of harmony by Claudius Ptolemy ( Eis ta harmoniká Ptolemaíou hypómnēma ) he distinguished between stringed instruments and wind and percussion instruments based on the presence of strings; the latter according to their sound production: blow or strike.

middle Ages

In the sparse and scattered statements about musical instruments in the Middle Ages, the Greek and Arab ideas are largely adopted. In contrast, there are a large number of treatises on music in general, which focus less on contemporary music-making practice than on the past and the religious and philosophical integration of music. The late Roman scholar Boethius (around 480 - around 525) adopted the three-part, not particularly conclusively formulated model from Porphyrios. He hardly names or describes examples of musical instruments, such as the wind instruments tibia and hydraulis and the lyre cithara . He counts these three, together with the monochord, among the music-theoretical tools, according to a later tendency among the Greeks to no longer distinguish them from the practically played instruments. Using the monochord division, Boethius extensively examines the mathematical foundations of music. Accordingly, he only regards the full-fledged musician who has theoretically understood the tone scales and intervals.

Boethius summarizes the doctrine of harmonic proportions known from antiquity . The first category he names the music of the spheres ( musica mundana ), brought about by the movements of the stars and the change of the seasons. The “human” music, the musica humana as the second category, is music that is in harmony with the soul. The musica instrumentalis of musical instruments is the third category, with whom he divides the art of music in total for Boethius. Boethius' music theory, which extended into the late Middle Ages, was not intended for the practicing musician, but was intended to provide a universal model for students interested in theology and philosophy.

With Boethius' younger contemporary Cassiodor (around 490 - around 580), the evaluation of musical instruments has a Christian overtone. The fifth chapter ( De musica ) of his work Institutiones divinarum et saecularium litterarum contains a short list of the musical instruments that he classifies as percussion instruments (metallic-sounding idiophones ), string instruments ( cithara , probably a general term) and wind instruments ( tibia, calami, organa, panduria ) divided. According to his interpretation of the 150th Psalm, these instruments should not only please the ears, but also serve to purify the soul. They were created for the joy and praise of God, although he - following Plato - gives preference to the human voice.

Bishop Isidor of Seville (around 560–636) takes on the well-known three-part division of the instruments and the separation of the instrumental sound ( sonus ) from the sound of the voice ( vox ). With a lot of imagination, he mentions the common instrument names as well as those from Greco-Roman mythology and the Bible. He describes their shape and draws attention to the magical effect of certain musical styles. In terms of percussion instruments, he mentions idiophones ( sistrum , cymbala, acitabula and the handbells tintinnabulum ) and membranophones ( kettle drum tympanum and tubular drum symphonia ) without distinction . For Isidore, the etymology of the names and the mythological inventor of the instruments are decisive. Occasionally he establishes a symbolic meaning of the construction of an instrument. The seven strings of the cythara are said to be related to the spherical harmonies in the same number. Going beyond the traditional divisio instrumentorum , Isodor gives one of the most detailed descriptions of musical instruments of the Middle Ages.

Hucbald (around 840-930) was a monk of the Carolingian era , to whom a music-theoretical work ( De harmonica institutione ) is ascribed. In contrast to Isidore, he uses the term sonus for the sound of musical instruments and the human voice. He invokes Boethius and, like the latter, deals with the monochord and the corresponding canonical instruments of music theory. He considers the order ( ordo ) of musical instruments to be already exhaustively represented by the Greek and Roman authors, so that he only reproduces their classification. In this respect, Hucbald is representative of the medieval clinging to ancient tradition.

Contemporary with Hucbald was the author of an anonymous Byzantine alchemy treatise in Greek , in which he tries to establish a relationship between alchemy and music through similar elements . For this purpose he uses the usual three groups of instruments and mentions the material of the instruments and the number of strings or the number of finger holes. He names the group of wind instruments after their most famous representative, the aulos , and the string instruments accordingly after the kithara . Anonymus subdivided the first group according to the material and the second group according to the number of strings: a plinthion had 32 strings, an achilliakon 21, a psalterium 10, 30 or 40 strings, a lyra 9 and another instrument 3-5 strings. Names known from antiquity appear on the aulos instruments: psalterion, pandurion, salpinx and kornikes are made of copper . The single reed instruments monokalamos are not made of copper . The percussion instruments are first divided into cymbals , copper and glass instruments, then, according to their style of play, into those that are played with the hand or foot. This results in a relatively symmetrical three-level category tree. The references to the Greek tradition are unmistakable, but they are not embedded in the Christian world of faith.

John Affligemensis (or Johannes Cotto) whose origin and dates are unclear, is the first medieval music theorist who in his treatise De musica cum tonario in 1100 makes a distinction based on the sound education, for the Greeks as Organon apsychon and psychon Organon was known . The artificial sounds produce instrumenta artificialia , namely sambuca , fidibus ("with string instruments") and cymbala ( pair of cymbals , in the Middle Ages also bells, glockenspiel), which he counts among the instruments with a definable pitch - in antiquity sonus discretus - and from those with an indeterminable (noisy) pitch - in antiquity sonus continuus or sonus indiscretus - delimited. He also subdivides the instrumenta naturalia , the sounds produced by the human vocal organ. He considers laughter to be a natural sound with an indeterminable pitch.

The division of Johannes Affligemensis into artificial and natural sound creators became the standard model in the 13th century and was widespread until the 16th century. What should be included in detail, however, is viewed quite differently. The Spanish Franciscan Johannes Aegidius von Zamora (around 1240 - around 1320) reinforces their essential difference by describing them as "dead" and "living" instruments. He only counts string instruments among the sound generators with a definable pitch; the cymbala , in addition to the membranophones, also have an indefinite pitch . Aegidius also makes a distinction between instruments that have existed for a long time and those of his time.

Roger Bacon (1214–1294), an English Franciscan , was concerned with musical instruments because they were very often found in the Bible. He takes on the division of Cassiodorus with examples from earlier times and the separation into natural and artificial instruments. The musica instrumentalis produce tones ( sonus ) through the clash of hard objects . He mentions cithara and psalterium as examples . Unlike Boethius, he does not understand the musica humana category in general as the harmony of the soul, but as the human voice ( musica naturalis ), which he divides into four groups according to the style of singing.

With the French music theorist Johannes de Grocheo (around 1255 - around 1320), the criticism of Boethius' previously accepted three-way division of music began. The independent thinker who does not obey tradition distances himself from the speculative theory of the proportions between spherical harmony and man-made music. Nobody has heard such heavenly sounds and angel chants before. At the beginning he discusses the fundamental difficulties in the classification of musical instruments, because when individual criteria are applied, the object as a whole disappears from view. Against the previous classification of instruments according to the type of sound generation, the practical musician Grocheo therefore sets an order in which musical instruments are classified according to their area of use and their social function (in his Paris area). He discusses the instruments not only as components of a music theory, but also as the first to discuss their use in popular music. He assigns the top rank to stringed instruments, especially viella , because by shortening the strings you can directly influence the sound generation. He also names the psalterium, cithara, lyra and the quitarra sarracenica . Grocheo's writing, written around 1280 ( Tractatus de musica , preserved as a parchment manuscript from the 14th / 15th century) contains the most detailed description of performance practice in the 13th century.

Johannes de Muris (around 1300 - around 1360) provides the most detailed classification of the 14th century in several writings on music . He divides musica naturalis into singing voice and musica mundana (heavenly music). The instrumenta artificialis are composed according to their components of chordalia (string instruments), foraminalia (from foramina , "bores", "openings", wind instruments) and vasalia (vessels). He uses some of the names he has taken over from the Greek in error and it is occasionally not clear what type of instrument he is referring to. In addition, Johannes de Muris differentiates the instruments according to their range or their mood. Obviously he means stringed instruments when he sorts according to moods at certain intervals .

Plucked and stringed instruments were widespread in the 14th century, however, no distinction is known to have been made between them. The same applies to the clavichord , a keyboard instrument that already existed around this time and that was classified under the stringed instruments. In the 15th century, the Spanish mathematician and music theorist Bartolomé Ramos de Pareja (around 1440–1522) dealt with the sound tools in his work on music, published in 1482, which he initially differentiates into vox (singing) and sonus (instruments). In the further subdivision into string and wind instruments, he completely disregards the percussion instruments. In accordance with the preference of his time for stringed instruments, he devotes himself to them in detail and divides them into those with strings of the same length and those with strings of different lengths. The monochord described by Ramos had several strings of different lengths.

Paulus Paulirinus de Praga (1413 - after 1471) from Bohemia was one of the first scholars who devoted himself to the mechanical construction of various keyboard instruments (monochord, clavichord with double-choir strings, harpsichord ). Other instrument names mentioned by Paulirinus are sometimes difficult to understand. Since the 10th century, medieval authors occasionally used terms that did not match the late Latin ones. Instruments from folk music are not included in any list. String instruments were preferred throughout the Middle Ages.

Modern times

Whereas instrument classification and music theory were previously on the same line, now they have split in different directions. Since the beginning of modern times , musical instruments have mainly been mentioned in the prefaces of the tablature . Sebastian Virdung (* around 1465) wrote Musica tutscht und pulled out (printed in 1511), the oldest work only about musical instruments.

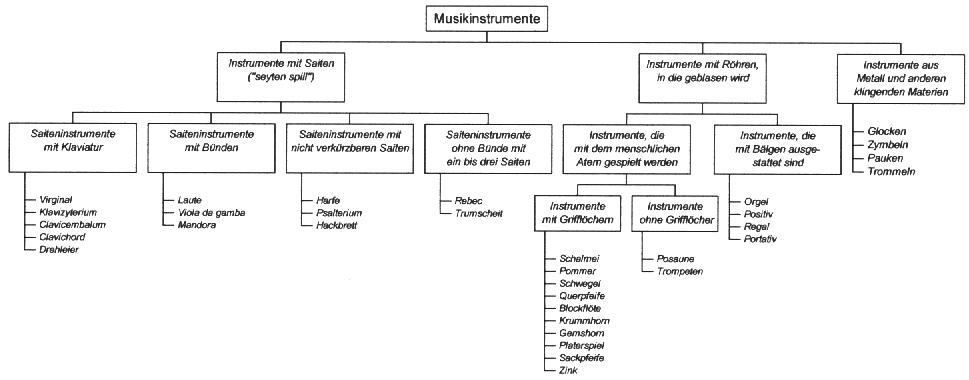

Classification by Sebastian Virdung:

Virdung first describes the musical instruments and then gives practical instructions for some instruments such as the lute, clavichord and flute in question-and-answer form on construction, tuning and playing style. The basic classification of the stringed instruments is based on the presence of strings, the wind instruments on the wind, which stimulates them to sound, and on the material of the third group, the percussion instruments. He differentiates the other subgroups according to the design.

Gioseffo Zarlino (1517–1590) arranged the musical instruments in his work Sopplimenti musicali from 1588 in two parallel systems according to different criteria and thus created the most complex categorization of the 16th century. After differentiating between instrumenti naturali and artficiali , it forms the first order with wind, string and percussion instruments. The next subdivision is based on morphological criteria and the playing style. He asks the wind instruments whether they consist of one or two tubes and then whether they have finger holes or not; Furthermore, whether the instruments have variable pitches ( instromenti mobili ) such as trumpets or fixed pitches ( instromenti stabili ) such as keyboard instruments and flutes with finger holes. By tasti he means buttons and frets . The next level down is about whether the tuning can be changed, as with the lute and viola , or is unchangeable. Tasti instruments are a subgroup of string instruments and are further divided into instromenti mobili and stabili . The instromenti mobili contain a group in which only one hand presses the buttons (the other turns a wheel like the hurdy-gurdy ). The other subgroup needs both hands to play ( harpsichord ). In addition to this highly differentiated classification, he adds a second one in which the instruments are divided into simple and composite and then further differentiated according to their material. The instruments are made of metal ( campana , a bell struck with a hammer ), the drums are composed because they are made of wood and animal skin.

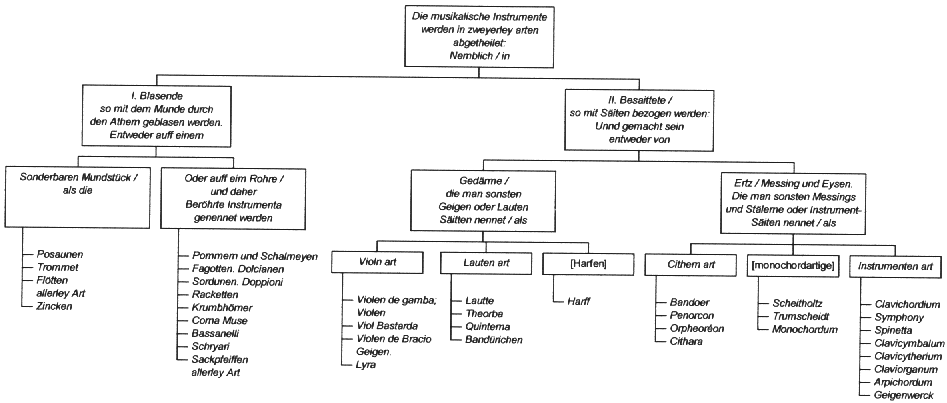

In the 16th century, the peculiarities of the design and the playing practice came more into focus, because the upswing that instrumental music took in the Renaissance made increasing demands on the technical development of instruments. In addition, the number of types of instruments increased significantly in the 16th century, because new instruments were invented and instruments outside of Europe were introduced into music-making practice. Zarlino was probably the first to distinguish between string instruments and keyboard instruments and bowed and plucked strings. In the second volume of Syntagma musicum from 1619, Michael Praetorius (1571–1621) forms “families” within the string and wind instruments according to their shape and playing characteristics: whether an instrument can hold the tone for a long time, whether it has a fixed pitch, its range is sufficient for a composition or whether it can produce additional notes beyond its specified range. The concept of instrument families is still common today.

Classification by Michael Praetorius:

From the point of view of a mathematician who is more interested in acoustic-physical calculations, the Jesuit Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) shares the stringed instruments in his Harmonie universelle: Contenant la théorie et la pratique de la musique from 1636/37 into such and those without a neck. He judges the former according to whether they have frets or not, and the latter according to whether they have a keyboard.

As an aftermath of the teachings of Julius Pollux, who grouped string and percussion instruments in one category in the 2nd century, keyboard instruments were predominantly considered to be percussion instruments in the 18th century, in contrast to the previous century. Like Sébastien de Brossard (1655–1730), various scholars in the 18th century gave string and keyboard instruments a preferred position. The classification in the Dictionnaire de musique, contenant une explication des termes Grecs, Latins, Italy, et François. (Paris 1703) by the musician de Brossard is divided into three parts:

- enchorda or entata , string instruments with several strings: (a) plucked with fingers: guitar, harp, theorbo , lute , (b) bowed: hurdy-gurdy , violin, trumpet , archiviole (bowed instrument with keys), (c) mechanical instruments

- pneumatice or empneusta , wind instruments: (a) naturally blown: serpent , bassoon , oboe , trumpet , flute , (b) artificially blown: bagpipes , organ

- krusta or pulsatilia , percussion instruments: (a) struck with mallets: drum , timpani , (b) struck with mallets : cymbal , psalterium , (c) plucked with plectrum: cister , also spinet , harpsichord , (c) struck with hammer: bells .

Modern universal classifications

From the beginning of the 18th century, the collections of previously unknown exotic musical instruments that explorers brought with them from all over the world grew in Europe. Representing one of the first musicologists who showed interest in it, Guillaume André Villoteau (1759–1839) should be mentioned, who was part of the scientific staff of Napoleon 's Egyptian campaign from 1798–1801 and who subsequently dealt in particular with Egyptian musical instruments. Much in the rapidly growing museum depots was badly labeled and incorrectly assigned. The first classification system designed for universal validity by the Belgian Victor Charles Mahillon (1841–1924) arose from the need to develop a classification criterion for the work in the museum of the Brussels Conservatory . The five-volume catalog of the museum's first curator forms the basis of modern instrument science . The introduction to the first volume, published in 1880, contains Mahillon's classification, intended as an introduction to the catalog.

The classification consists of the basic division into four groups analogous to the ancient Indian system: "Autophone" (self-tinker, an intrinsically elastic solid), "Membranophone" (a two-dimensionally tensioned membrane transmits vibrations to a body), "Chordophone" (a one-dimensionally tensioned string transmits Vibrations, string instruments) and "aerophones" (a column of air in a tube vibrates, wind instruments). The second of a total of four stages is about the type of sound generation. The autophones are differentiated according to striking, plucking or rubbing, the aerophones according to the presence of a reed, a blowing edge, the approach technique and polyphonic wind instruments with a wind chamber ( bagpipe ). The string instruments are bowed, plucked or struck. In the third stage, Mahillon differentiates between the stringed instruments and membranophones, whether they produce tones of a certain or indefinite height, and the wind instruments according to the type of tone generation. Further morphological properties follow in the fourth stage. The levels are designated as branches, sections and subsections , probably with reference to the biological taxonomy of the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné (first published in 1735 in Systema Naturae ). Within the individual groups, a distinction is made between instruments with and without a keyboard or automatic mechanism. The system is structured strictly logically and is based on a few criteria. It is centered on European musical instruments, but offers more options for differentiating percussion instruments than previous European classifications, to which it is nevertheless linked.

Georg Kinsky, who was in charge of the music history museum of the paper manufacturer Wilhelm Heyer in Cologne, made another important contribution to the knowledge of instruments. He published two volumes of his catalog in 1910 and 1912; the third volume on wind instruments that was planned was never published. Kinsky did not classify the instruments according to Mahillon's scheme, but with his great historical expertise mainly according to technical characteristics.

At the turn of the millennium, numerous monographs on the history of musical instruments were published. Among them was a systematic treatise on the Old English musical instruments by the Anglican canon and music historian Francis W. Galpin (1848-1945) from 1910. The appendix contains his first classification scheme, presented in London in 1900, with which he ties in with the four classes of Mahillon. These four classes are followed by further, in the case of string instruments, sixfold subdivisions, divisions, groups, sections, sub-sections and branches up to families (types with different moods). At the second level there is again the distinction between whether the instrument has a keyboard or not or whether it has an automatic playing mechanism. Galpin's classification is too one-sided towards European, technically mature musical instruments and does not take into account non-European instruments; in the case of idiophones ( sonorous substances ) the question of the keyboard was superfluous, because he could not give an example of such a thing. The third stage separates the sonorous substances and the vibrating membranes (membranophones) into rhythmic and tonal . This corresponds to the medieval distinction between instruments with a definite and indefinite pitch. The other two groups are differentiated on the third level according to the usual characteristics of sound production. The system was used to catalog two museums and was later forgotten.

In contrast to Galpin, Curt Sachs (1881–1959) was interested in music ethnology in Berlin indiscriminately in all musical instruments known at the time, as he had listed them in his Reallexicon of musical instruments from 1913 with information on design and etymological information. Together with Erich von Hornbostel (1877–1935) he published the Systematics of Musical Instruments in 1914 . An attempt . This is based on the four groups of Mahillons, which are recognized as logical and transparent, which are supplemented by a large number of sub-categories, which are always based on one characteristic. Their arrangement is formally based on the Dewey Decimal Classification , a hierarchical system developed by the American librarian Melvil Dewey for the classification of library holdings. The system should be suitable for all instruments and for all times. The subdivisions primarily take into account the acoustic characteristics of the tone generation, which, however, must be supplemented by morphological criteria for some instruments. Concessions to the logical structure were necessary because the entire material turned out to be too complex to apply only one characteristic. For example, the inherently smooth transition from cylinder drums to frame drums - both are tubular drums - is defined by the frame height, which in the case of frame drums is arbitrarily limited to the radius of the eardrum. While aerophones are differentiated on the second level according to their tone generation, the shape of the body and the position of the strings are decisive for chordophones. A subgroup of keyboard instruments and instruments with automatic mechanics was initially missing.

There are some disputes that cannot be classified into the Hornbostel-Sachs system or that could belong to several groups at the same time. For example, is the Jew's harp , which in Mahillons system in the car phones is sorted, here in the appropriate category of Idiophone. If the tongue of the jew's harp is perceived as a penetrating tongue , which does not vibrate by blowing, but by plucking it and transmits these vibrations to the air, then the jew's harp can be counted among the free aerophones . Conversely, the reed instruments could be classified as idiophones. Such criticism in individual cases can be exercised in all universality-based systems. André Schaeffner, who designed his own system, criticized the subgroup of Zupf idiophones (12) as a whole. This also includes the lamellophones found in Africa , in which metal tongues are plucked with the fingers, which transmit their vibrations to a sound box or a board. The Zurich ethnomusicologist AE Cherbuliez later formed his own group of "linguaphones" from the jaw harp, lamellophone and other "plucked idiophones".

The Hornbostel-Sachs system of 1914 took into account the instruments known at the time. In 1940, Sachs added the fifth category of electrophones to the system . Sachs introduced the term for very different musical instruments that have to do with electrical or electromagnetic energy regardless of how they are produced. In 1937, Galpin was the first to use the term electrophonic instruments . The electrophone category, which consists of three subgroups, was largely accepted and adopted by other researchers, with the objection that, according to the internal logic of the system, the first subgroup, which contains electric guitars , should not belong because the sound is generated acoustically with them the sound is only amplified and changed electrically. Electrophones in the literal sense include the theremin , which was widespread in the 1920s, and the synthesizers that emerged from it later .

The basis of the Hornbostel-Sachs system is not a theoretical, logical system in which the objects are assigned according to exclusivity criteria in dichotomies (either - or), but is the result of an empirical assessment that asks about functional and structural similarities. As a result, the system is not specialized and neither mandatory nor static. In individual cases it may be possible to structurally assign an instrument to two main groups at the same time. The hierarchical order of the system is not a concept introduced by the authors, but inevitably arises as soon as an order occurs in more than one structural level. The Hornbostel-Sachs system is - like any classification based on manifestations - ahistorical, that is, it is not dependent on historical evaluations. Development processes do not belong to the principle of the system, but the lower levels of structure achieve historical significance as a result. It seems imperative to put the group of idiophones in the first place, but a developmental direction for the positioning of the other three main groups cannot be derived from this.

To this day, the Hornbostel-Sachs system is the most widespread, despite numerous attempts to reform or add to it in parts. Most of the later classifications are just extensions. The French anthropologist and ethnomusicologist André Schaeffner (1895–1980), head of the musical instrument collection at the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, developed a completely different system in 1932 in which he wanted to avoid the imprecise and illogical category of idiophones. Its classification, which is essentially based on ethnographic data, consists of a simple structure with few criteria and only two groups at the top level: (1) the musical instruments with solid, vibrating resonance bodies and (2) musical instruments that contain vibrating air. The solid bodies are divided into (a) those that are not tensioned (idiophones), (b) instruments with elastic parts (lamellophones) and (c) instruments that are dependent on tension (stringed instruments and membranophones). Instruments with vibrating air have the following properties: (a) free air space ( siren , harmonium , accordion ), (b) cavity (clay pot drums, ghatam ) and (c) trachea (actual wind instruments). The next two levels are determined by shape and, in part, by material. Despite its perfect internal logic and clarity, Schaeffner's classification in the shadow of the Hornbostel-Sachs system is little known outside of France.

In 1937 Francis W. Galpin wrote a second classification, this time based on the work of Hornbostel and Sachs, including a fifth category, electrophonic instruments or electric vibrators , which Sachs adopted in his system in 1940. Galpin added the Trautonium , Hammond organ and the Hellertion, invented in 1928, to the fifth category . In contrast to 1910, he now dispensed with the distinction according to the keyboard and thereby made his new system more generally applicable. In the fourth level, the keyboard question appears again along with other criteria. Regardless of some individual problematic assignments, Galpin's classification lacks overall clarity.

Francis W. Galpin had created an extensive private collection of musical instruments, which from 1916 formed the basis of the musical instrument collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston . The trained engineer Nicholas Bessaraboff (1894–1973), originally from Russia, initially only wanted to catalog the inventory of 564 musical instruments - more than half of which came from outside Europe - but expanded his work into a comprehensive manual on the history of European musical instruments, the 1941 appeared under the title Ancient European Musical Instruments . It contains its own classification of musical instruments, which refers to the first classification by Galpin 1910 and divides the five main groups into 1) instruments that are directly excited, 2) instruments that are excited by keys, and 3) automatically moved instruments. Curt Sachs praised the manual in a review in 1942, but criticized the division of the next subgroup that Bessaraboff made according to sound and style of playing, i.e. for idiophones and membranophones, whether they produce an indefinite or specific pitch, for aerophones, whether they are longitudinal or transverse be blown, and for string instruments, whether the strings are plucked, struck or bowed. For Sachs, this was a throwback to the time before his classification. According to this, a string instrument does not change if it is plucked once and bowed another time. He also noticed that drums cannot be clearly classified according to a definite or indefinite pitch. Although Bessaraboff knowledgeably and comprehensively evaluated almost forgotten Russian literature, his only published work was relatively little known.

The Swedish ethnomusicologist Tobias Norlind (1879–1947), director of the Stockholm Music Museum ( Musikhistoriska Museet ) meticulously added many small details to the Hornbostel-Sachs system. Only the first two volumes of his large-scale treatise have appeared. In an article published in 1932 he advocated looking at cultural characteristics such as gaming practice, geographical distribution and, as in biological evolution, origin, in addition to the previous acoustic and morphological criteria. With this he made the beginning for the following efforts, which endeavor to precisely this culture-specific approach.

Norlind's concern was the first to implement Hans Heinz Dräger (1909–1968) in a classification for which he wanted to explore the "world of musical instruments" with a large number of "characteristics", which was "only possible in relation to the type of game" be. The arrangement is presented in the form of a table, with 14 vertical columns for the external identifiers indicated for each type of instrument listed at the right end of the line. The external characteristics include “the substance to be set in vibration, vibration transducers, resonators and vibration exciters.” Dräger's tables were laid out in a much larger framework, but remained (without the help of a computer) limited to the representation of the external characteristics. He saw sound generation as a further characteristic of the categorization; Unison and polyphony; musical agility; Sound duration, dynamic yield, volume; Extent, melody design; Register wealth; Tone color and the person of the player. The tables are confusing and partly dependent on subjective assessments, for example which material or which function should be preferred for sorting.

In 1960 the musicologist Kurt Reinhard published a classification with the limited purpose of using the tonal qualities that Hornbostel and Sachs did not take into account . He had already written the article in 1943 and added it to his habilitation thesis in 1950. Reinhard understood his contribution as a supplement to the Hornbostel-Sachs system, in order to help the concept of "instrument psychology" introduced by Norlind to take effect. He complained that, from a morphological point of view, musical bow and piano are closer together than piano, harmonium and organ , although the former have nothing to do with each other musically, the latter have a lot to do with each other. In the first stage, Reinhard's table contains the distinction between (1) sound instruments (triangle, drum), (2) single-tone instruments and (3) instruments suitable for polyphonic playing, broken down according to geographic regions. Group (2) is divided into (a) the pitch cannot be changed (timpani), (b) can be changed at will (trombone) and (c) can be changed in stages (flute, oboe, jew's harp). The multi-tone instruments (3) are also divided into (a) cannot be changed (xylophone), (b) can be changed at will (violin) and (c) can be changed in stages (bagpipes, guitar). The examples are taken from the "Europe" column. Such a classification is not free from value judgments and in places is ambiguous.

From a starting point that was contrary to all other classifications, Oskár Elschek (* 1931) and Erich Stockmann (1926–2003) approached a typology of folk musical instruments. Both were members of the Study Group on Folk Music Instruments , founded in 1962 by Ernst Emsheimer and Stockmann , which set itself the goal of ethnographic field research on European folk music and collected a large number of musical instruments and sound documents and published documentation on them. Their typology, published in 1969, represents the first methodological attempt to classify from the bottom up. On the basis of Dräger's tables, they start with the individual musical instrument, which they combine with other instruments into types according to their playing style, shape, construction, tonal properties and the manufacturing method. The further they advance towards larger groups, the fewer common characteristics they have. The difference is that with the usual, progressive differentiation at each level, only one criterion is applied, while here the focus is on the instrument in its entirety and social environment. Elschek and Stockmann's method has so far found few supporters; it could also be applied to instruments of classical and other music.

Mantle Hood (1918–2005), a student of Jaap Kunst who specialized in Indonesian gamelan , designed a complex system with five categories in 1971 as an extension to that of Hornbostel and Sachs. At the lowest level, he added further branches according to the type of sound production: Volume, pitch, sound and speed of the tone sequence. With this he designed a graphic, symbol-based system of “organograms” for each individual instrument, with which the characteristics of the construction, the material and the playing style can be represented. An extensive database is required. Hood's system of a “symbolic taxonomy” is considered to be the most innovative extension of the Hornbostel-Sachs system, but inevitably adopts the points criticized there.

In 1971 the two British ethnomusicologists Jeremy Montagu and John Burton published their own classification because they found the numerical classification system of the Hornbostel-Sachs system to be too complicated and because combined instruments (medieval triangle with rattle, Scottish bagpipes with single and double reeds) not let accommodate. They largely differentiate according to the design and add cultural (ethno-organological) and geographical details as well as information about the manufacturer of the instrument. Instead of the decimal classification , in which a maximum of nine sub-categories can be formed, they arrange the sub-groups as required in any number of terms that they borrow from Carl von Linné's biological taxonomy (inconsistently divided into, for example, class, order, subordination, family, genus, species, variety ). This arrangement can be expanded as required and can be filled with different criteria depending on one of the four known main categories. The acceptance remained lower than would correspond to the advantages of the system; possibly because the same takeover of Linnaeus' terms by Mahillon was criticized as early as the beginning of the 20th century and because the groups so designated do not correspond to those of the other categories.

Michael Ramey was able to process the abundance of material to be categorized, which prevented Dräger from completing his work, in 1974 with the help of a computer ( IBM 360/91 from the University of California ). Ramey took the Hornbostel-Sachs system plus the data collected by Mantle Hood plus morphological criteria from Dräger as a basic framework and thus came up with 39 morphological, 15 acoustic and 21 music-making criteria, which he incorporated into a three-stage supplementary system. The practical music-making criteria contain information from the exact playing posture to the social position of the musician.

According to the title of his research work Fundamentals of the Natural System of Musical Instruments from 1975, Herbert Heyde (* 1940) is concerned with a “natural” relationship between musical instruments from the primeval times of history to the present day. He criticizes the previous "artificial" classifications because they paid too little attention to the development of musical instruments and their relationship to one another. Heyde's contribution is intended to provide a framework for understanding the history of musical instruments. In 1929 Curt Sachs assumed similar global relationships between musical instruments ( Spirit and Becoming of Musical Instruments ), but kept his analyzes separate from the functional apparatus of systematics. Heyde uses 14 criteria to describe each instrument's design, playing style and musical characteristics. Four graduated abstraction classes, to which the technical degree of development belongs, bring the musical instruments into an order analogous to biological evolution. For each technical criterion (keyboard, finger holes and keys on wind instruments, pulling the trombone) it is necessary to state whether it is anthropomorphic or technomorphic, in the latter case whether the transmission is mechanical, pneumatic or electrical. Heyde's classification is conclusive because it is based on a characteristic in each level and includes the previous systematics. For each instrument there is a drawing with symbolic elements that have to be translated back.

In this sense, Hans-Peter Reinecke (1975) also campaigned for a deeper understanding of the musical-social-psychological relationships. He contrasted the four classes of instruments (1) trumpet-like, (2) flutes, (3) bells and gongs and (4) string instruments with four emotional stereotypes, whereby he was more interested in the meaning of the phenomena than in their structure.

Tetsuo Sakurai of the National Ethnological Museum in Kyoto published a classification in 1980 and a revised version of the same in 1981. The older system is based on a parallel structure of musical instruments as elements of material culture and spiritual culture. In the first case there is a seven-part breakdown according to the sound source in (a) air, (b) string, (c) reed, (d) solid object, hollow body, (e) membrane and (f) oscillator. The sound generator converts the incoming energy into sound waves. The next lower level is about the design. In the 1981 system, there are three schemes side by side. As before, the first asks in seven groups about the sound source, the second more precisely about its shape and the third about the type of sound produced. The system is based on processing with computers.

The project Musical Instrument Museums Online (MIMO), which was co-financed between 2009 and 2011 by the European Union and European at the big museums, libraries and collections participate pursued within the framework of the EU program eContent Plus the goal of a central access to the to create existing digital materials. The work of Jeremy Montagnu forms the basis for a further expansion of the Hornbostel-Sachs system by several employees on this project. The structure is based on the tried and tested decimal number order, supplemented throughout the area by further differentiations determined according to morphological criteria. The fifth group of electrophones was expanded as far as possible, with a detailed distinction being made according to the method of sound generation on up to five levels. Another important addition in terms of classification is the introduction of a fourth group for the actual wind instruments (42): After the existing flutes (421), wind instruments with a swinging tongue (422) and brass instruments (423), the membranopipes (424) were added. In the case of the membranopipes , which could not be grouped into the existing structure, the toner exciter is a tensioned membrane which, when excited by a stream of air, periodically opens and closes an air passage and thereby sets the air in a downstream tube vibrating. Another group of rare aerophones, for which no generally accepted category has yet been found in the Hornbostel-Sachs systematics, are the sucked trumpets , in which the tones are formed with the lips by sucking in air.

Non-European supraregional classifications

Arab world

An old order of musical instruments in the Arab world arises from the importance that is attached to the instruments by their legends of origin in the folk beliefs that were initially passed down orally. Al-Mufaddal ibn Salamah († around 904), and a native of Iran Author Ibn Ḫurdāḏbih embellished († about 912) wrote two of the first treatises on the Orient music and partly described imaginatively the origin of that musical instruments from some in the Old Testament called mythical characters. According to Ibn Ḫurdāḏbih have Matūšalaḫ the buckling necked lute 'ūd invented, from the Persian Barbat has developed and is considered the noblest of Arab musical instruments. The long-necked lute ṭanābīr was used maliciously by the Lot people , while the Persians are said to have introduced the harp chang only later . In al-Mas'udi (around 895–957) the maʿāzif go back to Ḍilāl (the biblical Zilla ). Maʿāzif (singular miʿzafa ) was the generic term for stringed instruments with uncut strings, i.e. harps, zithers and lyres . The medieval lyre called miʿzafa was spread across the Red Sea in roughly the same area as today's tanbūra . Lamech (in the Arabic tradition Lamak) invented the drum ṭabl and his son Jubal the lyre kinnor . According to Ibn Ḫurdāṣbih, the introduction of the first flute ( ṣaffāra ) is due to the Kurds . According to this representation, the Arabs themselves did not produce their own musical instruments. In fact, the Arabs took over after the conquest of Sassanidenreichs in the 7th century from the Iranian music the lute tanbour (Arabic ṭunbūr ), the double reed surnāy , the harp (Arabic ǧank ) and later the plucked lute Rubab . A Turkish source from the 17th century also describes the musical influences from foreign peoples in the early Islamic period in the form of a mythical story. After that, in addition to the first muezzin and singer Bilal al-Habaschi , three musicians appeared in the vicinity of the Prophet . They included an Indian timpani who took part in the Prophet's campaigns with a large kettle drum ( kūs ), and a player of the round frame drum al-dāʾira . This was distinguished from the rectangular double-headed frame drums daff ( dufuf , from Hebrew tof ), another Lamak invention.

These popular myths are remarkable because they give the drums the same status as string and wind instruments. This contrasts with the treatises of the Arab philosophers and musicologists, whose theories are in the tradition of ancient Greece. Most Arab authors gave percussion instruments a low ranking or did not mention them at all. From the middle of the 9th century, Arabic translations by Aristotle and later Greek thinkers were in circulation. According to these, the focus of the music-theoretical considerations in the early Islamic period lay, in addition to ethical questions, on the definition of harmonic pitches and proportions, which were linked to cosmological ideas. For al-Kindī (around 800–873) musical instruments created harmony between the universe and the soul of an individual or a certain people. The Indians were their "natural character" in accordance with stringed instruments correspond, the people of Khorasan , the two-stringed, the Byzantines three-string and the Greeks and Babylonians four-stringed instruments. The Persian geographer Ibn Chordadhbeh (around 820 - around 912) also made such national attributions, which stem from tradition or observation , when he gave the Indians the single-stringed zither with calabash resonator kankala , the Byzantines the lyre lūrā , the harp (or Lyre) shilyānī , the wind instrument (string instrument?) Urghūn and the Nabataeans the lute instrument ghandūrā .

Directed against al-Kindī, who was more concerned with Greek music, al-Farabi (around 870–950) concentrated on the Arabic music of his time. In his main musicological works Kitāb al-Mūsīqā al-kabīr ("The Great Book of Music") and Kitāb fi 'l-īqāʿāt ("Book of Rhythms") he described numerous musical instruments with an accuracy that betrays the practicing musician. Contemporaries valued him as an excellent ʿūd player. As the first musical instrument al-Farabi mentions the šāh-rūd , a complicated plucked instrument with two string systems and an extraordinary range of four octaves. He practically derives the tone scales from the mood of the lute ʿūd and, in this context, particularly rejects the New Pythagoreans , who only found their scales by calculating numbers.

For al-Farabi it is fundamental for the classification of the instruments whether they can produce “natural” ( consonant ) tones ( muttafig ) or sound dissonant to the ear ( mutanāfir ); also whether they are suitable for music theory or practically playable. The latter does not allow a clear distinction and Arabic music is “natural” , especially when it is played on the ʿūd and the string rabāb . With decreasing appreciation, its systematic encompasses five groups: (1) human voice, (2) rabāb and wind instruments, (3) plucked string instruments, (4) percussion instruments such as frame drums and kettle drums, and (5) dance. The criterion for the division or the further division is the length of the tone. According to the opinion widespread in Asia, the voice is rated the highest because it can be used to produce long-lasting tones.

With a finer classification, al-Farabi dispenses with the percussion instruments - he only mentions them briefly in the Kitāb fi 'l-īqāʿāt - and sorts the two remaining groups according to the type of sound production. The chordophones are bowed or plucked and further subdivided according to whether they have a string for each tone (harp) or whether the strings produce several tones by shortening them (sounds). He differentiates between wind instruments with and without finger holes and those with one, two or three music tubes. With the double reed instruments ( mizmār , Pl. Mazāmīr ) there are types with connected and with separated tubes. The stringed instruments are divided according to the number of strings and their tuning is described. The main difference between al-Farabi and the ancient Greek and Roman authors is his greater practical knowledge and more precise description of musical instruments and the classificatory distinction between instruments of Arabic and foreign music.

Ibn Sina (around 980-1037) describes in his main work Kitāb al-Shifā ("Book of Healing") musical instruments in detail and divides them into seven groups according to the type of sound generation (plucked, bowed, blown, struck):

- plucked string instruments with frets (short neck lute barbaṭ , long neck lute ṭanbūr )

- plucked string instruments without frets ( šāh-rūd )

- Harps ( chang ) and lyres ( shilyak )

- String instruments ( rabāb )

- Wind instruments (reed instruments mizmār, surnay and bagpipes mizmār al-jarab )

- other wind instruments ( urghanūn )

- Dulcimer ( santūr )

Elsewhere, like al-Farabi, Ibn Sina differentiates according to the number of notes per string and whether more than one note can be played at the same time. The Persian musician Abd al-Qadir (Ibn Ghaybi, † 1435) from Maragha in northwestern Iran wrote in Jami al-Ahlan ("Collection of Melodies") theoretically and practically about music and classified 25 string instruments, 9 wind instruments more precisely than Ibn Sina and 3 percussion instruments. Like al-Farabi, they were further subdivided according to clay production and morphological properties. His list also includes some Chinese instruments, one Indian and one ( urghanūn ) of European origin. String instruments remained the most numerous, most detailed and popular musical instruments, while the drums were associated with folk dances and were otherwise only allowed to be used in the rituals ( samāʿ ) of the Sufis . In contrast to most other authors in the Middle East, who did not mention percussion instruments, the Ottoman scholar Hajji Khalifa († 1657) laid out his treatise on the history and construction of musical instruments Kashf al-ẓunūn ʿan asāmī al-kutub waʾ- funūn ("Explanation of conjectures about the names of books and sciences") has a threefold structure.

While Sufis wrote defenses to justify the use of certain musical instruments in religious rituals, Orthodox Muslims categorically condemned their use. The Shafiite Imam al-Haythamī (1503–1567) from Egypt boasted that he had punished musicians and had their instruments destroyed. In order to be able to condemn the musical instruments individually in his moral writing aimed at the youth, he categorized them into three groups: (1) maʿāzif , some stringed instruments, plus lyres, (2) mazāmīr , wind instruments: flute shabbāba , double clarinet zummāra and (3) awtār , String instruments. First he condemned the percussion instruments: the frame drum duff , then the hourglass drum kūba , cymbals and cymbals, until he finally got to the lute instruments.

China

One of the basic speculations of Chinese philosophy is the all-encompassing harmony ( ho ), which is categorized with a nine-level series of number symbols to reconcile cosmic and cultural (macro and microcosmic) phenomena. In the eighth position are the cardinal points (winds), which correspond to the eight different materials of the musical instruments. The classification of the eight materials characteristic of musical instruments is called eight sounds ( bāyīn ). In earlier times, musical instruments were divided into four categories, as evidenced by the Yo Chi (Treatise on Ritual Music and Dance) dating from the end of the 6th century BC. From other sources of the Zhou dynasty . The eight groups mentioned (of musical instruments?) Bells, drums, pipes, flutes, sound stones, feathers, shields and axes belonged to the four "sound sources" silk, fur, bamboo and stone. Obviously, the “Eight Sounds” didn't exist back then or both material categories were equally popular. The eight sound categories are assigned to a material, a season and a cardinal direction (including wind direction), starting in the north and progressing clockwise. An example of a musical instrument follows in brackets:

- Fell ( gé ) - Winter - North (drums)

- Calabash ( páo ) - winter / spring - northeast (mouth organ sheng )

- Bamboo ( zhú ) - spring - east (bamboo flutes)

- Wood ( mù ) - spring / summer - southeast ( Schraptiger )

- Silk ( sī ) - summer - south (fretboard zither qin )

- Clay / loam ( tǔ ) - summer / autumn - southwest (vessel flute xun )

- Metal ( jīn ) - autumn - west (bells)

- Stone ( shí ) - autumn / winter - northwest (sound stones)

The conceptual background for this classification are the ideas of the all-moving energy Qi and the sounds that represent the signs and forms of expression of the forces of nature. So it is not primarily about the sound qualities that these eight materials have, but about the winds from the corresponding cardinal points that arise through one of the ritual dances to which the respective instrument is played. At the time of the mythical great emperor Shun in the 23rd century BC When, according to the general opinion, the material categories could have arisen, there should have been 800 musical instruments, a number that came about by multiplying 100 by the number of categories.

In the Tang Dynasty (618–907), in addition to the classification of musical instruments, others were introduced for the Chinese musical styles and for the musical ensembles according to the social hierarchy. The bāyīn , who had lost a large part of their magical significance by then, were given a different order, but were otherwise kept unchanged. Some musical instruments such as bone flutes, reed instruments made of leaves and snail horns had never fit into the strict order and numerous foreign musical instruments had been imported from Central Asia in the post-Christian centuries, so that Ma Duanlin (1245–1322) found it necessary, a ninth category called pa yin to open chih wai ("what does not fall under the categories one to eight"). Each of the nine categories was now divided into three parts, according to the use of the instrument in ritual music, foreign music or popular music. The music scholar Zhu Zaiyu (1536–1610) invented two slightly different classifications based on the eight bāyīn groups with subdivisions according to playing style and musical use. In one of the two, he gave the simple, previously little appreciated bamboo flutes first place. This was just one of many changes in the order, the eight materials themselves remained the same over the millennia until today.

Some contemporary Chinese musicologists have used the highly regarded bāyīn in modified form in their publications, while others have criticized them and rejected them altogether. A structural disadvantage of the system is that the categorized material is made to vibrate in drums, string instruments and gongs, but not primarily in the case of bamboo flutes and calabash mouth organs. In 1980 a collective of authors developed a new classification in which Western instruments can also be included to a limited extent. In the top hierarchy, it consists of four groups:

- Percussion instruments in which the sound is formed by striking. Contains 56 instruments. Further subdivided into (a) Idiophone and (b) Membranophone.

- Wind instruments in which the sound is created by air vibrations in a hollow body. Contains 42 instruments. Divided into (a) reed instruments suona , sheng and (b) without reeds (flutes)

- String instruments, the sound is created by taut strings. 56 instruments. Subdivided into (a) plucked with fingers or plectrum ( pipa , concert harp), (b) string instruments ( erhu and violin) and (c) struck string instruments (dulcimer yangqin )

- Keyboard instruments, the presence of keys is crucial. 9 instruments.

The Chinese classifications discussed today are often three-tiered and differentiate according to morphological characteristics and the style of playing, rarely used instruments such as lithophones are occasionally ignored and western instruments can generally only be classified to a limited extent.

South asia

In the Indian tradition, song ( sanskrit gita ), instrumental music ( vadita ) and dance ( nrtya ) represent a unit called sangita , which is of divine origin. The ancient Indian ritual music was performed in a strictly regulated form for the benefit of the gods, so that it could echo loudly from the Kailash , the mountain of the world and seat of the gods, as it says in the 13th chapter of the Mahabharata . She is related to the heavenly musicians, the Gandharvas . According to these mythical beings, the collection of ancient Indian music is entitled Gandharva Veda . Its main features originated in Vedic times and were probably used between 200 BC. BC and AD 200 by Bharata Muni summarized work Natyashastra . According to the Natyashastra , music groups played not only in sacrificial rituals but also in large secular celebrations, processions of the king, weddings, the birth of a son and in dance dramas for which stages were set up outdoors or in closed rooms.

The 28th chapter (1–2) of Natyashastra contains the oldest classification of Indian musical instruments ( vadya , also atodya ). Their four main groups are:

- tata vadya , tense, stringed instruments

- avanaddha vadya , vessels covered with fur, membranophones

- ghana vadya , "firmly", idiophones and

- sushira vadya , "hollow", wind instruments.

This is the basis of the system developed by Hornbostel and Sachs. Already in the Vedic writings from the first half of the 1st millennium BC The word vina (sometimes also vana ), which was obviously used as a collective term for stringed instruments, appears frequently . Their high reputation put them in first place in the classification. Initially, the Indian stringed instruments were bow harps, and it was not until the middle of the 1st millennium AD that the forerunners of the rod zithers, now called vina , emerged. Wind instruments and idiophones have the lowest status after the Natyashastra . The four categories are divided into a main branch and a sub-branch for the respective main and accompanying instruments. Within the stringed instruments, the nine-string bow harp vipanci-vina played with a plectrum ( kona ) and the seven-string bow harp citra-vina ( chitravina , from which the second name for today's South Indian gottuvadyam is derived) from the two subordinate types , the single-stringed lute kacchapi and the same ghosaka , which probably only contributed drone tones and were similar to today's ektara . The main branch of the membranophone included the mridangam , which, like today's khol in Bengal, was originally made of clay ( mrd ), the wooden barrel drum dardara and the hourglass drum panava . The low-pitched jallari and pataha drums were less important . Among the wind instruments, the bamboo flute vamsha (also venu , today bansuri ) was one of the valued instruments in contrast to the snail horns . Further distinctions relate to sound quality. The classification is clearly structured and differs from the rambling mythical narratives that entwine around Indian musical instruments. There is a similarity to the precise and in the Natyashastra much more detailed classified instructions for the dance.

Another ancient Indian classification is assigned to the semi-mythical sage and musician Narada (1st century AD?), Whose three groups are called carma ("skin"), tantrika ("something with strings") and ghana ("solid"). Kohala, a sage who, like Bharata, Narada and some others, is regarded as an authority on music and drama, describes the four categories of Natyashastra in the first half of the 1st millennium with the terms sushira, ghana, carma baddha (“covered with membrane ") And tantri (" string "). Later authors mentioned these names. From the 11th century onwards, scholars appeared who wrote commentaries on Natyashastra or independent treatises on music. Another author named Narada developed Sangitamakaranda in his work in the 10th – 12th centuries . Century a system with five groups. After an initial distinction between spiritual and worldly sounds, he names (1) nakha ("fingernails"), instruments plucked with the fingers, for example vina , (2) vayu ("wind"), wind instruments such as the bamboo flute vamsha , (3 ) carma , instruments covered with a skin like mridangam , (4) loha , metal percussion instruments like tala and (5) sarira , “human instruments” with singing and clapping. On closer inspection, the first four groups deviate somewhat from the known classification, because they are classified according to the place where the sound is created. Otherwise Narada extends the subdivision into main and secondary instruments to: (a) The accompanist repeats the vocal part. (b) The accompanying musician essentially sticks to the given melodic and rhythmic structure, but continues to carry it out and improvises in the pauses. (c) String instrument and drum play independently antiphon to the singer.

In addition to the Sanskrit literature mentioned above, there is the South Indian tradition of literature written in Tamil , the first heyday of which falls in the Sangam era around the 2nd to 6th centuries. The oldest surviving Tamil classification for musical instruments ( karuvi , also "tool"), which consists of five categories and the classification of Narada from the 10th-12th centuries , dates from this period . Century resembles:

- tolekaruvi , also torkaruvi ( tole , "skin"), drums

- tulaikkaruvi ( tulai , "hollow" or "cave"), wind instruments

- narampukkaruvi ( narampu , "animal tendon "), stringed instruments

- mitattrukaruvi , singing voice

- kancakkaruvi ( kancam , "metal"), cymbals , pair cymbals .

In the first half of the 13th century, Sarngadeva wrote the Sangitaratnakara (“The Sea of Music”), a work that has been preserved in several manuscripts and is often quoted. It presents the entire theory of Indian music and dance since ancient Indian times. The four groups are here according to their musical task: (1) suskam , instruments played solo, (2) gitanugam , instruments for singing accompaniment, (3) nrittangam , instruments for dancing accompaniment and (4) dvayanugam , instruments accompanying singing and dance.

Indian music theory was handed down within Hindu literature. There were obviously no style differences between north and south until the 13th century, they only became apparent from the middle of the 16th century. As the influence of Muslim musicians in northern India increased in the 14th century, at the time of the Persian poet and musicologist Amir Chosrau , new musical styles and musical instruments began to develop - sitar and tabla are said to have been introduced around this time, the foundations of music theory and however, the classification of the instruments was retained.

In parallel with the Hindu, from the 6th century BC An independent Buddhist religious and cultural tradition that has been cultivated in South Asia, especially in Sri Lanka , since the decline of Buddhism in India, which began towards the end of the 1st millennium . The ancient Indian Buddhist classification of instruments, which is still known in Sri Lanka today, is called pancaturyanada ("sounds of the five groups of instruments"). The early Sinhala treatises, which also deal with music, categorize musical instruments in a manner similar to that used in the Sanskrit texts. The only difference is that there is hardly any mention of it, because in the teaching tradition of Theravada practiced in Sri Lanka, most musical forms are considered harmful.

Indian musicologists mostly try to maintain the tradition of Natyashastra in their work . KS Kothari published a descriptive list of 300 Indian folk musical instruments in 1968, which he divided into the four known categories and, according to the style of playing, formed further subgroups, for which he took the systematics of Galpin and Hornbostel-Sachs as a model. The appendix contains a list of around 700 Indian musical instruments, the work not claiming to be complete.

Gobind Singh Mansukhani took a similar approach in 1982, who in his work compares Indian classical music with the religious Dhadi chant of the Sikhs when he divides them into melody instruments ( suara vad ) and rhythm instruments ( tal vad ). He subdivides the four main groups according to the style of playing, with string instruments, for example, into plucked or bowed and further: plucked with the fingers or the plectrum.

BC Deva conceived the most comprehensive classification of Indian musical instruments in 1980. It includes all historical Indian instruments and folk musical instruments, but excludes instruments (piano) only played in Western music. The classification is mainly based on the sound generation, but is not strictly logical, but based on practical applicability. He counts the plucked drum ektara among the stringed instruments, although it could just as well belong to the membranophones. With the division according to Dewey's decimal system, there is a functional mixture of Indian and Western taxonomies.

Regional classifications

Kerala

In the southern Indian state of Kerala , a distinction is made between classical musical styles (carnatic music) and religious music, which is played in large temples ( malayalam kshetram ) or in front of village shrines ( kavu ) to accompany rituals or to entertain the faithful at temple festivals. Religious music includes styles of singing ( sopanam sangeetam ) and temple instrumental music ( kshetram vadyam ). All musical instruments played in the temple, with one exception, are used percussive and accordingly classified as tala vadyam ("rhythm instrument ") according to their use in the ensemble . In addition to the drums chenda , timila , idakka , madhalam and maram, the rhythm instruments include the small pair cymbals elathalam and the hand bell chengila as well as the curved natural trumpet kombu . The exception that plays melodies is the only other wind instrument, the short cone oboe kuzhal . There are no stringed instruments in the temple, only the villadi vadyam bow is occasionally used in the thayampaka musical style for the rhythmic accompaniment of the double-headed cylinder drum chenda . The musical bow is considered a rhythm instrument , but not a kshetram instrument.

Another distinction is made according to the type of temple ritual. Musical instruments used for the rituals before the higher gods ( devas ) inside the temple are called devavadyam . These include the timila, idakka, maram , the snail horn ( shankh ) and the chengila bell . The drum chenda is rated differently depending on how it is played. When struck only on the lower-sounding side, it is called valantala chenda and is one of the devavadyam ; when struck on the higher-sounding side, the same drum is called itantala chenda and is one of the asuravadyam , i.e. the musical instruments used to honor the lower deities ( asuras ). The latter also includes the drum madhalam , the pair cymbal elathalam and the wind instruments kombu and kuzhal .

Tibet

The Tibetan cult music in the monasteries is an indispensable part of the rituals and is subject to strict implementation rules in order to meet the requirements as a sacrifice to the Tibetan deities ( Buddhas , Bodhisattvas , tantric beings ( yidam ) and guardian figures). Their daily practice is in contrast to the Theravada teachings of Sri Lanka and the Southeast Asian mainland, which largely rejects music in the rituals. The Buddhist scholar Sakya Pandita (1182–1251) wrote the largest medieval treatise on the theoretical concept of Tibetan music. The textbook with the title rol-mo'i bstan-bcos comprises around 400 verses, in which three chapters describe text recitations, compositional principles and the performance practice of chants and monastic rituals. Monks learn the recitation formulas and ritual practices from the songbooks ( dbyangs-yig ) and the manuals with the rules of the order in the respective teaching tradition.

Rol-mo byed pa means “to make music” in Tibetan , the word rol-mo describes the “sound of music” and, in the narrower sense, horizontally struck pair cymbals. This shows the primacy of the percussion instruments ( brdung-ba ) and especially the cymbals: next to the rol-mo, the vertically struck silnyen . At the other end of the scale are the stringed instruments, which are brought to the monastery as offerings but are not allowed to be played there. The four classical categories of Tibetan musical instruments have been known from sources since the 12th century. Further subdivisions result from the interpretation of the existing texts:

- brdung-ba , "struck instruments", divided into (a) pair cymbals ( rol-mo, silnyen ), (b) drums nga , mostly double-headed frame drums with stem ( chos-nga ) and without stem, and (c) bronze gongs mkhar nga

- bud-pa , "blown instruments": (a) natural trumpet dung with subdivision according to shape and material, among other things, long trumpet dung chen and snail horn dung kar as well as (b) double reed instrument rgya-gling

- khrol-ba , "curved instruments": (a) hourglass drum damaru , (b) handle hand bell drilbu and (c) bell gshang held with the opening upwards

- rgyud-can , "strung" or rgyud-rkyen , "cause and effect", stringed instruments (tubular fiddle pi wang , long-necked lute dran-nye )