statue of Liberty

| statue of Liberty | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

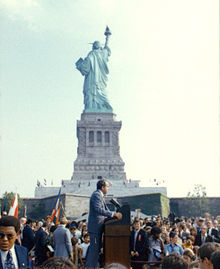

| General view of the Statue of Liberty |

|

| National territory: | United States |

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | (i) (vi) |

| Reference No .: | 307 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1984 (session 8) |

The Statue of Liberty ( English Statue of Liberty , officially Liberty Enlightening the World , and Lady Liberty , French La Liberté éclairant le monde ) is one of Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi created neoclassical colossal statue in New York . It stands on Liberty Island in New York Harbor , was inaugurated on October 28, 1886 and is a gift from the French people to the United States . The statue has been part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument since 1924 and classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO since 1984 .

The statue represents the robed figure of Libertas , the Roman goddess of freedom . Standing on a solid base made of a copper shell on a steel frame, holds up a gilded torch with the right hand and holds a tabula ansata in the left hand with the date of the American Declaration of Independence . There is a broken chain at her feet. The statue is considered a symbol of freedom and is one of the most recognizable symbols of the United States. With a figure height of 46.05 meters and a total height of 92.99 meters, it is one of the tallest statues in the world , until 1959 it was the tallest.

Bartholdi was inspired by the French lawyer and politician Édouard René de Laboulaye , who declared in 1865 that any monument erected in honor of American independence must be a joint project of the peoples of France and the United States. Due to the tense political situation in France, work on the statue only began in the early 1870s. In 1875, Laboulaye proposed that the French should finance the statue and the Americans the base and provide the building site. Bartholdi completed the head and the torch arm before the statue's final appearance was determined. These parts were presented to the public at exhibitions. Financing turned out to be difficult, especially on the American side (for the base), so that work on the base in 1885 was threatened with discontinuation due to lack of money. Joseph Pulitzer then ran a fundraising campaign with his newspaper New York World to complete the project. The statue was finally prefabricated in France, dismantled and transported to New York and assembled on the island then known as Bedloe's Island . It was dedicated by President Grover Cleveland on October 28, 1886, Bartholdi Day.

The United States Lighthouse Board , the federal authority for lighthouses, was responsible for the maintenance and administration until 1901 . The War Ministry then took over these tasks. The statue has been under the jurisdiction of the National Park Service since 1933 . In 1938 it was closed to the public for the first time due to renovation work. In the early 1980s, the building fabric was so worn out that extensive restoration was necessary. From 1984 to 1986 the torch and much of the internal structure were replaced. After the attacks of September 11, 2001 and after Hurricane Sandy , the statue was temporarily closed.

Planning and construction history

Original idea

The idea for the Statue of Liberty project stems from a remark made by the French lawyer and politician Édouard René de Laboulaye in 1865. Speaking after a celebratory dinner at his home near Versailles , the avid Northerners during the Civil War, remarked : “If a memorial should be erected in the United States to commemorate its independence, then I think it is only natural if it is created by united forces - a joint work of our two nations. "

Laboulaye's remark was not intended as a concrete suggestion, but it did inspire the sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi , who was present as a guest at the dinner. In view of the monarchist state system in France under Emperor Napoleon III. , which stood in stark contrast to the republican ideals of the United States, Bartholdi initially took no further steps except to discuss the idea with Laboulaye. Instead, he approached Ismail Pasha , the Ottoman khedive of Egypt , and presented him with the plan to build a lighthouse in Port Said at the northern end of the Suez Canal in the form of a robed ancient fellachin holding up a torch. Bartholdi made sketches and models, but the statue was never erected. A classic model for the Suez project was the Colossus of Rhodes . This bronze statue of the Greek sun god Helios is said to have been over 30 meters high, stood at a port entrance and held up a torch to guide ships.

The Franco-Prussian War , in which Bartholdi served as a major in the militia, further delayed the American project. During the war, Napoleon III. captured and deposed. Bartholdi's home region of Alsace was lost to the German Empire and the more liberal Third Republic was formed in France . Since Bartholdi had already planned a trip to the United States, he and Laboulaye agreed that the time was ripe to introduce the idea to influential Americans. In June 1871, Bartholdi traveled to New York with a letter of recommendation from Laboulaye . There his gaze fell on Bedloe's Island in Upper New York Bay . Every arriving ship had to pass this island, which is why it seemed suitable as a location for a statue. The island was ceded to the federal government by the New York State Parliament in 1800 so that defenses could be built there. In addition to influential New Yorkers, Bartholdi also visited President Ulysses S. Grant , who assured him that using the island as a building site would not be a problem. Bartholdi toured the United States by railroad and met with numerous people whom he believed were benevolent to the project. However, he was concerned that public opinion on both sides of the Atlantic was not yet approvingly enough, which is why he and Laboulaye decided to hold off a public campaign.

Bartholdi had made a first model of his concept in 1870. The son of the artist John La Farge later claimed that Bartholdi drew the first drafts during his stay in the USA in his American friend's studio in Rhode Island . After returning to France, Bartholdi developed his concept further. He also worked on a number of sculptures designed to strengthen French national sentiment after the lost war. One of these works was the Lion of Belfort , a monumental sculpture of red sandstone under the citadel of Belfort . The defensive lion, 22 meters long and eleven meters high, embodies an emotionality typical of romanticism , which Bartholdi later transferred to the Statue of Liberty.

Appearance, style and symbolism

Bartholdi and Laboulaye discussed how the idea of freedom could best be implemented. In early American history, there were two female characters as cultural symbols of the nation. Columbia was considered the personification of the United States, much like Marianne in France. She had replaced the previous figure of an Indian princess, who was now considered uncivilized and insulting to Americans. The other significant female figure in American culture was an embodiment of freedom, derived from the goddess of freedom Libertas , who was worshiped in the Roman Empire in particular by freed slaves . A figure of freedom adorned most American coins of the period and influenced numerous works of art, including Thomas Crawford's Statue of Freedom on the dome of the Capitol . A figure of freedom was also on the Great Seal of France.

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century artists seeking republican ideals often resorted to an embodiment of freedom. Bartholdi and Laboulaye, however, avoided the image of revolutionary freedom, such as that portrayed in the painting Freedom leads the people by Eugène Delacroix . In this painting, reminiscent of the French July Revolution of 1830 , exposed and violent freedom leads an armed crowd. Laboulaye had no sympathy for revolutions and therefore wanted a fully clothed figure in flowing robes. Instead of the violent impression in Delacroix's work, Bartholdi wanted to give the statue a peaceful appearance, which is why it should carry a torch as a symbol of progress.

Crawford's statue originally wore a pileus , a head covering worn by freed slaves in the Roman Empire. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis , a southerner and later President of the Confederate States , was concerned that the pileus on the Statue of Freedom could be understood as a symbol of abolitionism and ordered that it be replaced with a helmet. Delacroix's figure of freedom also wore a pileus, and Bartholdi initially considered equipping his own figure with it as well. In the end, however, he chose a crown for his headgear, thereby avoiding an allusion to Marianne, who always wears a pileus. The seven-pointed crown is borrowed from the halo of ancient Helios or Sol representations. It originally symbolized the sun, but here the seven seas and the seven continents . Together with the torch, they should proclaim the message that freedom illuminates the world.

Bartholdi's early models were all the same in concept: a woman figure in the neoclassical style, who represents freedom, wears a stole and a pella (dress and cape, common in depictions of Roman goddesses) and holds up a torch. The face is said to have been modeled after that of his mother, Charlotte Beysser Bartholdi. Other sources refer to Isabella Eugenie Boyer, wife of Isaac Merritt Singer , as the model. Bartholdi designed the figure with an expressive, uncomplicated silhouette. This should make it stand out from the harbor scenery and the ship's passengers would be able to see it from different angles when they approached Manhattan . He gave the figure classic contours and used a simplified type of modeling. He wanted to do justice to the enormous dimensions of the project and its solemn purpose. Bartholdi wrote about his technique:

“The surfaces should be clear and simple, determined by a bold and clear design, accentuated at the important points. Avoid enlarging the details or multiplying them. By exaggerating the forms to make them more clearly visible or enriching them with details, we would destroy the proportions of the work. After all, like the design, the model should have a summarizing character, as one would with a quick draft. It is necessary that this character be the product of will and observation, and that the artist, through the concentration of his knowledge, find the form and the line in their greatest simplicity. "

In addition to changing the statue's headgear, there were other design changes as the project evolved. Bartholdi imagined that the statue should hold a broken chain, but then found that this could have a divisive effect in the period after the Civil War. The statue actually rises above a broken chain, but this is partially hidden by the robe and is difficult to see from the ground. Bartholdi was initially unsure what to hold the statue in her left hand. His choice fell on a tabula ansata as a symbol of justice. He admired the United States Constitution , but chose JULY IV MDCCLXXVI (July 4, 1776) for the inscription , linking the date of the Declaration of Independence with freedom.

Consultations with the foundry Gaget, Gauthier & Cie. let Bartholdi come to the conclusion that the cladding should consist of copper plates that were brought into the desired shape by driving . One benefit of this process was that the statue would be light in relation to its volume - the copper only had to be 2.4 millimeters thick. Bartholdi specified a height of 151 feet and 1 inch (46.05 meters) for the statue . He managed to get one of his former teachers, the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc , interested in the project. Viollet-le-Duc provided a brick pillar inside the statue to which the paneling would be anchored.

Announcement and first work

In 1875 the political situation in France had stabilized and the economy recovered. Growing interest in the upcoming Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia prompted Laboulaye to seek public support. He presented the project in September 1875 and announced the establishment of the Franco-American Union, which was to raise the funding. With the announcement, the statue was given a name, Liberty Enlightening the World in English and La Liberté éclairant le monde in French; translated both means: "Freedom, illuminating the world". The French were to finance the statue, the Americans the pedestal. The announcement generated generally positive responses, although many French resented the United States' lack of support during the war. French monarchists rejected the statue, if only because the proposal came from the liberal Laboulaye, who had recently been appointed senator for life. Laboulaye organized events to secure the benevolence of the rich and powerful. This included a special performance on April 25, 1876 at the Paris Opera with a new cantata by Charles Gounod called La Liberté éclairant le monde.

Despite the initial focus on the elites, the Union managed to raise money from all walks of life; 181 French parishes were also among the donors. Laboulaye's political allies supported the cause, as did descendants of the French contingents in the American War of Independence . Donations also came from less idealistic circles who were hoping for American support in the French attempt to build a Panama Canal . The copper trading company Japy Frères donated all the copper required, valued at 64,000 francs . The copper is said to come from a mine near Visnes on the Norwegian island of Karmøy , but this could not be determined with certainty .

Although the planning for the statue was not yet complete, Bartholdi began in the workshop of Gaget, Gauthier & Cie. to make the head and the right arm with the torch. In May 1876, he traveled to the Centennial Exhibition as a member of the French delegation and made arrangements for a huge painting of the statue to be shown in New York as part of the centenary. The arm did not arrive in Philadelphia until August, which is why it was not listed in the exhibition catalog. While some reports identified the plant correctly, others spoke of the "colossal arm" (Colossal arm) or "Bartholdi electric light" (Electric Light Bartholdi) . A number of monumental works of art stood on the exhibition grounds that vied for the attention of visitors, including an oversized fountain by Bartholdi. Still, towards the end of the exhibition, the arm proved a popular attraction, and visitors stepped onto the torch's balcony to survey the grounds. After the exhibition ended, the arm was transported to New York, where it could be seen in Madison Square Park for several years before it was brought back to France to be attached to the statue.

During his trip to the United States, Bartholdi came into contact with various groups and pushed for the formation of an American committee of the Franco-American Union. Donation committees were formed in New York, Boston and Philadelphia to finance the foundation and base. The New York group ended up taking most of the fundraising responsibility and is often referred to as the "American Committee." One of the members was Theodore Roosevelt , then 19 , future Governor of New York and President of the United States. On March 3, 1877, on the last day of his term in office, President Grant signed a resolution authorizing the President to receive the statue from France and to determine a location. His successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, followed Bartholdi's recommendations and chose Bedloe's Island.

Working in France

After returning to Paris in 1877, Bartholdi focused on completing the head that was shown during the 1878 World's Fair . The fundraising campaign continued, including the sale of models of the statue. Admission tickets to the Gaget, Gauthier & Cie. available where visitors could see the work. The French government approved a lottery. The prizes included a valuable silver plate and a terracotta model of the statue. By the end of 1879 around 250,000 francs were collected.

The head and arm were created with the help of Viollet-le-Duc. He died in September 1879, leaving no evidence of how he would have made the connection between the copper cladding and the proposed brick pillar. In the following year, Bartholdi managed to secure the services of the innovative engineer Gustave Eiffel . He and his chief designer Maurice Koechlin decided to abandon the pillar and instead build an iron framework tower. Koechlin did not use a completely rigid structure, as otherwise the stress would lead to breaks in the copper cladding. The statue should move easily with the wind and the metal should be able to expand in the summer heat. For this purpose, he constructed a network of smaller frames - trusses , with which he connected the supporting structure and the copper plates. These carriers had to be manufactured individually in a labor-intensive process. To prevent contact corrosion between the copper cladding and the iron supporting structure, Eiffel had the cladding insulated with asbestos , which had previously been soaked in shellac . Changing the material of the supporting structure from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for assembling the statue. Originally, he wanted to mount the cladding in place, parallel to the construction of the brick pillar. Now he decided to prefabricate the statue in France, dismantle it to transport it to the United States and have it reassembled on Bedloe's Island.

With this construction, the statue became one of the earliest examples of a curtain wall in which the exterior of the structure only bears its own weight and is supported by a supporting structure inside. Eiffel added two spiral staircases to make it easier for visitors to climb to the lookout point in the crown. Access to the viewing platform around the torch was also guaranteed, but the narrowness of the arm only allowed a narrow, twelve-meter-long ladder. Eiffel and Bartholdi carefully coordinated their work so that finished parts of the cladding fit exactly onto the supporting structure.

During a ceremony on October 24, 1881, Levi P. Morton , then American ambassador to France , riveted the first copper plate to the statue's big toe. The cladding was not made in the exact order from bottom to top. The work progressed simultaneously on different segments, which often seemed confusing for visitors. Bartholdi awarded some orders to subcontractors, for example the fingers were made according to his exact specifications in a coppersmith's in the southern French city of Montauban . In 1882 the statue was finished to the waist; an event that Bartholdi celebrated by inviting journalists to lunch on a platform inside the statue. Laboulaye died in May 1883, his successor as chairman of the French committee was Ferdinand de Lesseps , the builder of the Suez Canal. The completed statue was presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and Lesseps announced that the French government would cover the cost of transportation to New York. When the work on the base had progressed sufficiently, the statue was dismantled into its 350 individual parts and packed in 214 boxes for transport and transported across the Atlantic with the freighter Isere through stormy weather.

Fundraiser, public criticism and erection of the statue

The American committee had great difficulty raising funds. The economic depression after the founder crash of 1873 lasted for over a decade. The Statue of Liberty wasn't the only project that suffered from a lack of funds; For example, the work on the Washington Monument dragged on with several interruptions over three and a half decades. There was criticism of both Bartholdi's statue and the fact that the Americans had to pay the pedestal for this gift. In the years following the Civil War, the public preferred realistic works of art depicting heroes and events in American history, as opposed to allegories such as those intended to be depicted in the Statue of Liberty. There was also a prevailing opinion that works of art in public spaces should be designed by Americans. The fact that the Italian-born Constantino Brumidi had been commissioned to decorate the Capitol aroused fierce criticism, although the artist had meanwhile been naturalized. The magazine Harper's Weekly said, Bartholdi had both can donate the pedestal the statue also and the New York Times stated: " No true patriot can countenance any search expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances. ”(German:“ No true patriot can approve of any expenditure for bronze women given the current state of our finances. ”) In view of this criticism, the American committee did little for several years.

The foundation for Bartholdi's statue was to be set in Fort Wood. This disused military base was built on Bedloe's Island between 1807 and 1811. It had hardly been used since 1823, with the exception of the Civil War, when the military ran a recruiting office there. The dividing of the fortress structure was in the shape of an eleven-pointed star. The foundation and the base were aligned to the southeast so that ship passengers approaching New York harbor from the Atlantic could see the statue. In 1881 the New York Committee commissioned the architect Richard Morris Hunt to design the base. Hunt came up with a detailed plan and estimated the construction would take about nine months. He suggested building the base 114 feet (34.75 meters) high. Faced with funding problems, the committee reduced the height to 89 feet (27.13 meters).

Hunt's base design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals. The large mass is fragmented with architectural details so that attention is drawn to the statue. The base has the shape of a truncated pyramid ; the side length is 62 feet (18.90 meters) at the base and 39.4 feet (12.01 meters) at the top. The four sides look identical. Above the doors on each side there are ten golden discs, on which, according to a proposal by Bartholdi, the coats of arms of the then 40 federal states should be placed, but this was ultimately not done. Above that there is a balcony on each side framed by columns. Bartholdi placed a viewing platform near the base, above which the statue itself rises. According to the writer Louis Auchincloss, "the pedestal craggily evokes the power of ancient Europe over which the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty rises" (" craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty." ”) . The committee hired former Army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction. Construction of the 15-foot (4.57-meter) deep foundation began on October 9, 1883, and the foundation stone was laid on August 5, 1884. According to Hunt's original concept, the base was to be made of solid granite . Financial considerations again forced him to change his plan. The final plan called for cement walls up to 6 meters thick, clad with granite blocks. The concrete mass produced was the largest in the world until then. For this purpose, the German company Dyckerhoff in Amöneburg delivered 8000 barrels of Portland cement .

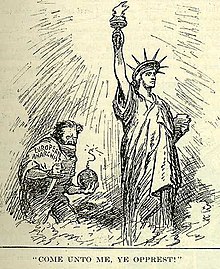

Fundraising for the statue began in 1882, and the committee organized a large number of related events. The poet Emma Lazarus was asked to contribute to such an event, an auction of works of art and manuscripts, by donating an original work. She initially refused, on the grounds that she could not write a poem about a statue. At that time she was also busy helping refugees who had fled anti-Semitic pogroms in Eastern Europe. These refugees were forced to live in conditions which the wealthy Lazarus had never experienced. She saw a way to link her sympathy for the refugees to the statue. The result was the sonnet The New Colossus , including the symbolic lines “ Give me your tired, your poor / Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free ” (German: “Give me your tired, your poor / your enslaved masses who long for it, to breathe freely ”) .

Even with these efforts, donations remained lower than hoped. In 1884, Grover Cleveland , governor of New York, vetoed a grant of $ 50,000. A similar attempt in Congress to raise $ 100,000 (enough to complete the project) failed in 1885 when Democratic representatives refused to approve the transfer. The New York Committee, which had only $ 3,000 in the bank, suspended work on the base, which put the project at risk. Groups in other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to cover all of the construction costs and in return asked for the statue to be relocated. Joseph Pulitzer , editor of New York World newspaper , announced a fundraising campaign that would raise $ 100,000. He promised to publish the name of each donor, no matter how small the amount of money donated.

When the donations began to pour in, the committee resumed work on the base. In 1885, New Yorkers displayed their regained enthusiasm when the French ship Isère , carrying the boxes containing the dismantled parts of the statue, arrived in New York Harbor on June 17th. Around 200,000 people lined the docks and hundreds of ships set sail to welcome the Isère . On August 11, 1885, after five months of daily calls for funds, New York World announced that it had raised $ 102,000 from 120,000 donors, and that 80 percent of the total was donations of less than one dollar.

Despite the success of the fundraising campaign, the base was not completed until April 1886. Immediately afterwards, the assembly of the statue began. Eiffel's iron framework was put together inside the concrete base and anchored to steel girders. Then the copper plates were carefully attached. Due to the insufficient width of the base, it was not possible to erect a scaffolding and the workers hung on ropes to fix the copper plates. However, there was no fatal accident. Bartholdi had planned to install spotlights on the balcony of the torch covered with gold leaf to illuminate it. A week before the inauguration, the Army Corps of Engineers rejected this proposal, fearing that the pilots on passing ships could be blinded. Instead, Bartholdi had portholes cut into the torch and housed the headlights. A small power plant has been installed on the island for statue lighting and other electrical needs. After the cladding was completed, Frederick Law Olmsted , the designer of Central Park and Prospect Park , oversaw the cleanup work on the island.

inauguration

The inauguration ceremony took place on the afternoon of October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland, former Governor of New York, was the patron of the ceremony. In the morning a parade was held in New York, the number of spectators is estimated at several hundred thousand to one million. Cleveland led the parade, then went into the stands to watch brass bands and marching bands from across the country go by. General Stone appeared as Grand Marshal of the parade. The pageant route began in Madison Square , where the arm was once exhibited, and led through Fifth Avenue and Broadway to Battery Park on the southern tip of Manhattan. The pageant made a small detour down Park Row to pass the New York World headquarters . While passing the New York Stock Exchange , traders threw stock ticker strips of paper out of the windows, thus establishing the New York tradition of the confetti parade .

The nautical parade started at 12:45 p.m. President Cleveland boarded a yacht that took him to Bedloe's Island. Ferdinand de Lesseps made the first speech on behalf of the French Committee, followed by the Chairman of the New York Committee, Senator William M. Evarts . A French flag was draped over the face of the statue and should be removed to reveal at the end of Evarts' speech. But Bartholdi misunderstood a break as a conclusion and let the flag drop prematurely. The cheering that set in brought Evarts' speech to an abrupt end. Cleveland spoke next, who declared: “ A stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression until Liberty enlightens the world. ”(German:“ A stream of light should penetrate the darkness of ignorance and oppression of man until freedom illuminates the world. ”) Bartholdi, who was seen near the podium, was asked to say something as well, but he declined from. The well-known speaker Chauncey Depew concluded with an excessively long address.

This ceremony was reserved for invited guests only, the public was not given access to the island. The only women present were Bartholdi's wife and Lesseps' granddaughter. Officials had feared women could be injured in the crowd. Suffragettes from the area, offended by the restriction, rented a boat and approached the island. The leaders of the group made their own speeches, extolling the embodiment of freedom in women and calling for women to vote. An officially planned fireworks display had to be postponed to November 1st due to bad weather.

Shortly after the inauguration, the African American newspaper Cleveland Gazette demanded that the statue's torch not shine until the United States was indeed a free nation:

'Liberty enlightening the world', indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the 'liberty' of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being 'ku-kluxed ', perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the 'liberty' of this country 'enlightening the world', or even Patagonia, is ridiculous in the extreme.

“'Freedom illuminates the world' indeed! The expression disgusts us. This government is a screaming farce. It cannot protect its citizens within its own borders, or rather it does not. Throw the Bartholdi statue together with the torch and everything into the ocean until the 'freedom' of this country is such that it is possible for a staid and hardworking colored person to earn his living and that of his family in a decent way, without being kukluxed ', likely to be murdered without his daughter and wife being treated in shocking ways and property being destroyed. The idea that the 'freedom' of this country 'illuminates the world', or even Patagonia, is deeply ridiculous. "

Further development

Lighthouse Board and War Department (1886–1933)

When the torch was lit on the evening of the inauguration, it was barely visible from Manhattan. The New York World described the glow as " more like a glowworm than a beacon " (German: "more like a glowworm than a beacon"). Bartholdi suggested gilding the statue to increase the light reflection, but this turned out to be too expensive. The United States Lighthouse Board , the federal agency responsible for lighthouses, took over the statue in 1887 and promised to equip the torch with equipment for increased luminosity. Despite these efforts, the statue remained practically invisible at night. When Bartholdi returned to the United States in 1893, he suggested further measures, all of which proved ineffective. He successfully campaigned for improved lighting inside the statue so that visitors could better perceive Eiffel's design. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt , once a member of the New York Committee, ordered the statue to be handed over to the War Department because it had not proven itself as a lighthouse. During the military administration of Bedloe's Island a unit of the Army Signal Corps was stationed on the island until 1923 , after which the military police.

The statue quickly became a landmark. Tales of immigrants who entered via New York reported an uplifting feeling the first time they saw the statue. One immigrant from Greece recalled:

“I saw the Statue of Liberty. And I said to myself, 'Lady, you're such a beautiful! [sic] You opened your arms and you get all the foreigners here. Give me a chance to prove that I am worth it, to do something, to be someone in America. ' And always that statue was on my mind. "

“I saw the Statue of Liberty. And I said to myself, 'Lady, you are such a beauty! You opened your arms and brought all foreigners here. Give me a chance to prove that I'm worth doing to be someone in America. ' And this statue was always on my mind. "

Originally the statue was a dull copper color; shortly after 1900, a green patina spread due to oxidation . First press reports about it appeared in 1902, four years later it covered the entire statue. Convinced that the patina was a sign of corrosion, Congress approved $ 62,800 to give the statue a thorough paint job. There were considerable public protests against the exterior painting. The Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) examined the patina to see whether it had any harmful effects and came to the conclusion that it protected the cladding more, softening the contours and thereby making the statue more beautiful. The statue was then only painted on the inside. The USACE also installed an elevator to transport visitors from the base to the top of the plinth.

On July 30, 1916, during the First World War , German saboteurs carried out a bomb attack on the Black Tom Peninsula in Jersey City , not far from Bedloe's Island (now part of Liberty State Park ). Around 1000 tons of ammunition, which were supposed to be shipped to the UK and France, exploded and seven people died. The statue suffered minor damage, mostly to the torch arm, and was closed for ten days. Repair costs for the statue and buildings on the island were around $ 100,000. The narrow ascent to the torch was closed for public safety reasons and has remained so to this day.

In the same year Ralph Pulitzer , who had replaced his father as editor of New York World , started a fundraising campaign. $ 30,000 was to be raised for a lighting system to illuminate the statue at night. Pulitzer claimed there were 80,000 donors, but the campaign failed. A wealthy patron paid for the difference in secret, which only came out in 1936. An underwater cable was used to connect the island to the mainland power grid and floodlights were placed along the walls of Fort Wood. Gutzon Borglum , who later created Mount Rushmore , redesigned the torch, replacing much of the original copper with painted glass windows. On December 2, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson turned on the lights with a telegraph button. She bathed the statue in brilliant light.

After the US entered the war on April 6, 1917 , the statue was featured frequently on recruitment posters and advertisements for Liberty Bonds (war bonds). It was supposed to make the population aware of the war goal, to secure freedom, and to remind them that the embattled France had given the USA the Statue of Liberty. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge used the authority conferred by the Antiquity Act and declared Bedloe's Island with the Statue of Liberty to be the Statue of Liberty National Monument . The only successful suicide occurred five years later: a man climbed out of one of the windows in the crown and jumped into the depths.

National Park Service (1933–1982)

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt assigned responsibility for the statue to the National Park Service (NPS). From 1937 the NPS was responsible for all of Bedloe's Island. After the army withdrew, the NPS began converting the island into a park. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) demolished most of the old buildings, flattened the eastern end of the island and replanted it. She also set granite steps for a new public access to the statue from the rear. The WPA also performed restoration work on the statue, temporarily removing the rays from the crown to replace its rusted supports. Rusted cast-iron steps in the base and in the upper part of the stairs inside the statue were replaced with new ones made of reinforced concrete. Copper cladding was installed to prevent further damage from rainwater seeping through the base. The statue was closed to the public from May to December 1938.

During the Second World War , the statue remained open to visitors but was not lit up at night due to the blackout . The lighting was switched on for a short time on December 31, 1943 and June 6, 1944 ( D-Day ) when the lights gave the signal "short-short-short-long", the Morse code for V for Victory ("victory") sent. New, powerful lighting was installed in 1944/45 and from May 8, 1945 ( VE Day ) the statue was lit again after sunset. The lights were only on for a few hours each evening; since 1957 the statue has been illuminated continuously every night. In 1946, the publicly accessible part inside the statue was covered with a special plastic film so that graffiti can be washed off.

In 1956, Congress decided to rename Bedloe's Island to Liberty Island; a suggestion that Bartholdi had already made. The law also created the prerequisite for funding an immigration museum on the island. Backers viewed this as approval for the project, but the government delayed releasing the funds. President Lyndon B. Johnson declared neighboring Ellis Island a part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965 . In 1972, the Immigration Museum at the base of the statue finally opened with a ceremony led by President Richard Nixon . Due to a lack of financial resources, the museum had to be closed in 1991 after a new museum was opened on Ellis Island .

In 1976, the NPS installed a new lighting system to mark the United States' bicentenary. The statue was the center of Operation Sail , a regatta of tall ships from around the world that regularly called New York Harbor on July 4, 1976 Liberty Iceland circumnavigated. The feast day ended with a large firework display near the statue.

Restoration and further development since 1982

As part of the plans for the centenary of the statue in 1986, French and American engineers examined the structure in depth. They concluded in 1982 that the statue needed extensive restoration. The right arm was improperly attached to the main body. It swayed more and more in strong winds, so that there was a considerable risk of falling. In addition, the head was mounted about two inches to the side of the center point and one of the beams drilled a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. The frame structure was badly corroded and around two percent of the panels in the outer shell had to be replaced. Although the problem with the frame structure had been recognized as early as 1936 when some cast-iron replacement beams were fitted, most of the corrosion was masked by layers of paint that had been applied over the years.

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Centennial Commission , led by Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca , to raise funds. The commission managed to raise more than $ 350 million in donations. This fundraising campaign was one of the first to involve companies for marketing purposes ( cause marketing ).

In 1983, American Express advertised itself by donating a cent to the renovation for every transaction made with a credit card. That campaign alone raised $ 1.7 million.

In 1984 the statue was scaffolded due to the renovation work and closed to the public. The layers of paint that had been stuck to the inside of the copper cladding over decades were removed with liquid nitrogen donated by Union Carbide . Two layers of coal tar , which had been applied when the statue was built to seal leaks and prevent corrosion, were removed by the sodablasting process without further damaging the copper. The soda required for this was provided by Church & Dwight . An asbestos- based substance, which Bartholdi had unsuccessfully used to prevent contact corrosion, hampered the work of the restorers. Workers inside the statue had to wear protective clothing with built-in breathing apparatus . Holes in the copper cladding were repaired and, where necessary, replaced with new copper. The replacement panel came from the roof of Bell Laboratories , which had a similar patina; In return, the laboratory received parts of the old cladding for testing purposes. It turned out that since the 1916 amendments, water had entered the torch, which is why it was replaced with a copy. The restorers considered replacing the arm and shoulder, but the National Park Service insisted on repairs.

The restoration also included replacing the entire anchorage. The puddled iron bars that Eiffel had used were removed step by step. The new rods that are attached to the pylon are made of low-carbon stainless steel , the rods that now hold the clamps to the cladding are made of ferrous alloy, an alloy that bends slightly when the statue moves and returns to its original position. To prevent the beam and arm from touching each other, the beam has been realigned a few degrees. The lighting was also replaced one more time; Since then, halogen lamps have been throwing light beams onto certain areas of the base, thereby highlighting them. In the place of an inconspicuous entrance in the base built in the 1960s, there was a wide portal with monumental bronze doors on which the renovation is symbolically depicted. A modern elevator gives people with disabilities access to the pedestal's viewing area. There was also an emergency elevator that goes up to the height of the statue's shoulder.

The statue's reopening and centenary celebrations from July 3-6, 1986 were called Liberty Weekend . On July 4th there was a new edition of Operation Sail. One day later, Ronald Reagan rededicated the statue in the presence of French President François Mitterrand . The restoration project won the American Society of Civil Engineers' Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award in 1987 .

Immediately after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 , Liberty Island was closed to the public. At the end of 2001 the island could be re-entered, but the base and the statue remained restricted area. Access to the base was permitted again on August 3, 2004, but the National Park Service announced that visitors could not be allowed to enter the statue for security reasons. The authority justified this measure by stating that an evacuation would be difficult in an emergency.

Ken Salazar , Secretary of the Interior in Barack Obama's administration, announced on May 17, 2009 that the statue would be reopened to the public on July 4th as a "special gift to America". Since then, the number of visitors who were allowed to climb up to the crown per day was limited. After the 125th anniversary on October 28, 2011, the statue was closed for one year in order to build a new staircase system inside, with which modern safety requirements are met and in future more people can visit the statue at the same time. Just one day after reopening on October 28, 2012, the statue had to be closed again due to the effects of Hurricane Sandy . The statue itself was not damaged, but parts of the infrastructure in the base were destroyed. The renovation lasted until the following summer; The Statue of Liberty was reopened on the national holiday, July 4th, 2013.

sightseeing

Entry to the Statue of Liberty National Monument is free. However, all visitors are dependent on using the ferries for a fee, as private ships and boats are not allowed to dock on the island. State Cruises has held the concession for transportation and ticket sales since 2007 . It replaced the Circle Line company , which had previously operated ferry services since 1953. The ferries, which leave from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and Battery Park in Lower Manhattan , also operate via Ellis Island, so that a tour is possible. Visitors who want to enter the pedestal must be in possession of an additional, free entrance ticket.

Inscriptions, plaques and tributes

There are several memorial plaques on and near the Statue of Liberty. A plaque on the copper cladding immediately under the feet announces that the statue represents freedom, designed by Bartholdi and produced by the Paris-based company Gaget, Gauthier et Cie. was built. Another plaque, also provided with Bartholdi's name, identifies the statue as a gift from the French people who “ honors the alliance of the two nations in achieving independence for the United States” and confirms “their enduring friendship” (“ honors the Alliance of the two Nations in achieving the Independence of the United States of America and attests their abiding friendship ”). A plaque from the New York Committee commemorates the fundraising campaign to build the base. The foundation stone also has a plaque placed by the Freemasons .

Friends of the poet Emma Lazarus donated a bronze plaque with the poem The New Colossus in her honor in 1903 . Until the renovation in 1986 it hung inside the base, since then it has been in the base in the Statue of Liberty Museum . It is complemented by a plaque that was donated in 1977 by the commemorative committee for Emma Lazarus and honors the life of the poet.

At the western end of the island is a group of five statues by the Maryland sculptor Phillip Ratner . They honor those people who are closely related to the creation of the Statue of Liberty. The Americans Pulitzer and Lazarus as well as the French Bartholdi, Laboulaye and Eiffel are shown.

In 1984, UNESCO declared the Statue of Liberty a World Heritage Site . In its declaration of importance, UNESCO describes the statue as a “ masterpiece of the human spirit [… that] endures as a highly potent symbol — inspiring contemplation, debate and protest — of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunity "(German:" Masterpiece of the human spirit [... which] is a lasting strong symbol for ideals such as freedom, peace, human rights, the abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunities and which stimulates reflection, debate and protest ") .

In 1985 the American Society of Civil Engineers added the Statue of Liberty to the list of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks .

mass and weight

With a height of 46.05 meters and a total height of 92.99 meters, the Statue of Liberty is currently (2011) at number 13 on the list of the tallest statues . It was the tallest when it was built and remained so until 1959 when it was surpassed by the statue of Cristo Rei in the Portuguese city of Almada .

| property | US | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Height of the copper statue | 151 feet 1 in | 46.05 meters |

| Foundation of the base (floor level) to the end of the torch | 305 feet 1 in | 92.99 meters |

| Heel to crown | 111 feet 1 in | 33.86 meters |

| Length of the hand | 16 feet 5 inches | 5.00 meters |

| index finger | 8 feet 1 in | 2.44 meters |

| Head from chin to skullcap | 17 feet 3 inches | 5.26 meters |

| Width of the head from ear to ear | 10 foot | 3.05 meters |

| Width of eyes | 2 feet 6 inches | 0.76 meters |

| Length of the nose | 4 feet 6 inches | 1.37 meters |

| Right arm length | 42 feet | 12.80 meters |

| Greatest thickness of the right arm | 12 feet | 3.66 meters |

| Width of the waist | 35 feet | 10.67 meters |

| Width of the mouth | 3 feet | 0.91 meters |

| Length of the board | 23 feet 7 inches | 7.19 meters |

| Width of the board | 13 feet 7 inches | 4.14 meters |

| Thickness of the board | 2 feet | 0.61 meters |

| Height of the base | 89 feet | 27.13 meters |

| Height of the base | 65 feet | 19.81 meters |

| Weight of copper | 60,000 pounds | 27.22 tons |

| Weight of steel | 250,000 pounds | 113.4 tons |

| Total weight of the statue | 450,000 pounds | 204.1 tons |

| Copper cladding thickness | 3/32 in | 2.4 millimeters |

Replicas

Due to the universal aura of the symbolism of the Statue of Liberty, numerous replicas in various sizes have been created over the years . The best-known version in France, the country of origin, is located in Paris at the western end of the Île aux Cygnes , a narrow artificial island in the Seine near the Eiffel Tower . This figure is actually not a replica, but the older sister of the New York lady. This 11.5 m high and 14 t heavy bronze statue is namely a cast of the plaster model on a scale of 1: 4 that Bartholdi had created in preparation for his main work. The cast of the model was given to France in Paris as Colonie Parisienne as a thank you to Americans and was inaugurated in Paris on July 4, 1889 on the anniversary of the United States' declaration of independence by President Sadi Carnot and the American Ambassador Whitelaw-Reid. The statue was finally erected in the virtual line of sight to its four times as high counterpart in New York harbor . There are two other, smaller replicas of the statue in the French capital; There are replicas in several other French cities, including since 2004 in Bartholdi's hometown Colmar . In addition, at the Pont de l'Alma in Paris is the Flamme de la Liberté (Flame of Liberty), a 3.5 m high replica of the flame of the Statue of Liberty made of gilded copper in natural size on a base made of gray and black marble. It was presented to the City of Paris in 1987 as thanks by the International Herald Tribune and various donors.

One of the oldest replicas in the United States was made around 1900, stood on the roof of the Liberty warehouse in Manhattan's Lower East Side for decades, and has been on display in front of the Brooklyn Museum since the 1960s . The replica in front of the New York-New York Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas , which opened in 1997, is half the height of the original.

As part of the patriotic campaign Strengthen the Arm of Liberty , the Boy Scouts of America donated around two hundred replicas to various American states and cities between 1949 and 1952. About half of these statues, around 2.5 meters high, have been preserved. The goddess of democracy , which was erected on Tiananmen Square during the 1989 protests , had certain similarities with the Statue of Liberty, but the builders made a conscious decision against an exact copy, as it would have been too pro-American.

In 1992, on the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America, the artist Hartmut Skerbisch erected a copy of the skeleton of the Statue of Liberty, identical in size and dimension, in front of the entrance to the Graz Opera as part of the Styrian Autumn . Only the torch was replaced by a sword, the tablet by a ball. The statue retained the working title lightsaber.

Cultural influence

The Statue of Liberty is highly recognizable and for many people is a symbol of the United States, similar to the Stars and Stripes or Uncle Sam . Heated controversies arise around this symbolism, which rarely affect the statue itself. Rather, the question is about the veracity of the symbolism, which is either confirmed with the " American Dream " and the openness of American society or rejected as hypocrisy. In the American media, the Statue of Liberty is considered the guardian of the values it symbolizes. She is the object of numerous caricatures around the world, but especially in her own country, in which she is shown with a different facial expression, different poses or with different objects in her hands.

The image of the Statue of Liberty adorns numerous American postage stamps and coins. It appeared on commemorative coins on the occasion of the centenary in 1986, on the American Platinum Eagle in 1997 , on the New York edition of the State Quarters in 2001 and since 2007 on the presidential dollar . The torch of the Statue of Liberty is shown twice on the current ten dollar bill. The Statue of Liberty is often used to advertise consumer goods such as Coca-Cola or chewing gum . Numerous institutions with a regional reference use her as a figure of identification. For example, from 1986 to 2000 it was featured on new New York State license plates . Team New York Liberty of the Women's National Basketball Association is not only named after the statue, but also includes it in their logo, with the flames of the torch resembling a basketball. The torch also features the New York University logo .

Numerous artists were inspired by the Statue of Liberty, for example Andy Warhol . As in other fields of art, the Statue of Liberty also represents opposing political views in music. Country singer Toby Keith sang them in the song Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American) , a passionate and patriotic commitment to the United States after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. This was compared to the album Bedtime for Democracy the punk band Dead Kennedys with a statue drawn in a parodic way on the cover a protest against the politics of the Reagan administration.

The Statue of Liberty is used as a backdrop in numerous films. An early example is The immigrants of Charlie Chaplin (1917). As a setting, the statue plays a role in the films Saboteurs by Alfred Hitchcock (1942), Ghostbusters II (1989), Remo - unarmed and dangerous (1985) and X-Men (2000), among others . In science fiction films , the damage or destruction of the statue is often a symbol of hopelessness or the end of civilization, for example in Independence Day (1996), The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and Cloverfield (2008). The film Planet of the Apes (1968), in which the surviving hero finds the ruins of the statue and realizes that he has landed on the earth of the future, which was destroyed by humans, is particularly formative for the genre . In 1979, Robert Holdstock wrote about the Statue of Liberty in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction :

“Where would [science fiction] be without the Statue of Liberty? For decades it has towered or crumbled above the wastelands of deserted [E] arth — giants have uprooted it, aliens have found it curious… the symbol of Liberty, of optimism, has become a symbol of science fiction's pessimistic view of the future. "

“Where would science fiction be without the Statue of Liberty? For decades it towered or crumbled over the wastelands of the deserted earth. Giants uprooted them, aliens found them strange ... the symbol of freedom, of optimism, became a symbol of the pessimistic view of the future of science fiction. "

Movie

- Mark Daniels (Director): Lady Liberty. Freedom illuminates the world. TV film documentary with scenes from the game, France, 2013. ( about the film ( Memento of February 23, 2014 on the Internet Archive ))

literature

- James B. Bell, Richard L. Adams: In Search of Liberty: The Story of the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island . Doubleday & Co., Garden City, NY 1984, ISBN 0-385-19624-5 .

- Jonathan Harris: A Statue for America: The First 100 Years of the Statue of Liberty . Four Winds Press, New York 1985, ISBN 0-02-742730-7 .

- Richard Seth Hayden, Thierry W. Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty . McGraw-Hill, New York 1986, ISBN 0-07-027326-X .

- Yasmin Sabina Khan: Enlightening the World: The Creation of the Statue of Liberty . Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY 2010, ISBN 978-0-8014-4851-5 .

- Barry Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia . Simon & Schuster, New York 2000, ISBN 0-7385-3689-X .

- Cara A. Sutherland: The Statue of Liberty . Barnes & Noble Books, New York 2003, ISBN 0-7607-3890-4 .

- Robert Belot, Daniel Bermond: Bartholdi . Editions Perrin, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-262-01991-6 .

Web links

- National Park Service: Statue of Liberty (official site; English)

- Statue-of-Liberty-Ellis Iceland Foundation (English)

- Photos about Statue of Liberty in the archives of the US Library of Congress (English)

- Statue of Liberty. In: Structurae

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Harris: A Statue for America. P. 7.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 7-8.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 60-61.

- ^ Statue of Liberty. Early History of Bedloe's Island. National Park Service, 2000, accessed February 13, 2011 .

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 102-103.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 39-40.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 16-17.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. P. 85.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 10-11.

- ^ A b John Bodnar: Monuments and Morals: The Nationalization of Civic Instruction . In: Civic and Moral Learning in America . Macmillan, New York 2006, ISBN 1-4039-7396-2 , pp. 212-214 .

- ^ Sutherland: The Statue of Liberty. Pp. 17-19.

- ↑ a b c d National Park Service (Ed.): National Register of Historic Places , 1966–1994: Cumulative List Through January 1, 1994 . National Park Service, Washington DC 1994, ISBN 0-89133-254-5 , pp. 502 .

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 96-97.

- ↑ a b Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 105-108.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 52-53, 55, 87.

- ↑ Ruth Brandon: A capitalist romance: Singer and the sewing machine . Lippincott, Philadelphia 1977, ISBN 0-397-01196-2 , pp. 211 .

- ^ Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi: The Statue of Liberty enlightening the world. North American Review, Boston 1885. p. 42.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 108-111.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 118, 120, 125.

- ↑ a b Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 44-45.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 123-125.

- ↑ a b c Khan: Enlightening the World. P. 137.

- ↑ Sometimes truth is found in a pure copper ore. norway.org, 1999, accessed February 7, 2011 .

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 126-128.

- ↑ Bell, Adams: In Search of Liberty. Pp. 25-26

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. P. 130.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 49.

- ↑ a b Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 134-135.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 94.

- ↑ Bell, Adams: In Search of Liberty. P. 32

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 136-137.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 138-143.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 30.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. P. 144.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 32-34.

- ^ Statue of Liberty Timeline. Public Broadcasting Service , 2002, accessed February 8, 2011 .

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 36-39.

- ↑ Bell, Adams: In Search of Liberty. Pp. 37-38

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 159-163.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 91.

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. P. 169.

- ^ A b Louis Auchincloss : Liberty: Building on the Past. New York Magazine, May 12, 1986, accessed February 10, 2011 .

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Belot, Bermond: Bartholdi. P. 348.

- ^ Sutherland: The Statue of Liberty. Pp. 49-50.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 184-186.

- ↑ Foundation for the Statue of Liberty. Wiesbadener Tagblatt , May 5, 2010, archived from the original on July 29, 2013 ; Retrieved February 11, 2011 .

- ^ Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 163-164.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 172-175.

- ^ Benjamin Levine, Isabelle F. Story: Statue of Liberty. Liberty State Park, 1961, accessed February 10, 2011 .

- ↑ Bell, Adams: In Search of Liberty. Pp. 40-41

- ^ National Park Service : Creating the Statue of Liberty 1865–1886

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 110-114.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 64.

- ↑ Hayden, Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty. P. 36.

- ↑ a b c Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 133-134.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 65.

- ↑ a b Khan: Enlightening the World. Pp. 176-178.

- ↑ Bell, Adams: In Search of Liberty. P. 52.

- ↑ a b Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 127-128.

- ↑ a b Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 71.

- ↑ Postponing Bartholdi's Statue Until There is Liberty for Colored as well. The Cleveland Gazette, November 27, 1886, SS 2 , accessed February 11, 2011 .

- ↑ a b c Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 41.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 24.

- ^ Sutherland: The Statue of Liberty. P. 78.

- ^ To paint Miss Liberty. (PDF) The New York Times, July 19, 1906, accessed February 1, 2011 .

- ↑ How shall “Miss Liberty's” toilet be made? (PDF) The New York Times, July 29, 1906, accessed February 1, 2011 .

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 168.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 136-139.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia . Pp. 148-151.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 147.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 136.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 202.

- ↑ a b Harris: A Statue for America. P. 169.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 141-143.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 147-148.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia . P. 19.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 20.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 143.

- ↑ a b Harris: A Statue for America. Pp. 169-171.

- ↑ Hayden, Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty. P. 38.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 204-205, 216-218.

- ↑ Jocelyne Daw: Cause Marketing for Nonprofits: Partner for Purpose, Passion, and Profits . John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey 2006, ISBN 0-471-71750-9 , pp. 4 .

- ^ A b c Hayden, Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty. Pp. 74-81.

- ↑ Hayden, Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty. P. 153.

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. P. 153.

- ↑ Hayden, Despont: Restoring the Statue of Liberty. Pp. 71, 84, 88.

- ^ Sutherland: The Statue of Liberty. P. 106.

- ^ Statue of Liberty: History & Culture. National Park Service, 2009, accessed February 1, 2011 .

- ^ Statue of Liberty's Crown Will Reopen July 4. The New York Times, May 8, 2009, accessed February 1, 2011 .

- ↑ National Park Service: Statue of Liberty National Monument - Liberty Island to Remain Open During Year-Long Renovation , press release of August 10, 2011

- ↑ Statue of Liberty reopens as nation celebrates Fourth of July

- ^ Circle Line Loses Pact for Ferries to Liberty Island. New York Times, June 29, 2007; accessed February 13, 2011 .

- ↑ a b Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 222-223.

- ^ Harris: A Statue for America. P. 163.

- ↑ Entry on the website of the UNESCO World Heritage Center ( English and French ).

- ↑ Statistics. Statue of Libert. National Park Service, August 16, 2006, accessed February 12, 2011 .

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 200-201.

- ↑ La statue de la liberté in Colmar. Colmar City Council, archived from the original on May 15, 2012 ; Retrieved February 17, 2011 (French).

- ^ Moreno: The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. Pp. 200-201

- ^ Replica of the Statue of Liberty, from Liberty Storage & Warehouse. Brooklyn Museum, accessed February 15, 2011 .

- ^ New York-New York, It's a Las Vegas Town. The New York Times, January 15, 1997, accessed February 15, 2011 .

- ↑ Little Sisters of Liberty. Scouting Magazine, October 2007, accessed February 15, 2011 .

- ^ Tsao Tsing-yuan, Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, Elizabeth J. Perry: The Birth of the Goddess of Democracy . In: Popular Protest and Political Culture in Modern China . Westview Press, Boulder 1994, pp. 140-147 .

- ↑ Statue lightsaber

- ^ Statue of Liberty cartoons and comics. Cartoon stick, accessed February 15, 2011 .

- ^ State License Plates to Get New Look. New York Times, January 11, 2000, accessed February 21, 2011 .

- ↑ Belot, Bermond: Bartholdi. P. 409.

- ↑ Eric Greene, Richard Slotkin: Planet of the apes as American myth: Race, politics, and popular culture . Wesleyan University Press, Middletown (Connecticut) 1998, ISBN 0-8195-6329-3 , pp. 52 .

- ↑ Peter Nicholls : The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction . Granada Publishing Ltd., St Albans 1979, ISBN 0-586-05380-8 , pp. 14 .

Remarks

- ↑ According to an agreement between the states of New York and New Jersey of 1934, which determined the center of the bay as the border between the two states, the island still belongs to the territory of New York, although it is closer to New Jersey. Parts of the land created by reclamation, however, are New Jersey territory. New Jersey v. New York 523 US 767. United States Supreme Court , 1998, accessed February 13, 2011 .

Coordinates: 40 ° 41 ′ 21.2 " N , 74 ° 2 ′ 40.1" W.