German Peasants' War

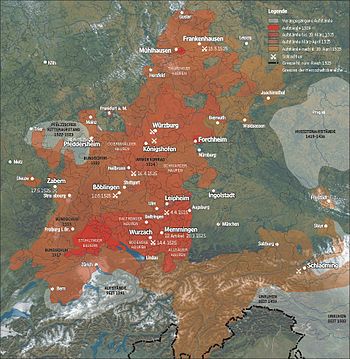

The German Peasants' War (or revolution of the common man ) refers to the totality of the uprisings of peasants, townspeople and miners, which broke out in 1524 for economic and religious reasons in large parts of southern Germany , Thuringia , Austria and Switzerland and in the course of which the peasants with the Twelve articles from Memmingen for the first time made demands that are considered to be the early formulation of human rights. In Swabia , Franconia , Alsace and Thuringia, the uprisings in 1525, in the Electorate of Saxony and Tyrol in 1526, were suppressed by landlords and sovereigns, with an estimated 70,000 to 75,000 people killed. The Peasants' War was preceded by uprisings in Livonia , Hungary ( Dózsa uprising ), England and Switzerland.

Definition of terms

The events of 1525 were already referred to by contemporaries as the "peasant war". But the term was rarely used by the insurgents themselves. In 1795, the historian Georg Friedrich Sartorius began the series of monographs that began with the title Attempt at a History of the German Peasant War . With the extremely successful work History of the Great Peasants' War , written by the historian Wilhelm Zimmermann and published from 1841–1843, the events from 1524 to 26 finally became a purely German matter, the main actors of which were the peasants, whose actions were a war against the she was called oppressive authorities. The events in the Alpine countries of Switzerland and Austria are only dealt with in passing in Zimmermann's work. All other historians who dealt with the surveys from 1524 to 1526 followed this pattern, so that the term “(German) peasant war” became more and more solid.

The social uprising, which is still commonly referred to today as the German Peasant War , was by no means restricted to the peasants alone. Peter Blickle tried to do justice to the now proven participation of townspeople and miners in this social survey by using the term “revolution of the common man”, referring to the “common man” as the subjects incapable of rule (“... the common man is the farmer , the citizen of the rural city, the townspeople excluded from imperial city offices, the miners ... ”) who was in opposition to the authorities. The term presented in 1975 was initially criticized in East and West because of its ambiguous source base. In the meantime, Blickle's thesis of the “revolution of the common man” or the “revolution of 1525” has been widely accepted.

prehistory

The Peasants' War from 1524 to 1526 did not suddenly break out over the German territories. Rather, it belongs to a long series of European uprisings and resistance actions that stretched from the late Middle Ages to modern times. As early as the 13th and 14th centuries, farmers had risen in Switzerland, Flanders and England, and in the 15th century in Bohemia. In the southern Harz and the Golden Aue , the Flegler rose from 1412 to 1415 . In Switzerland the peasants rose against the cities of Zurich and St. Gallen in 1489, and against Lucerne, Bern and Solothurn in 1513/14. Then the " Bundschuh " was formed (1460 in Hegau, 1493 in Alsace, 1502 in the Diocese of Speyer , 1513 in Breisgau and 1517 on the Upper Rhine). In the diocese of Würzburg there were riots in 1476 in the wake of the Pauker von Niklashausen . In Upper Swabia, the landlords' access provoked actions against the Prince Abbey of Kempten (1491/92) and the Ochsenhausen Abbey (1502). In 1514, the poor Konrad rose in Württemberg .

The numerous civic surveys, especially in southwest German cities between 1509 and 1514, were mostly carried out by the poor and underprivileged classes and directed against the economic and political privileges of the patricians and the clergy .

The aristocracy was not interested in changing the living conditions of the farmers, because this would inevitably limit their own privileges and advantages. The lower nobility went towards decline and had to struggle with a dramatic loss of power, which led to their own uprisings ( Palatinate Knight Uprising ). The attempt of many lower nobles to stay afloat through robber barons was largely at the expense of the peasants.

The clergy were just as against any change: Catholicism as it existed at that time was the core pillar of feudalism ; the ecclesiastical institutions were usually organized in a feudal manner - hardly any monastery existed without associated villages. The church received its income mainly from donations, indulgences and tithing . The latter was also an important source of finance for the nobility.

The only reform efforts aimed at the abolition of the old feudal structures within the cities came from the strengthening bourgeoisie in the cities, but remained weak, as this too was dependent on the nobility and clergy.

Causes and environment

The individual scenes of the Peasants' War from 1524 to 1526 include the Upper Rhine region, Württemberg, Upper Swabia, Franconia, Thuringia, Rhineland, Tyrol and Salzburg. Unrest also broke out in numerous cities (Frankfurt am Main with the Frankfurt guild uprising , Nuremberg, Mühlhausen, Würzburg). Local ties were more the rule than the exception. Most of the uprisings took place within their own territorial borders. Determining the causes of the rural unrest is difficult due to the time and regional differences. Often several reasons were decisive: economic hardship and social misery, difficulties in obtaining justice from landlords, personal lords and judges, and last but not least, grievances in the nobility and clergy.

The peasants bore the brunt of maintaining feudal society: princes , nobility, civil servants , patricians and the clergy lived on their labor, and as the number of beneficiaries continued to rise, the taxes the peasants had to pay also rose. In addition to the big tithe and the small tithe on most of their earned income and earnings, they paid taxes , duties and interest and were often obliged to their landlords to perform compulsory and tension services . In addition, the real division was used in Upper Swabia , Württemberg , Franconia, Saxony (Upper Saxony) and Thuringia , which led to ever smaller farms while the total production area remained the same. Many of these small farms could no longer be run economically in view of the high loads.

Economic problems, frequent bad harvests and the great pressure of the landlords led more and more peasants into bondage and further into serfdom , which in turn resulted in additional rents and service obligations.

The "old law", an orally transmitted law, was increasingly freely interpreted or completely ignored by the landlords. Existing for centuries commons were expropriated and community pasture, Holzschlag-, fishing or hunting rights curtailed or abolished.

Many of the simple peasants did not dare to rebel against their masters due to their multiple dependencies. Above all, the rural upper class wanted changes. Mayors , peasant judges, village craftsmen and farmers from the small towns carried the uprising and in many places pushed the poor peasants to join the peasantry.

Above all, the farmers themselves wanted to restore their ancestral rights and lead a humane and, moreover, God-fearing life. However, their demands for the alleviation of burdens and the abolition of serfdom shook the foundations of the existing social order.

Relation to the Reformation

There were considerable abuses in the church. Many clergymen led dissolute lives and profited from foundations and legacies of the rich population as well as taxes and donations from the poor. In Rome one attained office and dignity through nepotism and bribery ; the popes distinguished themselves as warlords and builders as well as promoters of the fine arts .

These conditions were criticized early on by Hans Böhm (the "Pfeifer von Niklashausen ") in Tauberfranken , Girolamo Savonarola in Florence and later by Martin Luther . When the Dominican Johann Tetzel traveled through Germany in 1517 on behalf of the Archbishop of Mainz, Albrecht von Brandenburg and Pope Leo X. , successfully preaching indulgences there and selling his indulgence slips, Luther wrote his 95 theses . Nailed to the church door in Wittenberg on October 1517 .

Also Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich and Thomas Müntzer in Allstedt argued publicly that everyone could find its way to God and his salvation without the mediation of the hierarchical Church. In doing so, they undermined the Catholic Church's claim to absoluteness and confirmed to the farmers how far the clergy had distanced themselves from their own teachings and were therefore largely superfluous.

Luther's argument in his book Von der Freiheit einer Christenmenschen (1520), that a Christian […] is lord over all things and not subject to anyone , as well as his translation of the New Testament into German in 1522 were further decisive triggers for the revolt of the village population : Now it was also possible for ordinary people to question the claims of the nobility and clergy that were justified by the “will of God”. They found no biblical justification for their own miserable situation “farms dismembered by the division of inheritance”, and thus many farmers suspected that the restriction of the old law by the landlords contradicted actual divine law .

Martin Luther

Although the standpoints of the Reformation were an essential justification for the rebellious peasants, Martin Luther clearly distanced himself from the peasant war. As early as 1521 he made a clear distinction between the worldly and the spiritual area, since with the Reformation he wanted to change the church and not - in contrast to Savonarola - change the worldly order. In spite of this, the authorities increasingly made him responsible for the events of the Peasants' War, probably also because he did not clearly distance himself from the demands of the peasants. As late as 1525, Luther criticized the “haughty” behavior of the princes in his admonition to make peace . Only after the bloodshed in Weinsberg did he clearly take the side of the princes and sharply condemn the rebels:

"Against the murderous and predatory packs of the peasants [...] they should be thrown, choked, stabbed, secretly and publicly, whoever can, how one has to kill a great dog."

Luther only published his work, Against the Mordian and Reubian Rotten der Bawren , at a time when the defeat of the peasants was already foreseeable.

After 1525, Protestantism lost its revolutionary spirit and, supported by Luther, cemented the prevailing social conditions with the belief “Be subject to the authorities”.

Philipp Melanchthon

On May 18, 1525, the Elector Ludwig V of the Palatinate wrote a letter to the Protestant reformer Philipp Melanchthon in Wittenberg with the request that u. a. to judge the behavior of farmers. Melanchthon wrote in his reply:

"[...] that this is a wild, naughty peasant people and that the authorities are right. In addition, tithe is right, serfdom and interest are not outrageous. The authorities can set the punishment according to the need in the country and the peasants do not have the right to dictate a law to the rulers. For such a naughty, wanton and bloodthirsty people God calls the sword. "

This answer released the elector from all agreements (treaty of Udenheim and Hilsbach ). He equipped a force and on May 22, 1525, with 4,500 soldiers, 1,800 horsemen and several guns, he marched from Heidelberg to Bruchsal, where he victoriously entered on May 23, 1525.

Thomas Müntzer

Thomas Müntzer was a former supporter of Luther. In contrast to this he stood for the violent liberation of the peasants and was active in Mühlhausen , where he was pastor in the Marienkirche , as an agitator and promoter of the uprisings.

There he tried to implement his ideas of a just social order: privileges were abolished, monasteries dissolved, rooms created for the homeless , and a feeder set up. He called for the "community of all goods, the equal obligation of all to work and the abolition of all authorities" (omnia sunt communia). However, his efforts to unite various Thuringian peasant groups did not succeed. In May 1525 he was captured, tortured and finally executed.

course

Outbreak of conflicts

The first uprising in the Peasants' War took place on June 23, 1524 in the Wutach Valley near Stühlingen . It was directed against Count Sigmund II of Lupfen, who ruled Hohenlupfen Castle . The farmers formed a flag in the St. Blasien area and elected Hans Müller von Bulgenbach as their leader . In 1524 riots broke out again at Forchheim near Nuremberg , and shortly afterwards in Mühlhausen near Erfurt . On October 2nd, 1524, the farmers allied themselves in western Hegau . A little later, 3,500 farmers moved towards Furtwangen . In Upper Swabia around Lake Constance, it had been fermenting for a long time and within a short time, three armed so-called peasant heaps formed in February and March 1525: the Baltringer Haufen , the Seehaufen and the Allgäuer Haufen . The largest of the three was the Baltringer Haufen: more than 12,000 farmers, citizens and clergy gathered in the Baltringer Ried near Biberach within a few days . The sea heap near Lindau also consisted of approximately 12,000 men, including many simple clergymen and mercenaries . The 7,000 Allgäu farmers, who mainly revolted against the Prince Abbot of Kempten , camped near Leubas .

Twelve articles and negotiations

The three Upper Swabian peasant groups wanted above all to improve their living conditions and not start a war. That is why they rely on negotiations with the Swabian Federation . 50 representatives of the three peasant groups met in the free imperial city of Memmingen , whose citizens sympathized with the farmers. Here the leaders of all three groups tried to articulate the demands of the peasants and to back them up with the Bible. In February / March 1525 the twelve articles were written, the authorship of which was usually assigned to Sebastian Lotzer and Christoph Schappeler , a furrier journeyman and a preacher in Memmingen. According to Peter Blickle , the Twelve Articles were "letter of appeal, reform program and political manifesto" at the same time. Following the example of the Swiss Confederation , the farmers founded the Upper Swabian Confederation , the principles of which were laid down in federal regulations . In contrast to previous surveys, the individual peasant groups should also stand up for one another in the future. Within a very short time, large editions of both publications were printed and distributed, which ensured that the uprisings spread exceptionally quickly throughout southern Germany and Tyrol . The founding of the Christian Association was announced to the Swabian Federation in Augsburg after the two papers had been adopted, in the hope of being able to participate in negotiations as an equal partner. In view of various looting and the Weinsberg bloody act (see below), however, the nobles united in the Swabian Federation had no interest in negotiations. Supported by the Augsburg merchant family Fugger , Georg Truchsess von Waldburg-Zeil (called Bauernjörg) was commissioned with an army of 9,000 mercenaries and 1,500 armored horsemen to overthrow the peasants, mostly armed with scythes and flails .

The negotiation of the Twelve Articles in Memmingen was the linchpin of the Peasant War: Here the demands were formulated uniformly for the first time and set down in writing. For the first time, the peasants appeared uniformly towards the authorities - the previous surveys failed mainly because of the fragmentation of the uprisings and the lack of mutual support. This changed with the “ 12 Articles ”.

The Twelve Articles called for the free election of pastors (1), the abolition of the small tithe, ecclesiastical or charitable use of the large tithe (2), the abolition of serfdom (3), free hunting and fishing (4), the return of forests (5) , the reduction of compulsory labor (6), compliance with existing ownership conditions (7), redefinition of the taxes to the landlord (8), fixed instead of arbitrary penalties (9). Return of the commons (10). Abolition of death (11). The twelfth article takes up the idea of the preamble and declares the general willingness to renounce all demands that are not in accordance with the word of God.

Course of the uprising

At the end of March 1525, the Waldburg-Zeil army gathered in Ulm . A little further down the Danube near Leipheim , 5,000 farmers had gathered around the preacher Jakob Wehe and plundered monasteries and aristocratic residences in the wider area. The army of the Swabian Confederation therefore marched to Leipheim and on the way there destroyed individual pillaging groups of farmers. On April 4, 1525 there was the first great battle near Leipheim, in which the Leipheimer band was defeated. The city of Leipheim had to pay a fine; Woe and the other leaders of the crowd were executed. As a memorial, a peasant war memorial was erected above the Biberhackens west of Leipheim on the edge of the corridor to Echlishausen on the B10 .

Also at the beginning of April the farmers from the Neckar valley and the Odenwald gathered under Jäcklein Rohrbach . At Easter 1525 (April 16) the Neckartaler Haufen camped near Weinsberg , where the hot-headed Rohrbach let the Count Ludwig von Helfenstein and his knights run the gauntlet , who were hated by the farmers . The painful death of the nobles by stabbing and beating the peasants went down in the history of the Peasants' War as the Weinsberg bloodshed . It decisively shaped the image of the murdering and plundering peasants and was one of the main reasons why many nobles opposed the cause of the peasants. As a punishment, the city of Weinsberg was burned down and Jäcklein Rohrbach was burned alive. After the bloody deed of Weinsberg, the Neckartaler and Odenwälder merged with the Taubertaler Haufen ( Black Heap ) led by the Franconian nobleman Florian Geyer to form the strong Heller Lichter Haufen . The nearly 12,000 men turned against the bishops of Mainz and Würzburg and the prince-elector of the Palatinate under the leadership of Captain Götz von Berlichingen .

On April 12th, the armed forces of the Swabian Federation put the Baltringer heap , which could be quickly defeated. The farmers were disarmed and everyone had to pay a heavy fine.

On April 13th, Truchsess Georg von Waldburg and his army had to retreat in front of the militarily well-trained sea pile and one day later, on April 14th, near Wurzach, she met the farmers of the Allgäu region . He negotiated with them and was able to convince them to lay down their arms. In the Weingarten contract of April 17, he made concessions to the Seehaufen and the Allgäuer Haufen with the strategist Eitelhans Ziegelmüller and guaranteed them free withdrawal and an independent arbitral tribunal to settle their conflicts.

On April 16, the Württemberg farmers gathered. The 8,000-strong troop moved into the city of Stuttgart and moved on to Böblingen in May .

Even with Hall and Gmünd , smaller pile formed, the 3,000 followers ransacked the monasteries Lorch and Murrhardt and laid Hohenstaufen Castle in ruins. Monasteries were also plundered and castles burned down in Kraichgau and Ortenau .

After the success of Weingarten, the Waldburg-Zeil army moved into the Neckar Valley. The peasants were defeated at Balingen , Rottenburg , Herrenberg and on May 12th in the Battle of Böblingen despite the large majority. Leader Matern Feuerbacher then fled south. The same thing happened on June 2nd for the Neckar Valley and Odenwäldern near Königshofen .

In April 1525, the representatives of ten Blackburg congregations that had formed the Evangelical Brotherhood met in Gehren and Langewiesen . They called on the rest of the county by letters and envoys to join the union and to join the demands of the farmers of the forest heap gathered in Gehren . On April 23, 1525, the forest heap moved over Königsee and Paulinzella , where the farmers plundered the office and monastery , to Stadtilm . On April 24, 1525, the citizens of Stadtilm deposed the council and steward of the Count of Schwarzburg and opened the city gates to the rebellious peasants. The news of this victory spread quickly in the Rudolstadt area , whereupon more farmers from the Schwarzburg suzerainty came to Stadtilm and joined the forest heap . The unified Schwarzburg peasantry from Gehren and Stadtilm moved to the gates of Arnstadt and presented their peasant and urban demands , which were summarized in twelve articles , to the count . In view of the armed forces of the peasantry, which had grown to 8,000 men, the count recognized the Twelve Articles , whereupon the farmers' captains arranged for the peasantry to be withdrawn and for the time being dissolved. After the defeat of the peasants near Frankenhausen , Elector Johann the Steadfast withdrew the commitments to the peasants and townspeople. Arnstadt received a severe fine and lost his privileges. The leaders of the unified Schwarzburg peasantry were captured and executed in Arnstadt on June 17 and August 9, 1525.

The Battle of Frankenhausen on May 15, 1525 was one of the most important battles during the German Peasants' War. In it, the rebellious peasants of Thuringia led by Müntzer were completely defeated by an army of princes. Müntzer himself was captured and beheaded on May 27th in Mühlhausen after he had been brought to the Heldrungen fortress and tortured .

On May 23, a bunch of 18,000 farmers from Breisgau and southern Black Forest took Freiburg im Breisgau . After the success, the leader Hans Müller wanted to rush to the aid of the besiegers of Radolfzell , but only a few peasants moved with him; most of them wanted to take care of their fields again. Their forces were relatively small when they were defeated by Archduke Ferdinand of Austria shortly afterwards. On June 4, Waldburg-Zeil met the Hellen Lichten Haufen of Franconian farmers near Würzburg , and since Götz von Berlichingen left it the day before under a pretext, the leaderless farmers had no chance. 8,000 farmers were killed in two hours.

After this victory, the Bauernjörg troops turned south again and defeated the last rebels in the Allgäu at the end of July. In four months, Georg Truchsess von Waldburg-Zeil's army had covered more than 1,000 km.

Other uprisings were also suppressed. On June 3, 1525 the Bildhäuser Haufen was defeated together with the rebels from Meiningen in the battle between Meiningen and Drei 30acker by a united armed force of the princes under the leadership of Elector Johann von Sachsen on 23/24. June 1525 in the battle of Pfeddersheim the rebels in the Palatinate Peasants' War were crushed. By September 1525, all skirmishes and punitive actions were over. Emperor Charles V and Pope Clemens VII thanked the Swabian Federation for its intervention.

The Werra heap , which operated in Thuringia in April and May 1525, disbanded after Count Wilhelm IV of Henneberg-Schleusingen had signed the Twelve Articles; its leaders were captured and executed.

consequences

Individual farmers' associations like that of the Tyrolean Michael Gaismair kept secret for a few years. A number of outlawed farmers lived for decades as bands of robbers in the forests. But there were no more major uprisings. In the following 300 years the farmers hardly revolted. In the period that followed, the possibility of subject trials , which opened up legal recourse to the imperial courts for peasants and citizens , also contributed to this. This gave them an instrument for peaceful conflict resolution with which arbitrary acts of authority could be restricted.

When it comes to the number of deaths verifiably related to the Peasants' War, the sources do not always contain consistent information. Research in 1975 put the earlier assumption that there was a demographic slump as a result of the peasant war. In the uprising areas, the loss due to the direct consequences of the Peasants' War was 2.5 to 3.0 percent of the total population. The death toll is put at between 70,000 and 75,000. In relation to the entire empire, this would have been 0.5 percent of the population at that time.

The surviving rebels automatically fell into imperial ban and lost all rights and privileges and were therefore outlawed . The leaders were punished with death. Participants and supporters of the uprisings had to fear the criminal courts of the sovereigns, which were only just beginning and some of them were very cruel. Many reports speak of beheadings, eye stabbing, chopping off fingers and other abuse. Those who got away with a fine were still lucky, even if many farmers could not pay the fines because of the high taxes. Entire communities were deprived of their rights because they supported the farmers. In some cases the jurisdiction was lost, festivals were banned and city fortifications razed. All weapons had to be surrendered, and village inns were no longer allowed to be visited in the evenings.

The consequences for numerous castles and monasteries were devastating. A total of around 1000 were partially or completely destroyed in 1524/1525. In the Bamberg region alone, almost 200 castles were destroyed or damaged in just 10 days in mid-May. In Thuringia, Halberstadt and Wernigerode alone, there were around 300 destroyed monasteries. In contrast to most of the monasteries, many castles were not rebuilt but fell into disrepair. The high time of the castles was over, instead castles and fortresses were built. Therefore, the Peasants' War is considered to be one of the most lasting waves of destruction of German castles, which is also a significant loss for today's castle research and, not least, changed the landscape of the regions affected.

In a few regions the peasants' war had positive effects. In some areas, grievances were remedied by treaties if the rebels had rebelled due to particularly bad circumstances (e.g. those of the prince monastery of Kempten , for which the Memmingen treaty was concluded at the Reichstag in Speyer in 1526 ). The conditions of the peasants had also become more manageable in many places because they no longer had to pay their taxes solely to the landlords , but also directly to the princes .

The defeats of the peasants laid the foundation for the wealth growth of the victorious aristocratic military leaders. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg-Zeil acquired lands in Upper Swabia. Field captain Sebastian Schertlin von Burtenbach held himself harmless to the defeated in order to pay the soldiers he had hired.

The Reformation Anabaptist movement, which was established in 1525, was connected to the rebellious peasants primarily through its anti-clericalism and its rejection of serfdom. Both movements were clearly in opposition to the clergy. In many places, such as under the leadership of Johannes Brötli in Hallau , Switzerland , there was a merger. Anabaptists also took part in peasant uprisings in Saxony, Franconia and Thuringia. Hans Römer , the leader of the Thuringian Anabaptists, preached before the assembly of the Bildhäuser Haufen. In Waldshut , Balthasar Hubmaier wrote the so-called article letter based on the twelve articles . However, according to the Schleitheim articles from 1527, the majority of Anabaptists followed a nonviolent path that is still characteristic of Mennonites and Hutterites today.

Research history

The chronicler Lorenz Fries described the events in the territory of the Würzburg prince-bishops in his work The History of the Peasants' War in East Franconia . In historiography, however, interest in the events of 1525 soon died out. The chronicles of the post-Reformation period only offered some poor information. The memory of the Peasants' War was kept alive in the controversial literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. The peasant war was long considered an embarrassing misstep of the Protestants, which the Catholics held against them. In 1795, the historian Georg Friedrich Sartorius began the series of monographs that began with the title Attempt on a History of the German Peasants' War and brought it close to the French Revolution . The peasant war was thus offset between tyranny and freedom. Leopold von Ranke described it as "the greatest natural event of the German state", in that elementary popular forces disrupted the meaningful course of the Reformation. Wilhelm Zimmermann wrote the three-volume historical work "General History of the Great Peasants' War" between 1841 and 1843. For Zimmermann, the Peasants' War was “a struggle of freedom against inhuman oppression, of light against darkness”. For the theologian, radical democrat and later left-wing member of the Paulskirche there were clear parallels between the struggle of the peasants of 1525 and the current struggle for freedom and democracy. For Friedrich Engels it was “the greatest attempt at revolution by the German people”. For Engels, the Thuringian uprising was the climax of the German peasant war. This was due to the work of Thomas Müntzer, whose program articulates the "anti-feudal" insurrection goals most clearly and who was most likely to understand how to integrate different "anti-feudal" forces into his movement. Karl Marx apostrophized it as “the most radical fact in German history”. Marx saw in the Peasants' War the consequent uprising of an oppressed people in the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

In 1933 Günther Franz published a detailed account of the course of the Peasant War on the basis of his own archive studies and with knowledge of all local and regional historical literature. Franz saw the Peasants' War as a political conflict between the territorial rulers who were pushing for sovereignty and the rural communities struggling to maintain their autonomy. In the 1970s, Franz reaffirmed his position "that the peasant war was not started primarily for economic or religious reasons". Rather, he saw the cause in the territorial state. Franz's extensive work shaped peasant war research for decades. A scientific rethinking began in the 1960s, first in the GDR and later in the Federal Republic.

For the Marxist view of history in the GDR , the Peasants' War was extremely important and was one of the central subjects of historical research in the GDR. According to this picture, history was the regular sequence of social formations. With reference to Friedrich Engels, the concept of an "early bourgeois revolution" was developed in the GDR from 1476 to 1525, which combined the peasant war and the Reformation into one movement. West German research took offense, among other things, at the "bourgeois revolution" without citizens, but only dealt with the concept belatedly. Research experienced a sustained upswing in 1975 with the 450th anniversary of the German Peasant War. Almost 500 titles were written in one year. In 1975, Peter Blickle published in his book The Revolution of 1525, the only monograph on the peasant war aimed at the whole problem. For Blickle, the uprising was more than a peasant war, it was a revolution. The carrier was not only the peasant, but the "common man", that is, the entire non-privileged population (peasants, citizens of the country towns and citizens of the imperial towns who are not able to advise, miners).

reception

In 1525 Albrecht Dürer designed a memorial column to commemorate the beaten peasants. In Mainz, however, Archbishop Albrecht von Brandenburg donated a market fountain in 1526, which commemorates the victory of the imperial mercenaries at Pavia and the overthrow of the "common man". In the last decades of the 20th century, the peasant war theme was still artistically processed. In 1989 the Panorama Museum opened on the Schlachtberg near the small town of Bad Frankenhausen in Thuringia with the monumental painting “Early Bourgeois Revolution in Germany” by the Leipzig painter Werner Tübke . The Mühlhausen Peasant War Spectacle , a history game with a medieval market, focuses on the sections of the biography of the reformer Thomas Müntzer that are relevant for Mühlhausen and thus an excerpt from the history of the German Peasants' War. Ten cities with eleven museums belong to the working group of the German Peasant War Museums. In the Zinnfigurenklause in the Freiburg Schwabentor u. a. Depicted scenes from the war in the Black Forest.

Fiction (selection)

- Walter Laufenberg : Pride and Storm - A Lake Constance novel about the time of the peasant wars. Publishing house for regional culture, Heidelberg, Ubstadt-Weiher 2005, ISBN 3-89735-448-9 .

- Gerhart Hauptmann's drama Florian Geyer. The tragedy of the Peasant War in five acts, with a prelude. (1896) deals with the events of the German Peasant War.

- Mathis der Maler , opera (about the life of the painter Matthias Grünewald against the backdrop of the German Peasant War), libretto and composition by Paul Hindemith , premiered in Zurich 1938

- The peasant opera. 1973, scenes from the German Peasants' War (1525) by Yaak Karsunke and Peter Janssens

- Luther Blissett: Q (1999) - a novel about peasant wars, Thomas Müntzer and the Anabaptist movement

- Ludwig Ganghofer : The new being (1902) - novel about Joß Fritz and the persecution of Protestants in the Berchtesgadener Land.

- Manfred Eichhorn : The fire of Frankenhofen . Klemm & Oelschlaeger, Ulm 2014, ISBN 978-3-86281-069-7 .

swell

- Günther Franz (Hrsg.): Sources on the history of the peasant war. (= Selected sources on German history in modern times - Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gedächtnisausgabe. Vol. 2). New edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1963.

literature

- Peter Blickle : The Bauernjörg. General in the Peasants' War. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-67501-0 .

- Peter Blickle: The Peasants' War. The revolution of the common man (= Beck'sche series - CH Beck Wissen vol. 2103). 4th, updated and revised edition, CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-43313-9 .

- Peter Blickle: The Revolution of 1525. 4th revised and bibliographically expanded edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-486-44264-3 .

- Peter Blickle (Ed.): Revolt and Revolution in Europe. Lectures and minutes of the international symposium commemorating the peasant war in 1525 (Memmingen, March 24-27, 1975) (= historical journal. Supplement. New series, vol. 4). Oldenbourg, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-486-44331-3 .

- Horst Buszello , Peter Blickle, Rudolf Endres (eds.): The German Peasants' War (= UTB Bd. 1275). 3rd bibliographically supplemented edition. Schöningh, Paderborn et al. 1995, ISBN 3-8252-1275-0 .

- Günther Franz : The German Peasants' War. 12th, compared to the 11th unchanged edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1984, ISBN 3-534-00202-4 .

- Benjamin Heidenreich: An event without a name? On the ideas of the “peasant war” of 1525 in the writings of the “insurgents” and in contemporary historiography . De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-11-060130-5 .

- Günter Vogler (Ed.): Peasants' War between Harz and Thuringian Forest (= historical communications. Supplements 69). Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-515-09175-6 .

- Rainer Wohlfeil : The Peasants' War 1524–26. Peasants' War and Reformation. Nine contributions (= Nymphenburg texts on science. Vol. 21). Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-485-03221-2 .

- Wilhelm Zimmermann : The great German peasant war. Köhler, Stuttgart 1841-1843; Dietz, Stuttgart 1891; Dietz, Berlin 1952; deb, Berlin 1980 and 1982 (7th edition ISBN 3-920303-26-1 ); Berlin 1993 ISBN 3-320-01829-9 .

Web links

- Overview of the German Peasants' War on historicum.net

- Literature on the German Peasant War in the catalog of the German National Library

- The Peasants' War of 1524/1525 in southwest Germany

- The German Peasants' War (1524/1525) ( Memento from April 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Kirchberg an der Jagst - Fate of a Hohenlohe-Franconian City Volume I based on the manuscript bequest of Judge-Martial Theodor Sandel at webisphere.de (1936)

- Ulrich Poprawka: Teaching material on the subject of the peasant war, status 2000 (PDF file; 25 kB)

- Hans Holger Lorenz: Notes on Peasant Wars (extensive collection)

- Hans von Rütte: Peasants' War (1525). In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Association of German Peasant War Museums

- Friedrich Engels: The German Peasants' War (1850)

- Lorenz Fries: The history of the peasant war in East Franconia , 2 vol., Wirzburg [Würzburg] 1883

- Mennonite Lexicon - Volume V

- Put the red rooster on the roof ( Memento from April 29, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

Remarks

- ^ Reformation in Livonia

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The Peasants' War. The common man's revolution . 3. Edition. Munich 2006, p. 46f. - Blickle conclusion: "From the German Peasants' War itself can be the farmer most out of habit and the German heavy rescue, the event balks at every national subsumption . It is similar with war . […] The peasants… didn't want war, they wanted freedom… ”Blickle (2006), p. 54. Italics in the original.

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The Revolution of 1525. 4th reviewed and bibliographically expanded edition. Munich 2004, p. 195.

- ^ Wolfgang Reinhard: Problems of German History 1495–1806. Imperial reform and Reformation 1495–1555 . In the S. (Ed.): Handbook of German history. Gebhardt, Stuttgart 2001, p. 300f.

- ↑ See e.g. B. the civil uprising in Speyer 1512/13 .

- ↑ Joß Fritz and his time. In: Heimatverein Untergrombach: Contributions to local history. Volume 4.

- ↑ Friedemann Stengel: "Omnia sunt communia." Community of goods with Thomas Mützer , in Archive for Reformation History 102, 2011, pp. 133–174.

- ^ School in Baden-Württemberg: background information , requested on June 22, 2010.

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The Revolution of 1525. Munich 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ Günther Hoppe, Jürgen John : Historical guide - sites and monuments of history in the districts of Erfurt, Gera, Suhl. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig 1978, p. 132.

- ↑ Günther Hoppe, Jürgen John: Historical guide - sites and monuments of history in the districts of Erfurt, Gera, Suhl. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig 1978, p. 252 f.

- ↑ Günther Hoppe, Jürgen John: Historical guide - sites and monuments of history in the districts of Erfurt, Gera, Suhl. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig 1978, p. 138.

- ↑ Günther Hoppe, Jürgen John: Historical guide - sites and monuments of history in the districts of Erfurt, Gera, Suhl. Urania-Verlag, Leipzig 1978, p. 132.

- ↑ Thomas Klein: The consequences of the peasant war of 1525. Theses and antitheses on a neglected topic . In: Hessisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte. Volume 25 (1975), pp. 65-116, here: pp. 73-79. Helmut Gabel and Winfried Schulze also share this view: Consequences and Effects. In: Horst Buszello, Peter Blickle, Rudolf Endres (eds.): The German Peasant War . 3. Edition. Paderborn u. a. 1995, pp. 322-349, here: pp. 328f. on.

- ↑ Horst Buszello: Patterns of interpretation of the peasant war in a historical perspective. In: Horst Buszello, Peter Blickle, Rudolf Endres (eds.): The German Peasant War . 3. Edition. Paderborn u. a. 1995, pp. 11-22, here: p. 13.

- ^ Leopold von Ranke: German history in the age of the Reformation. Vol. 2 [first 1839] ed. by Paul Joachimsen (complete edition, 1st row, 7th work), Munich 1925, p. 165.

- ^ Wilhelm Zimmermann: General history of the great peasant war. 1st part, 2nd edition 1847, p. 5f.

- ^ Friedrich Engels: The German Peasant War. In: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Werke, Vol. 7, 1960, p. 409.

- ↑ Reinhard Jonscher: Baunerkriegerinnern in Thuringia. In: Günter Vogler (Ed.): Peasants' War between Harz and Thuringian Forest. Stuttgart 2008, pp. 467-483, here: p. 476.

- ↑ Karl Marx: On the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Introduction. In: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Werke, Vol. 1, 1976, p. 386.

- ^ Günther Franz: The German Peasant War. 12th, compared to the 11th unchanged edition, Darmstadt 1984, pp. 2f., 80f., 291f.

- ^ Günther Franz: The leaders in the peasant war. In the S. (Ed.): Rural leadership classes in modern times. Büdingen 1974, pp. 1–15, here: p. 1.

- ↑ Günter Vogler: Article “Early bourgeois revolution” . In: Mennonite Lexicon (MennLex V).

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The Peasants' War. The common man's revolution . 3. Edition. Munich 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Locations of the Working Group of the German Peasant War Museums