Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Difference between revisions

| Line 430: | Line 430: | ||

* Winbourne Elementary |

* Winbourne Elementary |

||

===Middle Schools=== |

===Public Middle Schools=== |

||

* Broadmoor Middle |

* Broadmoor Middle |

||

Revision as of 18:32, 18 January 2007

Baton Rouge, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: Red Stick | |

| Motto: Authentic Louisiana at every turn | |

| File:LAMap-doton-Baton Rouge.png | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | East Baton Rouge Parish |

| Founded | 1699 |

| Incorporated | 16 January 1817 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Melvin "Kip" Holden (D) |

| Elevation | 46 ft (14 m) |

| Population (2004) | |

| • City | 224,097 |

| • Metro | 751,965 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| Website | http://www.brgov.com |

Baton Rouge, French: Bâton-Rouge (pronounced /ˈbætn ˈɹuːʒ/ in English, and ![]() [[Media:BatonRouge.ogg|/bɑtɔ̃ ʀuʒ/]] in French) is the capital of the State of Louisiana. As of the 2000 census, its population was 227,818 and as of 2004, the latest U.S. Census Bureau estimate puts the city at 224,097. East Baton Rouge Parish as of June 2005 had 412,000 residents. Baton Rouge is historically the second largest city in Louisiana behind New Orleans but the effects of Hurricane Katrina have, at least temporarily, reduced the population of New Orleans such that Baton Rouge is larger than New Orleans. The Greater Baton Rouge area as of 2000 had a population of 602,894, but has grown to over 750,000 since the 2000 census. Despite Hurricane Katrina Baton Rouge metro area is still smaller than Greater New Orleans. Baton Rouge is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish. Baton Rouge is home to the main campus of Louisiana State University and to Southern University. Baton Rouge is also home to The Shaw Group, a Fortune 1000 Company.[1]

[[Media:BatonRouge.ogg|/bɑtɔ̃ ʀuʒ/]] in French) is the capital of the State of Louisiana. As of the 2000 census, its population was 227,818 and as of 2004, the latest U.S. Census Bureau estimate puts the city at 224,097. East Baton Rouge Parish as of June 2005 had 412,000 residents. Baton Rouge is historically the second largest city in Louisiana behind New Orleans but the effects of Hurricane Katrina have, at least temporarily, reduced the population of New Orleans such that Baton Rouge is larger than New Orleans. The Greater Baton Rouge area as of 2000 had a population of 602,894, but has grown to over 750,000 since the 2000 census. Despite Hurricane Katrina Baton Rouge metro area is still smaller than Greater New Orleans. Baton Rouge is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish. Baton Rouge is home to the main campus of Louisiana State University and to Southern University. Baton Rouge is also home to The Shaw Group, a Fortune 1000 Company.[1]

Baton Rouge also goes by its English translation, "Red Stick." Like other capital cities, its region is called the "Capital Area."

History

French period (1699-1763)

The French name "Baton Rouge" means "Red Stick" in English. In 1699, French explorer Sieur d'Iberville led an exploration party of about 200 up the Mississippi River. On March 17, on a bluff on the east bank of the river (on what is now the campus of Southern University), they saw a cypress pole festooned with bloody animal and fish heads, which they learned was a boundary marker between the hunting territories of the Bayogoula and the Houma tribes (the Bayogoula village was situated near the present-day town of Bayou Goula, LA; the Houma village was believed to be situated near the site of what is now Angola, LA).

The first settlement at the present site of Baton Rouge took place in 1718, when Frenchman Bernard Diron Dartaguette received a grant from the colonial government at New Orleans. Records indicate two whites and 25 blacks (some of whom may have been slaves) resided on the concession in 1718. By 1722, it was reported that there were about 30 whites, 20 blacks and two Indian slaves.

By 1727, however, the Dartaguette settlement had vanished; the reason for its disappearance is not known, though it probably was a combination of crop failure and the concurrent success of the settlement at Pointe Coupee, across the river and a few miles north.

British period (1763-1779)

On Feb. 10, 1763, the the Treaty of Paris was signed, whereby France gave all its territory in North America to Britain and Spain. Spain ended up with New Orleans and all land west of the Mississippi. Britain ended up with all land east of the Mississippi, except for New Orleans. Baton Rouge, now part of the newly-created British colony of West Florida, suddenly had strategic significance as the southwest-most corner of British North America.

The British built Fort New Richmond just south of the eventual site of the Pentagon Barracks (in downtown Baton Rouge), and began plans for the development of a town. Land grants were given, resulting in an influx of the first settlers.

When the older British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America rebelled in 1776, the newer colony of West Florida, lacking a history of local government and distrustful of the potentially hostile Spanish nearby, remained loyal to the British crown.

In 1778, France declared war on Britain, and in 1779, Spain followed suit. That same year, Spanish Governor Don Bernardo de Galvez and his militia of about 1,400 men from New Orleans and conquered Fort New Richmond. The fort was renamed Fort San Carlos. Once the Spanish controlled Baton Rouge, they ordered its inhabitants to declare their allegiance to Spain or leave. Most residents reluctantly stayed. Galvez subsequently captured Mobile in 1780 and Pensacola in 1781, thus ending the British presence on the Gulf Coast.

Spanish period (1779-1810)

A colony of Pennsylvania German farmers settled to the south of town, having moved north to high ground from their original settlement on Bayou Manchac after a series of floods in the 1780s. They were known locally as "Dutch Highlanders" ("Dutch" being an older word for "German") and today’s Highland Road cuts through their original indigo and cotton plantations. The two major roads off of Highland Road, Essen Lane and Siegen Lane were both named after cities in Germany. The Kleinpeter and Staring families (which Staring Lane is named after) have been prominent in Baton Rouge affairs ever since.

In 1800, the Tessier-Lafayette buildings were built on what is now Lafayette Street. The buildings are still standing today.

In 1805, the Spanish administrator, Don Carlos Louis Boucher de Grand Pré, commissioned a layout for what is today know as Spanish Town.

In 1806, Elias Beauregard led a planning commission for what is today known as Beauregard Town.

The Republic of West Florida (1810)

As a result of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, Spanish West Florida found itself almost entirely surrounded by the United States and its possessions. Fort San Carlos became the only non-American post on the Mississippi River.

Several of the inhabitants of West Florida began to have conventions to plan a rebellion. At least one of these conventions was held in a house on a street in Baton Rouge that has since been renamed Convention St. (in honor of the rebel conventions). On September 23, 1810, the rebels overcame the Spanish garrison at Baton Rouge, and unfurled the flag of the new Republic of West Florida, known as the Bonnie Blue Flag. The flag had a single white star on a blue field. The Bonnie Blue Flag also inspired the Lone Star flat of Texas.

Shortly thereafter, the Republic of West Florida petitioned the United States with the request that West Florida be allowed to become an American territory. President James Madison accepted the request, and the American flag went up in Baton Rouge on December 10, 1810.

Since Louisiana statehood (1812-1860)

In 1812, Louisiana was admitted to the Union as a State. Baton Rouge's location continued to be a strategic military outpost. Between 1819 and 1822, the U.S. Army built the Pentagon Barracks, which became a major command post up through the Mexican American War (1846-1848). Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor, supervised construction of the Pentagon Barracks and served as its commander. In the 1830s, what is known today as the "Old Arsenal" was built. The unique structure originally served as a powder magazine for the U.S. Army Post.

In 1825, Baton Rouge was visited by the Marquis de Lafayette as part of his triumphal tour of the United States, and he was the guest of honor at a town ball and banquet. To celebrate the occasion, the town renamed Second Street as Lafayette Street.

In 1846, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. As in many states, representatives from other parts of Louisiana feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city. In 1840, New Orlean's population was around 102,000, fourth largest in the U.S. The 1840 population of Baton Rouge, on the other hand, was only 2,269.

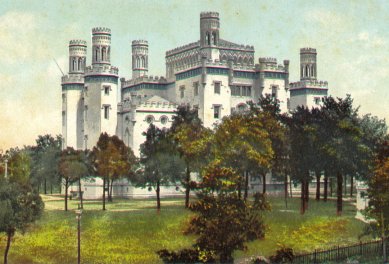

New York architect James Dakin was hired to design the new Capital building in Baton Rouge, and rather than mimic the federal Capitol Building in Washington, as so many other states had done, he conceived a Neo-Gothic medieval castle overlooking the Mississippi, complete with turrets and crenellations. In 1859, the Capitol was featured and favorably described in DeBow's Review, the most prestigious periodical in the antebellum South. Mark Twain, however, as a steamboat pilot in the 1850s, loathed the sight of it, "It is pathetic ... that a whitewashed castle, with turrets and things ... should ever have been built in this otherwise honorable place." (Life on the Mississippi, Chapter 40)

Despite his view of the Capitol, Twain was fond of Baton Rouge, "Baton Rouge was clothed in flowers, like a bride — no, much more so; like a greenhouse. For we were in the absolute South now — no modifications, no compromises, no half-way measures. The magnolia trees in the Capitol grounds were lovely and fragrant, with their dense rich foliage and huge snowball blossoms....We were certainly in the South at last; for here the sugar region begins, and the plantations — vast green levels, with sugar-mill and negro quarters clustered together in the middle distance — were in view." (Life on the Mississippi, Chapter 40)

Civil War period (1860-1865)

Southern secession was triggered by the 1860 election of Republican Abraham Lincoln because slave states feared that he would make good on his promise to stop the expansion of slavery and would thus put it on a course toward extinction. Many Southerners thought that even if Lincoln did not abolish slavery, sooner or later another Northerner would do so, and that it was thus time to quit the Union.

In January 1861, Louisiana elected delegates to a state convention to decide the state's course of action. The convention voted for secession 112 to 17. Baton Rouge raised a number of volunteer companies for Confederate service, including the Pelican Rifles, the Delta Rifles, the Creole Guards, and the Baton Rouge Fencibles (about one-third of the town's male population eventually volunteered).

The Confederates gave up Baton Rouge (which only had a population of 5,429 in 1860) without a fight, deciding to consolidate their forces elsewhere. In May 1862, Union troops entered the city and began the occupation of Baton Rouge. The Confederates only made one attempt to retake Baton Rouge (see main article: Battle of Baton Rouge). The Confederates lost the battle and the town was severely damaged. However, Baton Rouge escaped the level of devastation faced by cities that were major conflict points during the Civil War, and the city still has many structures that predate the Civil War.

In 1886, a statue of a Confederate soldier was dedicated to the memory of those who fought in the Civil War on the corner of Third Street and North Blvd.

Late 19th and early 20th centuries

The mass migration of ex-slaves into urban areas in the South also affected Baton Rouge. It has been estimated that in 1860, blacks made up just under one-third of the town's population. By the 1880 U.S. census, however, Baton Rouge was 60 percent black. Not until the 1920 census would the white population of Baton Rouge again exceed 50 percent. After the end of Reconstruction the white population regained control of the state's and the city's institutions, and segregation and "Jim Crow" laws were enforced, though leavened with a dose of paternalism (Radical Republican control in Louisiana had never been strong outside of New Orleans in any case).

By 1880, Baton Rouge was recovering economically and psychologically, though the population that year still was only 7,197 and its boundaries had remained the same. The carpetbaggers and scalawags of Reconstruction politics were replaced by middle-class white Democrats who loathed the Republicans, eulogized the Confederacy, and preached white supremacy. This "Bourbon" era was short-lived in Baton Rouge, however, replaced by a more management-oriented local style of conservatism in the 1890s and on into the early 20th century. Increased civic-mindedness and the arrival of the Louisville, New Orleans, and Texas Railroad led to the development of more forward-looking leadership, which included the construction of a new waterworks, widespread electrification of homes and businesses, and the passage of several large bond issues for the construction of public buildings, new schools, paving of streets, drainage and sewer improvements, and the establishment of a scientific municipal public health department.

At the same time, the state government was constructing in Baton Rouge a new Institute for the Blind and a School for the Deaf. LSU moved from New Orleans to temporary quarters at the old arsenal and barracks and Southern University relocated from New Orleans to Scotlandville (just north of Baton Rouge at the time but now within the city limits). Finally, legal challenges to the Standard Oil Company in Texas led its board of directors to move its refining operations in 1909 to the banks of the Mississippi just above town; Exxon is still the largest private employer in Baton Rouge.

In the 1930s, the new Louisiana State Capitol building was built under the direction of Huey P. Long, and became the tallest capitol building in the United States. The old state capitol is now a museum.

In the late 1940s, Baton Rouge and East Baton Rouge Parish became a consolidated city/parish with a mayor/president in its government. It was also one of the first cities in the nation to consolidate, and the parish surrounds three incorporated cities: Baker, Zachary, and Central.

2000s

In the 2000s, Baton Rouge has proven to be one of the fastest growing cities in the South, not so much in population but in technology. Baton Rouge is well wired, and ranks #19 as one of the most wired cities (more wired than New Orleans, and most of the 25 largest cities in the United States) There are now many sky-eye traffic cameras at major intersections and countless other advances. Although, Baton Rouge's city population was not growing fast, it has overtaken Mobile, Alabama, Shreveport, and many other currently declining cities. After the 2000 census, Baton Rouge had a slight decline in population, with 224,000 from recent estimates. This is attributed by some to white flight.

Baton Rouge was rated one of the largest mid-sized business cities, and was also a faster growing metropolitan area than metropolitan New Orleans. It was also one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the U.S. (under 1 million), with 600,000 in 2000 and 700,000 since 2000 (although the numbers are shifted since Katrina but still remain well below 800,000). It is projected that its metro population could increase far past 1 million in the 2010s.

Aside from politics, there is also a vibrant mix of cultures found throughout Louisiana, thus forming the basis of the city motto: "Authentic Louisiana at every turn".

Hurricane Katrina

On August 29, 2005, Baton Rouge was heavily impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Although the damage was relatively minor compared to New Orleans (generally light to moderate except for fallen trees), Baton Rouge experienced power outages and service disruptions due to the hurricane. In addition, the city provided refuge for residents from New Orleans. Baton Rouge served as a headquarters for Federal (on site) and State emergency coordination and disaster relief in Louisiana.

The city executed massive rescue efforts for those who evacuated the New Orleans area. Schools and convention centers such as the Baton Rouge River Center opened their doors to evacuees, and churches around the city were sometimes serving two hot meals per day for whoever could come. B'nai Israel Synagogue opened its doors to evacuees with its emergency shelter, the only synagogue in the region to do so. LSU's basketball arena, the Pete Maravich Assembly Center, and the adjacent LSU Field House were converted into emergency hospitals. Victims were flown in by helicopter (landing in the LSU Track Stadium) and brought by the hundreds in buses to be treated. Here patients were triaged and, depending on their status, were either treated immediately or transported further west to Lafayette, Louisiana. As a result of this the LSU football team was forced to play their originally home scheduled game against Arizona State in Arizona, which they won.

As a result, by August 31, TV station WAFB had reported that the city's population had more than doubled from about 228,000 to at least 450,000 since the mandatory evacuation had been issued. That day, Mayor-President Kip Holden was expected to host a conference to discuss how to effectively enroll evacuated children into the East Baton Rouge Parish public school system. Traffic in the city has been more congested than usual since the evacuation of New Orleans. The most heavily traveled roads were I-10, I-12, Florida Boulevard, Bluebonnet Boulevard, Perkins Road, College Drive, Greenwell Springs Road, and Airline Highway. All have experienced traffic levels beyond any conceivable capacity.

Multiple funds erupted in the city for donations, including the Baton Rouge Area Foundation's Katrina funds for evacuees living in Baton Rouge.

Immediately after Katrina, the Baton Rouge real-estate market experienced dramatic business; any property placed on the market would sell within hours due to extreme demand.[1] The market has since returned to its pre-Katrina status, though home prices continue to rise to an average price $178,200.

When Baton Rouge had a large number of evacuees it temporarily brought with it a boom never before seen in the Capital City and made 2006 one of the best economic years and one of the best years overall in Baton Rouge history. East Baton Rouge Parish enjoyed being the state's most populous parish and brought in tax revenue that even the best performing businesses could have only dreamed of in Baton Rouge. However, with only 15,000 to 30,000 of the original estimated 200,000 to 250,000 Katrina evacuees still in the area, the long term impact of Hurricane Katrina on Baton Rouge is expected to be minimal as residents return to their home regions. One of the effects which was proven temporary was East Baton Rouge Parish's status as Louisiana's most populous parish; as of October 2006 Jefferson Parish is the state's most populous parish as its population has returned to near pre-Katrina levels of 455,000 (2000 U.S. Census) residents. A June 2006 estimate put East Baton Rouge Parish at about 20,000 more residents than its 412,000 pre-Katrina total. It should be noted that Jefferson Parish mayor Aaron Broussard believes that not only will Jefferson Parish reach pre-Katrina numbers, but that it will exceed those numbers as residents from Orleans Parish return to Jefferson Parish to be closer to New Orleans as they repair their Orleans Parish homes.

Crime

Crime in Baton Rouge is higher than the national average. In 2005, the city's murder rate was higher than many of the largest U.S cities, ranking 28th out of 100 U.S cities, ( http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0934323.html )

and totaling over 68 murders in 2006. ( www.crimestoppersbr.com )

http://brgov.com/DEPT/BRPD/csr/

Geography and Climate

Baton Rouge is located at 30°27′29″N 91°8′25″W / 30.45806°N 91.14028°WInvalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function (30.458090, -91.140229)Template:GR.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 204.8 km² (79.1 mi²). 199.0 km² (76.8 mi²) of it is land and 5.7 km² (2.2 mi²) of it (2.81%) is water.

Baton Rouge along with Tallahasee, FL and Austin, TX is one of the southernmost capital cities in the lower 48 U.S

Climate

Baton Rouge is humid-subtropical, with mild, short, wet, and somewhat warm winters and long, hot, humid, even wet summers. Even though snow is almost unheard of, the last snowfall took place in 2004; the snow took only hours to melt.

Disasters

Baton Rouge rarely suffers from natural disasters. Earthquakes are very rare (unlike further north up the Mississippi River). The Mississippi River poses little threat to the highly populated sections of the city because it is built naturally on bluffs that overlook the river. However, the outlying areas near the Amite and Comite Rivers are very easily flooded if it were soaked by a large amount of rain. Baton Rouge rarely sees tornadoes, and storm surges are impossible because of its distance inland.

Demographics

| City of Baton Rouge Population by year [2] | |

| 1950 | 125,629 |

| 1960 | 152,419 |

| 1970 | 165,963 |

| 1980 | 219,419 |

| 1990 | 219,531 |

| 2000 | 227,818 |

| 2004 | 224,097 (estimate) |

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 227,818 people, 88,973 households, and 52,672 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,144.7/km² (2,964.7/mi²). There were 97,388 housing units at an average density of 489.4/km² (1,267.3/mi²). The racial makeup of the city was 50.02% African American, 45.70% White, 0.18% Native American, 2.62% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.49% from other races, and 0.96% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.72% of the population.

There were 88,973 households out of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.8% were married couples living together, 19.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.8% were non-families. 31.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.12.

In the city the population was spread out with 24.4% under the age of 18, 17.5% from 18 to 24, 27.2% from 25 to 44, 19.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females there were 90.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,368, and the median income for a family was $40,266. Males had a median income of $34,893 versus $23,115 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,512. About 18.0% of families and 24.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.4% of those under age 18 and 13.6% of those age 65 or over.

During the immediate months following Hurricane Katrina Baton Rouge received an influx of about 250,000 evacuees from New Orleans and surrounding devastated areas but as time passed on about 220,000 to 235,000 displaced citizens left the Baton Rouge area and returned to New Orleans or other areas. The reason for such a mass exodus out of Baton Rouge was that the housing market was not stable enough to handle the influx and the infrastructure could not handle the possible "new residents" as police departments, hospitals, road ways, etc were stressed thinly, many evacuees were transported to Houston, Texas and Dallas, Texas and different cities throughout the south and even in some instances just general un-interest of living in the Baton Rouge area. A February 2006 estimate put 77,000 displaced residents in Baton Rouge. As of October 2006 between 15,000 and 30,000 displaced citizens remain in Baton Rouge and many consider themselves to be temporary residents. Ed Kramer of Palm Hills Development LLC and D.R. Horton a Fort Worth, Texas, homebuilder who was thinking about building some homes in Baton Rouge, Ascension and Livingston parish questioned just how stable the Baton Rouge market is and what the demand would be the for new homes being built in the three parish metro area by saying "The conventional wisdom was that Baton Rouge was going to gain 100,000 in population (post-Katrina), then 60,000, then 30,000 so the number of displaced citizens have decreased dramatically. But I see the New Orleans recovery, (while) slow to pick up momentum, coming back faster and stronger than people are giving credit for," and more New Orleanians leaving the Baton Rouge area for New Orleans or elsewhere, Kramer said. Are there that many people looking for that type of product? I don't know," he said. The mass exodus of displaced citizens from the Baton Rouge area is the opposite of what Mayor-President Kip Holden and the Baton Rouge area Chamber believed, they believed that the majority of the displaced residents would make Baton Rouge their permanent home but with the mass exodus it really brings into question the truth about the "growth" in the Baton Rouge area. Some argue whether Baton Rouge should even be called a "growing" city seeing as hundreds of thousands of displaced citizens have left the Baton Rouge area by saying the statement is contradictory to the true declining state of Baton Rouge's population nearly a year and half removed from Katrina and say that since that first mass migration after Hurricane Katrina to the Baton Rouge area Baton Rouge's population has declined.

Tallest buildings

Baton Rouge currently has several towers in the works. One project includes a 17 story office, another a 30+ story condominium tower to be the first towers built downtown in two decades.

| Name | Stories | Height |

|---|---|---|

| RiverPlace Condominiums (under construction) | 36 | |

| Louisiana State Capitol | 34 | 460 ft (140 m) |

| Riverfront Office Tower (proposed) | 25 | |

| One American Place | 24 | 310 ft (94 m) |

| JPMorgan Chase Tower | 21 | 277 ft (84 m) |

| Riverside Tower North | 20 | 229 ft (70 m) |

| Marriott Hotel Baton Rouge | 22 | 224 ft (68 m) |

| Laurel Street Tower (on-hold) | 19 | |

| Two City Plaza (approved) | 17 | |

| Catholic-Presbyterian Apartments | 14 | |

| Dean Tower | 14 | |

| Galvez Office Building | 12 | |

| Kirby Smith Hall (LSU) (Plans for demolition within the next five years are in place) | 13 | |

| Memorial Tower (LSU) | 175 ft (52m) | |

| Saint Joseph's Cathedral | 165 ft (50m) | |

| Louisiana State Office Building | 12 | 160 ft (49 m) |

| Jacobs Plaza | 13 | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Bluebonnet Towers (3 residential towers) | 12 | |

| LaSalle Office Building | 12 | |

| Shaw Plaza | 12 | |

| Wooddale State Office Building | 12 | |

| Hilton Capital Center | 11 | 132 ft (40 m) |

| 19th Judicial District Court Building | 10-11 | |

| Sheraton Baton Rouge Convention Center Hotel | 10 | 125 ft (38 m) |

http://www.emporis.com/en/wm/ci/?id=102363/

Neighborhoods

- 38th- Area that is between Winborne and Prescott Mohican crossover. It's with Prescott and Ghost town. One of the popular streets in 38th is Ozark st.

- Downtown - Baton Rouge's central business district.

- Spanish Town - Located between the Mississippi River and I-110, it is one of the city's trendiest neighborhoods and home to the State Capitol Building and the city's largest Mardi Gras Parade.

- Beauregard Town - A historic district between the downtown area and Old South Baton Rouge. Many of the homes have been renovated and are used as law offices.

- Garden District - The Garden District is located in Baton Rouge's Mid-City area where Park Boulevard intersects Government Street. The Garden District is an established historic area with many upscale homes.

- Old South Baton Rouge - An old section of the city directly south of downtown and Beauregard Town, it stretches south from I-10 and along the river to Brightside Lane. After years of neglect and a crumbling infrastructure, the city is targeting the neighborhood in the city's largest ever revitalization project.

- LSU/Lakeshore - Home to LSU's main campus, the University Lakes and the City Park lake. It includes neighborhoods like University Hills, University Gardens, College Town, and Arlington. Homes directly on the lakeshore are some of the most expensive within the city limits, and the lakeshore itself is a popular place for jogging, walking and bicycling.

- Mid-City - Bound by I-110 on the west, College and N. Foster on the east, Choctaw to the north and I-10 to the south. It includes several neighborhoods like Ogden Park, Bernard Terrace, and Capital Heights. Always a socially and economically diverse area, Mid City is quickly regaining popularity due to urban renewal and gentrification.

- Brookstown - Is bordered by Airline Highway to the east, Hollywood St to the north, McClelland St to the west and Evangeline St to the south.

- Melrose Place - Melrose Place is home to BRCC and is between N. Ardenwood and N. Foster Rd.

- Melrose Place East/Mall City - Is bordered by Florida Blvd (US 190) to the south, Greenwell Springs Rd to the north, Airline Highway to the east, and N. Ardenwood Dr to the west. However the border is traditionally between Mall at Cortana and the old Bon Marche Mall.

- Inniswold - Area around Bluebonnet Rd between Jefferson Hwy and I-10.

- Goodwood - an older subdivision located between Government Street, Jefferson Highway, Airline Highway, and Old Hammond Highway.

- Southdowns - an older subdivision located between Perkins Road and Bayou Duplantier, also between the University Lake and Pollard Estates. Hosts one of Baton Rouge's Mardi Gras parades, on the Friday night before Mardi Gras.

- Gardere - an area using Gardere Lane (LA Highway 327 Spur) as its main artery. Found between Nicholson Drive and Highland Road, located near St. Jude the Apostle Church. Dominated by low-rent housing prior to Hurricane Katrina.

- Westminster - Just north of Inniswold, around the Baton Rouge Country Club.

- Oak Hills Place -Bordered by Bluebonnet Blvd to the west, Perkins Road to the north, and Highland Road to the south. South of the Mall of Louisiana.

- Broadmoor - Founded in 1950, Broadmoor is a very nice, well established neighborhood with many fine examples of Mid-Century Modern Architecture. Florida Blvd. is to the north, Airline Hwy. is to the west, Old Hammond Hwy. to the south, and Sharp Rd. is to the west. Broadmoor is host to a dedicated civic association that concentrates on neighborhood preservation as well as beautification. Because of the neighborhoods' geographical location within the center of the City of Baton Rouge, the Broadmoor Resident's Association adopted the slogan: "Broadmoor, The Heart Of Baton Rouge" ©2005 (Used by permission).

- Shenandoah - A very large subdivision, built in the 1970s and 1980s, located between South Harrell's Ferry and Tiger Bend Roads with its westernmost boundary Jones Creek Road. Schools in this subdivision include: Shenandoah Elementary and St. Michael the Archangel.

- Sherwood Forest - A large, established neighborhood with large, older homes. Located just east of "Broadmoor." Sherwood Forest Blvd. is to the south, Flannery Rd. is to the west, Florida Blvd. is to the north, and Sharp Rd. is to the east.

- Village St. George - located off Siegen Lane near the Mall of Louisiana. Named after nearby St. George Catholic Church.

- Brownfields - located near Baker off Comite Drive and bounded between Foster Road and Plank Road.

- Zion City - Between Hooper Road and Airline Highway.

- Monticello - located off Greenwell Springs Road between the Baton Rouge City Limits and Central City, site of Greenbriar Elementary School.

- Merrydale - located in northern Baton Rouge between Mickens Road and Airline Highway, site of Glen Oaks High School.

- Old Jefferson -located off Jefferson Highway near Antioch and Tiger Bend Roads. Site of Most Blessed Sacrament School and Woodlawn High School.

- University Club - A newer neighborhood built inside the University Club Golf course located off of Nicholson Drive on the south edge of Baton Rouge.

- Dixie - Located west of 38th (GhostTown) between Plank Road and Scenic Hwy, It is known for having streets named after Indians the most common streets are Canonicus Street and Tecumseh Street.

- Third World - Refers to Scotlandville (Scotland and Scotland Square), Bankstown (Banks), and Field Town (The Field). All residence in the area attends Scotlandville Magnet High School

Points of Interest

- Alex Box Stadium - Baseball stadium for LSU.

- Baton Rouge River Center - Entertainment complex.

- Baton Rouge Zoo - BREC’s Baton Rouge Zoo is home to over 1,800 animals from around the world. The Baton Rouge Zoo was the first zoo in Louisiana to achieve the distinguished honor of being accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

- Blue Bayou Waterpark - Blue Bayou has over 20 water rides. Favorites are the "Mad Moccasin," "Conja" and "Racers."

- BREC, LSU, BRAS Highland Road Observatory - An astronomical observatory for education and recreation that provides regular events open to the public.

- The Darkroom - Baton Rouge's only all-ages live music venue. Featuring local and touring bands.

- Dixie Landin' Amusement Park - Dixie Landin' contains 26 rides, 10 games and more. Contains such rides as the "Ragin' Cajun," "Flyin' Tigers," "Gilbeau's Galaxi" and "The Glimmer."

- Capitol Lakes - located north of the State Capitol.

- F.G. Clark Center - basketball arena for Southern University.

- The Herbarium of LSU

- Huey Long Field House - one-time student union for LSU. When built, it featured the largest indoor swimming pool in the country at that time.

- Independence Park Botanic Gardens - Includes a rose garden, crape myrtle garden, sensory garden, children's forest, and Louisiana iris garden.

- Memorial Stadium - 21,395-seat football stadium. Was built in 1956 in memory of the men and women who fought and served Baton Rouge during the two World Wars and the Korean War.

- Laurens Henry Cohn, Sr Memorial Plant Arboretum - contains more than 120 species of trees and shrubs on 16 acres.

- Louisiana Arts and Science Museum - Contains art and science galleries, an Ancient Egypt Gallery, and simulated space travel in the Challenger Learning Center. LASM is also home to the Irene W. Pennington Planetarium and ExxonMobil Space Theater, which offers planetarium shows and large-format films.

- Louisiana Museum of Natural History - Contains two main exhibit areas, one in the Textile and Costume Museum, the other in the Museum of Natural Science.

- Louisiana State Capitol - tallest state capitol building in the United States.

- LSU - One of only thirteen American universities designated as a land-grant, sea-grant and space-grant research center.

- LSU Museum of Art - located within the Shaw Center for the Arts. LSU MOA's permanent collection consists of about 4,000 objects with an emphasis placed on American, British, and, in particular, Louisiana art.

- LSU Museum of Natural Science - Was founded in 1936. Is one of the nation's largest natural history museums, with holdings of over 2.5 million specimens. As the only comprehensive research museum in the south-central United States, the LSU Museum of Natural Science fulfills a variety of scientific and educational roles.

- LSU Rural Life Museum - Commemorates the contributions made by Baton Rouge's various cultural groups through interpretive programs and events throughout the year.

- LSU University Lakes

- Magnolia Mound Plantation - Built c. 1791. Is a rare survivor of the vernacular architecture influenced by early settlers from France and the West Indies.

- Mall at Cortana - Contains Dillards, Sears, JCPenny, Macy's, and over 110 specialty stores and services.

- Mall of Louisiana - Contains Dillards, Sears, JCPenny, and Macy's. Has over 160 stores and services. It will soon incorporate 11 upscale stores, as well as four additional restaurants.[2]

- Mount Hope Plantation

- The Old Arsenal Powder Magazine - Is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Was built around 1838.

- Old State Capitol - Louisiana's Old State Capitol Center for Political and Governmental History houses several interactive state-of-the-art exhibits including "Huey Long Live! The Kingfish Speaks", "We The People," "The Governor Huey P. Long Assassination Exhibit" and more.

- Perkins Rowe (coming soon) - An urban village with residences, theatres, restaurants, and specialty shops.

- Pete Maravich Assembly Center - The "PMAC" is a 13,472-seat multi-purpose arena. The arena opened in 1972, and is home to the LSU Tigers and Lady Tigers basketball teams, volleyball team and gymnastics team. It was originally known as the "LSU Assembly Center," but was renamed in memory of Pete Maravich, a Tiger basketball legend, shortly after his death in 1988.

- Poplar Grove Plantation - Began life not as a home but as the Bankers' Pavilion at the World's Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition of 1884 in New Orleans. The exposition was held at what is today Audubon Park in uptown New Orleans. Was moved upriver on a barge in 1886 and became the home of sugar planter Horace Wilkinson and his wife, Julia.

- Shaw Center for the Arts - Performing-art venue and fine arts museum located at 100 Lafayette Street downtown.

- Southern University - one of the most well known historically black colleges and universities.

- Tiger Stadium LSU football stadium.

- USS Kidd - a Fletcher-class destroyer, was the 1st ship of the United States Navy to be named for Rear Adm. Isaac C. Kidd, Commander of Battleship Division 1, who died on the bridge of his flagship USS Arizona during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Media

Greater Baton Rouge is well served by television and radio. The market is the 93rd largest Designated Market Area (DMA) in the United States, serving 322,540 homes or 0.290% of the U.S. population.

Television

Major television network affiliates serving the area include:

- 2 WBRZ (ABC)

- 9 WAFB (CBS)

- 21 WBRL (The CW)

- 27 WLPB (PBS)

- 33 WVLA (NBC)

- 39 WBXH (My Network TV)

- 44 WGMB (Fox)

KPBN 11, KZUP 19, WBTR 41, also operates as independent stations in the area, and WLFT 30 providing mainly religious programming. Other cable-only stations include: Metro 21, Cox 4, and Catholic Life Channel 15.

Periodicals

The major daily newspaper is The Advocate, publishing since 1925. Prior to October of 1991, Baton Rouge also had an evening newspaper, The State-Times. Other publications include: 225, LSU Daily Reveille, Tiger Weekly, and Greater Baton Rouge Business Report.

Radio

- College: KLSU-FM (91.1)

- Country: WYPY-FM (100.7), WYNK-FM (101.5), WTGE-FM (107.3)

- Contemporary: WQCK-FM (92.7)

- Gospel/Christian: WJFM-FM (88.5), WPAE-FM (89.7), KPAE-FM (91.5), WXOK-AM (1460), WPFC-AM (1550)

- Hits: KRDJ-FM (93.7), WFMF-FM (102.5), WCDV-FM (103.3)

- Jazz: WBRH-FM (90.3)

- Oldies: KBRH-AM (1260)

- Public Radio: WRKF-FM (89.3)

- Rock: KRVE-FM (96.1), WDGL-FM (98.1), WNXX-FM (104.5), KNXX-FM (104.9)

- Silent: WNDC-AM (910)

- Sports: WSKR-AM (1210)

- Talk: WJBO-AM (1150), WIBR-AM (1300), WPYR(AM) (1380)

- Urban/Urban Contemporary: WEMX-FM (94.1), KQXL-FM (106.5)

- Variety: KKAY-AM (1590)

Education

East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools, the city's school district, is one of the area's largest school districts. EBRPS contains approximately 90 individual schools: 56 elementary schools, 16 middle schools, and 18 high schools.

Elementary Schools

- Audubon Elementary

- Banks Elementary

- Baton Rouge Center for Visual and Performing Arts (BRCVPA)

- Belfair Elementary

- Bellingrath Hills Elementary

- Bernard Terrace Elementary

- Broadmoor Elementary

- Brookstown Elementary

- Brownsfield Elementary

- Buchanan Elementary

- Cedarcrest-Southmoor Elementary

- Claibourne Elementary

- Crestworth Elementary

- Dalton Elementary

- Delmont Elementary

- Dufrocq Elementary

- Eden Park Elementary

- Forest Heights Acadamy of Excellence

- Glen Oaks Park Elementary

- Greenville Elementary

- Highland Elementary

- Howell Park Elementary

- Jefferson Terrace Elementary

- La Belle Aire Elementary

- Lanier Elementary

- LaSalle Elementary

- Magnolia Woods Elementary

- Melrose Elementary

- Merrydale Elementary

- Wilma C. Montgomery Center

- North Highlands Elementary

- Northeast Elementary (PK-6th) Pride, LA

- Park Elementary

- Park Forest Elementary

- Parkview Elementary

- Polk Elementary

- Progress Elementary

- Riveroaks Elementary

- Rosenwald Pre-K Center

- Ryan Elementary

- Scotlandville Elementary (formally Harding Elementary)

- Sharon Hills Elementary

- Shenandoah Elementary

- South Boulevard Extended Day

- Southdowns Elementary

- Tanglewood Elementary

- Twin Oaks Elementary

- University Terrace Elementary

- Villa del Rey Elementary

- Wedgewood Elementary

- Westdale Heights Academic Magnet

- White Hills Elementary Baker, LA

- Wildwood Elementary

- Winbourne Elementary

Public Middle Schools

- Broadmoor Middle

- Capitol Middle

- Central Middle

- Crestworth Middle Tech

- Glasgow Middle

- Glen Oaks Middle

- Kenilworth Middle

- McKinley Middle Magnet

- Mohican Education Center

- Park Forest Middle

- Prescott Middle

- Sherwood Middle Magnet

- Southeast Middle

- Staring Education Center

- Westdale Gifted

- Woodlawn Middle

Public High Schools

- Arlington Prep. Academy

- Baton Rouge Magnet High School

- Baton Rouge Prep. Academy

- Belaire High School

- Broadmoor High School

- Capitol Pre-College Academy for Boys (formally Capitol High School)

- Capitol Pre-College Academy for Girls (formally Capitol High)

- Central High School

- Glen Oaks High School

- Istrouma High School

- McKinley Senior High School

- Northeast High School (7th-12th) Pride, LA

- Northdale Academy

- Robert E. Lee High School (referred as "Lee High")

- Scotlandville Magnet High School (referred as Scotland High)

- Tara High School

- Valley Park Alternative

- Woodlawn High School (Louisiana)

Private Schools

- Parkview Baptist School

- University Laboratory School (LSU)

- Southern University Laboratory School

- St. Joseph's Academy

- The Dunham School

- Redemptorist High School

- Episcopal High School

- Catholic High School

- St. Michael the Archangel High School

- Runnels School

- Most Blessed Sacrament School

- St. Thomas More School

- St. Jude the Apostle School

- Sacred Heart of Jesus School

- St. Louis King of France School

- Our Lady of Mercy School

- St. Jean Vianney School

- St. George School

- St. Aloysius School

- Gables Academy

- St. Luke's Episcopal Day School

Colleges and Universities

- Louisiana State University

- Southern University

- Baton Rouge Community College

- Our Lady of the Lake College

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center School of Nursing

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center School of Radiologic Technology

- Louisiana Technical College (Baton Rouge campus)

- University of Phoenix (Baton Rouge campus)

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

Baton Rouge is served by a number of hospitals:

- Benton Rehabilitation Hospital - 7660 Convention Street

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center Mid-City - 3600 Florida Boulevard

- Baton Rouge General Medical Center Bluebonnet - 8585 Picardy Avenue

- Earl K. Long Medical Center (LSUMC) - 5825 Airline Highway

- HealthSouth Rehabilitation Hospital - 8595 United Plaza Boulevard

- HealthSouth Surgi-Center - 5222 Brittany Drive

- Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center - 5000 Hennessy Boulevard

- Sage Rehabilitation Hospital - 8225 Summa Avenue

- St. Jude Children's Research Hospital - 7777 Hennessy Boulevard

- Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Treatment Center - 4950 Essen Lane

- Ochsner Medical Center - 1700 Medical Center Drive

- Vista Surgical Hospital - 9032 Perkins Road

- Womans Hospital - 9050 Airline Highway

Transportation

Baton Rouge is connected by the following major routes: I-10 (Capital City Expressway via the Horace Wilkinson Bridge), I-12 (Republic of West Florida Parkway, also known as the Florida Expressway), I-110 (Martin Luther King Jr. Freeway), Airline Highway (US 61), Florida Boulevard (US 190) (via the Huey P. Long Bridge), Greenwell Springs Road (LA 37), Plank Road/22nd Street (LA 67), Nicholson Drive (LA 30), Jefferson Highway (LA 73), Louisiana Highway 1 (LA 1) and Scotland/Baker/Zachary Highway (LA 19). The business routes of US 61/190 run west along Florida Blvd. from Airline Hwy. to River Road downtown. The routes also run along River Rd., Chippewa Street and Scenic Highway from Chippewa to Airline. US 190 joins US 61 on Airline Hwy from Florida Blvd. to Scenic Hwy, where the two highways split. US 190 continues westward on Airline to the Huey P. Long Bridge while US 61 heads north on Scenic Highway. The city is served by the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport.

Public transit is provided by the Capitol Area Transit System (CATS). Due to the increase in population following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, RTA buses from New Orleans are being brought into Baton Rouge to supplement CATS. The funding for the extra New Orleans RTA buses will run out on November 30, 2006, and those buses will return to New Orleans.

There are plans to create a BRT system as well as extending I-110 to a northern loop/bypass for the Baton Rouge area, however the plan for the loop/bypass failed as of December 6, 2006. There are also plans to improve, extend, and add more roads to the area but that measure also failed because of $13.3 billion backlog of long awaited needs for Louisiana roads.

Utilities

Electricity services for Baton Rouge are provided by Entergy, and DEMCO. Waste pickup is provided by Allied Waste Services, formally BFI.

Notable inhabitants, past and present

Sports figures

- Seimone Augustus, WNBA guard for the Minnesota Lynx (b. 1984)

- Billy Cannon, former All-American and 1959 Heisman Trophy winner (b. 1937)

- David Dellucci, MLB outfielder for the Philadelphia Phillies (b. 1973)

- Warrick Dunn, NFL running back for the Atlanta Falcons (b. 1975)

- Alan Faneca, NFL guard for the Pittsburgh Steelers (b. 1976)

- Randall Gay, NFL cornerback for the New England Patriots (b. 1982)

- Darryl Hamilton, MLB outfielder for various clubs (b. 1964)

- Fred Haynes (1946-2006), LSU football great, 1964-1968

- Stefan LeFors, NFL quarterback for the Carolina Panthers (b. 1981)

- Jonathan Papelbon, MLB pitcher for the Boston Red Sox (b. 1980)

- Carly Patterson, Olympic gold medalist (b. 1988)

- Bob Pettit, Basketball Hall of Famer (b. 1932)

- Andy Pettitte, MLB pitcher for the Houston Astros (b. 1972)

- Bobby Phills, former professional basketball player (d. 2000)

- Ben Sheets, MLB pitcher for the Milwaukee Brewers (b. 1978)

- Jim Taylor, Football Hall of Famer (b. 1935)

- Tyrus Thomas, NBA forward for the Chicago Bulls (b. 1986)

- Reggie Tongue, NFL safety for the Kansas City Chiefs, Seattle Seahawks, New York Jets, and Oakland Raiders

Entertainers

- Donna Douglas, actress from The Beverly Hillbillies (b. 1933)

- Randy Jackson, musician, record producer, and American Idol judge (b. 1956)

- Chris Thomas King, American blues musician and actor (b. 1962)

- Lil Boosie, rap artist (b. 1983)

- Reiley McClendon, actor (b. 1990)

- Cleo Moore, actress (d. 1973)

- Master P, rap artist and founder/CEO of No Limit Records (b. 1967)

- Elemore Morgan, Jr, landscape painter and photographer (b. 1931)

- James Paul, Conductor Emeritus of the Baton Rouge Symphony (b. 1940)

- Tabby Thomas, blues musician and club owner (b. 1929)

- Pruitt Taylor Vince, character actor (b. 1960)

- Webbie, rap artist (b. 1985)

- Shane West, actor (b. 1978)

- Lynn Winfield, actress

- Lil Handy, rap artist (d.2005)

- C-Loc, rap artist

- Max Minelli, rap artist (b.1980)

Politicians

- Jack Breaux, first Republican mayor of a Louisiana community, mayor of Zachary in East Baton Rouge Parish from 1966 until his death in 1980

- Overton Brooks, former Louisiana Democratic U.S. representative from 1937-1961 (d. 1961), D

- James H. "Jim" Brown, former state senator, secretary of state, and state insurance commissioner (b. 1940), D

- Jeff Fortenberry, Republican U.S. Representative from Nebraska (b. 1960)

- Clark Gaudin, attorney and first Republican state representative from East Baton Rouge Parish since Reconstruction (b. 1931), R

- Kip Holden, Mayor-President of East Baton Rouge Parish (b. 1952), D

- Louis E. "Woody" Jenkins, former Louisiana state representative and three-time U.S. Senate candidate (b. 1947), R

- Elmer Litchfield, sheriff of East Baton Rouge Parish from 1983 to 2006 (b. 1927), R

- Dan Richey, former state legislator and political consultant (b. 1948), R

- Buddy Roemer, former governor and Baton Rouge businessman (b. 1943), R

- Tony Perkins, President of the Family Research Council (b. 1963), R

- David Treen, former Louisiana governor (b. 1928), R

Military commanders

- Robert H. Barrow, 27th Commandant for the USMC from 1979-1983 (b. 1922)

- John A. Lejeune, Marine Corps general (d. 1942)

Intellectuals

- Margaret Dixon, first woman managing editor of the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (1949-1970), crusader for prison reform and assistance to the mentally ill

- Stephan Kinsella, American intellectual property lawyer and libertarian legal theorist (b. 1965)

- Lars Kestner, author

- Joe Giaime, physics professor at LSU, head of the LIGO Livingston Observatory

Sister cities

Aix-en-Provence, France

Aix-en-Provence, France Cordoba, Mexico

Cordoba, Mexico Taichung, Taiwan

Taichung, Taiwan Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Port-au-Prince, Haiti

After a visit to the Republic of China (Taiwan), Mayor-President Kip Holden unveiled plans to pursue a sister city agreement with a second Taiwanese city, Taipei.

See also

References

- ^ "Rankings-The Shaw Group". 2005. Retrieved 2006-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher: theshawgrp.com" ignored (help) - ^ "General Growth Properties". 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Text "publisher: generalgrowth.com" ignored (help)

External links

- For a list (updated almost daily) of "Disaster Assistance Information & Contact Numbers," go to the East Baton Rouge Parish Library website and click on "Disaster Assistance Information".

- Official Baton Rouge Government Web Site

- BatonRouge.com City Guide

- Baton-Rouge-Guide.com Restaurants, Things to Do, LSU football, movies, news, blog, car sales and repair

- Spanish Town Mardi Gras Official Web Site

- Baton Rouge Area Foundation Establishes Hurricane Katrina Disaster Funds

- National Weather Service New Orleans/Baton Rouge office